Abstract

Exome sequencing is phenotypic-driven analysis of coding genetic variants and is frequently used for the genetic diagnosis of nonspecific or clinically indistinguishable presentations. Clinical laboratories who provide exome sequencing filter variants based on phenotypic information provided by the ordering clinicians. This can lead to difficulties in reporting results that a laboratory does not believe are relevant to the testing indication. This is further complicated by common variants of uncertain significance and genes associated with wide spectrums of presentations. Here, we report a case of a 12-year-old boy who initially presented with gait disturbances. His whole exome sequencing, performed at a national reference laboratory, was initially reported as negative. Careful review of variants characterized by the lab as variants of uncertain significance “not associated with the patient’s phenotype” along with the clinical context of the patient suggested a possible diagnosis of GCH1 deficiency due to compound heterozygous variants of uncertain significance in this gene. Subsequent biochemical evaluations demonstrated a low urinary neopterin to biopterin ratio and normal baseline plasma phenylalanine. Elevated phenylalanine to tyrosine ratio after phenylalanine loading biochemically confirmed the diagnosis without invasive lumbar puncture. The patient subsequently responded with marked improvement in symptoms after initiation of levodopa therapy. This case highlights the importance of careful review of uncertain variants, in the context of phenotypic information, identified on exome sequencing.

Article Summary:

Exome sequencing on a child with atypical gait was reported as negative. Follow up biochemical evaluation and reanalysis led to diagnosis of treatable DOPA-responsive dystonia.

Background

Gait disturbances are a common pediatric complaint with wide ranging possible etiologies [1]. Depending on case history, persistence of symptoms, and response to first line management, specialty evaluation by orthopedic specialists or neurologists may be considered. One possible etiology for gait disturbance is dystonia, which is a movement disorder where “involuntary sustained or intermittent muscle contractions cause twisting and repetitive movements, abnormal postures, or both” [2]. In some cases, dystonia first presents as gait disturbances in children. Dystonia may coexist with other disorders of muscle tone, such as spasticity, making clinical differentiation of phenotypes challenging. When genetic etiologies are suspected, one can consider broad genetic evaluation with exome sequencing [3]. A caveat with exome sequencing is that clinical laboratories have significant discretion in interpretation and reporting of variants. As a clinical test, exome sequencing is phenotype-driven where clinician-provided description of patient features and machine-assisted analysis help laboratory directors prioritize genetic variants. American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines assist laboratory directors in determining classification of genetic variants as pathogenic, benign, or variant of uncertain significance (VUS) [4]. These guidelines are useful for standardizing classification across laboratories, but often relegate variants to an indeterminate classification of VUS. These variants challenge physicians to decide whether or not an uncertain report represents a true diagnosis. Clinical practice in these situations vary widely and are generally based on clinician judgement. While ACMG guidelines allow laboratories to justify their variant classifications, they do not provide guidance on what variants are reported. As clinical testing often is requisitioned with minimal clinical information provided to a laboratory, or information abstracted from a single clinical note, clinical laboratory directors use their discretion to assess whether variants are potentially relevant to a patient’s presentation. These challenges are compounded when different genetic variants within a gene lead to distinct clinical phenotypes or distinct modes of inheritance.

One gene associated with a complex phenotypic and inheritance spectrum is GTP-Cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1), which encodes an enzyme required for the first step of tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis [5]. Tetrahydrobiopterin is a required co-factor for hydroxylase enzyme function. Severe deficiency due to recessive loss of function leads to an atypical phenylketonuria due to decreased activity of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Dominant negative variants are well described and do not lead to baseline hyperphenylalaninemia. Instead these lead to dystonia due to central tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency decreasing tyrosine hydroxylase activity [6] and thereby decreased dopamine synthesis. This is highly responsive to low doses of levodopa [7]. While originally described as dominant, several kindreds have been described with compound heterozygous variants in GCH1 with DOPA-responsive dystonia without baseline hyperphenylalaninemia [8, 9]. As such, variants in this gene are particularly challenging for molecular genetic interpretation.

In this report, we describe a boy who presented to the genetics clinic with gait disturbances. Exome sequencing was performed after orthopedic and neurologic imaging studies did not suggest an etiology. The exome sequencing test from a national reference laboratory was reported as “negative: no variants related to the clinical indication” but did include a list of variants “not related to the clinical presentation”. These variants included compound heterozygous variants of uncertain significance in GCH1, a gene which can be associated with either an autosomal dominant or recessive DOPA-responsive dystonia. Subsequent biochemical testing confirmed the diagnosis of GTP-cyclohydrolase deficiency without hyperphenalaninemia and patient demonstrated gait improvement after initiating treatment with levodopa.

Case Presentation

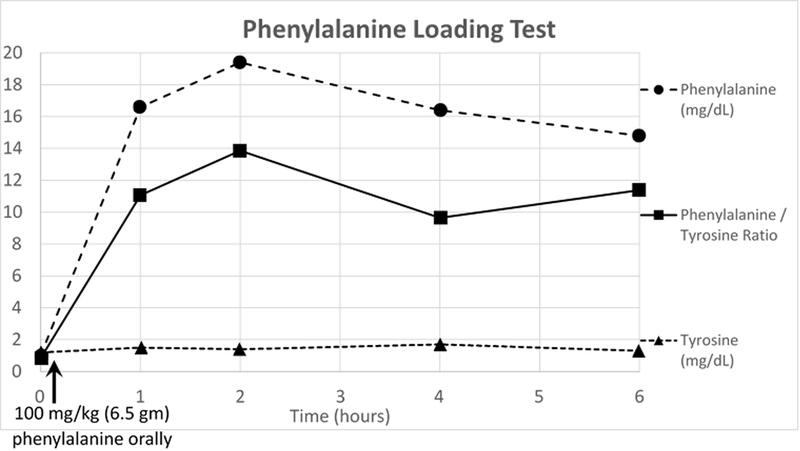

An otherwise healthy boy with appropriate development was first evaluated for gait abnormalities at 11 years old. He reportedly always carried his right arm at an abnormal angle when running and progressively developed increased gait disturbance of his right side over the preceding two years. Initially orthopedic evaluation raised concerns for tethered cord but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine was normal. Neurologic examination at initial presentation raised concern for right hemiparesis with gait characterized by clear circumduction and right arm flexion of the elbow when walking (Supplemental Video – left pane). MRI of his brain did not identify any findings accounting for his gait disturbances. Rheumatologic conditions, such as antiphospholipid syndrome, were not considered. In absence of a recognized treatable syndrome, no treatment trials were considered. He was referred to genetics where, given the nonspecific clinical and neuroimaging findings, the differential included both mitochondrial and nuclear etiologies. Broad molecular workup was pursued instead of biochemical evaluations. Exome sequencing and mitochondrial genome analysis were requested at a national reference laboratory. The mitochondrial genome reported one likely benign and several benign variants. The exome was reported as “negative: the exome analysis did not identify any variants that can explain the patient’s clinical phenotype.” but also included a table of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) labeled “genes unrelated to clinical phenotype.” This included a maternally inherited GCH1 variant (c.671A>G, p.K224R) and a paternally inherited GCH1 variant (c.312C>G, p.F104L). The maternally inherited variant is moderately uncommon, with a maximum subpopulation allele frequency of 0.1% in gnomAD [10], but has several computational predictors of deleteriousness. The paternally inherited allele is rarer, not found in gnomAD [10], and has multiple computational predictors of deleteriousness. Notably, both variants were previously reported in compound heterozygous states with other variants in patients with DOPA-responsive dystonia [8, 11, 12]. Additional phenotypic information was obtained from the patient including endorsement of significant diurnal variation of symptoms with improvement upon awakening in the morning and progressive worsening throughout the day, classic features of DOPA-responsive dystonia which was not documented in the original case history [13]. Family did not endorse any family history of parkinsonian features or movement disorders on either side of the family despite suggestion that carriers may be at risk of these symptoms [14]. There were no reported behavioral symptoms or sleep disorders. Neurologic reexamination demonstrated normal muscle bulk, normal tone aside from mild left wrist rigidity, no tremor, foot inversion on right at rest which increased with walking, and right arm dystonic posturing with flexion at the elbow. Curling and cramping of toes was noted bilaterally. With finger tapping, there was bradykinesia on the left with some pauses and dystonic posturing of the fingers. Reflexes noted 4 to 5 beats of clonus on the right. Plantar response was mute on right and down going on left. Given the high suspicion for DOPA-responsive dystonia, a treatable condition which may present with gait abnormalities, follow up biochemical evaluations were pursued. Family wished to avoid lumbar puncture, the gold standard for DOPA-responsive dystonia diagnosis, so less invasive evaluations were performed [15]. Qualitive urinary pterins reported mildly decreased ratio of neopterin to biopterin at 0.44 (age-appropriate cutoffs were not provided by reference laboratory; normal range is 0.3 to 5.5 in infants). Quantitative urinary neopterin was not available. Baseline phenylalanine levels were within normal range. A phenylalanine loading challenge was performed (figure 1) which demonstrated marked post-load elevation in phenylalanine and persistent elevation of the phenylalanine to tyrosine ratio over 6 hours with values above published cutoffs for pediatric and adult patients (ratio at 2 hours: 13.6, recommend pediatric cutoff: 3.8; ratio at 4 hours: 9.6, recommended cutoff: 7.8)[15, 16]. This confirmed the diagnosis of GCH1 deficiency without baseline hyperphenylalaninemia. A treatment trial with low dose (half 25 mg-100mg tablet three times each day) carbidopa-levodopa was initiated. Patient showed marked improvement of his gait disturbances within 2 hours of his first dose (Supplemental Video – right pane).

Figure 1:

6.5 gm (100 mg/kg based on weight of 65 kg) of phenylalanine was mixed with apple juice. Fingerstick blood spots were collected at baseline, 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, and 6 hours after drinking the mixture. This demonstrated an exaggerated increase in plasma phenylalanine levels, and persistent elevation of the phenylalanine to tyrosine ratio over the 6 hours above published cutoffs in both pediatric and adult populations at 2 hours, 4 hours, and 6 hours.

Discussion

The diagnostic workup of dystonia typically involves careful history and physical examination supported by metabolic and immune laboratory evaluations and may include treatment trial with levodopa. For atypical presentations where dystonia is not initially suspected, molecular diagnostics can provide answers. Exome sequencing is becoming a first-tier test for diagnosis of many pediatric neurologic disorders which can have non-specific and clinically indistinguishable presentations [3, 17]. Exome sequencing quality is related to the phenotypic information provided to laboratories for interpretation. Laboratories rely on provided clinical information to make decisions on variant reporting and classification. It is challenging within the ACMG variant classification guidelines to rank missense variants with moderate population frequencies as pathogenic or likely pathogenic [4]. This challenge is compounded for genes where both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive inheritance are possible and where phenotypic expression can range from mild to severe. Phenotypic descriptors can be interpreted differently by different laboratories, leading to questioning if genetic variants match clinical descriptions. For example, the phenotypic descriptors of “gait disturbance and knee and elbow contractures” and the overall relatively mild presentation in this case may not be interpreted as dystonia by a laboratory, even if that was the intended interpretation by the ordering provider. In this case, a child with a highly treatable genetic diagnosis had an exome reported as negative. Fortunately, diagnosis and initiation of treatment was not delayed due to careful clinical evaluation of reported uncertain results in the context of a more complete patient history. This case presents a cautionary tale for clinical molecular laboratory directors to broadly interpret phenotypic information provided by ordering clinicians and to consider the full phenotypic spectrum of gene dysregulation in their interpretation of potential relevance for return of genetic testing results. Furthermore, clinicians should provide complete and detailed phenotypic information to the laboratory when ordering genetic testing. Clinicians must pay careful attention to genetic variants which laboratories report as unrelated to presentation and pursue orthogonal confirmatory or biochemical testing when available to disambiguate variants of uncertain significance.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental File 1 – Video. Patient’s gait (left) prior to initiation of carbidopa-levodopa and (right) two hours after initiation of therapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient’s family for consenting to the publication of this case report and for providing the supplemental video. Dr. Berger’s work is supported in part through NIH Grant 1U01HG011745.

Funding/Support:

Dr. Berger receives funding from NIH grant, U01HG011745.

Role of Funder/Sponsor:

The NIH had no role in the design and conduct of this study.

Abbreviations:

- DRD

DOPA-responsive Dystonia

- GCH1

GTP cyclohydrolase 1

- VUS

variant of uncertain significance

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures (including financial disclosures): The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registration: Not applicable

References

- 1.Foster H, Drummond P, and Jandial S. Evaluation of gait disorders in children. BMJ Best Practice 2021. February 23, 2021 June 7, 2021]; Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/709. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanger TD, et al. , Definition and classification of hyperkinetic movements in childhood. Mov Disord, 2010. 25(11): p. 1538–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava S, et al. , Meta-analysis and multidisciplinary consensus statement: exome sequencing is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Genet Med, 2019. 21(11): p. 2413–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards S, et al. , Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med, 2015. 17(5): p. 405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Himmelreich N, Blau N, and Thony B, Molecular and metabolic bases of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiencies. Mol Genet Metab, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segawa M, Nomura Y, and Hayashi M, Dopa-responsive dystonia is caused by particular impairment of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons different from those involved in Parkinson disease: evidence observed in studies on Segawa disease. Neuropediatrics, 2013. 44(2): p. 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberger D, et al. , Dopa-responsive dystonia: mutation analysis of GCH1 and analysis of therapeutic doses of L-dopa. German Dystonia Study Group. Neurology, 2000. 55(11): p. 1735–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camargos ST, et al. , Novel GCH1 mutation in a Brazilian family with dopa-responsive dystonia. Mov Disord, 2008. 23(2): p. 299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scola RH, et al. , A novel missense mutation pattern of the GCH1 gene in dopa-responsive dystonia. Arq Neuropsiquiatr, 2007. 65(4B): p. 1224–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karczewski KJ, et al. , The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature, 2020. 581(7809): p. 434–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garavaglia B, et al. , GTP-cyclohydrolase I gene mutations in patients with autosomal dominant and recessive GTP-CH1 deficiency: identification and functional characterization of four novel mutations. J Inherit Metab Dis, 2004. 27(4): p. 455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clot F, et al. , Exhaustive analysis of BH4 and dopamine biosynthesis genes in patients with Dopa-responsive dystonia. Brain, 2009. 132(Pt 7): p. 1753–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segawa M, Hereditary progressive dystonia with marked diurnal fluctuation. Brain Dev, 2011. 33(3): p. 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mencacci NE, et al. , Parkinson’s disease in GTP cyclohydrolase 1 mutation carriers. Brain, 2014. 137(Pt 9): p. 2480–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leuzzi V, et al. , Urinary neopterin and phenylalanine loading test as tools for the biochemical diagnosis of segawa disease. JIMD Rep, 2013. 7: p. 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opladen T, et al. , Phenylalanine loading in pediatric patients with dopa-responsive dystonia: revised test protocol and pediatric cutoff values. J Inherit Metab Dis, 2010. 33(6): p. 697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manickam K, et al. , Exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability: an evidence-based clinical guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental File 1 – Video. Patient’s gait (left) prior to initiation of carbidopa-levodopa and (right) two hours after initiation of therapy.