Abstract

Objective:

To measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-reported life experiences in older adults with diabetes and obesity.

Methods:

Participants were surveyed in 2020 regarding negative and positive impacts of the pandemic across domains of personal, social, and physical experiences. A cumulative negative risk index (a count of all reported negative impacts of 46 items) and a positive risk index (5 items) were characterized in relation to age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, and multimorbidity.

Results:

Response rate was high (2950/3193, 92%), average age was 76 years, 63% were women, and 39% were from underrepresented populations. Women reported more negative impacts than men (6.8 vs 5.6, p<0.001, of 46 items) as did persons with a greater multimorbidity index (MMI, p<0.001). Participants reporting African American/Black race reported fewer negative impacts than White participants. Women also reported more positive impacts than men (1.9 vs 1.6, p< 0.001, of 5 items).

Conclusions:

Older adults with diabetes and obesity reported more positive impacts of the pandemic than negative impacts, relative to the number of positive (or negative) items presented. Some subgroups experienced greater negative impacts (e.g. women, greater MMI). Efforts to re-establish personal, social and physical health after the pandemic could target certain groups.

Keywords: COVID-19, geriatrics, race/ethnicity, obesity, diabetes

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the stay-at-home orders that were established in Spring 2020 to curtail it were anticipated to have negative impacts on the social, economic, emotional, and physical health of individuals (1). In particular, the requirement of physical distancing, and thereby disruption of traditional social networks, was thought to have the potential to adversely affect psychosocial wellbeing and health-related behaviors (2), particularly among those who are older and have chronic health conditions (3, 4). Examples of negative impacts include difficulty obtaining healthy foods and medications or getting routine medical care due to disruptions in transportation or fear of contracting the virus.

Few research teams were in the position to survey an existing well-characterized cohort of older adults at the time the COVID-19 pandemic began. Investigators of the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study identified an opportunity to examine the impact of the pandemic on social, economic, emotional, and physical health in the Look AHEAD cohort. The cohort includes large numbers of vulnerable older adults from multiple underrepresented race and ethnic groups with diabetes and obesity. Importantly, this set of traits characterize persons who have been disproportionately burdened by SARS-CoV-2 infection (5–9). Thus, this report describes the self-reported positive and negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in a cohort of approximately 3000 Look AHEAD participants who completed a questionnaire between July and December 2020. We hypothesized that older age, being female, being from underrepresented race/ethnic groups, and a greater number of multi-morbidities and obesity would be associated with more negative and less positive impacts of the pandemic.

Methods

Study Design

Look AHEAD was a randomized controlled trial conducted at 16 clinical sites in the United States. In brief, 5145 participants with diabetes and overweight or obesity were randomly assigned between 2001-2004 to an intensive lifestyle intervention or a control condition of diabetes support and education to assess the impact of the intervention on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Basic eligibility criteria included age 45-76 years, type 2 diabetes, BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (≥27 if taking insulin), blood pressure <160/100 mmHg, HbA1c ≤11%, triglycerides < 600 mg/dl, ability to complete a valid maximal exercise test, and an established relationship with a primary care provider. Detailed descriptions of the study design, interventions, and assessments have been published previously (10, 11). The intervention was stopped in 2012 due to finding no difference between randomized groups on the primary outcome (12); the study continued as an observational study with follow-up extending through 2020. At this time, there were 3193 participants active in Look AHEAD. All participants provided written informed consent and the protocol was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board.

Assessments during COVID-19

Look AHEAD mailed surveys that included a questionnaire assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic to 3193 participants between July and December 2020. The questionnaire was modelled after the Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII) and its Geriatric Adaptation (EPII-G). The EPII is a comprehensive assessment of pandemic-related experiences (13, 14) and is maintained in the National Institute of Health (NIH) Disaster Research Response (DR2) Repository of COVID - 19 Research Tools (https://dr2.nlm.nih.gov). Its geriatric adaptation assesses the impacts in older populations (15). A group of Look AHEAD investigators further adapted the 94 item EPII-G questionnaire by selecting a total of 47 items for inclusion and adding 4 questions resulting in a total of 51 items (Table S1). This adaptation allowed us to reduce participant burden and to minimize redundancy with other questionnaires in the packet (16). Questions were added to capture the impact of the pandemic on diabetes, a condition common to all Look AHEAD participants. The questionnaire inquired whether the coronavirus disease pandemic had changed people’s lives in seven domains – six negative domains (home life, economic status, emotional health and well-being, physical health problems, physical distancing and quarantine, and infection history) and one positive domain (positive change). Responses were reported as yes/no/not applicable. “Not applicable” responses were counted as “no”. Look AHEAD only inquired about the impact of each item on the respondent, not on the impact to ‘others in the home’ which is a part of the original EPII tool.

COVID infection was defined as a yes response to one or more of the following items in the infection history domain: tested and currently have this disease, tested positive for this disease but no longer have it, got medical treatment due to severe symptoms of this disease, and hospital stay due to this disease.

Other assessments

Measures obtained during COVID-19 were combined with data obtained previously in Look AHEAD. These included race/ethnicity, age, sex, socioeconomic status (SES), Look AHEAD treatment assignment, multimorbidity index, and BMI. Participants self-reported race and ethnicity by selecting from the following options: African American/Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, and Other. Similarly, ethnicity was queried as “Latino, Hispanic or Spanish origin” or not. This report stratifies the data on the four largest race/ethnic categories (African American/Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Hispanic, and White) and includes a fifth category (Other) that combines the smaller groups as well those who selected multiple race categories. We used a measure of financial assets as reported annually between baseline and year 8 (approximately 10 years prior to COVID −19) as an indicator of SES. Financial assets is an appropriate measure of SES to use in studies of older people as it measures accumulation of assets over the lifespan (17). The question asks, “How much money would you and others currently living in your household have if you cashed in all your checking and savings accounts, stocks and bonds, real estate, sold your home, your vehicles, and all your valuable possessions”. Eleven response categories were provided ranging from 0-$500 to $1,000,001 or more. Look AHEAD treatment assignment was the original randomization assignment (intervention vs control). A multimorbidity index was computed using a count of nine conditions ascertained at baseline and through 8 years of follow-up: cancer, cardiac arrhythmia, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, depression, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and stroke (18). (Diabetes and obesity were not counted as they were common to all participants.) Higher scores refer to greater multimorbidity. BMI was calculated from weight (kg) and height (m) measured in the clinic visit immediately preceding COVID-19 (within 2 years).

Analysis Plan

The primary measure of interest was a cumulative negative risk index which counts the total number of affirmative responses to the 46 negative impact items. This risk index has been used previously with the EPII questionnaire (19, 20). Domain-specific risk indices were also calculated across the six negative domains and one positive domain. Responses of ‘no’ and ‘not applicable’ were combined as a ‘no’ response. Secondary measures of interest were the 51 individual items.

We hypothesized that the risk indices would differ across subgroups including race/ethnicity, sex, Look AHEAD treatment assignment, age, BMI, and multimorbidity index. These hypotheses were based upon the disproportionate burden of COVID experienced by older adults, underrepresented populations, those with higher BMI, and/or with multiple chronic conditions. Assignment to the intervention group in Look AHEAD may have led to improved self-care strategies which could be beneficial in managing the physical and social distancing requirements. Furthermore, because race/ethnicity can serve as a proxy for economic measures (among others, social, cultural, etc.), we further evaluated associations that were observed for race/ethnicity by adjusting for assets. Response sets for assets were collapsed into three groups approximately representing tertiles ($0 - $100,000; $100,001 - $500,000; > $500,000). The question was not answered by 20%; thus, analyses that adjusted for assets have a reduced sample size.

Mean (and median) cumulative negative risk index and domain-specific indices are presented by race/ethnicity and separately for men and women. Due to the large number of zeros for some domains (i.e. no negative impacts reported), we also present percent of scores greater than zero. Poisson regression was used to model the risk indices on race/ethnicity, sex, treatment assignment, and continuous variables of age, BMI, and multimorbidity index. Negative binomial regression was used in instances where the data were over-dispersed. Effect sizes are presented as rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Logistic regression was used to characterize the odds of each of the 51 items by subgroup. Due to the large number of statistical comparisons in the analysis of the 51 items individually, the p-value for significance for these analyses was set at 0.001.

Results

This report includes 2950 (92%) of the 3193 Look AHEAD participants who received and returned a questionnaire. Ninety percent of the questionnaires were completed between 30 July and 28 October 2020 (Table S2). On average, the cohort was 76 years old (range 62 – 94 years), included more women than men (63%), and included a large number of participants from underrepresented populations (1158/2950 or 39%) (Table 1). The cohort had high levels of overweight (26%) and obesity (69%) and all had diabetes. Current or prior COVID infections were reported by 5.6%, and were highest in the two American Indian sites (11% and 21%) (Table S2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Look AHEAD Cohort Participating in COVID Questionnaire (June - December 2020), by Race/Ethnicity

| Overall | African American/Black | AI/AN | Hispanic | White | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2950 | 490 | 167 | 407 | 1792 | 94 |

| Age, yrs | 75.8 ± 6 (62.2, 93.7) | 75.4 ± 5.9 (63.2, 93.7) | 71.6 ± 6.1 (62.2, 90.6) | 75 ± 5.5 (63.2, 92.2) | 76.5 ± 6 (62.9, 93.5) | 75.6 ± 5.7 (63.7, 88.5) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1091 (37%) | 103 (21%) | 33 (19.8%) | 101 (24.8%) | 819 (45.7%) | 35 (37.2%) |

| Female | 1859 (63%) | 387 (79%) | 134 (80.2%) | 306 (75.2%) | 973 (54.3%) | 59 (62.8%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.6 ± 6.2 (17.4, 62.8) | 34.2 ± 6.3 (18.2, 55.8) | 33 ± 7.6 (17.8, 62.3) | 33.1 ± 6 (20.9, 62.8) | 33.7 ± 6.1 (17.4, 60.3) | 32.7 ± 6 (21.8, 48.5) |

| BMI group | ||||||

| Underweight/Normal (< 25 kg/m2) | 145 (5.4%) | 29 (6.4%) | 19 (11.7%) | 23 (5.8%) | 64 (4%) | 10 (11.4%) |

| Overweight (25.0 - 29.9 kg/m2) | 692 (25.7%) | 92 (20.3%) | 50 (30.7%) | 110 (27.9%) | 416 (26.1%) | 24 (27.3%) |

| Obese (> 30 kg/m2) | 1855 (68.9%) | 333 (73.3%) | 94 (57.7%) | 261 (66.2%) | 1113 (69.9%) | 54 (61.4%) |

| Multimorbidity Index (continuous) | 2.9 ± 1 (0, 7) | 2.8 ± 1 (1, 6) | 2.6 ± 0.9 (0, 5) | 2.8 ± 0.9 (1, 6) | 3 ± 1.1 (0, 7) | 2.9 ± 1 (1, 5) |

| Multimorbidity Index | ||||||

| Low (≤ 3) | 2217 (75.2%) | 398 (81.2%) | 142 (85%) | 323 (79.6%) | 1283 (71.7%) | 71 (75.5%) |

| High (> 3) | 730 (24.8%) | 92 (18.8%) | 25 (15%) | 83 (20.4%) | 507 (28.3%) | 23 (24.5%) |

| Asset Categories | ||||||

| $0 - $100,000 | 680 (23.1%) | 174 (35.5%) | 106 (63.5%) | 167 (41%) | 212 (11.8%) | 21 (22.3%) |

| $100,001 - $500,000 | 892 (30.2%) | 161 (32.9%) | 43 (25.7%) | 94 (23.1%) | 570 (31.8%) | 24 (25.5%) |

| $500,000+ | 839 (28.4%) | 69 (14.1%) | 6 (3.6%) | 44 (10.8%) | 683 (38.1%) | 37 (39.4%) |

| Missing | 539 (18.3%) | 86 (17.6%) | 12 (7.2%) | 102 (25.1%) | 327 (18.2%) | 12 (12.8%) |

| COVID Infection | ||||||

| Yes | 165 (5.6%) | 27 (5.5%) | 26 (15.6%) | 33 (8.1%) | 77 (4.3%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| No | 2775 (94.4%) | 461 (94.5%) | 141 (84.4%) | 372 (91.9%) | 1710 (95.7%) | 91 (97.8%) |

| Randomization Arm | ||||||

| Control | 1428 (48.4%) | 241 (49.2%) | 84 (50.3%) | 188 (46.2%) | 869 (48.5%) | 46 (48.9%) |

| Intervention | 1522 (51.6%) | 249 (50.8%) | 83 (49.7%) | 219 (53.8%) | 923 (51.5%) | 48 (51.1%) |

The average cumulative negative risk index was 6.3 of 46 possible life experiences (Table 2). The average positive risk index was 1.8 of five possible life experiences. Thus, on average, relatively more of the possible positive experiences were endorsed (36%) than of the possible negative experiences (14%). Participants rarely reported negative impacts in the home life or economic domains.

Table 2.

Cumulative Negative Risk Index and Domain-Specific Risk Indices, by Race/Ethnicity

| Overall | African American/Black | AI/AN | Hispanic | White | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2950 | 490 | 167 | 407 | 1792 | 94 |

| Cumulative Negative Effects Score (N) | 2940 | 486 | 167 | 407 | 1787 | 93 |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 6.3 ± 4 (0, 28) | 6.1 ± 4.2 (0, 28) | 6.2 ± 4.5 (0, 24) | 6.7 ± 4.3 (0, 27) | 6.3 ± 3.8 (0, 25) | 7.3 ± 4.7 (0, 25) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3, 9) | 6 (3, 9) | 5 (3, 9) | 6 (3, 9) | 6 (4, 8) | 6 (4, 11) |

| % Score > 0 | 2772 (94.3%) | 446 (91.8%) | 157 (94%) | 389 (95.6%) | 1692 (94.7%) | 88 (94.6%) |

| % Score > 10 | 416 (14.1%) | 69 (14.2%) | 23 (13.8%) | 72 (17.7%) | 225 (12.6%) | 27 (29%) |

| Domain: Home Life (N) | 2949 | 489 | 167 | 407 | 1792 | 94 |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 0.3 ± 0.7 (0, 6) | 0.3 ± 0.6 (0, 5) | 0.3 ± 0.7 (0, 5) | 0.3 ± 0.7 (0, 5) | 0.3 ± 0.6 (0, 6) | 0.4 ± 0.9 (0, 6) |

| % Score > 0 | 659 (22.3%) | 91 (18.6%) | 35 (21%) | 93 (22.9%) | 415 (23.2%) | 25 (26.6%) |

| Domain: Economic (N) | 2949 | 489 | 167 | 407 | 1792 | 94 |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 0.3 ± 0.7 (0, 4) | 0.3 ± 0.7 (0, 4) | 0.4 ± 0.8 (0, 3) | 0.7 ± 1.1 (0, 4) | 0.2 ± 0.5 (0, 4) | 0.4 ± 0.8 (0, 4) |

| % Score > 0 | 636 (21.6%) | 106 (21.7%) | 41 (24.6%) | 141 (34.6%) | 321 (17.9%) | 27 (28.7%) |

| Domain: Emotional Health and Well Being (N) | 2944 | 488 | 167 | 407 | 1789 | 93 |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 1.5 ± 1.3 (0, 6) | 1.4 ± 1.2 (0, 5) | 1.1 ± 1.2 (0, 5) | 1.5 ± 1.3 (0, 5) | 1.5 ± 1.3 (0, 6) | 1.8 ± 1.5 (0, 6) |

| % Score > 0 | 2182 (74.1%) | 353 (72.3%) | 97 (58.1%) | 301 (74%) | 1358 (75.9%) | 73 (78.5%) |

| Domain: Physical Health Problems (N) | 2943 | 488 | 167 | 407 | 1788 | 93 |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 2.2 ± 1.4 (0, 10) | 2.2 ± 1.5 (0, 10) | 1.9 ± 1.4 (0, 6) | 2.1 ± 1.4 (0, 7) | 2.3 ± 1.4 (0, 7) | 2.5 ± 1.6 (0, 6) |

| % Score > 0 | 2527 (85.9%) | 410 (84%) | 135 (80.8%) | 340 (83.5%) | 1563 (87.4%) | 79 (84.9%) |

| Domain: Physical Distancing and Quarantine (N) | 2946 | 489 | 167 | 407 | 1790 | 93 |

| Mea ± SD (Range) | 1.6 ± 1.4 (0, 7) | 1.3 ± 1.4 (0, 7) | 1.4 ± 1.8 (0, 7) | 1.5 ± 1.5 (0, 6) | 1.6 ± 1.4 (0, 7) | 1.8 ± 1.6 (0, 6) |

| % Score > 0 | 2037 (69.1%) | 305 (62.4%) | 85 (50.9%) | 259 (63.6%) | 1322 (73.9%) | 66 (71%) |

| Domain: Infection History (N) | 2946 | 489 | 167 | 407 | 1790 | 93 |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 0.5 ± 0.9 (0, 8) | 0.6 ± 1 (0, 8) | 1.1 ± 1.2 (0, 6) | 0.6 ± 1.1 (0, 8) | 0.4 ± 0.8 (0, 7) | 0.4 ± 0.8 (0, 3) |

| % Score > 0 | 876 (29.7%) | 175 (35.8%) | 99 (59.3%) | 154 (37.8%) | 419 (23.4%) | 29 (31.2%) |

| Domain: Positive Change (N) | 2945 | 488 | 167 | 407 | 1789 | 94 |

| Mean ± SD (Range) | 1.8 ± 1.3 (0, 5) | 2.1 ± 1.3 (0, 5) | 1.4 ± 1.3 (0, 5) | 2.1 ± 1.2 (0, 5) | 1.7 ± 1.2 (0, 5) | 2.2 ± 1.3 (0, 5) |

| % Score > 0 | 2389 (81.1%) | 421 (86.3%) | 106 (63.5%) | 356 (87.5%) | 1424 (79.6%) | 82 (87.2%) |

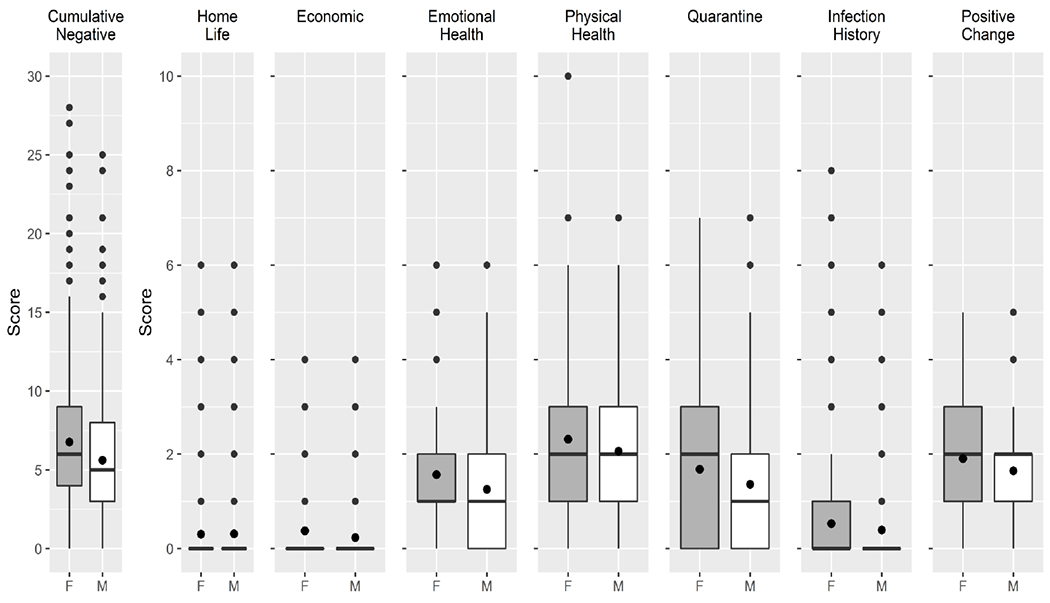

The average cumulative negative risk index was higher in women than in men: 6.8 versus 5.6 (Figure 1). This pattern was consistent with women reporting on average 1 or more negative experiences than men across all race/ethnic groups except the ‘other’ group (Tables S3a and S3b). In a multivariate model, younger age (RR=0.995, p=0.03), female sex (RR=1.20, p<0.001) and a higher multimorbidity index (RR=1.08, p<0.001) were associated with a higher cumulative negative risk index (Table 3a). African American/Black race was associated with a lower risk index (RR=0.93) and Other race was associated with a higher risk index (RR=1.16) relative to the White race group. BMI and Look AHEAD treatment assignment were not associated with the cumulative negative risk index.

Figure 1: Cumulative Negative Risk Index and Domain-Specific Risk Indices, by Gender.

The box represents the interquartile range (IQR), split with a line to represent the median and a diamond to represent the mean. The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR, with outliers represented by circles

Table 3a.

Multivariable Model for Cumulative Negative Risk Index

| Overall N = 2682 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Rate Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

| Treatment Group | 0.499 | |

| Control | REF | |

| Intervention | 1.02 (0.97 – 1.07) | |

| Age (yrs) | 0.995 (0.991 – 1.000) | 0.033 |

| Gender | < 0.001 | |

| Male | REF | |

| Female | 1.20 (1.14 – 1.27) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.016 | |

| White | REF | |

| African American/Black | 0.93 (0.87 – 1.00) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.96 (0.86 – 1.07) | |

| Hispanic | 1.04 (0.97 – 1.12) | |

| Other | 1.16 (1.01 – 1.33) | |

| Multimorbidity Index | 1.08 (1.05 – 1.10) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.004 (1.00 – 1.01) | 0.079 |

Domain-specific risk indices yielded different findings than the cumulative index although some patterns emerged. In most domains, women had higher domain-specific risk indices than men (Figure 1). Consistent with the findings for the cumulative negative risk index, in the multivariate model, female sex and higher multimorbidity index were associated with higher risk indices in every negative risk domain except for home life and infection history (Table 3b).

Table 3b.

Multivariable Models for Domain-Specific Risk Indices

| Home Life | Economic | Emotional Health and Well Being | Physical Health Problems | Physical Distancing and Quarantine | Infection History | Positive Change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2690 | N = 2690 | N = 2686 | N = 2685 | N = 2688 | N = 2688 | N = 2687 | ||||||||

| Variable | Rate Ratio | p-value | Rate Ratio | p-value | Rate Ratio | p-value | Rate Ratio | p-value | Rate Ratio | p-value | Rate Ratio | p-value | Rate Ratio | p-value |

| Treatment Group | 0.870 | 0.035 | 0.575 | 0.514 | 0.604 | 0.814 | 0.367 | |||||||

| Control | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||||

| Intervention | 1.01 (0.86 – 1.19) | 1.20 (1.01 – 1.42) | 0.98 (0.92 – 1.05) | 1.02 (0.97 – 1.07) | 1.02 (0.95 – 1.09) | 1.02 (0.88 – 1.17) | 1.03 (0.97 – 1.08) | |||||||

| Age (yrs) | 0.98 (0.97 – 1.00) | 0.052 | 1.01 (0.99 – 1.02) | 0.278 | 0.985 (0.980 – 0.991) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.997 – 1.006) | 0.525 | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.003) | 0.333 | 0.98 (0.97 – 1.00) | 0.026 | 0.994 (0.990 – 1.000) | 0.033 |

| Gender | 0.639 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.103 | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Male | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||||

| Female | 0.96 (0.80 – 1.14) | 1.39 (1.15 – 1.68) | 1.26 (1.17 – 1.35) | 1.13 (1.07 – 1.20) | 1.29 (1.19 – 1.40) | 1.14 (0.97 – 1.33) | 1.11 (1.05 – 1.19) | |||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.341 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||

| White | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||||

| AA/Black | 0.84 (0.66 – 1.07) | 1.28 (1.00 – 1.63) | 0.89 (0.81 – 0.98) | 0.94 (0.87 – 1.01) | 0.77 (0.69 – 0.85) | 1.67 (1.37 – 2.02) | 1.19 (1.11 – 1.29) | |||||||

| AI/AN | 1.04 (0.73 – 1.48) | 1.93 (1.37 – 2.72) | 0.67 (0.57 – 0.79) | 0.84 (0.75 – 0.95) | 0.82 (0.70 – 0.97) | 2.77 (2.13 – 3.60) | 0.75 (0.66 – 0.87) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 1.06 (0.84 – 1.35) | 3.06 (2.48 – 3.79) | 0.98 (0.89 – 1.07) | 0.90 (0.83 – 0.97) | 0.87 (0.78 – 0.97) | 1.76 (1.44 – 2.14) | 1.15 (1.06 – 1.25) | |||||||

| Other | 1.31 (0.85 – 2.00) | 1.85 (1.20 – 2.87) | 1.18 (1.00 – 1.40) | 1.11 (0.97 – 1.27) | 1.10 (0.91 – 1.33) | 1.20 (0.79 – 1.81) | 1.24 (1.07 – 1.43) | |||||||

| Multimorbidity Index | 1.17 (1.08 – 1.27) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.06 – 1.25) | 0.001 | 1.11 (1.07 – 1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.03 – 1.08) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.02 – 1.10) | 0.001 | 0.998 (0.93 – 1.07) | 0.952 | 0.97 (0.95 – 1.00) | 0.067 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.02) | 0.533 | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.01) | 0.948 | 0.998 (0.992 – 1.003) | 0.393 | 1.01 (1.004 – 1.011) | < 0.001 | 1.003 (1.00 – 1.009) | 0.248 | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.02) | 0.441 | 0.997 (0.992 – 1.001) | 0.160 |

There were a range of effects in the negative risk domains across race/ethnicity. All underrepresented groups reported higher, and often considerably higher, negative impacts in the economic status and infection history domains relative to White participants. Conversely, nearly all underrepresented groups reported lower negative impacts in the emotional health and well-being, physical health problems, and physical distancing and quarantine domains relative to White participants. These domain-specific multivariate models were further adjusted for financial assets to assess whether race/ethnicity was serving as a proxy for SES. Adjusting for assets only partially blunted the association with race/ethnicity (not shown).

Other differences among subgroups were seen only within specific domains (Table 3b). Younger age was associated with higher risk indices in the emotional health and wellbeing domain and in the infection history domain. Greater BMI was associated only with higher risk indices for the physical health problems domain. Look AHEAD intervention treatment assignment was associated only with higher risk indices for the economic domain.

Regarding the positive change domain (Table 3b), younger participants, females, and participants self-identified as African American/Black, Hispanic, or Other (compared to White participants) had higher risk indices (greater positive change). American Indian participants had lower risk indices (lesser positive change) compared to White participants, and by extension, to all other underrepresented groups (who were more positive than White participants).

Item-specific frequencies are presented in Table S4. The most frequent negative impacts, endorsed by >50% of the cohort included: more time sitting down or being sedentary (72%); less physical activity or exercise (65%); more time spent on screens and devices (65%); and limited physical closeness with child or loved one due to concerns of infection (51%). The most frequent positive impacts included more time doing enjoyable activities, e.g., reading, puzzles (67%); and more quality time with family or friends in person or from a distance (62%).

Table S4 also shows contrasts for sex, race/ethnicity and multimorbidity index for each item. The strongest effects were observed for items in the economic domain where Hispanic participants had significantly greater odds of endorsing these negative impacts relative to White participants. American Indian participants had significantly greater odds of endorsing negative impacts in the infection history domain relative to White participants, including a nearly 9 times greater odds of experiencing the death of a close friend or family member.

Discussion

Older persons, persons from underrepresented race/ethnic groups, and persons with diabetes and obesity have been disproportionately burdened by SARS-CoV-2 infection, serious illness, and mortality (5–9). This report enabled an assessment of pandemic-related experiences among such groups. Look AHEAD represents a large cohort of older adults (average age 76 years) with type 2 diabetes and obesity or overweight, with large numbers of individuals of Hispanic ethnicity (n=407) and individuals reporting race as American Indian (n=167) or African American/Black (n=490). The key points of this analysis were (1) the frequent endorsement of positive impacts of the pandemic, relative to the negative impacts, and (2) the observation that both positive and negative impacts were reported differentially across various subgroups.

This study utilized a modification of the Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory – Adapted for Geriatric Populations (EPII-G) which is a comprehensive assessment of pandemic-related experiences. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has published on the experiences of an older adult cohort in response to COVID-19 utilizing this instrument. An ethnically diverse sample of 1608 adults aged ≥55 years (average 67 years) in the US and Latin America showed the differential impact of the pandemic on the well-being of these groups (19). Similar to our report, people of Latino ethnicity reported higher economic impact compared to non-Hispanic White participants, and Black and Latino participants reported more positive change. Several publications using the EPII have been limited to young adults (20, 21). College-aged women reported more negative impacts of the pandemic than men, irrespective of race or ethnicity, and women and Hispanic participants were more likely to report positive changes (20). The most frequent negative and positive impacts endorsed by these college students overlapped considerably with those reported by the older aged Look AHEAD cohort. From these few studies utilizing the EPII, similar observations have been made regarding sex and race/ethnicity, despite the disparate ages of the respondents.

The survey used in the present study focused primarily on negative impacts of the pandemic as indicated by 46 negative items, compared to only five items focused on positive impacts. Despite this, participants selected having experienced (on average) 1.8 positive impacts, compared to 6.3 negative impacts. Our interpretation is that, on balance, this vulnerable aging cohort with diabetes and obesity identified with positive impacts relatively more often than negative impacts. This observation is consistent with another study in an older adult population (19). On the other hand, college students reported equally high levels of negative to positive impacts (20). Thus, while the pandemic has been a catastrophic event worldwide, costing nearly 1 million US lives to date (22), the impact on individuals is highly variable. Older adults may be more likely to find the “silver lining”.

Despite women reporting greater positive experiences than men in the positive change domain, women reported more negative impacts of the pandemic than men. These observations are consistent with those of the sample of 909 college students in which women, irrespective of race or ethnicity, reported higher disruptions related to COVID-19 than men and were also more likely to report positive changes than men (20). In our previous work in the Look AHEAD cohort, we reported that women, relative to men, felt a greater sense of threat from the pandemic (16). Others have reported that women were more concerned about the pandemic, and thus reported more compliance with public health and social distancing measures (23). These factors may explain our findings that women reported greater negative impacts of the pandemic on physical health (e.g., less physical activity or exercise) and physical distancing and quarantine (e.g., limited physical closeness with child or loved one due to concerns of infection). Women also had more emotional impacts from the pandemic than men. This is consistent with our previous findings from this cohort that during the pandemic, women reported higher levels of depressive symptoms, loneliness, and anxiety than men (16). Differences between men and women in the impact of the pandemic on emotional health and well-being may be related to gender variations in the way emotions are identified and expressed, genetic or physiological factors, and family caregiving and household responsibilities. Women usually have larger social networks than men, and more multifaceted sources of support (24). The pandemic likely disrupted these networks and the negative impact on mental health may have been further exacerbated because older women are more likely to live alone than men. However, further studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

In this study, the rate of COVID infections differed across US communities and race/ethnic groups, with individuals from underrepresented populations more commonly affected. Perhaps due to the disproportionate burden of COVID infection, as well as social, cultural, and economic differences across race and ethnic groups in the US, differences (sometimes striking) in both reported positive and negative experiences were observed. For example, participants from underrepresented groups endorsed greater negative experiences in the domains of economic status and infection history compared to White participants. The finding of greater risk in the domain of infection history is consistent with national data regarding a 2-3 fold greater risk of contracting COVID-19 for persons from underrepresented US populations compared to non-Hispanic White people (6). On the other hand, participants from underrepresented groups endorsed fewer negative experiences in the domains of emotional health/well-being, physical health problems, and physical distancing/quarantine compared to White participants. Participants from underrepresented groups also endorsed more positive experiences (e.g., developed new hobbies or activities) compared to White participants. These race/ethnic differences across all domains were further evaluated to assess whether a pre-pandemic assessment of assets explained the race/ethnic differences. For the most part, the findings persisted leaving us to conclude that social, cultural, or differences in levels of exposure to the virus drove the differences across race/ethnic groups in our cohort.

The observation that the underrepresented groups compared to White participants reported fewer negative experiences (in some domains) and more positive experiences was counter to our hypothesis. The literature, however, supports these findings. Babulal and colleagues (19) reported greater positive change in Latino and Black participants compared to non-Latino white, ages > 55 years; similar finding were reported in the college-aged sample (20). Two other studies concur with an observation of lower levels of distress and worry among Black compared to White individuals during COVID-19 (25, 26). Possible explanations for difference in resilience include a greater life purpose or satisfaction (27, 28), social support, or coping skills in some groups and/or cultures, all of which require further exploration.

Multimorbidity was common in the Look AHEAD cohort. Nearly all participants had at least two comorbid conditions – diabetes and overweight/obesity. One-quarter of the cohort had three or more additional chronic conditions. Persons with a high multimorbidity index (>3) consistently reported greater negative impacts of the pandemic across all the risk domains except infection history. Regarding specific life experiences, those with a high multimorbidity index were nearly three times more likely to report being unable to get home-based paid help for care for disability, chronic illness, or dementia.

Older age, higher BMI, and assignment to the control intervention were hypothesized to be associated with greater negative impacts of the pandemic. Older age was not associated with greater negative impacts as we had hypothesized. Others have observed that the pandemic had greater impact on the mental health among younger persons, those living with young children, and those employed (29). Higher BMI was associated with greater negative impacts only in the physical health problems domain. We attribute the mostly null associations with BMI to be due to a restricted distribution of BMI in the Look AHEAD cohort (69% with obesity and only 5% with BMI < 25 kg/m2). Finally, Look AHEAD treatment assignment also lacked association with reported impacts of the pandemic, dismissing our hypothesis that the behaviors and skills learned during the Look AHEAD trial would translate beyond its impact on weight loss.

Individuals reported substantial impacts to their lives that occurred since the coronavirus disease pandemic began. The three most frequently endorsed negative impacts, reported by 65% or more included: more time sitting down or being sedentary, less physical activity or exercise, and spending more time on screens and devices – all of which can have detrimental long-term impacts on the health of older persons with diabetes and obesity (30). On the other hand, difficulty in obtaining diabetes specific care was infrequently reported, a finding which may underscore the uniquely motivated population of adults with diabetes participating in this long-term study.

Strengths of this study include a large well-characterized cohort with diversity across race and ethnicity. The survey, conducted within months of the initial stay-at-home orders implemented in the US in March-May 2020, yielded a high response rate (92%) and high levels of item completeness (>99% overall). A panel of standardized measures obtained in previous visits of the Look AHEAD cohort enriched the data set (BMI, multimorbidity index, and financial assets).

There are also limitations. These results reflect one period of time in 16 US communities, whereas the pandemic has been dynamic in its impact over time and by location. Another limitation is that we do not have a control period prior to the pandemic with which to compare the endorsement of these experiences. In addition, the instrument used in this study was not validated; however, neither was the tool from which it was adapted. As done in prior publications with the EPII instrument, we focused on a measure of cumulative negative impacts and positive impacts; this approach weights all items equally, although some items would likely have greater impact than others. Also, the results from this sample of clinical trial participants may not be generalizable to the population of older adults. Indeed, Look AHEAD participants report greater wealth than US seniors (31) and are likely to be more health conscious which may influence how they perceive the pandemic has influenced their lives. Finally, despite the intent to measure the impact of the pandemic on the lives of an aging, multi-ethnic cohort in late 2020, there were other events that likely affected the lives of these individuals, including significant nationwide attention to police brutality and a divisive national election. We are unable to separate the impact of these concurrent events from those attributable to the pandemic.

In conclusion, we studied the negative and positive impacts of the pandemic in a large cohort of older adults from communities across the US, shortly after the period of strict lock-down. The cohort was diverse with regard to race and ethnicity and had multiple chronic conditions, including diabetes and obesity/overweight, all conditions which increase the risk of COVID-19 disease and severity. We observed that positive impacts of the pandemic were reported more often than negative impacts, relative to the number of positive (or negative) items presented. Women and those with more comorbidities reported more negative impacts of the pandemic. Participants from underrepresented groups, despite reporting a higher COVID infection history, appear to have been more resilient to the pandemic, reporting more positive impacts overall, and fewer negative impacts than White participants in several domains. In summary, some groups appear more resilient to the negative personal and social impacts of the pandemic. Identifying the factors that lead to resilience may suggest strategies that support the resumption of healthy lives following the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject?

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused havoc worldwide.

It is unknown how the public health measures used to mitigate the pandemic will impact the health and wellness of populations.

Few studies have examined the personal and social impacts experienced by persons of older age or with chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity.

What are the new findings in your manuscript?

Older adults report both negative and positive impacts of the pandemic.

Women and persons with multiple chronic conditions reported a greater number of negative personal and social impacts of the pandemic.

Underrepresented groups reported lower negative impacts in the emotional health and well-being domain, and greater positive change compared to White participants.

How might your results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

Future research may evaluate why different groups appear resilient to the negative personal and social impacts of the pandemic and how this may mediate or protect against mental health consequences.

Data sharing statement.

Because the Look AHEAD study originated as a clinical trial (2001 – 2012), we are identifying it as a clinical trial. It has since transitioned into an observational study. The data presented in this manuscript are part of the observational study phase of Look AHEAD.

- Will individual de-identified participant data be available (including data dictionaries)? If so, what data in particular will be shared and when (start and end dates)?

- Participant data are broadly available through the NIDDK Data Repository and these data represent the period 2001 – 2012.

- What other documents will be available (e.g., study protocol, statistical analysis plan)?

- Look AHEAD study documents are available on the clinicaltrials.gov website. These include the study protocol and a statistical analysis plan.

- With whom will data be shared, for what types of analyses, and by what mechanism?

- NIDDK requires that an investigator provide an IRB approval for data to be released from its repository.

Funding and Support:

Funded by the National Institutes of Health through cooperative agreements with the National Institute on Aging: AG058571 and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. Additional funding was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (RR025758-04); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153) and NIH grant (DK 046204); the VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; and the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346).

Disclosures:

Ariana Chao reports grants from Eli Lilly and Company and WW International, Inc. (formerly Weight Watchers), outside the submitted work. Jeanne Clark has served on scientific advisory boards for Boehringer-Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk. Thomas Wadden serves on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and WW. Rena Wing serves on the advisory board for NOOM. The other authors report no disclosures. Signed duality of interest forms from all authors are available at www.lookaheadtrial.org.

Footnotes

Clinical trials registration: NCT00017953

References

- 1.Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int J Surg. 2020. Jun;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. Epub 2020 Apr 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long E, Patterson S, Maxwell K, Blake C, Bosó Pérez R, Lewis R, McCann M, Riddell J, Skivington K, Wilson-Lowe R, Mitchell KR. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2022. Feb;76(2):128–132. doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-216690. Epub 2021 Aug 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith ML, Steinman LE, Casey EA. Combatting Social Isolation Among Older Adults in a Time of Physical Distancing: The COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox. Front Public Health. 2020. Jul 21;8:403. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00403. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLeod S, Tkatch R, Kraemer S, Fellows A, McGinn M, Schaeffer J, Yeh CS. COVID-19 Era Social Isolation among Older Adults. Geriatrics (Basel). 2021. May 18;6(2):52. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics6020052. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregg EW, Sophiea MK, Weldegiorgis M. Diabetes and COVID-19: Population Impact 18 Months into the Pandemic. Diab Care 2021;44:1916–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Accessed 2/7/2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html#print

- 7.Gao M, Piernas C, Astbury NM, Hippisley-Cox J, O’Rahilly S, Aveyard P, Jebb SA. Associations between body-mass index and COVID-19 severity in 6·9 million people in England: a prospective, community-based, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021. Jun;9(6):350–359. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00089-9. Epub 2021 Apr 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kompaniyets L, Goodman AB, Belay B, Freedman DS, Sucosky MS, Lange SJ, Gundlapalli AV, Boehmer TK, Blanck HM. Body Mass Index and Risk for COVID-19-Related Hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit Admission, Invasive Mechanical Ventilation, and Death - United States, March-December 2020. MMWR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Z, Yang Y, Zhang J. Obesity is associated with severe disease and mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021. Aug 4;21(1):1505. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11546-6. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Look AHEAD Research Group, Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, Jakicic J, Rejeski J, Williamson D, Berkowitz RI, Kelley DE, Tomchee C, Hill JO, Kumanyika S. The Look AHEAD Study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(5):737–52. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Look AHEAD Research Group, Bray G, Gregg E, Haffner S, Pi-Sunyer XF, Wagenknecht LE, Walkup M, Wing R. Baseline characteristics of the randomised cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Research Study. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2006;3(3):202–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Look AHEAD Research Group, Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Coday M, Crow RS, Curtis JM, Egan CM, Espeland MA, Evans M, Foreyt JP, Ghazarian S, Gregg EW, Harrison B, Hazuda HP, Hill JO, Horton ES, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Jeffery RW, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, Kitabchi AE, Knowler WC, Lewis CE, Maschak-Carey BJ, Montez MG, Murillo A, Nathan DM, Patricio J, Peters A, Pi-Sunyer X, Pownall H, Reboussin D, Regensteiner JG, Rickman AD, Ryan DH, Safford M, Wadden TA, Wagenknecht LE, West DS, Williamson DF, Yanovski SZ. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013. Jul 11;369(2):145–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. Epub 2013 Jun 24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2014. May 8;370(19):1866. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grasso DJ, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Ford JD, Carter AS. The Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII). 2020. University of Connecticut School of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grasso DJ, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Goldstein BL, Ford JD. Profiling COVID-Related Experiences in the United States with the Epidemic - Pandemic Impacts Inventory: Linkages to psychosocial functioning. Brain Behav. 2021. Jul 3:e02197. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning KJ, Steffens DC, Grasso DJ, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Ford JD, Carter AS. (2020). The Epidemic – Pandemic Impacts Inventory Geriatric Adaptation (EPII-G). University of Connecticut School of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao AM, Wadden TA, Clark JM, Hayden KM, Howard MJ, Johnson KC, Laferrère B, McCaffery JM, Wing RR, Yanovski SZ, Wagenknecht LE. Changes in the prevalence of symptoms of depression, loneliness, and insomnia in US older adults with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic: The Look AHEAD Study. Diab Care, 2021, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert S, House JS. SES differentials in health by age and alternative indicators of SES. J Aging Health. 1996;8:359–88. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espeland MA, Gaussoin SA, Bahnson J, et al. Impact of an 8-year intensive lifestyle intervention on an index of multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:2249–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babulal GM, Torres VL, Acosta D, Agüero C, Aguilar-Navarro S, Amariglio R, Aya Ussui J, Baena A, Bocanegra Y, Dozzi Brucki SM, Bustin J, Cabrera DM, Custodio N, Diaz MM, Peñailillo LD, Franco I, Gatchel JR, Garza-Naveda AP, Lara MG, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez L, Guzmán-Vélez E, Hanseeuw BJ, Jimenez-Velazquez IZ, Rodríguez TL, Llibre-Guerra J, Marquine MJ, Martinez J, Medina LD, Miranda-Castillo C, Paredes AM, Munera D, Nuñez-Herrera A, Okada de Oliveira M, Palmer-Cancel SJ, Pardilla-Delgado E, Perales-Puchalt J, Pluim C, Ramirez-Gomez L, Rentz DM, Rivera-Fernández C, Rosselli M, Serrano CM, Suing-Ortega MJ, Slachevsky A, Soto-Añari M, Sperling RA, Torrente F, Thumala D, Vannini P, Vila-Castelar C, Yañez-Escalante T, Quiroz YT. The impact of COVID-19 on the well-being and cognition of older adults living in the United States and Latin America. EClinicalMedicine, Volume 35, 2021, 100848, ISSN 2589–5370, 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López-Castro T, Brandt L, Anthonipillai NJ, Espinosa A, Melara R. Experiences, impacts and mental health functioning during a COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown: Data from a diverse New York City sample of college students. PLoS One. 2021. Apr 7;16(4):e0249768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249768. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haydon KC, Salvatore JE. A prospective study of mental health, well-being, and substance use during the initial COVID-19 pandemic surge. Clinical Psychological Science, In press 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Mortality Overview. NVSS - Provisional Death Counts for COVID-19 - Executive Summary (cdc.gov). Accessed 2/7/2022.

- 23.Galasso V, Pons V, Profeta P, Becher M, Brouard S, Foucault M. Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020. Nov 3;117(44):27285–27291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012520117. Epub 2020 Oct 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonucci T, Akiyama H. (1996). Convoys of social relations: Family and friendships within a lifespan context. In Bliezner R & Bedford V (Eds.), Aging and the family: Theory and research (pp. 353–371). Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKnight-Eily LR, Okoro CA, Strine TW, Verlenden J, Hollis ND, Njai R, Mitchell EW, Board A, Puddy R, Thomas C. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Prevalence of Stress and Worry, Mental Health Conditions, and Increased Substance Use Among Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021. Feb 5;70(5):162–166. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldmann E, Hagen D, Khoury EE, Owens M, Misra S, Thrul J. An examination of racial and ethnic disparities in mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S. South. J Affect Disord. 2021. Dec 1;295:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.047. Epub 2021 Aug 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luster JE, Ratz D, Wei MY. Multimorbidity and Social Participation Is Moderated by Purpose in Life and Life Satisfaction. J Appl Gerontol. 2022. Feb;41(2):560–570. doi: 10.1177/07334648211027691. Epub 2021 Jul 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marquine MJ, Maldonado Y, Zlatar Z, Moore RC, Martin AS, Palmer BW, Jeste DV. Differences in life satisfaction among older community-dwelling Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(11):978–88. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.971706. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, Kontopantelis E, Webb R, Wessely S, McManus S, Abel KM. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020. Oct;7(10):883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. Epub 2020 Jul 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glenn KR, Slaughter JC, Fowke JH, Buchowski MS, Matthews CE, Signorello LB, Blot WJ, Lipworth L. Physical activity, sedentary behavior and all-cause mortality among blacks and whites with diabetes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015. Sep;25(9):649–55. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.04.006. Epub 2015 Jun 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. Projections & Implications for Housing a Growing Population: Older Households 2015-2035. Page 54. 2016. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/harvard_jchs_housing_growing_population_2016.pdf. Accessed 2/7/2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.