Abstract

Background

Despite profound financial challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a gap in estimating their effects on mental health and well-being among older adults.

Methods

The National Health and Aging Trends Study is an ongoing nationally representative cohort study of U.S. older adults. Outcomes included mental health related to COVID-19 (scores averaged across eight items ranged from one to four), sleep quality during COVID-19, loneliness during COVID-19, having time to yourself during COVID-19 and hopefulness during COVID-19. Exposures included income decline during COVID-19 and financial difficulty due to COVID-19. Propensity score weighting produced covariate balance for demographic, socioeconomic, household, health, and well-being characteristics that preceded the pandemic to estimate the average treatment effect. Sampling weights accounted for study design and non-response.

Results

In weighted and adjusted analyses (n=3,257), both income decline during COVID-19 and financial difficulty due to COVID-19 were associated with poorer mental health related to COVID-19 (b= −0.1592, p<0.001and b= −0.3811, p <0.001, respectively), poorer quality sleep (OR= 0.63, 95% CI: 0.46, 0.86 and OR= 0.42, 95% CI: 0.30, 0.58, respectively), more loneliness (OR= 1.53, 95% CI: 1.16, 2.02 and OR= 2.72, 95% CI: 1.96, 3.77, respectively), and less time to yourself (OR= 0.54, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.72 and OR= 0.37, 95% CI: 0.27, 0.51, respectively) during COVID-19.

Conclusions

Pandemic-related financial challenges are associated with worse mental health and well-being regardless of pre-pandemic characteristics, suggesting that they are distinct social determinants of health for older adults. Timely intervention is needed to support older adults experiencing pandemic-related financial challenges.

Keywords: socioeconomic factors, financial strain, older adults, pandemic, mental health, well-being

Introduction

Older adults in the U.S. face unprecedented financial challenges during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Unemployment rose from 3.5% in February 2020 to 14.8% in April, which was the highest rate on record.1 This was followed by several months of inflation.2 Employed older adults were likely more sensitive to pandemic-related financial challenges than younger coworkers3 because they may have (1) quit or reduced work due to their risk of severe illness,4 and (2) been less successful in getting a new job. Many retired older adults have less financial flexibility to handle unexpected expenses than younger adults because they rely on fixed income sources; more than half rely on Social Security for more than half of their income.5 Although there is strong evidence linking pre-pandemic financial challenges with a higher risk of disability, dementia and earlier mortality among older adults,6–8 there has been little attention paid to pandemic-related financial challenges. There are gaps in understanding the prevalence of financial challenges among older adults, the strategies they are using to address the challenges, and the effect of those challenges on their health and well-being.

Limited evidence suggests that pandemic-related financial challenges are associated with poorer health outcomes during the pandemic. Cross-sectional studies found that older adults experiencing financial difficulty due to the pandemic9 and job loss10 reported more loneliness and poorer mental health during the pandemic. Among adults of all ages, experiencing any pandemic-related financial challenge was associated with greater depressive symptoms,11, 12 and in an all-female sample those who experienced income decline or financial difficulty due to the pandemic had less sleep and exercise, and more drinking and smoking.13 However, prior studies were limited in recruiting predominately online during the pandemic and only one had a national sampling frame.11 Nationally representative results are important because individuals who are Black, Hispanic or Native American have been disproportionately affected by COVID-1914 and likely also disproportionately experienced financial challenges due to persistent structural discrimination.15 Also, cohort data is needed to evaluate whether pandemic-related financial challenges are distinct from financial challenges typically encountered before the pandemic. A better understanding of the epidemiology and outcomes associated with pandemic-related financial challenges is urgently needed to advance health equity as we navigate the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to empirical evidence, the theory of fundamental causes provides theoretical justification for examining pandemic-related financial challenges by suggesting that socioeconomic factors influence multiple health outcomes through multiple intervening and replicating pathways.16 Since individuals with lower income and assets before the pandemic were more likely to additionally experience new financial challenges during the pandemic, the profound financial changes occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic may represent a new pathway contributing to socioeconomic health disparities. Therefore, there is a need to examine pandemic-related financial challenges to advance health equity. This study leveraged cohort data collected before and during the pandemic from a nationally representative sample of U.S. older adults to test two hypotheses. First, this study tests the hypothesis that experiencing a pandemic-related financial challenge is associated with poorer mental health and well-being. Second, this study examined potential dose-based associations by testing the hypothesis that needing more strategies to manage financial difficulty due to COVID-19 is associated with worse outcomes among those experiencing financial difficulty.

Methods

Study design and sample

The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) recruited a cohort of U.S. Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 years using stratified random sampling in 2011 and replenished the sample in 2015.17 NHATS study design18 and sample are19 described in detail elsewhere. NHATS participants were interviewed at home annually by trained interviewers. All 3,961 participants from the 2020 interview were mailed a separate COVID-19 survey between June and October of 2020 and 3,257 (82.2%) provided a completed survey by January 2021. The COVID-19 survey was intended to capture experiences that were specific to life during the pandemic. Thus, the questions differed from those in the annual interview. NHATS was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB and participants provided informed consent. The local institutional review board determined these analyses were exempt from review.

Measurement

Outcomes

Mental health and well-being outcomes for this study that were measured as part of the COVID-19 survey included mental health related to COVID-19, sleep quality, loneliness, having time to yourself and hopefulness, which each predict a higher risk of disability and earlier mortality among older adults.20–27 Mental health related to COVID-19 was based on not feeling worried/anxious or sad/depressed about the COVID-19 outbreak, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including not having recurring thoughts or nightmares about the outbreak, not avoiding activities or thoughts/feelings about the outbreak, and not feeling jumpy/easily startled or feeling on guard during the outbreak (Cronbach α=0.85, a measure of internal reliability).28 Responses were averaged across eight items which had four-point Likert scales, resulting in scores ranging from one to four. Sleep quality during the COVID-19 outbreak was rated as poor (reference), fair or good. The frequency of feeling lonely during the outbreak, feeling like they could get time to themselves during the outbreak, and hopeful during the COVID-19 outbreak were classified as rarely or never (reference), some days, most days and every day. Outcomes had low to moderate correlation (pairwise Spearman correlations ranged from 0.07 to 0.41), indicating that outcomes are related, but distinct.

Key Predictors

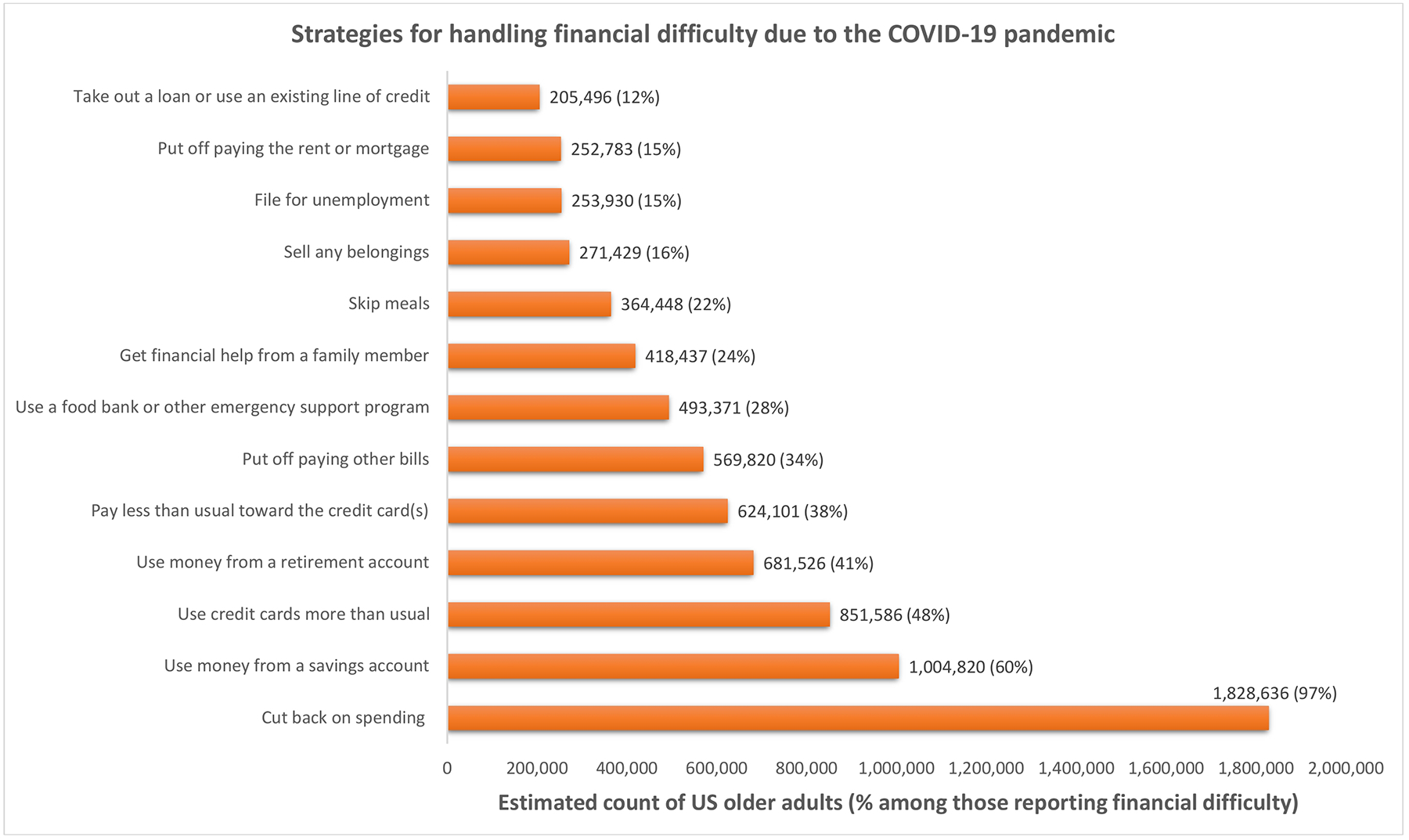

Pandemic-related financial challenge measures from the COVID-19 survey included income decline during COVID-19 and financial difficulty due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants reported if their monthly income increased/stayed the same or declined “compared to a typical month before the COVID-19 outbreak started,” and whether their household had “any financial difficulty because of the COVID-19 outbreak” (yes/no). A third variable generated among those reporting financial difficulty due to COVID-19 was a count of up to 13 strategies that were needed to manage financial difficulty, which are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Strategies used to handle financial difficulty due to the COVID-19 pandemic by National Health and Aging Trends Study participants who reported experiencing financial difficulty due to the pandemic (n=175). Sampling weights were applied so that inferences can be drawn to the 2020 population of U.S. adults aged 70 and older. Values represent U.S. population counts and percentages.

Demographic/health Covariates

Other potentially confounding variables measured prior to COVID-19 during one of the annual NHATS interviews between 2015 and 2019 included demographic, socioeconomic, household and health characteristics. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, and race/ethnicity (White (reference), Black, other race, and Hispanic). Socioeconomic characteristics included education (< high school, high school, some college, and ≥ Bachelor’s degree), homeownership (rent (reference), own with mortgage, own without payments), retirement status (no/yes), professional occupation (based on longest occupation held using the U.S. Census classification), income to poverty ratio (ratio of 2019 household income to the relevant U.S. Census Bureau poverty threshold for individuals aged ≥65 years based on household size) and financial strain. Financial strain scores were a count of up to four items for which participants lacked enough money, including rent/mortgage, utility bills, medical/prescription bills or food. Household characteristics included household size and marital status (married/partnered (reference), separated/divorced, widowed, never married). Although the outcomes measured in the COVID-19 survey were not also measured in the annual NHATS interview, these analyses accounted for multiple health and well-being characteristics measured in 2019 before the pandemic. Health characteristics included body mass index (BMI) based on self-reported height and weight, self-rated health (poor (reference), fair, good, very good and excellent), three-meter usual walking speed test based on the average of two walking test trials, and chronic conditions, which was a count of the following prior diagnoses: arthritis, heart disease or heart attack, cancer that was not skin cancer, diabetes, lung disease, dementia or Alzheimer’s, a stroke, a fractured hip or other serious illness. Mental health and well-being characteristics measured before the pandemic included presence of depressive symptoms (PHQ-2 score ≥3),29 presence of anxiety symptoms (GAD-2 score≥3),30 social isolation,31 and sleep quality, based on frequency of needing >30 minutes to fall asleep and trouble falling back asleep.

Analyses

Two data management steps were taken prior to testing hypotheses. First, multiple imputation with chained equations was employed with ten replications to address missing data whenever imputation was supported by the data. Imputation used available information from all potentially confounding variables, including 2017, 2018 and 2019 values for demographic, socioeconomic, household and health characteristics. Second, this study used propensity score weighted models to estimate average treatment effects32 separately for income decline during COVID-19 and financial difficulty due to COVID-19. Propensity score methods are used to improve balance comparing the exposed and unexposed groups in observational studies so that the average treatment effect can be estimated by comparing two that are conditionally similar with regard to measured background characteristics.33 Propensity scores were estimated using the covariate balancing propensity score method, which allows optimization of the covariate balance simultaneously with the specification of the propensity score model.34 Propensity score models used all potentially confounding variables listed above to estimate the probability of either income decline during COVID-19 or financial difficulty due to COVID-19. Covariate balance across groups was considered to have been achieved if the standardized mean difference comparing those with and without the respective financial challenge was <0.1.33 Propensity scores were used to calculate inverse probability of treatment weights.

After these steps were completed, hypothesized associations were tested with ordered logistic regressions except that linear regression was used for mental health related to COVID-19. Income decline during COVID-19 and financial difficulty due to COVID-19 were examined in separate propensity score-weighted models. Additional models tested hypothesized associations between the number of strategies needed to manage financial difficulty with outcomes among those who reported experiencing financial difficulty due to COVID-19. All models adjusted for participant characteristics measured prior to the pandemic, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, occupation, and 2019 values for income to poverty ratio, financial strain, homeownership, retirement status, household size, marital status, BMI, chronic conditions, self-rated health, presence of depressive or anxiety symptoms, sleep quality and social isolation. Therefore, models estimating the effects of income decline during COVID-19 and financial difficulty due to COVID-19 produced doubly robust effect estimates by accounting for all individual characteristics in both the propensity score model and the outcome model. All models applied sampling weights to account for study design and non-response so that inferences could be drawn to the U.S. population of adults aged 70 and older in 2020. Since the effect of pandemic-related financial challenges may differ based on individual characteristics before the pandemic,15 interactions between 2019 financial strain, Black race, Hispanic ethnicity and gender were tested with income decline and financial difficulty for each outcome. Since the mental health related to COVID-19 measure has not been used in prior studies, a sensitivity analyses separately examined feelings of anxiety, depression and PTSD.

Results

Approximately 8% (population estimate 2,639,962) of U.S. older adults reported income decline during COVID-19 (Table 1), 6% (2,011,471) reported financial difficulty due to COVID-19 (Table 2) and 3% experienced both financial challenges. Income decline and financial difficulty were both more common among those who were Black (9% and 14%, respectively) rather than White (8% and 5%, respectively), and among those with more financial strain (mean financial strain scores were 0.19 vs. 0.06 among those with and without income decline, respectively and were 0.48 vs. 0.05 among those with and without financial difficulty, respectively) (Tables 1 & 2). However, income decline was most common among those with at least a bachelor’s level of education (12%) and those with excellent health (11%) (Table 1) whereas financial difficulty was most common among those with less than a high school level of education (9%), or poor health (13%) (Table 2). Total sample characteristics are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected sample characteristics from 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic based on income decline during the COVID-19 pandemic among National Health and Aging Trends Study participants (n=3,257)

| Income decline during COVID-19 | Standardized mean difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Un-weighted | Propensity score weighted | |

| Overall sample (%) | 2,972 (92) | 214 (8) | 0.07 | |

| Financial difficulty due to COVID-19 (%) | N/A | N/A | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,728 (96) | 135 (4) | ||

| Yes | 105 (67) | 68 (33) | ||

| Age (%) | −0.38 | 0.003 | ||

| 65–74 (ref.) | 645 (89) | 79 (11) | ||

| 75–79 | 819 (91) | 73 (9) | ||

| 80–84 | 681 (95) | 37 (5) | ||

| ≥85 | 827 (97) | 25 (3) | ||

| Gender (%) | 0.03 | −0.0008 | ||

| Male (ref.) | 1,246 (92) | 95 (8) | ||

| Female | 1,726 (92) | 119 (8) | ||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White (ref.) | 2,267 (92) | 157 (8) | 0.05 | −0.006 |

| Black | 487 (91) | 40 (9) | 0.02 | 0.008 |

| Other | 58 (91) | 6 (9) | 0.02 | −0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 122 (95) | 8 (5) | −0.16 | −0.0004 |

| Mean income to poverty ratio mean (SE) | 4.14 (0.15) | 5.38 (0.49) | 0.24 | −0.001 |

| Mean income, in U.S. $ (SE) | 63,262 (2,307) | 83,005 (7,496) | N/A | N/A |

| Educational achievement (%) | 0.52 | −0.007 | ||

| <High school (ref.) | 448 (98) | 10 (2) | ||

| High school | 767 (95) | 37 (5) | ||

| Some college | 810 (91) | 69 (9) | ||

| Bachelors or higher | 912 (88) | 95 (12) | ||

| Mean financial strain (SE) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.06) | 0.27 | 0.001 |

| Homeownership (%) | −0.17 | 0.005 | ||

| Rent (ref.) | 792 (93) | 53 (7) | ||

| Own with mortgage | 583 (86) | 79 (14) | ||

| Own without payments | 1,566 (95) | 77 (5) | ||

| Retirement status (%) | −0.20 | −0.0002 | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,443 (91) | 195 (9) | ||

| Yes | 323 (96) | 13 (4) | ||

| Professional occupation (%) | 0.29 | −0.003 | ||

| No (ref.) | 1,812 (94) | 97 (6) | ||

| Yes | 1,148 (89) | 117 (11) | ||

| Mean household size (SE) | 1.97 (0.03) | 2.01 (0.08) | 0.05 | 0.003 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Married/partnered (ref.) | 1,448 (91) | 116 (9) | 0.06 | −0.001 |

| Separated/divorced | 402 (91) | 32 (9) | 0.03 | −0.0009 |

| Widowed | 1,024 (93) | 58 (7) | −0.13 | 0.004 |

| Never married | 96 (88) | 8 (12) | 0.09 | −0.003 |

| Mean BMI, in kg/m2 (SE) | 28.21 (0.14) | 28.68 (0.64) | 0.09 | 0.0004 |

| Mean chronic conditions (SE) | 1.57 (0.03) | 1.37 (0.08) | −0.17 | −0.001 |

| Self-rated health (%) | 0.29 | −0.005 | ||

| Poor (ref.) | 98 (93) | 7 (7) | ||

| Fair | 546 (97) | 18 (4) | ||

| Good | 1,080 (92) | 81 (8) | ||

| Very good | 954 (90) | 75 (10) | ||

| Excellent | 290 (89) | 33 (11) | ||

| Depressive symptomsa (%) | −0.07 | −0.0007 | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,688 (92) | 193 (8) | ||

| Yes | 284 (94) | 21 (6) | ||

| Anxiety symptomsb (%) | −0.04 | 0.002 | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,727 (92) | 195 (8) | ||

| Yes | 225 (93) | 18 (7) | ||

| Mean walking speed, in m/s (SE) | 0.75 (0.01) | 0.84 (0.02) | 0.29 | −0.002 |

| Mean sleep quality score (SE) | 7.24 (0.05) | 7.49 (0.20) | 0.14 | 0.0007 |

| Isolation (%) | ||||

| Not isolated (ref.) | 96 (94) | 4 (6) | −0.07 | 0.0005 |

| Socially isolated | 432 (96) | 18 (4) | −0.27 | 0.009 |

| Severely socially isolated | 2,335 (91) | 188 (9) | 0.28 | −0.008 |

Note: Descriptive statistics calculated before multiple imputation, applying sampling weights so that inferences can be drawn to 2020 population of US adults aged 70 and older. Standardized mean differences were calculated after multiple imputation.

Based on PHQ-2 score ≥3

Based on GAD-2 score≥3

Table 2.

Selected sample characteristics from 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic based on financial difficulty due to COVID-19 among National Health and Aging Trends Study participants (n=3257)

| Financial difficulty due to COVID-19 | Standardized mean difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Un-weighted | Propensity score weighted | |

| Overall sample (%) | 2,933 (94) | 181 (6) | 0.05 | |

| Income decline during COVID-19 (%) | N/A | N/A | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,783 (94) | 109 (6) | ||

| Yes | 138 (57) | 70 (43) | ||

| Age (%) | −0.32 | 0.01 | ||

| 65–74 (ref.) | 658 (92) | 55 (8) | ||

| 75–79 | 821 (93) | 57 (7) | ||

| 80–84 | 657 (95) | 41 (5) | ||

| ≥85 | 797 (97) | 28 (3) | ||

| Gender (%) | 0.13 | −0.004 | ||

| Male (ref.) | 1,258 (95) | 64 (5) | ||

| Female | 1,675 (93) | 117 (7) | ||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White (ref.) | 2,288 (95) | 98 (5) | −0.37 | −0.004 |

| Black | 441 (86) | 64 (14) | 0.21 | 0.009 |

| Other | 57 (93) | 5 (7) | −0.02 | −0.002 |

| Hispanic | 106 86) | 13 (14) | 0.36 | −0.003 |

| Mean income to poverty ratio mean (SE) | 4.40 (0.17) | 2.83 (0.30) | −0.45 | −0.004 |

| Mean income, in U.S. $ (SE) | 67,193 (2669) | 44,617 (4,587) | N/A | N/A |

| Educational achievement (%) | −0.16 | −0.003 | ||

| <High school (ref.) | 394 (91) | 34 (9) | ||

| High school | 744 (95) | 42 (5) | ||

| Some college | 805 (92) | 60 (8) | ||

| Bachelors or higher | 953 (95) | 43 (5) | ||

| Mean financial strain (SE) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.48 (0.10) | 0.63 | 0.003 |

| Homeownership (%) | −0.26 | −0.0009 | ||

| Rent (ref.) | 744 (92) | 67 (8) | ||

| Own with mortgage | 594 (90) | 51 (10) | ||

| Own without payments | 1,561 (96) | 61 (4) | ||

| Retirement status (%) | −0.10 | −0.003 | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,423 (93) | 161 (7) | ||

| Yes | 307 (95) | 18 (5) | ||

| Professional occupation (%) | −0.05 | −0.005 | ||

| No (ref.) | 1,739 (93) | 118 (7) | ||

| Yes | 1,184 (94) | 62 (6) | ||

| Mean household size (SE) | 1.94 (0.02) | 2.25 (0.18) | 0.26 | 0.0004 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Married/partnered (ref.) | 1,473 (95) | 74 (5) | −0.14 | −0.002 |

| Separated/divorced | 374 (90) | 45 (10) | 0.20 | −0.004 |

| Widowed | 987 (94) | 55 (6) | −0.05 | 0.007 |

| Never married | 97 (90) | 7 (10) | 0.10 | −0.001 |

| Mean BMI, in kg/m2 (SE) | 28.07 (0.14) | 30.48 (0.76) | 0.38 | −0.002 |

| Mean chronic conditions (SE) | 1.53 (0.02) | 1.74 (0.11) | 0.17 | −0.004 |

| Self-rated health (%) | −0.20 | 0.0002 | ||

| Poor (ref.) | 82 (87) | 12 (13) | ||

| Fair | 495 (91) | 45 (9) | ||

| Good | 1,083 (95) | 59 (5) | ||

| Very good | 963 (94) | 50 (6) | ||

| Excellent | 306 (94) | 15 (6) | ||

| Depressive symptomsa (%) | 0.11 | −0.003 | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,664 (94) | 157 (6) | ||

| Yes | 269 (92) | 24 (8) | ||

| Anxiety symptomsb (%) | 0.26 | 0.003 | ||

| No (ref.) | 2,703 (94) | 155 (6) | ||

| Yes | 209 (88) | 26 (12) | ||

| Mean walking speed, in m/s (SE) | 0.76 (0.01) | 0.73 (0.02) | −0.14 | −0.0006 |

| Mean sleep quality score (SE) | 7.27 (0.06) | 7.19 (0.23) | −0.05 | 0.003 |

| Isolation (%) | ||||

| Not isolated (ref.) | 94 (93) | 6 (7) | 0.03 | −0.002 |

| Socially isolated | 414 (92) | 27 (8) | 0.10 | 0.009 |

| Severely socially isolated | 2,318 (94) | 144 (6) | −0.10 | −0.008 |

Note: Descriptive statistics calculated before multiple imputation, applying sampling weights so that inferences can be drawn to 2020 population of US adults aged 70 and older. Standardized mean differences were calculated after multiple imputation.

Based on PHQ-2 score ≥3

Based on GAD-2 score≥3

Among older adults who reported financial difficulty due to COVID-19, many reported using multiple strategies to handle the difficulty (Figure 1). Almost all reported cutting back on spending (97%) and many also reported using savings (60%) or credit cards (48%) to handle the difficulty (Figure 1). Some individuals also compromised basic necessities; 15% put off paying the rent or mortgage and 22% skipped meals.

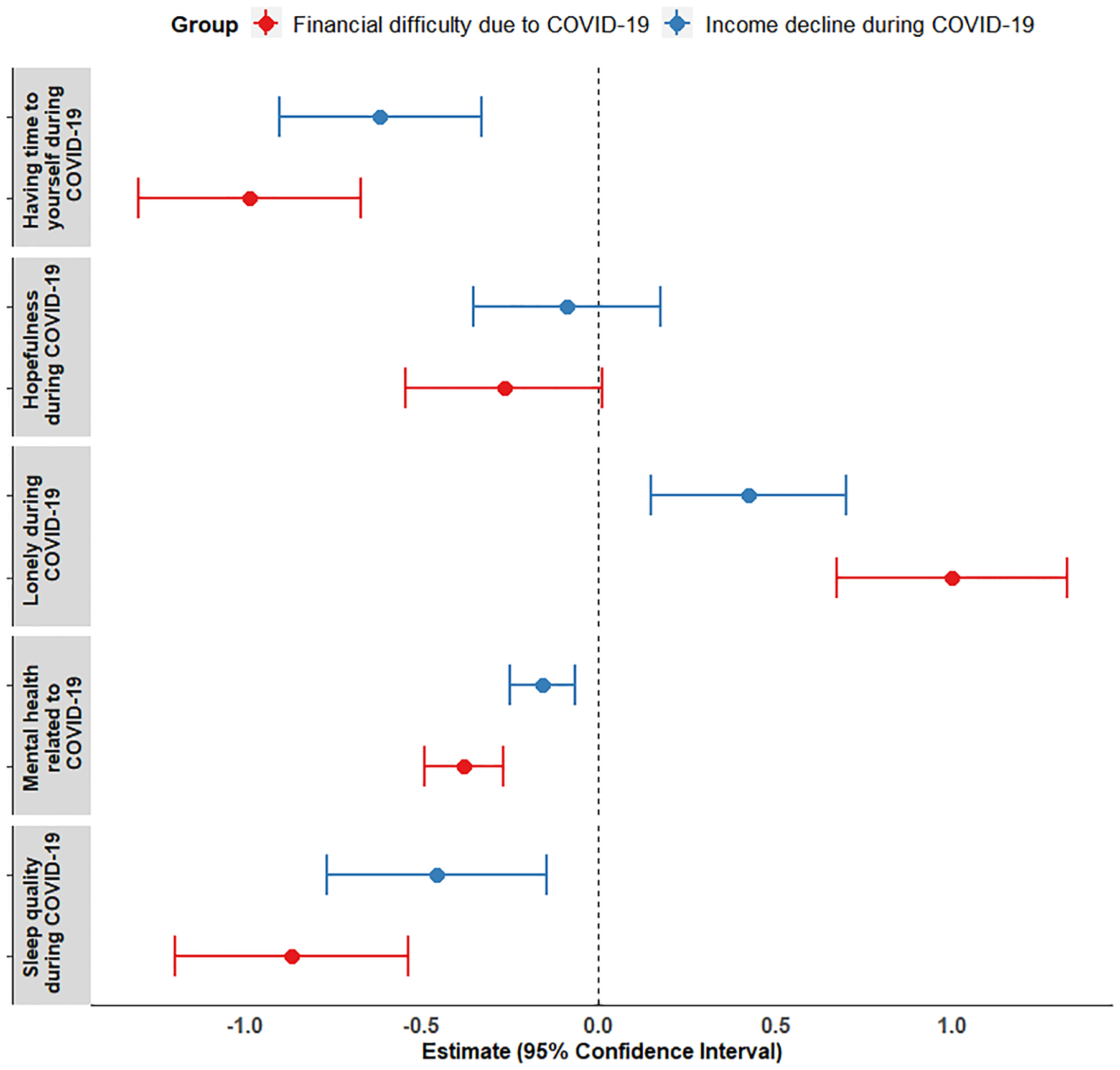

In propensity score weighted and adjusted models (Table 3 and Figure 2), older adults whose income declined during COVID-19 had poorer mental health related to COVID-19 (b= −0.1592, p<0.001), had poorer sleep quality (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.46, 0.86), were more lonely (OR= 1.53, 95% CI: 1.16, 2.02) and had less time to themselves (OR= 0.54, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.72) during COVID-19 than their peers without income decline. Compared to older adults without financial difficulty due to COVID-19, older adults who experienced financial difficulty had worse mental health related to COVID-19 (b= −0.3811, p <0.001), had poorer sleep quality (OR= 0.42, 95% CI: 0.30, 0.58), were more lonely (OR= 2.72, 95% CI: 1.96, 3.77), and had less time to themselves (OR= 0.37, 95% CI: 0.27, 0.51) during COVID-19. Neither income decline during COVID-19 nor financial difficulty due to COVID-19 were associated with hopefulness. In adjusted analyses among older adults who experienced financial difficulty due to COVID-19, those who needed more strategies to manage the difficulty had poorer sleep quality (OR=0.59, 95% CI: 0.37, 0.93) during COVID-19, but did not differ with regard to mental health related to COVID-19, loneliness, time to themselves or hopefulness during COVID-19. As depicted in Figure 2, coefficients for associations differed across mental health and well-being outcomes and they were relatively larger, but not statistically significantly different, for financial difficulty due to COVID-19 than for income decline. None of the interaction terms described in the analyses section were statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses found that inferences were unchanged when questions about anxiety, depression and PTSD are analyzed separately (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Associations between income decline during COVID-19, financial difficulty due to COVID-19, and among those with financial difficulty, the number of strategies needed to manage it, with mental health and well-being outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic among National Health and Aging Trends Study participants

| Income decline during COVID-19a | n | Financial difficulty due to COVID-19a | n | Number of strategies needed to manage financial difficulty due to COVID-19b | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health related to COVID-19c Coefficient (SE), p value | −0.159 (0.046), <0.001 | 3029 | −0.381 (0.057), <0.001 | 3025 | −0.070 (0.102), 0.49 | 175 |

| Sleep quality during COVID-19 OR (95% CI) | 0.63 (0.46, 0.86) | 3026 | 0.42 (0.30, 0.58) | 3023 | 0.59 (0.37, 0.93) | 175 |

| Lonely during COVID-19 OR (95% CI) | 1.53 (1.16, 2.02) | 3025 | 2.72 (1.96, 3.77) | 3021 | 1.50 (0.92, 2.45) | 175 |

| Having time to yourself during COVID-19 OR (95% CI) | 0.54 (0.40, 0.72) | 3024 | 0.37 (0.27, 0.51) | 3021 | 0.54 (0.26, 1.14) | 175 |

| Hopefulness during COVID-19 OR (95% CI) | 0.91 (0.70, 1.19) | 3021 | 0.76 (0.58, 1.01) | 3017 | 1.49 (0.73, 3.07) | 175 |

Note: Sampling weights were applied to all analyses so that inferences can be drawn to 2020 population of US adults aged 70 and older. Mental health related to COVID-19 was based on not feeling worried/anxious or sad/depressed about the COVID-19 outbreak, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including not having recurring thoughts or nightmares about the outbreak, not avoiding activities or thoughts/feelings about the outbreak, and not feeling jumpy/easily startled or feeling on guard during the outbreak (Cronbach α=0.85, a measure of internal reliability).28 Responses were averaged across eight items which had four-point Likert scales, resulting in scores ranging from one to four. Sleep quality during the COVID-19 outbreak was rated as poor (reference), fair or good. The frequency of feeling lonely during the outbreak, feeling like they could get time to themselves during the outbreak, and hopeful during the COVID-19 outbreak were classified as rarely or never (reference), some days, most days and every day. Logistic regression was used for all outcomes except that mental health related to COVID-19 was examined using linear regression. All models adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and 2019 values for income to poverty ratio, financial strain, retirement status, BMI, chronic conditions, self-rated health, presence of depressive symptoms, presence of anxiety symptoms, walking speed, sleep quality and social isolation. Bold font indicates statistically significant results at p<0.05.

Additionally applied propensity score weights to produce doubly robust estimates of the average treatment effect. In addition to the variables listed above for the adjusted models, the propensity score model included education, professional occupation, homeownership, household size and marital status.

Among the 175 NHATS participants who experienced financial difficulty due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were asked whether they used each of 13 different strategies to manage the difficulty.

Scores ranged from one to four based on responses to eight items.

Figure 2.

Adjusted coefficient estimates with 95% confidence intervals of the associations between income decline during COVID-19 and financial difficulty due to COVID-19 with mental health and well-being outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic among National Health and Aging Trends Study participants. Results are also presented in Table 3, except that unexponentiated coefficient values from logistic regression are presented here so that relative comparison can be made across both outcomes and exposures.

Discussion

This study estimates that 2.6 million older adults experienced an income decline during COVID-19 and 2 million experienced a financial difficulty due to COVID-19. Importantly, both groups had worse mental health related to COVID-19, more loneliness, poorer sleep quality, and were less likely to have time to themselves during the pandemic than their peers without those respective financial challenges. These results shed light on at least two health equity issues related to financial difficulty due to COVID-19. First, individuals in this study who experienced financial difficulty due to COVID-19 were disproportionately individuals who are low-income and either Black or Hispanic, suggesting that financial difficulty due to COVID-19 may exacerbate longstanding disparities based on income, race and/or ethnicity. When interpreted based on fundamental cause theory,16 these results suggest that financial difficulty due to COVID-19 may represent a novel pathway linking socioeconomic disadvantage and racial/ethnic discrimination to disparities in mental health and well-being. Combined with evidence reviewed earlier of racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 incidence and mortality,14 these results suggest that individuals who are Black or Hispanic are doubly disadvantaged with both a greater disease burden and more pandemic-related financial challenges. Second, although many of the strategies reported by older adults in this study may help them handle their current financial difficulty, they may have adverse long-term consequences. As examples, 22% of older adults who had financial difficulty due to COVID-19 reported skipping meals. The rate of food insecurity among older adults increased by 38% to affect an estimated 5.3 million older adults over the two decades prior to the pandemic35 and these results suggest that financial difficulty due to COVID-19 likely exacerbated this growing public health problem. This finding is important because food insecurity is linked with numerous negative health outcomes, including more limitations in activities of daily living,36 poorer self-rated health,37, 38 higher risk of having multiple chronic conditions,38 nutritional risk37 and greater hospital utilization39 among older adults. As another example, many older adults who faced financial difficulty due to COVID-19 were forced to use retirement savings and increase their credit card debt. Both strategies will increase their ratio of debt to financial assets, which is associated with more depressive symptoms and poorer health.40

These results build on those of prior studies examining pandemic-related financial challenges reviewed earlier9, 11, 13 and contribute to the literature in three key ways. First, this study describes the prevalence of financial challenges and the characteristics of individuals who experience them among a nationally representative sample of U.S. older adults to better understand these exposures at a population level. Second, these results are consistent with prior studies showing associations between pandemic-related financial challenges with mental health and loneliness and build on those studies by additionally finding associations with sleep quality and time to yourself. Finally, these results are likely more accurate estimates of the association between financial challenges and mental health and well-being than those of prior studies because of the cohort study design and propensity score approach. The use of propensity score weighting allowed this study to better distinguish between the effects of pandemic-related financial challenges from the effects of pre-pandemic exposures than was done in prior studies. Therefore, these results contribute to the literature by demonstrating that financial challenges predict mental health and well-being for older adults regardless of the individual’s pre-pandemic demographic, socioeconomic, household, health and well-being characteristics.

These results have implications for clinical practice, research and policy. As reviewed earlier, the outcomes in this study are associated with a higher risk of disability and early mortality,20–27 suggesting that timely interventions are needed for older adults reporting financial difficulty due to the COVID-19 pandemic and/or income decline during COVID-19. These results suggest that older adults should be screened for pandemic-related financial challenges. Although both types of challenges (income decline and financial difficulty due to COVID-19) were associated with poorer mental health and well-being in this study, it likely is more important to screen for financial difficulty rather than income decline for two reasons. First, associations with income, race and ethnicity in this study suggest that addressing financial difficulty due to COVID-19 may advance health equity. Second, evidence from prior studies examining chronic financial strain among older adults found it was associated with a higher risk of physical disability, dementia, frailty, and earlier mortality regardless of income level,6–8, 41, 42 suggesting that self-report of financial challenges is important for health outcomes. Interventions addressing pandemic-related financial challenges should build on strategies that are already employed by older adults experiencing financial difficulties. As examples, these results show that the vast majority of older adults experiencing financial difficulties have already cut back on expenses and used financial resources available to them. Urgent intervention is needed to support older adults in meeting basic needs, such as providing for food security, rent and monthly bills. Economic supports that were implemented during the pandemic, such as stimulus checks, expanded access to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and eviction moratoriums, may need to be extended over longer periods of time to help low-income households who are experiencing financial challenges during the pandemic. Such intervention may prevent costly and burdensome disability and mortality. This study also found that individuals who reported financial strain before the pandemic were more likely to experience pandemic-related financial challenges, suggesting that interventions to address financial strain across the life course may prevent harm from future unanticipated financial challenges.

Strengths and limitations

This study was limited by measuring several outcomes using single questions and did not measure changes in outcomes over time. This study did not measure total household wealth, although the study did measure both homeownership, which is the main source of wealth for U.S. households,43 and financial strain, which captures adequacy of income in relation to cost of living. This study is also not able to assess whether or how financial challenges have progressed during 2021 after vaccinations were available in the U.S. and economic supports such as unemployment benefits or eviction moratoriums were scaled back. However, the study was strengthened by including a nationally representative sample of U.S. older adults and the measurement of a large set of demographic, socioeconomic and health characteristics prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This study found that experiencing either a financial difficulty due to the COVID-19 pandemic or income decline during COVID-19 are associated with worse outcomes, including worse mental health related to COVID-19, poorer sleep quality, more loneliness, and less time to yourself. These results suggest that pandemic-related financial challenges are distinct from other established social determinants of mental health and well-being among older adults. Urgent action is needed to address pandemic-related financial challenges for older adults to improve health outcomes and advance health equity.

Supplementary Material

Key points

Pandemic-related financial challenges contribute to poorer mental health and well-being for U.S. older adults regardless of their financial situation before the pandemic.

Older adults facing financial difficulty due to COVID-19 typically used multiple strategies to handle the challenge and some compromised basic necessities such as skipping meals or putting of paying the rent/mortgage.

Older adults who were either Black or Hispanic, and those who were financially strained before the pandemic disproportionately experienced financial difficulty due to COVID-19, suggesting that it may exacerbate long-standing health disparities.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

Clinical screening for financial difficulty due to COVID-19 and income decline during COVID-19 with timely referral for social services may attenuate the harmful effects of financial challenges for older adults.

Acknowledgements

The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG032947) through a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging.

Sponsor’s Role:

Although the study sponsor provided guidance on study design, they were not involved in data collection, analyses, the preparation of this manuscript or the decision to submit this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Falk G, Romero PD, Carter JA, Nicchitta IA, Nyhof EC. Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R46554.pdf

- 2.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index - June 2021. 2021.

- 3.Li Y, Mutchler JE. Older Adults and the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. Jul 3 2020;32(4–5):477–487. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1773191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. Mar 23 2020;doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dushi I, Iams HM, Trenkamp B. The Importance of Social Security Benefits to the Income of the Aged Population. Vol. 77. 2017. Social Security Bulletin. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker-Seeley RD, Li Y, Subramanian SV, Sorensen G. Financial hardship and mortality among older adults using the 1996–2004 Health and Retirement Study. Ann Epidemiol. Dec 2009;19(12):850–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Ornstein KA, Parker LJ, Gitlin LN. Socioeconomic disparities in six-year incident dementia in a nationally representative cohort of U.S. older adults: an examination of financial resources. BMC Geriatr. May 6 2020;20(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01553-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Whitfield K. Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Soc Sci Med. Jul 2010;71(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polenick CA, Perbix EA, Salwi SM, Maust DT, Birditt KS, Brooks JM. Loneliness During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Older Adults With Chronic Conditions. Journal of Applied Gerontology. Feb 28 2021;doi:Artn 0733464821996527 10.1177/0733464821996527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrams LR, Finlay JM, Kobayashi LC. Job transitions and mental health outcomes among US adults aged 55 and older during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Apr 10 2021;doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Low assets and financial stressors associated with higher depression during COVID-19 in a nationally representative sample of US adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. Dec 4 2020;doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng JS, Morstead T, Sin N, et al. Psychological distress in North America during COVID-19: The role of pandemic-related stressors. Social Science & Medicine. Feb 2021;270doi:ARTN 113687 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson L, Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, et al. Financial hardship and health risk behavior during COVID-19 in a large US national sample of women. SSM Popul Health. Mar 2021;13:100734. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Apr 17 2020;69(15):458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. Sep–Oct 2001;116(5):404–416. doi:Doi 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51 Suppl:S28–40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeMatteis J, Freedman VA, Kasper JD. National Health and Aging Trends Study Round 5 Sample Design and Selection. 2016. www.NHATS.org

- 18.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study User Guide: Rounds 1–6 Final Release. 2017. www.NHATS.org

- 19.Freedman VA, Kasper JD. Cohort Profile: The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). International Journal of Epidemiology. Aug 2019;48(4):1044–+. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiovitz-Ezra S, Ayalon L. Situational versus chronic loneliness as risk factors for all-cause mortality. International Psychogeriatrics. May 2010;22(3):455–462. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG, Martire LM, Ariyo AA, Kop WJ. Association between depression and mortality in older adults - The Cardiovascular Health Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. Jun 26 2000;160(12):1761–1768. doi:DOI 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Song J, Lyons JS, Chang RW. Incidence of disability among preretirement adults: The impact of depression. American Journal of Public Health. Nov 2005;95(11):2003–2008. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2004.050948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman EM. Self-Reported Sleep Problems Prospectively Increase Risk of Disability: Findings from the Survey of Midlife Development in the United States. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Nov 2016;64(11):2235–2241. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Sleep and mortality: A population-based 22-year follow-up study. Sleep. Oct 1 2007;30(10):1245–1253. doi:DOI 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stern SL, Dhanda R, Hazuda HP. Hopelessness predicts mortality in older Mexican and European Americans. Psychosomatic Medicine. May–Jun 2001;63(3):344–351. doi:Doi 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long CR, Averill JR. Solitude: An exploration of benefits of being alone. J Theor Soc Behav. Mar 2003;33(1):21–+. doi:Doi 10.1111/1468-5914.00204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fancourt D, Aughterson H, Finn S, Walker E, Steptoe A. How leisure activities affect health: a narrative review and multi-level theoretical framework of mechanisms of action (vol 8, pg 329, 2021). Lancet Psychiat. Apr 2021;8(4):E12–E12. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00069-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika. Sep 1951;16(3):297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 Validity of a Two-Item Depression Screener. Medical Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine. Mar 6 2007;146(5):317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cudjoe TKM, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ. The Epidemiology of Social Isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Jan 1 2020;75(1):107–113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Statistics in Medicine. Dec 10 2015;34(28):3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. doi:Pii 938470000 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imai K, Ratkovic M. Covariate balancing propensity score. J R Stat Soc B. Jan 2014;76(1):243–263. doi: 10.1111/rssb.12027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziliak JP, Gundersen C. The State of Senior Hunger in America 2018: An Annual Report. 2020.

- 36.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food Insecurity And Health Outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood). Nov 2015;34(11):1830–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JS, Frongillo EA Jr. Nutritional and health consequences are associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons. J Nutr. May 2001;131(5):1503–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leung CW, Kullgren JT, Malani PN, et al. Food insecurity is associated with multiple chronic conditions and physical health status among older US adults. Prev Med Rep. Dec 2020;20:101211. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhargava V, Lee JS. Food Insecurity and Health Care Utilization Among Older Adults in the United States. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. Jul–Sep 2016;35(3):177–92. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2016.1200334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweet E, Nandi A, Adam EK, McDade TW. The high price of debt: Household financial debt and its impact on mental and physical health. Social Science & Medicine. Aug 2013;91:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szanton SL, Allen JK, Thorpe RJ Jr., Seeman T, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Effect of financial strain on mortality in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Nov 2008;63(6):S369–74. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.S369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szanton SL, Seplaki CL, Thorpe RJ Jr., Allen JK, Fried LP. Socioeconomic status is associated with frailty: the Women’s Health and Aging Studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. Jan 2010;64(1):63–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. The state of the nation’s housing 2021. 2021. Accessed 11/29/2021. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_State_Nations_Housing_2021.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.