Abstract

Background

Little is known about the effects of pesticides on children’s respiratory and allergic outcomes. We evaluated associations of prenatal and current pesticide exposures with respiratory and allergic outcomes in children from the Infants’ Environmental Health Study in Costa Rica.

Methods

Among 5-year-old children (n=303), we measured prenatal and current specific gravity-corrected urinary metabolite concentrations of insecticides (chlorpyrifos, pyrethroids), fungicides (mancozeb, pyrimethanil, thiabendazole) and 2,4-D. We collected information from caregivers on respiratory (ever doctor-diagnosed asthma and lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI), wheeze and cough during last 12 months) and allergic (nasal allergies, itchy rash, ever eczema) outcomes. We fitted separate multivariable logistic regression models for high (≥75th percentile (P75)) vs low (<P75) metabolite concentrations with respiratory and allergic outcomes. We also ran models including metabolite concentrations as continuous exposure variables.

Results

Children’s respiratory outcomes were common (39% cough, 20% wheeze, 12% asthma, 5% LRTI). High current pyrethroid metabolite concentrations (Σpyrethroids) were associated with wheeze (OR=2.37, 95% CI 1.28 to 4.34), itchy rash (OR=2.74, 95% CI 1.33 to 5.60), doctor-diagnosed asthma and LRTI. High current ethylene thiourea (ETU) (specific metabolite of mancozeb) was somewhat associated with LRTI (OR=2.09, 95% CI 0.68 to 6.02). We obtained similar results when modelling Σpyrethroids and ETU as continuous variables. We saw inconsistent or null associations for other pesticide exposures and health outcomes.

Conclusions

Current pyrethroid exposure may affect children’s respiratory and allergic health at 5 years of age. Current mancozeb exposure might contribute to LRTI. These findings are important as pyrethroids are broadly used in home environments and agriculture and mancozeb in agriculture.

INTRODUCTION

The possible effects of pesticides on children’s respiratory health are a public health concern. Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) are leading cause of death among children under 5 years of age, and asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood, affecting 14% of children globally.1 Asthma prevalence has been increased during last decades, particularly in low-resource settings.2 Respiratory outcomes, including infection and wheezing, during infancy can have long-term consequences for adult respiratory health.3 Only few studies have reported associations of pesticide exposure with adverse respiratory outcomes in young children.4 5 Worldwide, exposure to pesticides is common in both agricultural and residential settings, and results from epidemiological studies of farmworkers have shown that occupational pesticide exposure may affect respiratory health, as it has been associated with increased odds of coughing, wheezing and asthma.5–9

Pesticide exposure assessment in epidemiological studies is challenging, and researchers studying its effects on children’s respiratory health have opted for different approaches, including measurement of pesticides, or its metabolites, in personal air samples, blood and urine.10 The measurement of urinary pesticide metabolites is one of the most-used methods and often considered the gold standard of exposure assessment, because they reflect exposures from all routes, and, generally, concentrations are more easily detected in urine as compared with blood. Nevertheless, as most current-use pesticides have relatively short toxicokinetic half-lives, their urinary metabolites mainly reflect exposures during the last 24 hours and tend to vary substantially for the same person on different days, most likely attenuating exposure-effect associations of chronic health effects.

Several pesticides have been associated with respiratory outcomes in children. Results from a birth cohort in New York City indicated children aged 5–6 years with higher prenatal exposure to piperonyl butoxide (PBO), a synergist for residential pyrethroid insecticides, had more frequent non-infectious cough compared with children with lower exposures.11 On the other hand, the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) birth cohort showed children with higher prenatal urinary organophosphate (OP) insecticide concentrations in the second half of pregnancy, and higher cumulative OP exposure during childhood had more respiratory symptoms at ages 5 and 7 years.12 Results from the same cohort indicated cumulative urinary OP-metabolite concentrations between 0.5 and 5 years were associated with decreased lung function at 7 years of age.13 In contrast, a cross-sectional study using data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in children aged 6–15 years found null associations of urinary OP-metabolite concentrations with current wheeze.14 Regarding the fungicide mancozeb and its metabolite ethylene thiourea (ETU), results from a small (n=66) cross-sectional study performed in France indicated children with higher urinary ETU had higher prevalence of asthma and rhinitis symptoms at ages 3–10 years.15 In Costa Rica, results from the Infants’ Environmental Health Study (ISA)16 showed prenatal exposure to the fungicide mancozeb and ETU during the first, but not second, half of pregnancy, was associated with an increased prevalence of LRTI during the first year of life.17

Several studies16–18 have shown women and children from rural areas in the Costa Rica Caribbean are environmentally exposed to various pesticides used in agriculture, including the fungicides mancozeb, pyrimethanil and thiabendazole, the OP-insecticide chlorpyrifos and the herbicide 2,4-D used in pasture for broad leaved weed control as well as pyrethroid-insecticides used for vector control.16 17 19 20 On large-scale banana plantations, the predominant crops in our study area, mancozeb is generally applied with light aircrafts on a weekly basis to prevent Sigatoka disease, and about 12 other fungicides are being applied by aerial spraying, while the fungicide thiabendazole is being applied postharvest, before packing the fruits for shipment. In addition, bags treated with insecticides, such as chlorpyrifos, are being used, and highly toxic nematicides are being applied 3–4 times a year.21 Regarding vector-control, pyrethroid-insecticides like cypermethrin are used by the Ministry of Health when there is an outbreak of Dengue, chikungunya and Zika fever, and synthetic pyrethroids are commonly used by families at home. Here, we evaluated the association of prenatal and current exposure to chlorpyrifos, pyrethroids, mancozeb, pyrimethanil, thiabendazole and 2,4-D with respiratory and allergic outcomes among 5-year-old children from the ISA study.

METHODS

Study population

As described previously,16 pregnant women were enrolled from March 2010 to June 2011, if aged ≥15 years, <33 weeks of gestation and living within 5 km of banana plantations in Matina County Costa Rica.16 17 Of the 451 women enrolled in the study, 22 (5%) had a miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal/infant death; and 126 (28%) were lost to follow-up before the 5-year study visit in 2015–2016. Mother–child pairs included in this analysis (n=303, 67% attainment since enrolment) were similar in sociodemographic attributes to the initial cohort (n=451) and 293 children provided a urine sample at the 5-year visit.

Data collection

Data collection of the prenatal and early life visits has been described in detail previously.16 17 In this study, we included data from prenatal and 5-year visits. We collected information on sociodemographic and socioeconomic, medical, occupational and environmental variables at each visit (table 1) with a structured questionnaire. We also measured Euclidean distances from residence to the nearest border of closest banana plantation.16 In addition, at each visit, we collected maternal spot urine samples 1–3 times during pregnancy in 100 mL beakers (Vacuette, sterile), aliquoted them into 15 mL tubes (PerformR Centrifuge tubes, Labcon, sterile) and then stored them at −20°C until shipment to the Division of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at Lund University, Sweden, for analysis.1

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and prevalence of select respiratory outcomes among 303 children from the ISA Population at children’s age 5, Matina County, Costa Rica 2015–2016

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Child’s characteristics | ||

| Child’s sex | ||

| Female | 147 | 49 |

| Male | 156 | 51 |

| Child current nutritional status | ||

| Underweight or below | 3 | 1 |

| Normal | 228 | 75 |

| Overweight | 46 | 15 |

| Obese | 23 | 8 |

| Missing | 3 | 1 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 grams) | ||

| Yes | 9 | 3 |

| No | 289 | 95 |

| Missing | 5 | 2 |

| Breast feeding duration | ||

| Less than 6 months | 76 | 25 |

| 6 months or more | 227 | 75 |

| Current cotinine detected in urine (>1 μg/L) | ||

| Yes | 55 | 18 |

| No | 238 | 79 |

| Missing | 10 | 3 |

| Mother’s characteristics | ||

| Parity ≥1 | 195 | 64 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 15 | 5 |

| Cotinine detected in urine during pregnancy (>1 μg/L) | 45 | 15 |

| Maternal smoking history | ||

| Never | 278 | 92 |

| Past | 15 | 5 |

| Current | 10 | 3 |

| Current cotinine detected in urine (maternal) | 45 | 15 |

| Maternal history of asthma | 70 | 23 |

| Current work in agriculture | ||

| Yes | 49* | 14 |

| No | 250 | 83 |

| Missing | 10 | 3 |

| Partner currently works in agriculture | ||

| Yes | 154 | 51 |

| No | 139 | 46 |

| Missing | 10 | 3 |

| Household characteristics | ||

| Current smoking inside house | 32 | 11 |

| Income per capita at enrolment | ||

| Above poverty line | 102 | 34 |

| Poverty | 112 | 37 |

| Extreme poverty | 88 | 29 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Food security‡ | ||

| Low | 194 | 64 |

| Marginal | 69 | 23 |

| High | 30 | 10 |

| Missing | 10 | 3 |

| Daily exposure to smoke of waste burning | 50 | 17 |

| Vector control by ministry of health during last 12 months | 169 | 56 |

| Pesticide use inside home during last 12 months | 152 | 50 |

| Residential distance to banana plantation (metres) | ||

| <50 | 56 | 19 |

| 50–500 | 170 | 56 |

| ≥500 | 77 | 25 |

46 out of 49 mothers currently worked on banana plantations.

138 out of 154 partners currently worked on banana plantations.

Defined using the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Security Scale.

ISA, Infants’ Environmental Health Study.

When the children were 5 years old, we visited their homes again and administered their caretakers, mostly mothers (n=291, 96%), a structured questionnaire to collect data on their child’s health. Information on respiratory and allergic outcomes was collected using the International Study of Allergy and Asthma in Children (ISAAC) questionnaire (in Spanish, previously used in Costa Rica).16 Images or videos for each condition (eg, wheeze, eczema) were provided when applicable. All data were collected using electronic tablets. Children provided a spot urine sample on the day of visit, with help from their caretaker following the same procedures as described before.16 17 Anthropometric measurements, including height, weight and waist circumference, were also taken, as described previously.17

Exposure assessment

Urine samples were analysed for urinary pesticide metabolites using a liquid chromatography mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS; UFLCRX; Shimadzu Corporation) with a triple quadrupole linear ion trap (QTRAP 5500; AB Sciex) and corrected for specific gravity as described previously.16 17 22 We analysed ETU (limit of detection (LOD)=0.08 μg/L) for mancozeb; hydroxypyrimethanil (OHP) (LOD=0.06 μg/L) for pyrimethanil; 5-hydroxythiabendazole (OHT) (LOD=0.03 μg/L) for thiabendazole; 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCP) (LOD=0.05 μg/L) for chlorpyrifos and 3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)–2,2-dimethylcydopropa necarboxylic acid (DCCA) (LOD=0.04 μg/L) for the pyrethroids permethrin, cypermethrin and cyfluthrin; and 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) (LOD=0.03 μg/L) for permethrin, cypermethrin, cyfluthrin, deltamethrin, allethrin, resmethrin and fenvalerate. The herbicide 2,4-D was also measured (LOD=0.02 μg/L). We added the concentrations of 3-PBA and DCCA to create a summary measure of pyrethroid exposure (ΣPyrethroids). The laboratory takes part in the Erlangen interlaboratory programme for TCP and 3-PBA with excellent results (online supplemental material I and II).

We also measured urinary cotinine concentrations (indicator for exposure to cigarette smoke) and urinary 1-hydroxypyerene and hydroxyphenanthrene concentrations. The latter are biomarkers of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons possibly from smoke from wood or waste burning.23 24 As our study was situated in a rural area, we did not measure outdoor pollution (particulate matter (PM) 2.5, PM 10 or ozone). Also, as the Caribbean climate is similar all-year round, without well-defined dry or wet seasons, we also did not consider exposure to pollen.

Outcome assessment

We interviewed mothers or caretakers at home about respiratory and allergic outcomes in their children at 5 years of age with a structured questionnaire. Most questions were from the ISAAC-III questionnaire25 previously used in Costa Rica26 (for more information, see online supplemental table S1). We obtained information about symptoms of asthma (ever and current (=during last 12 months) wheeze), ever doctor-confirmed asthma, current dry cough at night, ever and current LRTI, ever and current rhinitis, ever and current symptoms of eczema (itchy rash) and ever doctor-confirmed eczema. Severe symptoms of asthma were defined as ≥4 attacks of wheeze, or >1 night per week sleep disturbance from wheeze or wheeze-affecting speech in the past 12 months.27

Statistical analyses

We calculated descriptive statistics and distributional plots for all variables. We then estimated bivariate associations between biomarkers of exposure, selected outcomes and covariates using χ2 tests. We estimated correlations between prenatal and current gravity-corrected urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. In our main analyses, we examined associations of prenatal and children’s current urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations (modelled as dichotomous variables: highest quartile (≥75 th percentile (P75)) vs lowest three quartiles (<P75) as we expected effects at relatively high exposures) with selected respiratory and allergic outcomes using multivariable logistic regression models. We also ran our models with pesticide exposures modelled as continuous variables (ie, log10-transformed specific gravity-corrected urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations). Additionally, we ran our logistic regression models with exposure variables obtained via interviews: current maternal and paternal work in agriculture, pesticide use inside or outside home during last 12 months, governmental spraying for vector control during last 12 months and reported exposure to smoke from waste burning (daily or weekly vs less than weekly). We adjusted our multivariable models a priori for maternal smoking during pregnancy (yes/no) and child sex as these have been identified as risk factors for respiratory and allergic diseases in the literature.26 We imputed missing values for covariates (all <5% missing) using data from the nearest available study visit.

We ran several sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our results. First, we ran models that included both prenatal and current exposures in the same model, while adjusting for child sex and maternal smoking during pregnancy. Second, we added additional variables, reported among at least 5% of the children, described in the literature as possible risk or protective factors for respiratory and allergic diseases26 28 that associated (OR >1.5) with one or more of the outcomes and ran models adjusted for: (1) maternal smoking during pregnancy, child sex, parity (0 vs ≥1), breastfeeding (>6 vs ≤6 months); (2) maternal smoking during pregnancy, child sex, parity and maternal history of asthma (yes/no) and (3) models adjusted for current smoking inside house (yes/no), child sex and parity.

Based on the exploratory nature of this analysis, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, we looked for patterns shown by results, instead of focusing on statistical significance (ie, p<0.05). All statistical analyses were conducted in R (V.3.6.1).

RESULTS

A total of 303 children were included in the analysis of prenatal exposures and 293 in the analysis of current exposures. Table 1 shows about half of the children were girls, 75% had a normal nutritional status, almost all (97%) weighed >2500 g at birth, and 75% were breastfed for 6 months or more. Only 5% of mothers smoked during pregnancy. About one-third of households had an income per capita above the poverty line, but 64% experienced low food security. Prevalence of children with ever doctor-confirmed asthma was 12%, while 20% reported current symptoms of asthma (wheeze), 39% dry cough at night and 5% LRTI during the last 12 months (table 2). Fourteen per cent (n=41) of the children had symptoms of severe asthma. Twenty per cent of children had current rhinitis (nasal allergies), 13% had current symptoms of eczema (itchy rash) and 7% had ever doctor-diagnosed eczema. Current wheeze and ever doctor-diagnosed asthma moderately correlated (r=0.49), while other outcomes weakly correlated (wheeze and cough: r=0.31, cough and nasal allergies: r=0.35, others r≤0.2) (online supplemental table S1).

Table 2.

Prevalence of respiratory and allergic outcomes among 303 children from the ISA Population at age 5, Matina County, Costa Rica 2015–2016

| Type of outcome | Outcome | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Respiratory | Ever wheeze (symptom of asthma) | 97 | 32 |

| Current* wheeze (symptom of asthma) † | 62 | 20 | |

| Current symptoms of severe asthma‡ | 33 | 11 | |

| Ever doctor-diagnosed asthma† | 37 | 12 | |

| Current dry cough† | 118 | 39 | |

| Ever LRTI | 49 | 16 | |

| Current LRTI† | 15 | 5 | |

| Allergic | Ever nasal allergies (allergic rhinitis) | 67 | 22 |

| Current nasal allergies (allergic rhinitis) † | 63 | 21 | |

| Current allergic rhinoconjunctivitis | 42 | 14 | |

| Ever itchy rash (symptom of eczema) | 52 | 17 | |

| Current itchy rash (symptom of eczema) † | 39 | 13 | |

| Ever doctor-diagnosed eczema† | 21 | 7 | |

| Current medication for eczema | 8 | 3 | |

Past 12 months.

Selected for epidemiological analysis.

≥4 attacks of wheeze, or >1 night per week sleep disturbance from wheeze, or wheeze affecting speech in the past 12 months.

ISA, Infants’ Environmental Health Study; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection.

The pesticide metabolites presented in table 3 were frequently detected in both prenatal (≥80%) and current urine samples (≥68%). Averaged prenatal and current pesticide metabolite concentrations were not correlated (rs=0–0.25; online supplemental table S2). Prenatal urinary pesticide concentrations generally were highest for ETU (P75=4.66 μg/L), followed by ΣPyrethroids (P75=3.84 μg/L) and 3,5,6 trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCP) (P75=2.52 μg/L). At 5 years, concentrations were usually highest for ΣPyrethroids (P75=8.65 μg/L), followed by DCCA (4.52 μg/L), 3-PBA (P75=3.78 μg/L) and ETU (P75=3.65 μg/L). Prenatal pesticide metabolite concentrations varied more within than between children as intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.14 to 0.41 (table 3).

Table 3.

Prenatal and current specific-gravity adjusted urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations for children from the ISA study at age 5, Matina County, Costa Rica, 2015–2016

| Percentile |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary biomarkers of exposure (μg/L) | Minimum | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | Maximum |

|

| |||||||

| Averaged prenatal concentrations (n=303) † | |||||||

| TCP | 0.41 | 0.92 | 1.31 | 1.75 | 2.52 | 4.19 | 62.96 |

| ETU | 1.03 | 1.87 | 2.34 | 3.32 | 4.66 | 6.16 | 127.38 |

| OHP | <LOD | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.56 | 1.29 | 3.28 | 368.55 |

| OHT | <LOD | <LOD | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.53 | 2.35 | 339.00 |

| 2,4-D | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 1.10 | 79.76 |

| 3-PBA | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 1.35 | 2.46 | 16.96 |

| DCCA | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 1.32 | 2.39 | 3.78 | 23.56 |

| ∑ Pyrethroid* | 0.46 | 0.87 | 1.28 | 2.26 | 3.84 | 5.95 | 40.52 |

| Current child’s concentrations (n=293) § | |||||||

| TCP | 0.29 | 0.69 | 0.98 | 1.51 | 2.31 | 4.04 | 30.85 |

| ETU | <LOD | 0.61 | 1.16 | 2.21 | 3.65 | 6.82 | 66.59 |

| OHP | <LOD | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 1.27 | 3.39 | 445.67 |

| OHT | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.07 | 0.22 | 1.01 | 20.26 |

| 2,4-D | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.71 | 1.49 | 146.85 |

| 3-PBA | 0.15 | 0.52 | 0.98 | 2.09 | 3.78 | 6.93 | 35.92 |

| DCCA | 0.19 | 0.83 | 1.39 | 2.53 | 4.52 | 8.83 | 44.19 |

| ∑ Pyrethroid* | 0.41 | 1.70 | 2.62 | 4.60 | 8.65 | 14.74 | 80.12 |

∑ Pyrethroid: sum of 3-PBA and DCCA.

TCPy, ETU, 3-PBA, DCCA, and 2,4-D=100% > limit of detection (LOD), OHP=96%, OHT=80% > LOD.

Prenatal intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC): TCP=0.41, ETU=0.14, OHP=0.27, OHT=0.39, 2,4-D=0.28, 3-PBA=0.29, and DCCA=0.28.

TCP, 3-PBA, DCCA, and 2,4-D=100% > LOD, ETU=99%, OHP=92%, OHT=68% >LOD.

2,4-D, 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; DCCA, 3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethyl-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid; ETU, ethylenethiourea; ISA, Infants’ Environmental Health Study; LOD, limit of detection; OHP, Hydroxypyrimethanil; OHT, 5-hydroxythiabendazole; 3-PBA, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid; TCP, 3,5,6 trichloro-2-pyridinol.

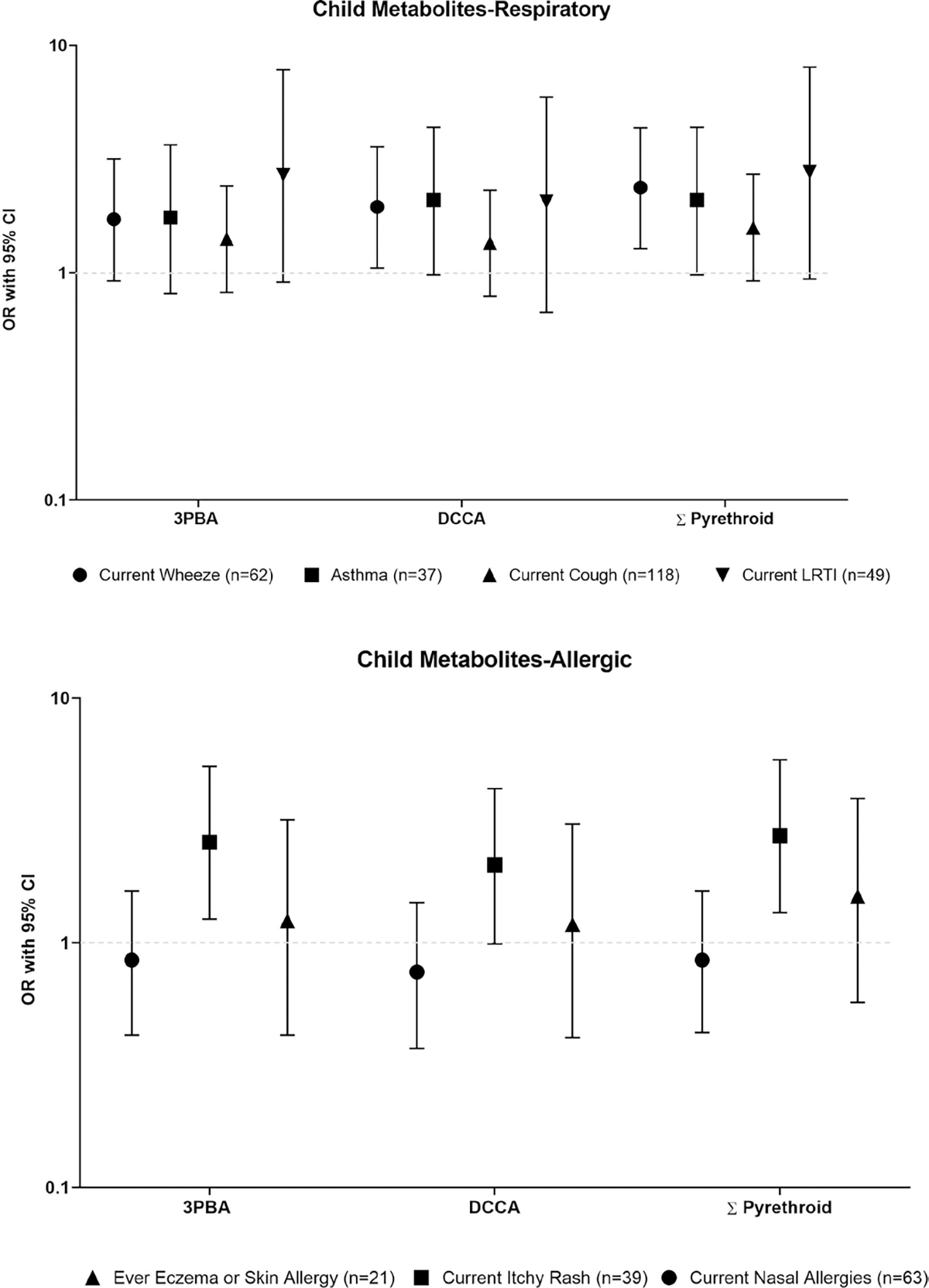

Predominantly pyrethroid exposures were associated respiratory outcomes. Prenatal DCCA and ΣPyrethroid showed an inverse association with asthma (OR=0.21, 95% CI:0.05 to 0.61 and OR=0.39, 95% CI 0.13, 0.98, respectively), but not with other respiratory outcomes. In contrast, children with high current pyrethroid exposures had increased odds of current asthma, ever doctor-diagnosed asthma, current LRTI and, to a lesser extent, current cough (table 4, figure 1). We observed the most precise association for high ΣPyrethroid and wheeze: OR=2.37, 95% CI 1.28 to 4.34). Furthermore, children with high current TCP, ETU, OHP and OHT had increased odds (>2.03) of current LRTI, but these estimates were imprecise, as 95% CI ranged from 0.66 to 6.07 (table 4). When we included exposures as log10-transformed specific gravity-corrected urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations (online supplemental table S3), our findings generally were similar for pyrethroid exposure, for example, for each tenfold increase in ΣPyrethroid, we found increased odds for wheeze (OR=1.99, 95% CI: 0.98 to 4.07), asthma (OR=2.30, 95% CI: 0.96 to 5.57), and current LRTI (OR=3.74, 95% CI: 1.06 to 13.46). Yet, for the other pesticide metabolites the increased odds of LRTI were attenuated, except for ETU (OR: 2.70, 95% CI 0.72, 10.64 for each tenfold increase in ETU). The results of our sensitivity analyses for respiratory outcomes were similar to these presented above (online supplemental tables S4–S8)

Table 4.

ORs, adjusted for maternal smoking during pregnancy and child’s sex, of high (≥P75) specific pesticide exposures and childhood respiratory outcomes during last 12 months

| Current wheeze (N=62) |

Ever doctor-diagnosed asthma (N=37) |

Current dry cough (N=118) |

Current LRTI (N=15) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||||||

| Prenatal metabolites* (n=303) | ||||||||

| TCP | 1.52 | 0.81 to 2.79 | 0.88 | 0.37 to 1.92 | 1.11 | 0.65 to 1.89 | 1.09 | 0.29 to 3.31 |

| ETU | 1.22 | 0.63 to 2.28 | 0.86 | 0.35 to 1.9 | 0.91 | 0.52 to 1.55 | 1.11 | 0.3 to 3.39 |

| OHP | 0.58 | 0.27 to 1.15 | 0.79 | 0.32 to 1.77 | 1.04 | 0.6 to 1.77 | 0.74 | 0.17 to 2.42 |

| OHT | 0.65 | 0.31 to 1.27 | 0.65 | 0.25 to 1.49 | 1.08 | 0.63 to 1.83 | 0.43 | 0.07 to 1.61 |

| 2,4-D | 1.21 | 0.63 to 2.25 | 0.46 | 0.16 to 1.11 | 0.86 | 0.5 to 1.48 | 1.5 | 0.45 to 4.42 |

| 3PBA | 1.22 | 0.64 to 2.27 | 0.6 | 0.23 to 1.38 | 1.15 | 0.67 to 1.96 | 0.7 | 0.16 to 2.31 |

| DCCA | 0.81 | 0.4 to 1.55 | 0.21 | 0.05 to 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.42 to 1.27 | 1.06 | 0.29 to 3.23 |

| ∑ Pyrethroid† | 1.12 | 0.58 to 2.09 | 0.39 | 0.13 to 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.52 to 1.55 | 1.04 | 0.28 to 3.17 |

| Child metabolites* (n=293) | ||||||||

| TCP | 0.94 | 0.48 to 1.79 | 1.14 | 0.5 to 2.46 | 0.78 | 0.45 to 1.35 | 2.05 | 0.66 to 5.89 |

| ETU | 0.58 | 0.27 to 1.15 | 0.66 | 0.25 to 1.53 | 0.94 | 0.54 to 1.61 | 2.09 | 0.68 to 6.02 |

| OHP | 1.21 | 0.63 to 2.26 | 1.4 | 0.62 to 2.97 | 1.29 | 0.75 to 2.2 | 2.1 | 0.68 to 6.07 |

| OHT | 1.17 | 0.61 to 2.2 | 1.82 | 0.84 to 3.8 | 0.91 | 0.52 to 1.56 | 2.03 | 0.66 to 5.85 |

| 2,4-D | 0.84 | 0.42 to 1.61 | 0.54 | 0.19 to 1.28 | 0.76 | 0.43 to 1.31 | 1.47 | 0.45 to 4.32 |

| 3PBA | 1.72 | 0.92 to 3.17 | 1.75 | 0.81 to 3.66 | 1.41 | 0.82 to 2.41 | 2.7 | 0.91 to 7.82 |

| DCCA | 1.95 | 1.05 to 3.58 | 2.09 | 0.98 to 4.36 | 1.35 | 0.79 to 2.31 | 2.06 | 0.67 to 5.93 |

| ∑ Pyrethroid† | 2.37 | 1.28 to 4.34 | 2.09 | 0.98 to 4.36 | 1.58 | 0.92 to 2.71 | 2.78 | 0.94 to 8.04 |

ISA study at 5 years of age, Matina County, Costa Rica 2015–2016.

Variables dichotomised at 75th percentile; reference: below 75th percentile.

∑ Pyrethroid: sum of PBA and DCCA.

2,4-D, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; ETU, ethylenethiourea; OHP, hydroxypyrimethanil; OHT, 5-hydroxythiabendazole; 3-PBA, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid, DCCA: 3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethyl-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid; TCP, 3,5,6 trichloro-2-pyridinol.

Figure 1.

ORs, adjusted for maternal smoking during pregnancy and child’s sex, of high (≥P75) Σpyrethroid exposures and childhood respiratory and allergic outcomes. ISA study at 5 years of age, Matina County, Costa Rica 2015–2016. ORs presented on the logarithmic scale. 3-PBA, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid, DCCA, 3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethyl-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid.

We observed mostly null associations of prenatal pesticide exposures with allergic outcomes (table 5), except for high urinary TCP concentrations that were associated with decreased odds of rhinitis (OR=0.49, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.98), and high urinary OHP concentrations that were associated with increased odds of ever doctor-diagnosed eczema (OR=2.39, 95% CI 0.94 to 5.90). Yet, when modelling these exposures as continuous variables, associations were attenuated for prenatal TCP and current nasal allergies (OR=0.63, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.66) as well as prenatal OHP and ever eczema (OR=1.19, 95% CI 0.59 to 2.25) (online supplemental table S9). In addition, high current pyrethroid exposure was associated with current itchy rash (ie, ΣPyrethroid OR=2.74, 95% CI 1.33 to 5.60), but not with current nasal allergies, or ever eczema (figure 1, table 4). The latter association remained when we modelled current pyrethroid exposure as a continuous variable (OR per 10-fold increase in ΣPyrethroid concentrations: 2.90 (95% CI 1.24 to 6.92) (online supplemental table S9). The sensitivity analyses we ran for models of allergic symptoms showed similar findings as presented above (online supplemental tables S10–S14).

Table 5.

ORs adjusted for maternal smoking during pregnancy, child’s sex of high (≥P75) specific pesticide exposures and childhood allergic outcomes during last 12 months unless indicated elsewise, ISA study at 5 years of age, Matina County, Costa Rica 2015–2016

| Current nasal allergies (allergic rhinitis) (n=63) |

Current itchy rash (atopic eczema) (n=39) |

Ever doctor-diagnosed eczema (n=21) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR† | 95% CI | OR† | 95% CI | OR† | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||||

| Prenatal metabolites* (n=303) | ||||||

| TCP | 0.49 | 0.22 to 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.33 to 1.74 | 0.68 | 0.19 to 1.91 |

| ETU | 0.74 | 0.36 to 1.42 | 0.66 | 0.26 to 1.51 | 0.68 | 0.19 to 1.91 |

| OHP | 1.39 | 0.74 to 2.54 | 1.03 | 0.45 to 2.21 | 2.39 | 0.94 to 5.9 |

| OHT | 0.64 | 0.31 to 1.25 | 1.37 | 0.63 to 2.86 | 0.94 | 0.3 to 2.49 |

| 2,4-D | 1.36 | 0.72 to 2.51 | 1.22 | 0.55 to 2.56 | 0.95 | 0.3 to 2.54 |

| 3PBA | 1.24 | 0.65 to 2.28 | 0.53 | 0.2 to 1.22 | 1.56 | 0.57 to 3.93 |

| DCCA | 1.01 | 0.52 to 1.89 | 1.13 | 0.5 to 2.38 | 1.21 | 0.42 to 3.12 |

| ∑ Pyrethroid† | 1.01 | 0.52 to 1.88 | 0.8 | 0.33 to 1.76 | 1.57 | 0.57 to 3.97 |

| Child metabolites* (n=293) | ||||||

| TCP | 0.96 | 0.48 to 1.8 | 0.58 | 0.22 to 1.33 | 0.92 | 0.29 to 2.44 |

| ETU | 0.51 | 0.23 to 1.04 | 1.37 | 0.63 to 2.86 | 0.29 | 0.05 to 1.05 |

| OHP | 1.32 | 0.69 to 2.44 | 1.24 | 0.55 to 2.62 | 0.68 | 0.19 to 1.92 |

| OHT | 1.19 | 0.62 to 2.21 | 1.56 | 0.73 to 3.24 | 0.29 | 0.05 to 1.04 |

| 2,4-D | 1.19 | 0.62 to 2.21 | 1.16 | 0.52 to 2.45 | 1.24 | 0.43 to 3.21 |

| 3PBA | 0.85 | 0.42 to 1.63 | 2.58 | 1.25 to 5.27 | 1.23 | 0.42 to 3.18 |

| DCCA | 0.76 | 0.37 to 1.46 | 2.08 | 0.99 to 4.27 | 1.19 | 0.41 to 3.06 |

| ∑ Pyrethroid† | 0.85 | 0.43 to 1.63 | 2.74 | 1.33 to 5.6 | 1.55 | 0.57 to 3.89 |

Variables dichotomised at 75th percentile; reference: below 75th percentile

∑ Pyrethroid: sum of PBA and DCCA.

2,4-D, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; ETU, ethylenethiourea; ISA, Infants’ Environmental Health Study; OHP, hydroxypyrimethanil; OHT, 5-hydroxythiabendazole; 3-PBA, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid; 3-PBA, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid, DCCA: 3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethyl-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid; TCP, 3,5,6 trichloro-2-pyridinol.

A total of 56% of participants reported governmental pesticide spraying at their homes for vector control during the last 12 months, which includes manually application of pyrethroid insecticides with motorised equipment (table 1). Vector control was associated with children’s current cough (OR=1.77, 95% CI:1.08 to 2.91), and current LRTI (OR=2.78, 95% CI 0.84 to 12.53) (online supplemental table S15). Other environmental or occupational exposures like maternal or paternal work in agriculture, pesticide use at home or smoke from environmental waste burning were not associated with children’s respiratory outcomes or allergic symptoms (online supplemental tables S15, S16).

DISCUSSION

We found current, but not prenatal, pesticide exposures were consistently associated with respiratory and allergic outcomes among 5-year-old children. Particularly current exposures to pyrethroid insecticides may contribute to children’s asthma, LRTI and symptoms of eczema (itchy skin rash) at 5 years of age. Current vector control spraying by government, which includes application of pyrethroids, was associated with cough and LRTI. Furthermore, current mancozeb/ETU exposure was somewhat associated with more frequent LRTI. Unexpectedly, children with increased prenatal pyrethroid exposures had less often ever doctor-diagnosed asthma, and the estimated OR was even smaller after adjusting for maternal asthma. Possibly, mothers with asthma used more frequently pyrethroid insecticides during pregnancy, resulting in increased prenatal exposures to pyrethroids. Yet, these prenatal pyrethroids do not seem to lead to an increased asthma at 5 years of age.

Similar to our findings, a birth cohort in Cincinnati found null associations of prenatal urinary pyrethroid metabolite concentrations with wheeze among children aged 8, but no current exposure levels were reported.29 In contrast to our findings, a cohort in New York City reported higher prenatal permethrin and air concentrations were associated with cough, but not wheeze, in children aged 5 years.30 An analysis among a subset of these children indicated prenatal indoor air PBO (a synergist for pyrethroid insecticides), but not current PBO or permethrin, which was associated with cough at age 5–6 years, but not with asthma or wheeze.11 Furthermore, current permethrin was associated with total IgE levels, but not indoor allergen-specific IgE. The authors hypothesised the effect of permethrin exposure, which may have been driven by sensitisation to outdoor pollen or food allergens, and mentioned that cough may be a result of sensory nerve irritation by pyrethroids.11 With respect to studies among adults exposed to pyrethroids, their findings are consistent with ours. The Agricultural Health Study in USA reported current use of pyrethroids was associated with wheeze in farmers,6 31 allergic asthma in farmers32 and female spouses33 as well as non-allergic asthma in female spouses.33 A study among rural women workers in South Africa found pyrethroid exposure was associated with the activation of T-helper cells type 2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13), these mechanisms may be involved in the development of asthma-related outcomes.34

We previously reported increased urinary ETU (metabolite of mancozeb) during the first half of pregnancy was associated with an increased odds of LRTI during the first year of life.17 In this study, we observed that higher current ETU was somewhat associated with an increased odds of current LRTI; the estimate was imprecise as only 5% of the children had current LRTI. Still, our results suggest a continued effect of high mancozeb/ETU exposure on children’s respiratory health. This is somewhat consistent with results from a cross-sectional study among children aged 3–10 years in France (n=66) in which higher urinary ETU was positively associated with symptoms of asthma and rhinitis.15 Data from occupational studies have shown dithiocarbamate fungicides like mancozeb may affect respiratory function by modulating the immune system, inducing macrophage activation and enhancing the inflammatory response.35–37 Median prenatal and current urinary ETU concentrations in our study were about threefold higher than the study in France,15 which may be explained by the frequent aerial applications of mancozeb performed in the ISA study area.

With respect to OP pesticides, such as chlorpyrifos, results from the CHAMACOS birth cohort have shown both increased prenatal urinary OP-metabolite concentrations during the second half of pregnancy and higher cumulative OP-exposure during childhood were associated with higher odds of respiratory symptoms at ages 5 and 712 and decreased lung function at age 7.13 In addition, repeated data of 16 school-aged children (6–16 years) with asthma who lived in a farmworker community in Washington State showed that children with higher urinary OP-metabolite concentrations had elevated leukotrienes, an indicator of asthma exacerbation.38 In our study, we measured urinary TCP, a specific metabolite of chlorpyrifos, instead of general OP-metabolites, and found null associations for prenatal and current TCP with most respiratory or allergic outcomes at age 5 years. Although imprecise, children with high current TCP concentrations had increased odds of LRTI, whereas those with high prenatal TCP concentrations had decreased odds of eczema. Yet, these associations were attenuated when analysing TCP as a continuous variable. Although research in children is limited, studies in adults have shown associations between exposure to chlorpyrifos and respiratory outcomes. For example, a study of 69 indigenous women in Costa Rica reported increased odds of wheezing among non-smoker women exposed to chlorpyrifos-treated bags.39 Additionally, a cross-sectional study of 496 Dow Chemical Company’s (Midland, MI, USA) employees who worked in chlorpyrifos production found increased odds of acute respiratory infections (OR: 1.49; 95% CI 1.8 to 2.5) as compared with unexposed workers (n=911) matched for age, race, sex, pay and year of hire.40 Animal and in vitro studies have demonstrated possible mechanisms of chlorpyrifos on respiratory outcomes. In guinea pigs, chlorpyrifos induced airway hyperactivity via neuronal M2 receptor disfunction, a mechanism involved with asthma.32 Furthermore, an in vitro study observed that chlorpyrifos inhibited the proinflammatory function of macrophages, which may be related to pesticide-induced immunosuppression41 and contribute to LRTI.

Assessment of pesticide exposure and its effects on human health are difficult. Although biomonitoring of pesticide-specific metabolites is generally considered the gold standard for exposure assessment, metabolites of current-use pesticides mostly reflect exposures during the 24 hours prior to sample collection.10 Given the intermittent nature of pesticide use, accurately characterising chronic exposures is challenging, which is reflected by the relatively low intraclass correlation coefficients (0.14–0.41) of our repeat prenatal urine samples, and will most likely result in non-specific misclassification of exposure and attenuation of effect estimates. Our study is challenged by its relatively small sample size. We have successfully followed 303 children and their mothers from pregnancy until 5 years of age (67% follow-up), which is a strength. As mother–child pairs included in this analysis were similar in sociodemographic attributes to the initial cohort, selection bias is unlikely. However, since exposure is hard to quantify well and some of the outcomes were rare (ie, LRTI 5%), this study would benefit from a larger sample size with more measurements of pesticide exposure to adequately address the questions related to pesticide exposure and respiratory health.

In our study, we observed a high prevalence of respiratory outcomes measured through the validated and widely used ISAAC questionnaires. In 2012, the global estimated prevalence for symptoms of asthma (defined by self-reported wheezing during last 12 months), rhinitis and symptoms of eczema among children age 6–7 years were 12%, 9% and 8%, respectively.2 Compared with these estimates, our population had a higher prevalence of symptoms of asthma (wheezing) (20%), rhinitis (20%) and symptoms of eczema (13%). The 2014 ISAAC Survey in Costa Rica reported a similar prevalence of symptoms of asthma of 24% and eczema (16%), and a higher prevalence of rhinitis (40%) among 6–7-year-old children in Costa Rica.26 Overall, these estimates demonstrate that respiratory and allergic outcomes are an important public health concern for children in Costa Rica.

In conclusion, our study shows that children living in a rural area with large-scale banana farming for export purposes in Costa Rica are exposed to pesticides used in agriculture and vector control, and their exposure levels are relatively high. Given the associations of pesticide exposure with adverse outcomes, interventions to reduce children’s pesticide exposure such as elimination of mosquito breeding sites, diversification of monoculture systems, improvement of soil quality, use of non-chemical pest control methods, integrated pest management, revision of application methods and increase in the distance between pesticide applications and residential areas are warranted.

Our findings indicate that current pyrethroid exposure is associated with asthma, wheeze, LRTI and allergic skin rashes. Our results also show that mancozeb exposure may be associated with LRTI. These findings are important as pyrethroids are broadly used worldwide at home and in agriculture, and mancozeb is one of the most-used fungicides in agriculture, possibly putting children’s health at risk.

Supplementary Material

What is the key question?

Are prenatal and current pesticide exposures associated with children’s respiratory and allergic outcomes?

What is the bottom line?

Current, but not prenatal, pesticide exposures were consistently associated with respiratory and allergic outcomes among 5-year-old children, particularly pyrethroid exposures.

Why read on?

Very little is known about the effects of pesticides on children’s respiratory and allergic outcomes, despite their extensive use.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the families participating in the ISA study and community partners for sharing their time and information with us. We would also like to thank Michael Cuffney, Juan Camilo Cano, Rosario Quesada, Claudia Hernandez, Diego Hidalgo, Marcela Quirós Lépiz, Alighierie Fajardo Soto, Marie Bengtsson, Daniela Pineda, Moosa Faniband, and Margareta Maxe for their fieldwork, laboratory analyses, and/or data management assistance.

Funding

This publication was made possible by research supported by grant numbers: PO1 1 05 296–001 (IDRC); 2010–1211, 2009–2070, and 2014–01095 (Swedish Research Council Formas); R21 ES025374 (NIEHS); and R24 ES028526 (NIEHS).

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not applicable.

Ethics approval This study involves human participants and was approved by Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad Nacional (CECUNA) registered at IORG with number IRB00006855, approval numbers: CECUNA-11-2009; CECUNA-05-201 7. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement Data are available upon request. Deidentified participant data are stored in a secure server by the ISA study team. Please contact the corresponding author for interest in potential data access.

Additional supplemental material is published online only. To view, please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-218068).

REFERENCES

- 1.Forum of International Respiratory Societies. The global impact of respiratory disease-2A ED. 2. Sheffield: European Respiratory Society, 2017. ISBN: 9781849840880. https://www.who.int/gard/publications/The_Global_Impact_of_Respiratory_Disease.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallol J, Crane J, von Mutius E, et al. The International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (Isaac) phase three: a global synthesis. Allergol Immunopathol 2013;41:73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubner FJ, Jackson DJ, Evans MD, et al. Early life rhinovirus wheezing, allergic sensitization, and asthma risk at adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:501–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buralli RJ, Dultra AF, Ribeiro H. Respiratory and allergic effects in children exposed to Pesticides-A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082740. [Epub ahead of print: 16 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamane A, Baldi I, Tessier J-F, et al. Occupational exposure to pesticides and respiratory health. Eur Respir Rev 2015;24:306–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, Long S, et al. Pesticides are associated with allergic and non-allergic wheeze among male farmers. Environ Health Perspect 2017;125:535–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, London SJ, et al. Pesticides and adult respiratory outcomes in the agricultural health study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1076:343–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldi I, Robert C, Piantoni F, et al. Agricultural exposure and asthma risk in the AGRICAN French cohort. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2014;217:435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Negatu B, Kromhout H, Mekonnen Y, et al. Occupational pesticide exposure and respiratory health: a large-scale cross-sectional study in three commercial farming systems in Ethiopia. Thorax 2017;72:498.1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenske RA, Bradman A, Whyatt RM, et al. Lessons learned for the assessment of children’s pesticide exposure: critical sampling and analytical issues for future studies. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:1455–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B, Jung KH, Horton MK, et al. Prenatal exposure to pesticide ingredient piperonyl butoxide and childhood cough in an urban cohort. Environ Int 2012;48:156–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raanan R, Harley KG, Balmes JR, et al. Early-Life exposure to organophosphate pesticides and pediatric respiratory symptoms in the CHAMACOS cohort. Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raanan R, Balmes JR, Harley KG, et al. Decreased lung function in 7-year-old children with early-life organophosphate exposure. Thorax 2016;71:148–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perla ME, Rue T, Cheadle A, et al. Biomarkers of insecticide exposure and asthma in children: a national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999–2008 analysis. Arch Environ Occup Health 2015;70:309–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raherison C, Baldi I, Pouquet M, et al. Pesticides exposure by air in vineyard rural area and respiratory health in children: a pilot study. Environ Res 2019;169:189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Wendel de Joode B, Mora AM, Córdoba L, et al. Aerial application of mancozeb and urinary ethylene thiourea (ETU) concentrations among pregnant women in Costa Rica: the infants’ environmental health study (Isa). Environ Health Perspect 2014;122:1321–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mora AM, Hoppin JA, Córdoba L, et al. Prenatal pesticide exposure and respiratory health outcomes in the first year of life: results from the infants’ environmental health (Isa) study. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2020;225:113–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Wendel de Joode B, Mora AM, Lindh CH, et al. Pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in children aged 6–9 years from Talamanca, Costa Rica. Cortex 2016;85:137–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Córdoba Gamboa L, Solano Diaz K, Ruepert C, Córdoba L, Solano K, et al. Passive monitoring techniques to evaluate environmental pesticide exposure: results from the infant’s environmental health study (Isa). Environ Res 2020;184:109243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Wendel de Joode B, Mora AM, Lindh CH, et al. Pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in children aged 6–9 years from Talamanca, Costa Rica. Cortex 2016;85:137–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bravo V, de la C Malavassi E, Herrera G Uso de plaguicidas en cultivos agricolas como agriculture pesticides use as tool for monitoring health. Uniciencia 2013;27:351–76 www.revistas.una.ac.cr/uniciencia [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norén E, Lindh C, Rylander L, et al. Concentrations and temporal trends in pesticide biomarkers in urine of Swedish adolescents, 2000–2017. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2020;30:756–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhamdow A, Lindh C, Albin M, et al. Early markers of cardiovascular disease are associated with occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Sci Rep 2017;7:9426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeng HA, Pan C-H. 1-Hydroxypyrene as a biomarker for environmental health, 2015: 595–612. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellwood P, Asher M, Beasley R. Phase three manual, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soto-Martínez ME, Yock-Corrales A, Camacho-Badilla K, et al. The current prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema related symptoms in school-aged children in Costa Rica. J Asthma 2019;56:360–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai CKW, Beasley R, Crane J, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three of the International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (Isaac). Thorax 2009;64:476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherriff A, Peters TJ, Henderson J, et al. Risk factor associations with wheezing patterns in children followed longitudinally from birth to 3(1/2) years. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1473–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilden R, Friedmann E, Holmes K, et al. Gestational pesticide exposure and child respiratory health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reardon AM, Perzanowski MS, Whyatt RM, et al. Associations between prenatal pesticide exposure and cough, wheeze, and IgE in early childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:852–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, London SJ, et al. Chemical predictors of wheeze among farmer pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:683–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, London SJ, et al. Pesticide use and adult-onset asthma among male farmers in the agricultural health study. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, London SJ, et al. Pesticides and atopic and nonatopic asthma among farm women in the agricultural health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mwanga HH, Dalvie MA, Singh TS, et al. Relationship between pesticide metabolites, cytokine patterns, and asthma-related outcomes in rural women workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13100957. [Epub ahead of print: 27 Sep 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weis GCC, Assmann CE, Cadoná FC, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of mancozeb, chlorothalonil, and thiophanate methyl pesticides on macrophage cells. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019;182:109420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colosio C, Barcellini W, Maroni M, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of occupational exposure to mancozeb. Arch Environ Health 1996;51:445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corsini E, Birindelli S, Fustinoni S, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of the fungicide mancozeb in agricultural workers. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005;208:178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benka-Coker WO, Loftus C, Karr C, et al. Characterizing the joint effects of pesticide exposure and criteria ambient air pollutants on pediatric asthma morbidity in an agricultural community. Environ Epidemiol 2019;3:e046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fieten KB, Kromhout H, Heederik D, et al. Pesticide exposure and respiratory health of Indigenous women in Costa Rica. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:1500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burns CJ, Cartmill JB, Powers BS, et al. Update of the morbidity experience of employees potentially exposed to chlorpyrifos. Occup Environ Med 1998;55:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helali I, Ferchichi S, Maaouia A, et al. Modulation of macrophage functionality induced in vitro by chlorpyrifos and carbendazim pesticides. J Immunotoxicol 2016;13:745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.