Abstract

Background:

The vestibular system has been implicated in the pathophysiology of episodic motor impairments in PD but specific evidence remains lacking.

Objective:

We investigated the relationship between the presence of freezing of gait and falls and postural failure during the performance on Romberg test condition 4 in persons with PD.

Methods:

Modified Romberg sensory conflict test, fall and freezing of gait assessments were performed in 92 patients with PD (M70/F22; mean age 67.6±7.4 years, Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.4±0.6; mean Montreal cognitive assessment, 26.4±2.8).

Results:

Failure during Romberg condition 4 was present in 33 patients (35.9%). Patients who failed the Romberg condition 4 were older, had more severe motor and cognitive impairments than those without. 84.6% of all freezers had failure during Romberg condition 4 whereas 13.4% of freezers had normal performance (χ2=15.6; P<0.0001). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the regressor effect of Romberg condition 4 test failure for the presence of freezing of gait (Wald χ2=5.0; P=0.026) remained significant after accounting for the degree of severity of parkinsonian motor ratings (Wald χ2=6.2; P=0.013), age (Wald χ2=0.3; P=0.59) and cognition (Wald χ2=0.3; P=0.75; Total model: Wald χ2=16.1; P<0.0001). PD patients who failed the Romberg condition 4 (45.5%) did not have a statistically significant difference in frequency of fallers compared to PD patients without abnormal performance (30.5%; χ2=2.1; P=0.15).

Conclusion:

The presence of deficient vestibular processing may have specific pathophysiological relevance for freezing of gait but not falls in PD.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, falls, freezing of gait, vestibular efficacy, modified Romberg test

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by resting tremor, slowness of movement, rigidity as well as postural instability and gait difficulties (PIGD). For decades it has been speculated that PD is associated with dysfunction of the vestibular system (esp., given that postural instability is one of the major symptoms of PD) but clear evidence of such a connection has been slow to emerge1. Vestibular impairment, particularly chronic bilateral vestibular dysfunction is a significant contributor to imbalance and falls in otherwise normal older adults2. Abnormal findings on the modified sensory conflict Romberg test in older adults with deficient vestibular efficacy result in significantly increased odds of falling even in the absence of an overt history of dizziness2. This finding suggests that the age-associated sub-clinical vestibular dysfunction captured by the sensory conflict postural tests is clinically relevant. Abnormal vestibular efficacy is also common in PD3–5. Turning is a common trigger for falls and one of the most effective maneuvers to elicit FoG in PD6. In terms of multisensory integration for effective postural and gait control, vestibular feedback becomes more critical when initiating turning7, where visual and somatosensory feedback become more unreliable8. These findings suggest that vestibular efficacy is implicated in turning-associated PIGD motor features in PD, such as falls and FoG. We have conceptually defined as vestibular efficacy as the ability of the central nervous system to process and integrate vestibular sensory information into downstream neural pathways. Although it may in part result from it is not the same as (peripheral) vestibular dysfunction. The primary goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that abnormal performance on the modified sensory conflict Romberg test condition 4 - which increases vestibular burden during postural control - is an important risk factor for falls and FoG in patients with PD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This cross-sectional study involved 92 patients with PD: M70/F22; mean age 67.6±7.4 years, mean motor disease duration 6.0±4.6 years. PD subjects met the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank clinical diagnostic criteria9. Patients in Hoehn & Yahr stage 5 or with dementia were not eligible for the study. Mean Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCa, was 26.4±2.810. Most subjects had moderate severity of disease: 6 subjects in stage 1, 3 in stage 1.5, 20 in stage 2, 40 in stage 2.5, 20 in stage 3, and 3 in stage 4 of the modified Hoehn and Yahr classification with mean stage of 2.5±0.6. Our rationale for including patients with (at least clinically defined) normal balance is that postural imbalance is not always an essential component of FoG11, 12. Thirty-one Parkinson’s disease subjects were taking a combination of dopamine agonist and carbidopa-levodopa medications, 45 were using carbidopa-levodopa alone, 10 were taking dopamine agonists alone and 6 were not receiving dopaminergic drugs. Subjects with evidence of large vessel stroke or other intracranial lesions on anatomic imaging were excluded.

Clinical assessment

The movement disorder society-revised unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (MDS-UPDRS) motor examination was performed in the morning in the dopaminergic medication ‘off’ state. The mean motor examination score on the MDS-UPDRS was 35.5 ± 14.213. Participants were asked about a history of falling, even a single fall. A fall was defined as an unexpected event during which a person falls to the ground. We did not exclude falls due to a specific etiology. FoG status was defined by direct observation of motor freezing behavior by an experienced neurologist while performing the MDS-revised UPDRS motor examination in the DA medication off state (i.e., score on MDS-UPDRS item 3.11 > 0) and in the setting of patient self-reported FoG. Fall status was determined as presence or absence of any reported falls within the prior year.

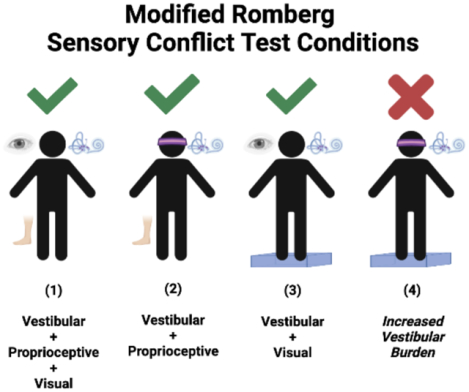

Modified Romberg 1–4 tests of Standing Balance on Firm and Compliant Support Surfaces14, 15.

The modified Romberg test is similar to the Sensory Organization Test (SOT) where the Romberg 4 subtest corresponds to falls on the SOT5 subtest, which has been found to have a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 80% to diagnose a vestibular disorder16. The modified Romberg Test examines the ability to stand unassisted using 4 test conditions designed specifically to test the sensory inputs that contribute to balance—the vestibular system, vision, and proprioception17. The different conditions are condition 1 standing on firm surface with eyes open while depending on visual, proprioceptive and vestibular input; Condition 2: standing on firm surface with eyes closed while depending in proprioceptive and vestibular input; and Condition 3: standing on compliant surface with eyes open while depending on visual and vestibular input. The fourth test condition is designed to focus more specifically on vestibular function: participants have to maintain balance on a foam-padded surface (to obscure proprioceptive input) with their eyes closed (to eliminate visual input). A time to fall < 20 seconds on the Romberg 4 test (standing on foam surface with eyes closed) in the absence of falling on subtests 1–3 was defined as abnormal condition test performance15, and as previously validated in prior study of patients with vestibular disorders18. Participants had a single attempt per condition unless the participant did not properly understood or followed the instructions. A research assistant was standing at arm length to protect the participant in case of a fall.

This study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02458430 & NCT01754168) was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan School of Medicine and Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Findings of episodic and non-episodic mobility disturbances (i.e., freezing of gait and falls) and neurotransmitter brain PET changes obtained in a subset of the same cohort of patients in this study have been and will be published elsewhere19, 20.

Statistical analysis

Standard pooled-variance t or Satterthwaite’s method of approximate t tests (tapprox) were used for group comparisons. 2 × 2 contingency χ2 testing was performed for comparison of proportions of fall status (0 falls versus 1 fall or more) and FoG (no freeze versus freeze) between the two Romberg test groups (Romberg condition 4 pass versus fail while passing conditions 1–3). Multiple logistic regression was performed using FoG status as the outcome parameters while accounting for confounder variables (age, total motor UPDRS motor scores and MOCA) that were shown to be different between the two Romberg test groups. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4, SAS institute, Cary, NC.

RESULTS

Selective test failure on Romberg condition 4

Failure during Romberg condition 4 was present in 33 patients (35.9%). Table 1 lists mean (± SD) values of demographic and clinical variables in the patients with versus without failure during Romberg condition 4. PD patients with failure during Romberg condition 4 were older, had more severe motor impairments, and lower cognitive performance compared to patients with non-failure during Romberg condition 4 (Table 1). For example, the frequency of failure during Romberg condition 4 was 10.3% in stage 1–2, 37.5% in stage 2.5, 65% in stage 3 and 66.7% in stage 4 of the modified Hoehn and Yahr scale.

Table 1.

Mean (± SD) values of demographic and clinical variables in the patients with versus without failure during Romberg condition 4. Gender distribution is presented as proportions. Standard pooled-variance t or Satterthwaite’s method of approximate t tests (tapprox) were used for group comparisons. Levels of statistical difference between groups are presented in the last column.

| PD with failure during Romberg condition 4 (n=33) | PD without failure during Romberg condition 4 (n=59) | Group comparison (significance) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr.) | 71.7±7.5 | 66.2±6.3 | t=4.40, P<0.0001 |

| Gender (M/F) | 25/6 | 45/14 | χ2=0.003, P=0.96 |

| Duration of motor PD (yr.) | 6.4±3.8 | 5.8±4.9 | t=0.64, P=0.53 |

| MDS UPDRS total motor score | 37.4±14.5 | 33.1±12.1 | t=3.73, P=0.0004 |

| MoCa | 25.6±3.1 | 26.9±2.5 | t=2.21, P=0.03 |

| LED | 675±331 | 629±430 | t=0.52, P=0.60 |

Failure during Romberg condition 4 and FoG

84.6% of all freezers had abnormal vestibular efficacy whereas 13.4% of freezers had normal vestibular efficacy (Likelihood ratio χ2=15.6; P<0.0001; table 2).

Table 2.

Two-by-two contingency tables for the proportional association between Romberg test condition 4 performance and FoG status.

| Contingency table of FoG vs. Romberg test condition 4 performance status in PD (Likelihood ratio χ2=15.6; P<0.0001) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No failure during Romberg condition 4 | Failure during Romberg condition 4 | Total | |

| No FoG | 57 | 22 | 79 |

| FoG | 2* | 11** | 13 |

| Total | 59 | 33 | 92 |

FoG was present in 3.3% in PD persons without failure during Romberg condition 4

Failure during Romberg condition 4 was present in 84.6% of PD freezers

Confounder analysis for association between failure during Romberg condition 4 and FoG

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the regressor effect of failure during Romberg condition 4 for the presence of FoG (Wald χ2=5.0; P=0.026; Odds Ratio, OR, estimate 7.96 with 5–95% CI 1.28–49.4) remained significant independent from the degree of severity of MDS-UPDRS part III motor ratings (Wald χ2=6.2; P=0.013; OR estimate 1.10 with 5–95% CI 1.02–1.19), age (Wald χ2=0.3; P=0.59) and MoCa (Wald χ2=0.3; P=0.75; Total model: Wald χ2=16.1; P<0.0001; Somers’ D = 0.81; Concordance ratio = 90.7%).

Failure during Romberg condition 4 and falls

The frequency of PD fallers was higher in PD patients with failure during Romberg condition 4 (45.5%) compared to PD patients with non-failure during Romberg condition 4 (30.5%) but this was not statistically significant (Likelihood ratio χ2=2.1; P=0.15; table 3).

Table 3.

Two-by-two contingency tables for the proportional association between Romberg condition 4 test performance and fall status.

| Contingency table of fall history vs. clinical deficient vestibular efficacy status in PD (Likelihood ratio χ2=2.1; P=0.15) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No failure during Romberg condition 4 | Failure during Romberg condition 4 | Total | |

| No fall history | 41 | 18 | 59 |

| Fall history | 18* | 15** | 33 |

| Total | 59 | 33 | 92 |

Fall history present in 30.5% in PD persons without failure during Romberg condition 4

Failure during Romberg condition 4 present in 45.5% of PD fallers

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that selective failure during Romberg condition 4 may be a specific independent contributor the FoG but not with falls in patients with PD. During normal locomotion, sensory signals from visual, vestibular, and somatosensory systems are integrated via central neural networks and provide real-time information used as references for cognitive, emotional, and automatic locomotor processes21. Therefore, the inability to integrate postural sensory inputs may play a role in the pathophysiology of FoG21. For example, FoG can be provoked under sensory conflicting situations in which balance is challenged but in different circumstances sensory cues may alleviate motor freezing behaviors6. Prior studies using postural sensory conflict tasks, such as the sensory organization test (SOT), have demonstrated that postural sensory deficits involving specific sensory modalities are strongly associated with FoG in PD22. However, there is limited literature on vestibular sensory processing in FoG23. A recent study using a SOT testing paradigm found that PD freezers had greater difficulties processing vestibular sensory information than non-freezers22. Interestingly, relative effects of vestibular processing were greater than visual and somatosensory effects. These data show that the inability to integrate vestibular information for postural balance may be an important contributor to FoG. Vestibular feedback becomes especially critical when initiating walking or turning7, where visual and somatosensory feedback become more unreliable8. This is consistent with the observation that gait initiation and turning are well-known risk factors for FoG provocation6. With respect to turning, a prior study investigated the effects of galvanic vestibular stimulation triggered at either gait initiation, a step before the potential turn, or at the time of appearance of the visual cue to make a turn7. Although the visual and vestibular perturbations significantly altered gait trajectory, the greatest interaction occurred when galvanic stimulation was triggered one step before the target appeared. This implies an increase in the weighting of vestibular inputs just before turning to prepare for the change in direction. These observations may explain why vestibular sensory processing deficits, such as seen in deficient vestibular efficacy, may play a role in FoG but does not provide insights for the lack of association with falls. However, falls may represent a more complex and more heterogenous episodic motor disturbance24, because of a plethora of fall triggering factors not limited to gait initiation or falls (e.g., inattention, neuropathy, musculoskeletal discomfort, deconditioning, frailty, mechanical slips, environmental obstacles, spoor lightning, poor vision, side-effects of anti-cholinergic or sedative drugs, bladder urgency or any combinations of these, etc.). Furthermore, falls represent stochastic or more random events and may also be affected by emotional factors due to fear of falling. It is also possible that the absence of a significant fall status effect was due to our limited assessment based on patient’s reporting a history of a prior fall. We believe that some of the less forceful but purely mechanical triggered falls represent a mechanical perturbation of postural control that will invoke a vestibular signal that in the case of a subsequent fall has been a failed attempt to initiate a postural recovery program that is of clinical relevance in PD. However, falls not related to a neurological etiology of falls may be one of the reasons for the lack of association between impaired vestibular efficacy and falls in this study. There may also be recall bias with false negative reporting of falls due to recall bias. However, this would be predicted to dilute rather than strengthen the findings in this study. Nevertheless, a recent prospective 1 year follow-up study found that the presence of neurovestibular dysfunction (as defined by abnormal vestibular evoked myogenic potential, VEMP) may predict the risk of future fall incidents in PD with postural imbalance25. Lastly, it is possible that our study sample size was underpowered to identify a deficient vestibular efficacy-associated component of falls.

Our findings demonstrated that a subset of patients with failure during Romberg condition 4 did not have FoG. The modified Romberg – as specified in our study – may be a good and easy clinical screening test but may have about a 80% diagnostic accuracy to diagnose vestibular deficits18. Therefore, performance of Romberg condition 4 predominantly, but not exclusively, may reflect vestibular efficacy. It could be possible that more stringent cut-off criteria for abnormalcy on the Modified Romberg test, such as a shorter time to fall may result in a more accurate assessment of (significant) vestibular changes but further research is needed. A dynamic visual reading test (i.e., accuracy of reading during head movements) may potentially be another vestibular screening test that may deserve further studies26, 27.

A primary premise of this work is that a loss of balance in Task 4 of the Romberg test (balancing on a compliant surface with eyes closed) reflects “deficient vestibular efficacy”. However, test 4 is very non-specific in terms of potential neuropathology and could include vestibular, proprioceptive or cerebellar deficits. While the Romberg 4 has relatively good sensitivity and specificity when comparing people with vestibular disorders versus matched controls, this test does not discriminate well between pathologies that could lead to a higher incidence of falls. Furthermore, it should be noted that pure isolation of a vestibular component in the modified Romberg test may be an elusive goal as test interpretation then should be based on differences between the different conditions of the Romberg that involve more versus less sensory integration22.

Furthermore, effective postural control will be the end result of multisensory, cognitive and even emotional integration unsuccessful motor programs. The relative selectivity of failing Romberg condition 4 while passing conditions 1–3 is likely the result of limited capacity processing of these heteromodal functions where abnormal vestibular efficacy may be a critical factor imposed on such non-vestibular component that in final common pathway may result in failure of the postural control system. In this respect, our study does not exclude that other sensory, such as proprioceptive, deficits also may play a role in FoG in PD28.

Unlike falls where we previously showed a cholinergic but not a nigrostriatal dopaminergic nerve terminal association, FoG can be dopaminergic medication responsive, at least in early-stage disease. Therefore, possible dopamine medication responsive effects on (multi-sensory integration) in the legs may play a mechanistic role in performance on the modified Romberg test.

Some of the reported falls in this study may have happened during DA medication on state. However, for the type of PD patients who have PIGD motor features (falls, FoG) these are likely also to suffer from motor fluctuations and in the absence of documentation of whether a fall happened in a on versus off state it will be difficult to shed light on this. Furthermore, our prior falls studies found that falls were related to cholinergic hypofunction but not to the degree of nigrostriatal losses29. However, it could be possible that there may be some components of DA-responsive postural control functions that could have resulted in possible disparity of our analysis as the Romberg 4 testing was performed in a DA medication off state.

Our findings may augur novel vestibular treatment approaches to treat FoG in PD. Caloric vestibular stimulation is a widely used technique that is commonly used to diagnose balance disorders or confirm absence of brainstem function. However, caloric stimulation may also have to potential to be used for therapeutic purposes. For example, the modulation of various networks and nuclei in the brain by caloric vestibular stimulation including the basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, insula, hypothalamus, thalamus, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex suggests significant potential for caloric vestibular stimulation to modulate both motor and non-motor functions30. Recent development of portable caloric vestibular stimulation devices has shown promise in treatment of PD. A recent example is the portable self-administered in-home thermoneuromodulation (TNM) approach that was successfully applied in the PD population31. Preliminary findings showed significantly improved motor and non-motor functions in PD in the home situation31, 32. Other methods include traditional vestibular physical therapy or galvanic vestibular stimulation (GVS). For example, a fMRI study found evidence that GVS can enhance deficient PPN connectivity and improve visual-cerebellar sub- network interaction in PD in a stimulus-dependent manner33, 34. This may provide a mechanism through which GVS may improve balance and related risk of FoG in PD.

A limitation of the study was that no objective vestibular testing was performed to confirm that failure during Romberg condition 4 is mainly driven by abnormal vestibular efficacy. Other limitations of the study include the lack of FoG subtyping as distinct subtypes of freezing motor behaviors may differ in pathophysiology mechanisms. Intuitively, vestibular mechanisms may play a more direct role in FoG that are caused by turning-induced events. However, there is also a link between vestibular dysfunction and anxiety implicating that vestibular processing deficits may also play a role in freezing episodes triggered by anxiety spells35. Similarly, vestibular deficits may co-exist with abnormal cognitive functions suggesting that vestibular changes may also play a role in freezing induced by cognitive-motor dual tasking or other conditions with cognitive overload36, 37.

The rationale for this study focused on the fact that FoG occurs frequently during tasks such as turning where dynamic balance is needed, yet the modified Romberg test is performed under a static balance condition. However, it may be difficult to perform a SOT task under walking conditions on compliant surfaces with eyes closed because of safety concerns.

Another limitation of the study is the low frequency of female patients to determine if gender effects may play a role in vestibular deficits in PD. This is of relevance as our study found there is an equal proportion (75.8% males in the deficient and 76.3% males in the non-deficient vestibular efficacy groups) while there is evidence of a higher risk of vestibular dysfunction in women38.

In conclusion, the selective failure during Romberg test condition 4 in patients with PD may contribute to the pathophysiology of FoG in PD independent from clinical confounder variables. Furthermore, we found that absence of condition 4 test failure was associated with a very low frequency of FoG suggesting a specific effect of deficient vestibular efficacy on FoG in PD. Findings may augur vestibular therapy as a novel treatment for FoG in PD. The lack of a specific association between failure during Romberg condition 4 and falls in PD may reflect the more multifactorial and stochastic chance effects of falls in PD or may be due to our limited assessment of fall status in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christine Minderovic and Cyrus Sarosh for their assistance. We are indebted to the subjects who participated in this study.

Funding agencies:

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (R01 AG073100, RO1 NS070856, P50 NS091856, P50 NS123067), Department of Veterans Affairs grant (I01 RX001631), the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and the Parkinson’s Foundation.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Bohnen has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, Parkinson’s Foundation, the Farmer Family Foundation Parkinson’s Research Initiative, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation.

Dr. Kanel has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. van Emde Boas has nothing to disclose.

Mr. Roytman has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Kerber has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs

Footnotes

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: The authors have no relevant financial or conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith PF. Vestibular Functions and Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurol 2018;9:1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Schubert MC, Minor LB. Disorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2004. Arch Intern Med 2009;169(10):938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venhovens J, Meulstee J, Bloem BR, Verhagen WI. Neurovestibular analysis and falls in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Eur J Neurosci 2016;43(12):1636–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Wensen E, van Leeuwen RB, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, Masius-Olthof S, Bloem BR. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19(12):1110–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker-Bense S, Wittmann C, van Wensen E, van Leeuwen RB, Bloem B, Dieterich M. Prevalence of Parkinson symptoms in patients with different peripheral vestibular disorders. J Neurol 2017;264(6):1287–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieuwboer A, Giladi N. Characterizing freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: models of an episodic phenomenon. Mov Disord 2013;28(11):1509–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy PM, Cressman EK, Carlsen AN, Chua R. Assessing vestibular contributions during changes in gait trajectory. Neuroreport 2005;16(10):1097–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huh YE, Hwang S, Kim K, Chung WH, Youn J, Cho JW. Reply to letter: The association of postural sensory deficit with freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;31:141–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55(3):181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(4):695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekkers EMJ, Dijkstra BW, Dockx K, Heremans E, Verschueren SMP, Nieuwboer A. Clinical balance scales indicate worse postural control in people with Parkinson’s disease who exhibit freezing of gait compared to those who do not: A meta-analysis. Gait Posture 2017;56:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekkers EMJ, Dijkstra BW, Heremans E, Verschueren SMP, Bloem BR, Nieuwboer A. Balancing between the two: Are freezing of gait and postural instability in Parkinson’s disease connected? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018;94:113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetz CG, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Process, format, and clinimetric testing plan. Mov Disord 2007;22:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shumway-Cook A, Horak FB. Assessing the influence of sensory interaction of balance. Suggestion from the field. Phys Ther 1986;66(10):1548–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agrawal Y, Davalos-Bichara M, Zuniga MG, Carey JP. Head impulse test abnormalities and influence on gait speed and falls in older individuals. Otol Neurotol 2013;34(9):1729–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen HS, Kimball KT. Usefulness of some current balance tests for identifying individuals with disequilibrium due to vestibular impairments. J Vestib Res 2008;18(5–6):295–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Hoffman HJ, Sklare DA, Schubert MC. The modified Romberg Balance Test: normative data in U.S. adults. Otol Neurotol 2011;32(8):1309–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen H, Blatchly CA, Gombash LL. A study of the clinical test of sensory interaction and balance. Phys Ther 1993;73(6):346–351; discussion 351–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohnen NI, Kanel P, Zhou Z, et al. Cholinergic system changes of falls and freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2019;85(4):538–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohnen NI, Kanel P, Koeppe RA, et al. Regional cerebral cholinergic nerve terminal integrity and cardinal motor features in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Communications 2021;3(2):fcab109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takakusaki K Neurophysiology of gait: from the spinal cord to the frontal lobe. Mov Disord 2013;28(11):1483–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huh YE, Hwang S, Kim K, Chung WH, Youn J, Cho JW. Postural sensory correlates of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;25:72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vervoort G, Nackaerts E, Mohammadi F, et al. Which Aspects of Postural Control Differentiate between Patients with Parkinson’s Disease with and without Freezing of Gait? Parkinsons Dis 2013;2013:971480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sri-on J, Tirrell GP, Lipsitz LA, Liu SW. Is there such a thing as a mechanical fall? Am J Emerg Med 2016;34(3):582–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venhovens J, Meulstee J, Bloem BR, Verhagen WIM. Neurovestibular Dysfunction and Falls in Parkinson’s Disease and Atypical Parkinsonism: A Prospective 1 Year Follow-Up Study. Front Neurol 2020;11:580285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MH, Durnford SJ, Crowley JS, Rupert AH. Visual vestibular interaction in the dynamic visual acuity test during voluntary head rotation. Aviat Space Environ Med 1997;68(2):111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vital D, Hegemann SC, Straumann D, et al. A new dynamic visual acuity test to assess peripheral vestibular function. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;136(7):686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira MP, Gobbi LT, Almeida QJ. Freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: Evidence of sensory rather than attentional mechanisms through muscle vibration. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;29:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohnen NI, Muller ML, Koeppe RA, et al. History of falls in Parkinson disease is associated with reduced cholinergic activity. Neurology 2009;73(20):1670–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black RD, Rogers LL, Ade KK, Nicoletto HA, Adkins HD, Laskowitz DT. Non-Invasive Neuromodulation Using Time-Varying Caloric Vestibular Stimulation. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med 2016;4:2000310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson D, Podlewska A, Banducci SE, et al. Caloric vestibular stimulation for the management of motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2019;65:261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson D, Ade KK, Rogers LL, et al. Preventing Episodic Migraine With Caloric Vestibular Stimulation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Headache 2017;57(7):1065–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai J, Lee S, Ba F, et al. Galvanic Vestibular Stimulation (GVS) Augments Deficient Pedunculopontine Nucleus (PPN) Connectivity in Mild Parkinson’s Disease: fMRI Effects of Different Stimuli. Front Neurosci 2018;12:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu A, Bi H, Li Y, et al. Galvanic Vestibular Stimulation Improves Subnetwork Interactions in Parkinson’s Disease. J Healthc Eng 2021;2021:6632394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martens KAE, Hall JM, Gilat M, Georgiades MJ, Walton CC, Lewis SJG. Anxiety is associated with freezing of gait and attentional set-shifting in Parkinson’s disease: A new perspective for early intervention. Gait Posture 2016;49:431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Factor SA, Scullin MK, Sollinger AB, et al. Freezing of gait subtypes have different cognitive correlates in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20(12):1359–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris R, Smulders K, Peterson DS, et al. Cognitive function in people with and without freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2020;6:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith PF, Agrawal Y, Darlington CL. Sexual dimorphism in vestibular function and dysfunction. J Neurophysiol 2019;121(6):2379–2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]