Abstract

Objective.

The objectives of this scoping review are to examine existing research on the often-secret contracts between tobacco manufacturers and retailers, to identify contract requirements and incentives, and to assess the impact of contracts on the sales and marketing of tobacco products in the retail setting.

Data Sources.

The systematic search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest Political Science Database, Business Source Premier, ProQuest Agricultural & Environmental Science Collection, and Global Health through December 2020.

Study Selection.

We included studies that collected and analyzed empirical data related to tobacco contracts, tobacco manufacturers, and tobacco retailers. Two reviewers independently screened all 2,786 studies’ title and abstract and 65 studies’ full text for inclusion resulting in 27 (0.97%) included studies.

Data Extraction.

Study characteristics, contract prevalence, contract requirements and incentives, and the influence of contracts on the retail environment were extracted from each study.

Data Synthesis.

We created an evidence table and conducted a narrative review of included studies.

Conclusions.

Contracts are prevalent around the world and handsomely incentivize tobacco retailers in exchange for substantial manufacturer control of tobacco product availability, placement, pricing, and promotion in the retail setting. Contracts allow tobacco companies to promote their products and undermine tobacco control efforts in the retail setting through discounted prices, promotions, and highly visible placement of marketing materials and products. Policy recommendations include banning tobacco manufacturer contracts and retailer incentives along with more transparent reporting of contract incentives given to retailers.

Keywords: Advertising and promotion, Tobacco industry, Tobacco industry documents

INTRODUCTION

To assist in reducing the burden of tobacco use, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Article 13 provides guidance for countries to reduce tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.[1] Recommendations include comprehensive bans on tobacco company incentive programs that require prime placement, promotion, discounting, or targeting of tobacco products in retailers. Unfortunately, few countries have banned retailer incentive programs and many countries continue to engage with the tobacco industry.[2] In 2019, British American Tobacco (BAT), which serves over 180 markets globally, strengthened relationships with retailers and distributors with loyalty and incentive programs,[3] Japan Tobacco International (JTI) increased their retail presence in key markets,[4] and the major tobacco manufacturers in the United States (U.S.) spent $7.6 billion U.S. Dollars (USD) on marketing, with most of this spending ($5.7B) allocated to price discounts.[5] Often, underlying the promotion of tobacco products are secretive contractual agreements, “contracts” hereafter, between international tobacco manufacturers and tobacco retailers. Contracts are legally binding agreements that are often part of marketing programs, such as the Retail Leaders Program from Philip Morris, the Retail Partners Marketing Plan Contract (RPMPI) from RJ Reynolds, and the Retail Partnership Plan from ITG Brands. These contracts ensure that tobacco products are heavily marketed in the retail setting through the four “P’s” of commercial product marketing: placement, promotion, price, and product.[6–10] A list of tobacco contract terminology and specific definitions for the 4 “P’s” can be found in Table 1. Through retailer incentives specified by these contracts, manufacturers have been able to promote newly developed, low-cost brands and implement discounts and coupons at retailers to blunt the impact of price increases related to excise taxes.[11,12] Discount and promotion requirements in these contracts have the power to increase the amount of retail marketing and price discounts, which have been linked to impulse tobacco purchases, youth exposure to tobacco marketing, and greater tobacco use.[13] These contracts between manufacturers and retailers are pervasive and long-standing; a 1991 study in New York, U.S., found that two-thirds of retailers participated in some form of contract,[14] and a 2018 study conducted in Scotland, found that all but one of 23 retailers participated.[15] Though common, contracts are often invisible to policymakers and advocates, and regulation is rare. Nevertheless, one of the few such examples is the restriction on incentives from tobacco manufacturers to retailers legislated in Quebec, Canada, in 2015.[16] This restriction, as part of the Tobacco Control Act,[16] prevents manufacturers from providing price-related incentives (e.g., buydowns) to retailers.

Table 1.

Definitions and terminology related tobacco company contracts with retailers.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Buydown | Promotional or time-limited product price reductions (e.g., $1.00 off a pack of Marlboro Cigarettes). With a buydown, the retailer lowers the price of the product by a set amount negotiated with the manufacturer and tracks the number of discounts given, the manufacturer then reimburses the retailer at the end of a set period. Stores without a contract or agreement with manufacturers are unable to provide discounted tobacco products to their consumers |

| Contract | Agreement between tobacco manufacturers and retailers that entails requirements and incentives from manufacturers to retailers (e.g., Philip Morris’s Retail Leaders Program, RJ Reynolds’ Retail Partners Marketing Plan Contract [RPMPI], Brown & Williamson’s Kool Inner City Point-of-Purchase [POP] Program) |

| Incentive | Rewards (e.g., free items, monetary gifts, tickets for events or trips) given to retailers for participating in contracts with tobacco manufacturers and abiding by the requirements stipulated |

| Placement* | The location where a product is positioned for the consumer |

| Price* | The amount that a consumer pays for a product |

| Product* | The specific item or good produced by a manufacturer and obtained by a consumer |

| Promotion* | The advertising efforts used to highlight a product |

| Requirement | Standards (e.g., 30% of shelf space) or actions expected by tobacco manufacturers of retailers who participate in contracts to receive incentives |

| Slotting Fee (Slotting payment, Listing fee) | Payments by tobacco manufacturers to retailers in exchange for guaranteed shelf space for new or existing products |

| Trade promotions | Marketing focused on wholesalers and retailers, instead of focused directly on the consumer through mass media channels |

Placement, price, product, and promotion form the 4 “P’s” of marketing.

Conceptually, contracts are linked to consumer behaviors through modifications to the retail environment and retailer behavior. Prior work shows that contracts often include provisions for slotting fees, buydowns, and trade promotions.[6,7,17]

While contracts have important implications for health and policy, research on contracts is relatively sparse, scattered across disciplines, and has not been the subject of a systematic review to date. We conducted a scoping review[18] to explore the state of the existing research and to understand the provisions between manufacturers and retailers. The objectives of this review are to identify the components of contracts, to determine the extent to which contracts are used, and how they impact the tobacco retail environment. We sought to answer three research questions:

To what extent does the literature report on the percent of retailers that have a contract with tobacco companies?

What are the pricing, marketing, and merchandising practices that tobacco companies require of tobacco retailers?

What is the impact of contracts on tobacco retail outlets in terms of pricing, marketing, and sales?

In addition to answering these questions, we also present contract excerpts and a conceptual model to illustrate the detailed requirements placed on tobacco retailers.

METHODS

This review follows an established scoping review framework[19] and adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).[20] PRISMA-ScR guidelines do not require a risk of bias assessment.[20] Because the main purpose of this scoping review was to identify the breadth of existing literature, rather than draw conclusions from it, we did not assess the quality or risk of bias of the included studies with a tool or checklist. The scoping review protocol is registered at Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RWJ3Q).

Inclusion Criteria

Following the “PCC” mnemonic (population, concept, context),[21] we included studies that examined contracts between manufacturers and retailers (e.g., the Philip Morris Retail Leaders Program) regarding tobacco product placement, promotion, pricing, and/or slotting fees in the retail setting. A priori inclusion criteria required studies to be peer reviewed, report on quantitative or qualitative data, examine tobacco products, assess or take place in the retail setting, analyze the content or impact of contracts between tobacco manufacturers and retailers, and be published in English. There were no limitations placed on publication date or country. Commentaries, narrative reviews, and studies reporting no original data were excluded but tracked to provide context in the discussion.

Search and Screening

While developing inclusion criteria, the research team consulted with a research librarian to create a search string in PubMed/MEDLINE that was then translated to the controlled vocabulary of the other databases used in the search. Keywords included product terms (e.g., “tobacco”), concept terms (e.g., “contract”), and context terms (e.g., “store”).1 Full search details can be found in Supplemental Table 1. The search was last updated in December 2020 in seven databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest Political Science Database, Business Source Premier, ProQuest Agricultural & Environmental Science Collection, and Global Health. After screening the initial search results, we then completed backwards citation searching in each included publication to retrieve any relevant studies missed by the initial search.

Search results were imported to Zotero reference management software (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, Vienna, Virginia, U.S.), deduplicated, then imported to the cloud-based article screening and extraction software, Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia). Once in Covidence, we applied a dual independent screening method where two reviewers (AER and JGLL) independently screened all studies. Following the Institute of Medicine’s Guidelines,[22] we followed a two-step approach by which both reviewers screened the title and abstract in step one, then the full-text in step two. Discrepancies in the screening process were discussed and decided upon by consensus. If consensus was not achieved, a third author (KMR) provided a deciding vote.

Extraction

We developed an initial list of data to extract from each study then, after reviewing the included studies, the list was reviewed, discussed, and confirmed by all authors once consensus was reached. One investigator (AER) extracted information for each study regarding the first author, year of publication, location of study, year(s) of data collection, study purpose, sample description and size, study design and methods, description of the contract or agreement, contract prevalence, contract requirements and incentives, and the contract impact on the retail environment. Two investigators (JGLL, KMR) reviewed, edited, and confirmed the final extraction information.

Data Synthesis

We performed a narrative review of the included studies. We first developed themes from our knowledge of the existing literature (e.g., contract prevalence, incentives, requirements), which guided our research questions and data synthesis. We categorized extracted data from each included study into these themes then synthesized the information. Due to the large number of qualitative studies and methodological heterogeneity, particularly in the study samples (e.g., retail store managers, industry insiders, documents, store audits), we decided against performing any quantitative synthesis like meta-analysis.

RESULTS

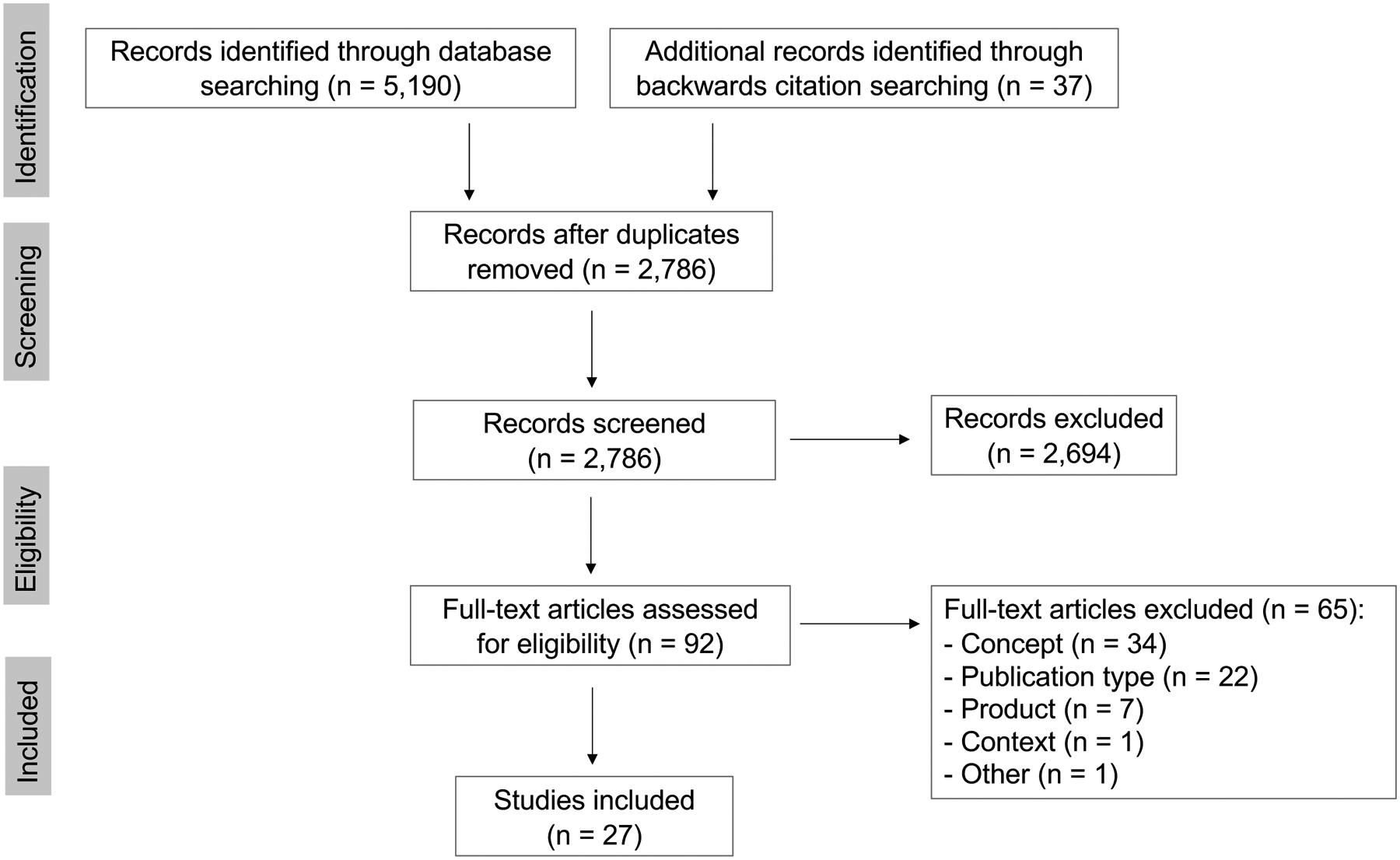

We reviewed 2,786 studies then excluded 2,694 during title and abstract screening and 65 during full-text screening. This resulted in a final sample of 27 studies. Figure 1 shows the search and screening process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR Diagram of Identified Tobacco Contracts Studies.

Study characteristics and methodology are presented below, followed by a synthesis of findings under each theme: contract description, prevalence, incentives, requirements, and impact on the retail environment. Extracted data from each study can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Study Characteristics and Methodology

Seventeen studies were conducted in the U.S.,[6,14,17,23–36] three in Australia,[37–39] two in the United Kingdom (UK),[8,15] two in South Korea,[7,40] and one each in Canada,[41] New Zealand,[42] and Indonesia.[43] The earliest was published in 1991[14] and the most recent were published in 2020.[17,25,38,39] Other than one study conducted in Australia in 2003,[37] the 12 studies published before 2010 were all conducted in the U.S. (Supplemental Figure 1). No included papers explicitly examined manufacturers use of contracts in economies where cigarettes are more likely to be purchased in the “informal” economy. Of the 27 included studies, 23 (85%) used a cross-sectional design, two reported data from two time points,[15,31] and one reported longitudinal data.[43]

Contract Prevalence and Description

A significant proportion of retailers participate in tobacco contract programs, assessed by interviewing samples of tobacco retailers. Sixteen studies reported contract prevalence which ranged from 0–100%. Of these 16 studies, 12 (75%) found that more than half of the retailers surveyed participated in contracts with tobacco manufacturers. Of the four studies that reported a contract prevalence below 50%, one collected data in the U.S. between 1996–1997[35], two collected data in 2017 (one in Canada[41] and one in the U.S.[27]), and one collected data in Australia in 2018[38].

The most common way to describe contracts was to refer to an existing contractual program (e.g., the Philip Morris Retail Leaders Program) or use the terms “incentive program” or “retailer program”. Studies also used the terms “contract”, “agreement”, “partnership”, or unique definitions specific to a study.

Incentives, Requirements, and Impact on the Retail Environment

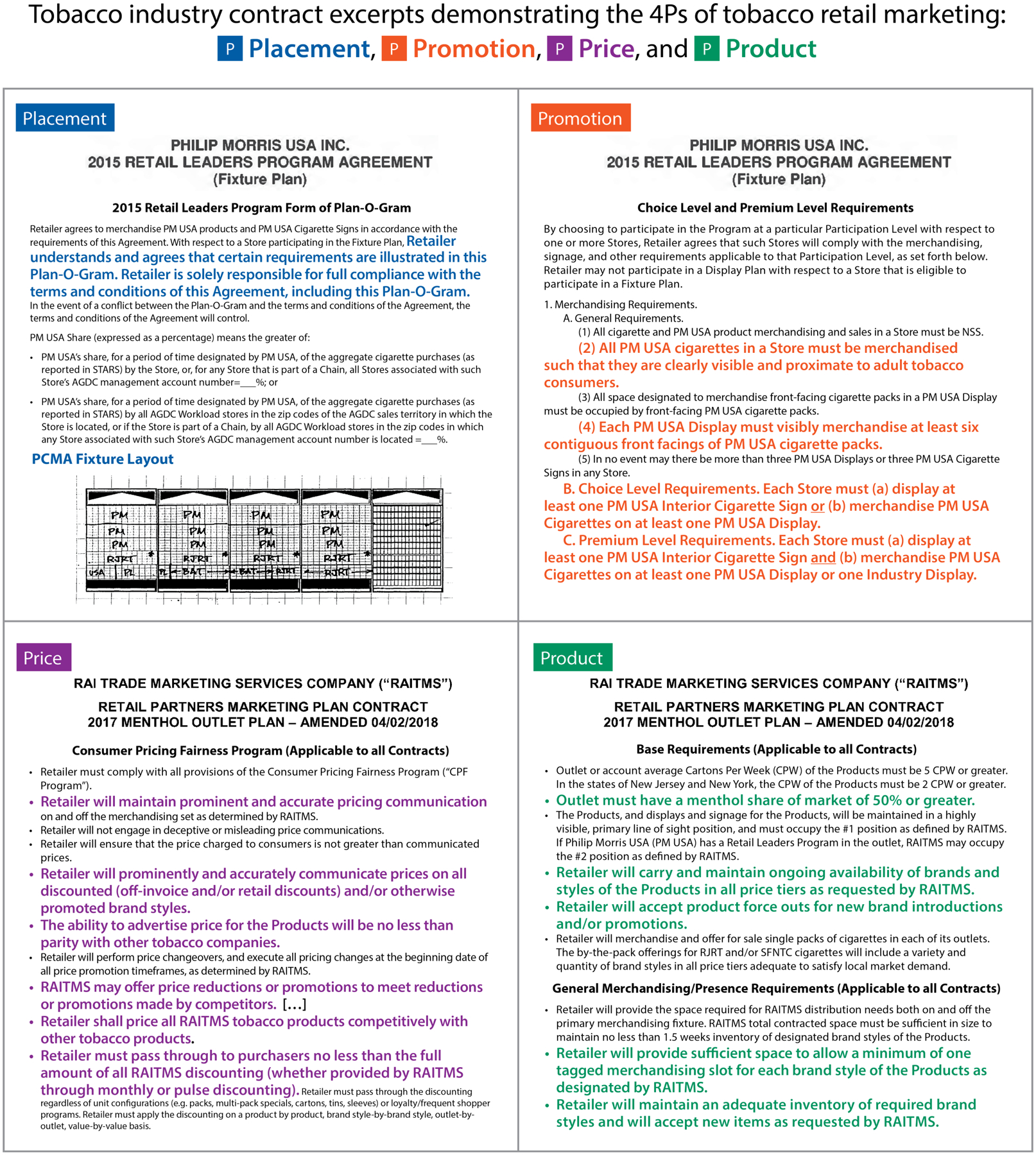

Of the 27 studies included, 26 reported requirements expected of and incentives given to retailers. We report the requirements and incentives associated with these contracts using the four P’s: placement, promotion, price, and product. Examples from real-world contracts between manufacturers and retailers were made public as part of U.S. Department of Justice litigation initiated in 1999, U.S. v. Philips. See Figure 2 and three full contracts (Contract 1 – Philip Morris USA Inc., 2015 Retail Leaders Program Agreement; Contract 2 – ITG Brands Retail Partnership Plan Description; Contract 3 – RAI Trade Marketing Services Company (“RAITMS”) Retail Partners Marketing Plan Contract, 2017 Menthol Outlet Plan) found on Open Science Framework online (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/C3Z4G).

Figure 2.

Examples of the 4 “P’s” in contracts between manufacturers and retailers.

- Excerpts are exact quotes from two tobacco contracts, RAITMS’s Retail Partners Marketing Plan Contract and Philip Morris USA’s Retail Leaders Program Agreement.

- The plan-o-gram in the Philip Morris, 2015 Retail Leaders Program Agreement was blank and thus replaced with a completed RJ Reynolds plan-o-gram from 2002.

Placement.

The most reported requirements described how tobacco products and advertising must be displayed in the store.[6,7,14,15,17,23–26,28,29,32,34–40,42,43] For example, one retailer interviewed in the UK reported reserving two-thirds of their tobacco unit space for a contracted manufacturer[15] and another in the U.S. recounted that manufacturer representatives required 45% of the tobacco retail space to be dedicated to that particular manufacturer.[29] Studies also reported that representatives regularly visited retailers and, to varying degrees, had control over the store design, layout, and placement of tobacco products and advertisements.[6,8,15,17,24,27,32,37,40] Slotting fees (i.e., payments from the manufacturer to the retailer in exchange for shelf space) were also commonly reported as an incentive in different contracts,[7] particularly in the U.S.[6,17,24,28] The value of this incentive type varied and was reported to exceed the equivalent of thousands of USD by a study in South Korea.[7] The Philip Morris 2015 Retailer Leaders Program Agreement specifically stipulates that the plan-o-gram layout of the store indicating exactly where both products and advertisements must go, must be followed. In addition to the plan-o-gram, the manufacturer specifies that Philip Morris products must be clearly visible and close to potential customers, at the top of display cases, and can occupy up to 65% of the display space (Figure 2).

Promotion.

Studies found that, due to their contracts, stores were required to promote products and maintain certain sales volumes to maintain their payments.[6,23,26,29,32] One retailer in the U.S. reported that, “10–15% of your contract depends on performance and 10–15% depends on your volume of sales,”[32] while another study in the U.S. described a specific contract in which retailers were required to sell at least 100 cartons of industry brands and 17 cartons of RJ Reynolds brands per week to qualify for incentives.[6] Complementing required sales volumes, multiple studies also reported volume discounts (i.e., receiving discounts on tobacco products from tobacco manufacturers for purchasing a large volume).[24,25,27,29,32,39] An ex-tobacco manufacturer representative in Australia described this as giving larger rebates to retailers for every 1,000 “cigarette sticks” they sold.[39]

To assist in promoting large quantities of product, starting in 2018, studies reported that manufacturer representatives encouraged verbal promotion of products.[15,17,39] For example, retailers from one study in the UK were expected to promote a particular product to customers for a set period of time. If a mystery shopper asked for a different brand and the retailer suggested a switch to the manufacturer-specified product, that retailer would receive a £100 (≈$136 USD) bonus to their contract incentives.[15] The most commonly reported contract incentives were free and discounted tobacco products, advertising materials, gifts, or other items given to retailers to keep, give, or sell to customers.[6–8,15,17,24,28,29,31,33,35–40,43] Often, this included display cases, free samples of new products, promotional signs, and small gifts such as lighters. A retailer from one study in South Korea indicated that, “As soon as [they] sign a contract with headquarters, the tobacco company employees come in and place the advertising and check its placement or change their product displays.”[40] Sections of the Philip Morris 2015 Retailer Leaders Program Agreement echo similar requirements such that retailers must ensure tobacco products are visible, display tobacco signage, and utilize branded displays (Figure 2).

The most commonly reported impact of contracts on the retail environment was an increase in product availability, tobacco displays, and point-of-sale promotion.[6–8,14,15,17,23– 29,31,34,36,43] According to the retailers interviewed in one U.S. study, retailers with contracts have more signs, displays, and products on sale.[29] Another study in the U.S. found that retailers with contracts had more than twice as many marketing materials than stores without contracts.[23]

Studies from the U.S. and Australia found that contracts not only impacted tobacco products and promotion, they also had bleed-over effects, impacting other products and forms of advertising.[14,26,34,37] One of these studies reported that a tobacco manufacturer created a delivery hub for shipments of tobacco products along with other unhealthy products like sweets and convenience foods. This solidified a relationship between the tobacco manufacturer and retailers for inventory, while pairing the purchase and distribution of tobacco and unhealthy convenience foods.[37] Individual contracts with food and beverage companies exist alongside tobacco contracts, however, more retailers reported receiving incentives from tobacco manufacturers than food and beverage manufacturers. Retailers also reported that contractual agreements with food and beverage companies lasted for shorter periods of time and specified smaller requirements and incentivizes.[28] One retailer in South Korea stated, “There are not as many other products [compared to tobacco] that steadily advertise at convenience stores. When a beverage or a candy company introduces a new product…this lasts for only a month.”[40] Two studies in the U.S. also found that contracts may undermine tobacco control efforts. Retailers with contracts were less willing to display anti-tobacco signs in their stores.[14,26]

Price.

Contracts also specify the prices at which tobacco products can be sold.[6,17,23–25,29] For example, one study in the U.S. reported that 77% of retailers were required to price tobacco products according to manufacturer or representative directions.[17] Studies consistently reported buydowns (i.e., promotional or time-limited product price reductions),[17,24,25,27,29,30,32,33,37] as part of their contract. Between 1999 and 2020, studies reported that retailers with contracts offered lower prices for their tobacco products in the U.S., Canada, and Australia.[17,23–25,29–31,37,41] One study in Canada found price differentiation for retailers with contracts, even after the local government banned contractual incentives from manufacturers to retailers.[41] Lower prices were especially apparent for those tobacco retailers at the border of high-tax jurisdictions. One study in the U.S. reported “niche” contracts offered to retailers at the border of high-tax jurisdictions that included large buydowns ranging from $1 to $3 and price promotions associated with volume discounts.[25] Pricing is often stipulated in contracts, instances of which can be found in each of the three contracts mentioned above. For example, the RAITMS 2017 Menthol Outlet Plan states that retailers must prominently display the pricing of RAITMS brand tobacco products, must price them competitively, and must pass the full amount of any discount directly to the customer (Figure 2).

Product.

Five studies in the U.S. and South Korea found that the promotional materials and products manufacturers sent to retailers targeted demographics of the area.[7,17,32,36,40] Two studies in the U.S. reported that contracts purposefully promoted menthol tobacco products in neighborhoods with large Black populations, one of which discussed a specifically tailored contract, Brown & Williamson’s Kool Inner City Point-of-Purchase (POP) Program, aimed at increasing the visibility and promotion of menthol products in predominantly Black neighborhoods in inner city urban cores.[17,36] The results of these studies mirror the RAITMS 2017 Menthol Outlet Plan which specifies that retailers must have a 50% or greater menthol share of the market and are required to keep products and displays in highly visible locations (Figure 2).

Additional studies reported manufacturers targeting products towards varying populations. Retailers from one study in South Korea identified different promotional and advertising techniques used by manufacturers based, “on the characteristics of the district,”[40] while another study in the U.S. found that stores in areas with large racial/ethnic populations, low education, and low income had more in-store advertising for tobacco products than their counterparts.[32] A study analyzing tobacco industry documents in South Korea found that manufacturers identified young adult males, individuals who recently started smoking, and females as potential targets and opportunities for market growth due to changing cultural norms among young individuals, lack of commitment to a specific brand, and the low smoking prevalence among women.[7]

Miscellaneous and Generous Incentives.

Contracts also commonly incentivize retailers with monetary rewards or vouchers.[6,8,14,15,17,23,24,33,35–37,39,40,42,43] The reported cash equivalence for retailer incentives varied greatly between $20/month in urban U.S. cities in 1991 [36] and $20,000/year reported in 2001 in the U.S.,[24] with one study reporting the median incentive value at $930/year in the U.S. between 2013 and 2014.[17] Contractual relationships also provided retailers with professional support or education from manufacturers in the U.S. and Australia.[34,37,39] This included one-on-one meetings, help with designing and merchandising new stores, and off-site events to educate the retailers on new products available and how to best promote them. Generous incentives were given to well-preforming retailers in the UK, Australia, and the U.S.[8,36,39] These included tickets for sports, music, and movie events, lavish parties in which tobacco products were promoted and gifted to guests and staff, and once-in-a-lifetime experiences such as paddle boarding around glaciers, driving Lamborghinis and Ferraris, traveling to Fiji on all-expenses paid trips to view tobacco growing and manufacturing, and sweepstakes to win a Cadillac.

Manufacturer Control and Retailer Compliance.

Three-quarters of the retailers interviewed in one U.S study reported that manufacturers were in complete control of their tobacco displays and promotional materials.[17] A retailer in another U.S. study described the interaction with a manufacturer representative, reporting, “it’s almost like it’s not my store… I was overwhelmed, she [the representative] walks in one day and throws some books on my counter and tells me, ‘I’ll tell you what you are going to do.”[32]

According to an interview in one U.S. study, most retailers participate in multiple incentive programs.[29] In multiple studies, contracts were viewed as necessary evils for U.S. retailers to stay in business,[34] with one retailer reporting, “We don’t make a lot of money on cigarettes but we make a lot of money on displays.”[17] For this reason, retailers upheld contracts even though they were controlling and demanding.[17,26,32,34] “They’re trying to control my business,” a retailer reported in one study,[17] and, “It’s not an offer, it’s a mandatory thing. It has to be the way they want it,” reported another.[32]

Compliance with controlling and demanding aspects of contracts appeared to be enforced. “You don’t want to violate the contract, ” a retailer reported in one U.S. study.[26] During visits, tobacco manufacturer representatives assessed the fulfillment of contract requirements (e.g., product and advertisement placement). These visits were often unannounced, sometimes included the use of a mystery shopper, and described as “bullish and intimidating” by a UK retailer.[8] If the retailer was out of compliance, this resulted in loss of incentives. One study found that after tobacco sales volume decreased, representatives discontinued their visits and manufacturers did not renew their contracts, ending incentives altogether.[27] However, another study found that retailers sanctioned by manufacturers for violating their contracts by selling tobacco to minors did not lose their incentives as their contract specified they would. These retailers continued to receive special price offers and promotional materials.[31]

After receiving extensive incentives, retailers from around the world were described as vocal allies for tobacco manufacturers.[7,15,17,24,37,39] For example, one study discussed that large incentives associated with contracts may lead retailers to lobby for pro-tobacco policy.[24] Interestingly, interviews and industry documents from manufacturer representatives highlighted an unexpected, perceived power dynamic, that did not match findings from studies with retailers: Representatives portrayed retailers as holding power over manufacturers, withholding display space, and demanding larger financial incentives.[6,37,39] They used language that described retailer incentives as manufacturer requirements with one representative in Australia reporting, “if we weren’t giving [a retailer] a competitive offer, then they would remove most of our slots”[39] and an industry document also from Australia stating, “retailers immediately realized they were sitting on a „gold mine’ at retail when print…went away.”[37] However, that depicted power dynamic does not represent the typical manufacturer-retailer relationship. Large chain retailers may stake claim over how their shelves are stocked, but manufacturers can, “generally get away with paying [mom and pop shops] $100, $200 for 100% of their price board, which would maintain it from anywhere from 6 to 12 months.”[39]

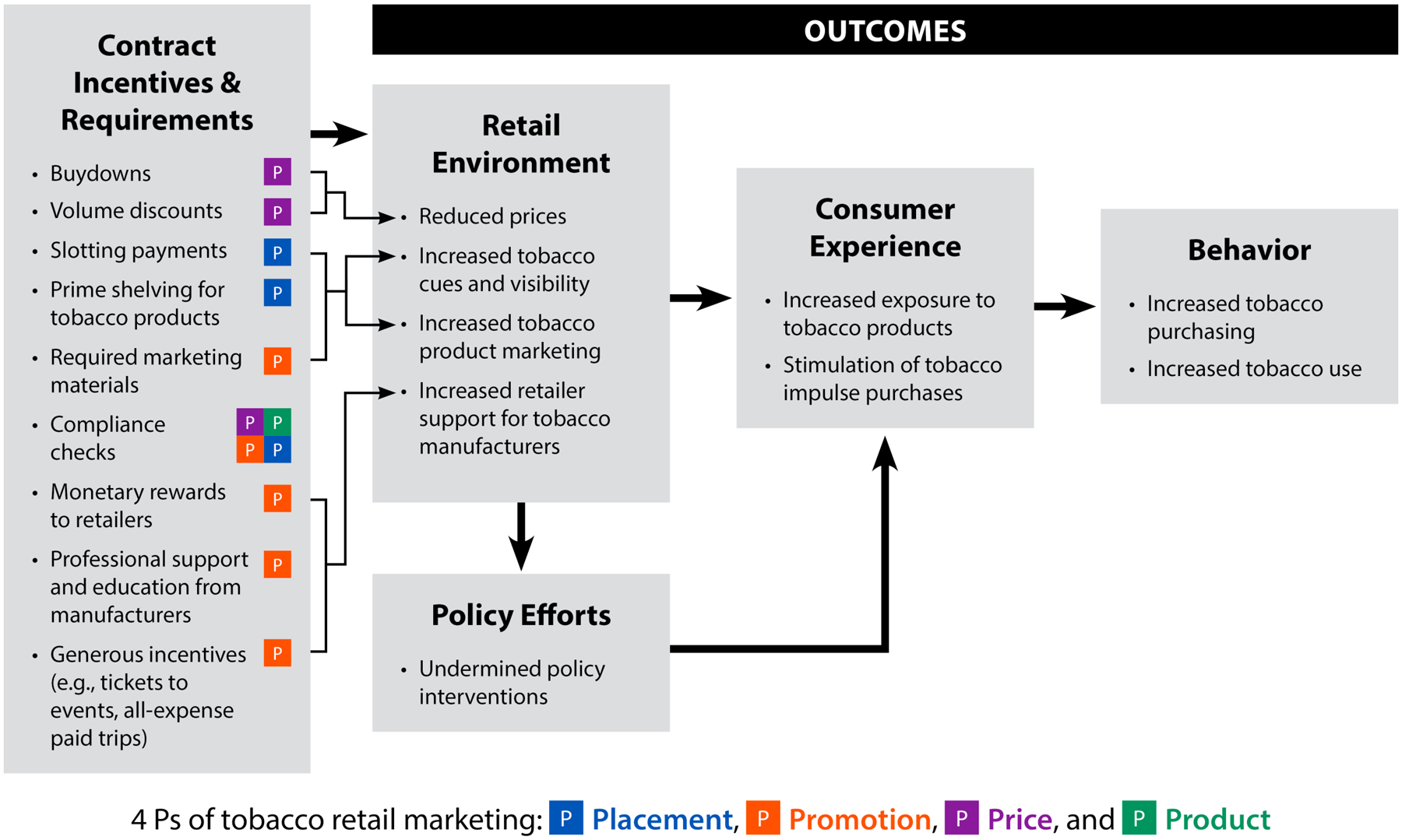

Conceptual Model

The conceptual model (Figure 3) depicts how tobacco company contract components impact the retail environment in ways that may increase tobacco purchases and use. Buydowns and volume discounts facilitate tobacco price reduction[17,29] while slotting fees, product placement, and promotion increases tobacco product visibility and marketing.[23–25] Marketing can either aggressively “push” (i.e., promote a product with trade marketing in the retail environment) or more naturally “pull” (i.e., highlight the positive features of a product, like in magazine, online, and billboard advertisements, to create demand and motivate intent to purchase). This model highlights the tobacco industry’s current preference for “push” marketing, the form of marketing that is both more effective and more intrusive.[24,44] Retailer incentives, a large component of contracts, increase retailer support for manufacturers and reinforce retailer participation in contract programs.[15,24,39] Moreover, this retailer support eventually undermines tobacco control policy efforts as retailers promote tobacco products and alert manufacturers to upcoming tobacco policy.[45,46] Altogether, these produce changes in the retail environment, making it more likely to promote tobacco use and purchasing. This type of retail environment has the power to alter the consumer experience and to thus increase tobacco purchasing and tobacco use.[13]

Figure 3.

Conceptual model visualizing the impact of contact incentive requirements and incentives on the retail environment, consumer experience, and behavior.

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

Regarding our research questions, this review on the often-secret agreements between tobacco manufacturers and retailers found that these contracts:

are common, with the majority of studies identifying contracts in more than half of the retailers sampled;

provide retailers with generous incentives, require strict retailer compliance, utilize buydowns and discounts to lower tobacco product prices, require retailers to display interior and exterior store signage and other marketing materials while also encouraging retailers to verbally promote products, and provide slotting payments that reserve large swaths of highly visible retail space;

decrease tobacco product prices, increase product marketing and merchandising, and make the retail environment more conducive to tobacco use and initiation.

These contracts essentially give tobacco manufacturers substantial control of some of the most desirable real estate in the retail outlet, creating a pathway by which manufacturers can work through the retailer to push and promote their tobacco products to consumers. This relationship and the resulting impact on the tobacco retail environment threatens tobacco endgame efforts.

Though the number of contracts ranged widely, the majority of studies reported a high prevalence. The wide variation is likely due to the differing tobacco retail and policy environments across the range of years and locations included in this review. The Philip Morris Retail Leaders Program officially launched in 1998 as one of the first contract incentive programs.[47] The low prevalence of tobacco contracts found in the 1990s in the U.S. may portray the early emergence of this type of relationship between the tobacco industry and retailers. The low contract prevalence reported in more recent studies in Canada, Australia, and the U.S. conducted in 2017 and 2018 may reflect successful policies in the current policy environment. Quebec, Canada, banned this incentive relationship,[41] Australia banned identifiable tobacco packaging and almost all advertising efforts,[48] and San Francisco, U.S., banned tobacco advertising on public billboards and retail signs that can be viewed from the outside of stores.[49]

The vast majority of studies in this review before 2010 were conducted in the U.S. This most likely reflects 1) a lack of comprehensive tobacco policy and regulation, and 2) the global market in which companies, including Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds, may have begun to implement contracts with retailers in the U.S. then expanded them into markets around the world. Our findings also indicate that slotting fees are most common in studies from the U.S., and it is important for policymakers to understand the influence of contracts on the environment experienced by consumers.

Manufacturer and retailer contracts appear to dictate almost every aspect of tobacco product pricing, marketing, and merchandising. Manufacturers appear to micromanage the retail environment through contracts and, as the identified studies show, retailers often have little control over their store regarding tobacco products and marketing. Prior research consistently indicates that tobacco marketing is associated with tobacco use and initiation.[50–52] Thus, we assert that these contracts undermine tobacco control efforts and play a role in consumer purchasing and use of tobacco products.

In return for the extensive requirements associated with these contracts, retailers are often rewarded with incentives ranging from small monetary incentives to lavish rewards. Once retailers receive these incentives and begin to depend on them, they develop allegiance and loyalty to tobacco brands and products. Retailer loyalty to manufacturers undermines tobacco control efforts. Tobacco industry documents indicate that loyal retailers often act as a detection system for local tobacco control efforts, giving tobacco manufacturers early indication of possible legal battles for them to defeat before efforts are passed into law.[45,46]

According to research published after our search, some contracts are specific to certain products (i.e., smokeless tobacco),[53,54] are publicly acknowledged, and utilize mobile technology to promote brand loyalty.[55] Rather than kept secret, one study found that some retailers in Indonesia advertised their participation in retailer incentive programs.[55]

Results in Context

Our findings are similar to those in the Deadly Alliance Report[56] which investigated the relationship between manufacturers and retailers, finding that the two work together to undermine tobacco control policy efforts. Contracts may also undermine equity by targeting systematically marginalized populations and neighborhoods with menthol advertising and products,[17,36] as recent research finds that neighborhoods with predominantly Black populations have greater odds of having menthol availability and price promotions than predominantly Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White neighborhoods.[57]

Policy Implications

Specific policy options to address contracts include banning them outright (i.e., the Quebec, Canada, policy banning incentive programs[16]), banning buydowns,[58] implementing counter-advertising alongside buydowns,[58] using clear language that bans “advertising” rather than “promotion,” [58] banning all business-to-business and business-to-consumer advertising to undercut the loophole allowing wholesale advertising that many manufacturers take advantage of, and requiring all payments from manufacturers to retailers be made publicly available (e.g., sunshine laws in the U.S. that shed light on government and corporate operations).[58–60] One study in our review assessed the incentive program ban in Quebec[41] but found no effects of the ban on tobacco pricing a year after enactment. This may indicate that contract bans are not effective enough on their own and require supplemental policy, that compliance and enforcement were inadequate, or that further research is needed to assess additional aspects of this type of ban on the tobacco retail environment.

Like manufacturers, some governments can also enter into contracts with retailers. A small body of literature assesses the effectiveness of Assurances of Voluntary Compliance (AVCs), which are agreements between corporate retailers and state attorneys general in the U.S. AVCs act as a legal contract between two parties and can include provisions to reduce exposure to marketing. These agreements are not subject to the same First Amendment protections that preclude many efforts to regulate tobacco marketing in the U.S. Research indicates that AVCs may successfully reduce access to tobacco products and advertising but must be thoroughly enforced to be effective.[61–63] AVC’s may be an effective option for countries operating under a free market or those with a time-consuming policy-making process.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future research should analyze how contract prevalence and policy responses vary globally, with a particular focus on low and middle income countries (LMIC) with informal economies. This line of research should assess existing global policies, including contract bans, in relation to contract prevalence to identify effective tobacco-control policy. Future work should also consider policy interventions that disrupt the relationship between tobacco manufacturers and retailers, strengthen tobacco-control laws to ban contracts and retail displays, assess the role of public health contracts (Assurances of Voluntary Compliance) to further the goal of a tobacco endgame. Future research is also needed to further understand the relationship between contracts, area-level socio-demographic variables, and menthol availability and promotion. This review largely includes cross-sectional, observational studies. We identify the need for longitudinal designs to improve causal inference.

Strengths and Limitations

Our review highlights a long-standing worldwide issue that has gone without major global recognition for decades. The scope of our review covers 30 years, 4 continents, and identifies a burgeoning line of research recognized globally in only the last decade. However, because this review is the first of its kind, and we wanted to understand the scope of reliable research on the topic, we only included peer-reviewed literature. Though this means our methods are easily replicable, it also means we may have excluded applicable studies that have not undergone the peer-review process. Although our inclusion criteria were limited to articles in English, we are not aware of any studies published in other languages; however, we did not search using non-English keywords. Additionally, there was heterogeneity among the retailer sampling methods and results so we are unable to conclude, definitively, the actual prevalence of tobacco contracts around the world. This may reflect true variation in prevalence across varying locations. Our findings are limited by what is reported in the literature, the sampling methods used, and how researchers chose to design, collect, and present their studies. This review should be used to draw preliminary, rather than definitive, conclusions about the existing literature and trends in tobacco manufacturer contracts.

Conclusions

Often-secretive contracts change the retailer environment in ways that influence consumer behavior. In many retail spaces across the globe, the products available, pricing, and advertising present – and even interactions with store clerks – are influenced by contracts that are invisible to consumers. According to our results, such contracts are pervasive globally, highlighting the incongruency between FCTC recommendations[1] and reality. Addressing contracts should be a public health priority to decrease tobacco promotion and improve public health.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

Tobacco product manufacturers utilize incentives and requirements stipulated in contractual agreements with tobacco retailers to promote and advertise tobacco products.

To our knowledge, no review of the literature on contracts between tobacco manufacturers and tobacco retailers exists.

Our scoping review includes 27 studies and concludes that contracts are common among tobacco retailers, manufacturers provide retailers with generous incentives to promote tobacco products, provide prime placement, and contracts decrease tobacco prices and increase marketing.

Policy options include banning contracts and requiring payments from manufacturers to retailers be made publicly available.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Emily Jones for consultation while developing our search strategy and throughout this research. We thank Laura Brossart and Todd Combs for their graphic design expertise and assistance.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P01CA225597. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

JGL Lee and KM Ribisl hold a royalty interest in tobacco retailer mapping system owned and licensed by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The software was not used in this research. KM Ribisl is a paid expert consultant in litigation against tobacco companies.

Full search string for PubMed: (tobacco[tiab] OR cigarette*[tiab] OR “tobacco products”[MeSH]) AND (contracts[tiab] OR contract[tiab] OR agreements[tiab] OR agreement[tiab] OR advertising[tiab] OR advertisement[tiab] OR advertisements[tiab] OR marketing[tiab] OR “Tobacco Industry”[MeSH]) AND (store[tiab] OR stores[tiab] OR “point of sale”[tiab] OR “points of sale”[tiab] OR retail[tiab] OR retailers[tiab] OR retailer[tiab] OR retailing[tiab] OR shop[tiab] OR “gas station”[tiab] OR “gas stations”[tiab] OR “point of purchase”[tiab] OR “points of purchase”[tiab] OR outlet[tiab] OR outlets[tiab] OR “milk bars”[tiab] OR newsstands[tiab] OR kiosk[tiab] OR petrol[tiab] OR garage[tiab] OR garages[tiab] OR “service station”[tiab] OR “service stations”[tiab] OR pharmacy[tiab] OR pharmacies[tiab] OR druggist[tiab] OR druggists[tiab] OR supermarket[tiab] OR supermarkets[tiab] OR grocers[tiab] OR groceries[tiab] OR hypermarket[tiab] OR hypermarkets[tiab] OR vendor[tiab] OR vendors[tiab] OR vending[tiab])

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of Article 13 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship). Geneva, Switzerland: : World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_13.pdf (accessed 11 Nov 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assunta M Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2021. Bangkok, Thailand: : Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control (GGTC) 2021. https://exposetobacco.org/wp-content/uploads/GlobalTIIIndex2021.pdf (accessed 27 Nov 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.British American Tobacco. BAT Annual Report and Form 20-F 2019. 2019. https://www.bat.com/ar/2019/pdf/BAT_Annual_Report_and_Form_20-F_2019.pdf (accessed 11 Nov 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Japan Tobacco International. Japan Tobacco Inc. Integrated Report 2019. Japan Tobacco International 2019. https://www.jti.com/sites/default/files/global-files/documents/jti-annual-reports/integrated-report-2019v.pdf (accessed 11 Nov 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2019. Federal Trade Commission 2021. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2019-smokeless-tobacco-report-2019/cigarette_report_for_2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavack AM, Toth G. Tobacco point-of-purchase promotion: examining tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2006;15:377–84. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Lee K, Holden C. Creating demand for foreign brands in a „home run’ market: tobacco company tactics in South Korea following market liberalisation. Tob Control 2014;23:e8–e8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooke C, Cheeseman H, Dockrell M, et al. Tobacco point-of-sale displays in England: a snapshot survey of current practices. Tob Control 2010;19:279–84. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yudelson J Adapting Mccarthy’s Four P’s for the Twenty-First Century. J Mark Educ 1999;21:60–7. doi: 10.1177/0273475399211008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy EJ. Basic marketing, a managerial approach. Homewood, Ill.: : R.D. Irwin; 1960. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006071661 (accessed 18 Aug 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley CP, et al. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control 2002;11:i62–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce JP, Gilmer TP, Lee L, et al. Tobacco industry price-subsidizing promotions may overcome the downward pressure of higher prices on initiation of regular smoking. Health Econ 2005;14:1061–71. doi: 10.1002/hec.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, et al. A Systematic Review on the Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Promotion on Smoking. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:2–17. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings KM, Sciandra R, Lawrence J. Tobacco advertising in retail stores. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974 1991;106:570–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stead M, Eadie D, Purves RI, et al. Tobacco companies’ use of retailer incentives after a ban on point-of-sale tobacco displays in Scotland. Tob Control 2018;27:414–9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Government of Quebec. Tobacco Control Act. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cs/l-6.2 (accessed 18 May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Angelo H, Ayala GX, Gittelsohn J, et al. An Analysis of Small Retailers’ Relationships with Tobacco Companies in 4 US Cities. Tob Regul Sci 2020;6:3–14. doi: 10.18001/TRS.6.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. doi: 10.46658/JBIMES-20-12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington (DC): : National Academies Press (US) 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209518/ (accessed 23 Mar 2021). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Schleicher NC, et al. Retailer participation in cigarette company incentive programs is related to increased levels of cigarette advertising and cheaper cigarette prices in stores. Prev Med 2004;38:876–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloom PN. Role of slotting fees and trade promotions in shaping how tobacco is marketed in retail stores. Tob Control 2001;10:340–4. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apollonio DE, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Promotions and Pricing After Tax Increases: An Analysis of Internal Industry Documents. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob 2020;22:967–74. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan A, Douglas MR, Ling PM. Oklahoma Retailers’ Perspectives on Mutual Benefit Exchange to Limit Point-of-Sale Tobacco Advertisements. Health Promot Pract 2015;16:699–706. doi: 10.1177/1524839915577082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavez G, Minkler M, McDaniel PA, et al. Retailers’ perspectives on selling tobacco in a low-income San Francisco neighbourhood after California’s $2 tobacco tax increase. Tob Control 2019;28:657–62. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Achabal DD, et al. Retail trade incentives: how tobacco industry practices compare with those of other industries. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1564–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.10.1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Clark PI, et al. How tobacco companies ensure prime placement of their advertising and products in stores: interviews with retailers about tobacco company incentive programmes. Tob Control 2003;12:184–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Schleicher NC, et al. How do minimum cigarette price laws affect cigarette prices at the retail level? Tob Control 2005;14:80–5. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Ribisl KM, et al. An examination of the effect on cigarette prices and promotions of Philip Morris USA penalties to stores that sell cigarettes to minors. Tob Control 2009;18:502–4. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.John R, Cheney MK, Azad MR. Point-of-Sale Marketing of Tobacco Products: Taking Advantage of the Socially Disadvantaged? J Health Care Poor Underserved 2009;20:489–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee RE, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, et al. The relation between community bans of self-service tobacco displays and store environment and between tobacco accessibility and merchant incentives. Am J Public Health 2001;91:2019–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinard CA, Fricke HE, Smith TM, et al. The Future of the Small Rural Grocery Store: A Qualitative Exploration. Am J Health Behav 2016;40:749–60. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.40.6.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinbaum Z, Quinn V, Rogers T, et al. Store tobacco policies: a survey of store managers, California, 1996–1997. Tob Control 1999;8:306–10. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yerger VB, Przewoznik Jennifer, Malone RE. Racialized Geography, Corporate Activity, and Health Disparities: Tobacco Industry Targeting of Inner Cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2007;18:10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter SM. New frontier, new power: the retail environment in Australia’s dark market. Tob Control 2003;12:95iii–101. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_3.iii95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watts C, Burton S, Freeman B, et al. „Friends with benefits’: how tobacco companies influence sales through the provision of incentives and benefits to retailers. Tob Control 2020;:tobaccocontrol-2019–055383. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watts C, Burton S, Freeman B. “The last line of marketing”: Covert tobacco marketing tactics as revealed by former tobacco industry employees. Glob Public Health 2020;:1–14. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1824005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hwang J, Oh Y, Yang Y, et al. Tobacco company strategies for maintaining cigarette advertisements and displays in retail chain stores: In-depth interviews with Korean convenience store owners. Tob Induc Dis 2018;16:46. doi: 10.18332/tid/94829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Callard CD, Collishaw N. Cigarette pricing 1 year after new restrictions on tobacco industry retailer programmes in Quebec, Canada. Tob Control 2019;28:562–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson L, Marsh L, Hoek J, et al. Regulating the sale of tobacco in New Zealand: A qualitative analysis of retailers’ views and implications for advocacy. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26:1222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welker M The architecture of cigarette circulation: marketing work on Indonesia’s retail infrastructure. J R Anthropol Inst 2018;24:669–91. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.12911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unni R, Harmon R. Perceived Effectiveness of Push vs. Pull Mobile Location Based Advertising. J Interact Advert 2007;7:28–40. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2007.10722129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landman A, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Youth Smoking Prevention Programs: Protecting the Industry and Hurting Tobacco Control. Am J Public Health 2002;92:917–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saloojee Y, Dagli E. Tobacco industry tactics for resisting public policy on health. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:902–10. doi: 10.1590/S0042-96862000000700007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2000 PHILIP MORRIS COMPANIES INC. WASHINGTON, D.C.: : SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION; 2000. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/764180/000095011701000619/0000950117-01-000619-0001.txt (accessed 30 Nov 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Australia Details | Tobacco Control Laws. https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/australia/summary (accessed 30 Nov 2021).

- 49.TOBACCO ADVERTISING AND PROMOTION PROHIBITED. 2004. https://sanfranciscotobaccofreeproject.org/wp-content/uploads/SF-Police-Code-Article-10-Sec-674-2004.pdf (accessed 30 Nov 2021).

- 50.Biener L, Siegel M. Tobacco marketing and adolescent smoking: more support for a causal inference. Am J Public Health 2000;90:407–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pierce JP. Tobacco Industry Marketing, Population-Based Tobacco Control, and Smoking Behavior. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:S327–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. 2008. doi: 10.1037/e481902008-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhee JU, Abugazia JY, Cruz YMED, et al. Use of internal documents to investigate a tobacco company’s strategies to market snus in the United States. Tob Prev Cessat 2021;7:11. doi: 10.18332/tpc/131809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siddiqui F, Khan T, Readshaw A, et al. Smokeless tobacco products, supply chain and retailers’ practices in England: a multimethods study to inform policy. Tob Control 2021;:tobaccocontrol-2020–055830. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Azzahro EA, Dewi DMSK, Puspikawati SI, et al. Two tobacco retailer programmes in Banyuwangi, Indonesia: a qualitative study. Tob Control 2021;0:1–6. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deadly Alliance Update: How Big Tobacco and Convenience Stores Partner to Hook Kids and Fight Life-Saving Policies. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; 2016. http://countertobacco.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Deadly_Alliance_2016.pdf (accessed 22 May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smiley SL, Cho J, Blackman KCA, et al. Retail Marketing of Menthol Cigarettes in Los Angeles, California: a Challenge to Health Equity. Prev Chronic Dis 2021;18:E11. doi: 10.5888/pcd18.200144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feighery E, Rogers T, Ribisl K. Tobacco Retail Price Manipulation Policy Strategy Summit Proceedings. Sacramento, CA: : California Department of Public Health, California Tobacco Control Program; 2009. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/DISEASESCONDITIONS/CHRONICDISEASE/HPCDPConnection/Training_Events/Documents/PlaceMatters2010/Community/CTCPPriceStrategySummit2009.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richardson E The Physician Payments Sunshine Act. Health Aff (Millwood) Published Online First: October 2014.https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20141002.272302/full/ (accessed 24 May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Sunshine Laws: Requiring Reporting of Tobacco Industry Price Discounting and Promotional Allowance Payments to Retailers and Wholesalers. Minnesota: 2012. https://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-sunshinelaws-tobaccocontrol-2012_0.pdf (accessed 29 Jul 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Johnson TO, et al. Assurances of Voluntary Compliance: A Regulatory Mechanism to Reduce Youth Access to E-Cigarettes and Limit Retail Tobacco Marketing. Am J Public Health 2020;110:209–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee JGL, Schleicher NC, Henriksen L. Sales to Minors, Corporate Brands, and Assurances of Voluntary Compliance. Tob Regul Sci 2019;5:431–9. doi: 10.18001/TRS.5.5.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dai H, Catley D. The effects of assurances of voluntary compliance on retail sales to minors in the United States: 2015–2016. Prev Med 2018;111:410–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.