Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant of concern evades antibody-mediated immunity that comes from vaccination or infection with earlier variants due to accumulation of numerous spike mutations. To understand the Omicron antigenic shift, we determined cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystal structures of the spike protein and the receptor-binding domain bound to the broadly neutralizing sarbecovirus monoclonal antibody (mAb) S309 (the parent mAb of sotrovimab) and to the human ACE2 receptor. We provide a blueprint for understanding the marked reduction of binding of other therapeutic mAbs that leads to dampened neutralizing activity. Remodeling of interactions between the Omicron receptor-binding domain and human ACE2 likely explains the enhanced affinity for the host receptor relative to the ancestral virus.

Although sequential COVID-19 waves have swept the world, no variants have accumulated mutations and mediated immune evasion to the extent observed for the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant of concern (VOC). This variant was first identified late November 2021 in South Africa and was quickly designated a VOC by the World Health Organization (1). Omicron has spread worldwide at a rapid pace compared to previous SARS-CoV-2 variants (2, 3). The Omicron spike (S) glycoprotein, which promotes viral entry into cells (4, 5), harbors 37 residue mutations in the predominant haplotype relative to Wuhan-Hu-1 S (4), as compared to approximately 10 substitutions in both SARS-CoV-2 Alpha and Delta VOC (2, 6). The Omicron receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the N-terminal domain (NTD) contain 15 and 11 mutations, respectively, which lead to severe dampening of plasma neutralizing activity in previously infected or vaccinated individuals (7-11). Although the Omicron RBD harbors 15 residue mutations, it binds to the human ACE2 entry receptor with high affinity while gaining the capacity to efficiently recognize mouse ACE2 (7). As a result of this antigenic shift, the only authorized or approved therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with neutralizing activity against Omicron are S309 (sotrovimab parent) and the COV2-2196/COV2-2130 cocktail (cilgavimab/tixagevimab parents). Even these mAbs experienced 2-3-fold and 12-200-fold reduced potency, respectively, using pseudovirus or authentic virus assays (7-11). This extent of evasion of humoral responses has important consequences for therapy and prevention of both the current pandemic and future pandemics, underscoring the necessity of defining the molecular mechanisms of these changes.

To provide a structural framework for the observed Omicron immune evasion and altered receptor recognition, we determined cryoEM structures of the prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Omicron S ectodomain trimer bound to S309 and S2L20 (NTD-specific mAb) Fab fragments (Fig. 1, fig. S1 and Table S1) and the X-ray crystal structure of the Omicron RBD in complex with human ACE2 and the Fab fragments of S309 and S304 at 2.85 Å resolution (Table S2). S309 recognizes antigenic site IV (12) whereas S304 binds to site IIc (13) and was used to assist crystallization. Furthermore, we evaluated the binding of clinical mAbs to the Omicron RBD and S ectodomain trimer using surface plasmon resonance (SPR).

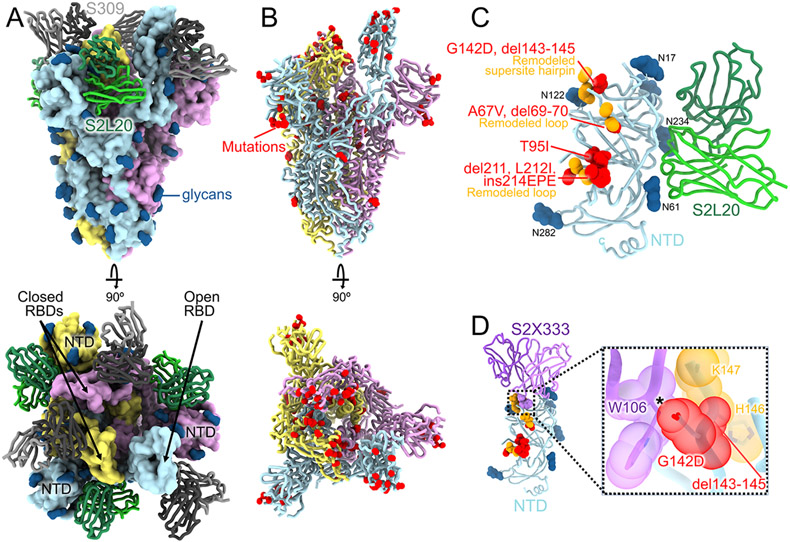

Fig. 1. CryoEM structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron S trimer reveals a remodeling of the NTD antigenic supersite.

(A) Surface rendering in two orthogonal orientations of the Omicron S trimer with one open RBD bound to the S309 (grey) and S2L20 (green) Fabs shown as ribbons. The three S protomers are colored light blue, pink or gold. N-linked glycans are shown as dark blue surfaces. (B) Ribbon diagrams in two orthogonal orientations of the S trimer with one open RBD with Omicron residues mutated relative to Wuhan-Hu-1 shown as red spheres (except D614G which is not shown). (C) The S2L20-bound Omicron NTD with mutated, deleted, or inserted residues rendered or indicated as red spheres. Segments with notable structural changes are shown in orange and labeled. (D) Zoomed-in view of the Omicron NTD antigenic supersite overlaid with the S2X333 Fab (used here as an example of prototypical NTD neutralizing mAb (22)) highlighting the binding incompatibility; the modeled clash between S2X333 W106 and NTD G142D is indicated with an asterisk.

3D classification of the cryoEM data revealed the presence of two conformational states with one (45% of selected particles) or two (55% of selected particles) RBDs in the open conformation for which we determined structures at 3.1 Å and 3.2 Å resolution, respectively (Fig. 1A-B, fig. S1-S2 and Table S1). The larger fraction of open RBDs, relative to the apo (4, 5) and S309-bound (12) Wuhan-Hu-1 S ectodomain trimer structures, could result from the Omicron mutations, the prefusion-stabilizing mutations (14, 15) or S2L20 binding. Focused classification and local refinement of the S309-bound RBD (domain B) and of the S2L20-bound NTD (domain A) were used to account for their conformational dynamics and improve local resolution of these regions to 3.0 and 3.3 Å resolution, respectively.

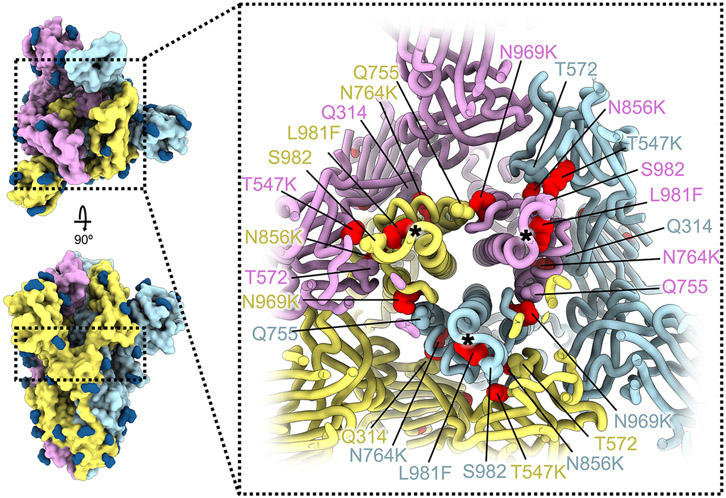

Whereas most VOC have only a few mutations beyond the NTD, RBD, and furin cleavage site regions, the Omicron spike harbors eight substitutions outside of these areas: T547K, H655Y, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, and L981F, which could all be modeled in the map (Fig. 1A-B and Fig 2). Three of these mutations introduce inter-protomer electrostatic contacts between the S2 and S1 subunits: N764K binds Q314 (in domain D), S982 binds T547K (in domain C of protomers with closed RBDs), and N856K binds D568 and T572 (in domain C, the former residue is closer to N856K in protomers with closed RBDs) (Fig. 2) (16, 17). Furthermore, N969K forms inter-protomer electrostatic contacts with Q755 and L981F improves intra-protomer hydrophobic packing in the pre-fusion conformation (Fig. 2). The latter mutation is close to the prefusion-stabilizing 2P mutations (K986P and V987P) used in all three vaccines deployed in the US (Fig. 2). Putatively enhanced interactions between the S1 and S2 subunits in Omicron S along with pre-fusion stabilization, and altered processing at the S1/S2 cleavage site due to the N679K and P681H mutations, might reduce S1 shedding, consistent with recent studies (18-20). Dampened S1 subunit shedding might enhance the effector function activity of vaccine- or infection-elicited Abs along with that of therapeutic mAbs (21) that retain affinity for Omicron S.

Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron S mutations outside the NTD and RBD.

Ribbon diagram showing a cross-section of the Omicron S glycoprotein (the location of this slice on the S trimer is indicated on the left). Mutated residues T547K, N764K, N856K, N969K, and L981F are shown as red spheres whereas the residues they contact are shown as spheres colored as the protomer they belong to. Black asterisks show the position of residues involved in the prefusion-stabilizing 2P mutations (K986P and V987P) used in all three vaccines deployed in the US. The three S protomers are colored light blue, pink or gold. N-linked glycans are shown as dark blue surfaces.

The Omicron NTD carries numerous mutations, deletions (del), and an insertion (ins) including A67V, del69-70, T95I, G142D, del143-145, del211, L212I, and ins214EPE (Fig. 1C, fig S3). Many of these mutations have been described in previously emerged VOC: del69-70 was found in Alpha, T95I was present in Kappa and Iota, and G142D was present in Kappa and Delta. T95I, del211, L212I, and ins214EPE are outside the NTD antigenic supersite but in the vicinity of the epitope targeted by the P008_056 mAb, suggesting these mutations could putatively modulate recognition of similar mAbs or have another functional relevance. Although the region comprising del143-145 is weakly resolved in the map, it is expected to alter antibody recognition due to the introduced sequence register shift whereas G142D is incompatible with binding of several potent NTD neutralizing mAbs, such as S2X333, due to steric hindrance (Fig. 1D) (2, 22). Moreover, del143-145 is reminiscent of the Alpha del144 which was also isolated as an escape mutation in the presence of mAb S2X333 and led to viral breakthrough in a hamster challenge model (22). These data suggest that G142D and del143-145 account for the observed SARS-CoV-2 Omicron evasion from neutralization mediated by a panel of NTD mAbs (7, 9).

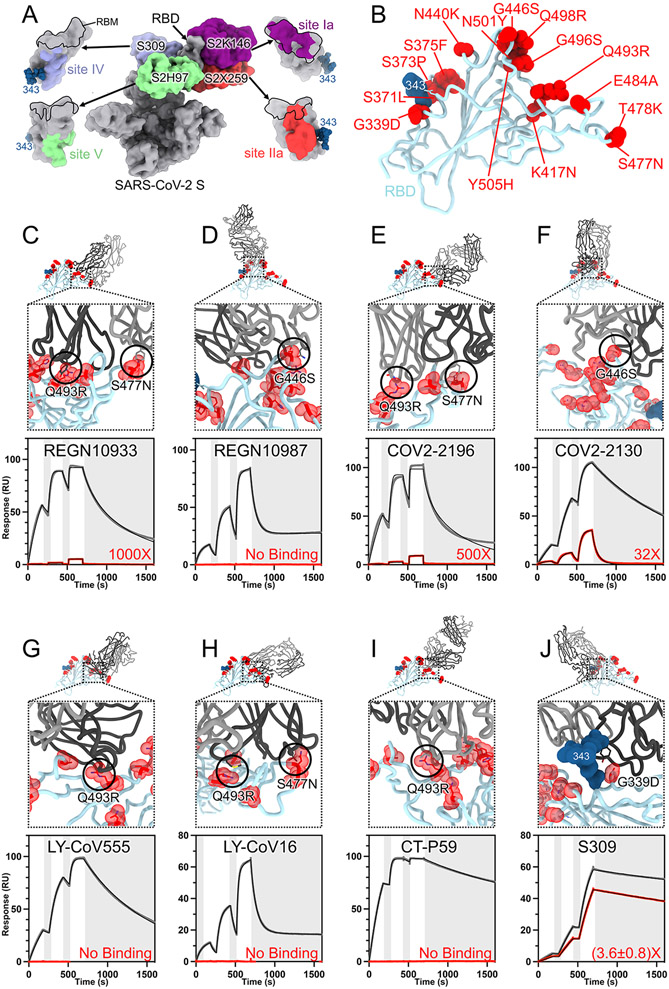

The RBD is the main target of plasma neutralizing activity in convalescent and vaccinated individuals and comprises several antigenic sites recognized by neutralizing Abs with a range of neutralization potencies and breadth (12, 13, 21, 23-36) (Fig. 3A). Our structures provide a high-resolution blueprint of the residue substitutions found in this variant (Fig. 3B) and their impact on binding of clinical mAbs (Table 1). Several individual mutations or subsets of mutations occurring in the Omicron RBD have been reported previously to impact neutralizing antibody binding or neutralization (37). The K417N, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y and Y505H mutations are part of antigenic site I, which is immunodominant in previous variants (13, 24). K417N, E484A, S477N, and Q493R would lead to loss of electrostatic interactions and steric clashes with REGN10933 whereas G446S would lead to steric clashes with REGN10987, consistent with the dampened binding to the Omicron RBD and S trimer (Fig. 3 C-D, fig S3 and Table S3) and with previous analyses of the impact of individual mutations on neutralization by each of these two mAbs (9, 38-40). Moreover, N440K was reported to dampen REGN10987 neutralization severely (9). Reduced binding of the Omicron RBD to COV2-2196 and COV2-2130, relative to the Wuhan-Hu-1 RBD, likely results from the T478K (based on Delta S (2)), Q493R and putatively S477N for COV2-2196, as well as G446S and E484A for COV2-2130 (Fig. 3 E-F, fig S4 and Table S3). Integrating these data with neutralization assays suggests that although each point mutation only imparts a small reduction of COV2-2196- or COV2-2130-mediated neutralization (9), the constellation of Omicron mutations leads to more pronounced loss of activity (7-11). E484A abrogates electrostatic interactions with LY-CoV555 heavy and light chains, while Q493R would prevent binding through steric hindrance (Fig. 3G, fig S4 and Table S3), as supported by neutralization data (9). K417N is expected to negatively affect the constellation of electrostatic interactions formed between the Omicron RBD and LY-CoV16 heavy chain, thereby abolishing binding (Fig. 3H, fig S4 and Table S3) and neutralization of single mutant S pseudoviruses (9, 40, 41). Furthermore, S477N and Q493R have been shown to dampen binding of and neutralization mediated by LY-CoV16 (9, 41). Finally, K417N, E484A and Q493R hinder CT-P59 engagement through a combination of steric hindrance and remodeling of electrostatic contacts, thereby preventing binding (Fig. 3I, fig S4 and Table S3 and Table S1).

Fig. 3. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron RBD mutations promote escape from a panel of clinical mAbs.

A, RBD antigenic map as determined elsewhere (13). B, Ribbon diagram of the RBD crystal structure with residue mutated relative to the Wuhan-Hu-1 RBD shown as red spheres. The N343 glycan is rendered as blue spheres. C-J, Zoomed-in view of the Omicron RBD (blue) superimposed on structures of clinical mAbs (grey) highlighting (black circles) selected residues that interfere with the mAbs: (C) REGN10933, (D) REGN10987, (E) COV2-2196, (F) COV2-2130, (G) LY-CoV555, (H) LY-CoV16, (I) CT-P59, and (J) S309 which does not clash with G339D. Panels A-I were rendered with the crystal structure whereas panel J was generated using the cryoEM model. Binding of the Wuhan-Hu-1 (gray line) or Omicron (red line) RBD to the corresponding mAb was evaluated using surface plasmon resonance (single-cycle kinetics) and is shown underneath each structural superimposition. White and gray stripes are association and dissociation phases, respectively. The black line is a fit to a kinetic model. The decrease in affinity between Wuhan-Hu-1 and Omicron binding is indicated in red. Results are consistent with IgG binding to S ectodomains (Fig. S3).

Table 1:

Omicron RBD mutations with a demonstrated (X) or expected (x) reduction of binding or neutralization and based on our structural analyses.

| REGN10933 | REGN10987 | COV2-2196 | COV2-2130 | LY-CoV555 | LY-CoV016 | CT-P59 | S309 | ADI-58125 | Total GISAID counts** |

Omicron counts |

VOC, VOI, VUM harboring mutation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G339D | 196,756 | 192,125 | ||||||||||

| S371L | 182,692 | 179,486 | ||||||||||

| S373P | 185,025 | 181,374 | ||||||||||

| S375F | 184,990 | 181,461 | ||||||||||

| K417N | X | X | X | 116,510 | 70,903 | Beta, K417T in Gamma | ||||||

| N440K | 92,338 | 79,859 | ||||||||||

| G446S | X | x | 83,953 | 80,518 | ||||||||

| S477N | x | X | x | 262,216 | 187,081 | |||||||

| T478K | X | 3,976,461 | 187,859 | Delta | ||||||||

| E484A | X | X | X | X | 192,062 | 186,965 | E484K in Beta, Gamma, Mu, Iota, Eta, Zeta, Theta; E484Q in Kappa | |||||

| Q493R | X | X | x | X | x | X | 191,484 | 188,353 | ||||

| G496S | X | 187,583 | 184,575 | |||||||||

| Q498R | X | 188,462 | 185,805 | |||||||||

| N501Y | 1,434,752 | 186,285 | Alpha, Beta, Theta, N501K in Mu | |||||||||

| Y505H | X* | 188,250 | 185,491 | |||||||||

| PDB ID | 6XDG | 6XDG | 7L7D | 7L7E | 7KMG | 7C01 | 7CM4 | This study | n/a |

For ADI-58125, the impact on binding of C, N, and S substitutions is shown at position Y505 based on mutagenesis studies Belk, J., Deveau, L. M., Rappazzo, C. G., Walker, L. & Wec, A. WO2021207597 - COMPOUNDS SPECIFIC TO CORONAVIRUS S PROTEIN AND USES THEREOF. ADAGIO THERAPEUTICS, INC. (2021).

As of January 9, 2022; excluded entries with >5% Ns.

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron G339D and N440K mutations are within or nearby antigenic site IV, which is recognized by the S309 mAb (12). Nevertheless, S309 only experiences a 2 to 3-fold reduction of neutralizing activity against Omicron relative to Wuhan-Hu-1 pseudovirus or Washington-1 authentic virus (7, 9-11). The lysine side chain introduced by the N440K substitution points away from the S309 epitope and does not affect binding. The aspartic acid side chain introduced by the G339D substitution does not interfere the S309 epitope although not all rotamers are compatible with mAb binding (fig S2). This finding likely explains the similarly moderate reduction of S309 potency against the single G339D S mutant (9) or the full constellation of Omicron S mutations (7, 9-11). The modest reduction of the Omicron RBD binding to S309 (Fig 3J, fig S4 and Table S3) mirrors the 2-3-fold reduced neutralization potency of this VOC, relative to ancestral viruses, and concurs with deep-mutational scanning analysis of individual mutations on S309 recognition (24). Overall, the S309 binding mode remains unaltered by the Omicron mutations, including recognition of the N343 glycan (fig S5).

The Omicron RBD is structurally similar to the Wuhan-Hu-1 RBD and both structures can be superimposed with an r.m.s.d. of 0.8Å over 183 aligned Cɑ residues (as compared to PDB 6m0j (42)). However, the region comprising residues 366 to 375, which harbors the S371L/S373P/S375F substitutions, deviates markedly from the conformation observed for the Wuhan-Hu-1 RBD, irrespective of the presence of bound linoleic acid (4, 42, 43). Although this region is weakly resolved in the cryoEM and X-ray structures, the conformation adopted in the latter structure is incompatible with binding of some cross-reactive site II mAbs such as S2X35, consistent with our observation of dampened binding (Fig S6). We therefore propose that these mutations participate in rendering this region of the RBD dynamic and mediate immune evasion from some site II mAbs.

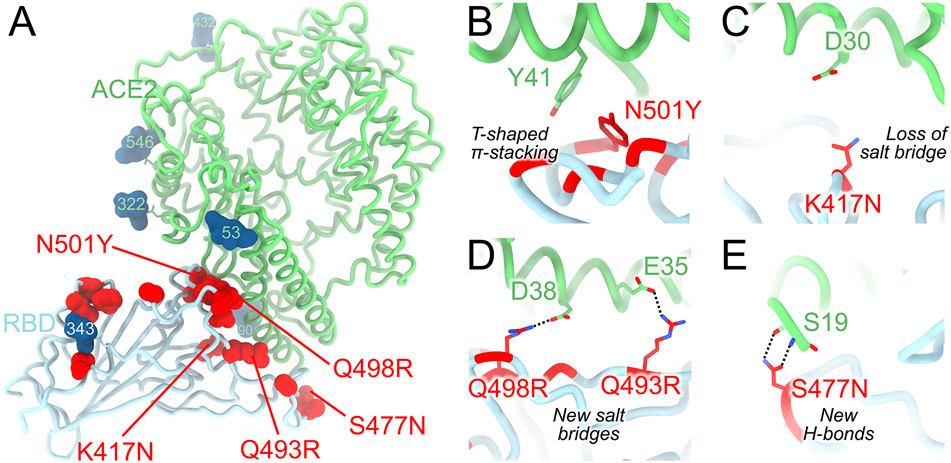

We recently reported that the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron RBD binds human ACE2 with a ~2.4 fold enhanced affinity relative to the Wuhan-Hu-1 RBD (7). Our crystal structure of the human ACE2-bound Omicron RBD elucidates how the constellation of RBD mutations found in this VOC impact receptor recognition (Fig. 4A and Table S2). The N501Y mutation alone enhances ACE2 binding to the RBD by a factor of 6 relative to the Wuhan-Hu-1 RBD, as reported for the Alpha variant (6), likely as a result of increased shape complementarity between the introduced tyrosine side chain and the ACE2 Y41 and K353 side chains (Fig. 4B). Omicron S residue Y501 and ACE2 residue Y41 form a T-shaped π–π stacking interaction, as previously observed for an N501Y-harboring S structure in complex with ACE2 (44). The K417N mutation dampens receptor recognition by about 3-fold (2, 6, 39, 45) likely through loss of a salt bridge with ACE2 D30 (Fig. 4C). The Q493R and Q498R mutations introduce two new salt bridges with E35 and E38, respectively, replacing hydrogen bonds formed with the Wuhan-Hu-1 RBD, thereby remodeling the electrostatic interactions with ACE2 (Fig. 4D). Both of these individual mutations were reported to reduce ACE2 binding avidity slightly by deep-mutational scanning studies of the yeast-displayed SARS-CoV-2 RBD (46). Finally, S477N leads to formation of new hydrogen bonds between the introduced asparagine side chain and the ACE2 S19 backbone amine and carbonyl groups (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these mutations have a net enhancing effect on binding of the Omicron RBD to human ACE2, relative to Wuhan-Hu-1, suggesting that structural epistasis enables immune evasion while retaining efficient receptor engagement. The large number of Omicron mutations in the immunodominant receptor-binding motif likely explains a significant proportion of the loss of neutralization by convalescent and vaccine-elicited polyclonal antibodies, and is in line with the known plasticity of this subdomain (24).

Figure 4. Molecular basis of human ACE2 recognition by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron RBD.

A, Ribbon diagram of the crystal structure of the Omicron RBD in complex with the ACE2 ectodomain. The S309 and S304 Fab fragments are not shown for clarity. B-E, Zoomed-in views of the RBD/ACE2 interface highlighting modulation of interactions due to introduction of the N501Y (B), K417N (C), Q493R/Q498R (D) and S477N (E) residue substitutions.

Although the N501Y mutation has been described previously to enable some SARS-CoV-2 VOC to infect and replicate in mice, the Alpha and Beta variant RBDs only weakly bound mouse ACE2 (47, 48). The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron RBD, however, interacts more strongly with mouse ACE2 than the Alpha and Beta variant RBDs when evaluated side-by-side (fig S7A) and can utilize mouse ACE2 as an entry receptor for S-mediated entry (7, 49). We propose that the Q493R mutation plays a key role in enabling efficient mouse ACE2 binding, through formation of a new electrostatic interaction with the N31 side chain amide (K31 in human ACE2), as supported by in silico modeling based on our human ACE2-bound crystal structure (fig S7B). These findings concur with the emergence and fixation of the Q493K RBD mutation upon serial passaging in mice to yield a mouse-adapted virus designated SARS-CoV-2 MA10 (50).

This work defines the molecular basis for the broad evasion of humoral immunity exhibited by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and underscores the SARS-CoV-2 S mutational plasticity and the importance of targeting conserved epitopes in design and development of vaccines and therapeutics. The S309 mAb, which is the parent of sotrovimab, neutralizes Omicron with 2-3-fold reduced potency compared to Wuhan-Hu-1 or Washington-1, while the 7 other clinical mAbs or mAb cocktails experience reduction of neutralizing activity of 1-2 orders of magnitude or greater. Furthermore, some Omicron isolates (≈9%) harbor the R346K substitution which in conjunction with N440K (present in the main haplotype) leads to escape from C135 mAb-mediated neutralization (25, 51). R346K does not affect S309 whether in isolation or in the context of the full constellation of Omicron mutations illustrating that mAbs targeting antigenic site IV can be differently affected by Omicron (7, 9, 46). Whereas C135 was identified from a SARS-CoV-2 convalescent donor (25), S309 was isolated from a subject who recovered from a SARS-CoV infection in 2003 (12); the latter strategy increased the likelihood of finding mAbs recognizing epitopes that are mutationally constrained throughout sarbecovirus evolution. The identification of broadly reactive mAbs that neutralize multiple distinct sarbecoviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 variants, pave the way for designing vaccines eliciting broad sarbecovirus immunity (52-56). These efforts offer hope that the same strategies that contribute to solving the current pandemic will prepare us for possible future sarbecovirus pandemics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (DP1AI158186 and HHSN272201700059C to D.V.), a Pew Biomedical Scholars Award (D.V.), an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Awards from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (D.V.), Fast Grants (D.V.), the University of Washington Arnold and Mabel Beckman cryoEM center and the National Institute of Health grant S10OD032290 (to D.V.). D.V. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Beamline 4.2.2 of the Advanced Light Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, is supported in part by the ALS-ENABLE program funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, grant P30 GM124169-01. This research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Wellcome Trust [209407/Z/17/Z]. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Footnotes

Competing interests: N.C., L.E.R., J.R.D., A.E.P., H.W.V., D.C. and G.S. are employees of Vir Biotechnology Inc. and may hold shares in Vir Biotechnology Inc. D.C. is currently listed as an inventor on multiple patent applications, which disclose the subject matter described in this manuscript. H.W.V. is a founder and hold shares in PierianDx and Casma Therapeutics. Neither company provided resources. The Veesler laboratory has received a sponsored research agreement from Vir Biotechnology Inc. Tristan Croll’s contribution was made under terms of paid consultancy from Vir Biotechnology Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data and Materials Availability. The cryoEM map and coordinates have been deposited to the Electron Microscopy Databank and Protein Data Bank with accession numbers TBD. The crystal structure has been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with accession number TBD. Materials generated in this study will be made available on request, but we may require a completed materials transfer agreement signed with Vir Biotechnology or the University of Washington.

References

- 1.Viana R, Moyo S, Amoako DG, Tegally H, Scheepers C, Althaus CL, Anyaneji UJ, Bester PA, Boni MF, Chand M, Choga WT, Colquhoun R, Davids M, Deforche K, Doolabh D, du Plessis L, Engelbrecht S, Everatt J, Giandhari J, Giovanetti M, Hardie D, Hill V, Hsiao N-Y, Iranzadeh A, Ismail A, Joseph C, Joseph R, Koopile L, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Kraemer MUG, Kuate-Lere L, Laguda-Akingba O, Lesetedi-Mafoko O, Lessells RJ, Lockman S, Lucaci AG, Maharaj A, Mahlangu B, Maponga T, Mahlakwane K, Makatini Z, Marais G, Maruapula D, Masupu K, Matshaba M, Mayaphi S, Mbhele N, Mbulawa MB, Mendes A, Mlisana K, Mnguni A, Mohale T, Moir M, Moruisi K, Mosepele M, Motsatsi G, Motswaledi MS, Mphoyakgosi T, Msomi N, Mwangi PN, Naidoo Y, Ntuli N, Nyaga M, Olubayo L, Pillay S, Radibe B, Ramphal Y, Ramphal U, San JE, Scott L, Shapiro R, Singh L, Smith-Lawrence P, Stevens W, Strydom A, Subramoney K, Tebeila N, Tshiabuila D, Tsui J, van Wyk S, Weaver S, Wibmer CK, Wilkinson E, Wolter N, Zarebski AE, Zuze B, Goedhals D, Preiser W, Treurnicht F, Venter M, Williamson C, Pybus OG, Bhiman J, Glass A, Martin DP, Rambaut A, Gaseitsiwe S, von Gottberg A, de Oliveira T, Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature (2022), doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCallum M, Walls AC, Sprouse KR, Bowen JE, Rosen LE, Dang HV, De Marco A, Franko N, Tilles SW, Logue J, Miranda MC, Ahlrichs M, Carter L, Snell G, Pizzuto MS, Chu HY, Van Voorhis WC, Corti D, Veesler D, Molecular basis of immune evasion by the Delta and Kappa SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science, eabl8506 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCallum M, Bassi J, De Marco A, Chen A, Walls AC, Di Iulio J, Tortorici MA, Navarro M-J, Silacci-Fregni C, Saliba C, Sprouse KR, Agostini M, Pinto D, Culap K, Bianchi S, Jaconi S, Cameroni E, Bowen JE, Tilles SW, Pizzuto MS, Guastalla SB, Bona G, Pellanda AF, Garzoni C, Van Voorhis WC, Rosen LE, Snell G, Telenti A, Virgin HW, Piccoli L, Corti D, Veesler D, SARS-CoV-2 immune evasion by the B.1.427/B.1.429 variant of concern. Science (2021), doi: 10.1126/science.abi7994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D, Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell. 181, 281–292.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS, Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 367, 1260–1263 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collier DA, De Marco A, Ferreira IATM, Meng B, Datir R, Walls AC, Kemp S SA, Bassi J, Pinto D, Fregni CS, Bianchi S, Tortorici MA, Bowen J, Culap K, Jaconi S, Cameroni E, Snell G, Pizzuto MS, Pellanda AF, Garzoni C, Riva A, Elmer A, Kingston N, Graves B, McCoy LE, Smith KGC, Bradley JR, Temperton N, Lourdes Ceron-Gutierrez L, Barcenas-Morales G, Harvey W, Virgin HW, Lanzavecchia A, Piccoli L, Doffinger R, Wills M, Veesler D, Corti D, Gupta RK, The CITIID-NIHR BioResource COVID-19 Collaboration, The COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium, Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 to mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03412-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameroni E, Bowen JE, Rosen LE, Saliba C, Zepeda SK, Culap K, Pinto D, VanBlargan LA, De Marco A, di Iulio J, Zatta F, Kaiser H, Noack J, Farhat N, Czudnochowski N, Havenar-Daughton C, Sprouse KR, Dillen JR, Powell AE, Chen A, Maher C, Yin L, Sun D, Soriaga L, Bassi J, Silacci-Fregni C, Gustafsson C, Franko NM, Logue J, Iqbal NT, Mazzitelli I, Geffner J, Grifantini R, Chu H, Gori A, Riva A, Giannini O, Ceschi A, Ferrari P, Cippà PE, Franzetti-Pellanda A, Garzoni C, Halfmann PJ, Kawaoka Y, Hebner C, Purcell LA, Piccoli L, Pizzuto MS, Walls AC, Diamond MS, Telenti A, Virgin HW, Lanzavecchia A, Snell G, Veesler D, Corti D, Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03825-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Y, Wang J, Jian F, Xiao T, Song W, Yisimayi A, Huang W, Li Q, Wang P, An R, Wang J, Wang Y, Niu X, Yang S, Liang H, Sun H, Li T, Yu Y, Cui Q, Liu S, Yang X, Du S, Zhang Z, Hao X, Shao F, Jin R, Wang X, Xiao J, Wang Y, Xie XS, Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03796-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Iketani S, Guo Y, Chan JF-W, Wang M, Liu L, Luo Y, Chu H, Huang Y, Nair MS, Yu J, Chik KK-H, Yuen TT-T, Yoon C, To KK-W, Chen H, Yin MT, Sobieszczyk ME, Huang Y, Wang HH, Sheng Z, Yuen K-Y, Ho DD, Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03826-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Planas D, Saunders N, Maes P, Guivel-Benhassine F, Planchais C, Buchrieser J, Bolland W-H, Porrot F, Staropoli I, Lemoine F, Péré H, Veyer D, Puech J, Rodary J, Baela G, Dellicour S, Raymenants J, Gorissen S, Geenen C, Vanmechelen B, Wawina-Bokalanga T, Martí-Carrerasi J, Cuypers L, Sève A, Hocqueloux L, Prazuck T, Rey F, Simon-Lorrière E, Bruel T, Mouquet H, André E, Schwartz O, Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VanBlargan LA, Errico JM, Halfmann PJ, Zost SJ, Crowe JE Jr, Purcell LA, Kawaoka Y, Corti D, Fremont DH, Diamond MS, An infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron virus escapes neutralization by several therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. bioRxiv (2021), , doi: 10.1101/2021.12.15.472828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto D, Park YJ, Beltramello M, Walls AC, Tortorici MA, Bianchi S, Jaconi S, Culap K, Zatta F, De Marco A, Peter A, Guarino B, Spreafico R, Cameroni E, Case JB, Chen RE, Havenar-Daughton C, Snell G, Telenti A, Virgin HW, Lanzavecchia A, Diamond MS, Fink K, Veesler D, Corti D, Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature. 583, 290–295 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piccoli L, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Czudnochowski N, Walls AC, Beltramello M, Silacci-Fregni C, Pinto D, Rosen LE, Bowen JE, Acton OJ, Jaconi S, Guarino B, Minola A, Zatta F, Sprugasci N, Bassi J, Peter A, De Marco A, Nix JC, Mele F, Jovic S, Rodriguez BF, Gupta SV, Jin F, Piumatti G, Lo Presti G, Pellanda AF, Biggiogero M, Tarkowski M, Pizzuto MS, Cameroni E, Havenar-Daughton C, Smithey M, Hong D, Lepori V, Albanese E, Ceschi A, Bernasconi E, Elzi L, Ferrari P, Garzoni C, Riva A, Snell G, Sallusto F, Fink K, Virgin HW, Lanzavecchia A, Corti D, Veesler D, Mapping Neutralizing and Immunodominant Sites on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-Binding Domain by Structure-Guided High-Resolution Serology. Cell. 183, 1024–1042.e21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh CL, Goldsmith JA, Schaub JM, DiVenere AM, Kuo HC, Javanmardi K, Le KC, Wrapp D, Lee AG, Liu Y, Chou CW, Byrne PO, Hjorth CK, Johnson NV, Ludes-Meyers J, Nguyen AW, Park J, Wang N, Amengor D, Lavinder JJ, Ippolito GC, Maynard JA, Finkelstein IJ, McLellan JS, Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Science (2020), doi: 10.1126/science.abd0826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olmedillas E, Mann CJ, Peng W, Wang YT, Avalos RD, Structure-based design of a highly stable, covalently-linked SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer with improved structural properties and immunogenicity. bioRxiv (2021) (available at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.06.441046v1.abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walls AC, Tortorici MA, Bosch BJ, Frenz B, Rottier PJM, DiMaio F, Rey FA, Veesler D, Cryo-electron microscopy structure of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimer. Nature. 531, 114–117 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tortorici MA, Veesler D, Structural insights into coronavirus entry. Adv. Virus Res 105, 93–116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cong Z, Evans JP, Qu P, Faraone J, Zheng Y-M, Carlin C, Bednash JS, Zhou T, Lozanski G, Mallampalli R, Saif LJ, Oltz EM, Mohler P, Xu K, Gumina RJ, Liu S-L, Neutralization and Stability of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant, , doi: 10.1101/2021.12.16.472934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng B, Ferreira IATM, Abdullahi A, Kemp SA, Goonawardane N, Papa G, Fatihi S, Charles OJ, Collier DA, Choi J, Lee JH, Mlcochova P, James L, Doffinger R, Thukral L, Sato K, Gupta RK, CITIID-NIHR BioResource COVID-19 Collaboration, The Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium, SARS-CoV-2 Omicron spike mediated immune escape, infectivity and cell-cell fusion. bioRxiv (2021), , doi: 10.1101/2021.12.17.473248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato K, Suzuki R, Yamasoba D, Kimura I, Wang L, Kishimoto M, Ito J, Morioka Y, Nao N, Nasser H, Uriu K, Kosugi Y, Tsuda M, Orba Y, Sasaki M, Shimizu R, Kawabata R, Yoshimatsu K, Asakura H, Nagashima M, Sadamasu K, Yoshimura K, Sawa H, Ikeda T, Irie T, Matsuno K, Tanaka S, Fukuhara T, Attenuated fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Research Square (2022), , doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1207670/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tortorici MA, Czudnochowski N, Starr TN, Marzi R, Walls AC, Zatta F, Bowen JE, Jaconi S, Di Iulio J, Wang Z, De Marco A, Zepeda SK, Pinto D, Liu Z, Beltramello M, Bartha I, Housley MP, Lempp FA, Rosen LE, Dellota E Jr, Kaiser H, Montiel-Ruiz M, Zhou J, Addetia A, Guarino B, Culap K, Sprugasci N, Saliba C, Vetti E, Giacchetto-Sasselli I, Fregni CS, Abdelnabi R, Foo S-YC, Havenar-Daughton C, Schmid MA, Benigni F, Cameroni E, Neyts J, Telenti A, Virgin HW, Whelan SPJ, Snell G, Bloom JD, Corti D, Veesler D, Pizzuto MS, Broad sarbecovirus neutralization by a human monoclonal antibody. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCallum M, De Marco A, Lempp FA, Tortorici MA, Pinto D, Walls AC, Beltramello M, Chen A, Liu Z, Zatta F, Zepeda S, di Iulio J, Bowen JE, Montiel-Ruiz M, Zhou J, Rosen LE, Bianchi S, Guarino B, Fregni CS, Abdelnabi R, Caroline Foo S-Y, Rothlauf PW, Bloyet L-M, Benigni F, Cameroni E, Neyts J, Riva A, Snell G, Telenti A, Whelan SPJ, Virgin HW, Corti D, Pizzuto MS, Veesler D, N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell (2021), doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamatatos L, Czartoski J, Wan Y-H, Homad LJ, Rubin V, Glantz H, Neradilek M, Seydoux E, Jennewein MF, MacCamy AJ, Feng J, Mize G, De Rosa SC, Finzi A, Lemos MP, Cohen KW, Moodie Z, Juliana McElrath M, McGuire AT, mRNA vaccination boosts cross-variant neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science (2021), p. eabg9175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starr TN, Czudnochowski N, Liu Z, Zatta F, Park Y-J, Addetia A, Pinto D, Beltramello M, Hernandez P, Greaney AJ, Marzi R, Glass WG, Zhang I, Dingens AS, Bowen JE, Tortorici MA, Walls AC, Wojcechowskyj JA, De Marco A, Rosen LE, Zhou J, Montiel-Ruiz M, Kaiser H, Dillen J, Tucker H, Bassi J, Silacci-Fregni C, Housley MP, di Iulio J, Lombardo G, Agostini M, Sprugasci N, Culap K, Jaconi S, Meury M, Dellota E, Abdelnabi R, Foo S-YC, Cameroni E, Stumpf S, Croll TI, Nix JC, Havenar-Daughton C, Piccoli L, Benigni F, Neyts J, Telenti A, Lempp FA, Pizzuto MS, Chodera JD, Hebner CM, Virgin HW, Whelan SPJ, Veesler D, Corti D, Bloom JD, Snell G, SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies that maximize breadth and resistance to escape. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03807-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes CO, Jette CA, Abernathy ME, Dam K-MA, Esswein SR, Gristick HB, Malyutin AG, Sharaf NG, Huey-Tubman KE, Lee YE, Robbiani DF, Nussenzweig MC, West AP Jr, Bjorkman PJ, SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature. 588, 682–687 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jette CA, Cohen AA, Gnanapragasam PNP, Muecksch F, Lee YE, Huey-Tubman KE, Schmidt F, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD, Nussenzweig MC, West AP Jr, Keeffe JR, Bjorkman PJ, Barnes CO, Broad cross-reactivity across sarbecoviruses exhibited by a subset of COVID-19 donor-derived neutralizing antibodies. Cell Rep. 36, 109760 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnes CO, West AP Jr, Huey-Tubman KE, Hoffmann MAG, Sharaf NG, Hoffman PR, Koranda N, Gristick HB, Gaebler C, Muecksch F, Lorenzi JCC, Finkin S, Hägglöf T, Hurley A, Millard KG, Weisblum Y, Schmidt F, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD, Caskey M, Robbiani DF, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ, Structures of Human Antibodies Bound to SARS-CoV-2 Spike Reveal Common Epitopes and Recurrent Features of Antibodies. Cell. 182, 828–842.e16 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zost SJ, Gilchuk P, Case JB, Binshtein E, Chen RE, Nkolola JP, Schäfer A, Reidy JX, Trivette A, Nargi RS, Sutton RE, Suryadevara N, Martinez DR, Williamson LE, Chen EC, Jones T, Day S, Myers L, Hassan AO, Kafai NM, Winkler ES, Fox JM, Shrihari S, Mueller BK, Meiler J, Chandrashekar A, Mercado NB, Steinhardt JJ, Ren K, Loo YM, Kallewaard NL, McCune BT, Keeler SP, Holtzman MJ, Barouch DH, Gralinski LE, Baric RS, Thackray LB, Diamond MS, Carnahan RH, Crowe JE, Potently neutralizing and protective human antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 584, 443–449 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez DR, Schäfer A, Gobeil S, Li D, De la Cruz G, Parks R, Lu X, Barr M, Stalls V, Janowska K, Beaudoin E, Manne K, Mansouri K, Edwards RJ, Cronin K, Yount B, Anasti K, Montgomery SA, Tang J, Golding H, Shen S, Zhou T, Kwong PD, Graham BS, Mascola JR, Montefiori DC, Alam SM, Sempowski GD, Khurana S, Wiehe K, Saunders KO, Acharya P, Haynes BF, Baric RS, A broadly cross-reactive antibody neutralizes and protects against sarbecovirus challenge in mice. Sci. Transl. Med, eabj7125 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong J, Zost SJ, Greaney AJ, Starr TN, Dingens AS, Chen EC, Chen RE, Case JB, Sutton RE, Gilchuk P, Rodriguez J, Armstrong E, Gainza C, Nargi RS, Binshtein E, Xie X, Zhang X, Shi P-Y, Logue J, Weston S, McGrath ME, Frieman MB, Brady T, Tuffy KM, Bright H, Loo Y-M, McTamney PM, Esser MT, Carnahan RH, Diamond MS, Bloom JD, Crowe JE Jr, Genetic and structural basis for SARS-CoV-2 variant neutralization by a two-antibody cocktail. Nat Microbiol. 6, 1233–1244 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Gentles LE, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, Bloom JD, Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci. Transl. Med 13 (2021), doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abi9915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen J, Baum A, Pascal KE, Russo V, Giordano S, Wloga E, Fulton BO, Yan Y, Koon K, Patel K, Chung KM, Hermann A, Ullman E, Cruz J, Rafique A, Huang T, Fairhurst J, Libertiny C, Malbec M, Lee WY, Welsh R, Farr G, Pennington S, Deshpande D, Cheng J, Watty A, Bouffard P, Babb R, Levenkova N, Chen C, Zhang B, Romero Hernandez A, Saotome K, Zhou Y, Franklin M, Sivapalasingam S, Lye DC, Weston S, Logue J, Haupt R, Frieman M, Chen G, Olson W, Murphy AJ, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD, Kyratsous CA, Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science (2020), doi: 10.1126/science.abd0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rappazzo CG, Tse LV, Kaku CI, Wrapp D, Sakharkar M, Huang D, Deveau LM, Yockachonis TJ, Herbert AS, Battles MB, O’Brien CM, Brown ME, Geoghegan JC, Belk J, Peng L, Yang L, Hou Y, Scobey TD, Burton DR, Nemazee D, Dye JM, Voss JE, Gunn BM, McLellan JS, Baric RS, Gralinski LE, Walker LM, Broad and potent activity against SARS-like viruses by an engineered human monoclonal antibody. Science. 371, 823–829 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wec AZ, Wrapp D, Herbert AS, Maurer DP, Haslwanter D, Sakharkar M, Jangra RK, Dieterle ME, Lilov A, Huang D, Tse LV, Johnson NV, Hsieh CL, Wang N, Nett JH, Champney E, Burnina I, Brown M, Lin S, Sinclair M, Johnson C, Pudi S, Bortz R, Wirchnianski AS, Laudermilch E, Florez C, Fels JM, O’Brien CM, Graham BS, Nemazee D, Burton DR, Baric RS, Voss JE, Chandran K, Dye JM, McLellan JS, Walker LM, Broad neutralization of SARS-related viruses by human monoclonal antibodies. Science (2020), doi: 10.1126/science.abc7424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park Y-J, De Marco A, Starr TN, Liu Z, Pinto D, Walls AC, Zatta F, Zepeda SK, Bowen JE, Sprouse KR, Joshi A, Giurdanella M, Guarino B, Noack J, Abdelnabi R, Foo S-YC, Rosen LE, Lempp FA, Benigni F, Snell G, Neyts J, Whelan SPJ, Virgin HW, Bloom JD, Corti D, Pizzuto MS, Veesler D, Antibody-mediated broad sarbecovirus neutralization through ACE2 molecular mimicry. Science, eabm8143 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowen JE, Walls AC, Joshi A, Sprouse KR, Stewart C, Alejandra Tortorici M, Franko NM, Logue JK, Mazzitelli IG, Tiles SW, Ahmed K, Shariq A, Snell G, Iqbal NT, Geffner J, Bandera A, Gori A, Grifantini R, Chu HY, Van Voorhis WC, Corti D, Veesler D, SARS-CoV-2 spike conformation determines plasma neutralizing activity. bioRxiv (2021), p. 2021.12.19.473391, , doi: 10.1101/2021.12.19.473391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corti D, Purcell LA, Snell G, Veesler D, Tackling COVID-19 with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Cell (2021), doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tada T, Dcosta BM, Samanovic MI, Herati RS, Cornelius A, Zhou H, Vaill A, Kazmierski W, Mulligan MJ, Landau NR, Convalescent-phase Sera and vaccine-elicited antibodies largely maintain neutralizing titer against global SARS-CoV-2 variant spikes. MBio. 12, e0069621 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan M, Huang D, Lee C-CD, Wu NC, Jackson AM, Zhu X, Liu H, Peng L, van Gils MJ, Sanders RW, Burton DR, Reincke SM, Prüss H, Kreye J, Nemazee D, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Structural and functional ramifications of antigenic drift in recent SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science (2021), doi: 10.1126/science.abh1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, Iketani S, Luo Y, Guo Y, Wang M, Yu J, Zhang B, Kwong PD, Graham BS, Mascola JR, Chang JY, Yin MT, Sobieszczyk M, Kyratsous CA, Shapiro L, Sheng Z, Huang Y, Ho DD, Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Addetia A, Hannon WW, Choudhary MC, Dingens AS, Li JZ, Bloom JD, Prospective mapping of viral mutations that escape antibodies used to treat COVID-19. Science. 371, 850–854 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, Shan S, Zhou H, Fan S, Zhang Q, Shi X, Wang Q, Zhang L, Wang X, Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature (2020), doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toelzer C, Gupta K, Yadav SKN, Borucu U, Davidson AD, Kavanagh Williamson M, Shoemark DK, Garzoni F, Staufer O, Milligan R, Capin J, Mulholland AJ, Spatz J, Fitzgerald D, Berger I, Schaffitzel C, Free fatty acid binding pocket in the locked structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science. 370, 725–730 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu X, Mannar D, Srivastava SS, Berezuk AM, Demers J-P, Saville JW, Leopold K, Li W, Dimitrov DS, Tuttle KS, Zhou S, Chittori S, Subramaniam S, Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the N501Y SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in complex with ACE2 and 2 potent neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001237 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomson EC, Rosen LE, Shepherd JG, Spreafico R, da Silva Filipe A, Wojcechowskyj JA, Davis C, Piccoli L, Pascall DJ, Dillen J, Lytras S, Czudnochowski N, Shah R, Meury M, Jesudason N, De Marco A, Li K, Bassi J, O’Toole A, Pinto D, Colquhoun RM, Culap K, Jackson B, Zatta F, Rambaut A, Jaconi S, Sreenu VB, Nix J, Zhang I, Jarrett RF, Glass WG, Beltramello M, Nomikou K, Pizzuto M, Tong L, Cameroni E, Croll TI, Johnson N, Di Iulio J, Wickenhagen A, Ceschi A, Harbison AM, Mair D, Ferrari P, Smollett K, Sallusto F, Carmichael S, Garzoni C, Nichols J, Galli M, Hughes J, Riva A, Ho A, Schiuma M, Semple MG, Openshaw PJM, Fadda E, Baillie JK, Chodera JD, ISARIC4C Investigators, COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium, Rihn SJ, Lycett SJ, Virgin HW, Telenti A, Corti D, Robertson DL, Snell G, Circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike N439K variants maintain fitness while evading antibody-mediated immunity. Cell. 184, 1171–1187.e20 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Hilton SK, Ellis D, Crawford KHD, Dingens AS, Navarro MJ, Bowen JE, Tortorici MA, Walls AC, King NP, Veesler D, Bloom JD, Deep Mutational Scanning of SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain Reveals Constraints on Folding and ACE2 Binding. Cell. 182, 1295–1310.e20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shuai H, Chan JF-W, Yuen TT-T, Yoon C, Hu J-C, Wen L, Hu B, Yang D, Wang Y, Hou Y, Huang X, Chai Y, Chan CC-S, Poon VK-M, Lu L, Zhang R-Q, Chan W-M, Ip JD, Chu AW-H, Hu Y-F, Cai J-P, Chan K-H, Zhou J, Sridhar S, Zhang B-Z, Yuan S, Zhang AJ, Huang J-D, To KK-W, Yuen K-Y, Chu H, Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants expand species tropism to murines. EBioMedicine. 73, 103643 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan T, Chen R, He X, Yuan Y, Deng X, Li R, Yan H, Yan S, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yu F, Zhou M, Ke C, Ma X, Zhang H, Infection of wild-type mice by SARS-CoV-2 B.1.351 variant indicates a possible novel cross-species transmission route. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6, 420 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffmann M, Krüger N, Schulz S, Cossmann A, Rocha C, Kempf A, Nehlmeier I, Graichen L, Moldenhauer A-S, Winkler MS, Lier M, Dopfer-Jablonka A, Jäck H-M, Behrens GMN, Pöhlmann S, The Omicron variant is highly resistant against antibody-mediated neutralization – implications for control of the COVID-19 pandemic. bioRxiv (2021), , doi: 10.1101/2021.12.12.472286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leist SR, Dinnon KH 3rd, Schäfer A, Tse LV, Okuda K, Hou YJ, West A, Edwards CE, Sanders W, Fritch EJ, Gully KL, Scobey T, Brown AJ, Sheahan TP, Moorman NJ, Boucher RC, Gralinski LE, Montgomery SA, Baric RS, A Mouse-Adapted SARS-CoV-2 Induces Acute Lung Injury and Mortality in Standard Laboratory Mice. Cell. 183, 1070–1085.e12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisblum Y, Schmidt F, Zhang F, DaSilva J, Poston D, Lorenzi JCC, Muecksch F, Rutkowska M, Hoffmann H-H, Michailidis E, Gaebler C, Agudelo M, Cho A, Wang Z, Gazumyan A, Cipolla M, Luchsinger L, Hillyer CD, Caskey M, Robbiani DF, Rice CM, Nussenzweig MC, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD, Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. Elife. 9, e61312 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walls AC, Miranda MC, Schäfer A, Pham MN, Greaney A, Arunachalam PS, Navarro M-J, Tortorici MA, Rogers K, O’Connor MA, Shirreff L, Ferrell DE, Bowen J, Brunette N, Kepl E, Zepeda SK, Starr T, Hsieh C-L, Fiala B, Wrenn S, Pettie D, Sydeman C, Sprouse KR, Johnson M, Blackstone A, Ravichandran R, Ogohara C, Carter L, Tilles SW, Rappuoli R, Leist SR, Martinez DR, Clark M, Tisch R, O’Hagan DT, Van Der Most R, Van Voorhis WC, Corti D, McLellan JS, Kleanthous H, Sheahan TP, Smith KD, Fuller DH, Villinger F, Bloom J, Pulendran B, Baric R, King NP, Veesler D, Elicitation of broadly protective sarbecovirus immunity by receptor-binding domain nanoparticle vaccines. Cell (2021), doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walls AC, Fiala B, Schäfer A, Wrenn S, Pham MN, Murphy M, Tse LV, Shehata L, O’Connor MA, Chen C, Navarro MJ, Miranda MC, Pettie D, Ravichandran R, Kraft JC, Ogohara C, Palser A, Chalk S, Lee EC, Guerriero K, Kepl E, Chow CM, Sydeman C, Hodge EA, Brown B, Fuller JT, Dinnon KH, Gralinski LE, Leist SR, Gully KL, Lewis TB, Guttman M, Chu HY, Lee KK, Fuller DH, Baric RS, Kellam P, Carter L, Pepper M, Sheahan TP, Veesler D, King NP, Elicitation of Potent Neutralizing Antibody Responses by Designed Protein Nanoparticle Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 183, 1367–1382.e17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arunachalam PS, Walls AC, Golden N, Atyeo C, Fischinger S, Li C, Aye P, Navarro MJ, Lai L, Edara VV, Röltgen K, Rogers K, Shirreff L, Ferrell DE, Wrenn S, Pettie D, Kraft JC, Miranda MC, Kepl E, Sydeman C, Brunette N, Murphy M, Fiala B, Carter L, White AG, Trisal M, Hsieh C-L, Russell-Lodrigue K, Monjure C, Dufour J, Spencer S, Doyle-Meyer L, Bohm RP, Maness NJ, Roy C, Plante JA, Plante KS, Zhu A, Gorman MJ, Shin S, Shen X, Fontenot J, Gupta S, O’Hagan DT, Van Der Most R, Rappuoli R, Coffman RL, Novack D, McLellan JS, Subramaniam S, Montefiori D, Boyd SD, Flynn JL, Alter G, Villinger F, Kleanthous H, Rappaport J, Suthar MS, King NP, Veesler D, Pulendran B, Adjuvanting a subunit COVID-19 vaccine to induce protective immunity. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martinez DR, Schäfer A, Leist SR, De la Cruz G, West A, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Lindesmith LC, Pardi N, Parks R, Barr M, Li D, Yount B, Saunders KO, Weissman D, Haynes BF, Montgomery SA, Baric RS, Chimeric spike mRNA vaccines protect against Sarbecovirus challenge in mice. Science (2021), doi: 10.1126/science.abi4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen AA, Gnanapragasam PNP, Lee YE, Hoffman PR, Ou S, Kakutani LM, Keeffe JR, Wu H-J, Howarth M, West AP, Barnes CO, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ, Mosaic nanoparticles elicit cross-reactive immune responses to zoonotic coronaviruses in mice. Science. 371, 735–741 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suloway C, Pulokas J, Fellmann D, Cheng A, Guerra F, Quispe J, Stagg S, Potter CS, Carragher B, Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J. Struct. Biol 151, 41–60 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tegunov D, Cramer P, Real-time cryo-electron microscopy data preprocessing with Warp. Nat. Methods 16, 1146–1152 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA, cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zivanov J, Nakane T, Forsberg BO, Kimanius D, Hagen WJ, Lindahl E, Scheres SH, New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife. 7 (2018), doi: 10.7554/eLife.42166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scheres SH, RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol 180, 519–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Punjani A, Zhang H, Fleet DJ, Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat. Methods 17, 1214–1221 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zivanov J, Nakane T, Scheres SHW, A Bayesian approach to beam-induced motion correction in cryo-EM single-particle analysis. IUCrJ. 6, 5–17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenthal PB, Henderson R, Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol 333, 721–745 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen S, McMullan G, Faruqi AR, Murshudov GN, Short JM, Scheres SH, Henderson R, High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 135, 24–35 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE, UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K, Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang RY, Song Y, Barad BA, Cheng Y, Fraser JS, DiMaio F, Automated structure refinement of macromolecular assemblies from cryo-EM maps using Rosetta. Elife. 5 (2016), doi: 10.7554/eLife.17219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frenz B, Rämisch S, Borst AJ, Walls AC, Adolf-Bryfogle J, Schief WR, Veesler D, DiMaio F, Automatically Fixing Errors in Glycoprotein Structures with Rosetta. Structure. 27, 134–139.e3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liebschner D, Afonine PV, Baker ML, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Croll TI, Hintze B, Hung LW, Jain S, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner RD, Poon BK, Prisant MG, Read RJ, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, Sammito MD, Sobolev OV, Stockwell DH, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev AG, Videau LL, Williams CJ, Adams PD, Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 75, 861–877 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Croll TI, ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 74, 519–530 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 12–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barad BA, Echols N, Wang RY, Cheng Y, DiMaio F, Adams PD, Fraser JS, EMRinger: side chain-directed model and map validation for 3D cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 12, 943–946 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agirre J, Iglesias-Fernández J, Rovira C, Davies GJ, Wilson KS, Cowtan KD, Privateer: software for the conformational validation of carbohydrate structures. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 22, 833–834 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Morris JH, Ferrin TE, UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ, Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr 40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Murshudov GN, Skubák P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA, REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 67, 355–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.