Abstract

Skin stem cells have an essential role in maintaining tissue homeostasis by dynamically replenishing those constantly lost during tissue turnover or following injury. Multipotent skin derived progenitors (SKP) can generate both neural and mesodermal progeny, representing neural crest-derived progenitors during embryogenesis through adulthood. SKP cells develop into spheres in suspension and can differentiate into fibroblast-like cells (SFC) in adhesive culture with serum. Concomitantly they gradually lose the neural potential but retain certain mesodermal potential. However, little is known about the molecular mechanism of the transition of SKP spheres into SFC in vitro. Here we characterized the transcriptional profiles of porcine SKP spheres and SFC by microarray analysis. We found 305 up-regulated and 96 down-regulated genes, respectively. The down-regulated genes are mostly involved in intrinsic programs like the Dicer pathway and asymmetric cell division; whereas up-regulated genes are likely to participate in extrinsic signaling pathways such as ErbB signaling, MAPK signaling, ECM-receptor reaction, Wnt signaling, cell communication and TGF-beta signaling pathways. These intrinsic programs and extrinsic signaling pathways collaborate to mediate the transcription-state transition between SKP spheres and SFC. We speculate that these potential signaling pathways may play an important role in regulating the cell fate transition between SKP spheres and SFC in vitro.

Introduction

Skin derived progenitor (SKP) from mammalian dermis can differentiate into cells of both neural and mesodermal lineages, such as neurons, glias, smooth muscle cells and adipocytes (Dyce et al., 2004; Fernandes et al., 2004; Toma et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2009). SKP cells which exhibit similar characteristics of embryonic neural crest stem cells can develop into neurosphere-like morphology in suspension culture, and can be passaged for one year without losing their multiple differentiation potential (Fernandes et al., 2004; Toma et al., 2001). However, SKP spheres initiate differentiation when they attach onto the culture dishes by serum. After the attachment, they develop into a fibroblast-like morphology which is similar to that of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (Pittenger et al., 1999). During this process SKP cells gradually loss their neural potency but retain their mesodermal potency and can be induced into smooth muscle cells and adipocytes (Fernandes et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2009). Comparatively, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can differentiate into various cell types in vitro and in vivo, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, myocytes and adipocytes (Pittenger et al., 1999); although the pluripotency of MSCs has still been controversial (Jiang et al., 2002; Terada et al., 2002; Ying et al., 2002). It has been reported that dermal skin-derived fibroblasts have the capacity to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, myogenic and adipogenic lineages, showing characteristics similar to MSC (Crigler et al., 2007; Lorenz et al., 2008). In addition, several other multipotent dermis-derived stem cells have been identified by using different culture systems, implying the prospective therapeutic applications since skin is easily accessible for autologous transplantation (Bartsch et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2007). These findings support a view that multipotent stem cells can be isolated from dermal skin although they display different characteristics in response to various extrinsic stimuli.

There is still a debate about the plasticity of adult stem cells (Wagers and Weissman, 2004). The extrinsic environment plays an important role in defining the stem-cell niches during embryonic development; whereas intrinsic programs which determine the transcriptional state of stem cells may be adjusted to lineage commitment in response to extrinsic signaling (Albert and Peters, 2009; Arnold and Robertson, 2009). To some extent, in vitro culture conditions sometimes alter the behavior of stem cells by modifying their fates and even their developmental potentials (Joseph and Morrison, 2005). This idea has been further confirmed by reprogramming differentiated cells back into a pluripotent stem cell state either by ectopic expression of specific transcription factors or using recombinant proteins in vitro (Kim et al., 2009a; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Zhou et al., 2009). Thus, it seems as if the extrinsic stimulus would alter the developmental potential of SKP cells in vitro through a shift of transcriptional states.

Genome-wide transcriptional profiling has become a routine assay with the development of microarray technology (Hoheisel, 2006). Transcriptional profiling of multipotent stem/progenitor cells has been extensively investigated on embryonic stem cells (Ivanova et al., 2002; Ramalho-Santos et al., 2002), neural stem cells (Maisel et al., 2007; Shin et al., 2007), hematopoietic stem cells (Kiel et al., 2005; Terskikh et al., 2003), MSCs (Song et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2005) and epithelial stem cells (Tumbar et al., 2004) by microarray technology. Nevertheless, the transcriptional program of multipotent skin-derived stem cells such as SKP cells has yet to be determined. Moreover, the comparison of the molecular signatures between SKP and other skin-derived progenitor cells remains an open question. Hence, the aim of this study is to compare the transcriptional programs between SKP spheres and SKP-derived fibroblast-like cells (SFC) by microarray analysis. We assume that the individually transcriptional states may be established in specific microenvironment by SKP spheres and SFC, which can be regulated and maintained through divergent signaling pathways. This would help to explain the molecular mechanisms of neural and mesodermal potential of SKP cells, thus accelerating the therapeutic application of skin-derived stem cells.

Methods & Materials

Animal use and care have been reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) at University of Missouri-Columbia.

Cell isolation and cultures

Chemicals and components were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless indicated otherwise.

The isolation of porcine SKP spheres was described elsewhere (Zhao et al., 2009). Briefly, back skin tissue was peeled off from day 40–50 pCAG-EGFP transgenic porcine fetuses in a sterile hood (Whitworth et al., 2009). The tissues were washed with D-PBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) three times and chopped up into small pieces. Then the tissue was digested by 0.1 % trypsin for 20–40 min at 37°C. Afterward 1 mL of 0.1% DNase I was added and incubated for 1 min at room temperature (RT). The enzymatic activity of trypsin was counteracted with neutralization solution (DMEM/F12 (1:1, Invitrogen) + 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA)) and the cells were washed three times with DMEM/F12 medium. The cells were subsequently dissociated and poured through a 40 μm strainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The dissociated cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended with standard culture medium containing DMEM/F12 (1:1), B27 (50×, Invitrogen), 20 ng/mL EGF and 40 ng/mL bFGF. After 3 d culture in suspension dishes (Sarstedt, Newton, NC, USA), an appropriate volume of culture medium with 2×growth factor and supplements was added to complement the depletion. The SKP spheres appeared in 5–7 d and were harvested for RNA isolation or stored in liquid nitrogen.

For SFC derivation, SKP spheres were collected and resuspended by induction medium (DEME (Invitrogen) + 15% FBS + 20 ng/ml EGF) and plated onto a 24-well cell culture cluster (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA). The SFCs were cultured for 3 d and recovered by 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen). The trypsin was neutralized by 3X volumes of induction medium and the cells were collected. The SKP-derived fibroblast-like cells were immediately frozen for RNA isolation or stored in liquid nitrogen.

Immunocytochemistry

Cell cultures were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min. The fixed cells were blocked with PBS/10% FBS for 2 h and subsequently incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS/10%FBS, they were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. Finally they were incubated with Hoechst 33342 for 15 min. A parallel culture only with secondary antibody was employed as a negative control and culture without any antibody was used as a blank control. Primary antibodies were monoclonal anti-fibronectin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; 1:200), monoclonal anti-vimentin (Abcam, 1:200), monoclonal anti-GFAP (Sigma, 1:250), monoclonal anti-tubulin β-III (Sigma, 1:250), monoclonal anti-NFM (Abcam, 1:100), monoclonal anti-p75NTR (Abcam, 1:100). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor® 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen, 1:500). The images were captured by DS Camera Control Unit DS-U2 (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA) and processed by using the NIS-Elements imaging software (Nikon). Each slide for immunocytochemistry was independently repeated 3 times.

RNA isolation and amplification

Total RNA was extracted by using an AllPrep DNA/RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and measured by a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). The RNA amplification was performed by WT-Ovation Pico RNA amplification system (NuGEN, San Carlos, CA, USA) with the input of 5 ng of RNA. The amplified cDNA was purified by Micro Bio-Spin 30 Columns in RNase-Free Tris (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The purified cDNA was aliquoted into 1 μg per vial and stored at −8°C.

Reference RNA (Ref RNA) preparation

The porcine Ref RNA was created by isolating total RNA from a large representation of non-reproductive and reproductive tissues across different developmental stages (Whitworth et al., 2005). Ref RNA was reverse transcribed by SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) and purified by Micro Bio-Spin 30 Columns in RNase-Free Tris. The purified Ref cDNA was aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

cDNA microarray preparation

The cDNA microarray platform was established at the University of Missouri-Columbia (Agca et al., 2006; Green et al., 2006; Whitworth et al., 2004; Whitworth et al., 2005). The general information of EST clones can be browsed at http://genome.rnet.missouri.edu/Swine/.

Labeling and hybridization

The starting amount of purified Ref cDNA or amplified cDNA sample was 1 μg. The amplified cDNA samples were labeled with Cy5 (ULYSIS Alexa Fluor 647 Nucleic Acid Labeling Kits, Invitrogen) and Ref cDNA was labeled with Cy3 (ULYSIS Alexa Fluor 546 Nucleic Acid Labeling Kits, Invitrogen). After labeling and purification, NanoDrop readings were processed to calculate the degree of labeling (DoL, http://www.kreatech.com/Default.aspx?tabid=121) and to validate that labeling efficiency was within the recommended range of 1–3.6%. Then the Cy5 labeled samples and Cy3 labeled Ref cDNA were combined together and dried in a CentriVap Concentrator system. The labeled cDNA were resuspended with hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 0.1% SDS and 5XSSC) and blocked with 1 μl of 20 ng/μl polyA (20 mers) to prevent hybridization to the 3′ end of the ESTs. Then they were denatured at 95°C for 3 min and cooled at RT. The labeled cDNA was subsequently applied from one end to the arrays and incubated at 42°C for 16 h with gentle shaking.

Microarray Replicates

Each biological replicate consisted of RNA from 1×105 cells of SKP spheres or SFCs, which were derived from the pools of two different fetuses either in the same litters or different litters. Each biological replicate was analyzed on two microarrays, resulting in three biological replicates and two technical replicates, i.e. six microarray measurements.

Wash and Scan arrays

After hybridization, the arrays were washed with washing solution I (2XSSC/0.1%SDS) twice, washing solution II (0.1XSSC/0.1%SDS) once and washing solution III (0.1XSSC), each of which was kept on a shaker for 4 min covered with foil to avoid light. The slides were then shifted into 95% ethanol for a few seconds and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min. Subsequently the arrays were scanned by GenePix 4000B (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The PMTs for wave length 532 and 653 were adjusted appropriately to ensure that the count ratio of Cy3 to Cy5 is 1.0. The images were visualized by GenePix Pro 4.1 (Molecular Devices) to assess the spot quality. The proper gene array list was loaded and poor-quality spots (smeared or saturated) were flagged manually. Then the raw data were generated as input for further analysis.

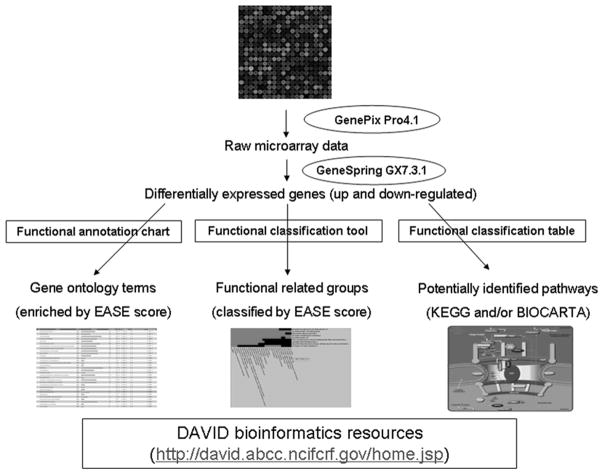

Data analysis by GeneSpring GX 7.3.1

The general strategy for microarray data analysis is outlined in Fig. 1. The raw data were uploaded into GeneSpring GX 7.3.1 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The spots were filtered to remove those whose raw intensities were close to background and not reliable. One-way ANOVA was performed by using a parametric test with variances not assumed equal (Welch t-test) and p value cutoff of 0.05.

Figure 1.

The strategy used for microarray data analysis: finding potential pathways.

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) analysis

The online DAVID (sixth version, 2008) was employed to perform functional annotation analysis (Dennis et al., 2003; Huang da et al., 2009). The up-regulated and down-regulated gene lists were submitted and converted into DAVID IDs. Subsequently the uploaded DAVID lists were subject to Functional Annotation Clustering, which uses fuzzy clustering by measuring the relationships among the annotation terms on the basis of the degree of their co-association with genes within the user’s list to cluster somewhat heterogeneous, yet highly similar annotation into functional annotation groups. A higher enriched score indicates that the gene members in the groups are involved in more important roles, which can be visualized by a 2D view tool. Gene Functional Classification Tool was used to group genes based on functional similarity, displaying with group enrichment scores according to overall EASE scores of all enriched annotation terms. The Functional Annotation Chart shows the enriched gene ontology terms associated with input genes which pass the threshold of EASE score (P value≤0.05). In addition, the related KEGG pathways or BIOCARTA pathways can be found in Functional Annotation Tables.

Real time qPCR validation

Six genes were selected to verify the microarray data. The primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Skokie, IL, USA). Real time qPCR was carried out by using Power SYBR Master Mix in ABI Prism 7500 real time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The expression levels were normalized by a relative standard curve method. Gradient dilutions (1/10X) of Ref cDNA were used for creating standard curves. The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as a calibrator gene. The real time qPCR data were obtained from three independent biological replicates and two technical replicates and analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

Results

Characterization of porcine SKP spheres and SFC cells in vitro

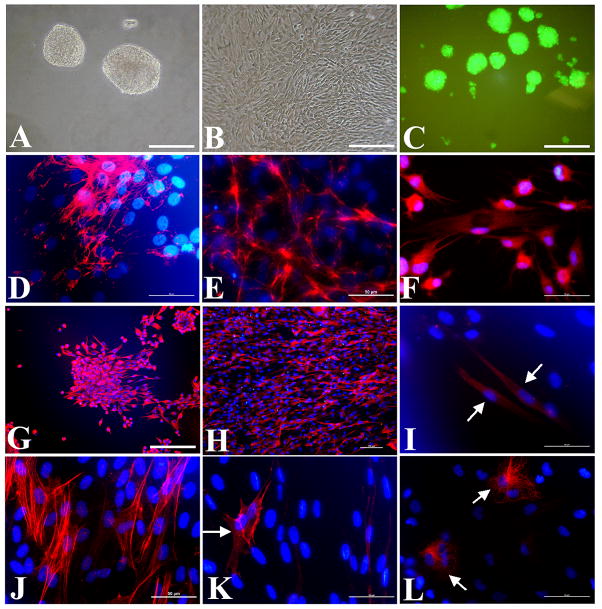

The porcine SKP cells developed into sphere-like structure in suspension cultures (Fig. 2A, C), which is quite different from the colonies of keratinocytes on feeder cells (Rheinwald and Green, 1975). However, they attached onto the bottom and exhibited fibroblast-like morphology when exposed to serum and tissue culture treated dishes (Fig. 2B). Both porcine SKP spheres and SFC can express fibronectin and vimentin (Fig. 2D, E, G, H) when measured by immunocytochemistry, similar to that of human adherent SKP cells (Toma et al., 2005) but distinct from that of rodent SKP cells (Toma et al., 2001). Smooth muscle actin (SMA) can be detected in SFC cultures (Fig. 2J) rather than SKP spheres, although SMA positive cells appeared during the differentiation of SKP spheres (Fig. 2K). After differentiation, SKP spheres could generate tubulin β-III positive (Fig. 2F) cells, GFAP positive (Fig. 2I) cells, and neurofilament M (Fig. 2L) positive cells, indicating the neural potential of SKP cells in vitro (Zhao et al., 2009). However, these neural progeny did not appear in induced SFC cultures (data not shown). This suggests the loss of neural potential for SFC, which is inconsistent with neurogenic differentiation potency of human nestin negative vimentin positive dermal fibroblast clones (Chen et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Characterization of porcine SKP spheres and SFC cells in vitro. Typical SKP spheres (A) and SFC (B) under phase contrast, and EGFP SKP spheres under fluorescence (C) are shown. Both SKP spheres and SFC cells expressed fibronectin and vimentin: (D-E) the merged images of anti-fibronectin and Hoechst 33342 staining for SKP spheres (D) and SFC (E); (G-H) the overlay of anti-vimentin and Hoechst 33343 staining for SKP spheres (G) and SFC (H). The multiple-lineage differentiation of SKP spheres was shown (F, I, K, L). SKP sphere derived progeny were immunostained with monoclonal antibodies against tubulin β-III (F), GFAP (I), SMA (K), NFM (L) and the nuclei were stained by Hoechst 33342. However, SMA positive cells (J) were also present in SFC cultures. Scale bars, 50 μm (D-F, I-L); 100 μm (H); 200 μm (A-C, G).

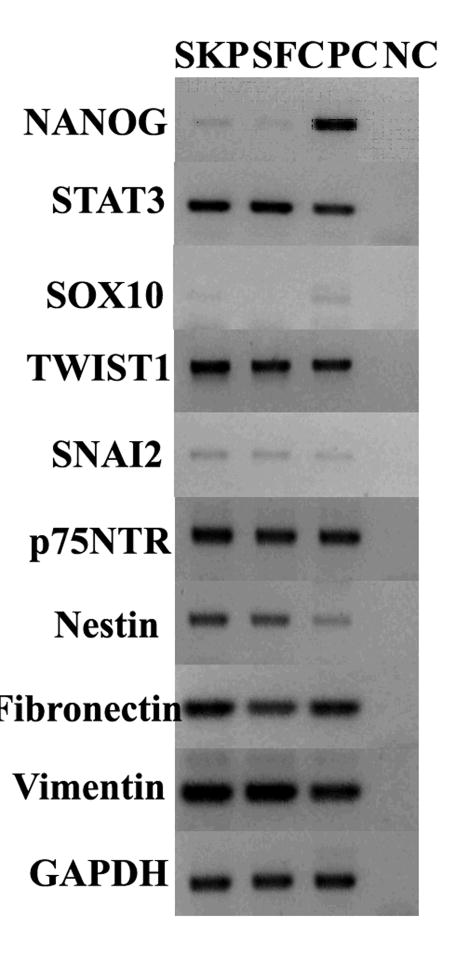

Next we compared the marker gene expression between porcine SKP spheres and SFC. We observed a similar pattern of marker gene expression between the two (Fig 3), such as embryonic stem (ES) cell marker NANOG (Chambers et al., 2007; Mitsui et al., 2003), STAT3 (Niwa et al., 1998) and neural crest cell marker TWIST1, SNAI2 and p75NTR (Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser, 2008). Nevertheless, SOX10 was exclusively expressed in SKP rather than in SFC although SOX10 mRNA signal is faint in SKP spheres (Kim et al., 2003). In addition, the expression of fibronectin and vimentin was confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Fig 2D, E, G, H). These results show similar marker gene expression patterns between SKP and SFC but they display differential differentiation potential. Together, we demonstrate the neural and mesodermal potency of SKP spheres in vitro. During the transition between SKP spheres into SFC, neural potential is gradually lost but mesodermal potential is still retained in SFC.

Figure 3.

Marker gene expression between SKP spheres and SFC. The Ref cDNA was used as the template for the positive control (PC), whereas no RT was used as the negative control (NC). The RT-PCR was replicated by 3 biological samples and only one was shown. The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Functional annotation clustering of up-regulated genes

Since SFC cells were derived from SKP, they should have the same genetic background with low transcriptional noise. We only used the signals with the intensity of 1500 to 60000 in the raw and control data as determined by GeneSpring GX 7.3.1. Totally there were 401 differentially expressed genes between SKP and SFC (P value≤0.05), of which 305 genes were up-regulated compared with those expression levels of SKP. The up-regulated gene lists were submitted and converted into 188 DAVID IDs. The gene ontology (GO) terms of up-regulated genes are listed in Table 1 with P-value cutoff 0.05. Most of up-regulated genes have the terms of binding, cellular process and metabolic process (Table 1). Furthermore these genes were functionally clustered into 10 groups by enrichment scores (Table 2): cellular protein metabolic process (4.97), nucleotide binding (2.49), response to protein stimulus (2.14), cellular catabolic process (1.53), transmembrane (1.33), ribonucleotide binding (1.3), RNA metabolic process (1.17), plasma membrane (0.93), protein modification (0.88), regulation of transcription (0.38). The up-regulation of 10 clusters may coincide with cellular state transition of SKP spheres into SFC when cells acquire a strong potential of proliferation.

Table 1.

Gene ontology terms of up-regulated genes between SKP and SFC (Count ≥10, P value ≤0.05). The “count” indicates the number of the genes involved in the term. The smaller P-value (EASE score) is, the more enriched (188 DAVID IDs).

| Term | Count | Percent (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct protein sequencing | 56 | 29.8 | 7.4E-12 |

| acetylation | 27 | 14.4 | 8.4E-12 |

| cytoplasm | 95 | 50.5 | 2.0E-10 |

| Intracellular part | 122 | 64.9 | 1.0E-8 |

| ribonucleoprotein | 16 | 8.5 | 1.7E-8 |

| Ribosomal protein | 14 | 7.4 | 3.6E-8 |

| Cytoplasmic part | 64 | 34.0 | 5.5E-8 |

| Structural molecular activity | 27 | 14.4 | 6.5E-8 |

| Intracellular | 125 | 66.5 | 6.6E-8 |

| Macromolecular complex | 50 | 26.6 | 1.8E-7 |

| Ribosomal subunit | 11 | 5.9 | 6.2E-7 |

| Cellular biosynthetic process | 29 | 15.4 | 1.1E-6 |

| Structural constituent of ribosome | 14 | 7.4 | 3.1E-6 |

| Intracellular organelle part | 57 | 30.3 | 3.4E-6 |

| translation | 20 | 10.6 | 3.5E-6 |

| Organelle part | 57 | 30.3 | 3.8E-6 |

| Intracellular organelle | 103 | 54.8 | 3.9E-6 |

| organelle | 103 | 54.8 | 4.0E-6 |

| Biosynthetic process | 33 | 17.6 | 4.2E-6 |

| Intracellular non-membrane-bound organelle | 38 | 20.2 | 8.7E-6 |

| non-membrane-bound organelle | 38 | 20.2 | 8.7E-6 |

| ribosome | 14 | 7.4 | 9.0E-6 |

| Ribonucleoprotein complex | 18 | 9.6 | 2.3E-5 |

| Protein binding | 89 | 47.3 | 3.2E-5 |

| mitochondrion | 23 | 12.2 | 5.6E-5 |

| cytosol | 16 | 8.5 | 8.5E-5 |

| phosphoprotein | 63 | 33.5 | 8.9E-5 |

| Protein complex | 37 | 19.7 | 1.1E-5 |

| Macromolecule biosynthetic process | 21 | 11.2 | 1.9E-5 |

| Protein dimerization activity | 11 | 5.9 | 6.5E-4 |

| Organelle lumen | 20 | 10.6 | 8.0E-4 |

| Membrane-enclosed lumen | 20 | 10.6 | 8.0E-4 |

| RNA binding | 17 | 9.0 | 9.6E-4 |

| Mitochondrial part | 14 | 7.4 | 9.7E-4 |

| Primary metabolic process | 93 | 49.5 | 1.6E-3 |

| Transit peptide | 11 | 5.9 | 2.6E-3 |

| cytoskeleton | 21 | 11.2 | 3.4E-3 |

| Cell part | 144 | 76.6 | 3.5E-3 |

| Cell | 144 | 76.6 | 3.6E-3 |

| Localization | 43 | 22.9 | 3.9E-3 |

| Intracellular membrane-bound organelle | 82 | 43.6 | 5.4E-3 |

| membrane-bound organelle | 82 | 43.6 | 5.5E-3 |

| Cellular metabolic process | 90 | 47.9 | 7.0E-3 |

| Nuclear part | 19 | 10.1 | 7.6E-3 |

| Organelle organization and biogenesis | 20 | 10.6 | 1.1E-2 |

| Cellular process | 127 | 67.6 | 1.3E-2 |

| Gene expression | 46 | 24.5 | 1.3E-2 |

| binding | 127 | 67.6 | 1.4E-2 |

| Establishment of localization | 36 | 19.1 | 2.1E-2 |

| transport | 35 | 18.6 | 2.2E-2 |

| Cell proliferation | 14 | 7.4 | 2.7E-2 |

| Nucleotide binding | 21 | 11.2 | 2.9E-2 |

| Cytoskeletal part | 13 | 6.9 | 3.1E-2 |

| Organelle envelope | 11 | 5.9 | 3.1E-2 |

| envelop | 11 | 5.9 | 3.2E-2 |

| Protein metabolic process | 44 | 23.4 | 3.3E-2 |

| Regulation of cell proliferation | 10 | 5.3 | 3.6E-2 |

| Metabolic process | 94 | 50.0 | 3.9E-2 |

| Cellular macromolecule metabolic process | 42 | 22.3 | 4.1E-2 |

| Biological adhesion | 13 | 6.9 | 4.6E-2 |

| Cell adhesion | 13 | 6.9 | 4.6E-2 |

| Cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 10 | 5.3 | 4.8E-2 |

| Cellular protein metabolic process | 41 | 21.8 | 5.0E-2 |

Table 2.

Gene functional classification of up-regulated genes in SKF compared with those of SKP spheres (10 clusters).

| Functional Cluster | Enrichment Score | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular protein metabolic process | 4.97 | ribosomal protein sa, mitochondrial ribosomal protein l13, mitochondrial ribosomal protein l23, ribosomal protein l11, mitochondrial ribosomal protein s15, ribosomal protein s5, ribosomal protein l38, mitochondrial ribosomal protein s25, ribosomal protein l24, ribosomal protein l22, ribosomal protein l27, ribosomal protein s13, mitochondrial ribosomal protein l48, mitochondrial translational initiation factor 3, mitochondrial ribosomal protein l37 |

| Nucleotide binding | 2.49 | sar1 gene homolog a (s. cerevisiae), heat shock 70kda protein 8, tubulin, alpha, ubiquitous, eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1 |

| Response to protein stimulus | 2.14 | heat shock 60kda protein 1 (chaperonin), heat shock 10kda protein 1 (chaperonin 10), heat shock 70kda protein 8, heat shock protein 90kda alpha (cytosolic), class a member 1 |

| Cellular catabolic process | 1.53 | ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase l1 (ubiquitin thiolesterase), proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type, 6, proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, alpha type, 7, dcp1 decapping enzyme homolog a (s. cerevisiae) |

| Transmembrane | 1.33 | bmp and activin membrane-bound inhibitor homolog (xenopus laevis), solute carrier family 33 (acetyl-coa transporter), member 1, aquaporin 1 (colton blood group), tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 1 |

| Ribonucleotide binding | 1.3 | dead (asp-glu-ala-asp) box polypeptide 18, heat shock 70kda protein 8, mcm8 minichromosome maintenance deficient 8 (s. cerevisiae), dead (asp-glu-ala-asp) box polypeptide 55 |

| RNA metabolic process | 1.17 | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein h3 (2h9), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein r, rod1 regulator of differentiation 1 (s. pombe), cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 3, 73kda |

| Plasma membrane | 0.93 | atpase, na+/k+ transporting, beta 3 polypeptide, solute carrier family 33 (acetyl-coa transporter), member 1, solute carrier family 12 (potassium/chloride transporters), member 4, solute carrier family 23 (nucleobase transporters), member 2 |

| Protein modification | 0.88 | casein kinase 1, alpha 1, v-mos moloney murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog, discoidin domain receptor family, member 1, ptk9 protein tyrosine kinase 9 |

| Regulation of transcription | 0.38 | sry (sex determining region y)-box 9 (campomelic dysplasia, autosomal sex-reversal), hypoxia-inducible factor 1, alpha subunit (basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor), mcm8 minichromosome maintenance deficient 8 (s. cerevisiae), taf5 rna polymerase ii, tata box binding protein (tbp)-associated factor, 100kda, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 1, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2, pc4 and sfrs1 interacting protein 1, camp responsive element binding protein-like 2, chromosome 20 open reading frame 17, suppressor of ty 6 homolog (s. cerevisiae), rrn3 rna polymerase i transcription factor homolog (yeast), phd finger protein 23, ets homologous factor, nuclear factor of activated t-cells 5, tonicity-responsive, hypothetical protein bm-005, nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group c, member 1 (glucocorticoid receptor) |

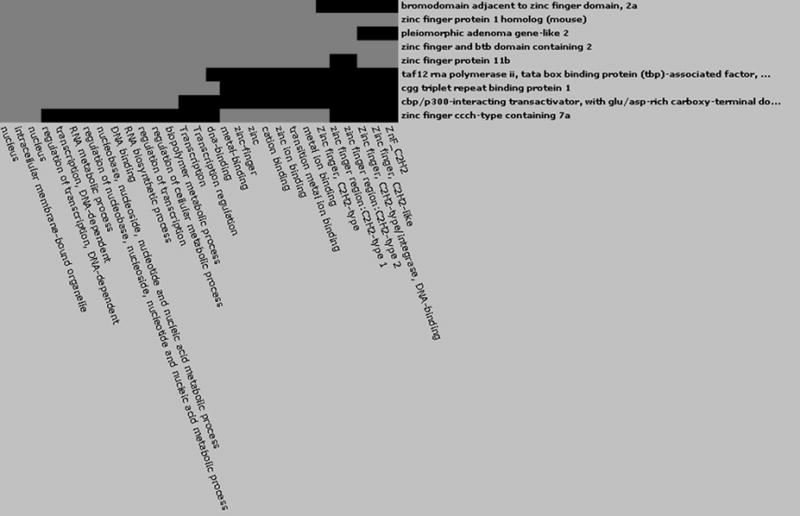

Functional annotation clustering of down-regulated genes

Of the 401 differentially expressed genes, 96 genes/clones were down-regulated compared to the expression levels of SKP spheres (P value≤0.05) and 62 were successfully converted to DAVID IDs. The GO terms of down-regulated genes are shown in Table 3. The featured GO terms are phosphoprotein and binding activity. One group was clustered with the enrichment score 0.67 (Fig 4), including zinc-finger domain proteins, bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain, pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like2, TATA box binding protein (TBP) associated factor, CGG triplet repeat binding protein and CBP/p300 interacting transactivator. These genes play a role in a broad range of transcriptional regulation. It seems that the down-regulated zinc finger proteins may be associated with the loss of neural potency during the transition of SKP spheres to SFC.

Table 3.

Gene ontology terms of down-regulated genes between SKP and SFC (P value ≤0.05). The “count” indicates the number of the genes involved in the term (62 DAVID IDs).

| Term | Count | Percent (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| phosphoprotein | 29 | 46.0 | 1.7E-4 |

| cytoplasm | 19 | 30.0 | 4.7E-4 |

| intracellular | 43 | 68.3 | 2.1E-3 |

| protein binding | 33 | 52.4 | 2.8E-3 |

| oxidoreductase activity, acting on the CH-OH group of donors, NAD or NADP as acceptor | 4 | 6.3 | 4.7E-3 |

| oxidoreductase activity, acting on CH-OH group of donors | 4 | 6.3 | 6.1E-3 |

| nucleus | 24 | 38.1 | 7.0E-3 |

| intracellular part | 40 | 63.5 | 7.9E-3 |

| Intracellular membrane-bound organelle | 32 | 50.8 | 8.7E-3 |

| membrane-bound organelle | 32 | 50.8 | 8.8E-3 |

| Intracellular organelle | 35 | 55.6 | 1.1E-2 |

| organelle | 35 | 55.6 | 1.1E-2 |

| nucleus | 20 | 31.7 | 1.8E-2 |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 8 | 12.7 | 2.1E-2 |

| Protein biosynthesis | 4 | 6.3 | 2.4E-2 |

| Regulation of apoptosis | 6 | 9.5 | 2.4E-2 |

| Regulation of programmed cell death | 6 | 9.5 | 2.4E-2 |

| cytoskeleton | 5 | 7.9 | 2.5E-2 |

| binding | 46 | 73.0 | 3.3E-2 |

| Positive regulation of apoptosis | 4 | 6.3 | 4.3E-2 |

| Nuclear part | 8 | 12.7 | 4.3E-2 |

| Positive regulation of programmed cell death | 4 | 6.3 | 4.3E-2 |

Figure 4.

2D view of gene functional classification of down-regulated genes between SKP spheres and SFC by DAVID online analysis. The grey boxes indicate positive gene-term association reported while the black boxes mean corresponding gene-term associations have not yet been reported.

Differential pathways involved in up-regulated and down-regulated genes

The key signaling pathways were then identified in up-regulated and down-regulated gene lists. For up-regulated genes, the potential enriched KEGG pathways are listed in Table 4. The highly involved pathways include cell communication, PPAR pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway, ErbB signaling, ECM-receptor interaction, mTOR signaling pathway and TGF-beta signaling pathway. For down-regulated genes, 5 BIOCARTA pathways were identified (Table 5): synaptic proteins in synaptic junction, Rac1 cell motility signaling pathway, role of Ran in mitotic spindle regulation, Dicer pathway and mechanism of protein import into the nucleus. Thus it appears up-regulated genes refer to extrinsic signaling pathways but down-regulated genes for intrinsic cell function. The separate pathways involved in up- and down-regulated genes manifest differential response of SKP cells to different extrinsic stimulus, which can be established and maintained by individual transcriptional states.

Table 4.

KEGG pathways involved in up-regulated genes when SKP spheres differentiate into SFC.

| Potential Pathways | Involved genes |

|---|---|

| Cell Communication (7) | lamin a/c; collagen, type i, alpha 2; collagen, type vi, alpha 2; actin, beta; tenascin r (restrictin, janusin); vimentin; collagen, type iii, alpha 1 (ehlers-danlos syndrome type iv, autosomal dominant) |

| PPAR Pathway (2) | ubiquitin c; cytochrome p450, family 27, subfamily a, polypeptide 1; |

| Cell Cycle (1) | cyclin b1 |

| ErbB signaling pathway (1) | neuregulin 4 |

| MAPK signaling pathway (3) | ras-related c3 botulinum substrate 1; guanine nucleotide binding protein (g protein), gamma 12; v-mos moloney murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| Wnt signaling pathway (4) | ras-related c3 botulinum substrate 1; casein kinase 1, alpha 1; nuclear factor of activated t-cells 5, tonicity-responsive; protein phosphatase 2 (formerly 2a), catalytic subunit, alpha isoform |

| ECM-receptor interaction (7) | collagen, type i, alpha 2; collagen, type vi, alpha 2; tenascin r (restrictin, janusin); cd47 antigen (rh-related antigen, integrin-associated signal transducer); integrin, alpha 2 (cd49b, alpha 2 subunit of vla-2 receptor); collagen, type iii, alpha 1 (ehlers-danlos syndrome type iv, autosomal dominant); integrin, beta 1 (fibronectin receptor, beta polypeptide, antigen cd29 includes mdf2, msk12) |

| mTOR signaling pathway (2) | tuberous sclerosis 1; hypoxia-inducible factor 1, alpha subunit (basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor) |

| TGF-beta signaling pathway (2) | latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 1; protein phosphatase 2 (formerly 2a), catalytic subunit, alpha isoform |

Table 5.

BIOCARTA pathways involved in down-regulated genes between SKP spheres and SFC.

| BIOCARTA pathways | Involved Genes |

|---|---|

| Synaptic Proteins at the Synaptic Junction | ankyrin 3, node of ranvier (ankyrin g); spectrin, beta, non-erythrocytic 1 |

| Rac 1 cell motility signaling pathway | adp-ribosylation factor interacting protein 2 (arfaptin 2) |

| Role of Ran in mitotic spindle regulation | ran, member ras oncogene family |

| Dicer Pathway | argonaute 4 |

| Mechanism of Protein Import into the Nucleus | nuclear transport factor 2 |

Real time PCR for data validation

To verify the microarray data, we carried out real time PCR by the relative standard curve method. We selected 6 genes: COL1A2, RAN, ILKAP, NAP1L4, DCN and PTGFR (Tables 6). The real time PCR data indicate a similar gene expression pattern with microarray data (Tables 7), confirming the reliability of our current microarray platform (Agca et al., 2006; Green et al., 2006; Whitworth et al., 2005).

Table 6.

Primers of real time qPCR used for microarray data validation

| Clone ID/GenBank ID | Gene name | Primers |

|---|---|---|

| UMC-pd12-14end-004-a01 | COL1A2 | Forward 5′ GCACGATGCTCTGATCAATCCTTCTC 3′ Reverse 5′ GACGTTGGCCCAGTCTGTTTCAAAT 3′ |

| UMC-pd12cl-016-c02 | PTGFR | Forward 5′ CACATGACACATTTCACCTGCTGT 3′ Reverse 5′ TAGCTTCACCTGTAGCACCGTCAT 3′ |

| UMC-p4mm1-001-c03 | DCN | Forward 5′ AGAGCGCACATAGACACATCGGAA 3′ Reverse 5′ AACAACAACATCTCTGCAGTCGGC 3′ |

| UMC-pd3end3-009-a08 | RAN | Forward 5′ ACAACTGCTCTCCCGGATGAAGAT 3′ Reverse 5′ AAACACGCTGCAACCACTGACATC 3′ |

| UMC-p4civp1-004-e01 | NAP1L4 | Forward 5′ TACAAACGCATCGTGAGGAAGGCT 3′ Reverse 5′ GAGTGTCCAGAGTTGCTTTCACCACA3′ |

| UMC-pgvo2-009-c01 | ILKAP | Forward 5′ AGGACAAGATGAAGTGGACGGGTT 3′ Reverse 5′ CCCAATGACAGGTTTATCTTGCTGGC 3′ |

| AF017079 | GAPDH | Forward 5′ GCAAAGTGGACATTGTCGCCATCA 3′ Reverse 5′ AGCTTCCCATTCTCAGCCTTGACT 3′ |

Table 7.

Relative gene expression levels (Mean ± SEM and P value) from microarray data and real time qPCR analysis.

| Microarraya | Real time qPCRb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | SKP | SFC | P value | SKP | SFC | P value |

| COL1A2 | 4.414±1.517 | 1.727±0.1946 | 0.0193 | 19.14±1.636 | 13.15±0.9843 | 0.02012 |

| DCN | 1.970±0.2580 | 1.502±0.09557 | 0.0971 | 36.10±3.103 | 13.42±0.8352 | 0.000406 |

| RAN | 1.289±0.1502 | 0.9120±0.05043 | 0.0284 | 17.07±3.084 | 8.037±0.4533 | 0.01586 |

| NAP1L4 | 0.8591±0.06463 | 0.5861±0.07458 | 0.0293 | 1.705±0.1433 | 1.212±0.1447 | 0.03612 |

| ILKAP | 0.8525±0.09328 | 0.5567±0.08708 | 0.0471 | 0.5079±0.03102 | 0.2440±0.01712 | 2.2E-05 |

| PTGFR | 0.8448±0.09936 | 1.471±0.4090 | 0.0854 | 0.3916±0.01005 | 0.8952±0.1892 | 0.03764 |

Microarray data were normalized to Ref cDNA.

Real time PCR values were normalized to house keeping gene GAPDH.

Discussion

In this study we compared the transcriptional profiles of SKP spheres and SKP derived fibroblast-like cells (SFC) by microarray technology. Interestingly, the up-regulated and down-regulated genes are involved in differential extrinsic signaling and cell activities. The up-regulated genes mainly relate to upstream signaling pathways that transduce external stimulus into downstream cellular responses; whereas the down-regulated genes are involved in downstream cellular response such as transcriptional regulation, posttranscriptional modulation (non-coding RNA) and protein transportation. That is to say, the components of upstream signaling pathways are up-regulated while those of downstream cellular response pathways are down-regulated. Thus it is suggested that SKP spheres and SFC may employ divergent signaling pathways in response to different extrinsic stimulus, reflecting the shift of stem cell state and fate in vitro (Enver et al., 2009).

It seems that the identified down-regulated genes related pathways play a role in the regulation of stem-cell identity. Initially, spectrin and ankyrin can build up the membrane skeleton of mammalian erythrocyte with other associated proteins. Their functions include targeting of ion channels and cell adhesion molecules to specialized compartment within the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum of the nervous system, participation in epithelial morphogenesis, and orientation of mitotic spindles in asymmetric cell divisions (Bennett and Baines, 2001). Moreover, the Ran GTPase (Table 5), which is soluble, mobile and concentrated by a nuclear import mechanism involving nuclear transport factor-2 (NTF2), can regulate the assembly of the mitotic spindle and the timing of cell-cycle transitions (Clarke and Zhang, 2008). Together it is tempting to speculate that Ran GTPase, NTF2, spectrin and ankyrin may participate in the regulation of asymmetric cell division, which is a fundamental means of generating cell-fate diversity in the development of Drosophila nervous system (Jan and Jan, 2001). It is widely known that asymmetric cell division is a hallmark of stem cells which enables them to simultaneously self-renewal and generate differentiated progeny (Knoblich, 2008); although asymmetric division is not necessary for stem-cell identity but rather is a tool that stem cells can alternatively employ to maintain appropriate numbers of progeny either during development or during wound healing and regeneration (Morrison and Kimble, 2006). Nevertheless, asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin (Lechler and Fuchs, 2005). Therefore, we infer that asymmetric cell divisions are likely to be tuned up by the collaboration of Ran GTPase, spectrin and ankyrin, which are suppressed in SFC cultures but promoted in SKP spheres (Table 3).

Another key pathway for down-regulated genes is the Dicer pathway, implying a potential role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the regulation of stem-cell identity of SKP cells. Dicer catalyzes the first step in RNA interference (RNAi) and initiates the formation of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) whose catalytic component Argonaute family proteins can interact with miRNAs or small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and function as a posttranscriptional regulator (Kim et al., 2009b). The miRNAs can serve as a key regulator in stem cells: regulating stem cell self-renewal and differentiation by suppression of specific target mRNA (Gangaraju and Lin, 2009). miRNAs are crucial for the regulation of self-renewal, cellular differentiation, and pluripotency in embryonic stem cells (Marson et al., 2008; Tay et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2009). In somatic stem cells, miR-124 regulates adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone stem cell niche (Cheng et al., 2009); whereas miR-203 directly promotes epidermal differentiation in skin by restricting proliferation potential and inducing cell-cycle exit (Yi et al., 2008). Most recently miR-145 and miR-143 have been demonstrated to regulate the smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity by multipotent stem cells (Cordes et al., 2009). Furthermore, it was found that Dicer is required for the morphogenesis and maintenance of the hair follicle but is not essential for skin stem cell fate determination and differentiation (Andl et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2006). In addition, the pre-miRNAs are translocated into the cytoplasm by the exportin 5-Ran GTP shuttle system (Gangaraju and Lin, 2009). Thus, the down-regulation of the Argonaute family may be correlated with the decreasing of the Ran family, resulting in less pre-miRNA present in the cytoplasm of SFC. Together, we infer that miRNA and/or asymmetric cell division may mediate the transition of stem-cell state between SKP spheres and SFC.

The up-regulated genes are mainly involved in extrinsic signaling pathways which transduce the external signaling into cellular parts, even though the stem cell behavior is regulated by both extrinsic signals and intrinsic programs (Li and Xie, 2005). During embryonic skin development, Wnt signaling blocks the ability of early ectodermal progenitor cell in response to FGFs, allowing them to respond to TGF-beta signaling and to adopt an epidermal fate (Fuchs, 2007). Wnt and TGF-beta signaling have substantial roles in the specification and activation of the hair follicle stem cells during embryonic skin development and adulthood (Blanpain and Fuchs, 2009): Wnt signaling can promote de novo hair follicle regeneration in adult skin after wounding (Ito et al., 2007) while cyclic dermal TGF-beta signaling regulates hair follicle stem cell activation during hair regeneration (Plikus et al., 2008). PPAR (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor) signaling can induce and stimulate adipogenesis either in fibroblast or in mesenchymal stem cells (Hong et al., 2005; Lehrke and Lazar, 2005; Rosen et al., 1999). Recently it is reported that PPAR signaling is required for maintaining a functional epithelial stem cell compartment of hair follicles (Harries and Paus, 2009; Karnik et al., 2009). In addition, activation of ERK/MAPK pathway often promotes cell division and is related with human cancers. Although Erk1/2 MAP kinase is required for normal epidermal G2/M progression (Dumesic et al., 2009), other MAPK-dependent signaling can also contribute to epithelial skin carcinogenesis (Bourcier et al., 2006), suggesting that the MAPK pathway has an important role in the control of skin epidermal proliferation (Fuchs, 2007). To sum up, Wnt, TGF-beta, PPAR and MAPK signaling pathways mediate the proliferation, differentiation and cell fate determination in skin development and maintain the homeostasis in adult skin. We have detected up-regulation of the components of these signaling pathways, showing their potential roles in controlling the growth and differentiation of SKP spheres in vitro.

In conclusion, we compared the transcriptional profiles between SKP spheres and SFC and identified potential signaling pathways conferring the molecular “stemness” of SKP spheres. The up-regulated and down-regulated genes are involved in extrinsic signaling pathways and intrinsic programs respectively, which could cooperate to choreograph the transcriptional state transition during the differentiation of SKP spheres to SFC. Our data pave the way for illustrating the molecular mechanisms of self-renewal and multipotency of skin derived stem cells, making it possible to take advantage of their potential therapeutic applications.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. S Clay Isom for helpful discussion, Kyle B Dobbs for careful reading, and Dr. William G Spollen at Department of Computer Science for cDNA library annotation. This work was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources (R01RR013438 to RSP) and Food for the 21st Century at the University of Missouri.

References

- Agca C, Ries JE, Kolath SJ, et al. Luteinization of porcine preovulatory follicles leads to systematic changes in follicular gene expression. Reproduction. 2006;132:133–145. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M, Peters AH. Genetic and epigenetic control of early mouse development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andl T, Murchison EP, Liu F, et al. The miRNA-processing enzyme dicer is essential for the morphogenesis and maintenance of hair follicles. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SJ, Robertson EJ. Making a commitment: cell lineage allocation and axis patterning in the early mouse embryo. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:91–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch G, Yoo JJ, De Coppi P, et al. Propagation, expansion, and multilineage differentiation of human somatic stem cells from dermal progenitors. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:337–348. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett V, Baines AJ. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1353–1392. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal homeostasis: a balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:207–217. doi: 10.1038/nrm2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourcier C, Jacquel A, Hess J, et al. p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1)-dependent signaling contributes to epithelial skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 66:2700–2707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers I, Silva J, Colby D, et al. Nanog safeguards pluripotency and mediates germline development. Nature. 2007;450:1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/nature06403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FG, Zhang WJ, Bi D, et al. Clonal analysis of nestin(-) vimentin(+) multipotent fibroblasts isolated from human dermis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2875–2883. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng LC, Pastrana E, Tavazoie M, et al. miR-124 regulates adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone stem cell niche. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:399–408. doi: 10.1038/nn.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PR, Zhang C. Spatial and temporal coordination of mitosis by Ran GTPase. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:464–477. doi: 10.1038/nrm2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, et al. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460:705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crigler L, Kazhanie A, Yoon TJ, et al. Isolation of a mesenchymal cell population from murine dermis that contains progenitors of multiple cell lineages. Faseb J. 2007;21:2050–2063. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5880com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumesic PA, Scholl FA, Barragan DI, et al. Erk1/2 MAP kinases are required for epidermal G2/M progression. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:409–422. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyce PW, Zhu H, Craig J, et al. Stem cells with multilineage potential derived from porcine skin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enver T, Pera M, Peterson C, et al. Stem cell states, fates, and the rules of attraction. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes KJ, McKenzie IA, Mill P, et al. A dermal niche for multipotent adult skin-derived precursor cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1082–1093. doi: 10.1038/ncb1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes KJ, Toma JG, Miller FD. Multipotent skin-derived precursors: adult neural crest-related precursors with therapeutic potential. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:185–198. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. Scratching the surface of skin development. Nature. 2007;445:834–842. doi: 10.1038/nature05659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangaraju VK, Lin H. MicroRNAs: key regulators of stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:116–125. doi: 10.1038/nrm2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JA, Kim JG, Whitworth KM, et al. The use of microarrays to define functionally-related genes that are differentially expressed in the cycling pig uterus. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2006;62:163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries MJ, Paus R. Scarring alopecia and the PPAR-gamma connection. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1066–1070. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoheisel JD. Microarray technology: beyond transcript profiling and genotype analysis. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:200–210. doi: 10.1038/nrg1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JH, Hwang ES, McManus, et al. TAZ, a transcriptional modulator of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Science. 2005;309:1074–1078. doi: 10.1126/science.1110955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Yang Z, Andl T, et al. Wnt-dependent de novo hair follicle regeneration in adult mouse skin after wounding. Nature. 2007;447:316–320. doi: 10.1038/nature05766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova NB, Dimos JT, Schaniel C, et al. A stem cell molecular signature. Science. 2002;298:601–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan YN, Jan LY. Asymmetric cell division in the Drosophila nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:772–779. doi: 10.1038/35097516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph NM, Morrison SJ. Toward an understanding of the physiological function of Mammalian stem cells. Dev Cell. 2005;9:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243–1257. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009a;4:472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lo L, Dormand E, et al. SOX10 maintains multipotency and inhibits neuronal differentiation of neural crest stem cells. Neuron. 2003;38:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009b;10:126–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich JA. Mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division. Cell. 2008;132:583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechler T, Fuchs E. Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature. 2005;437:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nature03922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrke M, Lazar MA. The many faces of PPARgamma. Cell. 2005;123:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Xie T. Stem cell niche: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:605–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K, Sicker M, Schmelzer E, et al. Multilineage differentiation potential of human dermal skin-derived fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:925–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel M, Herr A, Milosevic J, et al. Transcription profiling of adult and fetal human neuroprogenitors identifies divergent paths to maintain the neuroprogenitor cell state. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1231–1240. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson A, Levine SS, Cole MF, et al. Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, et al. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Kimble J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature. 2006;441:1068–1074. doi: 10.1038/nature04956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Burdon T, Chambers I, et al. Self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells is mediated via activation of STAT3. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2048–2060. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus MV, Mayer JA, de la Cruz D, et al. Cyclic dermal BMP signalling regulates stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Nature. 2008;451:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature06457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho-Santos M, Yoon S, Matsuzaki Y, et al. “Stemness”: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells. Science. 2002;298:597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1072530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheinwald JG, Green H. Serial cultivation of strains of human epidermal keratinocytes: the formation of keratinizing colonies from single cells. Cell. 1975;6:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(75)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, et al. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M. A gene regulatory network orchestrates neural crest formation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nrm2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Sun Y, Liu Y, et al. Whole genome analysis of human neural stem cells derived from embryonic stem cells and stem and progenitor cells isolated from fetal tissue. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1298–1306. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Webb NE, Song Y, et al. Identification and functional analysis of candidate genes regulating mesenchymal stem cell self-renewal and multipotency. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1707–1718. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, et al. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, et al. Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature. 2002;416:542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terskikh AV, Miyamoto T, Chang C, et al. Gene expression analysis of purified hematopoietic stem cells and committed progenitors. Blood. 2003;102:94–101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJ, et al. Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:778–784. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma JG, McKenzie IA, Bagli D, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotent skin-derived precursors from human skin. Stem Cells. 2005;23:727–737. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbar T, Guasch G, Greco V, et al. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science. 2004;303:359–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1092436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers AJ, Weissman IL. Plasticity of adult stem cells. Cell. 2004;116:639–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner W, Wein F, Seckinger A, et al. Comparative characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1402–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth K, Springer GK, Forrester LJ, et al. Developmental expression of 2489 gene clusters during pig embryogenesis: an expressed sequence tag project. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1230–1243. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KM, Agca C, Kim JG, et al. Transcriptional profiling of pig embryogenesis by using a 15-K member unigene set specific for pig reproductive tissues and embryos. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:1437–1451. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.037952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KM, Li R, Spate LD, et al. Method of oocyte activation affects cloning efficiency in pigs. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:490–500. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, et al. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, O’Carroll D, Pasolli HA, et al. Morphogenesis in skin is governed by discrete sets of differentially expressed microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2006;38:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Poy MN, Stoffel M, et al. A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing ‘stemness’. Nature. 2008;452:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature06642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying QL, Nichols J, Evans EP, et al. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002;416:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Isom SC, Lin H, et al. Tracing the stemness of porcine skin-derived progenitors (pSKP) back to specific marker gene expression. Cloning Stem Cells. 2009;11:111–122. doi: 10.1089/clo.2008.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Wu S, Joo JY, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]