Abstract

Objectives:

Given mixed evidence for carcinogenicity of current-use herbicides, we studied the relationship between occupational herbicide use and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in a large, pooled study.

Methods:

We pooled data from ten case-control studies participating in the InterLymph Consortium, including 9229 cases and 9626 controls from North America, the European Union, and Australia. Herbicide use was coded from self-report or by expert assessment in the individual studies, for herbicide groups (e.g., phenoxy herbicides) and active ingredients (e.g., 2,4-D, glyphosate). The association between each herbicide and NHL risk was estimated using logistic regression to produce odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), with adjustment for sociodemographic factors, farming, and other pesticides.

Results:

We found no substantial association of all NHL risk with ever-use of any herbicide (OR=1.10, 95% CI: 0.94–1.29), nor with herbicide groups or active ingredients. Elevations in risk were observed for NHL subtypes with longer duration of phenoxy herbicide use, such as for any phenoxy herbicide with multiple myeloma (>25.5 years, OR=1.78, 95% CI: 0.74–4.27), 2,4-D with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (>25.5 years, OR=1.47, 95% CI: 0.67–3.21), and other (non-2,4-D) phenoxy herbicides with T-cell lymphoma (>6 years, lagged 10 years, OR=3.24, 95% CI: 1.03–10.2). An association between glyphosate and follicular lymphoma (lagged 10 years: OR=1.48, 95% CI: 0.98–2.25) was fairly consistent across analyses.

Conclusions:

Most of the herbicides examined were not associated with NHL risk. However, associations of phenoxy herbicides and glyphosate with particular NHL subtypes underscore the importance of estimating subtype-specific risks.

Keywords: non-Hodgkin lymphoma, glyphosate, follicular lymphoma, pesticide, herbicide

INTRODUCTION

Synthetic herbicides were first introduced to the agricultural market for weed control in the 1940s. Today, herbicides are widely applied in farming as well as urban and residential settings, resulting in potential exposure for both applicators and the general public. Several herbicides have been evaluated for human carcinogenicity in recent years by international or national advisory or regulatory bodies; for example, in 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) as a possible carcinogen and glyphosate as a probable carcinogen.1,2

The human (epidemiologic) data supporting these assessments were considered inadequate or limited,3,4 forcing heavy reliance on the available animal bioassays and mechanistic data for evidence conclusions. Nevertheless, several epidemiologic studies showed positive relationships between exposure to the herbicide active ingredients and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), so research has continued to focus on NHL as a target cancer outcome. Noted limitations of the previous epidemiologic research include assessment of simple exposure metrics such as ever-use that did not characterize dose or level of exposure, limited- or no adjustment for other pesticides, and small sample sizes. More recent studies have sought to overcome these limitations, primarily through analysis of large study populations and assessment of semi-quantitative exposure metrics including duration, frequency, and intensity.

While the evidence linking herbicide exposures to NHL risk is mixed, heavy use of herbicides begs further study. To add new data on the topic, we conducted a pooled analysis of case-control studies participating in the International Lymphoma Epidemiology (InterLymph) Consortium. Our aim was to estimate associations between occupational herbicide use and risk of NHL and its major subtypes in a large study population, with a particular focus on 2,4-D and glyphosate. We also aimed, to the extent possible, to estimate risks for various exposure metrics harmonized across the studies, including duration and lagged use.

METHODS

Study Population

InterLymph formed in 2001 to facilitate intellectual exchange and collaborative research towards identifying preventable risk factors for lymphoid cancers. Individual case-control studies participating in InterLymph were eligible for this pooled analysis if they collected information on occupational chemical use by questionnaire items that implicitly or explicitly elicited reporting of herbicides.

A summary of the ten participating case-control studies is provided in Table 1.5–16 The studies included persons with histologically confirmed incident primary diagnosis of NHL during the respective enrollment periods, spanning 1980 to 2013. Reflecting changes in the pathology classification of lymphomas,17 the studies used different criteria for inclusion of lymphoma subtypes. Controls were identified from the general population or participating hospitals/clinics and were frequency- or pair-matched to the cases by factors including age and sex, and in some studies, region or race. The pooled data included 9626 controls and 9229 cases (1638 chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma/mantle cell lymphoma/prolymphocytic leukemia [hereafter referred to, collectively, as CLL], 2160 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL], 1587 follicular lymphoma [FL], 1581 other B-cell lymphoma [OBCL], 1355 multiple myeloma [MM], 456 T-cell lymphoma [TCL], and 452 not otherwise specified/unknown [NOS/UNK]).

Table 1.

Case-control studies participating in the InterLymph study of herbicidesa

| Study abbreviation (citation) | LAMMCC (Nuyujukian et al. 2014) | LANHL (Bernstein et al. 1992) | Italian Multicenter (Miligi et al. 2003) | Yale (Zhang et al. 2004, Koutros et al. 2009) | NCI-SEER (Hartge et al. 2005) | Epilymph (Cocco et al. 2013) | NSW (Fritschi et al. 2005) | ENGELA (Orsi et al. 2009) | Mayo (Cerhan et al. 2011) | BCMM (Weber et al. 2018) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location(s) | USA: Los Angeles County | USA: Los Angeles County | Italy: Firenze, Forli, Imperia, Latina, Novara, Ragusa, Siena, Torino, Verona | USA: Connecticut | USA: Detroit, Iowa, Los Angeles County, Seattle | Europe: Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain | Australia: New South Wales and Australian Capital Territory | France: Bordeaux, Brest, Caen, Lille, Nantes, Toulouse | USA: Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin | Canada: British Columbia |

| Case diagnosis years | 1980–1990 | 1988–1991 | 1990–1994 | 1996–2002 | 1998–2000 | 1998–2003 | 1999–2001 | 2000–2004 | 2002–2012 | 2009–2013 |

| Source of controls | Population | Population | Population | Population | Population | Population or Hospital | Population | Hospital | Clinic | Population |

| Control matching to cases | Pair-matched by age, sex, race, neighborhood | Pair-matched by age, sex, race, neighborhood | Frequency-matched by age, sex | Frequency-matched by age; females only | Frequency-matched by age, sex, race | Pair-matched or frequency-matched by age, sex, region | Frequency-matched by age, sex, region | Pair-matched by age, sex, region | Frequency-matched by age, sex, region | Frequency-matched by age, sex |

| Participants queried regarding occupational pesticides | All | All | Ever worked in agriculture | All | All | All | Ever worked as farmer, pesticide applicator, or gardener | Ever worked as farmer or gardener for at least 6 months | Ever worked on a farm or with pesticides for >1 year | Ever lived on a farm or worked in agriculture, gardening, parks, golf courses, or forestry |

| Basis for pesticide use classification | Self-report (closed-ended questions on pesticides exposed to at work) | Self-report (open-ended question on pesticides directly exposed to at work) | Expert-assessment (open-ended questions on products used at work and additional farming questionnaire; responses checked against a crop-exposure matrix) | Self-report (open-ended questions on exposures at work or home and additional farming questionnaire for pesticides handled, with provided list of frequently used pesticides as a prompt) | Self-report (open-ended question on chemicals/materials handled at work) | Expert-assessment (open-ended questions on products used at work and additional job-specific module farming questionnaire; responses checked against product availability dates and a crop-exposure matrix, with the support of agronomists) | Expert-assessment (open-ended questions on specific pesticides personally mixed or applied from job-specific questionnaire; responses checked against product availability dates and a crop-exposure matrix) – any herbicides and phenoxy herbicides only; other herbicides assessed by self-report | Expert-assessment (open-ended questions about products used at work and additional farming questionnaire; responses checked against product availability dates, type and size of crops, geographic location, and treatment frequency) | Self-report (closed-ended questions on pesticides personally mixed or applied) | Self-report (open-ended questions on pesticides personally applied, mixed, or loaded at work or when living on a farm) |

| Included in the pooled study (Ns) | ||||||||||

| Cases | 275 | 368 | 1243 | 773 | 1189 | 2000 | 688 | 404 | 1898 | 391 |

| Controls | 278 | 372 | 1142 | 706 | 982 | 2462 | 683 | 447 | 2183 | 371 |

| Case subtypes (% of all cases) | ||||||||||

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma/mantle cell lymphoma/prolymphocytic leukemia (CLL/SLL) | 0% | 0% | 9.3% | 8.5% | 14.2% | 23.8% | 7.4% | 24.3% | 34.8% | 0% |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) | 0% | 35.9% b | 21.2% | 24.3% | 30.8% | 25.6% | 33.3% | 26.5% | 19.1% | 0% |

| Follicular lymphoma (FL) | 0% | 10.6% | 8.2% | 17.6% | 24.6% | 12.5% | 36.2% | 12.4% | 24.7% | 0% |

| Multiple myeloma (MM) | 100% | 0% | 14.2% | 23.2% | 0% | 13.8% | 0% | 13.9% | 0% | 100% |

| Other B-cell lymphoma (OBCL) | 0% | 27.2% | 2.6% | 7.6% | 14.8% | 17.4% | 15.4% | 14.9% | 10.2% | 0% |

| T-cell lymphoma (TCL) | 0% | 0.3% | 4.5% | 4.4% | 6.2% | 6.6% | 3.5% | 5.2% | 4.6% | 0% |

| NOS-unknown (NOS-UNK) | 0% | 26.1% | 39.9% | 14.4% | 9.4% | 0.3% | 4.2% | 3.0% | 6.6% | 0% |

| Control characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 61.2 (9.0) | 51.1 (14.4) | 55.0 (13.7) | 61.3 (14.2) | 58.1 (12.3) | 56.2 (16.0) | 56.3 (12.0) | 52.5 (13.5) | 61.6 (13.1) | 65.6 (8.0) |

| Male gender (%) | 54.7% | 49.2% | 55.4% | 0% | 53.4% | 53.6% | 57.7% | 100% | 53.3% | 57.4% |

| Non-white race or Hispanic ethnicity (%) | 32.0% | 23.9% | 0% | 8.1% | 21.4% | 1.5%c | 12.9% | 0.4% | 2.4% | 9.4% |

| Low socioeconomic status (%) | 46.4% | 32.3% | 57.3% | 36.7% | 37.2% | 45.5% | 33.7% | 27.7% | 23.0% | 29.4% |

| Farming job, ever (%) | 10.4% | 6.5% | 31.4% | 2.1% | 9.5% | 17.1% | 15.1% | 18.1% | 15.6% | 7.0% |

| Occupational pesticide use, ever (%) | 5.0% | 8.3% | 26.7% | 11.9% | 11.2% | 8.5% | 10.5% | 10.5% | 14.2% | 5.1% |

| Occupational insecticide use, ever (%) | 2.2% | 3.8% | 6.3% | 8.2% | 6.7% | 2.0% | 8.6% | 8.3% | 12.1% | 3.8% |

| Occupational herbicide use, ever (%) | 1.4% | 1.6% | 5.2% | 6.2% | 5.2% | 2.0% | 4.8% | 9.4% | 13.6% | 3.5% |

Studies are ordered in table by the earliest case diagnosis year

The LANHL study included intermediate- and high-grade NHL diagnosed in HIV-negative individuals, to correspond to a concurrent study protocol of HIV-related NHL

Assumed non-white race

Variables already harmonized for previous InterLymph analyses included age at the reference date (diagnosis date or corresponding date for controls), sex, race/Hispanic ethnicity, socioeconomic status at the reference date (SES, based on education and/or income18), NHL subtype coded according to the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification,19,20 and job titles from occupational histories, coded according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) 1968.21,22

Pesticide Exposure Coding

Each study provided data on occupation, farming, and pesticide use. Occupational use of pesticides was coded directly from questionnaire responses (i.e., self-report) or from reviews conducted by local experts in the individual studies (i.e., expert assessment), as described previously (Supplemental Material I).23

Particular herbicides were selected for the pooled analysis based on exposure in at least three studies, and included use of any herbicide, the broad herbicide groups of phenoxy acids (‘phenoxy’ herbicides), triazines, and amides, and the active ingredients 2,4-D, glyphosate, atrazine, alachlor, trifluralin, dicamba, pendimethalin, and paraquat, as well as grouped ‘other’ (non-2,4-D) phenoxy herbicides (e.g., 2,4,5-T, MCPA, mecoprop). For each herbicide group or active ingredient, exposure variables were summarized across all jobs held by a participant. Ever-use and use duration were coded, in addition to lagged versions of these variables that captured use >10 years before NHL diagnosis or the corresponding reference date for controls. Duration variables were categorized based on percentiles (p), in two categories (<=50p, >50p) and three categories (<=50p, >50p to 75p, >75p).

Although a 10-year exposure lag was selected for the main analysis, a priori, variables were also created for lagged exposure windows that covered multiple periods before the case diagnosis or control reference date. These were coded as four indicator variables (>0–5 years, >5–10 years, >10–20 years, >20 years), and participants could be included in one or multiple exposure windows, depending on their years of use. Another set of indicator variables was created to represent decades of use (before 1960, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000 or later).

Statistical Analysis

Pooled Analysis.

Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for associations between herbicide use and risk of NHL. All pooled analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.4 (Cary, NC, USA). Exposure was analyzed in separate models as ever-use, duration, 10-year lagged ever-use or duration, lagged exposure windows, and decades of use – each with never-use of the particular herbicide as the reference category. The linear trend in NHL risk across categories of duration was evaluated by the p-value from modeling the median of each duration category as a continuous variable. Several variables were selected, a priori, to adjust for potential confounding, including (all coded as indicator terms) the study center (i.e., specific city/hospital of data collection), age (<45, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, ≥75 years), gender, SES (low, medium, high), race/ethnicity (white, non-Hispanic vs. non-white or Hispanic), and farming occupation (ever vs. never). Covariates were also included to adjust for other pesticide use, as evidence of confounding by other pesticides has been suggested in previous studies of herbicides and NHL.1,2 This adjustment included up to 5 covariates, selected and coded specifically for each herbicide, broadly including indicators for use of organophosphate insecticides, organochlorine insecticides, phenoxy herbicides, glyphosate, and any other pesticide (details in Supplemental Material 2).

Etiologic heterogeneity was evaluated by fitting polytomous logistic regression models for the NHL subtypes, with estimation of the OR and 95% CI for each subtype-specific association versus a common control group.

Meta-Analysis.

Random effects meta-analysis was conducted on study-specific ORs to assess comparability to findings from the pooled analysis, and to test heterogeneity of the estimated effect among studies by the p-value for the I2 statistic (p-value for heterogeneity, or ‘p-het’). Meta-analysis was conducted using StataSE v.15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Sensitivity Analysis.

Several additional analyses of the pooled data were conducted to assess sensitivity of the main results to: 1) no adjustment for other pesticides; 2) limiting to participants who never used other specific herbicides as an alternative approach to assessing confounding, in analysis of phenoxy herbicides (excluded if used glyphosate), 2,4-D (excluded if used other phenoxy herbicides or glyphosate), other phenoxy herbicides (excluded if used 2,4-D or glyphosate), and glyphosate (excluded if used phenoxy herbicides); 3) limiting exposure to high-frequency (e.g. days/year) of use in 6 of the 10 studies (defined as frequency of use above the 25th percentile frequency value for the particular herbicide in each study); herbicide use from the 4 studies without frequency information were also included in this analysis using the same exposure coding as the main analysis; 4) limiting the population to participants who ever worked on a farm, as this subgroup was more likely to be exposed than the rest of the study population, yet may also have had unmeasured risk factors;24 5) limiting to participants who never worked in farming but ever worked in non-farming jobs considered, a priori, to have relatively high probability of herbicide use, including jobs in forestry and occupation as a gardener/groundskeeper, janitor/cleaner, or general laborer; 6) fitting separate models for men and women, as the two genders may have different levels of exposure;25 7) fitting separate models for studies with exposures coded according to expert assessment or self-report; 8) fitting separate models for the largest study with the highest herbicide exposure prevalence (Mayo), and other studies excluding Mayo.

RESULTS

The ten case-control studies participating in the pooled analysis were conducted in North America, Europe, and Australia from 1980 to 2013 (Table 1). Controls differed between the studies by history of work in farming, as at least one study exclusively focused on agricultural regions (Italian Multicenter, 31.4% ever held farming job), other studies included a mix of rural and urban areas (ENGELA and Mayo, 15.6–18.1% farming), and several studies were conducted in large cities (LAMMCC, LANHL, and BCMM, 6.5–10.4% farming). Occupational pesticide use was somewhat reflective of farming history in the studies, ranging from 5% (LAMMCC) to 26% (Italian). Herbicide use ranged from 1.4% (LAMMCC) to 13.6% (Mayo) and was generally less common than insecticide use, except in two studies conducted after the year 2000 (ENGELA and Mayo). Individual study prevalences of all the herbicides are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Characteristics of the 9229 cases and 9626 controls in the pooled dataset are shown in Table 2. Although most of the individual studies matched by demographic factors, cases were slightly older and more frequently male than the controls. Cases and controls were fairly similar with regard to race; over 90% of participants were white/assumed white. Cases were slightly more likely than controls to be classified as low SES (41.5% vs. 37.6%) or to have ever worked in farming (16.5% vs. 15.5%). Cases were also more likely than controls to have ever used any type of pesticide (13.7% vs. 12.5%) or herbicide (7.0% vs. 6.2%). Controls with occupational herbicide use had frequently worked in farming (70.5%), as gardeners/groundskeepers (7.4%), cleaners/janitors/building maintenance workers (6.1%), and general laborers (6.2%) (not shown). Out of all controls who ever worked in farming, 28.2% had used herbicides (not shown).

Table 2.

Characteristics of cases and controls in the InterLymph study of herbicides (n [%])

| Controls | Cases | |

|---|---|---|

| N=9626 | N=9229 | |

| Age | ||

| <45 years | 1692 (17.6) | 1306 (14.1) |

| 45–54 years | 1726 (17.9) | 1716 (18.6) |

| 55–64 years | 2472 (25.7) | 2566 (27.8) |

| 65–74 years | 2886 (30.0) | 2849 (30.9) |

| ≥75 years | 850 (8.8) | 792 (8.6) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 4597 (47.8) | 4195 (45.4) |

| Male | 5029 (52.2) | 5034 (54.6) |

| Race/Hispanic ethnicity a | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 8928 (92.8) | 8471 (91.8) |

| Black | 244 (2.5) | 226 (2.5) |

| Other non-white or Hispanic | 416 (4.3) | 483 (5.2) |

| Missing | 38 (0.4) | 49 (0.5) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Low | 3614 (37.6) | 3827 (41.5) |

| Medium | 3170 (32.9) | 2754 (29.8) |

| High | 2762 (28.7) | 2203 (23.9) |

| Missing | 80 (0.8) | 445 (4.8) |

| Job history (ever) | ||

| Farming | 1492 (15.5) | 1526 (16.5) |

| Forestry | 65 (1.0) | 69 (1.1) |

| Gardener/groundskeeper | 74 (1.0) | 93 (1.3) |

| Janitor/cleaner | 344 (4.8) | 400 (5.7) |

| General laborer | 460 (4.8) | 532 (5.8) |

| Occupational pesticide use (ever) | ||

| Any b | 1201 (12.5) | 1263 (13.7) |

| Insecticide | 639 (6.6) | 669 (7.2) |

| Herbicide | 596 (6.2) | 644 (7.0) |

White category includes ‘assumed white’, based on region and/or ethnicity (<2% of study population)

Occupational use of any type of pesticide including insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, fumigants, rodenticides, etc.

We present as our main results, analyses of ever-use and duration (Table 3) The full set of pooled results including 10-year lagged exposures, exposure windows, and decades of use are in Supplemental Table 2. Occupational use of any type of herbicide was only weakly associated with risk of all NHL (OR=1.10, 95% CI: 0.94–1.29). Increased risk of TCL was estimated in association with ever-use of any herbicide (OR=1.40, 95% CI: 0.87–2.27) and moderate duration (>12 to 25.5 years, OR=2.21, 95% CI: 1.11–4.41). There was little difference between lagged and unlagged exposure associations for any herbicide use with all NHL (Supplemental Table 2). Herbicide use during the 1960s was associated with increased risk of all NHL, as was use in the 2000s or later (Table 4). However, the association between herbicide use and TCL was strongest for use in the 1970s (OR=3.28, 95% CI: 1.42–7.56).

Table 3.

Associations between occupational herbicide use and risk of NHL and NHL subtypes (odds ratios [OR] & 95% confidence intervals [CI]) a

| All NHL | CLL | DLBCL | FL | OBCL | MM | TCL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Controls | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Adjustments for other pesticides | |

| Herbicides, any b 10 studies: BCMM, ENGELA, Epilymph, Italian, LANHL, LAMMCC, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW, Yale |

Never | 9030 | 8585 | 1 (Referent) | 1473 | 1 (Referent) | 2031 | 1 (Referent) | 1451 | 1 (Referent) | 1482 | 1 (Referent) | 1299 | 1 (Referent) | 422 | 1 (Referent) | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Any other pesticide |

| Ever | 596 | 644 | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) | 165 | 0.99 (0.74–1.31) | 129 | 1.07 (0.82–1.39) | 136 | 1.13 (0.85–1.52) | 99 | 1.08 (0.80–1.44) | 56 | 1.18 (0.81–1.71) | 34 | 1.40 (0.87–2.27) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤12 years | 302 | 323 | 1.11 (0.92–1.33) | 78 | 1.03 (0.74–1.42) | 63 | 1.02 (0.75–1.40) | 78 | 1.25 (0.91–1.72) | 44 | 0.97 (0.67–1.39) | 30 | 1.13 (0.72–1.79) | 17 | 1.31 (0.74–2.31) | ||

| >12 to 25.5 | 157 | 182 | 1.23 (0.95–1.58) | 58 | 1.14 (0.77–1.69) | 35 | 1.24 (0.81–1.90) | 28 | 0.93 (0.57–1.50) | 34 | 1.41 (0.91–2.20) | 9 | 1.00 (0.44–2.24) | 13 | 2.21 (1.11–4.41) | ||

| >25.5 | 132 | 129 | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) | 28 | 0.66 (0.40–1.07) | 29 | 1.05 (0.66–1.67) | 27 | 0.99 (0.60–1.65) | 18 | 0.87 (0.50–1.52) | 17 | 1.44 (0.75–2.80) | 3 | 0.62 (0.18–2.10) | ||

| p-trend=0.94 c | p-trend=0.19 | p-trend=0.61 | p-trend=0.70 | p-trend=0.85 | p-trend=0.31 | p-trend=0.80 | |||||||||||

| Phenoxy herbicides 10 studies: BCMM, ENGELA, Epilymph, Italian, LANHL, LAMMCC, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW, Yale |

Never | 9256 | 8834 | 1524 | 2089 | 1509 | 1518 | 1327 | 433 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | |||||||

| Ever | 370 | 395 | 1.12 (0.90–1.38) | 114 | 1.05 (0.73–1.50) | 71 | 1.04 (0.73–1.49) | 78 | 0.75 (0.52–1.11) | 63 | 1.28 (0.87–1.88) | 28 | 1.43 (0.85–2.40) | 23 | 1.85 (0.98–3.48) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 188 | 195 | 1.11 (0.86–1.42) | 60 | 1.12 (0.74–1.69) | 31 | 0.93 (0.59–1.47) | 42 | 0.80 (0.51–1.24) | 27 | 1.10 (0.68–1.79) | 13 | 1.25 (0.62–2.51) | 11 | 1.61 (0.75–3.46) | ||

| >8 to 25.5 | 105 | 120 | 1.22 (0.89–1.67) | 35 | 1.07 (0.65–1.75) | 22 | 1.19 (0.70–2.04) | 19 | 0.68 (0.38–1.22) | 25 | 1.81 (1.06–3.08) | 5 | 1.46 (0.52–4.15) | 9 | 2.53 (1.08–5.93) | ||

| >25.5 | 70 | 72 | 1.01 (0.69–1.46) | 18 | 0.84 (0.46–1.53) | 16 | 1.20 (0.65–2.23) | 14 | 0.71 (0.36–1.38) | 10 | 1.01 (0.49–2.09) | 10 | 1.78 (0.74–4.27) | 2 | 0.89 (0.20–4.01) | ||

| p-trend=0.71 | p-trend=0.57 | p-trend=0.42 | p-trend=0.25 | p-trend=0.38 | p-trend=0.15 | p-trend=0.49 | |||||||||||

| 2,4-D 7 studies: BCMM, Epilymph, Italian, LANHL, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW |

Never | 7908 | 7477 | 1371 | 1814 | 1335 | 1391 | 836 | 379 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Other phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | |||||||

| Ever | 287 | 300 | 1.10 (0.85–1.43) | 103 | 1.14 (0.76–1.70) | 51 | 1.10 (0.70–1.74) | 66 | 0.89 (0.57–1.38) | 50 | 1.44 (0.89–2.32) | 9 | 1.19 (0.43–3.29) | 12 | 0.62 (0.26–1.44) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 150 | 150 | 1.06 (0.79–1.44) | 58 | 1.20 (0.77–1.88) | 21 | 0.93 (0.53–1.64) | 35 | 0.88 (0.53–1.46) | 22 | 1.19 (0.67–2.11) | 3 | 0.55 (0.13–2.34) | 7 | 0.73 (0.28–1.90) | ||

| >8 to 25.5 | 88 | 95 | 1.14 (0.79–1.64) | 30 | 1.02 (0.59–1.75) | 18 | 1.32 (0.70–2.46) | 16 | 0.72 (0.37–1.37) | 21 | 1.96 (1.05–3.67) | 6 d | 2.54 (0.68–9.53) | 5 d | 0.51 (0.17–1.55) | ||

| >25.5 | 45 | 51 | 1.14 (0.71–1.83) | 15 | 1.18 (0.58–2.41) | 11 | 1.47 (0.67–3.21) | 13 | 1.19 (0.56–2.52) | 6 | 1.06 (0.40–2.81) | ||||||

| p-trend=0.49 | p-trend=0.91 | p-trend=0.21 | p-trend=0.92 | p-trend=0.32 | p-trend=0.18 | p-trend=0.27 | |||||||||||

| Other phenoxy herbicides 7 studies: BCMM, Epilymph, Italian, LANHL, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW |

Never | 8385 | 7971 | 1460 | 1850 | 1388 | 1423 | 1114 | 383 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, 2,4-D, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | |||||||

| Ever | 88 | 81 | 0.85 (0.61–1.19) | 14 | 0.67 (0.36–1.25) | 15 | 0.85 (0.47–1.56) | 13 | 0.80 (0.42–1.52) | 18 | 0.83 (0.46–1.50) | 6 | 0.65 (0.21–1.97) | 8 | 2.71 (1.16–6.33) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤6.5 years | 50 | 33 | 0.63 (0.40–1.00) | 7 | 0.54 (0.23–1.26) | 6 | 0.63 (0.26–1.53) | 5 | 0.48 (0.18–1.25) | 6 | 0.59 (0.24–1.46) | - | 4 | 2.60 (0.85–7.95) | |||

| >6.5 | 37 | 46 | 1.13 (0.71–1.79) | 7 | 0.92 (0.39–2.17) | 8 | 1.05 (0.46–2.38) | 8 | 1.41 (0.61–3.26) | 11 | 1.01 (0.47–2.17) | 4 | 2.94 (0.94–9.23) | ||||

| p-trend=0.77 | p-trend=0.69 | p-trend=0.98 | p-trend=0.56 | p-trend=0.96 | p-trend=0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Glyphosate 8 studies: BCMM, ENGELA, Epilymph, Italian, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW, Yale |

Never | 8636 | 8241 | 1532 | 1968 | 1457 | 1435 | 1066 | 437 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Any other pesticide | |||||||

| Ever | 340 | 345 | 1.03 (0.83–1.29) | 106 | 0.91 (0.63–1.30) | 60 | 0.96 (0.66–1.42) | 91 | 1.42 (0.98–2.05) | 46 | 0.97 (0.63–1.49) | 14 | 0.74 (0.38–1.46) | 18 | 0.99 (0.50–1.99) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 207 | 219 | 1.11 (0.87–1.43) | 71 | 1.04 (0.70–1.53) | 38 | 1.04 (0.67–1.59) | 66 | 1.66 (1.12–2.45) | 21 | 0.77 (0.45–1.31) | 7 | 0.66 (0.27–1.63) | 11 | 1.00 (0.46–2.18) | ||

| >8 to 15.5 | 69 | 68 | 0.96 (0.65–1.42) | 23 | 0.88 (0.49–1.57) | 12 | 0.92 (0.47–1.84) | 12 | 0.89 (0.44–1.79) | 13 | 1.30 (0.66–2.59) | 2 | 0.80 (0.17–3.66) | 5 | 1.29 (0.44–3.75) | ||

| >15.5 | 56 | 55 | 0.90 (0.59–1.37) | 12 | 0.57 (0.28–1.16) | 9 | 0.78 (0.36–1.69) | 12 | 1.06 (0.52–2.17) | 11 | 1.34 (0.64–2.80) | 5 | 0.85 (0.28–2.60) | 2 | 0.65 (0.14–3.01) | ||

| p-trend=0.54 | p-trend=0.12 | p-trend=0.51 | p-trend=0.64 | p-trend=0.27 | p-trend=0.68 | p-trend=0.83 | |||||||||||

| Triazine herbicides 6 studies: BCMM, ENGELA, Epilymph, Italian, Mayo, NCISEER |

Never | 8050 | 7591 | 1491 | 1802 | 1370 | 1366 | 895 | 399 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | |||||||

| Ever | 220 | 222 | 0.91 (0.70–1.18) | 81 | 1.05 (0.71–1.55) | 38 | 0.88 (0.55–1.39) | 42 | 0.75 (0.48–1.17) | 35 | 0.94 (0.58–1.54) | 6 | 0.75 (0.28–2.01) | 12 | 0.91 (0.40–2.04) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤10 years | 114 | 108 | 0.86 (0.62–1.20) | 40 | 0.99 (0.61–1.59) | 17 | 0.78 (0.43–1.42) | 19 | 0.61 (0.34–1.08) | 18 | 0.98 (0.54–1.80) | 3 | 1.22 (0.32–4.63) | 7 | 1.03 (0.40–2.69) | ||

| >10 | 105 | 113 | 0.95 (0.69–1.32) | 41 | 1.11 (0.70–1.78) | 20 | 0.95 (0.54–1.67) | 23 | 0.93 (0.53–1.61) | 17 | 0.93 (0.50–1.72) | 3 | 0.53 (0.14–2.00) | 5 | 0.79 (0.27–2.27) | ||

| p-trend=0.86 | p-trend=0.65 | p-trend=0.93 | p-trend=0.96 | p-trend=0.81 | p-trend=0.36 | p-trend=0.64 | |||||||||||

| Atrazine 3 studies: Italian, Mayo, NCISEER |

Never | 5183 | 5235 | 930 | 1195 | 1076 | 967 | 250 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | ||||||||

| Ever | 178 | 174 | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) | 67 | 0.93 (0.61–1.43) | 26 | 0.68 (0.40–1.17) | 36 | 0.68 (0.42–1.10) | 27 | 0.90 (0.52–1.56) | - | 9 | 0.85 (0.33–2.15) | |||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 96 | 86 | 0.77 (0.53–1.11) | 36 | 0.88 (0.53–1.46) | 10 | 0.51 (0.24–1.07) | 17 | 0.56 (0.30–1.03) | 12 | 0.78 (0.38–1.59) | - | 6 | 1.02 (0.35–2.94) | |||

| >8 | 80 | 87 | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) | 31 | 1.00 (0.59–1.70) | 15 | 0.84 (0.44–1.61) | 19 | 0.85 (0.46–1.55) | 15 | 1.07 (0.55–2.09) | 3 | 0.64 (0.17–2.42) | ||||

| p-trend=0.88 | p-trend=0.96 | p-trend=0.70 | p-trend=0.71 | p-trend=0.79 | p-trend=0.51 | ||||||||||||

| Amide herbicides 4 studies: ENGELA, Italian, Mayo, NCISEER |

Never | 5266 | 5269 | 1034 | 1306 | 1132 | 1035 | 270 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | ||||||||

| Ever | 171 | 153 | 0.74 (0.55–1.00) | 61 | 0.85 (0.55–1.31) | 22 | 0.58 (0.33–1.00) | 30 | 0.59 (0.36–0.99) | 19 | 0.61 (0.34–1.10) | - | 10 | 1.14 (0.46–2.82) | |||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 92 | 94 | 0.86 (0.60–1.24) | 43 | 1.11 (0.68–1.82) | 12 | 0.65 (0.33–1.31) | 16 | 0.57 (0.31–1.07) | 9 | 0.55 (0.25–1.20) | - | - | - | |||

| >8 | 77 | 56 | 0.59 (0.40–0.89) | 17 | 0.54 (0.29–1.00) | 9 | 0.47 (0.22–1.01) | 14 | 0.65 (0.34–1.27) | 9 | 0.62 (0.28–1.34) | ||||||

| p-trend=0.01 | p-trend=0.05 | p-trend=0.05 | p-trend=0.20 | p-trend=0.20 | |||||||||||||

| Alachlor 3 studies: Italian, Mayo, NCISEER |

Never | 4181 | 4207 | 893 | 976 | 838 | 848 | 227 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | ||||||||

| Ever | 126 | 123 | 0.84 (0.60–1.18) | 53 | 0.96 (0.60–1.51) | 16 | 0.58 (0.30–1.09) | 25 | 0.63 (0.36–1.10) | 15 | 0.79 (0.40–1.55) | - | 8 | 1.47 (0.53–4.12) | |||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 79 | 84 | 0.92 (0.62–1.35) | 39 | 1.11 (0.67–1.86) | 10 | 0.62 (0.29–1.33) | 16 | 0.64 (0.33–1.21) | 7 | 0.58 (0.24–1.40) | - | - | - | |||

| >8 | 44 | 36 | 0.70 (0.43–1.16) | 13 | 0.69 (0.34–1.39) | 5 | 0.46 (0.17–1.24) | 9 | 0.67 (0.30–1.48) | 7 | 1.07 (0.44–2.63) | ||||||

| p-trend=0.19 | p-trend=0.48 | p-trend=0.07 | p-trend=0.16 | p-trend=0.71 | |||||||||||||

| Trifluralin 6 studies: BCMM, Italian, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW, Yale |

Never | 5919 | 6052 | 1016 | 1388 | 1229 | 1053 | 742 | 295 | OP insecticides, | |||||||

| Ever | 148 | 130 | 0.75 (0.55–1.00) | 47 | 0.85 (0.55–1.32) | 21 | 0.70 (0.41–1.21) | 19 | 0.41 (0.24–0.72) | 21 | 0.81 (0.46–1.41) | 5 | 1.07 (0.38–3.05) | 8 | 0.96 (0.39–2.37) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 87 | 76 | 0.77 (0.53–1.11) | 34 | 0.99 (0.60–1.63) | 8 | 0.49 (0.22–1.08) | 11 | 0.40 (0.20–0.79) | 12 | 0.89 (0.44–1.80) | 2 | 1.17 (0.25–5.54) | 5 | 1.05 (0.36–3.07) | ||

| >8 | 60 | 50 | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) | 13 | 0.63 (0.32–1.25) | 11 | 0.81 (0.40–1.64) | 7 | 0.39 (0.17–0.91) | 8 | 0.65 (0.29–1.45) | 3 | 0.96 (0.26–3.61) | 3 | 0.83 (0.23–3.01) | ||

| p-trend=0.05 | p-trend=0.19 | p-trend=0.49 | p-trend=0.02 | p-trend=0.29 | p-trend=0.97 | p-trend=0.78 | |||||||||||

| Dicamba 4 studies: Italian, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW |

Never | 5602 | 5657 | 948 | 1337 | 1126 | 1076 | 254 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | ||||||||

| Ever | 131 | 120 | 0.79 (0.57–1.10) | 49 | 0.87 (0.55–1.38) | 16 | 0.60 (0.32–1.14) | 25 | 0.64 (0.37–1.10) | 18 | 0.92 (0.49–1.74) | - | 6 | 0.78 (0.27–2.22) | |||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤8 years | 75 | 71 | 0.79 (0.53–1.18) | 35 | 1.04 (0.61–1.76) | 7 | 0.46 (0.19–1.08) | 13 | 0.55 (0.28–1.08) | 10 | 0.90 (0.41–1.96) | - | 3 | 0.62 (0.16–2.35) | |||

| >8 | 54 | 46 | 0.77 (0.49–1.21) | 13 | 0.61 (0.30–1.22) | 8 | 0.76 (0.33–1.74) | 11 | 0.76 (0.36–1.59) | 8 | 1.00 (0.43–2.33) | 3 | 1.08 0.28–4.15) | ||||

| p-trend=0.25 | p-trend=0.16 | p-trend=0.48 | p-trend=0.45 | p-trend=1.00 | p-trend=0.92 | ||||||||||||

| Pendimethalin 3 studies: Italian, Mayo, NCISEER |

Never | 4250 | 4272 | 921 | 982 | 855 | 857 | 230 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | ||||||||

| Ever | 57 | 58 | 0.94 (0.61–1.44) | 25 | 1.11 (0.63–1.94) | 10 | 1.03 (0.48–2.21) | 8 | 0.48 (0.21–1.07) | 6 | 0.67 (0.27–1.70) | - | 5 | 1.92 (0.61–6.04) | |||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤4 years | 33 | 23 | 0.63 (0.35–1.14) | 11 | 0.82 (0.38–1.76) | 3 | 0.52 (0.15–1.81) | 4 | 0.40 (0.14–1.21) | - | - | - | |||||

| >4 | 24 | 31 | 1.16 (0.64–2.07) | 14 | 1.44 (0.69–3.01) | 5 | 1.19 (0.42–3.35) | 4 | 0.57 (0.19–1.73) | ||||||||

| p-trend=0.97 | p-trend=0.47 | p-trend=0.96 | p-trend=0.14 | ||||||||||||||

| Paraquat 5 studies: BCMM, Italian, Mayo, NCISEER, NSW |

Never | 5335 | 5378 | 993 | 1216 | 1104 | 987 | 565 | 257 | OP insecticides, OC insecticides, Phenoxy herbicides, Glyphosate, Any other pesticide | |||||||

| Ever | 26 | 31 | 1.17 (0.67–2.04) | 4 | 0.58 (0.19–1.74) | 5 | 1.09 (0.40–2.98) | 8 | 1.44 (0.61–3.41) | 7 | 1.48 (0.60–3.64) | 3 | 2.03 (0.34–12.3) | 2 | 1.68 (0.36–7.81) | ||

| Duration | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤4.5 years | 15 | 13 | 1.01 (0.47–2.19) | 2 | 0.50 (0.11–2.23) | - | 4 | 1.32 (0.42–4.18) | 3 | 1.60 (0.43–5.97) | - | - | |||||

| >4.5 | 11 | 17 | 1.26 (0.57–2.78) | 2 | 0.72 (0.15–3.55) | 4 | 1.61 (0.46–5.66) | 4 | 1.42 (0.43–4.70) | ||||||||

| p-trend=0.58 | p-trend=0.53 | p-trend=0.42 | p-trend=0.52 | ||||||||||||||

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from logistic regression models, with adjustment for study center, age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), race/Hispanic ethnicity, farming work history, and a set of covariates for use of other pesticides

Three-category duration variable results are shown if there were at least 50 exposed NHL cases in the highest category; otherwise, two-category duration results are shown

p-value for a continuous variable with values set as the median of each duration category

Categories collapsed if included 0 or 1 cases

Table 4.

Associations between occupational herbicide use and risk of all NHL (odds ratios [OR] & 95% confidence intervals [CI]).a Lagged exposure windows and decades of use for selected herbicides.

| Herbicides | Phenoxy herbicides | 2,4-D | Other phenoxy herbicides | Glyphosate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | Cases | OR (95% CI) | |

| Lagged exposure windowsb,c | ||||||||||

| >0–5 years | 202 | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) | 100 | 1.55 (0.99–2.42) | 60 | 1.53 (0.83–2.84) | 19 | 0.54 (0.16–1.82) | 146 | 0.85 (0.60–1.20) |

| >5–10 years | 222 | 0.91 (0.64–1.29) | 106 | 0.72 (0.44–1.18) | 75 | 0.76 (0.41–1.41) | 23 | 2.20 (0.53–9.08) | 169 | 1.14 (0.78–1.67) |

| >10–20 years | 318 | 1.20 (0.92–1.56) | 170 | 1.02 (0.72–1.44) | 138 | 0.97 (0.66–1.43) | 34 | 1.18 (0.49–2.83) | 199 | 1.08 (0.79–1.49) |

| >20 years | 445 | 0.92 (0.75–1.12) | 290 | 1.00 (0.79–1.28) | 234 | 1.03 (0.78–1.36) | 68 | 0.75 (0.50–1.12) | 146 | 0.84 (0.62–1.13) |

| Decades of usec | ||||||||||

| Before 1960 | 162 | 0.81 (0.61–1.09) | 99 | 0.73 (0.51–1.04) | 73 | 0.70 (0.46–1.06) | 22 | 0.53 (0.27–1.02) | 0 | - |

| 1960s | 281 | 1.31 (0.98–1.75) | 182 | 1.41 (0.99–1.99) | 139 | 1.57 (1.05–2.35) | 51 | 1.59 (0.89–2.84) | 0 | - |

| 1970s | 337 | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 206 | 1.09 (0.77–1.55) | 168 | 1.12 (0.76–1.65) | 49 | 0.73 (0.39–1.38) | 107 | 1.17 (0.82–1.65) |

| 1980s | 361 | 1.03 (0.79–1.36) | 193 | 0.78 (0.55–1.12) | 158 | 0.77 (0.52–1.15) | 36 | 2.69 (1.06–6.81) | 178 | 0.85 (0.63–1.16) |

| 1990s | 295 | 0.82 (0.63–1.06) | 155 | 0.99 (0.69–1.42) | 113 | 0.93 (0.60–1.44) | 16 | 0.32 (0.11–0.94) | 222 | 0.85 (0.62–1.15) |

| 2000s or later | 121 | 1.78 (1.26–2.52) | 63 | 1.30 (0.82–2.07) | 49 | 1.32 (0.76–2.28) | 3 | 0.79 (0.15–4.15) | 132 | 1.24 (0.87–1.76) |

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from logistic regression models, with adjustment for study center, age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), race/Hispanic ethnicity, farming work history, and a set of covariates for use of other pesticides

Exposure windows for timing of herbicide use before the reference date (diagnosis date for cases or corresponding reference date for controls)

Modeled as a set of indicator variables; participants could be exposed in multiple lagged exposure windows or decades

Phenoxy herbicides and 2,4-D, specifically, were associated with non-significantly increased risks of several NHL subtypes. The most consistent associations were observed by increasing duration of use for phenoxy herbicides with MM (>25.5 years, OR=1.78, 95% CI: 0.74–4.27; p-trend=0.15) and 2,4-D with DLBCL (>25.5 years, OR=1.47, 95% CI: 0.67–3.21; p-trend=0.21). Associations with any phenoxy herbicides and 2,4-D were generally less strong when exposure was lagged by 10 years (Supplemental Table 2); likewise, the strongest associations were estimated for exposures within 5 years before diagnosis (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 2). An association between phenoxy herbicides and TCL (OR=1.85, 95% CI: 0.98–3.48) was explained by an association with other (i.e., non-2,4-D) phenoxy herbicides (OR=2.71, 95% CI: 1.16–6.33). Analysis of lagged exposure windows showed the highest ORs for TCL with exposures occurring 10–20 or >20 years before diagnosis, and associations with longer duration were strongest with a 10-year lag (>6 years, OR=3.24, 95% CI: 1.02–10.2; p-trend=0.04). The highest increased risks of all NHL were estimated for phenoxy herbicide or 2,4-D use that occurred in the 1960s – a pattern also observed for 2,4-D use in association with DLBCL (use in 1960s, OR=3.02, 95% CI: 1.50–6.09). In contrast, the association between phenoxy herbicide use and MM was strongest for use that occurred in the 2000s or later, based on 5 exposed cases (OR=3.60, 95% CI: 0.94–13.7). Use of other phenoxy herbicides in the 1980s was associated with increased risk of all NHL (Table 4) and use in the 1970s was most strongly associated with increased risk of TCL (7 exposed cases, OR=3.29, 95% CI: 0.70–15.4).

Glyphosate use was not associated with all NHL in our main analysis (OR=1.03, 95% CI: 0.83–1.29). An association between glyphosate use and FL was somewhat stronger when lagged by 10 years (OR=1.48, 95% CI: 0.98–2.25, Supplemental Table 2) and this association was limited to shorter-duration exposures (≤8 years, OR=1.80, 95% CI: 1.15–2.82; >8 years, OR=1.00, 95% CI: 0.55–1.83). Non-statistically significant risk increases were also estimated for OBCL and TCL in association with mid-level or longest duration categories of glyphosate use. The association between glyphosate use and FL was strongest for use during the 1970s (OR=1.21, 95% CI: 0.70–2.09), whereas the association with all NHL was highest for use in the 2000s or later (OR=1.24, 95% CI: 0.87–1.76).

None of the other herbicide groups or active ingredients examined were associated with increased risk of NHL. Inverse associations, some statistically significant, were estimated for amide herbicides and trifluralin. Some elevated ORs were observed in association with paraquat use, based on small numbers.

Selected meta-analysis forest plots are shown in Supplemental Figure 1. Meta-analysis confirmed weak associations of ever-use of any herbicide, phenoxy herbicides, or 2,4-D with all NHL, with little or moderate heterogeneity of effect between studies. An association between any herbicide use and TCL was slightly stronger in meta-analysis (mOR=1.69, 95% CI: 1.00–2.86, p-het=0.65) than pooled analysis. The association between glyphosate and all NHL from meta-analysis was stronger for lagged-use (mOR=1.38, 95% CI: 0.79–2.42, p-het=0.07) than ever-use (mOR=1.02, 0.70–1.48, p-het=0.17), although both analyses revealed moderate heterogeneity between studies. Associations were higher from meta-analysis than pooled analysis and showed little heterogeneity for lagged glyphosate use with NHL subtypes FL (mOR=2.20, 95% CI: 1.00–4.87, p-het=0.20) and TCL (mOR=2.58, 95% CI: 0.60–11.1, p-het=0.28), and phenoxy herbicide use duration >8 years with MM (mOR=2.33, 95% CI: 0.81–6.66, p-het=0.32). Results were similar between meta-analysis and pooled analysis and there was little heterogeneity for longer-duration 2,4-D use (>8 years) in association with DLBCL and OBCL.

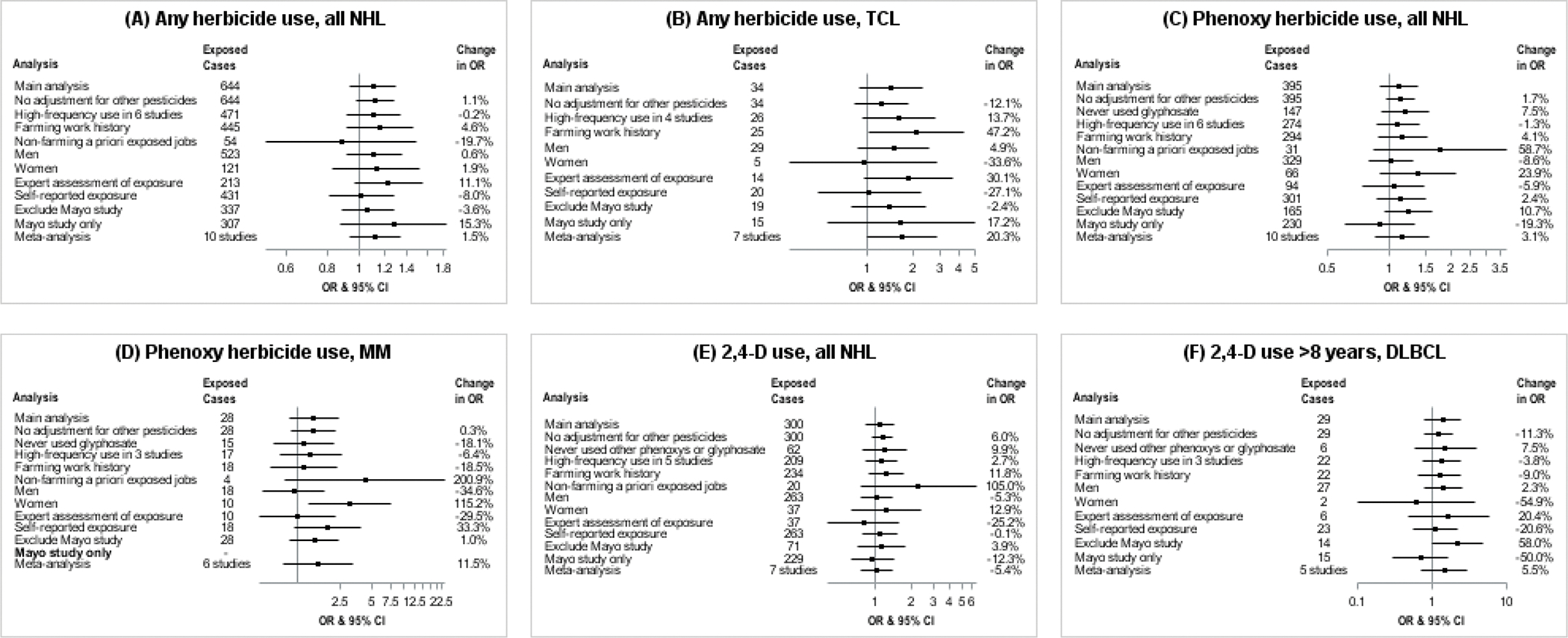

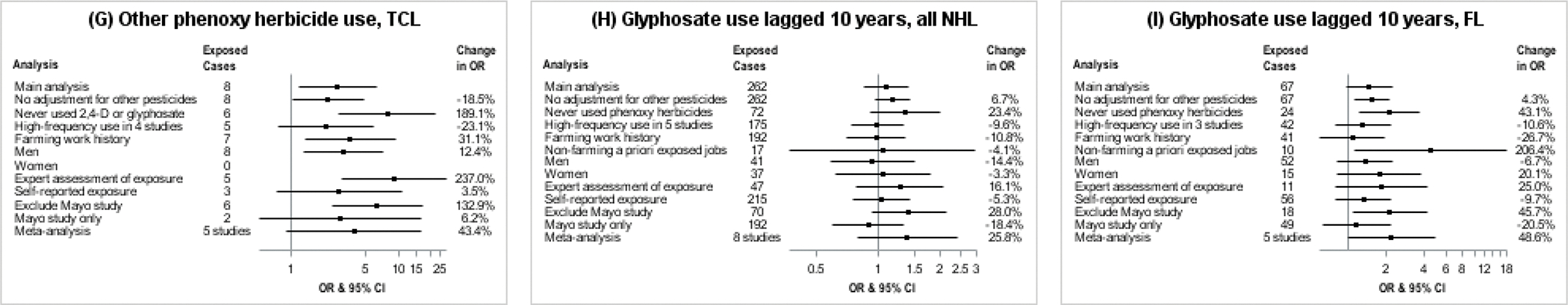

Sensitivity analyses (Figure 1) revealed generally small (<10% change in OR from main model) or modest (10–20% change in OR) magnitudes of confounding by other pesticides (Supplemental Table 3). Exclusion of participants with potentially confounding exposures to other herbicides typically resulted in stronger associations for phenoxy herbicides and glyphosate in relation to NHL and subtypes, except the association between phenoxy herbicides and MM was diminished. Limiting to relatively high frequency of use in the studies that collected this information had little impact on most results, with exception of slightly lowering ORs for associations of glyphosate with all NHL and FL. Several associations were stronger (higher ORs) when limiting to participants who ever worked on a farm, such as 2,4-D use with all NHL and other phenoxy herbicides with TCL, although associations with glyphosate were diminished. The association between lagged glyphosate use and FL was observed only among participants with non-farming jobs. Notable differences by gender were higher risk estimates among women for NHL associations with any phenoxy herbicide and 2,4-D. In contrast, associations of any herbicide and other phenoxy herbicides with TCL were limited to men. Associations were generally stronger in studies with expert assessment of exposure than with exposure based on self-report.

Figure 1.

Sensitivity and alternative analyses of selected associations between occupational herbicide use and risk of NHL and NHL subtypes (odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from logistic regression models, with adjustment for study center, age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), race/Hispanic ethnicity, farm work history, and a set of covariates for use of other pesticides). NHL subtypes: DLBCL=diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL=follicular lymphoma; MM=multiple myeloma; TCL=T-cell lymphoma. “Change in OR” refers to the OR change from the listed alternative/sensitivity analysis compared with the OR from the main analysis.

Associations were generally more strongly positive with exclusion of the Mayo Study (Figure 1 & Supplemental Table 4). These results differ from our main results with more suggestive duration-response trends for any herbicide with TCL and MM, and for phenoxy herbicides and 2,4-D with all NHL and several subtypes. For example, elevated ORs were estimated for 2,4-D use duration >8 years in association with all NHL (OR=1.48, 95% CI: 0.86–2.56, p-trend=0.14), DLBCL (OR=2.16, 95% CI: 0.97–4.81, p-trend=0.05), FL (OR=2.16, 95% CI: 0.91–5.11, p-trend=0.07), OBCL (OR=2.15, 95% CI: 0.88–5.26, p-trend=0.12) and MM (OR=2.62, 95% CI: 0.68–10.1, p-trend=0.17). Associations with glyphosate lagged-use were considerably stronger with exclusion of the Mayo study, for all NHL (OR=1.40, 95% CI: 0.93–2.13), FL (OR=2.16, 95% CI: 1.10–4.24), and OBCL (OR=1.92, 95% CI: 0.95–3.89).

DISCUSSION

In our consortium-based analysis of data pooled from ten case-control studies, we found no substantial association of any herbicide, herbicide groups, or individual active ingredients with risk of all NHL. Elevations in risk by increasing duration of 2,4-D use were observed for all NHL, DLBCL and OBCL, but ORs were generally imprecise. An association between glyphosate use and increased risk of FL was fairly consistent among the studies; this association was particularly elevated in analyses of glyphosate exposure lagged by 10 years and with shorter duration of use. Sensitivity analyses revealed diminished associations for glyphosate in participants with high-frequency herbicide use or among those who ever worked on a farm, and generally stronger associations for 2,4-D and glyphosate among those who worked in nonfarming jobs, such as gardening. Results were also sensitive to exclusion of the largest study in the pooled analysis, with higher estimated risks after the exclusion.

Phenoxy herbicides are a widely used group of herbicides, of which 2,4,5-T received much attention because of inherent contamination with the carcinogenic “dioxin”, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-para-dioxin (TCDD). While 2,4,5-T has been banned in most countries, 2,4-D continues to be used worldwide.26 As noted in the IARC review, several previous studies reported an association between 2,4-D use and NHL (including the Italian study in our pooled analysis12), although risk estimates were sensitive to adjustment for other pesticides, decreasing confidence in the evidence.2 More recent studies which adjusted for other pesticides found no association between 2,4-D use and all NHL, including the Agricultural Health Study (AHS) cohort, individually,27 and as part of a meta-analysis of three prospective agricultural cohorts with exposure assignment using a crop-exposure matrix or self-report (AGRICOH).28 In our analysis with adjustment for other pesticides, we found weak trends of increasing risk with longer duration of 2,4-D use for all NHL and several B-cell NHL subtypes. This result is in line with a meta-analysis that estimated increased risk from 2,4-D when considering only ‘high’ exposures, based on factors such as duration, frequency, and intensity.29 Our analysis further revealed that these associations were strongest for use in the 1960s, possibly suggesting risk linked with early production of 2,4-D that typically resulted in low levels of dioxin contamination – an issue that was largely resolved by improvement of production methods in the late 1980s.30 Our novel finding of an association between other (non-2,4-D) phenoxy herbicides and TCL is plausible based on high levels of dioxin contamination in 2,4,5-T, which was severely restricted for use and subsequently banned by regulatory bodies in the countries of our pooled study in the 1970s and 1980s. This timeline corresponds with elevated ORs we observed in association with other phenoxy herbicide use in the 1970s and 1980s for TCL and all NHL (1980s only), and no risk increases with use in later decades.

Our study adds to existing data on the relationship between glyphosate use and risk of NHL with analysis of a large, pooled study population and inclusion of 6 studies (BCMM, Italian, Mayo, NCI-SEER, NSW, Yale) which did not previously report on glyphosate (as well as 2 studies which did previously report on the association: ENGELA and Epilymph). We found little evidence of an association between glyphosate use and all NHL, and meta-analysis indicated substantial heterogeneity of effect among the studies. Our findings for all NHL agree with recent, large studies, including an updated analysis of the AHS cohort that reported only small, non-significant increases in NHL risk with higher intensity-weighted lifetime days of use, lagged by 20 years (55 cases, OR=1.12, 95% CI: 0.83–1.51 for the highest vs. lowest quartile),31 and the AGRICOH meta-analysis of three cohorts (including the AHS) that found no association between ever-use and all NHL (OR=0.95, 95% CI: 0.77–1.18).28 A pooled analysis of case-control studies conducted in North America (not including studies in our analysis) found no association between glyphosate use and all NHL for ever-use or duration, but estimated increased risk in association with use frequency >2 days/year (30 cases, OR=1.73, 95% CI: 1.02–2.94).32 A meta-analysis that evaluated NHL risk in association with ‘high’ glyphosate exposure – defined according to highest intensity, duration, frequency and/or exposure latency (i.e., ‘lag’) assessed in the studies – estimated 17% increased risk of NHL in association with exposure.33 In contrast, in our study, associations between glyphosate use and all NHL did not increase by duration and diminished with consideration of high-frequency use. We did find somewhat stronger associations with exposure lagged by 10 years, but our analysis of exposure windows revealed no association with exposure lagged by 20 years.

In analyses of NHL subtypes, we found an association between glyphosate use and FL that was somewhat stronger when lagged by 10 years. The association with FL was also stronger with shorter duration, contrary to our general hypothesis of increasing risk with longer duration of exposure to carcinogens. Nevertheless, similar results were reported in a recent case-control study conducted in Italy from 2011–2017 (after the Italian study in our analysis), in which higher ORs were estimated in association with shorter duration of glyphosate use (≤16 years in that study) for all NHL, B-cell lymphoma, and FL.34 In subtype analyses of the pooled North American study (referenced above), glyphosate use was not associated with risk of FL, but increased risks were estimated in relation to DLBCL for lower duration and higher frequency.32 An association with DLBCL was not apparent in our study. No subtype-specific associations were found for glyphosate use in the AHS.31 We can only speculate on a reason for stronger associations found with shorter duration in our study and others, but such a pattern could occur if participants with fewer years of use had more intense exposures. Changes in glyphosate use patterns include more widespread use (greater use prevalence) and much heavier use (greater amounts applied) in the 1990s and 2000s, compared with the early years of use after market introduction in 1974.35 More widespread and heavier use in later years could correspond with greater exposure intensity in periods of shorter duration. According to these use patterns and if there was a causal association between glyphosate and NHL, then we would expect to see the highest ORs for use in the later decades, as observed for NHL and some subtypes (small or imprecise elevated ORs) for use in the 2000s. However, the association between glyphosate and FL was only elevated for use in the 1970s.

Our analysis suggested different latencies (lags) for the various herbicide exposures and NHL subtypes. While associations between glyphosate and FL were strongest for the herbicide use 10–20 years before diagnosis, more recent exposures appeared relevant for other subtypes including DLBCL and TCL (based on small numbers) – and such different latencies could account for discrepant results among studies. Associations with 2,4-D were generally strongest for recent use within 5 years of diagnosis, suggesting possible carcinogenicity through a late-stage biological mechanism. However, longer latencies were found to be most relevant for the ‘other’ (non-2,4-D) phenoxy herbicides, perhaps suggesting a different mechanism than 2,4-D.

A strong influence of the Mayo Study was evident in our analysis. Not only was the Mayo population the largest examined, the reported use of herbicides was also higher than other studies (consistent with extensive agriculture in the upper Midwest and similar to other published reports from the region36) – amounting to more than half of the exposed participants in many pooled analyses. While associations observed in the Mayo Study were in line with the other studies, they tended to be lower, as evidenced by our sensitivity analysis excluding this study that generally produced higher ORs than the main analysis. Future investigation of heterogeneity of effect among the studies, seen for some associations (e.g., glyphosate and all NHL), may shed light on regional exposure differences to consider in future analyses.

A major strength of our study is the large pooled sample, from which we characterized a broad spectrum of occupational herbicide use, in both farming and non-farming jobs. Nevertheless, assessment of pesticide exposure is challenging, given the many different pesticide products and the importance of long-term exposure information in studies of cancer – necessitating long, detailed questionnaires to adequately capture the relevant information. Poor reporting is a particular issue when exposure data are collected retrospectively via questionnaire, as for the case-control studies in our pooled analysis, due to concern of biased recall (i.e., enhanced recall of exposure by cases, leading to falsely elevated risk estimates). We do not believe recall bias greatly affected our results, as none of the herbicides examined were significantly associated with increased risk of all NHL. However, open-ended questionnaire items to elicit self-reported exposures have been found to elicit more biased responses,37 and this suggests a greater possibility of recall bias from some studies than others – namely, those with open-ended elicitation of exposures in any job (Yale, NCI-SEER), compared to studies with questionnaire items on specific exposures (LACCMM, Mayo) or questionnaires that were designed for and administered only to participants in certain jobs like farming (ENGELA, Italian, Epilymph, NSW, BCMM). A higher risk of reporting or recall bias may also suspected for the Yale study because participants were asked about exposures at work or at home, in one questionnaire item. Such a bias may be reflected in the strong association between phenoxy herbicides and all NHL in the Yale study, but does not appear to have globally affected results, given no association in the Yale study for any herbicide use in relation to all NHL (Supplemental Figure 1). Our pooled study is also susceptible to selection bias that may have occurred in the individual studies, given that participation in the studies was low to moderate (generally between 40–70%).38 Differential selection/participation of subjects by both NHL status and pesticide exposures could bias results in either direction – for example, possibly causing the inverse associations (ORs below 1.0) we observed for some pesticides.

We capitalized on our pooling strategy to harmonize herbicide variables across the individual studies, including ever-use, duration, decades of use, and lagged exposures. We also considered use frequency (e.g., days/year) in the studies that assessed it. Although duration was consistently available across the studies, it is only one component of cumulative exposure that does not necessarily correspond with exposure intensity. Unfortunately, the level of detail and types of information available in the studies was not optimal for harmonizing a measure of exposure intensity across studies. Another advantage of pooling is that the approach enabled consistent adjustment for other pesticides across the studies and adequately-powered subgroup analyses. Our results suggested, at most, modest confounding by other pesticides. Overadjustment is also a concern, although this may be less of an issue in more homogeneous subgroups, such as farmers. Results for subgroups that differed from our main analysis may suggest residual confounding, effect modification, or greater exposure intensity within the subgroup.

Our results add to the evidence on cancer risks from herbicide use, with suggestion of increased risks for DLBCL with longer duration 2,4-D exposure, and an association between glyphosate use and FL. These findings underscore the importance of estimating subtype-specific risks to clarify associations. Efforts by future studies to collect detailed information necessary for assessment of exposure intensity, frequency, and duration will allow estimation of cumulative exposure, which may be most relevant for carcinogenesis. Also, based on our findings, future research should consider lagged exposure windows that may differ between subtypes, as well as decades of exposure to evaluate the coherence of estimated associations with known herbicide use patterns. Although estimated risks in our study were somewhat variable between analyses, the implications are notable because of current-widespread use of these herbicides. Our results may contribute to future hazard assessments of herbicides by inclusion in meta-analyses of ever-more detailed associations for the frequently-assessed chemicals 2,4-D and glyphosate (such as to hone-in on subtype-specific associations with particular latencies) and by inclusion in simple meta-analyses of ever-use for the chemicals with limited human data (such as paraquat).

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES

What is already known on this topic?

Several widely-used herbicides have been classified by advisory or regulatory bodies in recent years as possible or probable human carcinogens, based on limited or inadequate evidence from epidemiologic studies and stronger evidence from animal bioassays and mechanistic studies.

Limitations of prior epidemiologic studies on this topic include assessment of simple exposure metrics such as ever-use that did not characterize dose or level of exposure, limited- or no adjustment for other herbicides or pesticides, and small sample sizes

What this study adds:

In our analysis of a large, pooled study population with assessment of lifetime occupational histories and adjustment of herbicide risk estimates for use of other pesticides, we found increased risks of NHL in association with longer-duration 2,4-D use.

Analysis of risks with glyphosate use, including 8 total studies with 6 that have not previously reported on glyphosate, found no association with all NHL and an association with follicular lymphoma that was limited to short-duration use.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

Our results support previous evidence for the carcinogenicity of 2,4-D.

The association we found between glyphosate use and follicular lymphoma, but not with all NHL, underscores the importance of estimating subtype-specific risks to clarify associations.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health [R03CA199515 to AJD]. The Mayo case-control study of non-Hodgkin lymphoma was also funded through grants from the National Cancer Institute [R01 CA92153 and P50CA97274].

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared.

DECLARATIONS

Ethics approval

Participants of the individual case-control studies provided informed consent for use of their data in research. The pooled study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Drexel University Office of Research (IRB ID: 1504003599).

Data availability

Original investigators of the individual case-control studies may be approached for collaborative use of the data included in the pooled analysis. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guyton KZ, Loomis D, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of tetrachlorvinphos, parathion, malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:490–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loomis D, Guyton K, Grosse Y, et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. Carcinogenicity of lindane, DDT, and 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:891–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Some Organophosphate Insecticides and Herbicides. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. DDT, Lindane, and 2,4-D. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein L, Ross RK. Prior medication use and health history as risk factors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: preliminary results from a case-control study in Los Angeles County. Cancer Res 1992;52(19 Suppl):5510s–15s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerhan JR, Fredericksen ZS, Wang AH, et al. Design and validity of a clinic-based case-control study on the molecular epidemiology of lymphoma. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 2011;2:95–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocco P, Satta G, Dubois S, et al. Lymphoma risk and occupational exposure to pesticides: results of the Epilymph study. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritschi L, Benke G, Hughes AM, et al. Occupational exposure to pesticides and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:849–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartge P, Colt JS, Severson RK, et al. Residential herbicide use and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:934–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koutros S, Baris D, Bell E, et al. Use of hair colouring products and risk of multiple myeloma among US women. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:68–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miligi L, Costantini AS, Bolejack V, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leukemia, and exposures in agriculture: results from the Italian multicenter case-control study. Am J Ind Med 2003;44:627–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miligi L, Costantini AS, Veraldi A, Benvenuti A, Vineis P. Cancer and pesticides: an overview and some results of the Italian multicenter case-control study on hematolymphopoietic malignancies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1076:366–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuyujukian DS, Voutsinas J, Bernstein L, Wang SS. Medication use and multiple myeloma risk in Los Angeles County. Cancer Causes Control 2014;25:1233–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orsi L, Delabre L, Monnereau A, et al. Occupational exposure to pesticides and lymphoid neoplasms among men: results of a French case-control study. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:291–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber L, Song K, Boyle T, et al. Organochlorine Levels in Plasma and Risk of Multiple Myeloma. J Occup Environ Med 2018;60:911–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Holford TR, Leaderer B, et al. Hair-coloring product use and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a population-based case-control study in Connecticut. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Diebold J, Müller-Hermelink HK. World Health Organization Classification of lymphomas: a work in progress. Ann Oncol 1998;9 Suppl 5:S25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morton LM, Sampson JN, Cerhan JR, et al. Rationale and Design of the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph) Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Subtypes Project. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2014;2014:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. , eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner JJ, Morton LM, Linet MS, et al. InterLymph hierarchical classification of lymphoid neoplasms for epidemiologic research based on the WHO classification (2008): update and future directions. Blood 2010;116:e90–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ILO International Labour Office. 1981. International Standard Classification of Occupations. Revised Edition 1968. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- 22.‘t Mannetje A, De Roos AJ, Boffetta P, et al. Occupation and Risk of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Its Subtypes: A Pooled Analysis from the InterLymph Consortium. Environ Health Perspect 2016;124:396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Roos AJ, Schinasi LH, Miligi L, et al. Occupational insecticide exposure and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A pooled case-control study from the InterLymph Consortium. Int J Cancer 2021. Nov 15;149:1768–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerro CC, Koutros S, Andreotti G, et al. Cancer incidence in the Agricultural Health Study after 20 years of follow-up. Cancer Causes Control 2019;30:311–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy SM, Koehoorn M. Exposure assessment in epidemiology: does gender matter? Am J Ind Med 2003. Dec;44:576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atwood D, Paisley-Jones C. 2017. Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage: 2008–2012 Market Estimates. Washington, DC, USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodman JE, Loftus CT, Zu K. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results from the Agricultural Health Study and an updated meta-analysis. Ann Epidemiol 2017;27:290–92.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leon ME, Schinasi LH, Lebailly P, et al. Pesticide use and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoid malignancies in agricultural cohorts from France, Norway and the USA: a pooled analysis from the AGRICOH consortium. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:1519–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith AM, Smith MT, La Merrill MA, Liaw J, Steinmaus C. 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis accounting for exposure levels. Ann Epidemiol 2017;27:281–9.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 1486, 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.gov/compound/2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic-acid. Accessed June 26, 2022.

- 31.Andreotti G, Koutros S, Hofmann JN, et al. Glyphosate Use and Cancer Incidence in the Agricultural Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110:509–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pahwa M, Beane Freeman LE, Spinelli JJ, et al. Glyphosate use and associations with non-Hodgkin lymphoma major histological sub-types: findings from the North American Pooled Project. Scand J Work Environ Health 2019;45:600–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Rana I, Shaffer RM, Taioli E, Sheppard L. Exposure to glyphosate-based herbicides and risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A meta-analysis and supporting evidence. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 2019;781:186–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meloni F, Satta G, Padoan M, et al. Occupational exposure to glyphosate and risk of lymphoma:results of an Italian multicenter case-control study. Environ Health 2021;20:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benbrook CM. Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environ Sci Eur 2016;28:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yiin JH, Ruder AM, Stewart PA, et al. Brain Cancer Collaborative Study Group. The Upper Midwest Health Study: a case-control study of pesticide applicators and risk of glioma. Environ Health 2012;11:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teschke K, Olshan AF, Daniels JL, et al. Occupational exposure assessment in case-control studies: opportunities for improvement. Occup Environ Med 2002. Sep;59:575–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morton LM, Sampson JN, Cerhan JR, Turner JJ, Vajdic CM, Wang SS, Smedby KE, de Sanjosé S, Monnereau A, Benavente Y, Bracci PM, Chiu BC, Skibola CF, Zhang Y, Mbulaiteye SM, Spriggs M, Robinson D, Norman AD, Kane EV, Spinelli JJ, Kelly JL, La Vecchia C, Dal Maso L, Maynadié M, Kadin ME, Cocco P, Costantini AS, Clarke CA, Roman E, Miligi L, Colt JS, Berndt SI, Mannetje A, de Roos AJ, Kricker A, Nieters A, Franceschi S, Melbye M, Boffetta P, Clavel J, Linet MS, Weisenburger DD, Slager SL. Rationale and Design of the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph) Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Subtypes Project. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014(48):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Original investigators of the individual case-control studies may be approached for collaborative use of the data included in the pooled analysis. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.