Abstract

HIV infection has multi-system adverse effects in children including on the growing skeleton. We aimed to determine the association between chronic HIV infection and bone architecture (density, size, strength) in peripubertal children. We conducted a cross-sectional study of children aged 8–16 years with HIV (CWH) on antiretroviral therapy (ART), and children without HIV (CWOH) recruited from schools, frequency matched for age strata and sex. Outcomes, measured by tibial peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography (pQCT), included 4% trabecular and 38% cortical volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD), 4% and 38% cross-sectional area (CSA), and 38% stress-strain index (SSI). Multivariable linear regression tested associations between HIV status and outcomes, stratified by sex and puberty (Tanner 1–2 vs. 3–5), adjusting for age, height, fat mass, physical activity, socio-economic and orphanhood statuses. We recruited 303 CWH and 306 CWOH; 50% female. Whilst CWH were similar in age to CWOH (overall mean±SD 12.4±2.5years), more were pre-pubertal (i.e Tanner 1; 41% vs. 23%). Median age at ART initiation was four (IQR 2–7) years, whilst median ART duration was eight (IQR 6–10) years. CWH were more often stunted (height-for-age Z-score<−2), than those without HIV (33% vs 7%). Both male and female CWH in later puberty had lower trabecular vBMD, CSA (4% and 38%) and SSI than those without HIV, whilst cortical density was similar. Adjustment explained some of these differences; however, deficits in bone size persisted in CWH in later puberty (HIV*puberty interaction p=0.035[males; 4% CSA] and p=0.029[females; 38% CSA]). Similarly, puberty further worsened the inverse association between HIV and bone strength (SSI) in both males (interaction p=0.008) and females (interaction p=0.004). Despite long-term ART, we identified deficits in predicted bone strength in those living with HIV, which were more overt in the later stages of puberty. This is concerning as this may translate to higher fracture risk later in life.

Keywords: ANALYSIS/QUANTIFICATION OF BONE, DISEASES AND DISORDERS OF/RELATED TO BONE, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Introduction

Improved access and earlier antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation in children with HIV (CWH) has markedly increased survival, enabling many children to now reach puberty and adulthood (1). The global decline in HIV-associated child and adult deaths has largely been achieved in Eastern and Southern Africa, home to 89.2% (2.5 million out of 2.8 million) of the world’s CWH (2). There is increasing recognition that, despite ART, HIV has adverse effects on multiple organ systems in children resulting in long-term multisystem comorbidities. These are of growing concern as the improved survival due to ART means that increasing numbers of CWH are now entering adolescence and adulthood (3). In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), CWH are commonly underweight (weight-for-age Z-score <−2) and/or stunted (height-for-age Z-score <−2), with the prevalence of stunting varying from 23% to 73% (3–5). Linear growth continues through adolescence as bone accrues to achieve peak bone mass (PBM) (6). PBM is a critical determinant of adult osteoporotic fracture risk (7); a 10% reduction can double fracture risk in adulthood (although this has not yet been studied in African populations) (8,9). The long-term impact of exposure to both HIV infection and ART in perinatally-infected children is of concern as impaired linear growth may be associated with sub-optimal PBM accrual, with implications for adult fracture risk (10).

We recently reported lower dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measured bone outcomes of total-body less-head (TBLH) bone mineral content (BMC) for lean mass adjusted for height (TBLH-BMCLBM) and lumbar spine bone mineral apparent density (LS-BMAD) in CWH than in children without HIV (CWOH), which was more overt in later adolescence (11). Tenofovir disproxil fumarate (TDF) exposure has been associated with low BMD in adults living with HIV (12,13). Recently, among CWH, both TDF exposure and orphanhood were associated with lower TBLH-BMCLBM Z-score (11).

In a smaller cross-sectional study in Zimbabwe, age at ART initiation was strongly negatively correlated with both LS-BMAD and TBLH-BMC LBM Z-scores, with a 0.13 SD reduction in LS-BMAD seen for each year that ART initiation was delayed (14). However, both these studies used DXA, which cannot differentiate trabecular from cortical bone (15,16). Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) offers an opportunity to study bone architecture, quantifying volumetric BMD, and bone size which enables prediction of bone strength (17,18). A recent South African study compared pQCT measured bone architecture between 172 CWH and 98 CWOH aged 7 to 14 years, reporting lower trabecular vBMD in male CWH, and generally lower bone strength in CWH than in CWOH (19).

We hypothesized that HIV infection would be associated with adverse effects on bone architecture leading to compromised pQCT bone outcomes i.e vBMD, bone size and predicted strength (see supplementary Fig. 1). We therefore sought to compare the bone density, bone size and predicted bone strength parameters of trabecular and cortical bone in peripubertal males and females living with and without HIV in Harare, Zimbabwe. We investigated whether any association of HIV with pQCT measured bone outcomes differed by pubertal stage by testing for interaction. Furthermore, among CWH, we determined the association between TDF exposure and bone outcomes.

Methods

Study setting:

A cross-sectional study was conducted using baseline pQCT measurements from the IMpact of Vertical HIV infection on child and Adolescent Skeletal development (IMVASK) study, as per published protocol (ISRCTN12266984) (11,20). CWH, established on ART for at least two years, were quota sampled stratified by sex- and age- strata (8–10, 11–13 and 14–16 years) from HIV clinics at Parirenyatwa and/or Sally Mugabe Hospitals in Harare, Zimbabwe. These are the two large public hospitals in Harare, providing HIV care services to over 2,000 children. CWOH were randomly recruited, using school registers, from three primary and three secondary schools within the same community suburbs served by the hospitals providing HIV care, and were frequency-matched by sex and age strata. Inclusion criteria were: age 8 to 16 years, living in Harare. CWH were included if they were aware of their HIV status and had been taking ART for at least 2 years. At the time of enrolment into the study, CWOH underwent HIV testing to confirm their status. Children with acute illness requiring hospitalization, those lacking guardian consent and those who were recently diagnosed with HIV were excluded from this study.

Study Procedures:

Data were collected between May 2018 and Jan 2020. Demographic and clinical data were collected using an interviewer administered questionnaire together with hand held medical records. Demographic and clinical data collected included age, sex, socio-economic status, guardianship, orphanhood, age at HIV diagnosis, age at ART initiation, ART regimen, diet and physical activity. SES was derived using the first component from a principal component analysis (21) combining details including number in household, head of household age, highest maternal and paternal education levels, household ownership, monthly household income, access to electricity, water, a flush toilet and/or pit latrine and ownership of a fridge, bicycle, car, television, and/or radio and was split into tertiles for analysis. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short version (22), classified intensity of physical activity as: low (MET [metabolic rate] minutes <600 per week), moderate (MET minutes =600 to 3000 per week) and vigorous (MET minutes >3000 per week). Diet was assessed using a tool developed for the Zimbabwean context based on a validated dietary diversity and food frequency tool from India and Malawi and international guidelines applicable to SSA (23,24). Daily dietary calcium (Ca) intake was classified as very low (<150mg/day), low (150–299mg/day) and moderate (300–450mg/day). Daily dietary vitamin D intake was classified as very low (<4.0mcg/day), low (4.0–5.9mcg/day) and moderate (6.0–8.0mcg/day).

Puberty was Tanner staged by a trained study nurse and/or doctor. For males, testicular volume, penile size (length and circumference) and pubic hair growth (quality, distribution and length) were assessed. For females, breast growth (size and contour) as well as pubic hair growth and age of menarche were assessed. Testicular, breast and penile growth were graded from I-V based on Tanner descriptions (25–27). Where there was a discordance between the stages for males and females, testicular and breast development stage respectively were used to assign Tanner Stage. Participants were grouped into Tanner stages 1 and 2 (pre- to early puberty) and Tanner stages 3 to 5 (mid/late puberty). Three standing height measurements were obtained to the nearest 0.1cm using a Seca 213 stadiometer (Hamburg, Germany), and three weight measurements were obtained to the nearest 0.1kg with a Seca 875 weight scale (Hamburg, Germany), with means calculated. Equipment was calibrated annually. Using British 1990 growth references, height-for-age Z-score <−2, weight-for-age Z-score <−2 and low weight-for-height BMI Z-score <−2 were used to define stunting, underweight and wasting respectively (28,29). Fat mass and fat-free soft tissue (lean) mass were measured by whole body DXA scan, using a Hologic QDR Wi machine with Apex software version 4.5 (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA, USA). CD4 cell count was measured using a PIMA CD4 machine (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). HIV viral load was measured using the GeneXpert HIV-1 viral load platform (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA).

pQCT scan acquisition:

Non-dominant tibial pQCT scans were performed using an XCT 2000™ (Stratec Medizintecknik, Pforzheim, Germany), with voxel size 0.5 × 0.5 mm and slice thickness 2 mm (CT scan speed 30 mm/s; scout view scan speed 40 mm/s). Tibial length was measured from the distal medial malleolus to the tibial plateau with a metal ruler. Scan sites were determined as a percentage of tibia length, with the exact position determined by scout view placement of a reference line on the growth plate, or on the end plate for those with fused growth plates (30). As long bones grow in length, the growth plate moves upward and the wider metaphysis is reshaped into a diaphysis by continuous resorption by osteoclasts beneath the periosteum (31). To allow for consistency of a scan site the reference line was placed at the growth plate in those children whose end plate and growth plate were not yet fused. vBMD was measured in mg/cm3 at the 4% (metaphyseal) site for trabecular bone and the 38% (diaphyseal) site for cortical bone. Bone size measures included 4% and 38% total cross-sectional area [CSA, mm2] and 38% cortical thickness (mm). Predicted bone strength was measured as 38% stress strain index [SSI, mm3] indicating the bending and torsional strength of bone (32). The manufacturer’s software (version 6.20) was used for image processing and analysis. At the 4% tibia CALCBD was used to calculate total CSA and trabecular vBMD. CALCBD contour mode 1 (i.e. threshold algorithm) was used to exclude pixels in defined regions of interest (ROI) that fell below a threshold of 180 mg/cm3, peel mode 1 (i.e. concentric peel) peeled away the outer 55% of the total bone CSA leaving an inner 45% CSA considered as the trabecular region of interest. At the 38% tibial site CORTBD was used to define cortical vBMD and area, this algorithm removes all voxels within ROIs with an attenuation coefficient below a 710 mg/cm3 threshold (with separation mode 1). Total CSA was defined at the 38% tibia using a 180 mg/cm3 threshold. Cortical thickness was calculated using a circular ring model. A phantom was scanned daily for quality assurance. Thirty participants were scanned twice, with repositioning, to assess reproducibility. Coefficients of variation were calculated from the results of the 30 re-scanned participants. The short-term precision (Root Mean Square % CV) was 1.26% for trabecular vBMD, 0.37% for cortical vBMD, 2.08% for 4% total CSA and 0.93% for 38% CSA. All pQCT scan slices and scout views were qualitatively graded by a single radiographer. Movement artefacts were graded 0 to 3: (0) none, (1) slight, (2) medium streaking and (3) scan unusable. Grade 3 images were excluded from analysis.

Ethical considerations

Trained research assistants and/or a study nurse explained the study information to participants and guardians. Guardians gave written informed consent and participants gave age-appropriate written assent. This study was approved by the Parirenyatwa Hospital and College of Health Sciences joint research ethics committee (JREC/123/19), the Biomedical Research and Training Institute Institutional Review Board (AP150/2019), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (17154) Ethics Committee and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A2494).

Statistical analysis:

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16.0 (Stata Corporation Inc., College Station, TX, USA). Data were cleaned and checked for consistency and outliers. Outcomes included 4% trabecular and 38% cortical vBMD (mg/cm3), 4% and 38% CSA (mm2), 38% cortical thickness (mm) and 38% stress-strain index (SSI) (mm4). We used independent sample t-tests to compare continuous data between groups and percentages and chi-squared tests for categorical data. We determined differences between CWH and children without HIV, stratified by sex (given different bone accrual rates) in separate regression models, by comparing means using linear regression and generating mean differences and 95% confidence intervals. We compared an unadjusted model with a model adjusting for a priori confounders; age (years), height (cm), binary pubertal status (pre/early Tanner 1–2 vs. mid/late Tanner 3–5, to maximize statistical power) (33), fat mass (34), physical activity (35), SES (36) and orphanhood (11) (see Supplementary figure 1). As lean mass was co-linear with height (correlation coefficient = 0.90, p value= <0.001), lean mass adjustment was not made to avoid collinearity. If lean mass was included in linear regression, the variance inflation factors exceeded a value of 8. We assessed modification of the association of HIV with bone outcomes by pubertal stage, by incorporating a binary interaction term for puberty (pre/early vs. mid/late). In further analyses, restricted to CWH, we compared those who were exposed to TDF with those who were not. To account for missing data assumed missing at random, multiple imputation by chained equations (with 7 imputed datasets), allowing for imputation of categorical and continuous data simultaneously was performed (37). Imputation models included all pQCT bone outcomes, variables associated with missingness (Tanner stage only), and factors determined in complete case analysis to be associated with HIV (fat mass, SES, orphanhood, physical activity and sex). Imputation models were run on males and females combined, with regression analysis models using the imputed data run stratified by sex.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

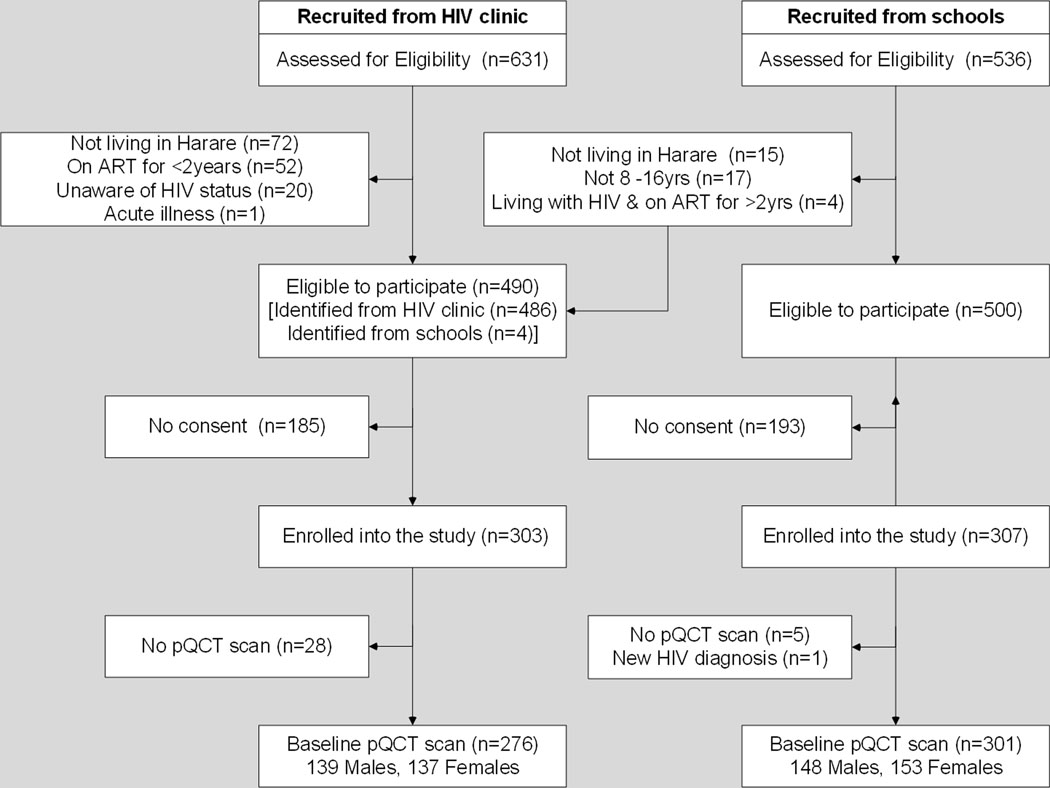

The study recruited 610 participants, of whom 578 (94.8%) (276 with and 302 without HIV) had a pQCT scan (Figure 1). One school participant was excluded as they were newly diagnosed with HIV. Participants who did not have a pQCT scan were similar to those with a pQCT scan in terms of sex, pubertal status, SES, calcium and vitamin D intake, but children without a pQCT scan were more likely to be living with HIV and to report lower levels of physical activity compared to those who had a scan (Supplementary table 1).

Figure 1: Flow diagram to show participants included in the pQCT study.

- Figure 1 above shows participants enrolled and included in the study data analysis. All enrolled children were included in the final analysis, unless withdrawn from the study. Missing data was estimated by multiple imputation.

pQCT; Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography

Of the participants with a pQCT scan, CWH were similar in age to those without HIV. However, CWH were more likely to be in Tanner stages 1 and 2 compared with their uninfected counterparts; this was the case for both males (67.6% vs. 52.3%; p=0.009) and females (55.2% vs. 39.0%; p=0.005) (Table 1). Height increased with Tanner stage, in both CWH and CWOH (Supplementary Table 2). Compared with children without HIV, CWH were mean 8.0cm (males) and 6.9cm (females) shorter, and 3.7kgs (males) and 6.9kgs (females) lighter (p<0.001 for all), with corresponding lower fat and lean mass.

Table 1:

Demographic and anthropometric characteristics, by HIV status, in male and female children and adolescents

| Males (n=303) | Females (n=306) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Clinical Characteristics | n | CWH (n=152) | CWOH (n=151) | p value | n | CWH (n=151) | CWOH-(n=155) | p value | |

|

| |||||||||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 303 | 12.5 (2.5) | 12.4 (2.5) | 0.773 | 306 | 12.4 (2.6) | 12.6 (2.5) | 0.518 |

|

| |||||||||

| Age Group (years) | 8–10 years | 303 | 52 (34.2) | 50 (33.1) | 0.920 | 306 | 50 (33.1) | 48 (31.0) | 0.890 |

| 11–13 years | 52 (34.2) | 50 (33.1) | 50 (33.1) | 51 (32.9) | |||||

| 14–16 years | 48 (31.6) | 51 (33.8) | 51 (33.8) | 56 (36.1) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Tanner Stage (%) | Tanner 1 | 292 | 57 (40.1) | 45 (30.0) | 0.026 | 299 | 60 (41.4) | 25 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Tanner 2 | 39 (27.5) | 34 (22.7) | 20 (13.8) | 35 (22.7) | |||||

| Tanner 3 | 22 (15.5) | 24 (16.0) | 33 (22.8) | 29 (18.8) | |||||

| Tanner 4 | 19 (13.4) | 43 (28.7) | 25 (17.2) | 49 (31.8) | |||||

| Tanner 5 | 5 (3.5) | 4 (2.7) | 7 (4.8) | 16 (10.4) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Socio-Economic Status (%) | Low, Tertile 1 | 303 | 54 (35.5) | 38 (25.2) | 0.121 | 306 | 61 (40.4) | 50 (32.3) | 0.014 |

| Middle, Tertile 2 | 51 (33.6) | 54 (35.8) | 54 (35.8) | 44 (28.4) | |||||

| High, Tertile 3 | 47 (30.9) | 59 (39.1) | 36 (23.8) | 61 (39.4) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Orphan Status (%) | Not an orphan | 294 | 84 (58.3) | 139 (92.7) | <0.001 | 299 | 83 (56.8) | 144 (94.1) | <0.001 |

| One parent alive | 53 (36.8) | 7 (4.7) | 52 (35.6) | 7 (4.6) | |||||

| Orphan | 7 (4.9) | 4 (2.7) | 11 (7.5) | 2 (1.3) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Physical Activity in METS (%) | Low, <600 | 303 | 71 (46.7) | 51 (33.8) | 0.048 | 306 | 77 (51.0) | 63 (40.6) | 0.028 |

| Moderate, 600–3000 | 35 (23.0) | 50 (33.1) | 42 (27.8) | 38 (24.5) | |||||

| High, >3000 | 46 (30.3) | 50 (33.1) | 32 (21.2) | 54 (34.8) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Calcium Intake (mg) (%) | <150 mg | 303 | 67 (44.1) | 69 (45.7) | 0.848 | 306 | 68 (45.0) | 67 (43.2) | 0.951 |

| 150–299 mg | 30 (19.7) | 32 (21.2) | 32 (21.2) | 34 (21.9) | |||||

| 300–449 mg | 55 (36.2) | 50 (33.1) | 51 (33.8) | 54 (34.8) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Vitamin D Intake, mcg (%) | <4.0 mcg | 303 | 24 (15.8) | 18 (11.9) | 0.535 | 306 | 16 (10.6) | 19 (12.3) | 0.422 |

| 4.0 – 5.99 mcg | 99 (65.1) | 99 (65.6) | 106 (70.2) | 98 (63.2) | |||||

| 6.0 – 7.9 mcg | 29 (19.1) | 34 (22.5) | 29 (19.2) | 38 (24.5) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Anthropometry | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Height, cm | Mean (SD) | 301 | 139.7 (12.6) | 147.7 (15.1) | <0.001 | 306 | 140.4 (13.1) | 147.3 (11.8) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Height for age Z-score | Mean (SD) | 301 | −1.8 (1.2) | −0.6 (1.0) | <0.001 | 306 | −1.5 (1.1) | −0.5 (1.1) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Stunting (%) | HAZ<–2, % | 301 | 55 (36.7) | 10 (6.6) | <0.001 | 306 | 40 (26.5) | 12 (7.7) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Weight, kgs | Mean (SD) | 303 | 35.5 (17.5) | 39.2 (14.5) | 0.053 | 306 | 36.1 (13.5) | 43.0 (15.8) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Weight for age Z-score, mm | Mean (SD) | 303 | −1.2 (1.2) | −0.7 (1.0) | <0.001 | 306 | −1.3 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.1) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Underweight (%) | WAZ<−2, % | 303 | 50 (32.9) | 15 (10.0) | <0.001 | 306 | 30 (19.9) | 8 (5.2) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Body Mass Index, kg/cm2 | Mean (SD) | 303 | 16.5 (1.5) | 17.2 (2.2) | 0.004 | 306 | 17.4 (2.7) | 18.9 (3.6) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| BMI for age Z-score | Mean (SD) | 303 | −0.8 (0.9) | −0.5 (1.0) | 0.007 | 306 | −1.5 (1.1) | −0.5 (1.1) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Wasting (%) | BAZ<−2, % | 303 | 11 (7.3) | 16 (10.7) | 0.313 | 306 | 5 (3.2) | 12 (8.0) | 0.071 |

|

| |||||||||

| Fat Mass, Kgs | Mean (SD) | 288 | 6.8 (1.8) | 8.3 (3.1) | <0.001 | 287 | 9.5 (4.3) | 13.3 (6.1) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Lean Mass, Kgs | Mean (SD) | 288 | 26.2 (6.7) | 30.1 (9.3) | <0.001 | 287 | 26.0 (6.9) | 29.2 (7.3) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| HIV Characteristics | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Time since HIV diagnosis, years | Mean (SD) | 152 | 8.7 (2.7) | 151 | 8.6 (2.5) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age at HIV diagnosis, years | Mean (SD) | 152 | 3.8 (3.1) | 151 | 3.9 (3.3) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Duration on ART, years | Mean (SD) | 152 | 8.0 (2.7) | 151 | 7.8 (2.5) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age at ART initiation, years | Mean (SD) | 152 | 4.5 (3.1) | 151 | 4.7 (3.4) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age at TDF initiation, years | Mean (SD) | 152 | 10.1 (3.8) | 151 | 10.6 (3.2) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Current use of TDF | Yes | 152 | 28 (18.4) | 151 | 35 (23.2) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Ever used TDF | Yes | 152 | 50 (32.9) | 151 | 52 (34.4) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Years of exposure to TDF | None | 152 | 102 (67.1) | 151 | 99 (65.6) | ||||

| <4 years | 30 (19.7) | 32 (21.2) | |||||||

| >4 years | 20 (13.2) | 20 (13.2) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Viral Load in copies/ml (%) | <1000 | 135 | 106 (78.5) | 133 | 106 (79.7) | ||||

| ≥1,000 | 29 (21.5) | 27 (20.35) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CD4 Count in cells/μl(%) | <200 | 148 | 4 (2.7) | 140 | 4 (2.9) | ||||

| 200–499 | 30 (20.3) | 20 (14.3) | |||||||

| ≥500 | 114 (77.0) | 116 (82.9) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| pQCT bone outcomes | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Trabecular Density, mg/cm3 | Mean (SD) | 287 | 197.5 (40.0) | 210.1 (40.9) | 0.009 | 290 | 202.0 (33.7) | 213.8 (34.1) | 0.003 |

|

| |||||||||

| Cortical Density, mg/cm3 | Mean (SD) | 287 | 1068.6 (39.2) | 1070.8 (34.0) | 0.616 | 290 | 1099.6 (38.7) | 1094.9 (46.6) | 0.354 |

|

| |||||||||

| 4% Total Cross Sectional Area, mm2 | Mean (SD) | 287 | 670.1 (186.6) | 772.6 (239.2) | <0.001 | 290 | 667.3 (174.5) | 721.1 (193.6) | 0.014 |

|

| |||||||||

| 38% Total Cross Sectional Area, mm2 | Mean (SD) | 287 | 317.6 (70.1) | 367.6 (83.6) | <0.001 | 290 | 302.3 (59.2) | 348.4 (66.1) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Cortical Thickness, mm | Mean (SD) | 287 | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.6) | 0.066 | 290 | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.807 |

|

| |||||||||

| Stress Strain Index, mm3 | Mean (SD) | 287 | 979.8 (316.8) | 1181.5 (394.1) | <0.001 | 290 | 922.8 (275.4) | 1093.4 (325.9) | <0.001 |

p values for categorical variables were calculated using the chi squared test, p values for continuous variables were calculated using the t test for 2 independent samples, SES; socioeconomic status, BMI; Body mass index, TB; Total body TDF; Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate, CWH; children living with HIV, CWOH; children living without HIV

NB: Data presented are unadjusted

Overall CWH had been diagnosed with HIV when aged 3.9±3.2 (mean ± SD) years, and started on ART at a median age of 3.7 (IQR 1.8–6.9) years, so that at the time of participation in this study, median ART duration was 8.1 (IQR 6.2–9.5) years. The majority (79%) had a suppressed viral load (<1000 copies/ml), and only 2.3% had a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3. Among CWH 21% (n=63/303) were taking TDF at the time of the study. However, 33.6% (n=102) reported ever using TDF as part of their ART regimen, of whom 13.2% (n=40) reported taking it for more than 4 years. The average age at TDF initiation was 10 years.

CWH were more likely to have a lower SES than children without HIV. Compared with children without HIV, both male and female CWH were more likely to be orphans or to have only one surviving parent (Table 1). In both sexes, physical activity levels were lower in CWH compared to those without HIV. In both males and females, dietary calcium and vitamin D intakes were similar in those with and without HIV, with the majority having a low or very low calcium intake (Table 1).

pQCT measured bone outcomes, stratified by sex

Bone density:

In unadjusted analyses, trabecular vBMD was 12.6 mg/cm3 (6.2%) and 11.7 mg/cm3 (5.2%) lower in male and female CWH than in children without HIV, whilst no such differences were seen for cortical vBMD (Table 2). However, adjustment for a priori confounders completely attenuated these vBMD differences. Each of the variables included in the models had a small incremental effect on the association between HIV and each of the pQCT bone outcomes. However, adjusting for height attenuated more of the effect of HIV on trabecular and cortical density than the other covariates.

Table 2:

Differences in pQCT measured tibial bone outcomes in children living with and without HIV before and after adjustment

| Males | Unadjusted model (n=303) | Adjusted model (n=303) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone density | MD (95% CI) | p value | MD (95% CI) | p value |

| 4% Trabecular Density, mg/cm3 | −12.6 (−22.1, −3.1) | 0.010 | −7.5 (−18.5, 3.5) | 0.179 |

| 38% Cortical Density, mg/cm3 | −2.3 (−11.2, 6.5) | 0.604 | −1.4 (−11.8, 9.1) | 0.796 |

| Bone Size | ||||

| 4% Total CSA, mm2 | −93.4 (−144.7, −42.2) | <0.001 | −22.1 (−54.8, 10.6) | 0.184 |

| 38% Total CSA, mm2 | −35.6 (−66.0, −5.3) | 0.021 | 0.4 (−24.9, 25.7) | 0.975 |

| 38% Cortical Thickness, mm | −0.1 (−0.3, 0) | 0.063 | 0 (−0.1, 0.1) | 0.973 |

| Bone Strength | ||||

| 38% Stress Strain Index, mm3 | −189.1 (−270.1, −108.1) | <0.001 | −40.2 (−95.1, 14.6) | 0.150 |

| Females | Unadjusted model (n=306) | Adjusted model (n=306) | ||

| Bone density | MD (95% CI) | p value | MD (95% CI) | p value |

| 4% Trabecular Density, mg/cm3 | −11.7 (−19.9, −3.6) | 0.005 | −7.3 (−17.7, 3.07) | 0.167 |

| 38% Cortical Density, mg/cm3 | 4.1 (−6.3, 14.4) | 0.441 | 8.8 (−0.6, 18.1) | 0.068 |

| Bone Size | ||||

| 4% Total CSA, mm2 | −50.7 (−92.8, −8.6) | 0.019 | 17.1 (−18.0, 52.2) | 0.338 |

| 38% Total CSA, mm2 | −41.1 (−55.2, −27.0) | <0.001 | −6.2 (−18.7, 6.4) | 0.336 |

| 38% Cortical Thickness, mm | 0 (−0.2, 0.1) | 0.817 | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | <0.001 |

| Bone Strength | ||||

| 38% Stress Strain Index, mm3 | −156.0 (−226.0, −86.0) | <0.001 | 16.6 (−37.4, 70.6) | 0.546 |

Adjusted for age (years), height (cm), pubertal status, fat mass, physical activity, socioeconomic status and orphanhood

MD (95% CI); Mean Difference (95 % Confidence Interval) with children without HIV as the reference group, such that negative values mean that those with HIV have lower values than those with HIV.

All pQCT variables, Tanner stage and orphanhood were estimated by multiple imputation

Bone size:

CWH (both males and females), had smaller metaphyseal and diaphyseal tibial bone size (CSA) than CWOH (Table 2). These size differences were largely explained by adjustment. Differences in cortical thickness were only evident between females with and without HIV after accounting for age, height and puberty, after which females with HIV appeared to have thicker cortices than females without HIV.

Bone strength:

In both males and females, before any adjustment, SSI was lower in CWH than those without HIV; however, this was explained by adjustment for age, height, and puberty (Table 2).

pQCT measured bone outcomes, stratified by sex and puberty

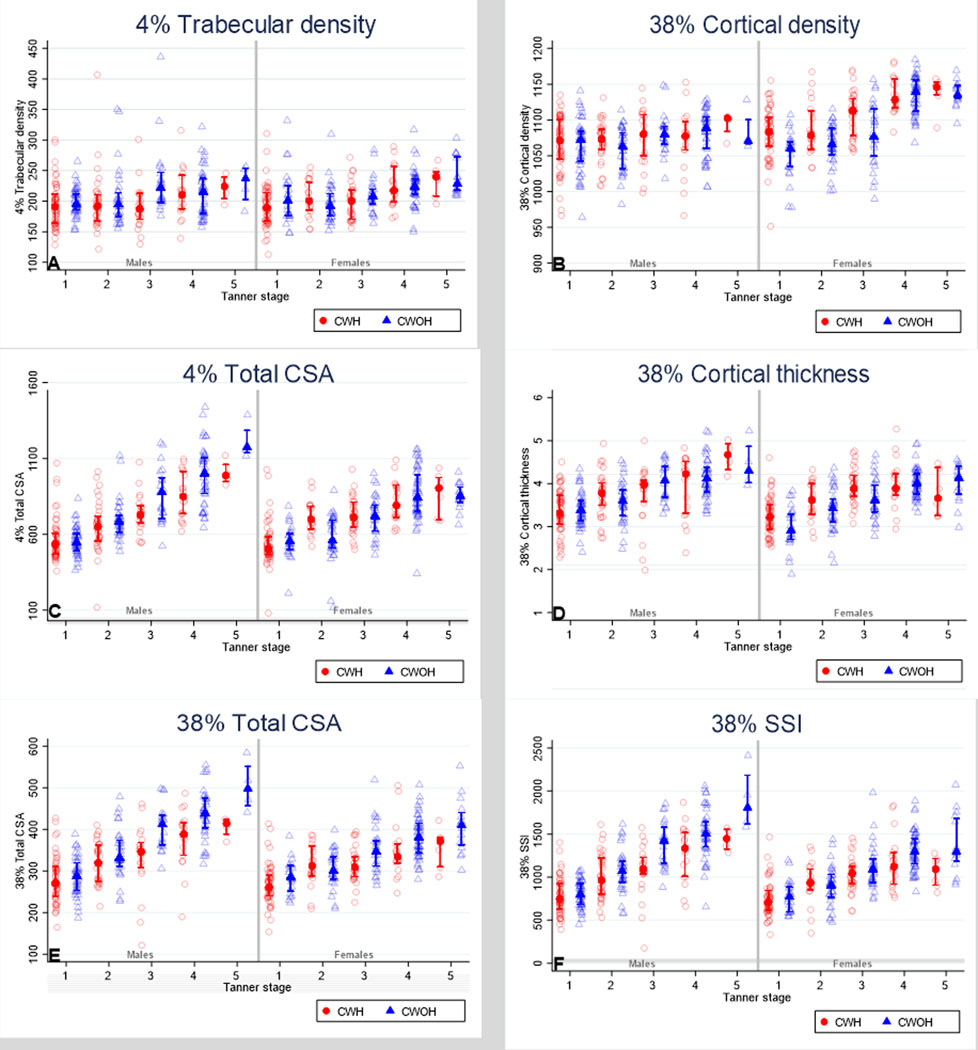

We next investigated the potential interaction between HIV infection and pubertal stage (pre/early [Tanner 1–2] vs. mid/late [Tanner 3–5]) on bone outcomes.

Bone density:

Differences in trabecular vBMD between children with and without HIV were similarly small, in both pre/early and mid/later puberty, with no evidence of interaction for males or females (Figure 2 and Table 3). However, amongst girls, both before and after adjustment, evidence was detected for an interaction between HIV and pubertal stage, such that in the pre/early stages of puberty females with HIV had greater cortical vBMD than females without HIV, whereas no such difference was detected in the mid/later stages of puberty (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Figure 2: Unadjusted comparison of pQCT measured bone outcomes between children living with and without HIV infection by sex and pubertal status.

- The marker is representing median and the bars are representing interquartile range

NB: Data presented in this figure are unadjusted

Table 3:

Differences in pQCT measured bone outcomes in children by HIV and pubertal status

| Males | Unadjusted model (n=303) | Adjusted model (n=303) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanner Stages 1 and 2 | Tanner Stages 3, 4 and 5 | p value | Tanner Stages 1 and 2 | Tanner Stages 3, 4 and 5 | p value | |

| Bone Density | MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | ||

| 4% Trabecular Density, mg/cm3 | −6.1 (−17.4, 5.1) | −17.8 (−33.2, −2.4) | 0.225 | −3.0 (−16.7, 10.6) | −15.6 (−34.5, 3.4) | 0.194 |

| 38% Cortical Density, mg/cm3 | 4.4 (−6.8, 15.5) | −7.5 (−21.8, 6.7) | 0.192 | 2.2 (−10.6, 14.9) | −7.7 (−24.5, 9.2) | 0.298 |

| Bone SIze | ||||||

| 4% Total Cross Sectional Area, mm2 | −2.2 (−46.8, 42.4) | −141.5 (−214.6, −67.4) | 0.002 | 1.9 (−42.2, 46.0) | −65.1 (−126.4, −3.7) | 0.035 |

| 38% Total Cross Sectional Area, mm2 | 7.4 (−33.9, 48.7) | −74.1 (−99.3, −48.9) | 0.001 | 19.9 (−37.0, 76.9) | −34.5 (−76.7, 7.7) | 0.016 |

| 38% Cortical Thickness, mm | 0 (−0.1, 0.2) | −0.2 (−0.5, 0) | 0.119 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.2) | 0.369 |

| Bone Strength | ||||||

| 38% Stress Strain Index, mm3 | −23.5 (−98.9, 51.9) | −294.6 (−411.4, −177.7) | <0.001 | 14.3 (−50.2, 78.7) | −137.5 (−243.1, −32.1) | 0.008 |

| Females | Unadjusted model (n=306) | Adjusted model (n=306) | ||||

| Tanner Stages 1 and 2 | Tanner Stages 3, 4 and 5 | p value | Tanner Stages 1 and 2 | Tanner Stages 3, 4 and 5 | p value | |

| Bone Density | MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | ||

| 4% Trabecular Density, mg/cm3 | −5.8 (−18.0, 6.5) | −11.6 (−22.1, −1.1) | 0.481 | −8.0 (−22.5, 6.6) | −6.7 (−19.3, 5.9) | 0.881 |

| 38% Cortical Density, mg/cm3 | 23.4 (11.5, 35.3) | 0.1 (−12.1, 12.2) | 0.007 | 19.0 (5.1, 32.9) | −1.2 (−15.0, 12.6) | 0.016 |

| Bone Size | ||||||

| 4% Total Cross Sectional Area, mm2 | 16.2 (−34.6, 67.0) | −49.3 (−100.1, 1.6) | 0.087 | 45.6 (−1.5, 92.7) | −10.5 (−57.4, 36.5) | 0.073 |

| 38% Total Cross Sectional Area, mm2 | −17.9 (−34.8, −1.2) | −43.4 (−61.3, −25.7) | 0.040 | 5.1 (−11.3, 21.6) | −17.1 (−33.7, −0.5) | 0.029 |

| 38% Cortical Thickness, mm | 0.16 (0, 0.4) | 0.01 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.278 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.2 (0, 0.4) | 0.362 |

| Bone Strength | ||||||

| 38% Stress Strain Index, mm3 | −30.4 (−109.4, 48.6) | −170.6 (−253.6, −87.6) | 0.016 | 81.2 (11.3, 150.9) | −46.1 (−119.3, 27.1) | 0.004 |

Adjusted for age (years), height (cm), fat mass, physical activity, socioeconomic status and orphanhood

MD (95% CI); Mean Difference (95 % Confidence Interval) with children without HIV as the reference group, such that negative values mean that those with HIV have lower values than those without HIV. HIV*puberty (binary) p values for interaction are shown

All pQCT variables, Tanner stage and orphanhood were estimated by multiple imputation

Bone size:

Before adjustment clear evidence was detected to suggest that pubertal stage was modifying the effect of HIV on bone size, such that in both males and females, CWH in mid/late puberty had substantially smaller CSA than children without HIV, at the metaphysis and diaphysis, whereas this difference was not apparent in pre/early puberty (Figure 2 and Table 3). Whilst adjustment accounted for some of these differences, evidence for interactions remained for all, other than for metaphyseal bone size in females (Table 3). No evidence was detected to suggest that puberty modifies the effect of HIV on cortical thickness.

Bone Strength:

In pre/early puberty, female CWH appeared to have higher bone strength than CWOH, whereas the reduced bone strength (SSI) seen in CWH, compared to those without HIV, was most overt in mid/late puberty, in both males and females (Figure 2 and Table 3). After full adjustment, strong evidence persisted to indicate that puberty was modifying the effect of HIV on bone strength in both males (interaction p=0.008) and females (interaction p=0.004), such that HIV-associated bone deficits appear worse towards the end of puberty (Tables 3).

pQCT bone outcomes in children with HIV, stratified by sex and exposure to TDF

In further analyses, restricted to CWH, those who were and were not exposed to TDF were similar in terms of sex, SES, physical activity and dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D (Supplementary table 3). However, those who were using TDF were older, taller, heavier and were more likely to be in the later stages of puberty compared with CWH who were not using TDF. After adjustment, using TDF was associated with lower trabecular vBMD in males (Table 4). No other skeletal deficits were evident between TDF exposed vs. non-exposed groups once analyses were adjusted.

Table 4:

Differences in pQCT measured bone outcomes in children living with HIV by exposure to Tenofovir

| Males | Unadjusted (n=151) | Adjusted (n=151) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Density | MD (95% CI) | p value | MD (95% CI) | p value |

| 4% Trabecular Density, mg/cm3 | −12.9 (−27.7, 1.9) | 0.088 | −18.8 (−35.8, −1.8) | 0.030 |

| 38% Cortical Density, mg/cm3 | 14.5 (−0.6, 29.6) | 0.060 | 10.1 (−8.0, 28.2) | 0.269 |

| Bone Size | ||||

| 4% Total CSA, mm2 | 109.6 (36.8, 182.5) | 0.004 | −2.4 (−70.6, 65.8) | 0.945 |

| 38% Total CSA, mm2 | 85.8 (−31.6, 203.2) | 0.151 | 64.9 (−77.4, 207.1) | 0.369 |

| 38% Cortical Thickness, mm | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.4) | 0.352 | −0.14 (−0.4, 0.1) | 0.323 |

| Bone Strength | ||||

| 38% Stress Strain Index, mm3 | 122.3 (−10.0, 254.5) | 0.070 | −50.5 (−184.4, 83.4) | 0.454 |

| Females | Unadjusted (n=152) | Adjusted (n=152) | ||

| Bone Density | MD (95% CI) | p value | MD (95% CI) | p value |

| 4% Trabecular Density, mg/cm3 | 9.1 (−6.7, 24.9) | 0.253 | −5.4 (−23.7, 12.9) | 0.557 |

| 38% Cortical Density, mg/cm3 | 14.7 (−1.1, 30.4) | 0.067 | −11.5 (−28.3, 5.3) | 0.177 |

| Bone Size | ||||

| 4% Total CSA, mm2 | 175.1 (112.8, 237.4) | <0.001 | 45.1 (−24.9, 115.0) | 0.204 |

| 38% Total CSA, mm2 | 47.2 (24.0, 70.4) | <0.001 | 5.6 (−20.4, 31.6) | 0.668 |

| 38% Cortical Thickness, mm | 0.2 (0.0, 0.5) | 0.049 | −0.1 (−0.4, 0.2) | 0.423 |

| Bone Strength | ||||

| 38% Stress Strain Index, mm3 | 226.6 (119.3, 333.9) | <0.001 | 27.1 (−86.5, 140.6) | 0.635 |

Adjusted for age (years), height (cm), pubertal status, fat mass, physical activity, socioeconomic status and orphanhood

MD (95% CI); Mean Difference (95 % Confidence Interval) with those who are not using TDF as the reference group, such that negative values mean that those using TDF have lower values than those who are not using TDF

All pQCT variables, Tanner stage and orphanhood were estimated by multiple imputation

Discussion

We report results from the largest study to date to use pQCT in a sample of children and adolescents growing up with HIV infection in SSA. In Zimbabwe, we have shown that CWH have deficits in both bone size and strength, compared with children who do not have HIV. These deficits included a 6% lower diaphyseal bone size in female CWH in the latter stages of puberty, even after accounting for body size and other confounders. Cortical thickness was greater in male CWH who are in the pre/early pubertal stage than in male CWOH. In females, cortical thickness was greater in CWH than in CWOH, regardless of pubertal status. Greater cortical thickness may contribute to the greater estimated bone strength reported in this study. In pre/early puberty, female CWH appear to have higher bone strength than CWOH. It is unclear whether this is due to the higher cortical density they showed at this pubertal stage. Despite CWH being shorter and lighter than CWOH, these results could be suggesting that CWH who are in pre/early puberty have adequate bone strength for their smaller stature. However, when they grow in height, the residual smaller bone size leads to reduced predicted bone strength so that a strength deficit begins to emerge in mid/late puberty. Although adjusted differences were less marked in females, reduced bone strength was still apparent in male CWH in the latter stages of puberty. These findings are of concern: adolescent pubertal growth is a crucial period for skeletal development, deficits in bone strength that manifest during later puberty are likely to persist into adulthood with implications for adult fracture risk.

To date, only two studies have reported using pQCT in children living with HIV (19,38). Our results are consistent with findings from a smaller cross-sectional pQCT study in South Africa of younger children (7 to 14 years), which suggested CWH have smaller bone size and lower predicted bone strength than CWOH, although this association was not adjusted for fat mass, physical activity or any indicator of SES. Our larger study was able to both stratify by pubertal stage and adjust for a number of relevant confounders and showed how differences in size and strength becomes more pronounced in later puberty. A longitudinal Canadian study of 9 to 18 year old CWH with diverse ethnic backgrounds, reported no change in pQCT bone outcomes over 2 years (38). However, this study was small (n=31 CWH) across sex and ethnic strata, suggesting insufficient power to detect change over time. Although notably, as seen in our study, Canadian CWH in early puberty had higher cortical BMD compared to CWOH (38). An extensive literature has established a higher prevalence of stunting and underweight in CWH than in CWOH (4,5,39–42), which has been confirmed by our study and our earlier studies in Zimbabwean children (5,14). By adjusting for body size however, we have shown that the lower bone size in female CWH, especially in later puberty, is independent of lower height and weight.

This is the first study to use pQCT to examine the effects of TDF use on bone architecture in CWH. Our previous DXA findings in the same Zimbabwean cohort identified a strong association between TDF use and bone deficits, particularly affecting TBLH-BMCLBM, such that children exposed to TDF for four or more years had on average a 0.5 SD lower TBLH-BMCLBM Z-Score compared with CWH who had not received TDF (11). This effect size is clinically important, as a 0.5 SD reduction in bone density increases by 50% both childhood and, if sustained, future adult fracture risk (11). Here we show, after accounting for multiple confounders, that TDF use is particularly associated with trabecular bone loss. Whether this translates to increased fracture risk at trabecular rich skeletal sites, such as the wrist and vertebra, is currently unknown.

Our reported pQCT results further extend our previous DXA findings in the same Zimbabwean cohort, where we found a higher prevalence of low TBLH-BMCLBM Z-score, a cortical rich region of interest, (10% vs. 6% p=0.066) and LS-BMAD Z-score, a trabecular rich site (14% vs. 6%; p=0.0007) in CWH compared with their uninfected counterparts (11). Further earlier work in a smaller slightly younger (6 to 16 years) Zimbabwean population identified similar prevalence of low LS-BMAD and TBLH-BMCLBM in CWH (15% and 13% respectively, compared to 1% and 3% in those without HIV) (14). While DXA measured areal BMD does not differentiate trabecular and cortical compartments, the lower LS-BMAD previously reported indicates the possibility of a greater deficit in trabecular bone. This aligns with our unadjusted analysis that showed that trabecular vBMD and not cortical density was lower in CWH than in CWOH. However, this is inconsistent with our adjusted analysis, as we report no differences in both trabecular and cortical density in CWH and CWOH after full adjustment.

Pubertal delay is both a common consequence of HIV infection (11) and a risk factor for poor bone growth (43). Hence, as expected, we saw a greater number of CWH were pre-pubertal, than children without HIV. Pubertal delay could be the reason for compromised bone accrual in CWH. Without stratifying by pre/early vs. mid/late puberty, we would have missed important interactions between HIV and pubertal stage. In our study male CWH in mid/late puberty demonstrated the most adverse skeletal profile. The importance of stratifying by puberty was also demonstrated by a cross-sectional study in the US of 7 to 24 year olds, which similarly reported an HIV*puberty interaction on DXA measured spine and total body bone mineral content and density; the lower bone mass in participants with HIV was more pronounced with advancing puberty (44). However, in this study the differences were more evident in males, whereas in our study we demonstrated differences in both males and females. It is not clear to what extent the difference in the source population (e.g. US vs. Zimbabwe), study sampling (frequency matched based on Tanner stage not age) and/or the age studied, might account for these different findings (44).

Our results suggesting females living with HIV particularly may be entering adulthood with bone size deficits is a concern. Women often experience periods of bone loss, e.g., pregnancy (45), lactation (46) and menopause. Lactation which is a known risk factor for bone loss in African women (46,47), with 83% of Zimbabwean women continuing to breastfeed beyond a 1 year post-partum (48). Coupled with HIV infection and ongoing ART, the risk of adult osteoporosis is high. Recent data from rural South Africa identified a 37% prevalence of femoral neck osteoporosis in women age ≥ 50 years living with HIV (49). Understanding fracture risk in African women living with HIV is an important research priority.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The major strength of this study is the novel use of pQCT in a large population of children in an understudied African population. The comparison with children without HIV, and the fact that the study sample is likely representative of children living in Harare, are study strengths. Our study has several limitations. The analysis is cross-sectional therefore we cannot infer causality. Further, pQCT is not a technique used in clinical practice which limits the ability to relate findings to routine clinical practice. We were unable to compare findings to normative pQCT reference data as there are no established normative pQCT data for children living in sub-Saharan Africa. The study was not powered to stratify by pubertal stage, therefore because males appeared to be transitioning through puberty more slowly than females, the study may not have included sufficient males at more advanced stages of puberty. Small numbers within Tanner stage categories limited our ability to test for interaction, as we needed to group participants in different pubertal stages based on numbers with each stage, rather than pubertal biology. Further follow-up may be helpful in assessing both the male and female children further.

Conclusion

Our results suggest the effect of HIV on bone size and strength differs by pubertal status. We report deficits in bone size and strength associated with HIV infection, which are seen more clearly towards the end of puberty in both male and female children. We further show, for the first time, an indication of attenuated trabecular bone accrual in those using TDF. We expect our findings to be broadly generalizable across populations living in southern Africa, where HIV prevalence is high. Hence these findings have implications for fracture risk in adulthood. The study of fracture incidence, in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, is now a research priority.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the IMVASK study team who assisted in collecting data for this study and also to the participants (and their parents/guardians) for making this study possible.

Funding statement

CM-K is funded by a National Institute of Health Fogarty Trent Fellowship (grant number 2D43TW009539-06). RR is funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 206764/Z/17/Z). Global challenges research funding from the University of Bristol, and an Academy of Medical Sciences GCRF Networking Grant (grant number GCRFNG100399) established the sub-Saharan African MuSculOskeletal Network (SAMSON) and provided the peripheral quantitative computed tomography scanner in Zimbabwe for this study. AMR is partially supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement, which is also part of the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership 2 programme supported by the EU (grant number MR/R010161/1). RAF is funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 206316/Z/17/Z).

Footnotes

Data access statement

Data sharing: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the senior authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy/ ethical restrictions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Iyun V, Technau KG, Vinikoor M, Yotebieng M, Vreeman R, Abuogi L, et al. Variations in the characteristics and outcomes of children living with HIV following universal ART in sub-Saharan Africa (2006–17): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2021. Jun 1;8(6):e353–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF. Reimagining a resilient HIV response for children, adolescents and pregnant women living with HIV. World AIDS Day Rep 2020 [Internet]. 2020;(November):16. Available from: http://www.childrenandaids.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020WorldAIDSDayReport.pdf

- 3.Frigati L, Ameyan W, Cotton M, Gregson C, Hoare J, Jao J, et al. Chronic Comorbidities in Children and Adolescents With Perinatally Acquired HIV Infection in sub- Saharan Africa in the Era of Antiretroviral Therapy. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4642(20):30037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feucht UD, Van Bruwaene L, Becker PJ, Kruger M. Growth in HIV-infected children on long-term antiretroviral therapy. Trop Med Int Heal. 2016;21(5):619–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mchugh G, Rylance J, Mujuru H, Paeds M, Epi C, Bandason T, et al. Chronic Morbidity Among Older Children and Adolescents at Diagnosis of HIV Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):275–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzoli R. Determinants of peak bone mass. Ann Endocrinolo. 2006;67(2):114–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC Jr. The contribution of bone loss to postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1990;1:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel D. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ. 1996;312(7041):1254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez C, Beaupre G, Carte D. A theoretical analysis of the relative influences of peak BMD, age-related bone loss and menopause on the development of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:843–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arpadi SM, Shiau S, Marx-arpadi C, Yin MT. Bone health in HIV-infected children, adoadolescents and young adults: a systematic review. J AIDS Clin Res. 2014;5(11):1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rukuni R, Rehman AM, Mukwasi-Kahari C, Madanhire T, Kowo-Nyakoko F, McHugh G, et al. Effect of HIV infection on growth and bone density in peripubertal children in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a cross-sectional study in Zimbabwe. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal [Internet]. 2021;5(8):569–81. Available from: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00133-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McComsey GA, Tebas P, Shane E, Yin MT, Overton TE, Huang J, et al. Bone Disease in HIV Infection: A Practical Review and Recommendations for HIV Care Providers. Bone. 2011;23(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamill MM, Ward KA, Pettifor JM, Norris SA, Prentice A. Bone mass, body composition and vitamin D status of ARV-naïve, urban, black South African women with HIV infection, stratified by CD4 count. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(11):2855–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregson CL, Hartley A, Majonga E, McHugh G, Crabtree N, Rukuni R, et al. Older age at initiation of antiretroviral therapy predicts low bone mineral density in children with perinatally-infected HIV in Zimbabwe. Bone [Internet]. 2019;125(May):96–102. Available from: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nogueira ML, Ramos I. The role of central DXA measurements in the evaluation of bone mineral density. Eur J Radiogr. 2009;1(4):103–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain RK, Vokes T. Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry. J Clin Densitom. 2017;20(3):291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zemel B, Bass S, Binkley T, Ducher G, Macdonald H, McKay H, et al. Peripheral quantitative computed tomography in children and adolescents: the 2007 ISCD Pediatric Official Positions. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11(1):59–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stagi S, Cavalli L, Cavalli T, de Martino M, Brandi ML. Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) for the assessment of bone strength in most of bone affecting conditions in developmental age: a review. Ital J Pediatr. 2016;42(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiau S, Yin MT, Strehlau R, Burke M, Patel F, Kuhn L, et al. Deficits in Bone Architecture and Strength in Children Living With HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;84(1):101–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rukuni R, Gregson C, Kahari C, Kowo F, Mchugh G, Munyati S, et al. The IMpact of Vertical HIV infection on child and Adolescent SKeletal development in Harare, Zimbabwe ( IMVASK Study ): a protocol for a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(6):459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjo M, Sallis JF, Oja P. International Physical Activity Questionnaire : 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filteau S, Rehman AM, Yousafzai A, Chugh R, Kaur M, Sachdev HPS, et al. Associations of vitamin D status, bone health and anthropometry, with gross motor development and performance of school-aged Indian children who were born at term with low birth weight. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.USAID Working Group on Infant and Young Child Feeding Indicators. Developing and Validating Simple Indicators of Dietary Quality and Energy Intake of Infants and Young Children in Developing Countries : Summary of findings from analysis of 10 data sets Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project (FANTA). 2006;1–99.

- 25.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall WA, Tanner JM . Variations in the Pattern of Pubertal Changes in Boys. Arch Dis Childhood,. 1970;45:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baird J, Walker I, Smith C, Inskip H. Resource report Review of methods for determining pubertal status and age of onset of puberty in cohort and longitudinal studies, London UK. Closer Resour Rep MRC Lifecourse Epidemiol Unit, Univ Southampt. 2017;1–54.

- 28.World Health Organization (WHO). Interpretation Guide Nutrition Landscape Information System. :1–39.

- 29.Arpadi SM. Growth failure in HIV - infected children. World Heal Organ Dep Nutr Heal Dev. 2005;Consultati(Durban, South Africa 10−13):1–20.

- 30.Adams JE, Engelke K, Zemel BS, Ward KA. Quantitative computer tomography in children and adolescents: The 2013 ISCD pediatric official positions. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17(2):258–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leonard MB. A structural approach to the assessment of fracture risk in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1845–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medizintechnik GnmH Stratec. XCT-2000 manual software version 6.20. Pforzheim, Ger Medizintechnik GnmH Strat. 2007;66.

- 33.Szubert AJ, Musiime V, Bwakura-Dangarembizi M, Nahirya-Ntege P, Kekitiinwa A, Gibb DM, et al. Pubertal development in HIV-infected African children on first-line antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2015;29(5):609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cole ZA, Harvey NC, Kim M, Ntani G, Robinson SM, Inskip HM, et al. Increased fat mass is associated with increased bone size but reduced volumetric density in pre pubertal children. Bone [Internet]. 2012;50(2):562–7. Available from: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deere K, Sayers A, Rittweger J, Tobias JH. Habitual levels of high, but not moderate or low, impact activity are positively related to hip BMD and geometry: Results from a population-based study of adolescents. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(9):1887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox AM. The HIV-poverty thesis RE-examined: Poverty, wealth or inequality as a social determinant of hiv infection in sub-Saharan Africa? J Biosoc Sci. 2012;44(4):459–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;339(7713):157–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macdonald H, Chu J, Nettlefold L, Maan EJ, Forbes JC, Côté H, et al. Bone geometry and strength are adapted to muscle force in children and adolescents perinatally infected with HIV. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2013;13(1):53–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poda GG, Hsu CY, Chao JCJ. Malnutrition is associated with HIV infection in children less than 5 years in Bobo-Dioulasso City, Burkina Faso. Med (United States). 2017;96(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tekleab AM, Tadesse BT, Giref AZ, Shimelis D, Gebre M. Anthropometric improvement among HIV infected pre-school children following initiation of first line anti-retroviral therapy: Implications for follow up. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mwiru RS, Spiegelman D, Duggan C, Seage GR, Semu H, Chalamilla G, et al. Growth among HIV-infected children receiving antiretroviral therapy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Trop Pediatr. 2014;60(3):179–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joel DR, Mabikwa V, Makhanda J, Tolle MA, Anabwani GM, Ahmed SF. The prevalence and determinants of short stature in HIV-infected children. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(6):529–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Georgopoulos N, Markou K, Theodoropoulou A, Vagenakis G, Mylonas P, Vagenakis A. Growth, pubertal development, skeletal maturation and bone mass acquisition in athletes. Hormones. 2004;3(4):233–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobson DL, Lindsey JC, Gordon CM, Moye J, Hardin DS, Mulligan K, et al. Total body and spinal bone mineral density across Tanner stage in perinatally HIV-infected and uninfected children and youth in PACTG 1045. AIDS. 2010. Mar;24(5):687–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winter EM, Ireland A, Butterfield NC, Haffner-Luntzer M, Horcajada MN, Veldhuis-Vlug AG, et al. Pregnancy and lactation, a challenge for the skeleton. Endocr Connect. 2020;9(6):R143–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nabwire F, Prentice A, Hamill MM, Fowler MG, Byamugisha J, Kekitiinwa A, et al. Changes in Bone Mineral Density During and After Lactation in Ugandan Women With HIV on Tenofovir-Based Antiretroviral Therapy. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(11):2091–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward KA. Bone Loss and Lactation in Women Living With HIV:Potential Implications for Long-Term Bone Health. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(11):2089–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.UNICEF. Zimbabwe Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2019. Harare: Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gregson CL, Madanhire T, Rehman A, Ferrand RA, Cappola AR, Tollman S, et al. Osteoporosis, Rather Than Sarcopenia, Is the Predominant Musculoskeletal Disease in a Rural South African Community Where Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevalence Is High: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;37(2):244–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.