Abstract

Aims:

We examined diabetes status (no diabetes; type 1 diabetes [T1D]; type 2 diabetes [T2D]) and other demographic and clinical factors as correlates of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related hospitalization. Further, we evaluated predictors of COVID-19-related hospitalization in T1D and T2D.

Methods:

We analyzed electronic health record data from the Cerner Real-World Data™ (CRWD) de-identified COVID-19 database (December 2019 through mid-September 2020; 87 US health systems). Logistic mixed models were used to examine predictors of hospitalization at index encounters associated with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results:

In 116,370 adults (>=18 years old) with COVID-19 (93,098 no diabetes; 802 T1D; 22,470 T2D), factors that independently increased risk for hospitalization included diabetes, male sex, public health insurance, decreased body mass index (BMI; <25.0–29.9 kg/m2), increased BMI (>25.0–29.9 kg/m2), vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, and Elixhauser comorbidity score. After further adjustment for concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis in those with diabetes, hospitalization risk was substantially higher in T1D than T2D and in those with low vitamin D and elevated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

Conclusions:

The higher hospitalization risk in T1D versus T2D warrants further investigation. Modifiable risk factors such as vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, BMI, and elevated HbA1c may serve as prognostic indicators for COVID-19-related hospitalization in adults with diabetes.

Keywords: COVID-19, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes, Hospitalization, Comorbidities, Vitamin D

1. Introduction

Worldwide, approximately 586 million individuals have had coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).1 As of July 2022, more than 6 million deaths are attributed to COVID-19.1 The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and numerous studies have identified both type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) as risk factors for severe COVID-19, including higher rates of hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and mortality.2–5 Other underlying medical conditions, older age, male sex, and vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency are also associated with severe COVID-19 illness.2,4−7

Uneven distribution of worse COVID-19-related outcomes across certain populations in the United States has prompted questions about the disproportionate infection, hospitalization, and mortality burdens experienced by vulnerable ethnic and racial minority populations during the pandemic. Higher rates of COVID-19 positivity,8–12 ICU admission,8,11 hospitalization,9,10,12 and mortality9,10 are frequently noted in ethnic and racial minority populations; however, these findings are not consistent across all minority populations and studies.8,10,12,13

Evaluation of disproportionate adverse effects of COVID-19 on vulnerable populations requires examination of comorbidity burden, ethnic and racial disparities, health insurance status, age, sex, regional, and contributing socioeconomic differences as factors that potentially impact patient outcomes. Many unanswered questions remain about the impact of diabetes, as well as long-term glycemic control, on risk for hospitalization during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in the context of other risk factors. We therefore aimed to examine demographic and clinical characteristics and comorbid conditions as correlates of hospital admission in a nationwide cohort of individuals with and without diabetes with concurrent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and data source

We performed a retrospective analysis of electronic health record (EHR) data from the Cerner Real-World Data™ COVID-19 database to examine correlates of hospitalization in individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Data were extracted from the 2020Q3 release of the nationwide Cerner Real-World Data™ COVID-19 database.14 The dataset contains longitudinal EHR data for 490,373 patients who, between December 2019 and mid-September 2020, had an emergency department (ED), urgent care, or hospital admission encounter associated with a COVID-19-related diagnosis code or with a positive result for a COVID-19-related laboratory test.15

The database includes de-identified EHR data from patients’ COVID-19-related encounters and prior encounters dating back to January 1, 2015. Data were limited to healthcare facilities that use Cerner’s EHR. Eighty-seven U.S. health systems are represented in the 2020Q3 release. We analyzed the outcome of hospitalization at the index qualifying encounter (IQE) that, for each patient, was associated with a diagnosis code or with a laboratory test result indicative of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (Supplemental Tables 1–2).

This study was classified by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board as not being human subjects research, thus informed patient consent was deemed unnecessary.

2.2. Diabetes status definitions

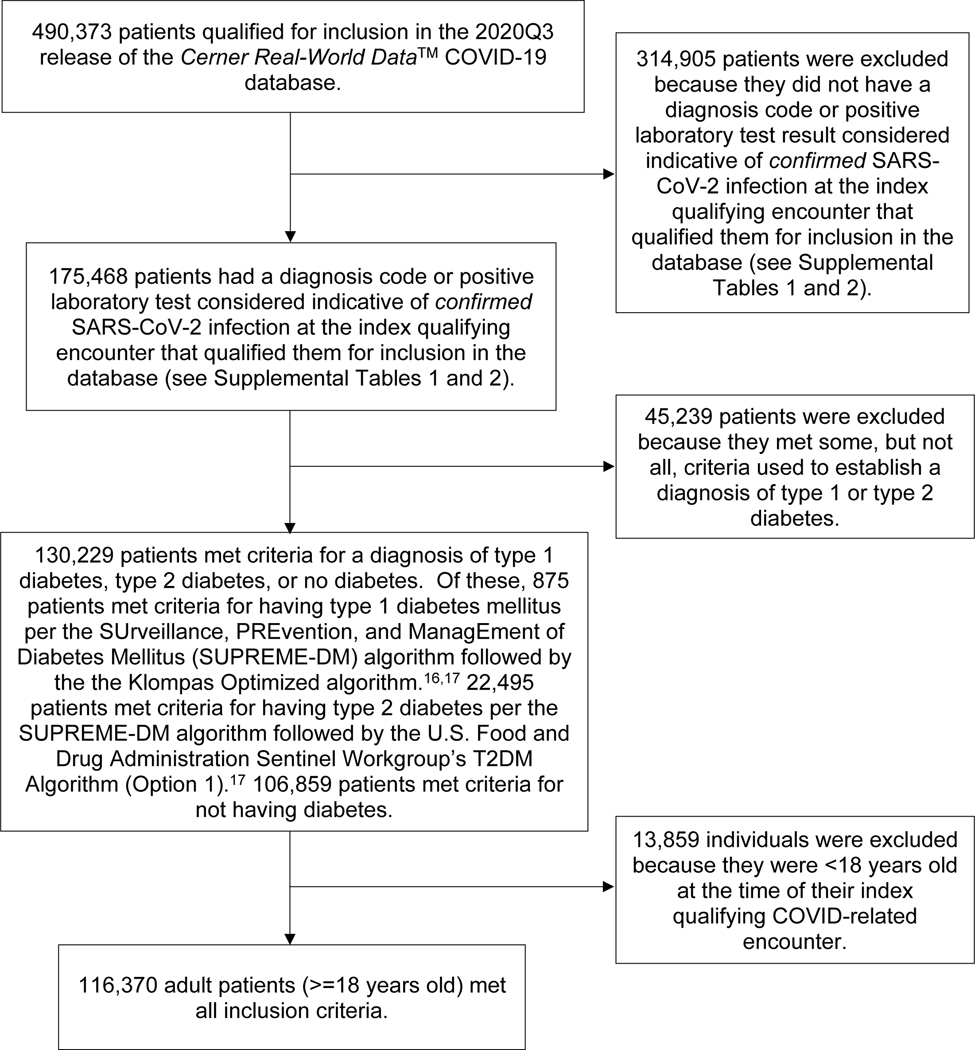

To identify individuals with diabetes, we used logical operations that combined diagnosis, medication, and laboratory data as specified in the SUrveillance, PREvention, and ManagEment of Diabetes Mellitus (SUPREME-DM) Algorithm.16,17 Because the SUPREME-DM Algorithm is based on International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes, we used an online tool (ICD10Data.com) to map International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes in Cerner’s database to the ICD-9 codes specified in the algorithm. Patients were classified as having T1D based on the Klompas Optimized Algorithm, as recommended by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Sentinel Initiative workgroup.17,18 Patients were classified as having T2D using that workgroup’s T2D Algorithm (Option 1).17 Patients with no record of diabetes-related ICD codes or medications, and no documentation of an HbA1c result >=6.5%, fasting plasma glucose level >=126 mg/dL, or random plasma glucose level >=200 mg/dL, were classified as not having diabetes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort identification/selection flowchart

2.3. Patient characteristics

For each patient’s IQE, we extracted data pertaining to encounter type (urgent care, ED, or inpatient/hospitalized), length of stay (inpatients only), mechanical ventilation status (yes/no; Supplemental Table 3), duration of mechanical ventilation, in-hospital expiration status (yes/no), payer status (private health insurance, public health insurance, government/military health insurance, charity/other, or self-pay [including insured and uninsured individuals]; Supplemental Table 4), and health system, including geographic region (i.e., U.S. census division), bed size category (0–99, 100–199, 200–299, 300–499, 500–999, >=1000), and health system type (integrated delivery network, regional hospital, academic, community hospital, community healthcare, children, critical access).

Patient characteristics included age, sex (male, female), race and ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), current and historical HbA1c, presence of concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis, presence of vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, Elixhauser comorbidity score (ECS), and number and type of Elixhauser comorbidities diagnosed. We categorized age as 18–29, 30–39, …, 80–89, or >=90. To protect the identity of pediatric individuals, Cerner masked the ages of patients <18 years old. Without pediatric age data, we were unable to calculate age- and sex-adjusted BMI measurements (i.e., BMI z-scores), which are needed to accurately assess the impact of BMI in a mixed pediatric/adult cohort.19 We therefore excluded pediatric patients (<18 years old) from this analysis.

When patient BMI at the IQE was unavailable and could not be calculated from weight and height, we searched encounters within 12 months (before or after) of the IQE and used the BMI value from the encounter closest in time. For patients without a BMI value in this window, we calculated BMI using the weight at the encounter nearest to and within 12 months of the IQE and height from the most recent encounter at which the patient was at least 18 years old. Similarly, if available, HbA1c was obtained from the IQE or from the nearest encounter within 12 months of the IQE. Historical HbA1c was defined as the HbA1c result documented closest to and >12 months prior to the IQE. Codes used to extract BMI and HbA1c data are in Supplemental Table 5. Processes used for BMI and HbA1c outlier detection are described in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Patients with an ICD-10 code for vitamin D deficiency or a lab result indicating low 25-hydroxyvitamin D (<30 ng/mL) within 90 days of their IQE were classified as having vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency. In individuals with diabetes, we evaluated presence of concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis as a proxy for the presence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or acidosis due to other causes. We used two sets of criteria to identify presence of hyperglycemia and acidosis: (1) blood glucose >200 mg/dL and blood pH <7.35, both documented during a 24-hour time period, and (2) blood glucose >200 mg/dL and serum bicarbonate <15 mEq/L, both documented during a 24-hour time period. Patients with diabetes who met either set of criteria within 168 hours (7 days) of the start of the IQE were classified as having concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis. Codes used to extract vitamin D, pH, bicarbonate, and glucose data are in Supplemental Table 5.

The ECS condenses comorbidity burden to a numeric score.20 ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used to identify the presence of Elixhauser comorbidities and then compute patient ECSs are in Supplemental Table 6.21,22

2.4. Outcome

The primary outcome was hospitalization during the IQE. We defined hospitalization cases as cases in which the individual was either admitted for observation or admitted as an inpatient at the IQE. Health systems frequently merge data from an ED encounter that later results in an inpatient admission into a single (inpatient) encounter record. However, some health systems maintain separate encounter records, even when encounters occur in close proximity to one another and represent a single care episode (e.g., an ED encounter that results in an inpatient admission). To enable capture of all inpatient encounters, we merged, into single care episodes, all ED encounters that occurred within 48 hours of subsequent hospital admission encounters. We classified all such episodes as inpatient encounters.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using HealtheDataLab, Cerner’s data science ecosystem hosted by Amazon Web Services.23 HealtheDataLab was powered by Apache Spark version 2.4.4 (Apache Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE). Data were cleaned and analyzed using Python version 3.7.6 (Python Software Foundation) and R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Incomplete multivariate data were imputed by chained equations under a missing at random assumption.24 We used the mice algorithm in R to create 15 multiply imputed datasets (Supplemental Appendix 2).24 Variability in imputed value estimates across the 15 datasets reflected inherent uncertainty regarding the true values of the missing data.

Only 11.5% of patients who did not have diabetes had a documented HbA1c result. Therefore, prior to using mice to impute missing data, we used mean imputation to impute missing current and historical HbA1c for patients without diabetes. Also, when a patient with diabetes had a recent HbA1c result but no historical HbA1c result, the historical result was imputed as equal to the current HbA1c result.

Data for diabetes type, hospitalization/inpatient status, age, and health system ID were complete. Absence of data used to define cases of Elixhauser comorbidities, vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, and concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis could reflect either true absence of those conditions or inadvertent omission of data from the EHR. We presumed that absent data for these conditions reflected true absence of the conditions. Missing data frequency for other variables is in Supplemental Table 7.

Using the GLMMadaptive package in R, we fit logistic mixed models to each of the 15 imputed datasets, with health system included as a random effect and census division included as a control variable. Model fitting in GLMMadaptive uses the adaptive Gauss-Hermite quadrature rule to approximate the integral over the random effect.25 We used Rubin’s rules, implemented via the parameters package in R, to pool regression model results obtained from the 15 imputed datasets.26

We first examined diabetes status, age, race and ethnicity, payer, sex, BMI, vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, and ECS as correlates of hospitalization at the IQE in patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. We then estimated the impact of these predictors on the odds of hospitalization in a model that included additional predictor variables (i.e., interaction terms) that adjusted for variability in the outcome of hospitalization based on (a) diabetes type X age and (b) diabetes type X race and ethnicity.

Next, we evaluated Elixhauser comorbidities as additional correlates of hospitalization. These models analyzed diabetes status, age, race and ethnicity, payer, sex, BMI, vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, and 27 Elixhauser comorbidities as correlates of hospitalization. Diabetes is an Elixhauser comorbidity, but the Elixhauser coding algorithm does not distinguish between T1D and T2D. We therefore excluded the Elixhauser-diabetes comorbidity variable and retained T1D and T2D as separate covariates. We also excluded the Elixhauser-obesity comorbidity variable since BMI was analyzed as a separate variable in the same models.

Lastly, we examined correlates of hospitalization in the subset of individuals with diabetes. In addition to diabetes type, age, race and ethnicity, payer, sex, BMI, and vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, these models included HbA1c and concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis as additional predictor terms. ECS was not included in these models because the “fluid and electrolyte disorders” Elixhauser comorbidity is composed of conditions (e.g., acidosis and dehydration) similar to criteria used to define the concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis variable.

To control for false positives resulting from multiple hypothesis testing, we used the qvalue package in R to calculate a q-value for each hypothesis test using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. When using this method to control for the positive false discovery rate (pFDR), the calculated q-values are pFDR analogues of p-values.27 The q-value represents the minimum pFDR at which a given test is deemed unlikely to have occurred due to chance.27 We controlled the false discovery rate at 0.1.

3. Results

3.1. Study population characteristics

In this cohort of 116,370 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection, 93,098 (80.0%) did not have diabetes; 22,470 (19.3%) had T2D; and 802 (0.7%) had T1D. Patient characteristics stratified by diabetes status are summarized in Table 1. Patient characteristics for each diabetes status are stratified by race and ethnicity in Supplemental Tables 8-10. Patient characteristics for the 40,885 hospitalized individuals in this study are stratified by census division in Supplemental Table 11.

Table 1.

Patient and health system characteristics for 116,370 adults with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Characteristic | Overall | No diabetes | Type 1 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, No. | 116,370 | 93,098 | 802 | 22,470 |

| Age, years (median [IQR]) | 47.0 [32.0, 62.0] | 42.0 [30.0, 57.0] | 41.0 [29.0, 57.0] | 63.0 [53.0, 74.0] |

| Age categories, years, n (%) | ||||

| 18–29 | 23,187 (19.9) | 22,628 (24.3) | 207 (25.8) | 352 (1.6) |

| 30–39 | 20,102 (17.3) | 18,907 (20.3) | 174 (21.7) | 1,021 (4.5) |

| 40–49 | 19,345 (16.6) | 16,578 (17.8) | 136 (17.0) | 2,631 (11.7) |

| 50–59 | 19,853 (17.1) | 14,816 (15.9) | 110 (13.7) | 4,927 (21.9) |

| 60–69 | 15,300 (13.1) | 9,457 (10.2) | 92 (11.5) | 5,751 (25.6) |

| 70–79 | 10,380 (8.9) | 5,666 (6.1) | 53 (6.6) | 4,661 (20.7) |

| 80–89 | 8,160 (7.0) | 5,017 (5.4) | 30 (3.7) | 3,113 (13.9) |

| ≥90 | 43 (0.0) | 29 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (0.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 62,103 (53.4) | 50,365 (54.1) | 385 (48.0) | 11,353 (50.5) |

| Male | 53,888 (46.3) | 42,460 (45.6) | 413 (51.5) | 11,015 (49.0) |

| Unknown | 379 (0.3) | 273 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | 102 (0.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | 32,323 (27.8) | 25,165 (27.0) | 313 (39.0) | 6,845 (30.5) |

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 18,695 (16.1) | 13,903 (14.9) | 158 (19.7) | 4,634 (20.6) |

| Non-Hispanic, Other | 2,618 (2.2) | 2,204 (2.4) | 8 (1.0) | 406 (1.8) |

| Non-Hispanic, Unknown race | 1,649 (1.4) | 1,255 (1.3) | 21 (2.6) | 373 (1.7) |

| Hispanic | 50,553 (43.4) | 41,764 (44.9) | 245 (30.5) | 8,544 (38.0) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2,362 (2.0) | 1,778 (1.9) | 14 (1.7) | 570 (2.5) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1,777 (1.5) | 1,336 (1.4) | 13 (1.6) | 428 (1.9) |

| Unknown ethnicity, White | 1,846 (1.6) | 1,581 (1.7) | 12 (1.5) | 253 (1.1) |

| Unknown ethnicity, Black | 571 (0.5) | 477 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 92 (0.4) |

| Unknown ethnicity, Other race | 1,147 (1.0) | 959 (1.0) | 9 (1.1) | 179 (0.8) |

| Unknown ethnicity/Unknown race | 2,829 (2.4) | 2,676 (2.9) | 7 (0.9) | 146 (0.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (median [IQR]) | 29.3 [25.4, 34.5] | 29.0 [25.1, 33.9] | 26.5 [22.7, 32.0] | 31.2 [26.9, 37.0 |

| BMI categories, kg/m2, n (%) | ||||

| <18.5 | 1,533 (1.3) | 1,275 (1.4) | 40 (5.0) | 218 (1.0) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 20,506 (17.6) | 17,136 (18.4) | 274 (34.2) | 3,096 (13.8) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 30,704 (26.4) | 24,500 (26.3) | 209 (26.1) | 5,995 (26.7) |

| 30.0–34.9 | 22,757 (19.6) | 17,168 (18.4) | 132 (16.5) | 5,457 (24.3) |

| 35.0–39.9 | 12,248 (10.5) | 8,810 (9.5) | 69 (8.6) | 3,369 (15.0) |

| ≥40 | 10,913 (9.4) | 7,239 (7.8) | 54 (6.7) | 3,620 (16.1) |

| Unknown | 17,709 (15.2) | 16,970 (18.2) | 24 (3.0) | 715 (3.2) |

| Encounter type, n (%) | ||||

| Emergency | 63,674 (54.7) | 57,040 (61.3) | 193 (24.1) | 6,441 (28.7) |

| Admitted/Inpatient | 40,885 (35.1) | 24,854 (26.7) | 593 (73.9) | 15,438 (68.7) |

| Urgent care encounter | 11,811 (10.1) | 11,204 (12.0) | 16 (2.0) | 591 (2.6) |

| Length of stay (inpatient encounters only), days (median [IQR]) | 4.6 [2.3, 8.7] | 3.8 [2.0, 7.0] | 5.1 [2.6, 10.2] | 6.2 [3.1, 12.2] |

| Length of stay categories (inpatient encounters only), days, n (%) | ||||

| 0–3 | 11,126 (9.6) | 8,048 (8.6) | 146 (18.2) | 2,932 (13.0) |

| 4–7 | 9,103 (7.8) | 5,678 (6.1) | 116 (14.5) | 3,309 (14.7) |

| >7 | 19,795 (17.0) | 10,627 (11.4) | 323 (40.3) | 8,845 (39.4) |

| Not applicable | 75,485 (64.9) | 68,244 (73.3) | 209 (26.1) | 7,032 (31.3) |

| Unknown | 861 (0.7) | 501 (0.5) | 8 (1.0) | 352 (1.6) |

| Intubated, n (%) | 7243 (6.2) | 2571 (2.8) | 113 (14.1) | 4559 (20.3) |

| Intubation duration, days (median [IQR]) | 5.0 [1.0, 11.0] | 3.0 [0.0, 7.0] | 5.0 [2.0, 13.0] | 6.0 [2.0, 14.0] |

| Intubation duration categories, days, n (%) | ||||

| 0–3 | 2929 (2.5) | 1388 (1.5) | 38 (4.7) | 1503 (6.7) |

| 4–7 | 1428 (1.2) | 492 (0.5) | 23 (2.9) | 913 (4.1) |

| 8–14 | 1372 (1.2) | 382 (0.4) | 27 (3.4) | 963 (4.3) |

| >14 | 1238 (1.1) | 182 (0.2) | 18 (2.2) | 1038 (4.6) |

| Not applicable | 109403 (94.0) | 90654 (97.4) | 696 (86.8) | 18053 (80.3) |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%)1 | 2793 (2.4) | 902 (1.0) | 37 (4.6) | 1854 (8.3) |

| Payer, n (%) | ||||

| Private insurance | 44,539 (38.3) | 38,836 (41.7) | 252 (31.4) | 5,451 (24.3) |

| Public insurance | 32,902 (28.3) | 22,111 (23.8) | 292 (36.4) | 10,499 (46.7) |

| Government/Military | 2,580 (2.2) | 2,200 (2.4) | 14 (1.7) | 366 (1.6) |

| Charity/Other | 1,468 (1.3) | 1,212 (1.3) | 9 (1.1) | 247 (1.1) |

| Self-pay | 13,466 (11.6) | 12,480 (13.4) | 44 (5.5) | 942 (4.2) |

| Unknown | 21,415 (18.4) | 16,259 (17.5) | 191 (23.8) | 4,965 (22.1) |

| Census Division, n (%) | ||||

| New England | 1,764 (1.5) | 1,341 (1.4) | 25 (3.1) | 398 (1.8) |

| Middle Atlantic | 21,416 (18.4) | 17,050 (18.3) | 152 (19.0) | 4,214 (18.8) |

| South Atlantic | 38,009 (32.7) | 32,046 (34.4) | 165 (20.6) | 5,798 (25.8) |

| East North Central | 4,869 (4.2) | 3,618 (3.9) | 48 (6.0) | 1,203 (5.4) |

| East South Central | 1,977 (1.7) | 1,646 (1.8) | 19 (2.4) | 312 (1.4) |

| West North Central | 5,036 (4.3) | 3,983 (4.3) | 55 (6.9) | 998 (4.4) |

| West South Central | 12,865 (11.1) | 9,475 (10.2) | 116 (14.5) | 3,274 (14.6) |

| Mountain | 15,136 (13.0) | 11,822 (12.7) | 140 (17.5) | 3,174 (14.1) |

| Pacific | 15,298 (13.1) | 12,117 (13.0) | 82 (10.2) | 3,099 (13.8) |

| Health system: Bed size range, n (%) | ||||

| 6–99 | 1,379 (1.2) | 1,025 (1.1) | 6 (0.7) | 348 (1.5) |

| 100–199 | 806 (0.7) | 661 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | 144 (0.6) |

| 200–299 | 2,013 (1.7) | 1,615 (1.7) | 16 (2.0) | 382 (1.7) |

| 300–499 | 8,326 (7.2) | 6,364 (6.8) | 74 (9.2) | 1,888 (8.4) |

| 500–999 | 22,714 (19.5) | 17,455 (18.7) | 200 (24.9) | 5,059 (22.5) |

| ≥1,000 | 81,132 (69.7) | 65,978 (70.9) | 505 (63.0) | 14,649 (65.2) |

| Health system: Segment served, n (%) | ||||

| Integrated Delivery Network | 89,176 (76.6) | 71,968 (77.3) | 566 (70.6) | 16,642 (74.1) |

| Regional Hospital | 14,237 (12.2) | 10,721 (11.5) | 115 (14.3) | 3,401 (15.1) |

| Academic | 11,324 (9.7) | 9,133 (9.8) | 106 (13.2) | 2,085 (9.3) |

| Community Hospital | 825 (0.7) | 617 (0.7) | 3 (0.4) | 205 (0.9) |

| Community Healthcare | 361 (0.3) | 251 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 108 (0.5) |

| Children | 334 (0.3) | 316 (0.3) | 10 (1.2) | 8 (0.0) |

| Critical Access | 113 (0.1) | 92 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (0.1) |

| HbA1c, % (median [IQR]) | 6.7 [5.7, 8.4] | 5.5 [5.2, 5.8] | 9.5 [7.7, 12.0] | 7.5 [6.5, 9.3] |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol (median [IQR]) | 50 [39, 68] | 37 [33, 40] | 80 [61, 108] | 58 [48, 78] |

| Concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis, n (%) | 2,452 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 182 (22.7) | 2,270 (10.1) |

| Vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, n (%)2 | 3,227 (2.8) | 1,528 (1.6) | 84 (10.5) | 1,615 (7.2) |

| Low vitamin D, lab result not present, n (%)3 | 1,572 (48.7) | 747 (48.9) | 38 (45.2) | 787 (48.7) |

| Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D result present, n (%)4 | 2,753 (2.4) | 1,347 (1.4) | 55 (6.9) | 1,351 (6.0) |

| Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ng/mL (median [IQR])5 | 27.7 [18.3, 39.1] | 28.8 [19.5, 39.3] | 22.3 [12.9, 28.9] | 27.1 [17.8, 39.2] |

| Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D <20 ng/mL, n (%) | 842 (0.7) | 375 (0.4) | 25 (3.1) | 442 (2.0) |

| Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D 20–30 ng/mL, n (%) | 813 (0.7) | 406 (0.4) | 21 (2.6) | 386 (1.7) |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score (median [IQR]) | 0.0 [0.0, 6.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 5.0] | 8.0 [3.0, 19.0] | 10.0 [3.0, 19.0] |

| Elixhauser comorbidity groups, n (median [IQR]) | 1.0 [0.0, 4.0] | 1.0 [0.0, 2.0] | 5.0 [3.0, 8.0] | 6.0 [4.0, 8.0] |

| EC - Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 9,347 (8.0) | 3,209 (3.4) | 168 (20.9) | 5,970 (26.6) |

| EC - Cardiac arrhythmias, n (%) | 20,126 (17.3) | 11,452 (12.3) | 304 (37.9) | 8,370 (37.2) |

| EC - Valvular disease, n (%) | 5,418 (4.7) | 2,387 (2.6) | 83 (10.3) | 2,948 (13.1) |

| EC - Pulmonary circulation disorders, n (%) | 4,230 (3.6) | 1,903 (2.0) | 78 (9.7) | 2,249 (10.0) |

| EC - Peripheral vascular disorders, n (%) | 5,623 (4.8) | 2,075 (2.2) | 95 (11.8) | 3,453 (15.4) |

| EC - Hypertension, n (%) | 44,029 (37.8) | 23,672 (25.4) | 510 (63.6) | 19,847 (88.3) |

| EC - Paralysis, n (%) | 1,714 (1.5) | 684 (0.7) | 25 (3.1) | 1,005 (4.5) |

| EC - Neurodegenerative disorders, n (%) | 5,372 (4.6) | 3,096 (3.3) | 113 (14.1) | 2,163 (9.6) |

| EC - Chronic pulmonary disease, n (%) | 21,765 (18.7) | 14,097 (15.1) | 181 (22.6) | 7,487 (33.3) |

| EC - Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 9,501 (8.2) | 5,375 (5.8) | 151 (18.8) | 3,975 (17.7) |

| EC - Renal failure, n (%) | 10,460 (9.0) | 3,096 (3.3) | 273 (34.0) | 7,091 (31.6) |

| EC - Liver disease, n (%) | 8,221 (7.1) | 4,247 (4.6) | 122 (15.2) | 3,852 (17.1) |

| EC - Peptic ulcer disease (no bleeding), n (%) | 1,269 (1.1) | 583 (0.6) | 25 (3.1) | 661 (2.9) |

| EC - AIDS/HIV, n (%) | 620 (0.5) | 459 (0.5) | 5 (0.6) | 156 (0.7) |

| EC - Lymphoma, n (%) | 482 (0.4) | 278 (0.3) | 9 (1.1) | 195 (0.9) |

| EC - Metastatic cancer, n (%) | 1,060 (0.9) | 561 (0.6) | 9 (1.1) | 490 (2.2) |

| EC - Solid tumor without metastasis, n (%) | 3,915 (3.4) | 2,045 (2.2) | 32 (4.0) | 1,838 (8.2) |

| EC - RA/collagen vascular diseases, n (%) | 2,934 (2.5) | 1,723 (1.9) | 40 (5.0) | 1,171 (5.2) |

| EC - Coagulopathy, n (%) | 7,356 (6.3) | 3,553 (3.8) | 136 (17.0) | 3,667 (16.3) |

| EC - Obesity, n (%) | 23,118 (19.9) | 12,443 (13.4) | 221 (27.6) | 10,454 (46.5) |

| EC - Weight loss, n (%) | 5,490 (4.7) | 2,498 (2.7) | 165 (20.6) | 2,827 (12.6) |

| EC - Fluid and electrolyte disorders, n (%) | 33,550 (28.8) | 18,512 (19.9) | 615 (76.7) | 14,423 (64.2) |

| EC - Blood loss anemia, n (%) | 1,192 (1.0) | 513 (0.6) | 27 (3.4) | 652 (2.9) |

| EC - Deficiency anemia, n (%) | 5,842 (5.0) | 2,714 (2.9) | 152 (19.0) | 2,976 (13.2) |

| EC - Alcohol abuse, n (%) | 375 (0.3) | 243 (0.3) | 8 (1.0) | 124 (0.6) |

| EC - Drug abuse, n (%) | 5,958 (5.1) | 4,239 (4.6) | 145 (18.1) | 1,574 (7.0) |

| EC - Psychosis, n (%) | 2,544 (2.2) | 1,600 (1.7) | 36 (4.5) | 908 (4.0) |

| EC - Depression, n (%) | 13,035 (11.2) | 7,615 (8.2) | 245 (30.5) | 5,175 (23.0) |

In-hospital mortality was defined as a discharge disposition of “Expired” in conjunction with the COVID-related encounter.

Vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency status was extracted from Cerner’s COVID-19 database via International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes indicating low vitamin D status and/or via laboratory testing indicating low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (<30 ng/mL). Codes used to extract vitamin D data are in Supplemental Table 5.

Individuals whose low vitamin D status was documented via an ICD-10 code -- but not via laboratory testing -- within 90 days of the index qualifying encounter associated with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Individuals who had at least one serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D laboratory test result within 90 days of the index qualifying encounter associated with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Calculated using serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D laboratory testing results for all individuals, regardless of vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency status.

Abbreviations: AIDS/HIV, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/human immunodeficiency virus; BMI, body mass index; EC, Elixhauser comorbidity; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

3.2. Correlates of hospitalization in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection

The fully adjusted model fit to data for the entire study cohort showed that the diabetes status associated with the highest odds of hospitalization was T1D (vs. no diabetes; adjusted OR [AOR], 5.06; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.23–6.06; Q<0.001) (Table 2; Supplemental Figure 1; Supplemental Table 12). Odds of hospitalization were also substantially elevated in T2D (vs. no diabetes; AOR, 2.16; 95% CI, 2.07–2.25; Q<0.001) (Table 2). We observed in adjusted models that, relative to Non-Hispanic White patients, hospitalization risk was decreased in Non-Hispanic Black patients (AOR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.79–0.87; Q<0.001) and in Hispanic patients (AOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80–0.87; Q<0.001). AAPI/AIAN/NHO individuals were more likely to be hospitalized than Non-Hispanic White individuals (AOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.00–1.13; Q=0.068). We also observed positive relationships between hospitalization and older age, public health insurance (vs. private health insurance; AOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.33–1.48; Q<0.001), male sex (AOR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.18–1.25; Q<0.001), vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency (AOR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.56–1.87; Q<0.001), and ECS (AOR, 1.08; 95% CI 1.08–1.08; Q<0.001). A J-shaped association existed between BMI and hospitalization (Table 2; Supplemental Figure 1). Odds of hospitalization were decreased for self-pay patients (vs. private insurance; AOR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.65–0.76; Q<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios: Correlates of hospitalization in adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Model | Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)* |

q-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elixhauser comorbidity score | Diabetes status | ||

| No diabetes | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | 5.06 (4.23–6.06) | <0.001 | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2.16 (2.07–2.25) | <0.001 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–29 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 30–39 | 1.16 (1.10–1.22) | <0.001 | |

| 40–49 | 1.32 (1.25–1.39) | <0.001 | |

| 50–59 | 1.86 (1.76–1.95) | <0.001 | |

| 60–69 | 2.59 (2.45–2.74) | <0.001 | |

| 70–79 | 3.48 (3.25–3.72) | <0.001 | |

| 80+ | 6.22 (5.75–6.72) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Male | 1.22 (1.18–1.25) | <0.001 | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | <0.001 | |

| Hispanic | 0.84 (0.80–0.87) | <0.001 | |

| AAPI/AIAN/NHO | 1.06 (1.00–1.13) | 0.068 | |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Public insurance | 1.40 (1.33–1.48) | <0.001 | |

| Government/Military | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | 0.291 | |

| Charity/Other | 1.10 (0.94–1.28) | 0.345 | |

| Self-pay | 0.70 (0.65–0.76) | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| 18.5–24.9 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| <18.5 | 1.22 (1.08–1.39) | 0.003 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.217 | |

| 30.0–34.9 | 1.15 (1.10–1.21) | <0.001 | |

| 35.0–39.9 | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | <0.001 | |

| >=40 | 1.71 (1.61–1.81) | <0.001 | |

| Census division | |||

| West South Central | 1 [Reference] | ||

| East North Central | 1.09 (0.54–2.21) | 0.832 | |

| East South Central | 1.67 (0.56–5.01) | 0.447 | |

| Middle Atlantic | 1.58 (0.56–4.41) | 0.469 | |

| Mountain | 1.17 (0.51–2.66) | 0.758 | |

| New England | 1.59 (0.65–3.92) | 0.398 | |

| Pacific | 0.87 (0.38–2.03) | 0.793 | |

| South Atlantic | 0.74 (0.29–1.86) | 0.592 | |

| West North Central | 0.78 (0.39–1.55) | 0.553 | |

| Vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency | 1.71 (1.56–1.87) | <0.001 | |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score | 1.08 (1.08–1.08) | <0.001 | |

| Elixhauser comorbidities | Diabetes status | ||

| No diabetes | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | 2.69 (2.23–3.25) | <0.001 | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 1.48 (1.41–1.55) | <0.001 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–29 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 30–39 | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 0.018 | |

| 40–49 | 1.16 (1.10–1.23) | <0.001 | |

| 50–59 | 1.58 (1.50–1.67) | <0.001 | |

| 60–69 | 2.16 (2.04–2.30) | <0.001 | |

| 70–79 | 2.87 (2.67–3.09) | <0.001 | |

| 80+ | 4.78 (4.39–5.20) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Male | 1.19 (1.16–1.23) | <0.001 | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) | <0.001 | |

| Hispanic | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | <0.001 | |

| AAPI/AIAN/NHO | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) | 0.005 | |

| Payer | |||

| Private insurance | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Public insurance | 1.25 (1.19–1.32) | <0.001 | |

| Government/Military | 0.86 (0.74–1.00) | 0.076 | |

| Charity/Other | 1.08 (0.91–1.29) | 0.447 | |

| Self-pay | 0.71 (0.66–0.76) | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| 18.5–24.9 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| <18.5 | 1.14 (1.00–1.30) | 0.073 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 1.06 (1.02–1.11) | 0.013 | |

| 30.0–34.9 | 1.16 (1.10–1.22) | <0.001 | |

| 35.0–39.9 | 1.28 (1.21–1.36) | <0.001 | |

| >=40 | 1.54 (1.45–1.64) | <0.001 | |

| Census division | |||

| West South Central | 1 [Reference] | ||

| East North Central | 1.36 (0.66–2.82) | 0.484 | |

| East South Central | 3.01 (1.07–8.51) | 0.063 | |

| Middle Atlantic | 2.71 (1.04–7.05) | 0.067 | |

| Mountain | 1.55 (0.67–3.55) | 0.393 | |

| New England | 2.21 (0.90–5.39) | 0.126 | |

| Pacific | 1.47 (0.71–3.06) | 0.393 | |

| South Atlantic | 1.40 (0.67–2.95) | 0.456 | |

| West North Central | 1.09 (0.54–2.20) | 0.834 | |

| Vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency | 1.46 (1.33–1.61) | <0.001 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.37 (1.28–1.47) | <0.001 | |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1.30 (1.24–1.36) | <0.001 | |

| Valvular disease | 0.91 (0.83–0.99) | 0.049 | |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 1.93 (1.76–2.13) | <0.001 | |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | 0.063 | |

| Hypertension | 1.39 (1.33–1.45) | <0.001 | |

| Paralysis | 1.73 (1.50–2.01) | <0.001 | |

| Neurodegenerative disorders | 1.41 (1.31–1.53) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | 0.025 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 0.020 | |

| Renal failure | 1.42 (1.33–1.52) | <0.001 | |

| Liver disease | 1.05 (0.98–1.11) | 0.215 | |

| Peptic ulcer disease (no bleeding) | 0.79 (0.68–0.93) | 0.006 | |

| AIDS/HIV | 1.42 (1.17–1.72) | 0.001 | |

| Lymphoma | 1.06 (0.83–1.36) | 0.687 | |

| Metastatic cancer | 1.71 (1.41–2.08) | <0.001 | |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 0.913 | |

| RA/collagen vascular diseases | 0.96 (0.87–1.06) | 0.484 | |

| Coagulopathy | 2.91 (2.70–3.13) | <0.001 | |

| Weight loss | 1.61 (1.48–1.76) | <0.001 | |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 3.75 (3.61–3.88) | <0.001 | |

| Blood loss anemia | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | 0.832 | |

| Deficiency anemia | 1.32 (1.22–1.43) | <0.001 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.85 (0.65–1.12) | 0.343 | |

| Drug abuse | 1.20 (1.11–1.28) | <0.001 | |

| Psychosis | 1.25 (1.12–1.38) | <0.001 | |

| Depression | 0.90 (0.86–0.95) | <0.001 |

Forest plots of the adjusted odds ratios for each model are in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2. Unadjusted odds ratios are in Supplemental Table 12.

Abbreviations: AAPI/AIAN/NHO, Asian American/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic Other; AIDS/HIV, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/human immunodeficiency virus; BMI, body mass index; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

3.3. Interaction effects as correlates of hospitalization in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19

Results from the model that evaluated interaction effects (i.e., diabetes type X age; diabetes type X race and ethnicity) in addition to the predictor terms previously described indicated that the decreased odds of hospitalization observed in Non-Hispanic Black individuals in the overall cohort were attenuated in Non-Hispanic Black individuals with T2D (Table 3; Supplemental Table 13). We also found that the risk-increasing effect of diabetes was markedly stronger among AAPI/AIAN/NHO individuals than among Non-Hispanic White individuals (Table 3; Supplemental Table 13).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios: Interaction effects for diabetes status by age group and race and ethnicity

| Effect of diabetes status by age group* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 18–29 | Age 30–39 | Age 40–49 | Age 50–59 | Age 60–69 | Age 70–79 | Age 80+ | |

| No diabetes diagnosis | 1 (No diabetes, main effect aOR) | 1.14 | 1.28 | 1.83 | 2.60 | 3.74 | 7.01 |

| T1D | 5.39 (T1D main effect) | 5.54 | 3.55 | 7.01 | 7.91 | 17.46 | 17.47 |

| T2D | 2.22 (T2D main effect) | 3.02 | 3.13 | 4.01 | 5.39 | 6.39 | 9.55 |

| Effect of diabetes status by race and ethnicity** | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | AAPI/AIAN/NHO | ||||

| No diabetes diagnosis | 1 (No diabetes, main effect aOR) | 0.81 | 0.83 | 1.07 | |||

| T1D | 5.39 (T1D main effect) | 6.37 | 5.25 | 16.52 | |||

| T2D | 2.22 (T2D main effect) | 2.07 | 1.92 | 2.30 | |||

The referent group for the “diabetes status X age” interaction term was the group of individuals who did not have diabetes who were age 18–29. The referent group for the “diabetes status X race and ethnicity” interaction term was the group of individuals who did not have diabetes who were Non-Hispanic White. Beta coefficients and q-values for the fully adjusted model are in Supplemental Table 13.

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; AAPI/AIAN/NHO, Asian American/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic Other; T1D, Type 1 diabetes; T2D, Type 2 diabetes

3.4. Elixhauser comorbidities as correlates of hospitalization in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection

In the entire cohort of patients with and without diabetes, we additionally evaluated Elixhauser comorbidities as correlates of increased hospitalization risk. After adjustment for all comorbidities, odds of hospitalization were highest in patients with fluid and electrolyte disorders, coagulopathy, T1D, pulmonary circulation disorders, paralysis, and metastatic cancer (Table 2; Supplemental Figure 2; Supplemental Table 12). In the same model, adjusted odds were decreased for patients with peptic ulcer disease, depression, valvular disease, peripheral vascular disorders, and chronic pulmonary disease.

3.5. Correlates of hospitalization in patients with diabetes with SARS-CoV-2 infection

Results from the model fit to data for individuals with diabetes indicated that patients with T2D were less likely to be hospitalized than patients with T1D (AOR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.53–0.78; Q<0.001) (Table 4; Supplemental Figure 3; Supplemental Table 14). Hispanic patients were substantially less likely to be hospitalized than Non-Hispanic White patients (AOR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.66–0.79; Q<0.001). We also observed positive relationships between the odds of hospitalization and HbA1c (one percent increase in HbA1c; AOR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04–1.07; Q<0.001), as well as vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency (AOR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.33–1.73; Q<0.001) (Table 4). Other factors associated with increased odds of hospitalization included male sex (AOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.31–1.49; Q<0.001), public health insurance (vs. private health insurance; AOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.21–1.45; Q<0.001) and BMI <18.5 kg/m2 (vs. 18.5–24.9 kg/m2; AOR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.27–2.80; Q=0.003). Relative to those whose BMI was 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, individuals whose BMI was 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, or 35.0–39.9 kg/m2 were less likely to be hospitalized. BMI >=40 kg/m2 was not a significant predictor for hospitalization in this cohort (Table 4; Supplemental Figure 3). Relative to the West South Central census division, higher odds of hospitalization were observed in the geographic regions comprising the Middle Atlantic census division (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) and the East South Central census division (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee) (Table 4; Supplemental Figure 3).

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios: Correlates of hospitalization in adults with diabetes with SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Type 2 diabetes | 0.65 (0.53–0.78) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–29 | 1 [Reference] | |

| 30–39 | 1.55 (1.23–1.95) | <0.001 |

| 40–49 | 1.64 (1.32–2.03) | <0.001 |

| 50–59 | 2.36 (1.91–2.91) | <0.001 |

| 60–69 | 3.69 (2.98–4.55) | <0.001 |

| 70–79 | 5.41 (4.34–6.74) | <0.001 |

| 80+ | 9.16 (7.25–11.57) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | |

| Male | 1.40 (1.31–1.49) | <0.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.94 (0.85–1.04) | 0.345 |

| Hispanic | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | <0.001 |

| AAPI/AIAN/NHO | 0.92 (0.81–1.05) | 0.334 |

| Payer | ||

| Private insurance | 1 [Reference] | |

| Public insurance | 1.32 (1.21–1.45) | <0.001 |

| Government/Military | 1.07 (0.81–1.41) | 0.696 |

| Charity/Other | 1.20 (0.87–1.64) | 0.350 |

| Self-pay | 0.79 (0.68–0.91) | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| 18.5–24.9 | 1 [Reference] | |

| <18.5 | 1.89 (1.27–2.80) | 0.003 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 0.83 (0.75–0.93) | 0.002 |

| 30.0–34.9 | 0.74 (0.67–0.83) | <0.001 |

| 35.0–39.9 | 0.83 (0.73–0.94) | 0.005 |

| >=40 | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 0.553 |

| Census division | ||

| West South Central | 1 [Reference] | |

| East North Central | 1.18 (0.59–2.35) | 0.702 |

| East South Central | 3.67 (1.35–9.97) | 0.019 |

| Middle Atlantic | 2.38 (1.01–5.58) | 0.073 |

| Mountain | 1.24 (0.56–2.72) | 0.667 |

| New England | 1.54 (0.63–3.78) | 0.436 |

| Pacific | 1.33 (0.66–2.67) | 0.505 |

| South Atlantic | 1.36 (0.69–2.66) | 0.456 |

| West North Central | 0.77 (0.40–1.50) | 0.526 |

| Vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency | 1.52 (1.33–1.73) | <0.001 |

| Concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis | 11.50 (9.31–14.20) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c* | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | <0.001 |

A forest plot of the adjusted odds ratios is in Supplemental Figure 3. Unadjusted odds ratios are in Supplemental Table 14.

HbA1c was analyzed as a continuous variable, in NGSP units (%).

Abbreviations: AAPI/AIAN/NHO, Asian American/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic Other; BMI, body mass index

4. Discussion

We evaluated factors associated with hospitalization in adults with and without diabetes with concurrent SARS-CoV-2 infection. We subsequently analyzed factors associated with hospitalization in the subset of adults with diabetes.

A key finding from our analysis of the entire cohort is that the odds of hospitalization, relative to individuals with no diabetes diagnosis, were higher for those with T1D than those with T2D. A similar finding was reported in a smaller population-based study in Greater Manchester, UK.28 We expand upon this previous finding using a larger patient cohort that adjusts for clustering of patients within health systems. To our knowledge, this is the first US-based, nationwide study to comprehensively evaluate risk factors for hospitalization in a population of individuals with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection with well-characterized diabetes status (no diabetes, T1D, or T2D).

Another key finding was that, after additionally controlling for HbA1c and concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis in the subset of patients with diabetes, hospitalization risk remained substantially higher in T1D than T2D. This finding, which suggests that baseline risk for severe COVID-19 is higher in T1D than T2D, is consistent with earlier evidence that COVID-19-associated mortality is higher in T1D than T2D.29 Although the reasons for this difference are not fully known, prior research demonstrates that compromised cardiometabolic and renal health are strongly linked with worse outcomes in COVID-19.6,30 Given that the burden of cardiovascular and renal disease is higher in T1D than T2D,31 it is possible that the increased cardiovascular and renal disease burden in individuals with T1D may be a factor underlying the more severe outcomes, as well as increased odds of hospitalization, observed in these individuals. In our cohort, we found that the proportions of individuals with T1D vs. T2D who were affected by cardiac arrhythmias, valvular disease, pulmonary circulation disorders, peripheral vascular disorders, and renal failure were similar, even though median age in the T1D cohort was 22 years younger than that of the T2D cohort (Table 1). Further study is needed to elucidate the underlying cause(s) of these more severe outcomes in T1D.

4.1. Entire study cohort

This study is one of the first to meaningfully report COVID-associated risk for hospitalization in AAPI/AIAN/NHO individuals. We found that AAPI/AIAN/NHO race/ethnicity status exerted a non-additive effect that exacerbated the increased hospitalization risk associated with diabetes. In other words, the risk increase associated with diabetes was more pronounced among AAPI/AIAN/NHO individuals than among Non-Hispanic White individuals. Of note, all 13 AAPI/AIAN/NHO individuals with T1D were hospitalized (Supplemental Table 9). Given the small number of individuals in this subgroup (n=13), however, additional studies are needed to validate this finding.

Contrary to our expectations, we found that risk for hospitalization in the overall cohort was decreased in Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals, relative to Non-Hispanic White individuals. Our models adjusted for geographic region and payer status (a proxy for socioeconomic status), as potential confounders of the association between race and ethnicity and COVID-19-related hospitalization. Relative to Non-Hispanic White individuals, a higher percentage of IQEs for Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and AAPI/AIAN/NHO individuals were ED encounters, rather than inpatient encounters (Supplemental Tables 8-10). The lower odds of hospitalization observed in Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals may reflect increased utilization of EDs for COVID-19 encounters that did not require subsequent hospitalization. Alternatively, Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals whose IQEs were ED encounters may have been less likely than Non-Hispanic White individuals to consent to hospital admission; or perhaps they were less likely, overall, to access care for their condition.

A considerable body of research has focused on disproportionate risk of more severe COVID-19 illness in ethnic and racial minority populations. While it is generally agreed that racial and ethnic minority populations are at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and perhaps also COVID-19-related hospitalization, the totality of the evidence pertaining to COVID-19-related outcomes such as ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and mortality is mixed.8–13 Prior studies support the conclusion that Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals are at increased risk of hospitalization,9,10 although one meta-analysis noted inconsistent findings for Non-Hispanic Black individuals.9 A separate meta-analysis that also adjusted for comorbidities concluded that the odds of hospitalization among Hispanic individuals may be slightly higher than that of Non-Hispanic White individuals, while the risk for Non-Hispanic Black and Asian individuals was not substantially different from that of Non-Hispanic White individuals.13 Overall, in patients with and without diabetes, evidence from previous studies suggests that race and ethnicity is likely not an independent risk factor for hospitalization in individuals with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, as one of the first studies to report on this outcome in AAPI/AIAN/NHO individuals, our finding that the risk of hospitalization is elevated in this patient subgroup warrants further study.

Our results for the entire study cohort (with and without diabetes) are consistent with those found in existing literature, which note that diabetes,2,5,6 older age,5 male sex,5 public insurance32,33, and increased BMI34,35 are associated with increased risk for COVID-19-related hospitalization. Further, we found that vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency was an independent risk factor for hospitalization. This finding persisted regardless of the method used to adjust for comorbidity burden, viz., a condensed numeric score (i.e., ECS) or full adjustment for individual underlying conditions. The present study is, by far, the largest US-based study to evaluate the relationship between vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency and risk for hospitalization in COVID-19, as well as to adjust for potential confounding from a large number of underlying medical conditions.36–38

4.2. Subset of individuals with diabetes

Our findings also indicate that a positive relationship exists between HbA1c and risk for hospitalization in patients with diabetes, underscoring the potential role of long-term glycemic control in advancing risk stratification efforts. Although some studies have identified elevated HbA1c as a prognostic indicator for increased inflammatory markers, disease progression, and higher mortality risk in COVID-19 illness,39–42 other studies have not.28,42,43 Of note, the latter studies did not evaluate the outcome of hospitalization in individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Further evaluation of HbA1c data in this study indicated that median HbA1c was higher in hospitalized (versus non-hospitalized) individuals with both T1D and T2D, particularly in individuals in the youngest age groups (Supplemental Figure 4).

We report that vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency increases odds of hospitalization in individuals with diabetes and SARS-CoV-2 infection, as previously described.7,39,44 The widely reported relationship between low vitamin D and diabetes is likely multifactorial in nature and is hypothesized to result from decreased uptake of vitamin D due to diabetes-related autonomic neuropathy, reduced dietary intake of vitamin D, less outdoor exposure to sunlight secondary to decreased physical activity, and/or reduced activation of vitamin D3 in the kidney secondary to insulin deficiency.44–46 There is a growing body of evidence that indicates that low vitamin D is associated with hypoxemia, increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and increased inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers during COVID-19 illness.39,44 A recent line of research established that individuals with T1D with concurrent SARS-CoV-2 infection had demonstrably lower vitamin D levels, relative to controls and to individuals with T1D who were not infected.39 In persons with T1D with and without SARS-CoV-2, vitamin D levels negatively correlated with LDH, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ferritin, and D-dimer – all prognostic indicators of worse outcomes in COVID-19 illness.39

Analysis of the entire cohort suggests a J-shaped association of BMI with risk of hospitalization (Supplemental Figure 1). However, in the subset of patients with diabetes, heightened risk was only present in those with the lowest BMI (<18.5 kg/m2). Elevated risk observed in those with low BMI may reflect unmeasured confounding due to factors related to weight reduction that were not included in our models or to other unknown confounding variables. Alternatively, this finding may represent a true effect, similar to a previous study that noted excess risk for mortality in individuals with diabetes who had low BMI and concurrent SARS-CoV-2 infection.47 The finding that hospitalization risk was not substantially increased in those with diabetes with high BMI (>=40.0 kg/m2) was unexpected. However, if the association between BMI and hospitalization is related to deposition of excess ectopic fat, which is also implicated in the pathophysiology of T2D, it can be hypothesized that an attenuated association with elevated BMI exists in this population.47,48

4.3. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its large size, adjustment for differences across health systems, and comprehensive evaluation of associations between demographic, clinical, and comorbidity factors associated with COVID-19 hospitalization. This study uses real-world EHR data to examine a well-characterized population of individuals with and without diabetes, thereby strengthening confidence in our findings across each diabetes status.

This study also has several limitations. Given that this study aimed to evaluate the impact of sociodemographic and comorbidity factors on the odds of COVID-19-related hospitalization, we limited variables in our analysis to those that reflected such factors. This study’s results must therefore be interpreted with the understanding that inclusion of additional clinical variables (e.g., vital signs at admission, intubation status, etc.) would likely modify relationships observed in this analysis.

EHRs serve as rich repositories of longitudinal health data that can be analyzed for clinical and public health research, but issues pertaining to data quality must be considered. As in other studies that have analyzed large-scale EHR data, we used various data elements in CRWD (e.g., ICD codes, temporal criteria, etc.) to develop clinically relevant case definitions for clinical phenotypes and comorbid conditions. A limitation of this approach is that few such case definitions have been rigorously validated using manual chart review. Therefore, although we employed case definitions (and in some cases, used previously published algorithms) that we believe captured the vast majority of patients presenting with various characteristics or comorbidities, it is possible that patients with some conditions – including those with diabetes – were misclassified or not identified.

For example, our case definition for COVID-19 was based on presence of a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test result for SARS-CoV-2 infection. As such, an important limitation is that individuals with true infection who had false-negative PCR test results were excluded from analysis, whereas individuals with false-positive PCR results were included.

Our model estimates suggest that the odds of hospitalization in individuals with certain comorbidities (e.g., peptic ulcer disease, depression, valvular disease, peripheral vascular disorders, and chronic pulmonary disease) were decreased, relative to individuals who did not have those comorbidities. There could be several explanations for these findings. The comorbidity measures developed by Elixhauser et al.21,22 (also referred to as “Elixhauser comorbidities”) are frequently used in studies of administrative (i.e., claims) and EHR data, to adjust for comorbidity burden in health outcomes research. Importantly, however, the definitions for these comorbidity measures were developed using administrative data. Therefore, the case definitions for each condition are based only on presence/absence of diagnosis codes and do not account for other data types (e.g., prescriptions, laboratory results, etc.) that may be useful for identifying presence of comorbid conditions. Also, certain Elixhauser comorbidities represent broad categories of health conditions. For example, conditions that fall under the category of “chronic pulmonary disease” include bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, and pneumoconiosis, as well as respiratory conditions caused by inhalation of other agents.21 It is possible that some of the individual conditions captured under the term “chronic pulmonary disease” may be associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization, while others may not. For example, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease conferred increased risk of hospitalization in individuals with COVID-19; however, asthma did not.49

We used diagnosis codes and laboratory testing results to improve capture of cases of low vitamin D; however, doing so resulted in the loss of some granularity in the data. Given that individuals with a diagnosis code for low vitamin D did not always have a corresponding lab result confirming their vitamin D status, we defined low vitamin D, in instances where lab results were available, as a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D threshold of <30 ng/mL. Additional studies with more complete lab result data are needed to evaluate the impact of low vitamin D using different thresholds (e.g., <20 ng/mL vs. <30 ng/mL). Of note, some health insurance (e.g., Medicare) does not cover the cost of routine serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D screening, which may result in underestimation of the true prevalence of vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency.

Inherent differences in diagnostic and lab coding practices across healthcare systems did not allow us to consistently distinguish between presence of acidosis due to DKA and presence of acidosis due to other underlying causes (e.g., sepsis). For this reason, our statistical models adjusted for concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis, rather than DKA. Additional research is needed to develop and validate an optimal case definition for DKA in aggregate EHRs.

CRWD is subject to errors in data entry or missing data that can happen as part of clinical care. To minimize this impact, we performed continuous data quality checks, used robust data outlier detection methods, and employed multiple imputation to address issues related to incomplete data. Because our analysis was limited to healthcare systems that use Cerner’s EHR and have a signed data use agreement with Cerner, findings may not generalize to all health systems.

Results from this study have important implications for addressing concerns related to modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for COVID-19-related hospitalization. Several risk factors identified in this analysis (e.g., BMI, HbA1c, and low vitamin D) are modifiable through healthcare or self-management interventions. We suggest that these findings, along with results from similar studies evaluating risk factors for increased severity of COVID-19 illness, can inform public health guidance, improve ongoing COVID-19 risk stratification efforts, and encourage individuals with diabetes to continue engagement with diabetes self-management and health promoting behaviors. Future work must additionally account for factors that reflect the temporal and clinical course, as well as severity, of COVID-19 illness.

4.4. Conclusion

After controlling for HbA1c and concurrent hyperglycemia and acidosis in those with diabetes, T1D was the diabetes status associated with the highest risk for COVID-19-related hospitalization. Further research on modifiable risk factors is needed to develop tailored approaches for mitigating the likelihood and impact of severe COVID-19 illness in individuals with diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the T1D Exchange Publications Committee – especially Ruth Weinstock, MD, PhD (SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA) and Alissa Roberts, MD (Seattle Children’s, Seattle, WA, USA) – for their valuable feedback pertaining to this manuscript.

Funding source

EMT was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant number 5T32LM012410. This manuscript’s content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Data statement

The deidentified data that support the findings of this study are proprietary and are available from Cerner Corporation. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Upon publication, additional information pertaining to statistical methods, methods used to generate result summaries, and ancillary results will be provided upon request. This information will be shared with endocrinologists, health care professionals, data scientists, and informaticists who are interested in our analytical methods or who are conducting studies pertaining to hospitalization in individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Declaration of competing interest

MAC is the Chief Medical Officer at Glooko. He receives research support from Dexcom and Abbott Diabetes Care. NP receives research grant support from Dexcom through an investigator-initiated study. SP has been a contributing editor for diaTribe and has served on a medical advisory board for Medtronic MiniMed, Inc. Through the University of Colorado, she has received research funding from Dexcom, Inc., Eli Lilly, JDRF, the Leona M. & Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the National Institutes of Health, and Sanofi US Services. JML serves on a medical advisory board for GoodRx and serves as a consultant for Tandem Diabetes Care. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Erin M. Tallon: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing Osagie Ebekozien: Conceptualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing Janine Sanchez: Conceptualization, Writing-review and editing Vincent S. Staggs: Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing Diana Ferro: Conceptualization, Writing-review and editing Ryan McDonough: Writing-review and editing Carla Demeterco-Berggren: Writing-review and editing Sarit Polsky: Writing-review and editing Patricia Gomez: Writing-review and editing Neha Patel: Writing-review and editing Priya Prahalad: Writing-review and editing Ori Odugbesan: Writing-review and editing Priyanka Mathias: Writing-review and editing Joyce M. Lee: Writing-review and editing Chelsey Smith: Investigation Chi-Ren Shyu: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing-review and editing Mark A. Clements: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-review and editing

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ [Accessed: August 9, 2022]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk for severe COVID-19: Information for healthcare professionals. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html [Accessed: August 9, 2022] [PubMed]

- 3.Roncon L, Zuin M, Rigatelli G, et al. Diabetic patients with COVID-19 infection are at higher risk of ICU admission and poor short-term outcome. Journal of Clinical Virology 2020; 127. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BarroE, BakhaC, KaP, et al. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes and COVID-19 related mortality in England: A whole population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 8:813–822. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boye KS, Tokar Erdemir E, Zimmerman N, et al. Risk factors associated with COVID-19 hospitalization and mortality: A large claims-based analysis among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the United States. Diabetes Ther 2021; 12:2223–2239. DOI: 10.1007/s13300-021-01110-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kompaniyets L, Pennington AF, Goodman AB, et al. Underlying medical conditions and severe illness among 540,667 adults hospitalized with COVID-19, March 2020-March 2021. Prev Chronic Dis 2021; 18. DOI: 10.5888/pcd18.210123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dissanayake HA, De Silva NL, Sumanatilleke M, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic role of vitamin D in COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022; 107:1484–1502. DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgab892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sze S, Pan D, Nevill CR, et al. Ethnicity and clinical outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 29–30:100630. DOI: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackey K, Ayers C, Kondo K, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19-related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174:362–373. DOI: 10.7326/M20-6306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mude W, Oguoma VM, Nyanhanda T, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 pandemic cases, hospitalisations, and deaths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2021; 11:05015. DOI: 10.7189/jogh.11.05015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magesh S, John D, Li WT, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2134147. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanijahani A, Iezadi S, Gholipour K, et al. A systematic review of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in COVID-19. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20. DOI: 10.1186/s12939-021-01582-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raharja A, Tamara A, Kok LT. Association between ethnicity and severe COVID-19 disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2021; 8:1563–1572. DOI: 10.1007/s40615-020-00921-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehwerhemuepha L, Carlson K, Moog R, et al. Cerner real-world data (CRWD) - A de-identified multicenter electronic health records database. Data Brief 2022; 42:108120. DOI: 10.1016/j.dib.2022.108120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerner Corporation. Cerner Real-World Data (CRWD) 2020Q3 COVID database data dictionary. 2020.

- 16.Nichols G, Desai J, Lafata J, et al. Construction of a multisite DataLink using electronic health records for the identification, surveillance, prevention, and management of diabetes mellitus: The SUPREME-DM project. Prev Chronic Dis 2012; 9:E110. DOI: 10.5888/pcd9.110311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raebel MA, Schroeder EB, Goodrich G, et al. Mini-Sentinel statistical methods: Validating type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Mini-Sentinel Distributed Database using the SUrveillance, PREvention, and ManagEment of Diabetes Mellitus (SUPREME-DM) DataLink. Available from: https://www.sentinelinitiative.org/sites/default/files/Methods/Mini-Sentinel_Methods_Validating-Diabetes-Mellitus_MSDD_Using-SUPREME-DM-DataLink.pdf [Accessed: August 9, 2022]

- 18.Klompas M, Eggleston E, McVetta J, et al. Automated detection and classification of type 1 versus type 2 diabetes using electronic health record data. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:914–21. DOI: 10.2337/dc12-0964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Must A, Anderson SE. Body mass index in children and adolescents: Considerations for population-based applications. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006; 30:590–4. DOI: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Walraven C, Austin P, Jennings A, et al. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care 2009; 47:626–33. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005; 43:1130–9. DOI: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998; 36:8–27. DOI: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehwerhemuepha L, Gasperino G, Bischoff N, et al. HealtheDataLab – a cloud computing solution for data science and advanced analytics in healthcare with application to predicting multi-center pediatric readmissions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020; 20:115. DOI: 10.1186/s12911-020-01153-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011; 45:1–67. DOI: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. Approximations to the log-likelihood function in the nonlinear mixed-effects model. J Comput Graph Stat 1995; 4:12–35. DOI: 10.1080/10618600.1995.10474663 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. Accessed August 9, 2022. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470316696. DOI: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storey J. The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Ann Stat 2003; 31:2013–35. DOI: 10.2307/3448445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heald AH, Jenkins DA, Williams R, et al. The risk factors potentially influencing hospital admission in people with diabetes, following SARS-CoV-2 infection: A population-level analysis. Diabetes Ther 2022; 13:1007–1021. DOI: 10.1007/s13300-022-01230-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: A whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 8:813–822. DOI: 10.1016/s2213-8587(20)30272-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Hearn M, Liu J, Cudhea F, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 hospitalizations attributable to cardiometabolic conditions in the United States: A comparative risk assessment analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10. DOI: 10.1161/jaha.120.019259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kristófi R, Bodegard J, Norhammar A, et al. Cardiovascular and renal disease burden in type 1 compared with type 2 diabetes: A two-country nationwide observational study. Diabetes Care 2021; 44:1211–1218. DOI: 10.2337/dc20-2839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton S, Zollinger B, Freeman J, et al. Factors associated with clinical severity in emergency department patients presenting with symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2021; 2. DOI: 10.1002/emp2.12453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: Results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106:e936–e942. DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fresán U, Guevara M, Elía F, et al. Independent role of severe obesity as a risk factor for COVID‐19 hospitalization: A Spanish population‐based cohort study. Obesity 2021; 29:29–37. DOI: 10.1002/oby.23029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellini B, Cresci B, Cosentino C, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for hospitalization in COronaVirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) patients: Analysis of the Tuscany regional database. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2021; 31:769–773. DOI: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pereira M, Dantas Damascena A, Galvão Azevedo LM, et al. Vitamin D deficiency aggravates COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022; 62:1308–1316. DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1841090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.GhasemiaR, ShamshiriaA, HeydarK, et al. The role of vitamin D in the age of COVID‐19: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2021; 75:e14675. DOI: 10.1111/ijcp.14675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan T, Siuka D, Rotovnik NK, et al. COVID-19 and Vitamin D – A systematic review. Zdr Varst 2022; 61:124–132. DOI: 10.2478/sjph-2022-0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed AS, Alotaibi WS, Aldubayan MA, et al. Factors affecting the incidence, progression, and severity of COVID-19 in type 1 diabetes mellitus. BioMed Res Int 2021; 2021:1–9. DOI: 10.1155/2021/1676914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhatti JM, Raza SA, Shahid MO, et al. Association between glycemic control and the outcome in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Endocrine 2022. DOI: 10.1007/s12020-022-03078-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Clausen CL, Leo-Hansen C, Faurholt-Jepsen D, et al. Glucometabolic changes influence hospitalization and outcome in patients with COVID-19: An observational cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022; 187:109880. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sathish T, Cao Y. What is the role of admission HbA1c in managing COVID-19 patients? J Diabetes 2021; 13:273–275. DOI: 10.1111/1753-0407.13140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel AJ, Klek SP, Peragallo-Dittko V, et al. Correlation of hemoglobin A1c and outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Endocr Pract 2021; 27:1046–1051. DOI: 10.1016/j.eprac.2021.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Filippo L, Allora A, Doga M, et al. Vitamin D levels are associated with blood glucose and bmi in COVID-19 patients, predicting disease severity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022; 107:e348–e360. DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgab599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pietschmann P, Schernthaner G, Woloszczuk W. Serum osteocalcin levels in diabetes mellitus: Analysis of the type of diabetes and microvascular complications. Diabetologia 1988; 31:892–5. DOI: 10.1007/bf00265373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hough S, Fausto A, Sonn Y, et al. Vitamin D metabolism in the chronic streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Endocrinology 1983; 113:790–796. DOI: 10.1210/endo-113-2-790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 8:823–833. DOI: 10.1016/s2213-8587(20)30271-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sattar N, McInnes IB, McMurray JJV. Obesity is a risk factor for severe COVID-19 infection. Circulation 2020; 142:4–6. DOI: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.047659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Halpin DM, Rabe AP, Loke WJ, et al. Epidemiology, healthcare resource utilization, and mortality of asthma and COPD in COVID-19: A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Journal of Asthma and Allergy 2022; 15:811–25. DOI: 10.2147/jaa.s360985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.