Abstract

Importance:

Psychosis is a hypothesized consequence of cannabis use. Legalization of cannabis could therefore increase rates of healthcare utilization for psychosis.

Objective:

Evaluate the association of state medical and recreational cannabis laws and commercialization with rates of psychosis-related healthcare utilization.

Design:

Retrospective cohort design using state-level panel-fixed effects to model within-state changes in monthly rates of psychosis-related healthcare claims as a function of state cannabis policy level adjusting for time-varying state-level characteristics and state, year, and month fixed effects.

Setting:

Commercial and Medicare Advantage claims data in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia, 2003–2017

Participants:

63,680,589 beneficiaries aged ≥16 years

Main Outcomes & Measures:

State cannabis legalization policies were measured for each state and month based on law type (medical or recreational) and degree of commercialization (presence or absence of retail outlets). Outcomes were rates of psychosis-related diagnoses and prescribed antipsychotics.

Results:

This study included 63,680,589 beneficiaries followed for 2,015,189,706 person-months. Women comprised 51.8% of follow-up time with the majority of person-months recorded for those ≥65 years (77.3%) and among White beneficiaries (64.6%). Results from multivariate analysis showed no statistically significant increase in rates of psychosis-related diagnoses (medical, no retail outlets RR=1.13, 95% CI: 0.97–1.36; medical, retail outlets RR=1.24, 95% CI: 0.96–1.61; recreational, no retail outlets RR=1.38, 95% CI: 0.93–2.04; recreational, retail outlets RR=1.39, 95% CI: 0.98–1.97) or prescribed antipsychotics (medical, no retail outlets RR=1.00, 95%CI: 0.88–1.13; medical, retail outlets RR=1.01 95%CI: 0.87–1.19; recreational, no retail outlets RR=1.13, 95%CI: 0.84–1.51; recreational, retail outlets RR=1.14, 95%CI: 0.89–1.45) versus no policy. In exploratory secondary analyses, rates of psychosis-related diagnoses increased significantly among men, people aged 55–64, and Asian beneficiaries in states with recreational policies compared with no policy.

Conclusions & Relevance:

In this retrospective cohort study of commercial and Medicare Advantage claims data, state medical and recreational cannabis policies were not associated with a statistically significant increase in rates of psychosis-related health outcomes. As states continue to introduce new cannabis policies, continued evaluation of psychosis as a potential consequence of state cannabis legalization may be informative.

Introduction

Psychosis has long been investigated as a potential consequence of cannabis use. Among Swedish conscripts followed from 1969–1983, Andréasson and colleagues found a three-fold increased risk for schizophrenia associated with heavy cannabis use compared with non-users.1,2 An association between cannabis use and psychosis has since been demonstrated in numerous longitudinal studies.3-16 Findings from experimental research and GWAS and Mendelian randomization studies further support a causal link between cannabis use and schizophrenia.3,17-19 Whether cannabis plays an etiologic role in the onset of psychosis nevertheless remains a point of controversy.17,20

In the United States (U.S.) an estimated 48.2 million people ages 12 and older used cannabis at least once in 2019.21 As of June 2022, medical cannabis is legal in 38 states and 19 permit recreational use.22 With legalization, the price of cannabis has fallen substantially.23,24 Simultaneously, the average THC content of herbal cannabis in the U.S. increased markedly from 4% in 1996 to 17% in 2017.25-27 Past research on the impacts of cannabis legalization in the U.S. suggests a range of potential effects including decreased arrest rates,28 increased clearance rates for violent crimes,29 increased rates of cannabis use disorder,30,31 and increased rates of self-harm among men younger than 40 years.32 A limited number of studies have further identified increased rates of psychotic disorders associated with state and regional cannabis legalization in the US and with national policies in Canada and Portugal.33-36 As states continue to introduce cannabis legislation, a thorough and comprehensive understanding of their potential health effects is essential. Yet to our knowledge, no studies have examined trends in psychosis-related outcomes as a function of medical and recreational cannabis laws across all U.S. states.

We evaluate the association of state cannabis legalization with rates of psychosis-related healthcare claims among privately-insured individuals followed from 2003–2017. As the impacts of cannabis policies may depend on the provisions included,32,37 we define a measure of state cannabis policy that considers both medical and recreational laws and identifies whether states permitted commercial sales through retail outlets. We hypothesized a priori that rates of psychosis-related diagnoses and prescribed antipsychotics would be increased in states with recreational policies and in those permitting commercial sales. As the health effects of state cannabis policies may differ within populations,30-32 we considered rates of psychosis-related claims by gender, age, and race/ethnicity.

Methods

The Optum Clinformatics Data Mart Database is a de-identified commercial and Medicare Advantage claims database comprised of more than 63 million unique individuals followed from January 1, 2003–December 31, 2017. Study data included member enrollment data, diagnostic codes, and pharmacy claims deterministically linked across file types with a unique patient identifier. This study included all beneficiaries ages ≥16 years with at least one month of insurance eligibility during the study period.

In this retrospective cohort study, we leveraged a panel fixed-effects design—an extension of differences-in-differences—in which the state-month was the unit of analysis to evaluate the association of state cannabis policies with rates of psychosis-related healthcare claims.38 We counted the number of unique claims with psychosis-related diagnoses, prescribed antipsychotics, and enrolled individuals for each state -month of follow-up. These values were merged with a time-varying categorical measures of state cannabis policy level and state-level demographic, social, and economic characteristics. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University (Protocol #56615) and is reported per the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. The analysis plan was prepared and pre-registered in August 2021 (10.17605/OSF.IO/2PS64). Additions to the pre-registered plan are summarized in Appendix A (Supplemental Materials).

State cannabis policy level

Decriminalization removes criminal penalties for simple possession and use of cannabis. Past research suggest that decriminalization does not exert a sufficiently large effect on cannabis use rates to influence rates of psychotic disorders.39 This analysis therefore focuses on legalization, in which personal use; cultivation of cannabis; or its production, promotion, and sale is permitted.

As in prior research,32 we created a time-varying categorical variable reflecting the type of cannabis use permitted (medical or recreational) and whether retail outlets were open and operational. Cannabis legalization policies without retail outlets allowed only home-grown cannabis or had not yet implemented commercial sales.40 Data for recreational cannabis laws were derived from the Alcohol Policy Information System cannabis law database. Data for medical cannabis laws were derived from public research available through 2017.41 For each state- month, we assigned state cannabis policy levels as follows: no medical or recreational policy; medical only, no retail outlets; medical only, retail outlets; recreational, no retail outlets; or recreational, retail outlets. In all analyses, states with no medical or recreational policy (hereafter, “no policy”) served as the referent.

Psychosis-related claims

Claims with psychosis-related diagnoses (hereafter, “diagnoses”) were identified using codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10) and sub-classified as: non-affective psychoses; mood disorders with psychotic features; substance-related psychosis; and other psychosis (Supplemental Table 1). Prescribed antipsychotics were identified from outpatient pharmacy records and sub-classified as first- or second-generation (Supplemental Table 2). Prescriptions were standardized such that a 30-day supply counted as one prescription.

State-level characteristics

Time-varying state-level covariates included alcohol law stringency score42; the annual percentage of non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and Hispanic residents from the US Census (2002–2009) and American Community Survey (2010–2017); annual percent living in poverty and median income from the Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates Program; and monthly percent unemployed from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Files. We also included the count of all unique claims and prescriptions for each state-month as a measure of overall utilization.

Statistical analyses

We used panel fixed-effects to model rates of psychosis-related healthcare claims as a function of state cannabis policy level.43 We used generalized negative binomial regression as statistical testing of dispersion indicated it was appropriate than Poisson or quasi-Poisson. Counts of psychosis-related diagnoses and prescribed antipsychotics were the outcomes of interest. The number of eligible beneficiaries for each state-month was specified as the offset to estimate rate ratios (RRs).

All analyses included state fixed effects to account for potential confounding by time-invariant state characteristics. Calendar year fixed effects were included to address state-invariant secular trends including increased consumption of cannabis-containing product and potential discontinuities in psychosis-related claims introduced by the ICD transition. Month fixed effects were included to address potential seasonality in psychosis-related outcomes. We additionally adjusted for the above-described time-varying state-level characteristics lagged by one year to ensure temporal order. For all analyses, we calculated 95% confidence intervals (CI) with robust standard errors to account for repeated observations within states over time. Statistical inferences are presented based on alpha=0.05.

Secondary Analyses

We conducted subgroup analyses within strata defined by gender (men, women), age group (16–34; 35–54; 55–64; ≥65), gender and age group, categorical race/ethnicity (Asian, Black, Hispanic, White) as included in beneficiary enrollment files, and within subgroups of diagnoses and prescriptions. Secondary analyses were exploratory, and therefore we did not adjust for multiple comparisons consistent with expert recommendations.45

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted the following robustness checks: (1) we defined the sum of all unique claims and prescriptions for all health conditions as alternative offsets to account for changes in overall healthcare utilization; (2) we tested a six-category exposure that separated recreational cannabis policies into those with and without THC dose-related restrictions;46,47 (3) we tested a three-category exposure variable (no policy, medical policy, recreational policy); (4) we restricted to state-months with some form of cannabis policy (i.e., we excluded state-months that did not adopt any form of cannabis legalization over the study period, and set medical policies without retail outlets as the referent); (5) we conducted negative control analyses48 including use of the rate of all unique diagnoses and all unique prescriptions as negative control outcomes, hypothetical law changes at randomly assigned dates as a negative control exposure, and naloxone overdose prevention laws as a negative control exposure to assess potential residual confounding by factors that influence drug policy; (6) we implemented an alternative estimator proposed by Callaway and Sant’Anna that relaxes the typical assumption of panel fixed effects estimators that policy effects are constant over time and do not depend on the timing of legalization.49 (Appendix B in the Supplemental Materials).

Results

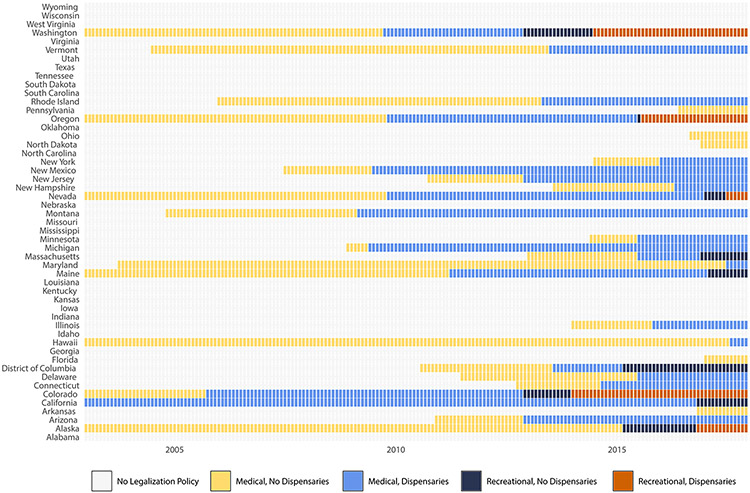

This study included 63,680,589 beneficiaries with 2,015,189,706 total person-months of follow-up. Women comprised 51.8% of follow-up time with 77.3% of person-months recorded among individuals ≤65 years and 64.6% among White beneficiaries. There were 7,503,907 psychosis-related diagnoses and 20,799,285 filled prescriptions for antipsychotics recorded over the study period. 29 states adopted medical or recreational cannabis legalization policies (Figure 1). Characteristics of the study population are presented in the Table. Additional state characteristics are summarized by state cannabis policy level in Supplemental Table 3.

Figure 1.

Classification of state cannabis policy level by state, 2003 – 2017. Reproduced from “Evaluation of state cannabis laws and rates of self-harm and assault” (Matthay et al. 2021)

Table.

Demographic characteristics, overall and by cannabis policy category

| Characteristic | Overall Person Months – N (%) |

No policy Person Months – N (%) |

Medical, no dispensaries Person Months – N (%) |

Medical, dispensaries Person Months – N (%) |

Recreational, no dispensaries Person Months – N (%) |

Recreational, dispensaries Person Months – N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2,015,189,706 (100) | 1,399,958,524 (100) | 172,068,754 (100) | 370,695,920 (100) | 33,285,610 (100) | 39,180,898 (100) |

| Gender 1 | ||||||

| Male | 971,559,233 (48.2) | 677,785,592 (48.4) | 82493727 (47.9) | 176523088 (47.6) | 15929852 (47.9) | 18,826,974 (48.1) |

| Female | 1,043,369,033 (51.8) | 722,034,469 (51.6) | 89476572 (52.0) | 194152594 (52.4) | 17353344 (52.1) | 20,352,054 (51.9) |

| Age | ||||||

| 16 – 34 years | 562,066,415 (27.9) | 407,088,387 (29.1) | 45,939,044 (26.7) | 92,461,530 (24.9) | 7,634,651 (22.9) | 8942803 (22.8) |

| 35 – 54 years | 706,946,119 (35.1) | 513,829,728 (36.7) | 58,630,415 (34.1) | 115,394,727 (31.1) | 8,715,647 (26.2) | 10,375,602 (26.5) |

| 55 – 64 years | 288,925,376 (14.3) | 207,888,251 (14.8) | 24,865,564 (14.5) | 47,130,674 (12.7) | 4,004,080 (12.0) | 5,036,807 (12.9) |

| 65 years and older | 457,251,796 (22.7) | 271,152,157 (19.4) | 42,633,731 (24.8) | 115,708,989 (31.2) | 12,931,233 (33.8) | 14,825,686 (37.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity 2 | ||||||

| Asian | 85,493,072 (4.2) | 41,409,520 (3.0) | 8,971,711 (5.2) | 30,394,285 (8.2) | 2,935,649 (8.8) | 1,781,906 (4.5) |

| Black | 179,175,433 (8.9) | 146,758,807 (10.5) | 16,495,701 (9.6) | 13,622,094 (3.7) | 1,356,582 (4.1) | 942,249 (2.4) |

| Hispanic | 214,962,576 (10.7) | 127,616,551 (9.1) | 15,420,561 (9.0) | 63,335,441 (17.1) | 5,060,718 (15.2) | 3,529,305 (9.0) |

| White | 1,301,673,039 (64.6) | 925,038,782 (66.1) | 112,700,157 (65.5) | 217,992,205 (58.8) | 18,656,900 (56.1) | 27,284,996 (69.6) |

| Diagnoses – N (%) 3 | 6,054,892 (100.0) | 4,034,704 (66.6) | 726,197 (12.0) | 974,921 (16.1) | 111,280 (1.8) | 207,790 (3.4) |

| Prescriptions – N (%) 4 | 20,406,581 (100.0) | 13,332,316 (65.3) | 1,958,949 (9.6) | 3,942,447 (19.3) | 443,613 (2.2) | 729,256 (3.6) |

Gender was unknown for 261,440 person-months of follow-up

Race/ethnicity was unknown for 233,885,586 person-months of follow-up

Depicts the total number of psychosis-related diagnoses overall and by cannabis policy category

Depicts the total number of filled prescriptions for antipsychotics overall and by cannabis policy category

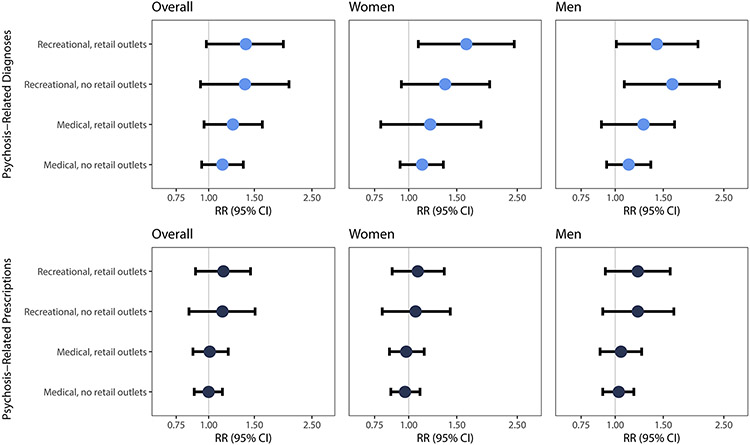

Crude rates were highest for state-months with recreational policies allowing retail outlets for both psychosis-related diagnoses (5.47 diagnoses per 1,000 person-months of follow-up, 95%CI: 5.45–5.49) and prescribed antipsychotics (19.22 prescriptions per 1,000 person-months of follow-up, 95%CI: 19.18–19.27) (Supplemental Table 4). Results from multivariate analysis showed no statistically significant increase in rates of psychosis-related diagnoses (medical, no retail outlets RR=1.13, 95% CI: 0.974–1.36; medical, with retail outlets RR=1.24, 95% CI: 0.96–1.61; recreational, no retail outlets RR=1.38, 95% CI: 0.93–2.04; recreational, with retail outlets RR=1.39, 95% CI: 0.98–1.97) or prescribed antipsychotics (medical, no retail outlets RR=1.00, 95%CI: 0.88–1.13; medical with retail outlets RR=1.01 95%CI: 0.87–1.19; recreational, no retail outlets RR=1.13, 95%CI: 0.84–1.51; recreational with retail outlets RR=1.14, 95%CI: 0.89–1.45) versus states with no policy (Figure 2, Supplemental Table 5).

Figure 2. Adjust results for rates of psychosis-related diagnoses and prescriptions by state cannabis policy level, 2003 – 2017.

Rate ratios were calculated using negative binomial models with person-months at risk as the offset. Models were adjusted for state-level confounders including percent non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic; percent unemployed and percent renting their home; median income; and the overall claims rate. We included fixed effects for state, year, and calendar month to address spatial and temporal autocorrelation. 95% CI were calculated with robust standard errors to account for repeated observations within states over time.

Secondary analyses

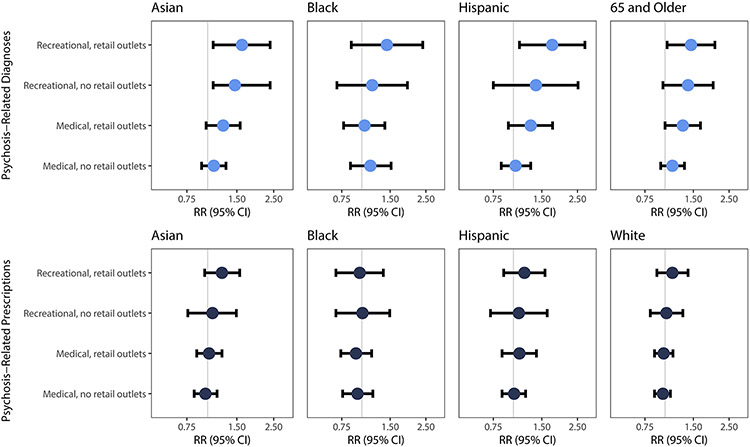

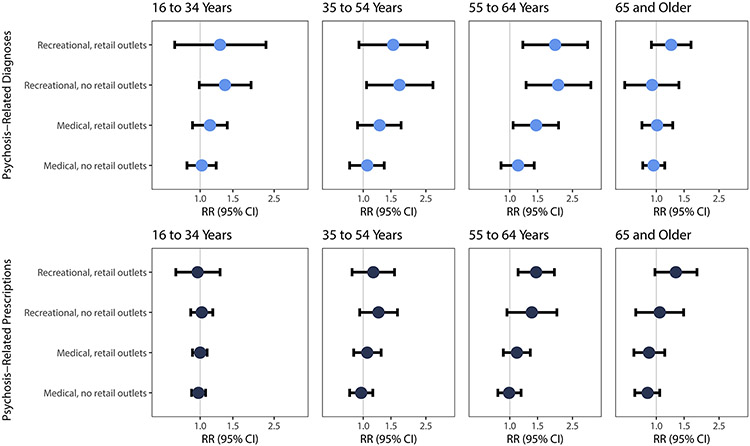

In exploratory secondary analyses, rates of psychosis-related diagnoses were increased in states with recreational policies as compared with no policy for men (medical, no retail outlets RR=1.12, 95%CI: 0.93–1.35; medical with retail outlets RR=1.27, 95%CI: 0.89–1.65; recreational, no retail outlets RR=1.62, 95%CI: 1.08–2.41; recreational with retail outlets RR=1.42, 95%CI: 1.01–2.01) among those ages 55–64 (medical, no retail outlets RR=1.13, 95%CI: 0.88–1.43; medical with retail outlets RR=1.47, 95%CI: 1.05–2.04; recreational, no retail outlets RR=2.03, 95%CI: 1.27–3.27; recreational with retail outlets RR=1.94, 95%CI: 1.21–3.12) and among Asian beneficiaries (medical, no retail outlets RR=1.09, 95%CI: 0.92–1.29; medical with retail outlets RR=1.24, 95%CI: 0.98–2.38; recreational, no retail outlets RR=1.46, 95%CI: 1.08–2.39; recreational with retail outlets RR=1.61, 95%CI: 1.08–2.38). We observed no statistically significant association with prescribed antipsychotics. (Figures 2-4; Supplemental Tables 6-9). Analysis by diagnostic subgroup and for first versus second generation antipsychotics were consistent with those of our primary analysis (Supplemental Tables 10-11).

Figure 4. Adjust results for rates of psychosis-related diagnoses and prescriptions at varying levels of cannabis commercialization by race/ethnicity, 2003 – 2017.

Rate ratios were calculated using negative binomial models with person-months at risk as the offset. Models were adjusted for state-level confounders including percent non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic; percent unemployed and percent renting their home; median income; and the overall claims rate. We included fixed effects for state, year, and calendar month to address spatial and temporal autocorrelation. 95% CI were calculated with robust standard errors to account for repeated observations within states over time. Because of sparsity of observations across covariate strata, for subgroup analysis among Asian beneficiaries we excluded observations from the four states with the fewest Asian beneficiaries (VT, SD, M, and AK) to calculate cluster robust standard errors (0.09% of follow-up time in this subgroup).

Sensitivity analyses

Results of sensitivity analyses were generally consistent with our main analyses with alternative offsets; three- and six-category exposure metrics; and when analysis was restricted to state-months with some form of cannabis policy in place (Supplemental Tables 12-15). Negative control analyses with unique diagnoses specified as the outcome of interest showed an inverse association for recreational policies with no retail outlets. We observed a dose-response pattern consistent with our primary analysis when unique prescriptions were specified as the outcome of interest (Supplemental Table 16). Negative control analyses with hypothetical law changes at randomly assigned dates showed no evidence of an association, as expected (Supplemental Table 17). We observed a small positive association when naloxone laws were assigned as the exposure of interest for both diagnoses (RR=1.18, 95%CI: 1.05–1.32) and prescriptions (RR=1.15, 95%CI: 1.07–1.25) (Supplemental Table 18). Using the Callaway and Sant’Anna estimator, we observed a pattern of positive associations for increasingly permissive state cannabis policies, consistent with our primary analysis (Supplemental Table 19).

Discussion

Psychotic disorders are known to cause considerable personal suffering and may impede an individual’s ability to complete their education, maintain employment, and otherwise function as expected in society.50 This study is the first and largest to quantify the association of medical and recreational cannabis policies with rates of psychosis-related healthcare claims across US states. We found that state medical and recreational cannabis policies were not associated with a statistically significant increase in rates of psychosis-related health outcomes. In exploratory secondary analyses, rates of psychosis-related diagnoses increased significantly among men, people aged 55-64, and Asian beneficiaries in states with recreational policies compared with no policy.

A limited number of prior studies studies have generally reported increased rates of psychosis-related health outcomes in association with state and local cannabis policies. In Colorado, Hall et al. analyzed administrative records from statewide emergency department (ED) visits following legalization of recreational cannabis from 2012–2014. They found a ninefold increase in the prevalence of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in cannabis-associated ED visits compared with visits unrelated to cannabis.33 Using cross-sectional data from the 2017 National Inpatient Sample, Moran et al. found that in the Pacific census division–where most states had introduced recreational cannabis policies by 2017–odds of psychosis-related hospitalization were higher than elsewhere in the US.34 Callaghan et al. found that ED presentations for cannabis-induced psychosis in Ontario and Alberta doubled between April 2015–December 2019 following legalization via the Cannabis Act on October 17, 2018.36 Finally, Gonçalves-Pinho et al. reported an increase in the percentage of patients with a psychotic disorder and increases in cannabis use prevalence from 0.87 to 10.6% in Portugal in the 15 years following decriminalization.35

Our analysis naturally extends the existing literature by leveraging prospectively recorded healthcare claims for the entire U.S. Whereas prior studies have focused on the effects of medical or recreational cannabis policies alone,30,31,33,34 Our analysis considers both medical and recreational policies and whether commercial sales were permitted.40 Cannabis commercialization is hypothesized to magnify cannabis use and related outcomes through reduced prices, widespread marketing, and expanded availability of high-potency cannabis-containing products.24,51 Prior studies have also demonstrated that associations depend on whether the policy permitted commercial sales.32,37

In contrast with these prior studies, we did not observe a statistically significant association of state cannabis policy level with overall rates of psychosis-related diagnoses or prescribed antipsychotics. Importantly, our outcome measures were comprised of psychosis-related diagnosis codes associated with healthcare delivery, and therefore do not capture episodes of psychosis among individuals who do not receive treatment. Because we cannot reliably distinguish new from existing psychotic disorders using administrative data, it is possible that state cannabis legalization has differential effects on incident versus prevalent psychosis that our results do not reflect. As states continue to introduce cannabis policies, the implications of state cannabis legalization for psychotic disorders warrants continued study, particularly in data settings where direct measures of disease onset and severity are available.

Finally, our analysis included exploratory subgroup analysis by gender, age, and race/ethnicity. Racial and ethnic disparities have been reported less frequently in the literature on cannabis and psychosis,23 but are an important area for future study given the potential for differences in social class, norms around mental illness, material resources, access to mental healthcare, and provider bias to create and perpetuate disparities. In analysis by gender and age, results were accentuated among men and among those ages 55–64 years. Past research identified heavy cannabis use in adolescence as a salient risk factor for onset of psychosis in young adulthood,52 but little research has examined middle-aged and older adults. However, age is a significant predictor of mental healthcare utilization, and middle-aged adults are generally more likely to receive services than those at the extremes of age.53 More broadly, findings by gender, age, and race/ethnicity underscore the importance of continued examination of heterogeneous effects of cannabis policies and the implications of these differences for health inequities.

Limitations

As psychotic disorders are associated with lower socioeconomic position,54 generalizability of our study findings is limited by our focus on insured individuals likely with fluctuating representativeness within states over the study period. We aimed to minimize confounding by controlling for state and time fixed effects and time-varying state-level characteristics, but residual confounding by factors associated with the broader policy environment such as expanded social safety net programs, rates of comorbid substance use, and preferential relocation by individuals predisposed to psychosis is possible. This is evidenced by the non-null association of naloxone access laws (designated as a negative control exposure) with psychosis-related diagnoses and prescribed antipsychotics.

The study period spans the period before and after the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed into law in 2010. We anticipate that potential confounding by passage of the ACA in our analysis is minimized. First, there is no clear evidence of an immediate effect of the ACA on state cannabis policy level as only two states (Delaware, New Jersey) and the District of Columbia introduced new state cannabis policy shortly after passage of the ACA. Second, our analysis includes fixed effects for calendar year. This means that any changes that applied to all state at the same time are controlled by design with these fixed effects. If there is residual confounding due to the ACA, it would be because the influence of the ACA differs in a time-varying and state-specific way

We did not adjust for multiple comparisons in exploratory secondary analyses. Although Bonferroni correction may have desirable properties when the sample size is large and a moderate number of tests are performed, we note the effective sample size in our analysis is much smaller than the number of claims because the unit of analysis is the state-month. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the potential risk of Type I Error (i.e., false positive results) without correction for multiple comparisons.55,56 Finally, several unexpected secondary findings are not easily explained and warrant further consideration. These include the minimal association with recreational cannabis policies that permit retail outlets but make no THC dose-related restrictions, and the dose-response association between cannabis policy level and overall rates of prescriptions. Future analyses should explore systematic differences in state-level factors including prescribing patterns that may be correlated with cannabis policies.

Conclusions

In this retrospective cohort study of commercial and Medicare Advantage claims data, state medical and recreational cannabis policies were not associated with a statistically significant increase in rates of psychosis-related health outcomes. As U.S. states continue to legalize the use, production, promotion, or sale of cannabis, continued examination of the implications of state cannabis policies for psychotic disorders may be informative, particularly with study designs that yield precise estimates in high-risk population subgroups.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3. Adjust results for rates of psychosis-related diagnoses and prescriptions by state cannabis policy level by age group, 2003 – 2017.

Rate ratios were calculated using negative binomial models with person-months at risk as the offset. Models were adjusted for state-level confounders including percent non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic; percent unemployed and percent renting their home; median income; and the overall claims rate. We included fixed effects for state, year, and calendar month to address spatial and temporal autocorrelation. 95% CI were calculated with robust standard errors to account for repeated observations within states over time.

KEY POINTS.

Question:

Is state cannabis legalization or commercialization associated with increased rates of psychosis-related healthcare claims?

Findings:

In this panel fixed effects analysis of claims data from 63,680,589 beneficiaries from 2003–2017, there was no statistically significant difference in the rates of psychosis-related diagnoses or prescribed antipsychotics in states with medical or recreational cannabis policies as compared to states with no such policy.

Meaning:

State cannabis policy level was not associated with a statistically significant difference in rates of psychosis-related outcomes. As states continue to introduce new cannabis policies, ongoing evaluation of psychosis as a potential consequence of state cannabis legalization may be informative.

Acknowledgements:

Data for this project were accessed using the Stanford Center for Population Health Sciences Data Core. H.E. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. E.C.M was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) R00AA028256 and M.V.K was supported by the National Institutes on Drug Abuse R00DA051534. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Andréasson S, Engström A, Allebeck P, Rydberg U. Cannabis and schizophrenia a longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. The Lancet. 1987;330(8574):1483–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zammit S, Allebeck P, Andreasson S, Lundberg I, Lewis G. Self reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort study. Bmj. 2002;325(7374):1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arseneault L, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray RM. Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. The British journal of psychiatry. 2004;184(2):110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Os J, Bak M, Hanssen M, Bijl R, De Graaf R, Verdoux H. Cannabis use and psychosis: a longitudinal population-based study. American journal of epidemiology. 2002;156(4):319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiser M, Knobler HY, Noy S, Kaplan Z. Clinical characteristics of adolescents later hospitalized for schizophrenia. American journal of medical genetics. 2002;114(8):949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fergusson DM, Horwood L, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms in young people. Psychological medicine. 2003;33(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferdinand RF, Sondeijker F, Van Der Ende J, Selten JP, Huizink A, Verhulst FC. Cannabis use predicts future psychotic symptoms, and vice versa. Addiction. 2005;100(5):612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henquet C, Krabbendam L, Spauwen J, et al. Prospective cohort study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people. Bmj. 2004;330(7481):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manrique-Garcia E, Zammit S, Dalman C, Hemmingsson T, Andreasson S, Allebeck P. Cannabis, schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses: 35 years of follow-up of a population-based cohort. Psychological medicine. 2012;42(6):1321–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rognli EB, Berge J, Håkansson A, Bramness JG. Long-term risk factors for substance-induced and primary psychosis after release from prison. A longitudinal study of substance users. Schizophrenia research. 2015;168(1-2):185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tien AY, Anthony JC. Epidemiological analysis of alcohol and drug use as risk factors for psychotic experiences. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bechtold J, Hipwell A, Lewis DA, Loeber R, Pardini D. Concurrent and sustained cumulative effects of adolescent marijuana use on subclinical psychotic symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):781–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiles NJ, Zammit S, Bebbington P, Singleton N, Meltzer H, Lewis G. Self-reported psychotic symptoms in the general population: results from the longitudinal study of the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188(6):519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rössler W, Hengartner MP, Angst J, Ajdacic-Gross V. Linking substance use with symptoms of subclinical psychosis in a community cohort over 30 years. Addiction. 2012;107(6):1174–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gage S, Hickman M, Heron J, et al. Associations of cannabis and cigarette use with psychotic experiences at age 18: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Psychological medicine. 2014;44(16):3435–3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livne O, Shmulewitz D, Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Hasin DS. Association of cannabis use–related predictor variables and self-reported psychotic disorders: US adults, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. American journal of psychiatry. 2022;179(1):36–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gage SH, Hickman M, Zammit S. Association between cannabis and psychosis: epidemiologic evidence. Biological psychiatry. 2016;79(7):549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Souza DC, Perry E, MacDougall L, et al. The psychotomimetic effects of intravenous delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy individuals: implications for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(8):1558–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasman JA, Verweij KJ, Gerring Z, et al. GWAS of lifetime cannabis use reveals new risk loci, genetic overlap with psychiatric traits, and a causal effect of schizophrenia liability. Nature neuroscience. 2018;21(9):1161–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leyton M Cannabis legalization: Did we make a mistake? Update 2019. In. Vol 44: Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience; 2019:291–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahrnsbrak R, Bose J, Hedden SL, Lipari RN, Park-Lee E. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2017;1572. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Conference of State Legislatures. State medical cannabis laws. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. Published 2022. Accessed February 15, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasin DS. US epidemiology of cannabis use and associated problems. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall W, Stjepanović D, Caulkins J, et al. Public health implications of legalising the production and sale of cannabis for medicinal and recreational use. The Lancet. 2019;394(10208):1580–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, Church JC, Freeman TP, ElSohly MA. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008–2017). European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2019;269(1):5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehmedic Z, Chandra S, Slade D, et al. Potency trends of Δ9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated cannabis preparations from 1993 to 2008. Journal of forensic sciences. 2010;55(5):1209–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ElSohly MA, Ross SA, Mehmedic Z, Arafat R, Yi B, Banahan BF. Potency trends of Δ 9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated marijuana from 1980–1997. Journal of Forensic Science. 2000;45(1):24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plunk AD, Peglow SL, Harrell PT, Grucza RA. Youth and adult arrests for cannabis possession after decriminalization and legalization of cannabis. JAMA pediatrics. 2019;173(8):763–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu G, Li Y, Lang XE. Effects of recreational marijuana legalization on clearance rates for violent crimes: Evidence from Oregon. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2022;100:103528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cerdá M, Mauro C, Hamilton A, et al. Association between recreational marijuana legalization in the United States and changes in marijuana use and cannabis use disorder from 2008 to 2016. JAMA psychiatry. 2020;77(2):165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerdá M, et al. US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws: 1991-1992 to 2012-2013. JAMA psychiatry. 2017;74(6):579–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthay EC, Kiang MV, Elser H, Schmidt L, Humphreys K. Evaluation of state cannabis laws and rates of self-harm and assault. JAMA network open. 2021;4(3):e211955–e211955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall KE, Monte AA, Chang T, et al. Mental health–related emergency department visits associated with cannabis in Colorado. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2018;25(5):526–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moran LV, Tsang ES, Ongur D, Hsu J, Choi MY. Geographical variation in hospitalization for psychosis associated with cannabis use and cannabis legalization in the United States: Submit to: Psychiatry Research. Psychiatry research. 2022:114387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonçalves-Pinho M, Bragança M, Freitas A. Psychotic disorders hospitalizations associated with cannabis abuse or dependence: A nationwide big data analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2020;29(1):e1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Callaghan RC, Sanches M, Murray RM, Konefal S, Maloney-Hall B, Kish SJ. Associations Between Canada's Cannabis Legalization and Emergency Department Presentations for Transient Cannabis-Induced Psychosis and Schizophrenia Conditions: Ontario and Alberta, 2015–2019. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2022:07067437211070650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Assessing the effects of medical marijuana laws on marijuana use: the devil is in the details. Journal of policy analysis and management. 2015;34(1):7–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angrist JD, Pischke J-S. Chapter 5: Parallel worlds: Fixed effects, differences-in-differences, and panel data. In: Mostly harmless econometrics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2009:221–248. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babor TF, Caulkins JP, Edwards G, et al. Drug policy and the public good. In:2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray RM, Hall W. Will legalization and commercialization of cannabis use increase the incidence and prevalence of psychosis? JAMA psychiatry. 2020;77(8):777–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powell D, Pacula RL, Jacobson M. Do medical marijuana laws reduce addictions and deaths related to pain killers? Journal of health economics. 2018;58:29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanchette JG, Lira MC, Heeren TC, Naimi TS. Alcohol policies in US states, 1999–2018. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2020;81(1):58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angrist JD, Pischke J-S. Parallel worlds: fixed effects, differences-in-differences, and panel data. In: Mostly harmless econometrics. Princeton University Press; 2008:221–248. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, et al. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. European journal of epidemiology. 2016;31(4):337–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alcohol Policy Information System. Recreational use of cannabis: volume 1: data on a specific date. https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/cannabis-policy-topics/recreational-use-of-cannabis-volume-1/104. Accessed April 1, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alcohol Policy Information System. Recreational use of cannabis: volume 2: data on a sepcific date. . https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/cannabis-policy-topics/recreational-use-of-cannabis-volume-2/105. Accessed April 1, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lipsitch M, Tchetgen ET, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 2010;21(3):383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Callaway B, Sant’Anna PH. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics. 2021;225(2):200–230. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bruce ML, Raue PJ. Mental illness as psychiatric disorder. In: Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Springer; 2013:41–59. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Humphreys K, Shover CL. Recreational cannabis legalization presents an opportunity to reduce the harms of the US medical cannabis industry. World psychiatry. 2020;19(2):191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones HJ, Gage SH, Heron J, et al. Association of combined patterns of tobacco and cannabis use in adolescence with psychotic experiences. JAMA psychiatry. 2018;75(3):240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. The Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eaton WW Jr. Residence, social class, and schizophrenia. Journal of health and social behavior. 1974:289–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burke JF, Sussman JB, Kent DM, Hayward RA. Three simple rules to ensure reasonably credible subgroup analyses. Bmj. 2015;351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.VanderWeele TJ, Mathur MB. Some desirable properties of the Bonferroni correction: is the Bonferroni correction really so bad? American journal of epidemiology. 2019;188(3):617–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.