Abstract

It is well documented that ethanol exposure alters GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)-releasing synapses, and ethanol addiction is associated with endogenous opioid system. Emerging evidence indicates that opioids block long-term potentiation in the fast inhibitory GABAA receptor synapses (LTPGABA) onto dopamine-containing neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a brain region essential for reward-seeking behavior. However, how ethanol affects LTPGABA is not known. We report here that in acute midbrain slices from rats, clinically relevant concentrations of ethanol applied both in vitro and in vivo prevents LTPGABA, which is reversed respectively by in vitro and in vivo administration of naloxone, a μ opioid receptor (MOR) antagonist. Furthermore, the blockade of LTPGABA induced by a brief in vitro ethanol treatment is mimicked by DAMGO ([D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin), a MOR agonist. Pared-pulse ratios are similar in slices 24 hours after in vivo injection with either saline or ethanol. Sp-cAMPS, a stable cAMP analog, and pCPT-cGMP, a cGMP analogue potentiates GABAA-mediated IPSCs in slices from ethanol treated rats, indicating that a single in vivo ethanol exposure does not maximally increase GABA release; instead, ethanol produces a long-lasting inability to generate LTPGABA. These neuroadaptations to ethanol might contribute to early stage of addiction.

Keywords: mesolimbic system, addiction, alcohol, long term potentiation, GABA

INTRODUCTION

Addiction is caused, in part, by powerful and long-lasting memories of the drug experience, and the long-term changes in chemical synaptic action in response to drug administration are believed to be candidate mechanisms (Hyman and Malenka, 2001; Hyman et al., 2006; Kauer and Malenka, 2007). It has been well documented that exposure to abused drugs can induce long-term changes in excitatory synapses. Emerging evidence indicates that exposure to opioids, via activation of μ-opioid receptors (MORs) also induced long-term changes in inhibitory GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)-releasing synapses (LTPGABA) on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a brain region critical for reward and drug abuse (Nugent et al., 2007). The MORs in VTA are mostly expressed in GABAergic neurons (Mansour et al., 1995; Steffensen et al., 1998; Garzon and Pickel, 2001). Activation of MORs hyperpolarizes and inhibits VTA GABAergic neurons (Di Chiara and North, 1992; Johnson and North, 1992b; Margolis et al., 2003).

Recent electrophysiological evidence indicates that both in vivo and in vitro exposure to ethanol profoundly altered GABAergic transmission to dopamine neurons in the VTA (Gallegos et al., 1999; Melis et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2007b; Theile et al., 2008; Xiao and Ye, 2008; Theile et al., 2009). Several lines of evidence indicate that ethanol's action on neurons in the VTA involves MORs. Ethanol enhances the release of β-endorphin, which activates MORs in the VTA and several other brain regions (Stein, 1993; Herz, 1997; Mendez et al., 2003; Marinelli et al., 2004; Lam et al., 2008; Jarjour et al., 2009). Selective MOR antagonists reduce ethanol consumption (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2000; Hyytia and Kiianmaa, 2001; Margolis et al., 2008). Naloxone, a MOR antagonist strongly attenuated ethanol-induced inhibition of VTA GABAergic neurons and ethanol-induced excitation of VTA dopamine neurons (Xiao et al., 2007b; Xiao and Ye, 2008). However, there are no studies directly examining ethanol's effects on LTPGABA. The objective of current study was to determine whether in vitro and in vivo exposure to ethanol affects LTPGABA on dopamine neurons in the VTA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and they were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (Newark, NJ). The experiments were done on Sprague-Dawley rats.

Slice Preparation

The midbrain slices were prepared as described previously (Xiao and Ye, 2008). Briefly, Sprague–Dawley rats (21–35 days old) were anesthetized and then decapitated. Coronal midbrain slices (200–250 μm thick) were cut using a VF-200 slicer (Precisionary Instruments Inc., Greenville, NC). They were prepared in an ice-cold glycerol-based artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 250 mM glycerol, 1.6 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3, and 11 mM glucose, and saturated with 95%O2/5%CO2 (carbogen) (Ye et al., 2006). Slices were allowed to recover for at least 1 hour in a holding chamber at 32°C in carbogen-saturated regular ACSF, which has the same composition as glycerol-based ACSF, except that glycerol was replaced by 125 mM NaCl.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Electrical signals were obtained in whole-cell configurations with a MultiClamp 700A (Molecular Devices Co., Union City, CA), a Digidata 1320A A/D converter (Molecular Devices Co.), and pCLAMP 9.2 software (Molecular Devices Co.). The patch electrodes had a resistance of 2–5 MΩ when filled with the pipette solution containing: 125 mM KCl, 2.8 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM EGTA, 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM ATP-Na, and 0.3 mM GTP-Na. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with Tris base and osmolarity to 300 mOsmol/L with sucrose. A single slice was transferred into a 0.4 ml recording chamber where it was held down by a platinum ring. Warm carbogenated ACSF flowed through the bath (1.5–2.0 ml/min). All recordings were made at 32°C, maintained by an automatic temperature controller (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT).

Under infrared video microscopy (E600FN; Nikon, Japan), the VTA was identified medial to the accessory optic tract and lateral to the fasciculus retroflexus. Currents were recorded using whole-cell mode. Experiments were begun only after series resistance had stabilized. Series resistance and input resistance were monitored continuously on-line with a −4 mV hyperpolarizing step (50 ms), which was given following every afferent stimulus, and experiments were discarded if these values changed by 20% during the experiment. Dopamine neurons were identified by the presence of a large Ih current (Johnson and North, 1992) that was assayed immediately after break-in, using a series of incremental 10 mV hyperpolarizing steps from a holding potential of −50 mV. Specifically, if the steady-state h-current was greater than 60 pA during a step from −50 to −100 mV, the neuron was considered a dopamine neuron. A recent study showed that expression of Ih alone is not sufficient to identify dopamine cells unequivocally (Margolis et al., 2006) but see the review by (Chen et al., 2008). Therefore, in each set of our experiments, a subset of the neurons recorded from and reported here are possibly non-dopaminergic neurons (Nugent et al., 2009).

GABAergic IPSCs were recorded from the dopamine neurons in the presence of 6, 7-dinitroquinoxaline -2,3-dione (DNQX, 10 μM), an AMPA receptor antagonist. Neurons were voltage-clamped at a membrane potential of −70 mV except where noted. GABAAR-mediated IPSCs were stimulated at 0.1 Hz using a bipolar stainless steel stimulating electrode placed 200–400 μm away from the recording site in VTA. LTPGABA was induced by stimulating afferents at 100 Hz for 1 s, the train was repeated twice 20 s apart (high-frequency stimulation; HFS). After recording the baseline currents, during the drug application and washout, synaptic stimulation was stopped and the recorded neuron was taken from voltage-clamp into bridge mode. The HFS trains were also delivered under bridge mode.

Data were filtered at 1 kHz, sampled at 5 kHz, collected on line using pCLAMP 9.2 software (Molecular Devices Co.), stored on a computer and analyzed off-line. The amplitudes of IPSCs were calculated by taking the mean of a 2–4 ms window around the peak and comparing this with the mean of a 2–8 ms window immediately before the stimulation artifact, using Clampfit 9.2 software (Molecular Devices).

Chemicals and Applications

Drugs were added to the superfusate at final concentrations. Most of the chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Ethanol (95% v/v, prepared from grain and stored in glass bottles) was from Pharmco products INC (Brookfield, CT). Ethanol and other chemicals were applied to the recorded neurons at the stated concentrations through bath perfusion.

Data Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Significance was determined using a Student's unpaired t-test with significance level of P < 0.05. Levels of LTP are reported as averaged IPSC amplitudes for 5 min just before LTP induction compared with averaged IPSC amplitudes during the 5 min period from 20 to 25 min after HFS using a Student's t-test. Paired-pulse ratios (50 ms inter-stimulus interval) were measured over 5 min epochs of 30 IPSCs each as previously described (Ye et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2007a).

In vivo ethanol treatment

Rats (21–35 days old) were maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle and provided food and water ad libitum. For the groups receiving in vivo treatments, rats were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with either 2g/kg ethanol or a comparable volume of saline, placed in a new cage for 2 hours, and then returned to the home cage. They were sacrificed for brain slice preparation 24 hours after injection.

RESULTS

In vitro exposure to ethanol blocks LTPGABA in VTA dopamine neurons via activation of μ-opioid receptors (MORs)

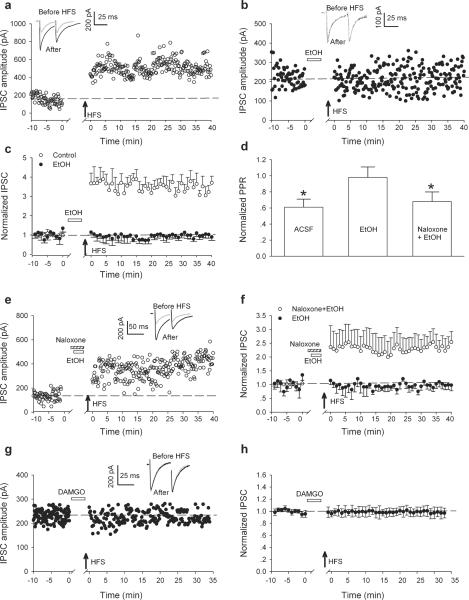

Evoked inhibitory postsynaptic current (IPSCs) were recorded from VTA dopamine neurons in midbrain slices in the presence of DNQX (6,7-Dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione; 10 μM) at a holding potential of −70 mV. The IPSCs recorded under these experimental conditions were blocked by 10 μM gabazine, a GABAA receptor antagonist (not illustrated), indicating that they were mediated by GABAA receptors. Consistent with previous reports (Nugent et al., 2007; Nugent et al., 2009), high-frequency electrical stimulation (HFS) induced long-term potentiation of IPSC (LTPGABA, Fig.1a). LTPGABA was associated with a decrease in the paired-pulse ratio (PPR, Fig. 1a, insets), suggesting that LTPGABA is maintained by persistently increased GABA release, which is probably caused by high-frequency firing of the presynaptic GABAergic afferents (Nugent et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

In vitro exposure to ethanol blocks LTPGABA in VTA dopamine neurons involving μ-opioid receptors. (a) LTPGABA in a dopamine neuron using whole-cell recording methods. High frequency stimulation (HFS) was delivered at the arrow. Inset: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after HFS (black). In this and all figures, ten consecutive IPSCs from each condition were averaged for illustration. The dashed line in this and other figures is an extrapolation of the mean response before HFS. (b) Bath-applied ethanol blocks LTPGABA. After recording the baseline IPSCs in normal ACSF for 10 min, ethanol (EtOH, 40 mM) was bath-applied for 15 min and then washout (for 6 min) before the delivery of HFS. Inset: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after HFS (black). (c) Average of 11 experiments from dopamine neurons (Control LTPGABA, open circles; ethanol cells, filled circles). (d) Normalized PPR at 20 min after HFS under a variety of experimental conditions. The PPR at 20 min was normalized to the pre-HFS PPR values. (* P < 0.05, Student t test for PPR after-HFS compared with pre-HFS values). (e) Bath-applied naloxone blocked the inhibition of LTPGABA induced by bath-applied EtOH. After recording the baseline IPSCs in normal ACSF for 10 min, naloxone (5 μM) was bath applied for 5 min before the application of the mixture containing naloxone (5 μM) and ethanol (40 mM) for 15 min. HFS was delivered 6 min after washout of the mixture (at the arrow). Inset: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after HFS (black). (g) Bath-applied DAMGO blocks LTPGABA. After recording the baseline IPSCs in normal ACSF for 10 min, DAMGO (1 μM) was bath-applied for 15 min and then washout (for 6 min) before the delivery of HFS. Inset: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after HFS (black). (h) Average of 6 experiments from dopamine neurons.

We then examined the effects of ethanol on LTPGABA. Ethanol at a pharmacological relevant concentration (40 mM) was bath applied for 15 min, and then washed out for 6 min, which was followed with HFS. HFS failed to induce LTPGABA under such experimental conditions (Fig. 1b, c). In 11 experiments, in the absence of ethanol, the averaged peak amplitude of IPSC (IPSC1) elicited by the first stimulus of the paired pulse measured 20–25 min after HFS was 347 ± 57% of pre-HFS values (Fig. 1c, open circles). After brief in vitro exposure to ethanol, it was 99 ± 13% of pre-HFS values (Fig. 1c, filled circles). Ethanol also reversed the changes in PPR (in ACSF, PPR = 0.61 ± 0.10 of pre-HFS values: from 1.17 ± 0.13 in baseline to 0.71 ± 0.14 after HFS; P < 0.05; in ethanol, PPR = 0.98 ± 0.13 of pre-HFS values: from 1.23 ± 0.14 in baseline to 1.20 ± 0.13 after HFS, P > 0.05; Fig. 1d). As mentioned, much evidence links ethanol's effect on VTA neurons with MORs. To determine whether activation of MORs during ethanol exposure contributes to ethanol–induced blockade of LTPGABA, naloxone (5 μM), a MOR competitive antagonist, was bath-applied for 5 min before the application of the mixture containing naloxone (5 μM) and ethanol (40 mM) for 15 min. HFS was delivered 6 min after washout of the mixture. Under these experimental conditions, the cells exhibited normal LTPGABA (Fig. 1e). In 9 experiments, the averaged peak amplitude of IPSC1 measured 20–25 min after HFS was 219 ± 66% of pre-HFS values in cells exposure to ethanol plus naloxone (Fig. 1f, open circles) verses 92 ± 35% of pre-HFS values in ethanol alone (filled circles, Fig. 1f). The PPR was 0.68 ± 0.12 of pre-HFS values (from 1.22 ± 0.14 in baseline to 0.83 ± 0.12 after HFS) in cells exposure to ethanol plus naloxone. In further tests of the involvement of MORs, we applied the MOR agonist DAMGO ([D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin) (1 μM) to the bath for 15 min. HFS was delivered 6 min after washout of the DAMGO solution. Under these experimental conditions, HFS failed to induce LTPGABA, consistent with a previous report (Nugent et al., 2007) (Fig. 1g). In six experiments, the averaged peak amplitude of IPSC1 measured 20–25 min after HFS was 102 ± 11 % of pre-HFS values in cells exposure to DAMGO (Fig. 1h). Together, these results provide strong support for the idea that ethanol suppresses LTPGABA was mediated by MORs at the level of the presynaptic terminals.

In vivo exposure to ethanol blocks LTPGABA in VTA dopamine neurons via activation of MORs

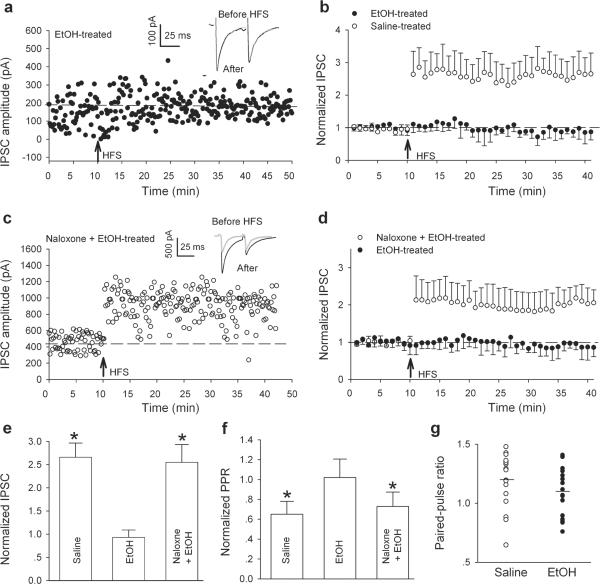

A single in vivo ethanol exposure induced a long lasting potentiation of VTA GABAergic synapses in VTA dopamine neurons of mice (Melis et al., 2002). We therefore asked whether in vivo exposure to ethanol also alters LTPGABA of rats. Sprague–Dawley rats (21–35 days old) were treated with either ethanol (2 g/kg intraperitoneal injection, i.p.) or saline (i.p.). After HFS in slices 24 hours after ethanol injections, there was no LTPGABA (Fig. 2a). In 14 experiments, the averaged peak amplitude of IPSC1 was 93 ± 21% of pre-HFS values (Fig. 2b, filled circles, Fig. 2e, EtOH, P > 0.05 compared with pre-HFS values) and PPR was 1.02 ± 0.18 of pre-HFS values (from 1.04 ± 0.16 in baseline to 1.06 ± 0.1 after HFS, Fig. 2f, EtOH, P > 0.05, compared with pre-HFS values. Conversely, slices from saline-treated animals exhibited normal LTPGABA. In six experiments, the averaged peak amplitude of IPSC1 was 266 ± 35% of pre-HFS values (Fig. 2b, open circles, Fig. 2e, saline), and PPR was 0.65 ± 0.13 of pre-HFS values (from 1.20 ± 0.09 in baseline to 0.78 ± 0.11 after HFS, P < 0.05, Fig. 2f, saline). Interestingly, the basal IPSCs from ethanol and saline-treated rats had indistinguishable PPR values (1.20 ± 0.05 in saline treated verses 1.09 ± 0.05 in EtOH treated, P = 0.14, Fig. 2g). These data provide direct evidence that inhibitory synapses in the VTA dopamine neurons can no longer be potentiated by HFS 24 hours after a single in vivo exposure to ethanol.

Figure 2.

In vivo exposure to ethanol blocks LTPGABA involving the activation of MORs. (a) LTPGABA was blocked in a dopamine neurons in slices prepared 24 hour after a single in vivo ethanol exposure. Insets: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after HFS (black). (b) Average of 6 experiments from slices prepared 24 hours after either saline (open circles) or ethanol (filled circles). (c) In vivo exposure to naloxone prevents in vivo ethanol-induced blockade of LTPGABA in slices prepared 24 hours later. Insets: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after HFS (black). (d) Average of 6 experiments from slices prepared 24 hours after ethanol (filled circles) or naloxone + ethanol (open circles) injection. (e) Bar chart illustrating the magnitude of LTPGABA 20 min after HFS in various experimental conditions (*P < 0.05 compared with pre-HFS values). (f) Normalized PPR under variety experimental conditions (* P < 0.05 compared with pre-HFS values). (g) Paired-pulse ratios are similar in slices 24 hours after in vivo injection with either saline (open circles, n = 14) or ethanol (filled circles, n = 14). Each symbol represents the paired-pulse ratio value for one animal (mean basal paired-pulse ratio values (black horizontal bars) from saline-treated rats: 1.20 ± 0.05, n =14; ethanol-treated rats: 1.09 ± 0.05, n = 14, P = 0.14).

We then tested the effects of naloxone, a MOR antagonist. Naloxone (10 mg/kg, i.p.) was injected 15 min before ethanol (2g/kg, i.p). After HFS in slices cut 24 hours after naloxone plus ethanol treatment, the cells exhibited normal LTPGABA (Fig. 2c). In nine experiments, the averaged peak amplitude of IPSC1 was 188 ± 36% of pre-HFS values, and PPR was 0.73 ± 0.13 of pre-HFS values (from 1.11 ± 0.21 in baseline to 0.81 ± 0.16 after HFS, P < 0.05; Fig. 2d, e, f, Naloxone + EtOH-treated). This result suggests that in vivo ethanol-induced suppression of LTPGABA was also mediated by MORs.

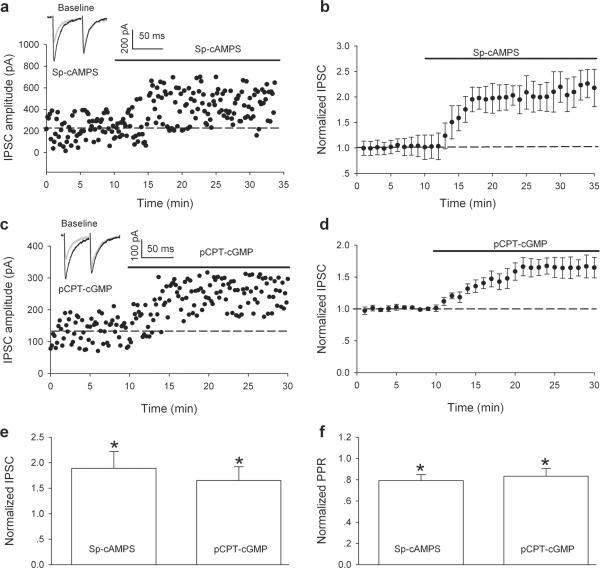

Sp-cAMPS and pCPT-cGMP potentiate GABAA-mediated IPSCs in slices from ethanol treated rats

As mentioned, a single in vivo ethanol treatment significantly increases GABA release onto VTA dopamine neurons in slices of mice cut 24 hours later (Melis et al., 2002). Thus, the failure of HFS to induce LTPGABA in slices prepared 24 hours after in vivo ethanol treatment might be due to saturation of GABAergic synapses, a ceiling effect, which precludes further potentiation. To test this possibility, we examined the effects of Sp-cAMPS, a stable cAMP analog, which has been shown to increase GABAergic IPSCs in many different preparations, including the VTA (Bonci and Williams, 1997). Ethanol (2 g/kg, i.p.) was injected in rats and the brain slices were prepared 24 hours later. In 16 experiments, bath-applied Sp-cAMPS (20 μM) further significantly increased the peak amplitude of IPSC1 (189 ± 33% of pre-drug value; P < 0.05) measured 20 min after application of Sp-cAMPS (Fig. 3 a, b, e). This was accompanied by a reduction of PPR (79 ± 6% of pre-drug level, from 1.12 ± 0.11 in pre-drug to 0.89 ± 0.08 in SP-cAMPS, P < 0.05, Fig. 3a, insets; f, Sp-cAMPS). These data indicate that Sp-cAMPS act on the presynaptic site increasing GABA release, and that in vivo ethanol exposure did not maximally increase GABA release; instead, ethanol produced a long-lasting inability to generate LTPGABA.

Figure 3.

Sp-cAMPS, and pCPT-cGMP further potentiate GABAergic IPSCs in slices prepared 24 hours after in vivo ethanol treatment (2g/kg, i.p.). (a) Bath-applied Sp-cAMPS (20 μM) increased the amplitude, and reduced the PPR of GABAergic IPSCs on dopamine neurons in slices from ethanol-treated rats. Insets: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after Sp-cAMPS (black). (b) Average of 16 experiments from slices prepared 24 hours after ethanol. Bath-applied Sp-cAMPS (20 μM) significantly potentiated GABAergic IPSCs (P < 0.05). (c) Bath applied pCPT-cGMP (100 μM) increased the amplitude and reduced the PPR of GABAergic IPSCs on dopamine neurons in slices from ethanol-treated rats. Insets: averaged IPSCs before (grey) and 20 min after pCPT-cGMP (black). (d) Average of 8 experiments from slices prepared 24 hours after ethanol. Bath-applied pCPT-cGMP (100 μM) increased the amplitude of GABAergic IPSCs. (e) The bar chart shows that 20 min after the application of Sp-cAMPS, and pCPT-cGMP significantly increased the amplitude of IPSCs recorded from slices prepared 24 hours after ethanol (*P < 0.05, compared with baseline before application of Sp-cAMPS, n = 16, or pCPT-cGMP, n = 8). (f) 20 min after application of Sp-cAMPS, and pCPT-cGMP significantly decreased the paired pulse ratio (PPR) of IPSCs recorded from slices prepared 24 hours after ethanol (*P < 0.05, compared with baseline before application of Sp-cAMPS, n = 16, or pCPT-cGMP, n = 8).

A previous study showed that bath-applied pCPT-cGMP, a cGMP analogue robustly increases GABAergic synaptic currents even after in vivo morphine exposure (Nugent et al., 2007). To determine whether cGMP-dependent protein kinases (PKG) signaling is involved in the blockade of LTPGABA induced by in vivo ethanol exposure, pCPT-cGMP was bath-applied to slices prepared from rats 24 hours after ethanol exposure (2g/kg, i.p.). In eight experiments, pCPT-cGMP (100 μM) increased the peak amplitude of IPSC1 (165 ± 27% of pre-drug value; P < 0.05, Fig. 3c, d, e) or the PPR (83 ± 7% of pre-drug values; from 1.13 ± 0.13 in pre-drug to 0.94 ± 0.15 after pCPT-cGMP, P > 0.05, Fig. 3c, insets, 3e, f).

Discussion

Our major finding is that exposure to ethanol, either in vivo or in vitro, blocks long-term potentiation of the GABAA-medicated synaptic transmission (LTPGABA) on dopamine neurons in the VTA of rat brains, and that ethanol-induced blockade involves the activation of μ-opioid receptors (MORs). We hypothesize that these neuroadaptations to ethanol provide a long-lasting mechanism by which ethanol enhances the excitability of dopamine neurons which may contribute to the reinforcing effect of ethanol.

Our recordings of HFS-induced LTPGABA on VTA dopamine neurons are in keeping with previous reports (Nugent et al., 2007; Nugent and Kauer, 2008; Nugent et al., 2009). LTPGABA is heterosynaptic, requiring postsynaptic NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor activation at glutamate synapses, but resulting from increased GABA release at neighboring inhibitory nerve terminals (Nugent et al., 2007). An increased presynaptic GABA release in response to HFS was indicated by the significant reduction in the mean paired pulse ratio (PPR) of GABAergic synaptic currents associated with LTPGABA. The paired pulse stimulation is typically used as an electrophysiological protocol to test for changes in probability of transmitter release (Melis et al., 2002; Zucker and Regehr, 2002; Ye et al., 2004).

We then showed that a 15 min bath-application of 40 mM ethanol before HFS prevented LTPGABA. There is much evidence that a change in GABAergic synaptic transmission is of great importance for the behavioral and cognitive effects of acute ethanol (Mihic, 1999; Siggins et al., 2005; Weiner and Valenzuela, 2006). However, previous in vitro studies of ethanol on IPSCs in several brain regions generated controversial results (Siggins et al., 2005; Weiner and Valenzuela, 2006). Our present study is the first to show that acute ethanol blocks LTPGABA, which is consistent with our recent work demonstrating that acute ethanol decreases IPSCs (Xiao and Ye, 2008); but see (Theile et al., 2008, 2009), who reported ethanol potentiation of IPSCs on VTA dopamine neurons. The cellular mechanism by which acute application of ethanol blocks LTPGABA is not yet clear. Ethanol could inhibit GABA neurons directly, for example by activating K+ channels (like μ-opioids (Johnson and North, 1992b)) or Cl− channels (like GABA, (Suzdak et al., 1986)), or indirectly via NMDA receptors (Stobbs et al., 2004). However, our data showed that ethanol induced suppression of LTPGABA may involve MORs. This is in line with the evidence that acute i.p. injections of ethanol increase the extracellular levels of β-endorphins in the nucleus accumbens, in the VTA and in the central amygdala (Olive et al., 2001; Marinelli et al., 2004; Lam et al., 2008; Jarjour et al., 2009). In the VTA, MORs are expressed on the GABA neurons but not the dopamine neurons (Svingos et al., 2001). It is well documented that activation of MORs inhibits GABA neurons (Johnson and North, 1992a; Garzon and Pickel, 2001; Bergevin et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2007b; Xiao and Ye, 2008; Chefer et al., 2009). Thus, the inhibition of GABA neurons by MORs may contribute to the inhibition of LTPGABA. This idea is further supported by the observation that a brief exposure to DAMGO prevents LTPGABA (Fig. 1, and (Nugent et al., 2007)). Numerous lines of evidence indicate that ethanol reinforcement mechanisms involve, at least partially, the ethanol-induced activation of the endogenous opioid system. Ethanol may alter opioidergic transmission at different levels, including the biosynthesis, release, and degradation of opioid peptides, as well as binding of endogenous ligands to opioid receptors (Mendez and Morales-Mulia, 2008). Our data suggest that a 15 min perfusion of ethanol in brain slices has altered opioidergic transmission. Future studies are warranted to determine which level(s) have been altered by the brief application of ethanol.

We further showed that a single in vivo ethanol exposure blocked LTPGABA in slices prepared 24 hours later, and that ethanol-induced blockade was reversed by in vivo naloxone treatment, indicating again the involvement of activation of MORs. In vivo activation of MORs has been shown to inhibit LTPGABA (Nugent et al., 2007; Nugent and Kauer, 2008). These results suggest an important similarity between opiate action and that of ethanol.

Previous studies have demonstrated that bath-applied cGMP, or SNAP (S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine), the NO donor, significantly potentiated GABAergic IPSCs recorded from VTA dopamine neurons of rats even after in vivo morphine exposure (Nugent et al., 2007; Nugent et al., 2009). In the current study, we showed that bath-applied pCPT-cGMP increased the peak amplitude of GABAergic IPSCs and reduced the PPR on slices prepared from rats 24 hours after ethanol exposure. These data further suggest some of the similarities between the effects of morphine and ethanol. Interestingly, under our experimental conditions, the basal PPR of GABAA IPSCs in slices prepared from rats 24 hours after in vivo ethanol exposure was indistinguishable from those treated with saline. Furthermore, bath-applied Sp-cAMPS (and pCPT-cGMP) further increased the peak amplitude of GABAergic IPSCs in slices of ethanol treated rats, indicating that the GABAergic synapses are not saturated. Conversely, a previous study by Melis and colleagues showed that in slices prepared from mice 24 hours after in vivo ethanol exposure, the PPR of GABAA IPSCs was significantly smaller than those treated with saline. Additionally, forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase failed to potentiate GABAergic IPSCs in slices of ethanol treated mice, indicating that the GABAergic synapses are saturated (Melis et al., 2002). The mechanism underlying the apparent difference between our results and Melis's is unclear. A simplest explanation is that rats are different from mice regarding their responses to a in vivo ethanol treatment. In support of this possibility, a previous study has demonstrated significant differences in ethanol response between mice and rats. Mice show rapid rise and elimination rates and higher peak blood ethanol concentrations (BECs). Rats show more gradual profiles but retain the ethanol in their bloodstream for longer periods (Livy et al., 2003). Intriguingly, our data are consistent with a recent report that although the cAMP-PKA system potentiates GABAA synapses, synaptically induced LTPGABA is independent of PKA activation (Nugent et al., 2009).

As mentioned in the Introduction, evidence implicating the endogenous opioid system in the development and maintenance of alcoholism is growing. The currently available literature suggests that ethanol increases opioid neurotransmission and that this activation is part of the mechanism responsible for its reinforcing effects (Oswald and Wand, 2004). In keeping with this idea, in the current study, we showed that naloxone, a MOR antagonist, reversed ethanol-induced block of LTPGABA. This is also consistent with our recent finding that ethanol suppressed VTA GABA neurons through the activation of MORs (Xiao et al., 2007b; Xiao and Ye, 2008). Our results show that like opioids, exposure to ethanol also blocks LTPGABA.

Acute ethanol exposure increases glutamate transmission to VTA dopamine neurons (Deng et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2009). The loss of normal inhibitory control, coupled with potentiation of excitatory synapses, may represent neuroadaptations that increase the addictive properties of ethanol. Our current work provides an additional example of drug-induced adaptation of GABAergic synapses in response to in vivo and in vitro drug exposure. These findings support the hypothesis that changes in synaptic plasticity may be critical for the development of addiction. Uncovering the cellular mechanisms implicated in the particular forms of synaptic plasticity in the VTA, a brain region related to addiction could advance our knowledge of drug addiction.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by the support of NIH grants to JHY (R01AA016964; R21AA015925). We are grateful for Dr. K. Krnjevic' for his helpful comments on this work.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

References

- Bergevin A, Girardot D, Bourque MJ, Trudeau LE. Presynaptic mu-opioid receptors regulate a late step of the secretory process in rat ventral tegmental area GABAergic neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonci A, Williams JT. Increased probability of GABA release during withdrawal from morphine. J Neurosci. 1997;17:796–803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00796.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefer VI, Denoroy L, Zapata A, Shippenberg TS. Mu opioid receptor modulation of somatodendritic dopamine overflow: GABAergic and glutamatergic mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:272–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BT, Bowers MS, Martin M, Hopf FW, Guillory AM, Carelli RM, Chou JK, Bonci A. Cocaine but not natural reward self-administration nor passive cocaine infusion produces persistent LTP in the VTA. Neuron. 2008;59:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Li KY, Zhou C, Ye JH. Ethanol enhances glutamate transmission by retrograde dopamine signaling in a postsynaptic neuron/synaptic bouton preparation from the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1233–1244. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, North RA. Neurobiology of opiate abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:185–193. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos RA, Lee RS, Criado JR, Henriksen SJ, Steffensen SC. Adaptive responses of gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons in the ventral tegmental area to chronic ethanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:1045–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon M, Pickel VM. Plasmalemmal mu-opioid receptor distribution mainly in nondopaminergic neurons in the rat ventral tegmental area. Synapse. 2001;41:311–328. doi: 10.1002/syn.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz A. Endogenous opioid systems and alcohol addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;129:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s002130050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC. Addiction and the brain: the neurobiology of compulsion and its persistence. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:695–703. doi: 10.1038/35094560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annual review of neuroscience. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyytia P, Kiianmaa K. Suppression of ethanol responding by centrally administered CTOP and naltrindole in AA and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarjour S, Bai L, Gianoulakis C. Effect of acute ethanol administration on the release of opioid peptides from the midbrain including the ventral tegmental area. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1033–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992a;12:483–488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Two types of neurone in the rat ventral tegmental area and their synaptic inputs. J Physiol. 1992b;450:455–468. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:844–858. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Stromberg MF, Kim MJ, Volpicelli JR, Park JM. The effect of antagonists selective for mu- and delta-opioid receptor subtypes on alcohol consumption in C57BL/6 mice. Alcohol. 2000;22:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Wand GS, Li XW, Portoghese PS, Froehlich JC. Effect of mu opioid receptor blockade on alcohol intake in rats bred for high alcohol drinking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:627–635. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam MP, Marinelli PW, Bai L, Gianoulakis C. Effects of acute ethanol on opioid peptide release in the central amygdala: an in vivo microdialysis study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livy DJ, Parnell SE, West JR. Blood ethanol concentration profiles: a comparison between rats and mice. Alcohol. 2003;29:165–171. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Akil H, Watson SJ. Opioid-receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: anatomical and functional implications. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93946-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Hjelmstad GO, Bonci A, Fields HL. Kappa-opioid agonists directly inhibit midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9981–9986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-09981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Fields HL, Hjelmstad GO, Mitchell JM. Delta-opioid receptor expression in the ventral tegmental area protects against elevated alcohol consumption. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12672–12681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4569-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Lock H, Chefer VI, Shippenberg TS, Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. Kappa opioids selectively control dopaminergic neurons projecting to the prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2938–2942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511159103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli PW, Quirion R, Gianoulakis C. An in vivo profile of beta-endorphin release in the arcuate nucleus and nucleus accumbens following exposure to stress or alcohol. Neuroscience. 2004;127:777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis M, Camarini R, Ungless MA, Bonci A. Long-lasting potentiation of GABAergic synapses in dopamine neurons after a single in vivo ethanol exposure. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2074–2082. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02074.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez M, Morales-Mulia M. Role of mu and delta opioid receptors in alcohol drinking behaviour. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:239–252. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801020239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez M, Leriche M, Carlos Calva J. Acute ethanol administration transiently decreases [3H]-DAMGO binding to mu opioid receptors in the rat substantia nigra pars reticulata but not in the caudate-putamen. Neurosci Res. 2003;47:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(03)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ. Acute effects of ethanol on GABAA and glycine receptor function. Neurochem Int. 1999;35:115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent FS, Kauer JA. LTP of GABAergic synapses in the ventral tegmental area and beyond. J Physiol. 2008;586:1487–1493. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent FS, Penick EC, Kauer JA. Opioids block long-term potentiation of inhibitory synapses. Nature. 2007;446:1086–1090. doi: 10.1038/nature05726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent FS, Niehaus JL, Kauer JA. PKG and PKA signaling in LTP at GABAergic synapses. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1829–1842. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW. Stimulation of endorphin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald LM, Wand GS. Opioids and alcoholism. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:339–358. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggins GR, Roberto M, Nie Z. The tipsy terminal: presynaptic effects of ethanol. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;107:80–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Svingos AL, Pickel VM, Henriksen SJ. Electrophysiological characterization of GABAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8003–8015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-08003.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein EA. Ventral tegmental self-stimulation selectively induces opioid peptide release in rat CNS. Synapse. 1993;13:63–73. doi: 10.1002/syn.890130109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stobbs SH, Ohran AJ, Lassen MB, Allison DW, Brown JE, Steffensen SC. Ethanol suppression of ventral tegmental area GABA neuron electrical transmission involves N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:282–289. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzdak PD, Schwartz RD, Skolnick P, Paul SM. Ethanol stimulates gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-mediated chloride transport in rat brain synaptoneurosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4071–4075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theile JW, Morikawa H, Gonzales RA, Morrisett RA. Ethanol enhances GABAergic transmission onto dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area of the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1040–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theile JW, Morikawa H, Gonzales RA, Morrisett RA. Role of 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors in Ca2+-dependent ethanol potentiation of GABA release onto ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:625–633. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JL, Valenzuela CF. Ethanol modulation of GABAergic transmission: the view from the slice. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:533–554. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Ye JH. Ethanol dually modulates GABAergic synaptic transmission onto dopaminergic neurons in ventral tegmental area: role of mu-opioid receptors. Neuroscience. 2008;153:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Zhou C, Li K, Ye JH. Presynaptic GABAA receptors facilitate GABAergic transmission to dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area of young rats. J Physiol. 2007a;580:731–743. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Zhang J, Krnjevic K, Ye JH. Effects of ethanol on midbrain neurons: role of opioid receptors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007b;31:1106–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Shao XM, Olive MF, Griffin WC, 3rd, Li KY, Krnjevic K, Zhou C, Ye JH. Ethanol facilitates glutamatergic transmission to dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:307–318. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JH, Zhang J, Xiao C, Kong JQ. Patch-clamp studies in the CNS illustrate a simple new method for obtaining viable neurons in rat brain slices: glycerol replacement of NaCl protects CNS neurons. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;158:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JH, Wang F, Krnjevic K, Wang W, Xiong ZG, Zhang J. Presynaptic glycine receptors on GABAergic terminals facilitate discharge of dopaminergic neurons in ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8961–8974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2016-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]