Abstract

Previous work from our group and others has shown that patients with breast cancer can generate a T cell response against specific HER2 epitopes. Additionally, preclinical work has shown that this T cell response can be augmented by antigen-directed mAb therapy. This study evaluated the activity and safety of a combination of dendritic cell vaccination given with monoclonal antibody and cytotoxic therapy. We performed a phase I/II study using autologous dendritic cells pulsed with two different HER2 peptides given with trastuzumab and vinorelbine to a study cohort of patients with HER2 overexpressing and a second with HER2 non-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. 17 patients with HER2 overexpressing and 7 with non-overexpressing disease were treated. Treatment was well tolerated with one patient removed from therapy due to toxicity and no deaths. 46% of patients had stable disease after therapy with 4% achieving a PR and no CRs. Immune responses were generated in the majority of patients but did not correlate with clinical response. However, in one patient, who has survived more than 14 years since treatment on the trial, a robust immune response was demonstrated with 25% of her T cells specific to one of the peptides in the vaccine at the peak of her response. These data suggest that autologous dendritic cell vaccination when given with anti-HER2 directed mAb therapy and vinorelbine is safe and can induce immune responses, including significant T cell clonal expansion in a subset of patients.

Keywords: Cancer vaccination, breast cancer, tumor immunotherapy

Introduction

Metastatic breast cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women. Significant advances have been made in the treatment of human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) overexpressing breast cancer through the development of novel HER2-targeted therapies, however metastatic disease remains incurable with modern therapeutics. While the use of trastuzumab, pertuzumab and trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in localized breast cancer have markedly improved early breast cancer outcomes, continued innovation is essential to improve outcomes for patients who develop metastatic disease despite initial HER2-targeted treatment (1, 2).

Despite modest efficacy of the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab in programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) positive metastatic hormone receptor negative, HER2-negative breast cancer, anti-PD-L1 and anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (anti-CTLA-4) agents have not been shown to improve outcomes in HER2-positive breast cancer (3). Instead, the current treatment for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer involves anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab given with taxane chemotherapy, antibody-drug conjugates such as ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd), and small molecule inhibitors of HER2 such as tucatinib and lapatinib given with trastuzumab and capecitabine chemotherapy. More recently, clinical data have suggested that patients with HER2-expressing but not overexpressing tumors, termed HER2-low tumors, are also likely to benefit from HER2-targeted agents (4).

Peptides derived from HER2 are immunogenic in a large proportion of patients, and peptide vaccines have shown immunological activity in the adjuvant setting, although the clinical benefit of this approach is unclear (5–10). DNA vaccination targeting the HER2 intracellular domain has been shown to be safe and to generate antigen-specific T cell responses as well (11). In the advanced or metastatic setting, vaccine-primed T cells have been expanded ex vivo and given in adoptive transfer (12). Dendritic cell (DC) vaccines offer an alternative immunotherapy approach that utilizes peptides derived from intracellular proteins such as HER2 to generate HER2-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes capable of lysing autologous breast cancer cells (13–20). This provides another strategy to target and destroy HER2-expressing cancer cells that is hypothesized to complement existing therapies. Compared to mRNA and peptide vaccines, DC vaccines are more stable and do not rely on the vaccine being taken up by antigen presenting cells (APCs). Previous studies have shown that DCs can be produced from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and subsequently act as APCs capable of initiating a T cell response in the absence of in vivo priming (21–31). Studies of peptide-pulsed DCs have been performed in other advanced cancer types with immune responses detected in over 60% of treated patients (32). Objective responses and improved median overall survival rates have been reported in several of these studies, though durable clinical responses have been infrequent with DC-based vaccines to date (33–42). In intraductal carcinoma in situ, a breast cancer precursor lesion, the magnitude of the anti-HER2 CD4+ T cell responses measured in the sentinel lymph node following neoadjuvant DC vaccination was associated with pathological complete response at the time of surgery (43).

CD34+ derived dendritic cells have been favored over monocyte-derived dendritic cells based on their ability to elicit more potent T-cell immune responses against cancer (44–46). To enhance the activity of the DC vaccine generated for this study, we targeted two epitopes in the HER2 protein: E75 and E90. The rationale for dual targeting of these peptides comes from preclinical work suggesting E90-specific responses enhanced the E75-anti-tumor response. In addition to identification of robust tumor antigens, the activity of DC vaccines relies on cell intrinsic factors. Our group and others have found that antibodies, through engaging Fc receptors (FcRs) on DCs, can enhance the maturity and activity of those cells, possibly lessening the propensity towards an immunosuppressive DC phenotype (47, 48). Additionally, immunological cell death, which can be mediated by specific chemotherapy drugs, may be critical to the activation of innate immune cells such as DCs and to altering the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (49). Thus, to enhance the function of the DC vaccine in this study, we administered it with the anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab and the vinca alkaloid vinorelbine.

Here, we report the results of two sequential phase I/II clinical trials investigating the efficacy of a multiepitope dendritic cell vaccine given with cytotoxic chemotherapy and HER2-targeted therapy in women with HER2-expressing and then overexpressing metastatic breast cancer (32, 50–55). The primary endpoint of the initial study was safety and tolerability while that of the subsequent study was response rate. The secondary endpoint focused on evaluating antigen-specific immune responses before and after therapy. With a more than 14-year follow up of the longest surviving patient, we report on the outcome and immune activity of this combined therapy approach.

Patients and Methods

Patient Eligibility

All patients had histologically proven metastatic breast cancer. HLA-A0201 positivity by DNA genotyping was required as the two peptides utilized bind to HLA-A0201. Breast cancer receptor status was assigned according to ASCO/CAP guidelines at the time the study was conducted. The first trial included patients with HER2-expressing but not overexpressing tumors, defined as 1+ staining by immunohistochemical staining (IHC) or 2+ IHC and not amplified by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) (single probe average HER2 copy number <6 signals/nuclei and/or a dual-probe HER2/CEP17 ratio <2.2) (56, 57). The subsequent trial required HER2 overexpression, defined as 3+ staining by IHC or 2+ staining and amplified by FISH. Patients could have either hormone receptor positive or negative tumors, with hormone receptor positive disease defined by at least 1% of tumor cells staining positive for the estrogen and/or progesterone receptor. Patients were required to be ≥ 18 years old with ECOG performance status 0–2. Cardiac ejection fraction was required to be > 45% and required laboratory parameters included serum creatinine <2.0 mg/dl, ALT/AST ≤ 3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) (≤ 5 times if liver metastases present), bilirubin ≤ 2 times ULN, absolute neutrophil count >1,500/mm3, hemoglobin ≥ 10, platelet count > 100,000/mm3. Patients with stable central nervous system metastases were permitted to enroll. Prior trastuzumab was allowed, however patients who had received prior vinorelbine were excluded. No hormonal therapy or cytotoxic chemotherapy was allowed within 14 days of initial apheresis. No systemic steroids were allowed on trial. Concomitant bisphosphonate therapy was allowed for patients with osseous metastases.

Study Design

The first study in patients with HER2-expressing but not overexpressing metastatic breast cancer (more recently termed HER2-low but not designated as such at the time of the study design) was a phase I study to determine safety. The subsequent phase II study in patients with tumors with HER2-positive tumors was designed with a primary objective to test the hypothesis that the addition of a multiepitope DC vaccine to trastuzumab and vinorelbine would increase the response rate amongst women with metastatic breast cancer. Based on previously reported response rates of 25–30% for single agent vinorelbine in the metastatic setting, this study was designed to include 26 patients to provide a power of 89% to detect a difference in response rate from 35–60% with an alpha error ≤ 0.10 (58–60). The secondary objective was to evaluate the ability of peptide-pulsed DCs plus trastuzumab to induce functional antigen-specific T cells. Each patient was planned to receive six biweekly vaccines unless removed from the study for safety reasons or disease progression.

Vinorelbine and trastuzumab were selected based on preclinical data regarding the activation of DCs by antibodies independent of the expression of the antigen bound to the antibody (61). A biweekly dosing schedule was chosen given similar efficacy with reduced myelosuppression compared to weekly dosing (62).

The studies were reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Boards and conducted in accordance with ethical principles per the Declaration of Helsinki. Both trials were registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT0088985 and NCT00266110). All participants provided written informed consent. The study was monitored per institutional protocol by the Institutional Data Safety and Monitoring Committee at the University of North Carolina.

We assessed the in vitro response to therapy using tetramer analysis and intracellular cytokine assays (Supplementary Figures 1–3). T-cell activity was measured after the administration of the vaccine. An immune response was defined as a three-fold increase in the numbers of tetramer positive cells comparing pre-vaccine to peak post-vaccine values, if the post-vaccine value was greater than 0.5% or a two-fold increase if the pre-vaccine value was greater than 1%. Similarly, we considered a three-fold increase in the percent of cells generating IFN-γ or IL-4 using an irrelevant peptide compared to the peptides in the vaccine by ELISPOT, or by intracellular cytokine or CD107 degranulation assay assessment, or a two-fold increase in pre-vaccine to post-vaccine values if the pre-vaccine value for intracellular cytokine staining is greater than 1% to indicate a response to this therapy.

Procedures and Treatments

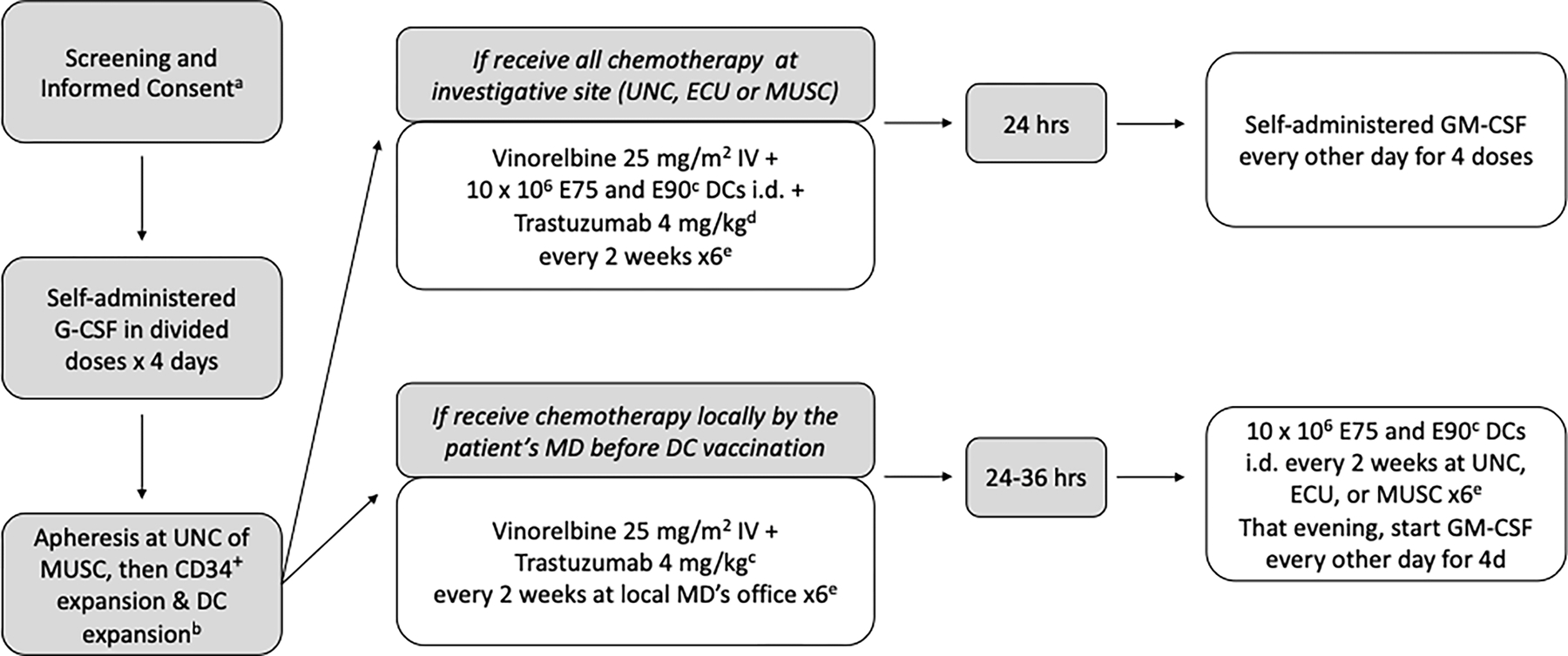

Following patient informed consent and trial enrollment, patients received G-CSF then underwent apheresis followed by CD34+ cell selection and expansion (Figure 1). Patients then received vinorelbine 25mg/m2 IV plus trastuzumab 4mg/kg plus peptide-pulsed dendritic cells every 2 weeks. For the phase I trial patients received a dose escalation of peptide-pulsed DCs at either 2 × 106 or 10 × 106.. For the phase II trial, 10 × 106 peptide-pulsed DCs were administered, with sufficient cells generated to allow patients to receive six injections. For the phase II trial, GM-CSF was administered subcutaneously every other day for four doses starting 24 hours after treatment.

Figure 1. Study Schema.

CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells were mobilized after the administration of G-CSF 10μg/kg subcutaneously each day in divided doses for four days prior to a 15-liter apheresis collection. PBSCs were expanded and differentiated using GM-CSF, FLT3-ligand, stem cell factor (SCF) and interleukin-4 (IL-4). They were then matured ex vivo with GM-CSF, IL-4, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IFN-α, and interleukin-6 (IL-6). The mature, differentiated dendritic cells were then pulsed with HER2 peptides and activated with CD40L. This method produces cells with the surface characteristics and functional activity of dendritic cells. These cells were then cryopreserved for future injection. Infused peptide-pulsed dendritic cells exceeded 80% viability as per the lot release criteria and at least 75% of injected cells had 2 log expression of HLA-DR over control. All injected dendritic cell vaccines demonstrated sterility and effective dendritic cell potency. Immune monitoring results were performed on peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients pre and post dendritic cell vaccines.

Generation of autologous peptide-pulsed dendritic cells

Autologous dendritic cells were differentiated from the CD34+ progenitor cells isolated from a 15L leukapheresis by CliniMACS™ CD34 selection (Miltenyi Biotech, Gladbach, Germany). CD34+ selected cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 in AIM-V media (Gibco) with 10% human AB serum (GeminiBio,West Sacramento CA) and GM-CSF 800 Units/ml (Sanofi, Paris, France ), Flt3 ligand 100 ng/ml (PeproTech, Cranberry NJ) and Stem Cell Factor 50 ng/ml (PeproTech) in Costar Ultra-low Attachment ® plates at an initial concentration of 0.3 × 106 /ml in 3 mls of six well cluster plates for the first five days and then GM-CSF, SCF, Flt3L, and IL-4 (PeproTech) until day eight. After day 8, the expanding cells are cultured in GM-CSF and IL-4 only and subdivided in half when the concentration approached 0.8 × 106/ml to sustain maximum proliferation. Cells were expanded by this method up to 14 days with replenished cytokines every 48 hours when the cultures were either cryopreserved or used to differentiate into mature dendritic cells.

Cryovials of in vitro expanded CD34+-derived cells were thawed and differentiated for an additional 5 days in AIM V with 10% human AB serum, GM-CSF, IL-4, and TNF 20 ng/ml (PeproTech). The TNF was replenished daily. IFN-α (Schering, Kenilworth NJ) 1000 Units/ml and IL-6 (PeproTech) 1000 Units/ml) were added to the differentiation media the last 48 hours of culture before testing for cell surface marker expression by flow cytometry and DC potency in an allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction.

Dendritic cells were incubated overnight with 50 mg/ml either HER2/neu GMP peptide E75 (KIFGSLAFL) or E90 (CLTSTVQLV) (Multiple Peptide Systems, San Diego, CA) and with CD40L (PeproTech) 1 mg/ml for an hour before washing with saline with 2% human serum albumin (Talecris Biotherapeutics) before viability and sterility testing. After thawing, E75-peptide-pulsed dendritic cells and E90-peptide pulsed dendritic cells were immediately used for injection.

Clinical Assessments

Clinical response was defined according to RECIST 1.0 criteria. A partial response was defined as at least a 30% decrease in the longest diameters of target lesions, taking as reference the baseline longest diameter. Progressive disease was defined as at least a 20% increase in the longest diameters of target lesions, taking as a reference the smallest longest diameter recorded since the treatment started or the appearance of one or more new lesions. Stable disease was defined as neither sufficient shrinkage nor increase to qualify as a partial response or progressive disease. Restaging studies inclusive of CT chest, abdomen, pelvis, plain radiography and/or bone scan as clinically necessary were performed after the third cycle of therapy and at least 15 days after the completion of therapy. Restaging was repeated every 3 months in patients who stayed on therapy beyond 6 cycles.

Toxicity was evaluated each cycle using the NCI CTCAEv3. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) included grade III neurologic, pulmonary, cardiac, hepatic or renal toxicity and any grade IV toxicity except hematologic toxicity which was considered a DLT only if related to life-threatening bleeding, febrile neutropenia or causes a two week or greater treatment delay. Patients who experienced a DLT were required to come off the study. Serious adverse events included life-threatening or life-limiting events and events that required hospitalization.

Correlative Assessments

To evaluate the ability of peptide-pulsed DCs plus trastuzumab to induce functional antigen-specific T cells, we measured ex vivo antigen-specific T cell activity against peptide-pulsed and tumor targets by tetramer staining and intracellular cytokine assays using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBCs) isolated from the bloodstream 7 days ± 1 day post therapy. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stained with CD8-Pacific Orange (MHCD0830; Life Technologies) along with PE-HLA-A*02:01 tetramers generated with E75 peptide, E90 peptide, or a negative control peptide, all from Beckman Coulter. For single-cell sorting, sort gates were determined by setting the CD8+ Tetramer+ gate so that it included no cells in the negative tetramer sample. Tetramer+CD8+ T cells were sorted by an iCyt Reflection high-speed sorter at 1 cell/well into a 96-well PCR plate with each well containing 4 μL buffer (0.5× PBS, 10 mM DTT, and 8 U RNaseOUT (Invitrogen). Plates were kept frozen at −80°C prior to RT-PCR analysis(63).

HLA Typing

All patients underwent initial screening informed consent prior to HLA testing. Patients who consented for the study then underwent an evaluation for the expression of HLA-A0201 using DNA-based techniques.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining and Upregulation of CD107 expression

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were co-cultured at a 1:5 ratio with un-pulsed autologous dendritic cells, or E75 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells, or E90 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells in AIMV 10% human AB serum and unlabeled anti-CD28/49 (BD Biosciences, San Jose CA) and anti-CD107-PE (Pharmingen, San Jose CA) for an hour. Brefeldin A and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) 5 mg/ml each were added and the staining and stimulation were continued for an additional 5 hrs. Following FACs lyse and FACS (Sigma) permeabilization steps, the PBMC:DC stimulated cells were blocked with 200 ng/ml murine IgG before staining with anti-CD8 PerCP and anti-IFN-γ FITC (BD Biosciences) and fixing in 1% formalin (Polysciences, Warrington PA) in PBS before acquisition on FACSCaliber™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Tetramer staining

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were resuspended in 0.5% Human Serum Albumin in PBS and 200 ng/ml purified mouse IgG (Sigma) prior to incubation with CD8-FITC (Beckman-Coulter) and either phycoerythrin E75, E90, or negative tetramer (iTAg™ MHC Class I Human Tetramer-SA-PE, (MBL International Corporation, Woburn MA). Stained cells were washed and fixed in 1% formalin (Polysciences) in PBS an hour before acquisition on FACSCaliber™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

In Vitro stimulation of E75 or E90 specific CD8 Effector T cells

Peptide-pulsed dendritic cells were co-cultured with autologous PBMCs in AIMV 10% human AB serum and IL-2 (20 Units/ml) and IL-7 (10 ng/ml ), PeproTech at a ratio of 20 PBMCs: 1 DC for the initial stimulation for 7 days and at a ratio of 100 PBMCs:1peptide-pulsed DCs for restimulation at 14 days. The effector T cells assays for tetramer and the upregulation of CD107 and IFN-γ were performed after 7 days post stimulation.

Single-cell PCR and Sequencing

RT-PCR amplification and sequencing of TCRβ clonotypes was performed using multiplex primers and nested PCR covering all human TCRβ variable region genes and the β-chain constant region(64). PCR products were treated with Exonuclease I and shrimp alkaline phosphatase and sequenced by the UNC Genome Analysis Facility. TCRβ sequence identifications were made using the IMGT/HighV-QUEST software tool (65).

T Cell Receptor Sequencing and Repertoire Profiling

Sequence data were processed using Python and R scripts developed in the laboratory. TCR sequences were analyzed for the presence of the conserved invariant cysteine and FGXG motifs that define the CDR3 region in one reading frame. Sequences that did not exhibit this motif or had stop codons in the motif reading frame were excluded. TRBV and TRBJ gene identifications were made by either exact alignment or the highest scoring Smith–Waterman alignment to the germline reference gene sequences annotated in IMGT (http://www.imgt.org/IMGTrepertoire)(64, 66).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in R v4.0.3,(67) additionally using packages survminer,(68) ggplot2,(69) viridis,(70) and igraph (71). The overall survival (OS) curve was plotted to include the 95% confidence intervals around the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Pairwise comparisons of pre and post-vaccine T cell population features were done using paired Welch’s t tests. Associations of T cell population features with OS were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards modeling with individual features as the predictor variables and OS as the response variable. The manuscript was generated using the CONSORT reporting guidelines (72).

Results

This was a single site phase I/II study in which 52 patients consented to HLA testing for LCCC 0310 and 99 consented for HLA testing for LCCC 0418. Of these, 12 patients were eligible for therapy on LCCC 0310 with seven female patients enrolled at the University of North Carolina Hospitals. 30 patients were eligible for LCCC 0418 with nineteen female patients enrolled on the phase II trial, LCCC 0418, for tumors that overexpressed HER2. Patient decision was the primary reason eligible patients did not enroll. Enrollment was from 4/16/2004–12/02/2011. Two patients died prior to receiving treatment on the trial but are included in the intent to treat group for OS. Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients had hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (83%). Nearly 80% of patients had visceral metastases at the time of trial participation. One third of patients had no prior lines of chemotherapy-containing treatment in the metastatic setting, while 46% had 1 prior line and 21% had 2 or more prior lines. No patients on LCCC 0310 (Her2-expressing) had received prior trastuzumab. The majority of patients on LCCC 0418 had received trastuzumab prior to trial participation (82%). Five patients had prior HER2-directed therapy with lapatinib and one patient had prior trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1). As toxicities and efficacy were similar, clinical outcomes were combined while we evaluated the immune correlatives separately.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Patient Characteristics (n=24) | |

| Age, years (range) | 56 (39–69) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 24 (100%) |

| Race | |

| Black | 2 (8.3%) |

| White | 22 (91.7%) |

| Hormone Receptor Status | |

| Positive | 20 (83.3%) |

| Negative | 4 (16.7%) |

| HER2 Receptor Status | |

| 1+ IHC | 2 (8.3%) |

| 2+ IHC | 8 (33.3%) |

| Not amplified by FISH | 4 |

| FISH not performed | 2 |

| FISH amplified | 2 |

| 3+ IHC | 14 (58.3%) |

| Visceral Metastases | |

| Yes | 19 (79.2%) |

| No | 5 (20.8%) |

| CNS Metastases | |

| Yes | 2 (8.3%) |

| No | 22 (91.7%) |

| Prior Lines of Chemotherapy in the Advanced Setting | |

| 0 | 8 (33.3%) |

| 1 | 11 (45.8%) |

| 2 | 4 (16.7%) |

| 3+ | 1 (4.2%) |

| Prior Trastuzumab | |

| Yes | 14 (58.3%) |

| No | 10 (41.7%) |

Excludes the two patients who died prior to receiving treatment on trial.

IHC=immunohistochemistry staining

FISH=Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

CNS=central nervous system

Assessments included hormone receptor-positivity, presence of visceral metastases, prior lines of chemotherapy, use of trastuzumab and/or previous HER2-directed therapies.

Characteristics of the infused DCs expanded from CD34 progenitors are provided in Supplementary Fig 1. The infused DCs expressed high levels of CD40, CD86, CD11c and HLA DR with moderate expression of CD83 and very minimal expression of CD14, consistent with the infusion of activated and mature DCs.

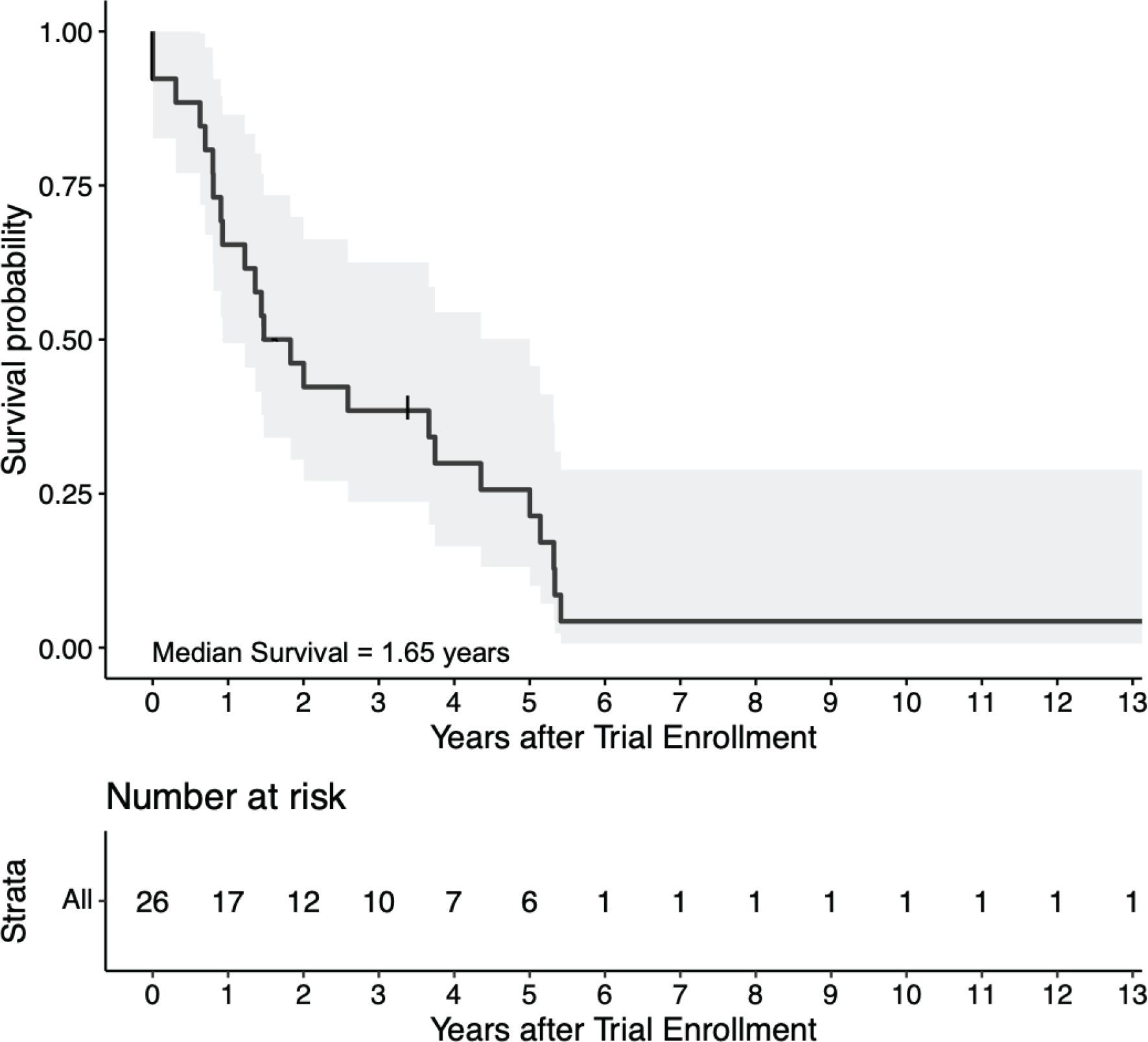

Of the 24 patients treated on both trials, one patient (4%) had a partial response. Eleven patients (46%) achieved stable disease as best response on treatment. There were no complete responses. Fifteen patients (63%) received six or more dendritic cell vaccines, with the maximum number of vaccines received by a single patient being nine. The PFS was 3.3 months, with a range from 1.1 to 9.5 months. Median overall survival was 1.65 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overall Survival in Patients Treated with Dual-Epitope HER2 Dendritic Cell Vaccination.

The Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival in the intention-to-treat population is shown with its 95% confidence interval. Two patients were enrolled but died of disease progression prior to the first vaccination. One patient had prolonged survival over ten years and continues to be alive at the time of their last clinic follow up on December 3, 2020.

The only grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were hematologic (one patient with grade 4 neutropenia, one with grade 3 leukopenia, NOS and one with grade 3 anemia) (Table 2). The most common TRAEs were anemia, neutropenia, and fatigue. Hypocalcemia was the next most common adverse event. Five patients experienced fevers and/or chills. Two patients experienced grade 2 allergic reactions to GM-CSF, one of which qualified as an SAE for which the patient discontinued the study. One patient experienced a grade 1 injection reaction to the dendritic cell vaccine and was removed from the study. This was considered a DLT. The only additional DLT observed with neutropenia, requiring a dose reduction of vinorelbine in three patients. Two additional SAEs occurred due to hospitalizations for symptoms unrelated to treatment, with one leading to a survival event while the patient was on study.

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events, serious adverse events and dose-limiting toxicities.

| Adverse Event | Any Grade | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | 20 | 17 | 13 | 3 | 2 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 1 | 1+ | ||

| Allergic reaction | 1 | 1+ | |||

| Anemia | 8 | 7 | 1 | ||

| Constipation | 2 | 2 | |||

| Cough | 1 | 1 | |||

| Diarrhea | 2 | 2 | |||

| Fatigue | 7 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Fever/Chills | 5 | 5* | |||

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hypocalcemia | 6 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Hypokalemia | 3 | 3 | |||

| Hyponatremia | 4 | 4 | |||

| Hypomagnesemia | 2 | 2 | |||

| Injection site reaction | 2 | 1^ | 1 | ||

| Leukopenia, not specified | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Lymphopenia | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Nausea | 3 | 3 | |||

| Neutropenia | 7 | 3 | 4^ | 1^ | |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Shortness of breath | 2 | 1 | 1+ | ||

| Strep Throat | 1 | 1 | |||

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Upper respiratory infection | 1 | 1 |

Serious adverse event (hospitalization for abdominal pain (n=1), unrelated to treatment; hospitalization for shortness of breath (n=1), unrelated to treatment; allergic reaction to leukocyte growth factor (n=1), patient removed from study).

Dose-limiting toxicity (neutropenia (n=3), dose-reduced; injection site reaction (n=1), therapy discontinued)

Regimen interrupted (fever (n=1)).

Additional grade 1 observed in 1 patient: ALT increase, AST increase, creatinine increase, headache, hypermagnesemia, hypotension, rhinitis, sensory neuropathy, shortness of breath, urinary tract infection, weight loss.

Reasons for trial discontinuation included completion of therapy (either six vaccine treatments or more than six which was discontinued when vaccine doses were completely utilized) (n=10), progressive disease (n=12) and leukine injection reaction (n=2). The five patients who received more than 6 vaccines had a longer survival compared to those who did not complete vaccination with all surviving more than 3.5 years beyond their first treatment on trial, with one of these patients remaining alive more than 14 years after vaccination. Details regarding her clinical course are available in Supplementary Figure 4.

Evaluation of E75 and E90-specific CD8+ T Cell Responses to Therapeutic Vaccination

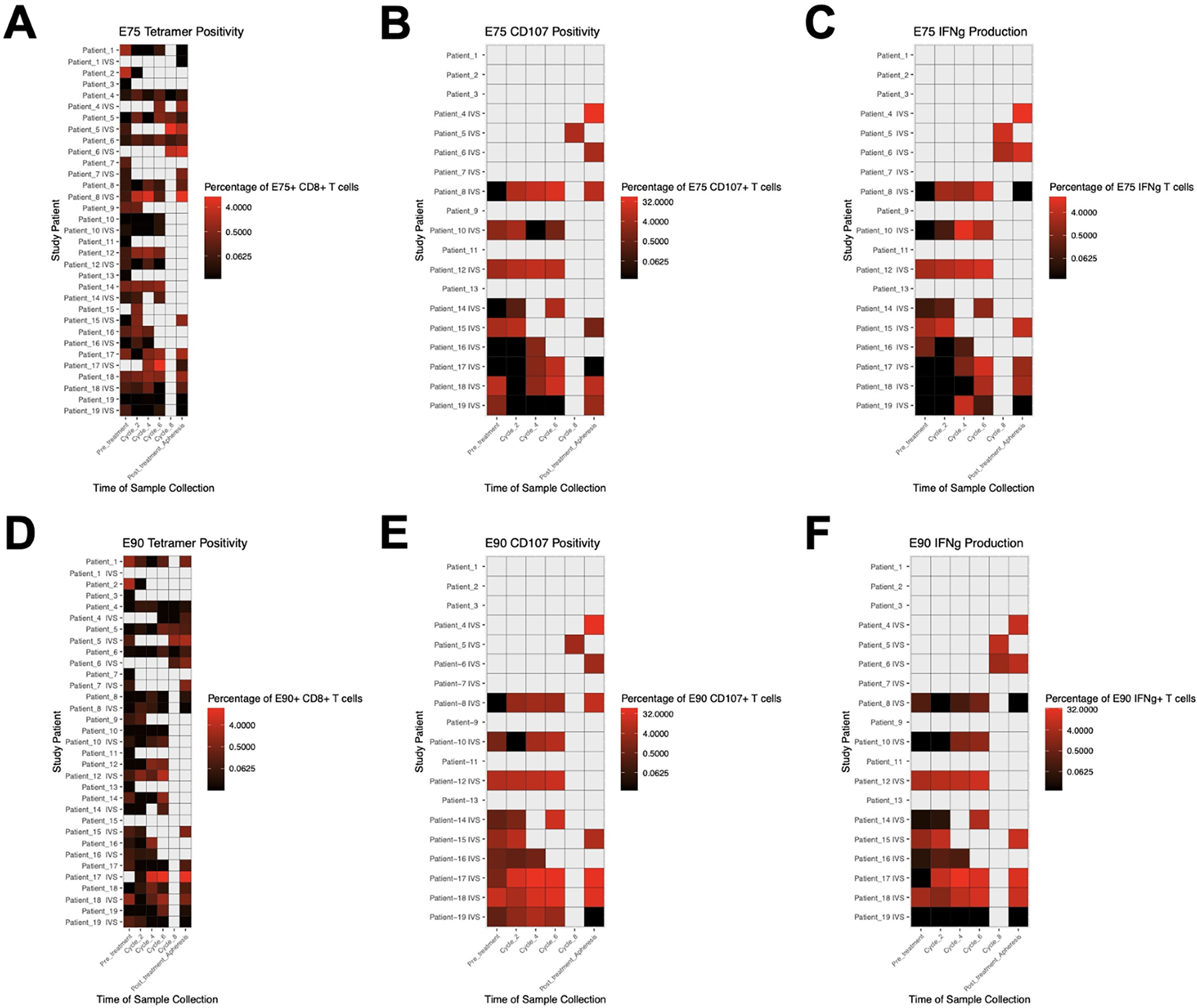

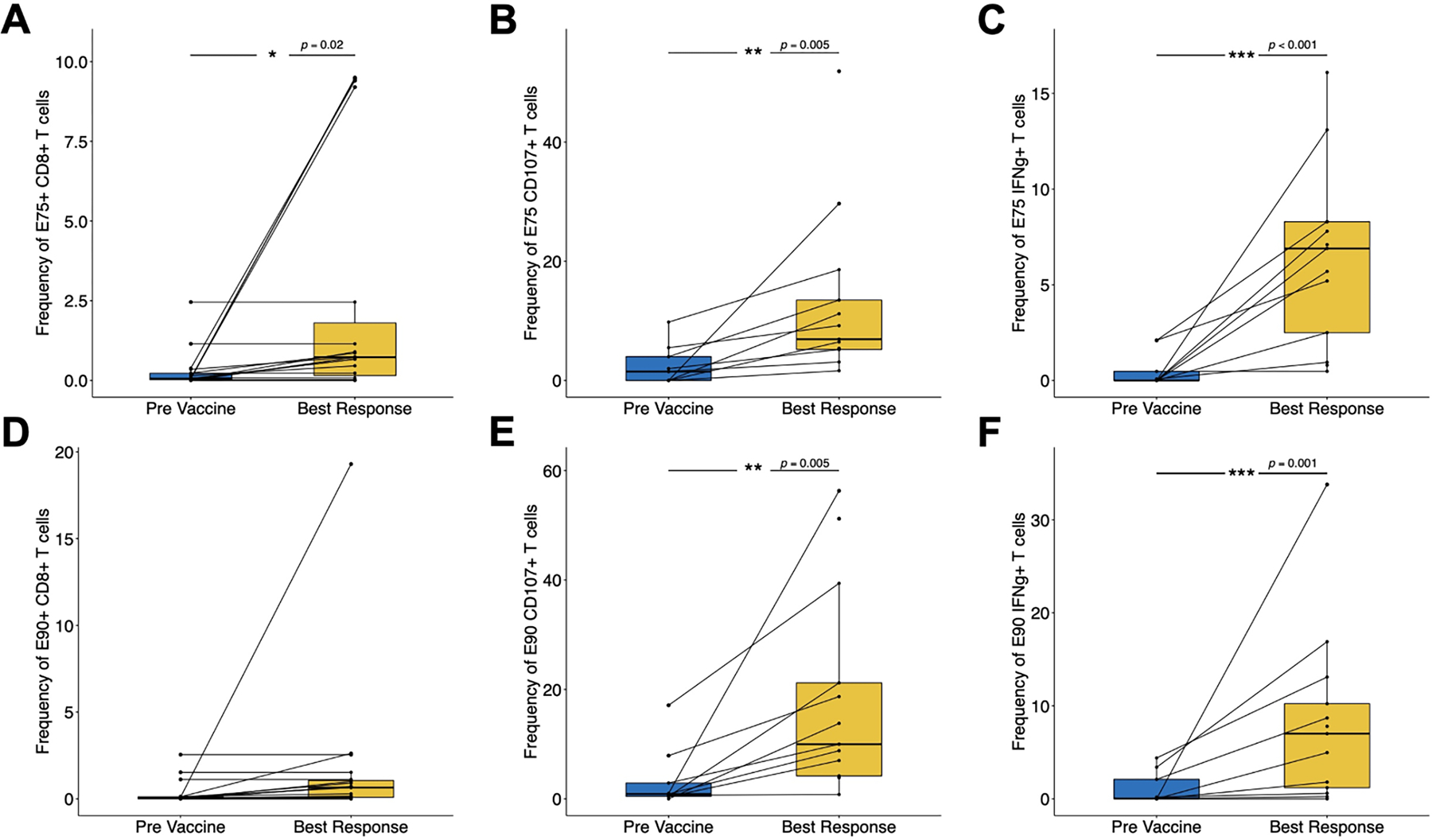

For the LCCC0418 study cohort, we used flow cytometry assays to quantify E75 and E90 antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, measure IFN-γ secretion, and evaluate cytotoxic activity via staining for cell surface CD107a on peripheral blood T cell populations. Representative examples of tetramer, ELISPOT and CD107-positive T cells respectively are shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Immune monitoring results for this study cohort over the study time points are summarized in Figure 3. Only E75 and E90-specific CD8+ T cell numbers were measured in the LCCC0310 study cohort (Supplementary Figure 3). Although there was variability in time to best immunological response, epitope specific T cell number, IFN-γ production, and cytotoxicity were all increased post-vaccination relative to pre-vaccination levels (Figure 4). Immunological vaccine responses were heterogeneous, with patients having different overall magnitudes of response and different responses across the variables tested (number of epitope specific CD8+ T cells, IFN-γ secretion, cell surface CD107a expression) (Supplementary Figure 3). None of the variables tested were significantly associated with overall survival following vaccination (Table 3).

Figure 3. Immune monitoring results in the LCCC0418 study cohort.

Leukapheresis samples were analyzed prior to first vaccination and at the end of the study. Peripheral blood samples were analyzed on the days of cycles #2, #4, #6, and #8 in vaccinated patients. Heatmaps show (A) frequency of E75-specific CD8+ T cells, (B) frequency of CD8+ T cells positive for CD107 surface staining after stimulation with E75 peptide, (C) frequency of CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ after stimulation with E75 peptide, (D) frequency of E90-specific CD8+ T cells, (E) frequency of CD8+ T cells positive for CD107a surface staining after stimulation with E90 peptide, (F) frequency of CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ after stimulation with E90 peptide. Gray boxes represent time points when samples were not collected.

Figure 4. Increase of E75 and E90 specific T cell responses in treated patients.

Pre-treatment immune monitoring measurements were compared with the time point of best response on treatment: (A) frequency of E75-specific CD8+ T cells, (B) frequency of CD8+ T cells positive for CD107 surface staining after stimulation with E75 peptide, (C) frequency of CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ after stimulation with E75 peptide, (D) frequency of E90-specific CD8+ T cells, (E) frequency of CD8+ T cells positive for CD107 surface staining after stimulation with E90 peptide, (F) frequency of CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ after stimulation with E90 peptide.

Table 3.

Variables tested to probe heterogeneity of immunological vaccine responses.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E75 Tetramer | 0.93 | 0.81 – 1.07 | 0.32 |

| E75 CD107 | 1.01 | 0.97 – 1.05 | 0.55 |

| E75 IFNg | 1.00 | 0.87 – 1.16 | 0.99 |

| E90 Tetramer | 1.03 | 0.92 – 1.15 | 0.59 |

| E90 CD107 | 1.02 | 0.99 – 1.05 | 0.25 |

| E90 IFNg | 1.02 | 0.95 – 1.10 | 0.61 |

Assessment of vaccine responses was based on number of epitope specific CD8+ T cells, IFN-γ secretion, cell surface CD107a expression as determined by flow cytometric analysis. None of the variables tested were significantly associated with overall survival following vaccination.

T Cell Receptor Repertoire Profiling of E75-specific CD8+ T Cells

We performed single cell sorting of E75-specific CD8+ T cells followed by TCRβ sequencing to evaluate diversity of the antigen-specific T cell receptor repertoire in the context of vaccine therapy. Repertoire diversity was not significantly different in pre-vaccination versus post-vaccination samples (Figure 5).

Figure 5. T cell receptor beta repertoire profiling in treated patients.

(A) Rank-frequency plot showing frequency distributions of pre-vaccine (dashed lines) and post-vaccine (solid lines) E75-specific CD8+ T cell populations. Distinct colors represent individual patients. (B) TCR repertoire diversity measurements of E75-specific CD8+ T cell populations before and after vaccine therapy.

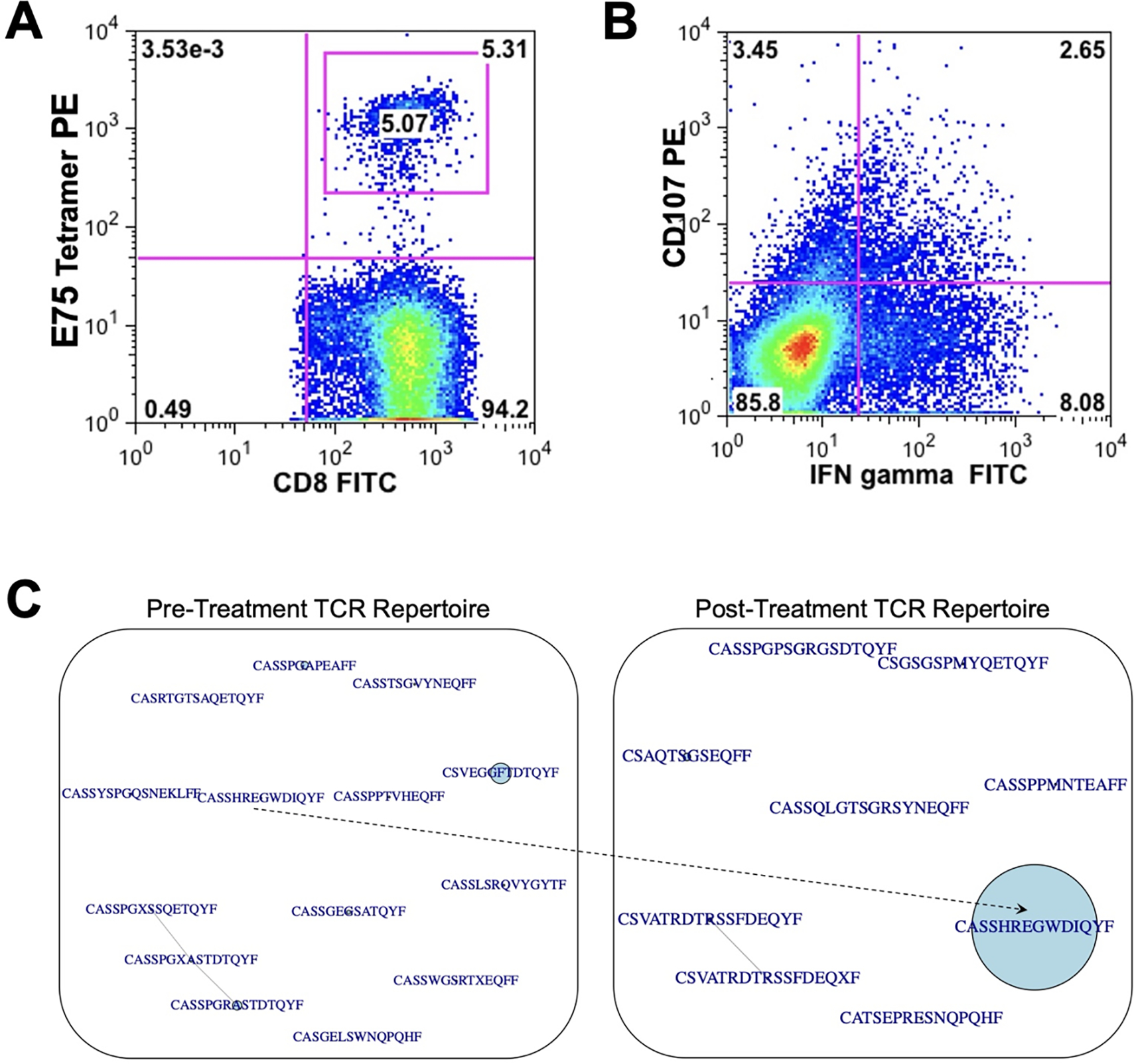

Robust E75-specific CD8+ T Cell Response in an Exceptional Responder

Given the remarkable survival at 14 years for one patient treated with this multiepitope DC vaccination, we performed an in-depth characterization of the immune response in this patient post-therapy. This patient had an increased frequency of E75-specific CD8+ T cells, CD8+ T cell production of IFN-γ, and cell surface expression of CD107a after vaccination (Figure 6A–B). Using next generation sequencing, we also found decreased TCR repertoire diversity (increased clonality) in the E75-specific CD8+ T cell population following therapeutic vaccination. Prior to vaccine therapy, we identified 14 different clonotypes as demonstrated by different CDR3 regions from T cells in the bloodstream from this patient specific for the E75 or E90 epitopes. Interestingly, after vaccination we identified a dominant single TCR beta clonotype with the complementary determining region 3 (CDR) amino acid sequence CASSHREGWDIQYF, specific for the E75 epitope, which was present at low frequency in the pre-treatment TCR repertoire but became the dominant clonotype post-treatment (Figure 6C) with greater than 25% of the repertoire composed of this single clone.

Figure 6. Robust E75-specific CD8+ T cell responses in an exceptional responder.

(A) Frequency of E75-specific CD8+ T cells, (B) frequency of CD8+ T cells positive for CD107 surface staining after stimulation with E75 peptide (y-axis) and frequency of CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ after stimulation with E75 peptide (x-axis), (C) Sequence similarity networks showing TCR repertoires of the sorted E75-specific CD8+ T cells. TCR clonotypes were considered identical if they expressed the same Variable gene, Joining gene, and Complementary Determining Region 3 (CDR3) gene segment. CDR3 amino acid sequences are shown here, with central circles corresponding to relative abundance in the TCR repertoire. The sequence CASSHREGWDIQYF was present in a low frequency in the pre-treatment repertoire and expanded to become a dominant clonotype in the post-treatment TCR repertoire.

Discussion

Here, we provide evidence that peptide-pulsed dendritic cells can be effectively generated and given in combination with chemotherapy and HER2-targeted therapy, with few grade 2 or higher adverse events and all but one patient able to complete at least three vaccinations. The combination of autologous peptide-pulsed DCs with trastuzumab and vinorelbine stable disease led to stable disease in 46% and partial response in 4% with a median survival of 1.65 years. Quite surprisingly, one patient, who had the most robust immunological response post-vaccination, continues to experience long-term survival with continued bone-only disease more than 14 years after trial participation.

We did not find that the level of expression of HER2 was a determinant of response to this vaccine as patients with HER2 expression but not overexpression (treated on the phase I study) responded similarly to those with HER2 overexpression in the phase II study. Our rationale for studying this patient population was pre-clinical data suggesting that very low level of expression of immunodominant peptide/MHC complexes could induce a CD8+ T cell response. Our findings are particularly interesting given recent data demonstrating clinically significant therapeutic activity of the HER2-targeted antibody drug conjugate trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with low levels of HER2 expression (73). Given that patients with metastatic hormone receptor positive and triple negative breast cancer have few if any options besides chemotherapy in the later line setting, which rarely provides durable responses, these data suggest additional development of targeted and immune-based therapeutics specific to HER2 that take advantage of even low levels of HER2 expression.

Dendritic cell vaccination induced an immune response as demonstrated by increased antigen-specific T cell responses, including increased E75+ CD8+ T cells by tetramer analysis, increased frequency of IFN-γ-secreting T cells with E75 and E90 stimulation and increased frequency of CD107+ T cells with E75 and E90 stimulation. Four of six patients with available data had increased T cell receptor repertoire clonality after vaccination. However, these responses were not correlated with clinical efficacy, which is similar to published data (74). There are a number of reasons for this that include a lack of understanding of what level of antigen-specific T cell number or functional activity in the bloodstream correlates with a clinical response post vaccination, the absence of data regarding T cell activity at the tumor site, possible local immunosuppression that may limit the efficacy of activated T cells, the potential development of T cell exhaustion, which had not been well characterized when this study was underway, and limitations on the effector activity being measured. While we found that the vaccine elicited greater number of T cells after treatments, these values did not approach those found in individuals after viral infection.

We found one patient who had an extremely robust immune response to this therapy (see Supplemental Figure 4 for treatment schema). Prior to vaccination, she had evidence of an oligoclonal response to HER2 with a very small population of T cells that expressed the immunodominant TCR found post vaccination. After vaccination, she had a robust T cell response to the E75 epitope with an increased percentage of T cells specific for E75 that generated IFN-γ and lytic activity by in vitro stimulation after the completion of vaccine therapy. Additionally, she had E75-specific tetramer positive cells present post vaccination. Finally, close to 25% of her T cell repertoire post vaccination was represented by one clonal CDR3 region that was present at a much lower frequency prior to vaccination, strongly suggesting that the vaccine was capable of expanding an endogenous immune response. Quite interestingly this patient is alive 14 years after the diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer (post vaccine treatment summarized in Supplemental Figure 4).

The limitations of this study include the absence of a control group that received vinorelbine and trastuzumab without vaccination (although most patients in the phase II trial had received prior chemotherapy and 82% had received trastuzumab) to allow the vaccine contribution to be assessed alone, the absence of immune assessment at the tumor site, and the modest sample size. Immune monitoring was performed on the peripheral blood, however in the context of neoadjuvant HER2 DC vaccination for DCIS, clinical response was associated with T cell responses measured in the sentinel lymph node but not in blood (43). Additionally, this study was performed prior to the development of newer therapies for HER2-expressing tumors, which limits its applicability to current standard of care.

In conclusion, multiepitope dendritic cell vaccines can be successfully generated and safely given to patients with metastatic breast cancer. Vaccine-specific T cell responses were seen in the context of concurrent chemotherapy plus HER-2 targeted therapy, even in patients who had multiple lines of therapy prior to vaccination. Immunodominant antigen responses varied between individuals, although both antigens tested were presented by HLA-A*02:01 (and all enrolled patients expressed this HLA allele). While much vaccine work in HER2+ breast cancer has focused on the E75, AE37, and GP2 peptides as well as peptide mixtures, in this study we saw T cell responses elicited to the E90 peptide as well. There was only one objective response in this study cohort despite more frequent generation of vaccine epitope-specific T cell responses, however a significant number of patients treated had stable disease and nearly 30% of patients survived more than five years from their initial treatment on the trial, which is longer than historical survival for patients with metastatic breast cancer. T cell responses after vaccination were heterogeneous and not statistically associated with improved survival. One patient, with the most robust expansion of a T cell clone post vaccination, is still alive 14 years after treatment with a small frequency clone pre-vaccination greatly expanded by this therapy. These findings provide an impetus for a larger phase clinical trial to test the efficacy of this combination in patients with metastatic breast cancer, as well as to include the E90 peptide in future multiepitope HER2 vaccine formulations.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Combinatorial dual-epitope DC vaccine is safe.

This vaccine regimen induced an immune response in a minority of patients.

One patient had an exceptional response and long-term survival.

Funding:

This work was supported by funds from the National Cancer Institute R21 CA089961, P50CA058223 and the Susan G Komen for the Cure Foundation (grant number NA) all to JSS

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Dr Vincent: Research Funding: Merck Inc, Genecentric, Cancer Research Institute

Dr. Anders: Research funding PUMA, Lilly, Merck, Seattle Genetics, Nektar, Tesaro, G1-Therapeutics, ZION, Novartis, Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Elucida.

Compensated consultant role: Genentech, Eisai, IPSEN, Seattle Genetics; Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Immunomedics, Elucida; Athenex.

Honoraria: Genentech, Eisai, IPSEN, Seattle Genetics, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Immunomedics, Elucida, Athenex. No dates.

Royalties: UpToDate, Jones and Bartlet.

Dr Collichio: Research funding Bristol Myers Squibb, Replimune and Amgen.

Dr. Serody Research Funding Merck Inc, Carisma Therapeutics, Glaxo Smith Kline.

Compensated Consultant: PIQUE Therapeutics.

Intellectual Property: Tessa Therapeutics: Use of lymphodepletion and CD30.CAR T cells for patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma. He has filed for IP protection for the use of STING agonists to enhance CAR T cell therapy for the treatment of patients with solid tumors.

Ethics approval: University of North Carolina Office of Human Research Ethics Institutional Review Board, IRB numbers 03–1571 and 05–2860.

Consent to participate: All individuals signed informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of data and material:

Correlative study data will be provided to investigators at the publication of these data.

References

- 1.von Minckwitz G, Procter M, de Azambuja E, Zardavas D, Benyunes M, Viale G, Suter T, Arahmani A, Rouchet N, Clark E, Knott A, Lang I, Levy C, Yardley DA, Bines J, Gelber RD, Piccart M, Baselga J, A. S. Committee, and Investigators. 2017. Adjuvant Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab in Early HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 377: 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Minckwitz G, Huang CS, Mano MS, Loibl S, Mamounas EP, Untch M, Wolmark N, Rastogi P, Schneeweiss A, Redondo A, Fischer HH, Jacot W, Conlin AK, Arce-Salinas C, Wapnir IL, Jackisch C, DiGiovanna MP, Fasching PA, Crown JP, Wulfing P, Shao Z, Rota Caremoli E, Wu H, Lam LH, Tesarowski D, Smitt M, Douthwaite H, Singel SM, Geyer CE Jr., and Investigators K. 2019. Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residual Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 380: 617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, Nowecki Z, Im SA, Yusof MM, Gallardo C, Lipatov O, Barrios CH, Holgado E, Iwata H, Masuda N, Otero MT, Gokmen E, Loi S, Guo Z, Zhao J, Aktan G, Karantza V, Schmid P, and K.-. Investigators. 2020. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 396: 1817–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diéras V, Deluche E, and Lusque A. 2022. Abstract PD8–02: Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) for advanced breast cancer patients (ABC), regardless HER2 status: A phase II study with biomarkers analysis (DAISY). Cancer Research 82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benavides LC, Gates JD, Carmichael MG, Patil R, Holmes JP, Hueman MT, Mittendorf EA, Craig D, Stojadinovic A, Ponniah S, and Peoples GE. 2009. The impact of HER2/neu expression level on response to the E75 vaccine: from U.S. Military Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Group Study I-01 and I-02. Clin Cancer Res 15: 2895–2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittendorf EA, Clifton GT, Holmes JP, Clive KS, Patil R, Benavides LC, Gates JD, Sears AK, Stojadinovic A, Ponniah S, and Peoples GE. 2012. Clinical trial results of the HER-2/neu (E75) vaccine to prevent breast cancer recurrence in high-risk patients: from US Military Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Group Study I-01 and I-02. Cancer 118: 2594–2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittendorf EA, Ardavanis A, Litton JK, Shumway NM, Hale DF, Murray JL, Perez SA, Ponniah S, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M, and Peoples GE. 2016. Primary analysis of a prospective, randomized, single-blinded phase II trial evaluating the HER2 peptide GP2 vaccine in breast cancer patients to prevent recurrence. Oncotarget 7: 66192–66201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clifton GT, Litton JK, Arrington K, Ponniah S, Ibrahim NK, Gall V, Alatrash G, Peoples GE, and Mittendorf EA. 2017. Results of a Phase Ib Trial of Combination Immunotherapy with a CD8+ T Cell Eliciting Vaccine and Trastuzumab in Breast Cancer Patients. Ann Surg Oncol 24: 2161–2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittendorf EA, Lu B, Melisko M, Price Hiller J, Bondarenko I, Brunt AM, Sergii G, Petrakova K, and Peoples GE. 2019. Efficacy and Safety Analysis of Nelipepimut-S Vaccine to Prevent Breast Cancer Recurrence: A Randomized, Multicenter, Phase III Clinical Trial. Clin Cancer Res 25: 4248–4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown TA 2nd, Mittendorf EA, Hale DF, Myers JW 3rd, Peace KM, Jackson DO, Greene JM, Vreeland TJ, Clifton GT, Ardavanis A, Litton JK, Shumway NM, Symanowski J, Murray JL, Ponniah S, Anastasopoulou EA, Pistamaltzian NF, Baxevanis CN, Perez SA, Papamichail M, and Peoples GE. 2020. Prospective, randomized, single-blinded, multi-center phase II trial of two HER2 peptide vaccines, GP2 and AE37, in breast cancer patients to prevent recurrence. Breast Cancer Res Treat 181: 391–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Disis MLN, Guthrie KA, Liu Y, Coveler AL, Higgins DM, Childs JS, Dang Y, and Salazar LG. 2023. Safety and Outcomes of a Plasmid DNA Vaccine Encoding the ERBB2 Intracellular Domain in Patients With Advanced-Stage ERBB2-Positive Breast Cancer: A Phase 1 Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 9: 71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Disis ML, Dang Y, Coveler AL, Marzbani E, Kou ZC, Childs JS, Fintak P, Higgins DM, Reichow J, Waisman J, and Salazar LG. 2014. HER-2/neu vaccine-primed autologous T-cell infusions for the treatment of advanced stage HER-2/neu expressing cancers. Cancer Immunol Immunother 63: 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Disis ML, Pupa SM, Gralow JR, Dittadi R, Menard S, and Cheever MA. 1997. High-titer HER-2/neu protein-specific antibody can be detected in patients with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 15: 3363–3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Disis ML, Gooley TA, Rinn K, Davis D, Piepkorn M, Cheever MA, Knutson KL, and Schiffman K. 2002. Generation of T-cell immunity to the HER-2/neu protein after active immunization with HER-2/neu peptide-based vaccines. J Clin Oncol 20: 2624–2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisk B, Blevins TL, Wharton JT, and Ioannides CG. 1995. Identification of an immunodominant peptide of HER-2/neu protooncogene recognized by ovarian tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte lines. J Exp Med 181: 2109–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhns JJ, Batalia MA, Yan S, and Collins EJ. 1999. Poor binding of a HER-2/neu epitope (GP2) to HLA-A2.1 is due to a lack of interactions with the center of the peptide. J Biol Chem 274: 36422–36427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lustgarten J, Theobald M, Labadie C, LaFace D, Peterson P, Disis ML, Cheever MA, and Sherman LA. 1997. Identification of Her-2/Neu CTL epitopes using double transgenic mice expressing HLA-A2.1 and human CD.8. Hum Immunol 52: 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navabi H, Jasani B, Adams M, Evans AS, Mason M, Crosby T, and Borysiewicz L. 1997. Generation of in vitro autologous human cytotoxic T-cell response to E7 and HER-2/neu oncogene products using ex-vivo peptide loaded dendritic cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 417: 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reilly RT, Gottlieb MB, Ercolini AM, Machiels JP, Kane CE, Okoye FI, Muller WJ, Dixon KH, and Jaffee EM. 2000. HER-2/neu is a tumor rejection target in tolerized HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Cancer Res 60: 3569–3576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaks TZ, and Rosenberg SA. 1998. Immunization with a peptide epitope (p369–377) from HER-2/neu leads to peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes that fail to recognize HER-2/neu+ tumors. Cancer Res 58: 4902–4908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell D, Young JW, and Banchereau J. 1999. Dendritic cells. Adv Immunol 72: 255–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart DN 1997. Dendritic cells: unique leukocyte populations which control the primary immune response. Blood 90: 3245–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lotze MT, Shurin M, Davis I, Amoscato A, and Storkus WJ. 1997. Dendritic cell based therapy of cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 417: 551–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nestle FO, Banchereau J, and Hart D. 2001. Dendritic cells: On the move from bench to bedside. Nat Med 7: 761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni K, and O’Neill HC. 1997. The role of dendritic cells in T cell activation. Immunol Cell Biol 75: 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuler G, and Steinman RM. 1997. Dendritic cells as adjuvants for immune-mediated resistance to tumors. J Exp Med 186: 1183–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackensen A, Herbst B, Kohler G, Wolff-Vorbeck G, Rosenthal FM, Veelken H, Kulmburg P, Schaefer HE, Mertelsmann R, and Lindemann A. 1995. Delineation of the dendritic cell lineage by generating large numbers of Birbeck granule-positive Langerhans cells from human peripheral blood progenitor cells in vitro. Blood 86: 2699–2707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herbst B, Kohler G, Mackensen A, Veelken H, Kulmburg P, Rosenthal FM, Schaefer HE, Mertelsmann R, Fisch P, and Lindemann A. 1996. In vitro differentiation of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells toward distinct dendritic cell subsets of the birbeck granule and MIIC-positive Langerhans cell and the interdigitating dendritic cell type. Blood 88: 2541–2548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herbst B, Kohler G, Mackensen A, Veelken H, Mertelsmann R, and Lindemann A. 1997. CD34+ peripheral blood progenitor cell and monocyte derived dendritic cells: a comparative analysis. Br J Haematol 99: 490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caux C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Schmitt D, and Banchereau J. 1992. GM-CSF and TNF-alpha cooperate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans cells. Nature 360: 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caux C, Massacrier C, Vanbervliet B, Dubois B, Durand I, Cella M, Lanzavecchia A, and Banchereau J. 1997. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors from human cord blood differentiate along two independent dendritic cell pathways in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus tumor necrosis factor alpha: II. Functional analysis. Blood 90: 1458–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Draube A, Klein-Gonzalez N, Mattheus S, Brillant C, Hellmich M, Engert A, and von Bergwelt-Baildon M. 2011. Dendritic cell based tumor vaccination in prostate and renal cell cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 6: e18801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anguille S, Smits EL, Lion E, van Tendeloo VF, and Berneman ZN. 2014. Clinical use of dendritic cells for cancer therapy. Lancet Oncol 15: e257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjoa BA, Erickson SJ, Bowes VA, Ragde H, Kenny GM, Cobb OE, Ireton RC, Troychak MJ, Boynton AL, and Murphy GP. 1997. Follow-up evaluation of prostate cancer patients infused with autologous dendritic cells pulsed with PSMA peptides. Prostate 32: 272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy GP, Tjoa BA, Simmons SJ, Jarisch J, Bowes VA, Ragde H, Rogers M, Elgamal A, Kenny GM, Cobb OE, Ireton RC, Troychak MJ, Salgaller ML, and Boynton AL. 1999. Infusion of dendritic cells pulsed with HLA-A2-specific prostate-specific membrane antigen peptides: a phase II prostate cancer vaccine trial involving patients with hormone-refractory metastatic disease. Prostate 38: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, Sun Y, Grabbe S, Dummer R, Burg G, and Schadendorf D. 1998. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med 4: 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brossart P, Wirths S, Stuhler G, Reichardt VL, Kanz L, and Brugger W. 2000. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in vivo after vaccinations with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Blood 96: 3102–3108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thurner B, Haendle I, Roder C, Dieckmann D, Keikavoussi P, Jonuleit H, Bender A, Maczek C, Schreiner D, von den Driesch P, Brocker EB, Steinman RM, Enk A, Kampgen E, and Schuler G. 1999. Vaccination with mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed mature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J Exp Med 190: 1669–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dillman R, Selvan S, Schiltz P, Peterson C, Allen K, Depriest C, McClay E, Barth N, Sheehy P, de Leon C, and Beutel L. 2004. Phase I/II trial of melanoma patient-specific vaccine of proliferating autologous tumor cells, dendritic cells, and GM-CSF: planned interim analysis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 19: 658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dillman RO, Selvan SR, Schiltz PM, McClay EF, Barth NM, DePriest C, de Leon C, Mayorga C, Cornforth AN, and Allen K. 2009. Phase II trial of dendritic cells loaded with antigens from self-renewing, proliferating autologous tumor cells as patient-specific antitumor vaccines in patients with metastatic melanoma: final report. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 24: 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dillman RO, Cornforth AN, Depriest C, McClay EF, Amatruda TT, de Leon C, Ellis RE, Mayorga C, Carbonell D, and Cubellis JM. 2012. Tumor stem cell antigens as consolidative active specific immunotherapy: a randomized phase II trial of dendritic cells versus tumor cells in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother 35: 641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheikh NA, Petrylak D, Kantoff PW, Dela Rosa C, Stewart FP, Kuan LY, Whitmore JB, Trager JB, Poehlein CH, Frohlich MW, and Urdal DL. 2013. Sipuleucel-T immune parameters correlate with survival: an analysis of the randomized phase 3 clinical trials in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 62: 137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowenfeld L, Mick R, Datta J, Xu S, Fitzpatrick E, Fisher CS, Fox KR, DeMichele A, Zhang PJ, Weinstein SP, Roses RE, and Czerniecki BJ. 2017. Dendritic Cell Vaccination Enhances Immune Responses and Induces Regression of HER2(pos) DCIS Independent of Route: Results of Randomized Selection Design Trial. Clin Cancer Res 23: 2961–2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shinde P, Melinkeri S, Santra MK, Kale V, and Limaye L. 2019. Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cells Are a Preferred Source to Generate Dendritic Cells for Immunotherapy in Multiple Myeloma Patients. Front Immunol 10: 1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernhard H, Disis ML, Heimfeld S, Hand S, Gralow JR, and Cheever MA. 1995. Generation of immunostimulatory dendritic cells from human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells of the bone marrow and peripheral blood. Cancer Res 55: 1099–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gu YZ, Zhao X, and Song XR. 2020. Ex vivo pulsed dendritic cell vaccination against cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin 41: 959–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merck E, de Saint-Vis B, Scuiller M, Gaillard C, Caux C, Trinchieri G, and Bates EE. 2005. Fc receptor gamma-chain activation via hOSCAR induces survival and maturation of dendritic cells and modulates Toll-like receptor responses. Blood 105: 3623–3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akiyama K, Ebihara S, Yada A, Matsumura K, Aiba S, Nukiwa T, and Takai T. 2003. Targeting apoptotic tumor cells to Fc gamma R provides efficient and versatile vaccination against tumors by dendritic cells. J Immunol 170: 1641–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vanmeerbeek I, Sprooten J, De Ruysscher D, Tejpar S, Vandenberghe P, Fucikova J, Spisek R, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, and Garg AD. 2020. Trial watch: chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death in immuno-oncology. Oncoimmunology 9: 1703449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zitvogel L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Andre F, Tesniere A, and Kroemer G. 2008. The anticancer immune response: indispensable for therapeutic success? J Clin Invest 118: 1991–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlom J 2012. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: current status and moving forward. J Natl Cancer Inst 104: 599–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen G, and Emens LA. 2013. Chemoimmunotherapy: reengineering tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother 62: 203–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gabrilovich DI 2007. Combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy for cancer: a paradigm revisited. Lancet Oncol 8: 2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wheeler CJ, Das A, Liu G, Yu JS, and Black KL. 2004. Clinical responsiveness of glioblastoma multiforme to chemotherapy after vaccination. Clin Cancer Res 10: 5316–5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bracci L, Schiavoni G, Sistigu A, and Belardelli F. 2014. Immune-based mechanisms of cytotoxic chemotherapy: implications for the design of novel and rationale-based combined treatments against cancer. Cell Death Differ 21: 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, Fitzgibbons PL, Francis G, Goldstein NS, Hayes M, Hicks DG, Lester S, Love R, Mangu PB, McShane L, Miller K, Osborne CK, Paik S, Perlmutter J, Rhodes A, Sasano H, Schwartz JN, Sweep FC, Taube S, Torlakovic EE, Valenstein P, Viale G, Visscher D, Wheeler T, Williams RB, Wittliff JL, Wolff AC, O. American Society of Clinical, and P. College of American. 2010. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer (unabridged version). Arch Pathol Lab Med 134: e48–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, Dowsett M, Fitzgibbons PL, Hanna WM, Langer A, McShane LM, Paik S, Pegram MD, Perez EA, Press MF, Rhodes A, Sturgeon C, Taube SE, Tubbs R, Vance GH, van de Vijver M, Wheeler TM, Hayes DF, and P. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American. 2007. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med 131: 18–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gasparini G, Caffo O, Barni S, Frontini L, Testolin A, Guglielmi RB, and Ambrosini G. 1994. Vinorelbine is an active antiproliferative agent in pretreated advanced breast cancer patients: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 12: 2094–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Degardin M, Bonneterre J, Hecquet B, Pion JM, Adenis A, Horner D, and Demaille A. 1994. Vinorelbine (navelbine) as a salvage treatment for advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol 5: 423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weber BL, Vogel C, Jones S, Harvey H, Hutchins L, Bigley J, and Hohneker J. 1995. Intravenous vinorelbine as first-line and second-line therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 13: 2722–2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burstein HJ, Harris LN, Marcom PK, Lambert-Falls R, Havlin K, Overmoyer B, Friedlander RJ Jr., Gargiulo J, Strenger R, Vogel CL, Ryan PD, Ellis MJ, Nunes RA, Bunnell CA, Campos SM, Hallor M, Gelman R, and Winer EP. 2003. Trastuzumab and vinorelbine as first-line therapy for HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: multicenter phase II trial with clinical outcomes, analysis of serum tumor markers as predictive factors, and cardiac surveillance algorithm. J Clin Oncol 21: 2889–2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stathopoulos GP, Rigatos SK, Pergantas N, Tsavdarides D, Athanasiadis I, Malamos NA, and Stathopoulos JG. 2002. Phase II trial of biweekly administration of vinorelbine and gemcitabine in pretreated advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vincent BG, Young EF, Buntzman AS, Stevens R, Kepler TB, Tisch RM, Frelinger JA, and Hess PR. 2010. Toxin-coupled MHC class I tetramers can specifically ablate autoreactive CD8+ T cells and delay diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol 184: 4196–4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hunsucker SA, McGary CS, Vincent BG, Enyenihi AA, Waugh JP, McKinnon KP, Bixby LM, Ropp PA, Coghill JM, Wood WA, Gabriel DA, Sarantopoulos S, Shea TC, Serody JS, Alatrash G, Rodriguez-Cruz T, Lizee G, Buntzman AS, Frelinger JA, Glish GL, and Armistead PM. 2015. Peptide/MHC tetramer-based sorting of CD8(+) T cells to a leukemia antigen yields clonotypes drawn nonspecifically from an underlying restricted repertoire. Cancer Immunol Res 3: 228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li S, Lefranc MP, Miles JJ, Alamyar E, Giudicelli V, Duroux P, Freeman JD, Corbin VD, Scheerlinck JP, Frohman MA, Cameron PU, Plebanski M, Loveland B, Burrows SR, Papenfuss AT, and Gowans EJ. 2013. IMGT/HighV QUEST paradigm for T cell receptor IMGT clonotype diversity and next generation repertoire immunoprofiling. Nat Commun 4: 2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manso T, Folch G, Giudicelli V, Jabado-Michaloud J, Kushwaha A, Nguefack Ngoune V, Georga M, Papadaki A, Debbagh C, Pegorier P, Bertignac M, Hadi-Saljoqi S, Chentli I, Cherouali K, Aouinti S, El Hamwi A, Albani A, Elazami Elhassani M, Viart B, Goret A, Tran A, Sanou G, Rollin M, Duroux P, and Kossida S. 2022. IMGT(R) databases, related tools and web resources through three main axes of research and development. Nucleic Acids Res 50: D1262–D1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Team RC 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kassambara A, Kosinski M, and Biecek P. 2021. survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.4.9. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wickham H 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garnier S, Ross N, Rudis R, Camargo AP, Sciaini M, and Scherer C. 2021. Rvision - Colorblind-Friendly Color Maps for R. R package version 0.6.1. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Csardi G, and Nepusz T. 2006. The igraph software package for complex network research, InterJournal, Complex Systems 1695. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulz KF, Altman DG, and Moher D. 2010. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 1: 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Modi S, Jacot W, Yamashita T, Sohn J, Vidal M, Tokunaga E, Tsurutani J, Ueno NT, Prat A, Chae YS, Lee KS, Niikura N, Park YH, Xu B, Wang X, Gil-Gil M, Li W, Pierga JY, Im SA, Moore HCF, Rugo HS, Yerushalmi R, Zagouri F, Gombos A, Kim SB, Liu Q, Luo T, Saura C, Schmid P, Sun T, Gambhire D, Yung L, Wang Y, Singh J, Vitazka P, Meinhardt G, Harbeck N, and Cameron DA. 2022. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dees EC, McKinnon KP, Kuhns JJ, Chwastiak KA, Sparks S, Myers M, Collins EJ, Frelinger JA, Van Deventer H, Collichio F, Carey LA, Brecher ME, Graham M, Earp HS, and Serody JS. 2004. Dendritic cells can be rapidly expanded ex vivo and safely administered in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 53: 777–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Correlative study data will be provided to investigators at the publication of these data.