Abstract

Studies suggest a harmful pharmacogenomic interaction exists between short leukocyte telomere length (LTL) and immunosuppressants in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). It remains unknown if a similar interaction exists in non-IPF interstitial lung disease (ILD).

A retrospective, multi-centre cohort analysis was performed in fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, unclassifiable ILD, and connective tissue disease ILD patients from five centres. LTL was measured by qPCR for discovery and replication cohorts and expressed as age-adjusted percentiles of normal. Inverse probability of treatment weights based on propensity scores were used to assess the association between mycophenolate or azathioprine exposure and age-adjusted LTL on two-year transplant-free survival using weighted Cox proportional hazards regression incorporating time-dependent immunosuppressant exposure.

The discovery and replication cohorts included 613 and 325 patients, respectively. In total, 40% of patients were exposed to immunosuppression and 22% had LTL <10th percentile of normal. Fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable ILD patients with LTL <10th percentile experienced reduced survival when exposed to either mycophenolate or azathioprine in the discovery cohort (mortality HR 4.97, 95% CI 2.26–10.92, p<0.001) and replication cohort (mortality HR 4.90, 95% CI 1.74–13.77, p=0.003). Immunosuppressant exposure was not associated with differential survival in patients with LTL ≥10th percentile. There was a significant interaction between LTL <10th percentile and immunosuppressant exposure (Discovery p-interaction=0.013; Replication p-interaction=0.011). Low event rate and prevalence of LTL <10th percentile precluded subgroup analyses for connective tissue disease ILD.

Similar to IPF, fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable ILD patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile may experience reduced survival when exposed to immunosuppression.

Introduction

The interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a diverse group of inflammatory and fibrotic disorders that often require pharmacologic therapy to mitigate progressive loss of lung function. The initial treatment choice is primarily dictated by the ILD subtype. Antifibrotics are the preferred treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF),1,2 while immunosuppressants have been the mainstay for non-IPF ILDs including fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (fHP), unclassifiable ILD (uILD), and connective tissue disease ILD (CTD-ILD). Inaccurate ILD classification can result in suboptimal management for some patients; therefore, biomarkers that inform treatment selection irrespective of ILD subtype are needed.

Telomeres are 6-nucleotide repeats at ends of chromosomes that normally shorten with cellular replication and aging. Telomere dysfunction has been inexorably linked with ILD development and disease trajectory.3–12 Short leukocyte telomere length (LTL) has been found in 13–2% of patients with various ILDs and is consistently associated with reduced survival and rapid progression.13–21 For certain ILDs, there may also exist a pharmacogenomic relationship between short LTL and immunosuppressive therapies. We previously reported that historic use of immunosuppression was associated with worse survival for IPF patients with short age-adjusted LTL.21 We also described differential survival for fHP patients treated with mycophenolate when stratified by telomere quartiles.17 This current study seeks to expand these findings by examining a generalizable age-adjusted LTL percentile measurement across multiple cohorts, additional ILD subtypes, and other immunosuppressive therapies while accounting for potential immortal time bias in previous analyses.22

In this observational study, we examined fHP, CTD-ILD, and uILD patients from five academic ILD centres split into discovery and replication cohorts. Within each cohort, we explored the association between time-dependent exposure to mycophenolate or azathioprine and transplant-free survival in non-IPF ILD patients stratified by age-adjusted LTL in percentiles. We also assessed the longitudinal FVC trajectory across immunosuppression exposure and LTL groups.

Methods

Study populations:

Patients with fHP, uILD, and CTD-ILD were identified from the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW; 2003–2019), University of California San Francisco (UCSF; 2004–2017), University of California Davis (UCD; 2013–2017), University of Chicago (Chicago; 2001–2015), and Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC; 2019–2020). The institutional review boards for each centre approved this study. All patients provided written inform consent and a blood sample for research LTL measurement. LTL was independently assessed at UTSW/CUMC or UCSF, which comprised the discovery and replication cohorts. A portion of this cohort with fHP has been previously described.17

Eligible patients had non-IPF ILD diagnoses conferred through multidisciplinary discussion at each centre. Patients were excluded if baseline forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) measurements were unavailable, chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) did not demonstrate fibrosis per centre radiologist, were exposed to immunosuppressants (mycophenolate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab) or antifibrotics (pirfenidone, nintedanib) before blood collection for LTL measurement, or exposed to antifibrotics before immunosuppressants. Patients were grouped into immunosuppressant exposed (initiated on mycophenolate or azathioprine within two years of blood collection) or unexposed. Prednisone exposure was variable and largely coincided with other immunosuppressant exposure; therefore, patients were not excluded based on prednisone therapy to preserve sample size. Patients subsequently exposed to pirfenidone or nintedanib were censored at initiation of antifibrotic therapy.

Leukocyte Telomere Length

Genomic DNA was collected from leukocytes using Autopure LS (Qiagen; UTSW and CUMC), Gentra Puregene (Qiagen; UCSF and UCD), and Flexigene DNA kit (Qiagen; Chicago). All LTL were measured using a similar qPCR methodology at either UTSW/CUMC (discovery cohort) or UCSF (replication cohort) as previously reported.19,21,23,24 The UTSW and CUMC protocol was identical and performed by the same laboratory, so they were combined. Age-adjusted LTL was calculated by comparing observed to expected telomere length (Supplemental Methods) and dichotomized for comparative analyses: <10th percentile and ≥10th percentile of the reference population. Patients who underwent LTL measurement at both sites were included in the replication cohort only.

Statistical Analysis

Groups were compared using chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test, or one-way ANOVA, where appropriate. Relationships between continuous variables were examined using Pearson’s correlation.

Given the observational nature of the study, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using propensity scores was used to minimize indication bias and estimate the average treatment effect of immunosuppression across the entire cohort (Supplemental Methods). Propensity scores were generated using multivariable logistic regression to estimate the conditional probability of either mycophenolate or azathioprine exposure, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, family history of ILD, smoking status, baseline FVC and DLCO percent predicted, radiographic usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), prednisone exposure, ILD diagnosis, and centre. Weights were calculated by taking the inverse of the propensity score for immunosuppression-exposed patients and one minus the inverse of the propensity score for the unexposed; the weights were used to determine each patient’s contribution to a pseudo-population with balanced covariate distributions across treatment groups.25 Variables with standardized mean difference (SMD) >0.15 after weighting were considered unbalanced and included as covariates in outcome models. Given that prednisone exposure may similarly impact outcomes and is commonly used for non-IPF ILDs, a separate IPTW procedure was conducted for prednisone monotherapy using similar methods.

The primary aim was to determine if immunosuppression was associated with differential two-year transplant free-survival, defined as time from blood collection for LTL measurement to death or transplant, in patients stratified by the age-adjusted LTL 10th percentile. We constructed weighted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models with robust variance estimation (Supplemental Methods). Immunosuppressant exposure was treated as a time-dependent covariate to address immortal time bias, whereby patients initiated on mycophenolate or azathioprine during follow up were considered unexposed until drug start date. Models were adjusted for centre, radiographic honeycombing, and ILD diagnosis given residual imbalances after weighting and survival differences across diagnoses and presence of honeycombing.26,27 We assessed the pharmacogenomic interaction using an interaction term for LTL group and immunosuppressant exposure. The discovery and replication cohorts were analysed separately, then a meta-analysis across cohorts was performed using a random effects model. There was no evidence of non-proportional hazards which were examined by plotting Schoenfeld residuals versus time.

Multiple secondary survival analyses were performed. First, survival was assessed for each non-IPF ILD diagnosis using within-diagnoses meta-analysis of the discovery and replication cohorts. Second, we examined survival associations between immunosuppressant exposure and LTL percentile as a continuous variable. Third, we restricted the exposed cohort to patients initiated on immunosuppressants within one year of blood collection and had more than three months of exposure. Lastly, survival associations were individually assessed for mycophenolate and azathioprine. For this analysis, the propensity scores and IPTWs were calculated for each medication separately. For patients exposed to both medications sequentially, the first immunosuppressant drug was considered primary.

Longitudinal FVC trajectory was analysed using joint models incorporating survival and linear mixed effects submodels (Supplemental Methods).28,29 Both submodels were constructed similar to the primary survival model, including terms for immunosuppression exposure, LTL group, centre, radiographic honeycombing, and diagnosis. The linear mixed effects submodel also included terms for FVC, time, and an interaction term for FVC, time, and immunosuppression exposure. Immunosuppression exposed patients were included if they had ≥2 FVC measurements during exposure within 2 years of blood collection, while unexposed patients were included if they had ≥2 FVC measurements within 2 years of blood collection. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant; all analyses were performed using R statistical programming language, version 4.2.0 (www.r-project.org).

Results

Study Cohorts

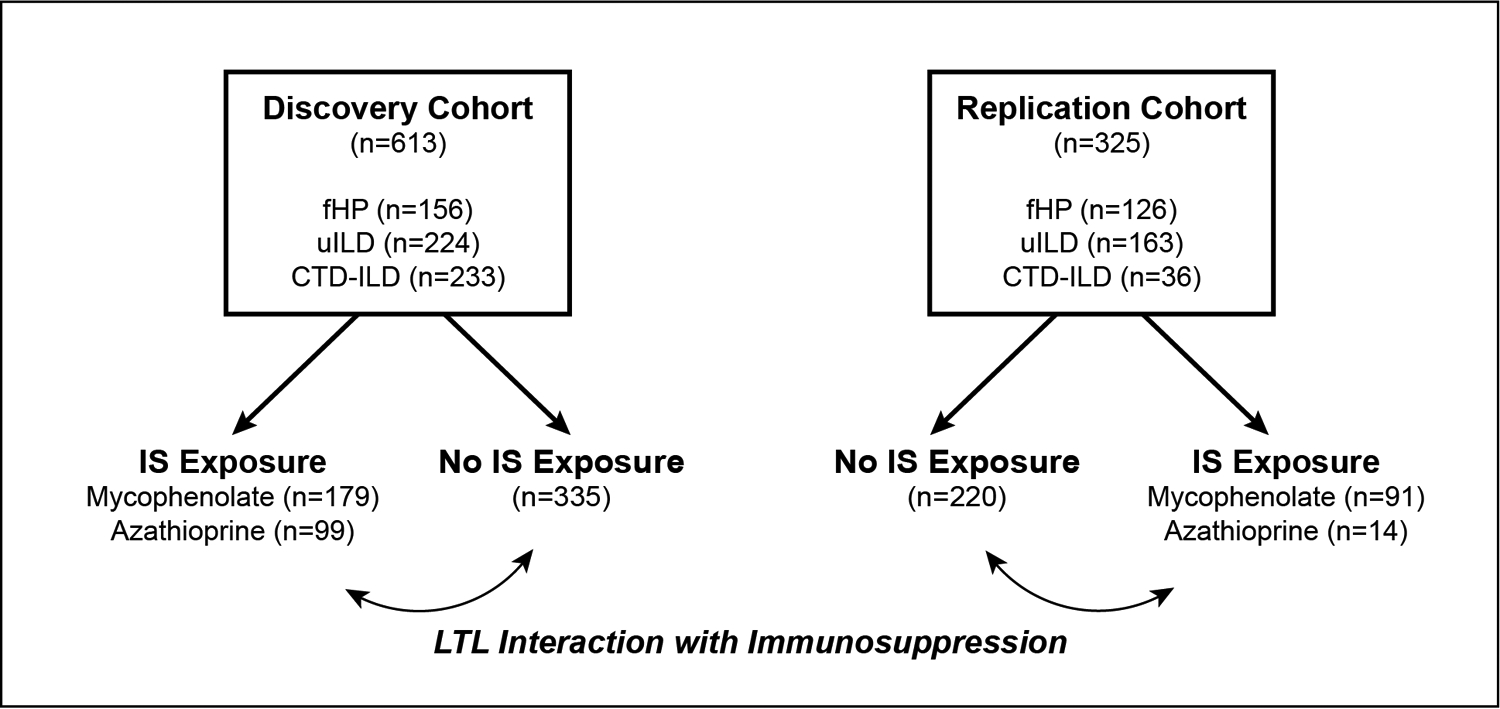

Of the 1332 non-IPF ILD patients identified across five centres, 938 met eligibility criteria, including 613 and 325 in the discovery and replication cohorts, respectively (Figure 1, Figure E1). CTD-ILD was the most common ILD subtype in the discovery cohort followed by uILD and fHP, while uILD was more common in the replication cohort followed by fHP and CTD-ILD (Table 1, Table 2). Among the CTD-ILDs, RA-ILD and scleroderma-related ILD were the most common diagnoses in both cohorts. The distribution of radiographic patterns and honeycombing differed by ILD subtype (Figure E2).

Figure 1:

STROBE diagram. Abbreviations: fHP, fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; CTD-ILD, connective tissue disease interstitial lung disease; uILD, unclassifiable interstitial lung disease; IS, immunosuppression; LTL, leukocyte telomere length

Table 1:

Unweighted and weighted discovery cohort patient characteristics stratified by immunosuppression exposure.

| Discovery Cohort | Weighted Discovery Cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS Exposed (N=278) | IS Unexposed (N=335) | P-value | IS Exposed (N=286) | IS Unexposed (N=332) | P-value | SMD | |

| Centre, n (%) | <0.01 | 0.62 | 0.13 | ||||

| UTSW | 171 (62) | 157 (47) | 138 (48) | 171 (51) | |||

| UCSF | 34 (12) | 51 (15) | 56 (19) | 50 (15) | |||

| Chicago | 69 (25) | 119 (36) | 88 (31) | 105 (32) | |||

| UCD | -- | -- | -- | -- | |||

| CUMC | 4 (1) | 8 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | |||

| ILD Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.10 | 0.91 | 0.04 | ||||

| fHP | 75 (27) | 81 (24) | 73 (25) | 83 (25) | |||

| CTD-ILD* | 114 (41) | 119 (36) | 107 (37) | 131 (39) | |||

| uILD | 89 (32) | 135 (40) | 106 (37) | 118 (36) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 60 (11) | 63 (12) | 0.01 | 62 (10) | 62 (12) | 0.93 | 0.01 |

| Male, n (%) | 113 (41) | 129 (39) | 0.65 | 109 (38) | 128 (39) | 0.93 | 0.01 |

| Ethnicity/Race, n (%) | 0.58 | 0.76 | 0.03 | ||||

| White | 204 (73) | 226 (68) | 196 (68) | 232 (70) | |||

| African American | 37 (13) | 59 (18) | 43 (15) | 59 (18) | |||

| Hispanic | 27 (10) | 37 (11) | 30 (10) | 32 (10) | |||

| Asian | 9 (3) | 12 (4) | 17 (6) | 9 (3) | |||

| Other† | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |||

| Ever Smoker, n (%) | 130 (47) | 178 (53) | 0.14 | 151 (53) | 172 (52) | 0.81 | 0.02 |

| Family History ILD, n (%) | 32 (12) | 31 (9) | 0.43 | 26 (9) | 31 (9) | 0.94 | 0.01 |

| Lung Function, mean (SD) | |||||||

| FVC % predicted | 62 (17) | 69 (20) | <0.01 | 66 (18) | 66 (19) | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| DLCO % predicted | 42 (19) | 48 (20) | <0.01 | 45 (19) | 45 (20) | 0.77 | 0.03 |

| Radiographic Features, n (%) | |||||||

| UIP | 54 (19) | 78 (23) | 0.29 | 61 (21) | 72 (22) | 0.92 | 0.01 |

| Honeycombing | 75 (27) | 121 (36) | 0.02 | 78 (27) | 112 (33) | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| IS Therapy, n (%) | |||||||

| Mycophenolate | 179 (64) | -- | -- | 184 (64) | -- | -- | -- |

| Azathioprine | 99 (36) | -- | -- | 102 (36) | -- | -- | -- |

| IS Exposure Years, median (IQR) | 1.7 (0.7, 2.0) | -- | -- | 1.9 (0.6, 2.0) | -- | -- | -- |

| Prednisone, n (%) | 231 (83) | 143 (43) | <0.01 | 169 (60) | 201 (61) | 0.77 | 0.03 |

| Leukocyte Telomere Length | |||||||

| LTL <10th percentile, n (%) | 57 (21) | 65 (19) | 0.81 | 51 (17) | 65 (20) | 0.52 | 0.06 |

| Age-adjusted LTL, median (IQR) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | 0.39 | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.1) | −0.1 (0.3, 0.1) | 0.55 | 0.06 |

| Follow-up Years, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.3, 2.0) | 0.73 | 2.0 (1.3, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.0) | 0.32 | <0.01 |

| Outcome, n (%) | |||||||

| Death within 2 years | 42 (15) | 31 (9) | 0.04 | 41 (14) | 29 (9) | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| Transplant within 2 years | 15 (5) | 5 (2) | 0.01 | 11 (4) | 4 (1) | 0.02 | 0.17 |

CTD-ILD diagnoses: scleroderma 63, rheumatoid arthritis 69, inflammatory myositis 36, mixed connective tissue disease 32, Sjogren’s syndrome 24, systemic lupus erythematosus 10

Other Ethnicity/Race: unknown 2

Radiograhic UIP incudes definite usual interstitial pneumonia

Abbreviations: LTL, leukocyte telomere length; IS, immunosuppression; SMD, standardized mean difference; UTSW, University of Texas Southwestern; UCSF, University of California San Francisco; CUMC, Columbia University Medical Center; ILD, interstitial lung disease; fHP, fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; CTD-ILD, connective tissue disease interstitial lung disease; uILD, unclassifiable interstitial lung disease; FVC, forced vital capacity, DLCO, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia

Table 2:

Unweighted and weighted replication cohort patient characteristics stratified immunosuppressant exposure and LTL group

| Replication Cohort | Weighted Replication Cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS Exposed (N=105) | IS Unexposed (N=220) | P-value | IS Exposed (N=112) | IS Unexposed (N=217) | P-value | SMD | |

| Cohort, n (%) | <0.01 | 0.24 | 0.28 | ||||

| UTSW | -- | -- | -- | -- | |||

| UCSF | 50 (48) | 120 (55) | 74 (66) | 117 (54) | |||

| Chicago | 14 (13) | 56 (26) | 14 (13) | 47 (22) | |||

| UCD | 41 (39) | 44 (20) | 24 (21) | 53 (24) | |||

| CUMC | -- | -- | -- | -- | |||

| ILD Diagnosis, n (%) | <0.01 | 0.70 | 0.13 | ||||

| fHP | 49 (47) | 77 (35) | 36 (32) | 84 (39) | |||

| CTD-ILD* | 18 (17) | 18 (8) | 14 (13) | 22 (10) | |||

| uILD | 38 (36) | 125 (57) | 62 (56) | 111 (51) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 63 (12) | 69 (10) | <0.01 | 68 (11) | 67 (11) | 0.58 | 0.11 |

| Male, n (%) | 49 (47) | 110 (50) | 0.66 | 54 (48) | 105 (49) | 0.98 | 0.01 |

| Ethnicity/Race, n (%) | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.03 | ||||

| White | 59 (56) | 143 (65) | 73 (65) | 137 (63) | |||

| African American | 20 (19) | 41 (19) | 17 (15) | 37 (17) | |||

| Hispanic | 16 (15) | 19 (9) | 12 (11) | 24 (11) | |||

| Asian | 6 (6) | 14 (6) | 8 (7) | 16 (8) | |||

| Other† | 4 (4) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (1) | |||

| Ever Smoker, n (%) | 46 (44) | 134 (61) | 0.01 | 73 (65) | 125 (57) | 0.51 | 0.11 |

| Family History ILD, n (%) | 13 (12) | 15 (7) | 0.14 | 11 (10) | 20 (9) | 0.84 | 0.04 |

| Lung Function, mean (SD) | |||||||

| FVC % predicted | 65 (16) | 71 (21) | <0.01 | 72 (16) | 70 (20) | 0.50 | 0.11 |

| DLCO % predicted | 50 (19) | 51 (21) | 0.62 | 50 (17) | 50 (21) | 0.85 | 0.03 |

| Radiographic UIP, n (%)† | |||||||

| UIP# | 8 (8) | 38 (17) | 0.03 | 10 (9) | 30 (14) | 0.41 | 0.12 |

| Honeycombing | 22 (21) | 56 (25) | 0.45 | 21 (19) | 45 (21) | 0.77 | 0.05 |

| IS Therapy, n (%) | |||||||

| Mycophenolate | 91 (87) | -- | -- | 99 (89) | -- | -- | -- |

| Azathioprine | 14 (13) | -- | -- | 13 (11) | -- | -- | -- |

| IS Exposure Years, median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.5, 2.0) | -- | -- | 1.7 (0.8, 2.0) | -- | -- | -- |

| Prednisone, n (%) | 87 (83) | 70 (32) | <0.01 | 50 (44) | 103 (48) | 0.72 | 0.07 |

| Leukocyte Telomere Length | |||||||

| LTL <10th percentile, n (%) | 21 (20) | 63 (29) | 0.13 | 26 (24) | 62 (29) | 0.61 | 0.12 |

| Age-adjusted LTL, median (IQR) | 0.2 (−0.3, 0.6) | 0.1 (−0.4, 0.5) | 0.12 | 0.1 (−0.3, 0.4) | 0.1 (−0.4, 0.5) | 0.75 | 0.03 |

| Follow-up Years, median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.1, 2.0) | 0.03 | 2.0 (2.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.0) | 0.34 | 0.23 |

| Outcome, n (%) | |||||||

| Death within 2 years | 17 (16) | 42 (19) | 0.63 | 21 (19) | 39 (18) | 0.95 | 0.01 |

| Transplant within 2 years | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 1.0 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.40 | 0.07 |

CTD-ILD diagnoses: scleroderma 19, rheumatoid arthritis 5, inflammatory myositis 6, mixed connective tissue disease 1, Sjogren’s syndrome 2, systemic lupus erythematosus 3

Other Ethnicity/Race: Middle Eastern 2, Native American 2, Pacific Islander 3

Radiograhic UIP incudes definite usual interstitial pneumonia

Abbreviations: LTL, leukocyte telomere length; IS, immunosuppression; SMD, standardized mean difference; UCSF, University of California San Francisco; ILD, interstitial lung disease; fHP, fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; CTD-ILD, connective tissue disease interstitial lung disease; uILD, unclassifiable interstitial lung disease; FVC, forced vital capacity, DLCO, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia

In the discovery cohort, 45% of patients were exposed to either mycophenolate or azathioprine within two years of blood collection (Table 1), while only 32% were exposed in the replication cohort (p<0.001) (Table 2). Exposure rates were similar between the discovery and replication cohorts for CTD-ILD (49% versus 50%, p=1.0) and fHP (48% versus 39%, p=0.15), but not uILD (40% versus 23%, p<0.001). Over 80% of patients from both cohorts were initiated on immunosuppressants within 1 year of blood collection (Figure E3); median time to immunosuppressant initiation was 0.1 years (IQR 0.0–0.5) and 0.2 (IQR 0.0–0.7) and median exposure time was 1.7 years (IQR 0.7–2.0) and 1.5 years (IQR 0.5–2.0) in the discovery and replication cohorts, respectively. Baseline differences between immunosuppressant exposed and unexposed patients, including age, severity of lung function impairment, and radiographic features were balanced (SMD <0.15) with propensity score weighting to account for indication bias; however, centre remained imbalanced in the replication cohort (Figure E4).

Leukocyte Telomere Length

Continuous age-adjusted LTL was shorter in the discovery cohort (−0.09, IQR −0.26, 0.09) than the replication cohort (0.09, IQR −0.34, 0.55, p<0.001) (Figure E5). When dichotomizing LTL, more patients in the replication cohort had LTL <10th percentile (26% versus 20%, p=0.04). The prevalence of LTL <10th percentile was highest in uILD (33%) followed by fHP (28%) and CTD-ILD (12%) (Figure E6). In contrast, over 80% of CTD-ILD patients had LTL >50th percentile compared to 41% of fHP and 45% of uILD patients. The presence of radiographic UIP or honeycombing were more prevalent in patients with LTL <10th percentile (Table E1). Of the patients with LTL <10th percentile, 47% and 25% were exposed to immunosuppression in the discovery and replication cohorts, respectively. The correlation of 40 individual LTL measurements performed at both UTSW/CUMC and USCF was found to be in high agreement across sites (r=0.86, p<0.001) (Figure E7).

Transplant-free survival

Two-year transplant-free survival was similar for the discovery and replication cohorts (p=0.19) and across centres (p=0.95) (Figure E8). Patients with CTD-ILD had better survival than fHP (p<0.001) or uILD (p<0.001). Radiographic honeycombing, but not radiographic UIP, was associated with reduced two-year transplant free survival in adjusted analyses (Table E2). Compared to unexposed patients, neither mycophenolate (HR 1.47, 95% CI 0.88–2.46, p=0.14) nor azathioprine (HR 1.67, 95% CI 0.83–3.36, p=0.15) exposure was associated with differential two-year transplant-free survival. There was also no survival difference between mycophenolate and azathioprine exposure (p=0.22).

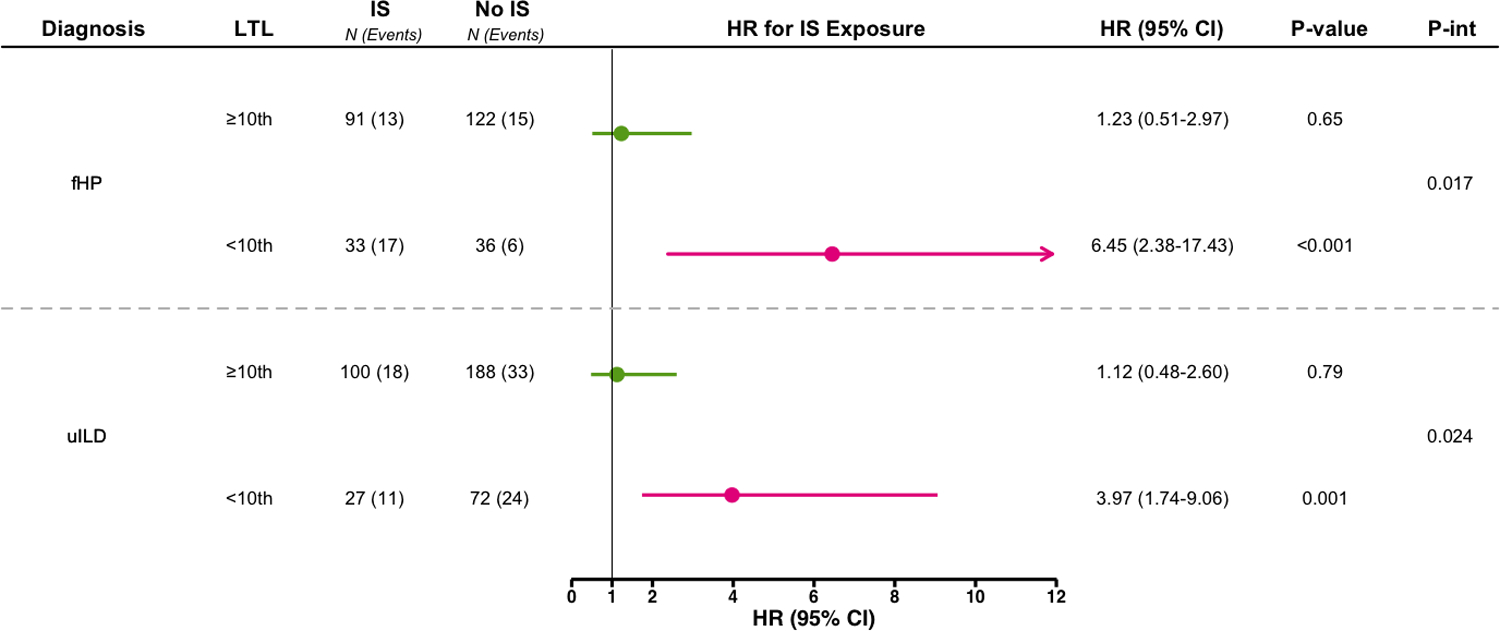

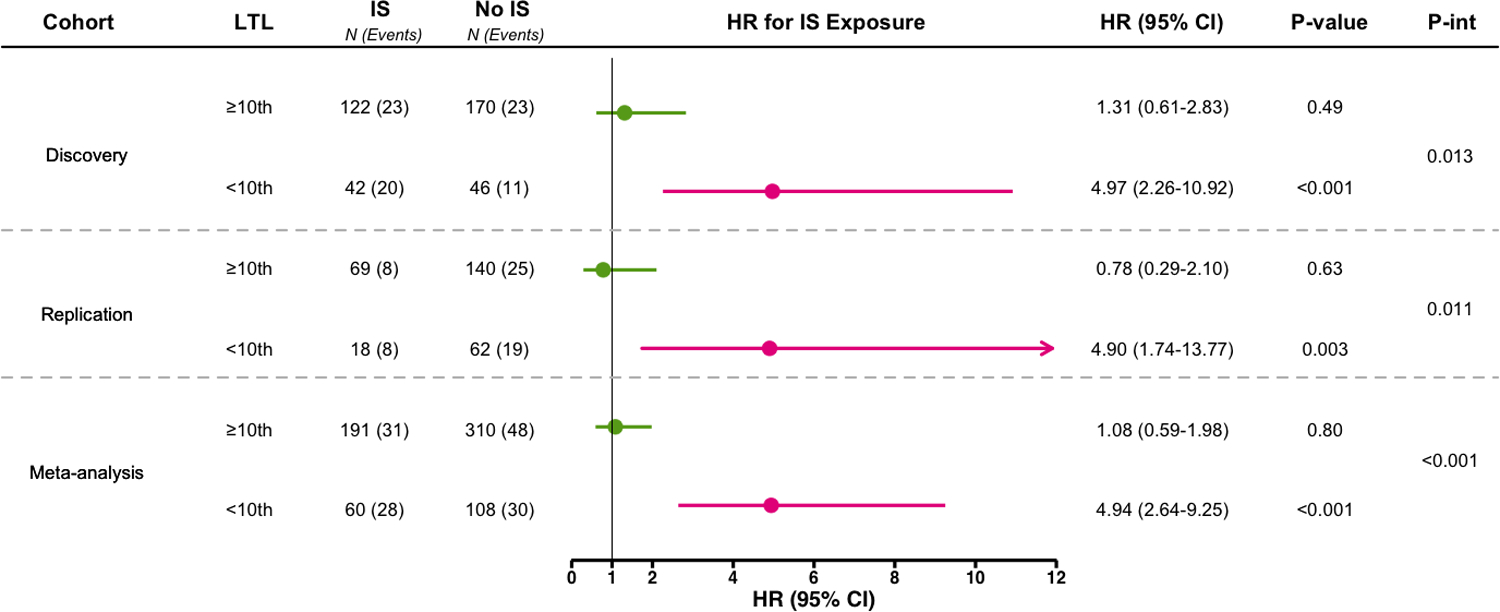

Immunosuppressant exposure was associated with worse two-year transplant-free survival for both fHP and uILD patients with LTL <10th percentile, but not those with LTL ≥10th percentile (Figure 2). In CTD-ILD patients, the low two-year event rate (6%) and prevalence of LTL <10th percentile (12%) precluded meaningful subgroup survival analyses. In the combined analysis of fHP and uILD, patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile, immunosuppressant exposure was associated with worse transplant-free survival in both discovery (HR 4.97, 95% CI 2.26–10.92, p<0.001) and replication cohorts (HR 4.90, 95% CI 1.74–13.77, p=0.003; meta-analysis HR 4.94, 95% CI 2.64–9.25, p<0.001) (Figure 3). Immunosuppression was not associated with survival in fHP and uILD patients with LTL ≥10th percentile (pooled meta-analysis: HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.59–1.98). There was a significant interaction between immunosuppressant exposure and LTL 10th percentile (discovery p-interaction=0.013, replication p-interaction=0.011, meta-analysis p-interaction<0.001) for patients with fHP and uILD.

Figure 2.

Association between immunosuppression exposure (mycophenolate or azathioprine) compared to no exposure and two-year transplant-free survival in fHP and uILD patients stratified by age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length above and below the 10th percentile of normal. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model with robust variance estimation and adjustment for radiographic honeycombing and centre. Abbreviations: fHP, fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; uILD, unclassifiable interstitial lung disease; LTL, leukocyte telomere length; IS, immunosuppression; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; P-int, p-interaction.

Figure 3.

Association between immunosuppression exposure (mycophenolate or azathioprine) and two-year transplant-free survival in combined fHP and uILD patients stratified by age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length above and below the 10th percentile of normal. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model with robust variance estimation and adjustment for non-IPF ILD diagnosis, radiographic honeycombing, and centre. Abbreviations: LTL, leukocyte telomere length; IS, immunosuppression; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; P-int, p-interaction.

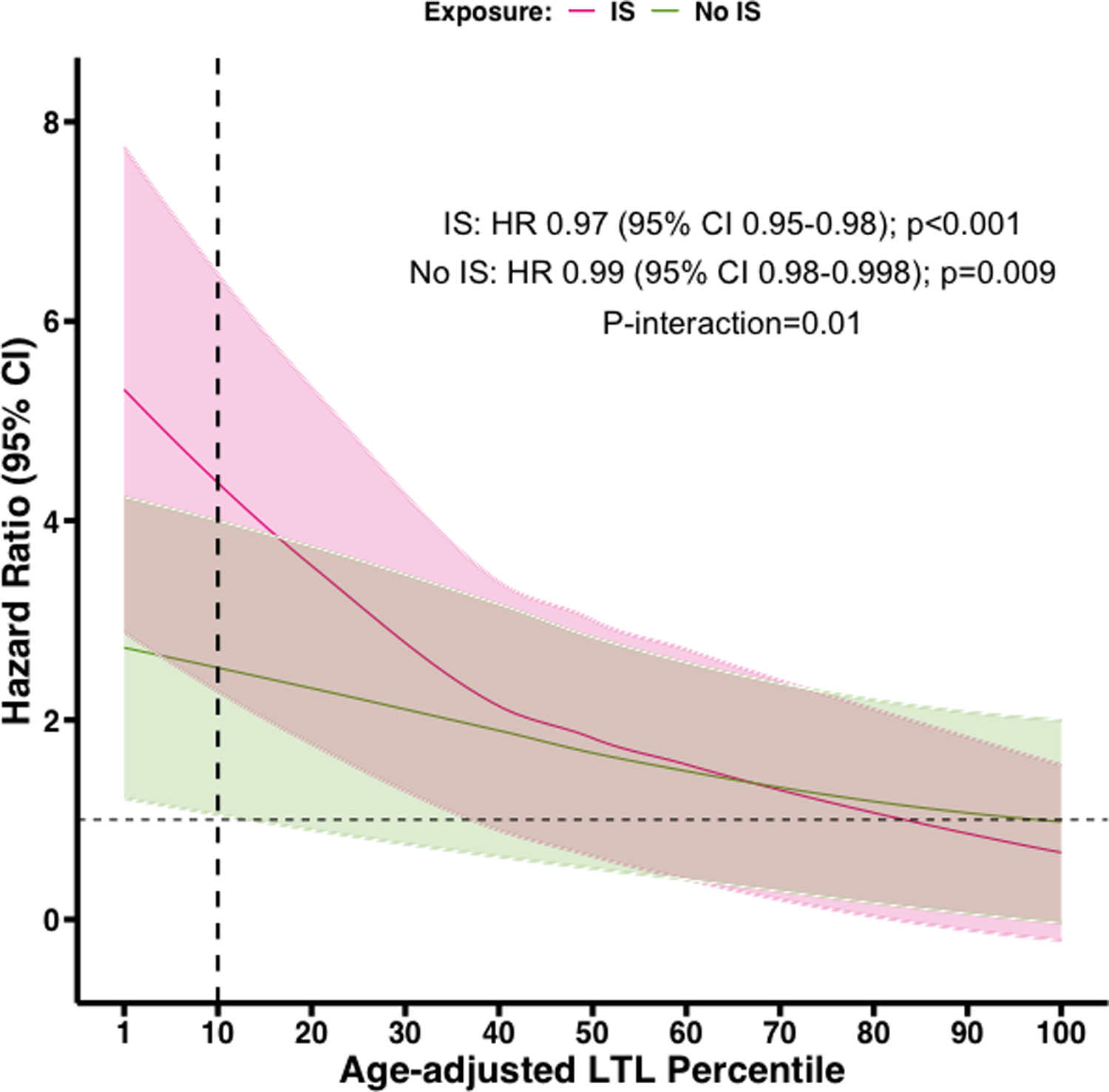

Sensitivity analyses using age-adjusted LTL percentile as a continuous variable confirmed that shorter LTL was associated with worse survival overall regardless of exposure, but this detrimental association was magnified by immunosuppression treatment (p-interaction=0.01) for fHP and uILD patients (Figure 4). In a subset of fHP and uILD patients initiated on immunosuppression within one year of blood collection and had more than three months of exposure, immunosuppression was similarly associated with reduced survival in those with LTL <10th percentile (Figure E9). Both mycophenolate and azathioprine individually were associated with reduced transplant-free survival in fHP and uILD patients with LTL <10th percentile; however, the interaction between LTL and azathioprine exposure was inconsistent (Figure E10). Prednisone monotherapy was not associated with differential two-year transplant-free survival for non-IPF ILD patients with LTL <10th percentile or LTL ≥10th percentile (Table E3).

Figure 4.

Association between immunosuppression exposure and age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length percentile as a continuous variable for fHP and uILD patients. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model with robust variance estimation and adjustment for non-IPF ILD diagnosis, radiographic honeycombing, and centre. Abbreviations: LTL, leukocyte telomere length; IS, immunosuppression; CI, confidence interval.

Longitudinal FVC Trajectory

There were 286 immunosuppressant exposed (201 mycophenolate, 85 azathioprine) and 251 unexposed patients from both cohorts included in this analysis. The median FVC measurement timespan was similar between exposed (1.17 years, IQR 0.55–1.71) and unexposed patients (1.27 years, IQR 0.68–1.65, p=0.75). The annualized rate of FVC change over two years did not differ by study cohort or ILD subtype (Table E4). Immunosuppression exposure was not associated with differential FVC change (exposed: −60 ml/year, 95% CI −91, −30 versus unexposed: −83 ml/year; 95% CI −116, −50; p=0.32). Patients with LTL <10th percentile experienced faster FVC decline (−125 ml/year; 95% CI −178, −72) than those with LTL ≥10th percentile (−59 ml/year; 95% CI −84, −35; p=0.027). However, neither the composite (Table 3) nor the individual immunosuppressant medications (Table E5) were associated with differential FVC trajectory in patients stratified by the age-adjusted LTL 10th percentile threshold.

Table 3.

Annualized change in forced vital capacity for non-IPF ILD patients stratified by immunosuppression exposure and age-adjusted LTL above and below the 10th percentile of normal.

| Immunosuppression Exposed | Immunosuppression Unexposed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (N FVC) | Δ FVC, ml/year (95% CI)* | N (N FVC) | ΔFVC, ml/year (95% CI)* | P-value | |

| LTL <10th | 55 (209) | −141 (−218, −65) | 56 (177) | −111 (−184, −39) | 0.58 |

| LTL ≥10th | 231 (978) | −46 (−79, −12) | 195 (673) | −76 (−113, −39) | 0.23 |

Joint-model incorporating time-to-event and linear mixed-effects submodels, adjusted for ILD diagnosis, radiographic honeycombing, and ILD centre. Restricted to patients with ≥2 FVC measures while on immunosuppression within two-years of blood collection for exposed patients, and ≥2 FVC measures within two-years of blood collection for unexposed patients

Abbreviations: FVC, forced vital capacity, CI, confidence interval; LTL, leukocyte telomere length

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of commonly used immunosuppressants on two-year transplant-free survival in non-IPF ILD patients stratified by age-adjusted LTL percentiles. We found that immunosuppressant exposure was associated with reduced survival for fHP and uILD patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile. However, the study was underpowered to examine the survival associations between immunosuppression exposure and age-adjusted LTL for CTD-ILD patients. In addition, LTL <10th percentile was associated with faster FVC decline independent of immunosuppressant exposure. These data suggest that commonly used immunosuppressants may be associated with higher mortality risk, but not progressive lung function decline, in a subset of fHP and uILD patients.

Over the last decade, ILD treatment strategy has shifted from near universal use of immunosuppressants to thoughtful medication selection guided by ILD subtype. Based on high-quality studies, an IPF diagnosis mandates avoidance of immunosuppressants in favour of antifibrotics.1,2,30 In contrast, treatment selection and timing in non-IPF ILDs is highly variable.

Immunosuppressants have been a common therapeutic option for non-IPF ILD patients requiring therapy based on limited clinical trials and observational studies.31−35 However, monitoring for progression without therapy may be appropriate for some non-IPF ILD patients.36 In this study, 60% of patients were not initiated on therapy during the two-year follow-up. Therefore, there is an urgent need for biomarkers that can identify high-risk patients and inform their treatment strategy. Given the current data, we propose that LTL may serve both functions.

We confirm prior studies demonstrating that non-IPF ILD patients with short LTL are at high risk of progression, experience worse mortality, and may benefit from earlier treatment.13–20 While LTL testing for IPF patients may similarly aid in prognostication, it is unlikely to inform treatment selection since antifibrotics appear safe and effective in patients with telomere dysfunction.10,37 However, we find that LTL may allow personalized management for some non-IPF ILDs. Our study found that immunosuppression exposure was associated with higher mortality risk in fHP and uILD patients with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile. While prospective studies are needed, our findings suggest that LTL testing may inform treatment selection whereby immunosuppressants should be considered with caution in fHP and uILD patients with LTL <10th percentile.

The current study differs from our prior report examining the differential impact of mycophenolate for fHP patients stratified by LTL quartiles in multiple ways. First, we applied age-adjusted LTL percentiles that are generalizable outside of our study cohort. Second, we dichotomized by age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile as a biologically relevant threshold; prior studies demonstrated this threshold to be sensitive to detecting carriers with pathogenic telomere gene mutations.5 However, immunosuppression exposure was associated with higher mortality risk across the continuum of LTL percentiles, driven by the shortest LTLs. Third, we mitigated immortal time bias22 by enrolling at time of LTL measurement and modelled immunosuppression exposure as a time-dependent covariate.38 Using this approach, we found that mycophenolate was not associated with favourable survival in any subpopulation and was associated with worse outcomes in those with LTL <10th percentile. Lastly, the current study expanded the size and scope of the analysis to include additional ILD subtypes and immunosuppressants in additional cohorts. These efforts uncovered a significant interaction between short LTL and immunosuppression exposure for fHP and uILD patients, whereby immunosuppression exposure was associated with higher mortality risk for those with age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile.

We also found important differences across the non-IPF ILD subtypes included in this study. While the phenotypic heterogeneity within the CTDs may have may have limited this subgroup analysis, there were also fewer events and lower prevalence of short telomeres that limited the assessment of an immunosuppression and LTL interaction. In contrast to CTD-ILD, the fHP and uILD cohorts had a higher prevalence of LTL <10th percentile, which approached the level seen in IPF cohorts.20 In addition, the current study found that radiographic UIP and honeycombing were present in a higher proportion of non-IPF ILD patients with LTL <10th percentile, similar to a prior study in fHP patients.15 However, the effect of these “UIP-like” features on survival was smaller than the effect of LTL, and neither UIP nor honeycombing modified the impact of immunosuppression on survival. Therefore, the current data suggests that short LTL may predispose to a “UIP-like” phenotype, but the short LTL confers a greater impact on survival that may be further magnified by immunosuppressive therapies.

Immunosuppression exposure was not associated with differential FVC decline in non-IPF ILD patients with LTL <10th percentile suggesting a harmful effect unrelated to progressive lung fibrosis. Immunosuppressants are associated with non-pulmonary complications in lung transplant recipients with short LTL or telomere gene mutations.39–42 These medications may unmask extrapulmonary short telomere syndrome manifestations, including bone marrow suppression and impaired adaptive immunity,43,44 tipping the balance toward harmful inhibition of protective immunity without causing progressive lung function decline. Prospective studies with systematic evaluation of pulmonary and non-pulmonary effects of immunosuppressants are needed.

The current study has limitations. First, this retrospective study demonstrates associations but not causal links. Future clinical trials are needed to validate these findings and inform clinical practice. Second, we accounted for indication bias by using measured variables that influence immunosuppression exposure to generate weighted propensity scores. Using this approach, we were able to balance the distribution of important covariates such as age, sex, severity of disease and radiographic patterns across exposure groups thus limiting their influence on effect estimates. However, given the non-randomized nature of this study, we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured effects impacting our results. Third, subsetting the relatively large total cohort reduced the effective sample size and may have led to imprecision. However, similar directions and magnitude of effects were seen across secondary analysis, increasing confidence that the associations may approach reality. Fourth, we used banked genomic DNA to measure LTL by qPCR at two sites, which may have introduced variability in the LTL measurement, although the correlation between site measurements was high. Given the potential for LTL variability across sites, we chose to perform meta-analysis of the two cohorts, instead of combining. Next, only fibrotic ILDs were included so it remains unknown if a similar interaction exists in non-fibrotic ILDs. Lastly, we were unable to systematically assess immunosuppressant-related adverse effects due to the non-standardized follow up or the impact of other ILD treatments due to lower usage in the cohorts.

Conclusions

By identifying a harmful pharmacogenomic interaction between LTL <10th percentile and mycophenolate or azathioprine exposure, we demonstrate that LTL may be a clinically viable genomic marker to aid treatment decisions for fHP and uILD patients. The findings should form the basis for prospective validation studies to determine if LTL-informed personalized treatment selection improves outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Take home message:

Fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable ILD patients who have age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length <10th percentile may experience reduced survival when exposed to immunosuppression, similar to IPF patients.

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to all participating patients and research staff that assisted with patient recruitment, data collection, and technical analyses (Leslie Vickers at Columbia University Medical Center; Jane Berkeley at University of California San Francisco).

Funding:

National Institutes of Health includes K23HL146942 (AA), K23HL138190 and R56HL158935 (JMO), UG3HL145266 (IN), R01HL093096 (CKG), K23HL148498 and UL1TR001105 (CAN); Stony Wold-Herbert Fund and Parker B. Francis Foundation (DZ), Nina Ireland Program for Lung Health (PJW)

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

JK, NG, MP, RS, ALL, BL, SFM have nothing to disclose. DZ reports consulting fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim grant support from the Stony Wold-Herbert Fund and Parker B. Francis Foundation. AA reports consulting fees from Genentech, Inogen, Medscape, PatientMpower, Boehringer-Ingelheim and grant support from NHLBI. JO reports consulting fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lupin Pharmaceuticals, AmMax Bio, Roche, Veracyte and grant support from NHLBI. IN reports consulting fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Sanofi and grant support from Veracyte and NIH. MES reports honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Fibrogen, American College of Chest Physicians, and grant support from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation. PJW reports grant support from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Roche, Sanofi, Pliant, NIH, and consulting fees from Blade Therapeutics. CKG reports grant support from NIH, DOD, Boehringer-Ingelheim. CAN reports consulting fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim and grant support from NHLBI.

References:

- 1.King TE Jr., Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine 2014;370:2083–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine 2014;370:2071–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, et al. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:7552–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine 2007;356:1317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart BD, Choi J, Zaidi S, et al. Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nat Genet 2015;47:512–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannengiesser C, Borie R, Menard C, et al. Heterozygous RTEL1 mutations are associated with familial pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2015;46:474–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cogan JD, Kropski JA, Zhao M, et al. Rare variants in RTEL1 are associated with familial interstitial pneumonia. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2015;191:646–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrovski S, Todd JL, Durheim MT, et al. An Exome Sequencing Study to Assess the Role of Rare Genetic Variation in Pulmonary Fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2017;196:82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ley B, Torgerson DG, Oldham JM, et al. Rare Protein-Altering Telomere-related Gene Variants in Patients with Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2019;200:1154–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dressen A, Abbas AR, Cabanski C, et al. Analysis of protein-altering variants in telomerase genes and their association with MUC5B common variant status in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a candidate gene sequencing study. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:603–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:13051–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duckworth A, Gibbons MA, Allen RJ, et al. Telomere length and risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuart BD, Lee JS, Kozlitina J, et al. Effect of telomere length on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an observational cohort study with independent validation. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:557–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai J, Cai H, Li H, et al. Association between telomere length and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2015;20:947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ley B, Newton CA, Arnould I, et al. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism and telomere length in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an observational cohort-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:639–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Zhuang Y, Peng H, et al. The relationship between MUC5B promoter, TERT polymorphisms and telomere lengths with radiographic extent and survival in a Chinese IPF cohort. Sci Rep 2019;9:15307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adegunsoye A, Morisset J, Newton CA, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and mycophenolate therapy in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Eur Respir J 2021;57:2002872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ley B, Liu S, Elicker BM, et al. Telomere length in patients with unclassifiable interstitial lung disease: a cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Chung MP, Ley B, et al. Peripheral blood leucocyte telomere length is associated with progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Thorax 2021;76:1186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newton CA, Oldham JM, Ley B, et al. Telomere length and genetic variant associations with interstitial lung disease progression and survival. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newton CA, Zhang D, Oldham JM, et al. Telomere Length and Use of Immunosuppressive Medications in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2019;200:336–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diaz de Leon A, Cronkhite JT, Katzenstein AL, et al. Telomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutations. PLoS One 2010;5:e10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faust HE, Golden JA, Rajalingam R, et al. Short lung transplant donor telomere length is associated with decreased CLAD-free survival. Thorax 2017;72:1052–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34:3661–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Bellam SK, et al. CT Honeycombing Identifies a Progressive Fibrotic Phenotype with Increased Mortality Across Diverse Interstitial Lung Diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryerson CJ, Urbania TH, Richeldi L, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of unclassifiable interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2013;42:750–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowther MJ, Abrams KR, Lambert PC. Flexible parametric joint modelling of longitudinal and survival data. Stat Med 2012;31:4456–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogan JW, Laird NM. Model-based approaches to analysing incomplete longitudinal and failure time data. Stat Med 1997;16:259–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research N, Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr., Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine 2012;366:1968–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. The New England journal of medicine 2006;354:2655–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:708–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morisset J, Johannson KA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Use of mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine for the management of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2016;151:619–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Fernandez Perez ER, et al. Outcomes of immunosuppressive therapy in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. ERJ open research 2017;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldham JM, Lee C, Valenzi E, et al. Azathioprine response in patients with fibrotic connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Respir Med 2016;121:117–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2022;205:e18–e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Justet A, Klay D, Porcher R, et al. Safety and efficacy of pirfenidone and nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and carrying a telomere-related gene mutation. Eur Respir J 2021;57:2003198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suissa S, Suissa K. Antifibrotics and Reduced Mortality in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Immortal Time Bias. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2023;207:105–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borie R, Kannengiesser C, Hirschi S, et al. Severe hematologic complications after lung transplantation in patients with telomerase complex mutations. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:538–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Courtwright AM, Lamattina AM, Takahashi M, et al. Shorter telomere length following lung transplantation is associated with clinically significant leukopenia and decreased chronic lung allograft dysfunction-free survival. ERJ open research 2020;6:00003–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton CA, Kozlitina J, Lines JR, Kaza V, Torres F, Garcia CK. Telomere length in patients with pulmonary fibrosis associated with chronic lung allograft dysfunction and post-lung transplantation survival. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:845–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tokman S, Singer JP, Devine MS, et al. Clinical outcomes of lung transplant recipients with telomerase mutations. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:1318–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popescu I, Mannem H, Winters SA, et al. Impaired Cytomegalovirus Immunity in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Lung Transplant Recipients with Short Telomeres. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2019;199:362–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang P, Leung J, Lam A, et al. Lung transplant recipients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have impaired alloreactive immune responses. J Heart Lung Transplant 2022;41:641–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.