Abstract

Dlx5 and Dlx6 homeobox genes are expressed in developing and mature cortical interneurons. Simultaneous deletion of Dlx5 and 6 results in exencephaly of the anterior brain; despite this defect, prenatal basal ganglia differentiation appeared largely intact, while tangential migration of Lhx6+ and Mafb+ interneurons to the cortex was reduced and disordered. The migration deficits were associated with reduced CXCR4 expression. Transplantation of mutant immature interneurons into a wild type brain demonstrated that loss of either Dlx5, or Dlx5&6, preferentially reduced the number of mature parvalbumin+ interneurons; those parvalbumin+ interneurons that were present had increased dendritic branching es. Dlx5/6+/- mice, which appear normal histologically, show spontaneous electrographic seizures, and reduced power of gamma oscillations. Thus, Dlx5&6 appeared to be required for development and function of somal innervating (parvalbumin+) neocortical interneurons. This contrasts with Dlx1, whose function is required for dendrite innervating (calretinin+, somatostatin+ and neuropeptide Y+) interneurons (Cobos et al., 2005).

Keywords: Dlx5, Dlx6, Cortical Interneuron, Parvalbumin, Transplantation, Subtype Specification

Introduction

Most rodent cortical interneurons are derived from progenitor domains in the prenatal subcortical telencephalon (subpallium) (Marin et al., 2003; Flames and Marin, 2005). The subpallium consists of four major subdivisions that have distinct molecular and morphological features: the lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), medial ganglionic eminence (MGE), septum (SE) and preoptic area (POA). Moreover, caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE) exists as a caudal fusion of the MGE and LGE with distinct molecular domains that resemble caudal extensions of the MGE and LGE (Long et al., 2007).

The MGE is the source of the majority of interneurons that express parvalbumin (PV) and somatostatin (SST). On the other hand, there are at least two types of calretinin+ and neuropeptide Y (NPY)+ interneurons: those expressing somatostatin are thought to derive from the MGE, and those that don't express somatostatin are thought to mainly derive from the CGE (Sussel et al., 1999; Pleasure et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2004; Butt et al., 2005; Wonders and Anderson, 2006; Flames et al., 2007; Fogarty et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2008). Flames et al. (2007) found that dorsal and ventral subdivisions of the MGE produce different ratios of cortical interneuron subtypes; dorsal regions preferentially produce SST+, whereas ventral regions preferentially produce PV+. They correlated this with molecular features of the MGE to provide insights for a transcription factor code in generating distinct neocortical interneuron subtypes.

Information about the transcriptional control of interneuron development has come from the analysis of Arx, Dlx1&2, Dlx1, Lhx6, and Nkx2.1 mutants. Most interneurons require Dlx1&2 (Anderson et al., 1997a; Anderson et al., 1997b; Yun et al., 2002; Cobos et al., 2006; Long et al., 2007)Long et al., 2009a,b). Dlx1/2-/- mutants have a severe deficit in the survival and migration of immature cortical and hippocampal interneurons. While Dlx1 is widely expressed in immature interneurons, its postnatal expression is only detectable in subsets of SST+, NPY+ and most CR+ interneurons, where it is required for their survival (Cobos et al., 2005; Cobos et al., 2006; Cobos et al., 2007). Virtually all PV+ and SST+ interneurons, and subsets of CR+ and NPY+ interneurons, depend on expression of Nkx2.1 and Lhx6 (Sussel et al., 1999; Pleasure et al., 2000; Liodis et al., 2007; Du et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2008). Dlx1/2-/- and Lhx6-/- have reduced Arx expression. (Cobos et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2008). Arx mutants have reduced interneuron migration (Kitamura et al., 2002; Colasante et al., 2008) (Colombo et al., 2007; Fulp et al., 2008). While the function of Dlx1 and Dlx2 in telencephalic development has been well established, the function of Dlx5 and Dlx6 is just beginning to be elucidated. Dlx5 is known to promote differentiation of olfactory bulb interneurons (Levi et al., 2003; Long et al., 2003); no information is available on Dlx6 function. Because Dlx1&2 are required to induce expression of Dlx5&6 in the LGE and MGE subventricular zones (Anderson et al., 1997a; Zerucha et al., 2000; Long et al., 2007), it is unclear to what extent the Dlx1/2-/- phenotype reflects loss of Dlx1&2 or Dlx1,2,5&6 function. Here we present the first evidence that Dlx5 and Dlx5&6 are required for development and function of neocortical PV+ interneurons.

Materials and Methods

Animals and tissue preparation

Dlx5 and Dlx5&6 loss of function mutant mice were previously described (Depew et al., 1999; Robledo et al., 2002). Lhx6-GFP and Dlx5-GFP BAC transgenic mouse line were obtained from GENSAT (http://www.gensat.org/index.html). Dlx5/6i-Cre mice were also previously described (Kohwi et al., 2007). For staging of embryos, midday of the vaginal plug was calculated as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Mouse colonies were maintained in accordance with the protocols approved by the Committee on Animal Research at University of California, San Francisco. Embryos were anesthetized by cooling, dissected, and immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 4–12 h. Samples were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose and cut 20um using a cryostat.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization experiments were performed using digoxigenin riboprobes on 20 μm frozen sections as described previously. Briefly, slides were fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min, treated with proteinase K (1 μg/ml) for 15 min. Acetylation was performed using 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamine, pH 8.0, for 10 min, followed by three PBS washes. Slides were incubated with hybridization buffer for 2 hours at RT, followed by overnight incubation with a digoxigenin-labeled probe at 72°C. Three high-stringency washes were performed with 0.2× SSC at 72°C. Slides were then incubated with horseradish alkaline phosphatase -conjugated anti-digoxigenin and NBT (nitroblue tetrazolium)/BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-indolyl phosphate) for signal detection. The probes used and their sources were as follows: Cxcl12 (Sam Pleasure), Cxcr4 (Dan Littman), Cxcr7 (RDC1) (ATCC MGC-18378), Dlx1, Dlx2 (J.L.R.R.'s laboratory), ErbB4 (Cary Lai), Gad67 (Brian Condie), Gucy1a3 (Imagen/Gene Cube), Ikaros (Katia Georgopolos), Lhx6 (Vassilis Pachnis), Reelin (Tom Curran), RXRγ (Kenny Campbell) Somatostatin (Tom Lufkin), Tiam2 (BM228957) and VGAT (NM_009508.2).

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were deeply anesthetized (P60) and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered solution (PB 0.1 M, pH 7.4). The brains were removed and postfixed overnight in the same fixative and cryoprotected by immersion in 30% sucrose. Free-floating cryostat sections (40μm) were processed using standard procedures. Primary antibody dilutions used were as follows: rabbit anti-calretinin (CR) (1:2000, Immunostar) anti-Parvalbumin (1:2000; Swant Swiss Abs),); rat anti-Somatostatin(1:200, Chemicon) or rabbit anti-NPY (1:2000, Immunostar), rabbit anti-GFP (1:2000, Moleular Probes), anti-Phosphorylated Histone H3 (1:200, Upstate). Secondary antibodies were as follows: Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit, Alexa 488 goat anti-chicken, Alexa 594 goat anti-rat, Alexa 594 goat anti-rabbit. Immunoperoxidase staining was performed by using the ABC elite or M.O.M. kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA).

MGE dissections

Exencephalic telencephali of Dlx5/6-/- mutants possess a characteristic appearance, the pallium is located laterally, whereas the subpallium is located in medially (supplemental Fig.1A, 1B, 1C, 1D). To gain a better view of GFP expression in Dlx5/6-/- brains, we removed the pallium from the subpallium and positioned (flipped) the subpallium so that its pial sidefaced upwards (supplemental Fig. 1G). The area with the strongest GFP intensity in Dlx5/6-/- mutants was located slightly off of the medial-most side of the telencephalon, roughly half way along the rostral-caudal axis, and deep to the ventricular surface. This intensely positive GFP region was present in all genotypes studied: Dlx5+/+, Dlx5-/-, Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6-/-, and was designated the MGE mantle zone (MZ)/ventral subpallium (Supplemental Fig. 1E & 1F). For transplantation, we used the VZ/SVZ region just superficial to the intensely GFP positive region. To dissect the VZ/SVZ region of Dlx5/6-/- MGE, four cuts were made at the edges of the intensely GFP positive region; two cuts were made along medial-lateral axis at their anterior and posterior limits, then two were made along the rostral-caudal axis at their lateral and medial limits (Supplemantal Fig. 1G). The excised tissue block corresponds to the MGE; it was then rotated 90 degrees, placing it on one of its cutting surfaces. We then made an incision that separated the VZ/SVZ from the MZ. The surface VZ/SVZ region (dotted line area in Supplemantal Fig.1E & 1F) was removed and processed for the transplantation and cell culture.

Transplantation

Cell transplantations of interneuron precursors from Dlx5+/+, Dlx5-/-, Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6-/- donors into WT neonates (P0) were performed as described previously(Cobos et al., 2005). Embryos carrying Lhx6-GFP BAC transgene were dissected at E13.5. VZ/SVZ regions of medial ganglionic eminences were dissected from each embryo in HBSS (Gibco). Explants were then washed with 200ul of HBSS medium containing 50 ug/ml DNase I (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and mechanically dissociated. Dissociated cells were concentrated by centrifugation (3 minutes, 800 g) and resuspended in 2 ul of HBSS. Cell suspensions were loaded into glass micropipettes (∼50 um diameter) that were pre-filled with mineral oil. Micropipettes were connected to a microdispenser (Drummond) with direct readout for fractional microliters. Recipient pups (P0) were anesthetized on ice. A total of 5 × 105 cells per mouse in a 100–200 nl volume was injected into parietal cortex in a single point using a 45° inclination angle. Grafted pups were returned to their mothers and analyzed after 2 months. The percentage of GFP+ cells expressing CR, PV, SST or NPY in grafted animals was determined using a BX-60 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with epifluorescence illumination. At least 100 GFP+ in cortex were analyzed per each marker in each animal.

Cell culture

Cultures of Dlx5/6+/ or -/- MGE cells were established and maintained using previously described methods (Xu et al., 2004). Briefly, the MGE was identified by both morphological appearance and by location of GFP fluorescence, and dissected into cold Hank's Buffer. Tissue was cut into pieces and transferred into Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27 prior to trypsinization. Trypsinization for 15′ at 0.05% + 10ug/ml DNAse was carried out at 37°C, terminated by the addition of an excess of DMEM supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and followed by two rounds of mechanical dissociation. The first used large bore Pasteur pipettes, the second used small bore pipettes. Cells were pelleted in between and following the second dissociation by centrifugation at 2000 rpm, 4°C, 4 min, and resuspended in cold DMEM/FBS. Prior to plating, cells were strained and counted using a hemocytometer. 5000 MGE cells were plated into one chamber (0.4cm2) of a 16 chamber slide (LABTEK) that had been previously coated with laminin and poly-L-lysine (2 days prior) and seeded (1day prior) with approximately 1×105 cortical cells isolated from GFP-negative CD1 P0 or P1 neonates as described above. Cultures were grown at 37°C under 5-6%CO2. 50% of the media was exchanged for NB/B-27 at 1 day post plating, 2 days post plating, and every other day following. At the termination point, cells were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde/PBS prior to GFP immunohistochemistry. GFP cells were counted by hand using a compound fluorescence microscope. The ratio of the numbers of GFP positive cells/chamber at 5 days in vitro (DIV) and 10DIV or 5DIV and 40 DIV is defined as Percent Survival.

Video- electroencephalography (EEG)

For monitoring, surface head mount EEG hardware was purchased from Pinnacle Technology, Inc. (Lawrence, KS). Mice were anesthetized and the skull surface was exposed with a single rostral/caudal incision. Head mounts were attached with four conductive stainless steel screws, which also acted as recording electrodes. Two wires were laid on top of the shoulder muscles for electromyographic recording. Dental cement was used to secure the head mount, and mice recovered for four days before recordings commenced. Recordings were sampled at 400 Hz and high-pass filtered at 1 Hz (EEG) and 10 Hz (EMG). Each mouse was monitored 3-12 hours/day; up to 8 non-consecutive days (alternating day and night recording sessions when possible). A total of 16,980 min (34 d) of recording were obtained for Dlx5/6+/- mice and 9,933 min (28 d) for controls. Low-pass filtering was done at 40 Hz (EEG) and 100 Hz (EMG). Simultaneous video was obtained at two different angles using Microsoft LifeCam VX-3000 cameras linked via a USB-port to a PC-based computer running Active WebCam software. Seizure discharges were detected by SireniaScore software (Pinnacle) and confirmed by off-line review by an investigator blind to the status of the animal.

Wavelet-based power measurements

We measured power in 60-second EEG recordings. We recorded EEG from two sites in each mouse, as described previously (Baraban et al., 2009). Recordings were chosen to occur during period of wakefulness and to be free of cortical spikes and electrographic seizures. For each 60-second recording, we computed the power as a function of frequency and time. Frequency varied between 4 and 200 Hz, using 2 Hz increments. Time was measured by dividing each 60-second recording into 1-second epochs. To measure the power at frequency f within each 1-second long epoch, we first bandpass filtered the recording between f ± 2 Hz, then convolved the filtered signal with a wavelet with frequency f, defined as: Wft= e-t243f2e2πift.

We used the squared amplitude of the result to measure the instantaneous power at that frequency. The power during a 60-second recording was the average of the power measured during each of the 1 second long epochs within that recording.

Cell counting in histological sections

The number of interneurons expressing different genes (E16.5), the percentage of Dlx5-GFP+ cells expressing DLX2 (E15.5) or standard interneuron markers (P60), were determined in the lateral cortex (E15.5 & E16.5) and somatosensory cortex (P60) respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t- test or ANOVA analysis.

Results

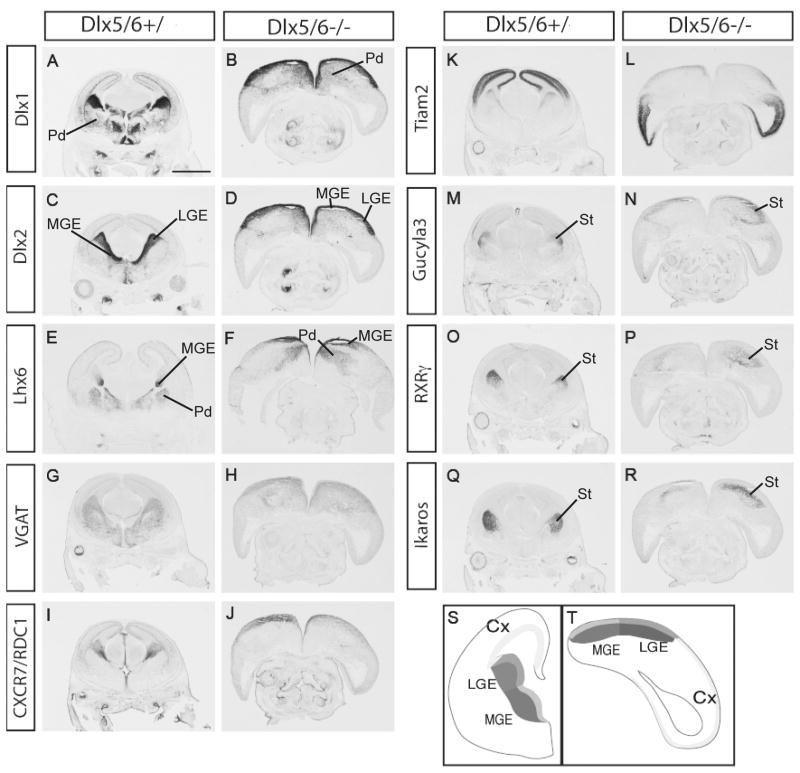

Exencephalic Dlx5/6-/- mutants have normal telencephalic patterning

Previous reports demonstrated that simultaneous deletion of Dlx5 and 6 results in exencephaly in the anterior brain, which is mainly due to distinctive craniofacial defects and the complete absence of calvaria. (Depew et al., 2002; Robledo et al., 2002). To evaluate regional patterning and differentiation within this dysmorphic forebrain, we used in situ hybridization on E15.5 coronal sections. As a visual aid, we show schematic representations of the pallial and subpallial domains of coronal sections of wild type and Dlx5/6-/- (Fig. 1S&1T, Supplemental Fig. 2). Dlx1 and Dlx2 are expressed in the subpallial VZ and SVZ (ventricular and subventricular zones), and in migratory interneurons on their path from the MGE and caudal LGE into the cortex (Fig.1A & C); their expression appeared intact in the VZ and SVZ of the LGE and MGE (Fig.1B & 1D), and in interneurons that are tangentially migration to the cortex (see Fig. 4 for higher magnification). Lhx6 labels the SVZ and the mantle region of the MGE, and a large fraction of tangentially migrating interneurons; this expression was largely preserved in the Dlx5/6-/- mutants (Fig. 1E & 1F, Supplemental Fig. 3; see Fig. 4 for higher magnification).

Figure 1.

Preservation of telencephalic regional patterning, and features of subpallial differentiation, in E15.5 Dlx5/6-/- mutants. The Dlx5/6-/- mutants are exencephalic; a schematic representation of Dlx5/6+/ (S) and Dlx5/6-/- (T) is presented to help orient the reader to the regions of the exencephalic telencephalon. Coronal sections from Dlx5/6+/ and Dlx5/6-/- were labeled by in situ hybridization with markers of LGE and MGE progenitor and mantle zones; the Dlx5/6-/- mutants do not show major gene expression defects, although the morphologies of the telencephalic regions are abnormal (A∼R). Abbreviations: cx: cortex; lge: lateral ganglionic eminence; mge: medial ganglionic eminence; pd: pallidum (including globus pallidus); st: striatum. Scale bar: 1.5mm.

Figure 4.

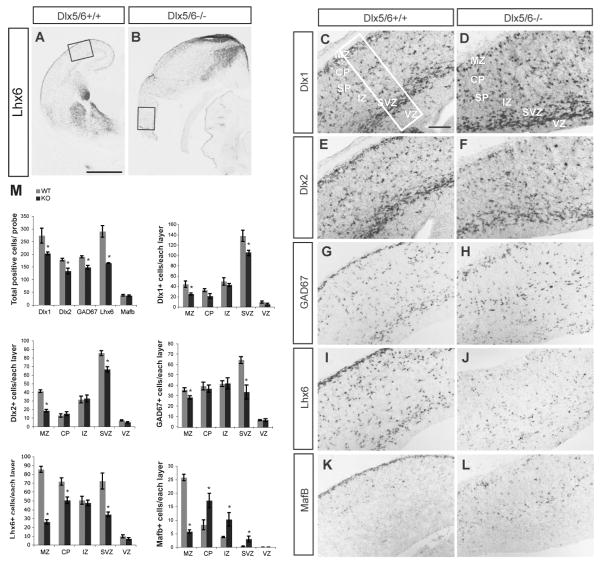

Reduced number of Dlx1+, Dlx2+, GAD67+, Lhx6+ cells in the lateral cortex of Dlx5/6-/- mutants at E16.5. in situ hybridization with probes for Lhx6 (A, B, I, J), Dlx1 (C,D), Dlx2 (E, F), GAD67 (G, H), and MafB (K,L) was carried out on coronal sections of Dlx5/6+/ and Dlx5/6-/- mutants. The boxes in A and B show the region that is shown at higher magnification in C-L. The box in C shows the size of the region used for cell counting; the total number of cells expressing these genes within 125,000μm2 of the lateral neocortex and the number of positive cells in each of the cortical layers are presented (M). The reduction is most severe in MZ and SVZ, particularly for Lhx6 and MafB within the MZ. Abbreviations: CP: cortical plate; IZ: intermediate zone; MZ: marginal zone; SVZ: subventricular zone; VZ: ventricular zone. Scale bars: A, B, 1mm; C∼L, 200μm.

In Dlx1/2-/- mutants, Dlx5 and 6 expression are almost eliminated from the LGE and MGE (Anderson et al., 1997b); thus it is possible that a significant component of their phenotype results from the loss of Dlx5 and 6 expression. Thus, we assessed the expression of a subset of genes that are strongly down-regulated in the LGE and MGE of Dlx1/2-/- mutants (VGAT, CXCR7, Tiam2, Gucy1a3, RXRγ and Ikaros) (Long et al., 2007; Long et al., 2009a; Long et al., 2009b). However, in the Dlx5/6-/- mutants, expression of these genes was not grossly reduced (Fig. 1G-1R), demonstrating that their transcription is strongly dependent on Dlx1&2 or other downstream effectors.

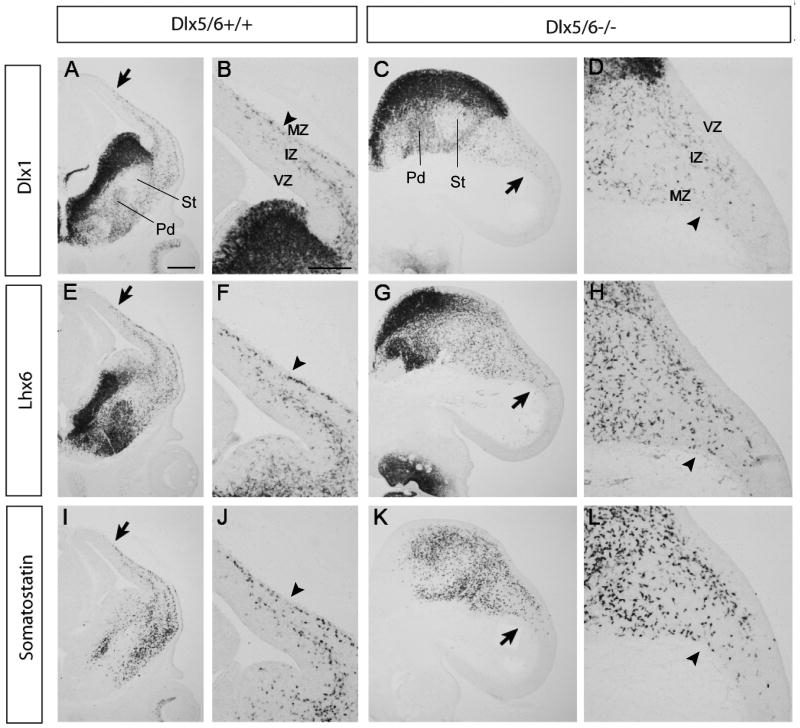

Interneuron migration is reduced in Dlx5/6-/- mutants

The majority of GABAergic interneurons of neocortex and hippocampus are generated from the ganglionic eminences and tangentially migrate to the developing cortex. Early-born populations of interneurons emerge from the MGE and invade the cortex by E13. To examine if the Dlx5/6-/- mutation affects early interneuron migration, we assessed expression of interneuron markers (Dlx1, Lhx6 and somatostatin) by in situ hybridization. In Dlx5/6+/+ embryos, superficial and deep migratory streams were present in the MZ and IZ/SVZ, respectively, and the leading migrating cells (denoted by black arrows) in MZ already reached the dorsal cortex (Fig2A, 2E, 2I). In Dlx5/6-/- embryos, the leading migrating cells did not migrate as far into the dorsal neocortex as in wild type controls (black arrows in Fig2C, 2G, 2K); Although the deep migratory stream was maintained, the superficial migratory steam was poorly formed (black arrowheads in Fig2D, 2H, 2L compared with those in Fig. 2B, 2F, 2J).

Figure 2.

Reduced tangential migration in Dlx5/6-/- mutants at E13.5. Coronal sections from Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6-/- were labeled by in situ hybridization against Dlx1 (A∼D), Lhx6 (E∼H) and Somatostatin (I∼L). The arrows point to the leading migrating cells. Note superficial migratory stream (arrowheads) in MZ is poorly formed in Dlx5/6-/- mutants. Abbreviations: IZ: intermediate zone; MZ: marginal zone; VZ: ventricular zone. Scale bars: A, E, I, C, G, K, 300μm; B, D, F, H, J, L, 200μm.

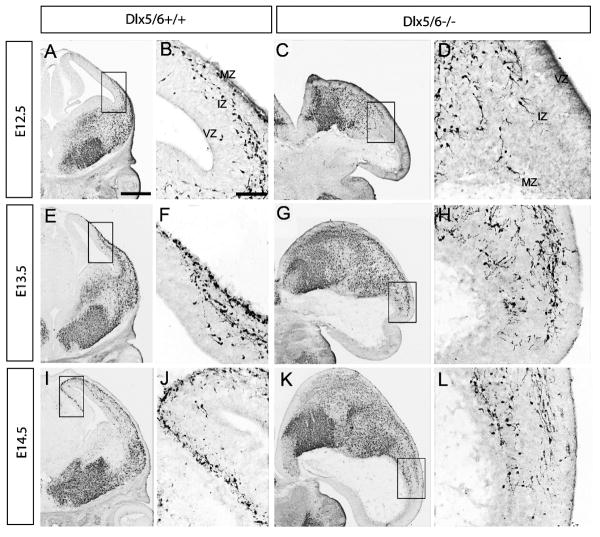

To follow the progression of this phenotype, we studied the interneuron distribution using a transgenic marker. We crossed a BAC transgene encoding the Lhx6 gene, which is driving expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Cobos et al., 2006). GFP immunohistochemistry in Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6-/- telencephalons at E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5 revealed a progressive retardation in the migration of Lhx6-expressing interneurons, in both the deep and superficial migratory streams in Dlx5/6-/- mutants (Fig. 3). We noticed that leading migrating cells in Dlx5/6+/- mutants at E14.5 reached roughly half way as far as that in Dlx5/6+/+ controls. This evidence for a delay suggested that all Lhx6-GFP+ interneurons (may include some interneurons that don't normally express Dlx5/6) were affected upon loss of Dlx5/6 function. It should be noted that we can not rule out that the excencephalic phenotype contributed in a non-autonomous manner to this phenotype. We also detected an accumulation of Lhx6+ interneurons in the SVZ of lateral ganglionic eminences (supplemental Fig. 4), suggesting reduced efficiency in the tangential migration of interneurons in Dlx5/6-/- mutants. Overall, Dlx5/6-/- mutants demonstrated a slowing of migration rather than a block in migration, in contrast with the Dlx1/2-/- mutants (Anderson et al., 1997a; Marin et al., 2000).

Figure 3.

Reduced tangential migration and accumulation of Lhx6-GFP positive cells in the SVZ of the LGE of Dlx5/6-/- mutants at E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5. Immunohistochemistry for GFP was carried out on coronal sections from E12.5 (A∼D), E13.5 (E∼H) and E14.5 (I∼L) Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6-/- mutants. Boxed areas shown in high magnification are the migrating cells at the front of migration. Dlx5/6-/- mutants show reduced tangential migration and an accumulation of Lhx6-GFP cells in the SVZ of the LGE. Abbreviations: IZ: intermediate zone; MZ: marginal zone; VZ: ventricular zone. Scale bars: A, C, E, G, I, K, 500μm; B, D, F, H, J, L, 200μm.

The exencephalic Dlx5/6-/- brains underwent degeneration at late gestational stages; the oldest brains that we could reliably analyze were E16.5. At this stage, we assessed neocortical interneuron molecular properties and extent of their migration by performing in situ hybridization to detect Dlx1, Dlx2, GAD67, Lhx6, and MafB (Fig. 4A-L). We quantified the total number of cells expressing these genes within 125,000μm2 of the lateral cortex, and the number of positive cells in each of the cortical layers (VZ, SVZ, IZ, CP, MZ). Our data showed that there was a general reduction of Dlx1+, Dlx2+, GAD67+, Lhx6+ cells in lateral cortex; the reduction was most severe in MZ and SVZ, however there was a preferential depletion of Lhx6 and MafB within the MZ (see histograms in Fig. 4M). Furthermore, while the number of MafB+ cells was normal, their laminar distribution was greatly disturbed (Fig. 4M). Thus, the Dlx5/6-/- mutation appears to preferentially affect the Lhx6+ and MafB+ migrating interneurons within the neocortex.

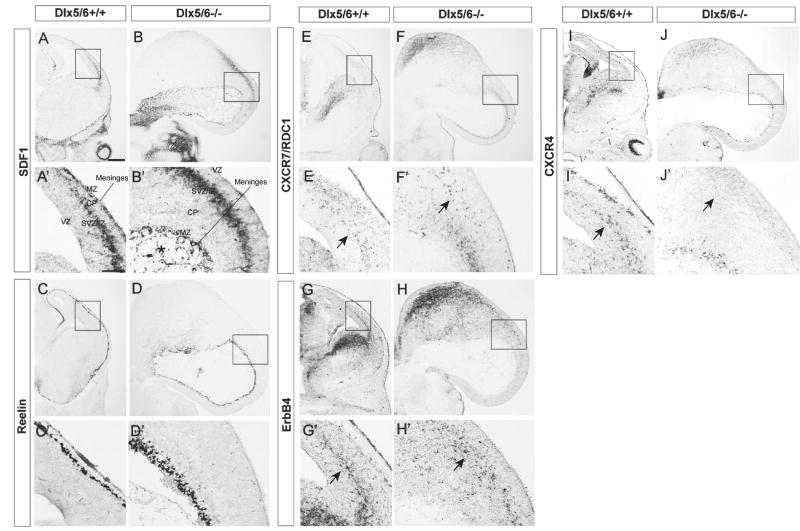

Loss of CXCR4 expression in deep migrating interneurons in the Dlx5/6-/- mutants

Towards elucidating the mechanism(s) underlying the reduced number of interneurons in the Dlx5/6-/- cortex, we tested the expression of molecules that are implicated in regulating interneuron migration. To determine whether the exencephaly altered the properties of the meninges, we examined expression of the cytokine stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF1), which is known to regulate migration and laminar positioning of interneurons and Cajal Retzius cells (Stumm et al., 2003; Borrell and Marin, 2006; Li et al., 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al., 2008). Despite the gross malformation, SDF1 expression in the meninges was apparent; however, the cavity formed by the everted exencephalic cortex was filled with SDF1+ cells. (* in Fig.5B′). SDF1 expression in the intermediate zone of ventro-lateral cortex appeared normal (Fig. 5B & 5B′).

Figure 5.

Loss CXCR4 expression in deep migratory interneurons of Dlx5/6-/- mutants at E13.5. Coronal sections from Dlx5/6+/+ (A, C, E, G, I) and Dlx5/6-/- (B, D, F, H, J) were labeled by in situ hybridization against SDF1, Reelin, CXCR7 (RDC1), ErbB4 and CXCR4. Boxed areas are shown below in high magnification. The expression SDF1 and reelin was maintained in Dlx5/6-/- mutants (B,D). The cavity formed by the everted exencephalic cortex contained scattered SDF1+ cells. (* in B′) Although the expression of CXCR7 and ErbB4 was intact, CXCR4 expression was not detected in deep migratory interneurons (arrows in E′, F′, G′, H′, I′, J′). Abbreviations: CP: cortical plate; IZ: intermediate zone; MZ: marginal zone; SVZ: subventricular zone; VZ: ventricular zone. Scale bar: 300μm.

Next we assessed the properties of the neocortical marginal zone, which contains Reelin-expressing Cajal Retzius cells that tangentially migrate over its surface from several sources (Bielle et al., 2005). Reelin expression has a prominent role in regulating the laminar position of cortical projection neurons and interneurons, although it is unclear whether the interneuron phenotypes are cell autonomous (Hevner et al., 2004; Hammond et al., 2006; Pla et al., 2006; Yabut et al., 2007). Reelin expression appeared roughly normal in the Dlx5/6-/- mutants (Fig. 5D, 5D′). Thus the tangential migration of Reelin+ cells to cover the cortex shows that the reduction of Dlx1, Dlx2, Lhx6 and GAD67 expression in the marginal zone is not due to a general disruption of migration in this layer.

Migrating interneurons express several known receptors that promote their migrations. First we examined expression of two receptors for SDF1: CXCR4 and CXCR7 (RDC, CMKOR1). CXCR4 regulates laminar positioning of interneurons (Stumm et al., 2003; Li et al., 2008; Liapi et al., 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al., 2008; Tiveron and Cremer, 2008); the function of CXCR7 has not been established, but its expression is reduced in Dlx1/2-/- mutants (Long et al., 2009a,b). In Dlx5/6-/- mutants, although CXCR4 expression appeared intact in Cajal Retzius cells and in the striatum, its expression was not detectable in interneurons tangentially migrating in the cortex (arrows in Fig. 5I′, 5J′). In contrast, CXCR7 expression in migrating interneurons appeared normal (arrows in Fig. 5E′, 5F′).

Finally, we examined expression of ErbB4, a receptor for neuregulin, which also promotes interneuron migration (Flames and Marin, 2005). The expression of ErbB4 was maintained in the MGE and LGE, and in deep migrating interneurons in Dlx5/6-/- mutants (Fig.5G′, 5H′). Furthermore, the expression of two ErbB4 ligands, neuregulin1 (NRG-1) and sensory and motor neuron-derived factor (SMDF; a form of neuregulin1) was intact in Dlx5/6-/- mutants (Supplemental Fig. 5). Thus, the reduction in CXCR4 expression may contribute to the interneuron migration deficit of Dlx5/6-/- mutants.

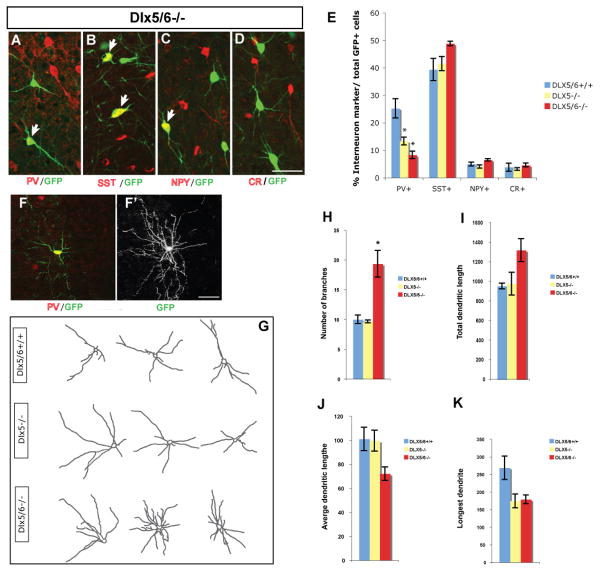

Dlx5/6 regulate interneuron specification in cell-autonomous manner

While loss of CXCR4 expression in migrating interneurons may contribute to the reduced numbers of tangentially migrating interneurons, we could not rule out the contribution of the exencephalic nature of the Dlx5/6-/- brain. To circumvent this caveat, we transplanted E13.5 Dlx5/6-/- mutant MGE cells into a wild type postnatal day 0 (P0) cortex. We used the Lhx6-BAC GFP transgene (which has previously been shown to label approximately 75-85% of PV+ and 55-70% of SST+ interneurons) (Cobos et al., 2006) as a reporter to follow the fate of MGE-derived offspring cells. Furthermore, to determine the individual role of Dlx5 in cortical interneuron development, we performed the transplantation using MGE cells from Dlx5-/- mutants (Long et al., 2003).

We analyzed the grafted cells at 1 and 2 months after transplantation. Of the 86 transplantations, 62 pups contained grafted cells, judged by GFP immnohistochemistry. Grafted interneuron precursors from Dlx5/6-/- and Dlx5-/- mutants were able to migrate, with leading migrating cells 4.0mm away from the injection site along the rostral-caudal axis, and no differences were detected in the distribution of GFP+ neurons between wild type, Dlx5-/- and Dlx5/6-/- mutants (Supplemental Fig.6). This shows that the intracortical migration of Lhx6-GFP+ interneurons (at least postnatally) may not rely on Dlx5/6 function.

Next, we compared the percentage of neurons that differentiated into PV+, SST+, NPY+ and calretinin+ cells from the Dlx5/6+/+, Dlx5-/- and Dlx5/6-/- transplants (Fig. 6A∼6D). We only detected a phenotype for PV+ interneurons. There was a ∼2-fold reduction in Dlx5-/- transplants and a ∼3 fold reduction in the Dlx5/6-/- transplants (Fig. 6E)(Dlx5/6+/+: 25.21±3.49%; Dlx5-/-: 13.29±1.38%; Dlx5/6-/-: 8.27±1.37%; P = 0.01).

Figure 6.

Cell-autonomous role for Dlx5/6 in controlling differentiation of PV+ cortical interneurons. E13.5 Dlx5-/- or Dlx5/6-/- mutant MGE cells were transplanted into a wild type postnatal day 0 (P0) cortex; the Lhx6-BAC GFP transgene was a reporter to follow the fate of MGE-derived cells several weeks after transplantation. (A∼D) Neocortical interneurons differentiated from transplanted Lhx6-GFP-expressing Dlx5/6-/- precursors, as shown by double immunofluorescence with anti-PV, anti-SST, anti-NPY or anti-CR antibodies. E. Percentage of double-labeled cells in the neocortex of 2-month-old mice grafted with control (blue), Dlx5-/- (yellow) and Dlx5/6-/- (red) cells. The percentage of GFP+/PV+ double-positive cells is reduced in mice grafted with either the Dlx5-/- or Dlx5/6-/- MGE cells. To analyze the morphology of GFP+/PV+ interneurons, Z-stack confocal image for dendrite analysis was used; a representative GFP+/PV+ grafted cell from Dlx5/6-/- mutant is shown(F); the same cell was captured with Z-stack confocal image for dendrite analysis (F′). (G) Representative images of grafted PV+ neocortical interneurons from control, Dlx5-/- and Dlx5/6-/- mutants. (H∼K) Quantification of dendrite branching of PV+ interneurons from control (blue), Dlx5-/- (yellow) and Dlx5/6-/- (red) mutants. Note that, the number of branches is increased in Dlx5/6-/- grafted PV+ interneurons. Scale bar: 100μm.

Finally, to assess whether the Dlx5-/- and Dlx5/6-/- mutations affected the dendritic morphology of PV+ grafted cells, we studied confocal images using Image J software. Dendritic arborization of the grafted (GFP+) PV+ cells could be assessed in isolated interneurons (Fig.6F, 6F′); we manually traced the dendritic arbors of 15 cells from each genotype and measured the number of processes, total dendritic length, average dendritic length, and longest dendrite (Fig. 6G). The Dlx5/6-/- mutant cells showed a statistically significant increase in the number of processes compared with cells from Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5-/- donors (Dlx5/6+/+: 10.00±0.71%; Dlx5-/-: 9.67±0.25%; Dlx5/6-/-: 19.33±0.71%; P = 0.01) (Fig.6H). Accordingly, PV+ cells from Dlx5/6-/- tended to display an increase in total dendritic length (Fig. 6I). However, average dendritic length, length of the longest dendrite of PV+ cells from Dlx5/6-/- decreased by the approximately 25% and 35% respectively (Fig. 6J, 6K). Dendritic morphology of Dlx5-/- mutants was only mildly affected.

Dlx5/6 are not essential for short-term in vitro cell survival of MGE cultures

The reduced numbers of cortical interneurons in the embryonic Dlx5/6-/- mutants, and the reduced fraction of PV+ interneurons transplanted from the MGE of Dlx5/6-/- could be due to reduced survival of these cells. Dlx1 and Dlx2 are known to promote neuronal survival. For instance, Dlx1-/- mutants have increased cell death of subsets of postnatal cortical interneurons, and Dlx1&2-/- mutants have massive prenatal cell death in vivo in the basal ganglia and in vitro in cultures derived from the MGE of Dlx1/2-/- mutants (Cobos et al., 2007). Note that loss of Dlx1&2 expression in the MGE results in loss of Dlx5&6 expression (Anderson et al., 1997b). Thus, to test whether MGE-derived cells of Dlx5/6-/- mutants have reduced survival, we used the in vitro culture assay described in Cobos et al (2007). Unlike the Dlx1/2-/- mutants, which have >95% cell death after 10 days in vitro, the Dlx5/6-/- mutant MGE cells showed indistinguishable survival compared to Dlx5/6+/+ cells for up to 40 days in vitro (Supplemental Fig. 7). Furthermore, cell death analysis at embryonic stages (Supplemental Fig. 8) or of the transplanted cortex showed no evidence of increased apoptosis 15 and 30 days after transplantation by TUNEL staining and anti–active caspase-3 immunohistochemistry (data not shown).

Finally, there could be reduced proliferation in the Dlx5/6-/- MGE leading to reduced interneuron production. While we have not definitively ruled this out, our analysis of M phase cells (PH3+) (Supplemental Fig. 9) and growth in MGE cultures did not detect an obvious phenotype.

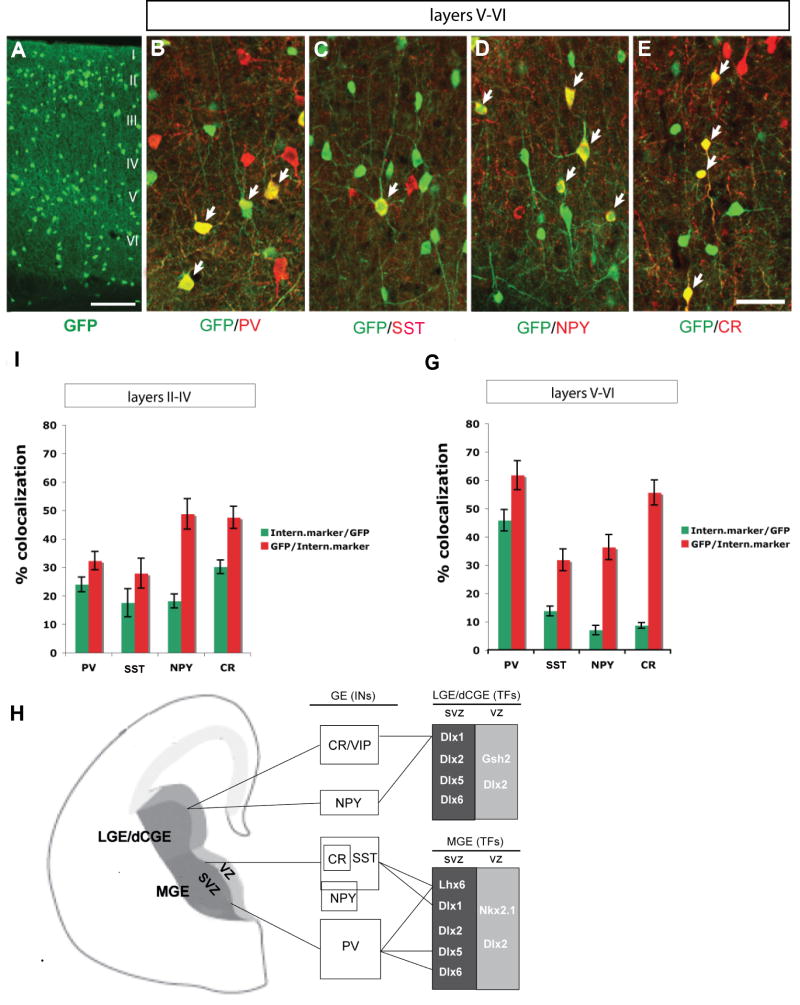

Cellular characterization of neocortical interneurons from Dlx5 BAC transgenic mouse line

The transplantation results show that Dlx5 and Dlx5/6 are required for the development of a substantial fraction of PV+ neocortical interneurons (Fig. 6). The expression of Dlx5 and Dlx6 in maturing and adult cortical interneurons has previously not been examined, thus we sought to explore whether their expression present in PV+ interneuron. Unfortunately, we do not have antibodies that specifically detect their DLX5 or DLX6 proteins, and therefore we used other methods to detect their expression. We assessed Dlx6 expression in the postnatal brain by in situ hybridization and by using LacZ expression from the Dlx6 locus. Neither assay showed robust expression (data not shown), although the Allen Brain Atlas does detect its expression in low numbers of scattered neocortical cells, consistent with its expression in a small subset of interneurons. Thus, in addition to its expression in the subventricular zone of the MGE and CGE (where it can regulate the early development of cortical interneurons), Dlx6 may also express in adult cortical interneurons.

To assess Dlx5 expression, we used the Dlx5-GFP BAC transgenic mouse line, in which EGFP reporter gene is inserted immediately upstream of the coding sequence of the Dlx5 gene. We began by analyzing GFP expression in tangentially migrating cortical interneurons at E15.5. Double-labeling immunohistochemistry was carried out with anti-DLX2 (Kuwajima et al., 2006) and anti-GFP antibodies. We found that not all immature interneurons co-express DLX2 and DLX5 in the marginal zone (MZ), cortical plate (CP) and intermediate zone/subventricular zone (IZ/SVZ) of the developing cortex. Roughly one-third of cells were Dlx5-GFP- (Supplemental Fig. 9)(30.18±2.65%, 30.73±2.96% and 41.86±1.96% in MZ, CP and IZ/SVZ, respectively). Furthermore, there was a small subpopulation of Dlx5-GFP+ cells that were DLX2- (Supplemental Fig.10) (10.21±0.71% in MZ, 10.02±0.67% in CP, 2.25±0.16% in IZ/SVZ, respectively).

Next we examined Dlx5-GFP expression in the adult (P60) somatosensory cortex. We assessed its expression among different interneuron populations in layers II-IV and layers V-VI. In layers II-IV, we found that Dlx5-GFP was rather evenly distributed among PV+, SST+, NPY+ and CR+ interneurons (23.97±2.60% in PV+, 17.49±4.95% in SST+, 18.11±2.46% in NPY+, 30.13±2.4% in CR+ interneurons) (Fig.7F). On the other hand in layers V-VI, Dlx5-GFP was predominantly expressed in PV+ interneurons (45.8 ± 3.75% in PV+, 13.75±1.71% in SST+, 6.97±1.62% in NPY+, 8.62±1.02% in CR+ interneurons (Fig.7G).

Figure 7.

Characterization of GFP expression in adult neocortical interneurons from the Dlx5 BAC transgenic mouse. (A) GFP immnoflurescence in coronal sections through somatosensory cortex at 2 months of age. (B∼E) Double immnoflurescence confocal images with anti-GFP and either anti-PV, anti-SST, anti-NPY or anti-CR antibodies. Quantification of the percentage of GFP+ cells that express each of the different interneuron markers (green bar) and the percentage of PV, SST, NPY or CR cells that express GFP (red bar) in layer II-IV (F) and layer V-VI (G). (H) Model of transcription factors that control the development of cortical and hippocampal interneurons. LGE/dCGE are proposed to generate CR/VIP+ and a subset of NPY+ (late born) interneurons, which express Dlx1 and require it for their survival. The dorsal MGE generates SST+ (including SST/CR+ and SST/NPY+) interneurons that express Dlx1 and Lhx6, and require them for their survival and differentiation, respectively. The ventral MGE produces PV+ interneurons that express Dlx5, and Lhx6, and require Dlx5, Dlx6 and Lhx6 for their differentiation. Abbreviations: LGE: lateral ganglionic eminence; MGE: medial ganglionic eminence; dCGE: dorsal caudal ganglionic eminence; SVZ: subventricular zone; VZ: ventricular zone. Scale bar: 100μm.

We also carried out fate mapping experiments on Dlx5/6-lineage neocortical interneurons by crossing Dlx5/6i-cre mice (Kohwi et al., 2007) into Rosa-YFP Cre reporter mice. Similarly, we found that GFP+ cells were predominately expressed in PV+ interneurons in layers V-VI (41.09±1.76% in PV+, 15.15±2.35% in SST+, 5.37±0.89% in NPY+, 8.52±2.05% in CR+ interneurons) (Supplemental Fig. 11). Thus, unlike Dlx1, which appears to be excluded from PV+ interneurons, Dlx5 is expressed in this interneuron subtype, and, based on our transplantation data, is required for their development.

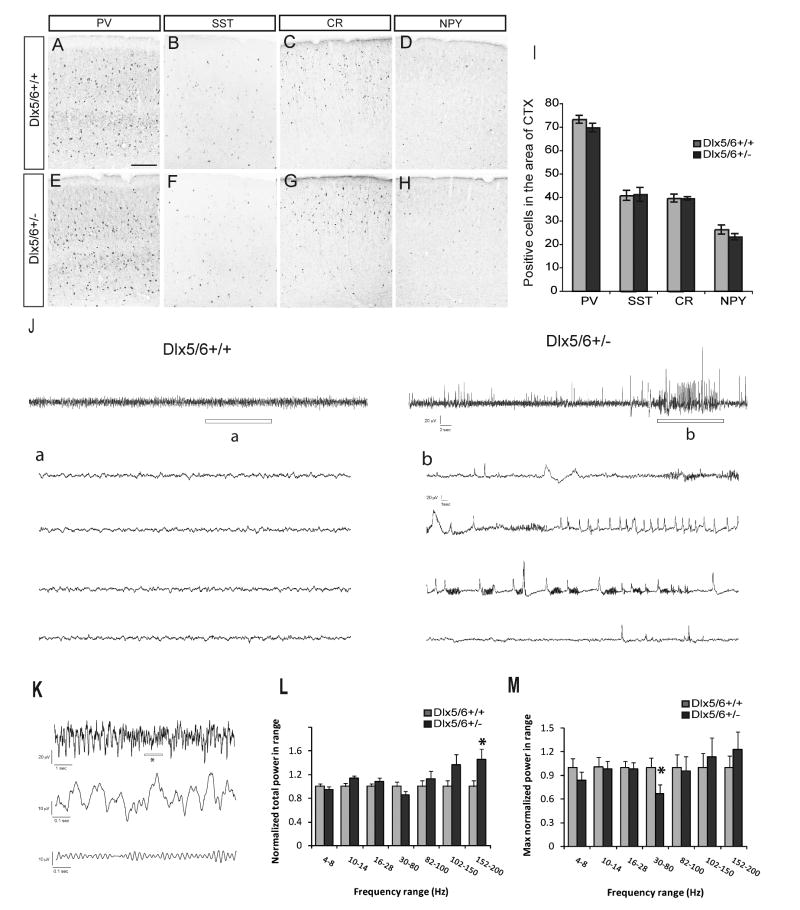

Spontaneous electrographic seizures and reduced maximum gamma power in Dlx5/6+/- heterozygotes in the absence of gross histological abnormalities

Adult Dlx1-/- mice exhibit generalized electrographic seizures (Cobos et al. 2005), suggesting that Dlx5/6 mutants may also have epilepsy. To circumvent the embryonic lethality of Dlx5/6-/- mice and determine whether reduced Dlx5/6 dosage has a functional consequence, we performed video-EEG monitoring and histological studies in adult (4-6 months of age) Dlx5/6+/- (heterozygous) mice.

We quantified the total number of cells expressing PV, SST, CR and NPY within a 380,000 μm2 region of somatosensory cortex; no significant differences were observed (Fig. 8A-I). Next, we performed video-EEG monitoring on Dlx5/6+/- (n = 5) and age-matched littermate control mice (n = 5) greater than 4 months of age during awake, freely moving behavior (Fig. 8J). Seventeen distinct electrographic seizure events (32.5 ± 6.4 sec duration) were confirmed in EEG recordings from four of the five Dlx5/6+/- mice. Representative events from Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6+/- mice are shown in Figure 8J. Electrographic events from Dlx5/6+/- mice began with a brief period of high frequency activity evolving into sharp high voltage spikes and polyspike bursting (Fig. 8J-b). Behaviors associated with these events were subtle and sometimes comprised a brief period of arrest with a slight head jerk. Electrographic seizure or behavior was never observed in control animals (Fig. 8J-a). Thus, reduced Dlx5/6 dosage appears to result in abnormal cortical function (i.e., seizures) despite the absence of gross anatomical abnormalities.

Figure 8.

Dlx5/6+/- mice show spontaneous electrographic seizures and reduced maximum gamma power in the absence of gross histological abnormalities. (A∼H) Expression of PV, SST, CR and NPY in somatosensory cortex of Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6+/- littermates. (I) Quantification of PV+, SST+, CR+, NPY+ cells within a region of 380,000μm2 of the somatosensory cortex. Scale bar: 200μm. (J) Sample EEG traces obtained during daytime recordings from freely moving adult Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6+/- mice. Top: 60-second long EEG recordings. Bottom: Enlargement of region indicated by “a” or “b” in the top trace. Note the presence of an abnormal epileptiform-like electrographic discharge in “b”. Scale bars (top): 20 uV, 2 sec; (bottom) 20 uV, 1 sec. (K) Sample EEG traces used for power analysis. Top: 10-second long EEG recording from a Dlx5/6+/+ mouse. Middle: enlargement of region indicated by “*” in the top trace. Bottom: Same as middle, but filtered between 30 and 80 Hz. (L) Total power as a function of frequency band for Dlx5/6+/+ or Dlx5/6+/- mice. For each frequency band, total power was normalized by the mean total power in Dlx5/6+/+ mice. Each bar represents an average over four mice from each group, five 60-second epochs from each mouse, and two EEG recording sites (n = 40 per group). (M) Maximum power within each frequency band for Dlx5/6+/+ or Dlx5/6+/- mice. For each mouse, we selected the 60-second epoch with the most power in each frequency band. Each bar represents an average over four mice from each group, and two EEG recording sites in each mouse (n = 8 per group). * P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

We hypothesized that the cortical hyperexcitability of Dlx5/6+/- mice might be due to the functional deficits of PV+ interneuron. We based this idea on our evidence that Dlx5/6 regulate prenatal development of the Lhx6+ neurons (Fig. 4), and regulate the number and dendritic morphology of PV+ cortical interneurons (Fig. 6). Because PV+ interneurons are thought to regulate gamma oscillations (Fuchs et al., 2007; Cardin et al., 2009; Sohal et al., 2009), we investigated the power in the different frequency bands in the EEG recording during periods of awake, freely moving mice. First we used wavelet analysis to measure the power in frequency bands between 4 and 200 Hz in EEG recorded from both Dlx5/6+/+ and Dlx5/6+/- mice (n = 4 mice per group). We analyzed five, 60-second long recordings from two sites in each animal. We found that Dlx5/6+/- mice exhibited a selective 45 ± 18% increase in the total power between 152-200 Hz (p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA; n = 40 recordings in each group).

Next we investigated whether gamma oscillations were affected in Dlx5/6+/- mice. However, because the presence of gamma oscillations is highly dependent on specific behaviors, we reasoned that gamma oscillations might not be present in all of the recordings. Therefore, for each set of recordings (five 60-second recordings from each site in each mouse), we selected the 60-second recording with maximum power in the gamma-range (30-80 Hz). We found that maximum gamma power was reduced by 33 ± 11% in Dlx5/6+/- mice (p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA; n = 8 recordings in each group). The reduced maximum gamma power in Dlx5/6+/- mice, and the defects in transplanted Dlx5/6-/- PV+ interneurons, provide evidence that Dlx5/6 regulate both the development and function of PV+ interneurons.

Discussion

We provide evidence that Dlx5&6 promote the prenatal tangential migration of cortical interneurons, in part through CXCR4 expression, and that postnatally Dlx5&6 are preferentially required for the development and dendritic morphology of PV+ interneurons. While the cortex of Dlx5/6+/- heterozygous mice appears anatomically normal, they have epilepsy and reduced power in their gamma oscillations, suggesting a defect in the function of their PV+ interneurons.

Normal patterning and differentiation in the embryonic basal ganglia of the exencephalic Dlx5/6-/- mutants

Despite the fact that the embryos are excencephalic (Robledo et al., 2002), we found that regionalization of the telencephalon was remarkably intact, based on the appropriate regional expression of pallial (e.g. Tbr1), striatal (e.g. Ikaros, RXRγ) and pallidal (e.g. ErbB4, Lhx6) markers, and the generation of subpallium-derived cortical interneurons (Figs. 1,2, 3, 4, 5; Supplemental Figs. 1, 2). However, because these mutants degenerate after ∼E16.5, and because of their exencephalic state, we can't conclude that subpallial differentiation is entirely intact. It is probable that persistent expression of Dlx1&2 (Fig. 1, 2, 3) can partially compensate for lack of Dlx5&6.

Reduced numbers of tangentially migrating Lhx6+ and MafB+ cortical interneurons

The cortex of Dlx5/6-/- mutants has reduced numbers of cells expressing markers of tangentially migrating immature interneurons (Figs. 2,3,4). At E16.5, there is a disproportionate reduction in the expression of Lhx6 and MafB in the MZ, compared to Dlx1, suggesting that Dlx5&6 are preferentially required for the development of some Lhx6+/MafB+ cortical interneurons.

There are at least two types of tangentially migrating interneurons: Dlx+ and Dlx+;Lhx6+ (Zhao et al., 2008). Lhx6 function is required for MafB expression and for the production of PV+ and SST+ interneurons (Liodis et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2008). Thus, the preferential reduction of Lhx6 and MafB suggests that Dlx5&6 have key roles in the development of PV+ and SST+ interneurons. Indeed, transplantation of Dlx5-/- and Dlx5/6-/- mutant MGE cells results in fewer PV+ neocortical interneurons (Fig. 6). The observation that SST+ interneurons are not reduced supports a hypothesis that Dlx5 and Dlx5&6 are more important in promoting the PV subtype; perhaps the subset of Lhx6+ interneurons that do migrate into the mutant embryonic cortex will become SST+.

We have not elucidated the mechanism(s) whereby Dlx5 and Dlx5&6 control PV interneuron development. There is clearly a defect in the efficiency of tangential migration and an apparent accumulation of Lhx6+ cells in the region of the MGE (Fig. 3 arrows). We studied the expression of receptors expressed on the tangentially migrating cells that are implicated in regulating their migration (CXCR4, CXCR7, ErbB4). There was a clear reduction in CXCR4 expression in cortical SVZ/IZ (Fig. 5). Given CXCR4's known function (Stumm et al., 2003; Li et al., 2008; Liapi et al., 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al., 2008; Tiveron and Cremer, 2008), this defect could contribute to the slowing of tangential migration in the Dlx5/6-/- mutants.

Reduced numbers of PV+ neocortical interneurons in Dlx5-/- and Dlx5/6-/- MGE transplants suggests a Dlx transcriptional code for interneuron development

Transplantation of mutant MGE into neonatal wild type cortex showed a selective deficit in the formation of PV+ interneurons; there was a ∼2-fold reduction in Dlx5-/- transplants and a ∼3 fold reduction in the Dlx5/6-/- transplants (Fig. 6). It strongly suggests a cell-autonomous requirement for Dlx5/6 in the development of PV+ interneurons. The Dlx5-/- phenotype was less severe than Dlx5/6-/- phenotype; this provides evidence that Dlx6 contributes to the development of PV+ interneurons. Dlx6 expression is weakly detected in the MGE SVZ (Anderson et al., 1997b), where it could, in conjunction with Dlx5, promote Lhx6 expression. Notably, Dlx1/2-/- mutants have a modest reduction in Lhx6 expression in the MGE SVZ (Petryniak et al., 2007). However, there is no obvious reduction in Lhx6 (or Lhx6-GFP) expression in the Dlx5/6-/- MGE SVZ; rather there may be increased expression (Figs. 2 and 3). It is possible that Dlx5&6 promote Lhx6 expression in developing PV+ interneurons, and not in developing SST+ interneurons. Alternatively, lack of Dlx5/6 could alter cell identity. While there is no definitive data showing this, there is a slight increase in SST+ cells in the transplants (Fig. 6).

PV+ and SST+ interneurons appear to arise preferentially from distinct dorsoventral domains of the MGE (Flames et al., 2007). The genetic mechanisms that differentially regulate their development are just beginning to be understood. Prenatally, Dlx1 and Lhx6 are initially expressed in most migrating interneurons; late in gestation a larger subset express only Dlx1 (Zhao et al., 2008). By adulthood, their expression becomes further restricted to specific subtypes. Dlx1 expression is not detected in PV+ interneurons, whereas it is expressed in most CR+ interneurons and subsets of SST+ and NPY+ interneurons; Lhx6 is expressed in most PV+ and SST+ interneurons and a small subsets of CR+ and NPY+ interneurons (Cobos et al., 2005). Here we show that while Dlx5 is broadly expressed prenatally in migrating interneurons, its expression in adult deep cortical layers is preferentially restricted to PV+ interneurons (Fig.7A-H). Thus, current evidence supports a model that Dlx1 and Dlx5 show differential expression and function in distinct subtypes of cortical interneurons: Dlx1 in Lhx6- interneurons that express SST, CR and NPY, and Dlx5 in Lhx6+ interneurons that express PV (Fig. 7H).

Spontaneous electrographic seizures and reduced maximum gamma power in Dlx5/6+/- heterozygotes

Clinical and experimental evidence demonstrating an impairment of GABA-mediated inhibition in epilepsy is quite common (Treiman, 2001). Loss of GABA-producing interneurons is considered a critical aspect of this impairment and has been observed in tissue sections from patients with intractable epilepsy (Knopp et al., 2008) and, more recently, in mutant mice (Powell et al., 2003; Cobos et al., 2005; Marsh et al., 2005; Glickstein et al., 2007; Butt et al., 2008; Marsh et al., 2009). These findings contribute to an emerging concept that epileptic disorders associated with interneuron dysfunction could be classified as an “interneuronopathy” (Kato and Dobyns, 2005). Our analysis of Dlx5/6+/- mutants is consistent with this classification and indicates that reduced Dlx5/6 dosage results in brief spontaneous electrographic seizures. This is an interesting finding given that we did not detect a frank decrease in interneuron density in the cortex or hippocampus of these animals. However, because we did observe impairment in the dendritic/axonal arbors of PV+ interneurons from Dlx5/6-/- mutant transplants, these findings suggest that epilepsy can be associated with subtle changes in interneuron structure. That altered PV+ interneuron morphology leads to functional impairment was further confirmed in our observations of reduced gamma power in the EEG recordings; gamma waves a signature of PV+ interneuron function (Fuchs et al., 2007; Cardin et al., 2009; Sohal et al., 2009). As such, we hypothesize that Dlx5/6 regulates postnatal properties of PV+ interneurons. Future studies are needed to establish the cellular and molecular basis of this physiological phenotype, although clues could be found in the recent paper describing developmental gene expression in PV+ interneurons (Okaty et al., 2009).

The observation of electrophysiological defects in Dlx5/6+/- mice is important as it provides the first evidence that reduced gene dosage (heterozygosity of a loss of function allele) of transcription factors result in epilepsy, and yet show no obvious anatomical defect (Fig. 8). This finding may be germane to human neuropsychiatric disorders, where geneticists are discovering mutations in heterozygosity states. For instance, we have identified autistic probands who are heterozygous for two types of non-synonymous mutations in Dlx5 (Hamilton et al., 2005).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the research grants to: JLRR from Nina Ireland, the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, NIMH R01 and R37 MH49428-01, and K05 MH065670; to YW from C.U.R.E Rhode Island Award from the Epilepsy Foundation; to CAD from NARSAD; to VSS from a T32 postdoctoral training fellowship from NIMH; to KD from Stanford, BioX/Bioengineering, NIMH, NIDA, NSF, CIRM, HHMI, and the McKnight, Coulter, Kinetics, and Keck Foundations; and to SCB from NIH grant 5R01NS048528.

Footnotes

The authors contributed to the following figures: Figs.1, 4: YW, CD, JL; Figs. 2, 3, 5, 6, 7: YW; Fig.8: YW, VSS, SCB, RCE; Supplemental Fig.1: YW, CD; Supplemental Figs 2, 3, 7: CD, TR, JL; Supplemental Figs. 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10,11: YW.

References

- Anderson SA, Eisenstat DD, Shi L, Rubenstein JL. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: dependence on Dlx genes. Science. 1997a;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA, Qiu M, Bulfone A, Eisenstat DD, Meneses J, Pedersen R, Rubenstein JL. Mutations of the homeobox genes Dlx-1 and Dlx-2 disrupt the striatal subventricular zone and differentiation of late born striatal neurons. Neuron. 1997b;19:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraban SC, Southwell DG, Estrada RC, Jones DL, Sebe JY, Alfaro-Cervello C, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Rubenstein JL, Alvarez-Buylla A. Reduction of seizures by transplantation of cortical GABAergic interneuron precursors into Kv1.1 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15472–15477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielle F, Griveau A, Narboux-Neme N, Vigneau S, Sigrist M, Arber S, Wassef M, Pierani A. Multiple origins of Cajal-Retzius cells at the borders of the developing pallium. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nn1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell V, Marin O. Meninges control tangential migration of hem-derived Cajal-Retzius cells via CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1284–1293. doi: 10.1038/nn1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt SJ, Fuccillo M, Nery S, Noctor S, Kriegstein A, Corbin JG, Fishell G. The temporal and spatial origins of cortical interneurons predict their physiological subtype. Neuron. 2005;48:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt SJ, Sousa VH, Fuccillo MV, Hjerling-Leffler J, Miyoshi G, Kimura S, Fishell G. The requirement of Nkx2-1 in the temporal specification of cortical interneuron subtypes. Neuron. 2008;59:722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin JA, Carlen M, Meletis K, Knoblich U, Zhang F, Deisseroth K, Tsai LH, Moore CI. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature. 2009;459:663–667. doi: 10.1038/nature08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Borello U, Rubenstein JL. Dlx transcription factors promote migration through repression of axon and dendrite growth. Neuron. 2007;54:873–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Long JE, Thwin MT, Rubenstein JL. Cellular patterns of transcription factor expression in developing cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16 1:i82–88. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Calcagnotto ME, Vilaythong AJ, Thwin MT, Noebels JL, Baraban SC, Rubenstein JL. Mice lacking Dlx1 show subtype-specific loss of interneurons, reduced inhibition and epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1059–1068. doi: 10.1038/nn1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasante G, Collombat P, Raimondi V, Bonanomi D, Ferrai C, Maira M, Yoshikawa K, Mansouri A, Valtorta F, Rubenstein JL, Broccoli V. Arx is a direct target of Dlx2 and thereby contributes to the tangential migration of GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10674–10686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1283-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo E, Collombat P, Colasante G, Bianchi M, Long J, Mansouri A, Rubenstein JL, Broccoli V. Inactivation of Arx, the murine ortholog of the X-linked lissencephaly with ambiguous genitalia gene, leads to severe disorganization of the ventral telencephalon with impaired neuronal migration and differentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4786–4798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0417-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depew MJ, Lufkin T, Rubenstein JL. Specification of jaw subdivisions by Dlx genes. Science. 2002;298:381–385. doi: 10.1126/science.1075703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du T, Xu Q, Ocbina PJ, Anderson SA. NKX2.1 specifies cortical interneuron fate by activating Lhx6. Development. 2008;135:1559–1567. doi: 10.1242/dev.015123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N, Marin O. Developmental mechanisms underlying the generation of cortical interneuron diversity. Neuron. 2005;46:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N, Pla R, Gelman DM, Rubenstein JL, Puelles L, Marin O. Delineation of multiple subpallial progenitor domains by the combinatorial expression of transcriptional codes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9682–9695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2750-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty M, Grist M, Gelman D, Marin O, Pachnis V, Kessaris N. Spatial genetic patterning of the embryonic neuroepithelium generates GABAergic interneuron diversity in the adult cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10935–10946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1629-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs EC, Zivkovic AR, Cunningham MO, Middleton S, Lebeau FE, Bannerman DM, Rozov A, Whittington MA, Traub RD, Rawlins JN, Monyer H. Recruitment of parvalbumin-positive interneurons determines hippocampal function and associated behavior. Neuron. 2007;53:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulp CT, Cho G, Marsh ED, Nasrallah IM, Labosky PA, Golden JA. Identification of Arx transcriptional targets in the developing basal forebrain. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3740–3760. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickstein SB, Moore H, Slowinska B, Racchumi J, Suh M, Chuhma N, Ross ME. Selective cortical interneuron and GABA deficits in cyclin D2-null mice. Development. 2007;134:4083–4093. doi: 10.1242/dev.008524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SP, Woo JM, Carlson EJ, Ghanem N, Ekker M, Rubenstein JL. Analysis of four DLX homeobox genes in autistic probands. BMC Genet. 2005;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond V, So E, Gunnersen J, Valcanis H, Kalloniatis M, Tan SS. Layer positioning of late-born cortical interneurons is dependent on Reelin but not p35 signaling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1646–1655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3651-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Daza RA, Englund C, Kohtz J, Fink A. Postnatal shifts of interneuron position in the neocortex of normal and reeler mice: evidence for inward radial migration. Neuroscience. 2004;124:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Dobyns WB. X-linked lissencephaly with abnormal genitalia as a tangential migration disorder causing intractable epilepsy: proposal for a new term, “interneuronopathy”. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:392–397. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200042001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura K, Yanazawa M, Sugiyama N, Miura H, Iizuka-Kogo A, Kusaka M, Omichi K, Suzuki R, Kato-Fukui Y, Kamiirisa K, Matsuo M, Kamijo S, Kasahara M, Yoshioka H, Ogata T, Fukuda T, Kondo I, Kato M, Dobyns WB, Yokoyama M, Morohashi K. Mutation of ARX causes abnormal development of forebrain and testes in mice and X-linked lissencephaly with abnormal genitalia in humans. Nat Genet. 2002;32:359–369. doi: 10.1038/ng1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopp A, Frahm C, Fidzinski P, Witte OW, Behr J. Loss of GABAergic neurons in the subiculum and its functional implications in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2008;131:1516–1527. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohwi M, Petryniak MA, Long JE, Ekker M, Obata K, Yanagawa Y, Rubenstein JL, Alvarez-Buylla A. A subpopulation of olfactory bulb GABAergic interneurons is derived from Emx1- and Dlx5/6-expressing progenitors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6878–6891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0254-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwajima T, Nishimura I, Yoshikawa K. Necdin promotes GABAergic neuron differentiation in cooperation with Dlx homeodomain proteins. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5383–5392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1262-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi G, Puche AC, Mantero S, Barbieri O, Trombino S, Paleari L, Egeo A, Merlo GR. The Dlx5 homeodomain gene is essential for olfactory development and connectivity in the mouse. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:530–543. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Adesnik H, Li J, Long J, Nicoll RA, Rubenstein JL, Pleasure SJ. Regional distribution of cortical interneurons and development of inhibitory tone are regulated by Cxcl12/Cxcr4 signaling. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1085–1098. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4602-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liapi A, Pritchett J, Jones O, Fujii N, Parnavelas JG, Nadarajah B. Stromal-derived factor 1 signalling regulates radial and tangential migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Dev Neurosci. 2008;30:117–131. doi: 10.1159/000109857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liodis P, Denaxa M, Grigoriou M, Akufo-Addo C, Yanagawa Y, Pachnis V. Lhx6 activity is required for the normal migration and specification of cortical interneuron subtypes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3078–3089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3055-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Cobos I, Potter GB, Rubenstein JL. Dlx1 and Mash1 Transcription Factors Control MGE and CGE Patterning and Differentiation through Parallel and Overlapping Pathways. Cereb Cortex. 2009a;19:i96–i106. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Garel S, Depew MJ, Tobet S, Rubenstein JL. DLX5 regulates development of peripheral and central components of the olfactory system. J Neurosci. 2003;23:568–578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00568.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Swan C, Liang WS, Cobos I, Potter GB, Rubenstein JL. Dlx1&2 and Mash1 transcription factors control striatal patterning and differentiation through parallel and overlapping pathways. J Comp Neurol. 2009b;512:556–572. doi: 10.1002/cne.21854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Garel S, Alvarez-Dolado M, Yoshikawa K, Osumi N, Alvarez-Buylla A, Rubenstein JL. Dlx-dependent and -independent regulation of olfactory bulb interneuron differentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3230–3243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5265-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bendito G, Sanchez-Alcaniz JA, Pla R, Borrell V, Pico E, Valdeolmillos M, Marin O. Chemokine signaling controls intracortical migration and final distribution of GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1613–1624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4651-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Anderson SA, Rubenstein JL. Origin and molecular specification of striatal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6063–6076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06063.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Plump AS, Flames N, Sanchez-Camacho C, Tessier-Lavigne M, Rubenstein JL. Directional guidance of interneuron migration to the cerebral cortex relies on subcortical Slit1/2-independent repulsion and cortical attraction. Development. 2003;130:1889–1901. doi: 10.1242/dev.00417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh E, Melamed SE, Barron T, Clancy RR. Migrating partial seizures in infancy: expanding the phenotype of a rare seizure syndrome. Epilepsia. 2005;46:568–572. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.34104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh E, Fulp C, Gomez E, Nasrallah I, Minarcik J, Sudi J, Christian SL, Mancini G, Labosky P, Dobyns W, Brooks-Kayal A, Golden JA. Targeted loss of Arx results in a developmental epilepsy mouse model and recapitulates the human phenotype in heterozygous females. Brain. 2009;132:1563–1576. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaty BW, Miller MN, Sugino K, Hempel CM, Nelson SB. Transcriptional and electrophysiological maturation of neocortical fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7040–7052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0105-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryniak MA, Potter GB, Rowitch DH, Rubenstein JL. Dlx1 and Dlx2 control neuronal versus oligodendroglial cell fate acquisition in the developing forebrain. Neuron. 2007;55:417–433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pla R, Borrell V, Flames N, Marin O. Layer acquisition by cortical GABAergic interneurons is independent of Reelin signaling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6924–6934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0245-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasure SJ, Anderson S, Hevner R, Bagri A, Marin O, Lowenstein DH, Rubenstein JL. Cell migration from the ganglionic eminences is required for the development of hippocampal GABAergic interneurons. Neuron. 2000;28:727–740. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell EM, Campbell DB, Stanwood GD, Davis C, Noebels JL, Levitt P. Genetic disruption of cortical interneuron development causes region- and GABA cell type-specific deficits, epilepsy, and behavioral dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2003;23:622–631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00622.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robledo RF, Rajan L, Li X, Lufkin T. The Dlx5 and Dlx6 homeobox genes are essential for craniofacial, axial, and appendicular skeletal development. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1089–1101. doi: 10.1101/gad.988402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature. 2009;459:698–702. doi: 10.1038/nature07991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumm RK, Zhou C, Ara T, Lazarini F, Dubois-Dalcq M, Nagasawa T, Hollt V, Schulz S. CXCR4 regulates interneuron migration in the developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5123–5130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05123.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussel L, Marin O, Kimura S, Rubenstein JL. Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development. 1999;126:3359–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiveron MC, Cremer H. CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling in neuronal cell migration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman DM. GABAergic mechanisms in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42 3:8–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042suppl.3008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonders CP, Anderson SA. The origin and specification of cortical interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:687–696. doi: 10.1038/nrn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Tam M, Anderson SA. Fate mapping Nkx2.1-lineage cells in the mouse telencephalon. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:16–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.21529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Cobos I, De La Cruz E, Rubenstein JL, Anderson SA. Origins of cortical interneuron subtypes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2612–2622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5667-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabut O, Renfro A, Niu S, Swann JW, Marin O, D'Arcangelo G. Abnormal laminar position and dendrite development of interneurons in the reeler forebrain. Brain Res. 2007;1140:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun K, Fischman S, Johnson J, Hrabe de Angelis M, Weinmaster G, Rubenstein JL. Modulation of the notch signaling by Mash1 and Dlx1/2 regulates sequential specification and differentiation of progenitor cell types in the subcortical telencephalon. Development. 2002;129:5029–5040. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerucha T, Stuhmer T, Hatch G, Park BK, Long Q, Yu G, Gambarotta A, Schultz JR, Rubenstein JL, Ekker M. A highly conserved enhancer in the Dlx5/Dlx6 intergenic region is the site of cross-regulatory interactions between Dlx genes in the embryonic forebrain. J Neurosci. 2000;20:709–721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Flandin P, Long JE, Cuesta MD, Westphal H, Rubenstein JL. Distinct molecular pathways for development of telencephalic interneuron subtypes revealed through analysis of Lhx6 mutants. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:79–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.