Abstract

The plaque assay has long served as the “gold standard” to measure virus infectivity and test antiviral drugs, but the assay is labor-intensive, lacks sensitivity, uses excessive reagents, and is hard to automate. Recent modification of the assay to exploit flow-enhanced virus spread with quantitative imaging has increased its sensitivity. Here we performed flow-enhanced infection assays in microscale channels, employing passive fluid pumping to inoculate cell monolayers with virus and drive infection spread. Our test of an antiviral drug (5-fluorouracil) against vesicular stomatitis virus infections of BHK cell monolayers yielded a two-fold improvement in sensitivity, relative to the standard assay based on plaque counting. The reduction in scale, simplified fluid handling, image-based quantification, and higher assay sensitivity will enable infection measurements for high-throughput drug screening, sero-conversion testing, and patient-specific diagnosis of viral infections.

Keywords: Microfluidic device, Infection assay, Antiviral drug, Passive pumping, Quantitative imaging

1 Introduction

Viruses cause deadly diseases such as influenza, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), hepatitis, cancer, and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and thereby create a significant and ever growing threat to human health. Anti-viral drugs play a key role in national and international plans to minimize spread of potentially deadly virus strains, but viruses can develop resistance to drugs, so it is important that a clear assessment of the drug susceptibility of virus strains be available in the clinic to guide effective treatments of individual patients (Petric et al. 2006). More broadly, assessments of drug susceptibility across populations will be central to effective surveillance, data that will be essential toward guiding national, state and local responses to minimize the spread of viral diseases. While nucleic acid-based assays have dominated new methods for identifying and testing viruses, assays based on the live-cell culture of viruses remain the “gold standard” for viral diagnostics (WHO 2005). The most widely used culture method to measure infectious virus particles is the plaque assay.

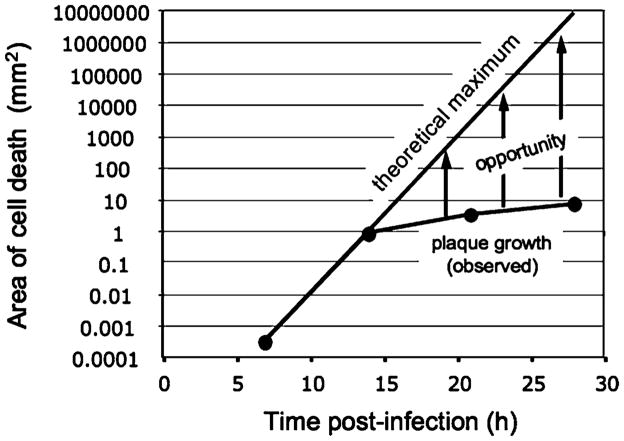

The plaque assay is based on the principle that single virus particles can be amplified in living cells to produce visible islands (or “plaques”) of cell death within a monolayer of host cells. The presence of a semi-solid agar over the cells prevents flows and mixing between plaques, so total plaque counts reflect the number of infectious virus particles in the original sample. Different drugs may inhibit plaque formation and the resulting plaque counts to different extents, providing a means to quantify drug potency (Hsiung et al. 1994). However, endpoints based on plaque counts rely on preventing plaque formation rather than merely inhibiting (or slowing) plaque growth. In general, more drug will be needed to prevent plaque formation than to slow plaque growth, so measures of infection based on plaque counts will be less sensitive than measures based on plaque size or area. The area of infection and resulting cell death expands linearly with time for a growing plaque (Lam et al. 2005; Yin 1991), but it expands exponentially with time in the theoretical limit (Fig. 1), suggesting that infection assays of exquisite sensitivity may be achieved if virus progeny from each infection cycle can be efficiently distributed to susceptible host cells. When the plaque assay was performed for vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) on a cell monolayer with an overlay of liquid medium, rather than semi-solid agar, the resulting fluid flows enhanced the spread of infection (Zhu and Yin 2007). Although the flows were not controlled, simply allowing flows to spread infections enabled a 20-fold enhancement in assay sensitivity relative to the standard plaque-reduction assay.

Fig. 1.

Slow spread of plaques limits amplification of their infection signal. The infection signal (area of cell death) in a plaque expands linearly with time. If every virus particle released by an infected cell could always find a healthy host cell to infect, the signal would grow exponentially with time. Fluid flows across infected cells transport progeny virus particles to distant cells, creating an opportunity to amplify the infection signal. Curves are based on vesicular stomatitis virus infecting BHK cells: each cell is a disk with diameter 36 μm, infected cells produce 3,000 virus particles in 7 h, and plaques spread with radial velocities of 70 μm/h

To control fluid flows and establish a platform for high-throughput infection assays, we sought to perform assays in a microfluidic device. Improvements in speed, reproducibility and throughput have been attained for genetic, biochemical and cellular analyses in microfluidic devices (Beebe et al. 2002; El-Ali et al. 2006; Hong and Quake 2003; Whitesides 2003), but relatively little progress has been made toward using such approaches to characterize virus growth or infection spread. Insect cells introduced into a microfluidic channel were exposed to a recombinant baculovirus that expressed green fluorescent protein upon infection (Walker et al. 2004), and infection of a retroviral packaging cell line in a perfused microfluidic bioreactor enabled continuous production of retrovirus (Vu et al. 2008), but neither of these studies sought to quantitatively characterize virus infections. Here we culture, detect and quantify virus growth and spread in the absence and presence of fluid flow, within microchannels, establishing an assay platform with potential applications in diagnostics, epidemiological monitoring, and drug discovery.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Device design and fabrication

Two devices were fabricated using soft lithography following established methods. The first device, a channel (16 mm×1 mm×250 μm) with ports at both ends, was used for preliminary studies of cell culture and virus propagation in the absence of fluid flow. The second device, a channel (32 mm×2 mm×250 μm) with inlet and outlet ports as well as an additional inoculation port 8 mm downstream of the inlet port, was used in the flow-enhanced spread of infections. The larger volume of the second device relative to the first device enabled the use of larger fluid volumes and less sensitivity of the device behavior to fluctuations in flows owing to hand pipetting. The location of the inoculation port was selected to be sufficiently far from the inlet port to reduce the effects of bolus flow fluctuations on convection of the viral progeny, but its location was also selected to have adequate downstream area for detection of the flow-enhanced infection spread; this location has not been optimized. To prepare devices masks were drawn by Adobe Illustrator 10.0.3 and printed on transparencies with 3,000 dpi resolution (Imagesetter Inc., Madison, WI), and two-layer masters were created with EPON SU-8-100 (Microchem Corp., Newton, MA) on silicon wafers. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, Midland, WI) microchannels were molded from the masters and place directly into tissue culture dishes with 35 mm in diameter (BD Falcon). The microfluidic devices were sterilized under UV for 30 min and pre-warmed at 37°C for at least 1 h before cell loading.

2.2 Cell culture and counting

Baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells were grown as mono-layers at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Growth medium consisted of Minimum Essential Medium Eagle with Earle’s Salts (MEM, Cellgro), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone), and 2 mM Glutamax I (Glu, Gibco). To form confluent monolayers, cells were injected into microchannels at 4 × 106 cells/ml through one end port or seeded in six-well culture plates at 2.5 × 105 cells/ml with 2 ml/well. The cells were cultured for 12 h before adding virus.

To measure the cell surface density (cells per area) samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde(w/v), stained with DAPI (Pierce) and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted epifluorescent microscope equipped with a monochrome SensSys 4.0 cooled CCD camera driven by MetaMorph 4.0 software(Universal Imaging). Cells across an area of 0.63 mm2 were identified by using a Matlab program developed by Blair and Dufresne (http://www.physics.emory.edu/~weeks/idl/), and 100 to 1,000 cells were typically counted. Cell densities measured at one fourth, two fourths, and three fourths down the length of a channel or across the diameter of a culture well were averaged to provide a representative value for each cell seeding condition.

2.3 Immunocytochemistry

PDMS microchannels were peeled off the cell-culture plate after fixation. Cell monolayers were then treated with a monoclonal antibody (V5507, Sigma) against VSV-glycoprotein (VSV-G). After 1 h cells were rinsed and overlaid with a Cy3-conjugated affinipure F(ab′)2 fragment donkey anti-mouse antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) and incubated 1 h. During antibody labeling, samples were covered with foil and seated on an Orbitron Rotator II (Model 260250, Boekel Scientific) set at its highest speed. Finally monolayers were washed to remove unbound antibodies and stored in PBS at 4°C until ready for imaging.

2.4 Infections in microchannels in the absence of flow

Confluent BHK cell monolayers were infected with different virus levels. Channel ports were covered with slices of PDMS to minimize evaporation and thereby maintain static fluid conditions. They were then incubated, and immunolabelled for VSV-G and stained with DAPI for cell nuclei at 15 h post-infection.

2.5 One-step virus growth

We used a recombinant form of VSV, generously provided by Sean Whelan, carrying the gene for green fluorescent protein (GFP) inserted between the leader and the gene for nucleocapsid protein (3′ leader-GFP-N-P-M-G-L-trailer 5′). When this virus, VSV-GFP, infects cells GFP is expressed early in the replication cycle. BHK cell monolayers were infected by VSV-GFP at MOI 5 and incubated 1 h at 37°C to allow adsorption. Cells were then rinsed with HBSS to remove unbound virus and cultured in infection medium consisting of MEM, 2% FBS and 2 mM Glu. At the indicated times post infection, supernatants were sampled and stored at −80°C until quantification by plaque assay. The one-step growth of virus (v) was fit to the following model:

where this first-order behavior with delay is the simplest description of the dynamics that reflects three biologically meaningful parameters: k is the overall yield of virus progeny, a is the rate of virus production, and d is a time delay.

2.6 Flow-enhanced spread of localized infections in microchannels

Channels containing confluent BHK monolayers were inoculated with virus by passive pumping (Walker and Beebe 2002). A 20 μl-droplet of infection medium was initially seated at the outlet port, and 1 μl of VSV-GFP was then seated at the inoculation port, generating a pressure drop between the inoculation and outlet ports that allowed the infection droplet to enter the channel. After 12 h of incubation at 37°C, a bolus droplet of infection medium was introduced into the channel by seating a droplet at the inlet port. After an additional 12 h of incubation, GFP signal produced from virus replication was imaged, and the infected cell monolayers were treated with fixative and stained with crystal violet. Average GFP intensity was quantified by a Matlab program, which read the fluorescent images and calculated the average pixel value of each channel. Alternatively, the area of cytopathic effect was quantified by another Matlab program, which read the phase-contrast images, identified and measured bright areas against dark background.

2.7 Plaque-reduction assay

Cell monolayers in six-well culture plates were infected with 200 μl of virus suspension containing approximately 50 to 100 PFU per well. After 1 hour of adsorption at 37°C, the inoculum was removed and the monolayers were overlaid with 2 ml of 0.6% agar (w/v) containing FU. At 24 HPI, cells were treated with fixative, stained with crystal violet, and the plaques were counted. By using as reference the number of plaques obtained in the controls (untreated and infected cultures), the drug concentrations required to reduce the number of plaques by 50% (IC50) were calculated from the dose-response curves. Each sample had three replicas based on running three separate experiments in parallel.

2.8 Statistical analysis

The difference between a number and a group was analyzed by Student’s t distribution. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results and discussion

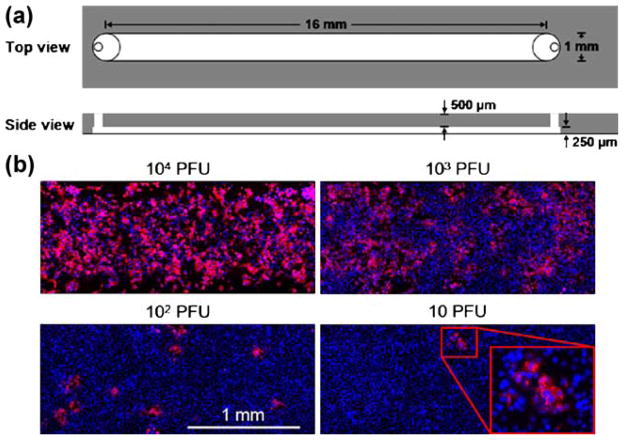

Because confluent host-cell monolayers have served as a substrate for growing viruses and visualizing infection spread in plaque and flow-enhanced infection assays, we initially compared cell monolayers in a two-port microfluidic device [Fig. 2(a)] with those formed in conventional culture plates. In microchannels, measured cell seeding densities were within 15% of the predicted values. However, in standard culture plates, measured cell densities were about 45% below predicted values (see Supplementary Fig. 1). By visual inspection, cells in culture plates appeared to accumulate along the periphery of each well, corresponding with the rise of the fluid meniscus next to the wall of the well, perhaps compensating for lower cell densities across the culture plate. By contrast, cells in microchannels appeared to be uniformly distributed, without detectable accumulation along channel walls. BHK cells seeded into a microchannel at 4 × 106 cells/ml (equivalent to 1000 cells/mm2) spread and formed confluent monolayers after 4 h (see Supplementary Fig. 1). BHK cells were viable in microchannels for at least 4 days, but they grew at lower rates than those in culture plates with medium refreshed every 24 h (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Slower cell growth in microchannels might be attributed to a lack of nutrients or an accumulation of factors that inhibit cell proliferation (Kim et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2007b). Different cell lines have exhibited higher growth rates with more frequent replenishment of growth medium (Kim et al. 2006; Tourovskaia et al. 2005).

Fig. 2.

Virus infections in microchannels spread locally in the absence of flow. (a) Schematic of microfluidic channel for culture of cells and virus in the absence of fluid flow. (b) Effects of added virus level on infection patterns. Virus levels spanned from 104 plaque-forming units (PFU) per channel to 10 PFU per channel. Viral gene expression was visible by immuno-staining the viral glycoprotein (red) and cells were labeled by nuclear stain (blue). The magnified window at 10 PFU/channel highlighted a localized region of viral gene expression, initiated by the infection of one cell by a single viral particle that spread across multiple cells

Four confluent cell monolayers were infected with virus levels spanning a 1,000-fold range under static fluid conditions. Cell monolayers were uniformly infected at the highest virus concentration (104 PFU/channel), while distinct patches of infection were visible at the lowest concentration (10 PFU/channel), based on detection of immunolabeled VSV-glycoprotein (Fig. 2b). At the lower levels of 102 and 10 PFU/channel, the number of patches correlated with the number of added virus particles, indicating that the formation of each patch was initiated by a single virus particle, analogous to plaque formation. Moreover, each patch contained multiple cell nuclei (blue), indicating that infections spread beyond the initial infected cell. These results show that viruses can grow and their infections can spread in microchannels. Further, the quantitative production of viruses based on one-step growth experiments exhibited similar kinetics and overall yields of infection for viruses grown in microchannels and conventional culture plates (Supplementary Fig. 3). Similar productivities in microscale and conventional virus cultures were also recently reported for retrovirus production (Vu et al. 2008). One might have expected the kinetics and productivity of virus infections to reflect differences in areal density and growth rates for the host cells in microchannels versus in culture plates. However, our measurements of cell state and virus productivity do not reflect the extent of cell heterogeneity on virus production in either environment. By applying recent refinements in the measurement of virus production from single cells (Zhu et al. 2008) we anticipate that greater insight into differences between culture environments will emerge.

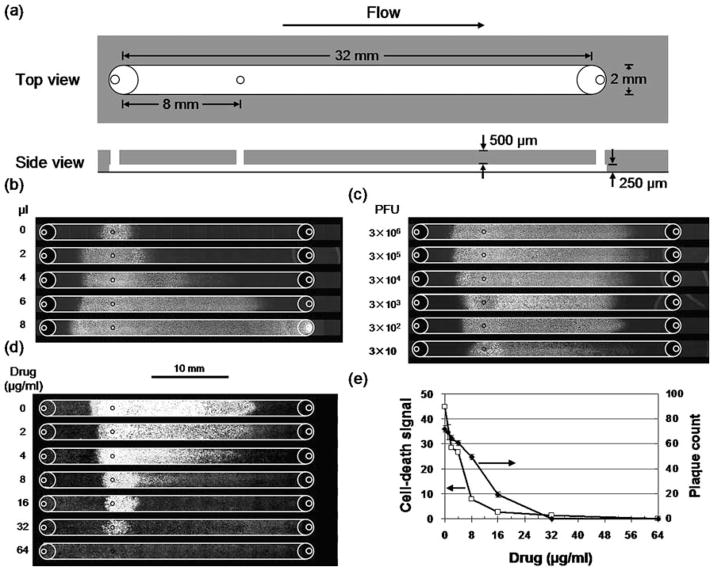

To demonstrate the effects of fluid flow on infections, we designed a three-port microchannel (Fig. 3a) that would allow us to perform infections as a three-step process: (1) formation of a susceptible host-cell monolayer, (2) initiation of infection by localized addition of virus, and (3) spread of virus by fluid flow. To carry out these steps, cells were injected into the microchannel, and fluid droplets containing viruses or growth medium, respectively, were driven through the device by passive pumping (Walker and Beebe 2002). The extent of infection spread correlated with the volume of fluid added (Fig. 3b), where the maximum volume of 8 μl was sufficient to drive the infection beyond the end of the channel into the outlet port. Apparent backward spread of infection opposing the direction of bolus flow may have arisen owing to evaporation from the inlet port, supplied with fluid through the channel from the large droplet at the outlet port used in passive pumping (Walker and Beebe 2002). A smaller extent of spread may be attributed to diffusion of VSV particles, which move about 1 mm in 24 h for a diffusion coefficient of 2.3 × 10−8 cm2/s (Ware et al. 1973). To most effectively utilize the channel capacity we selected 6 μl droplets to drive infection spread in subsequent experiments. Effect of virus concentration on the flow-enhanced infection spread was tested by inoculating cells with different numbers of virus particles spanning a 105 -fold range. Spatial patterns of infection and intensities of cytopathology were similar for inocula containing from 300 to 3 million virus particles, but dropped significantly when the inoculum contained only 30 virus particles (Fig. 3c), suggesting that an initial infection of 300 cells, but not 30 cells, produces sufficient virus progeny to saturate the infection capacity of the channel. For an average yield of 2,100 virus particles/cell, 30 infected cells would produce 6.3 × 104 virus particles, which would have access to 4.8 × 104 cells, assuming the 6-μl bolus flow with a parabolic profile and the real density of the cell monolayer of 1,000 cells/mm2. The corresponding multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1.3 would enable 74% of the available cells to be infected, assuming virus particles were distributed to cells following a Poisson process. By contrast, an initial inoculum containing 300 or more virus particles would result in a greater than 99% infection of the available cells. These calculations, based on quantitative measures of virus yields, cell availability, and flow behavior, are consistent with the observed dependence of infection pattern on inoculum size.

Fig. 3.

Fluid flow enhanced the spread of virus infections in microchannels. (a) Schematic of channel for virus infections in the presence of fluid flow. An inoculation port (diameter 0.5 mm) near the inlet port enabled localized initiation of infections. Volumes were 16 μl (channel) and 2 μl (each port). (b) Larger bolus volumes enhanced infection spread. Cell monolayers were locally inoculated with virus, incubated, subjected to bolus flows, further incubated, and GFP signals were detected. (c) Smaller inoculum sizes (PFU) reduced infection spread. Inocula containing 300 to 3 million PFU produced similar patterns of infection-mediated GFP expression for 6 μl bolus flows. However, an inoculum containing 30 PFU spread a shorter distance (p=0.0005) and its GFP intensity was lower (p=0.0008) than the others. (d) Higher drug levels inhibited virus infection spread. Cell monolayers were inoculated with 300 PFU, and both inocula and bolus flows contained the anti-viral drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Regions of cell death (white) were visualized by staining with crystal violet. (e) Microfluidic infection assay was more sensitive than the plaque-reduction assay. Levels of drug treatments that were needed to achieve half-maximal infection (IC50) were 5 μg/ml (microfluidic infection assay) and 12 μg/ml (plaque-reduction assay)

When flow-enhanced infections were treated with increasing levels of an anti-viral drug, the spatial extents and overall intensities of infection spread decreased monotonically, based on measures of infection-mediated cell death [Fig. 3(d, e)]. For each concentration of drug tested, the microfluidic infection assay required only 1/80 of the amount of drug needed in the plaque-reduction assay. Moreover, measures of assay sensitivity, based on drug concentrations that reduce infectivity by 50% (IC50), indicated that the flow-enhanced infection assay was twofold more sensitive than the ‘gold-standard’ plaque-reduction assay [Fig. 3(e)]; similar IC50 values were obtained for the effects of drug on infection-mediated gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 4). Higher assay sensitivities may be achievable based on drug treatments that inhibit the formation of individual flow-elongated plaques or ‘comets’ that have been initiated by single cells infected by single virus particles (Zhu and Yin 2007). Finally, we imagine that the implementation of infection assays in microchannels will enable their use in high-throughput assays for drug testing. The approach would employ multiple arrays of microchannels spatially arranged to interface with existing automated pipetting and detection platforms, as previously described for cell biology assays (Yu et al. 2007a).

4 Conclusions

Our implementation of live-cell infection assays in a microfluidic device creates advantages over conventional plaque-based assays that may open new applications. First, the assay is sensitive. Flows enhance amplification of the infection signal, providing more sensitive infection readout than the conventional plaque assays. Second, the assay is simple. It may be performed by pipeting of fluid droplets, incubation and imaging of the resulting infection patterns, processes that are amenable to automation. Third, the assay is small. The significant reduction in scale will enable infection assays to be expanded to drug-screening applications where test drugs are only available in small quantities. Finally, the assay is expandable. It can be readily modified to test the effects of diverse compounds on infection including antisera or antibodies, chemokines or cytokines, and emerging anti-viral therapeutics and strategies such as RNAi. Moreover, it will be applicable to other viruses that cause detectable cytopathic effects including HIV, herpes virus, adenovirus and influenza virus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hongmei Yu, Ivar Meyvantsson, Hyungjin Kim, and Jongil Ju for technical assistance and helpful discussions. VSV-GFP was generously provided by Sean Whelan (Harvard Medical School). This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21 AI071197, K25 CA104162) and the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10544-008-9263-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Ying Zhu, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Jay W. Warrick, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA

Kathryn Haubert, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

David J. Beebe, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA

John Yin, Email: yin@engr.wisc.edu, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

References

- Beebe DJ, Mensing GA, Walker GM. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.112601.125916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ali J, Sorger PK, Jensen KF. Nature. 2006;442(7101):403–411. doi: 10.1038/nature05063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JW, Quake SR. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(10):1179–1183. doi: 10.1038/nbt871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung G, Fong C, Landry M. Hsiung’s Diagnostic Virology: as Illustrated by Light and Electron Microscopy. 4. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kim L, Vahey MD, Lee HY, Voldman J. Lab Chip. 2006;6(3):394–406. doi: 10.1039/b511718f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam V, Duca KA, Yin J. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;90(7):793–804. doi: 10.1002/bit.20467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petric M, Comanor L, Petti CA. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(Suppl 2):S98–S110. doi: 10.1086/507554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourovskaia A, Figueroa-Masot X, Folch A. Lab Chip. 2005;5(1):14–19. doi: 10.1039/b405719h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu HN, Li Y, Casali M, Irimia D, Megeed Z, Yarmush ML. Lab Chip. 2008;8(1):75–80. doi: 10.1039/b711577f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker GM, Beebe DJ. Lab Chip. 2002;2(3):131–134. doi: 10.1039/b204381e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker GM, Ozers MS, Beebe DJ. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2004;98(2–3):347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2003.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware BR, Raj T, Flygare WH, Lesnaw JA, Reichmann ME. J Virol. 1973;11(1):141–145. doi: 10.1128/jvi.11.1.141-145.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesides GM. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(10):1161–1165. doi: 10.1038/nbt872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations on the Use of Rapid Testing for Influenza Diagnosis. WHO; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yin J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;174(2):1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/0006–291X(91)91519-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Alexander CM, Beebe DJ. Lab Chip. 2007a;7(3):388–391. doi: 10.1039/b612358a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Alexander CM, Beebe DJ. Lab Chip. 2007b;7(6):726–730. doi: 10.1039/b618793e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Yin J. J Virol Methods. 2007;139:100–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Yongky A, Yin J. Growth of an RNA virus in single cells reveals a broad fitness distribution. Virology. 2008 Dec 12; doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.