Abstract

The responsiveness of central noradrenergic systems to stressors and cocaine poses norepinephrine as a potential common mechanism through which drug re-exposure and stressful stimuli promote relapse. This study investigated the role of noradrenergic systems in the reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-induced conditioned place preference by cocaine and stress in male C57BL/6 mice. Cocaine- (15 mg/kg, ip) induced conditioned place preference was extinguished by repeated exposure to the apparatus in the absence of drug and re-established by a cocaine challenge (15 mg/kg), exposure to a stressor (6-min forced swim; FS; 20–25°C water), or administration of the alpha-2 adrenergic receptor (AR) antagonists yohimbine (2 mg/kg, ip) or BRL44408 (5, 10 mg/kg, ip). To investigate the role of ARs, mice received the non-selective beta AR antagonist, propranolol (5, 10 mg/kg, ip), the alpha-1 AR antagonist, prazosin (1, 2 mg/kg, ip), or the alpha-2 AR agonist, clonidine (0.03, 0.3 mg/kg, ip) prior to reinstatement testing. Clonidine, prazosin, and propranolol failed to block cocaine-induced reinstatement. The low (0.03 mg/kg) but not high (0.3 mg/kg) clonidine dose fully blocked FS-induced reinstatement but not reinstatement by yohimbine. Propranolol, but not prazosin, blocked reinstatement by both yohimbine and FS, suggesting involvement of beta ARs. The beta-2 AR antagonist ICI-118551 (1 mg/kg, ip), but not the beta-1 AR antagonist, betaxolol (10 mg/kg, ip) also blocked FS-induced reinstatement. These findings suggest that stress-induced reinstatement requires noradrenergic signaling through beta-2 ARs and that cocaine-induced reinstatement does not require AR activation, even though stimulation of central noradrenergic neurotransmission is sufficient to reinstate.

Keywords: Relapse, norepinephrine, propranolol, prazosin, clonidine, beta adrenergic receptors, ICI-118551

INTRODUCTION

The sudden re-emergence of cocaine craving even after protracted periods of abstinence and the resulting relapse of drug use represent formidable obstacles to the effective management of cocaine addiction. Anecdotal reports and clinical and preclinical research have identified stress and cocaine re-exposure as likely precipitating events for drug relapse (Shaham, et al 2000; Sinha, 2001; Shaham, et al 2003; Stewart, 2003; Lu, et al 2003). Understanding the neurobiological mechanisms that contribute to drug relapse in response to these stimuli should lead to the development of new and more effective approaches for treating addiction.

The preclinical study of relapse involves the use of reinstatement protocols in which the ability of various stimuli to re-establish extinguished drug-seeking behavior is examined (Shaham, et al 2003). For example, in rats and monkeys, cocaine administration or exposure to a variety of stressors will reinstate extinguished lever pressing that was previously reinforced by cocaine delivery (see Shaham, et al 2000; Sinha, 2001; Shaham, et al 2003; Stewart, 2003; Lu, et al 2003 for reviews). Relapse can also be investigated using a conditioned place preference reinstatement approach in which the ability of stimuli to re-establish extinguished preference for a previously cocaine-paired environment is examined (Tzschentke, 2007). In mice, extinguished cocaine-induced conditioned place preference can be reinstated by administration of a priming injection of cocaine (Itzhak and Martin, 2002; Orsini, et al 2008) or by exposure to stressors, including, social stress (Ribeiro Do Couto, et al 2006), uncontrollable electric footshock (Redila and Chavkin, 2008), or forced swim (Kreibich and Blendy, 2004). The use of mouse reinstatement models is important in that it should facilitate the application of genetic approaches not available in other species to further advance understanding of relapse substrates.

The responsiveness of central noradrenergic systems to both stressors (Abercrombie, et al 1988; Tanaka, et al 1991; Finlay, et al 1995) and cocaine (Reith, et al 1997; Li, et al 1996) poses norepinephrine (NE) as a potential common mechanism through which drug re-exposure and stressful environmental stimuli promote relapse. Accordingly, previous studies have suggested that antagonizing adrenergic receptors (ARs; Leri, et al 2002; Zhang and Kosten, 2005) or suppressing noradrenergic neurotransmission (Erb, et al 2000; Platt, et al 2007) can attenuate cocaine seeking while augmenting adrenergic neurotransmission through antagonism of alpha-2 adrenergic autoreceptors (Lee, et al 2004; Feltenstein and See, 2006; Fletcher, et al 2008; Brown, et al 2009) or blockade of reuptake (Platt, et al 2007; but see Schmidt and Pierce, 2006) can evoke cocaine seeking as measured using reinstatement protocols. Considering that in human cocaine addicts, drug craving is associated with a robust peripheral adrenergic response (Sinha et al, 2003) that appears to be augmented during early withdrawal (McDougle, et al 1994) and that repeated cocaine exposure produces long-lasting adaptations within central noradrenergic systems that may lead to enhanced noradrenergic responsiveness during stress (Belej, et al 1996; Macey, et al 2003; Baumann, et al 2004; Beveridge, et al 2005; Lanteri, et al 2008), central noradrenergic signaling may represent an important therapeutic target for the prevention of relapse (Weinshenker and Schroeder, 2007; Smith and Aston-Jones, 2008; Sofuoglu and Sewell, 2009).

The present study investigated the role of noradrenergic systems in the reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-induced conditioned place preference by cocaine and stress in adult male C57 BL/6 mice. The effects of the alpha-1 AR antagonist, prazosin, the beta AR antagonists, propranolol, betaxolol, and ICI-118551, and the alpha-2 AR agonist, clonidine on reinstatement by cocaine, forced swim (FS) stress, and/or the alpha-2 AR antagonist, yohimbine were examined. Our findings suggest that noradrenergic activation of beta-2 ARs is selectively involved in stress-induced reinstatement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A total of 250 male C57BL/6 mice, 8–9 weeks old at the start of the study (Harlan) were used. Mice were housed singly in a temperature- and humidity-controlled, AAALAC-accredited animal facility under a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM) and had access to food and water at all times, except when in the experimental chambers. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the NIH.

Drugs

Cocaine HCl was acquired from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) through the NIDA Drug Supply Program. Clonidine HCl,, ±propranolol HCl, betaxolol HCl, ICI-118551 HCl and yohimbine HCl were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. BRL 44408 maleate was acquired from Tocris Bioscience. Yohimbine, prazosin and clonidine were dissolved in sterile water. Cocaine, propranolol, betaxolol, ICI-118551, and BRL 44408 were dissolved in saline (0.9% NaCl solution). All drug solutions were administered IP in a volume of 0.1 ml/20 g body mass.

Equipment

Behavioral testing was conducted using four ENV-3013 mouse place preference chambers from Med-Associates, Inc. The stainless steel and polyvinyl chloride chambers consisted of three distinct compartments separated by 5 cm w × 5.9 cm high manual guillotine doors. The two 46.5 × 12.7 × 12.7 cm side compartments consisted of a white compartment with a 6.35 × 6.35 mm stainless steel mesh floor and a black compartment with a stainless steel grid rod floor consisting of 3.2 mm rods spaced 7.9 mm apart. The side compartments were attached via a gray-colored 7.2 cm long center compartment with a smooth floor. The clear tops of the compartments were hinged to permit placement and removal of the mice. Ceiling lights were attached to each top. To balance unconditioned side preference, only the light in the black compartment was illuminated during training/testing. Automated data collection was accomplished using photobeams (6 beams for the white and black test areas and 2 beams for the center gray area) which were evenly spaced across the length of the chamber and interfaced with a computer containing Med-PC software. Using this automated photobeam system, entry into a side compartment was defined as consecutive breaks of the first two photocell beams in that compartment located adjacent to the door separating that compartment from the center compartment. Exiting of a side compartment (and entry into the center compartment) was indicated by occlusion of the beams in the center compartment.

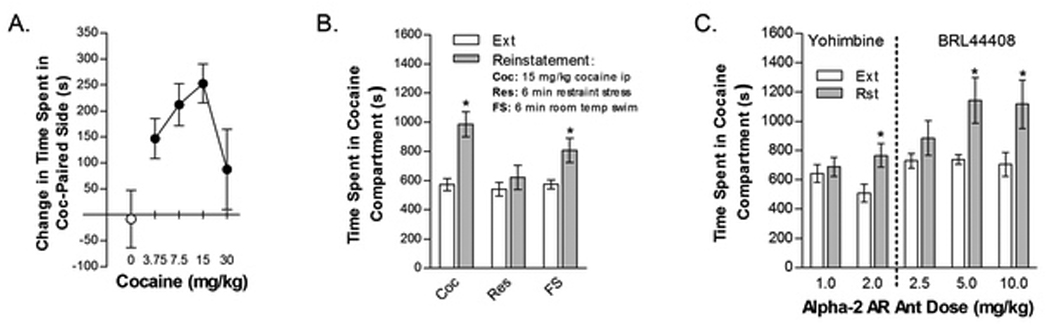

Cocaine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference

Cocaine-induced conditioned place preference was established using a design in which one of the side compartments was randomly designated as the cocaine compartment and the other as the saline compartment. On the first day of the procedure, mice were placed into the center compartment of the chamber and provided free access to both side compartments for 30 minutes in the absence of saline or cocaine pretreatment to determine pre-conditioning preference. During the 8-day conditioning phase of the experiment, mice received cocaine (15 mg/kg, ip) and saline injections on alternating days after which time they were confined to the randomly designated treatment-appropriate compartment for 30 minutes. After the final conditioning session, mice were tested for the expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference by once again placing them into the center compartment of the chamber and providing them with free access to the side compartments for 30 minutes. Conditioned place preference was defined as the change in time spent (sec) within the cocaine-paired compartment after conditioning when compared to the initial pre-conditioning session. The 15 mg/kg cocaine dose was selected based on the results of a preliminary study in which the ability of various cocaine doses to produce place preference was examined (Fig 1A).

Figure 1.

Induction and reinstatement of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Cocaine dose-dependently induced conditioned place preference with peak effects at the 15 mg/kg (ip) dose. Data in Fig 1A represent the mean change in time spent (sec ± SE) in the cocaine-paired compartment between the pre- and post-conditioning test sessions in mice that were conditioned with various cocaine doses (0–30 mg/kg, ip; n=10–20/group). Based on these data, the 15 mg/kg cocaine dose was selected as the conditioning and reinstatement dose for each experiment. Figures 1B and 1C show the reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-induced conditioned place preference by cocaine (Coc; 10 mg/kg, ip; n=23; Fig 1B), physical restraint (Res; n=26; Fig 1B), forced swim (FS; n=16; Fig 1B) and by the alpha-2 AR antagonists yohimbine (Yoh; 1 and 2 mg/kg, ip; n=23; Fig 1C) and BRL 44408 (BRL; 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg, ip; n=6–8; Fig 1C). Data represent the time spent in the Coc compartment (sec ± SE) during the 30-min reinstatement (Rst) session (filled bars) or during the preceding extinction session (open bars). Coc, FS, 2 mg/kg Yoh, and 5 and 10 mg/kg BRL but not Res, 1 mg/kg Yoh or 2.5 mg/kg BRL, produced significant reinstatement (*P<0.05 vs. Ext).

Extinction

Following conditioning, daily extinction training was conducted. During the extinction sessions, mice were placed into the center compartment and once again provided with free access to the side compartments for 30 min. Mice underwent daily extinction training until the preference for the cocaine-paired compartment during the session (i.e., change in time spent in the cocaine side relative to pre-conditioning values) was reduced by at least 50% compared to the post-conditioning test session, at which time reinstatement testing was conducted.

Reinstatement Testing

The reinstatement sessions were identical to the extinction sessions except that mice received exposure to stressors and/or drug injections prior to the session. Reinstatement was defined according to the time spent in the compartment previously paired with cocaine. Mice were tested more than once for reinstatement. Generally, each mouse was tested with each of the three reinstating stimuli (cocaine, forced swim [FS], and yohimbine) alone and in combination with one drug pretreatment and its respective vehicle in counter-balanced order to avoid potential sequence effects. Reinstatement sessions were separated by additional extinction sessions. Mice were required to reach the extinction criterion once again before the next reinstatement test was conducted. Initially, separate groups of mice were tested for the ability of various stressors and drugs, when delivered in the absence of pretreatments, to produce reinstatement.

Drug-Induced Reinstatement

Cocaine- and yohimbine-induced reinstatement testing was conducted by injecting mice with cocaine (15 mg/kg, ip) or yohimbine (1 or 2 mg/kg, ip) either alone or 30 min after pretreatment with clonidine (0.03 and 0.3 mg/kg), propranolol (5 and 10 mg/kg), prazosin (1 and 2 mg/kg), betaxolol (10 mg/kg), ICI-118551 (1 mg/kg) or their respective vehicles and placing mice into the center compartment five minutes later with free access to both sides for 30 min. Reinstatement by clonidine, propranolol, prazosin, betaxolol, and ICI-118551 alone was also tested following administration 30 min prior to the reinstatement session, a time-point that matched the pretreatment time when these drugs were administered prior to cocaine, yohimbine or FS during testing. To confirm that antagonism of alpha-2 AR by yohimbine may have contributed to reinstatement, a separate group of mice was tested for reinstatement in response to the highly selective alpha-2 AR antagonist, BRL 44408 (2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg, ip).

Stress-Induced Reinstatement

FS-induced reinstatement was examined by placing mice into a 30 cm h× 20 cm d cylindrical polypropylene container filled with water (20–25° C) for six min, 30 min after pretreatment with clonidine (0.03 and 0.3 mg/kg), propranolol (5 and 10 mg/kg), prazosin (1 and 2 mg/kg) or their respective vehicles. Following FS, mice were placed back into their home cages for 3–4 min prior to introduction into the center compartment of the place conditioning chamber with free access to both of the side compartments for reinstatement testing, as described above. Initially, some mice were also tested for reinstatement following five minutes of physical restraint using a mouse restrainer cone (5.7 cm diameter tapered to 1.2 cm diameter; 11 cm length). These mice were also returned to their home cages after restraint for 3–4 minutes prior to placement into the apparatus for reinstatement testing. Since propranolol blocked FS-induced reinstatement, we also tested mice for the effects of the selective beta-1 AR antagonist, betaxolol (10 mg/kg, ip) and the selective beta-2 AR antagonist, ICI-118551 (1 mg/kg, ip) on reinstatement following FS.

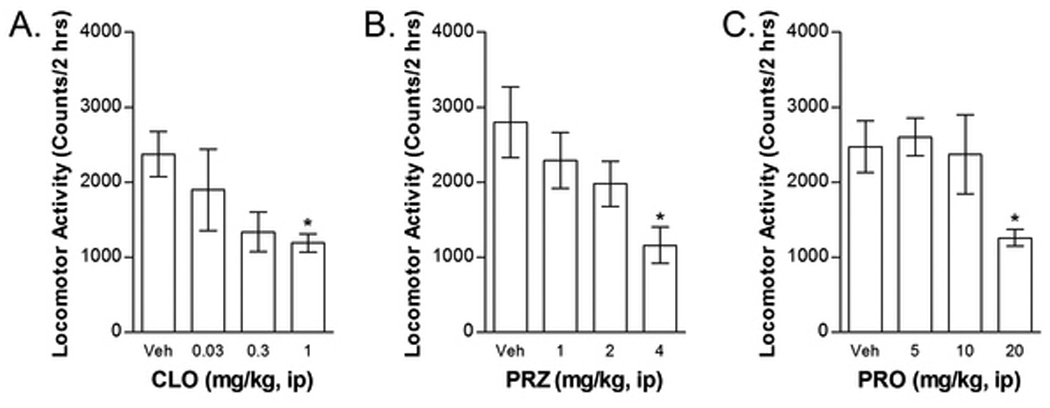

Locomotor Testing

To assist with dose selection, the effects of various doses of clonidine, prazosin, and propranolol on locomotor activity were tested in 26 total mice using an automated AccuScan activity system (AccuScan Instruments, Inc., Columbus, OH) consisting of a frame containing photocells (eight per cage) in which clear Plexiglas 29.5 cm l× 19 cm w× 12.7 cm h cages were placed. Activity was measured as total photobeam breaks. During the week prior to locomotor testing, mice were habituated to the test environment during two 2-h sessions. On the test day, mice were placed into the chambers for two hrs prior to drug administration after which activity was measured over a 2-h period. The effects of clonidine (0, 0.03, 0.3 and 1 mg/kg, ip), prazosin (0, 1, 2, and 4 mg/kg, ip), and propranolol (0, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg, ip) were tested in separate groups of mice. Only doses that failed to produce statistically significant reductions in activity were tested for effects on reinstatement.

Statistical Analyses

Place preference during testing, extinction and reinstatement was defined as the time spent (sec) in the designated cocaine compartment. The abilities of individual stimuli to reinstate place preference in the absence of drug pretreatments were examined statistically using 2-tailed student’s t-tests comparing time spent in the cocaine compartment during the prior extinction session with that during the reinstatement session. The significance of the effects of drug pretreatments on reinstatement by each of the stimuli was determined using 2-way repeated measures reinstatement x drug pretreatment ANOVA followed by post-hoc testing using 2-tailed student’s t-tests. The significance of dose-related drug effects on locomotor activity were determined using one-way (drug dose) ANOVA followed by post-hoc testing using the Dunnett’s test. For all analyses, significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Establishment and reinstatement of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference

Dose-response analysis demonstrated that the 15 mg/kg cocaine dose was optimal for producing conditioned place preference (n=10–20 mice per cocaine/veh dose; Fig. 1A). Although not shown, significant cocaine-induced conditioned place preference, defined as an increase in time spent in the cocaine-paired compartment, was observed in each of the experiments in which reinstatement was later examined (P<0.05 for each experiment). The overall average number of extinction sessions prior to the first reinstatement test session was 8.757. Overall, 28 mice (out of 224 that underwent conditioning) were not tested for reinstatement because they either did not display cocaine-induced conditioned place preference or failed to reach the extinction criterion.

The ability of cocaine and stress to reinstate extinguished cocaine-induced place preference is shown in Figure 1B. Administration of 15 mg/kg cocaine (t22=4.949; n=20) or FS (t15=3.128; n=16), but not restraint (n=26), significantly increased time spent in the cocaine compartment following extinction (P<0.01).

To determine if stimulating central noradrenergic neurotransmission through antagonism of alpha-2 AR is sufficient to induce reinstatement, mice were tested for the ability of yohimbine and the more selective alpha-2A AR antagonist, BRL 44408, to reinstate extinguished place preference (Fig 1C). For yohimbine, a 2-way reinstatement condition (repeated measure) x yohimbine dose (1 vs. 2 mg/kg) ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of reinstatement condition (F1,33=5.252; P<0.05) but not yohimbine dose, and a significant reinstatement condition x dose interaction (F1,33=4.089; P=0.05). The 2 mg/kg (t22=3.371; n=23), but not 1 mg/kg (n=23), yohimbine dose produced significant reinstatement (P<0.01). Although yohimbine can increase central noradrenergic neurotransmission through antagonism of alpha-2 ARs, it also binds to a number of other receptors, including the 5-HT1A receptor, where it acts as an antagonist and may produce effects independently of the noradrenergic system (Sanger and Shoemaker, 1992; Winter and Rabin, 1992). To confirm that alpha-2 AR antagonism is sufficient to induce reinstatement, we also tested some mice for reinstatement following administration of the selective alpha-2A AR antagonist BRL 44408 which has a 50-fold higher affinity for alpha-2A AR relative to 5-HT1A receptors (Dwyer, et al 2010). A 2-way repeated measures reinstatement condition x BRL 44408 dose (2.5, 5.0, 10.0 mg/kg) ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of reinstatement condition (F1,6=13.557; P=0.01) but not BRL 44408 dose, and a significant reinstatement condition x dose interaction (F2,12=4.222; P<0.05). Like yohimbine, BRL 44408 dose-dependently reinstated, with significant effects observed at the 5 (t6=2.776; P<0.05) and 10 (t7=2.538; P<0.05), but not the 2.5, mg/kg BRL 44408 doses.

Locomotor Testing

Propranolol, prazosin, and clonidine each produced dose-dependent reductions in locomotor activity (Figure 2). One-way prazosin dose ANOVA examining the effects of 1, 2, and 4 mg/kg prazosin on locomotor activity showed a significant overall effect (F1,36=3.300; P<0.05). Post-hoc testing using a Dunnett t-test showed that the 4 mg/kg dose, but not the other prazosin doses, significantly reduced locomotor activity compared to vehicle-treated controls (P<0.01). Likewise, one-way propranolol dose ANOVA examining the effects of 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg propranolol on locomotor activity showed a significant overall effect (F1,36=3.244; P<0.05). Post-hoc testing using a Dunnett t-test showed that the 20 mg/kg dose, but not the other propranolol doses, significantly reduced locomotor activity compared to vehicle-treated controls (P<0.05). One-way clonidine dose ANOVA examining the effects of 0.03, 0.3, and 1 mg/kg clonidine on locomotor activity failed to show a significant overall effect of clonidine, despite a near-significant trend (F3,33=2.693; P=0.06). Post-hoc testing using a Dunnett t-test showed that the 1 mg/kg dose, but not the other clonidine doses, significantly reduced locomotor activity compared to vehicle-treated controls (P<0.05). Since, 4 mg/kg prazosin, 20 mg/kg propranolol, and 1 mg/kg clonidine produced significant reductions in locomotor activity, we chose not to test the effects of these doses on reinstatement.

Figure 2.

Effects of clonidine (CLO; Fig 2A), prazosin (PRZ; Fig 2B), and propranolol (PRO; Fig 2C) or their respective vehicles (Veh) on locomotor activity. To facilitate dose selection, mice (n=6–10 per dose) were tested for the effects of CLO, PRZ, and PRO on locomotor activity. Data represent locomotor counts (total photobeam breaks) measured during a 2-h session that immediately followed drug administration. Each drug dose-dependently attenuated locomotor activity (*P<0.05; significant reduction vs. Veh).

Reinstatement by prazosin, propranolol, clonidine, betaxolol and ICI-118551

To ensure that the alpha-1 AR antagonist prazosin, the beta AR antagonists propranolol, betaxolol and ICI-118551 and the alpha-2 AR agonist clonidine did not, by themselves, alter preference for the cocaine compartment following extinction, we initially examined the ability of these drugs, when administered alone, to reinstate extinguished conditioned place preference at the doses to be used (Table 1). Whereas prazosin (1 mg/kg; n=12 or 2 mg/kg; n=14), propranolol (5 mg/kg; n=8 or 10 mg/kg; n=10), betaxolol (10 mg/kg; n=12) or ICI-118551 (5 mg/kg; n=12) failed to alter the amount of time spent in the cocaine-paired compartment following extinction, clonidine, at the higher (0.3 mg/kg; t12=2.491, P<0.05; n=13) but not the lower (0.03 mg/kg; n=13) dose, produced significant reinstatement (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Effects of prazosin (Prz), propranolol (Pro), clonidine (Clo), betaxolol (Bet), and ICI-118551 (ICI) on time spent in the cocaine compartment following the extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (n=8–14 per drug). Data represent the time spent in the cocaine compartment (sec ± SE) during the reinstatement session following drug administration (Reinstatement) or during the preceding extinction session (Ext). Only the high (i.e., 0.3 mg/kg) clonidine dose reinstated extinguished conditioned place preference.

| Drug (dose) | Ext | Reinstatement |

|---|---|---|

| Prz (1.0 mg/kg) | 614.84 (±47.81) | 592.86 (±54.40) |

| Prz (2.0 mg/kg) | 583.29 (±24.59) | 673.34 (±85.93) |

| Pro (5.0 mg/kg) | 617.53 (±58.31) | 582.35 (±85.03) |

| Pro (10.0 mg/kg) | 640.60 (±80.72) | 602.77 (±91.61) |

| Clo (0.03 mg/kg) | 583.55 (±70.28) | 613.27 (±75.18) |

| Clo (0.3 mg/kg) | 595.80 (±34.81) | 913.11 (±131.27)* |

| Bet (10.0 mg/kg) | 668.42 (±43.11) | 659.47 (±63.01) |

| ICI (1.0 mg/kg) | 622.45 (±36.01) | 607.18 (±87.56) |

(P<0.05 vs. Ext; n=13)

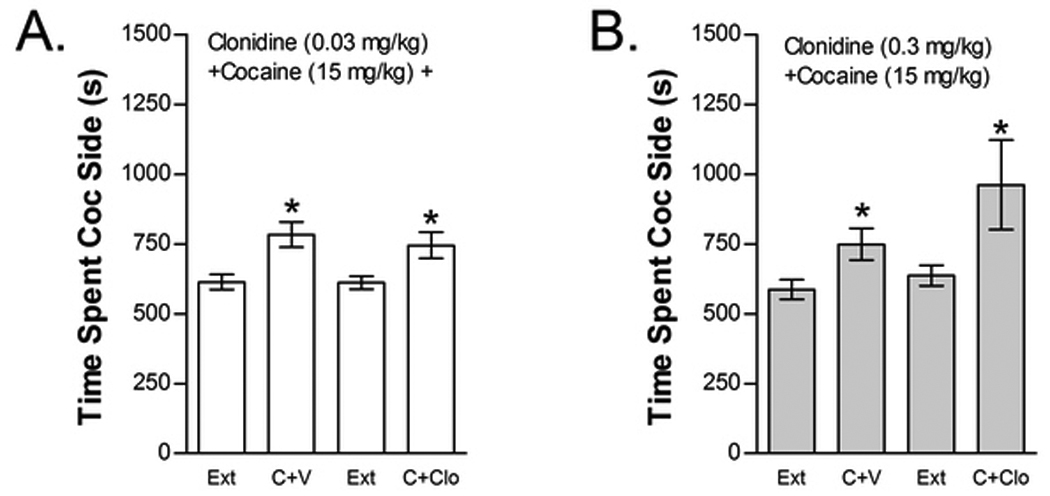

Effects of clonidine on reinstatement

Since augmentation of central noradrenergic neurotransmission via administration of yohimbine or the selective alpha-2A AR antagonist, BRL-44408, induced reinstatement, we hypothesized that noradrenergic neurotransmission during stress or following cocaine exposure may contribute to stress- and cocaine-induced drug seeking. To test this hypothesis, mice were tested for FS- or cocaine-induced reinstatement following administration of clonidine, an alpha-2 AR agonist that suppresses evoked increases in NE (Florin, et al 1994; Tjurmina, et al 1999) presumably via activation of inhibitory autoreceptors on noradrenergic nerve terminals.

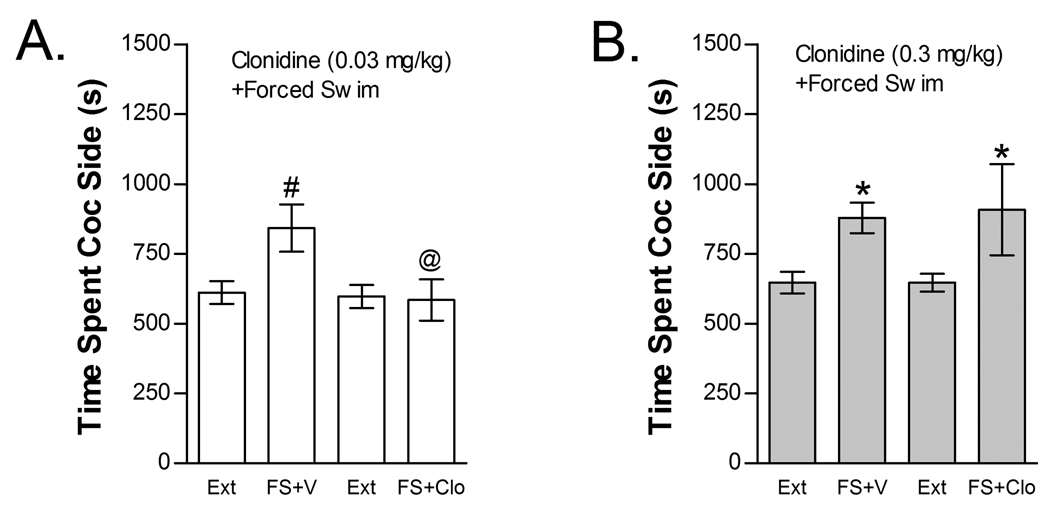

Forced Swim

The effects of clonidine (0.03 and 0.3 mg/kg, ip) on FS-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 3. Clonidine suppressed FS-induced reinstatement, but only at the 0.03 mg/kg dose. Twenty-seven mice were used to test for the effects of 0.03 mg/kg clonidine dose on FS-induced reinstatement (Fig 3A). Two-way repeated measures FS x clonidine treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of FS (F1,26=6.199; P<0.05) but not clonidine treatment condition on time spent in the cocaine compartment and a significant clonidine x FS interaction (F1,26=12.264; P<0.01). Post-hoc examination of reinstatement in each group revealed that FS significantly reinstated place preference in vehicle-treated but not clonidine-treated mice (t26=3.230; P<0.05) and that time spent in the cocaine compartment was significantly reduced by clonidine following FS (t26=3.012; P<0.05). Nine mice were used to test the effects of the 0.3 mg/kg clonidine dose on FS-induced reinstatement (Fig 3B). In contrast to the 0.03 mg/kg clonidine dose, 0.3 mg/kg clonidine failed to block FS-induced reinstatement. Two-way repeated measures FS x clonidine treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of FS (F1,8=6.122; P<0.05) but not of clonidine and no FS x clonidine interaction.

Figure 3.

The The alpha-2 AR agonist clonidine dose-dependently blocks stress-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after forced swim (FS) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or clonidine (Clo). A significant interaction between FS and Clo was found in mice tested at the 0.03 mg/kg (ip) Clo dose (Fig 3A; n=27; P>0.05). Post-hoc testing showed that FS increased time spent in the Coc compartment after treatment with V (#P<0.05) but not 0.03 mg/kg Clo. Further, time spent in the Coc compartment was significantly reduced following 0.03 mg/kg Clo compared to V (@P<0.05). The effect of 0.3 mg/kg (ip) Clo (n=9) on FS-induced reinstatement is shown in Fig 3B. A significant main effect of FS (*P<0.05) but no FS x Clo interaction was found at this dose.

Cocaine

The effects of clonidine (0.03 or 0.3 mg/kg, ip) on cocaine-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 4. Neither clonidine dose blocked cocaine-induced reinstatement. The effect of 0.03 mg/kg clonidine was tested in 25 mice (Fig 4A). Two-way cocaine x 0.03 mg/kg clonidine treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of cocaine priming (F1,24=22.807; P<0.001) on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, no significant main effect of clonidine treatment condition or interaction between clonidine treatment and cocaine-induced reinstatement was found. Thirteen mice were tested for the effect of a 10-fold higher clonidine dose (0.3 mg/kg, ip) on cocaine-induced reinstatement (Fig 4B). Not only did this higher clonidine dose fail to block cocaine-induced reinstatement, but it tended to augment reinstatement in response to cocaine. Similar to the lower clonidine dose, two-way cocaine x clonidine treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of cocaine priming (F1,12=9.319; P=0.01) on time spent in the cocaine compartment with no main effect of clonidine treatment condition and no interaction between clonidine treatment and cocaine-induced reinstatement.

Figure 4.

The alpha-2 AR agonist clonidine does not block cocaine-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after administration of cocaine (C; 15 mg/kg, ip) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or 0.03 mg/kg clonidine (ip) (Clo; n=25; Fig 4A) or with V or 0.3 mg/kg Clo (n=13; Fig 4B). In both cases, significant main effects of C (*P<0.05) but no significant C x Clo interactions were found.

Yohimbine

The effects of clonidine on yohimbine-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 5. Since yohimbine likely reinstates extinguished cocaine seeking via blockade of alpha-2 ARs, we anticipated that yohimbine-induced reinstatement would be attenuated by clonidine. Surprisingly, neither the low (i.e., 0.03 mg/kg) nor the high (i.e., 0.3 mg/kg) clonidine dose blocked yohimbine-induced reinstatement. Forty total mice were tested for the effects of 0.03 mg/kg clonidine on yohimbine-induced reinstatement (Fig. 5A). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of yohimbine on time spent in the cocaine compartment (F1,39=13.306) but failed to show a significant main effect of for 0.03 mg/kg clonidine treatment condition or a significant interaction between clonidine treatment and yohimbine-induced reinstatement. We reasoned that our inability to fully block yohimbine-induced reinstatement with 0.03 mg/kg clonidine may have been dose-related due to competition for the same receptor site. However when we tested mice with 0.3 mg/kg clonidine (n=38), there was little evidence for a reduction of yohimbine-induced reinstatement at this dose (Fig 5B). Two-way repeated measures yohimbine-induced reinstatement × 0.3 mg/kg clonidine treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of yohimbine (F1,37=8.507; P<0.01) but no overall effect of clonidine pretreatment and no yohimbine reinstatement x clonidine pretreatment interaction.

Figure 5.

The alpha-2 AR agonist clonidine does not block yohimbine-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after administration of yohimbine (Y; 2 mg/kg, ip) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or 0.03 mg/kg clonidine (ip) (Clo; n=40; Fig 5A) or with V or 0.3 mg/kg Clo (n=38; Fig 5B). In both cases, significant main effects of Y (*P<0.05) but no significant Y x Clo interactions were found.

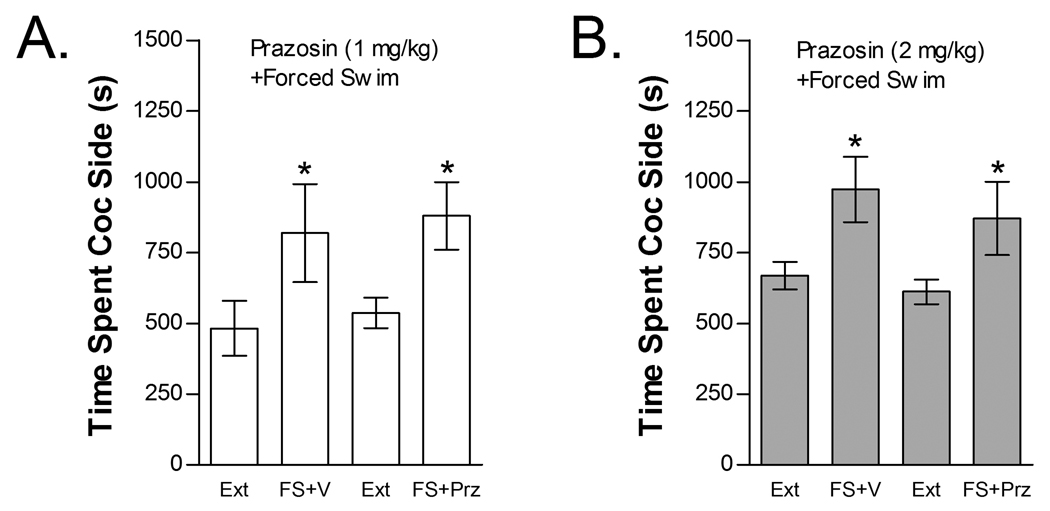

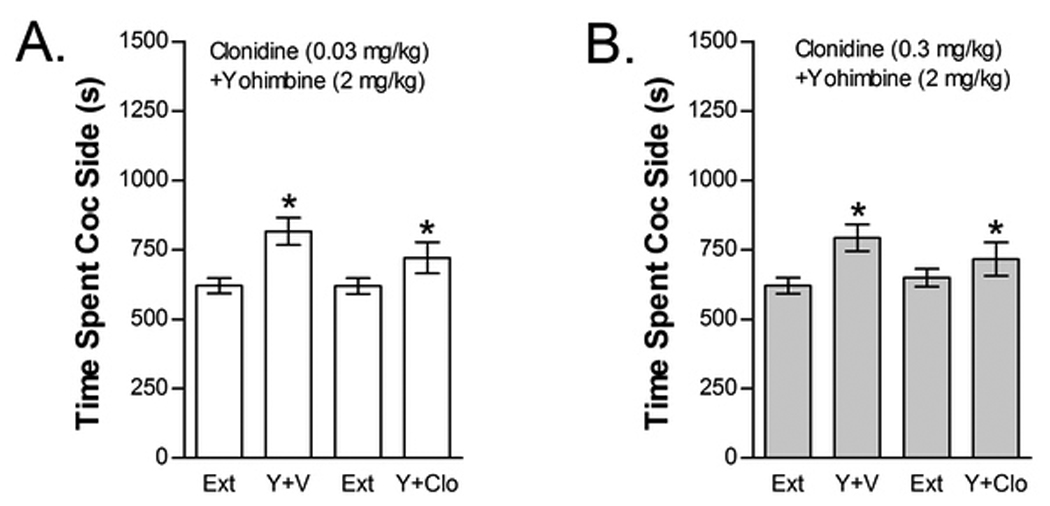

Effects of prazosin on reinstatement

To examine the role of alpha-1 ARs in reinstatement by various stimuli, mice were pretreated with the alpha-1 AR antagonist prazosin (2 and 4 mg/kg) prior to FS or administration of cocaine or yohimbine. In all cases, prazosin failed to alter reinstatement.

Forced Swim

The effects of prazosin (1 or 2 mg/kg, ip) on FS-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 6. Neither prazosin dose blocked reinstatement following FS. The effect of 1 mg/kg prazosin was tested in five mice (Fig 6A). Two-way repeated measures FS× 1 mg/kg prazosin treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of FS (F1,4=12.251; P<0.05) on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, no significant main effect of prazosin treatment condition or interaction between prazosin and FS-induced reinstatement was found. Fourteen mice were tested for the effect of 2 mg/kg prazosin on FS-induced reinstatement (Fig 6B). Similar to the lower prazosin dose, two-way repeated measures FS× 2 mg/kg prazosin treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of FS (F1,13=5.368; P<0.05) on time spent in the cocaine compartment with no main effect of prazosin treatment condition and no interaction between prazosin and FS.

Figure 6.

The selective alpha-1 AR antagonist prazosin does not block stress-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after forced swim (FS) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or 1 mg/kg (ip) prazosin (Prz; n=5; Fig 6A) or pretreatment with V or 2 mg/kg (ip) Prz (n=14; Fig 6B). In both cases, significant main effects of FS (*P<0.05) but no FS x Prz interactions were found.

Cocaine

The effects of prazosin on cocaine-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 7. Neither prazosin dose blocked cocaine-induced reinstatement. The effect of 1 mg/kg prazosin was tested in 11 mice (Fig 7A). Two-way cocaine× 1 mg/kg prazosin treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of cocaine (F1,10=9.000; P<0.05) on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, no significant main effect of prazosin treatment condition or interaction between prazosin and cocaine-induced reinstatement was found. Thirteen mice were tested for the effect of 2 mg/kg prazosin on cocaine-induced reinstatement (Fig 7B). Similar to the lower prazosin dose, two-way cocaine× 2 mg/kg prazosin treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of cocaine (F1,12=17.241; P<0.01) on time spent in the cocaine compartment with no main effect of prazosin treatment condition and no interaction between prazosin treatment and cocaine-induced reinstatement.

Figure 7.

The selective alpha-1 AR antagonist prazosin does not block cocaine-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after administration of cocaine (C; 15 mg/kg, ip) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or 1 mg/kg (ip) prazosin (Prz; n=11; Fig 7A) or pretreatment with V or 2 mg/kg (ip) Prz (n=14; Fig 7B). In both cases, significant main effects of C (*P<0.05) but no C x Prz interactions were found.

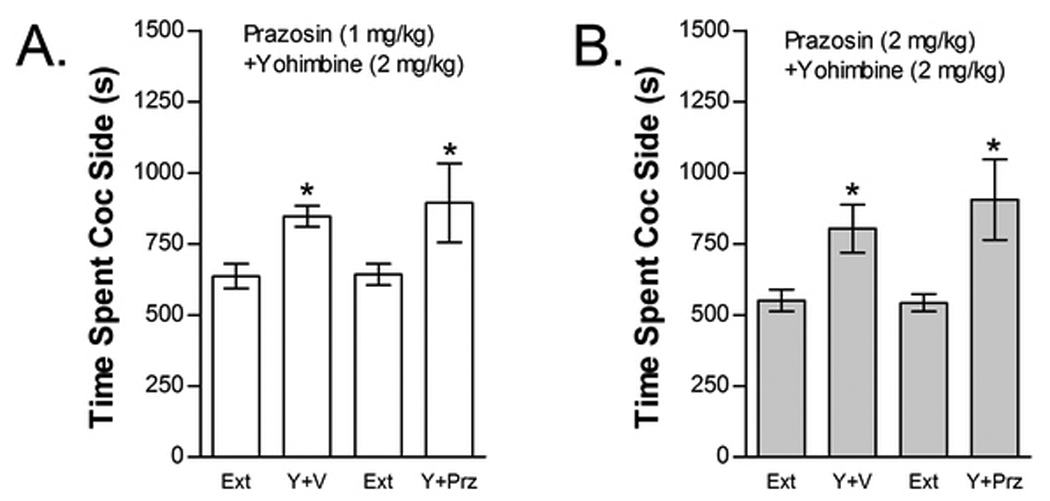

Yohimbine

The effects of prazosin on cocaine-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 8. Neither prazosin dose blocked yohimbine-induced reinstatement. The effect of 1 mg/kg prazosin was tested in six mice (Fig 8A). Two-way repeated measures yohimbine× 1 mg/kg prazosin treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of yohimbine (F1,5=13.114; P<0.05) on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, no significant main effect of prazosin treatment condition or interaction between prazosin and yohimbine-induced reinstatement was found. Fifteen mice were tested for the effect of 2 mg/kg prazosin on yohimbine-induced reinstatement (Fig 8B). Similar to the lower prazosin dose, two-way repeated measures yohimbine× 2 mg/kg prazosin treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of yohimbine (F1,14=11.558; P<0.01) on time spent in the cocaine compartment with no main effect of prazosin treatment condition and no interaction between prazosin and yohimbine.

Figure 8.

The selective alpha-1 AR antagonist prazosin does not block yohimbine-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after administration of yohimbine (Y; 2 mg/kg, ip) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or 1 mg/kg (ip) prazosin (Prz; n=6; Fig 8A) or pretreatment with V or 2 mg/kg (ip) Prz (n=15; Fig 8B). In both cases, significant main effects of Y (*P<0.05) but no Y x Prz interactions were found.

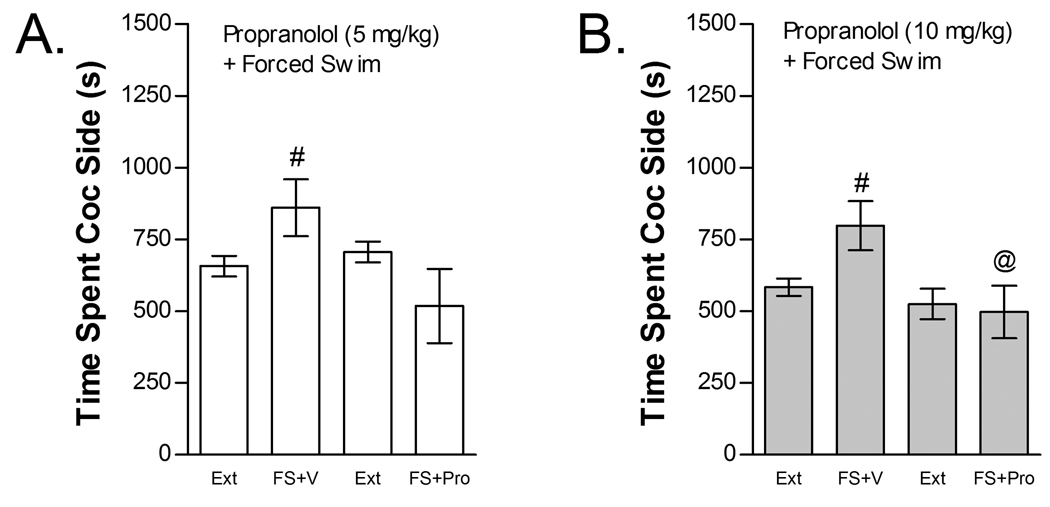

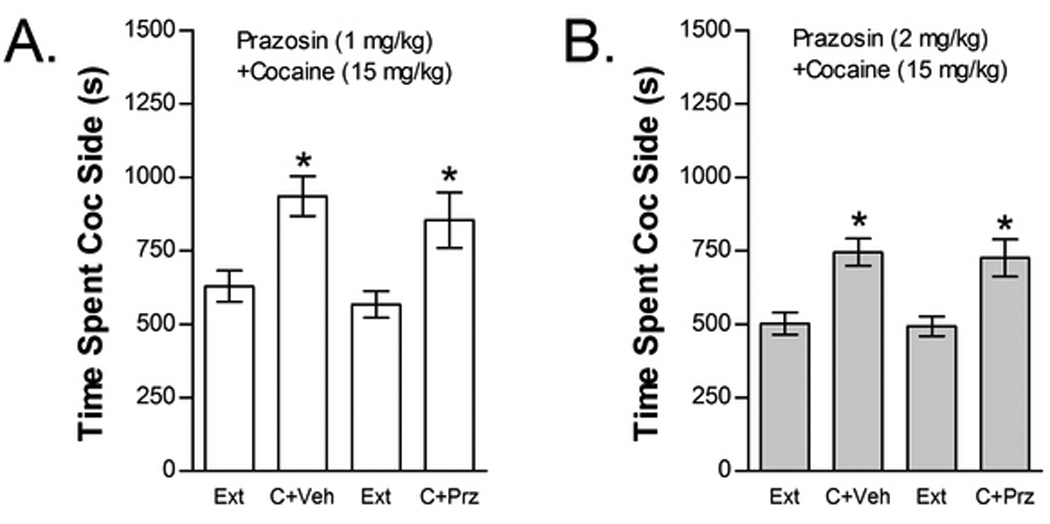

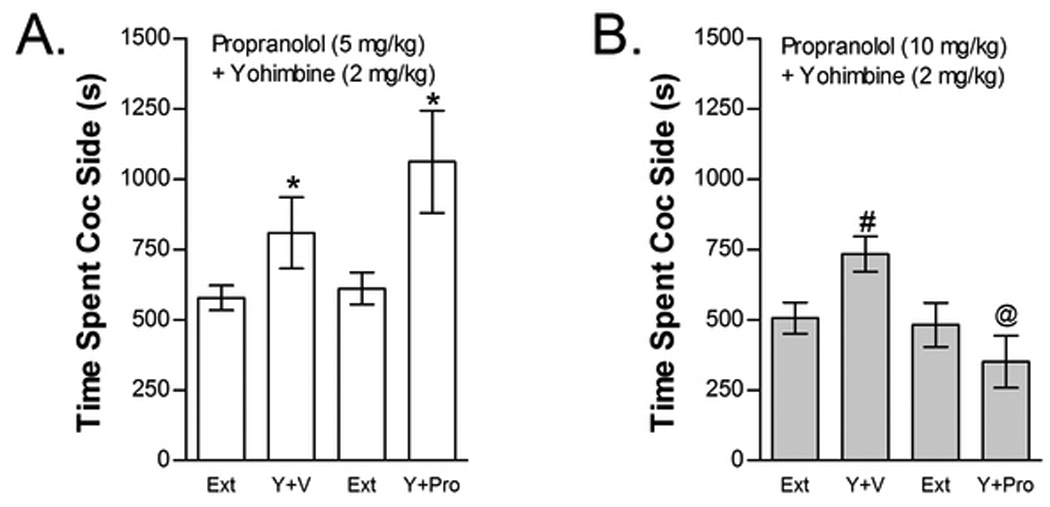

Effects of propranolol on reinstatement

To examine the role of beta ARs in reinstatement by various stimuli, mice were pretreated with the non-selective beta AR antagonist, propranolol, prior to FS or administration of cocaine or yohimbine. Propranolol blocked reinstatement by FS and yohimbine, but not cocaine. Further, FS-induced reinstatement was more sensitive to blockade by propranolol than yohimbine-induced reinstatement.

Forced Swim

The effects of propranolol (5 or 10 mg/kg, ip) on FS-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 9. Both propranolol doses blocked FS-induced reinstatement. The effect of 5 mg/kg propranolol was tested in seven mice (Fig 9B). Two-way repeated measures FS× 5 mg/kg propranolol treatment condition ANOVA failed to show a significant overall effect of propranolol or FS on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, a significant propranolol x FS interaction was observed (F1,6=8.598; P<0.05). Post-hoc examination of reinstatement in each group revealed that FS significantly reinstated place preference in vehicle- but not 5 mg/kg propranolol-treated mice (t6=4.32; P<0.05). Sixteen mice were tested for the effects of 10 mg/kg propranolol on FS-induced reinstatement (Fig 9B). Two-way repeated measures FS× 10 mg/kg propranolol treatment ANOVA showed a significant main effect of propranolol (F1,15=7.018; P<0.05) but not FS and a significant interaction between 10 mg/kg propranolol treatment and FS (F1,15 =5.116; P<0.05). Post-hoc examination of reinstatement in each group revealed that FS significantly reinstated place preference in vehicle-treated but not 10 mg/kg propranolol-treated mice (t15=2.729; P<0.05) and that time-spent in the cocaine compartment was significantly reduced by propranolol following FS (t30=2.411; P<0.05) but not under basal conditions.

Figure 9.

The non-selective beta AR antagonist propranolol blocks stress-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after forced swim (FS) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or propranolol (Pro). Significant interactions between FS and Pro were found in mice tested at the 5 mg/kg (ip; Fig 9A; n=7) and 10 mg/kg (ip; Fig 9B; n=16) Pro doses (P<0.05). In each case, post-hoc testing showed that FS increased time spent in the Coc compartment after treatment with V (#P<0.05) but not Pro. Further, time spent in the Coc compartment was significantly reduced following Pro compared to V at the 10 mg/kg, but not 5 mg/kg, Pro dose (@P<0.05).

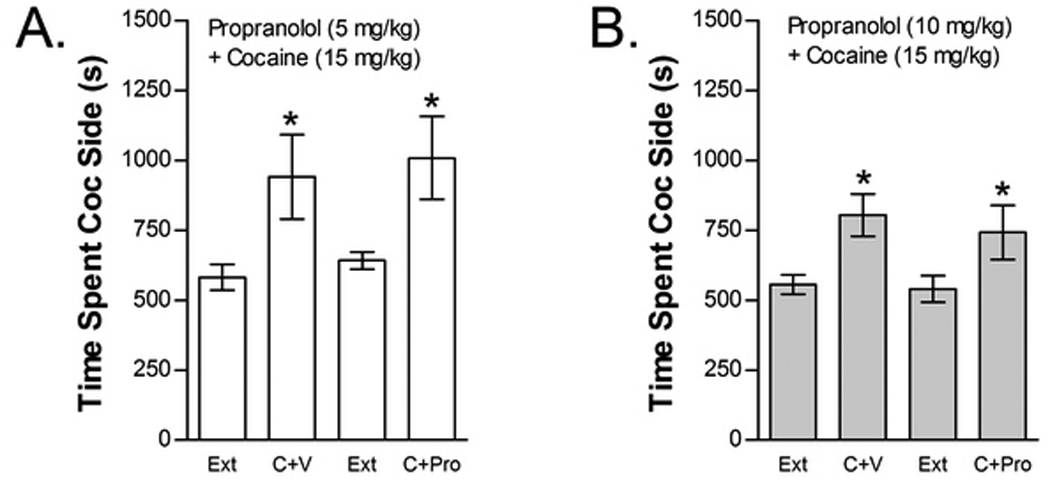

Cocaine

The effects of propranolol (5 or 10 mg/kg, ip) on cocaine-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 10. Neither propranolol dose blocked cocaine-induced reinstatement. The effect of 5 mg/kg propranolol was tested in nine mice (Fig 10A). Two-way cocaine× 5 mg/kg propranolol treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of cocaine (F1,8=9.731; P<0.05) on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, no significant main effect of propranolol treatment condition or interaction between propranolol and cocaine-induced reinstatement was found. Eleven mice were tested for the effect of 10 mg/kg propranolol on cocaine-induced reinstatement (Fig 10B). Similar to the lower propranolol dose, two-way cocaine× 10 mg/kg propranolol treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of cocaine (F1,10=13.624; P<0.01) on time spent in the cocaine compartment with no main effect of propranolol treatment condition and no interaction between propranolol treatment and cocaine-induced reinstatement.

Figure 10.

The non-selective beta AR antagonist propranolol does not block cocaine-induced reinstatement. Data represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after administration of cocaine (C; 15 mg/kg, ip) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or 5 mg/kg (ip) propranolol (Pro; n=9; Fig 10A) or pretreatment with V or 10 mg/kg (ip) Pro (n=11; Fig 10B). In both cases significant main effects of C (*P<0.05) but no C × Pro interactions were found.

Yohimbine

The effects of propranolol (5 or 10 mg/kg, ip) on yohimbine-induced reinstatement are shown in Figure 11. Propranolol blocked yohimbine-induced reinstatement at the 10 mg/kg, but not 5 mg/kg, dose. The effect of 5 mg/kg propranolol was tested in eight mice (Fig 11A). Two-way repeated measures yohimbine× 5 mg/kg propranolol treatment condition ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of yohimbine (F1,7=7.865; P<0.05) on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, no significant main effect of 5 mg/kg propranolol treatment condition or interaction between 5 mg/kg propranolol and yohimbine-induced reinstatement was found. The effect of 10 mg/kg propranolol on yohimbine-induced reinstatement was tested in ten mice (Fig 11B). In contrast to the lower propranolol dose, 10 mg/kg propranolol prevented reinstatement following yohimbine administration. Two-way repeated measures yohimbine reinstatement× 10 mg/kg propranolol treatment condition ANOVA failed to show significant main effects of yohimbine or propranolol (P=0.06) However, a significant interaction between 10 mg/kg propranolol treatment x yohimbine-induced reinstatement was found (F1,9=10.563; P=0.01). Post-hoc analyses showed that yohimbine significantly increased time spent in the cocaine compartment in vehicle pretreated (paired t-test; 2-tailed t9=2.334; P<0.05) but not propranolol pretreated mice and that time spent in the cocaine compartment following yohimbine was significantly reduced in propranolol-pretreated mice compared to vehicle controls (t9=2.728; P<0.05).

Figure 11.

The non-selective beta AR antagonist propranolol dose-dependently blocks yohimbine-induced reinstatement. Data in Fig 11A represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after administration of yohimbine (Y; 2 mg/kg, ip) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or 5 mg/kg (ip) propranolol (Pro; n=8). A significant main effect of Y (*P<0.05) but no Y x Pro interaction was found at this dose. The effect of 10 mg/kg (ip) Pro (n=10) on Y-induced reinstatement is shown in Fig 11B. A significant interaction between Y and Pro was found at this dose (P<0.05). Post-hoc testing showed that Y increased time spent in the Coc compartment after treatment with V (#P<0.05) but not ICI. Further, time spent in the Coc compartment was significantly reduced following 10 mg/kg Pro compared to V (@P<0.05).

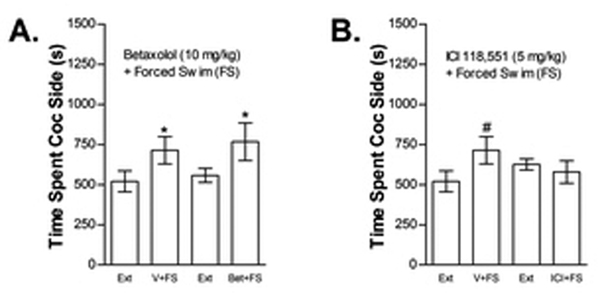

Effects of betaxolol and ICI 118,551 on FS-induced reinstatement

Since FS-induced reinstatement appeared to involve beta but not alpha-1 ARs, mice were tested with the beta-1 AR selective receptor antagonist, betaxolol (10 mg/kg, ip), or the beta-2 AR selective antagonist, ICI-118551 (5 mg/kg, ip) in order to determine the role of beta receptor subtypes in reinstatement by FS (Fig 12). ICI-118551 (Fig 12B) but not betaxolol (Fig 12A) blocked FS-induced reinstatement. The effect of betaxolol was tested in 11 mice. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of FS on time spent in the cocaine compartment (F1,10=9.762; P<0.05) but no effect of betaxolol or FS x betaxolol reinstatement. Eleven mice were tested for the effect of ICI-118551 on FS-induced reinstatement. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed no main effects of ICI-118551 or FS on time spent in the cocaine compartment. However, a significant ICI-118551 x FS interaction was observed (F1,10=9.364; P<0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that FS produced significant reinstatement in vehicle, but not ICI-118551, treated mice (t10=2.874; P<0.05).

Figure 12.

The beta-2 AR selective antagonist ICI-118551 but not the beta-1 AR selective antagonist betaxolol blocks stress-induced reinstatement. Data in Fig 12A represent the time spent in the cocaine (Coc) compartment (sec ± SE) during the final extinction session prior to reinstatement testing (Ext) and during reinstatement testing after forced swim (FS) following pretreatment with vehicle (V) or betaxolol (Bet; 10 mg/kg, ip; n=11). A significant main effect of FS (*P<0.05) but no FS x Bet interaction was found. The effect of ICI-118551 (ICI; 1 mg/kg, ip; n=11) on FS-induced reinstatement is shown in Fig 12B. A significant interaction between FS and ICI was found (P<0.05). Post-hoc testing showed that FS increased time spent in the cocaine compartment after treatment with V (#P<0.05) but not ICI.

DISCUSSION

Drug re-exposure and stress are commonly cited as precipitating factors for relapse in recovering cocaine addicts. Although both stimuli can trigger drug use, they do not necessarily do so through activation of completely overlapping neurobiological pathways. The present study poses the noradrenergic system as a likely mediator of relapse in response to stressors but not cocaine. First, activation of central noradrenergic systems through disinhibition of noradrenergic signaling by administration of the alpha-2 AR antagonist yohimbine or the more selective alpha-2A AR antagonist BRL 44408 (Dwyer et al 2010) is sufficient to induce reinstatement. Secondly, suppression of noradrenergic neurotransmission by administration of the alpha-2 AR agonist clonidine suppresses reinstatement by FS but not cocaine. Third, reinstatement by FS and yohimbine, but not cocaine, is blocked by the non-selective beta AR antagonist propranolol but not by the alpha-1 AR antagonist, prazosin. In the case of FS, reinstatement is prevented by the selective beta-2 AR antagonist ICI-118551, but not the selective beta-1 AR antagonist, betaxolol. Altogether, these findings suggest that elevated norepinephrine (NE) during periods of stress, but not following cocaine re-exposure, likely induces drug seeking through activation of beta-2 ARs as measured in this mouse model of relapse.

The apparent role for NE in stressor-induced relapse is also supported by previous studies. Icv NE administration reinstates cocaine seeking following SA (Brown, et al 2009), as does disinhibition of noradrenergic signaling through alpha-2 adrenergic autoreceptor blockade (Lee, et al 2004; Feltenstein and See, 2006; Fletcher, et al 2008; Brown, et al 2009) and, in some cases, blockade of NE reuptake (Platt, et al 2007 but see Schmidt and Pierce, 2006). Conversely, suppression of stressor-induced NE release through administration of alpha-2 AR agonists such as clonidine (Tjurmina, et al 1999) attenuates stress-induced drug seeking following SA of cocaine (Erb, et al 2000), heroin (Shaham, et al 2000), alcohol (Le, et al 2005; Dzung Lê, et al 2009), or a heroin-cocaine mixture (Highfield, et al 2001) in rats, stress-induced reinstatement of morphine-induced place preference in rats (Wang, et al 2001) and drug craving induced by stress imagery in heroin-dependent human subjects (Sinha, et al 2007).

Although stress-induced reinstatement was blocked using propranolol and clonidine, these pretreatments failed to alter reinstatement in response to cocaine, even though clonidine has been shown to prevent cocaine-induced increases in brain extracellular NE levels (Florin, et al 1994). Considering that cocaine, like other NET blockers that have been shown to induce reinstatement (Platt, et al 2007), markedly elevates central NE levels (Reith, et al 1997; Li, et al 1996), and that elevation of central NE is sufficient to induce reinstatement (Brown, et al 2009), our findings suggest that cocaine-responsive processes activated either concurrently with or downstream from noradrenergic systems are sufficient for relapse in the absence of a NE response. This assertion is consistent with a number of reports suggesting that many neurobiological systems underlying stress-induced cocaine seeking (e.g., CRF and kappa opioid) do not completely overlap with those underlying reinstatement in response to cocaine delivery (Erb, et al 1998; Shaham, et al 1998; Redila and Chavkin, 2008) and is supported by studies demonstrating that suppression of noradrenergic neurotransmission through alpha-2 AR activation (Erb, et al 2000) or antagonism of central beta ARs (Leri, et al 2002) blocks stress- but not cocaine-induced reinstatement in rats as well as by findings that mixed alpha and beta adrenergic receptor antagonist drugs do not attenuate the subjective responses to smoked cocaine, despite reducing peripheral adrenergic responses (Sofuoglu, et al 2000a; 2000b). However, it should be noted that other studies have indicated that noradrenergic neurotransmission may be involved in cocaine-induced reinstatement in monkeys (Platt, et al 2007) and rats (Zhang and Kosten, 2005).

Our finding that propranolol blocks stressor-induced reinstatement is supported by those of Leri, et al (2002) who found that administration of a combination of beta-1 and beta-2 AR antagonists directly into brain regions implicated in stressor-induced cocaine seeking blocks footshock-induced reinstatement following self-administration in rats. Propranolol has also been found to block reinstatement resulting from NET blockade following self-administration in monkeys (Platt, et al 2007). Further, since beta AR are Gs G-protein coupled receptors, the findings are consistent with a report that forced swim- but not cocaine-induced reinstatement of conditioned place preference is dependent on cAMP and CREB activation in mice (Kreibich and Blendy, 2004). Interestingly, beta blockers have been reported to attenuate anxiety-like effects resulting from cocaine delivery (Schank, et al 2008; elevated plus maze) or cocaine withdrawal (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993; defensive burying). Thus, to the extent that these anxiogenic effects contribute to drug craving and relapse during withdrawal and/or continued cocaine use, our findings provide further evidence of potential utility of beta blockers for the management of cocaine addiction. Despite these findings, clinical trials examining the ability of propranolol to promote drug abstinence in cocaine-dependent individuals have found only modest improvement (Kampman, et al 2001; 2006) potentially due to the inability of propranolol to attenuate cocaine-induced craving and rewarding effects. Consistent with our own findings, it has been reported that propranolol fails to decrease cocaine-induced reinstatement in rats (Leri, et al 2002) and monkeys (Platt, et al 2007) and that drugs with beta AR antagonist properties fail to alter cocaine’s subjective effects (Sofuoglu, et al 2000a; 2000b). In fact, it has been reported that propranolol can actually augment cocaine’s locomotor (Harris, et al 1996 but see Vanderschuren, et al 2003), discriminative stimulus (Kleven and Koek, 1997; but see Spealman, 1995), and reinforcing effects (Harris, et al 1996). It may be that, because of the selective attenuation of stress-induced cocaine seeking, targeting beta receptors may be more useful as an adjunct approach and/or only in subpopulations of cocaine-dependent individuals whose use is stress driven. In support, Kampman, et al (2001; 2006) found that propranolol significantly increased abstinence time only in cocaine-dependent individuals experiencing pronounced withdrawal symptoms, which for cocaine dependence include intense anxiety (Gawin and Kleber, 1986).

In the present study, stressor-induced reinstatement appeared to involve beta-2 AR, presumably within the CNS, but not beta-1 AR. FS-induced reinstatement was blocked by the selective beta-2 AR antagonist ICI-118551 but not the beta-1 AR antagonist betaxolol. This finding was somewhat surprising, considering that it has been previously reported that betaxolol blocked anxiety-like behavior during withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2007). The role of beta-2 AR in stress- and anxiety-related processes is unclear. However, beta-2 AR are found throughout the rat brain, including in the BNST (Rainbow, et al 1985) and the amygdala (Tiong and Richardson, 1990), sites where non-selective antagonism of beta AR has been shown to attenuate stressor-induced cocaine seeking (Leri, et al 2002) and where beta-2 AR have been implicated in affective, but not sensory or somatic, elements of pain (Deyama, et al 2008) or opiate withdrawal (Watanabe, et al 2003). Confirmation that central but not peripheral beta-2 AR activation is required for stress-induced reinstatement will require further investigation.

In contrast to propranolol, the alpha-1 AR antagonist prazosin (1 or 2 mg/kg) failed to alter reinstatement by any of the stimuli tested. The finding that prazosin did not alter cocaine-induced reinstatement was somewhat surprising considering that prazosin has been reported to attenuate cocaine-induced reinstatement following self-administration in rats (Zhang and Kosten, 2005) but not monkeys (Platt, et al 2007). This disparity in prazosin effects on cocaine-evoked reinstatement across studies could be attributable to a number of factors, including species, general approach/experimental parameters and dose. A role for alpha-1 ARs in a number of cocaine effects has been identified, including cocaine’s reinforcing (Drouin, et al 2002; Wee, et al 2008 but see Woolverton, 1987), sensitizing (Jiménez-Rivera, et al 2006; Zhang and Kosten, 2007), locomotor stimulating (Drouin, et al 2002; Snoddy and Tessel, 1985 but see Vanderschuren, et al 2003), and discriminative stimulus (Spealman, 1995) effects.

Our finding that yohimbine administration reinstates extinguished place preference in mice is consistent with previous reports that yohimbine reinstates extinguished cocaine seeking following SA in rats (Feltenstein and See, 2006; Fletcher, et al 2008; Brown, et al 2009) and monkeys (Lee, et al 2004) and impairs the extinction of cocaine-induce conditioned place preference in mice (Davis, et al 2008). Since we were able to block yohimbine-induced reinstatement with propranolol, we presumed that yohimbine’s effects on cocaine seeking were attributable to disinhibition of noradrenergic activity resulting from antagonism of alpha-2 adrenergic autoreceptors. Consistent with this, it has been reported that the highly selective alpha-2 adrenergic receptor antagonist RS-79948 can induce reinstatement in monkeys (Lee, et al 2004) and that RS-79948- and yohimbine-induced reinstatement are blocked by the alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist, clonidine (Lee, et al 2004). A similar clonidine-inhibited beta AR dependent mechanism has been reported to be involved in the reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking by the selective NET inhibitor, nisoxetine in squirrel monkeys (Platt, et al 2007). Surprisingly however, in the present study, clonidine failed to block yohimbine-induced reinstatement. These findings are consistent a recent report that clonidine fails to prevent yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking following SA in rats (Brown, et al 2009).

It is unclear why clonidine is ineffective in blocking yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. However, there are two possibilities. First, yohimbine could be inducing reinstatement through a non alpha-2 AR mechanism. In support, Davis, et al (2008) reported that the impairment of extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference and suppression of glutamate-induced electrophysiological responses in brain slices containing the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis by yohimbine were unaltered in alpha-2A adrenergic receptor deficient mice and were not mimicked by the more selective alpha-2A AR antagonist, atipamezole. Yohimbine has been reported to function as an agonist at 5-HT1A receptors (Winter and Rabin, 1992; Millan, et al 2000). This 5-HT1A receptor agonist effect may be relevant to drug seeking, as yohimbine-induced reinstatement of extinguished alcohol seeking in rats is attenuated by the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY 100635, as well as clonidine, but is minimally reduced by lesions of ascending noradrenergic systems (Dzung Lê, et al 2009). To further examine the role for alpha-2 AR antagonism in reinstatement, we also tested mice with the selective alpha-2A antagonist BRL 44408, a compound that has a 50-fold higher affinity for alpha-2A AR relative to 5-HT-1A receptors (Dwyer, et al 2010). Like yohimbine, this more selective alpha-2A AR antagonist also produced robust reinstatement, suggesting that alpha-2 AR antagonism alone is likely sufficient for reinstatement. Notably, if indeed yohimbine is working through a mechanism that is independent of alpha-2 AR, our data suggest that this mechanism still involves beta AR.

Secondly, clonidine itself is somewhat non-selective. Lower clonidine doses likely primarily target pre-synaptic alpha-2 ARs, thereby competitively reversing yohimbine effects and generally suppressing noradrenergic neurotransmission through alpha-2 AR mediated auto-inhibitory actions. Accordingly, at the lower (i.e., 0.03 mg/kg) dose, clonidine prevented reinstatement by FS. In addition to attenuating NE release, higher clonidine doses also activate lower affinity post-synaptic alpha-2 ARs and/or bind to imidazoline I1 receptor sites (Bricca, et al 1989; Eglen, et al 1998) thus mimicking components of the noradrenergic response despite indirectly reducing activation of alpha-1 and beta AR or producing non-noradrenergic effects. Based on our finding that the higher (i.e., 0.3 mg/kg) clonidine dose not only failed to attenuate yohimbine and FS-induced reinstatement but induced reinstatement on its own, we hypothesize that, like beta AR, these high-dose targets may contribute to reinstatement during stress. This finding is consistent with another report that high doses of clonidine can induce conditioned place preference in rats (Cervo, et al 1993). Future studies using putative imidazoline receptor ligands as well as other alpha-2 AR agonists with relatively low affinity for imidazoline receptors (e.g., guanabenz) are needed to determine the relative contribution of these receptor populations to reinstatement. Overall, this dose-dependent regulation of differential receptor populations with varying effects on drug seeking, along with the tendency of yohimbine to interact with multiple receptor targets, likely contributed to the observed variation in clonidine’s ability to block yohimbine-induced reinstatement in this study and others.

NE-dependent stress-induced reinstatement appears to involve projections from the lateral tegmental region of the brainstem to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and/or the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) via the ventral noradrenergic bundle and activation beta adrenergic receptors. In rats, stress- but not drug-induced reinstatement is attenuated by administration of clonidine into the lateral tegmentum, but not the LC (Shaham, et al 2000; heroin) or into the BNST (Wang, et al 2001; cocaine) or by delivery of a combination of beta 1 and beta 2 adrenergic receptor antagonists into the BNST or CeA (Leri, et al 2002; cocaine). It has been postulated that NE released into these regions regulates the release of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) which in turn can indirectly (via actions in the BNST; Erb, et al 2001) or directly (via actions in the ventral tegmental area; Wang, et al 2005) activate mesocorticolimbic activity, thus producing drug-seeking behavior. The apparent lack of involvement of CRF (Shaham, et al 1998; Erb, et al 1998) and NE (Erb, et al 2000, Leri, et al 2002, and present findings; but see Platt, et al 2007, Zhang and Kosten, 2005) in cocaine-induced reinstatement suggests that despite convergence within the mesocorticolimbic system, the neurobiological pathways underlying drug and stress induced relapse are largely distinct.

Beta AR, specifically beta-2 AR, have also been implicated in the post-retrieval reconsolidation of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Systemic propranolol (Bernardi, et al 2006; Fricks-Gleason, et al 2008) and intrabasolateral amygdalar ICI-118551 (Bernardi, et al 2009) injections interfere specifically with the reconsolidation of conditioned place preference following retrieval without enhancing extinction learning. Since, in our study, mice did not receive propranolol or ICI-118551 until after place preference had already been extinguished and since drug administration occurred immediately prior to exposure of the reinstating stimuli, it is unlikely that effects on reconsolidation contributed to the observed attenuation of reinstatement. Nonetheless, the potential ability of beta-2 AR antagonists to attenuate stress-evoked relapse and interfere with reconsolidation of drug-associated memories, establishes beta-2 ARs as a target of interest for the treatment of addiction.

In summary, these findings further suggest that central noradrenergic systems contribute to drug-seeking behavior during times of stress. Considering that repeated cocaine exposure is associated with progressive changes in brain noradrenergic systems (Belej, et al 1996; Macey, et al 2003; Baumann, et al 2004; Beveridge, et al 2005; Horne, et al 2008; Lanteri, et al 2008) and that early abstinence from cocaine in dependent individuals is associated with an exaggerated noradrenergic response (McDougle, et al 1994), targeting noradrenergic neurotransmission, particularly beta-2 AR, may be particularly beneficial for the management of relapse in cocaine-dependent individuals whose drug use is stress-related.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant numbers DA15758 and DA025617. We thank Ms. Amanda Clifford for her work in helping to establish the mouse conditioned place preference protocol.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest with the content of this paper.

The authors have received financial support or compensation as follows:

John R. Mantsch is a Founder and past Director of as well as a consultant for and stockholder in Promentis Pharmaceuticals and has served as a consultant for WIL Research, Inc. (Ashland, OH). He has received research support from the NIH and the State of Wisconsin Biotechnology Alliance. He is a full-time employee of Marquette University.

David A. Baker is a Founder and Director of as well as a consultant for and stockholder in Promentis Pharmaceuticals. He has received research support from the NIH, the State of Wisconsin Biotechnology Alliance, and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Addiction. He is a full-time employee of Marquette University.

Chad E. Beyer was a fulltime employee of Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (Princeton, NJ) at the time that these studies were completed.

Holly Caretta, Andy Weyer and Oliver Vranjkovic were employees of Marquette University at the time that these studies were completed.

References

- Abercrombie ED, Keller RW, Jr, Zigmond MJ. Characterization of hippocampal norepinephrine release as measured by microdialysis perfusion: pharmacological and behavioral studies. Neuroscience. 1988;27:897–904. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Milchanowski AB, Rothman RB. Evidence for alterations in alpha2-adrenergic receptor sensitivity in rats exposed to repeated cocaine administration. Neuroscience. 2004;125:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belej T, Manji D, Sioutis S, Barros HM, Nobrega JN. Changes in serotonin and norepinephrine uptake sites after chronic cocaine: pre- vs. post-withdrawal effects. Brain Res. 1996;736:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi RE, Lattal KM, Berger SP. Postretrieval propranolol disrupts a cocaine conditioned place preference. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1443–1447. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000233098.20655.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi RE, Ryabinin AE, Berger SP, Lattal KM. Post-retrieval disruption of a cocaine conditioned place preference by systemic and intrabasolateral amygdala beta2- and alpha1-adrenergic antagonists. Learn Mem. 2009;16:777–789. doi: 10.1101/lm.1648509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge TJ, Smith HR, Nader MA, Porrino LJ. Effects of chronic cocaine self-administration on norepinephrine transporters in the nonhuman primate brain. Psychopharmacology. 2005;180:781–788. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricca G, Dontenwill M, Molines A, Feldman J, Belcourt A, Bousquet P. The imidazoline preferring receptor: binding studies in bovine, rat and human brainstem. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;162:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ZJ, Tribe E, D’souza NA, Erb S. Interaction between noradrenaline and corticotrophin-releasing factor in the reinstatement of cocaine seeking in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2009;203:121–130. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L, Rossi C, Samanin R. Clonidine-induced place preference is mediated by alpha 2-adrenoceptors outside the locus coeruleus. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;238:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90848-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AR, Shields AD, Brigman JL, Norcross M, McElligott ZA, Holmes A, Winder DG. Yohimbine impairs extinction of cocaine-conditioned place preference in an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor independent process. Learn Mem. 2008;26:667–676. doi: 10.1101/lm.1079308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyama S, Katayama T, Ohno A, Nakagawa T, Kaneko S, Yamaguchi T, Yoshioka M, Minami M. Activation of the beta-adrenoceptor-protein kinase A signaling pathway within the ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis mediates the negative affective component of pain in rats. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7728–7736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1480-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin C, Darracq L, Trovero F, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Cotecchia S, Tassin JP. Alpha1b-adrenergic receptors control locomotor and rewarding effects of psychostimulants and opiates. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2873–2884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02873.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer JM, Platt BJ, Sukoff Rizzo SJ, Pulicicchio CM, Wantuch C, Zhang MY, Cummons T, Leventhal L, Bender CN, Zhang J, Kowal D, Lu S, Rajarao SJ, Smith DL, Shilling AD, Wang J, Butera J, Resnick L, Rosenzweig-Lipson S, Schechter LE, Beyer CE. Preclinical characterization of BRL 44408: antidepressant- and analgesic-like activity through selective alpha2A-adrenoceptor antagonism. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;5:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709991088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzung Lê A, Funk D, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Fletcher PJ. The role of noradrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine in yohimbine-induced increases in alcohol-seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:477–488. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen RM, Hudson AL, Kendall DA, Nutt DJ, Morgan NG, Wilson VG, Dillon MP. ‘Seeing through a glass darkly’: casting light on imidazoline ‘I’ sites. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:381–390. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Shaham Y, Stewart J. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and corticosterone in stress- and cocaine-induced relapse to cocaine seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5529–5536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05529.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Hitchcott PK, Rajabi H, Mueller D, Shaham Y, Stewart J. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists block stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:138–150. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00158-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Salmaso N, Rodaros D, Stewart J. A role for the CRF-containing pathway from central nucleus of the amygdala to bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:360–365. doi: 10.1007/s002130000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. Potentiation of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by the anxiogenic drug yohimbine. Behav Brain Res. 2006;174:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay JM, Zigmond MJ, Abercrombie ED. Increased dopamine and norepinephrine release in the medial prefrontal cortex induced by acute and chronic stress: effects of diazepam. Neuroscience. 1995;64:619–628. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Rizos Z, Sinyard J, Tampakeras M, Higgins GA. The 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro60–0175 reduces cocaine self-administration and reinstatement induced by the stressor yohimbine, and contextual cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1402–1412. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin SM, Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Regional extracellular norepinephrine responses to amphetamine and cocaine and effects of clonidine pretreatment. Brain Res. 1994;654:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricks-Gleason AN, Marshall JF. Post-retrieval beta-adrenergic receptor blockade: effects on extinction and reconsolidation of cocaine-cue memories. Learn Mem. 2008;15:643–648. doi: 10.1101/lm.1054608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Kleber HD. Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:107–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Aston-Jones G. Beta-adrenergic antagonists attenuate withdrawal anxiety in cocaine- and morphine-dependent rats. Psychopharmacology. 1993;113:131–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02244345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Hedaya MA, Pan W-J, Kalivas P. Beta-adrenergic antagonism alters the behavioral and neurochemical responses to cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00089-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highfield D, Yap J, Grimm JW, Shalev U, Shaham Y. Repeated lofexidine treatment attenuates stress-induced, but not drug cues-induced reinstatement of a heroin-cocaine mixture (speedball) seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:320–331. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne MK, Lee J, Chen F, Lanning K, Tomas D, Lawrence AJ. Long-term administration of cocaine or serotonin reuptake inhibitors results in anatomical and neurochemical changes in noradrenergic, dopaminergic, and serotonin pathways. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1731–1744. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y, Martin JL. Cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in mice: induction, extinction and reinstatement by related psychostimulants. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:130–134. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Rivera CA, Feliu-Mojer M, Vázquez-Torres R. Alpha-noradrenergic receptors modulate the development and expression of cocaine sensitization. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1074:390–402. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman KM, Volpicelli JR, Mulvaney F, Alterman AI, Cornish J, Gariti P, Cnaan A, Poole S, Muller E, Acosta T, Luce D, O'Brien C. Effectiveness of propranolol for cocaine dependence treatment may depend on cocaine withdrawal symptom severity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman KM, Dackis C, Lynch KG, Pettinati H, Tirado C, Gariti P, Sparkman T, Atzram M, O’Brien CP. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of amantadine, propranolol, and their combination for the treatment of cocaine dependence in patients with severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;85:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Koek W. Discriminative stimulus properties of cocaine: enhancement by beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology. 1997;131:307–312. doi: 10.1007/s002130050297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich AS, Blendy JA. cAMP response element-binding protein is required for stress but not cocaine-induced reinstatement. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6686–6692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanteri C, Salomon L, Torrens Y, Glowinski J, Tassin JP. Drugs of abuse specifically sensitize noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons via a non-dopaminergic mechanism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1724–1734. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Funk D, Shaham Y. Role of alpha-2 adrenoceptors in stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking and alcohol self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:366–373. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2036-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Tiefenbacher S, Platt DM, Spealman RD. Pharmacological blockade of alpha2-adrenoceptors induces reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in squirrel monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:686–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Flores J, Rodaros D, Stewart J. Blockade of stress-induced but not cocaine-induced reinstatement by infusion of noradrenergic antagonists into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5713–5718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05713.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MY, Yan QS, Coffey LL, Reith ME. Extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats during intracerebral dialysis with cocaine and other monoamine uptake blockers. J Neurochem. 1996;66:559–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66020559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Shepard JD, Scott Hall F, Shaham Y. Effect of environmental stressors on opiate and psychostimulant reinforcement, reinstatement and discrimination in rats: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:457–491. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macey DJ, Smith HR, Nader MA, Porrino LJ. Chronic cocaine self-administration upregulates the norepinephrine transporter and alters functional activity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci. 2003;23:12–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00012.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ, Black JE, Malison RT, Zimmermann RC, Kosten TR, Heninger GR, Price LH. Noradrenergic dysregulation during discontinuation of cocaine use in addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:713–719. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950090045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Newman-Tancredi A, Audinot V, Cussac D, Lejeune F, Nicolas JP, Cogé F, Galizzi JP, Boutin JA, Rivet JM, Dekeyne A, Gobert A. Agonist and antagonist actions of yohimbine as compared to fluparoxan at alpha(2)-adrenergic receptors (AR)s, serotonin (5-HT)(1A), 5-HT(1B), 5-HT(1D) and dopamine D(2) and D(3) receptors. Significance for the modulation of frontocortical monoaminergic transmission and depressive states. Synapse. 2000;35:79–95. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200002)35:2<79::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini C, Bonito-Oliva A, Conversi D, Cabib S. Genetic liability increases propensity to prime-induced reinstatement of conditioned place preference in mice exposed to low cocaine. Psychopharmacology. 2008;198:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Noradrenergic mechanisms in cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:894–902. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbow TC, Parsons B, Wolfe BB. Quantitative autoradiography of beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptors in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 1985;81:1585–1589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redila VA, Chavkin C. Stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking is mediated by the kappa opioid system. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:59–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1122-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith ME, Li MY, Yan QS. Extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats during intracerebral dialysis following systemic administration of cocaine and other uptake blockers. Psychopharmacology. 1997;134:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s002130050454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro Do couto B, Aguilar MA, Manzanedo C, Rodríguez-Arias M, Armario A, Miñarro J. Social stress is as effective as physical stress in reinstating morphine-induced place preference in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2006;185:459–470. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudoy CA, Van Bockstaele EJ. Betaxolol, a selective beta(1)-adrenergic receptor antagonist, diminishes anxiety-like behavior during early withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger DJ, Schoemaker H. Discriminative stimulus properties of 8-OH-DPAT: relationship to affinity for 5HT1A receptors. Psychopharmacol. 1992;108:85–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02245290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schank JR, Liles LC, Weinshenker D. Norepinephrine signaling through beta-adrenergic receptors is critical for expression of cocaine-induced anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HD, Pierce RC. Systemic administration of a dopamine, but not a serotonin or norepinephrine, transporter inhibitor reinstates cocaine seeking in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Erb S, Leung S, Buczek Y, Stewart J. CP-154,526, a selective, non-peptide antagonist of the corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptor attenuates stress-induced relapse to drug seeking in cocaine- and heroin-trained rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;137:184–190. doi: 10.1007/s002130050608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Highfield D, Delfs J, Leung S, Stewart J. Clonidine blocks stress-induced reinstatement of heroin seeking in rats: an effect independent of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:292–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Erb S, Stewart J. Stress-induced relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking in rats: a review. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:13–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, De Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]