Abstract

The regulation of both mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis is key for maintaining the health of a cell. Bcl-2 family proteins, central in apoptosis regulation, also play roles in maintenance of the mitochondrial network. Here we report that Bax and Bak participate in the regulation of mitochondrial fusion in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, primary mouse neurons and human colon carcinoma cells. To assess how Bcl-2 family members may regulate mitochondrial morphogenesis we determined the binding of a series of chimeras between Bcl-xL and Bax to the mitofusins, Mfn1 and Mfn2. One chimera (containing helix 5 (H5) of Bax replacing H5 of Bcl-xL (Bcl-xL/Bax H5)) co-immunoprecipitated with Mfn1 and Mfn2 significantly better than either wild type Bax or Bcl-xL. Expression of Bcl-xL/Bax H5 in cells reduced the mobility of Mfn1 and Mfn2 and co-localized with ectopic Mfn1 and Mfn2 as well as endogenous Mfn2 to a greater extent than wild type Bax. Ultimately, Bcl-xL/Bax H5 induced substantial mitochondrial fragmentation in healthy cells. Therefore, we propose that Bcl-xL/Bax H5 disturbs mitochondrial morphology by binding and inhibiting Mfn1 and Mfn2 activity, supporting the hypothesis that Bcl-2 family members have the capacity to regulate mitochondrial morphology through binding to the mitofusins in healthy cells.

Introduction

Mitochondria routinely divide and fuse through the action of conserved large GTPases. Under physiological conditions the rate of mitochondrial fusion is counterbalanced by the rate of fission to determine the overall length and contiguity of mitochondria (1). The mitofusins, Mfn1 and Mfn2, are large GTPases that reside on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and mediate OMM fusion (2). Another large GTPase, Opa1, which localizes to the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), mediates IMM fusion (3). Mitochondrial fission, on the other hand, is controlled mainly by the large GTPase dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), Fis1 and Mff (4–6).

The mitochondrial network undergoes dramatic rearrangement upon induction of apoptosis, resulting in a fragmented mitochondrial phenotype and altered cristae junctions (7, 8). Indicating that this process may be important for apoptosis, dominant negative forms of Drp1 that antagonize mitochondrial division, delay the release of cytochrome c and onset of cell death (9), although not as potently as some anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, such as Bcl-xL. Moreover, ectopic Mfn2, Opa1 and mutant forms of Opa1 can also confer protection against programmed cell death (10–13). Recently, several members of the Bcl-2 family, including both pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, have been shown to play a role in mitochondrial morphogenesis in healthy cells (14–17). Finding that Bax and Bak promote mitochondrial fusion in healthy cells (14) was unanticipated, as Bax and Bak form foci that co-localize with ectopic Mfn2 and Drp1 at the sites of mitochondrial division to promote mitochondrial fission during apoptosis (18). Bcl-w, an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, on the other hand, was proposed to be important for mitochondrial fission in Purkinje cell dendrites (16). Furthermore, Bcl-xL overexpression promotes both mitochondrial fusion and fission (15, 19), perhaps by altering the relative rates of these opposing processes (17). Although the mechanism through which Bcl-2 family proteins regulate mitochondrial morphogenesis is not well understood, several groups have shown direct interactions between Bcl-2 family members (Bax, Bak, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) and proteins involved in mitochondrial morphogenesis (Mfn1, Mfn2, Drp1 and Fis1) (15, 20–22). Here we extend our previous study (14) by identifying a fragmented mitochondria phenotype and mitochondrial fusion defect in Bax−/− Bak−/− cells of different lineages and species. Additionally, we have found that a Bcl-xL and Bax chimeric protein tightly binds the mitofusins and acts as an inhibitor of mitochondrial fusion.

Results

Mitochondrial fusion defect in Bax−/− Bak−/− cells

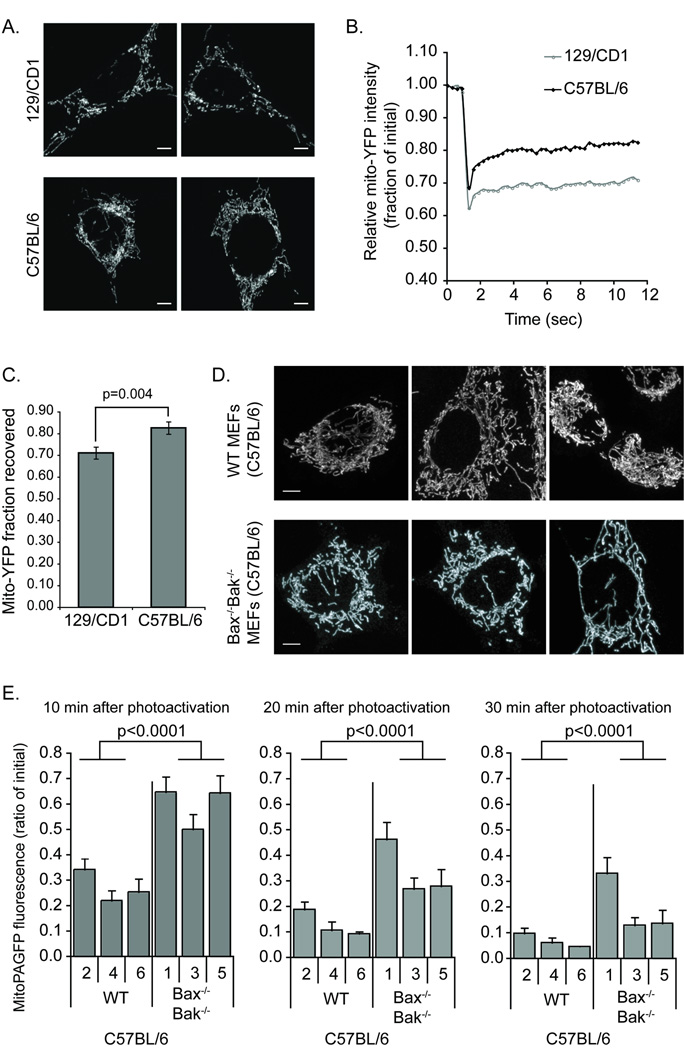

We previously reported that the loss of Bax and Bak due to genetic manipulation, RNA interference or inactivation by a viral protein leads to decreased rates of mitochondrial fusion resulting in fragmentation of the mitochondrial network (14). We therefore examined wild type (WT) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from a different genetic background (C57BL/6) and found that they were considerably more elongated and interconnected (Figure 1A) than the mitochondria in the 129/CD1 WT MEFs described in our previous study (14). To determine statistical significance of this visual determination, the difference between the C57BL/6 and 129/CD1 mitochondrial contiguity was examined by fluorescent recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis of YFP targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (mito-YFP). Upon photobleaching of a region of interest (ROI, 2.1µm circle) within the mitochondrial network, we were able to assess both the depth of the photobleach (Figure 1B) and the degree of fluorescence recovery (Figure 1C), both of which are used as quantitative measures of mitochondrial connectivity (14). Mitochondria in C57BL/6 MEFs showed a significantly faster recovery and thus more interconnectivity than the 129/CD1 MEFs (Figure 1B, C).

Figure 1. Mitochondrial morphology and fusion rate in wild type and Bax−/−Bak−/− MEFs.

(A) Representative cell images of mitochondria from 129/CD1 (top row) and C57BL/6 (bottom row) wild type (WT) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) immunostained with cytochrome c. Scale bar denotes 5 µm. (B) Mitochondrial network connectivity in 129/CD1 (top row, 1A) and C57BL/6 (bottom row, 1A) WT MEFs was measured by FRAP of mito-YFP. The normalized and bleach corrected curves represent an average of 30 measurements. (C) MitoYFP recovery represents the final average ± SEM (n=30) amount of mito-YFP fluorescence in (B) that recovered (i.e. diffused into the bleached area) during the 12-second time period. The p-value was obtained using the student’s t-test. (D) Representative images of cytochrome c immunostained mitochondria in WT (top row) and Bax−/−Bak−/− (bottom row) MEFs from C57BL/6 mice. The scale bar represents 5 µm. (E) Bax−/−Bak−/− MEF cell lines display slower rates of mitochondrial fusion. Mitochondrial fusion was analyzed in a blinded manner in three independently-derived Bax−/−Bak−/− MEF lines from C57BL/6 mice (clones 1, 3, 5) and WT strains from the same genetic background (clones 2, 4, 6). The average ± SEM (n >17) fluorescence remaining over time was plotted. Each time point was examined using the MANOVA model: at 10 minutes, the mean fluorescence intensity in the Bax−/−Bak−/− group was significantly higher (F1, 27 = 38.91, p < 0.0001) than the average of the WT group. Similarly, the Bax−/−Bak−/− group means were significantly higher (20 min: F1, 27 = 37.67, p < 0.0001; 30 min: F1, 27 = 23.01, p < 0.0001) than the means of the WT group at later time points. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

The mitochondria in the Bax−/−Bak−/− MEFs from the C57BL/6 background did not appear as fragmented as the mitochondria in the Bax−/−Bak−/− MEFs from the 129/CD1 background (14), perhaps owing to the more fused phenotype of the parental C57BL/6 cells relative to the 129/CD1 cells. However, when we compared 15 high-resolution micrographs each from C57BL/6 WT and Bax−/−Bak−/− MEFs collected in a blinded manner, there was a clear difference in the degree of mitochondrial connectivity (for representative images see Figure 1D). The mitochondria in Bax−/−Bak−/− C57BL/6 cells were less interconnected than the mitochondria of WT cells on the same genetic background when compared visually (Figure 1D). We analyzed mitochondrial fusion rates in C57BL/6 WT and C57BL/6 Bax−/−Bak−/− cells using photoactivatable GFP targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (mito-PAGFP) to quantify the dilution of activated fluorescence in individual mitochondria upon organelle fusion, as described previously (23). In this assay, a reduction of fluorescence reflects dilution of the photoactivatable GFP upon mitochondrial fusion. Three independently derived clonal lines from WT (clones 2,4,6) and Bax−/−Bak−/− (clones 1,3,5) mice from a C57BL/6 background were analyzed. These data show that cells lacking both Bax and Bak consistently displayed significantly slower mitochondrial fusion rates (p<0.0001) at each time point (10, 20 and 30 minutes after photoactivation), as compared to WT cells (Figure 1E). Thus, despite the difference in basal mitochondrial connectivity between these two genetic backgrounds, loss of Bax and Bak decreases the rate of mitochondrial fusion relative to WT cells of the same background.

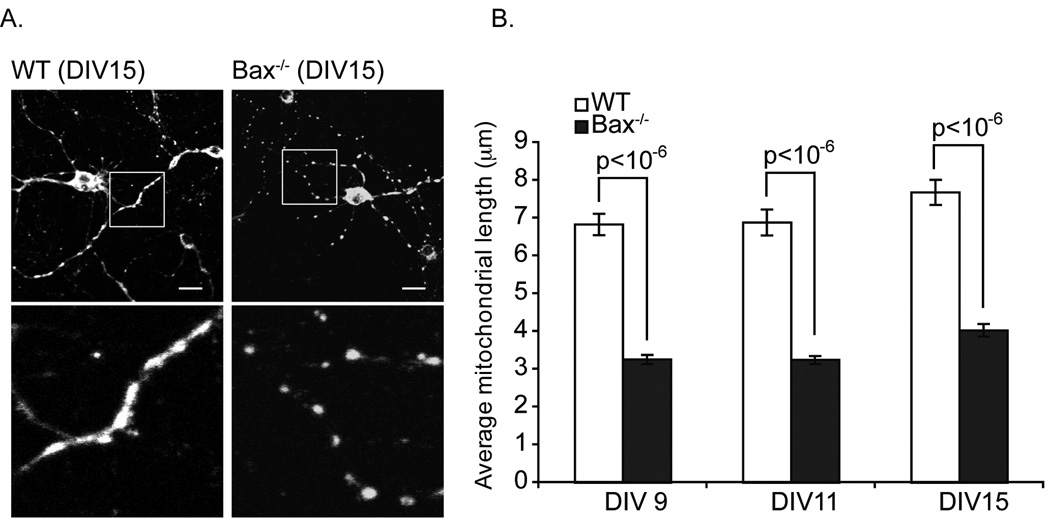

It has been previously reported that neurons lack full-length Bak (24). Therefore, we investigated the mitochondrial morphology in primary cortical neurons from C57BL/6 WT and Bax−/− mice (originally from 129/CD1 backcrossed >19 generations into a C57BL/6 background) (25). As shown by Figure 2A, Bax−/− cortical neurons contain mitochondria that are substantially shorter than mitochondria from WT cortical neurons. To quantify this, we measured the length of 15 mitochondria located within neuronal processes in each of 15 WT and Bax−/− neurons after culturing the cells for 9, 11 and 15 days in vitro (DIV). When analyzing neuronal mitochondria, we measured axonal or dendritic mitochondria rather than those in the cell body, as the mitochondria were well distributed throughout the processes and individual organelles were easily distinguishable. The average mitochondrial length in WT neurons was approximately 2-fold longer than mitochondria in Bax−/− neurons at each age (9, 11 and 15 DIV) (p<0.001; Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Mitochondrial morphology in WT and Bax−/− neurons.

(A) Representative images of cytochrome c stained mitochondria located within neuronal processes of C57BL/6 WT or Bax−/− mouse neurons analyzed at DIV 15. The scale bar represents 10 µm. (B) Mitochondria in WT and Bax−/− cortical neurons were isolated and grown in vitro for 9, 11 or 15 days (days in vitro, DIV) were measured using MetaMorph image analysis software. The average mitochondrial length (µm) ± SEM (n=225) is plotted for each cell type at each time point (DIV). p-values are noted in the figure. These data are representative of three independent experiments.

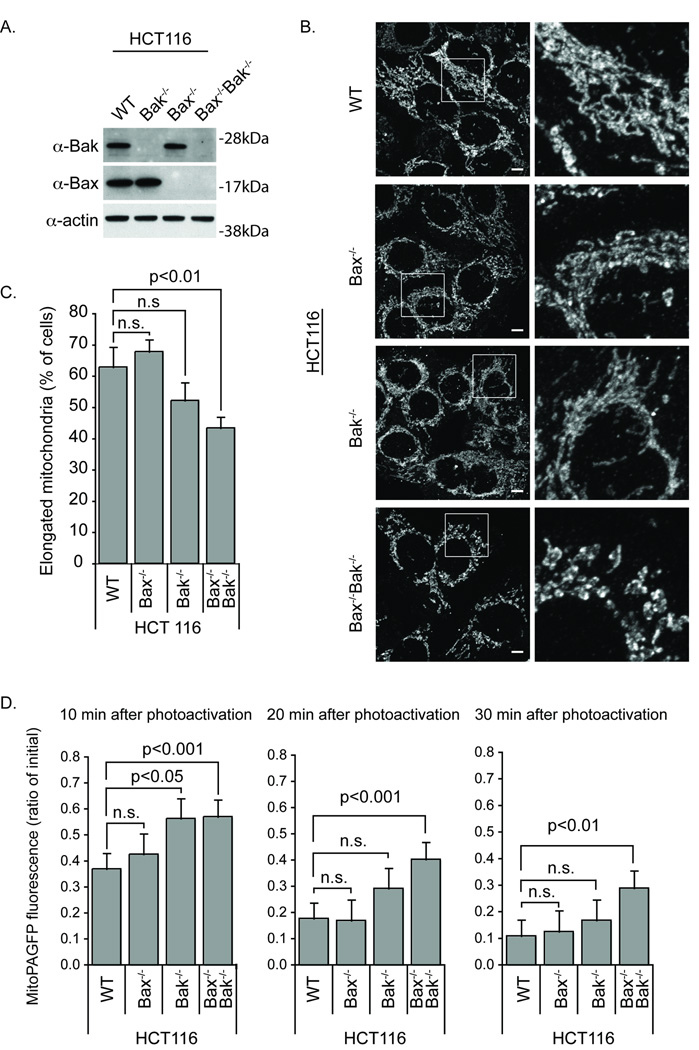

To test whether Bax and Bak expression affects mitochondrial fusion rates in human cells, we turned to HCT116 cells, a human colon carcinoma line amenable to gene targeting approaches previously used to generate Bax−/− cells (26). We deleted the Bak gene by homologous recombination in the WT HCT116 cells to generate Bak−/− HCT 116 cells and in the Bax−/− HCT116 cells to generate Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells (Wang and Youle, manuscript in preparation; Figure 3A). Consistent with our results in MEFs, mitochondria in human cells lacking both Bax and Bak are significantly less visually interconnected compared to WT, Bax−/−, or Bak−/− HCT116 cells (Figure 3B, C). We also assessed mitochondrial fusion rates in these four cell lines using the photoactivatable GFP fusion assay (23). While there was little difference in the fusion rates between WT, Bax−/−, and Bak−/− HCT116 cells, the mitochondria in Bax−/−Bak−/− cells displayed significantly slower fusion rates than either WT and Bax−/− cells at each time point analyzed (Figure 3D). Similar to the results for murine cells, these results demonstrate that upon genetic deletion of both Bax and Bak mitochondrial fusion is impaired.

Figure 3. Mitochondrial morphology and fusion rate in wild type, Bax−/− and Bax−/− Bak−/− HCT116 cells.

(A) Western blot analysis of Bak and Bax protein levels in WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells. (B) Representative images of cytochrome c immunostained mitochondria in WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/− Bak−/− HCT116 cells. Scale bar represents 5 µm. (C) Quantification of mitochondrial morphology visualized using anti-cytochrome c antibody in WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells. 100 cells total per cell type were quantified in a blinded manner, and the average number of cells with an elongated mitochondrial morphology was plotted ± SD. The difference between cell lines was significant via the student’s t-test. (D) Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells have slower rates of mitochondrial fusion. Mitochondrial fusion rates were analyzed in WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells. The average ± SEM (n >20) fluorescence remaining over time was plotted. The data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (Cell line variation F=13.73, p<0.001) followed by the Bonferroni posttest, and p-values are noted on the figure. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Chimeric Bcl-xL Bax helix 5 strongly binds Mfn1 and Mfn2

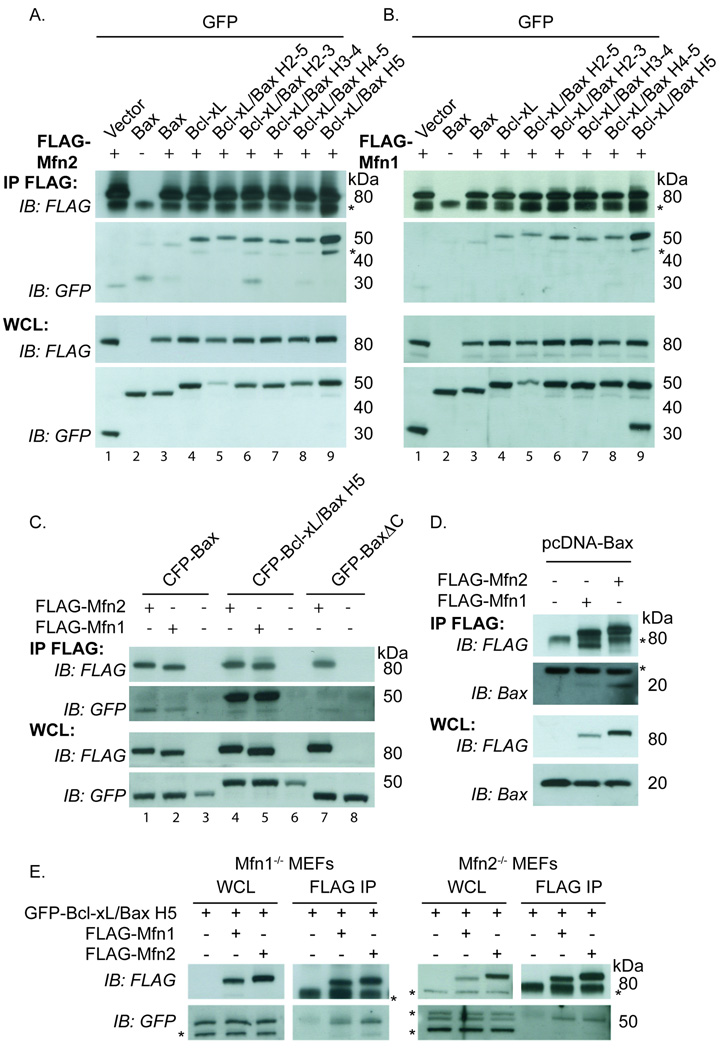

Bax and Bak have been proposed to regulate mitochondrial morphology through interactions with the mitofusins (14, 15, 20). To further investigate this interaction we used a series of GFP-tagged chimeric proteins replacing helices of Bcl-xL with the corresponding helices of Bax. This series of chimeras was originally designed to assay which helices were important for the apoptotic function of Bax (27). Using co-immunoprecipitation experiments we found that all chimeras, as well as WT Bax and Bcl-xL bound both Mfn1 and Mfn2 (Figure 4A, B). Since, the GFP vector control sample had trace binding, we also performed a co-immunoprecipitation experiment using untagged Bax and found that untagged Bax bound both FLAG-Mfn1 and FLAG-Mfn2 (Figure 4D). Surprisingly, one chimera, consisting of Bcl-xL with helix 5 of Bax replacing the helix 5 of Bcl-xL (Bcl-xL/Bax H5), bound Mfn1 and Mfn2 significantly better than either WT Bax or WT Bcl-xL (Figure 4A, B lane 9). Approximately 3% of GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 is bound to FLAG-Mfn2 (Supplemental Figure 1B). The increased binding between Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and the mitofusins could be due to propensity of this chimera to spontaneously form oligomers (27). However, since Bcl-xL/Bax H2-5 and Bcl-xL/Bax H4-5 (Figure 4A, B lanes 5 and 8), which also display spontaneous oligomerization (27), bind substantially less to the mitofusins than Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (Figure 4A, B lane 9) arguing against spontaneous oligomerization as the cause of enhanced binding.

Figure 4. A chimera containing helix 5 of Bax replacing helix 5 of Bcl-xL shows enhanced binding to Mfn1 and Mfn2 relative to WT Bax and Bcl-xL.

(A–B) HeLa cells transiently expressing FLAG-Mfn2 (A) or FLAG-Mfn1 (B) and GFP vector, GFP-Bax, GFP-Bcl-xL or various GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax chimeric proteins were treated with 10µM QVD during the transfection were immunoprecipitated with FLAG conjugated beads. (C) HeLa cells transiently expressing FLAG-Mfn1 or FLAG-Mfn2 and CFP-Bax, CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 or GFP-BaxΔC were immuonoprecipitated with FLAG beads. (D) HeLa cells transiently expressing FLAG-Mfn1 or FLAG-Mfn2 and untagged pcDNA-Bax were treated with 10µM QVD and immunoprecipitated with FLAG beads. (E) Mfn1−/− MEFs or Mfn2−/− MEFs transiently expressing FLAG-Mfn2 or FLAG-Mfn1 and GFP-Bcl-xL Bax H5 were immunoprecipitated with FLAG beads. FLAG bead immunoprecipitate (IP) and whole cells lysate (WCL) samples were analyzed using FLAG and GFP antibodies (A–C and E) or FLAG and Bax antibodies (D). Asterisks represent non-specific bands. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

We then compared the binding of Mfn1 and Mfn2 with Bax and the Bcl-xL/Bax H5. In accordance with Brooks et al. (20), Bax has a slightly greater interaction with Mfn2 than Mfn1, while Bcl-xL/Bax H5 interacts equally well with Mfn1 and Mfn2 (Figure 4C). We confirmed the specificity of the binding of Bcl-xL/Bax H5 to both Mfn1 and Mfn2 using Mfn1−/− MEFs and Mfn2−/− MEFs. Bcl-xL/Bax H5 binds Mfn1 in the absence of Mfn2 (using Mfn2−/− MEFs) and Bcl-xL/Bax H5 binds to Mfn2 in the absence of Mfn1 (using Mfn1−/− MEFs) (Figure 4E). These results rule out an indirect association of Bcl-2 family proteins with Mfn1 through Mfn2 and vice versa. As Bax is mainly cytosolic with a small fraction lightly bound to mitochondria, we asked whether removing the C-terminal transmembrane domain (BaxΔC) would alter its binding to Mfn2. BaxΔC appears to bind Mfn2 slightly less avidly than WT Bax, indicating that mitochondrial binding is likely important for the Bax-Mfn2 interaction (Figure 4C lane 1 vs. lane 7).

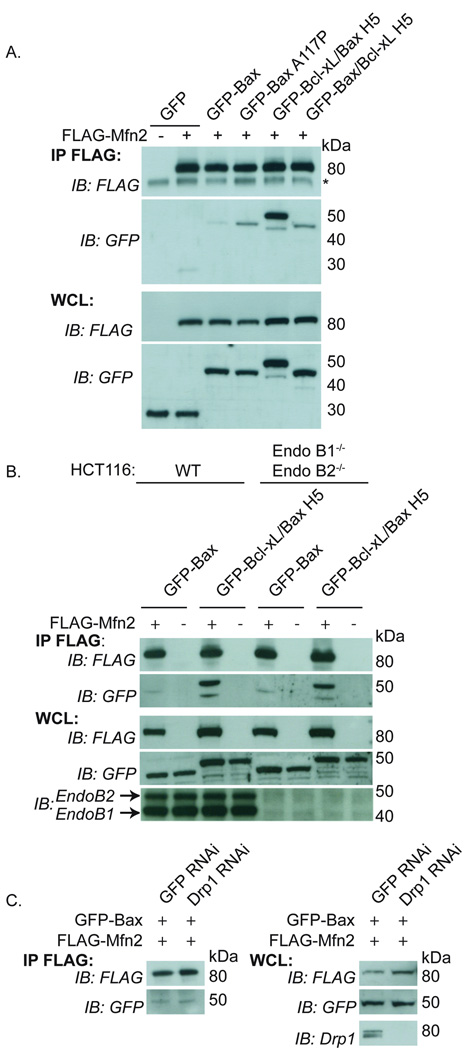

Since H5 is the central hairpin of Bax, we hypothesized that Bcl-xL/Bax H5 could have an altered conformation allowing increased binding between the mitofusins and the H5 region. To address this possibility, we made a series of mutations (Supplemental Figure 1C) within Bcl-xL/Bax H5, mutating the residues of Bax H5 back to the original Bcl-xL H5 amino acids. As shown in Supplemental Figure 1D, we did not detect any decrease in binding after mutation of 5 different positions within the H5 region. Therefore, we suggest that Bcl-xL/Bax H5 displays a unique conformation, relative to Bcl-xL or the other 4 Bcl-xL-Bax chimeric proteins, that allows enhanced binding to the mitofusins. To further examine the role of H5 of Bax, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation experiment using Bax A117P (proline mutation within H5 (27) and GFP-Bax/Bcl-xL H5, the reverse chimera. We found that while both of these constructs had increased binding to Mfn2 relative to WT Bax, neither bound Mfn2 to the enhanced level of GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (Figure 5A). These results are consistent with the model that conformational changes in Bax may mediate mitofusin binding.

Figure 5. Co-immunoprecipitation of GFP-Bax and GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and the mitofusins.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 and GFP, GFP-Bax, GFP-Bax A117P (mutation within H5), GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 or GFP-Bax/Bcl-xL H5 (the reverse H5 chimera) and immunoprecipitated with FLAG beads and blotted for FLAG and GFP. (B) WT HCT116 and EndoB1−/− EndoB2−/− HCT116 cells transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 and GFP-Bax or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 were immunoprecipitated with FLAG beads and blotted for FLAG, GFP, Endophilin B1 and Endophilin B2. (C) Drp1 RNAi or control GFP RNAi HeLa cells (31) were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 and GFP-Bax and immunoprecipated and blotted as in (A). Drp1 protein level after RNAi treatment was analyzed using anti-Drp1 antibody. Asterisks represent non-specific bands. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

To elucidate possible mediators of the mitofusin-Bcl-2 family member interaction, we examined cells lacking endophilin B1 and endophilin B2. Endophilin B1 (also known as Bif-1 and SH3GLB1) has been shown to interact with Bax (28, 29). Since endophilin 1, a homolog of endophilin B1, binds to dynamin and mediates endocytosis (30), we hypothesized that endophilin B1 and/or B2 could be mediating the interaction between the mitofusin members of the dynamin family and the Bcl-2 family member proteins to regulate mitochondrial morphology. Additionally, downregulation of endophilin B1 alters mitochondrial morphology, causing a dissociation of the outer mitochondrial membrane from the inner mitochondrial membrane resulting in hyperfusion of the outer mitochondrial membrane with fragmentation of the inner mitochondrial membrane (31). Little is known about endophilin B2 (28). We targeted the endophilin B1 gene and endophilin B2 gene by homologous recombination in the HCT116 cells to generate EndoB1−/−EndoB2−/− HCT116 cells (Wang and Youle, manuscript in preparation). Using these cells we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments and found that the interaction between Mfn2 and Bax or Mfn2 and Bcl-xL/Bax H5 was not altered by the absence of both endophilin B1 and endophilin B2 (Figure 5B).

The C. elegans Bcl-2 family protein, Ced-9, also mediates mitochondrial fusion and is hypothesized to do so by increasing the GTPase activity of Drp1 (32) and/or by interacting with Fzo-1, the C. elegans mitofusin homolog (33). Tan et al (32) proposed that Drp1 could inhibit Ced-9 and thereby alter the interaction of Ced-9 with Fzo-1. To address if the interaction between Mfn2 and Bax was increased in the absence of Drp-1, we used RNAi to knockdown Drp-1 expression levels (31). Decreasing the amount of Drp1 in cells did not alter the interaction between Mfn2 and Bax as analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation experiments (Figure 5C), indicating that the Mfn2-Bax interaction is likely not regulated by Drp1.

Bcl-xL/Bax H5 alters Mfn1 and Mfn2 in situ

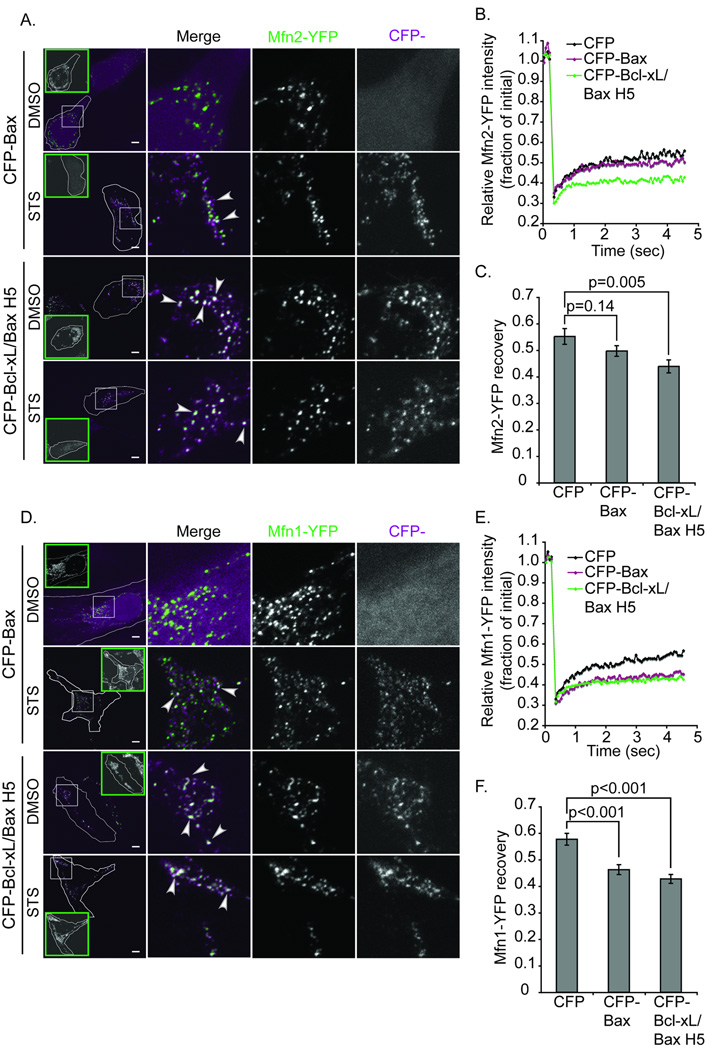

To corroborate in living cells the co-immunoprecipitation evidence that Bcl-xL/Bax H5 binds Mfn1 and Mfn2, we utilized a smaller scale FRAP assay to examine the mitochondrial membrane mobility of Mfn1-YFP and Mfn2-YFP in the presence of either CFP, CFP-Bax or CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 in HeLa cells as previously described (14). We found that the mobility of both Mfn1-YFP and Mfn2-YFP is reduced in the presence of CFP-Bax and reduced even further in the presence of CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 relative to the mobility of Mfn-YFP in the presence of CFP (Figure 6B–C, 6E–F). This further supports the co-immunoprecipitation data by demonstrating in living cells an enhanced interaction between Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and Mfn1 and Mfn2 relative to that of WT Bax.

Figure 6. Bcl-xL/Bax H5 co-localizes with overexpressed Mfn1 and Mfn2 and decreases the mobility of Mfn1 and Mfn2 more efficiently than Bax.

(A, D) Mitofusin/Bcl-2 family colocalization was examined in HeLa cells transiently expressing Mfn2-YFP (A) or Mfn1-YFP (D) and CFP-Bax or CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and treated with 10µM QVD and 1µM STS or DMSO for 90min. Green inset boxes show cytochrome c staining of the outlined cell thus representing cytochrome c release in most STS treated cells (the CFP-Bax STS sample in Figure 6D shows partial cytochrome c release, while the CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 STS sample in Figure 6D shows intact cytochrome c). White boxes show areas of the cells used for the higher magnification merge image. Arrowheads denote some of the white regions of colocalization. Scale bar denotes 5µm. (B–C, E–F) Mitofusin protein mobility was assessed by FRAP in HeLa cells transiently transfected with Mfn2-YFP (B–C) or Mfn1-YFP (E–F) and CFP, CFP-Bax or CFP-Bcl-xL/BaxH5. (B, E) Average curves from 30 individual ROIs per condition. (C, F) Average ± SEM of the final recovery of 30 individual regions. The p-value was obtained using student’s t-test. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

As it was previously shown that CFP-Bax and Mfn2-YFP co-localize during apoptosis (18), we wanted to examine if Mfn1-YFP co-localized with CFP-Bax and to what extent CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 co-localized with Mfn1-YFP and Mfn2-YFP. As previously reported (14), Mfn2-YFP co-localizes with CFP-Bax during apoptosis (Figure 6A). Mfn1-YFP also co-localizes with CFP-Bax during apoptosis (Figure 6D). In accordance with co-immunoprecipiation and FRAP data, CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 co-localized with Mfn1-YFP and Mfn2-YFP to a greater extent relative to CFP-Bax both in the presence and absence of apoptosis (Figure 6A, D).

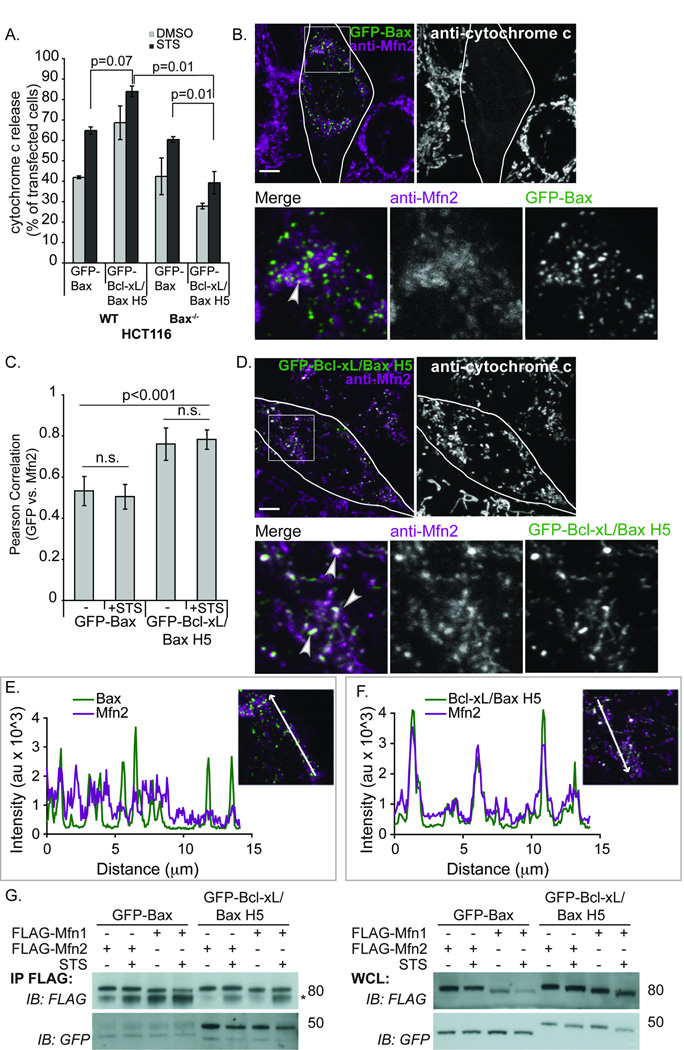

Since overexpressed Mfn2-YFP had enhanced co-localization with CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 we compared the localization of endogenous Mfn2 in cells expressing CFP-Bax or CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5. Although both Bax and Bcl-xL/Bax H5 can promote apoptosis in WT HCT116 cells, the Bcl-xL/Bax H5 chimera had a diminished ability relative to WT Bax or several of the other chimeras to induce apoptosis in cells lacking endogenous Bax ((27) and Figure 7A). Therefore, we used Bax−/− HCT116 cells, either STS or DMSO treated, transiently expressing CFP-Bax or CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and then immunostained for endogenous Mfn2 and cytochrome c. The anti-Mfn2 antibodies demonstrate that endogenous Mfn2 forms distinct foci on the mitochondria, specifically localizing to tips and junction points (Supplemental Figure 4). Deletion of Bax or Bak alone does not substantially alter the pattern of Mfn2 foci, but deleting Bax and Bak results in an increased number of cells with fragmented mitochondria, which appear to have fewer Mfn2 foci (Supplemental Figure 2B bottom panel). The endogenous Mfn2 foci weakly co-localized with CFP-Bax as shown by the few white areas (arrowhead) denoting merged colors in Figure 7B and a minor amount of overlap in the line scan plot shown in Figure 7E. This could be due to the weaker focal localization of endogenous Mfn2 relative to ectopic Mfn2-YFP (Supplemental Figure 2A, B). Interestingly, the CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 expression enhanced the focal localization of endogenous Mfn2, thereby displaying dramatically increased co-localization between Mfn2 and Bcl-xL/Bax H5 relative to WT Bax, as shown by the over-lapping line-scan plot in Figure 7F and the increased amount of white areas on the merged image in Figure 7D relative to Figure 7B (see arrow heads for examples). The enhanced co-localization was quantified using Volocity software to calculate the Pearson’s correlation value. The closer the value is to 1, the stronger the co-localization between Mfn2 and the GFP-tagged protein. Figure 7C demonstrates that GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and Mfn2 have a significantly higher Pearson’s correlation value as compared to GFP-Bax and Mfn2, both in the presence and absence of apoptotic stimulus. Furthermore, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation assay in the presence and absence of STS and found no change in the interaction of GFP-Bax or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 with FLAG-Mfn1 or FLAG-Mfn2 upon induction of apoptosis (Figure 7G). Overall, these data indicate that as a consequence of strong binding of Bcl-xL/Bax H5 to Mfn1 and Mfn2 (Figure 4A, B), Mfn1 and Mfn2 lose some of their membrane mobility (Figure 6B, E) and form large foci, which strongly co-localize with Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (Figure 6A, 6D, 7D).

Figure 7. Bcl-xL/Bax H5 co-localizes with endogenous Mfn2 more efficiently than Bax.

(A) WT HCT116 or Bax−/− HCT116 cells were transfected with GFP-Bax or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5, treated with 10µM QVD and 1µM STS or DMSO for 4hr and immunostained for cytochrome c. 100 cells were counted in triplicate, analyzing the percentage of cells releasing cytochrome c. P-values were calculated using the students t-test. (B–F) Bax−/− HCT116 cells were treated with the 10 µM QVD, transfected with GFP-Bax (B, C, E) or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (C, D, F), immunostained for cytochrome c and endogenous Mfn2. White areas designate co-localization or merged regions (represented by arrowheads). Scale bar denotes 5µm. (C) HCT116 Bax−/− cells were prepared as above and treated for 2 hr with 1µM STS or DMSO (−). At least 20 cells per condition were imaged and analyzed using the Volocity program to calculate the Pearson Correlation value (co-localization) between Mfn2 and GFP-Bax or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5. The p-values were obtained using student’s t-test. (E, F) Line scan plots of the images shown in 7B and 7D, respectively were analyzed for co-localization of GFP and Mfn2 signals using the LSM 510 program. (G) Bax−/− HCT116 cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn1 or FLAG-Mfn2 and GFP-Bax or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5. Following treatment for 4 hr with 1µM STS or DMSO, the cells were collected, immunoprecipitated with FLAG beads and blotted for FLAG and GFP. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

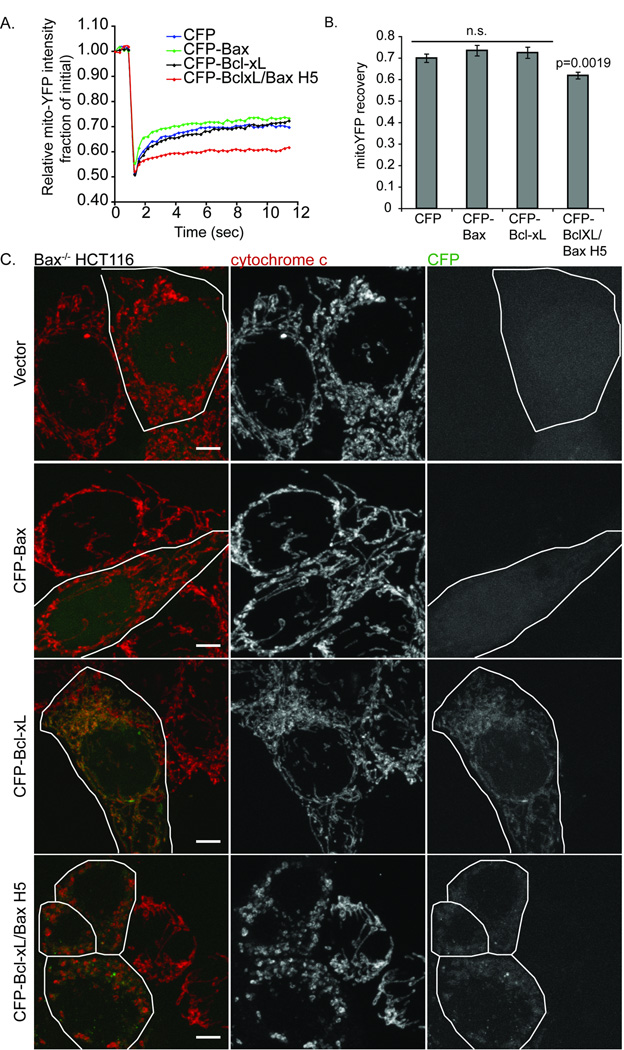

Bcl-xL/Bax H5 induces mitochondrial fragmentation without cytochrome c release

The enhanced interaction with Bcl-xL/Bax H5 could affect Mfn2 activity to promote mitochondrial fusion. Examining the mitochondrial morphology upon CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 expression reveals a dramatic fragmentation of the mitochondria in healthy Bax−/− HCT116 cells, in contrast to expression of CFP-Bax, CFP-Bcl-xL or the vector control (Figure 8C). Using FRAP analysis to measure mitochondrial connectivity, we found that in cells expressing CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5, mitoYFP has a significantly slower fluorescence recovery due to the fragmentation of mitochondria (Figure 8A, B). To verify that the dramatic fragmentation induced by CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 did not result from apoptosis, we immunostained the cells used in the FRAP analysis for cytochrome c and found that the majority of cells that had fragmented mitochondria resulting from CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 expression retained cytochrome c within the mitochondria (Figure 7A, Figure 8C), indicating that these cells were not undergoing apoptosis. Overall, it appears Bcl-xL/Bax H5 binds with excessive avidity to the mitofusins thereby preventing them from functioning in the promotion of mitochondrial fusion and thus, owing to ongoing mitochondrial division causes a fragmented phenotype of the mitochondrial network.

Figure 8. Bcl-xL/Bax H5 induces dramatic mitochondrial fragmentation.

Bax−/−HCT116 cells were transiently transfected with mito-YFP and either CFP-tagged Bax, Bcl-xL, Bcl-xL/Bax H5 or vector control. (A) The average mitochondrial connectivity of 30 different ROIs within these cells was measured by FRAP. (B) The final average fluorescence recovery ± SEM (n=30) of the curves shown in (A), the p-values were obtained using the student’s t-test. (C) Cells from (A) were fixed following the FRAP experiment and immunostained for cytochrome c. Scale bar represents 5µm. Note mitochondrial fragmentation induced by the H5 chimera (bottom panel). These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Discussion

This study extends our previous observations that Bax and Bak participate in the regulation of mitochondrial fusion in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (14) to mouse embryonic fibroblasts of another genetic background, primary mouse neurons and human colon carcinoma cells. We also demonstrate that Bcl-2 family member proteins, when engineered into altered conformations, have the capacity to inhibit mitochondrial fusion, further linking the Bcl-2 family to regulation of mitochondrial morphogenesis. The Bcl-xL/Bax H5 chimera is a tool that demonstrates that mitochondrial fusion can be modulated through Bcl-2 family member interactions with mitofusins.

The absence of Bax and Bak decreases mitochondrial fusion rates and the overall connectivity of these organelles. However, as WT MEFs of different mouse strains differ in mitochondrial connectivity, the contribution of Bax and Bak to mitochondrial fusion may depend on other genetic factors. Based on this, it is tempting to speculate that as in the case of apoptosis regulation, the overall activity of different members of the Bcl-2 family and their integration might be critical for their non-apoptotic functions in mitochondrial fusion and/or fission (34). Since pro-apoptotic Bax and Bak and anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL increase mitochondrial length in healthy cells, these proteins might act cooperatively to regulate the steady state of the mitochondrial network prior to apoptosis induction. Moreover, the regulation of mitochondrial morphology could be a key evolutionarily conserved role of the Bcl-2 family member proteins, since not all Bcl-2 family proteins, such as Drosophila Debcl and Buffy, have essential roles in apoptosis (35). However, it remains to be determined whether Debcl and Buffy regulate mitochondrial morphogenesis.

Recently, Hardwick and colleagues thoroughly examined the processes leading to longer mitochondria by overexpression of Bcl-xL (17). They found that in neurons Bcl-xL induced increases in the rates of both fusion and fission of mitochondria and also increased mitochondrial biomass. However, it remains to be determined how Bax, Bak and other Bcl-2 family proteins mechanistically intersect mitochondrial fusion and fission. Although binding of Bax or Bak to the mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn2 has been proposed to regulate mitochondrial fusion rates (15, 18, 20), precisely how this interaction may affect Mfn2 activity needs to be elucidated.

Ced-9, the C. elegans Bcl-2 homologue, has been shown to cause extensive mitochondrial fusion when overexpressed in mammalian cells as well as in C. elegans striated muscle cells (15, 32, 33). Ced-9 interacts with human Mfn2 (15) and the C. elegans mitofusin homologue, Fzo-1, likely via the coiled-coil domain located between the GTPase domain and the first transmembrane domain of Fzo-1 (33). Consistent with this, we have performed a series of co-immunoprecipation assays between Bax and fragments of Mfn2 and identified that the GTPase domain of Mfn2 alone fails to bind Bax (data not shown), further indicating that the GTPase domain does not seem to be the binding region. Moreover, Mfn2 bound GTP similarly in the presence or absence of Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (Supplemental Fig 1A), indicating that enhanced binding between Mfn2 and Bcl-xL/Bax H5 does not impair GTP-binding function of Mfn2.

The strong interaction between Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and Mfn2 seems to lock the mitofusins into a complex that cannot function in mitochondrial fusion. In order for mitochondrial fusion to proceed, we hypothesize that Mfn2 requires the ability to cycle into and out of the foci that it forms on the outer mitochondria membrane. A mutation within the GTPase domain, Mfn2K109T, enhances the focal localization of Mfn2, while deletion of the C-terminal coiled-coil domain, Mfn21–703, completely eliminates that ability of Mfn2 to form foci (14). Both of these alterations in Mfn2 result in the loss of fusogenic function. Moreover, the focal localization of Mfn2 is reduced in the absence of Bax and Bak ((14) and Supplemental Figure 2) and is increased by the expression of Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (Figure 7D). Therefore, it seems plausible that disruption in the ability to form foci, or disruption in the breakdown of the foci or cycling out of the foci, could affect the mitochondrial fusion rate. We propose that Bcl-xL/Bax H5 is structurally impeding Mfn2 from cycling out of the foci.

Since point mutations within the H5 region of Bcl-xL/Bax H5 did not substantially alter binding between Mfn2 and Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (Supplemental Figure 1D) we suggest that a unique protein conformation of Bcl-xL/Bax H5 results in the enhanced binding to Mfn2. This conformation may expose an important region of Bcl-xL to Mfn2 that is normally sterically blocked. Additionally, creating the reverse chimera, Bax/Bcl-xL H5 resulted in increased binding to Mfn2 relative WT Bax and Mfn2, but did not result in as strong binding as Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (Figure 5A). Therefore, conformational changes of the Bcl-2 family members might be important for interactions with mitofusins. However, it still remains to be elucidated how native Bcl-2 family proteins regulate the mitofusins and mitochondrial fusion. We propose that distinct conformations of Bax regulate mitochondrial fusion in healthy cells whereas conformations of Bax that develops specifically during apoptosis mediate induction of mitochondrial fragmentation.

Materials & Methods

Cell Culture

All cells were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37°C. C57BL/6 WT and Bax−/−Bak−/− MEFs were cultured in complete DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. HCT116 cells were grown in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 4 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM non-essential amino acids (NEAA), 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B 27 supplement, 4 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin.

Antibodies and Chemicals

Cytochrome c antibody (BD Biosciences, CA) was used as a primary antibody for immunostaining mitochondria, with Alexa-Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse as the secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, OR). For immunostaining of endogenous Mfn2, a custom-made rabbit polyclonal antibody against amino acids 1–405 (Covance, PA) was used with Alexa-Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit as the secondary (Molecular Probes). For immunblotting, rabbit polyclonal anti-Bak (NT; Millipore, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax (NT; Millipore), mouse monoclonal anti-Flag (M2; Stratagene, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (Invitrogen, CA), mouse monoclonal anti-Endophilin B1 (Imgenex, CA), mouse monoclonal anti-Endophilin B2 (Novartis, Basel) and mouse monoclonal anti-Drp1 (BD Biosciences, CA) were used as primary antibodies. Anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Biosciences, PA) was used. 10–20µM QVD (a caspase inhibitor, SM Biochemicals, CA) and 1µM STS (Sigma, MO) were prepared from stock solutions in DMSO.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells were transiently transfected according to manufacturer’s protocol with FLAG-Mfn constructs and GFP-Bcl-2 family proteins using Effectene (Qiagen, CA) for HeLa cells, Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) for HCT116 cells, or Fugene HD (Roche, Switzerland) for MEF cells. Cells were lysed in 2% CHAPS buffer (25mM HEPES/KOH, 300 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), pH 7.5) and 1–3 mg of whole cell lysate (WCL) was mixed with FLAG-conjugated beads (Sigma) or GTP agaraose beads ((36), Sigma) for 2–4 hours, rotating at 4°C. Immunoprecipitate (IP) and WCL samples were analyzed using FLAG and GFP antibodies.

Immunofluorescence

MEFs and HCT116 cells were seeded at 4 × 104 and 2 × 105, respectively, per well and cultured for 24 hours. The cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and immunostained with cytochrome c antibody to mark mitochondria, as previously described (14). For WT 129/CD1 and C57BL/6 cells (Figure 1A) and HCT116 Bax−/− cells (Figures 7, 8C), images were collected on a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope; Plan-Apochromat 100×/1.4 Oil DIC objective; zoom 1.5. For WT and Bax−/− Bak−/− MEFs from C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1D) and WT, Bax−/−, Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 (Figure 3B) images were collected on a Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope using a 63× magnification/1.4-numerical aperture Apochrome objective. Neurons (Figure 2A) were cultured in glass chamber slides for 9, 11 or 15 days, then fixed and immunostained with cytochrome c antibody and images were collected on a Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope using a 63× magnification/1.4-numerical aperture Apochrome objective.

For the line scan plot and co-localization analysis, images were acquired using a 100× objective (1.5 zoom) using a consistent setting for Mfn2, while the GFP settings were varied based on the intensity of each transfected cell. Z-stacks from the images were analyzed using the Volocity program (Perkin Elmer, MA) to calculate the Pearson Correlation value (co-localization) between Mfn2 and GFP-Bax or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5. The line scan plots were generated using the LSM 510 software (Zeiss, NY).

Mitochondrial photoactivation fusion assay

Cells were transiently transfected using Fugene 6 with a photoactivatable-GFP targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (mito-PAGFP). A small region (2 µm) containing multiple mitochondria was activated using a 413 nm laser. Images were acquired at 0, 10, 20 and 30 min post-photoactivation. The fluorescence intensity at 0, 10, 20 and 30 min post-activation was measured using Metamorph Software (Molecular Devices, Downington PA). Both the activated fluorescence volume (above approx. 120 a.u.) and total mitochondrial volume (above approx 40 a.u.) was measured for each ROI. The activated fluorescence volume was divided by the total mitochondrial fluorescence volume and the data set was normalized to the post-activation time point (t=0 min). The average ± SEM fluorescence remaining over time was plotted. More rapid decreases in fluorescence intensity represent higher rates of mitochondrial fusion.

Mitochondrial connectivity FRAP assay

Cells were transiently transfected using Fugene 6 with YFP targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (mito-YFP). A 36 µm by 18 µm rectangle was imaged with the 100× objective (zoom 2.5) before and after a 4-iteration (Figure 1 B, C) or 6 iteration (Figure 7 A, B) photobleach of a 2.1 µm circle placed over multiple mitochondria. 40 images were recorded every 0.29 sec, with a total elapsed time of 11.43 sec. Using the LSM 510 software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc) three regions were measured: FRAP, non-specific photobleach and background. The data was normalized, background subtracted and bleach corrected according to Phair and Misteli (37).

Mitochondrial protein mobility FRAP assay

Cells were transiently transfected using Fugene 6 with Mfn2-YFP and CFP-tagged Bcl-2 family proteins. The type of FRAP in Figure 6 utilizes a smaller bleach region (0.5µm), a smaller imaging rectangle (25µm by 1.25µm), 5 bleach iterations and a shorter recovery time (4.7 sec) than the mitochondrial connectivity FRAP described above. Data analysis is identical to mitochondrial connectivity FRAP as described above.

Quantification of mitochondrial morphology

Mitochondria in MEFs or HCT116 cells immunostained with cytochrome c antibody were analyzed visually by confocal microscopy (63× oil objective). Cells were quantified as having either mostly elongated (interconnected) mitochondria or mostly fragmented mitochondria. The average percentage of cells quantified as having elongated mitochondria was plotted. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Mitochondria in neuronal processes were visualized by staining with anti-cytochrome c antibody and imaged using a Plan-Apochrome 10× magnification/0.45-numerical aperture Zeiss objective. A series of projected z-sections taken at 0.35µm intervals throughout the entire thickness of the cell were used for measurements of mitochondrial length using the line measurement function of Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, PA). 15 mitochondria per cell were used for analysis, with 15 neurons in total analyzed for each cell type at each time point (DIV). Data represent the average ± SEM (n=225) for each cell type at each time point described.

Generation of Constructs

Mito-YFP (BD Bioscience), mito-PAGFP (23), Mfn2-YFP (18), GFP-Bax (38), GFP-Bcl-xL (38), GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5, GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5m, GFP-Bax A117P and other chimeras (27) cloning was described previously. GFP-Bax/Bcl-xL H5 was generated by the PCR SOEing method (27), replacing Bax N104-T127 with Bcl-xL V136-K158. FLAG-Mfn2 was cloned using EcoR1 and Xho1 into pCMV-3Tag vector (F: 5’ CGCGA ATTCT CATGG CAGAA CCTGT TTCTC CA; R: 5’ CGCCT CGAGT TAGGA TTCTT CATTG CT). CFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 was cloned using XhoI and EcoRI into the CFP-C1 vector with a template of GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 (27) (F: 5’ ACGTG CTCGA GAATC TCAGA GCAAC CGGGA GCT; R: 5’ ACGTG GAATT CTCAT TTCCG ACTGA AGAGT GAG). The point mutants within Bcl-xL/Bax H5 were created by site mutagenesis using the following primer pairs: (K151A: F: 5’ CCTTT TCTAC TTTGC CAGCG CACTG GTGCT CAAGG CCC; R: 5’ GGGCC TTGAG CACCA GTGCG CTGGC AAAGT AGAAA AGG), (K155E: F: 5’ CCAGC AAACT GGTGC TCGAG GCCCT GTGCA CCAAG; R: 5’ CTTGG TGCAC AGGGC CTCGA GCACC AGTTT GCTGG), (C158D: F: 5’ TGGTG CTCAA GGCCC TGGAC ACCAA GATGC AGGTA TTG; R: 5’ CAATA CCTGC ATCTT GGTGT CCAGG GCCTT GAGCA CCA), and (K160E: F: 5’ TCAAG GCCCT GTGCA CCGAG ATGCA GGTAT TGGTG AG; R: 5’ CTCAC CAATA CCTGC ATCTC GGTGC ACAGG GCCTT GA).

Generation of Bax−/− Bak−/− and EndoB1−/− EndoB2−/− HCT116 cells

Gene targeting via homologous recombination was performed with pSEPT vector according to Topaloglu et al 2005 (39). Exon 4 of Bak was targeted and 8 base pairs of exon 4 were deleted in the targeting allele. Gene targeting was conducted in HCT116 Bax−/− cells to generage Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells and in WT HCT116 cells to generate Bak−/− HCT116 cells. Neomycin (CalBiochem, San Diego; 0.5 mg/ml) was used for selection. After first round targeting, the neomycin selection marker was removed by Ad-Cre (Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia) for the second round of targeting to generate homozygous Bax−/−Bak−/− cells. The same strategy was used to make EndoB1−/− EndoB2−/− HCT116 cells. Exon 2 of both the EndoB1 and EndoB2 genes were targeted via homologous recombination. The same targeting vector for EndoB1 was used in EndoB2−/− cells to generate EndoB1−/−EndoB2−/− cells. The neomycin selection marker was removed by Ad-Cre-GFP in the final homozygous double KO cells.

Supplementary Material

(A) Bax−/− HCT116 cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 and either GFP, GFP-Bax, GFP-Bcl-xL or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and immunoprecipitated with GTP agarase beads. GTP IP and the WCL were analyzed using FLAG and GFP antibodies. (B) HeLa cells transiently expressing FLAG-Mfn2 and GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 were co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG beads. 1× (40 µg) or 15× (600 µg) of IP samples were loaded and 1× (40 µg), 0.5 × (20 µg), 0.25 × (10 µg) or.125 × (5 µg) of WCL samples were loaded. 100% of FLAG-Mfn2 was pulled down and approximately 3% GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 was co-immunoprecipated (GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 15× IP is equivalent to 0.4 × of the WCL, resulting in 2.67%). (C) Clustal W alignment of the H5 region of Bax compared to H5 of Bcl-xL. Point mutation locations are listed. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 and various constructs of GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 containing point mutations within the H5 region. FLAG IP and the WCL were analyzed using FLAG and GFP antibodies. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

(A) WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells transiently expressing Mfn2-YFP were fixed and immunostained for Tom20. (B) WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells were fixed and immunostained for Tom20 and Mfn2. Scale bar represents 5µm. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 or FLAG-Mfn1 and GFP vector, GFP-Bax, GFP-Bcl-xL or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 in a 3:1 ratio of FLAG:GFP. The cells were fixed immunostained for cytochrome c. Scale bar represents 5µm.

(A) HeLa, WT MEF, Mfn2−/− MEF and Mfn1−/− MEF were fixed and immunostained for Mfn2 and cytochrome c. Arrow heads denote regions at tips or junctions of mitochondria containing increased concentration of Mfn2. (B) HeLa cells were fixed and immunostained for Mfn2 and Tom20. Scale bar represents 5µm. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. David Huang and Kym Lowes for the C57BL/6 WT and Bax−/− Bak−/− cells and their comments on the manuscript, Dr. Kuan Hong Wang for his thoughtful reading of the manuscript, Susan Smith for her tissue culture assistance, the NINDS DNA sequencing facility, the NINDS imaging facility and Sungyoung Auh for her assistance with statistical analysis. We would also like to thank Dr. Fred Bunz for the pSEPT vector and advice on gene targeting strategy, Dr. Seung-Wook Ryu for cloning FLAG-Mfn2, Dr. Liqiang Zhang for cloning GFP-Bax/Bcl-xL H5 as well as Dr. Benoit Pierrat for the gift of anti-Endophilin B2. MK thankfully acknowledges financial support from National Institute of General Medical Science (RO1-GM083131). This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program, NINDS, NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hoppins S, Lackner L, Nunnari J. The Machines that Divide and Fuse Mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007 Mar;:15. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.071905.090048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 2003 Jan 20;160(2):189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misaka T, Miyashita T, Kubo Y. Primary structure of a dynamin-related mouse mitochondrial GTPase and its distribution in brain, subcellular localization, and effect on mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem. 2002 May 3;277(18):15834–15842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smirnova E, Griparic L, Shurland DL, van der Bliek AM. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2001 Aug;12(8):2245–2256. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mozdy AD, McCaffery JM, Shaw JM. Dnm1p GTPase-mediated mitochondrial fission is a multi-step process requiring the novel integral membrane component Fis1p. J Cell Biol. 2000 Oct 16;151(2):367–380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gandre-Babbe S, van der Bliek AM. The novel tail-anchored membrane protein Mff controls mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008 Jun;19(6):2402–2412. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suen DF, Norris KL, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2008 Jun 15;22(12):1577–1590. doi: 10.1101/gad.1658508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasilewski M, Scorrano L. The changing shape of mitochondrial apoptosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Aug;20(6):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Robert EG, Catez F, et al. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2001 Oct;1(4):515–525. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neuspiel M, Zunino R, Gangaraju S, Rippstein P, McBride H. Activated mitofusin 2 signals mitochondrial fusion, interferes with Bax activation, and reduces susceptibility to radical induced depolarization. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jul 1;280(26):25060–25070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugioka R, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Fzo1, a protein involved in mitochondrial fusion, inhibits apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004 Dec 10;279(50):52726–52734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi R, Lartigue L, Perkins G, Scott RT, Dixit A, Kushnareva Y, et al. Opa1-mediated cristae opening is Bax/Bak and BH3 dependent, required for apoptosis, and independent of Bak oligomerization. Mol Cell. 2008 Aug 22;31(4):557–569. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frezza C, Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Rudka T, et al. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell. 2006 Jul 14;126(1):177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karbowski M, Norris KL, Cleland MM, Jeong SY, Youle RJ. Role of Bax and Bak in mitochondrial morphogenesis. Nature. 2006 Oct 12;443(7112):658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature05111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delivani P, Adrain C, Taylor RC, Duriez PJ, Martin SJ. Role for CED-9 and Egl-1 as regulators of mitochondrial fission and fusion dynamics. Mol Cell. 2006 Mar 17;21(6):761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu QA, Shio H. Mitochondrial morphogenesis, dendrite development, and synapse formation in cerebellum require both Bcl-w and the glutamate receptor delta2. PLoS Genet. 2008 Jun;4(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000097. e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman SB, Chen YB, Qi B, McCaffery JM, Rucker EB, 3rd, Goebbels S, et al. Bcl-x L increases mitochondrial fission, fusion, and biomass in neurons. J Cell Biol. 2009 Mar 9;184(5):707–719. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karbowski M, Lee YJ, Gaume B, Jeong SY, Frank S, Nechushtan A, et al. Spatial and temporal association of Bax with mitochondrial fission sites, Drp1, and Mfn2 during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002 Dec 23;159(6):931–938. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheridan C, Delivani P, Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Bax- or Bak-induced mitochondrial fission can be uncoupled from cytochrome C release. Mol Cell. 2008 Aug 22;31(4):570–585. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks C, Wei Q, Feng L, Dong G, Tao Y, Mei L, et al. Bak regulates mitochondrial morphology and pathology during apoptosis by interacting with mitofusins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 10;104(28):11649–11654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703976104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James DI, Parone PA, Mattenberger Y, Martinou JC. hFis1, a novel component of the mammalian mitochondrial fission machinery. J Biol Chem. 2003 Sep 19;278(38):36373–36379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Chen Y, Jones AF, Sanger RH, Collis LP, Flannery R, et al. Bcl-xL induces Drp1-dependent synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb 12;105(6):2169–2174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711647105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karbowski M, Arnoult D, Chen H, Chan DC, Smith CL, Youle RJ. Quantitation of mitochondrial dynamics by photolabeling of individual organelles shows that mitochondrial fusion is blocked during the Bax activation phase of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2004 Feb 16;164(4):493–499. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uo T, Kinoshita Y, Morrison RS. Neurons exclusively express N-Bak, a BH3 domain-only Bak isoform that promotes neuronal apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005 Mar 11;280(10):9065–9073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knudson CM, Tung KS, Tourtellotte WG, Brown GA, Korsmeyer SJ. Bax-deficient mice with lymphoid hyperplasia and male germ cell death. Science. 1995 Oct 6;270(5233):96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Yu J, Park BH, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Role of BAX in the apoptotic response to anticancer agents. Science. 2000 Nov 3;290(5493):989–992. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George NM, Evans JJ, Luo X. A three-helix homo-oligomerization domain containing BH3 and BH1 is responsible for the apoptotic activity of Bax. Genes Dev. 2007 Aug 1;21(15):1937–1948. doi: 10.1101/gad.1553607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierrat B, Simonen M, Cueto M, Mestan J, Ferrigno P, Heim J. SH3GLB, a new endophilin-related protein family featuring an SH3 domain. Genomics. 2001 Jan 15;71(2):222–234. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuddeback SM, Yamaguchi H, Komatsu K, Miyashita T, Yamada M, Wu C, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of Bif-1. A novel Src homology 3 domain-containing protein that associates with Bax. J Biol Chem. 2001 Jun 8;276(23):20559–20565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farsad K, Ringstad N, Takei K, Floyd SR, Rose K, De Camilli P. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. J Cell Biol. 2001 Oct 15;155(2):193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karbowski M, Jeong SY, Youle RJ. Endophilin B1 is required for the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology. J Cell Biol. 2004 Sep 27;166(7):1027–1039. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan FJ, Husain M, Manlandro CM, Koppenol M, Fire AZ, Hill RB. CED-9 and mitochondrial homeostasis in C. elegans muscle. J Cell Sci. 2008 Oct 15;121(Pt 20):3373–3382. doi: 10.1242/jcs.032904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rolland SG, Lu Y, David CN, Conradt B. The BCL-2-like protein CED-9 of C. elegans promotes FZO-1/Mfn1,2- and EAT-3/Opa1-dependent mitochondrial fusion. J Cell Biol. 2009 Aug 24;186(4):525–540. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Autret A, Martin SJ. Emerging role for members of the Bcl-2 family in mitochondrial morphogenesis. Mol Cell. 2009 Nov 13;36(3):355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C, Youle RJ. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis*. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:95–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishihara N, Eura Y, Mihara K. Mitofusin 1 and 2 play distinct roles in mitochondrial fusion reactions via GTPase activity. J Cell Sci. 2004 Dec 15;117(Pt 26):6535–6546. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phair RD, Misteli T. High mobility of proteins in the mammalian cell nucleus. Nature. 2000 Apr 6;404(6778):604–609. doi: 10.1038/35007077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolter KG, Hsu YT, Smith CL, Nechushtan A, Xi XG, Youle RJ. Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997 Dec 1;139(5):1281–1292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Topaloglu O, Hurley PJ, Yildirim O, Civin CI, Bunz F. Improved methods for the generation of human gene knockout and knockin cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(18) doi: 10.1093/nar/gni160. e158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Bax−/− HCT116 cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 and either GFP, GFP-Bax, GFP-Bcl-xL or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 and immunoprecipitated with GTP agarase beads. GTP IP and the WCL were analyzed using FLAG and GFP antibodies. (B) HeLa cells transiently expressing FLAG-Mfn2 and GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 were co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG beads. 1× (40 µg) or 15× (600 µg) of IP samples were loaded and 1× (40 µg), 0.5 × (20 µg), 0.25 × (10 µg) or.125 × (5 µg) of WCL samples were loaded. 100% of FLAG-Mfn2 was pulled down and approximately 3% GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 was co-immunoprecipated (GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 15× IP is equivalent to 0.4 × of the WCL, resulting in 2.67%). (C) Clustal W alignment of the H5 region of Bax compared to H5 of Bcl-xL. Point mutation locations are listed. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 and various constructs of GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 containing point mutations within the H5 region. FLAG IP and the WCL were analyzed using FLAG and GFP antibodies. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

(A) WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells transiently expressing Mfn2-YFP were fixed and immunostained for Tom20. (B) WT, Bax−/−, Bak−/− and Bax−/−Bak−/− HCT116 cells were fixed and immunostained for Tom20 and Mfn2. Scale bar represents 5µm. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-Mfn2 or FLAG-Mfn1 and GFP vector, GFP-Bax, GFP-Bcl-xL or GFP-Bcl-xL/Bax H5 in a 3:1 ratio of FLAG:GFP. The cells were fixed immunostained for cytochrome c. Scale bar represents 5µm.

(A) HeLa, WT MEF, Mfn2−/− MEF and Mfn1−/− MEF were fixed and immunostained for Mfn2 and cytochrome c. Arrow heads denote regions at tips or junctions of mitochondria containing increased concentration of Mfn2. (B) HeLa cells were fixed and immunostained for Mfn2 and Tom20. Scale bar represents 5µm. These data are representative of at least two independent experiments.