Abstract

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) are the deadliest of microbial toxins. The enzymes’ Zinc(II) metalloprotease, referred to as the light chain (LC) component, inhibits acetylcholine release into neuromuscular junctions, resulting in the disease botulism. Currently, no therapies counter BoNT poisoning post-neuronal intoxication; however, it is hypothesized that small molecules may be used to inhibit BoNT LC activity in the neuronal cytosol. Herein, we describe the pharmacophore-based design and chemical synthesis of potent (non-Zinc(II) chelating) small molecule (non-peptidic) inhibitors (SMNPIs) of the BoNT serotype A LC (the most toxic of the BoNT serotype LCs). Specifically, the three-dimensional superimpositions of 2-[4-(4-amidinephenoxy)-phenyl]-indole-6-amidine-based SMNPI regioisomers (Ki = 0.600 μM (± 0.100 μM)), with a novel lead bis-[3-amide-5-(imidazolino)-phenyl]-terephthalamide (BAIPT)-based SMNPI (Ki = 8.52 μM (± 0.53 μM)), resulted in a refined 4-zone pharmacophore. The refined model guided the design of BAIPT-based SMNPIs possessing Ki values = 0.572 μM (± 0.041 μM) and 0.900 μM (± 0.078 μM).

Keywords: botulinum neurotoxin, small molecule inhibitor, gas-phase pharmacophore, rational design, biothreat agent

Botulinum Neurotoxins (BoNTs) are the deadliest of known microbial toxins1; for example, it is estimated that a lethal BoNT dose (LD50) for Homo sapiens is 1 ng kg−1 body mass.1 As a result, these enzymes are classified as category A, highest priority biothreat agents by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.2

Secreted by strains of anaerobic bacillus Clostridium botulinum,1 there are seven known BoNT serotypes (designated A – G). Serotypes A, B, C, E, and F cause human botulism.3, 4 The mechanism of BoNT neuronal intoxication can be summarized as follows1: 1) post-proteolytic activation, the enzyme consists of a disulfide-linked 100 kDa heavy chain (HC) and a 50 kDa light chain (LC), 2) the HC binds to neuronal cell surface receptors, triggering toxin internalization via an intracellular vesicle, 3) the HC mediates LC translocation out of the intracellular vesicle into the neuronal cytosol, and 4) the LC (a Zinc (Zn)(II) metalloprotease) cleaves, depending on the serotype, one of three proteins (see below) composing the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex. The SNARE complex negotiates the release of acetylcholine-containing synaptic vesicles into neuromuscular junctions. The toxin-induced inhibition of acetylcholine release, via the proteolysis of SNARE proteins, terminates neuron-to-muscle signaling, resulting in the life-threatening flaccid paralysis associated with botulism. The BoNT serotype A, E, and C LCs cleave synaptosomal associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25),1 the BoNT serotype C LC also cleaves syntaxin,1 and the BoNT serotype B, D, F and G LCs cleave vesicle-associated membrane protein.1

Currently, there are no therapies available for the treatment of BoNT LC-mediated paralysis post-neuronal intoxication. This is pivotal, as the current treatments for BoNT poisoning are limited to: 1) the administration of antitoxin(s),1, 5 which is/are not effective post-neuronal intoxication,6 and therefore would be of limited use following an act of bioterror (as it is likely that victims would seek medical attention only after enervation) and 2) mechanical ventilation, which is necessary once BoNT-induced paralysis compromises thoracic muscle contraction 5. However, the latter form of treatment would also be impractical following even a limited act of bioterror employing a BoNT(s), as critical care resources would likely be overwhelmed.7 Hence, there is considerable interest in discovering and developing small molecules as therapeutics to inhibit BoNT LC proteolytic activity post-neuronal intoxication.1, 8, 9 Moreover, with respect to the development of small molecule therapeutics, the BoNT serotype A LC (BoNT/A LC) represents a top priority, as it, versus other BoNT LCs known to cause botulism in humans, possesses the longest duration of activity in the neuronal cytosol.3, 4 Thus, the hypothesis rationalizing a small molecule-based therapeutic approach for the treatment of BoNT/A LC intoxication: small, drug-like molecules can penetrate into the neuronal cytosol 10 and inhibit the toxin’s LC proteolytic activity post-neuronal intoxication. In turn, this mechanism would protect SNAP-25, and hence the function of the SNARE protein complex. Additionally, if stockpiled in dry, sunlight-free, temperature-controlled locations, chemically stable small molecules would remain viable for many years. In contrast, vaccines possess comparatively shorter shelf-lives.

Current X-ray structures of the BoNT/A LC fail to rationalize the structure-activity relationships (SAR) for our competitive, non-Zn(II) chelating, small molecule (non-peptidic) inhibitors (SMNPIs) of the BoNT/A LC.10–12 For this reason, we are successfully employing a gas-phase pharmacophore-based approach for SMNPI discovery and optimization.11, 12 This paradigm uses an efficient, iterative approach: SMNPIs are continually integrated into the pharmacophore to both develop three-dimensional (3-D) search queries to discover novel SMNPI chemotypes (via the 3-D database mining of small molecule libraries), and to guide the rational design of more potent SMNPI derivatives. Following, structure-activity data from both database mined and rationally designed SMNPIs are incorporated back into the model, resulting in further pharmacophore refinement.10–13

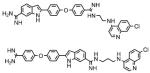

Employing this strategy, we recently reported a 3-zone iteration of the pharmacophore for BoNT/A LC inhibition 11 that guided the design of 2-[4-(4-amidinephenoxy)-phenyl]-indole-6-amidine (2,4,4-APPIA)-based SMNPI regioisomers 1a and 1b (Table 1).11 In vitro testing of 1a and 1b indicated that the regioisomers possess a Ki = 0.600 μM (± 0.100 μM). However, it is important to note that the substituted bis-amidine moieties of 1a and 1b are not chemically stable during HPLC separation, which prohibits regioisomer isolation. Additionally, the selective syntheses of individual regioisomers 1a and 1b is also prohibitive, and therefore we are currently exploring alternative cationic moieties to further advance the development and the optimization of this chemotype. Furthermore, we have reported how the 3-zone pharmacophore was employed to generate a 3-D search query that identified novel bis-[3-amide-5-(imidazolino)-phenyl]-terephthalamide (BAIPT)-based SMNPI 2 (Table 1),12 a lead inhibitor possessing a Ki = 8.52 μM (± 0.53 μM). The discovery of 2 was particularly compelling because one of its bis-butylamide substituents is located outside of the 3-zone iteration of the pharmacophore,12 implying the possibility of a fourth zone of SMNPI occupancy (Figure 1a). Importantly, a new pharmacophore zone-4 could potentially be exploited to discover new SMNPI chemotypes, as well as guide the synthetic optimization of our known SMNPIs.

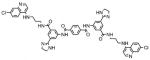

Table 1.

SMNPI two-dimensional structures and inhibition constants.

| SMNPI | STRUCTURE & Ki Value |

|---|---|

| 1a & 1b |

Ki = 0.600μM (+/− 0.100μM)11a |

| 2 |

Ki = 8.52μM (+/− 0.53μM) |

| 3 |

Ki = 2.12μM (+/− 0.26μM) |

| 4 |

Ki = 0.572μM (+/− 0.041μM) |

| 5 |

Ki = 0.900μM (+/− 0.078μM) |

published Ki value (Ref 11)

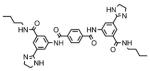

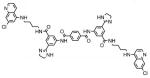

Figure 1.

SMNPI alignments in a previously reported 3-zone iteration of the pharmacophore for BoNT/A LC inhibition.11, 12 Chlorine atoms are light green, nitrogen atoms are blue, and oxygen atoms are red. Squares indicate planar pharmacophore components and dashed spheres indicate cationic pharmacophore components. (a) SMNPI 2 (magenta carbons) as it was previously predicted to fit within the 3-zone iteration of the pharmacophore.12 (b) SMNPI regioisomers 1a (green carbons) and 1b (cyan carbons) were previously predicted to fit the 3-zone pharmacophore such that their ‘core’ 2,4,4-APPIA components oriented in opposite directions within zones-1 and -2, and as a result, their 4,7-ACQ substructures occupied only zone-3.11

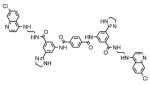

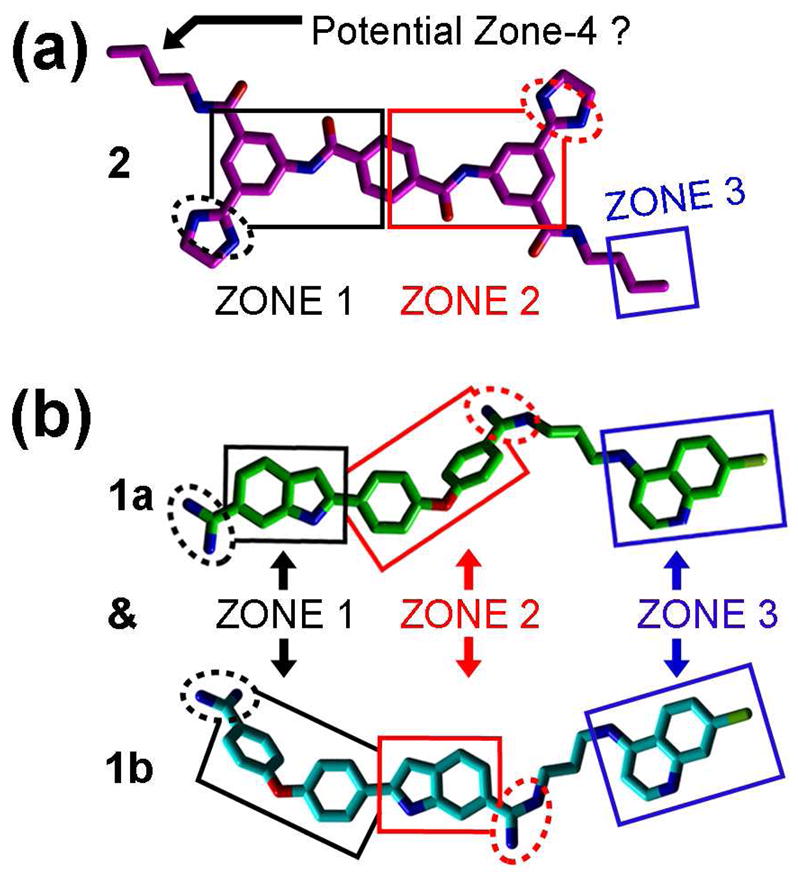

To initially examine the possibility of a 4-zone pharmacophore, sterically feasible intramolecular conformations of 1a, 1b, and 2 were superimposed in gas-phase. As shown in Figure 2a, the SMNPIs overlaid with good chemical complementarity. Of particular significance to pharmacophore refinement, the 4-amino-7-chloroquinoline (4,7-ACQ) components of 1a and 1b, and the terminal methylenes of the butylamide substituents of 2, can occupy proximal locations within empirically verified zone-3,11 and hypothesized pharmacophore zone-4, respectively (Figure 2a) (with the 4,7-ACQ components providing greater zonal occupancy). Additionally, with respect to model refinement, the new SMNPI superimpositions are in contrast to our previously published 3-zone pharmacophore,11 which predicted that the 4,7-ACQ components of 1a and 1b occupy only zone-3 of this model (Figure 1b).

Figure 2.

3-D alignments of SMNPIs 1a, 1b, and 2 in the context of the refined 4-zone pharmacophore for BoNT/A LC inhibition, and rational designs based on the new model. (a) all colors and shape definitions are as indicated in Figure 1. (b) carbon atoms are yellow, orange, and burgundy for designs 3, 4, and 5, respectively; all other atom colors are as indicated in Figure 1.

Further supporting a 4-zone pharmacophore model are the superimpositions of the SMNPIs’ within the requirements of reported zones-1 and -2 (Figure 2a).11, 12 Specially, in zone-1 (Figure 2a): 1) the cationic amidines of 1a and 1b and the cationic imidazoline of 2 are located in close proximity and possess comparable directional orientations, 2) the hydrogen bond donating indole nitrogens of 1a and 1b superimpose with a hydrogen bond donating amide nitrogen of the ‘core’ terephthalamide of 2, 3) the phenyl components of the indoles of 1a and 1b align closely with the zone-1-occupying phenyl of 2, and 4) the central phenyls of 1a and 1b superimpose with the terephthalamide phenyl of 2. It is notable that in the refined 4-zone pharmacophore (Figure 2a), versus the 3-zone iteration of the model (Figure 1), the central phenyl rings of 1a, 1b, and 2 form the key basis for SMNPI alignment, and therefore are now included within the zone-1 planar component (reference Figure 1 versus Figure 2a).

In zone 2 (Figure 2a): 1) the ether oxygens of 1a and 1b superimpose with, and are oriented in the same direction as, a terephthalamide carbonyl oxygen of 2, 2) the terminal phenyls of 1a and 1b are located proximal to, and partially overlay with, the zone-2-occupying phenyl of 2, and 3) the cationic amidines of 1a and 1b and the cationic imidazole of 2 align in good order and with equivalent directional orientations.

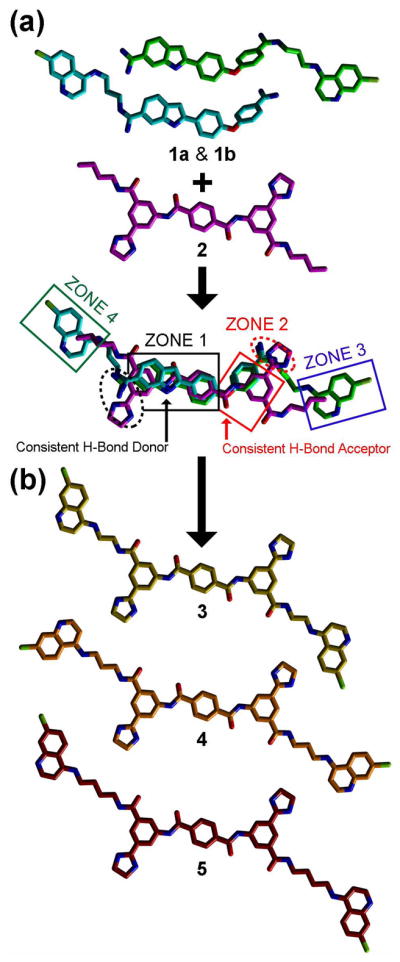

The 3-D chemical complementarity observed for 1a, 1b, and 2, when aligned in the 4-zone pharmacophore (Figure 2a), formed the basis for the design of derivatives to improve the inhibitory potency of the BAIPT-based SMNPI chemotype. Specifically, the 4-zone pharmacophore indicated that tethering 4,7-ACQ substructures onto the terminal amide amines of the BAIPT chemotype ‘core’ with alkyl linkers (see derivatives 3 – 5, Figure 2b), would result in SMNPIs with improved inhibitory potencies. Additionally, as shown in Figure 2b, 3 – 5 were designed to provide SAR exploring the lengths of the alkyl chains (i.e., ethyls (3), propyls (4), and butyls (5)) tethering the 4,7-ACQ zone-3 and -4 occupying components to the terminal amide amines of the BAIPT chemotype ‘core.’

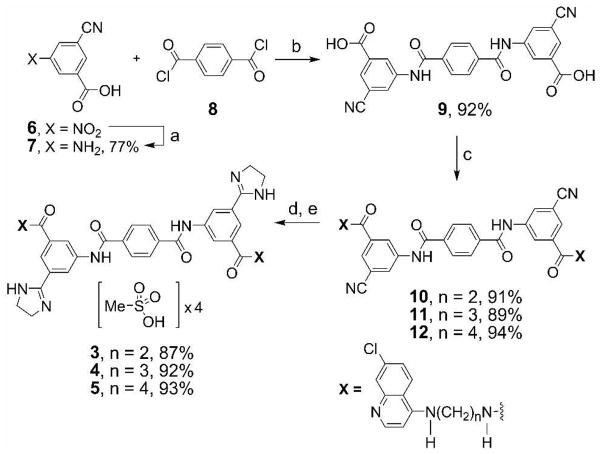

Scheme 1 displays the general synthetic procedure used to prepare 3 – 5. Generation of the target compounds began with repeated attempts to reduce 3-cyano-5-nitrobenzoic acid (6) to corresponding aniline 7 via catalytic hydrogenation; however, substantial quantities of incomplete reduction products were constantly observed. To circumvent this obstacle, hydrogen transfer, rather than catalytic hydrogenation, was used to successfully generate 7 in 77% yield after acidification with formic acid and crystallization from water. Following, 7 and 8 were coupled using a modified procedure reported by Sellarajah et al.14 to afford key intermediate 9 in 92% yield after quenching with water and crystallization from acetonitrile. Next, amide bond formation between 9 and the corresponding aminoquinolines15 was performed at r.t. using HOBt and EDCl in DMA solvent to provide dinitrile intermediates 10 – 12, respectively. The transformation of 10 – 12 into corresponding imidazoline targets 3 – 5 was achieved via reaction with ethylenediamine and NaSH in DMA solvent at 120 °C, employing a modified procedure of Sun et al.16 Finally, the salts of 3 – 5 were obtained by stirring with methanesulfonic acid in acetonitrile at 70 °C. Detailed synthetic procedures and compound characterizations are provided as Supporting Information.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of BAIPT-based SMNPIs 3 – 5.

Reagents and conditions: (a) ammonium formate, 10% Pd-C, H2O, 90 °C, 21 h, then HCOOH; (b) DMAP, DMA, rt, 48 h; (c) N1-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)-ethane-1,2-diamine (to provide 10), N1-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)-propane-1,3-diamine (to provide 11), N1-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)-butane-1,4-diamine (to provide 12), HOBt, EDCl, DMA, rt, 24 h; (d) ethylene diamine, NaSH, DMA, 120 °C, 2 h; (e) methanesulfonic acid, CH3CN, 70 °C, 0.5 h.

The Ki values for 3 – 5 (Table 1) were determined using a well documented HPLC-based assay.17–22 The 4-zone pharmacophore-based designs were all more potent than 2 (Ki = 8.52 μM (± 0.53 μM). Specifically, 3 – 5 possess Ki values of 2.12 μM (± 0.26 μM), 0.572 μM (± 0.041 μM), and 0.900 μM (± 0.078 μM), respectively (Table 1). Furthermore, plots of the inhibition kinetics data for 3 – 5 indicate that all are competitive inhibitors (Supporting Information, Figures S1 – S3), and additional in vitro analyses of the SMNPIs in the presence of Zn(II) concentrations equaling 5 μM, 10 μM, 25 μM, and 50 μM did not effect inhibitory efficacies (Supporting Information, Table S1), thereby indicating that the SMNPI’s do not chelate the Zn(II) of the enzyme’s catalytic engine. The in vitro results obtained for 3 – 5 (Table 1) confirm the presence of pharmacophore zone-4. Moreover, the increased inhibitory potencies of 3 – 5, versus 2 , demonstrate that, with each refinement of the gas-phase pharmacophore, the model’s predictive resolution is improved and that it can be used to design more potent SMNPIs.

Based on the SAR provided by 3 – 5, the inhibitory potency of 4 implies that the optimal length of the alkyl tether connecting SMNPI components is a propyl chain. By contrast, the inhibitory potency of 3 indicates that shorter ethyl tethers do not allow the SMNPI’s 4,7-ACQ moieties to achieve optimal zone-3 and -4 occupancy; while the inhibitory potency of 5 indicates that longer butyl tethers overextend optimal 4,7-ACQ binding in zones-3 and -4. To provide SAR that will further guide SMNPI optimization (in vitro), future BAIPT-based designs will explore not only the effects of modified tethers (e.g., linkers with increased rigidity and the inclusion of heteroatoms) on BoNT/A LC inhibition, but will also incorporate a diversity of zone-3 and zone-4 occupying components (e.g., indoles, phenyls, pyridines, etc.). Furthermore, future studies will also be conducted to examine BAIPT-based SMNPI SNAP-25 protection and toxicity in neurons.

In summary, our gas phase pharmacophore for BoNT/A LC inhibition is constantly enabling the rational design of more potent SMNPIs. In the current study, a refined 4-zone iteration of the model was generated via the 3-D superimposition of two different SMNPI chemotypes. To empirically validate the refined model, three target compounds based on the BAIPT chemotype ‘core’ were synthesized and examined in vitro. Of the three designs, all are more potent than parent compound 2, while 4 is the most potent non-Zn(II) chelating, non-hydroxamic acid containing, SMNPI of the BoNT/A LC reported to date. Moreover, comparison of the inhibitory potencies of 1a, 1b , and 4 indicates that a propyl tether may be optimal for accessing pharmacophore zones-3 and -4 with an aromatic moiety. In general, the refined pharmacophore model forms the basis for increasing the activities of our non-Zn(II) chelating SMNPI chemotypes. Future 4-zone pharmacophore-based designs will focus on developing SAR to provide strategies for optimizing the chemical and steric compositions of SMNPI components populating zones-3 and -4 (e.g., the 4,7-ACQ components of 1a, 1b, and 3 – 5), as well as the flexibility/rigidity and composition of the tethers linking zones-1 and -4 and zones-2 and -3 (e.g., the propyl linkers of 4).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The presented research was supported by Defense Threat Reduction Agency project 3.10084_09_RD_B (and also Agreement Y3CM 100505 (MRMC and NCI, National Institutes of Health) for JCB).

Furthermore, for JCB, in accordance with SAIC-Frederick, Inc. contractual requirements: this project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. overnment or the U.S. Army.

NONSTANDARD ABBREVIATIONS

- 4,7-ACQ

4-amino-7-chloroquinoline

- 2-4,4-APPIA

2-[4-(4-amidinephenoxy)-phenyl]-indole-6-amidine

- BAIPT

bis-[3-amide-5-(imidazolino)-phenyl]-terephthalamide

- BoNT/A LC

botulinum neurotoxin serotype A light chain

- SMNPI

small molecule (non-peptidic) inhibitor

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Descriptions of: 1) molecular modeling techniques employed for pharmacophore refinement, 2) general chemistry methods, 3) experimental details for the syntheses and characterization of 3 - 5, 7, and 9 – 12, and 4) inhibition assay conditions and Ki value determination. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Willis B, Eubanks LM, Dickerson TJ, Janda KD. The Strange Case of the Botulinum Neurotoxin: Using Chemistry and Biology to Modulate the Most Deadly Poison. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:8360–8379. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.<http://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist-category.asp>.

- 3.Foran PG, Davletov B, Meunier FA. Getting Muscles Moving Again After Botulinum Toxin: Novel Therapeutic Challenges. Trends Mol Med. 2003;9:291–299. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(03)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foran PG, Mohammed N, Lisk GO, Nagwaney S, Lawrence GW, Johnson E, Smith L, Aoki KR, Dolly JO. Evaluation of the Therapeutic Usefulness of Botulinum Neurotoxin B, C1, E, and F Compared with the Long Lasting Type A. Basis for Distinct Durations of Inhibition of Exocytosis in Central Neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1363–1371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Hauer J, Layton M, Lillibridge S, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Swerdlow DL, Tonat K. Botulinum Toxin as a Biological Weapon: Medical and Public Health Management. JAMA. 2001;285:1059–1070. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith TJ, Lou J, Geren IN, Forsyth CM, Tsai R, Laporte SL, Tepp WH, Bradshaw M, Johnson EA, Smith LA, Marks JD. Sequence Variation within Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotypes Impacts Antibody Binding and Neutralization. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5450–5457. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5450-5457.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wein LM, Liu Y. Analyzing a Bioterror Attack on the Food Supply: the Case of Botulinum Toxin in Milk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9984–9989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408526102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai S, Singh BR. Strategies to Design Inhibitors of Clostridium Botulinum Neurotoxins. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:47–57. doi: 10.2174/187152607780090667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capkova K, Salzameda NT, Janda KD. Investigations into Small Molecule Non-Peptidic Inhibitors of the Botulinum Neurotoxins. Toxicon. 2009;54:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnett JC, Ruthel G, Stegmann CM, Panchal RG, Nguyen TL, Hermone AR, Stafford RG, Lane DJ, Kenny TA, McGrath CF, Wipf P, Stahl AM, Schmidt JJ, Gussio R, Brunger AT, Bavari S. Inhibition of Metalloprotease Botulinum Serotype A: from a Pseudo-Peptide Binding Mode to a Small Molecule that is Active in Primary Neurons. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5004–5014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnett JC, Wang C, Nuss JE, Nguyen TL, Hermone AR, Schmidt JJ, Gussio R, Wipf P, Bavari S. Pharmacophore-Guided Lead Optimization: the Rational Design of a Non-Zinc Coordinating, Sub-Micromolar Inhibitor of the Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype a Metalloprotease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:5811–5813. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermone AR, Burnett JC, Nuss JE, Tressler LE, Nguyen TL, Solaja BA, Vennerstrom JL, Schmidt JJ, Wipf P, Bavari S, Gussio R. Three-Dimensional Database Mining Identifies a Unique Chemotype that Unites Structurally Diverse Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype A Inhibitors in a Three-Zone Pharmacophore. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:1905–1912. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnett JC, Opsenica D, Sriraghavan K, Panchal RG, Ruthel G, Hermone AR, Nguyen TL, Kenny TA, Lane DJ, McGrath CF, Schmidt JJ, Vennerstrom JL, Gussio R, Solaja BA, Bavari S. A Refined Pharmacophore Identifies Potent 4-Amino-7-Chloroquinoline-Based Inhibitors of the Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype A Metalloprotease. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2127–2136. doi: 10.1021/jm061446e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sellarajah S, Lekishvili T, Bowring C, Thompsett AR, Rudyk H, Birkett CR, Brown DR, Gilbert IH. Synthesis of Analogues of Congo Red and Evaluation of Their Anti-Prion Activity. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5515–5534. doi: 10.1021/jm049922t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natarajan JK, Alumasa JN, Yearick K, Ekoue-Kovi KA, Casabianca LB, de Dios AC, Wolf C, Roepe PD. 4-N-, 4-S-, and 4-O-Chloroquine Analogues: Influence of Side Chain Length and Quinolyl Nitrogen pKa on Activity Versus Chloroquine Resistant Malaria. J Med Chem. 2008;51:3466–3479. doi: 10.1021/jm701478a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun M, Wei HT, Li D, Zheng YG, Cai J, Ji M. Mild and Efficient One-Pot Synthesis of 2-Imidazolines from Nitriles Using Sodium Hydrosulfide as Catalyst. Synth Comm. 2008;38:3151–3158. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt JJ, Bostian KA. Endoproteinase Activity of Type A Botulinum Neurotoxin: Substrate Requirements and Activation by Serum Albumin. J Protein Chem. 1997;16:19–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1026386710428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt JJ, Bostian KA. Proteolysis of Synthetic Peptides by Type A Botulinum Neurotoxin. J Protein Chem. 1995;14:703–708. doi: 10.1007/BF01886909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt JJ, Stafford RG. Fluorigenic Substrates for the Protease Activities of Botulinum Neurotoxins, Serotypes A, B, and F. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:297–303. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.297-303.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt JJ, Stafford RG. A High-Affinity Competitive Inhibitor of Type A Botulinum Neurotoxin Protease Activity. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:423–426. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03738-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt JJ, Stafford RG, Bostian KA. Type A Botulinum Neurotoxin Proteolytic Activity: Development of Competitive Inhibitors and Implications for Substrate Specificity at the S1' Binding Subsite. FEBS Lett. 1998;435:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt JJ, Stafford RG, Millard CB. High-Throughput Assays for Botulinum Neurotoxin Proteolytic Activity: Serotypes A, B, D, and F. Anal Biochem. 2001;296:130–137. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.