Abstract

Structural modifications to the coumarin core and benzamide side chain of novobiocin have successfully transformed the natural product from a selective DNA gyrase inhibitor into a potent inhibitor of the Hsp90 C-terminus. However, no SAR studies have been conducted on the noviose appendage, which represents the rate-limiting synthon in the preparation of analogues. Therefore, a series of sugar mimics and non-sugar derivatives were synthesized and evaluated to identify simplified compounds that exhibit Hsp90 inhibition. Evaluation against two breast cancer cell lines demonstrated that replacement of the stereochemical complex noviose with simplified alkyl amines increased anti-proliferative activity, resulting in novobiocin analogues that manifest IC50 values in the mid nanomolar range.

Keywords: Heat shock protein 90, Hsp90 inhibitors, Novobiocin, Stucture-activity relationships, Breast cancer

The 90 kDa heat shock proteins (Hsp90) are responsible for the conformational maturation of more than 200 Hsp90-dependent client proteins,1,2 of which, Her2, Src family kinases, Raf, PLK, RIP, AKT, telomerase and Met are directly associated with the six hallmarks of cancer.3,4 Consequently, inhibition of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery simultaneously disrupts multiple oncogenic pathways, leading to cell death.5,6 Since the first proof-of-concept drug, 17-AAG (a synthetic analogue of geldanamycin), entered clinic trials and demonstrated therapeutic benefit at tolerable doses,7 extensive research has led to more than 20 subsequent clinic trials,8 highlighting Hsp90 as a promising therapeutic target for the development of anti-cancer agents.9–11

Novobiocin, a natural product comprised of a noviose sugar, a coumarin core and a prenylated benzamide side chain, is isolated from streptomyces strains12 and is known to exhibit antimicrobial activity by binding to the DNA gyrase ATP-binding pocket,13 a unique nucleotide-binding motif shared only by members of the GHKL superfamily.14 Due to the similar bent conformation exhibited by ADP bound to both DNA gyrase and the Hsp90 N-terminal domain, Neckers and co-workers hypothesized that novobiocin may manifest anti-cancer activity through Hsp90 inhibition.15 Their pioneering studies revealed novobiocin to bind Hsp90, but instead of binding to the well-recognized N-terminal domain, it bound to a previously unrecognized C-terminal region, albeit with low efficiency (~700 μM in SKBr3 cells).15 Since this study, structural modifications of novobiocin have been pursued to identify molecules that exhibit increased inhibitory activity.16–22

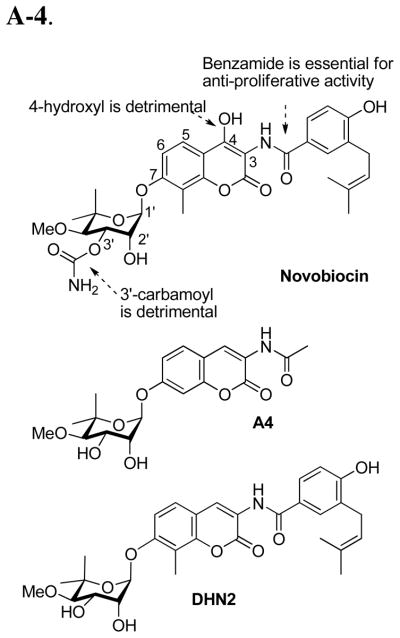

The first library of such compounds was designed and synthesized by Yu and co-workers to identify functionalities necessary for Hsp90 inhibition on the coumarin ring and benzamide side chain of novobiocin17. Their studies revealed that attachment of the noviose appendage to the 7-position of the coumarin ring and an amide linker at the 3-position are critical, while the 4-hydroxy substituent and the 3′-carbamoyl are detrimental. The most efficacious compound identified from this library was compound A4, which induced degradation of Hsp90-dependent client proteins at ~70-fold lower concentration than novobiocin. Intriguingly, compound A4 induced the heat shock response at concentrations ~1000-fold lower than that required for client protein degradation.23,24

To confirm SAR trends observed by Yu and co-workers conformed to the natural product, DHN2 was synthesized to delineate functionalities responsible for DNA gyrase versus Hsp90 inhibition.18 This novobiocin analogue confirmed that the 4-hydroxyl and the 3′-carbamate are detrimental to Hsp90 inhibitory activity, but critical for DNA gyrase inhibition, thus confirming the SAR trends observed for A-4.

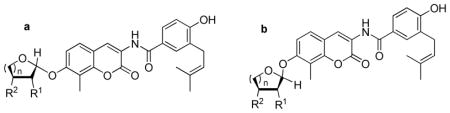

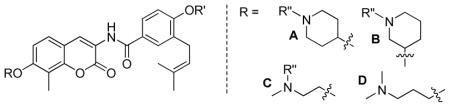

Subsequent structural modifications and SAR studies explored the coumarin ring and benzamide side chain, and several lead-like compounds were identified and remain under investigation.19,21,22 As shown in Figure 1, the analogues prepared thus far retain the noviose appendage. However, the synthesis of noviose is laborious and hinders analogue development; as it requires more than ten steps to prepare and activate for subsequent coupling with the coumarin phenol.25,26 Acknowledging the limited SAR for this moiety and its cumbersome preparation, simplified analogues were pursued in an effort to increase activity while simultaneously increasing solubility. In this article, we provide the first biologically-active substitutions for the noviose appendage on novobiocin and the first nonsugar mimics that exhibit increased anti-proliferative activity.

Figure 1.

SAR generated from previous investigations.

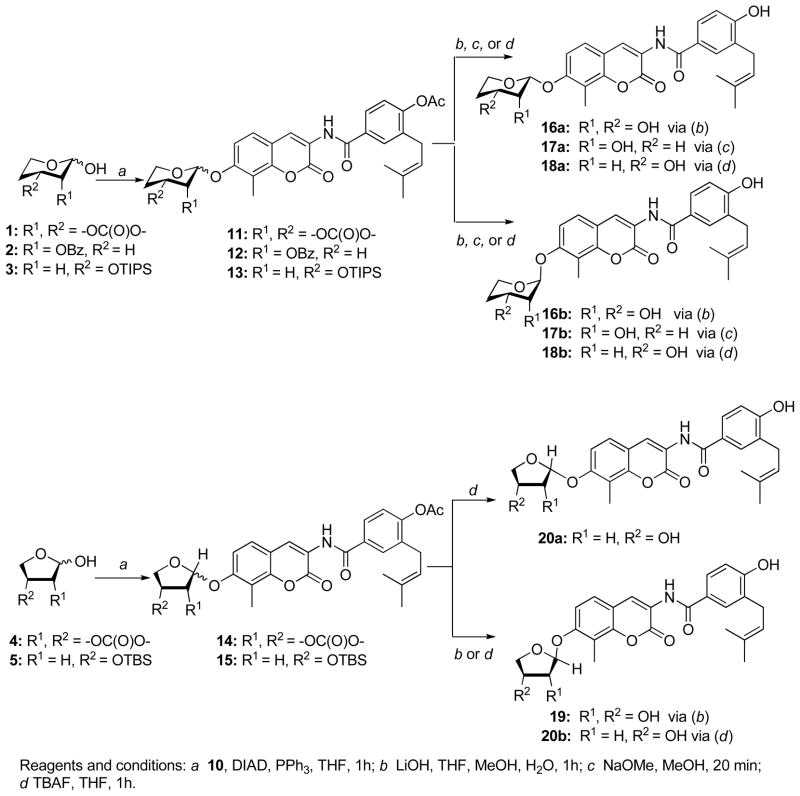

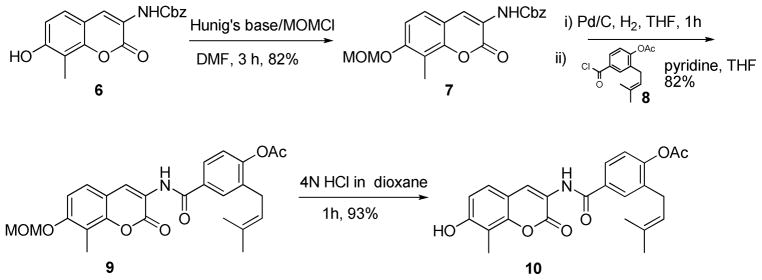

It is well understood that sugar moieties in natural products play a key role in solubility, activity and bioavailability for these compounds. Furthermore, the ring size can impart significant affinity towards their cognate protein. With these considerations in mind, a series of mono- and di-hydroxylated furanose and pyranose sugars (1–5, Scheme 2) were synthesized according to previously disclosed procedures26 for incorporation onto the novobiocin scaffold 10. The preparation of 10 is described in Scheme 1. The coumarin phenol 6 was converted to the methoxymethyl (MOM) ether using methoxymethyl chloride and Hunig’s base in Dimethylformamide. The free aniline, liberated through hydrogenolysis with 10% Pd/C and hydrogen in tetrahydrofuran from 7, was coupled with acid chloride 8 to give benzamide 9. Subsequent cleavage of the methoxymethyl ether with 4N hydrochloride in dioxane provided phenol 10 in high yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of novobiocin analogues containing mono- and di-hydroxylated furanoses and pyranoses.

Reagents and conditions: a 10, DIAD, PPh3, THF, 1h; b LiOH, THF, MeOH, H2O, 1h; c NaOMe, MeOH, 20 min; d TBAF, THF, 1h.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of coumarin phenol 10.

Once prepared, the phenol of 10 was coupled with sugars 1–5 under Mitsunobu conditions to give an inseparable diastereomeric mixture of 11–13 and 15 (Scheme 2). In the case of compound 14, a single diastereomer was formed. Subsequent hydrolysis of the cyclic carbonates and acetyl esters of 11a–b and 14 with lithium hydroxide in THF/MeOH/H2O (3:2:2, v/v) afforded a diastereomeric mixture of 16a–b and 19, respectively. At this stage, diastereomers 16a and 16b were separated by silica chromatography. The assignment of stereochemistry at the anomeric center was established through two-dimensional NMR studies utilizing NOESY. Similarly, hydrolysis of the benzoyl and acetyl ester of 12 with basic methanol yielded 17a and 17b, which could be separated by silica chromatography. The tri-isopropylsilyl (TIPS) of 13 and tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) groups of 15 were removed by the addition of tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) to give separable 18a and 18b; and 20a and 20b, respectively.

Upon construction of the noviose surrogates, compounds were subjected to evaluation by determination of anti-proliferative activity against SKBr3 (estrogen receptor negative, Her2 over-expressing breast cancer cells) and MCF-7 (estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells) cell lines. As shown in Table 1, the six-membered sugar mimics (16a–18a and 16b–18b) were found to be more potent than their five-membered counterparts (19, 20a–b). Compound 18b displayed an IC50 value of 3.11±0.03μM and 1.56±0.20 against SKBr3 and MCF-7 cell lines respectively, which is ~3–8-fold more active than DHN2 (Table 1) and ~200 times greater than the activity manifested by novobiocin. Surprisingly, the stereochemistry of these sugar mimics was not critical for the observed increase in anti-proliferative activity, as both the α-(16b) and β-anomers (17a) produced similar activities. Placement of the hydroxyl group (3′-OH or 4′-OH) on the etheral ring also did not impart preferential activity.

Table 1.

Anti-proliferation activities of sugar derived novobiocin analogues

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | n | R2 | R1 | SKBr3 (μM) | MCF7 (μM) |

| 16a | 2 | OH | OH | 10.68±0.05 | 10.04±0.03 |

| 16b | 2 | OH | OH | 6.96±0.06 | 13.30±0.21 |

| 17a | 2 | H | OH | 7.87±0.04 | 6.45±0.13 |

| 17b | 2 | H | OH | 29.98±2.07 | 10.24±0.21 |

| 18a | 2 | OH | H | 5.07±0.26 | 1.34±0.18 |

| 18b | 2 | OH | H | 3.11±0.03 | 1.56±0.20 |

| 19 | 1 | OH | OH | 14.37±0.52 | 14.31±0.40 |

| 20a | 1 | OH | H | 22.16±0.94 | >100 |

| 20b | 1 | OH | H | 21.46±2.28 | 22.50±0.40 |

| DHN2 | -- | -- | -- | 10.86±0.47 | 11.29±0.41 |

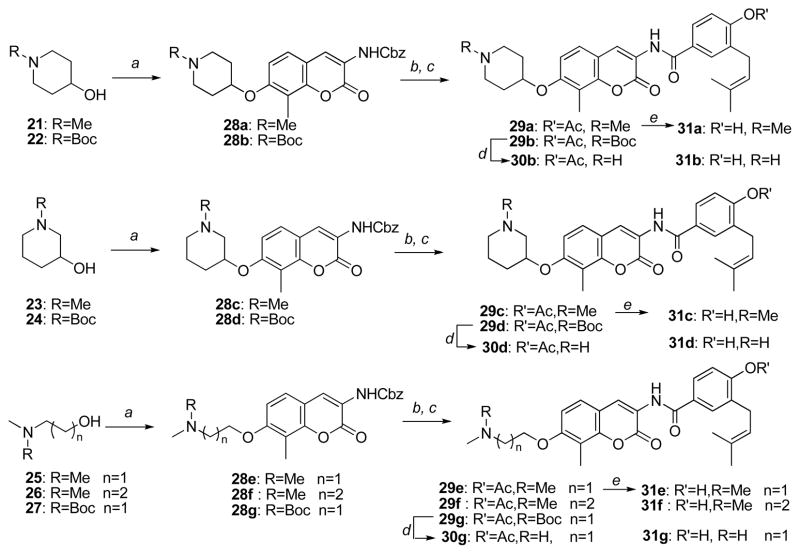

Although simplified sugar mimics were found to increase anti-proliferative activity compared to DHN2 and novobiocin, more simplified analogues exhibiting enhanced solubility and activity were desired. N-Heterocycles are found in a variety of biologically active compounds, and in contrast to carbohydrates, are generally ionized at physiological pH.27 Upon review of the first set of studies, we proposed that the noviose appendage played a siginficant role in solublizing the relatively hydrophobic coumarin core and benzamide side chain. Thus, commercially available amines, 21–27 (Scheme 3, secondary amines were protected with Boc), were selected as potential replacements for the noviose moiety. These alkylamines and heterocyclic analogues contain an ionizable amine located at various positions within the structure to afford potential hydrogen-bonding interactions while simultaneously enhancing solubility through their ionized counterparts.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of amine analogues.

Reagents and Conditions: a. 6, PPh3, DIAD, THF b. H2,10% Pd/C c. 8, Pyridine, THF d. 10% TFA/CH2Cl2 e. 10% Et3N/MeOH

Originally, coupling of these amines with phenol 10 was expected to easily afford the desired products. However, the acetyl ester on the benzamide side chain was hydrolyzed under these conditions and resulted in an inseparable mixture of mono- or dialkylated products. To circumvent this issue, the amine was first coupled with the coumarin ring and subsequently with the benzamide side chain to afford the desired analogues. The detailed synthesis is described as follows: Tertiary amines or Boc-masked secondary amines were reacted with Cbz-protected coumarin 6 in the presence of two equivalents of triphenylphosphine and diisopropylazodicarboxylate in tetrahydrofuran to give amine-derived coumarins, 28a–28g. The Cbz-protecting group was removed by hydrogenolysis to give the free amines, which were then coupled with acid chloride 8 to give compounds 29a–29g in good yield. Removal of the Boc protecting group with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in methylene chloride afforded the secondary amine analogues 30b, 30d and 30g. Hydrolysis of the phenolic ester with methanolic triethyl amine gave analogues, 31a–31g, in good to excellent yields.

Anti-proliferative activity manifested by these analogues was assessed against SKBr3 and MCF-7 cell lines. As shown in Table 2, the IC50 values for the secondary and tertiary amines varied between 0.4–1.5 μM, making them 1500-fold more potent than novobiocin. Generally, the ester series exhibited comparable anti-proliferative activity to their phenol counterparts, suggesting the ester analogues may rapidly hydrolyze in cells due to esterases. In regards to the piperidine analogues, 4-substituted analogues exhibited greater potency than the 3-substituted analogues against both cell lines. For example, against the SKBr3 cell line, compound 29a is ~3-fold more active than compound 29c and compound 30b and 31b is ~2 times more active than compound 30d and 31d, respectively. The same trend was observed for the noncyclic amino analogues as well (29f vs 29e, 31f vs 31e). These results indicate that the location of the amine is important for binding/manifesting inhibiting activity. A surprising finding of this work was that analogues containing noncyclic amines exhibit equivalent potencies to their piperidine counterparts, specifically, 29a and 29f, 31a and 31f, indicating that inclusion of a ring structure is not required.

Table 2.

Anti-proliferative activities of amine analogues.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | R′ | R″ | SKBr3 (μM) | MCF-7 (μM) |

| 29a | A | Ac | Me | 0.58±0.05 | 1.18±0.20 |

| 29c | B | Ac | Me | 1.42±0.02 | 1.57±0.05 |

| 29e | C | Ac | Me | 1.32±0.23 | 4.76±0.52 |

| 29f | D | Ac | -- | 0.46±0.19 | 1.18±0.03 |

| 30b | A | Ac | H | 0.56±0.05 | 1.53±0.14 |

| 30d | B | Ac | H | 1.23±0.00 | 1.54±0.41 |

| 30g | C | Ac | H | 0.91±0.21 | 2.08±0.13 |

| 31a | A | H | Me | 0.76±0.17 | 1.09±0.10 |

| 31b | A | H | H | 0.47±0.10 | 0.85±0.09 |

| 31c | B | H | Me | 4.69±0.16 | 10.12±0.17 |

| 31d | B | H | H | 0.79±0.11 | 1.68±0.25 |

| 31e | C | H | Me | 9.45±0.22 | 13.48±0.38 |

| 31f | D | H | -- | 0.44±0.02 | 1.35±0.38 |

| 31g | C | H | H | 0.75±0.12 | 1.33±0.01 |

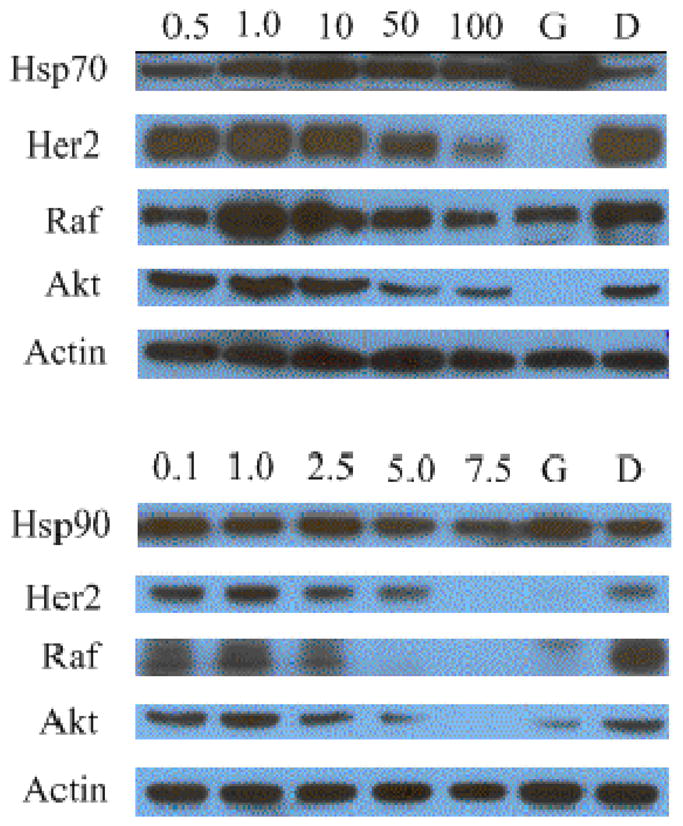

To confirm that replacement of noviose with a sugar or amino surrogate did not alter inhibitory activity against Hsp90, western blot analyses of cell lysates following the administration of 18b or 31b were performed. As shown in Figure 2, the Hsp90-dependent client proteins, Her2, Raf and Akt, were degraded in MCF-7 cells in a concentration-dependent manner upon treatment with 18b or 31b. The non-Hsp90-dependent protein, actin, was not altered upon administration of 18b or 31b, indicating selective degradation of Hsp90-dependent proteins takes place in the presence of 18b or 31b. In addition, neither of these two compounds induced the heat shock response, which is a characteristic shared by benzamide-containing novobiocin analogues that bind the Hsp90 C-terminus.28,29

Figure 2.

Western blot analyses of Hsp90-depedent client proteins from MCF-7 breast cancer cell lysates upon treatment with 18b (top) or 31b (bottom). Concentrations (in μM) were indicated above each line, geldanamycin (G, 0.5 μM) and dimethyl sulfoxide (D) were employed as positive and negative controls.

In a conclusion, sugar mimics and amino analogues of the noviose appendage on the coumarin ring of novobiocin that exhibit improved solubility and anti-proliferative activity have been produced. The cyclic and acyclic amino surrogates can be synthesized expeditiously and will enable rapid identification of novobiocin analogues that may provide clinical opportunities for the treatment of cancer. The development of improved compounds that exhibit such activity is underway and the results from those studies will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledge support of this project by the NIH/NCI (CA120458)

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures for the synthesis and characterization of new compounds (1H and 13C NMR, HRMS). This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Pearl LH, Prodromou C, Workman P. The Hsp90 Molecular Chaperone: An Open and Shut Case for Treatment. Biochem J. 2008;410:439–53. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blagg BSJ, Kerr TD. Hsp90 Inhibitors: Small Molecules that Transform the Hsp90 Protein Folding Machinery into A Catalyst for Protein Degradation. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:310–338. doi: 10.1002/med.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu W, Neckers L. Targeting the Molecular Chaperone Heat Shock Protein 90 Provides a Multifaceted Effect on Diverse Cell Signaling Pathways of Cancer Cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1625–1629. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Burrows FJ. Targeting Multiple Signal Transduction Pathways Through Inhibition of Hsp90. Mol Med. 2004;82:488–499. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop SC, Burlison JA, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90: A Novel Target for the Disruption of Multiple Signaling Cascades. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:369–388. doi: 10.2174/156800907780809778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sausville EA, Tomaszewski JE, Ivy P. Clinical Development of 17-Allylamino, 17-Demethoxygeldanamycin. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2003;3:377–383. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacey S, Banerji U, Judson I, Workman P. Hsp90 Inhibitors in the Clinic. Handb Exp Pharmaco. 2006:331–358. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29717-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhury S, Welch TR, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90 as A Target for Drug Development. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:1331–1340. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N. Drugging the Cancer Chaperone HSP90: Combinatorial Therapeutic Expolitation on Oncogene Addiction and Tumor Stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:202–216. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neckers L, Neckers K. Heat-shock Protein 90 Inhibitors as Novel Cancer Chemotherapeutics - An Update. Expert Opin Emerging Drugs. 2005;10:137–149. doi: 10.1517/14728214.10.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoeksema H, Johnson JL, Hinman JW. Structural Studies on Streptonivicin, A New Antibiotic. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:6710–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooper DC, Wolfson JS, McHugh GL, Winters MB, Swartz MN. Effects of Novobiocin, Coumermycin A1, Clorobiocin, and Their Analogs on Escherichia Coli DNA Gyrase and Bacterial Growth. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;22:662–671. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.4.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutta R, Inouye M. GHKL, An Emergent ATPase/kinase Superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcu MG, Chadli A, Bouhouche I, Catelli M, Neckers LM. The Heat Shock Protein 90 Antagonist Novobiocin Interacts with a Previously Unrecognized ATP-binding Domain in the Carboxyl Terminus of the Chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37181–37186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen G, Yu Xm, Blagg BSJ. Syntheses of Photolabile Novobiocin Analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:5903–5906. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu XM, Shen G, Neckers L, Blake H, Holzbeierlein J, Cronk B, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90 Inhibitors Identified from a Library of Novobiocin Analogues. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12778–12779. doi: 10.1021/ja0535864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burlison JA, Neckers L, Smith AB, Maxwell A, Blagg BSJ. Novobiocin: Redesigning a DNA Gyrase Inhibitor for Selective Inhibition of Hsp90. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15529–15536. doi: 10.1021/ja065793p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burlison JA, Blagg BSJ. Synthesis and Evaluation of Coumermycin A1 Analogues that Inhibit the Hsp90 Protein Folding Machinery. Org Lett. 2006;8:4855–4858. doi: 10.1021/ol061918j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang YT, Blagg BSJ. A Library of Noviosylated Coumarin Analogues. J Org Chem. 2007;72:3609–3613. doi: 10.1021/jo062083t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burlison JA, Avila C, Vielhauer G, Lubbers DJ, Holzbeierlein J, Blagg BSJ. Development of Novobiocin Analogues That Manifest Anti-proliferative Activity against Several Cancer Cell Lines. J Org Chem. 2008;73:2130–2137. doi: 10.1021/jo702191a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donnelly AC, Mays JR, Burlison JA, Nelson JT, Vielhauer G, Holzbeierlein J, Blagg BSJ. The Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Coumarin Ring Derivatives of the Novobiocin Scaffold that Exhibit Antiproliferative Activity. J Org Chem. 2008;73:8901–8920. doi: 10.1021/jo801312r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ansar S, Burlison JA, Hadden MK, Yu XM, Desino KE, Bean J, Neckers L, Audus KL, Michaelis ML, Blagg BSJ. A non-toxic Hsp90 Inhibitor Protects Neurons from Abeta -induced toxicity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1984–1990. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y, Ansar S, Michaelis ML, Blagg BSJ. Neuroprotective Activity and Evaluation of Hsp90 Inhibitors in an Immortalized Neuronal Cell Line. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu XM, Shen G, Blagg BSJ. Synthesis of (−)-Noviose from 2,3-O-Isopropylidene-D-erythronolactol. J Org Chem. 2004;69:7375–7378. doi: 10.1021/jo048953t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu XM, Han H, Blagg BSJ. Synthesis of Mono- and Dihydroxylated Furanoses, Pyranoses, and an Oxepanose for the Preparation of Natural Product Analogue Libraries. J Org Chem. 2005;70:5599–5605. doi: 10.1021/jo050558v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown EG. Ring Nitrogen and Key Biomolecules: the Biochemistry of N-heterocycles. Kluwer Academic; Boston: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donnelly A, Blagg BSJ. Novobiocin and Additional Inhibitors of the Hsp90 C-terminal Nucleotide Binding Pocket. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2702–2717. doi: 10.2174/092986708786242895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shelton SN, Shawgo ME, Matthews SB, Lu Y, Donnelly AC, Szabla K, Tanol M, Vielhauer GA, Rajewski RA, Matts RL, Blagg BSJ, Robertson JD. KU135, a Novel Novobiocin-Derived C-Terminal Inhibitor of the 90-kDa Heat Shock Protein, Exerts Potent Antiproliferative Effects in Human Leukemic Cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:1314–1322. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.