Abstract

Objectives

HIV continues to disproportionately affect men who have sex with men (MSM). As a result of the impact of HIV among MSM, multiple strategies for reducing HIV risks have emerged from within the gay community. One common HIV risk reduction strategy is to limit unprotected sex partners to those who are of the same HIV status, or to serosort. Although serosorting is commonly practiced for risk reduction, it is closely linked to HIV transmission because of infrequent HIV testing, lack of HIV status disclosure, sexually transmitted infections, and acute HIV infection.

Methods

The current study tested a novel, brief, one-on-one, peer counselor-delivered intervention based on informed decision making, to address the limitations of serosorting. One hundred forty nine at-risk men were recruited and randomly assigned to an intervention condition addressing serosorting or a standard-of-care control.

Results

Men in the serosorting intervention reported fewer sexual partners (Wald X2=8.79,p=<.01) at study follow-ups.

Discussion

Addressing risks associated with serosorting in a feasible, low -cost intervention has the potential to significantly impact the HIV epidemic.

In the U.S. alone, there are over 56,000 new HIV infections each year; the majority of which occur among men who have sex with men (MSM; Centers for Disease Control, 2007). The stable number of MSM becoming HIV infected testifies to the need for new and innovative approaches to HIV prevention for this highest priority population. Community-based prevention programs for MSM have dwindled over the past decade and there are only three evidence-based interventions designed specifically for MSM disseminated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, none of which are individual-level or brief interventions (effectiveinterventions.org). The limited attention to MSM in HIV prevention services has left men to create their own strategies for HIV risk reduction, such as serosorting, or limiting partners to those who are of the same HIV status (Eaton et al., 2007; Golden et al., 2007; Mao et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2006). Serosorting provides an alternative to condom use and thus addresses another factor that has stymied HIV prevention, safer sex fatigue. As such, engaging in serosorting practices has allowed MSM to feel safe from HIV when having unprotected sex, yet ultimately these men are exposing themselves to HIV via flaws in serosorting. Although MSM may use serosorting as a means of prevention, information regarding serosorting must highlight its limitations and stress the importance of condom use.

Similar to other partner selection strategies, serosorting relies on assumptions and beliefs that when unmet diminish the theoretical benefits of this strategy (Clatts, Goldsamt, & Yi, 2005; Elford, Bolding, & Hart, 2007; Mao, 2006; Xia, 2006). Restricting unprotected sexual practices to partners who are HIV positive among people who are already HIV infected does prevent new HIV infections but can also increase the risk for other health compromising sexually transmitted infections (STI). More concerning are the failings of serosorting among those who believe they are HIV negative. Unlike HIV positive men who can be sure of their HIV status, it is impossible for someone to engage in continued risk behavior and be certain that they are HIV negative. Even if individuals routinely test for HIV before changing sexual partners, serosorting is not sufficient to prevent infections due to the possibility of testing HIV negative during the acute infection phase (Pilcher et al., 2005).

As many as half of all persons diagnosed with HIV deny engaging in risk behaviors with any HIV positive or HIV unknown status partners (Golden, 2006). In a retrospective study of recently HIV infected MSM who reported unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), one in five were certain their sex partner, who was the source of their HIV infection, was HIV negative (Jin et al., 2007). Increased risk for HIV infection was also associated with engaging in sex with HIV negative partners in longitudinal studies (Koblin et al., 2006). Misrepresenting HIV status, or falsely disclosing, may also be an important factor in explaining these findings (Golden et al., 2007). Among men who had recently seroconverted, one in three had serosorted (Golden, 2008). Finally, Butler and Smith (2007) demonstrated through modeling that the risk associated with sex with a high-risk HIV negative partner confers greater likelihood for HIV infection than does sex with an HIV positive partner. This paradoxical finding is explained by the possibility of the HIV negative partner being acutely HIV infected and the HIV positive partner being treated by antiretrovirals, and therefore, less infectious. Thus, there is an urgent need for realistic, feasible, and effective interventions to address the risks associated with serosorting among MSM.

The current study was conducted to test a primary prevention intervention aimed at promoting informed decision making that would be feasible for implementation in public health settings. The intervention was therefore delivered in a brief, single-session, and administered one-on-one using peer counselors that incorporated an innovative approach grounded in conflict theory of decision-making (Janis and Mann, 1977). Conflict theory focuses on weighing the risks and benefits of possible behavioral options as a means of making the most effective decision. In this case, conflict theory was used to deliver information about the risks associated with choosing partners who are believed to pose reduced risk for HIV (i.e. serosorting). The use of conflict theory allowed for two critical components during intervention: (a) informed personal decision making around partner selection; a strategy that not only encourages risk reduction but prepares individuals to make safer decisions when in risky situations, and (b) creating a teachable moment; a time period and emotional state in which persons are more receptive to alternative behavioral choices (Lawson et al., 2009). During a teachable moment people are more open to change and have more motivation for doing so, creating an important window of opportunity for intervention. Finally, the intervention was delivered in part through the use of a graphic novel, which allowed for counselors to provide information about serosorting in an interactive, informative, and non-intimidating manner. We hypothesized that this intervention would result in significantly greater risk reduction compared to a time-matched, standard-of-care, risk-reduction, control intervention.

METHODS

Overall study design

This two-condition, randomized efficacy trial was conducted at a community-based research site in the downtown area of Atlanta, GA from March 2009 to October 2009. Both intervention and control counseling sessions lasted approximately 40 minutes. Participants were asked to visit the study site three times: the baseline intervention session and two follow-up assessments occurring 1 - month and 3 - months post intervention.

Participants

Participants were recruited through flyers, advertisements, and in-field recruitment methods to capture a diverse sample of men. Flyers were placed at HIV testing sites, treatment centers, and gay identified venues such as bars, bathhouses, and clubs. Advertisements were placed in local gay newspapers and on an internet classifieds website. Participants were screened for study eligibility using 4 criteria: (a) male/transgendered, (b) eighteen years of age or older (c) did not report HIV positive status, and (d) reported two or more male unprotected anal sex partners in the last six months. Eligible participants were immediately given appointment times and further information about the study location. Participants were paid up to $120 for their participation in the study (baseline - $35, 1-month - $40, and 3 - month $45).

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked their age, years of education, income, ethnicity, employment status, sexual orientation, how out they are about sexual orientation, and relationship status.

HIV status, testing, and STI history

Participants were asked to report the results of their most recent HIV test, and how often they test for HIV. Participants also reported on whether they had ever had an STI.

Substance use

Participants were asked about their alcohol, marijuana, nitrite inhalants (poppers), powder or crack cocaine, methamphetamine, viagra/cialis/levitra without a prescription, intravenous drug use, or other drug use in the past three months. In addition, the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST 10; Skinner, 1982) and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) were administered to assess drug and alcohol abuse, respectively. As determined by prior research, drug abuse problems were defined as scoring a 3 or greater on the DAST and alcohol related problems were defined as scoring a 7 or greater on the AUDIT.

Condom use self-efficacy

Six questions were used to assess participants’ self-efficacy for condom use during sexual negotiation with a partner (adapted from Brafford and Beck,1991). For example, questions included, “I feel confident in my ability to discuss condom usage with any partner I might have” and “I feel confident in my ability to put a condom on myself or my partner”. Responses ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. This scale demonstrated internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = .84.

Risk perceptions

Participants were instructed to report on how much risk for HIV they perceived for different scenarios. Questions included, “How risky is anal sex without a condom as the bottom partner with a man you just met who tells you his HIV status is negative?” and “How risky is anal sex without a condom as the bottom partner with a man you just met who tells you his HIV status is negative and that he just recently tested negative?” (Eaton et al., 2007). Response ranged from 0 = No or Low Risk to 10 = Very High Risk. Responses to the two items were highly correlated and, thus, averaged together and treated as one variable.

Sexual behavior outcomes

Participants were asked about their sexual partners and specific sexual acts. Participants reported their total number of sexual partners, number of HIV negative partners, and number of HIV positive/unknown status partners they had in the past month. They were then asked about the number of unprotected (condomless) anal sex acts they had engaged in with HIV negative partners and HIV positive/unknown partners in the past month. HIV negative partners were assessed separately to reflect serosorting behaviors.

Procedures and Randomization

Participants were given informed consent and all study procedures were approved by the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board. Upon consent into the study, participants were randomly assigned to one of two arms: a single session, counselor delivered, partner-selection intervention; or a time-matched, HIV risk-reduction, standard-of-care, control intervention.

Intervention and control arm development

Serosorting risk reduction intervention

The main focus of the intervention was to highlight misbeliefs about selecting sexual partners, shape accurate beliefs and perceptions of risk about the effectiveness of serosorting, and determine a practical, skills-based, strategy tailored for each participant.

A graphic novel was created for the purpose of conveying messages about serosorting. This graphic novel depicts the fictitious, though evidence-based, story of a man who tests HIV negative, uses serosorting as an HIV prevention strategy, and then tests HIV positive at the end of the story. This activity led to a discussion about how the main character could have become infected (acute HIV infection, non-explicit disclosure of HIV status, misrepresenting HIV status, infrequent HIV testing etc.) or infected his partners. Guided by conflict theory, the counselor and participant worked together to identify and discuss these varying scenarios, with on focus on what the main character could have done to reduce his risk for HIV.

Next participants were shown a visual diagram depicting the main character’s sexual partners and acts. The character’s sexual network diagram was provided to help facilitate discussions related to ways in which the character exposed himself to HIV. Then participants were asked to create their own sexual network diagram by providing information about their sexual partners and acts from the past six months. Participant diagrams were compared and contrasted with the character’s diagram, thereby allowing the participants to observe how their behaviors related to those of an evidence-based character who tests HIV positive. Through this activity participants readily reflected on instances in which they potentially exposed themselves to HIV, thus creating a teachable moment.

Participants used their own sexual network diagram as a guide to forming a plan they could carryout to reduce their risks for HIV. Specifically, they reviewed the occasions in which they have unwittingly put themselves at risk for HIV in the past and discussed what they could do differently in the future to reduce their risk. In keeping with informed decision making, participants were guided towards a risk reduction plan that was considerable reasonable by the participant to carry out. This included increases in condom use, reductions in sexual partners and acts, alternatives to UAI, and greater inquiry into a sexual partner’s HIV status and testing history. Thus, the participant along with the counselor generated a menu of harm reduction options by weighing the relative costs and benefits of each and deciding on the optimal choice.

Control intervention

Participants in the control arm received standard, HIV risk-reduction counseling consistent with CDC guidelines (Anderson et al., 2001). The counselor addressed general problems that posed barriers to HIV risk reduction. Client centered counseling techniques (e.g., open-ended questions, attentive listening, and a nonjudgmental and supportive approach) were used to discuss the participant’s personal HIV risks and the strategies they could use to reduce their risks.

Data Analyses

In order to test the integrity of randomization and potential differential attrition among participants at follow-up, the combined modified design proposed by Jurs and Glass, (1971) was used. A series of 2 × 2 ANOVAs were performed in which the condition (intervention and control) served as one factor and attrition (showed at follow-up versus not showed at follow-up) served as a second factor, as well as their interaction. Attrition was based on the final follow-up time point and tested key demographic variables and sexual behaviors. Chi-square and t-tests were used to test for differences in additional variables at baseline. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) using an unstructured working correlation matrix and Poisson distribution with log-link function for count data or normal distribution for scaled data were used to analyze the main outcomes. Baseline behavioral data was treated as a covariate, and condition, time, condition x time were entered as model effects. Planned pairwise contrasts with least significant difference adjustment were used to test for simple effects.

RESULTS

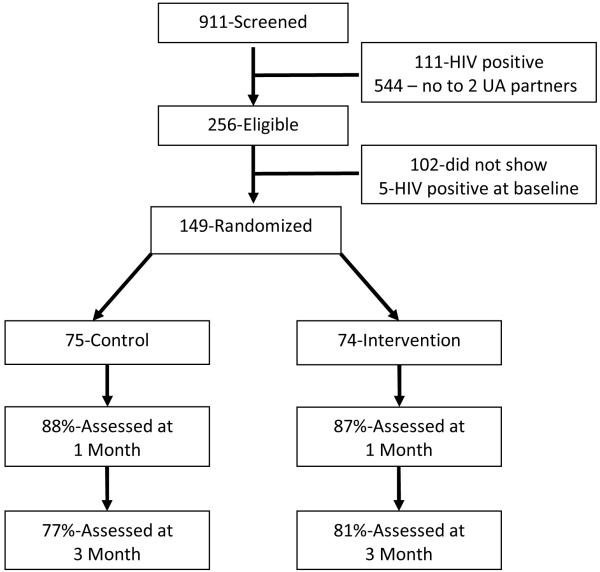

For this study, 911 men were screened during the recruitment process to determine eligibility (see Figure 1). Because the intervention arm focused on serosorting specifically for partners who were believed to be HIV negative, all men who reported being HIV positive (n = 111) were screened out of the study and referred to alternate study opportunities at the research site. Of the remaining 800 men screened for the study in terms of ethnicity, they were 64% Black, 17% White, 3% Latino, 1% Asian, and 5% other. A total of 544 men did not screen into the study because of not reporting at least two unprotected anal sex partners in the past six months. In total, of the 256 (28%) men screened into the study, 149 (58%) men enrolled in the study. Retention rate at 1 month follow-up was 88% control, 87% intervention and at 3 month follow-up was 77% control, 81% intervention; differences were non-significant.

Figure 1. Flow chart of participant recruitment and enrollment.

Combined modified design to test for randomization and attrition differences

For these analyses the following variables were tested: age, education, income, sexual orientation, how out about sexual orientation, relationship status, DAST, AUDIT, and total number of male sexual partners. There were no differences between conditions for any of these variables and thus balance due to randomization of participants to either the intervention or the comparison control condition was achieved. For attrition, men were more likely to drop from study if they were out about their sexual orientation. No other differences were observed on any variable (see Table 1). As such, no major differences emerged between men who dropped or remained in study.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of men in intervention and control conditions.

| Intervention | Control | Condition | Attrition | Condition x Attrition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Age | 28.3 | 10.4 | 30.0 | 9.6 | .44 | .51 | 2.12 | .15 | .07 | .80 |

| Education | 14.0 | 2.0 | 13.8 | 2.0 | .61 | .44 | .49 | .49 | .36 | .55 |

| n | % | n | % | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Income | .02 | .90 | .01 | .97 | .01 | .99 | ||||

| $0-$10,000 | 27 | 37.5 | 29 | 38.7 | ||||||

| $11-$20,000 | 14 | 19.4 | 15 | 20.0 | ||||||

| $21-$30,000 | 10 | 13.9 | 7 | 9.3 | ||||||

| $31-$40,000 | 8 | 11.1 | 7 | 9.3 | ||||||

| $41-$50,000 | 5 | 6.9 | 8 | 10.7 | ||||||

| $51-60,000 | 3 | 4.2 | 4 | 5.3 | ||||||

| $61,000 + | 5 | 6.9 | 5 | 6.7 | ||||||

| Sexual Orientation | .18 | .68 | .13 | .72 | .14 | .71 | ||||

| Gay | 55 | 75.3 | 54 | 72.0 | ||||||

| Bisexual | 16 | 21.9 | 20 | 26.7 | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 2 | 2.7 | 1 | 1.3 | ||||||

|

How out about

sexual orientation |

.31 | .58 | 4.77 | .03 | .02 | .90 | ||||

| Not out | 6 | 8.1 | 5 | 6.9 | ||||||

| Out sometimes | 30 | 40.5 | 37 | 50.0 | ||||||

| Out always | 38 | 51.4 | 32 | 43.2 | ||||||

| Relationship status | .27 | .61 | 1.38 | .24 | .06 | .80 | ||||

| Not having sex |

11 | 14.9 | 8 | 10.7 | ||||||

| Having sex but no exclusive partner |

46 | 62.2 | 51 | 68.0 | ||||||

| Have main partner and outside partners |

10 | 13.5 | 9 | 12.0 | ||||||

| Have exclusive partner |

7 | 9.5 | 7 | 9.3 | ||||||

| DAST | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | .40 | .53 | .01 | .91 | .10 | .34 |

| percent 3 or higher | 44.6% | 37.3% | ||||||||

| AUDIT | 6.9 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 8.2 | .01 | .96 | .07 | .79 | .27 | .60 |

| percent 7 or higher | 39.2% | 44.0% | ||||||||

| Intervention | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | X2(df) | p | |

| Ethnicity | .91(3) | .82 | ||||

| White | 18 | 24.0 | 14 | 17.9 | ||

| Black | 50 | 69.3 | 55 | 73.1 | ||

| Hispanic | 2 | 2.7 | 3 | 3.8 | ||

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other | 3 | 4.0 | 3 | 5.1 | ||

| Employment | .06(1) | .81 | ||||

| Yes | 34 | 45.9 | 33 | 44.0 | ||

| No | 40 | 54.1 | 42 | 56.0 | ||

| Drug use | ||||||

| Alcohol | 66 | 89.2 | 64 | 85.3 | .50(1) | .48 |

| Marijuana | 42 | 56.8 | 38 | 50.7 | .56(1) | .46 |

| Cocaine | 16 | 21.6 | 15 | 20.3 | .06(1) | .81 |

| Nitrate inhalants | 9 | 12.2 | 12 | 16.0 | .45(1) | .50 |

| Methamphetamine | 4 | 5.4 | 6 | 8.0 | .40(1) | .53 |

| Viagra/Cialis/Levitra | 7 | 9.5 | 10 | 13.3 | .55(1) | .46 |

| Intravenous drug use | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.7 | .33(1) | .57 |

| Other drug use | 12 | 16.2 | 13 | 17.3 | .03(1) | .86 |

| HIV status | 2.14(1) | .54 | ||||

| Negative | 70 | 93.3 | 67 | 91.8 | ||

| Unknown | 5 | 6.7 | 6 | 8.2 | ||

|

How often are you

tested for HIV? |

4.03(4) | .40 | ||||

| Less than yearly | 15 | 21.1 | 16 | 22.5 | ||

| Yearly | 15 | 21.1 | 17 | 23.9 | ||

| Every 6 months | 31 | 43.7 | 23 | 32.4 | ||

| Every 3 months | 10 | 14.1 | 13 | 18.3 | ||

| Monthly | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.8 | ||

|

Have you ever had a sexually

transmitted disease (STD)? |

.01(1) | .93 | ||||

| Yes | 36 | 48.0 | 35 | 47.3 | ||

| No | 39 | 52.0 | 39 | 52.7 | ||

Note: Relationship status was recoded to represent a continuous variable progressing from no sexual contact, to sex with exclusive partner, to sex with casual partners.

HIV status, testing, and STI history

Men in both the intervention and control arms were similar in terms of their HIV testing histories with a majority of men testing every six months or less frequently (i.e., yearly or less than yearly). Almost half the men in the study reported having been infected with an STI in their lifetime (see Table 1).

Alcohol and drug use

Men in both study conditions reported similar rates of substance use (see Table 1). Overall, drug and alcohol use were high with well over a third of the men reporting scores on the DAST or AUDIT consistent with an abuse problem.

Condom use self-efficacy and risk perceptions

Men in the intervention condition reported greater self-efficacy when negotiating condom use with sexual partners than men in the comparison control condition, controlling for baseline condom use self-efficacy. Risk perceptions were correlated with ethnicity, namely Black participants reported greater perceived risk than White participants. As such for this analysis, ethnicity and baseline risk perception were controlled. Participants in the intervention condition reported a marginally significant greater perception of risk for HIV during sex with HIV negative partners on the follow-up assessments than participants in the control condition. Time and condition/time interaction were not significant (See Table 2).

Table 2. GEE analysis of psychosocial measures, sexual partners and unprotected sexual acts.

| Intervention | Control | Condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M c | SE | M | SE | Wald X2 | p | |

| Condom use self-efficacy | ||||||

| 1 – Month | 5.49 | .08 | 5.28 | .12 | 5.12 | <.05 |

| 3 – Month | 5.62 | .08 | 5.25 a | .11 | ||

| Risk perceptions | ||||||

| 1- Month | 9.15 | .17 | 8.57 a | .21 | 3.56 | .07 |

| 3 – Month | 9.18 | .22 | 8.89 | .23 | ||

| Total number of male sexual partners in past month |

8.79 | <.01 | ||||

| 1 – Month | 1.42 | .18 | 2.67 a | .47 | ||

| 3 – Month | 1.31 | .20 | 2.44 a | .47 | ||

| Number of HIV negative partners |

2.28 | .13 | ||||

| 1 – Month | .91 | .16 | 1.44 b | .28 | ||

| 3 – Month | .81 | .17 | .99 | .16 | ||

| Number of HIV positive unknown partners |

6.93 | <.01 | ||||

| 1 – Month | .47 | .12 | 1.22 | .43 | ||

| 3 – Month | .49 | .15 | 1.47b | .47 | ||

| Sex with HIV negative partners | ||||||

| Number of unprotected anal sex acts |

.50 | .48 | ||||

| 1 – Month | 2.12 | .67 | 1.08 | .35 | ||

| 3 – Month | 1.03 | .39 | 1.14 | .47 | ||

| Sex with HIV positive/unknown partners | ||||||

| Number of unprotected anal sex acts |

2.61 | .11 | ||||

| 1 – Month | .26 | .10 | .79a | .20 | ||

| 3 – Month | .30 | .14 | .44 | .15 | ||

Note: Pairwise contrasts revealed significant

(= <.05) and marginally significant

(= .07) differences at time point.

Adjusted means are presented.

Sexual partners and sexual behavior outcomes

Analyses demonstrated that number of sexual partners was significantly less for men in the serosorting intervention condition compared to control when controlling for baseline number of partners. Planned comparisons showed that the serosorting intervention participants reported fewer sexual partners at both follow-ups. Number of negative partners was similar for both groups, however, there was a marginally significant difference where intervention participants reported fewer negative partners at 1 – month than control participants. Men in the serosorting intervention condition were more likely to report fewer numbers of HIV positive/unknown partners than men in the comparison condition, controlling for baseline number of HIV positive/unknown partners.

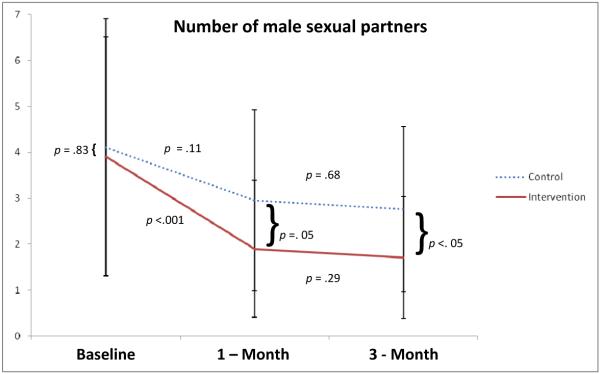

Number of unprotected acts with HIV negative and positive/unknown partners was similar across groups, with the exception of a significant difference in number of acts at 1-month assessments where serosorting intervention participants reported fewer unprotected acts with HIV positive/unknown partners. Time and condition/time interaction were not significant for any of the analyses (see Table 2). In additional analyses, baseline number of partners was treated as a dependent variable, not as a covariate, in order to present all possible relevant contrasts between groups and time points. For this analysis, pairwise contrasts of estimated marginal means showed a significant drop in number of male partners among intervention participants between baseline and 1 – month follow-up and remained significant at 3 – month follow-up (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Contrasts for number of male sexual partners at baseline, 1 – month and 3 – month follow-ups.

Note: For this figure only, baseline was treated as a dependant variable in GEE in order to assess differences in number of sexual partners at all points in study.

DISCUSSION

Findings from the current study demonstrate that a brief, single-session, theory-based intervention, framed by informed decision making, and focused on partner selection, can be effective in reducing number of sexual partners reported at short-term follow-up. Importantly, a decrease in number of sexual partners can result in a net reduction in risk for HIV infection. Although the relationship between number of partners and likelihood of HIV infection is non-linear, having multiple partners is related to HIV infection (Catania, et al., 2005). As such, even though long-term, mutually-monogamous, relationships are most effective for HIV risk reduction, reducing number of sexual partners can also lower the likelihood of HIV infection. Number of sexual partners is particularly important when partnerships overlap in time, or sexual concurrency, which has clear implications for HIV to transmit rapidly through existing networks (Watts & May, 1992). Furthermore, sexual concurrency appears to be particularly relevant to sexual networks of Black MSM, in which recent data supports the possibility that Black MSM are at higher risk for HIV transmission than non-Black MSM not due solely to their sexual behaviors, but due, in part, to higher HIV prevalence in their sexual networks (Bohl et al., 2009; Raymond & McFarland, 2009)

Measures of psychosocial variables were also consistent with the behavioral findings at short-term follow-up. An increase in condom use self-efficacy may have resulted from heightened awareness of risk and/or increased motivation to protect oneself when making sexual decisions. Evidence of a trend towards increased perception of risk for HIV among serosorting intervention participants is also consistent with condom use self-efficacy and behavioral outcomes. Changes in these psychosocial variables further support the behavioral risk reduction observed in the outcomes.

A critical component of this serosorting intervention was the ability to recruit persons who are arguably at the greatest risk for HIV infection in the US, namely, Black MSM in a high HIV prevalence city. Surveillance reports of HIV infection in the state of Georgia indicate that 78% of HIV infections are among Black men and women, but they make up only 30% of the overall population. Furthermore, data representing infection rates among MSM in Georgia have shown that young Black MSM make up 24% of overall incident infections, while their White counterparts make up only 3% (Georgia Data Summary, HIV/AIDS Surveillance, 2008). Clearly there exist grave health disparities, and therefore, addressing the needs of Black MSM must be a public health priority.

These results should be considered in light of limitations of the study. The current study was a test of concept of a serosorting intervention and requires further testing in a larger scale trial. Data analysis included up to a 3 month time point, which limits the long-term conclusions that can be made. Intervention effects may be prone to dissipating over time as well and the current data don’t allow for addressing this concern. However, data from the time points used do warrant further research with a larger sample size and an extended follow-up period. Moreover, future trials should also include biological outcomes to assess STIs over study follow-ups. An assessment of biological outcomes is a critical component of evaluating intervention effectiveness as it is an indicator of sexual risk taking and it removes biases stemming from self-reported STI data. Furthermore, in general participants reported low income and high rate of unemployment; these factors should be considered when interpreting findings. Socioeconomic status (SES) of men may have implications for risk reduction and the current intervention should be tested with MSM from varying SES in order to more fully understand the intervention effects. Finally, although screening men allowed for us to target those who are at risk for HIV infection, findings can’t be generalized to men who did not meet entry criteria.

There exists a demand for prevention to address more than simple messages of always using condoms or remaining abstinent. A one size fits all strategy is not effective for all men whose needs must be individually addressed. The current state of HIV prevention among MSM must also deal with safer sex fatigue that is experienced by many men at greatest risk for HIV infection. To that end, informed decision making particularly in the area of serosorting and other partner risk reduction strategies should be incorporated into current HIV prevention packages. Serosorting interventions driven by informed decision making will allow for empowering men to make educated choices about their sexual behaviors, and provide the tools needed to effectively manage scenarios in which HIV transmission is most likely to occur. With the potential for a single-session, partner-selection, intervention to have extensive reach, coupled with its minimal impact on limited resources, further study of efficacy and effectiveness of this type of intervention is a prudent investment.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the guidance and feedback on this project from Seth Kalichman, David Kenny, Dean Cruess, Blair Johnson, and Crystal Park. The authors thank the AIDS Survival Project of Atlanta for their assistance with data collection. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants 5R01MH074371, T32MH074387, and T32MH020031 supported this research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Human participant protection: This study was approved by the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board.

References

- Anderson TJ, Atkins D, Baker-Cirac C, Bayer R, Beadle de Palomo F, Bolan GA, et al. Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2001;50:1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brafford LJ, Beck KH. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. Journal of American College Health. 1991;39:219–225. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohl DD, Raymond HF, Arnold M, McFarland W. Concurrent sexual partnerships and racial disparities in HIV infection among men who sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85:367–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler DM, Smith AM. Serosorting can potentially increase HIV transmission. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;21:1218–1220. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32814db7bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Osmond D, Neilands TB, Canchola J, Gregorich S, Shiboski S. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29:86–95. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902_2. Commentary on Schroder et al. (2003a, 2003b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS statistics and surveillance. 2007 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm#hivaidsexposure.

- Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, Yi H. An emerging HIV risk environment: a preliminary epidemiological profile of an MSM POZ party in New York City. 2005;81:373–376. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Cain DN, Cherry C, Stearns HL, Amaral CM, Flanagan JA, Pope HL. Serosorting sexual partners and risk for HIV among men who have sex with men. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elford J, Bolding G, Hart G. No evidence of an increase in serosorting with casual partners among HIV-negative gay men in London, 1998-2005. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;21:243–245. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280118fdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgia Data Summary . HIV/AIDS Surveillance. Georgia Department of Community Health; 2008. http://health.state.ga.us/pdfs/epi/hivstd/HIV%20Data%20Summary%2010_16_08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Golden MR, Stekler J, Hughes JP, Wood RW. HIV serosorting in men who have sex with men: is it safe? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2008;49:212–218. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden MR, Wood RW, Buskin SE, Fleming M, Harrington RD. Ongoing risk behavior among persons with HIV in medical care. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:726–735. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden M. HIV serosorting among men who have sex with men: implications for prevention; 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Janis IL, Mann L. Decision-making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. Free Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jin F, Prestage GP, Ellard J, Kippax SC, Kaldor JM, Grulich AE. How homosexual men believe they became infected with HIV: The role of risk-reduction behaviors. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;46(2):245–247. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181565db5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurs S, Glass GV. The effect of experimental mortality on the internal and external validity of the randomized comparative experiment. Journal of Experimental Education. 1971;40(1):62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;20:731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson PJ, Flocke SA. Teachable moments for health behavior change: a concept analysis. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;76:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Crawford JM, Hospers HJ, Prestage GP, Gruhlich AE, Kaldor JM, Kippax SC. ‘Serosorting’ casual anal sex of HIV-negative gay men is noteworthy and is increasing in Sydney, Australia. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;20:1204–1205. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226964.17966.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, Foust E, Wolf L, Williams D, Ashby R, O’Dowd JO, McPherson JT, Stalzer B, Hightow L, Miller WC, Eron JJ, Cohen MS, Leone PA. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:1873–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:630–637. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2007;44:240–248. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.44.3.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Screening Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST): Guidelines for administration and scoring. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, May The influence of concurrent partnerships on the dynamics of HIV/AIDS. Mathematical Biosciences. 1992;108:89–104. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(92)90006-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Q, Molitor F, Osmond DH, Tholandi M, Pollack LM, Ruiz JD, Catania JA. Knowledge of sexual partner’s HIV serostatus and serosorting practices in a California population-based sample of men who have sex with men. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;20:2081–2089. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247566.57762.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]