SUMMARY

Host mechanisms enabling discrimination between the commensal and pathogenic states of opportunistic pathogens are critical in mucosal defense and homeostasis. Here, we demonstrate that oral epithelial cells orchestrate an innate response to the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans via NF-κB and a bi-phasic MAPK response. Activation of NF-κB and the first MAPK phase, constituting c-Jun activation, is independent of morphology and due to the recognition of fungal cell wall structures. Activation of the second MAPK phase, constituting MKP1 and c-Fos activation, is dependent upon hypha-formation and fungal burdens, and correlates with proinflammatory responses. This MAPK-based discriminatory pathway may provide a mechanism for epithelial tissues to remain quiescent in the presence of low fungal burdens whilst responding specifically and strongly to damage-inducing hyphae when burdens increase. MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos activation may thus comprise a `danger response' pathway in vivo and may be critical in identifying when this normally commensal fungus has become pathogenic.

INTRODUCTION

Mucosal epithelia possess distinct mechanisms that enable discrimination between harmless commensal organisms and disease-causing pathogenic organisms. This process results in either non-responsiveness or homeostasis (commensals), or activation of an immune response (pathogens). Although much attention has been given to bacteria in this context, the same cannot be said for fungal pathogens, which are often clinically more important than their bacterial counterparts. The most significant fungal pathogens of humans are Candida species, some of which are polymorphic organisms capable of growing either as yeasts or hyphae. Candida species, particularly C. albicans, are normal constituents of the normal oral and gut flora in approximately 50% of the population but can also cause a variety of mucosal diseases with significant morbidity (Odds, 1988). Given that potentially life-threatening systemic complications arise from breaches of the mucosal barrier, it is of paramount importance to understand how epithelial cells recognize and restrict these fungi to mucosal surfaces. Currently, we lack understanding of how Candida pathogens interact with human mucosal surfaces, or the immune mechanisms that enable epithelial cells to discriminate between the different morphological states of these fungi.

Innate immune responsiveness to pathogens is usually mediated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs recognize specific pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which leads to the activation of intracellular signaling pathways and specific transcription factors to mediate their effects (Kumagai et al., 2008; Medzhitov, 2007). In myeloid cells, several different PRRs have been associated with the recognition of C. albicans and other fungi, including mannose receptor (MR), toll-like receptor (TLR)2, TLR4 and dectin-1 (Netea et al., 2006; Netea et al., 2008). Activation of these receptors either individually or in combination leads to an effector response involving secretion of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, as well as enhanced phagocytosis of pathogens (Kennedy et al., 2007). This process is dependent on several different signaling pathways, including NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which modulate gene transcription through various transcription factors including c-Jun (AP-1) and NF-κB (Lee and Kim, 2007). In bacterial infection, stimulation of myeloid cells also leads to the activation of several downstream proteins involved in regulating these signaling pathways, including the MAPK phosphatase MKP1 (Wang and Liu, 2007; Zhao et al., 2006). Likewise, epithelial cells generate immune-based effector responses to different microbes (Abreu et al., 2005); however, little is known with regard to how the epithelium responds to C. albicans.

Previously we identified a novel immune mechanism in which human epithelial TLR4 could directly protect oral mucosal surfaces from infection with C. albicans via a process dependent on polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) (Weindl et al., 2007). This was the first description of such a PMN-dependent TLR4-mediated protective mechanism at epithelial surfaces and provided significant insights into how microbial infections might be managed and controlled in the oral mucosa. The key event initiating the whole protective process is the induction of an epithelial proinflammatory response by C. albicans. However, the mechanism by which this effector response is initiated is unknown.

In this study, we show that infection of oral epithelial cells with C. albicans leads to activation of both the NF-κB and MAPK pathways, which orchestrate the effector response via the production of proinflammatory mediators. The MAPK pathway is activated in a bi-phasic manner, which involves MKP1 and c-Fos transcription factor, and permits discrimination between the yeast and hyphal forms of C. albicans. Furthermore, MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos activation is dependent upon fungal burdens and thus may constitute a `danger response' mechanism alerting the host to when this normally commensal organism has turned into a potentially dangerous invading pathogen.

RESULTS

Activation of the NF-κB pathway

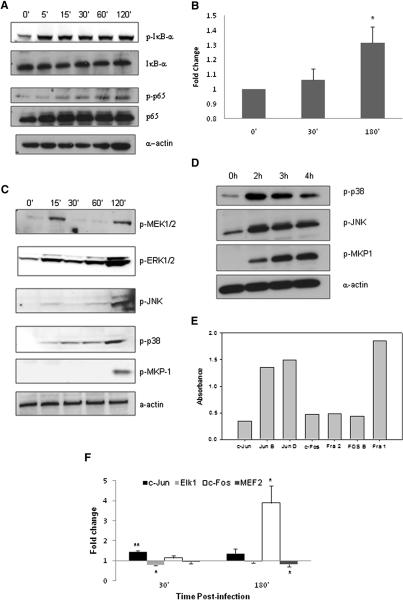

Immunoblot analysis of C. albicans-infected TR146 oral cells confirmed that IκB-α phosphorylation, a key event in NF-κB pathway activation, occurs as early as 5 min post-infection and persists over a 2 h period (Fig. 1a). Likewise, levels of phosphorylated p65 protein increase steadily over the first 2 h of infection. To verify that protein phosphorylation represents an increase in the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, we used the TransAM transcription factor ELISA to determine the DNA binding activity of all NF-κB proteins (p65, p50, c-Rel, p52, RelB). Only the binding activity of p65 increased from the point of infection (mirroring IκB-α phosphorylation), with a significant increase over resting levels (1.3 fold, p<0.05) by 3 h post-infection (Fig. 1b). These data demonstrate that NF-κB signaling via p65/p50 heterodimers is the predominant mechanism induced in oral epithelial cells by C. albicans.

Figure 1. C. albicans infection of TR146 epithelial cells activates NF-κB and MAPK signaling.

(a) Increasing phosphorylation of IκB-α and p65 from 5 min post-infection onwards. Bands are shown relative to unphosphorylated protein and α-actin loading control. (b) Transcription factor DNA binding activity of p65 after C. albicans infection as measured by TransAM ELISA. (c) Increased phosphorylation of MEK1/2, ERK1/2, JNK and p38 after 15 min post-infection, with further phosphorylation at 2 h indicating a bi-phasic response. Also, phosphorylation of MKP1 only at 2 h post-infection, indicating stabilization of the MAPK response. (d) Decreasing levels of p38 and JNK phosphorylation after 2 h infection, matching with increasing levels of MKP1 phosphorylation. (e) Levels of DNA binding activity (absorbance values) of AP-1 transcription factor members in resting TR146 cells. (f) Changes in binding activity of c-Fos, c-Jun, Elk1 and MEF2 after infection; data represented as fold change relative to resting cells. A C. albicans:epithelial cell MOI of 10:1 was used. Data are (a,c–e) representative of three independent experiments or mean of at least three (b) or six (f) independent experiments +/− SEM. * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01. (Two bands are seen for ERK1/2 and JNK as two different proteins make up these complexes). See also Figure S1.

Activation of the MAPK pathway

Unlike the dynamics observed for NF-κB activation, immunoblot analysis of C. albicans-infected TR146 cells indicated a bi-phasic response for the phosphorylation of JNK and p38, and particularly ERK1/2 and MEK1/2 (a MAP2K upstream of ERK1/2) (Fig. 1c). Initially, phosphorylation increased from resting levels at 15 min, and then either subsided (MEK1/2, ERK1/2) or plateaued (p38, JNK). There then followed an increase in phosphorylation at 2 h post-infection for all MAPK proteins. We next explored downstream MAPK-induced events by investigating MKP1 (DUSP1) stabilization. MKP1 is a key phosphatase involved in a negative feedback loop regulating the MAPK pathway (Liu et al., 2007) and is phosphorylated by ERK1/2 to prevent its degradation. This event is independent of gene transcription and is mediated by ERK1/2 (Brondello et al., 1999). Interestingly, phosphorylated MKP1 only appeared at 2 h post-infection, coinciding with the second, stronger MAPK response, providing further support for the bi-phasic response hypothesis (Fig. 1c). Infection of OKF6-TERT2 cells (an immortalized oral epithelial line rather than a carcinoma line) gave identical kinetics of MKP1 phosphorylation (Fig. S1), indicating that this phenomenon is not specific to carcinoma cells. Importantly, commensurate with its function as p38/JNK phosphatase, as levels of phosphorylated MKP1 increase after 2 h so levels of phosphorylated p38 and JNK decrease (Fig. 1d).

MAPK signaling is associated with activation of the AP-1 transcription factor complex, which is a heterodimer of a Jun family member (JunB, JunD, c-Jun) and a Fos family member (Fra1, Fra2, c-Fos, and FosB) (Shaywitz and Greenberg, 1999; Wisdom, 1999). In resting oral cells, DNA binding activity is present for all members of the Jun and Fos families (Fig. 1e). However, 30 min infection with C. albicans results in a significant 1.5 fold increase in c-Jun binding (p<0.001) (Fig. 1f), which returns to baseline levels by 3 h. In contrast, c-Fos binding is strongly upregulated (3.9-fold; p<0.02) but only at 3 h post-infection (Fig. 1f). None of the other Jun or Fos family proteins showed a significant change in binding activity (data not shown). As well as the AP-1 family, we investigated the binding activity of other MAPK-induced transcription factors, including c-Myc, ATF2, Elk-1 and MEF2. Elk-1 binding demonstrated a significant decrease in binding at 30 min post-infection (1.3 fold, p<0.05), which then returned to resting levels by 3 h, whilst, in contrast, MEF2 binding showed no early change but a significant decrease after 3 h (1.5 fold, p<0.05) (Fig. 1f). Binding activity of ATF2 and c-Myc was unchanged at both time points (data not shown). The data demonstrate that oral epithelial cells direct a specific and organized response to C. albicans, whereby opposing changes in transcription factor binding activity are mirrored at 30 min (c-Jun and Elk-1) and 3 h (c-Fos and MEF2) post-infection. This differential activity at the transcription factor level parallels the bi-phasic MAPK response observed at the signal pathway level.

Functional role of NF-κB and MAPK pathways in inducing epithelial effector responses

To determine the functional role of the NF-κB and MAPK pathways in inducing effector cytokine responses, we inhibited the respective pathways 4 h prior to infection with C. albicans. Inhibition of NF-κB with BAY11-7082 (IκB-α inhibitor) resulted in significantly decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1α: 46%, p<0.001; IL-6: 72%, p<0.05; and G-CSF: 79%, p<0.05) (Fig. S2a). Inhibition of JNK (SP600125) leads to a decrease in G-CSF (41%, p<0.001), IL-6 (15%, p<0.05), IL-1α (54%, p<0.01) and IL-1β (67%, p<0.001) (Fig. S2b). Inhibition of p38 (SB203580) results in downregulation of G-CSF (33%, p<0.05), GM-CSF (45%, p<0.001), IL-1α (43%, p<0.001) and IL-1β (38%, p<0.001) (Fig. S2c). Inhibition of ERK1/2 (FR180204) results in a decrease in GM-CSF only (36%, p<0.01) (Fig. S2d). Well documented IC50 concentrations were used for all inhibitors, which have minimal off-target effects.

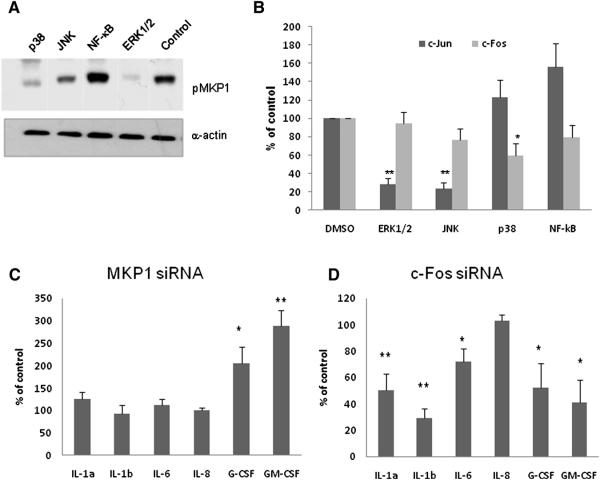

As MKP1 and c-Fos activation constituted the second stage of the bi-phasic MAPK response, we identified the pathways responsible for their activation. Inhibition of NF-κB did not decrease activation of either protein (Fig. 2a and b). In contrast, inhibition of any MAPK protein, but particularly ERK1/2, resulted in reduced MKP1 phosphorylation (ERK1/2 > p38 > JNK) (Fig. 2a), confirming that regulation of MKP1 activity is predominantly by ERK1/2. Likewise, c-Jun activation is induced via the ERK1/2 and JNK pathways (Fig. 2b). However, c-Fos activation was predominantly under the control of p38 (Fig. 2b). Given the potential importance of both MKP1 and c-Fos in the epithelial response to C. albicans we investigated the role of each protein following knockdown with siRNAs. MKP1 (Kinney et al., 2008) and c-Fos (Chambellan et al., 2009) siRNAs were quality controlled previously; however, knockdown efficiency was confirmed by qPCR and Western blotting, with cell viability after siRNA transfection was similar to the viability of control cells (Fig. S3). Knockdown of MKP1 resulted in a significant increase in the level of G-CSF (206%, p<0.05) and GM-CSF (289%, p<0.01) production (Fig. 2c), which was as expected given that MKP1 modulates the MAPK pathway by selectively dephosphorylating p38 and JNK. Knockdown of c-Fos resulted in significant reduction in the levels of IL-1α (50%, p<0.01), IL-1β (81%, p<0.01), IL-6 (28%, p<0.05), G-CSF (47%, p<0.05) and GM-CSF (59%, p<0.05) (Fig. 2d), suggesting that c-Fos is the main transcription factor controlling MAPK-induced activation of the proinflammatory response. Together, these data indicate that C. albicans elicits effector responses in oral epithelial cells via NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, with the latter controlling MKP1 and c-Fos activation.

Figure 2. Regulation of MKP1, c-jun, c-Fos and cytokine activation.

(a) Levels of MKP1 phosphorylation 2 h after C. albicans infection (MOI = 10) in TR146 cells after inhibition of different pathways. (b) Level of inhibition of c-Jun (30 min) and c-Fos (3 h) DNA binding activity after pretreatment for 4 h with signaling pathway inhibitors. (c and d) Effect of MKP1 and c-Fos knockdown, respectively, on cytokine production (MOI of 0.01). Data are expressed as percentage of vehicle control levels (b–d) and are representative of three independent experiments (a) or are the mean of four independent experiments +/− SEM (b–d). * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001. See also Figure S2 and S3.

MKP1, c-Fos and cytokine activation is dependent on C. albicans morphology

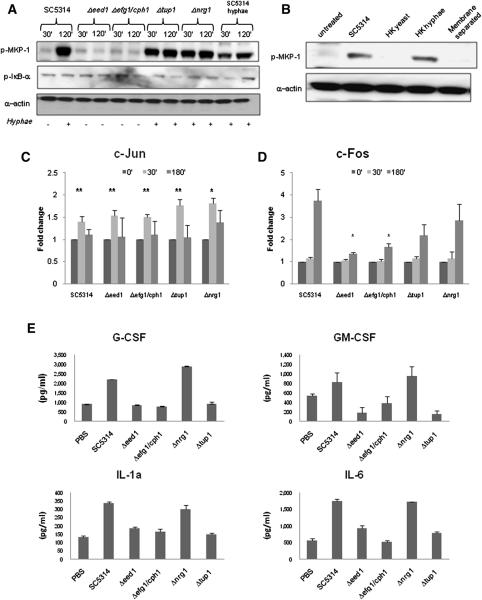

C. albicans infection of oral epithelial cells results in yeast-to-hyphal transition within the first hour. Given that hypha formation plays an important role in mucosal pathogenicity (Naglik et al., 2006; Zakikhany et al., 2007; Naglik et al., 2008), we hypothesized that the second stage (2 h) of the bi-phasic MAPK response, constituting MKP1 and c-Fos activation, might be due to a specific response to filamentation. To test this, we infected TR146 cells with wild-type C. albicans (SC5314) and four mutants: Δefg1/cph1 (unable to form hyphae); Δeed1 (severely restricted filament formation in the first ~3 h, after which reverts back to the yeast phase); Δtup1 (hyperfilamentous but locked in the pseudohyphal phase); Δnrg1 (hyperfilamentous hyphae) for 30 min and 2 h and tested for MKP1 phosphorylation and c-jun and c-Fos binding. The morphological form of these mutants at the same 30 min and 2 h assay time points is shown in Fig. S4. Only the hyperfilamentous mutants (Δtup1 and Δnrg1) induced MKP1 phosphorylation at 30 min and 2 h, whereas neither of the non-filamentous mutants (Δeed1 and Δefg1/cph1) induced MKP1 phosphorylation at either time point (Fig. 3a) (or at 3 h post-infection (Fig. S5)). As previously, SC5314 wild type induced MKP1 phosphorylation only at 2 h when hypha formation was evident. When wild-type cells were pre-induced to form germ tubes for 3 h prior to epithelial infection (SC5314 hyphae), MKP1 phosphorylation was observed at the early 30 min time point as well as 2 h (Fig. 3a). In all cases, there was no difference between the strains in the kinetics of IκB-α phosphorylation (Fig. 3a), indicating that NF-κB pathway activation is independent of the morphological form. Physical separation of C. albicans from epithelial cells with a porous membrane (0.4 μm) resulted in a complete loss of MKP1 phosphorylation, indicating that MKP1 activation is not a result of secreted factors but is contact-dependent (Fig. 3b). Induction of MKP1 phosphorylation was also induced by heat-killed hyphae but not heat-killed yeast, indicating that MKP1 activation is hypha-dependent but does not necessarily require viability (Fig. 3b). The data demonstrate that MKP1 phosphorylation is the result of contact-dependent hypha recognition.

Figure 3. Specific activation of MKP1 and transcription factors and cytokine induction by C. albicans.

(a) Immunoblot of phosphorylated MKP1 and IκB-α after infection of TR146 cells with wild-type (SC5314), hyperfilamentous (Δtup1 and Δnrg1), and non-filamentous (Δeed1 and Δefg1/cph1) strains, or pre-grown C. albicans hyphae. The morphological status of the strains at each time point is indicated below the immunoblots (presence (+) or absence (−) of filaments). (b) Induction of MKP1 phosphorylation at 2 h using heat-killed (HK) wild-type (SC5314) yeast or hyphae or by SC5314 prevented from direct contact with epithelial cells by a 0.4 μm membrane. We also show changes in binding activity of c-Jun (c) and c-Fos (d) at 30 min and 3 h infection with non-filamentous (Δeed1 and Δefg1/cph1) or hyperfilamentous (Δtup1 and Δnrg1) mutants. (e) Induction of cytokines after 24 h infection with non-filamentous (Δeed1 and Δefg1/cph1) or hyperfilamentous (Δtup1 and Δnrg1) mutants. An MOI of 10 was used for infections in (a–d) whilst an MOI of 0.01 was used for (e). Data are (a & b) representative of three independent experiments, (c & d) mean of four experiments (+/− SEM) or (e) representative of three experiments. * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01. See also Figure S4, S5 and S6.

We next investigated c-Jun (30 min - first MAPK response) and c-Fos (3 h - second MAPK response) activation to determine whether the hypha-associated bi-phasic MAPK response was mirrored at the transcription factor level. All four mutants activated c-Jun to a similar degree indicating that activation of the first MAPK phase was independent of the morphological form (Fig. 3c). In contrast, compared with the wild-type strain (SC5314), there was a significant reduction in c-Fos activity in the Δeed1 and Δefg1/cph1 non-filamentous mutants (p<0.05) but not the hyperfilamentous Δtup1 and Δnrg1 mutants (Fig. 3d), although neither Δtup1 nor Δnrg1 induced c-Fos activity as high as the wild-type. The reduced levels of c-Fos activation at 3 h between the two hyperfilamentous mutants and the SC5314 wild-type can be explained partly by the reduced level of adherence between the two strains (Fig. S6) and partly by the lack of fungal-epithelial cell contact i.e. the wild-type yeast cells settled rapidly onto the epithelial surface prior to hypha formation, whereas the hyperfilamentous strains `floated' for a prolonged period of time before gradually settling, thus reducing the MOI and threshold level of activation. Furthermore, both heat-killed hyphae and yeast activated c-Jun, whereas only heat-killed hyphae activated c-Fos, albeit to a lesser degree than viable hyphae (data not shown).

This indicates that although viability and cell damage induced by hyphae is not essential to induce c-Fos activity, viability further activates c-Fos and the presence of the filamentous form is required. Finally, neither of the non-filamentous mutants induced cytokine production (Fig. 3e; GM-CSF production appears to decrease but this was not significant or reproduced with the other cytokines). Interestingly, of the hyperfilamentous mutants, only Δnrg1 and not Δtup1 induced increases in cytokines, suggesting that cytokine production is, in part, independent of MAPK-induced c-Fos activation (i.e. probably NF-κB mediated). Treatment of cells with heat-killed yeast or hyphae failed to induce cytokine secretion at an MOI of 10 after 24 h (data not shown).

Given that Δtup1 is thought to be locked in the pseudohyphal phase, but still activated MKP1, we tested whether Δtup1 expresses genes known to be associated with hypha formation. Near identical expression levels of ECE1 and HYR1 (hypha-specific marker genes) was observed in Δtup1, Δnrg1 and SC5314 wild type after 2 h growth in cell culture medium (same time points used to assess MKP1 and c-Fos activation) as compared with the non-filamentous mutants Δeed1 and Δefg1/cph1 (data not shown). This suggests that Δtup1 may activate MKP1 via similar surface moieties as Δnrg1 and SC5314 wild type hyphae, even though Δtup1 is locked in the pseudohyphal phase. We conclude that MKP1 is activated through epithelial recognition of moieties associated with C. albicans filamentation.

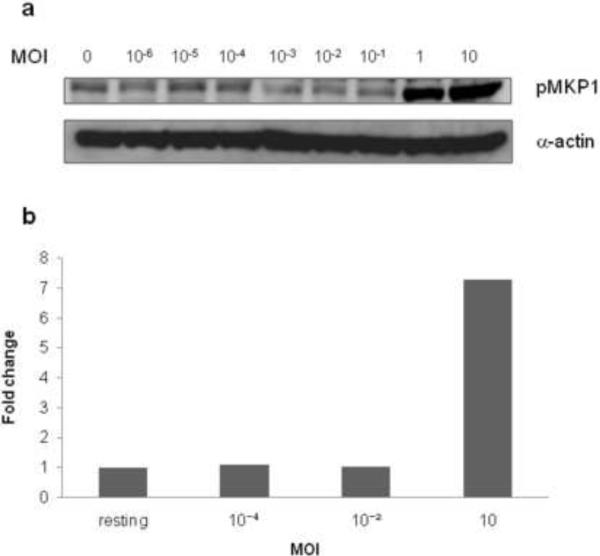

MKP1, c-Fos and cytokine activation is dependent on fungal burden

Clinically, apart from classical signs and symptoms of infection, oral candidiasis is associated with fungal burdens two or three logs higher than that observed during colonization (Naglik et al., 1999; Naglik et al., 2003). To determine whether induction of MKP1, c-Fos and cytokines required a threshold level of activation, we stimulated oral cells with different doses of C. albicans SC5314 (101–107 cells/ml). This was equivalent to a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.00001–10 C. albicans cells per epithelial cell. MKP1 and c-Fos were only activated at an MOI of 1 or above, indicating that each epithelial cell is able to recognize, respond and discriminate against a single fungal cell (yeast or hyphal) (Fig. 4a and b).

Figure 4. Effect of fungal burdens on MKP1 and c-Fos activation.

Induction of (a) MKP1 phosphorylation and (b) c-Fos DNA binding activity by differing fungal burdens. An MOI of 1 or higher is required to activate the second MAPK phase. Wild-type SC5314 C. albicans was added as yeast cells at each MOI and infections were left for (a) 2 h or (b) 3 h in each case. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

The MAPK discriminatory response is Candida specific but independent of structural cell wall polysaccharides and adherence

Given the important role of hypha formation in inducing the MAPK bi-phasic response by C. albicans, we investigated whether similar responses were induced by the non-pathogenic fungus S. cerevisiae, which does not produce hyphae in our system. Only C. albicans and not S. cerevisiae induced MKP1 phosphorylation and c-Fos activation (Fig. 5a and b) at an MOI of 10, indicating that MKP1 and c-Fos activation is associated specifically with responses to pathogenic fungi. Of note, IκBα phosphorylation was similar between the two fungal species (Fig. 5a), indicating that NF-κB activation is not only independent of morphology but also likely to be a general response to fungi.

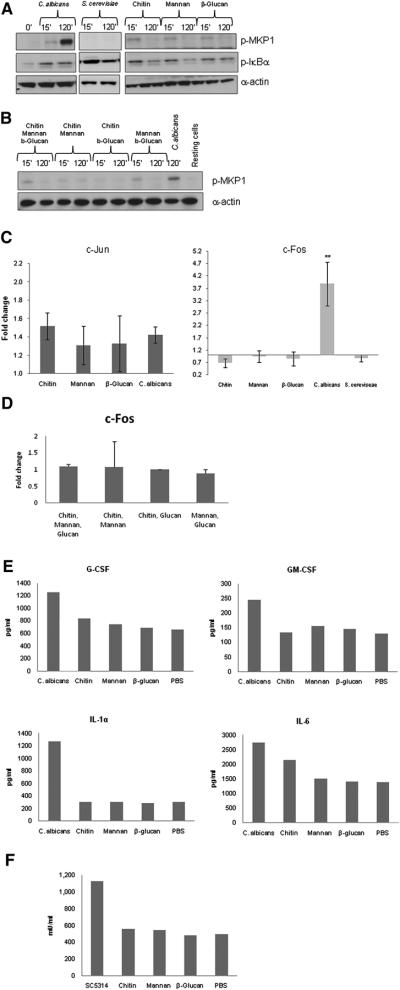

Figure 5. Activation of MKP1 and c-Fos by C. albicans and S. cerevisiae and epithelial responses to fungal cell wall components.

(a–b) Phosphorylation of MKP1 and IκBα after 2 h or (c–d) activation of c-Jun and c-Fos DNA binding activity after 30 min and 3 h of infection, respectively, with either C. albicans or S. cerevisiae or treatment with 2 μg/ml C. albicans chitin, 50 μg/ml C. albicansN- and O- mannan or 100 μg/ml β-glucan microspheres (individually or in combination) for the same time periods. Only C. albicans activates MKP1 and c-Fos. (e) Moiety-induced cytokine production after 24 h as measured by multiplex microbead assay. (f) Moiety-induced damage as measured by LDH release after 24 h. Doses for (b–d) were the same as those for (a). All experiments are (a–b) representative of or (c–e) the mean of at least three independent experiments. An MOI of 10 was used for both species. * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01.

Since S. cerevisiae and C. albicans yeast and hyphae share common structural components, we next determined whether specific cell wall polysaccharides were able to activate the discriminatory mechanism. Stimulation of oral cells with purified C. albicansN- and O-mannans, chitin and β-glucan microparticles (gift from David Williams) resulted in activation of NF-κB (IκB-α) (Fig. 5a) and the first MAPK response (30 min: c-Jun) (Fig. 5c). However, none of these fungal components activated the second MAPK response (MKP1/c-Fos), cytokine production or cell damage (Fig. 5a,c, e & f). Combinations of these structural moieties were also unable to either induce MKP1 phosphorylation or increase c-Fos activity (Fig 5b,d). This demonstrates that fungal cell wall polysaccharides are unlikely to be responsible for activating either the proinflammatory response or the filamentation-associated discriminatory mechanism in oral epithelial cells.

It is well known that C. albicans hyphae adhere better to many surfaces than yeast cells. However, induction of the MAPK discriminatory response (MKP1/c-Fos) was independent of the ability of yeast and hyphal forms to adhere to oral cells (Fig. S6). Neither of the non-filamentous mutants (Δeed1 and Δefg1/cph1) activated MKP1 and c-Fos, but Δeed1 adhered as well as the wild-type strain (SC5314). Likewise, both the hyperfilamentous mutants (Δnrg1 and Δtup1) activate MKP1 and c-Fos, but Δnrg1 adhered much better than Δtup1. Finally, a clinical strain (C. albicans 529L) that does not produce true hyphae (see later) adhered to oral epithelial cells to the same degree as C. albicans SC5314 (hyphal producer), yet only SC5314 activated MKP1 and c-Fos.

The MAPK discriminatory response and receptor induction

TLR2, TLR4, MR and dectin-1 are the pattern recognition receptors known to initiate antifungal responses in myeloid cells (Netea et al., 2008). As shown earlier, neither β-glucan nor mannan (the ligands for dectin-1 and MR, respectively) induced epithelial effector responses. Also, although present, SYK was not phosphorylated by C. albicans (Fig. S8) and thus dectin-1/SYK signalling has not been induced. These data indicate that dectin-1 and MR are unlikely to play any part in mediating discriminatory responses to C. albicans. Additional blocking of TLR2 and TLR4 activation using neutralizing antibodies also indicated no role for these receptors in c-Fos activation (Fig. S7). Furthermore, siRNA knockdown of TLR2 and TLR4 showed no alterations in MKP1 phosphorylation compared with control siRNA after C. albicans infection (Fig. S7). We conclude that the second MAPK response enabling epithelial discrimination between C. albicans yeast and filamentous forms in independent of canonical PRR activation and is probably mediated via as yet uncharacterized or potentially unique receptor-based detection mechanisms.

The MAPK discriminatory response may dictate whether C. albicans colonizes a mucosal surface in vivo

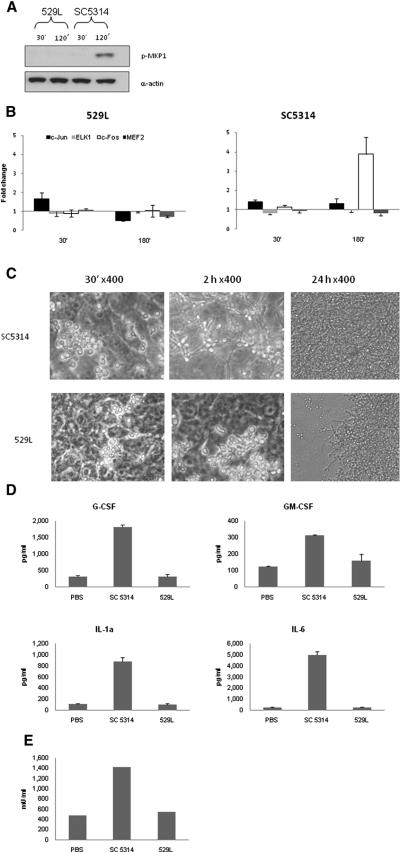

The MAPK discriminatory response was identified using two separate cell lines (TR146 and OKF6-TERT2). We thus sought to confirm in vivo relevance using two approaches. First, previously we established a murine model of concurrent oral and vaginal C. albicans colonization, where we identified a differential ability of C. albicans strains to colonize both mucosae (Rahman et al., 2007). The best colonizing C. albicans strain 529L (human isolate from the oral cavity of a carrier individual) and the non-colonizing wild-type strain SC5314 were chosen as representative strains to determine whether the ability to colonize a mucosal surface in vivo may be related to hypha formation and the bi-phasic MAPK response. When added to TR146 cells both strains phosphorylated IκB-α equally efficiently (data not shown) but unlike SC5314, 529L was unable to induce MKP1 phosphorylation (Fig. 6a) or increase c-Fos binding activity, even though binding activity for c-Jun, ELK-1 and MEF2 was identical to the SC5314 strain (Fig. 6b). Microscopic examination revealed that 529L was severely restricted in hypha formation in the presence of epithelial cells at 30 min and 2 h, and after 24 h manifested as yeasts and/or pseudohyphae (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, unlike SC5314, 529L also failed to induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 6d) or to cause damage (Fig. 6e) after 24 h infection.

Figure 6. Activation of the bi-phasic MAPK response may be required for colonization in a murine model.

(a) Immunoblot analysis of MKP1 phosphorylation and (b) changes in transcription factor binding activity after infection with C. albicans SC5314 (non-colonizing) and 529L (colonizing). (c) Morphology of C. albicans strains on epithelial cells after 30 min, 2 h and 24 h. (d) Secretion of cytokines after infection with C. albicans 529L and SC5314 for 24 h. An MOI of 10 was used for (a) and (b) and an MOI of 0.01 for (d) and (e). Data are (a,c) representative of three independent experiments or (b, d, e) mean of three independent experiments +/− SEM.

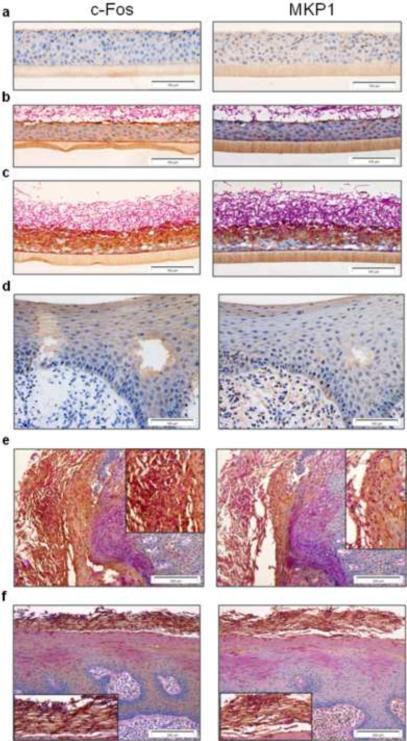

Second, we determined the presence of MKP1 and c-Fos in organotypic models of oral reconstituted human epithelium (oral RHE) and in biopsies from two patients with oral Candida infections. There was minimal expression of either c-Fos or MKP1 in uninfected oral RHE (Fig. 7a). However, after 4 h of C. albicans infection, surface activation of c-Fos and MKP-1 can be observed (dark brown staining) in regions of hyphal contact with epithelial cells (Fig. 7b). After 24 h there was significant hyphal penetration of the model (PAS staining), which was associated with significantly increased expression of both MKP1 and c-Fos in epithelial cells (Fig. 7c). A clear delineation was observed with cells in contact with hyphae showing expression of both MKP1 and c-Fos, whilst cells in adjacent uninfected areas showing little increase in MKP1 and c-Fos expression.

Figure 7. Expression of c-Fos and MKP1 in oral epithelium.

(a) Resting expression of c-Fos and MKP1 in oral RHE. Upregulation of c-Fos and MKP1 expression is associated with contact with Candida hyphae at (b) the surface after 4 h and (c) throughout the epithelial layer when hyphae penetrate and invade at 24 h (dark brown staining). (d) Resting expression levels of c-Fos and MKP1 in control biopsies of human oral epithelium. (e and f) Increased expression of both c-Fos and MKP1 in two different oral biopsies with Candida infection (panel e: left and panel f: top; dark brown staining). Insets in (e) and (f) show an enlarged view of the region of Candida infection in each respective biopsy.

In control, uninfected human biopsies, c-Fos was expressed at low resting levels but only in the upper layers of the epithelium (and not the underlying connective tissue) (Fig. 7d). However, in two separate oral biopsies with Candida infection, there was a distinctly visible increase in both MKP1 and c-Fos expression (Fig. 7e–f; dark brown staining), demonstrating that MKP1 and c-Fos constitute part of the oral epithelial response to Candida hyphal invasion during human mucosal infection in vivo. We conclude that MAPK signaling, MKP1 and c-Fos activation play a central role in the discrimination of C. albicans yeast and hyphae in epithelial cells, which may have important implications for how the human host responds to and controls C. albicans mucosal infections in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Host mechanisms enabling discrimination between commensal and pathogenic organisms are critical in mucosal immune defense and homeostasis. Of particular interest are opportunistic microbes, like C. albicans, that can act as either commensals or pathogens under suitably predisposing conditions. We and others have previously shown that hypha formation is crucial for C. albicans pathogenicity and induction of proinflammatory responses at mucosal surfaces (Zakikhany et al., 2007; Korting et al., 2003), which results in PMN-dependent TLR4-mediated protection against subsequent fungal infection (Weindl et al., 2007). Given that the key event initiating this protective process appears to be the C. albicans hypha-induced proinflammatory response, we sought to identify the epithelial mechanisms that discriminate between the yeast and hyphal forms of C. albicans. We report that specific MAPK-based recognition of the filamentous form appears to initiate a `danger response' mechanism constituting MKP1 and c-Fos activation via a process dependent on fungal burdens. Activation of this mechanism may inform the host of when this normally commensal fungus has become invasive (pathogenic), which may have important implications for mucosal fungal infections in vivo.

Infection of oral epithelial cells with C. albicans results in the activation of NF-κB and a biphasic MAPK signaling response, which leads to the induction of a proinflammatory response. Although the activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling by C. albicans is not unexpected as these pathways are activated in myeloid cells (Roeder et al., 2004), the identification of a bi-phasic MAPK response in epithelial cells that is morphology and burden dependent is novel. Activation of NF-κB and the first MAPK phase appears to be independent of the morphological form and are likely due to the recognition of general fungal cell wall structures. These include chitin, mannans and β-glucans, as all three moieties activated NF-κB and the first MAPK phase but not the second MAPK phase. Also, activation of the first MAPK phase does not necessarily result in cytokine induction, as this was readily activated by killed C. albicans yeast and hyphae, fungal cell wall agonists and S. cerevisiae, all of which were non-immunostimulatory. This is in contrast to myeloid cells where strong inflammatory responses are induced by killed C. albicans and fungal agonists (Netea et al., 2006; Netea et al., 2008), indicating that different (or more regulatory) innate response mechanisms exist in epithelial cells. We propose that activation of NF-κB and the first MAPK phase is independent of morphology and constitutes a general epithelial response to inform the host of the presence of fungus or fungal cell wall components.

The second MAPK response involves two key proteins, the MAPK phosphatase MKP1 and the transcription factor c-Fos, and is a specific response to the presence of pathogenic fungus (i.e. C. albicans). MKP1 activation is mediated via the MEK1/2 - ERK1/2 pathway, is associated with filamentation and is contact-dependent, but is independent of viability and avidity of adherence. The hypha-associated moieties that induce MKP1 activation are unknown but cell wall structural components (mannans, chitin and β-glucans) are unlikely to be the activating factors, as these only activate NF-κB and the first MAPK phase. We propose that MKP1 is activated via cell surface moieties present on filamentous forms of C. albicans.

Activation of c-Fos is mediated via the p38 pathway and is also hypha-associated, but c-Fos is activated via two independent mechanisms. The first mechanism does not require fungal viability and is probably activated via hypha-associated surface moieties, much like MKP1. The second mechanism is associated with the induction of inflammatory mediators, since c-Fos knockdown significantly reduced cytokine release after C. albicans infection, and is likely associated with hyphal invasion/penetration and induction of cell damage (as viability promoted c-Fos activation). Our data contrasts with that of myeloid cells where c-Jun rather than c-Fos is thought to play the dominant role in mediating responses to C. albicans (Roeder et al., 2004), and further supports the notion that epithelial response mechanisms to fungal pathogens are distinct to those of myeloid cells.

Together, our data suggest that different hypha-associated moieties are required to induce (a) the epithelial MAPK/MKP-1/c-Fos pathway and (b) the cytokine response. This may explain the differences we observed between the two filamentous mutants, in that Δtup1 might possess one set of surface moieties that activate the MAPK/MKP-1/c-Fos response but lacks another set that results in poor adhesion, lack of invasion, and weak cytokine production. On the other hand, Δnrg1 may possess both sets of surface moieties, similar to the SC5314 wild-type, and is therefore capable of inducing both the MAPK/MKP-1/c-Fos and the cytokine response. Tup1 and Nrg1 regulated genes have been partially identified (Murad et al., 2001a) and recently a set of genes was proposed as mediating hyphal virulence independently of morphology (Nobile et al., 2008). Those studies provide several interesting candidates with regard to determining which hyphal moieties might induce the MAPK/MKP-1/c-Fos and cytokine response in epithelial cells.

Although MKP1 and c-Fos activation constitute the second MAPK response, they do not appear to be directly linked as MKP1 is activated by ERK1/2 and c-Fos by p38. However, the function of MKP1 is to dephosphorylate p38 (and JNK) (Zhao et al., 2006; Chi and Flavell, 2008) in order to stabilize and regulate the overall MAPK network. This is highlighted by an increase in cytokine release (G-CSF, GM-CSF) after MKP1 knockdown or inhibition, as there will be reduced dephosphorylation of p38 (and JNK) which results in an increased effector response (as cytokine induction is primarily mediated via p38 and JNK). In the context of a fungal infection, MKP1 activation will ensure that any immune response to C. albicans hyphae is both optimal and tightly controlled, whilst concurrently ensuring a rapid de-activation of potential deleterious p38- and JNK-mediated inflammatory responses when no longer being driven by recognition of hyphae. Given that phosphorylation and stabilization of MKP1 is mediated by ERK1/2 activity, our data implies that ERK1/2 plays an important role in the control and resolution of inflammatory responses by regulating the level of cytokine secretion due to p38 and JNK signaling, rather than by direct effects on cytokine production.

This MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos pathway may be important in vivo since a C. albicans strain (529L) that does not form hyphae or activate MKP1, c-Fos or cytokine production is able to colonize a murine model, whereas a C. albicans strain (SC5314) that readily forms hyphae and strongly activates MKP1, c-Fos and cytokine production is efficiently cleared (Rahman et al., 2007). Likewise, increased levels of MKP1 and c-Fos expression are evident in organotypic models and human biopsies taken from Candida-infected individuals. Although we were unable to utilize primary normal oral keratinocytes in our studies, the in vitro data using cell lines appears to be directly applicable to the in vivo situation and suggests that avoidance or activation of this MAPK-based `danger response' mechanism may be crucial in determining whether a fungal strain colonizes, infects or is cleared by the host.

Recognition of C. albicans by monocytes/macrophages is mediated by several different PRRs including mannose receptor, TLR2, TLR4 and dectin-1 (Netea et al., 2006). Likewise, in dendritic cells the initiation of an ERK1/2 – c-Fos response is the result of TLR2 and dectin-1 signaling (Agrawal et al., 2003; Dillon et al., 2004; Dillon et al., 2006). We show that the MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos signaling mechanism in epithelial cells is unlikely to utilize the same receptors, as knockdown of TLR2 and TLR4 did not affect MKP1 or c-Fos activation or the cytokine profile. Likewise, SYK (the adapter utilized by dectin-1) was not activated and β-glucans (the ligand for dectin-1) did not induce cytokine responses. It has been reported that the surface receptor CDw17 may mediate epithelial responses to Candida (Li and Dongari-Bagtzoglou, 2009); however, this was against C. glabrata which does not form hyphae. Therefore, it is likely that the MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos system that mediates yeast/hyphal discrimination is through as yet unidentified epithelial PRR(s).

Of major importance is that MKP1 and c-Fos activation is dependent not only on filamentation but also on fungal burdens, and suggests that a threshold level of stimulation is required prior to full activation of the epithelial innate immune response. This may provide a mechanism by which epithelial tissues can remain quiescent in the presence of low fungal burdens (even if hyphae are present) whilst responding specifically and strongly to damage-inducing hyphae as burdens increase. Therefore, in addition to identifying the switch from the yeast to hyphal form in C. albicans, the MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos pathway may also constitute a `danger response' mechanism informing the host of potentially dangerous levels of this fungal pathogen. We propose that at low burdens C. albicans avoids activating the MAPK-based danger response pathway as a threshold level of activation is not reached. As a result, the fungus is regarded as `non-dangerous', thereby permitting successful colonization of human mucosal surfaces without host challenge. One could regard this as C. albicans being in the `commensal' state. However, under conditions that permit fungal proliferation, increased fungal burdens together with associated hypha formation activate the MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos pathway to warn the host of the presence of a `dangerous' pathogen. This results in immune activation and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn (as we have previously shown) results in PMN recruitment and fungal clearance or reduction of fungal burdens back down below the threshold level of activation, and thus a return to the non-activatory colonization `commensal' state (Weindl et al., 2007). In the clinical setting, fungal proliferation and immune activation may translate into signs and symptoms of infection, and the cycle of immune activation (based on fungal burdens and hypha formation) followed by subsequent clearance may represent what occurs in patient groups that experience acute C. albicans infections.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell lines, reagents and Candida strains

Experiments were carried out using the TR146 buccal epithelial carcinoma cell line or OKF6-TERT2 immortalized oral cell line. Monolayer cultures were grown in DMEM/10% FBS and experiments carried out in serum-free DMEM. Oral reconstituted human epithelium (RHE: 5-day) was purchased from SkinEthic Laboratories and used as previously described (Schaller et al., 2006). ERK (FR180204; 750nM), JNK (SP600125; 10 μM), p38 (SB203580; 10 μM), and NF-κB (BAY11-7082; 2 μM) inhibitors were purchased from Calbiochem. Antibodies to phospho-p38, phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-JNK, phospho-MKP1, phospho-MEK1/2 and phospho-IκBα and the MEK1/2 (U0126; 20 μM) inhibitor were purchased from Cell Signalling Technologies (New England Biolabs). Fungal strains included C. albicans wild-type SC5314 (Gillum et al., 1984), 529L (in-house clinical strain), Δtup1 (Braun and Johnson, 1997), Δnrg1 (Murad et al., 2001b), Δeed1 (Zakikhany et al., 2007), Δefg1/cph1 (Lo et al., 1997) and S. cerevisiae (NCPF 3139). C. albicans β-glucans microparticles were a kind gift from David Williams. TLR2 and 4 blocking antibodies were obtained from Invivogen (Autogen Bioclear).

Purification of C. albicans cell wall components

Chitin was purified from C. albicans cell walls as previously described (Gow et al., 1980). O-linked mannans were extracted using 0.1 M NaOH (room temperature for 20 h) and N-linked mannans with 0.1 M NaOAc, pH 5.2, 0.5 U endoglycosidase H (overnight at 37°C). Soluble N- and O-linked mannans were centrifuged, neutralised with either HCl or NaOH, lyophilised, resuspended in deionised water and extensively purified by ion exchange chromatography using AG50W-X12 and AG4 X4 resins (Bio Rad), until protein negative. Polysaccharides yield was determined by acid-hydrolysis with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid (Mora-Montes et al., 2007) and analysed by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) (Plaine et al., 2008). Protein content was quantified with the Coomassie assay (Perbio Science) and confirmed endotoxin free (Limulus amebocyte lysate assay, Hycult Biotech).

RNA extraction and analysis

RNA was isolated from oral epithelial monolayers and RHE using the Nucleospin II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Thermoscientific) and treated with Turbo DNase- (Ambion) to remove genomic DNA. Real-time PCR was performed on cDNA using Jumpstart SYBR green mastermix (Sigma-Aldrich) on a Rotorgene 6000 (Corbett Research). Primers were taken from Primerbank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/)(Wang and Seed, 2003) and are listed in Table S1.

RNA interference

Knockdown of gene expression in cells was performed using previously reported siRNAs for MKP1 (Kinney et al., 2008), c-Fos (Chambellan et al., 2009), TLR2 (Opitz et al., 2006) and TLR4 (Weindl et al., 2007). As a control, a non-silencing siRNA duplex with no homology to known human genes was used as reported previously (Weindl et al., 2007). Transfection of siRNA into epithelial cells was performed overnight using HiPerFect reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's reverse transfection protocol. qPCR and protein analysis demonstrated that transcript levels for targeted genes were reduced by at least 80% of control levels and maintained this level for at least a further 24 h.

Western blotting

Epithelial cells were lyzed using a modified RIPA lysis buffer containing protease (Sigma-Aldrich) and phosphatase (Perbio Science) inhibitors, left on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged for 10 min in a refrigerated microfuge. Supernatants were assayed for total protein using the BCA protein quantitation kit (Perbio Science). 20 μg of protein was separated on 12% NuPAGE Bis:Tris minigels (Invitrogen) before transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare). After probing with primary and secondary antibodies, membranes were developed using Immobilon chemiluminescent substrate (Millipore) and exposed to ECL film (GE Healthcare).

Transcription factor DNA binding assay

DNA binding activity of transcription factors was assessed using the TransAM transcription factor ELISA system (Active Motif). Briefly, nuclear proteins were isolated from epithelial cells using a nuclear protein extraction kit (Active Motif). Protein concentration was determined and 5 μg of nuclear extract was assayed in the TransAM system according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cytokine determination

Cytokine levels in cell culture supernatants was determined using the Fluorokine MAP cytokine multiplex kits (R&D Systems), coupled with the Luminex 100™ machine according to the manufacturer's protocol. The trimmed median value was used to derive the standard curve and calculate sample concentrations.

Epithelial cell damage assay

Epithelial cell damage was determined by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in the culture supernatant using the Cytox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol and using a recombinant porcine LDH (Sigma-Aldrich) to generate a standard curve.

Adherence assay

Candida strains were incubated with epithelial cell cultures for 30 min and 2 h. Supernatants were collected (unattached C. albicans), centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 10 min, and the pellets washed three times with PBS before being plated on Sabouraud's dextrose (SAB) agar and incubated overnight at 37°C. The epithelial cells (with attached C. albicans) were washed and then scraped into 1 ml PBS, before being plated onto SAB agar plates. Colonies per plate were numerated. Percentage adherence was calculated as: number of adherent colonies (from the epithelial cell pellet) / (number of adherent colonies + number of non-adherent colonies (from the supernatant pellet))*100.

Immunohistochemistry of oral RHE and human biopsies

Human biopsy material (paraffin embedded) surplus to diagnostic requirements was obtained from departmental archives and its research use under generic opt-out consent was approved by the Guy's Hospital Research Ethics Committee. C. albicans infected oral RHE was fixed in 10% (v/v) formal-saline before being embedded and processed in paraffin wax using standard protocol. For each human biopsy and oral RHE, 5 μm sections were prepared using a Leica RM2055 microtome and silane coated slides. After dewaxing in xylene, protein expression was determined using rabbit anti-human polyclonal antibodies for MKP1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and c-Fos (Source Bioscience,) (1:10 and 1:100, respectively) and counterstained with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary IgG antibody, followed by diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen detection as per manufacturer's protocol. To visualize C. albicans, sections were stained using Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS), counterstained with haematoxylin and examined by light microscopy.

Statistics

TransAM data was analyzed using a paired t-test, whilst cytokines were analyzed using 2-way equal variance t-test. In all cases, p<0.05 was taken to be significant.

HIGHLIGHTS.

NF-κB and MAPK control epithelial effector responses against Candida albicans.

Fungal hyphae and burdens are crucial in activating the MAPK/MKP-1/c-Fos pathway.

First demonstration of MKP-1 regulating epithelial responses to a fungal pathogen.

MAPK/MKP1/c-Fos activation may identify the commensal-pathogen switch in vivo.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr David Williams for supplying the β-glucan micrparticles; Drs Bernhard Hube, Al Brown, Gerry Fink and Sandy Johnson for supplying C. albicans mutants; and Drs Bernhard Hube, Martin Schaller and Neil Gow for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the NIDCR (DE017514; J.N.) and the Wellcome Trust (080088; H.M-M.). The authors also acknowledge financial support from the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abreu MT, Fukata M, Arditi M. TLR signaling in the gut in health and disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:4453–4460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal S, Agrawal A, Doughty B, Gerwitz A, Blenis J, van Dyke T, Pulendran B. Cutting Edge: Different Toll-Like Receptor Agonists Instruct Dendritic Cells to Induce Distinct Th Responses via Differential Modulation of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase-Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and c-Fos. J Immunol. 2003;171:4984–4989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun BR, Johnson AD. Control of filament formation in Candida albicans by the transcriptional repressor TUP1. Science. 1997;277:105–109. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondello JM, gur J, McKenzie FR. Reduced MAP Kinase Phosphatase-1 Degradation After p42/p44MAPK-Dependent Phosphorylation. Science. 1999;286:2514–2517. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambellan A, Leahy R, Xu W, Cruickshank PJ, Janocha A, Szabo K, Cannady SB, Comhair SA, Erzurum SC. Pivotal role of c-Fos in nitric oxide synthase 2 expression in airway epithelial cells. Nitric. Oxide. 2009;20:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, Flavell RA. Acetylation of MKP-1 and the Control of Inflammation. Sci. Signal. 2008;1:e44. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.141pe44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S, Agrawal A, van Dyke T, Landreth G, McCauley L, Koh A, Maliszewski C, Akira S, Pulendran B. A Toll-Like Receptor 2 Ligand Stimulates Th2 Responses In Vivo, via Induction of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and c-Fos in Dendritic Cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:4733–4743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S, Agrawal S, Banerjee K, Letterio J, Denning TL, Oswald-Richter K, Kasprowicz DJ, Kellar K, Pare J, van Dyke T, et al. Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:916–928. doi: 10.1172/JCI27203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5'-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen. Genet. 1984;198:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00328721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow NAR, Gooday GW, Newsam RJ, Gull K. Ultrastructure of the septum in Candida albicans. Curr Microbiol. 1980;4:357–359. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AD, Willment JA, Dorward DW, Williams DL, Brown GD, DeLeo FR. Dectin-1 promotes fungicidal activity of human neutrophils. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:467–478. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney CM, Chandrasekharan UM, Mavrakis L, DiCorleto PE. VEGF and thrombin induce MKP-1 through distinct signaling pathways: role for MKP-1 in endothelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C241–C250. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00187.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korting H, Hube B, Oberbauer S, Januschke E, Hamm G, Albrecht A, Borelli C, Schaller M. Reduced expression of the hyphal-independent Candida albicans proteinase genes SAP1 and SAP3 in the efg1 mutant is associated with attenuated virulence during infection of oral epithelium. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:623–632. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by innate receptors. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Kim YJ. Signaling pathways downstream of pattern-recognition receptors and their cross talk. Annu. Rev Biochem. 2007;76:447–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060605.122847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Epithelial GM-CSF Induction by Candida glabrata. J Dent Res. 2009;88:746–751. doi: 10.1177/0022034509341266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shepherd EG, Nelin LD. MAPK phosphatases [mdash] regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:202–212. doi: 10.1038/nri2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo HJ, Kohler JR, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Fink GR. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997;90:939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Montes HM, Bates S, Netea MG, az-Jimenez DF, Lopez-Romero E, Zinker S, Ponce-Noyola P, Kullberg BJ, Brown AJ, Odds FC, Flores-Carreon A, Gow NA. Endoplasmic reticulum alpha-glycosidases of Candida albicans are required for N glycosylation, cell wall integrity, and normal host-fungus interaction. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:2184–2193. doi: 10.1128/EC.00350-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad AM, d'Enfert C, Gaillardin C, Tournu H, Tekaia F, Talibi D, Marechal D, Marchais V, Cottin J, Brown AJ. Transcript profiling in Candida albicans reveals new cellular functions for the transcriptional repressors CaTup1, CaMig1 and CaNrg1. Mol Microbiol. 2001a;42:981–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad AM, Leng P, Straffon M, Wishart J, Macaskill S, MacCallum D, Schnell N, Talibi D, Marechal D, Tekaia F, et al. NRG1 represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis and hypha-specific gene expression in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 2001b;20:4742–4752. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naglik JR, Fostira F, Ruprai J, Staab JF, Challacombe SJ, Sundstrom P. Candida albicans HWP1 gene expression and host antibody responses in colonization and disease. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:1323–1327. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46737-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naglik JR, Moyes D, Makwana J, Kanzaria P, Tsichlaki E, Weindl G, Tappuni AR, Rodgers CA, Woodman AJ, Challacombe SJ, et al. Quantitative expression of the Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase gene family in human oral and vaginal candidiasis. Microbiology. 2008;154:3266–3280. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naglik JR, Newport G, White TC, Fernandes-Naglik LL, Greenspan JS, Greenspan D, Sweet SP, Challacombe SJ, Agabian N. In vivo analysis of secreted aspartyl proteinase expression in human oral candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:2482–2490. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2482-2490.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naglik JR, Rodgers CA, Shirlaw PJ, Dobbie JL, Fernandes-Naglik LL, Greenspan D, Agabian N, Challacombe SJ. Differential expression of Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase and phospholipase B genes in humans correlates with active oral and vaginal infections. J Infect. Dis. 2003;188:469–479. doi: 10.1086/376536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Gow NA, Munro CA, Bates S, Collins C, Ferwerda G, Hobson RP, Bertram G, Hughes HB, Jansen T, et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1642–1650. doi: 10.1172/JCI27114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, Gow NAR. An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Micro. 2008;6:67–78. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobile CJ, Solis N, Myers CL, Fay AJ, Deneault JS, Nantel A, Mitchell AP, Filler SG. Candida albicans transcription factor Rim101 mediates pathogenic interactions through cell wall functions. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2180–2196. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odds FC. Candida and Candidosis. Bailliere Tindall; Philadelphia: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Opitz B, Puschel A, Beermann W, Hocke AC, Forster S, Schmeck B, van L, V, Chakraborty T, Suttorp N, Hippenstiel S. Listeria monocytogenes activated p38 MAPK and induced IL-8 secretion in a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1-dependent manner in endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:484–490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaine A, Walker L, Da Costa G, Mora-Montes HM, McKinnon A, Gow NAR, Gaillardin C, Munro CA, Richard ML. Functional analysis of Candida albicans GPI-anchored proteins: Roles in cell wall integrity and caspofungin sensitivity. Fung Genet Biol. 2008;45:1404–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman D, Mistry M, Thavaraj S, Challacombe SJ, Naglik JR. Murine model of concurrent oral and vaginal Candida albicans colonization to study epithelial host-pathogen interactions. Microbes. Infect. 2007;9:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder A, Kirschning CJ, Schaller M, Weindl G, Wagner H, Korting HC, Rupec RA. Induction of nuclear factor- kappa B and c-Jun/activator protein-1 via toll-like receptor 2 in macrophages by antimycotic-treated Candida albicans. J Infect. Dis. 2004;190:1318–1326. doi: 10.1086/423854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller M, Zakikhany K, Naglik JR, Weindl G, Hube B. Models of oral and vaginal candidiasis based on in vitro reconstituted human epithelia. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2767–2773. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. CREB: A Stimulus-Induced Transcription Factor Activated by A Diverse Array of Extracellular Signals. Ann Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Liu Y. Regulation of innate immune response by MAP kinase phosphatase-1. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1372–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Seed B. A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucl. Acids. Res. 2003;31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindl G, Naglik JR, Kaesler S, Biedermann T, Hube B, Korting HC, Schaller M. Human epithelial cells establish direct antifungal defense through TLR4-mediated signaling. J Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3664–3672. doi: 10.1172/JCI28115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom R. AP-1: One Switch for Many Signals. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:180–185. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakikhany K, Naglik JR, Schmidt-Westhausen A, Holland G, Schaller M, Hube B. In vivo transcript profiling of Candida albicans identifies a gene essential for interepithelial dissemination. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2938–2954. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Wang X, Nelin LD, Yao Y, Matta R, Manson ME, Baliga RS, Meng X, Smith CV, Bauer JA, et al. MAP kinase phosphatase 1 controls innate immune responses and suppresses endotoxic shock. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:131–140. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.