Abstract

The truncated C2- and C8-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a-d were synthesized from D-mannose, using palladium-catalyzed cross coupling reactions as key steps. In this study, an A3 adenosine receptor (AR) antagonist, truncated 4′-thioadenosine derivative 3 was successfully converted into a potent A2AAR agonist 4a (Ki = 7.19 ± 0.6 nM) by appending a 2-hexynyl group at the C2-position of a derivative of 3 that was N6-substituted. However, C8-substitution greatly reduced binding affinity at the human A2AAR. All synthesized compounds 4a-d maintained their affinity at the human A3AR, but 4a was found to be a competitive A3AR antagonist/A2AAR agonist in cyclic AMP assays. This study indicates that the truncated C2-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a and 4b can serve as a novel template for the development of new A2AAR ligands.

Keywords: A2A adenosine receptor agonists, truncated 2-hexynyl-4′-thioadenosine, palladium-catalyzed cross coupling reactions, binding mode

The endogenous cytoprotective modulator adenosine (1) exerts its pharmacological effects against hypoxia, ischemia, and inflammation through binding to four subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) of adenosine receptors (ARs), members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family.1 Among these, activation of A2AAR has been known to play a role in the suppression of immune and inflammatory responses and in vascular responses to adenosine.2 It is also highly localized within the central nervous system (CNS), and selective antagonists have become an attractive target for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.3 The A3AR is the most recently identified subtype and is found in the cardiovascular system, CNS, immune cells, lung, and liver.4,5 The activation of A3AR is beneficial in models of myocardiac and cerebral ischemia and cancer, while its antagonism is of interest for treating asthma, inflammation, and glaucoma.6

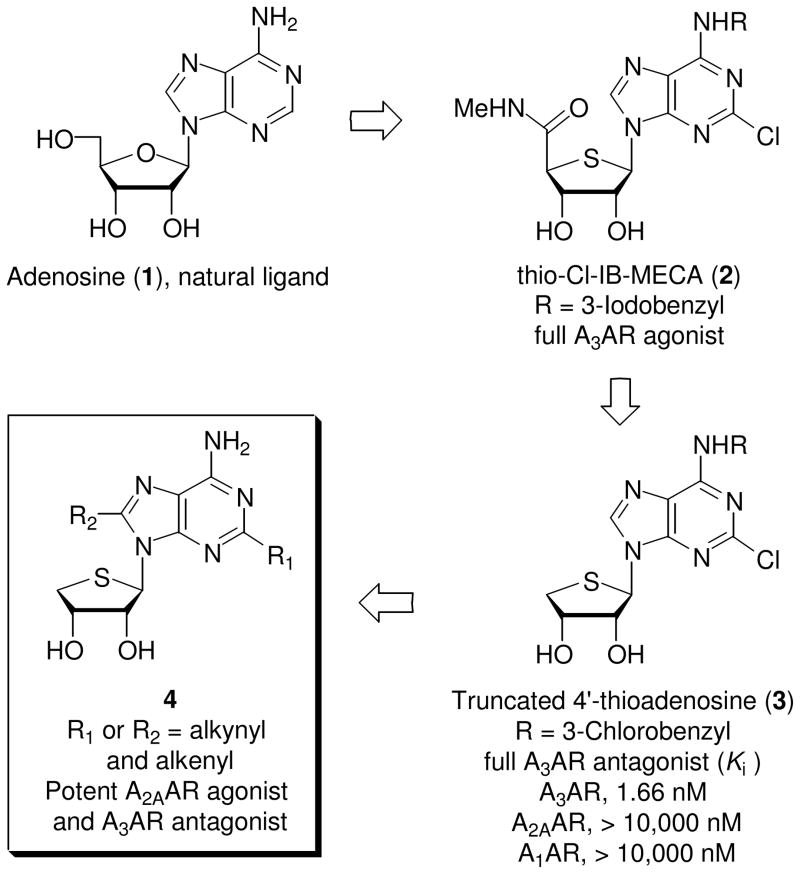

Thio-Cl-IB-MECA (2)7 which is bioisosteric with 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide (Cl-IB-MECA)8 was discovered as a potent and selective A3AR agonist (Ki = 0.38 nM). This compound showed a potent anticancer activity by inhibiting the Wnt signaling pathway.9 On the basis of rational design, truncated 4′-thioadenosine derivative 3 lacking the 5′-uronamide of 2 essential for the receptor activation was discovered as a potent, selective, and species-independent A3AR antagonist (Ki = 1.66 nM).10 This compound and other related A3AR antagonists with nucleoside skeletons are expected to be suitable for evaluation in small animal models and for further development as drugs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The rationale for the design of A2A adenosine receptor agonists

Based on the observation that truncation resulting in the 4′-thioadenosine antagonist derivative 3 preserved AR affininity and selectivity, we designed and synthesized the truncated C2- and C8-substituted 4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a-d as potential new ligands for the A2AAR. This expectation was supported by reports that C2- or C8-substitution sometimes leads to substantial enhancement in the binding affinity or selectivity at the A2AAR or other AR subtype.11 C2- or C8-substitution was readily achieved through Sonogashira12 and Suzuki13 cross coupling reactions. From this study, a C2-alkynyl derivative was found to be potent, mixed A2AAR agonist and A3AR antagonist, which is an excellent combination for the anti-asthmatic activity. Herein, we describe the synthesis and pharmacological activity of novel C2- and C8-substituted 4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a-d from D-mannose.

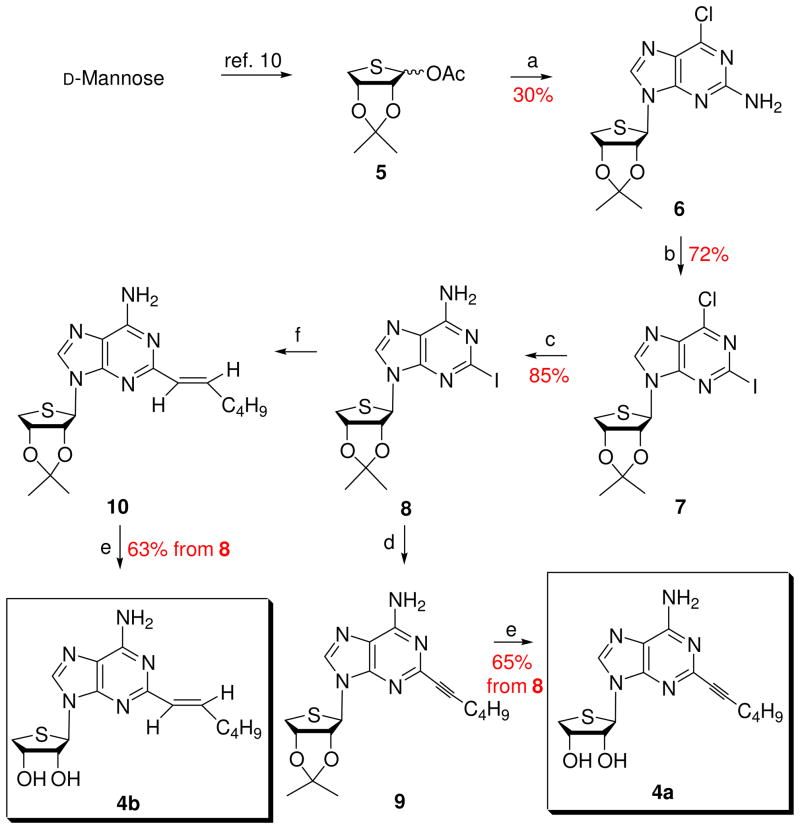

D-Mannose was converted to the glycosyl donor 5 according to our previously published procedure.10 The glycosyl donor 5 was condensed with 2-amino-6-chloropurine in the presence of TMSOTf as a Lewis acid to give the β-anomer 6 (30%) as a single stereoisomer (Scheme 1). The anomeric assignment was easily accomplished in a 1H NMR experiment that showed a NOE between H-8 and 3′-H. Treatment of 2-amino-6-chloro derivative 6 with isoamyl nitrite, iodine, and methylene iodide in the presence of CuI afforded the 2-iodo-6-chloro derivative 7, which was converted to the 2-iodo-6-amino derivative 8 upon treatment with methanolic ammonia. Sonogashira12 coupling reaction of 8 with 1-hexyne in the presence of bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium dichloride yielded the 2-hexynyl derivative 9. Finally, removal of the isopropylidene of 9 with 1 N HCl produced the final 2-hexynyl-4′-thioadenosine derivative 4a. Suzuki13 coupling reaction of the 2-iodo derivative 8 with (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene14, prepared by treating with 1-hexyne and catecholborane, in the presence of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0) afforded the 2-hexenyl derivative 10. Removal of the acetonide of 10 with 1 N HCl gave the 2-hexenyl-4′-thioadenosine derivative 4b.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the 2-substituted derivatives 4a and 4b.

Reagents and conditions: a) silylated 2-amino-6-chloropurine, TMSOTf, DCE, rt to 80 °C, 3 h; b) CuI, isoamyl nitrite, I2, CH2I2, THF, 110 °C, 45 min; c) NH3/MeOH, 80 °C, 2 h; d) 1-hexyne, CuI, TEA, DMF, bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium dichloride, rt, 3 h; e) 1 N HCl, THF, rt, 15 h; f) (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene, then tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0), Na2CO3, DMF, H2O, 90 °C, 15 h.

Using a strategy similar to Scheme 1, 8-substituted adenosine derivatives 4c and 4d were synthesized from the glycosyl donor 5 (Scheme 2). Condensation of 5 with 8-bromoadenine15 under Lewis acid conditions, afforded the 8-bromo derivative 11. Coupling of 11 with 1-hexyne under Sonogashira conditions gave 8-hexynyl derivative 12, which was treated with 1 N HCl to yield the final 8-hexynyl-4′-thioadenosine derivative 4c.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the 8-substituted derivatives 4c and 4d.

Reagents and conditions: a) silylated 8-bromoadenine, TMSOTf, DCE, rt to 90 °C, 2 h; b) 1-hexyne, CuI, TEA, DMF, bis(triphenylphosphine) palladium dichloride, rt, 3 h; c) 1 N HCl, THF, rt, 15 h; d) (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene, then tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) palladium(0), Na2CO3, DMF, H2O, 90 °C, 15 h.

The 8-bromo derivative 11 was condensed with (E)-1-catecholboranylhexene14 under Suzuki conditions13 to give the 2-hexenyl derivative 13. Removal of the isopropylidene group of 13 under acidic conditions afforded the final 8-hexenyl-4′-thio adenosine derivative 4d.

Binding assays were carried out using standard radioligands and membrane preparations from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing the human (h) A1 or A3AR or human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293) expressing the hA2AAR.16 Unlike the parent N6-substituted compound 3 that only weakly bound to the A2AAR, C2-substituted variations of compound 3 led to a dramatic increase in the binding affinity (Ki = 7.19 ± 0.6 nM for 4a and 72.0 ± 19.1 nM for 4b) at the hA2AAR, while maintaining high binding affinity (Ki = 11.8 ± 1.3 nM for 4a and 13.2 ± 0.8 nM for 4b) at the hA3AR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Binding affinities of known A3AR antagonist 3 and truncated 2- and 8-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a-d at three subtypes of hARs.

| Compounds | Affinitya | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| hA1 (% inhibition) | hA2A (% inhibition) | hA3 (Ki, nM) | |

| 3 | 37.9% | 17.7% | 1.66 ± 0.90 |

| 4a | 38.9 ± 9.9% | 97.2 ± 4.1% | 11.8 ± 1.3 |

| 4b | 16.2 ± 8.4% | 95.9 ± 8.7% | 13.2 ± 0.8 |

| 4c | 49.3 ± 4.9% | 46.5 ± 4.3% | 20.0 ± 4.0 |

| 4d | 3.7 ± 2.9% | 22.8 ± 6.4% | 259 ± 10 |

All binding experiments were performed using adherent mammalian cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding the appropriate hAR (A1AR and A3AR in CHO cells and A2AAR in HEK-293 cells). Binding was carried out using 1 nM [3H]CCPA, 10 nM [3H]CGS21680, or 0.5 nM [125I]I-AB-MECA as radioligands for A1, A2A, and A3ARs, respectively. Values are expressed as mean ± sem, n = 3–4 (outliers eliminated) and normalized against a non-specific binder, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA, 10 μM). Values expressed as a percentage refer to percent inhibition of specific radioligand binding at 10 μM, with nonspecific binding defined using 10 μM NECA.

These results indicate that bulky hydrophobic pockets exist in the binding sites of A2AAR and A3AR, allowing the C2-substituent to form favorable hydrophobic interactions. The 2-alkynyl derivative 4a showed a better binding affinity than the 2-alkenyl derivative 4b. Interestingly, C8-substitution on 3 abolished the binding affinity at the hA2AAR, but the binding affinity at the hA3AR was maintained although decreased. These findings suggest that a bulky hydrophobic group at position 8 could be tolerated at the binding site of the hA3, but not hA2AAR. The ability to enhance affinity at the A2AAR in the truncated series by extending an unsaturated carbon chain at the 2 position implies a mode of receptor binding in common with the riboside series.11 All compounds showed very weak binding affinity at the hA1AR.

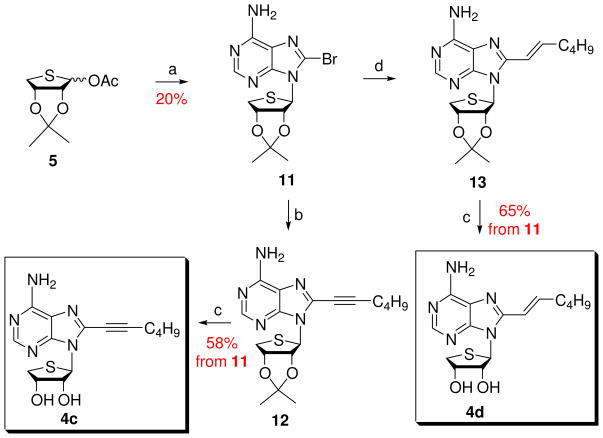

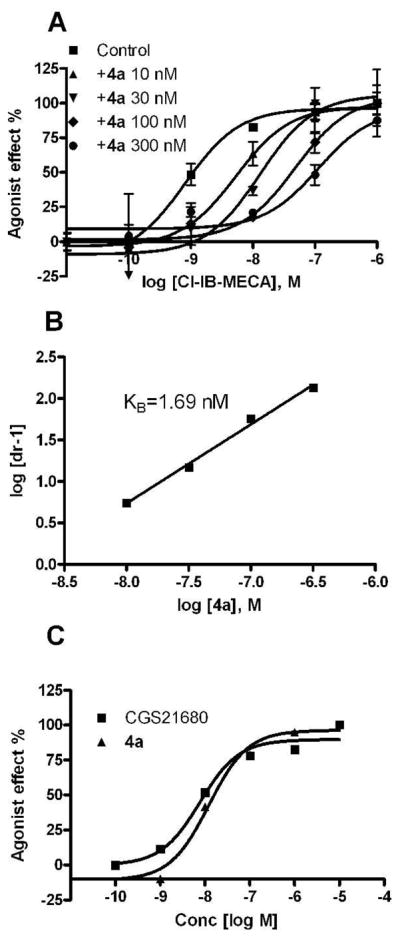

Compounds 4a and 4b were found to be potent and full antagonists in a cyclic AMP functional assay at the hA3AR. In this assay, 4a dose-dependently shifted the concentration-response curve for agonist Cl-IB-MECA to the right as an antagonist, corresponding to a KB value of 1.69 nM calculated by Schild analysis (Figure 2). This is consistent with previous studies in which truncated N6-substituted 4′-thioadenosine derivatives have generally displayed A3 AR antagonist activity.10 However, in a cyclic AMP functional assay at the hA2AAR expressed in CHO cells, compound 4a behaved as a full agonist compared to the standard 2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl-ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS21680) and displayed an EC50 of 12 nM. At the hA2BAR expressed in CHO cells, 4a was a weak partial agonist in cyclic AMP accumulation (EC50 ~10 μM). The finding that compound 4a is both a potent and selective agonist at the hA2AAR and a competitive antagonist at the hA3AR is similar to the pharmacological profile of a more heavily 2,5′-substituted adenosine derivative17 which inhibited both formation of ROS and eosinophils degranulation for the anti-asthmatic activity.

Figure 2.

Parallel right shifts induced by compound 4a on the concentration-response curve of a full agonist in the inhibition of cyclic AMP production at the hA3AR expressed in CHO cells (A), the corresponding Schild plot (B) and the activity of 4a as a full agonist at the h A2AAR expressed in CHO cells, compared to CGS21680 (C).

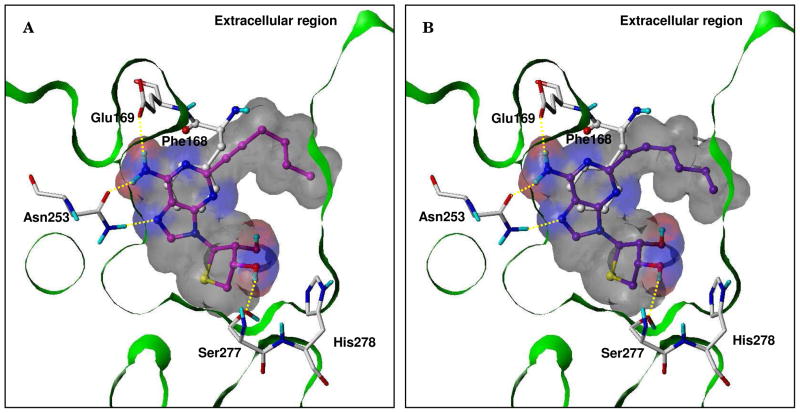

To investigate the binding mode, we performed a study of docking the C2- and C8-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a-d in the hA2AAR X-ray crystallographic structure (PDB code: 3EML)18 using the GOLD software19, considering the flexibility of the binding site residues. As shown in Figure 3, the C2-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a and 4b, whose binding affinities are in the nM range, occupied the binding site very well. Their bulky and rigid C2-substituents oriented toward the extracellular region, forming hydrophobic interactions. The adenine moieties appeared to form three H-bonds with Glu169 and Asn253, and the ring systems were in π-π stacking with Phe168. Also, the thio-sugar rings were located deep inside the binding pocket, and the 3′-OH groups were able to donate a H-bond to Ser277. Based on this result, the C8-substituents were expected to be oriented in a hydrophobic pocket deep inside the binding site, which was not occupied by 4a and 4b in Figure 3. However, the C8-substitued derivatives 4c and 4d showed various binding modes (data not shown). In addition to the expected binding mode, the C8-substituents alternately pointed toward the extracellular region through a rotation of the bond between the adenine and thio-sugar rings. It might be due to spatial restriction of the long and rigid C8-substituents in the hydrophobic pocket inside the binding site, which would cause the nucleosides to lose some H-bonding and/or π-π stacking interactions that were shown for the C2-substituted derivatives. These results might explain why the A2AAR affinities of 4c and 4d were reduced.

Figure 3.

Predicted binding modes of (A) 4a and (B) 4b docked in the hA2AAR crystal structure. The key interacting residues are marked and displayed in capped-stick, except Phe168 in ball-and-stick, with carbon atoms in white. The ligands are depicted as ball-and-stick with carbon atoms in magenta (4a) and purple (4b). Hydrogen bonds are shown in yellow dashed lines. The Van der Waals surfaces of the ligands were generated by MOLCAD and colored by hydrogen bonding property (red: H-bond donating regions; blue: H-bond accepting regions). The Fast Connolly surface of the protein is Z-clipped and non-polar hydrogens are undisplayed for clarity.

In conclusion, we synthesized the truncated C2-and C8-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a-d, starting from D-mannose, using palladium-catalyzed cross coupling reactions as key steps. Although the antagonist activity of various truncated 4′-thionucleosides at the A3AR was well explored previously, this is the first characterization of the functional activity of such derivatives at the A2AAR. From this study, we successfully identified potent and sterically compact A2AAR agonists, 4a and 4b by placing extended hydrophobic 2-hexynyl or 2-hexenyl groups on truncated and N6-unsubstituted 4′-thioadenosine derivatives. This observation was supported by molecular modeling that placed the chain at the 2 position in a hydrophobic region of the A2AAR. However, C8-substitution greatly reduced binding affinity at the hA2AAR. Thus, the absence of a 5′-uronamide of typical A2AAR agonists2 or the native -CH2OH of adenosine did not preclude potent binding and full activation of the hA2AAR. This suggested a major difference between A2AAR and the A3AR in the pathway of receptor activation. All synthesized compounds 4a-d maintained their binding affinity at the human A3AR, and as for the 2-H or 2-Cl analogues that were N6-substituted, competitive A3AR antagonism was demonstrated. This study establishes that the truncated C2-substituted-4′-thioadenosine derivatives 4a and 4b can serve as a novel template for the development of new A2AAR ligands, although they still may interact at the A3AR. This mixed activity as A2AAR agonist/A3AR antagonist might also be advantageous in disease models such as asthma.17 Thorough elucidation of the structure-activity relationship of this series is in progress in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research grant (NRF-2008-314-E00304), the National Core Research Center grant (R15-2006-020), the World Class University grant (R31-2008-000-10010-0) from National Research Foundation (NRF), Korea, and the Intramural Research Program of NIDDK, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE: Complete experimental procedures and characterization data and 1H and 13C NMR copies of 4a-d. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Olah ME, Stiles GL. The role of receptor structure in determining adenosine receptor activity. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85:55–75. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Fredholm BB, Cunha RA, Svenningsson P. Pharmacology of adenosine receptors and therapeutic applications. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;3:413–426. doi: 10.2174/1568026033392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sitkovsky MV, Lukashev D, Apasov S, Kojima H, Koshiba M, Cladwell C, Ohta A, Thiel M. Physiological control of immune response and inflammatory tissue damage by hypoxia-inducible factors and adenosine A2A receptors. Ann Rev Immunol. 2004;22:657–682. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lappas CM, Sullivan GW, Linden J. Adenosine A2A agonists in development for the treatment of inflammation. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2005;14:797–806. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.7.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svenningsson P, Hall H, Sedvall G, Fredholm BB. Distribution of adenosine receptors in the postmortem human brain: an extended autoradiographic study. Synapse. 1997;27:322–335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199712)27:4<322::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linden J. Cloned adenosine A3 receptors: pharmacological properties, species differences and receptor functions. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:298–306. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baraldi PG, Cacciari B, Romagnoli R, Merighi S, Varani K, Borea PA, Spalluto G. A3 adenosine receptor ligands: history and perspectives. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:103–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(200003)20:2<103::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Jeong LS, Jin DZ, Kim HO, Shin DH, Moon HR, Gunaga P, Chun MW, Kim Y-C, Melman N, Gao Z-G, Jacobson KA. N6-Substituted D-4′-thioadenosine-5′-methyluronamides: Potent and selective agonists at the human A3 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3775–3777. doi: 10.1021/jm034098e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeong LS, Lee HW, Jacobson KA, Kim HO, Shin DH, Lee JA, Gao ZG, Lu C, Duong HT, Gunaga P, Lee SK, Jin DZ, Chun MW, Moon HR. Structure-activity relationships of 2-chloro-N6-substituted-4′-thioadenosine-5′-uronamides as highly potent and selective agonists at the human A3 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2006;49:273–281. doi: 10.1021/jm050595e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HO, Ji X-d, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5′-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EJ, Min HY, Chung HJ, Park EJ, Shin DH, Jeong LS, Lee SK. A novel adenosine analog, thio-Cl-IB-MECA, induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Jeong LS, Choe SA, Gunaga P, Kim HO, Lee HW, Lee SK, Tosh DK, Patel A, Palaniappan KK, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Moon HR. Discovery of a new nucleoside template for human A3 adenosine receptor ligands: D-4′-thioadenosine derivatives without 4′-hydroxymethyl group as highly potent and selective antagonists. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3159–3162. doi: 10.1021/jm070259t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeong LS, Pal S, Choe SA, Choi WJ, Jacobson KA, Gao Z-G, Klutz AM, Hou X, Kim HO, Lee HW, Tosh DK, Moon HR. Structure-activity relationships of truncated D- and L-4′-thioadenosine derivatives as species-independent A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2008;51:6609–6613. doi: 10.1021/jm8008647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Matsuda A, Shinozaki M, Yamaguchi T, Homma H, Nomoto R, Miyasaka T, Watanabe Y, Abiru T. Nucleosides and Nucleotides. 103. 2-Alkynyladenosines: a novel class of selective adenosine A2 receptor agonists with potent antihypertensive effects. J Med Chem. 1992;35:241–252. doi: 10.1021/jm00080a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cristalli G, Volpini R, Vittori S, Camaioni E, Monopoli A, Conti A, Dionisotti S, Zocchi C, Ongini E. 2-Alkynyl derivatives of adenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide (NECA): selective A2 adenosine receptor agonists with potent inhibitory activity on platelet aggregation. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1720–1726. doi: 10.1021/jm00037a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lambertucci C, Costanzi S, Vittori S, Volpini R, Cristalli G. Synthesis and adenosine receptor affinity and potency of 8-alkynyl derivatives of adenosine. Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2001;20:1153–1157. doi: 10.1081/NCN-100002509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinchilla R, Nájera C. The Sonogashira reaction: A booming methodology in synthetic organic chemistry. Chem Rev. 2007;107:874–922. doi: 10.1021/cr050992x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki A. Carbon-carbon bonding made easy. Chem Commun. 2005;38:4759–4763. doi: 10.1039/b507375h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed Reaction of 1-alkenylboronates with vinylic halides: (1 Z,3E)-1-phenyl-1,3-octadiene. Org Syn Coll Vol. 1993;8:532–534. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laxer A, Major DT, Gottlieb HE, Fischer B. (15N5)-Labeled Adenine Derivatives: Synthesis and Studies of Tautomerism by 15N NMR Spectroscopy and Theoretical Calculations. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5463–5481. doi: 10.1021/jo010344n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Perreira M, Jiang JK, Klutz AM, Gao ZG, Shainberg A, Lu C, Thomas CJ, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 2005;48:4910–4918. doi: 10.1021/jm050221l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jarvis MF, Schutz R, Hutchison AJ, Do E, Sills MA, Williams M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:978–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nordstedt C, Fredholm BB. Anal Biochem. 1990;189:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90113-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bevan N, Butchers PR, Cousins R, Coates J, Edgar EV, Morrison V, Sheehan MJ, Reeves J, Wilson DJ. Pharmacological characterisation and inhibitory effects of (2R,3R,4S,5R)-2-(6-amino-2-{[(1S)-2-hydroxy-1-(phenylmethyl)ethyl]amino}-9H-purin-9-yl)-5-(2-ethyl-2H-tetrazol-5-yl)tetra hydro-3,4-furandiol, a novel ligand that demonstrates both adenosine A2A receptor agonist and adenosine A3 receptor antagonist activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;564:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EYT, Lane JR, Ijzerman AP, Stevens RC. The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.GOLD, version 4.1.2. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre; Cambridge, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.