Abstract

The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) is a critical integrative site for coordination of autonomic and endocrine stress responses. Stress-excitatory signals from the NTS are communicated by both cathecholaminergic (norepinephrine (NE), epinephrine(E)) and non-catecholaminergic (e.g., glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) neurons). Recent studies suggest that outputs of the NE/E and GLP-1 neurons of the NTS are selectively engaged during acute stress. This study was designed to test mechanisms of chronic stress integration in the PVN, focusing on the role of glucocorticoids. Our data indicate that chronic variable stress (CVS) causes down-regulation of preproglucagon (GLP-1 precursor) mRNA in the NTS and reduction of GLP-1 innervation to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Glucocorticoids were necessary for PPG reduction in CVS animals, and were sufficient to lower PPG mRNA in otherwise unstressed animals. The data are consistent with a glucocorticoid-mediated withdrawal of GLP-1 in key stress circuits. In contrast, expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) mRNA, the rate limiting enzyme in catecholamine synthesis, was increased by stress in a glucocorticoid-independent manner. These suggest differential roles of ascending catecholamine and GLP-1 systems in chronic stress, with withdrawal of GLP-1 involved in stress adaptation, and enhanced NE/E capacity responsible for facilitation of responses to novel stress experiences.

Keywords: glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), glucocorticoid, hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, habituation, facilitation

Introduction

Hindbrain neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) represent an important way-station in processing of stressful stimuli. These neurons initiate physiological responses through projections to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and preautonomic effector systems (such as the rostral ventrolateral medulla), resulting in secretion of glucocorticoids and activation of the autonomic nervous system (c.f., (Plotsky et al., 1989a; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). The critical role of NTS relays in stress responding is underscored by a strong linkage between ascending noradrenergic neurons and generation of glucocorticoid release following acute challenge (Plotsky, 1987; Szafarczyk et al., 1987). Emerging evidence also supports a role for non-catecholaminergic, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) NTS neurons in stress stimulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and autonomic regulation, suggesting the existence of multiple stress-integrative pathways from this important hindbrain locus (Kinzig et al., 2002; Kinzig et al., 2003).

Catecholamines and GLP-1 are produced in different cells that comprise the two major populations of stress responsive neurons in the NTS (Larsen et al., 1997). Moreover, NE/E neurons appear to be preferentially involved in generating responses to homeostatic challenge (Gaillet et al., 1991; Ritter et al., 2003), whereas GLP-1 neurons mediate HPA axis responses to both psychogenic and homeostatic stressors (Kinzig et al., 2003). Together, the data suggest that NE/E and GLP-1 neurons have distinct roles in CNS regulation of stress responses.

Appropriate regulation of stress responding requires the capacity for integration over time. Acute, ‘one-time’ stress responses are critical for short term survival, and are efficiently initiated and terminated by neuronal drive and glucocorticoid negative feedback (Herman and Cullinan, 1997; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). Prolonged or intermittent stress represents a significant temporal challenge that engages mnemonic systems to fuel long term changes that can be adaptive or in many cases, maladaptive. Previous studies indicate that neural governance of stress responses shifts significantly during exposure to chronic drive, resulting in recruitment and de-recruitment of neural pathways (Marti et al., 1994; Schulkin et al., 1994; Dallman et al., 2003). Re-organization of stress signaling circuitry appears to underlie habituation and sensitization of effector pathways, including the HPA axis.

Noradrenergic and GLP-1 containing terminals heavily innervate the hypophysiotrophic as well as autonomic zones of the PVN, underscoring the importance of these two neurotransmitters in stress processing (Sawchenko and Swanson, 1981; Liposits et al., 1986; Sarkar et al., 2003; Tauchi et al., 2008a). These neurons are subject to descending inputs from structures such as the infralimbic cortex and central amygdaloid nucleus (Schwaber et al., 1982; Vertes, 2004), regions thought to be recruited during chronic stress drive (Dallman et al., 2003; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). Moreover, neurons in the NTS contain both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors (Ahima and Harlan, 1990; Geerling et al., 2006), with evidence for co-localization of glucocorticoid receptors with catecholaminergic markers (Uht et al., 1988). The latter suggests that stress-induced glucocorticoid secretion may modulate NTS function.

The centrality of the NTS in stress initiation makes it a potentially important node in processes regulating stress adaptation and/or maladaptation. In the current report, we document different patterns of stress plasticity in catecholaminergic and GLP-1 containing NTS cell populations following chronic stress or glucocorticoid exposure, providing evidence for differential involvement of these two important hindbrain pathways in control of chronic stress responses.

Material and methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 250–300g were housed 2 rats per cage with free access to rat chow and water. All animals were maintained on a 12:12h light/dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium, with lights on from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Animals were maintained in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Cincinnati.

Chronic variable stress (CVS) procedure

Animals were stressed with our standard CVS procedure for 2 weeks (see Supplementary Data (SI Table1). After completion of the CVS paradigm (day 15), rats were killed by decapitation on the following morning. Trunk blood, adrenal and thymus glands were collected for further analysis or measurement. For in situ hybridization and Q RT-PCR, removed brains were immersed into isopentane cooled on dry ice (−45C), and stored at −80C till further procedure. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), animals were treated with the same CVS schedule noted above. After completion of the CVS paradigm (day 15), animals were anesthetized and perfused with 100 ml 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde as previously described (Zhang et al., 2009).

CVS in adrenalectomized-corticosterone replaced (ADX-Cort) rats

Bilateral adrenalectomies (ADX) were performed under anesthesia (Ketamine, 87mg/kg; Xylazine, 13mg/kg) and the surgical specimens examined immediately to ensure complete excision of the adrenal glands. Sham ADX animals had identical surgical procedures with the exception of adrenal removal. ADX animals were provided with 0.9% saline to replace depleted sodium secondary to the loss of aldosterone, with corticosterone (30ug/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Mo., USA) provided in the 0.9% drinking saline. Corticosterone was initially dissolved in ethyl alcohol (EtOH) and diluted to a final concentration of 30ug/ml in saline with 0.2% EtOH. Sham rats were provided with 0.2% EtOH in their drinking water. Three days after surgery, blood samples were collected by tail nick from freely moving rats within 2 hours of lights-on (basal nadir corticosterone level) and 2 hours of lights-off (basal peak corticosterone level) to determine unstressed corticosterone levels. After 1 week recovery from surgery, animals were assigned to four groups including Sham Control, Sham CVS, ADX Control and ADX. Rats were exposed to our standard CVS paradigm (See SI Table 1) for 2 weeks and killed by decapitation the morning after the last afternoon stress exposure (approx. 16 h). Trunk blood, brains, thymi and adrenals (sham rats) were collected and treated as described above for further analysis.

Regulation of PPG and TH gene expression by exogenous corticosterone

The regulation of TH and PPG gene expression by glucocorticoids was tested using twice-daily injection of corticosterone (AM, 9:00–10:00; PM, 3:00–4:00, which mirrored our standard CVS schedule). Rats were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with corticosterone (3.5mg/kg/ml in propylene glycol vehicle, Sigma-aldich company) twice/day for 2 weeks. Vehicle groups were injected with propylene glycol. Rats were killed by decapitation in the following morning after last pm injection. Trunk blood, thymi, adrenal and brains were collected and stored as described above for further analysis. To confirm the plasma corticosterone levels induced by a single injection, blood samples were collected in freely-moving rats at 10 min, 30 min, 60 min and 120 min after the initial s.c. administration and plasma corticosterone determined by RIA. The timepoints of blood collection were determined to match the time-course of stress-induced plasma corticosterone determinations typically used in our acute stress designs (Zhang et al., 2009).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2009). Briefly, antisense cRNA probes complementary to rat PPG (399 bp) and TH (366bp) were used for in situ hybridization. The TH DNA construct was cloned into pCR 4-TOPO vector, linearized with SpeI and transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase. The final concentration of the in vitro transcription reactions were: 1× transcription buffer, 1.5~2.5ug of linearized DNA fragment, 330µm ATP, 330µm GTP, 330µm CTP, 10µm UTP, 62.5uCi of [35S] UTP, 66.6 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 40U of RNase inhibitor and 20U of the T7 or T3 RNA polymerase. The transcription reactions were incubated at 37C for 1 hour and the labeled probes were separated from free nucleotides by ammonium acetate precipitation and reconstituted in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated nanopure water. The probes were labeled by in vitro transcription using [35S] UTP, with pre-hybridization and post-hybridization protocols conducted as described previously (Zhang et al., 2009).

Hybridized slides were exposed on Kodak Biomax MR-2 film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY) for 3 weeks for PPG and 10 days for TH. Hybridizations with sense probe were used as specificity controls. ARC 146-14C standard slides (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St. Louis, MO) were used to construct standard curves, so as to verify that all signal intensities were in the linear range of detection.

Assessment of NTS mRNA expression was performed using the guidance of the Paxinos and Watson rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). Images were captured from in situ hybridization autoradiographs using a Cohu High Performance CCD Camera (Cohu, San Diego, CA) and Scion image 1.62 software (Scion, Frederick, MD). Semiquantitative analysis was conducted on every fifth brain section containing the anatomical region of interest. Mean gray level (signal) was quantified bilaterally in the NTS by subtracting the gray level signal over a nonhybridized area of tissue (white matter) and expressed as corrected gray level (CGL). The mean corrected gray level values were calculated for each animal and used in the statistical analysis in a blinded manner.

Quantitative Real Time polymerase chain reaction (Q RT-PCR)

The NTS was isolated according to the previously published methods (Zhang et al., 2009). Briefly, using the obex (bregma −14.40mm) and the 4th ventricle as landmarks, the NTS was isolated from anterior (rostral) margin (bregma ~11.04mm, 3.36mm from obex to rostral margin) to posterior (caudal) margin (bregma ~15.72mm,1.32 mm from obex to caudal margin). Both sides were trimmed ~1mm along the brain edges, and an additional cut was made ~ 2mm ventral to the dorsal surface of caudal brainstem. The NTS dissections were stored in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) at 4C until RNA extraction.

NTS dissections were homogenized in Tri-reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and total RNA was isolated following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were treated by Turbo DNA-free™ (Ambion, Austin, TX) to remove genomic DNA. cDNAs were synthesized (SuperScriptTM III First-Strand Synthesis System, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Primer sequences for PPG heteronuclear RNA (hnRNA), PPG mRNA and house-keeping gene, L32 were used as previously described (Zhang et al., 2009). TH primer sequences were designed using Primer3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000) and synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) (See SI Table 2). Q RT-PCR analysis was carried out in iCycler iQ™ Multi-Color Real Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA). cDNA amounts present in each sample were determined using iQ™ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA). Threshold cycle readings for each of the unknown samples were used, and the results were transferred and calculated in Excel using the ΔΔ Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Minus RT samples were included to rule out genomic DNA contamination, and amplicons of different primers were verified by electrophoresis. (SI Fig. 1)

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

For GLP-1 staining in the NTS, sections were pretreated for antigen retrieval (0.01M citrate buffer for 30min at 80C, PH 6.0) and IHC was performed as described previously (Huo et al., 2006). Free-floating sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-GLP-1 antibody (diluted 1:1000; Peninsula Laboratories Inc, San Carlos, CA) overnight. In our hands, this antibody provides optimal visualization of GLP-1 cell bodies in the hindbrain. Sections were rinsed 5×5 min in 50 mM potassium phosphate-buffered saline (KPBS) and transferred into Cy3-labeled Donkey-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab, West Grove, PA) for 1 hour. Sections were then rinsed with 5×5 min in KPBS, mounted onto slides and coverslipped with Gelvitol.

Hypothalamic sections were incubated in a mouse monoclonal anti-GLP-1 antibody which is specific for intact GLP-1 [7–36], overnight at 4C (diluted 1:10,000). In our hands, this antibody provides optimal visualization of GLP-1 axons and terminals (Tauchi et al., 2008a). Sections were rinsed 5×5 min in KPBS and subsequently incubated in biotinylated goat-anti-mouse secondary antibody (diluted 1:500; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour. Following 5×5 min rinses in KPBS, sections were incubated in avidin-biotin complex (diluted 1:1000; Vector Laboratories) for an additional hour. Sections were rinsed 5×5 min in KPBS, incubated in biotin-labeled tyramide (diluted 1:250, PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc., Boston, MA), rinsed 5×5 min and incubated in Cy3-conjugated streptavidin (diluted 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA) for 30 minutes. To verify hypothalamic depletion of GLP-1, immunohistochemistry was performed on an additional series of hypothalamic sections from the same animals, using a different primary antibody, enteroglucagon C-terminal octapeptide (EGCO, diluted 1:5000) (Collie et al., 1994). The EGCO antibody recognizes a different cleavage product of proglucagon (oxyntomodulin) (Collie et al., 1994). Biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) was used a secondary antibody, and tissue further processed for immunofluorescence using procedures outlined above.

For NTS TH immunohistochemistry, NTS sections were rinsed in 50mM KPBS and were incubated overnight with rabbit anti-TH (diluted 1:1500; Millipore) primary antibody. The next day, sections were incubated with Cy3-labeled Donkey-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (diluted 1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab, West Grove, PA) for 1 hour and visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Image collection and processing

All sections in the series were then examined by fluorescent microscopy to identify positive labeled cells and fibers. Images of the NTS were captured from low magnification to high magnification with a digital camera (AxioCam; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with Zeiss microscope (Axio-observer; Carl Zeiss). In 20X images, TH- and GLP-1-IR positive cells were individually selected and fluorescence intensity measured using AxioVision Rel. 4.6 software (Zeiss). Background was determined from equivalent unstained areas in each tissue section. The corrected densitometric signal was calculated by subtracting the background fluorescence from each cellular determination. All analyses were conducted by observers blind to the treatment conditions. The anatomical position of sections was determined from 5X images, based on Paxinos and Watson coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 2005).

Imaging of PVN GLP-1 and EGCO fiber density was performed using Axiovision Rel. 4.6 software. Images were captured using a Zeiss 510 Meta laser confocal microscope system in single-channel mode (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), as previously described (Zhang et al., 2009). All confocal images processed for analysis were collected using a 40× oil immersion lens with a numerical aperture of 1.5 at high capture resolution (image size 1024 × 1024 pixels). The images of the medial parvocellular division of the PVN were collected and Z-stack images were converted to 3D projections using Zeiss LSM 510 Image Browser software. The field area-percent occupied by proglucagon-derived peptide immunoreactivity were determined using the measurement function of Axiovision 4.6 software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), using methods previously established in our laboratory (Flak et al., 2009). Field areas were averaged across animals.

Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

Plasma corticosterone levels were determined by RIA using 125I RIA kits from MP Biomedicals (Orangeburg, NY). All plasma samples were analyzed in duplicate and plasma corticosterone measures from single experiment were undertaken in the same RIA analysis to avoid inter-assay variability. For the corticosterone RIA, the intraassay coefficient of variation was 8%.

Statistical analysis

All results are given as the mean ± SEM. In situ hybridization, immunohistochemcial and RIA data obtained from standard CVS experiment were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with StatView (SAS institute, Cary, NC), and significant main effects were further analyzed by PLSD post hoc test. GLP-1 and EGCO staining data were expressed as percentage of area occupied by immunoreactivity fiber in total measured areas. For Q RT-PCR analysis, L-32, a house-keeping gene was applied as reference gene to normalize the data. Values were calculated using L-32 as an internal standard. PPG and TH hnRNA and mRNA data were expressed as a percentage of control and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed with Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc test to distinguish among groups. For ADX CVS experiments, data were calculated as described above and statistical analyses were undertaken by two-way ANOVA (ADX-Cort, stress) with GB Stat Version 9.0 (Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Spring, MD), with significant main effects or interactions followed up with Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Effectiveness of the CVS paradigm

The CVS protocol uses random, unpredictable exposure to multiple stressors to produce a reliable constellation of physiological endpoints. CVS reduced the bodyweight gain (g) in day 7 (Control: 29.889 ± 2.248; CVS: 12.882 ± 1.755) and day 14 (Control: 52.278 ± 3.974; CVS: 25.824 ± 2.982) (P < 0.001). CVS exposure elevated the basal nadir plasma corticosterone (ng/ml) (Control: 27.59 ± 1.24; CVS: 85.77 ± 8.71; P < 0.01), which is consistent with previous reports (Herman et al., 1995). Both actual thymi weight (mg) (Control: 523.305 ± 26.304; CVS: 424.650 ± 14.486; P < 0.001) and adjusted thymi weight (actual thymi weight (mg)/bodyweight (g) × 100) (Control: 163.872 ± 8.554; CVS: 141.327 ± 4.664; P < 0.03) were decreased by CVS. CVS increased both actual adrenal weights (mg) (Control: 49.485 ± 0.939; CVS: 53.090 ± 1.260; P < 0.05) and adjusted adrenal weights (Control: 15.469 ± 0.288; CVS: 17.691 ± 0.446; P < 0.01). The observed thymic atrophy and adrenal hypertrophy are consistent with increased cumulative ACTH and glucocorticoid exposure, which are hallmarks of the CVS model (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2006).

CVS differentially regulates NTS peptidergic and catecholaminergic neurons

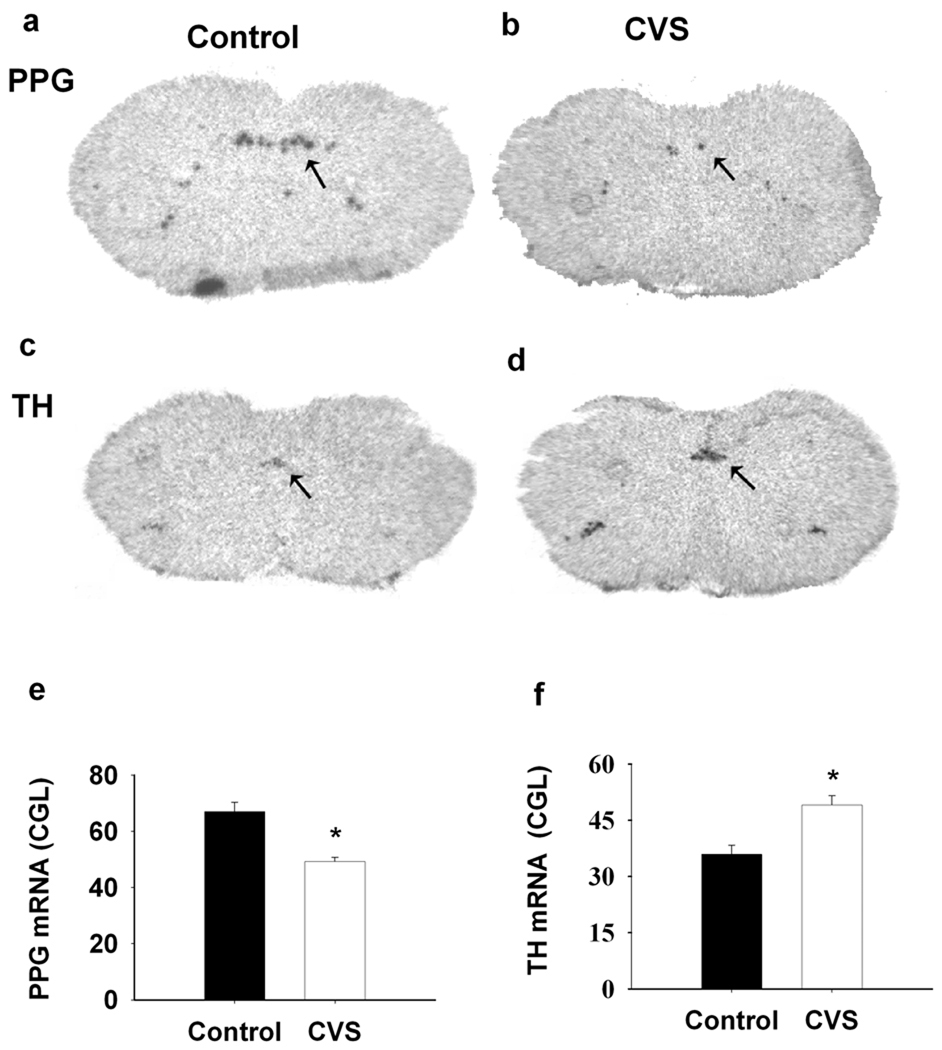

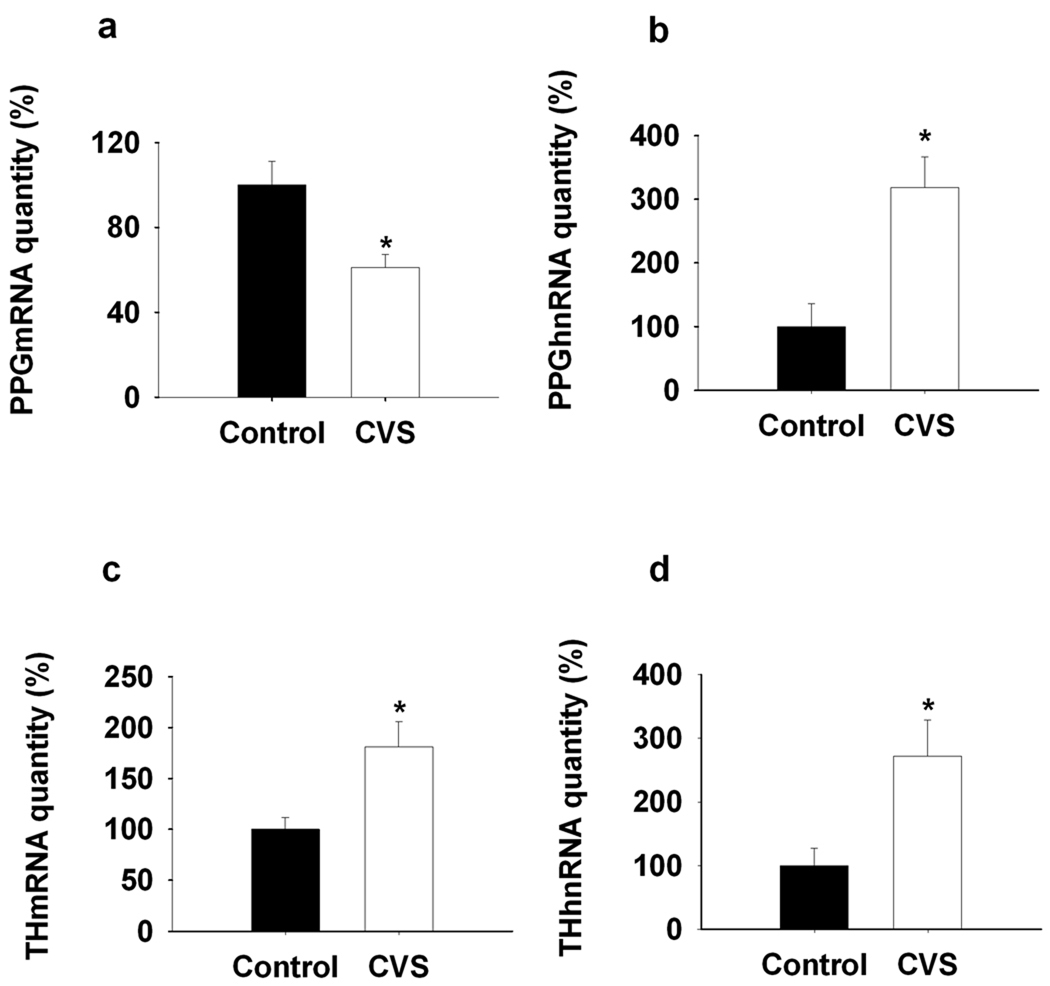

In the brainstem, PPG mRNA expression is confined to non-catecholaminergic neurons in the NTS and mediolateral medulla (Larsen et al., 1997). When analyzed by in situ hybridization, expression of PPG mRNA decreased following CVS exposure in NTS (F(1,8)=38.506, P<0.01) (Fig1. a, b, e). In contrast, NTS expression of TH mRNA was significantly augmented following CVS (F(1, 9)=13.945, P<0.01) (Fig1. c, d, f). The in situ hybridization results were confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis (PPGmRNA (F(1,13)=9.877, P<0.01); THmRNA (F(1,10)=9.05, P<0.01) (Fig2. a, c).

Figure 1.

CVS exposure affected the both PPG and TH mRNA expression in the NTS. a, b, c, d, Representative images for PPG mRNA and TH mRNA expression in the NTS. left side, Control; right side, CVS. e, f, Semi-quantitative results showed that CVS exposure declined PPG mRNA expression whereas enhanced TH mRNA expression in NTS. *, P<0.01 vs. Control.

Figure 2.

Q RT-PCR analysis of the regulation of NTS PPG and TH transcription by CVS exposure. a, b, NTS PPG mRNA expression decreased while PPG hnRNA expression increased by 2-week CVS exposure compared to the control. c, d, Prolonged stress exposure elevated TH mRNA and hnRNA expression in NTS compared to the naïve control. *, P < 0.01 vs. Control.

Transcription of PPG and TH genes was estimated by assessment of post-stress heteronuclear (hn) RNA expression, using quantitative PCR amplification of intronic sequences (intron D of the PPG primary transcript, intron 3 of the TH primary transcript). In contrast to expression of mature message, PPG hnRNA expression was elevated following CVS (F(1,8)=13.57, P<0.01) (Fig2. b). Expression of TH hnRNA was also elevated by CVS (F(1,11)=7.72, P<0.01) (Fig2. d), consistent with chronic stress-induced drive of TH production at the level of gene transcription.

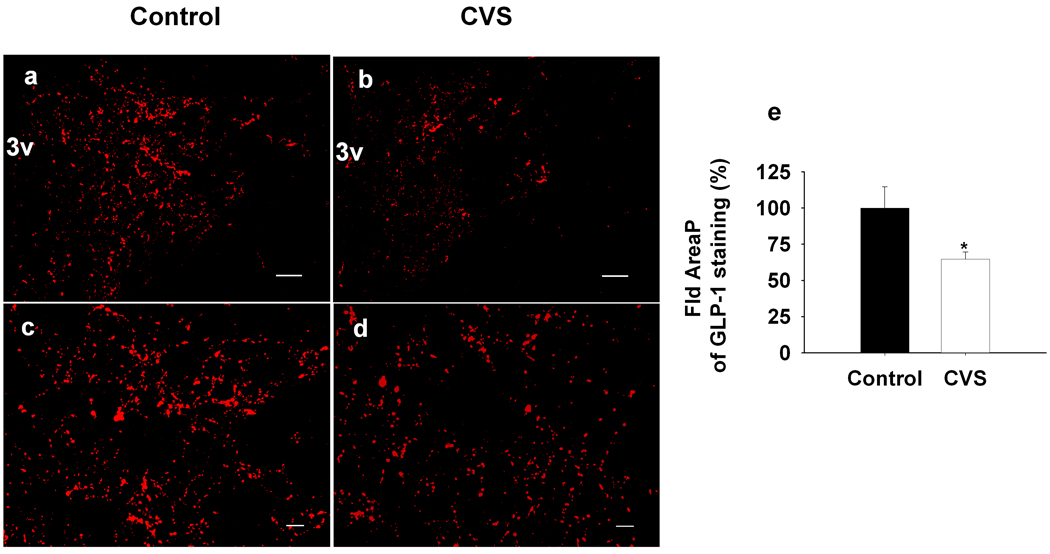

Changes in PPG and TH mRNA expression suggest altered availability of neuropeptide/neurotransmitters in circuitry responsible for long-term stress reactivity. To assess this possibility, we evaluated GLP-1 innervation of the medial parvocellular zone of the PVN following CVS. Our analysis revealed significant decreases in the density of GLP-1 immunoreactive fibers and terminals in the PVN following CVS (F(1,12)=5.38, P<0.05) (Fig3. a, b, c, d, e). To provide additional verification of PPG-derived peptide depletion in the PVN, we also assessed fiber density using a second antibody, which identified a co-cleaved PPG product, oxyntomodulin. Depletion of staining was identical to that seen using the anti-GLP-1 antibody (SI.Fig 2).

Figure 3.

Quantification of the expression of GLP-1 fiber in the mpPVN after 2-weeks CVS exposure. The field area occupied by GLP-1-IR positive fibers were determined and expressed as percentage of total measured area. Data are shown as percentage of Control. a, b, Representative images for low magnification GLP-1 fiber staining in the PVN. c, d, Representative images for high magnification of projection images. left side, Control; right side, CVS. e, Quantification of the expression of GLP-1 fiber in the mpPVN after CVS exposure. The percentage of area occupied by GLP-1-positive fibers was declined after 2-weeks CVS exposure compared to the control. Scale bars, 100um for low magnification images (a, b); 20 um for high magnification projection images (c, d). *, P<0.05 vs. Control.

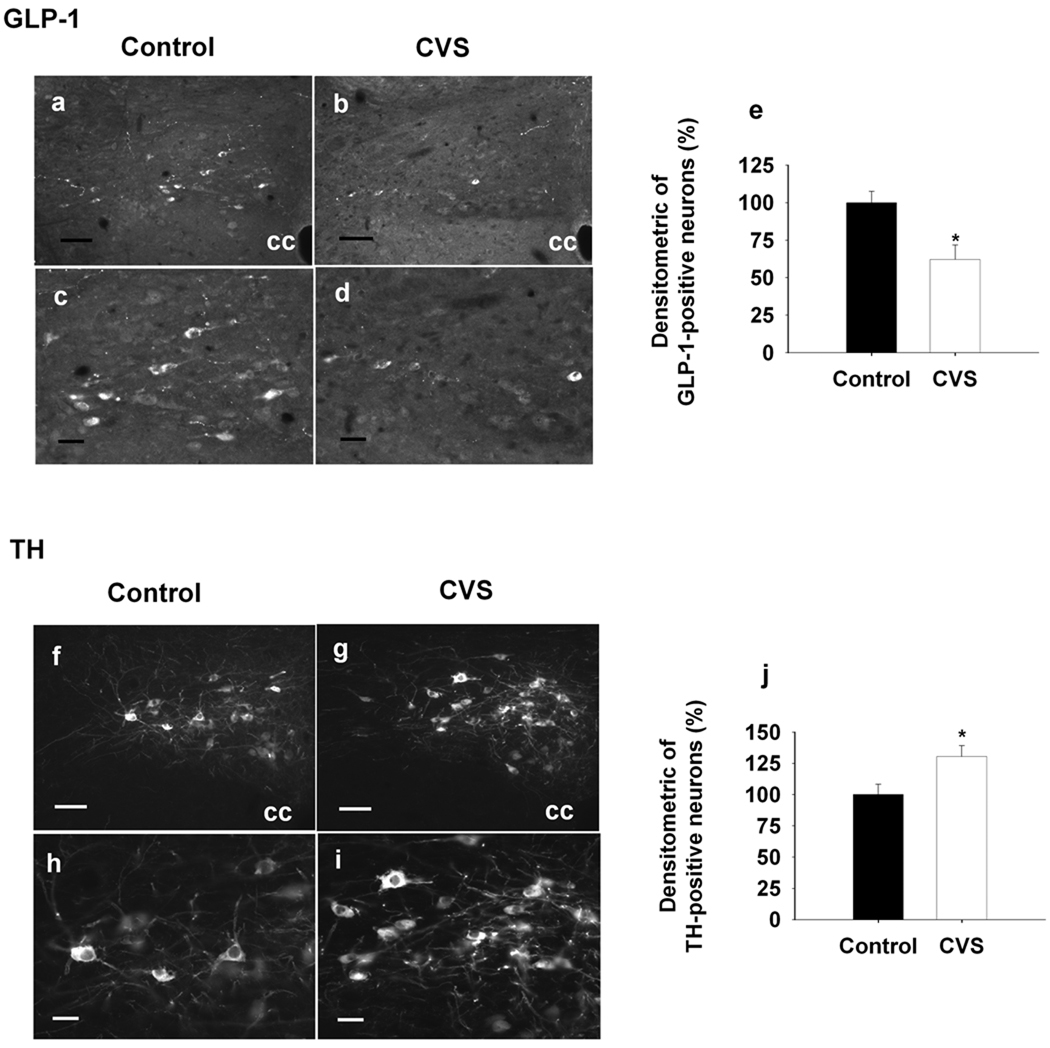

We also evaluated GLP-1 peptide and TH immunoreactivity in the caudal medulla, using fluorescence densitometry. Cellular expression of GLP-1 immunoreactivity was substantially reduced in NTS neurons following CVS (F(1,11)=7.70, P<0.05) (Fig4. a, b, c, d, e). Decreases in GLP-1 were specific to cells situated caudal (Bregma −14.52) to the obex (Bregma −14.40). In contrast, TH immunoreactivity was selectively enhanced in NTS neurons located rostral (Bregma −14.28) to the obex (F(1,12)=6.48, P<0.05) (Fig4. f, g, h, I, j). As previously reported, no GLP-1/TH co-localization was observed in the NTS (data not shown). Together, the data confirm that CVS modulation of mRNA levels are also manifest as changes in peptide/ transmitter, and suggest that CVS-responsive PPG and TH neurons are compartmentalized to different regions of the NTS.

Figure 4.

Quantification of the densitometrics of GLP-1- and TH-IR positive neurons in the NTS after 2-weeks CVS exposure. a, b, c, d & f, g, h, i, Representative images of GLP-1- and TH-IR positive staining at the level of Bregma −14.40, the upper panels (a, b, f, g) are low magnification images and below panels (c, d, h, i) are high magnification images, left side, Control; right side, CVS. e, Decrement of the densitometrics of NTS GLP-1-IR positive neurons in the CVS-treated rats compared to the control group. j, Increment of densitometrics of NTS TH-IR positive neurons in the CVS-treated rats compared to the control animals. Data are shown as the percentage of control. cc. central canal, Scale bars, 50um for low-magnification images (a, b, f, g); 20 um for high magnification images (c, d, h, i). *, P<0.05 vs. Control.

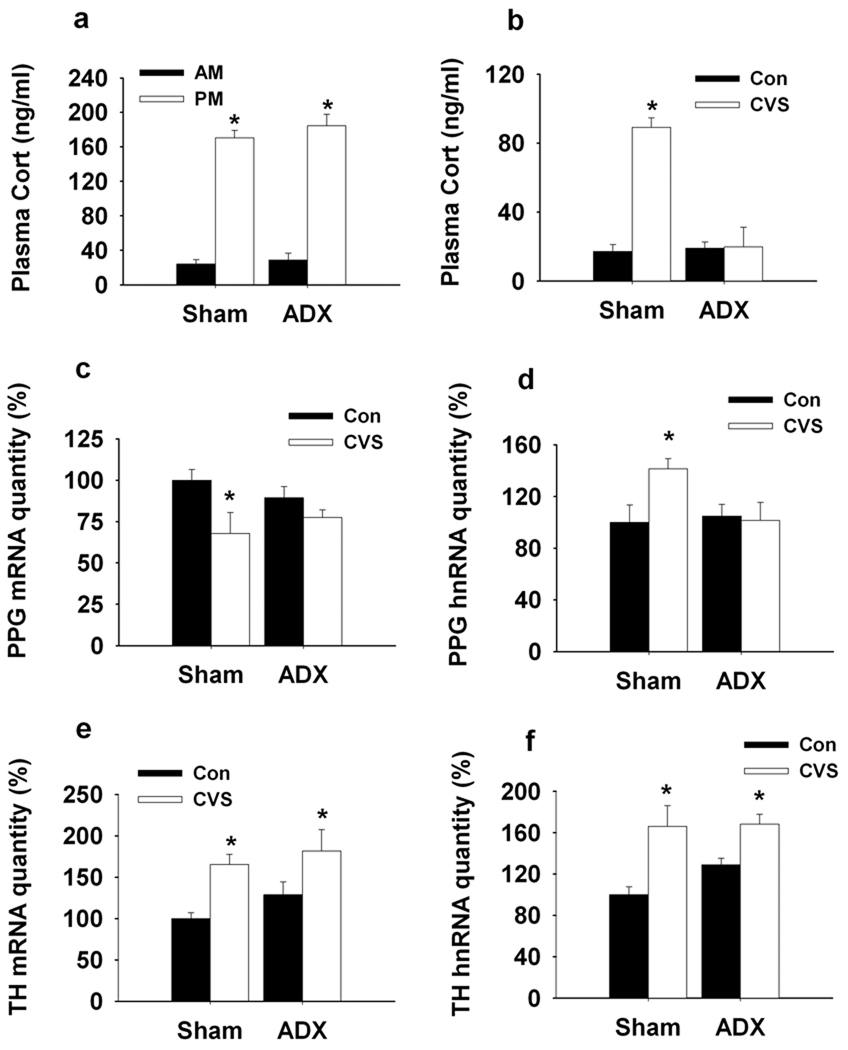

Stress-induced glucocorticoids secretion is necessary for NTS PPG mRNA down-regulation

Subsequent studies explored the role of CVS-induced glucocorticoid secretion in modulation of PPG and TH mRNA/hnRNA expression. To assess the necessity of glucocorticoids in gene regulation, we employed an adrenalectomy-corticocosterone (ADX-Cort) replacement model that affords maintenance of physiological glucocorticoid availability across the day-night cycle by providing exogenous corticosterone in the drinking water. Our data indicate resting AM and PM corticosterone levels did not differ between the ADX-Cort replacement group and sham-ADX rats (Fig5. a). As expected, exposure to CVS did not alter resting AM corticosterone in the ADX-Cort replaced group (main effect of Surgery (F(1,27)=48.70, P<0.01), main effect of CVS (F(1,27)=64.40, P<0.01) and Surgery × CVS interaction (F(1,27)=53.65, P<0.01) (Fig5. b). Sham ADX animals showed the standard indices of CVS-induced HPA axis up-regulation (increased resting corticosterone, thymic atrophy, adrenal hypertrophy) (SI Fig. 3).

Figure 5.

Q RT-PCR analysis of the regulation of NTS PPG and TH transcription by CVS exposure in ADX-Cort replaced rats. a, Diurnal rhythms of plasma corticosterone was determined. ADX-Cort rats showed normal plasma corticosterone circadian as indicated by no difference for nadir and peak of plasma corticosterone between Sham-ADX and ADX-Cort rats. b, The basal plasma corticosterone was elevated by CVS exposure only in Sham-ADX CVS rats. Prolonged stress challenge did not affect the basal plasma corticosterone in ADX-Cort rats. c, d, CVS exposure enhanced PPG mRNA degradation and PPG hnRNA expression in Sham-ADX rats. There was no difference for PPG mRNA and hnRNA expression between unstressed and stressed ADX-Cort rats. e, f, Expression of TH mRNA and hnRNA were elevated by the 2-weeks CVS exposure in both Sham-ADX and ADX-Cort rats. *, P < 0.01 vs. Control.

Analysis of PPG and TH gene regulation revealed a differential effect of CVS-induced glucocorticoid secretion on the two brainstem stress systems. In the case of PPG, down-regulation of PPG mRNA and up-regulation of PPG hnRNA were completely blocked in ADX-replaced rats, which did not have twice-daily fluctuations in corticosterone levels in response to CVS stressors. There was a significant surgery-CVS interaction F(1, 23)=4.19, P<0.05) but no main effect of surgery or CVS, suggesting that lack of glucocoticoid response to stress blocked the effect of CVS on the initiation of PPG transcription. (Fig5. c, d). In contrast, ADX-replacement had no significant impact on NTS TH mRNA or hnRNA expression (CVS: F(1, 18)=17.28, P<0.05) (Fig5. e, f).

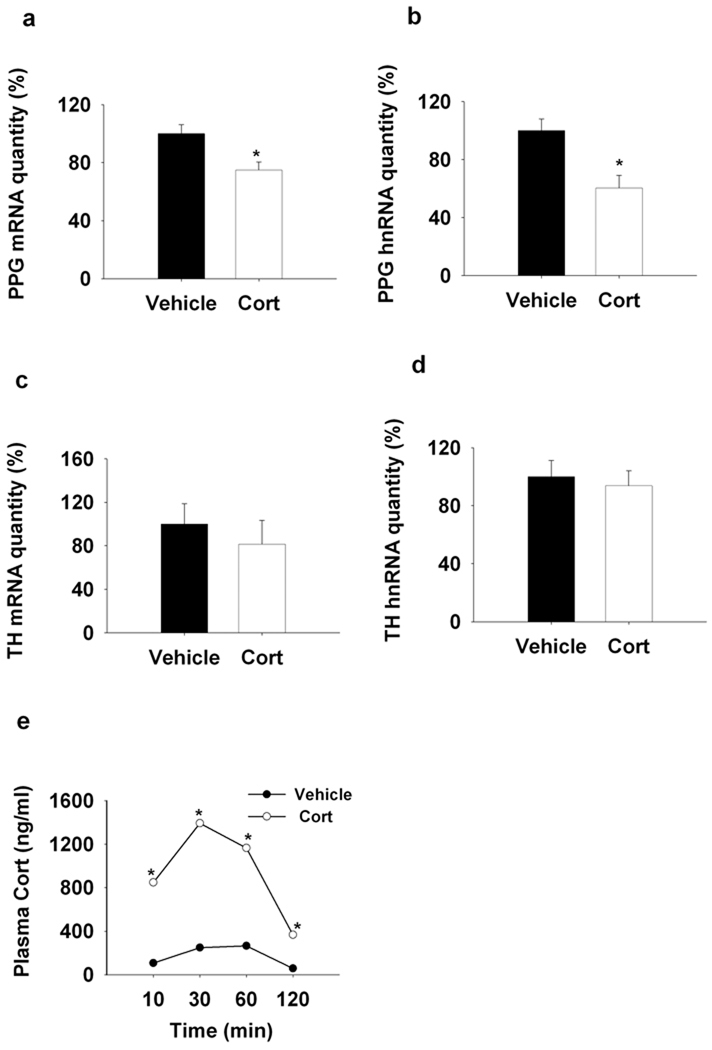

Exogenous glucocorticoids are sufficient for NTS PPG mRNA down-regulation

Next, we tested whether chronic episodic elevations in glucocorticoids were sufficient to modulate PPG or TH mRNA/hnRNA expression in the NTS in the absence of concurrent stress. Chronic intermittent injections of exogenous corticosterone decreased PPG mRNA expression, similar to that seen following CVS (F(1,19)=9.003, P < 0.01) (Fig6. a). However, PPG hnRNA was also decreased by chronic glucocorticoid treatment, indicating that glucocorticoids and stress may interact in regulation of PPG transcription (F(1,18)=12,56, P < 0.01) (Fig6. b). Notably, chronic glucocorticoid exposure did not alter either TH mRNA or hnRNA (Fig6. c, d).

Figure 6.

Q RT-PCR analysis of the regulation of NTS PPG and TH transcription by chronic s.c. administration of corticosterone (3.5mg/kg). a,b Chronic injection of corticosterone decreased PPG mRNA and hnRNA expression compared to the vehicle treatment. c, d, Chronic corticosterone injection did not affect the NTS TH gene expression. e, The plasma corticosterone level was increased by acute s.c. injection of corticosterone at 10mim, reached the peak at 30min and maintained elevated levels at 60min and 120min when compared to the vehicle injection. *, P < 0.05 vs. Control.

Our studies indicate that subcutaneous injection of corticosterone at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg is sufficient to emulate a physiological stress response, with corticosterone rising within 10 minutes and attaining peak levels at 30 minutes, comparable to an acute stress-induced plasma corticosterone surge. There were main effects of drug (F(1,63)=349.92, P<0.01) and time (F(3,63)=53.09, P<0.01), as well as a significant drug × time interaction (F(3,63)=22.31, P<0.01) (Fig6. e). Thymus weight and adrenal weight were both decreased by corticosterone injection (See SI Fig. 4), consistent with enhanced glucocorticoid availability and reduced ACTH release subsequent to enhanced exogenous feedback. These data are in agreement with previous reports (Young et al., 1995).

Discussion

The results of this study document divergent regulation of brainstem GLP-1 and NE/E neurons following chronic stress exposure. Exposure to chronic stress significantly reduced PPG mRNA expression in a glucocorticoid-dependent fashion, indicating that stress-induced glucocorticoid release produces long-term PPG down-regulation. In contrast, TH mRNA and initial gene transcription increased following CVS in a glucocorticoid-independent fashion. Differential chronic stress regulation of two putative stress-excitatory systems is consistent with selective involvement in different aspects of stress regulation.

Previous work by our group demonstrated down-regulation of PPG mRNA, up-regulation of PPG hnRNA and decreased PVN GLP-1 fiber staining following acute stressors. In our prior study, PPG mRNA/hnRNA expression returned to normal levels within two hours of stress cessation, suggesting that transcriptional drive initiated by the stress exposure repleted mature PPG mRNA fairly quickly (Zhang et al., 2009). The current study suggests that chronic stress causes down-regulation of NTS PPG mRNA and PVN GLP-1 fiber staining that persists at least 16 h following cessation of the last stressor, suggesting long-lasting rather than transient reductions in PPG action in the CNS following CVS. Since PPG hnRNA was increased by CVS, the data are consistent with cumulative effects of repeated stress on factors influencing steady-state PPG mRNA levels.

Our studies suggest glucocorticoids as causal factors in long-term PPG down-regulation. Adrenalectomy with physiological replacement blocked the ability of chronic stress to decrease PPG mRNA expression, whereas twice-daily administration of corticosterone was sufficient to drive down PPG mRNA expression in the absence of concurrent stress. These data suggest that cumulative or episodic exposures to stress-induced glucocorticoid elevations are necessary and sufficient to down-regulate PPG gene expression in a long-term fashion. Glucocorticoids are known to regulate RNA stability through binding to and facilitating mRNA degradation, perhaps via interactions with RNA binding proteins (Dhawan et al., 2007; Ishmael et al., 2008), suggesting a possible means for long-term destabilization of PPG mRNA, even in the face of enhanced transcription. In addition, glucocorticoids may promote transcription of RNA binding proteins or perhaps microRNAs that specifically target PPG mRNA for enhanced degradation (Ing, 2005; Hobert, 2007; Rainer et al., 2009). Of note, the 3’-untranslated region of PPG mRNA has recognition sequences for known microRNA species (Zhang et al., 2009).

Interestingly, exogenous corticosterone decreased PPG hnRNA, which was an effect opposite that observed as a consequence of CVS. However, as demonstrated in the adrenalectomized animals, this latter effect was dependent on stimulated release of adrenal products. The divergent effects of CVS and stress-free of glucocorticoid administration suggest that neural and hormonal events associated with stress in the context of elevated corticosterone are sufficient to enhance PPG transcription, whereas elevated corticosterone in the absence of stress signals has an opposite action.

In contrast to the observed effects on PPG mRNA, chronic stress increased TH mRNA expression and transcription in a glucocorticoid-independent manner. Coupled with our previous observations documenting enhanced DBH innervation of PVN CRH neurons (Flak et al., 2009), the data suggest that chronic stress increases the capacity of NE/E activation in critical stress integrative pathways. Up-regulation of TH mRNA in response to CVS appears to be particularly robust in cell groups rostral to the obex, corresponding to the region containing the majority of psychogenic stress activated, paraventricular nucleus-projecting NE/E neurons (Dayas et al., 2001). Thus, stress up-regulation is likely dependent on chronic drive of stress effector pathways projecting to the NTS.

Our data are consistent with previous studies documenting chronic stress-induced increases in TH mRNA expression in other stress models. For example, chronic stress exposure enhances expression of TH mRNA in the locus coeruleus, sympathetic ganglia and adrenal medulla (c.f., (Sabban and Kvetnansky, 2001)), suggesting that paradigms promoting sympathoadrenal activation produce generalized activation across multiple NE/E systems. In addition, previous studies demonstrate that both acute and chronic stress-related increases in locus coeruleus TH mRNA expression are independent of glucocorticoid secretion (Smith et al., 1991; Makino et al., 2002). These data suggest that chronic stress-induced changes in TH mRNA are refractory to glucocorticoid influence in other stress-regulated regions as well.

The corticosterone replacement and administration regimens used in this study were designed to emulate normal diurnal corticosterone secretion (in ADX rats) and twice-daily stress responses, respectively. We were able to demonstrate normal AM and PM corticosterone levels in ADX rats by providing the corticosterone in the drinking saline, in a manner similar to that observed by Jacobson and colleagues (Jacobson et al., 1990) (Akana et al., 1985). After an initial surgery-related weight loss, weight gain in ADX-replaced rats paralleled that of sham controls. Thus, the ADX-Cort replacement regimen was sufficient to produce normal daily glucocorticoid secretion without mounting the glucocorticoids release under the stress stimulation. However, PPG mRNA expression was reduced in ADX- Cort replaced animals relative to the controls, suggesting that corticosterone replacement does not completely compensate for the effects of adrenal removal on the NTS PPG.

Twice-daily corticosterone administration produced corticosterone pulses similar in character to those seen after twice daily acute stress exposure in our CVS regimen. Notably, twice-daily corticosterone elicited thymic atrophy, confirming the cumulative efficacy of the corticosterone administration. In addition, significant retardation of weight-gain was observed with chronic corticosterone exposure, a phenomenon also observed after chronic stress exposure in a variety of models, implicating glucocorticoids in stress-induced hypophagia.

Both GLP-1 and catecholamines activate stress effector pathways in the brain, including the HPA axis (Plotsky et al., 1989b; Kinzig et al., 2003) and the sympathethic nervous system (Yamamoto et al., 2002). Concurrent glucocorticoid-dependent down-regulation of PPG and glucocorticoid- independent increment of NE/E biosynthetic capacity and availability suggests that chronic stress down-regulates one stress-excitatory pathway (GLP-1) while up-regulating another (NE/E). On this basis, we postulate two very different roles for the two systems in stress adaptation. In the case of GLP-1, our previous studies indicate that chronic GLP-1 receptor blockade inhibits CVS-induced HPA axis hyperactivity, whereas GLP-1 supplementation exacerbates the impact of CVS on HPA axis sensitization and cumulative corticosterone exposure (as inferred from decrements in thymus weight) (Tauchi et al., 2008b). Given the stress-excitatory role of GLP-1 in CNS, the glucocorticoid-dependent reduction of GLP-1 suggests a role for glucocorticoids in negative feedback regulation via the NTS. Thus, down-regulation of GLP-1 signaling may represent corticosterone-initiated adaptive mechanism involved in stress habituation.

In contrast to the GLP-1 system, CNS NE is involved in sensitization of chronic stress responses at several levels of the neuraxis, including the PVN. Although chronic stress results in tonic elevations in plasma corticosterone, the HPA axis in stressed rats usually exhibits full responsiveness to new, acutely applied stress. It is known that exposure to a prior stressor can facilitate the actions of a second stressor (Akana et al., 1992). Thus, up-regulation of NTS NE/E systems may serve to permit the animal to respond to novel threats in the face of concurrent chronic stress, providing a sensitization mechanism to insure that the organism can rise to meet new physiologic challenges. The NE/E system acts as a mechanism to insure that stress-induced, endogenous corticosterone feedback signals do not completely inhibit the HPA axis tone. Thus, it seems appropriate that the CVS enhanced NE/E expression is independent of the chronic stress-induced glucocorticoids, in order to preserve stress responsiveness in the face of chronically elevated corticosterone levels.

Overall, our study supports a differential role for PPG and NE/E systems in the management of responses to chronic stress. Stress-related disease states, such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, are known to be accompanied by dyshomeostasis in hormonal and autonomic stress effector pathways (Carroll et al., 1976; Kathol et al., 1989; Barefoot et al., 1996). Our data suggest that imbalance of stress habituation and sensitization inputs arising from brainstem stress relays may play a role in regulating onset and/or severity of stress-related disease processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yve Ulrich-Lai for assistance with ADX surgeries and helpful discussion, Kenneth Jones and Ingrid Thomas for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MH069860 (to J.P.H. and D.A.D.) and MH049698 (to J.P.H.).

References

- Ahima RS, Harlan RE. Charting of type II glucocorticoid receptor-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1990;39:579–604. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akana SF, Cascio CS, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Corticosterone: narrow range required for normal body and thymus weight and ACTH. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:R527–R532. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.249.5.R527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akana SF, Dallman MF, Bradbury MJ, Scribner KA, Strack AM, Walker CD. Feedback and facilitation in the adrenocortical system: unmasking facilitation by partial inhibition of the glucocorticoid response to prior stress. Endocrinology. 1992;131:57–68. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.1.1319329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot JC, Helms MJ, Mark DB, Blumenthal JA, Califf RM, Haney TL, O'Connor CM, Siegler IC, Williams RB. Depression and long-term mortality risk in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:613–617. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ, Curtis GC, Mendels J. Neuroendocrine regulation in depression. II. Discrimination of depressed from nondepressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1051–1058. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090041003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collie NL, Walsh JH, Wong HC, Shively JE, Davis MT, Lee TD, Reeve JR., Jr Purification and sequence of rat oxyntomodulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9362–9366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro N, Akana SF, La Fleur SE, Gomez F, Houshyar H, Bell ME, Bhatnagar S, Laugero KD, Manalo S. Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of "comfort food". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11696–11701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934666100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas CV, Buller KM, Crane JW, Xu Y, Day TA. Stressor categorization: acute physical and psychological stressors elicit distinctive recruitment patterns in the amygdala and in medullary noradrenergic cell groups. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1143–1152. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan L, Liu B, Blaxall BC, Taubman MB. A novel role for the glucocorticoid receptor in the regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA stability. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10146–10152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flak JN, Ostrander MM, Tasker JG, Herman JP. Chronic stress-induced neurotransmitter plasticity in the PVN. J Comp Neurol. 2009;517:156–165. doi: 10.1002/cne.22142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillet S, Lachuer J, Malaval F, Assenmacher I, Szafarczyk A. The involvement of noradrenergic ascending pathways in the stress-induced activation of ACTH and corticosterone secretions is dependent on the nature of stressors. Exp Brain Res. 1991;87:173–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00228518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Kawata M, Loewy AD. Aldosterone-sensitive neurons in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:515–527. doi: 10.1002/cne.20808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Adams D, Prewitt C. Regulatory changes in neuroendocrine stress-integrative circuitry produced by a variable stress paradigm. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;61:180–190. doi: 10.1159/000126839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. miRNAs play a tune. Cell. 2007;131:22–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo L, Grill HJ, Bjorbaek C. Divergent regulation of proopiomelanocortin neurons by leptin in the nucleus of the solitary tract and in the arcuate hypothalamic nucleus. Diabetes. 2006;55:567–573. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ing NH. Steroid hormones regulate gene expression posttranscriptionally by altering the stabilities of messenger RNAs. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:1290–1296. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.040014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishmael FT, Fang X, Galdiero MR, Atasoy U, Rigby WF, Gorospe M, Cheadle C, Stellato C. Role of the RNA-binding protein tristetraprolin in glucocorticoid-mediated gene regulation. J Immunol. 2008;180:8342–8353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L, Sharp FR, Dallman MF. Induction of fos-like immunoreactivity in hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor neurons after adrenalectomy in the rat. Endocrinology. 1990;126:1709–1719. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-3-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathol RG, Jaeckle RS, Lopez JF, Meller WH. Pathophysiology of HPA axis abnormalities in patients with major depression: an update. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:311–317. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzig KP, D'Alessio DA, Seeley RJ. The diverse roles of specific GLP-1 receptors in the control of food intake and the response to visceral illness. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10470–10476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10470.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzig KP, D'Alessio DA, Herman JP, Sakai RR, Vahl TP, Figueredo HF, Murphy EK, Seeley RJ. CNS glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors mediate endocrine and anxiety responses to interoceptive and psychogenic stressors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:6163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06163.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PJ, Tang-Christensen M, Holst JJ, Orskov C. Distribution of glucagon-like peptide-1 and other preproglucagon-derived peptides in the rat hypothalamus and brainstem. Neuroscience. 1997;77:257–270. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liposits Z, Sherman D, Phelix C, Paull WK. A combined light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical method for the simultaneous localization of multiple tissue antigens. Tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive innervation of corticotropin releasing factor synthesizing neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the rat. Histochemistry. 1986;85:95–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00491754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Smith MA, Gold PW. Regulatory role of glucocorticoids and glucocorticoid receptor mRNA levels on tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the locus coeruleus during repeated immobilization stress. Brain Res. 2002;943:216–223. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti O, Gavalda A, Gomez F, Armario A. Direct evidence for chronic stress-induced facilitation of the adrenocorticotropin response to a novel acute stressor. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000126713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New Youk: Elsevier Academc Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky PM. Facilitation of immunoreactive corticotropin-releasing factor secretion into the hypophysial-portal circulation after activation of catecholaminergic pathways or central norepinephrine injection. Endocrinology. 1987;121:924–930. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-3-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky PM, Cunningham ET, Jr, Widmaier EP. Catecholaminergic modulation of corticotropin-releasing factor and adrenocorticotropin secretion. Endocrine Rev. 1989a;10:437–458. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-4-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky PM, Cunningham ET, Jr, Widmaier EP. Catecholaminergic modulation of corticotropin-releasing factor and adrenocorticotropin secretion. Endocr Rev. 1989b;10:437–458. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-4-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainer J, Ploner C, Jesacher S, Ploner A, Eduardoff M, Mansha M, Wasim M, Panzer-Grumayer R, Trajanoski Z, Niederegger H, Kofler R. Glucocorticoid-regulated microRNAs and mirtrons in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:746–752. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter S, Watts AG, Dinh TT, Sanchez-Watts G, Pedrow C. Immunotoxin lesion of hypothalamically projecting norepinephrine and epinephrine neurons differentially affects circadian and stressor-stimulated corticosterone secretion. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1357–1367. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Kvetnansky R. Stress-triggered activation of gene expression in catecholaminergic systems: dynamics of transcriptional events. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01687-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Fekete C, Legradi G, Lechan RM. Glucagon like peptide-1 (7–36) amide (GLP-1) nerve terminals densely innervate corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res. 2003;985:163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Central noradrenergic pathways for the integration of hypothalamic neuroendocrine and autonomic responses. Science. 1981;214:685–687. doi: 10.1126/science.7292008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulkin J, McEwen BS, Gold PW. Allostasis, amygdala, and anticipatory angst. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:385–396. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber JS, Kapp BS, Higgins GA, PR R. Amygdala and basal forebrain direct connections with the nucleus of the solitary tract and the dorsal motor nucleus. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1424–1438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-10-01424.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Brady LS, Glowa J, Gold PW, Herkenham M. Effects of stress and adrenalectomy on tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels in the locus ceruleus by in situ hybridization. Brain Res. 1991;544:26–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90881-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafarczyk A, Malaval F, Laurent A, Gibaud R, Assenmacher I. Further evidence for a central stimulatory action of catecholamines on adrenocorticotropin release in the rat. Endocrinology. 1987;121:883–892. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-3-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauchi M, Zhang R, D'Alessio DA, Stern JE, Herman JP. Distribution of glucagon-like peptide-1 immunoreactivity in the hypothalamic paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. J Chem Neuroanat. 2008a;36:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauchi M, Zhang R, D'Alessio DA, Seeley RJ, Herman JP. Role of central glucagon-like peptide-1 in hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical facilitation following chronic stress. Exp Neurol. 2008b;210:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uht RM, McKelvy JF, Harrison RW, Bohn MC. Demonstration of glucocorticoid receptor-like immunoreactivity in glucocorticoid-sensitive vasopressin and corticotropin-releasing factor neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neurosci Res. 1988;19:405–411. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490190404. 468-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Figueiredo HF, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Engeland WC, Herman JP. Chronic stress induces adrenal hyperplasia and hypertrophy in a subregion-specific manner. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E965–E973. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00070.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP. Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse. 2004;51:32–58. doi: 10.1002/syn.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Lee CE, Marcus JN, Williams TD, Overton JM, Lopez ME, Hollenberg AN, Baggio L, Saper CB, Drucker DJ, Elmquist JK. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor stimulation increases blood pressure and heart rate and activates autonomic regulatory neurons. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:43–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI15595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Kwak SP, Kottak J. Negative feedback regulation following administration of chronic exogenous corticosterone. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7:37–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Packard BA, Tauchi M, D'Alessio DA, Herman JP. Glucocorticoid regulation of preproglucagon transcription and RNA stability during stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5913–5918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808716106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.