INTRODUCTION

A number of observational studies have reported that hearing loss negatively impacts quality of life (QOL).1–5 Among the participants in the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study (EHLS), significant relationships between severity of hearing loss and impaired physical and social functioning were found.1 Furthermore, additional studies have reported a positive influence of hearing aid usage on QOL.6–12 A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies related to hearing aids and QOL, concluded that aid usage in adults was associated with improvements in psychological, social, and emotional well-being when hearing and communication-specific measures were used for QOL assessment.6 In a randomized trial among older patients at Veterans Affairs clinics, results suggested that hearing aid use led to significant improvements in social and emotional functioning, communication, cognition and depression with all effects except cognition being sustained for at least one year.7,8

Despite the psycho-social benefits of hearing aid use, it has been estimated that just 20–25% of hearing impaired individuals use hearing aids.13–15 Focusing on older adults (70 years of age and older), it has been reported that in 1995, only about one-third of subjects with a reported hearing problem had used hearing aids within the past year.16

Previous work evaluating characteristics related to seeking help for a hearing loss and obtaining hearing aids has been conducted through clinic-based investigations and cross-sectional population studies and surveys. In general, the factors found to have an influence on the decision to seek help include a lowered self-perception of hearing ability or decline in hearing sensitivity, negative impact of hearing quality on daily life, and comments/encouragement from others.17–20 Conversely, studies investigating characteristics associated with not seeking treatment for a hearing loss, have found that denial of the loss, self-image implications, the fear of social consequences and aging, the acceptance of a hearing loss as a normal part of the aging process, and lack of social pressure play a role.18,21 Hearing aids in particular are not sought because of concerns regarding cost, effectiveness, stigma and discomfort.18,21,22

Prior studies have not been population-based and prospective in nature and have not evaluated multiple factors simultaneously, including demographic characteristics, standard measures of hearing ability, and self-perception of hearing quality and handicap. Some studies have been conducted in clinical populations in which subjects have already made a decision to seek help for a perceived hearing loss.17,20 Factors influencing the decision to acquire a hearing aid may differ among patients seen at an audiology clinic versus participants in a population-based study of aging. Investigators in the Netherlands have conducted population studies but these have been cross-sectional in design and in the Netherlands the cost of a hearing aid may be partially reimbursed, either through public funding or the employer.18,19 Since cost may be an important factor in the decision to acquire a hearing aid, the results of the studies conducted in the Netherlands may be expected to differ from studies conducted in the United States where hearing aids are not universally covered by private health insurance or by Medicare. Survey work investigating the prevalence of hearing aid use in the United States relied on self-reported hearing loss or hearing difficulty which may introduce error and prevents any adjustment for measured hearing loss.21,22 In addition, the survey work is subject to response bias and may not be representative of the general population. The objective of this population-based study was to estimate, for the first time, the 10-year incidence of hearing aid acquisition among subjects with a demonstrated hearing loss and to determine the factors which predicted hearing aid purchase.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were residents of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin who had participated in the EHLS and the Beaver Dam Eye Study (BDES). The BDES began recruitment in 1987–88 by inviting all residents, aged 43 through 84 years, of the city or township of Beaver Dam to participate in a population-based study of age-related eye disorders. Of the 5,924 eligible residents, 4,926 (83%) were examined in the first BDES phase conducted in 1988–90. The first follow-up BDES examination was performed five years later, in 1993–95, and concurrently, the baseline EHLS examination (EHLS-1) was conducted. There were 3,753 subjects (82.6% of the 4,541 living subjects) who participated in EHLS-1. Follow-up studies were conducted 5 years (EHLS-2) and 10 years (EHLS-3) after baseline. Additional details have been reported.23–25 Institutional Review Board approval by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin and informed consent were obtained.

Subjects included in this study had a demonstrated hearing loss, either at EHLS-1 or EHLS-2, defined as a pure-tone threshold average (PTA) at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz, greater than 25 dB (decibel) HL (Hearing Level) in the better ear. Subjects had no history of hearing aid use prior to the detection of a hearing loss.

Measurements

Audiometry

Pure-tone air-conduction thresholds (measured as decibel Hearing Level) were determined during each study period according to the American Speech Language and Hearing Association (ASHA) guidelines.26 American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards were followed for equipment calibration.27,28 Thresholds were measured in both ears at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 kHz and three PTAs of the better ear were calculated: average of the 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz thresholds, the 0.5, 1, and 2 kHz thresholds and the 4, 6, and 8 kHz thresholds. The female talker version of the NU-6 test (Northwestern University Auditory Test No. 6) was used for word recognition testing, conducted in quiet and competing message. Word lists were presented at 36 dB above the 2 kHz threshold in the better ear. For competing message, a single male talker was included at 8dB below the female voice.29,30 Word recognition scores consisted of the percent of words the participant correctly stated. Previous publications include audiometric procedure details.23,30

Hearing Aid Acquisition

Hearing aid usage was self-reported in response to: “Have you ever worn a hearing aid or amplifying device?”. To be included, subjects must have given an answer of ‘No’ at the time of the EHLS examination during which the hearing loss was first detected. Hearing aid acquisition was considered to have occurred if, at the EHLS examination(s) following the identification of a hearing loss detection (EHLS-2 or EHLS-3), the subject gave an answer of ‘Yes’ to the question.

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, education, marital status (currently married, not married), self-perception of hearing quality (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), self-perception of loss (“Do you feel you have a hearing loss?”), perception of friends and relatives with respect to the participant’s hearing, self-reported family history of hearing loss (father, mother, and/or siblings), impaired cognition, and the HHIE-S score.31 Education was modeled as a 4 level class variable (< 12 years, 12 years, 13–15 years and 16+ years) and as a dichotomous variable, 16+ years (termed College Graduate) versus < 16 years. Impaired cognition was defined as a score of less than 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination or a report of dementia by a proxy.32 The HHIE-S consists of 10 questions measuring the perceived social/situational and emotional effects of a hearing problem. Possible responses for each question are ‘No’ (0 points), ‘Yes’ (4 points), and ‘Sometimes’ (2 points). Points are added across the 10 questions and thus, the HHIE-S score ranges from 0 to 40 points with higher values indicating a greater degree of perceived handicap related to a hearing problem. For self-perception of hearing quality, because of small numbers the categories of excellent, very good and good were combined.

Statistical Analyses

The follow-up period was divided into two five-year segments, corresponding with the EHLS study phases. For subjects whose hearing loss was diagnosed at EHLS-1, the first five-year segment (0–5 years of follow-up) began at EHLS-1 and ended at EHLS-2 at which time hearing aid usage was ascertained. If the subject did not then report using a hearing aid, the second five-year segment (5–10 years of follow-up) began at EHLS-2 and ended at EHLS-3 at which time hearing aid usage was again ascertained. For subjects who did not have a hearing loss at EHLS-1 but did at EHLS-2, the first (and only) five-year segment (0–5 years of follow-up) began at EHLS-2 and ended at EHLS-3.

To determine the strength of association between hearing aid acquisition and the covariates, Cox discrete-time proportional hazards modeling was used. For categorical factors, a reference category was chosen and indicator variables were created for the remaining categories. Dichotomous factors were entered as 0–1. The covariate measurements collected at the beginning of each follow-up period were used with the exception of impaired cognition. Since the MMSE was not administered at EHLS-1, the cognition status determined at the end of each follow-up period was used.

Initial modeling was performed for each of the covariates separately with age and sex adjustment only. All covariates were considered for the multivariate model and selection of the final model was done in a stepwise fashion. Since education and income were strongly correlated and provided approximately the same goodness of fit, education was chosen for the final model to increase sample size (there was more missing data for income). Hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were computed from the parameter estimates and their standard errors. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

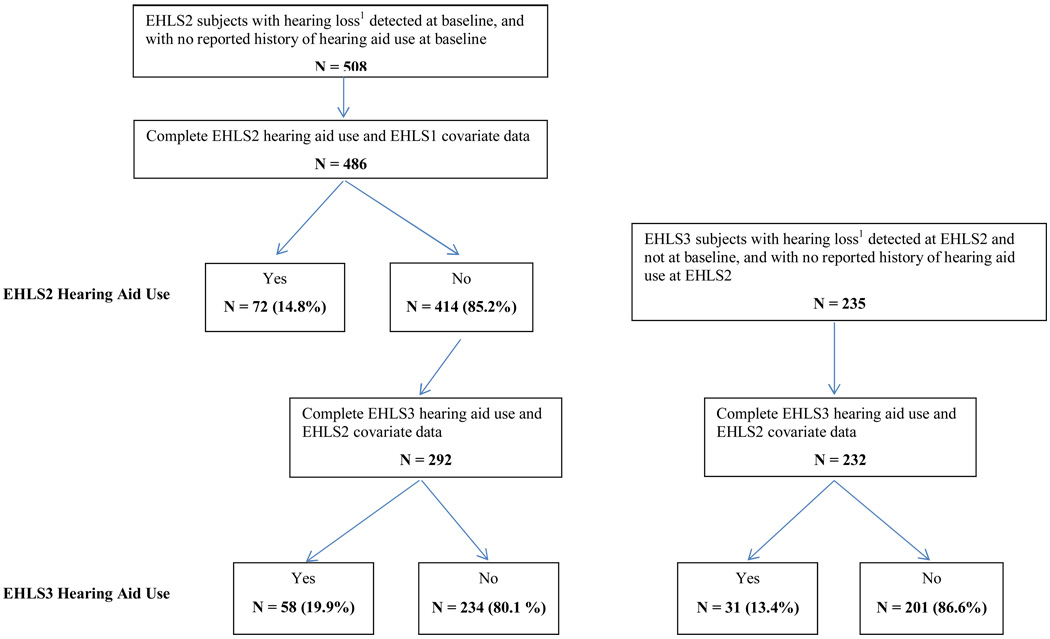

There were 718 subjects (mean age = 70.5 years) with a hearing loss who were followed for at least 5 years (Figure 1). Among these subjects, the 5-year incidence of hearing aid acquisition was 14.3%. The 5-year incidence of aid acquisition was 14.8% for the 486 subjects whose hearing loss was detected at EHLS-1 (baseline) and 13.4% for the 232 subjects whose loss was detected at EHLS-2. The 10-year cumulative incidence of hearing aid acquisition was 35.7% (130/364). Approximately 20% of the subjects followed for 10 years acquired a hearing aid 5 to 10 years after a hearing loss was initially detected.

Figure 1.

Study Population Selection and Incidence of Hearing Aid Acquisition

1Hearing loss defined as PTA0.5, 1,2,4 kHz, better ear > 25 dB HL

Results of age and sex adjusted analyses are presented in Table 1. Hearing aid acquisition was associated with education and a number of perceived hearing factors and hearing capacity measurements (Table 1). College graduation significantly increased the likelihood of acquiring an aid (HR=1.8 (95% C.I.=1.1,2.9) and this relationship was stronger in the period of 5–10 years after hearing loss detection (HR=2.6, 95% C.I.=1.1,6.1). Higher income also demonstrated a non-significant, positive relationship with hearing aid acquisition. Regarding the perceived hearing factors, there was a significant linear association between perceived hearing quality and aid acquisition (p < 0.01) with those reporting poor quality having a rate ratio equal to 6.2 (95% C.I.=3.5,11.0) compared to those reporting excellent, very good or good hearing. In the first 5 years of follow-up after hearing loss detection, while only 9.5% of the subjects who rated their hearing as good or better acquired an aid, close to 36% of subjects who perceived their hearing as poor acquired an aid. In the 5–10 year follow-up period, nearly 41% of the subjects who reported poor hearing obtained an aid compared to about 13% of the subjects reporting good or better hearing. Self-perception of hearing loss and having friends or relatives think that the participant has a hearing loss resulted in a rate of aid acquisition over 3 times the rate of those without these perceptions. A family history of hearing loss was also found to be significantly associated with hearing aid acquisition (HR=1.8, 95% C.I.=1.2,2.6) as was the perceived degree of handicap related to hearing (HR1 unit of HHIE score =1.08, 95% C.I.=1.06,1.11). With respect to the measurements of hearing ability, a higher PTA was associated with significantly elevated rates of aid acquisition, particularly for the average of the 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz thresholds (+5 dB difference: HR=1.5, 95% C.I.=1.3,1.7). Higher word recognition scores in quiet (HR=0.97, 95% C.I.=0.96,0.99) and competing message (HR=0.98, 95% C.I.=0.97,0.99) resulted in lower rates of acquiring hearing aids.

Table 1.

Distribution of Risk Factors for Incidence of Hearing Aid Acquisition Age and Sex Adjusted Hazard Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals)

| Years of Follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 Years of Follow-up | 5–10 Years of Follow-up | Periods Combined | |||||

| Percentage | Percentage | ||||||

| Risk Factor | Aid (N=103) | No Aid (N=615) | Hazard Ratio | Aid (N=58) | No Aid (N=234) | Hazard Ratio | Hazard Ratio |

| Male | 57.3 | 54.0 | 1.23 (0.78,1.92) | 44.8 | 61.5 | 0.58 (0.32,1.07) | 0.95 (0.66,1.36) |

| Education | |||||||

| <12 | 28.2 | 27.3 | 1.00 | 25.9 | 25.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 12 | 48.5 | 48.9 | 1.00 (0.60,1.64) | 46.6 | 53.0 | 0.91 (0.45,1.87) | 0.97 (0.65,1.46) |

| 13–15 | 7.8 | 13.3 | 0.58 (0.25,1.33) | 10.3 | 12.8 | 0.78 (0.27,2.26) | 0.66 (0.35,1.25) |

| 16+ (College Graduate) | 15.5 | 10.4 | 1.47 (0.74,2.90) | 17.2 | 9.0 | 2.38 (0.89,6.36) | 1.69 (0.97,2.95) |

| College Graduate | 15.5 | 10.4 | 1.57 (0.86,2.84) | 17.2 | 9.0 | 2.59 (1.10,6.09) | 1.81 (1.12,2.94) |

| Income ($1000) | |||||||

| 0–9 | 12.2 | 11.1 | 1.00 | 14.0 | 9.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 10–19 | 21.1 | 30.3 | 0.62 (0.27,1.42) | 16.0 | 23.3 | 0.54 (0.17,1.74) | 0.63 (0.32,1.22) |

| 20–29 | 24.4 | 21.0 | 1.09 (0.47,2.49) | 24.0 | 28.2 | 0.90 (0.29,2.75) | 1.02 (0.53,1.97) |

| 30–44 | 25.6 | 21.5 | 1.10 (0.48,2.55) | 24.0 | 19.3 | 1.80 (0.54,6.05) | 1.25 (0.63,2.46) |

| 45+ | 16.7 | 16.1 | 0.99 (0.39,2.52) | 22.0 | 19.8 | 1.78 (0.51,6.20) | 1.16 (0.56,2.43) |

| Married | 60.2 | 64.8 | 0.78 (0.48,1.27) | 64.9 | 62.3 | 1.99 (0.98,4.03) | 1.06 (0.71,1.57) |

| Perceived hearing | |||||||

| Excellent, Very Good, Good | 39.8 | 63.6 | 1.00 | 29.3 | 50.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Fair | 46.6 | 32.4 | 2.34 (1.49,3.68) | 48.3 | 41.9 | 2.22 (1.12,4.40) | 2.31 (1.58,3.36) |

| Poor | 13.6 | 4.1 | 5.67 (2.71,11.87)* | 22.4 | 8.1 | 9.68 (3.56,26.27)* | 6.16 (3.47,10.96)* |

| Self-perception of hearing loss | 86.0 | 67.3 | 3.21 (1.76,5.86) | 91.2 | 77.2 | 3.55 (1.31,9.58) | 3.39 (2.03,5.65) |

| Family/friends think have hearing loss | 62.0 | 43.9 | 2.26 (1.43,3.55) | 80.4 | 50.2 | 6.05 (2.83,12.94) | 3.01 (2.05, 4.42) |

| Family history of hearing loss | 63.2 | 49.9 | 1.85 (1.15,2.98) | 67.9 | 56.0 | 1.66 (0.86,3.21) | 1.80 (1.22,2.64) |

| Impaired Cognition | 14.6 | 15.0 | 0.90 (0.48,1.69) | 20.0 | 14.1 | 1.32 (0.61,2.90) | 1.06 (0.65,1.72) |

| Age (years) | 71.0 (10.0) | 70.4 (9.0) | 1.01 (0.99,1.04) | 74.9 (8.8) | 72.3 (8.4) | 1.03 (0.99,1.07) | 1.02 (0.996,1.04) |

| HHIEscore1 | 11.2 (9.3) | 6.0 (6.9) | 1.08 (1.06,1.11) | 11.9 (9.5) | 7.3 (6.9) | 1.09 (1.04,1.13) | 1.08 (1.06,1.11) |

| PTA0.5–4 kHz, better ear2 | 35.7 (8.4) | 31.7 (5.3) | 1.60 (1.36,1.87) | 39.3 (6.1) | 36.2 (6.9) | 1.33 (1.07,1.67) | 1.51 (1.33,1.72) |

| PTA0.5–2 kHz, better ear2 | 27.9 (9.8) | 23.8 (7.0) | 1.44 (1.26,1.66) | 32.7 (7.7) | 27.8 (8.6) | 1.33 (1.10,1.60) | 1.41 (1.26,1.57) |

| PTA4–8 kHz, better ear2 | 63.2 (13.3) | 59.1 (14.2) | 1.11 (1.02,1.21) | 63.4 (11.6) | 64.8 (14.2) | 0.96 (0.84,1.09) | 1.06 (0.99,1.14) |

| Word recognitionquiet | 81.2 (15.2) | 87.4 (9.5) | 0.96 (0.94,0.98) | 82.4 (12.6) | 83.0 (13.5) | 1.00 (0.98,1.02) | 0.97 (0.96,0.99) |

| Word recognitionnoise | 34.0 (19.0) | 42.6 (18.8) | 0.97 (0.96,0.99) | 35.0 (17.7) | 39.0 (18.0) | 0.99 (0.97,1.01) | 0.98 (0.97,0.99) |

Test for trend P < 0.01

HHIE = Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly – Screening

PTA = Pure-tone Threshold Average at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in the better ear; hazard ratio for +5 dB (decibel) difference in PTA.

Significant factors in the best fitting multivariate model (with age and sex) included education (college graduate vs. all others), self-perception of hearing quality, perceived degree of handicap related to hearing (HHIE score) and the PTA of the 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz thresholds in the better ear (Table 2). There was no difference in the factors included in the best fitting model for the 2 follow-up periods. College graduates were 2.5 times (95% C.I.=1.5,4.1) as likely to acquire an aid as those without a college degree and subjects who considered their hearing to be poor also had a hazard ratio of 2.5 (95% C.I.=1.3,5.0) compared to subjects who perceived their hearing to be good or better. The rate of hearing aid acquisition also continued to have a significant, positive association with the HHIE score (+1 difference: HR=1.05, 95% C.I.=1.03,1.08) and the PTA0.5–4, better (+5 dB difference: HR=1.4, 95% C.I.=1.2,1.6).

Table 2. Risk Factors for Incidence of Hearing Aid Acquisition By Years of Follow-up.

Multivariate Model, Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)

| Years of Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | 0–5 | 5–10 | Periods Combined |

| Age | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 1.04 (0.99,1.08) | 1.01 (0.99,1.04) |

| Sex (male) | 0.99 (0.61,1.60) | 0.36 (0.18,0.74) | 0.73 (0.49,1.08) |

| Education – College Graduate | 2.16 (1.15,4.08) | 3.31 (1.30,8.39) | 2.45 (1.46,4.11) |

| Perceived hearing | |||

| Excellent, Very Good, Good | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Fair | 1.58 (0.95,2.61) | 1.74 (0.84,3.62) | 1.63 (1.08,2.47) |

| Poor | 2.07 (0.83,5.15)+ | 4.34 (1.34,14.04)+ | 2.50 (1.25,5.03)* |

| HHIE Score1 | 1.05 (1.02,1.09) | 1.05 (1.01,1.10) | 1.05 (1.03,1.08) |

| PTA0.5–4 kHz, better ear2 | 1.43 (1.20,1.70) | 1.21 (0.94,1.55) | 1.36 (1.18,1.56) |

Test for trend P ≤0.05

Test for trend P < 0.01

HHIE = Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly – Screening

PTA = Pure-tone Threshold Average at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in the better ear;hazard ratio for +5 dB difference in PTA.

Among subjects reporting having been told that they would benefit from a hearing aid who were followed for 10 years, prominent reasons given for not acquiring an aid included not needing it, the cost, the inconvenience of wearing an aid, and the poor experience of others (Table 3). The frequency of the cited reasons varied by gender and by the number of years since the hearing loss was detected. The most frequent responses cited as being the main reason for not obtaining an aid were cost (overall-27%; females-34%; males-23%) and not needing an aid (overall-26%; females-27%; males-25%).

Table 3. Reasons for Not Acquiring a Hearing Aid By Years of Follow-up and Gender*.

Percentage of Participants Reporting Each Reason+

| 5 year follow-up | 10 year follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason | Male (n=58) | Female (n=32) | Male (n=29) | Female (n=10) |

| Did not need it | 59.3 | 52.9 | 51.7 | 60.0 |

| Cost | 49.2 | 55.6 | 55.2 | 70.0 |

| Calls attention to handicap | 6.8 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Inconvenient to wear | 37.3 | 50.0 | 85.7 | 40.0 |

| Would not know where to buy | 17.6 | 13.8 | 17.2 | 0.0 |

| Poor experience of others | 31.0 | 45.5 | 55.2 | 60.0 |

| Too old to benefit | 5.2 | 15.6 | 7.1 | 0.0 |

Participants whose PTA0.5–4kHz, better ear (Pure-tone Threshold Average at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in the better ear) was determined to be > 25 dB(decibels) HL(Hearing Level) at EHLS1.

Includes only participants who reported having been told that they would benefit from a hearing aid.

DISCUSSION

This study found that close to two-thirds of the individuals with a hearing loss who were followed for 10 years did not acquire a hearing aid. This is in spite of the fact that hearing and perceived hearing handicap worsened over this period (Mean PTA0.5–4 kHz, better ear: baseline = 31.3; follow-up = 40.3, p < 0.0001; Mean word recognitioncompeting message: baseline = 42.5%, follow-up = 30.5%, p < 0.0001; Mean HHIE: baseline = 5.7, follow-up = 9.9, p < 0.001) and that subjects were participants in a study focused on hearing. The 5-year incidence of hearing aid acquisition was 14% and the 10-year incidence was 36%. These rates are compatible with previously reported prevalence rates of hearing aid use. In the baseline EHLS cohort we found that among individuals with a hearing loss (PTA0.5–4kHz, worse ear > 25 dB), 20.7% had a history of using a hearing aid, although only 14.6% were current users.13 In a slightly older study population of the Framingham cohort (age range 63 to 95 years in 1983–1985), 25% of the subjects who had reported a hearing problem, stated that they had used an aid at some time.33 Among a group of subjects 85 years of age in 1997–99, from the Netherlands, with a PTA1–4 kHz, better ear greater than 35 dB HL, 23% agreed to a first-time hearing aid fitting within the next year.34

Factors found to be significantly and independently related to first time use of a hearing aid included education (college graduate), hearing loss severity (measured as the PTA0.5–4kHz, better ear), hearing handicap score, and self-perception of hearing quality. These factors were the same for both acquisition within the first 5 years and within 5 to 10 years after detection. Since education and income are correlated and given the high cost of digital hearing aids, it is likely that income may be accounting for some of the observed education effect in our study. In previous clinical and survey work, self-perceived hearing quality has been found to be associated with hearing aid purchase.15,17 In a recent clinic-based investigation, a 10 point scale for self-rating of hearing ability was found to be a significantly strong predictor of hearing aid purchase (OR=0.47 for 1 unit improvement).17 However, no adjustment was made for other potential predictors. In the 2004 survey of National Family Opinion (NFO) members, close to 64% of first-time hearing aid owners stated that a self-perceived decline in hearing influenced the decision to acquire an aid.15

Our study focused on hearing aid acquisition after the identification of a hearing impairment in a population-based investigation of aging and sensory loss and not on the decision to seek help for a hearing problem. Studies have found that self-perceived hearing quality and the impact of hearing loss on daily life are influential factors in an individual’s decision to seek help for hearing difficulties.18–20 In a group of subjects, 55 years of age and older, with a PTA0.5–4 kHz, better ear of 30 dB HL or higher, there was a significant association between the rate of physician consultation and not only self-perception of hearing quality, but also whether the subject’s hearing was bothersome on a daily basis, if others had complained about the subject’s hearing, and whether others had advised the subject to obtain a hearing aid.19

In our study, when asked the reasons for not acquiring an aid, the most often cited responses included being unnecessary, the cost, the inconvenience and the poor experience of others. Similar reasons have been previously reported.21,22,33,34 In a 1998 survey of older NFO panel members (age 50 years and older), close to 70% of the hearing impaired respondents who were not using hearing aids stated that their hearing was not bad enough or that they could get along without one and 55% felt that hearing aids were too expensive.21 The strong impact of the negative experience of others has also previously been noted.22,34 Many aspects of using hearing aids can be difficult for older adults including changing the battery, cleaning the ear mold, and inserting the aid into the ear.35 Cognitive and functional ability, poor benefit, discomfort with background noise and in noisy situations, and poor fit have been found to be related to the use of hearing aids.36,37 All of these factors may enter into the consideration of the poor experience of others and the perception that hearing aids are inconvenient.

Improvements in recent years in the technology related to hearing assistive devices include the development of digital processing and directional microphones but it has not yet been determined that these improvements have or will lead to greater use of the devices.38 The optimum timing for the introduction of aid(s) in relation to age and the course of hearing decline also needs to be established.39,40 The high number of individuals dissatisfied with the performance of their hearing aids may be partially related to when the aid was first fitted and the approach used for adapting to the new device. If a hearing aid is fitted too early in the progression of hearing loss, a benefit substantial enough to offset the time, effort and cost involved in using the new hearing aid may not be seen. If the hearing aid is fitted too late, after the individual has already established compensatory mechanisms, additional difficulties involved in adapting to amplified sound may occur. In this study, we did not observe any difference in the significant predictors for the two time periods, i.e. 0 to 5 years vs. 5 to 10 years after hearing loss detection. In addition, results for the 0 to 5 years period showed that the rate of aid acquisition and the factors related to it did not significantly vary between subjects whose hearing loss was detected at baseline (which includes those who have long-standing hearing loss) and subjects with newly detected hearing loss, i.e. detected at the first follow-up. Therefore, there was no suggestion that time since hearing loss detection influenced the factors related to aid acquisition.

Our study was population-based in a relatively large population and was prospective in nature with 10 years of follow-up. Hearing capacity was measured using standard audiometric methods and details on hearing aid usage, demographic characteristics and perceived hearing ability were collected at 5-year follow-up intervals. We were able to evaluate whether the length of time since the hearing loss was detected influenced which factors predicted hearing aid acquisition. However, for the subjects whose hearing loss was identified at baseline, we did not have information regarding how long it had been since the hearing loss was first detected and we could not assess the question of the timing of aid fitting in more detail. Other limitations included having self-reported family history information only on parents and siblings and not on spouses. Hearing aid experience among spouses may very well influence the likelihood of acquiring an aid. Finally, the observed rates of hearing aid acquisition will vary by the level of loss we choose as our definition. It is possible that our definition of hearing loss (PTA0.5–4 kHz, better ear > 25 dB) is not optimum and may not be the level at which audiologists recommend an aid. It may be that information on hearing loss across frequency is important in the fitting of an aid, although in our work, individual frequency data were not significant predictors of hearing aid acquisition.

Widespread acceptance of rehabilitive aids, in particular hearing aids, for the treatment of hearing loss has not been achieved and remains a challenge. In addition to technologic advancements, work is needed to determine the most effective approaches for overcoming the personal and societal barriers affecting the acquisition and continued use of hearing aids.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R37AG011099 from the National Institute On Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors thank the residents of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin for their continued commitment to the study.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG11099 (to K.J. Cruickshanks) and EY06594 (to R. Klein and B.E.K. Klein).

Footnotes

Contributors

M. E. Fischer designed and completed the analyses, led the interpretation of the results, and led the writing. K. J. Cruickshanks conceived the study, was involved in the acquisition of subjects and data, provided advice on the analysis and interpretation of data and contributed to the writing. T. L. Wiley provided advice on the analysis and interpretation of data and contributed to the writing. B. E. K. Klein was involved in the acquisition of subjects and data, provided advice on the analyses and interpretation of results and contributed to the writing. R. Klein was involved in the acquisition of subjects and data, provided advice on the analyses and interpretation of results and contributed to the writing. T. S. Tweed provided advice on data collection and quality and contributed to the writing.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional Review Board approval by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin and informed consent were obtained.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BEK, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43:661–668. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carabellese C, Appollonio I, Rozzini R, et al. Sensory impairment and quality of life in a community elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuben DB, Mui S, Damesyn M, et al. The prognostic value of sensory impairment in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:930–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugh KC, Crandell CC. Hearing loss, hearing handicap, and functional health status between African American and Caucasian American seniors. J Am Acad Audiol. 2002;13:493–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallhagen MI, Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, et al. Comparative impact of hearing and vision impairment on subsequent functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1086–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chisolm TH, Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, Portz LJP, Abrams HB, Lesner S, McCarthy PA, Newman CW. A systematic review of health-related quality of life and hearing aids: final report of the American Academy of Audiology Task Force on the Health-Related Quality of Life Benefits of Amplification in Adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18:151–183. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.18.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulrow CD, Aguilar C, Endicott JE, Tuley MR, Velez R, Charlip WS, Rhodes MC, Hill JA, DeNino LA. Quality-of-life changes and hearing impairment. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:188–194. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-3-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulrow CD, Tuley MR, Aguilar C. Sustained benefits of hearing aids. Jour Speech Hear Res. 1992;35:1402–1405. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3506.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kricos PB, Erdman S, Bratt GW, Williams DW. Psychosocial correlates of hearing aid adjustment. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18:304–322. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.18.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stark L, Hickson P. Outcomes of hearing aid fitting for older people with hearing impairment and their significant others. Int J Audiol. 2004;43:390–398. doi: 10.1080/14992020400050050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yueh B, Souza PE, McDowell JA, Collins MP, Loovis CF, Hedrick SC, Ramsey SD, Deyo RA. Randomized trial of amplification strategies. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:1197–1204. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.10.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appollonio I, Carabellese C, Frattola L, Trabucchi M. Effects of sensory aids on the quality of life and mortality of elderly people: a multivariate analysis. Age Ageing. 1996;25:89–96. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popelka MM, Cruickshanks KC, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, Klein BEK, Klein R. Low prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults with hearing loss: The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1075–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak III: Higher hearing aid sales don’t signal better market penetration. Hear J. 1992;45:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VII: hearing loss population tops 31 million people. Hear Rev. 2005;12:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai M, Pratt LA, Lentzner H, Robinson KN. Trends in Vision and Hearing Among Older Americans. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; Aging Trends; No. 2. 2001 doi: 10.1037/e620682007-001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Palmer CV, Solodar HS, Hurley WR, Byrne DC, Williams KO. Self-perception of hearing ability as a strong predictor of hearing aid purchase. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20:341–347. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.20.6.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Brink RHS, Wit HP, Kempen GI, van Heuvelen MJ. Attitude and help-seeking for hearing impairment. Br J Audiol. 1996;30:313–324. doi: 10.3109/03005369609076779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duijvestijn JA, Anteunis LJ, Hoek CJ, Van Den Brink RH, Chenault MN, Manni JJ. Help-seeking behaviour of hearing-impaired persons aged > or = 55 years; effect of complaints, significant others and hearing aid image. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:846–850. doi: 10.1080/0001648031000719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahoney OCF, Stephens SDG, Cadge BA. Who prompts patients to consult about hearing loss? Br J Audiol. 1996;30:153–158. doi: 10.3109/03005369609079037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Council on Aging. The consequences of untreated hearing loss in older persons: summary report from the National Council of Aging. Head Neck Nurs. 2000;18:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak III: why 20 million in US don’t use hearing aids for their hearing loss. Hear J. 1993;46:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin: the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:879–886. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein R, Klein BEK, Linton KLP, et al. The Beaver Dam Eye Study: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1310–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein R, Klein BEK, Lee KP. Changes in visual acuity in a population: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Guidelines for manual pure-tone threshold audiometry. ASHA. 1978;20:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American National Standards Institute. Specifications for audiometers. New York: ANSI; 1989. p. S3.6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American National Standards Institute. Maximum permissible ambient noise levels for audiometric test rooms. New York: ANSI; 1992. p. S3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson RH, Zizz CA, Shanks JE, et al. Normative data in quiet, broadband noise, and competing message for Northwestern University auditory test no. 6 by a female speaker. J Speech Hear Disord. 1990;55:771–778. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5504.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiley TL, Cruickshanks KJ, Nondahl DM, et al. Aging and word recognition in competing message. J Am Acad Audiol. 1998;9:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. Identification of elderly people with hearing problems. ASHA. 1983;25:37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gates GA, Cooper JC, Kannel WB, Miller NJ. Hearing in the elderly: the Framingham cohort, 1983–1985. Part 1. Basic audiometric results. Ear Hear. 1990;11:247–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gussekloo J, de Bont LE, von Faber M, Eekhof JA, de Laat JA, Hulshof JH, van Dongen E, Westendorp RG. Auditory rehabilitation of older people from the general population – the Leiden 85-plus Study. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:536–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephens SD, Meredith R. Physical handling of hearing aids by the elderly. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1990;476:281–285. doi: 10.3109/00016489109127291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lupsakko TA, Kautiainen HJ, Sulkava R. The non-use of hearing aids in people aged 75 years and over in the city of Kuopio in Finland. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0789-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak V: “why my hearing aids are in the drawer”: the consumers’ perspective. Hear J. 2000;53:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards B. The future of hearing aid technology. Trends Amplif. 2007;11:31–45. doi: 10.1177/1084713806298004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pichora-Fuller MK, Singh G. Effects of age on auditory and cognitive processing: implications for hearing aid fitting and audiologic rehabilitation. Trends Amplif. 2006;10:29–59. doi: 10.1177/108471380601000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks DN. The time course of adaptation to hearing aid use. Br J Audiol. 1996;30:55–62. doi: 10.3109/03005369609077930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]