Abstract

Axon branching plays a critical role in establishing the accurate patterning of neuronal circuits in the brain. However, the mechanisms that control axon branching remain poorly understood. Here we report that knockdown of the brain-enriched signaling protein JIP3 triggers exuberant axon branching and self-contact in primary granule neurons of the rat cerebellar cortex. JIP3 knockdown in cerebellar slices and in postnatal rat pups in vivo leads to the formation of ectopic branches in granule neuron parallel fiber axons in the cerebellar cortex. We also find that JIP3 restriction of axon branching is mediated by the protein kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β). JIP3 knockdown induces the downregulation of GSK3β in neurons, and GSK3β knockdown phenocopies the effect of JIP3 knockdown on axon branching and self-contact. Finally, we establish doublecortin (DCX) as a novel substrate of GSK3β in the control of axon branching and self-contact. GSK3β phosphorylates DCX at the distinct site of Ser327 and thereby contributes to DCX function in the restriction of axon branching. Together, our data define a JIP3-regulated GSK3β/DCX signaling pathway that restricts axon branching in the mammalian brain. These findings may have important implications for our understanding of neuronal circuitry during development, as well as the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders of cognition.

Keywords: axon, connectivity, kinase, phosphorylation, cerebellum, granule cell

INTRODUCTION

The branching pattern of an axon defines the spatial distribution of its outputs, specifying the landscape for potential sites of connectivity with postsynaptic partners. Axon branching both establishes general targets of innervation and sculpts on a finer scale the field of innervation within a specific target. The restriction of axon branches to appropriate locales is critical for normal neuronal connectivity, and is accomplished by regulating the formation and patterning of branches. A key feature of axon branch patterning is self-avoidance, which represents the restriction in overlap of branches within the same neuron. The functional consequences of axon branch number and placement for neural circuits underscores the importance of elucidating the mechanisms that regulate axon branching in the brain.

Although the regulation of axon growth has been the subject of intense investigation, much less is known about the molecular control of axon branching. While a few molecules implicated in axon growth have been found to also modulate axon branching (Kornack and Giger, 2005), the signaling mechanisms that control axon branching in the mammalian brain remain largely to be elucidated. Further, the molecular control of self-avoidance of axon branches is poorly understood.

The JNK-interacting proteins (JIPs) comprise a family of signaling proteins first identified for their role in organizing JNK signaling cascades (Whitmarsh and Davis, 1998; Ito et al., 1999; Yasuda et al., 1999; Kelkar et al., 2000). Among the JIPs, JIP3 is selectively enriched in the brain (Kelkar et al., 2000; Akechi et al., 2001). The expression of JIP3 is high in axon bundles in the developing rodent brain (Akechi et al., 2001). Consistent with these observations, JIP3 appears to be enriched within the growth cone in neuronal processes (Verhey et al., 2001; Sato et al., 2004). The JIP3 orthologs in Drosophila and C. elegans, Sunday Driver and UNC-16, respectively, operate as adaptors for the motor protein kinesin and thereby regulate vesicular transport (Bowman et al., 2000; Byrd et al., 2001). In other studies, the protein kinase JNK has been implicated in the specification of axons in primary hippocampal neurons and in maintaining the integrity of cortical axon tracts in vivo (Chang et al., 2003; Oliva et al., 2006). Together, these studies raised the question of whether JIP3 might regulate axon development. Whether and how JIP3 plays a role in axon branching morphogenesis remained unknown.

In this study, we identify a cell-autonomous function for JIP3 in axon branching morphogenesis. Knockdown of JIP3 stimulates axon branching in primary granule neurons and in the rat cerebellar cortex in vivo. Remarkably, the ectopic axon branches in JIP3 knockdown neurons fail to avoid self-contact. Surprisingly, JIP3 inhibits axon branching and self-contact in a JNK-independent manner. Rather, we find that JIP3 regulates axon branching and self-contact via the protein kinase GSK3β. We also uncover the X-linked lissencephaly protein doublecortin (DCX) as a novel substrate of GSK3β. GSK3β induces the phosphorylation of DCX at Ser327, which contributes to DCX function in the inhibition of axon branching and self-contact. These findings define a novel JIP3-regulated GSK3β/DCX signaling pathway that restricts axon branching, thus providing important insights into our understanding of axon branch patterning in the mammalian brain. In addition, since DCX is implicated as an important cause of inherited mental retardation and epilepsy, our findings suggest that deregulation of the JIP3-controlled GSK3β/DCX signaling pathway and axon branching may contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders of cognition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

RNAi plasmids all encode short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) under control of the U6 RNA polymerase III promoter. The U6/JIP3i, U6/GSK3βi1, U6/GSK3βi2, U6/FAKi1, and U6/FAKi2 RNAi plasmids were generated by cloning the following oligonucleotides into a pBluescript vector containing the U6 promoter, with the underlined portion representing the target sequence:

U6/JIP3i: 5′-CACCGTGATGCTGTCAAATTATTCAAGCTTGAATTTGACAGCATCACGGTGCTTTTTTTG -3′ (This sequence is preceded by a G in the vector that is also part of the target sequence.)

U6/GSK3βi1: 5′-ACATTAAACCACAGAACCTCTTTCGTTAACTGAGGTTCTGTGGTTTAATGTCTTTTTG-3′

U6/GSK3βi2: 5′-ACTCAAGAACTGTCAAGTAACTTCGTTAACCTTACTTGACAGTTCTTGAGTCTTTTTG-3′

U6/FAKi1: 5′-GATCCAATGACAAGGTATATGTTCGTTAACGATATACCTTGTCATTGGATCCTTTTTG-3′

U6/FAKi2: 5′-GCCAACCTTAATAGAGAAGATTCGTTAACACTTCTCTATTAAGGTTGGCACTTTTTG-3′

The RNAi-resistant FLAG-JIP3-RES expression plasmid was generated using site-directed mutagenesis to introduce silent mutations in JIP3. Mutations of the RNAi target sequence are denoted by lower case letters: 5′-G CAt aga GAT GCT GTC AAA TTC T-3′.

The pmMKO.1/JIP3i and the pU6-puro/JIP3i RNAi plasmids are described (Bayarsaikhan et al., 2007; Hammond et al., 2008). The DCX RNAi plasmid (psiStrike/DCXi), targeting the 3′UTR sequence of DCX, and the corresponding control plasmid (psiStrike/Ctrl), containing 3 base pair mutations to the DCX hairpin sequence are described, as is the pCAG/DCX-IRES-GFP expression plasmid (Bai et al., 2003; Friocourt et al., 2007). FLAG-DCX/pCDNA3 and GST-DCX/pGEX plasmids have also been described (Gdalyahu et al., 2004).

Primary Granule Neurons

Cultures of cerebellar granule neurons were prepared from postnatal day 6 rats as described (Bilimoria and Bonni, 2008). For morphology experiments, neurons were transfected by the calcium phosphate method within one day of plating and fixed four days later. To diminish the possibility that any of the morphological phenotypes observed with our constructs of interest were due to effects of these constructs on neuronal survival, we included an expression plasmid for the anti-apoptotic protein gene Bcl-xL, which has been shown to have little or no effect on dendritic or axonal morphology in granule neurons (Gaudilliere et al., 2004; Konishi et al., 2004). For biochemistry experiments, neurons were electroporated prior to plating using the Amaxa nucleofection system and lysed four to six days later.

Immunocytochemistry

Granule neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.4% TritonX-100, and then immunostained using the rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen), mouse anti-GFP (NeuroMab), rabbit anti-DsRed (Clontech), mouse anti-Tuj1 (Covance), mouse anti-MAP2 (Sigma), rabbit anti-JIP3 (Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-DCX (Cell Signaling), or mouse anti-GSK3β (BD Biosciences) antibody. Nuclei were labeled with the DNA dye bisbenzimide (Hoechst 33258).

Morphological Analysis

Images were captured on an epifluorescence microscope and analyzed in a blinded manner using Spot Advanced software (Diagnostic Instruments). Axon tips were defined as terminal points of the primary axon and all of its branches. Self-contact points were defined as any instance where the primary axon or one of its branches appeared to touch or cross over either itself or any other portion of the axon. Confocal analyses established that points of self-contact observed in the 2D images used for measurements were also detected in single optical sections of 3D image series acquired in 0.4 micron step intervals on a 60x objective (data not shown). Primary axon length was measured by tracing the axonal fiber emanating from the soma in a manner that produced the longest continuous path.

Time Lapse Imaging

Granule neurons were plated on Lab-Tek II glass-bottom chambers (Thermo Scientific Nunc). Live imaging was performed using a Nikon Ti-E Perfect-Focus microscope equipped with a Perkin Elmer UltraVIEW spinning disk confocal system. An environment-controlled chamber maintained the neurons at 37°C, 5% CO2. Images were acquired and analyzed using Volocity software (Perkin Elmer). A 20x objective was used in combination with an automated stage to capture images every fifteen minutes for a period of one to two days, starting twenty-four hours post-transfection. Neurons were chosen randomly, and at the start of image acquisition the axon terminus was positioned at the center of the field.

Organotypic Cerebellar Slices

Organotypic cerebellar slices were prepared from postnatal day 10 rat pups as described (Gaudilliere et al., 2004). Briefly, a tissue chopper was used to cut 400 micron sagittal slices, which were maintained on a porous membrane (Millicell) that allows for an air-media interface. Slices were transfected using the Helios gene gun system (Biorad) at DIV4 and fixed at DIV8 in 4% paraformaldehyde and subjected to immunohistochemistry.

In Vivo Electroporation

Postnatal day three (P3) rat pups were electroporated as described (Konishi et al., 2004). Animals were sacrificed five days after electroporation. Cerebella were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, sunk in a 30% sucrose solution, and subsequently frozen in Tissue Tek OCT compound. Cryostat sections were cut coronally at 30 microns and immunostained with the GFP antibody. Layers of the cerebellar cortex were identified by staining nuclei with Hoechst.

Real Time Reverse Transcription PCR

RNA was extracted from granule neurons using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) for reverse transcription PCR was used to prepare cDNA from the extracted RNA. The reverse transcription reaction was conducted at 50°C for fifty minutes. Real time PCR was subsequently performed using the LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master kit (Roche). The PCR reaction consisted of an initial 95°C incubation for 10 minutes, followed by forty cycles of the following sequence: 95°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, then acquisition of melting curves and cooling. Primer sequences were as follows:

GAPDH: Forward 5′-TGCTGGTGCTGAGTATGTCG-3′ and Reverse 5′-GCATGTCAGATCCACAACGG-3′,

JIP3: Forward 5′-TGCCTTGGAACAAGAGAAGAAAG-3′ and Reverse 5′-CCACATAGGTCTGGATCATCTCC-3′, and

GSK3β: Forward 5′-CAAGCAGACACTCCCTGTGA-3′ and Reverse 5′-GTGGCTCCAAAGATCAGCTC-3′.

Immunoblotting

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells and neurons were both lysed in 50mM Tris pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1% TritonX-100. The protease inhibitors aprotinin, pepstatin, leupeptin, and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, the phosphatase inhibitors sodium fluoride, β-glycerolphosphate, sodium orthovanadate, and okadaic acid, as well as the reducing agent dithiothreitol were added to this buffer prior to cell lysis. Lysates were cleared of insoluble material by spinning at maximum speed on a tabletop centrifuge, boiled in sample buffer, and examined using standard SDS-PAGE followed by western-blotting. The antibodies used were rabbit anti-JIP3 (Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen), mouse anti-FLAG (Sigma), mouse anti-HSP60 (Santa Cruz), mouse anti-GSK3 (Assay Designs), rabbit polyclonal anti-DCX (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-14-3-3β (Santa Cruz), mouse anti-HA (Roche), rabbit anti-SnoN (Santa Cruz), and rabbit anti-JNK1 (Santa Cruz). The rabbit anti-phospho DCX Thr321, Ser327 antibody has been described (Gdalyahu et al., 2004). The following pharmacological agents were used: 6′bromoindirubin-3′-oxime, also known as BIO (Calbiochem), MG132 (Sigma), and SP600125 (Sigma).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

Kinase assays examining the phosphorylation of bacterially produced GST-DCX by GSK3β (New England Biolabs) were performed sequentially. The GST-DCX substrates, bound to glutathione sepharose beads, were first primed in a kinase reaction with FLAG-JNK1 purified from 293T cells, then washed with high salt to remove the JNK, and finally subject to a GSK3β kinse assay using [32P]-γ-ATP. The JNK reaction was carried out under the following conditions: 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2, 1mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 100 mM β-glycerolphosphate, and 10 mM non-radiolabeled ATP, for three hours at 30°C. The GSK3β reaction was carried out under the following conditions: 20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithithreitol, 200 μM non-radiolabeled ATP, and 10 μCi [32P]-γ-ATP, for 30 minutes at 30°C. Approximately 500 ng of substrate was incubated with 250 U of the GSK3β kinase.

The FLAG-JNK1 purified from 293T cells was activated by UV irradiation thirty minutes prior to lysis. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using agarose beads conjugated to the FLAG antibody (Sigma), washed in high salt, and eluted with 3xFLAG peptide (Sigma).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Statview and Excel software. Error bars on bar graphs denote standard error of the mean. The t-test was used to evaluate significance of comparisons in experiments with only two groups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed followed by Fisher’s post-hoc least significant difference (PLSD) test for pairwise comparisons in experiments with more than two groups. Except where indicated otherwise, asterisks on bar graphs denote statistical significance in comparisons with the control condition. One asterisk (*) signifies p<0.05, two asterisks (**) signify p<0.01, and three asterisks (***) signify p<0.001.

RESULTS

JIP3 restricts axon branching in cerebellar granule neurons

To investigate the role of the signaling protein JIP3 in axon morphogenesis, we characterized JIP3 function in granule neurons of the cerebellar cortex. Granule neurons represent a robust model system for elucidation of the molecular underpinnings of neuronal morphogenesis (Altman and Bayer, 1997; Hatten, 1999). Granule neuron precursors differentiate into postmitotic neurons within the external granule layer (EGL). Newly generated granule neurons extend axons which continue to grow as the granule neuron somas descend into the internal granule layer (IGL). Granule neuron axons form characteristic T-shaped structures, composed of an ascending axon and two major parallel fiber branches that run in the molecular layer (ML) along the coronal plane of the cerebellar cortex, where they participate in en passant synapses with Purkinje neuron dendrites (Ramon y Cajal, 1995; Altman and Bayer, 1997). Typically, parallel fiber axons give rise to at most one more branch in the ML (Ramon y Cajal, 1995). The morphological characteristics of granule neuron axons make these neurons ideal for unraveling the mechanisms that restrict axon branching.

To determine JIP3 function in neuronal morphogenesis, we used a plasmid-based method of RNA interference (RNAi) to acutely knockdown JIP3 (Gaudilliere et al., 2002). Expression of short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting JIP3 (U6/JIP3i) substantially reduced the levels of both exogenous JIP3 in heterologous cells and endogenous JIP3 in granule neurons (Figure 1A). We transfected granule neurons with the U6/JIP3i RNAi or control U6 plasmid together with a GFP expression plasmid, the latter to visualize granule neuron morphology. Axons and dendrites of granule neurons are easily identified based on their characteristic morphological features and expression of axon- or dendrite-specific markers (Gaudilliere et al., 2004; Konishi et al., 2004). Control primary granule neurons transfected with the control U6 plasmid harbored characteristic morphological features of granule neurons in the cerebellar cortex, including multiple short, branched dendrites and long axons bearing few or no branches (Figure 1B). Strikingly, we found that JIP3 knockdown triggered exuberant branching of axons in granule neurons (Figure 1B). Axons in JIP3 knockdown granule neurons had excessive branches, which were often in the distal portions of the axon (Figure 1B). The JIP3 knockdown-induced branching in the distal axon correlated with the spatial pattern of JIP3 expression in granule neurons. Both exogenous GFP-JIP3 and endogenous JIP3 were enriched in the distal portion of the axon in granule neurons (Figure S1A–B). Remarkably, axon branches in JIP3 knockdown neurons also failed to avoid self-contact as compared to axon branches in control granule neurons (Figure 1B). Quantification revealed an approximately three-fold increase in the number of axonal tips in JIP3 knockdown granule neurons as compared to control U6-transfected neurons (Figure 1C). In addition, JIP3 knockdown increased by five-fold the number of axon self-contact events in granule neurons (Figure 1C). In other analyses, we found that JIP3 knockdown led to reduction in axon length (Figure S2A), suggesting the JIP3 RNAi-induced phenotype of increased axon branching is not due to a general increase in axon growth. We also found that JIP3 RNAi had little or no effect on dendrite length in granule neurons (Figure S2B). Collectively, our data suggest that JIP3 knockdown stimulates axon branching and self-contact in neurons.

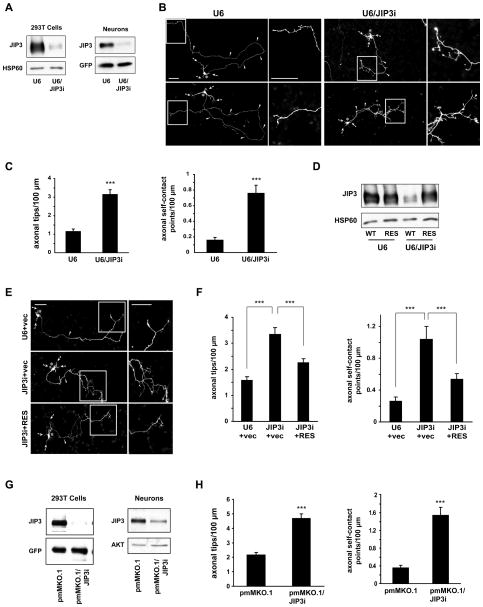

Figure 1. JIP3 restricts axon branching in cerebellar granule neurons.

(A) Left: Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the FLAG-JIP3 expression plasmid and the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted with the FLAG and HSP60 antibodies, the latter serving as a loading control. Right: Lysates of granule neurons nucleofected with the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid together with a GFP expression plasmid were immunoblotted using the JIP3 and GFP antibodies, the latter serving as a control for loading and transfection efficiency.

(B) Granule neurons transfected with the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid were fixed four days after transfection and subjected to immunocytochemistry using the GFP antibody. For each representative image, boxed regions in the left panel highlight the distal axon, which is shown at higher magnification in the right panel. In all images of this type, arrows indicate dendrites, asterisks the soma, and arrowheads the axon. Scale bars are 50 microns. JIP3 knockdown triggered the formation of exuberant axon branches.

(C) Quantification of axon branching of granule neurons treated as in (B). JIP3 knockdown significantly increased the number of axonal tips per hundred microns (t-test, p<0.001) and the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns (t-test, p<0.001). A total of 160 neurons were measured. Error bars here and in all subsequent bar graphs denote +SEM. Except where indicated otherwise, asterisks on bar graphs denote statistical significance in comparisons with the control condition. One asterisk (*) signifies p<0.05, two asterisks (**) signify p<0.01, and three asterisks (***) signify p<0.001.

(D) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with FLAG-JIP3 encoded by wild type cDNA (WT) or an RNAi-resistant cDNA (RES) and the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted using the FLAG and HSP60 antibodies. JIP3 knockdown decreased levels of FLAG-JIP3 but not FLAG-JIP3-RES.

(E) Granule neurons transfected with the FLAG-JIP3-RES or control vector expression plasmid and the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in (B). Scale bars are 50 microns.

(F) Quantification of axon branching of granule neurons treated as in (E). In the vector background, JIP3 knockdown significantly increased the number of axonal tips per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.001) and the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.001). In the background of JIP3 knockdown, expression of FLAG-JIP3-RES, as compared to the corresponding vector, significantly decreased the number of axonal tips per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.001) and the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.001). A total of 225 neurons were measured.

(G) Left: Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the FLAG-JIP3 expression plasmid and the pmMKO.1/JIP3i or control pmMKO.1 RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted using the FLAG and GFP antibodies. Right: Lysates of granule neurons nucleofected with the pmMKO.1/JIP3i or control pmMKO.1 RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted using the JIP3 and AKT antibodies, the latter serving as a loading control.

(H) Quantification of axon branching of granule neurons transfected with the pmMKO.1/JIP3i or control pmMKO.1 RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid, analyzed as in (B). Knockdown of JIP3 with this second hairpin increased the number of axonal tips per hundred microns (t-test, p<0.001) and the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns (t-test, p<0.001). A total of 156 neurons were measured.

To confirm that the JIP3 RNAi-induced axon branching and self-contact phenotype is due to specific knockdown of JIP3 rather than off-target effects of JIP3 shRNAs or non-specific activity of the RNAi machinery, we performed a rescue experiment. We designed an expression plasmid encoding an RNAi-resistant rescue form of the JIP3 (JIP3-RES). JIP3 RNAi induced knockdown of FLAG-JIP3 encoded by wild type cDNA (WT) but failed to effectively induce knockdown of FLAG-JIP3-RES in cells (Figure 1D). In morphology assays, expression of FLAG-JIP3-RES reversed the JIP3 RNAi-induced phenotypes of axon branching and self-contact (Figure 1E–F). These results suggest that the JIP3 RNAi-induced axon branching phenotype is the result of specific knockdown of JIP3 in granule neurons. Further corroborating these data, knockdown of JIP3 by two additional shRNAs targeting distinct regions of JIP3 robustly induced axon branching and increased axon self-contact, thus mimicking the effect of shRNAs encoded by the U6/JIP3 RNAi plasmid (Figures 1G–H, and S3A–C). Collectively, our data suggest that JIP3 plays a specific and essential role in the suppression of axon branching and may promote axon self-avoidance.

JIP3 suppresses axon branching in the cerebellar cortex in vivo

Having established that endogenous JIP3 inhibits axon branching in primary granule neurons, we next determined the cell autonomous function of JIP3 in the context of the intact cerebellar cortex. We first assessed the effect of JIP3 knockdown in organotypic cerebellar slices (Figure 2A). Using a biolistics approach, we transfected cerebellar slices from postnatal day 9 (P9) rat pups with the U6/JIP3i RNAi or control U6 plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid. After four days, cerebellar slices were subjected to immunohistochemistry using the GFP antibody. Granule neurons in the internal granule layer (IGL) were analyzed. Granule neurons in cerebellar slices transfected with the control U6 plasmid harbored normal axons that lacked branch points beyond the initial bifurcation of the parallel fibers (Figure 2B). By contrast, granule neuron axons in JIP3 knockdown slices displayed ectopic axon branches (Figure 2B). Quantification of these results revealed an approximately four-fold increase in the percent of granule neuron axons bearing ectopic branches in JIP3 knockdown cerebellar slices as compared to control U6-transfected slices (Figure 2C). These results suggest that JIP3 suppresses axon branching in the cerebellar cortex.

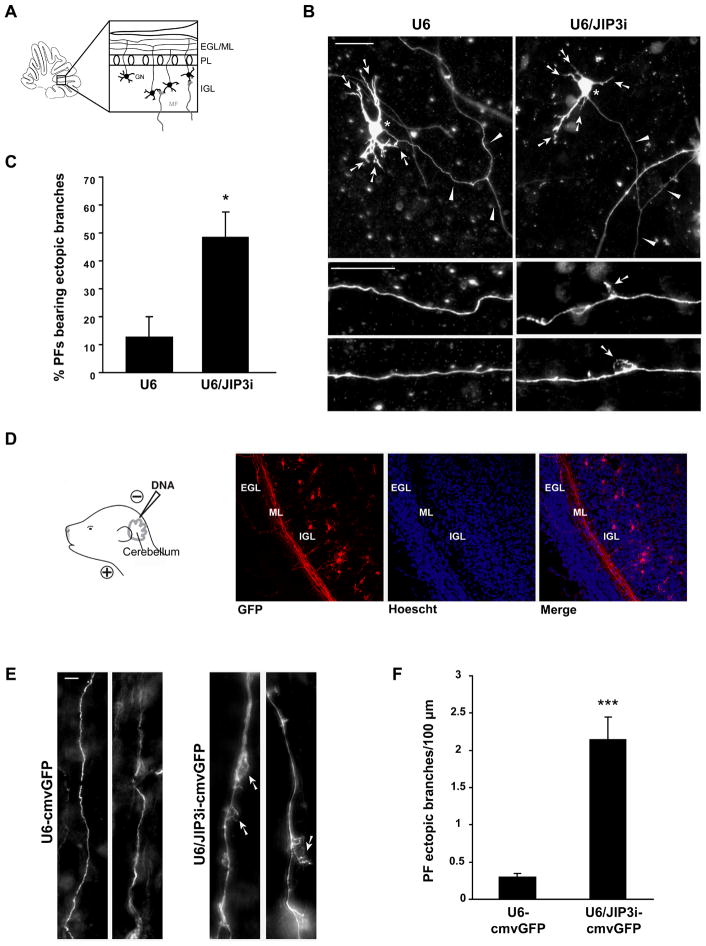

Figure 2. JIP3 suppresses branching in the cerebellar cortex in vivo.

(A) Schematic of cerebellar slice depicting organization of the cerebellar cortex, including the external granule layer/molecular layer (EGL/ML), the Purkinje cell layer (PL), and the internal granule layer (IGL).

(B) P9 rat cerebellar slices were transfected at DIV4 with the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid, fixed four days later at DIV8 and subjected to immunohistochemistry using the GFP antibody. Top panels show examples of transfected granule neurons in each condition. Arrows indicate dendrites, asterisks the soma, and arrowheads the parallel fiber axon. Lower panels show high magnification images of distal axons in each condition. Arrows in lower panels point to ectopic branches observed upon JIP3 knockdown. Scale bars are 25 microns.

(C) Quantification of slices treated as in (B). JIP3 knockdown significantly increased the percent of parallel fibers bearing one or more ectopic branches (t-test, p<0.05, n=3).

(D) Left: Schematic of in vivo electroporation paradigm. Briefly, P3 rat pups were injected with DNA at the outer layer of the cerebellum and electroporated. Five days after electroporation, pups were sacrificed and coronal cerebellar sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry using the GFP antibody. Right: Panels show a control section, with the EGL, ML, and IGL identified by Hoechst staining of nuclei. Overlay of GFP staining and Hoechst reveals that the majority of electroporated neurons reside in the IGL and extend axonal processes through the ML.

(E) High magnification views of individual GFP-positive parallel fibers in the ML of U6-cmvGFP- or U6/JIP3i-cmvGFP-electroporated cerebella. Arrows indicate ectopic branches from the primary axonal fiber. Scale bar is 5 microns.

(F) Quantification of parallel fiber ectopic branches in the cerebellar cortex in control and JIP3 knockdown animals. The number of ectopic branches in parallel fibers was significantly increased in JIP3 knockdown animals as compared to control animals (t-test, p<0.001). Measurements were collected from a total of 11 animals.

We next determined the role of JIP3 in axon morphogenesis in the rat cerebellum in vivo. Using an in vivo electroporation method (Figure 2D) (Konishi et al., 2004), we introduced a U6/JIP3i RNAi plasmid that also encodes GFP (U6/JIP3i-cmvGFP) or the corresponding control plasmid (U6-cmvGFP) into P3 rat pups. Animals were sacrificed five days after electroporation, at P8. Cerebellar sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry using the GFP antibody and also labeled with the DNA dye bisbenzimide (Hoechst 33258). A clear delineation of the external granule layer (EGL), molecular layer (ML), and internal granule layer (IGL) was observed in the cerebellar sections (Figure 2D). GFP-positive granule neuron somata were found in the IGL and possessed the characteristic T-shaped parallel fiber axons in the ML (Figure 2D). Examination of the GFP-positive axons in the ML revealed that JIP3 knockdown triggered the formation of ectopic branches in parallel fibers (Figure 2E). Although the majority of parallel fiber axons in control animals had few protrusions as they coursed through the ML, parallel fiber axons in JIP3 knockdown animals displayed frequent ectopic branches (Figure 2E). Quantification of these results revealed an approximately seven-fold increase of the number of ectopic parallel fiber branches in JIP3 knockdown animals compared to control animals (Figure 2F). These results demonstrate that JIP3 acts cell-autonomously to suppress axon branching in the mammalian brain in vivo.

GSK3β mediates JIP3 restriction of axon branching

The identification of a function for JIP3 in the control of axon branching morphogenesis led us to ask how JIP3 suppresses the formation of axon branches. The JIP3-associated protein kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) have reported roles in axon growth (Ito et al., 1999; Kelkar et al., 2000; Takino et al., 2002; Chang et al., 2003; Rico et al., 2004; Oliva et al., 2006). Surprisingly, we found that knockdown of JNKs or FAK failed to induce axon branching in granule neurons (Figures 3A–F). These data suggest that JIP3 suppresses axon branching independently of JNKs and FAK.

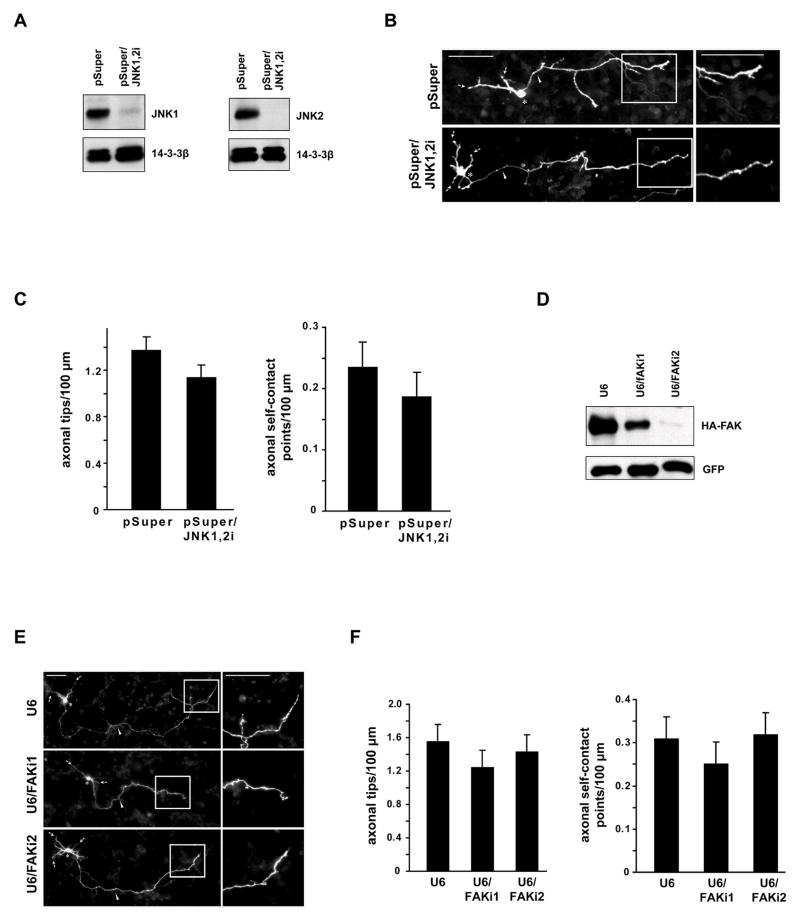

Figure 3. JNK knockdown or FAK knockdown do not appear to induce axon branching or self-contact.

(A) Left: Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the FLAG-JNK1 expression plasmid and the pSuper/JNK1,2i or control pSuper RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted using the FLAG and 14-3-3β antibodies. Right: Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the FLAG-JNK2 expression plasmid and the pSuper/JNK1,2i or control pSuper RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted using the FLAG and 14-3-3β antibodies.

(B) Granule neurons transfected with the pSuper/JNK1,2i or control pSuper RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Scale bars are 50 microns.

(C) Quantification of axon branching of granule neurons treated as in (B). JNK knockdown did not significantly alter either the number of axonal tips or the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns. A total of 149 neurons were measured.

(D) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the HA-FAK expression plasmid and the U6/FAKi1, U6/FAKi2, or control U6 RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted using the HA and GFP antibodies.

(E) Granule neurons transfected with the U6/FAKi1, U6/FAKi2, or control U6 plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Scale bars are 50 microns.

(F) Quantification of axon branching of granule neurons treated as in (E). FAK knockdown with either hairpin did not significantly alter the number of axonal tips or the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns. A total of 232 neurons were measured.

The protein kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) has been implicated in the control of axon branching in mammalian neurons (Kim et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2009). We therefore asked whether GSK3β might mediate the ability of JIP3 to inhibit axon branching. We first characterized the expression pattern of GSK3β in primary granule neurons. Both GFP-GSK3β and endogenous GSK3β were expressed throughout the cytoplasm, including the axon (Figure S1C–D). Consistent with a role for GSK3β in JIP3 control of axon branching, we found that GSK3β protein levels were diminished in granule neurons upon JIP3 knockdown (Figure 4A). Interestingly, JIP3 knockdown had little or no effect on the abundance of GSK3α (Figure 4A), suggesting that JIP3 specifically controls the abundance of GSK3β in neurons.

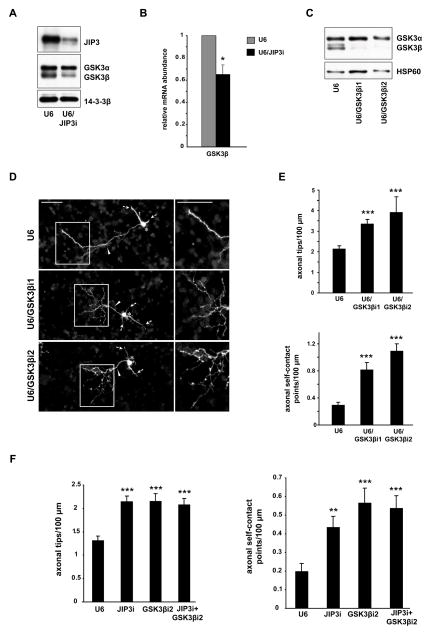

Figure 4. GSK3β mediates JIP3 restriction of axon branching.

(A) Lysates of granule neurons nucleofected with the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted with the JIP3 and GSK3 antibodies. 14-3-3β served as the loading control. Knockdown of JIP3 reduced the levels of GSK3β but not GSK3α in neurons.

(B) RT-PCR was performed to quantify the relative mRNA abundance of GSK3β in granule neurons nucleofected with the U6/JIP3i or control U6 RNAi plasmid. Relative mRNA abundance was calculated for the U6/JIP3i condition relative to the U6 condition, normalized by GAPDH. Knockdown of JIP3 significantly decreased the relative levels of GSK3β mRNA (t-test, p<0.05).

(C) Lysates of granule neurons nucleofected with the U6/GSK3βi1, U6/GSK3βi2, or control U6 RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted with the GSK3 and HSP60 antibodies. GSK3β RNAi induced knockdown of GSK3β but not GSK3α in neurons.

(D) Granule neurons transfected with the U6/GSK3βi1, U6/GSK3βi2, or control U6 RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Scale bars are 50 microns. GSK3β knockdown triggered the formation of exuberant axon branches.

(E) Quantification of axon branching of granule neurons treated as in (D). For either hairpin, the number of axonal tips and the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns were both significantly increased in GSK3β knockdown neurons as compared to control U6-transfected neurons (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.001 for all). A total of 257 neurons were measured.

(F) Granule neurons transfected with the U6/JIP3i, U6/GSK3βi2, or both RNAi plasmids, or the control U6 RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Knockdown of either JIP3 or GSK3β alone significantly increased the number of axonal tips and the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.01 or p<0.001 as specified by asterisks). Knockdown of JIP3 and GSK3β together did not increase the number of axonal tips or self-contact points as compared to knockdown of JIP3 or GSK3β alone. A total of 273 neurons were measured.

We next investigated the mechanism by which JIP3 controls the abundance of GSK3β in neurons. We first tested whether JIP3 knockdown induces the proteasome-dependent degradation of GSK3β in neurons. Incubation of granule neurons with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 failed to restore the levels of GSK3β in neurons upon JIP3 knockdown (Figure S4). These results suggest that JIP3 does not appear to stabilize GSK3β protein in neurons. We next assessed the role of JIP3 in the regulation of GSK3β gene expression. We found that JIP3 knockdown significantly reduced GSK3β mRNA levels in neurons, as monitored by real-time RT-PCR analyses (Figure 4B). Together, these results suggest that JIP3 stimulates GSK3β gene expression in neurons.

To characterize the role of GSK3β in JIP3 control of axon branching morphogenesis, we first assessed the effect of GSK3β knockdown on axon morphology of granule neurons. Expression of two shRNAs targeting distinct regions of GSK3β (U6/GSK3βi1 and U6/GSK3βi2) induced specific knockdown of endogenous GSK3β but not GSK3α in granule neurons (Figure 4C). In morphology assays, GSK3β knockdown induced exuberant axon branching in granule neurons (Figure 4D). GSK3β knockdown substantially increased both the number of axon branch tips and axon self-contact points in neurons (Figure 4E). These data suggest that GSK3β knockdown phenocopies the effect of JIP3 knockdown on axon branch morphogenesis.

To further compare the effect of inhibition of JIP3 or GSK3β on axon branching, we performed time lapse analyses of JIP3 knockdown and GSK3β knockdown neurons. Primary granule neurons transfected with the U6/JIP3i, U6/GSK3βi2, or control U6 plasmid were imaged at fifteen minute intervals for a two day period beginning twenty-four hours after transfection. The temporal analysis of axon morphogenesis allowed the assessment of the type of branching induced by JIP3 knockdown and GSK3β knockdown. Two modes of axon branching have been described (Acebes and Ferrus, 2000). In the first mode, the primary growth cone splits into two smaller growth cones, which then grow apart. In the second mode, a branch emerges from the neurite shaft after the primary growth cone has grown past the branch site. The latter mode of branching has been coined “backbranching” (Harris et al., 1987). We observed that the majority of axon branches in primary granule neurons were generated via backbranching (Figure S5A–B). Importantly, we found little or no difference in the percent of branches formed by backbranching in JIP3 knockdown, GSK3β knockdown, or control U6-transfected neurons (Figure S5A–B). These data further corroborate the conclusion that GSK3β knockdown phenocopies the effect of JIP3 knockdown on axon branching.

We next tested whether concurrent inhibition of JIP3 and GSK3β in granule neurons produces an additive effect on axon branching. We found that simultaneous knockdown of JIP3 and GSK3β did not lead to an additive effect on axon branching. Accordingly, the number of axon branch tips and self-contact points in neurons in which both JIP3 and GSK3β were knocked down were indistinguishable from those in JIP3 or GSK3β knockdown (Figure 4F). These data support a model whereby JIP3 and GSK3β may act in a shared pathway to regulate axon branching and self-contact.

DCX is a novel substrate of GSK3β in neurons

We next determined the mechanism by which GSK3β regulates axon branching and self-contact in neurons. Since GSK3β is a protein kinase, we sought to identify the substrate of GSK3β that mediates its ability to suppress axon branching and self-contact. We reasoned that a physiologically-relevant substrate of GSK3β should harbor conserved putative sites of GSK3 phosphorylation and should be intimately linked to the regulation of microtubule dynamics and the control of branching. The neuronal microtubule-associated protein Doublecortin (DCX) fulfills both criteria. DCX is enriched in the growth cone and suppresses neurite branching (Gdalyahu et al., 2004; Schaar et al., 2004; Kappeler et al., 2006; Friocourt et al., 2007). Consistent with these observations, endogenous DCX was enriched in the distal portion of the axon as compared to proximal portion of the axon in granule neurons (Figure S1E). In addition, DCX has a conserved putative site of GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser327 (Figure 5B). We therefore asked whether GSK3β catalyzes the phosphorylation of DCX and thereby regulates axon branching morphogenesis.

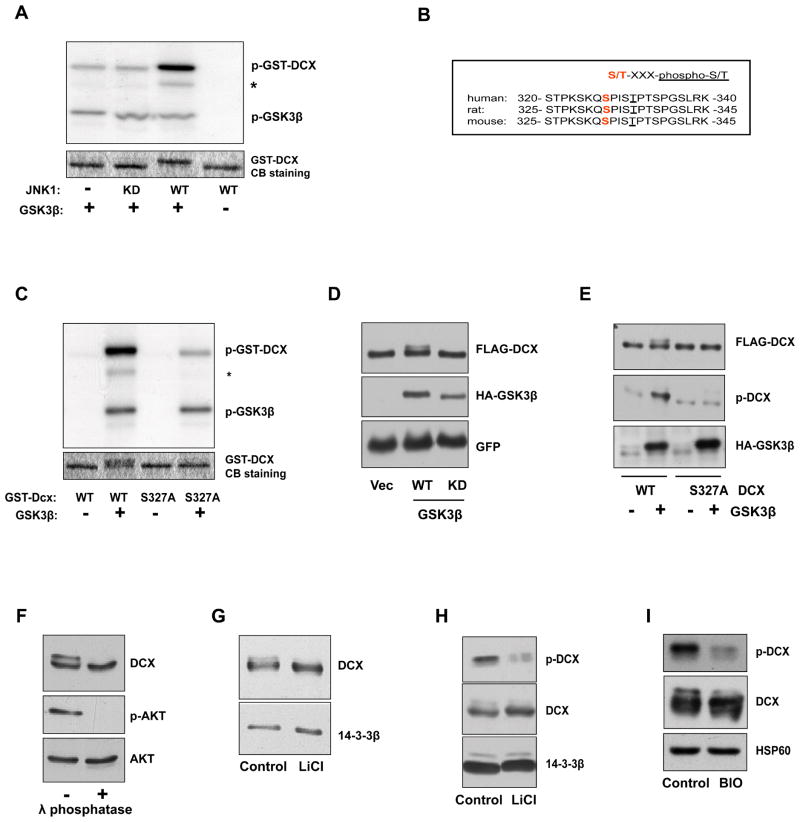

Figure 5. GSK3β phosphorylates DCX at Ser327.

(A) Sequential in vitro kinase assay. Bacterially purified GST-DCX bound to glutathione beads was first primed with wild-type (WT) or kinase dead (KD) FLAG-JNK1 purified from 293T cells. Following high salt washes to remove JNK, GST-DCX was subjected to a kinase assay with GSK3β and radiolabeled ATP. The top panel shows 32P incorporation and the bottom panel shows Coommassie blue staining. Asterisk denotes a likely degradation product of GST-DCX. GSK3β robustly phosphorylates DCX in vitro.

(B) Alignment of human, rat, and mouse DCX protein sequences in the vicinity of a candidate GSK3 phosphorylation site corresponding to human DCX Ser327.

(C) In vitro GSK3β kinase assay for JNK-primed WT or S327A GST-DCX, performed as in (A). The top panel shows 32P incorporation and the bottom panel shows Coommassie blue staining. Asterisk denotes a likely degradation product of GST-DCX.

(D) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the WT HA-GSK3β, KD HA-GSK3β, or control vector and FLAG-DCX expression plasmids together with the GFP expression plasmid were immunoblotted using the FLAG, HA, and GFP antibodies.

(E) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the WT HA-GSK3β or control vector and the WT FLAG-DCX or S327A FLAG-DCX expression plasmids were immunoblotted using the p-DCX, FLAG, and HA antibodies. GSK3β induces the phosphorylation of DCX at Ser327 in cells.

(F) Granule neuron lysates treated with or without lambda phosphatase were immunoblotted using the DCX, phospho-AKT, and AKT antibodies, the last two serving as controls for the phosphatase treatment and loading respectively.

(G) Lysates of granule neurons treated for 24 hours with 2 mM NaCl (Control) or 2 mM LiCl were immunoblotted using the DCX and 14-3-3β antibodies.

(H) Lysates of granule neurons treated for 56 hours with 2 mM NaCl (Control) or 2 mM LiCl were immunoblotted using the p-DCX and 14-3-3β antibodies. Endogenous DCX is phosphorylated at Ser327 in a GSK3β-dependent manner in neurons.

(I) Lysates of granule neurons treated for 16 hours with 200 nM BIO (6-bromoindirubin-3-oxime), a selective inhibitor of GSK3, or the vehicle control DMSO were immunoblotted using the p-DCX, DCX, and HSP60 antibodies. Endogenous DCX is phosphorylated at Ser327 in a GSK3β-dependent manner in neurons.

To assess the ability of GSK3 to phosphorylate DCX, we performed an in vitro kinase assay using purified recombinant GSK3β, recombinant DCX protein, and radiolabeled [32P]-γ-ATP, the latter to detect the phosphorylation of DCX. Because GSK3β phosphorylates substrates that are primed by another phosphorylation event, we determined the ability of GSK3β to phosphorylate DCX that was already subjected to a priming in vitro kinase reaction. Because the protein kinase JNK phosphorylates and regulates DCX (Gdalyahu et al., 2004), and because JNK can serve as the priming kinase for other GSK3β substrates (Sharfi and Eldar-Finkelman, 2008; Morel et al., 2009), we used JNK as the priming kinase in our assays. Recombinant DCX was subjected to an in vitro kinase assay using immunoprecipitated JNK1 and non-radiolabeled ATP prior to the in vitro kinase assay with recombinant GSK3β. We found that GSK3β robustly phosphorylated DCX primed with JNK (Figure 5A). Importantly, GSK3β failed to induce the phosphorylation of DCX primed with kinase-inactive JNK1 (Figure 5A). Because the priming reaction was carried out with non-radiolabeled ATP and JNK1 was washed away from the substrate under high salt conditions, all 32P incorporation observed on the autoradiogram is derived from the GSK3β reaction. Consistent with this interpretation, DCX primed with JNK1 did not show 32P incorporation in the absence of GSK3β (Figure 5A). In addition, immunoblotting analyses of samples after high salt washes confirmed the successful deletion of JNK1 (Figure S6). Together, these results demonstrate that GSK3β phosphorylates DCX in vitro and that DCX represents a novel primed substrate of GSK3β.

Remarkably, the putative GSK3β site of phosphorylation, Ser327, in DCX lies four amino acids N-terminal to Ser331, which is an established site of JNK-induced phosphorylation (Figure 5B) (Gdalyahu et al., 2004). In the in vitro kinase assays, we found that mutation of Ser327 in recombinant DCX reduced substantially the ability of recombinant GSK3β to phosphorylate DCX primed with JNK (Figure 5C). These results reveal that Ser327 represents a major site of GSK3β-induced phosphorylation of DCX in vitro.

We next measured the ability of GSK3β to phosphorylate DCX in cells. We found that expression of GSK3β induced the phosphorylation of coexpressed DCX in 293T cells, as monitored by a mobility shift in DCX (Figure 5D). Expression of a kinase-inactive mutant of GSK3β, in which the ATP binding site Lys85 is replaced with Ala, failed to induce the phosphorylation of DCX in cells (Figure 5D). Importantly, GSK3β failed to induce the phosphorylation of the DCX S327A mutant protein in cells, as reflected by the absence of the mobility shift of DCX S327A upon coexpression with GSK3β (Figure 5E). We also used a phospho-DCX antibody, which was raised to recognize DCX that is phosphorylated at Ser327 or Thr321, to independently assess the ability of GSK3β to phosphorylate DCX in cells. Immunoblotting analyses using phospho-DCX antibody revealed that GSK3β induced the phosphorylation of wild type DCX but not the DCX S327A mutant protein in 293T cells (Figure 5E). Thus, the GSK3β-induced phosphorylation signal is Ser327-dependent. Together, these results show that GSK3β phosphorylates DCX at Ser327 in cells. In addition, these results show that the phospho-DCX antibody recognizes Ser327-phosphorylated DCX.

We next determined the importance of endogenous GSK3β in mediating the phosphorylation of DCX at Ser327 in neurons. First, immunoblotting analyses of lysates of granule neurons using the DCX antibody revealed that endogenous DCX is phosphorylated in granule neurons, as reflected by a mobility shift that is sensitive to treatment of lysates with λ-phosphatase (Figure 5F). Incubation of granule neurons with the GSK3 inhibitor lithium chloride (LiCl) dramatically reduced the phosphorylation of DCX in neurons, as observed by immunoblotting with the DCX antibody (Figure 5G). Using the phospho-DCX antibody, we found that inhibition of GSK3 by LiCl also robustly reduced the phosphorylation of DCX at Ser327 (Figure 5H). Likewise, incubation of granule neurons with the selective GSK3 inhibitor BIO (6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime) dramatically reduced the phosphorylation of DCX in neurons, as determined by immunoblotting with the DCX antibody or phospho-DCX antibody (Figure 5I). These results suggest that endogenous GSK3β induces the phosphorylation of DCX at Ser327 in neurons. Collectively, our experiments in vitro, in heterologous cells, and in neurons demonstrate that DCX is a novel bona fide substrate of GSK3β.

GSK3β/DCX Signaling Restricts Axon Branching

Having established DCX as a substrate of GSK3β, we next ascertained the role of the GSK3β/DCX signaling link in the control of axon branch morphogenesis in neurons. We first tested the effect of DCX knockdown on axon branch morphology in granule neurons. Expression of DCX shRNAs (psiStrike/DCXi) reduced the levels of endogenous DCX in granule neurons (Figure 6A). In morphology assays, we found that DCX knockdown triggered excessive branching of axons as compared to neurons transfected with the control psiStrike/Ctrl RNAi plasmid (Figure 6B). Quantification revealed that DCX knockdown led to a greater than two-fold increase in both the number of axon tips and self-contact points in neurons (Figure 6C). These results suggest that DCX knockdown phenocopies the effect of JIP3 knockdown and GSK3β knockdown on axon branch morphology in neurons. Thus, DCX may operate in a shared pathway with JIP3 and GSK3β to suppress axon branching and self-contact in neurons. In agreement with this conclusion, simultaneous knockdown of DCX with JIP3 knockdown or GSK3β knockdown did not have an additive effect on axon branching (Figure 6D–E). In addition, overexpression of DCX suppressed the JIP3 knockdown- and GSK3β knockdown-induced axon branching and self-contact phenotypes (Figure S7A–D). Together, these data suggest that DCX operates downstream of GSK3β in the control of axon branching morphogenesis.

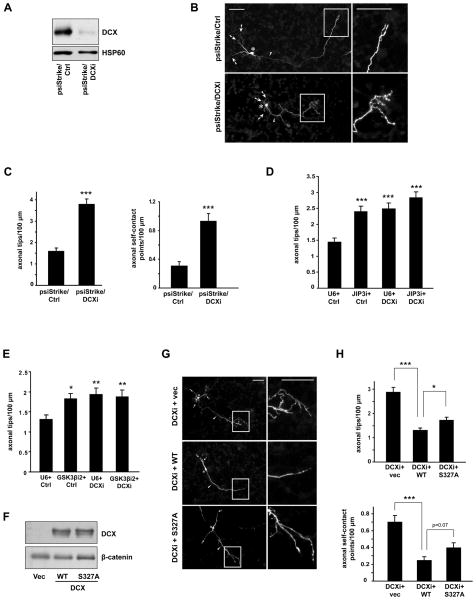

Figure 6. GSK3β/DCX signaling restricts axon branching.

(A) Lysates of granule neurons nucleofected with the psiStrike/DCXi or psiStrike/Ctrl RNAi plasmid were immunoblotted using the DCX and HSP60 antibodies.

(B) Granule neurons transfected with the psiStrike/DCXi or psiStrike/Ctrl RNAi plasmid together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Scale bars are 50 microns. DCX knockdown triggered the formation of exuberant axon branches.

(C) Quantification of axon branching of neurons treated as in (B). The number of axonal tips and the number of axonal self-contact points per hundred microns were both significantly increased upon DCX knockdown (t-test, p<0.001 for both). A total of 166 neurons were measured.

(D) Granule neurons transfected with the JIP3 RNAi, DCX RNAi, or both RNAi plasmids, or the control RNAi plasmids together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Knockdown of either JIP3 or DCX alone significantly increased the number of axonal tips per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.001 for both). Knockdown of JIP3 and DCX together did not significantly increase axon branching as compared to knockdown of JIP3 or DCX alone. A total of 292 neurons were measured.

(E) Granule neurons transfected with the GSK3β RNAi, DCX RNAi, or both RNAi plasmids, or the control RNAi plasmids together with the GFP expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Knockdown of either GSK3β or DCX alone significantly increased the number of axonal tips per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.05 or p<0.01 as specified by asterisks). Knockdown of GSK3β and DCX together did not increase axon branching as compared to knockdown of GSK3β or DCX alone. A total of 264 neurons were measured.

(F) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the WT DCX-IRES-GFP, S327A DCX-IRES-GFP, or control vector expression plasmid were immunoblotted using the DCX and β-catenin antibodies, the latter serving as a loading control.

(G) Granule neurons transfected with the psiStrike/DCXi plasmid together with the WT DCX-IRES-GFP, S327A DCX-IRES-GFP, or control vector expression plasmid were analyzed as in Figure 1B. Scale bars are 50 microns.

(H) Quantification of axon branching of neurons treated as in (G). In the background of DCX knockdown, expression of either WT or S327A DCX-IRES-GFP as compared to vector significantly reduced the number of axonal tips and self-contact points per hundred microns (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.001 for all). Expression of S327A DCX-IRES-GFP did not reduce axonal tips or self-contacts points as effectively as WT DCX-IRES-GFP in the background of DCX RNAi (ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD test, p<0.05 for axonal tips and p=0.07 for axonal self-contact points). A total of 340 neurons were measured.

We next determined if the GSK3β-induced phosphorylation of DCX at Ser327 regulates axon branching and self-contact. Because the DCX shRNAs target the 3′untranslated region of DCX, we used DCX encoded by wild type cDNA to rescue the DCX RNAi-induced phenotype (Bai et al., 2003; Friocourt et al., 2007). Expression of WT DCX-IRES-GFP significantly diminished the DCX RNAi-induced increase in axon tips and self-contact points (Figure 6G–H). These results suggest that the DCX RNAi-induced axon branching and self-contact phenotype is the result of specific knockdown of DCX in neurons, and provided us with the means to test the role of phosphorylation of DCX at Ser327 in the ability of DCX to inhibit axon branching and self-contact. We found that S327A DCX-IRES-GFP was not as effective as WT DCX-IRES-GFP in reducing the number of axon tips and self-contact points in granule neurons in the background of DCX RNAi (Figure 6G-H). In control experiments, we confirmed that S327A DCX-IRES-GFP and WT DCX-IRES-GFP are expressed at similar levels (Figure 6F). These results suggest that DCX phosphorylation by GSK3β at Ser327 contributes to the control of axon branching and self-contact. Collectively, our study shows that a GSK3β/DCX signaling link regulated by JIP3 controls axon branch morphogenesis in mammalian brain neurons.

DISCUSSION

We have uncovered a novel signaling pathway that cell-autonomously controls axon branching morphogenesis in the mammalian brain. There are several major findings in this study. (1) The neuron-enriched signaling protein JIP3 inhibits axon branching and self-contact in granule neurons of the cerebellar cortex. (2) JIP3 restricts branching of granule neuron parallel fiber axons in the cerebellar cortex in cerebellar slices and in postnatal rat pups in vivo. (3) JIP3 regulates the expression of the protein kinase GSK3β in neurons, which in turn inhibits axon branching and axon self-contact. (4) GSK3β phosphorylates the microtubule-associated protein DCX at Ser327 in neurons, and thereby inhibits axon branching and self-contact. These findings define a JIP3 regulated GSK3β/DCX signaling pathway that restrains axon branching and may promote axon self-avoidance.

The identification of the JIP3 regulated GSK3β/DCX signaling pathway reveals that neurons harbor mechanisms that actively restrict axon branching. While mechanisms that restrict branches at existing axon terminal arbors or collateral branch sites are beginning to be characterized (Cohen-Cory and Fraser, 1995; Weimann et al., 1999; Livet et al., 2002; Bagri et al., 2003; Homma et al., 2003), mechanisms that actively repress branching in locations where axons are unbranched remained to be identified. Granule neuron axons branch infrequently. Although all granule neurons have a bifurcated parallel fiber axon, the bifurcation does not represent true branching, as it results from the coordinated fusion of two bipolar axons and the descent of the soma during neuronal migration. Thus, granule neurons provided us with an ideal model system for the study of cell-intrinsic mechanisms that actively suppress axon branching. It will be interesting in future studies to determine if components of the JIP3-regulated GSK3β/DCX signaling pathway might also restrict axon branching at terminal arbors or collateral sites.

In addition to enhancing our understanding of axon branching, our findings may provide insight into the molecular regulation of axon self-avoidance. Although the phenomenon of avoidance of axon self-contact has been recognized for some time (Kramer et al., 1985; Wolszon, 1995), the underlying mechanisms have remained to be identified. Our data revealing that JIP3, GSK3β, and DCX inhibit both axon self-contact and axon branching suggest that common mechanisms may have evolved to control these two aspects of axon morphogenesis. Consistent with this idea, the immunoglobin superfamily member DSCAM can regulate both axon bifurcation and the divergent segregation of axon branches in Drosophila (Wang et al., 2002). A potential explanation for the concurrence of axon self-contact and axon branching upon inhibition of the JIP3-regulated GSK3β/DCX pathway that cannot be ruled out is that axon self-contact may occur secondary to increased axon branching.

The finding that JIP3 controls axon branching and self-contact via GSK3β raises the important question of how JIP3 regulates GSK3β in neurons. JIP3 and GSK3β failed to form a physical complex in neurons (data not shown). Consistent with this observation, we have found that JIP3 does not appear to regulate the stability of GSK3β protein. Rather, JIP3 may control GSK3β transcription or mRNA stability. JNK is the only known interacting partner of JIP3 with a clear function in signaling to the nucleus (Johnson and Lapadat, 2002; Bogoyevitch and Kobe, 2006). However, inhibition of JNK failed to mimic JIP3 knockdown in reducing GSK3β levels in neurons (Figure S8). Therefore, it will be important in future studies to identify JIP3-dependent signals that regulate GSK3β transcription or mRNA stability.

The identification of DCX as a novel substrate of GSKβ is a key finding in our study. In our analyses, we used the protein kinase JNK as a priming kinase to identify Ser327 as a critical site of GSKβ-induced phosphorylation in DCX. Whether JNK, Cdk5, or a distinct proline-directed protein kinase is the relevant endogenous priming kinase in neurons remains to be determined. Interestingly, phosphorylation of DCX by Cdk5 inhibits the ability of DCX to promote microtubule bundling and suppress axon branching (Tanaka et al., 2004; Bielas et al., 2007). In view of our finding that GSKβ-induced phosphorylation of DCX promotes the function of DCX in the regulation of axon branching and self-contact, these observations raise the possibility that GSK3β-induced phosphorylation might counteract the effects of Cdk5 on DCX function.

Although we focused on Ser327 as a key site of GSK3β-induced phosphorylation in DCX, additional sites of phosphorylation in DCX likely play a role in the GSK3β/DCX signaling link. Mutation of Ser327 reduced substantially but did not abolish the ability of GSK3β to catalyze the phosphorylation of DCX in vitro. In addition, mutation of Ser327 impaired but did not block the ability of DCX to suppress axon branching and self-contact in neurons. It will be important in future studies to identify the additional sites of GSK3β-induced phosphorylation in DCX.

Elucidation of the GSK3β/DCX signaling link in our study points to new biological roles for both GSK3β and DCX in the nervous system. Since GSK3β is thought to regulate neurogenesis (Kim et al., 2009; Mao et al., 2009), GSK3β-induced phosphorylation of DCX may contribute to the differentiated state of neurons. Conversely, in view of the established role of DCX in neuronal migration (Bai et al., 2003; Deuel et al., 2006; Friocourt et al., 2007), identification of the GSK3β/DCX signaling link raises the intriguing possibility that GSK3β may promote the migration of neurons in the developing mammalian brain.

DCX is the gene responsible for X-linked lissencephaly in humans, a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by mental retardation and epilepsy (Walsh, 1999). Abnormalities in neuronal migration play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of X-linked lissencephaly. The elucidation of the GSK3β/DCX signaling link in the control of axon branching and self-contact raises the important question of whether abnormalities of axon branching and self-contact are featured in the pathology of X-linked lissencephaly. In addition, our findings raise the prospect that deregulation of GSK3β may also contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders of cognition and epilepsy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Katsuji Yoshioka for the pmMKO.1/JIP3i plasmid, Kristen Verhey for the pU6-puro/JIP3i plasmid, Gaelle Friocourt for the psiStrike/DCXi and pCAG/DCX-IRES-GFP plasmids, Jonathon Kurie for the pSuper/JNK1,2i plasmid, and Joan Brugge for the HA-FAK plasmid. We thank Gabriel Corfas, Wade Harper, Bernardo Sabatini, and members of the Bonni laboratory for helpful discussions and critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants (NS041021 and NS047188) to A.B.

References

- Acebes A, Ferrus A. Cellular and molecular features of axon collaterals and dendrites. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:557–565. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akechi M, Ito M, Uemura K, Takamatsu N, Yamashita S, Uchiyama K, Yoshioka K, Shiba T. Expression of JNK cascade scaffold protein JSAP1 in the mouse nervous system. Neurosci Res. 2001;39:391–400. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer S. Development of the Cerebellar System: In Relation to its Evolution, Structure, and Functions. New York: CRC-Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bagri A, Cheng HJ, Yaron A, Pleasure SJ, Tessier-Lavigne M. Stereotyped pruning of long hippocampal axon branches triggered by retraction inducers of the semaphorin family. Cell. 2003;113:285–299. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Ramos RL, Ackman JB, Thomas AM, Lee RV, LoTurco JJ. RNAi reveals doublecortin is required for radial migration in rat neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1277–1283. doi: 10.1038/nn1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayarsaikhan M, Takino T, Gantulga D, Sato H, Ito T, Yoshioka K. Regulation of N-cadherin-based cell-cell interaction by JSAP1 scaffold in PC12h cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielas SL, Serneo FF, Chechlacz M, Deerinck TJ, Perkins GA, Allen PB, Ellisman MH, Gleeson JG. Spinophilin facilitates dephosphorylation of doublecortin by PP1 to mediate microtubule bundling at the axonal wrist. Cell. 2007;129:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria PM, Bonni A. Cultures of Cerebellar Granule Neurons. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2008;3:1201–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Bogoyevitch MA, Kobe B. Uses for JNK: the many and varied substrates of the c-Jun N-terminal kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:1061–1095. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00025-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman AB, Kamal A, Ritchings BW, Philp AV, McGrail M, Gindhart JG, Goldstein LS. Kinesin-dependent axonal transport is mediated by the sunday driver (SYD) protein. Cell. 2000;103:583–594. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd DT, Kawasaki M, Walcoff M, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Jin Y. UNC-16, a JNK-signaling scaffold protein, regulates vesicle transport in C. elegans. Neuron. 2001;32:787–800. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Jones Y, Ellisman MH, Goldstein LS, Karin M. JNK1 is required for maintenance of neuronal microtubules and controls phosphorylation of microtubule-associated proteins. Dev Cell. 2003;4:521–533. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cory S, Fraser SE. Effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on optic axon branching and remodelling in vivo. Nature. 1995;378:192–196. doi: 10.1038/378192a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuel TA, Liu JS, Corbo JC, Yoo SY, Rorke-Adams LB, Walsh CA. Genetic interactions between doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase in neuronal migration and axon outgrowth. Neuron. 2006;49:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friocourt G, Liu JS, Antypa M, Rakic S, Walsh CA, Parnavelas JG. Both doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase play a role in cortical interneuron migration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3875–3883. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4530-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudilliere B, Shi Y, Bonni A. RNA interference reveals a requirement for myocyte enhancer factor 2A in activity-dependent neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46442–46446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudilliere B, Konishi Y, de la Iglesia N, Yao G, Bonni A. A CaMKII-NeuroD signaling pathway specifies dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2004;41:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gdalyahu A, Ghosh I, Levy T, Sapir T, Sapoznik S, Fishler Y, Azoulai D, Reiner O. DCX, a new mediator of the JNK pathway. Embo J. 2004;23:823–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond JW, Griffin K, Jih GT, Stuckey J, Verhey KJ. Co-operative versus independent transport of different cargoes by Kinesin-1. Traffic. 2008;9:725–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris WA, Holt CE, Bonhoeffer F. Retinal axons with and without their somata, growing to and arborizing in the tectum of Xenopus embryos: a time-lapse video study of single fibres in vivo. Development. 1987;101:123–133. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatten ME. Central nervous system neuronal migration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:511–539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma N, Takei Y, Tanaka Y, Nakata T, Terada S, Kikkawa M, Noda Y, Hirokawa N. Kinesin superfamily protein 2A (KIF2A) functions in suppression of collateral branch extension. Cell. 2003;114:229–239. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Yoshioka K, Akechi M, Yamashita S, Takamatsu N, Sugiyama K, Hibi M, Nakabeppu Y, Shiba T, Yamamoto KI. JSAP1, a novel jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK)-binding protein that functions as a Scaffold factor in the JNK signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7539–7548. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappeler C, Saillour Y, Baudoin JP, Tuy FP, Alvarez C, Houbron C, Gaspar P, Hamard G, Chelly J, Metin C, Francis F. Branching and nucleokinesis defects in migrating interneurons derived from doublecortin knockout mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1387–1400. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelkar N, Gupta S, Dickens M, Davis RJ. Interaction of a mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling module with the neuronal protein JIP3. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1030–1043. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.1030-1043.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Wang X, Wu Y, Doble BW, Patel S, Woodgett JR, Snider WD. GSK-3 is a master regulator of neural progenitor homeostasis. Nat Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nn.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Zhou FQ, Zhou J, Yokota Y, Wang YM, Yoshimura T, Kaibuchi K, Woodgett JR, Anton ES, Snider WD. Essential roles for GSK-3s and GSK-3-primed substrates in neurotrophin-induced and hippocampal axon growth. Neuron. 2006;52:981–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi Y, Stegmuller J, Matsuda T, Bonni S, Bonni A. Cdh1-APC controls axonal growth and patterning in the mammalian brain. Science. 2004;303:1026–1030. doi: 10.1126/science.1093712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack DR, Giger RJ. Probing microtubule +TIPs: regulation of axon branching. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer AP, Goldman JR, Stent GS. Developmental arborization of sensory neurons in the leech Haementeria ghilianii. I. Origin of natural variations in the branching pattern. J Neurosci. 1985;5:759–767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00759.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livet J, Sigrist M, Stroebel S, De Paola V, Price SR, Henderson CE, Jessell TM, Arber S. ETS gene Pea3 controls the central position and terminal arborization of specific motor neuron pools. Neuron. 2002;35:877–892. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Ge X, Frank CL, Madison JM, Koehler AN, Doud MK, Tassa C, Berry EM, Soda T, Singh KK, Biechele T, Petryshen TL, Moon RT, Haggarty SJ, Tsai LH. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;136:1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel C, Carlson SM, White FM, Davis RJ. Mcl-1 integrates the opposing actions of signaling pathways that mediate survival and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3845–3852. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00279-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva AA, Jr, Atkins CM, Copenagle L, Banker GA. Activated c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for axon formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9462–9470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2625-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon y Cajal S. The cerebellum. In: Swanson N, Swanson L, translators. Histology of the nervous system. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rico B, Beggs HE, Schahin-Reed D, Kimes N, Schmidt A, Reichardt LF. Control of axonal branching and synapse formation by focal adhesion kinase. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1059–1069. doi: 10.1038/nn1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Ito M, Ito T, Yoshioka K. Scaffold protein JSAP1 is transported to growth cones of neurites independent of JNK signaling pathways in PC12h cells. Gene. 2004;329:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar BT, Kinoshita K, McConnell SK. Doublecortin microtubule affinity is regulated by a balance of kinase and phosphatase activity at the leading edge of migrating neurons. Neuron. 2004;41:203–213. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00843-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharfi H, Eldar-Finkelman H. Sequential phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-2 by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase plays a role in hepatic insulin signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E307–315. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00534.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takino T, Yoshioka K, Miyamori H, Yamada KM, Sato H. A scaffold protein in the c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway is associated with focal adhesion kinase and tyrosine-phosphorylated. Oncogene. 2002;21:6488–6497. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Serneo FF, Tseng HC, Kulkarni AB, Tsai LH, Gleeson JG. Cdk5 phosphorylation of doublecortin ser297 regulates its effect on neuronal migration. Neuron. 2004;41:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhey KJ, Meyer D, Deehan R, Blenis J, Schnapp BJ, Rapoport TA, Margolis B. Cargo of kinesin identified as JIP scaffolding proteins and associated signaling molecules. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:959–970. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CA. Genetic malformations of the human cerebral cortex. Neuron. 1999;23:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80749-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zugates CT, Liang IH, Lee CH, Lee T. Drosophila Dscam is required for divergent segregation of sister branches and suppresses ectopic bifurcation of axons. Neuron. 2002;33:559–571. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann JM, Zhang YA, Levin ME, Devine WP, Brulet P, McConnell SK. Cortical neurons require Otx1 for the refinement of exuberant axonal projections to subcortical targets. Neuron. 1999;24:819–831. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ. Structural organization of MAP-kinase signaling modules by scaffold proteins in yeast and mammals. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:481–485. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolszon L. Cell-cell interactions define the innervation patterns of central leech neurons during development. J Neurobiol. 1995;27:335–352. doi: 10.1002/neu.480270307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda J, Whitmarsh AJ, Cavanagh J, Sharma M, Davis RJ. The JIP group of mitogen-activated protein kinase scaffold proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7245–7254. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Wang Z, Gu Y, Feil R, Hofmann F, Ma L. Regulate axon branching by the cyclic GMP pathway via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 in dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1350–1360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3770-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.