Abstract

Mutations in parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, are most common cause of autosomal-recessive Parkinson's disease (PD). Here, we show that the stress-signaling non-receptor tyrosine-kinase c-Abl links parkin to sporadic forms of PD via tyrosine phosphorylation. Under oxidative and dopaminergic stress, c-Abl was activated in cultured neuronal cells and in striatum of adult C57 mice. Activated c-Abl was found in the striatum of PD patients. Concomitantly, parkin was tyrosine-phosphorylated, causing loss ofit's ubiquitin ligase and cytoprotective activities, and the accumulation of parkin substrates, AIMP2 (p38/JTV-1) and FBP-1. STI-571, a selective c-Abl inhibitor, prevented tyrosine phosphorylation of parkin and restored its E3 ligase activity and cytoprotective function both in vitro and in vivo. Our results suggest that tyrosine phosphorylation of parkin by c-Abl is a major post-translational modification that leads to loss of parkin function and disease progression in sporadic PD. Moreover, inhibition of c-Abl offers new therapeutic opportunities for blocking PD progression.

Keywords: Kinase, Phosphorylation, Abl, Parkin, Dopamine, Parkinson's disease

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD), is a neurodegenerative movement disorder characterized pathologically by progressive loss of midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Olanow & Tatton, 1999) and protein inclusions designated Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites (Braak et al., 2003). Although more than 90% of PD cases occur sporadically and are thought to be due, in part, to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (Zhang et al., 2000), study of genetic mutations has provided great insight into molecular mechanisms of PD (Dawson & Dawson, 2003; Moore et al., 2005). Mutations in parkin, which encodes E3 ubiquitin ligase (Shimura et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2000), are among the most common causes of hereditary PD (Kitada et al., 1998). These mutations are thought to impair parkin activity through direct loss of function, diminished parkin solubility, or impaired degradation of substrates (Sriram et al., 2005; Matsuda et al. 2005). Numerous putative parkin substrates have been described, and failure of parkin to ubiquitinate some of these substrates may play important role in dopaminergic neurodegeneration (von Coelln et al., 2004). Particularly, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (ARS) interacting multifunctional protein type 2 (AIMP2) (p38/JTV-1) (Corti et al., 2003) and far upstream element-binding protein-1 (FBP-1) seem to be authentic parkin substrates, as they accumulate in parkin-deficient mice and in brain tissue of patients with hereditary PD (Ko et al., 2005, 2006). Furthermore, AIMP2 is selectively toxic to dopaminergic neurons (Ko et al., 2006). Other substrates may also play a role in PD (von Coelln, 2004; Moore et al., 2005). Oxidative, nitrative, nitrosative, and dopaminergic stress are thought to impair function of parkin through direct post-translational modification and/or alteration of parkin solubility (Chung et al., 2004; Yao et al., 2004; LaVoie et al., 2005, Wang et al., 2005). The molecular mechanisms underlying impairment of parkin function by these stressors are unknown. Nor is it clear whether these modifications play a role in common, sporadic forms of PD.

c-Abl is a tightly-regulated non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including growth, survival and stress response (Hantschel & Superti-Furga, 2004). c-Abl is structurally homologous to the Src family of kinases in its N-terminal region, with three distinct domains – SH3, SH2, and a tyrosine kinase catalytic domain (Smith & Mayer, 2002). c-Abl and its close relative, Abl-related gene (Arg) tyrosine kinase, have long unique C-terminal extensions that display numerous functionalities (Smith & Mayer, 2002). c-Abl shuttles between cytoplasm and nucleus and its subcellular localization determines its function in response to diverse types of stress (Van Etten, 1999). The cytoplasmic form of c-Abl is activated in cellular response to oxidative stress (Sun et al, 2000). Since oxidative stress is a prominent feature of sporadic PD (Jenner & Olanow, 1998), we investigated whether c-Abl could play pathogenic role in PD.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

Parkin, ubiquitin, AIMP-2, FBP-1, and c-Abl constructs have been previously described (Zhang et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2000; Chung et al., 2001; Yamamoto et al., 2005).

Cell culture

K562 human leukemic cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK cells were cultured in modified Eagle medium (MEM) containing 10% FBS, SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 100 μM 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine (MPP+) or dopamine (DA) for 24 h, or with 250 μM H2O2 for 1 h in serum-free medium. The c-Abl inhibitor STI-571 (Gleevec, imatinib mesylate; Novartis Pharma AG) was added to cells at 10 μM for 6 h prior to toxin-treatment. Cells were treated with 100 μM MnTBAP (Sigma) or 1 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC) 24 h prior to MPP+ treatment. Cells were also transfected with c-Abl siRNA or green florescent protein (GFP) siRNA 48 h prior to MPP+ treatment. All transfections were done with Lipofectamine PLUS or Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Enriched mouse primary striatal neurons were grown and differentiated as directed by the supplier (Cambrex, MD).

GST pull-down assay

GST pull-down assays were performed according to the manufacturer using glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences).

Co-immunoprecipitation

SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with 2 μg of various plasmids and co-immunoprecipitations were performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2000; Chung et al., 2001).

In vitro phosphorylation

GST-parkin (200 ng) was incubated with 100 ng kinase-active c-Abl, in standard in vitro kinase assays with or without STI-571 (Sun et al., 2000).

In vitro ubiquitination

GST-parkin was pre-incubated with kinase-active c-Abl for 30 min before initiating in vitro ubiquitination. Reactions were performed at 30°C in 20 μl mixture containing 50 mM TrisHCl, pH7.5, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 5 μg ubiquitin (Sigma), 100 ng E1 (Sigma), 400 ng UbcH7 (Sigma), and 200 ng GST-parkin. For ubiquitination of FBP-1, HEK cells were transfected with HA-FBP-1 plasmid (4 μg). Cells were collected after 48 h and RIPA lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA-agarose (Sigma) and washed. GST-parkin was pre-incubated with kinase-active c-Abl or kinase-dead (KD) c-Abl or with kinase-active c-Abl in the presence of STI-571 (2.5 μM) for 30 min before initiating in vitro ubiquitination. Reactions were performed at 30°C by adding a 20 μl mixture of the above in vitro ubiquitination mixture. After 2 h, the reactions were terminated with an equal volume of 1 × SDS sample buffer and the products analyzed by immunoblot with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies (Sigma).

Parkin knockdown

SH-SY5Y cells were infected with lenti-shRNA-parkin or lenti-shRNA-GFP 48 h prior to MPP+ treatment. Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer for biochemical analysis or stained for cell viability 24 h after MPP+ treatment. At 48 h, knockdown efficiency of parkin shRNA was ∼65%. STI-571 was added at 10 μM for 6 h prior to MPP+-treatment. To determine the toxic effects of this treatment, SH-SY5Y cells cultured in 6-well plates at 0.5 × 106 cells/well were infected as before, then 24 h later, treated with 100 μM MPP+ for 24 h. In some cases, 10 μM STI-571 was added to 6 h prior to MPP+-treatment. Cells were stained with Hoechst (Molecular Probes) and propidium iodide (PI; Sigma). Infection efficiencies were determined by counting number of GFP-positive cells amongst Hoechst-stained cells 48 h post-infection. Cell death was assayed by counting PI-positive (red) cells amongst GFP-positive (green) cells in four randomly chosen fields in each well. These experiments were repeated three times. Average ± standard error was plotted as % cell death.

Human tissue

Human brain tissue was obtained through the brain donation program of the Morris K. Udall Parkinson's Disease Research Center at JHMI in keeping with HIPAA regulations. This research proposal involves anonymous autopsy material and follows Federal Register 46.101 exemption number 4. Triton-X 100 (TX-100)-soluble and TX-100-insoluble fractions were collected, analyzed by immunoblot and densitometric analyses of protein bands using an Alpha Imager 2000 (Alpha Inotech, Wohlen, Switzerland). Relative levels of phospho-parkin (ratio of phospho-parkin to IP parkin), AIMP2 (ratio of AIMP2 to actin), and phospho-c-Abl (ratio of phospho-c-Abl to c-Abl, after each was normalized to actin) were expressed as mean ± standard error. The degree of association between phospho-parkin and AIMP2 or phospho-c-Abl was calculated by comparing the normalized values using the correlation (CORREL) function in Excel.

Oxyblot analysis

Cell lysate (50 μg) from post-mortem samples of striatum or cortex of PD patients or age-matched controls were derivatized with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) as per manufacturer's protocol (OxyBlot, Millipore, USA).

Neurotoxin injections in mice

All animal procedures were approved by and conformed to guidelines of Institutional Animal Care Committee (NCTR, AR). Adult male C57BL mice (n=5 per group) were pre-treated for one week with daily 10 mg/kg STI-571 or vehicle alone (25% DMSO/PBS) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. On day seven animals received four injections i.p. of the neurotoxin, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP-HCl; 20 mg/kg free base; Research Biochemicals) in saline or saline alone at 2 h intervals. Daily STI-571 injections continued up to one more week after the last injection of MPTP. Animals were processed and prepared for biochemical and neurochemical assessment as previously described (Przedborski et al., 1996; Thomas et al., 2007).

Results

Parkin is tyrosine-phosphorylated by c-Abl, blocking its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity

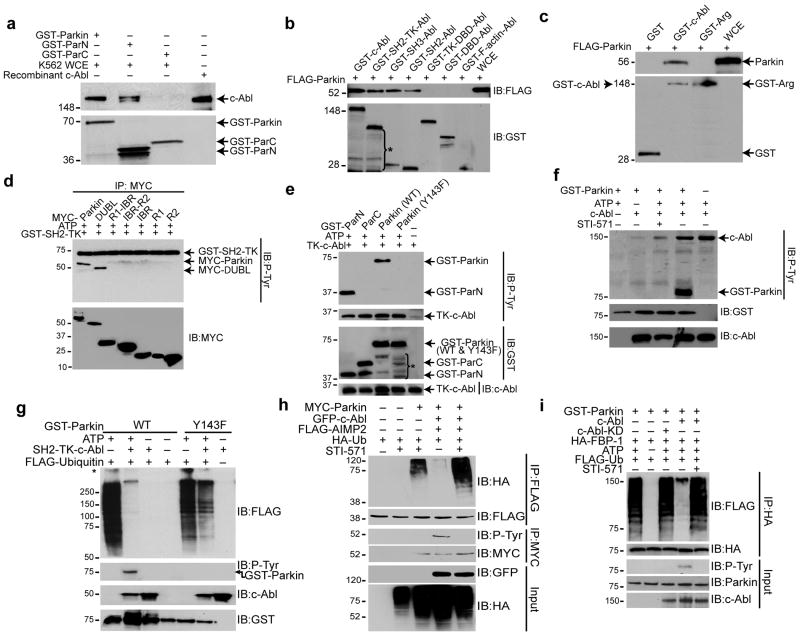

GST-pull down of K562 cell lysates with GST-tagged full-length or truncated (N or C terminal) forms of parkin (Supplemental Fig. 1a) revealed that N-terminal domain of parkin interacts with c-Abl (Fig. 1a). Pull-down with GST-tagged proteins of full-length c-Abl, and SH3, SH2, SH2-TK (tyrosine kinase), TK-DNA binding (DBD), DBD, and F-actin domains of c-Abl (Supplemental Fig. 1b) and lysates expressing FLAG-parkin showed a strong interaction of parkin with full-length c-Abl, and modest interaction with its truncated SH3 and SH2 domains (Fig. 1b). Parkin-Abl interaction is specific, since FLAG-parkin failed to interact with c-Abl-related gene (Arg) tyrosine kinase (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

(a) GST pull-down assay using GST-Parkin and parkin-fragments, GST-ParN and GST-ParC (∼1 μg each) with K562 whole cell extracts (WCE) (5 mg). (b) GST pull-down assay using GST-c-Abl and c-Abl fragments (∼1 μg) as shown in (c) and WCE (5 mg) of SH-SY5Y cells transfected with FLAG-parkin. *denotes degradation products of GST-c-Abl. (c) GST pull-down assay using GST-Arg and GST-c-Abl (∼1 μg) and WCE (5 mg) of SH-SY5Y cells transfected with FLAG-parkin. (d) Immunoblots with anti-p-tyrosine (P-Tyr) and myc after an in vitro kinase assay using GST-SH2-TK (c-Abl) and myc immunoprecipitates from SH-SY5Y cells transfected with myc-tagged full-length and deletion mutants of parkin (2 μg). (e) Immunoblots with antibodies to P-Tyr, GST, c-Abl after an in vitro kinase assay using TK-c-Abl and GST-ParN, GST-ParC or GST-Parkin, wild-type or Y143F parkin. *denotes degradation products of GST-constructs. (f) Immunoblots with antibodies to P-Tyr, GST, c-Abl after an in vitro kinase assay using GST-Parkin with full-length human recombinant His-c-Abl (100 ng) with or without STI-571 (2.5 μM). (g) Immunoblots of in vitro auto-ubiquitination assays using SH2-TK-Abl (∼200 ng) and GST-Parkin (wild-type or Y143F). *non-specific ubiquitination. (h) Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitates with FLAG and myc antibodies of SH-SY5Y cell lysates transfected with FLAG-tagged AIMP2 (2 μg), myc-tagged WT parkin (1 μg), HA-tagged ubiquitin (1 μg) and GFP-tagged c-Abl-KA (1 μg), incubated with 10 μM STI-571 for 12 h. (i) Immunoblots of an in vitro GST-parkin ubiquitination assay of immunoprecipitated HA-FBP-1 with c-Abl or c-Abl KD (∼200 ng) with or without STI-571 (2.5 μM). All experiments were repeated at least three times. Representative examples are presented.

In vitro c-Abl kinase assay with myc-tagged constructs (Supplemental Fig. 1c) of parkin indicated that c-Abl tyrosine phosphorylates only full-length parkin and a construct lacking the ubiquitin-like domain (ΔUBL) (Fig. 1d), suggesting that Y143 is substrate for c-Abl. In vitro kinase reactions of GST-fusion proteins of wild-type parkin, Y143F mutant parkin, ParN and ParC with a 32 kDa active tyrosine kinase domain of c-Abl (TK-c-Abl) (Supplemental Fig. 1d) revealed increased tyrosine phosphorylation of wild-type parkin and ParN, but not of Y143F mutant parkin or ParC (Fig. 1e). STI-571, a selective c-Abl inhibitor, substantially reduced c-Abl-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of GST-parkin (Fig. 1f). Moreover, parkin phosphorylation was not observed in the absence of c-Abl (Fig. 1f). These results indicate that parkin specifically interacts with c-Abl and that parkin is phosphorylated by c-Abl at its N-terminal domain on Y143.

In vitro ubiquitination assays using recombinant GST-parkin (wild-type or Y143F) and SH2-TK-c-Abl revealed that c-Abl-mediated parkin phosphorylation substantially inhibited its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, as demonstrated by reduced parkin auto-ubiquitination (Fig. 1g). The phosphorylation-resistant Y143F mutant of parkin showed little effect on auto-ubiquitination (Fig. 1g). Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of AIMP2 was reduced in the presence of c-Abl, an effect that was blocked by STI-571 (Fig. 1h). Parallel results were obtained using an alternative parkin substrate FBP-1 (Fig. 1i). Thus, parkin-mediated E3 ubiquitin ligase activity is inhibited by c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation of parkin on Y143.

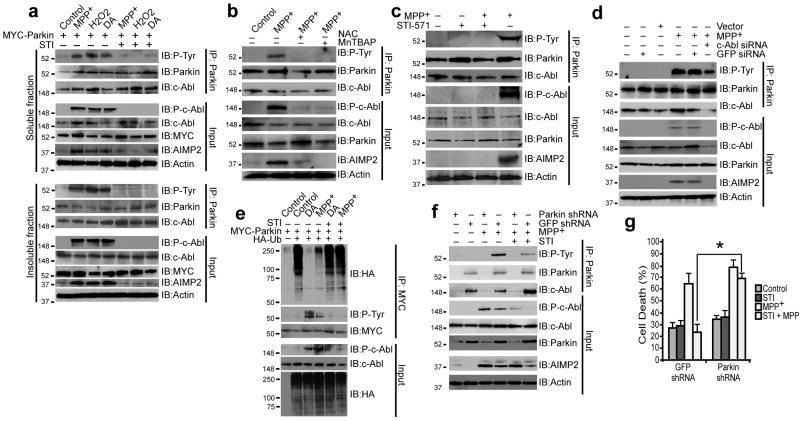

Loss of parkin function after oxidative stress-induced activation of c- Abl

Cellular stress induced by 100 μM MPP+, 250 μM H2O2, or 100 μM DA activated c-Abl in SH-SY5Y cells, as measured by phospho-c-Abl levels (auto-phosphorylation of Y245) (Fig. 2a). Substantial parkin phosphorylation and AIMP2 accumulation was also observed (Fig. 2a). STI-571 prevented parkin phosphorylation and AIMP2 accumulation (Fig. 2a). Pretreatment of cells with superoxide dismutase mimetic MnTBAP (100 μM) or antioxidant N-acetylcysteine NAC (1 mM) for 24 h before MPP+ exposure prevented parkin phosphorylation and AIMP2 accumulation (Fig. 2b). MPP+ treatment also led to STI-571-inhibitable activation of c-Abl, parkin phosphorylation, and AIMP2 accumulation in primary striatal neurons (Fig. 2c). We also performed tyrosine-hydroxylase immunostaining of primary mid-brain neurons treated with MPP+ with or without STI-571. Loss of TH+-immunostaining and damage to neuronal morphology was observed in MPP+ groups which was significantly reversed by STI-571 (Supplemental Fig. 2). MPP+ (100 nM, 24 h) failed to activate c-Abl in pure astrocytes (data not shown), suggesting that this pathway is specific to neurons. Also, we could not detect an active c-Abl signal in astrocytes (Supplemental Fig. 3). Knockdown of c-Abl by siRNA prevented MPP+-induced c-Abl activation, parkin phosphorylation and AIMP2 accumulation, whereas control vector or GFP siRNA had no effect (Fig. 2d). MPP+ and DA substantially reduced parkin's E3-ligase activity, an effect that was blocked by STI-571 pretreatment (Fig. 2e).

Figure 2.

(a) Immunoblots of parkin immunoprecipitates of SH-SY5Y TX-100-soluble (top) and TX-100-insoluble (bottom) fractions of cell lysates transiently transfected with myc-parkin treated with MPP+ (100 μM), dopamine (DA) (100 μM) for 24 h or with H2O2 (250 μM in serum free medium) for 1 h. In lanes 5, 6 and 7, cells were pretreated with STI-571 (STI) at 10 μM for 6 h before exposure to toxins. (b) Immunoblots of parkin immunoprecipitates of SH-SY5Y cell lysates transiently transfected with myc-parkin treated with MPP+ (100 μM) for 24 h. In lanes 3 and 4, cells were pretreated with the SOD mimetic MnTBAP (100 μM) and antioxidant NAC (1 mM) for 24 h before exposure to MPP+. (c) Immunoblots of parkin immunoprecipitates of mouse primary striatal neurons (95% glia-free) treated with 100 nM MPP+ for 24 h with or without STI-571 (2.5 μM for 6 h prior to MPP+ treatment). (d) Immunoblots of parkin immunoprecipitates of SH-SY5Y cells transiently transfected with c-Abl siRNA or GFP siRNA 48 h prior to MPP+ (100 μM) treatment. (e) Immunoblots of myc immunoprecipitates of SH-SY5Y cell lysates transiently transfected with myc-parkin and HA-ubiquitin and treated with MPP+ or DA (100 μM) for 24 h. In lanes 5 and 6, cells were pretreated with STI-571 at 10 μM for 6 h before exposure to MPP+ or DA. (f) Immunoblots of parkin immunoprecipitates of SH-SY5Y cells, infected with either lenti-shRNA to parkin or lenti-shRNA to GFP, treated with 100 μM MPP+. Some samples were incubated with 10 μM STI-571 for 6 h before MPP+ treatment. (g) Cell death plotted as percentage of PI-positive cells amongst GFP-positive cells of SH-SY5Y cells infected with lenti-shRNA-parkin or Lenti-shRNA-GFP alone 48 h prior to treatment with MPP+ (100 μM). Some samples were incubated with 10 μM STI-571 for 6 h before MPP+ treatment. *p < 0.05. Differences among means were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the different treatments as the independent factor followed by Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Representative examples are presented.

To ascertain whether the protective effect of STI-571 requires parkin, its ability to protect against MPP+ was monitored in cells with parkin-knockdown. Parkin knockdown disrupted c-Abl/parkin interaction and reduced STI-571 ability to prevent AIMP2 accumulation after MPP+ treatment (Fig. 2f). STI-571 rescue of MPP+-induced cell death was prevented by parkin knockdown (Fig. 2g). Thus, parkin is indeed required for the protective effects of STI-571.

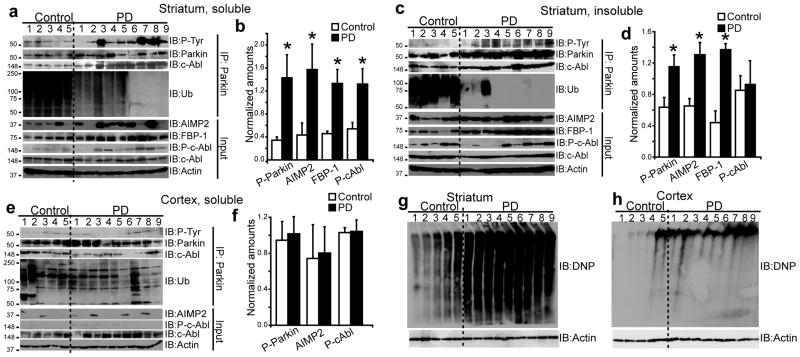

Parkin is tyrosine-phosphorylated in the striatum of PD patients

To determine potential relevance of c-Abl-mediated parkin phosphorylation to PD pathology, we investigated presence of tyrosine-phosphorylated parkin in post-mortem brain tissue prepared from striatum, cingulate cortex, and cerebellum from PD patients and age-matched controls (Supplementary Table 1). There was a 3-fold increase in tyrosine-phosphorylated parkin in soluble fraction of striatal tissue of PD patients compared with controls (Fig. 3a,b). Binding of parkin to c-Abl was increased in PD patients as compared with controls (Fig. 3a,b). In addition, a 4-fold increase in AIMP2, 3-fold increase in FBP-1, and 2.5-fold increase in phospho-c-Abl were observed in PD striatal lysates, with no change in the levels of c-Abl itself (Fig. 3a,b). A significant positive correlation was observed between phospho-parkin and phospho-c-Abl (r = 0.8, p < 0.05), FBP-1 (r = 0.7, p<0.05), and AIMP2 (r = 0.514, p < 0.05) in soluble fraction of striatum. Similarly, a 2-fold increase in tyrosine-phosphorylated parkin, as well as high levels of parkin, a 2-fold increase in AIMP2, and a 3-fold increase in FBP-1 were observed in the insoluble fraction of striatum from PD patients compared with controls (Fig. 3c,d). Consistent with the notion that tyrosine-phosphorylation leads to parkin inactivation, levels of ubiquitinated parkin, measured by ubiquitin reactivity in immunoprecipitated parkin, were significantly lower in both soluble and insoluble fractions of PD striatum samples (Fig. 3a,c).

Figure 3.

Immunoblots of parkin immunoprecipitates (2 mg) prepared from lysates of (a) TX-100-soluble striatum, (c) TX-100-insoluble striatum, and (e) TX-100-soluble cortex lysates. Brain tissue lysates (100 μg) were immunoblotted with antibodies to parkin, AIMP2, FBP-1, ubiquitin (Ub), P-tyr, P-c-Abl (p-Y245), c-Abl, and actin. Ratios of phospho-parkin/IP parkin and AIMP2/actin from lysates of (b) TX-100-soluble striatum, (d) TX-100-insoluble striatum, and (f) TX-100-soluble cortex for control versus PD (* p < 0.05, Student's t-test). OxyBlot analysis of proteins from post-mortem (g) striatum, (h) cortex of PD patients and age-matched controls. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Representative examples are presented.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of parkin was specific to nigrostriatum, as the levels of phospho-parkin, phospho-c-Abl, and AIMP2 in cortex were unaffected (Fig. 3e,f), even in cases with cortical and limbic dementia with Lewy Bodies, and in cerebellum (data not shown), which is largely unaffected in PD. We were unable to detect FBP-1 in cortex reliably. Oxyblot analysis of striata of PD patients showed a prominent pattern of oxidized proteins as compared with controls (Fig. 3g,h). In addition, the oxidation profile was several-fold higher in striatum than in cortex of PD patients, perhaps accounting for the preferential parkin phosphorylation and accumulation of its substrates in the nigrostriatum.

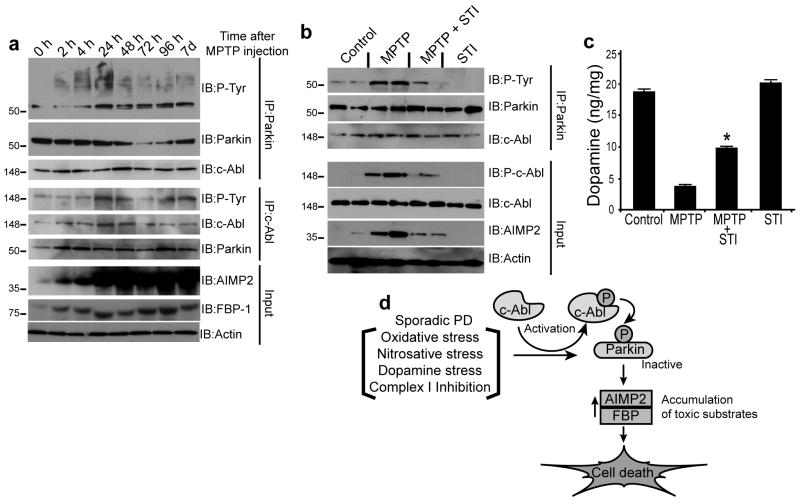

Inhibition of c-Abl protects against MPTP-induced nigrostriatal toxicity

Treatement of mice with the potent parkinsonian neurotoxin, MPTP (Dauer & Przedborski, 2003) (4 doses of 20 mg/kg i.p. every two hours) led to substantial c-Abl activation 24 h after the last dose of MPTP, as indicated by increased striatal levels of phospho-c-Abl, tyrosine phospho-parkin, AIMP2, and FBP-1, sustained for up to seven days (Fig. 4a). STI-571 (10 mg/kg i.p. daily for one week before and one week after MPTP) treatment resulted in protection against MPTP-induced injury, as reflected by significant decreases in levels of phospho-c-Abl, phospho-parkin, and AIMP2 (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the MPTP-induced loss of striatal dopamine was partially mitigated by STI-571 treatment (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that activation of c-Abl contributes to neurotoxic effects of MPTP through inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation of parkin.

Figure 4.

(a) Immunoblots of c-Abl and parkin IP samples (2 mg) from striatum tissue lysates of saline- or MPTP-treated mice (4 × 20 mg/kg, i.p. of MPTP at 2 h intervals at indicated time points). (b) Immunoblots of parkin immunoprecipitates of striatum lysates (100 μg) 7 d after MPTP treatment with or without STI-571(STI) (10 mg/kg, i.p.), (daily injection for 7 d before and 7 d after MPTP injection) compared with saline- and STI-injected control mice. (c) STI-571 prevents MPTP-induced depletion of striatal dopamine in mice, as assessed by HPLC/ECD. Each value is mean±S.E.M. derived from ten animals/group. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test. *p<0.05 for difference from MPTP group. (d) Schematic representation of the pathway by which parkin tyrosine phosphorylation can lead to cell death and PD. Oxidative or dopamine stress from an external source or generated during sporadic PD activates c-Abl. Activated c-Abl tyrosine phosphorylates parkin resulting in loss of ubiquitin ligase activity, leading to accumulation of toxic parkin substrates and neuronal death.

Discussion

Here we report our novel observation that parkin interacts with and is phosphorylated at tyrosine-143 by c-Abl. Activation of c-Abl and parkin tyrosine phosphorylation occur after oxidative and dopamine stress both in vitro and in vivo, causing significant loss of parkin's ubiquitin E3-ligase activity and leading to accumulation of neurotoxic AIMP2 and FBP-1, ultimately compromising parkin's protective function (see scheme, Fig. 4d). STI-571, a selective c-Abl inhibitor, prevented parkin tyrosine phosphorylation, preserved its E3-ligase activity and cytoprotective function. The protective effect of STI-571 was parkin-dependent, since shRNA knockdown of parkin specifically attenuated STI-571 protection. Moreover, we observed tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Abl and parkin, along with accumulation of toxic parkin substrates, AIMP2 (p38/JTV-1) and FBP-1, in nigrostriatum of PD patients. There was significant correlation among tyrosine-phosphorylated parkin, activated c-Abl, and AIMP2 and FBP-1 levels in striatum of PD patients. These data provide convincing evidence for a novel oxidative stress-induced cell signaling pathway that negatively regulates parkin function through c-Abl-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation and may contribute to nigrostriatal neuronal injury and disease progression in sporadic PD.

Recently, it has been reported that oxidative (Wang et al., 2005), nitrosative (Chung et al., 2004; Yao et al., 2004), and dopaminergic (LaVoie et al., 2005) stress impair parkin function by direct modification and/or through alteration in parkin solubility, thus linking parkin to sporadic PD. However, the mechanisms underlying parkin inactivation have remained unclear. Our data provide a molecular mechanism for parkin inactivation, and support a role of parkin in pathogenesis of more common sporadic form of PD. Thus, oxidative and dopamine-stress lead to c-Abl activation, parkin tyrosine phosphorylation and the consequent loss of parkin ubiquitination-dependent cytoprotective function. c-Abl-mediated parkin inactivation in response to oxidative and dopaminergic stress seems to be the dominant pathway induced by these stressors, since the c-Abl inhibitor, STI-571, blocked inactivation of parkin.

Attempts to characterize tyrosine phosphorylation of parkin by capillary HPLC electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) both in vitro and in vivo were unsuccessful, despite the ability to detect the non-phosphorylated peptide in both the precursor and targeted product scans (data not shown). We suspect that detection of Y143 phospho-peptide via MS/MS is not technically feasible due to poor solubility, since parkin peptides containing phosphorylated Y143 failed to dissolve in solvents utilized in the MS/MS analysis (data not shown). Since we were unable to prove definitively via mass-spectrometry that parkin is tyrosine-phosphorylated at Y143, we cannot exclude the possibility that there are additional c-Abl targets that may contribute to the pathogenesis of PD.

Our finding that this pathway is seen predominantly in the striatum suggests that dopamine-containing cells of the nigrostriatum are particularly predisposed. c-Abl activation and parkin tyrosine phosphorylation appear to reflect processes that are unique to nigrostriatum and not necessarily associated with inclusion bodies, since we did not observe c-Abl activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of parkin in the cortex, even in the four PD patients with neocortical Lewy bodies. Furthermore, parkin tyrosine phosphorylation and AIMP2 accumulation in striatum compared with cortex appears to be associated with increased oxidative stress in the striatum of PD patients, as indicated by OxyBlot analysis. Since oxidative stress is intimately involved in sporadic PD, we propose a novel stress-induced cell signaling mechanism featuring activated c-Abl, which inhibits parkin function and consequently increases cell death due to accumulation of cytotoxic parkin substrates, such as AIMP2 (Fig. 4d).

The c-Abl inhibitor STI-571 is widely used chemotherapeutic agent for chronic myelogenous leukemia. The finding that STI-571 inhibits c-Abl's deleterious effects on parkin by preventing it's phosphorylation and preserving its protective function, holds promise for further testing of this agent as a neuroprotective therapeutic for PD. Since STI-571 has limited brain bioavailability (Breedveld et al., 2005), the amount of protection afforded by inhibition of c-Abl in vivo may be greatly improved by using related compounds with enhanced brain penetration. The identification of c-Abl tyrosine phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of parkin activity and its pathological relevance as demonstrated in PD will pave the way for better understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Parkinson's Disease Foundation, San Antonio Area Foundation, American Parkinson Disease Association, Executive Research Council of UTHSCSA, the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN-2) and the European Union (N)EUROPARK consortium. Technical assistance of Xuyean Liao, Doran Pearson, Lora Judge, Heather Dudley, and Wuqiong Ma is acknowledged. We thank F. Fiesel (Hertie Institute, Germany) for helpful suggestions, S.T. Weintraub and K. Hakala for MS analyses (UTHSCSA Institutional Mass Spectrometry Laboratory). Parkin plasmids and constructs, antibodies to AIMP2 and post-mortem human samples were kind gifts from Ted M. Dawson (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). We also thank Dr. Dawson's lab for processing of some human samples. c-Abl and Arg constructs were kind gifts from B. Li (Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore), D. Kufe (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School), Z.M. Yuan (Harvard School of Public Health). Recombinant tyrosine kinase fragment of c-Abl was a kind gift from M. Seeliger and J. Kuriyan (HHMI, UC Berkley). FBP-1 cDNA was kindly provided by D. Levens (NCI, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Lenti-shRNA to parkin was kindly provided by P. Aebischer and R. Zuffrey (EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland). STI-571 was provided by Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland.

References

- Braak H, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedveld P, et al. The effect of Bcrp1 (Abcg2) on the in vivo pharmacokinetics and brain penetration of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec): implications for the use of breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein inhibitors to enable the brain penetration of imatinib in patients. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2577–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KK, et al. Parkin ubiquitinates the alpha-synuclein-interacting protein, synphilin-1: implications for Lewy-body formation in Parkinson disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:1144–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KK, et al. S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin's protective function. Science. 2004;304:1328–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1093891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti O, et al. The p38 subunit of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex is a Parkin substrate: linking protein biosynthesis and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1427–37. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Science. 2003;302:819–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1087753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantschel O, Superti-Furga G. Regulation of the c-Abl and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrm1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P, Olanow CW. Understanding cell death in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:S72–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–8. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HS, et al. Accumulation of the authentic parkin substrate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase cofactor, p38/JTV-1, leads to catecholaminergic cell death. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7968–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2172-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HS, Kim SW, Sriram SR, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Identification of Far Upstream Element-binding Protein-1 as an Authentic Parkin Substrate. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16193–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, Weihofen A, Schlossmacher MG, Selkoe DJ. Dopamine covalently modifies and functionally inactivates parkin. Nat Med. 2005;11:1214–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N, et al. Diverse effects of pathogenic mutations of Parkin that catalyzes multiple monoubiquitylation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Molecular pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:57–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW, Tatton WG. Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:123–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przedborski S, et al. Role of neuronal nitric oxide in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4565–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura H, et al. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet. 2000;25:302–5. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Mayer BJ. Abl: mechanisms of regulation and activation. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d31–42. doi: 10.2741/a767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram SR, et al. Familial-associated mutations differentially disrupt the solubility, localization, binding and ubiquitination properties of parkin. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2571–86. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, et al. Activation of the cytoplasmic c-Abl tyrosine kinase by reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17237–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, et al. MPTP and DSP-4 susceptibility of substantia nigra and locus coeruleus catecholaminergic neurons in mice is independent of parkin activity. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:312–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KK, Yuan ZM. c-Abl stabilizes p73 by a phosphorylation-augmented interaction. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3418–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten RA. Cycling, stressed-out and nervous: cellular functions of c-Abl. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:179–86. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Coelln R, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin-associated Parkinson's disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:175–84. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0924-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, et al. Stress-induced Alterations in Parkin Solubility Promote Parkin Aggregation and Compromise Parkin's Protective Function. Hum Mol Genet. 2005 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, et al. Parkin phosphorylation and modulation of its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3390–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao D, et al. Nitrosative stress linked to sporadic Parkinson's disease: S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10810–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404161101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Oxidative stress and genetics in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:240–50. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, et al. Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin- protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13354–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240347797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.