Abstract

This analysis uses data from the Care of Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia (CareAD) study to investigate which factors increase risk of death in patients who are in the advanced stages of dementia. The hypothesis of this analysis was that specific illnesses with known high mortality would be associated with increased risk of death in the population of nursing home residents with advanced dementia, after controlling for demographic variables and disease stage variables. Baseline data on 123 end-stage dementia nursing home residents were analyzed with a Cox proportion hazards regression. Of the comboridities studied, pneumonia was the only illness significantly associated with shortened survival. This information can help healthcare professionals assist surrogate decision makers in making medical decisions regarding the treatment of co-morbid medical illness in persons with advanced dementia.

Introduction

The irreversible dementias, which include conditions such as Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia and mixed dementia, are progressive, degenerative brain diseases and are most prevalent in the elderly.1,2 The National Center for Health Statistics ranked Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, as the eighth leading cause of death in the United States (US) in 2003, and as the seventh leading cause for the years 2004 – 2006. 3,4 A 1999 study using prevalence data estimated that AD accounted for 7% of all deaths, placing it on par with cerebrovascular disease as the third leading cause of death in the US.5 A national study on the place of death for older persons with dementia found that 67% of dementia related deaths occurred in nursing homes.6

Various factors may play a role in determining survival time for individuals with dementia. 7,8 Factors commonly associated with a higher risk for death in dementia are increasing age, male sex, and greater disease severity. 9–12 There are conflicting or inconclusive reports regarding the role of psychiatric symptoms, dementia diagnosis, and comorbid illnesses. 7,13–16 Thus, among the more than 30 studies that have investigated predictors of survival in dementia, little consensus has emerged regarding factors that reliably predict the length of time to death for individuals with dementia.7,9,10

Variability in survival time has also been reported in studies that examine individuals in the severe disease stage. In one study of 11 hospice dementia patients, all of whom were classified as having severe dementia, the range of survival spanned from 2 days to beyond 16 months.17 Similarly, in a longitudinal study of 165 nursing home residents who met Medicare hospice criteria, Schonwetter et al.18, found that the range in survival time was 0 days to 2.13 years. These data support the assertion that individuals with advanced dementia who receive care at a nursing facility can survive for long periods of time and at the same time are at risk for sudden, life threatening events such as respiratory and urinary tract infections and pressure ulcers, which are difficult to predict.18,19

Few studies have examined the contribution of specific medical comorbidities or psychosis as predictors of time to death in a sample of patients who were all judged as being in late stage dementia. The current analysis uses data from the Care of Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia (CareAD) study to identify factors that increase risk of death in patients who are in the advanced stages of dementia. We chose to investigate the following medical and psychological comorbities: cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus, pneumonia, and psychosis. The first three medical conditions were chosen because they are chronic conditions and are known to decrease life expectency.20–22 Pneumonia was included because it is estimated to be the most common immediate cause of death in patients with dementia.23 Psychosis was chosen because of a recent finding that patients who exhibit symptoms of tactile hallucinations die sooner than those who do not.24 The hypothesis examined in the current analysis is that one or more of these illnesses would be associated with increased risk of death in the population of nursing home residents with advanced dementia, after controlling for demographic variables and disease severity variables.

Methods

The CareAD study was a longitudinal, cohort study conducted in three Maryland nursing homes from December 2000 to August 2004.25 The key aims of the study were to document the medical and psychiatric problems and treatment decisions that are faced in end-stage dementia and to identify criteria that predict death within 6 months. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions and the University of Maryland and by the research review committees at each study site.

The methods of the CareAD study are described in detail elsewhere.25 In brief, residents from three nursing homes were recruited and followed over a period of 2.75 years. Residents were eligible to be enrolled in the study if they 1) had a diagnosis of dementia, and 2) met hospice criteria for dementia or were receiving hospice or palliative care. Once a resident was identified as eligible for the study, the resident’s surrogate decision maker was contacted and asked for permission to enroll the resident and the surrogate into the study. Surrogates who agreed provided written informed consent for themselves and the resident, except in one case in which the subject was determined to have capacity to consent. Of the 289 residents identified as eligible for the study, a total of 126 residents were enrolled into the study. In this group of 126, two residents did not fully satisfy the eligibility criteria, and a third was withdrawn by the surrogate after 1 month. This analysis uses data on the remaining 123 residents who were followed from baseline to time of death, discharge, or the close of the study.

Residents’ demographic data were collected from their medical records and in interviews with their surrogates. Data on residents’ medical and psychiatric status were collected by trained research assistants who performed a systematic review of their medical records using a standardized data collection instrument. Baseline data were collected on the presence of any medical and psychiatric problems that occurred during the 6 months prior to the resident’s study enrollment or since admission if they had been residing in the nursing home for less than 6 months.

Residents’ cognitive status at baseline was tested with the Severe Impairment Rating Scale (SIRS), a 22-point scale for measuring cognitive function in individuals who score 5 or less on the Mini Mental State Examination. 26,27 It has been shown to have good inter-rater and re-test reliability and to correlate with the Mini-Mental State Examination ( Pearson r = 0.84) and the Glasgow Coma Scale (Pearson r =0.85), which have been shown to have satisfactory validity for measuring cognitive impairment in patients with dementia and patients with acute cerebral disorders. 26–30

Data analysis

A Cox proportional hazard regression was conducted with Stata software to examine the relationship between survival time with five comorbities: cardiovascular disease, COPD, diabetes mellitus, psychosis and pneumonia.31,32 Since some studies suggest that age, gender and measures of dementia severity influence survival, we included these covariates in the regression analysis. In addition, since the data were collected from three different nursing homes, an indicator variable for nursing home site was generated to account for unmeasured differences among the nursing homes.

The data analysis included the following steps: 1) exploratory analysis to describe the data, 2) bivariate analysis using independent t-tests and chi-square tests to investigate trends and associations between variables, 3) inspection of Kaplan-Meier graphs and survival time summaries to investigate potential interactions between variables, 4) univariate and multivariate regression analyses with the Cox proportional hazards model, and 5) stepwise regression and likelihood ratio tests to determine the most appropriate model. Bootstrapping was used to construct the confidence intervals and p-values in the final model. Once the final regression model was derived, regression diagnostics were used to test that the model passed the Cox model assumption of proportional hazards and to verify that possible outlying data points did not have significant influence on the results. A p-value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive data on the nursing home residents are displayed in Table 1. At baseline, the mean age of the residents was 81.5 (SD 7.1), 55.3% were females, and 83.7% were white. The majority of residents had a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease (57.7%). The median years with symptoms of dementia was 8 (range: 0–33); the median SIRS score was 11 (range: 0–22).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants and Relationship to Survival (n=123)

| Residents’ Characteristics | Total Sample |

Died (n= 93) |

Survived or Discharged (n=30) |

Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female % (n=68) | 55.3 | 53.8 | 60.0 | χ2 (df=1) = 0.357 | 0.550 |

| Male % (n=55) | 44.7 | 46.2 | 40.0 | ||

| Age (years) Mean(SD) (n=123) | 81.5 (7.1) | 82.1 (7.0) | 79.6 (7.0) | t = −1.705 | 0.095 |

| Race (n=123) | |||||

| White % (n=103) | 83.7 | 83.9 | 83.3 | χ2 (df=1)= 0.005 | 0.945 |

| Non-white % (n=20) | 16.3 | 16.1 | 16.7 | ||

| Residence (n=123) | |||||

| Site 1 % (n=41) | 33.3 | 35.5 | 26.7 | χ2 (df=2)=1.068 | 0.586 |

| Site 2 % (n=60) | 48.8 | 46.2 | 56.7 | ||

| Site 3 % (n=22) | 17.9 | 18.3 | 16.7 | ||

| Health status characteristics | |||||

| Dementia diagnosis (n=123) | |||||

| Alzheimer disease % (n=71) | 57.7 | 62.4 | 43.3 | χ2 (df=1) = 3.367 | 0.067 |

| Other types of dementiaa % (n=52) | 42.3 | 37.6 | 56.7 | ||

| Years with dementia symptomsb Mean (SD) (n=122) | 8.6 (5.8) | 8.8 (6.0) | 7.9 (5.2) | t = −0.807 | 0.423 |

| Years at nursing home Mean (SD) (n=123) | 1.9 (3.0) | 2.1 (3.3) | 1.6 (1.8) | t = −1.025 | 0.308 |

| SIRSc score Mean (SD) (n=121)c | 10.3 (6.7) | 10.1 (6.4) | 11.1 (7.6) | t = 0.660 | 0.513 |

| Health problemsd | |||||

| Heart disease % (n=123) | 48.0 | 48.4 | 46.7 | χ2 (df=1) = 0.027 | 0.870 |

| Pulmonary disorders % (n=123) | 17.9 | 18.3 | 16.7 | χ2 (df=1) = 0.040 | 0.841 |

| Diabetes Mellitus % (n=123) | 13.8 | 14.0 | 13.3 | χ2 (df=1) = 0.008 | 0.929 |

| Hallucinations and/or delusions % (n=123) | 26.8 | 26.9 | 26.7 | χ2 (df=1) = 0.0005 | 0.982 |

| Pneumonia % (n=123) | 25.2 | 29.0 | 13.3 | χ2 (df=1) = 2.966 | 0.085 |

Vascular dementia, mixed dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, dementia type not specified, dementia due to HIV, dementia due to Parkinson disease

Missing data- Years with dementia symptoms (n=1), SIRS score (n=2)

Severe Impairment Rating Scale

Health problems reported in medical records during 6 months preceding enrollment

Of the 123 residents in this sample, 93 died, 7 were discharged from the facilities and alive at the final interview, and 23 were living at the nursing homes at the final interview. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences in terms of gender, age, race, site, years with symptoms, years at nursing home, SIRS score or, comorbidity between those who died and those who did not. There was a trend for participants with non-AD types of dementia to be alive (χ2 =3.367, p=.067).

Residents were followed on average for 60.8 weeks. (The total follow-up time for the sample was 7,477 person-weeks.) The median survival time overall was 43.6 weeks, and the overall incidence rate was .012 deaths per person-week. The Kaplan-Meier survivor function estimated that, for a nursing home resident in this study, the probability of surviving beyond 6 months is 68.0%, and the probability of surviving beyond one year is 48.6%.

Table 2 displays the results from the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. In the univariate analysis, pneumonia (p = .008) was significantly associated with decreased survival but heart disease, pulmonary disorder, diabetes mellitus, and psychosis were not. The univariate model estimated that subjects who had a history of pneumonia in the 6 months leading up to enrollment were at 2.10 times greater risk for death compared to those with no 6 month history of pneumonia (95% CI: 1.21–3.65.) Nursing home site was also found to have a statistically significant relationship with risk of death. Additionally, the results from the univariate analysis suggest that type of dementia could have an association with risk of death (p=.09).

Table 2.

Crude and Adjusted Relative Hazard of Mortality (n=123)

| Univariate Analyisisa(n=123) | All Covariates (n=120) | Final Model b (n=120) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Site 2c | .62 | .41–.96 | .03 | .63 | .27–1.45 | .28 | |||

| Site 3c | .49 | .26–.92 | .03 | .39 | .12–1.29 | .12 | |||

| Female gender | .72 | .47–1.09 | .12 | .96 | .43–2.15 | .92 | .69 | .41–1.15 | .15 |

| Age d | 1.02 | .98–1.05 | .32 | 1.04 | .99–1.10 | .14 | 1.03 | .98–1.08 | .25 |

| Years at nursing homee | .97 | .90–1.04 | .37 | 1.02 | .90–1.15 | .80 | |||

| Mixed or other dementia | .69 | .45–1.06 | .09 | .57 | .30–1.09 | .09 | .59 | .35–1.00 | .05 |

| Psychosis | 1.12 | .71–1.76 | .62 | 1.03 | .50–2.11 | .94 | |||

| Pulmonary disorders | 1.43 | .80–2.57 | .23 | .96 | .42–2.18 | .92 | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.32 | .65–2.67 | .44 | 1.74 | .79–3.80 | .17 | |||

| Pneumonia | 2.10 | 1.21–3.65 | <.01 | 2.06 | .93–4.56 | .08 | 2.23 | 1.19–4.20 | .01 |

| Heart Disease | 1.23 | .81–1.87 | .34 | 1.27 | .69–2.33 | .45 | |||

| SIRSf score 6–13 g (n=121) | 1.26 | .74–2.15 | .39 | 1.40 | .63–3.13 | .41 | 1.43 | .76–2.69 | .27 |

| SIRS score 14+ g (n=121) | .83 | .47–1.46 | .52 | .72 | .29–1.81 | .48 | .80 | .38–1.66 | .55 |

| 7 + years with symptoms h (n=122) | .80 | .52–1.23 | .30 | .68 | .36–1.30 | .24 | .76 | .46–1.27 | .30 |

Missing data—SIRS scores (n=2), years since dementia symptoms began (n=1)

Final model includes gender, age, site, SIRS, dementia type, pneumonia, diabetes mellitus, and years with dementia symptoms

Reference category: Site 1

With every one year increase from mean age (81.5 years)

With every one year increase from mean years in nursing home (1.9 years)

Severe Impairment Rating Scale

Reference category: SIRS score 0–5

Reference category: 0–6 years with symptoms

To further examine statistically significant findings from the univariate analysis, a multivariate regression analysis was performed to control for all variables. Similarly to the results in univariate model, this full model estimated that pneumonia would increase a subject’s risk of death by 2.06 times (95% CI: .93– 4.56), although this effect was no longer statistically significant at the .05 level (p=.08). The estimates of risk of death by dementia type and nursing home site were also consistent with the results of the univariate analysis.

The final model reveals a statistically significant difference in risk of death comparing residents by history of pneumonia and by dementia type. Specifically, the model estimates that the risk of death at a given day for a resident who was diagnosed with pneumonia within the six months leading up to enrollment is 2.23 times the risk for a resident with no six month history of pneumonia (95%CI: 1.19–4.20, p= .01). The risk of death for a resident with mixed or other non-AD dementias is estimated to be reduced by 41% compared to the risk of residents with a diagnosis of AD (95% CI: .35 –1.00, p=.05).

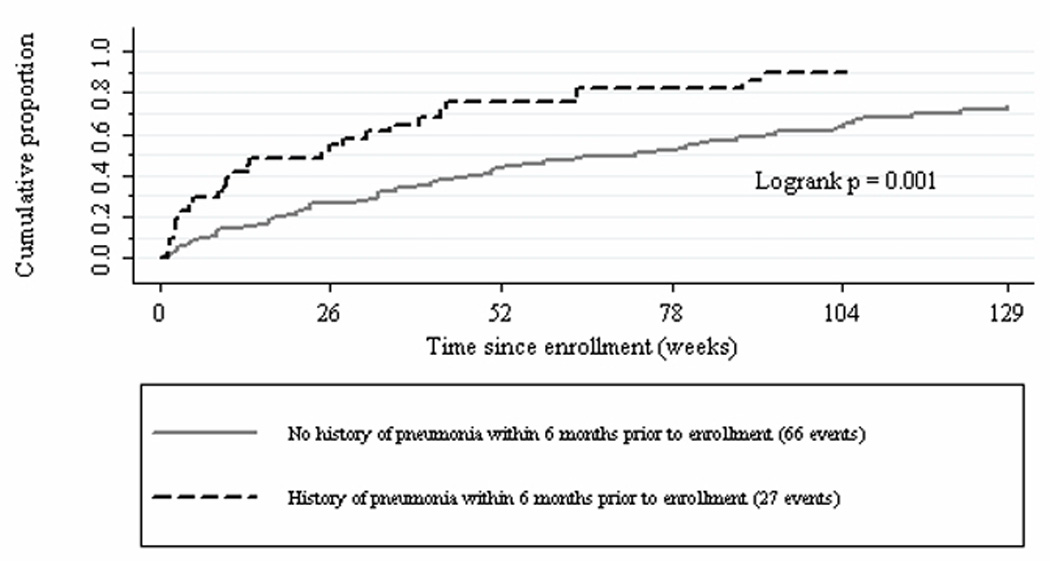

Figure 1 presents the Kaplan-Meier estimation of survival in participants who had or had not been diagnosed with pneumonia during the 6 months prior to enrollment. Residents with pneumonia had a 51.6% chance of surviving past 6 months, while those without pneumonia had a 74% chance (Logrank χ2=10.86, p=.001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimation of cumulative proportion of nursing home residents who died

Discussion

This study of individuals with dementia who were hospice eligible found that pneumonia occuring during the 6 months prior to enrollment, but not heart disease, pulmonary disorders, diabetes, hallucinations or delusions, was significantly associated with decreased survival time controlling for gender, age, dementia type, SIRS score and years with dementia symptoms, and that participants diagnosed with Alzheimer disease were more likely to die than individuals with a diagnosis of mixed or other dementia. In this sample, individuals who had been diagnosed with pneumonia within the 6 months prior to their enrollment were at 2.23 times greater hazard of death than those without a pneumonia diagnosis. Individuals who had mixed or other dementias had an estimated 41% lower adjusted risk for death than those with Alzheimer dementia.

Although more than 100 studies have been conducted to investigate factors related to survival in dementia, few have focused on late stage patients or examined the contribution of medical comorbidities. In the studies that have examined survival in populations of nursing home residents with severe dementia, the most consistent findings have been that advanced age and impaired functional status predict survival time.17, 18, 33 Although heart disease, diabetes, and COPD increase risk of death in the general population, this does not appear to be the case in this sample of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. This may be explained by: 1) survivor bias, 2) better medical treatment in the controlled environment of long term care facilities, or 3) a predominating impact of pneumonia alone.

Given the fact that pneumonia has been found in several death certificate and autopsy studies to be the leading cause of death in dementia patients, it is not surprising that we found that residents with a baseline diagnosis of pneumonia had significantly decreased survival time compared to those who did not.23, 34,35 However, we did not examine documentation for cause of death, so we cannot conclude that the subjects died from pneumonia.

A more complex question prompted by this finding is whether pneumonia can be reliably used in making a prognosis of time to death in this patient population. Thus far, of the studies that have concentrated on prognostic factors for death in patients with advanced dementia, pneumonia is not consistently found to be a reliable predictor. In the retrospective study of two large groups of nursing home residents (n=11,430), Mitchell et al.33 did not find substantial evidence that a diagnosis of pneumonia should be used to predict death within 6-months. It should be noted, however, that only a small portion of that sample was diagnosed with pneumonia, so it is possible that a predictive effect would not have been captured in statistical analysis. In a prospective study of 165 hospice patients with dementia, Schonwetter et al.18 found that patients with pneumonia were not significantly more likely to die within 6 months of study enrollment. Contrastingly, pneumonia was identified by van der Steen et al.14 to be a signficant predictor of death in a prospective study of 944 nursing home residents in various stages of dementia. In their study, over one-third of the residents who developed a diagnosis of pneumonia died within 6 months of their diagnosis.

Since residents in this study were only modestly more at risk for death (2.25 times) compared to other comparable residents, we suggest that those making medical decisions for persons with advanced dementia be told that the risk of death is modestly increased after pneumonia has occurred. Looked at another way, the median survival time for those with a history of pneumonia was 25 weeks compared to 73 weeks for those without pneumonia. Stating the data this way may help convey the information that a diagnosis of pneumonia is associated with a meaningfully shorted life expectancy in this population of nursing home residents with advanced dementia.

In this analysis, residents with vascular dementia, mixed dementia, or other types of dementia had a lower risk of death compared to those residents with Alzheimer disease. Of the previous few studies that have investigated differences in survival between Alzheimer and other types of dementia, the results have been mixed.7, 36–38 In a study of community residents with incident dementia cases, Fitzpatrick et al.36 found that persons with vascular dementia were at greater risk for death than those with AD and mixed dementia. Their study also found that subjects with mixed and vascular dementia had higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, hypertension and history of stroke.36 Mortel et al.37 found that survival times were similar among both patients with vascular dementia and AD when patients underwent treatment for risk factors for cerebrovascular disease. It is possible that participants in this study were receiving vigilant care for cerebrovascular disease risk factors such as hypertension, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia, which could prolong survival time. It is also plausible that those patients with the highest degrees of these risk factors may have died earlier in the illness and that the results demonstrate a survivor bias.39

Even though all participants in this study either met current criteria for receiving hospice care or were judged by their physician to be likely to die within 6 months, survival times covered a much broader range (IQR: 17–122 weeks) than we had anticipated. The Kaplan-Meier survival function estimated that the probability of surviving beyond 6 months is 67.7% and the probability of surviving beyond one year is 50.4%. The residents in this sample tended to survive longer than residents in two studies of similar samples, where the majority of patients died within 6 months.17,18 This may be explained by the fact that our sample was taken from a nursing home population whereas the patients in the other two studies were residing in hospice facilities. In both this study and in Schonwetter’s 19 sample, there is a consistent finding that a subset of patients with end-stage dementia will survive far longer than predicted, beyond 2 years.

One limitation in this analysis was that two demographic factors, gender and site, were not independent of one another. Since gender was unevenly distributed across nursing home sites, our ability to test the signficance of one variable over another was limited. Second, there may have been interactions between certain predictors that the sample size was too small to demonstrate. Further, because this study included individuals residing in only 3 facilities in a single limited geographic area, generalization to residents in other geographic area should be made with caution.

Dementia is a leading cause of death in the US, and the majority of dementia related deaths occur in nursing homes. 3,4,6 Two recent qualitative studies found that a recurring theme in surrogate decision makers experiences are deficiencies in surrogates’ understanding of the disease trajectory of dementia and lack of communication with the treating healthcare professionals. 40,41 Knowledge of events in late stage dementia that influence time to death might aid families in their surrogate decision making experience.41 We recommend that healthcare professionals assist surrogate decision makers by conveying how pneumonia may affect the prognosis of a patient with dementia.

Table 3.

Comparison of median survival by diagnosis

| Diagnosis | Median Survival (weeks) |

|---|---|

| All subjects | 50.57 |

| No history of pneumoniaa | 72.57 |

| History of pneumoniaa | 24.57 |

| Alzheimer dementia | 42.14 |

| Mixed dementia and other dementias | 83.43 |

Within 6 months prior to enrollment

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank Benilton Carvalho for his valuable help and guidance with the statistical analysis of the data.

Funding Source: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, grant no. NS39810

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have reported no conflicts of interest in relation to this research manuscript.

Contributor Information

Betty S. Black, Email: bblack@jhmi.edu.

Peter Rabins, Email: pvrabins@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Cummings JL, Benson DF. Dementia: a clinical approach. 2nd ed. Stoneham (MA): Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Steele CD. Practical dementia care. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2004. National vital statistics reports. 2007;56(5) Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr56/nvsr56_05.pdf. [PubMed]

- 4.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Division of Vital Statistics. Deaths: Final data for 2006. National vital statistics reports. 2009;57(14) Available from: http://www.cdc.gov./NCHS/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_14.pdf. [PubMed]

- 5.Ewbank DC. Deaths attributable to Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:90–92. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guehne U, Riedel-Heller S, Angermeyer MC. Mortality in dementia. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:153–162. doi: 10.1159/000086680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodarty H, McGilchrist C, Harris L, Peters KE. Time until institutionalization and death in patients with dementia. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:643–650. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540060073021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dijk P, Dippel D, Habbema J. Survival of patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:603–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb03602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguero-Torres H, Fratiglioni L, Winblad B. Natural history of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: review of the literature in the light of the findings from the Kungsholmen project. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:755–766. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(1998110)13:11<755::aid-gps862>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gambassi G, Landi F, Lapane KL, Sgadari A, Mor V, Bernabei R. Predictors of mortality in patients with Alzheimer disease living in nursing homes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:59–65. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewey ME, Saz P. Dementia, cognitive impairment and mortality in persons aged 65 and over living in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:751–761. doi: 10.1002/gps.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose BA, Slama H, Johnson JK, Yaffe K, et al. Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:719–725. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173837.82820.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Steen JT, Mehr DR, Kruse RL, Ribbe MW, van der Wal G. Dementia, lower respiratory tract infection, and long-term mortality. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmer C, Joly P, Letenneur L, Commenges D, Dartigues J-F. Mortality with dementia: results from a French prospective community-based cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:642–648. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.7.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapane KL, Gambassi G, Landi F, Sgadari A, Mor V, Bernabei R. Gender differences in predictors of mortality in nursing home residents with AD. Neurology. 2001;56:650–654. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanrahan P, Luchins D. Feasible criteria for enrolling end-stage dementia patients in home hospice care. The Hospice Journal. 1995;10:47–54. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1995.11882798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schonwetter RS, Han B, Small BJ, Martin B, Tope K, Haley WE. Predictors of six-month survival among patients with dementia: an evaluation of hospice Medicare guidelines. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:105–113. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuart B, Herbst L, Kjnzbrunner B, Preodor M, Connor S, Ryndes T, et al. Medical guidelines for determining prognosis in selected non-cancer diseases. The Hospice Journal. 1996;11(2):47–63. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1996.11882820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peeters A, Mamun AA, Willekens F, Bonneux L. A cardiovascular life history. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:458–466. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feenstra TL, van Genugten, Hoogenveen RT, Wouters ER, Rutten-van Molken M. The impact of aging and smoking on the future burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:590–596. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2003167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franco OH, Steyerberg EW, Hu FB, Mackenbach J, Nusselder W. Associations of diabetes mellitus with total life expectancy and life expectancy with and without cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1145–1151. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keene J, Hope T, Fairburn CG, Jacoby R. Death and dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:969–974. doi: 10.1002/gps.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suh G, Yeon BK, Shah A, Lee J-Y. Mortality in Alzheimer’s disease: a comparative prospective Korean study in the community and nursing homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:26–34. doi: 10.1002/gps.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black BS, Finucane T, Baker A, Loreck D, Blass D, Fogarty L. Health problems and correlates of pain in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:283–290. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213854.04861.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabins PR, Steele CD. A scale to measure impairment in severe dementia and similar conditions. Am J Geriatr Psych. 1996;4:247–251. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199622430-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jennett B, Teasdale G. Assessment of impaired consciousness. In: Jennett B, editor. Management of head injuries. Philadelphia: FA Davis Co; 1981. pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad K. The Glasgow Coma Scale: a critical appraisal of its clinimetric properties. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(7):755–763. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton LC. Statistics with Stata: updated for Version 9. Belmont (CA): Thompson Brooks/Cole; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, Park PS, Morris JN, Fries BE. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291:2734–2740. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas BM, Starr JM, Whalley LJ. Death certification in treated cases of presenile Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in Scotland. Age Ageing. 1997;26:401–406. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.5.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns A, Jacoby R, Luthert P. Cause of death in Alzheimer’s disease. Age Ageing. 1990;19:341–344. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.5.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Kawa CH, Jagust W. Survival following dementia onset: Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2005;229:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mortel KF, Meyer JS, Rauch GM, Konno S, Haque A, Rauch RA. Factors influencing survival among patients with vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Stroke Cerebrovas Dis. 1999;8(2):57–65. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3057(99)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molsa PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne UK. Survival and cause of death in Alzheimer disease and multi-infarct dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;74:103–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1986.tb04634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Habbema J, Dippel D. Survivors-only bias in estimating survival in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementias [letter] Neurology. 1986;36:1009. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.1009-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forbes S, Bern-Klug M, Gessert C. End-of-life decision making for nursing home residents with dementia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2000;32:251–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gessert C, Forbes S, Bern-Klug M. Planning end-of-life care for patients with dementia: roles of families and health professionals. Omega. 2001;42(4):273–291. doi: 10.2190/2mt2-5gyu-gxvv-95ne. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]