Abstract

A set of nine 2,7-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamides and one 2,6-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamide were synthesized. The compounds were evaluated for their in vitro anti-tuberculosis activity versus replicating, non-replicating, multi- and extensive drug resistant Mtb strains. The MIC90 values of seven of these agents were ≤ 1 μM against the various tuberculosis strains tested. A representative compound of this class (1) was screened against seven non-tubercular strains as well as other non-mycobacteria organisms and demonstrated remarkable microbe selectivity. A transcriptional profiling experiment of Mtb treated with compound 1 was performed to give a preliminary indication of the mode of action. Lastly, the in vivo ADME properties of compounds 1, 3, 4, and 6 were assessed. The 2,7-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamides are a drug-like and synthetically accessible class of anti-TB agents that have excellent selective potency against multi- and extensive drug resistant TB and encouraging pharmacokinetics.

Keywords: Antituberculosis, imidazo[1, 2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamides, MDR-TB, XDR-TB

Tuberculosis (TB) is a serious global health risk. More than one third of the human population is infected resulting in an estimated 1,700,000 deaths in 2006 (1.5 million in HIV-negative people and 0.2 million in HIV-positive people).1 Moreover, there were a staggering 14,400,000 cases estimated worldwide in 2006, with 83% of the total cases located in the African, South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions.1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of TB, is an airborne pathogen that can be spread from one person to another by close contact. Because it can lie dormant in a latent state for many years, it is a silent killer among the poor, HIV-infected, immune-compromised and the elderly. To make matters worse, multiple-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB, strains that are resistant to first line drugs isoniazid and rifampin) and extensively drug resistant TB (XDR-TB, strains that are resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, as well as any fluoroquinolone and at least one of three injectable second-line drugs, such as amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin) are on the rise.2 Most alarming is the emergence of extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis “XXDR-TB” (the proposed designation for TB that is resistant to all first- and second-line TB drugs), which is now documented.3 In 2008, there were 12,898 cases of TB provisionally reported in the United States.

A focus of our laboratories is to facilitate the decline of TB by the identification of therapeutically effective anti-TB agents to augment the long dosing regimen of first line drugs.5 Herein we call attention to the in vitro potency of the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamide scaffold. To our knowledge the anti-TB activity of the 2,7-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamide class is unprecedented. Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-nitroso derivatives were reported in 2004 to impart notable anti-TB activity (MIC = 3.1 μg/mL vs. H37Rv-TB) concurrent with notable toxicity to VERO cells (IC50 = 3.6 μg/mL).6 Also in 2004, rationally designed imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-hydrazones7 were reported but were all inactive against H37Rv-TB at 6.25 μg/mL. Most recently, in 2009, functionalized 3-amino-imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines were reported as in vitro Mtb glutamine synthetase inhibitors, but without assessment of the in vitro activity versus H37Rv-TB.8 While reports on the syntheses of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamides date to 1965,9 the 2,7-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine architecture is atypical within the cannon of medicinal chemistry literature and is unprecedented within the TB lexicon.

Since 2007, we have had a collaborative agreement with Dow AgroScience to screen their compound inventory for inhibitors of Mtb. This effort, coupled with a program to elaborate novel heterocylic anti-TB agents from fragment-based studies of mycobacterial siderophores,10 led to the identification of an ethyl 2,7-dimethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxylate. This compound had weak activity against H37Rv TB (MIC ~ 65 μM, average) but was nonetheless an attractive heterocyclic scaffold to optimize as we did previously with related heterocyclic classes.11

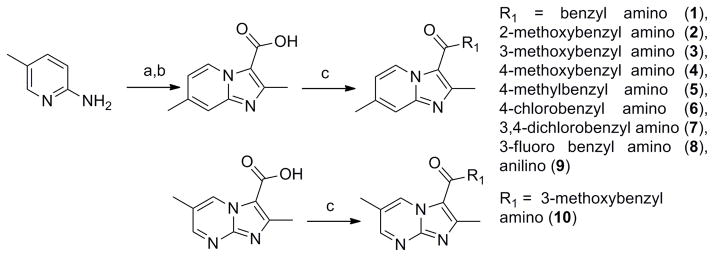

The simplest synthesis of the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxylate ring system12 is the straightforward reaction of 2-amino-4-picoline with ethyl 2-chloroacetoacetate to give the desired heterocyclic scaffold in 78% yield (Scheme 1). Saponification with lithium hydroxide followed by acidic work up gave the free acid which was then easily converted to various amide analogs through classical EDC-mediated couplings in good yields (70% for 1).

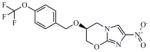

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines.

Reagents: (a) Ethyl 2-chloroacetoacetate, DME, reflux, 48 h.; (b) 1. LiOH, EtOH, 2. HCl, 56 h.; (c) EDC, DMAP, R1, ACN, 16 h.

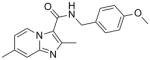

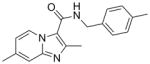

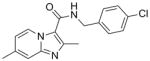

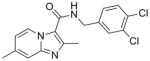

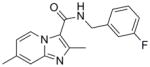

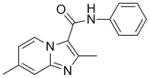

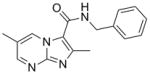

Our initial structure-activity relationship (SAR) strategy evaluated a representative panel of nine imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxamide analogs. The chosen imidazopyridine analogs included the classical Topliss13 set of benzyl, 4-methoxyphenyl, 4-methylphenyl, 4-chlorophenyl and 3,4-dichlorophenyl amides. This set was augmented by ortho- and meta-methoxyphenyl analogs to probe possible steric effects. Next, due to potential metabolic issues associated with a benzylic methylene group, the corresponding aniline was prepared as well as a fluorine replacement for the chlorine. Finally, we explored the influence on potency by changing the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine to an imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine core (as in 10).

Table 1 summarizes the in vitro anti-TB activity of these ten analogs in three different media (GAS14, GAST15 and 7H1214), their potency against non-replicating “latent” TB (LORA16) and an assessment of their toxicity by the VERO17 assay. All compounds were potent (MIC <10 μM in the GAS assay media) with the exception of the aniline derived analog (9, MIC >128 μM) suggesting that in the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine series the benzylic position is important for activity. Additionally, by running the TB assay in three different media (GAS, GAST and 7H12), we eliminated concern that the activity of these compounds might be carbon source dependent, a flaw discovered in the pyrimidine-imidazoles reported by Pethe and colleagues at Novartis18 as the GAS and GAST assays use glycerol-alanine-salts as the carbon source while the 7H12 media uses palmitic acid.

Table 1.

In vitro evaluation of compounds 1 – 10 against H37Rv-TB in various assays and media (MIC90 in μM) and stability to rat liver (RLM) and human liver (HLM) microsomes.

| Compound ID | Mol Wt | Calc. Clog P* | GAS | GAST | 7H12 | LORA | VERO | RLM % metab. (30 min) | HLM % metab. (30 min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

279.34 | 3.60 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 1.9 | 53.6 | >128 | 71 | 59 |

2 |

309.36 | 3.51 | 2.8 | 1.9 | >128 | ||||

3 |

309.36 | 3.51 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 5.9 | 31.4 | >128 | 80 | 47 |

4 |

309.36 | 3.51 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 1.35 | 10.5 | >128 | 69 | 30 |

5 |

293.36 | 4.09 | 0.51 | 0.80 | 54.7 | ||||

6 |

313.78 | 4.31 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 1.94 | 28 | >128 | 79 | 82 |

7 |

348.23 | 4.90 | 9.3 | 14.4 | |||||

8 |

297.33 | 3.74 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 1.98 | 40.1 | >128 | ||

9 |

265.31 | 3.42 | >128 | >128 | |||||

10 |

310.35 | 2.51 | 0.10 | 0.48 | >10 | 88.7 | |||

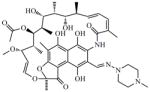

RMP (Rifampicin) |

822.95 | 6.04 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.07 | 2.6 | 113 | ||

PA-824 (nitroimidazole) |

359.26 | 2.62 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 4.9 | >128 |

Calculated ClogP by ChemDraw version 12.0, GAS = Glycerol-alanine-salts media; GAST = Iron deficient glycerol-alanine-salts with Tween 80 media; 7H12 = 7H9 broth base media with BSA, casein hydrolysate, catalase, palmitic acid; LORA = Low oxygen recover assay; VERO = African green monkey kidney cell line; RLM = Rat liver microsomes, HLM = Human liver microsomes. Values reported are the average of three individual measurements.

SAR analysis based on the whole cell assay readout indicated that 3,4-dichloro analog (7) had diminished activity (MIC’s of 9 – 14 μM) when compared to the 4-chloro (6, 0.5 μM) and 3-fluoro analogs (8, ~0.3 μM). There appeared to be a slight preference for para-substitution in terms of potency (MIC = 2.8 μM for ortho- vs. 1.2 μM for meta- vs. 0.5 μM for para-methoxy analog in the GAS assay media). Comparison of the imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine analog (10) to the corresponding imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine analog (3) indicated that the additional nitrogen in the heterocyclic core was well tolerated (sub-micomolar potency) although VERO toxicity (IC50 = 89 μM) was noted. Compounds 1 and 10 were re-screened in the presence of 4% BSA (bovine serum albumin) and 10% FBS (fetal equine serum) and their MIC’s were found to shift less than two fold by ATP and MABA readouts (see supporting information) indicating that protein binding is not a problem.

Encouraged that six of the ten analogs tested had sub-micromolar MIC values against the H37Rv Mtb strain, we next screened compounds 1 and 10 against a panel of single drug resistant strains (Table 2) against controls rifampicin (RIF) and isoniazid (INH), and then three of the more promising compounds (1, 3, 8) against a panel of MDR and XDR clinical strains (Table 2). The difference in potencies of these compounds against the clinical strains may be due to the difference in growth media where growth inhibition for clinical strains was tested in media containing glucose as well as glycerol as carbon source, as well as the fact that many clinical strains exhibit poor growth in vitro since they are not adapted to laboratory conditions and media which may affect their apparent susceptibility to certain inhibitors.

Table 2.

Potency of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines (1, 3, 8) and imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine (10) against single drug resistant strains, MDR-TB and XDR-TB stains (MIC90 in μM).

| Strains resistance to drugs: | Control/Compound ID | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMP | INH | 1 | 3 | 8 | 10 | |

| Rifampicin | >1 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 1.49 | ||

| Isoniazid | 0.01 | >8 | 0.33 | 5.84 | ||

| Kanamycin | 0.02 | 0.43 | 1.07 | 1.02 | ||

| Streptomycin | 0.02 | 0.23 | 1.02 | 5.84 | ||

| MDR-HRESP | 2.24 | 1.01 | 0.26 | |||

| MDR-HREZSP | 1.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |||

| MDR-HCPTh | 1.12 | 0.13 | 0.26 | |||

| MDR-HREKP | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.26 | |||

| MDR-HRERb* | 0.14 | ≤0.03 | 0.13 | |||

| MDR-HRERb* | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.34 | |||

| MDR-HRERb* | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.26 | |||

| MDR-HREZSKPTh | 0.07 | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | |||

| MDR-HREZRbTh | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |||

| XDR-HRESPOCTh | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | |||

| XDR-HREPKOTh | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |||

| XDR-HRESPO | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |||

Abbreviations: H=Isoniazid, R=Rifampicin, E=Ethambutol, Z=Pyrazinamide, S=Streptomycin, C=Cycloserine, Th=Ethionamide, K=Kanamycin, P=p-aminosalicylic acid, Rb=Rifabutin, Th=Thioacetazone, O=Ofloxacin.

Different clinical strains.20 Values reported are the average of three individual measurements.

The excellent activity found when these imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine agents were tested against the drug resistant strains compared favorably to the published MIC values of the nitroimidazole clinical candidate PA-82419 (MICs against MDR-TB from 0.03 to 0.25 μg/mL or 0.08 to 0.7 μM, comparatively). Furthermore, the improved, and indeed outstanding, potency of these agents against the various drug resistant strains suggests that they inhibit a novel target. Selectivity screening against various non-tubercular mycobacteria revealed that compounds 1 and 10 are also inhibitors of M. avium, M. bovis BCG and M. kansasii but not inhibitors of M. smegmatis, M. abscessus, M. chelonae and M. marinum (Table 3). This unusual selectivity prompted us to further screen compounds 1, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 10 against a panel of representative non-mycobacterial organisms. Compounds 1, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 10 were all found to be inactive against the Gram positive strain of Staphylococcus aureus (MIC >128 μM), the Gram negative strain of Escherichia coli (MIC >128 μM), and the fungus, Candida albicans (MIC >128 μM) further suggesting a mycobacterium specific target of these agents.

Table 3.

Non-tubercular mycobacteria activity and selectivity of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine (1) and imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine (10) (MIC90 in μM).

| Compound ID | TB-H37Rv | M. abscessus | M. chelonae | M. marinum | M. avium | M. kansasii | M. bovis BCG | M. smegmatis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.07 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 0.33 | > 50 |

| 10 | 5.94 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 2.78 | > 50 |

| RMP | 0.05 | 162.3 | 150.00 | < 0.78 | < 0.78 | < 0.78 | < 0.78 | 162.3 |

Values reported are the average of three individual measurements.

The in vivo pharmacokinetics (PK) of compounds 1, 3, 4 and 6 were evaluated in Sprague Dawley rats by oral (PO) and intravenous (IV) routes of administration at 10 and 1 mg/kg dosing levels, respectively (Table 4). Compound 4 had moderate in vitro rat microsomal stability (69% metabolized, t1/2 = 19 min) and also displayed promising PK by having the lowest in vivo clearance (28 mL/min/kg, t1/2 = 28 min by IV). The aqueous solubility for compounds 1, 3, 4 and 6 were measured at 181, 149, 148, 25 μM, respectively in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4. Additional in vivo ADME properties including terminal half life (t1/2β), the area under the curve (AUC), the volume of distribution (Vd) and volume of distribution at steady state (Vdss) for compounds 1, 3, 4, and 6 can be found in the supporting information section. Encouraged by the potency, PK and favorable oral bioavailability of these imdazo[1,2-a]pyridine agents we intend to evaluate various analogs in vivo by the murine Gamma Knock-out (GKO) infection model and the results will be reported in due course.

Table 4.

In vivo PK evaluation of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines.

| Compound ID | PO Cmax (ng/mL) | PO Tmax (hr) | IV t1/2 (hr) | IV clearance (mL/min/kg) | %F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3012 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 91 | 76 |

| 3 | 3140 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 43 | 43 |

| 4 | 5741 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 28 | 50 |

| 6 | 1995 | 0.31 | 0.4 | 51 | 49 |

Values reported are the average of three individual measurements.

Finally, curious as to the mechanism of action of these agents, we performed transcriptional profiling experiments of M. tuberculosis treated with compound 1 and comparison to the existing database of drug-induced transcriptional profiles indicated that this compound inhibited an aspect of energy generation in the cell (see supporting information). Thus, compound 1 resulted in up-regulation of the cytochrome bd oxidase which is the high oxygen-affinity respiratory enzyme21 observed to be up-regulated during oxygen restriction as well as inhibition of respiration by agents such as cyanide, sodium azide, the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) and the nitric oxide-releasing pro-drug PA-824.22 In addition, this compound up-regulated the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase which plays an important role in modulating carbon flow during cellular energy restriction23 and has previously been observed to be up-regulated by stresses such as hypoxia, sodium azide, valinomycin, nigericin, carbonyl cyanide rn-chlorophenylhydrazone, cyanide, PA-824, and the ATP inhibitor dicyclohexylcarboxydiimide, that limit energy generation through respiration.22

All the data suggest we have discovered a class of compounds with promising attributes of synthetic accessibility, no redox active moieties,19 impressive potency and selectivity towards replicating, MDR and XDR Mtb strains. This class has good in vivo ADME properties that potentially can be improved through further analog generation. Additionally, compound 1 appears to act by a novel mechanism of action based on transcriptional profiles to known anti-TB agents. With new anti-TB agents desperately needed we offer the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine class as a potential therapeutic for further development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID and by Grant 2R01AI054193 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and in part by intermediates provided from Dow AgroSciences. We would like to thank the University of Notre Dame, especially the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility (Bill Boggess, Michelle Joyce, Nonka Sevova), which is supported by the grant CHE-0741793 from the NIH. We thank Prof. Jennifer DuBois and Dr. Jed Fisher for profound scientific discussions. The excellent technical assistance of Baojie Wan and Yuehong Wang with anti-TB assays at UIC is greatly appreciated. Finally, we wish to thank Gail Cassell and the Lilly Tuberculosis Drug Discovery Initiative for their continued support of this project.

Funding Sources: NIH AI054193, Dow AgroSciences, NSF CHE-0741793

Footnotes

Author Contributions: GCM participated in the design, performed the syntheses, drafted the manuscript and facilitated all interactions. LDM participated in the design and coordinated interactions through Dow AgroSciences. PAH facilitated microsome and PK assessment. HB performed MDR and XDR anti-TB assays and the transcriptional profiling. SC and SGF provided anti-TB and selectivity assays. MJM drafted the manuscript, participated in the design and direction of the project.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors has a conflict of interest.

Supporting Information available: Full experimental details for compounds synthesized, descriptions of assays, PK data and transcriptional profiling as well as copies of relevant NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing: WHO report 2008. WHO/HTM/TB/2008.

- 2.Sacchettini JC, Rubin EJ, Freundlich JS. Drugs versus bugs: in pursuit of the persistent predator Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:41–52. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migliori GB, De Iaco G, Besozzi G, Centis R, Cirillo DM. First tuberculosis cases in Italy resistant to all tested drugs. Eurosurveillance. 2007;12:3194. doi: 10.2807/esw.12.20.03194-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher D, Blanc L, Raviglione M. WHO policies for tuberculosis control. The Lancet. 2004;363:1911–1911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratt R, Robison V, Navin T, Bloss E. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Tuberculosis --- United States. MMWR. 2009;58:249–253. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anaflous A, Benchat N, Mimouni S, Abouricha S, Ben-Hadda T, El-Bali A, Hacht B. Armed Imidazo [1,2-a] Pyrimidines (Pyridines): Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity. Lett Drug Des & Disc. 2004;1:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasimogullari BO, Cesur Z. Fused Heterocycles: Synthesis of Some New Imidazo[1,2-a]-pyridine Derivatives. Molecules. 2004;9:894–901. doi: 10.3390/91000894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odell LR, Nilsson MT, Gising J, Lagerlund O, Muthas D, Nordqvist A, Karlen A, Larhed M. Functionalized 3-amino-imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines: A novel class of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase inhibitors. J Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:4790–4793. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lombardino JG. Preparation and New Reactions of Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines. J Org Chem. 1965;30:2403–2407. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moraski GC, Chang M, Villegas-Estrada’ A, Franzblau S, Möllmann U, Miller MJ. Structure-Activity Relationship of New Antituberculosis Agents Derived from Oxazoline and Oxazole Benzyl Esters. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:1703–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.12.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moraski GC, Franzblau SG, Miller MJ. Utilization of the Suzuki Coupling to Enhance the Antituberculosis Activity of Aryl Oxazoles. Heterocycles. 2009;80:977–988. doi: 10.3987/COM-09-S(S)69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katritzky AR, Xu Y-J, Tu H. Regiospecific Synthesis of 3-Substituted Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines, Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidines, and Imidazo[1,2-c]pyrimidine. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4935–4937. doi: 10.1021/jo026797p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Topliss JG. Utilization of operational schemes for analog synthesis in drug design. J Med Chem. 1972;15:1006–1011. doi: 10.1021/jm00280a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins L, Franzblau SG. Microplate alamar blue assay versus BACTEC 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1004–1009. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Voss JJ, Rutter K, Schroeder BG, Su H, Zhu Y, Barry CE. The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1252–1257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho SH, Warit S, Wan B, Hwang CH, Pauli GF, Franzblau SG. Low-oxygen-recovery assay for high-throughput screening of compounds against nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1380–1385. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00055-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falzari K, Zhou Z, Pan D, Liu H, Hongmanee P, Franzblau SG. In Vitro and In Vivo Activities of Macrolide Derivatives against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1447–1454. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1447-1454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pethe K, Sequeira PC, Agarwalla S, Rhee K, Kuhen K, Phong WY, Patel V, Beer D, Walker JR, Duraiswamy J, Jiricek J, Keller TH, Chatterjee A, Tan MP, Ujjini M, Roa SPS, Camacho L, Bifani P, Mak PA, Ma I, Barnes SW. A chemical genetic screen in Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies carbon-source-dependent growth inhibitors devoid of in vivo efficacy. Nature Commun. 2010;57:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stover CK, Warrener P, VanDevanter DR, Sherman DR, Arain TM, Langhorne MH, Anderson SW, Towell JA, Yuan Y, McMurray DN, Kreiswirth BN, Barry CE, Baker WR. A small-molecule nitroimidazopyran drug candidate for the treatment of tuberculosis. Nature. 2000;405:962–966. doi: 10.1038/35016103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeon CY, Hwang SH, Min JH, Prevots DR, Goldfeder LC, Lee H, Eum SY, Jeon DS, Kang HS, Kim JH, Kim BJ, Kim DY, Holland SM, Park SK, Cho SN, Barry CE, 3rd, Via LE. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Korea: Risk factors and treatment outcomes among patients at a tertiary referral hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:42–49. doi: 10.1086/524017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kana BD, Weinstein EA, Avarbock D, Dawes SS, Rubin H, Mizrahi V. Characterization of the cydAB-encoded cytochrome bd oxidase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 2001;24:7076–86. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7076-7086.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boshoff HI, Myers TG, Copp BR, McNeil MR, Wilson MA, Barry CE., 3rd The transcriptional responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to inhibitors of metabolism: novel insights into drug mechanisms of action. J Biol Chem. 2004;38:40174–40184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marrero J, Rhee KY, Schnappinger D, Pethe K, Ehrt S. Gluconeogenic carbon flow of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates is critical for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to establish and maintain infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2010;107:9819–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000715107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.