Abstract

Complement activation products are known to be generated in the setting of both experimental and human sepsis. C5 activation products (C5a anaphylatoxin and the membrane attack complex [MAC], C5b-9) are generated during sepsis following infusion of endotoxin or after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), which produces polymicrobial sepsis. C5a reacts with its receptors, C5aR and C5L2, in a manner that creates the “cytokine storm” and is associated with development of multiorgan failure (MOF). A number of other complications arising from the interaction of C5a with its receptors include: apoptosis of lymphoid cells, loss of innate immune functions of neutrophils (PMNs), cardiomyopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and complications associated with multiorgan failure. Neutralization of C5a in vivo or absence/blockade of C5a receptors greatly reduces the adverse events in the setting of sepsis, markedly attenuates multiorgan failure, and greatly improves survival. Regarding the possible role of C5b-9 in sepsis, the literature is conflicting, some studies suggesting that C5b-9 is protective while other studies suggest the contrary. Clearly, in human sepsis, C5a and its receptors may be logical targets for interception.

Keywords: C5a, C5a receptors, polymicrobial sepsis, cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis in humans is a complex and challenging clinical problem in terms of both diagnosis and treatment. In North America, there are about 600,000 cases per year, with a mortality rate that currently approximates 30%. Since most septic patients are in intensive care units and are often mechanically ventilated, the cost of treating such individuals is extraordinary (1,2). Improvements in fluid resuscitation and in artificial ventilation have significantly improved outcomes, but reducing mortality rates substantially below the current rates has been a daunting challenge. To date, the only FDA approved drug is recombinant activated human protein C (APC), which is an anticoagulant but, like the statins, may have multiple other activities, such as anti-inflammatory effects that could explain the ability of APC to improve survival, albeit modestly. The ability of APC to improve survival in sepsis is limited (survival is only improved by about 6%) (3). In sum, very few, if any new drugs have been developed that appreciably improve the clinical outcomes in sepsis.

In this report we will focus on data indicating that robust activation of complement is occurring during sepsis in humans and animals. Because of a growing body of data suggesting that C5a interacting with its receptors (C5aR, C5L2) seems to be linked to many of the adverse outcomes of sepsis, we will briefly review the structures of C5a and its receptors, the consequences of C5a interacting with these receptors to bring about adverse outcomes, and the unresolved question of whether the other major activation product of C5, C5b-9 (MAC), plays a significant role in the outcomes of sepsis.

C5a

Human C5a is a 74 amino acid glycosylated peptide with anti-parallel α-helical structures that are crosslinked by disulfide bands, making the molecule quite stable, especially in the presence of oxidants. C5a is released from the N terminal region of the α chain of C5. Such release can occur by the C5 convertases (C3b2•Bb or C4b•C2a•C3b) which cleave C5 into C5a + C5b. C5b interacts with C6, C7, C8 and C9 to form C5b-9 (MAC). It has also been established that C5a can also be released from C5 through the actions of neutral proteases derived from PMNs or lung macrophages (4). In addition, thrombin (factor IIa) is also effective in causing C5a generation in the presence of C5 (5). C5a is a potent proinflammatory peptide with a variety of biological effects (e.g. increasing vascular permeability and inducing smooth muscle contraction, inducing chemotaxis of PMNs, monocytes and other cell types) (reviewed, 6,7). In a variety of biological systems, neutralization of C5a or absence of its receptor, C5aR, dramatically reduces the inflammatory response (as seen in acute lung injury (8) and in organs following ischemia/reperfusion injury (9), and in experimental models of rheumatoid arthritis) (8).

Structures and Functions of C5aR and C5L2 in Sepsis

These receptors are typical seven-membrane spanning receptors situated on PMNs and macrophages but also on a variety of other cell types (endothelial cells, alveolar epithelial cells, Kupffer cells, etc.). C5aR is a 45 kDa G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that interacts with C5a with very high binding affinity and, to a lesser extent, with C5a des Arg. Signaling of C5aR occurs via MAPKs (p38, ERK1/2, JNK1/2), although the role of each MAPK in various signal transduction responses varies with the cell and with the agonist. There seems to be a consensus that in PMNs the bulk of MAPK signaling involves RAS, RAF-1, MEK1 and ERK1/2, leading to NFκB activation, with cytokine/chemokine production and activation of NADPH oxidase (reviewed, 10). PMNs are especially enriched in C5aR, containing around 60,000 high affinity (e.g. 10 nM) binding sites. After CLP in rats and mice, whole organ extracts (lung, liver, thymus, kidneys, heart) show upregulation of C5aR, which may be linked to these organs being put at risk of injury or failure during sepsis.

While C5L2 has a molecular weight similar to C5aR, it has three dramatic differences when compared to C5aR: 1) because of a mutation in the DRY region of the third intracellular loop, agonist engagement of C5L2 does not cause an intracellular Ca2+ transient (11); 2) the chief agonists for C5L2 appear to be C5a as well as C5a des Arg and, perhaps, C3a as well as C3a des Arg (12), although the ability of C3a and C3a des Arg to bind to C5L2 and activate cells is a matter of controversy (12–16); 3) finally, in contrast to C5aR, in the “resting” PMN, the bulk of C5L2 appears to be in the cytosol, present in a granular pattern (15,16). If the main locale of C5L2 in the non-stimulated PMN is truly in the cytosol, then it is unclear how the agonists for C5L2 can gain cytosolic access to activate intracellular C5L2. Signaling pathways involving C5L2 are also a matter of controversy based on the use of KO mice (13,14,17). It has been suggested that C5L2 is a “default receptor”, competing with C5aR for C5a binding that results in no measureable functional outcome (11). However, the biological function of C5L2, whether simply to compete with C5aR for C5a binding or whether C5a ligation to C5L2 results in proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory outcomes is quite unsettled. When human neutrophils were activated with C5a, the expected activation (phosphorylation) of ERK1/2 was found (10). In the copresence of blocking mAb to human C5L2, this activation process was intensified, suggesting that, ordinarily, C5L2 negatively regulates the activation of ERK1/2 (18). In contrast, the Toronto group reported that LPS or C5a activation of neutrophils resulted in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in Wt cells but failed to occur in C5L2−/− cells (13). In addition, the Gerard group (14) reported that C5L2−/− mice had intensified injury after intrapulmonary deposition of IgG immune complexes, while the Toronto group, using the same model of lung injury, reported greatly reduced intensity of lung injury in C5L2−/− mice (13). It is not currently possible to reconcile these divergent sets of data. In C5L2−/− mice following CLP, there were substantial increases in serum levels of IL-6 when compared to CLP wild type mice (17) which might be consistent with the idea that, in the absence of C5L2, C5aR can function in an unregulated manner. As related to CLP-induced sepsis in mice, recent data suggest that C5L2 acts collaboratively in conjunction with C5aR to enhance the cytokine storm as well as increased mortality (see below).

Roles of C5a, C5aR and C5L2 in Experimental Sepsis

A) C5a

There is accumulating evidence that in subhuman primate models of sepsis (infusion of live E. coli into monkeys) C5a blockade (by rabbit polyclonal antibody) reduced several metabolic parameters of sepsis and caused diminished evidence of the adult respiratory distress syndrome, although the small group of animals did not permit any statistically significant differences between the groups treated with C5a neutralizing antibody versus control IgG (19). In rats or mice with CLP, both rabbit polyclonal neutralizing antibodies and mouse monoclonal antibodies that neutralized C5a were highly effective in attenuating the parameters of sepsis (clinical symptoms, evidence of MOF, consumptive coagulopathy, innate immune functions, apoptosis, etc.), resulting in greatly improved survival (20,21). When administration of mAbs was delayed for as long as 12 hr after CLP, there was still substantially improved survival, suggesting that in this experimental model there is a significant period of time after the onset of sepsis during which intervention to block C5a is effective (22).

It seems clear that excessive C5a generated during sepsis has harmful effects, as described above. Some of the most clear-cut harmful effects of C5a on PMNs in the setting of sepsis are: defective chemotaxis not only to C5a but to structurally unrelated peptides such as N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (N-fMLP); defective respiratory burst function (O2 consumption and generation of O2· and H2O2) in PMNs stimulated with phorbol ester; defective phagocytosis and defective binding of C5a to blood PMNs but not defective binding of N-fMLP (23,24). These data suggest that global defects develop in innate immune functions of PMNs in the setting of sepsis. In vivo infusion of neutralizing antibodies to rat C5a in CLP rats markedly blocks development of all of these defects in PMNs during sepsis (Figure 1).

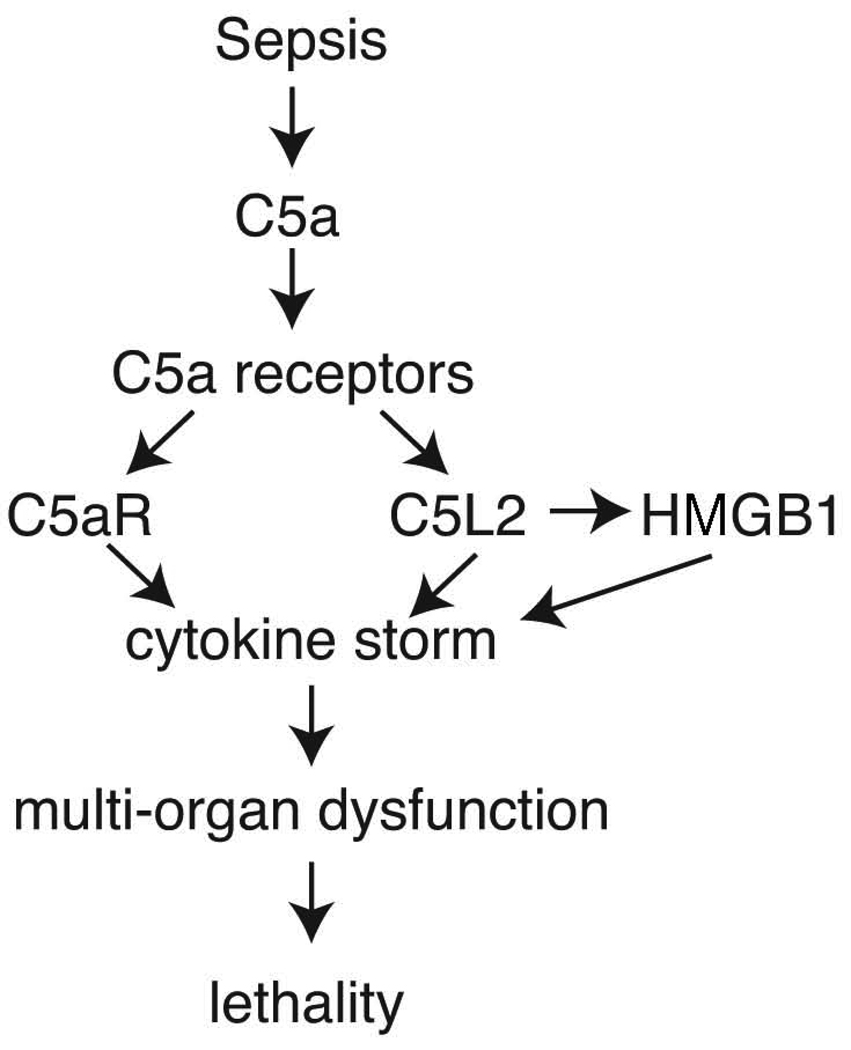

Figure 1. Sequence of Sepsis, Complement Activation and Lethality.

Roles of C5a interacting with its receptors after onset of sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture in rodents. The downstream effects are the “cytokine storm”, together with production of HMGB1 from macrophages which accentuates the cytokine storm. Ultimately, these events lead to multiorgan dysfunction and lethality.

B) C5aR and C5L2

Experimental studies in rats or mice with CLP suggest a dynamic balance between C5aR and C5L2 on blood PMNs and in organs. As suggested above, as sepsis progresses binding sits on PMNs are markedly reduced, as the C5a-C5aR complexes on cell surfaces are internalized into PMNs (25). The loss of such binding sites correlates with survival: the greater the loss of binding sites, the worse is the prognosis for survival. When organs (liver, thymus, lungs, kidneys, heart) were evaluated for mRNA for C5aR and for C5L2, in general there was evidence of upregulation of mRNAs for these receptors, suggesting that perhaps the organs were being put at risk for injury in the presence of circulating C5a. Immunochemical staining for C5aR in organs during the early phases of sepsis indicated the concomitant upregulation of protein for C5aR (25,26). In the case of thymocytes obtained from CLP rats, we found that as early as 3 hr after CLP C5a binding sites on thymocytes were increased. This was associated with preceding upregulation of C5aR protein on the thymocytes (27). Such data suggest in CLP-induced sepsis that binding sites for C5a in organs can be extremely rapidly upregulated, followed by down-regulation as internalization of C5a•C5a receptor complexes occurs (25).

Our group has recently provided a comprehensive report on the role of C5aR and C5L2 in the setting of CLP in mice, using C5a receptor knockout mice, neutralizing antibodies to C5a receptors, or C5a blockade (20,21,25,27). Such studies indicate that both C5aR and C5L2 contribute to the cytokine storm, multiorgan failure and lethality. It appeared that >75% suppression of the cytokine storm occured in the absence of either C5aR or C5L2, suggesting that the appearance of cytokines/chemokines in plasma after CLP occurs via sequential engagement of both receptors (20). Another finding in this study was that high mobility globulin β1, (HMGB1), which induces release of multiple cytokines and chemokines from macrophages, was produced by LPS-stimulated macrophages via engagement of C5L2 but not C5aR (20). HMGB1 is known to be important for its role in CLP-induced sepsis (28).

Assuming that C3a des Arg, C5a and C5a des Arg are ligands for C5L2 (11–13,29), the issue arises about the role of C3a in development of CLP-induced sepsis. The most direct data bearing on this question is the use of C3−/− mice in which it was shown that these mice are more susceptible to the lethal effects of CLP (30,31). Accordingly, it is not clear to what extent C3a/C3a des Arg and C3aR play roles in events following CLP. The reason for increased susceptibility of C3−/− to the lethal effects of sepsis seems likely related to the inability to generate opsonic factors such as C3b and iC3b. C3−/− mice 24 hr after CLP had much higher levels of blood CFUs compared to Wt mice (30,31).

Role of C5b-9 in CLP-induced Sepsis

Since C5b-9 is known to have lytic activity for Gram negative bacteria, and because C5b-9 is generated in conditions associated with tissue injury (such as ischemia/reperfusion injury) (9), the role of C5b-9 in CLP-induced sepsis is important to understand since one strategy to block C5a generation during sepsis would be to use a C5-depleting mAb, such as that approved for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinemia which is due to a defect in one of the complement regulatory proteins (32). The role of C5b-9 in the setting of CLP-induced sepsis is unclear. Depletion of C5 in CLP mice using an antibody to C5 produced protective effects, as did absence of C6 in CLP rats (33, although to what extent this could be explained by absence of either C5a or C5b-9 remains unclear. Since C6-deficient mice are not available, we recently used a protocol that depletes C6 using a polyclonal antibody to mouse C6 (30). This resulted in ≥80% reduction in CH50 levels in mouse serum. Under such conditions, C6-depleted mice had blood CFU levels 24 hr after CLP that were approximately 10 times higher than CFU levels in CLP mice that were C6 intact, suggesting that defective production of C5b-9 might be related to reduced ability to contain bacteremia in these C6-depleted mice. Obviously, it is not clear to what extent C5b-9 is harmful or protective in the setting of CLP-induced sepsis.

C5a and Apoptosis in Sepsis

It has been well documented that sepsis in humans and in rodents induces a state of immunosuppression that is related to an early loss of both B and T cells in lymphoid tissues and in blood (27,34,35). Lymphoid cell loss appears to be due to induction of apoptosis of these cells, likely via engagement of both the intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (TNFα, Fas ligand) pathways of apoptosis. Our own studies have focused on apoptosis of thymocytes in CLP rats. Sepsis induced a striking loss of mass of the thymus (>50%) in the first few days after CLP. C5aR content on thymocytes was found to rise rapidly after CLP, and increased binding of C5a to thymocytes could be found as early as 3 hr after CLP. Furthermore, in vitro exposure of C5a to CLP thymocytes induced apoptosis in vitro, featuring activation of caspases 3, 6 and 9. The use of neutralizing antibody to C5a given at the time of CLP also preserved thymic mass and largely abolished evidence of caspase activation in and apoptosis of thymocytes (27,35). These studies suggest that CLP-induces a rapid and early response (upregulated) of C5aR on lymphoid cells.

When sepsis in both humans and animals becomes progressive, septic shock usually ensues. We reasoned that such outcomes might be related to inadequate reserves of epinephrine and norepinephrine released from the adrenal medulla. In a recent study of CLP in mice, we found extensive apoptosis of adrenal medullary cells 24 hr after CLP. When dual blockade of both C5aR and C5L2 was accomplished using antibodies, the degree of apoptosis of adrenal medullary cells was greatly diminished, as assessed by the TUNEL assay (36). Using the PC12 cell line derived from a human pheochromocytoma, addition of C5a totally suppressed the release of norepinephrine and dopamine (36). This was shown to be coincidental with the fact that C5a caused apoptosis of the PC12 cells. Such data suggest that C5a released after CLP-induced sepsis may lead to adrenal medullary cell apoptosis, predisposing animals to the development of septic shock.

C5a Effects on the Heart During Sepsis

Development of reversible cardiac dysfunction (biventricular dilation, increased cardiac output followed by falling output, decreased systemic vascular resistance, etc.) commonly occurs as sepsis advances. “Septic cardiomyopathy” has been defined by in vitro dysfunction of cardiomyocytes (CMs). When CMs were isolated from septic rodents, they exhibited defective contractility as well as defective relaxation (37). Such functional defects would imply that the heart has lost its resilience and ability to adjust during sepsis in order to maintain sufficient cardiac output and maintain adequate blood pressure for organ perfusion. Furthermore, when CMs from normal rats were incubated in vitro with C5a, these cells developed dramatic defects in spontaneous contractility and relaxation, associated with the fact that normal CMs contain constitutive C5aR on their cell surfaces (37). When C5a was blocked in vivo (with neutralizing antibody) at the time of CLP, CMs obtained from these animals after CLP showed full contractility and relaxation functions, indicating that C5a produced during CLP may directly cause defects in cardiac function. “Cardiosuppressive cytokines” (IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, etc.) have been described in plasma from septic humans (38,39). The definition of such cytokines was based on their ability to cause contractile defects in normal CMs. Whether this finding can be linked to the effects of C5a on CMs remains to be seen.

CONCLUSIONS

It has been known for some time that septic humans demonstrate C5a in their plasma (10–100 nM), that there are corresponding falls in serum complement hemolytic activity (CH50), and that under these conditions defective innate immune functions occur in blood PMNs (23). Similar defects can be mimicked by in vitro exposure of normal blood PMNs to C5a (22,24). In an accumulating body of evidence, polymicrobial sepsis induced in rodents by CLP results in a series of cell and organ dysfunctions that can be linked to C5a and its receptors, C5aR and C5L2. Use of blocking antibodies to C5a or to C5a receptors or use of synthetic compounds that block C5a receptors dramatically attenuate most of the complications of sepsis (Figures 1, 2). These data suggest that in humans with sepsis consideration should be given to strategy designed to either block C5a or its receptors.

Figure 2. C5a, C5aR and Systemic Derangement in Sepsis.

C5a generated during sepsis interacts with its receptors, C5aR and C5L2. This leads to four major complications: defects in innate immune responses of neutrophils, conversion of endothelial cells to a hyperinflammatory state with increased expression of ICAM-1 and tissue factor, lymphoid cell apoptosis with ensuing immunosuppression, and consumptive coagulopathy. All of these complications can be blocked by in vitro blockade of C5a or its two receptors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by NIH grant GM-61656.

Footnotes

The author has no potential or competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dombrovskiy VY, Martin AA, Sunderram J, Paz HL. Rapid increase in hospitalization and mortality rates for severe sepsis in the United States: a trend analysis from 1993 to 2003. Crit Care Med. 2007 May;35(5):1244–1250. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000261890.41311.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001 Jul;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, LaRosa SP, Dhainaut JF, Lopez-Rodriguez A, Steingrub JS, Garber GE, Helterbrand JD, Ely EW, Fisher CJ., Jr Recombinant human protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study group. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001 Mar 8;344(10):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huber-Lang M, Younkin EM, Sarma JV, Riedemann N, McGuire SR, Lu KT, Kunkel R, Younger JG, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. Generation of C5a by phagocytic cells. Am J Pathol. 2002 Nov;161(5):1849–1859. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64461-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Rittirsch D, Neff TA, McGuire SR, Lambris JD, Warner RL, Flierl MA, Hoesel LM, Gebhard F, Younger JG, Drouin SM, Wetsel RA, Ward PA. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006 Jun;12(6):682–687. doi: 10.1038/nm1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo RF, Ward PA. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otto M, Hawlisch H, Monk PN, Müller M, Klos A, Karp CL, Köhl J. C5a mutants are potent antagonists of the C5a receptor (CD88) and of C5L2: position 69 is the locus that determines agonism or antagonism. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jan 2;279(1):142–151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo RF, Ward PA. Mediators and regulation of neutrophil accumulation in inflammatory responses in lung: insights from the IgG immune complex model. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002 Aug 1;33(3):303–310. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00823-7. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dirksen MT, Laarman GJ, Simoons ML, Duncker DJ. Reperfusion injury in humans: a review of clinical trials on reperfusion injury inhibitory strategies. Cardiovasc Res. 2007 Jun 1;74(3):343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.01.014. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Whitfeld PL, Mackay CR. Receptors for complement C5a. The importance of C5aR and the enigmatic role of C5L2. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008 Feb;86(2):153–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okinaga S, Slattery D, Humbles A, Zsengeller Z, Morteau O, Kinrade MB, Brodbeck RM, Krause JE, Choe HR, Gerard NP, Gerard C. C5L2, a nonsignaling C5a binding protein. Biochemistry. 2003 Aug 12;42(31):9406–9415. doi: 10.1021/bi034489v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalant D, MacLaren R, Cui W, Samanta R, Monk PN, Laporte SA, Cianflone K. C5L2 is a functional receptor for acylation-stimulating protein. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jun 24;280(25):23936–23944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen NJ, Mirtsos C, Suh D, Lu YC, Lin WJ, McKerlie C, Lee T, Baribault H, Tian H, Yeh WC. C5L2 is critical for the biological activities of the anaphylatoxins C5a and C3a. Nature. 2007 Mar 8;446(7132):203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature05559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerard NP, Lu B, Liu P, Craig S, Fujiwara Y, Okinaga S, Gerard C. An anti-inflammatory function for the complement anaphylatoxin C5a-binding protein, C5L2. J Biol Chem. 2005 Dec 2;280(48):39677–39680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johswich K, Martin M, Thalmann J, Rheinheimer C, Monk PN, Klos A. Ligand specificity of the anaphylatoxin C5L2 receptor and its regulation on myeloid and epithelial cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2006 Dec 22;281(51):39088–39095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scola AM, Johswich KO, Morgan BP, Klos A, Monk PN. The human complement fragment receptor, C5L2, is a recycling decoy receptor. Mol Immunol. 2009 Mar;46(6):1149–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao H, Neff TA, Guo RF, Speyer CL, Sarma JV, Tomlins S, Man Y, Riedemann NC, Hoesel LM, Younkin E, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. Evidence for a functional role of the second C5a receptor C5L2. FASEB J. 2005 Jun;19(8):1003–1005. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3424fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bamberg CE, Mackay CR, Lee H, Zahra D, Jackson J, Lim YS, Whitfeld PL, Craig S, Corsini E, Lu B, Gerard C, Gerard NP. The C5a receptor (C5aR) C5L2 is a modulator of C5aR-mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2010 Mar 5;285(10):7633–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens JH, O'Hanley P, Shapiro JM, Mihm FG, Satoh PS, Collins JA, Raffin TA. Effects of anti-C5a antibodies on the adult respiratory distress syndrome in septic primates. J Clin Invest. 1986 Jun;77(6):1812–1816. doi: 10.1172/JCI112506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Nadeau BA, Day DE, Huber-Lang M, Mackay CR, Zetoune FS, Gerard NP, Cianflone K, Köhl J, Gerard C, Sarma JV, Ward PA. Functional roles for C5a receptors in sepsis. Nat Med. 2008 May;14(5):551–557. doi: 10.1038/nm1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czermak BJ, Sarma V, Pierson CL, Warner RL, Huber-Lang M, Bless NM, Schmal H, Friedl HP, Ward PA. Protective effects of C5a blockade in sepsis. Nat Med. 1999 Jul;5(7):788–792. doi: 10.1038/10512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber-Lang MS, Sarma JV, McGuire SR, Lu KT, Guo RF, Padgaonkar VA, Younkin EM, Laudes IJ, Riedemann NC, Younger JG, Ward PA. Protective effects of anti-C5a peptide antibodies in experimental sepsis. FASEB J. 2001 Mar;15(3):568–570. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0653fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomkin JS, Jenkins MK, Nelson RD, Chenoweth D, Simmons RL. Neutrophil dysfunction in sepsis. II. Evidence for the role of complement activation products in cellular deactivation. Surgery. 1981 Aug;90(2):319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber-Lang MS, Younkin EM, Sarma JV, McGuire SR, Lu KT, Guo RF, Padgaonkar VA, Curnutte JT, Erickson R, Ward PA. Complement-induced impairment of innate immunity during sepsis. J Immunol. 2002 Sep 5;169(6):3223–3231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo RF, Riedemann NC, Bernacki KD, Sarma VJ, Laudes IJ, Reuben JS, Younkin EM, Neff TA, Paulauskis JD, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. Neutrophil C5a receptor and the outcome in a rat model of sepsis. FASEB J. 2003 Oct;17(13):1889–1891. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0009fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Neff TA, Laudes IJ, Keller KA, Sarma VJ, Markiewski MM, Mastellos D, Strey CW, Pierson CL, Lambris JD, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. Increased C5a receptor expression in sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2002 Jul;110(1):101–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI15409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Laudes IJ, Keller K, Sarma VJ, Padgaonkar V, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. C5a receptor and thymocyte apoptosis in sepsis. FASEB J. 2002 Jun;16(8):887–888. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0033fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Wang H, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. The cytokine activity of HMGB1. J Leukoc Biol. 2005 Jul;78(1):1–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104648. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalant D, Cain SA, Maslowska M, Sniderman AD, Cianflone K, Monk PN. The chemoattractant receptor-like protein C5L2 binds the C3a des-Arg77/acylation-stimulating protein. J Biol Chem. 2003 Mar 28;278(13):11123–11129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206169200. Erratum in: J Biol Chem. 2004 Jan 2;279(1):820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Nadeau BA, Day DE, Zetoune FS, Sarma JV, Huber-Lang MS, Ward PA. Functions of the complement components C3 and C5 during sepsis. FASEB J. 2008 Oct;22(10):3483–3490. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prodeus AP, Zhou X, Maurer M, Galli SJ, Carroll MC. Impaired mast cell-dependent natural immunity in complement C3-deficient mice. Nature. 1997 Nov 13;390(6656):172–175. doi: 10.1038/36586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker CJ, Kar S, Kirkpatrick P. Eculizumab. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007 Jul;6(7):515–516. doi: 10.1038/nrd2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buras JA, Rice L, Orlow D, Pavlides S, Reenstra WR, Ceonzo K, Stahl GL. Inhibition of C5 or absence of C6 protects from sepsis mortality. Immunobiology. 2004;209(8):629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotchkiss RS, Nicholson DW. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006 Nov;6(11):813–822. doi: 10.1038/nri1943. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward PA. Sepsis, apoptosis and complement. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008 Dec 1;76(11):1383–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Chen AJ, Nadeau BA, Day DE, Sarma JV, Huber-Lang MS, Ward PA. The complement anaphylatoxin C5a induces apoptosis in adrenomedullary cells during experimental sepsis. PLoS One. 2008 Jul 2;3(7):e2560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niederbichler AD, Hoesel LM, Westfall MV, Gao H, Ipaktchi KR, Sun L, Zetoune FS, Su GL, Arbabi S, Sarma JV, Wang SC, Hemmila MR, Ward PA. An essential role for complement C5a in the pathogenesis of septic cardiac dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2006 Jan 23;203(1):53–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joulin O, Petillot P, Labalette M, Lancel S, Neviere R. Cytokine profile of human septic shock serum inducing cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction. Physiol Res. 2007;56:291–297. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cain BS, Meldrum DR, Dinarello CA, Meng X, Joo KS, Banerjee A, Harken AH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta synergistically depress human myocardial function. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1309–1318. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]