Abstract

Objectives

We examined the associations of oral health literacy (OHL) with oral health status (OHS) and dental neglect (DN), and explored whether self-efficacy (SE) mediated or modified these associations, among a sample of female clients of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

Methods

We used interview data that were collected from 1280 female WIC clients as part of the Carolina Oral Health Literacy (COHL) Project between 2007 and 2009. OHL was measured with a validated word recognition test (REALD-30) and oral health status with the self-reported NHANES item. Analyses relied upon descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate methods.

Results

Less than one-third of participants rated their oral health as very good or excellent. Higher OHL was associated with better oral health status (multivariate PR=1.29; 95% CL=1.08, 1.54, for 10-unit REALD increase). OHL was not correlated with DN but SE showed a strong negative correlation with DN. SE remained significantly associated with DN in a fully-adjusted model that included OHL.

Conclusions

Increased OHL was associated with better OHS but not DN. Self-efficacy was a strong correlate of DN and may mediate the effects of literacy on oral health status.

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

According to the most recent National Assessment of Adult Literacy Survey, nearly half (43%) of adults in the United States (U.S.) are at risk for low literacy.1 Because written health information is frequently provided at above the 10th grade level, approximately 90 million adult Americans with low health literacy skills struggle to understand fundamental health information including consent forms, verbal instructions, and drug labels.2

“Health literacy” refers to the ability to perform basic reading and numerical tasks necessary for navigating through the health care environment and acting on health care information.3 Health literacy is defined in Healthy People 2010 as: “The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions”.4

Individuals with low health literacy skills often have poorer health knowledge and health status, unhealthy behaviors, less utilization of preventive services, higher rate of hospitalizations, increased health care costs, and ultimately poorer health outcomes than those with higher literacy levels.5–11 Health literacy has been shown to function as a mediator between traditional socioeconomic factors, such as race and education, and health behaviors and health outcomes,12–14 explaining, in part, health disparities.15,16 Paasche-Orlow and Wolf proposed a conceptual model of causal pathways between health literacy and health outcomes.17 In their model, patient-level and extrinsic factors grouped as a) access and utilization of health care b) provider-patient interaction and c) self-care, mediated the effect of literacy on health outcomes. Although these pathways have yet to be validated, one recent report by Osborn et al.18 suggested that self-efficacy and self-care indeed mediate the effect of health literacy on health status. Previous investigations had not found any association between health literacy and self-efficacy.19,20

Although the body of literature linking literacy to health continues to grow, similar studies examining literacy are relatively new in dentistry. Oral health literacy (OHL) is defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic oral health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.21

The network of proximal and distal factors affecting oral health is complex and not understood completely. These factors include genetic and environmental,22 socio-demographics23–25 and personality.26–28 While OHL represents one’s ability to understand and process the relevant health information, other characteristics may modify the resulting decisions or actions. In this context, the role of oral health behaviors has been the focus of recent attention29,30 because, unlike most other factors, behaviors are amenable to change.31 The construct of self-efficacy beliefs (SE) is considered to represent an important link between health knowledge, behaviors and outcomes,32 and it correlates well with other personality characteristics related to health behaviors.33 Because SE is a significant determinant of health-related actions initiated or avoided by individuals, its consideration in the oral health context has been advocated.31,34

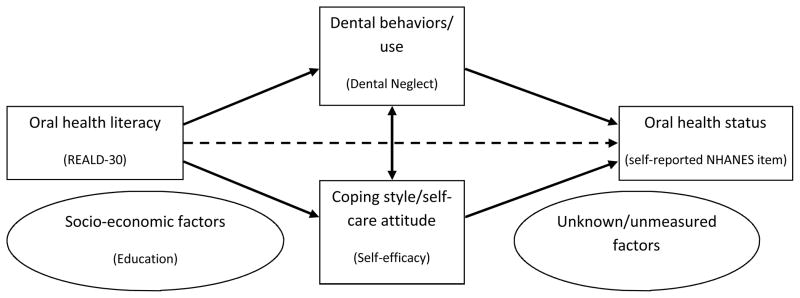

Although conceptual frameworks illustrating possible pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes or status have been developed in medicine,12,14,17 little progress has been made to develop such pathways between OHL and oral health status. Macek et al.35 recently proposed a conceptual model linking word recognition and conceptual knowledge, decision making, and communication skills with oral health outcomes. Although this does not represent an exhaustive model, we theorize that OHL likely exerts effects on avoidance of care (oral dental neglect) (Figure 1), which may or may not be mediated or modified by individual or systemic characteristics, along the lines of the Paasche-Orlow and Wolf model.17 Because the links of OHL with oral health status and dental neglect have not been examined by any previous investigation to our knowledge, we embarked upon this investigation to establish this link. Due to the absence of any data linking SE with OHL, we sought to examine this association and empirically investigate the role of SE as a mediator or modifier36 of the association between OHL and dental neglect and oral health status, without conducting any comprehensive pathway analyses. The aims of the present study were to: 1) Determine the association of OHL with oral health status and dental neglect, and 2) Explore the role of self-efficacy as a mediator or modifier of the association between literacy and oral health status.

Figure 1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Interview data from 1,405 participants were collected as part of the Carolina Oral Health Literacy (COHL) Project.37 The main goal of COHL was to examine oral health literacy and its relationship to health behaviors and health outcomes among caregivers, infants, and children enrolled in the Women, Infants and Children’s (WIC) Program in North Carolina (NC). A prospective cohort study design was developed to determine OHL levels in a population attending WIC clinics in sites selected because of the large number and diverse background of low income clients. Nine sites in seven NC counties were selected. The study was approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For the present analysis we excluded men (N=49; 3.5% of total), Asians (N=12; 0.9%), and those who did not have English as their primary language (N=79; 5.6%).

The major explanatory variable was oral health literacy (OHL) measured using a validated word recognition test, the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Dentistry (REALD-30).38 The REALD-30 scale score ranges between 0 (lowest literacy) and 30 (highest literacy). Our major outcome variables were dental neglect and self-reported oral health status.

To evaluate dental neglect we used a modified version of the previously validated Dental Neglect Scale (DNS).39–41 Participants were asked to report their agreement to six items referring to their dental behaviors, with responses ranging from “definitely not” to “definitely yes”, on a four-point Likert scale. These items included: “I keep my dental care at home”; “I received the dental care I should”; “I need dental care, but I put it off”; “I brush as well as I should”; “I control snacking between meals as well as I should” and “I consider my dental health to be important”. We computed a cumulative score ranging from 6 (least dental neglect) to 24 (most dental neglect) and estimated Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of internal consistency/reliability. Because a recent investigation42 suggested that two factors may be distinguishable within the DNS (“dental neglect” and “avoidance of care”), we conducted factor analysis (retaining Eigenvalue>1) to determine whether this was the case in our study sample. We assessed oral health status using the NHANES item: “How would you describe the condition of your mouth and teeth?” where possible responses were excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. Self-efficacy was evaluated as a potential effect mediator or modifier,43 and was measured using the 10-item General Self-Efficacy Scale (SE).44 Items in the SE were related to one’s ability to cope with general life demands. For example, “I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough” and “I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities”. The construct of SE refers to one’s coping ability across a wide range of demanding situations,44 and has been shown to have good psychometric properties across diverse populations.45 SE scores range between 10 and 40, where 10=least self-efficacy and 40=highest self-efficacy. We obtained Cronbach’s alpha for the SE scale to determine its reliability in the context of our study.

Covariates evaluated as confounders included demographic characteristics and dental use. Demographic information was collected for age, race, and educational attainment. Age was measured in years and was coded as a quintile-categorical indicator variable. Race was coded as an indicator variable with terms for White, African American (AA), American Indian or Alaskan Native (AI). Education was coded as a four-level categorical variable where 1=did not finish high school, 2=high school or General Education Diploma (GED), 3=some technical education or some college, 4=college or higher education. Dental use referred to the time since the last dental visit, and was coded as four-level categorical variable (4=<12 months, 3=12–23 months, 2=2–5 years, 1=>5 years).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics of OHL and DNS by demographic characteristics, dental use and oral health status were generated. The normality assumption for DNS, OHL, and SE scores was tested by a combined skewness and kurtosis evaluation test46 and a P<0.05 criterion. To examine the association of SE scores with OHL and DNS we used graphical methods based on local polynomial smoothing functions to illustrate the bivariate associations and corresponding 95% confidence limits (CL). To further quantify these associations we computed Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rho) for their pairwise combinations and 95% CL, using bootstrapping (1,000 repetitions). For all analyses we used the computed OHL, DNS, and SE scores with no standardization, as in previous investigations.34,35,37–41

Multivariate modeling based on log binomial regression was used to obtain prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% CL for the association of OHL with oral health status (excellent/very good versus good/fair/poor). The choice of log binomial versus traditional logistic regression was based on the fact that odds ratios tend to overestimate the PR when the outcome is common (>20%).47 Moreover, PR estimates obtained from log binomial models have a more straightforward interpretation in cross-sectional study designs.48 Race, age, education, and dental use were considered a priori confounders of the association between OHL and DNS and health status, and therefore they were included in the minimal (model A) and all subsequent analytical models. We examined SE as an effect mediator in the association between OHL and health status empirically, by adding this variable (model B) and computing a “percent change in estimate” using model A as the referent. This approach is analogous to a confounding evaluation. Effect modification by SE was evaluated in the context of statistical interaction and a P<0.1 criterion for the coefficient of an interaction term between SE and OHL. Its inclusion (model C) was also assessed with a change-in-estimate criterion of ≥10% as follows: change=[|ln(PRfull)−ln(PRreduced)|/ln(PRreduced)] × 100. The addition of the interaction term between OHL and SE was also evaluated with a likelihood ratio test (LRT X2), comparing the full (model C) and nested model (model B) and using a P<0.1 criterion. Additionally we employed a second multivariate model based on linear regression to obtain adjusted DNS score differences and 95% CL for the impact of literacy and SE on DNS. All analyses were conducted using STATA 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The demographic characteristics, dental use and oral health status of our analytical sample (N=1,280), along with the corresponding REALD-30, and DNS distribution characteristics are presented in Table 1. The racial representation for Whites, AAs and AIs was 2:2:1, and their mean age was 26.6 years (SD=6.9). Two thirds of participants had high school education or less, and less than one third rated their oral health as very good or excellent.

Table 1.

Distribution of REALD-30 and DNS scores by demographic characteristics, dental use and oral health status among the COHL study participants (n=1280).

| N* | % | REALD-30 | DNS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | |||

| Total | 1280 | 100 | 15.8 (5.3) | 16 | 11.9 (3.2) | 12 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 503 | 39.3 | 17.4(4.9) | 17 | 12.0(3.2) | 12 |

| African American | 522 | 40.8 | 15.3(5.1) | 15 | 11.9(3.2) | 12 |

| American Indian | 255 | 19.9 | 13.7(5.3) | 14 | 11.5(3.3) | 12 |

| Education | ||||||

| Did not finish high school | 306 | 23.9 | 13.0(4.8) | 13 | 11.1(3.6) | 12 |

| High school diploma or GED† | 479 | 37.4 | 15.0(4.9) | 15 | 11.9(3.1) | 12 |

| Some technical or college training | 430 | 33.6 | 18.0(4.7) | 18 | 11.8(3.1) | 12 |

| College degree or higher | 65 | 5.1 | 20.7(4.8) | 21 | 11.0(3.2) | 11 |

| Age quintiles (years) | Mean(SD) | |||||

| Q1 (range: 17.2–20.9) | 256 | 19.5(0.8) | 14.2(4.8) | 15 | 11.4(3.4) | 11 |

| Q2 (range: 20.9–23.4) | 256 | 22.1(0.7) | 15.5(5.2) | 15 | 12.1(3.2) | 12 |

| Q3 (range: 23.4–26.5) | 256 | 24.8(0.9) | 16.5(5.0) | 16 | 11.6(3.1) | 12 |

| Q4 (range: 26.5–30.9) | 256 | 28.6(1.3) | 16.3(4.8) | 16 | 12.1(3.2) | 12 |

| Q5 (range: 30.9–65.6) | 256 | 37.7(6.1) | 16.6(6.0) | 17 | 12.0(3.2) | 12 |

| Dental use (last dental visit) | ||||||

| <12 months | 727 | 57.1 | 15.8(5.2) | 16 | 10.9(3.2) | 11 |

| 12–23 months | 218 | 17.1 | 16.1(5.5) | 16 | 12.5(3.0) | 12 |

| 2–5 years | 177 | 13.9 | 15.8(5.6) | 16 | 13.3(2.6) | 13 |

| 5+ years | 151 | 11.9 | 15.4(4.7) | 15 | 13.9(2.6) | 14 |

| “How would you describe the condition of your mouth and teeth?” | ||||||

| Excellent | 118 | 9.3 | 16.1(5.6) | 17 | 9.0(2.5) | 9 |

| Very good | 258 | 20.2 | 16.8(5.3) | 17 | 10.3(2.7) | 10 |

| Good | 481 | 37.7 | 15.6(5.1) | 16 | 11.7(2.8) | 12 |

| Fair | 287 | 22.5 | 15.5(5.1) | 15 | 13.5(2.8) | 13 |

| Poor | 131 | 10.3 | 15.4(5.6) | 15 | 14.7(3.1) | 15 |

Column figures may not add up to total due to missing values;

General education diploma

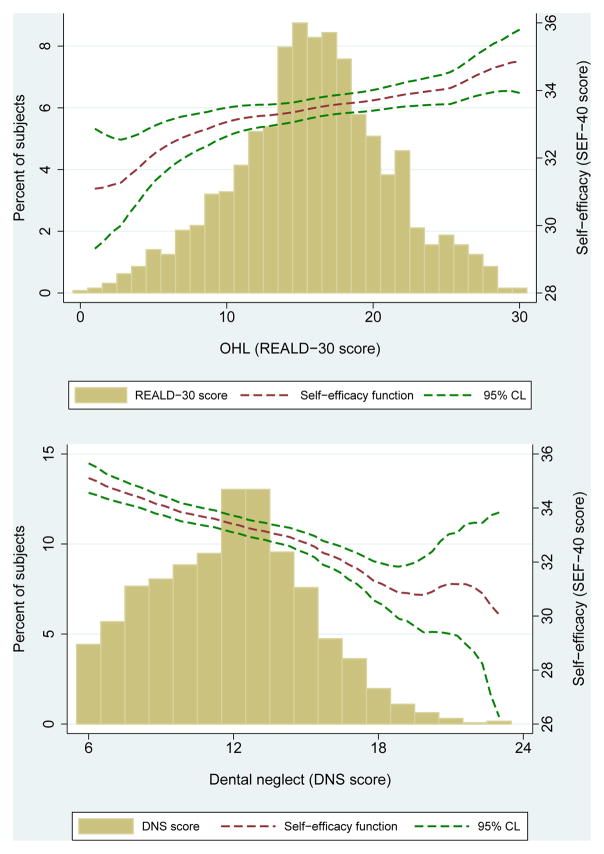

The overall distribution of REALD-30 and DNS scores is illustrated in Figure 2. OHL scores were normally distributed (X2=1.53, df=2, P>0.05) with mean=15.8 (SD=5.3), range=0–30 and DNS scores were positively skewed with mean=11.9 (SD=3.2), and range=6–23. SE scores were negatively skewed with mean=33.4 (SD=4.1), range=15–40, they were positively correlated with DNS, and did not show any important pattern of association with OHL. Factor analysis confirmed that DNS items loaded on one principal factor (Eigenvalue=1.5). Cronbach’s alpha for DNS and SE was 0.62 and 0.81 respectively. Figure 2 also illustrates the bivariate relationships of SE with OHL and DNS. The panel includes two histograms that illustrate the univariate distribution of OHL and DNS. Polynomial fit functions (red dotted lines) and 95% confidence limits (green dotted lines) of the association of SE with OHL and DNS are overlaid on these histograms. These functions indicate the corresponding SE score mean and 95% CL for each level of OHL and DNS on the supplemental right vertical axis. Pairwise Spearman’s correlation coefficients among these three measures were: rhoDNS,SE=−0.26 (95% CL=−0.31, −0.20); rhoREALD-30,SE=0.10 (95% CL=0.04, 0.15); rhoREALD-30,DNS=−0.02 (95% CL=−0.08, 0.04).

Figure 2.

Higher DNS scores were associated with worse oral health status. Marked differences were noted in OHL levels between levels of education, age, and racial groups (Table 1). Independent of race, age, education, and dental use, higher OHL was associated with better oral health status (Table 2, Model A): PR=1.03 (95% CL=1.01, 1.04), an estimate that corresponds to a 29% (95% CL=8%, 54%) increase in prevalence of excellent/very good versus good/fair/poor oral health for a 10-point increase in OHL. Inclusion of SE in the model resulted in 11% reduction in the measure of association between OHL and oral health status (Model B). Furthermore, the interaction term between OHL and SE was retained in Model C (P<0.1), and its inclusion improved the model fit significantly (X2=4.7, df=1, P<0.1).

Table 2.

Multivariate log binomial regression modeling results of self-reported oral health (binary: excellent/very good versus good/fair/poor) among the COHL study participants (n=1280).

| Model A | Model B | Model C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CL) | PR (95% CL) | PR (95% CL) | |

| REALD-30 (OHL) score* | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | 1.02(1.00, 1.04)A | 0.88 (0.78, 1.00) |

| Self-efficacy (SE) score* | . | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.05) |

| Interaction (SE* OHL) | . | . | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01)B |

| Race (referent: Whites) | |||

| African American | 0.96 (0.79, 1.16) | 0.89 (0.73, 1.07) | 0.88 (0.72, 1.06) |

| Native American | 1.22 (0.98, 1.52) | 1.18 (0.95, 1.47) | 1.18 (0.95, 1.47) |

| Age (quintiles) | 0.91 (0.85, 0.97) | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 0.91 (0.86, 0.97) |

| Education level | 1.17 (1.06, 1.31) | 1.14 (1.03, 1.27) | 1.15 (1.03, 1.27) |

| Dental use | 0.77 (0.69, 0.84) | 0.78 (0.70, 0.85) | 0.77 (0.70, 0.85) |

Estimates correspond to one unit increase;

P=0.01;

P=0.02.

The final model to determine the impact of OHL and SE on DNS is presented in Table 3. When OHL and SE were jointly considered with regard to dental neglect, and independent of race, age and education, SE and dental use were associated with significant decreases in DNS scores, while OHL showed no pattern of association. Considering that dental use could be considered as a “downstream” event of oral health status in a hypothetical model, with worse dental condition leading to more dental visits, we performed an iteration of our multivariate model removing this variable. Exclusion of dental use from the multivariate model resulted in no change in the estimate of OHL (data not shown).

Table 3.

Multivariate linear regression modeling results for dental neglect (DNS scores) among the COHL study participants (n=1280)

| β coefficient | 95% CL | |

|---|---|---|

| OHL (REALD-30) score* | 0.01 | −0.02, 0.05 |

| Race (referent: Whites) | ||

| African American | 0.25 | −0.12, 0.62 |

| Native American | −0.39 | −0.85, 0.07 |

| Age (quintiles) | 0.14 | 0.02, 0.26 |

| Education level | −0.16 | −0.38, 0.05 |

| Dental use | −1.05 | −1.20, −0.90 |

| Self-efficacy (SE) score* | −0.18 | −0.22, −0.14 |

Estimate corresponds to one unit increase.

DISCUSSION

This investigation is the first to examine and report on the association of OHL with self-reported oral health status and dental neglect. We found that WIC clients with higher OHL were more likely to report excellent/very good oral health status versus good/fair/poor. There was a poor correlation between OHL and dental neglect. However, we found that lower SE was strongly correlated with dental neglect, and this association persisted after adjustment for age, race, education, dental use and OHL. Literacy, on the other hand, demonstrated a modest association with oral health status after controlling for age, race, education, and dental use.

The important role of self-efficacy in oral health status provides support to conceptual models that place “appropriate decision-making” between conceptual knowledge and oral health outcomes.35,43 Increased self-efficacy may be an enabling factor for individuals to engage in positive dental behaviors, which is consistent with theories of planned behavior,26 locus of control24 and the social cognitive theory.32 As illustrated in our conceptual model (Figure 1), it is likely that personal characteristics such as self-efficacy mediate and/or modify the impact of literacy on oral health behaviors. We used the general self-efficacy measure instead of an oral health specific one. Although such instruments that could capture dental situation-specific dimensions have been developed and validated in dentistry,49–51 they have not been widely tested. In contrast this, the role of general self-efficacy as a determinant, modifier or moderator of health behavior change or maintenance is well-supported.33,34,52–55

Our data revealed a poor correlation between OHL and dental neglect. The construct of dental neglect was defined by Thomson and Locker41 as “failure to take precautions to maintain oral health, failure to obtain needed dental care, and physical neglect of the oral cavity.” This construct may be too narrow to encompass the entire spectrum of self-care, preventive attitudes and dental attendance altogether. Further work is warranted to identify these pathways that could be potential targets for oral health interventions.

Although the effect estimates for the association between OHL and SE with oral health status are small (PR of 1.02 and 1.05, respectively, in Model B), they correspond to one-point changes of these variables. Using these multivariate model-derived coefficients for the association of literacy and self-efficacy with oral health status, it is estimated that 10-unit increases of REALD-30 or SE scores correspond to PR= 1.25 (95% CL=1.05, 1.49) and OR=1.64 (95% CL=1.31, 2.06), respectively. Moreover, the “synergistic” interaction between literacy and self-efficacy in model C, although small in magnitude, indicated that the “effect” of literacy was more pronounced among individuals with higher SE, and vice versa.

The rationale for considering both effect mediation or modification is supported by the fact that the determination of a variable as a mediator is context-specific and requires prior knowledge or underlying theory that the variable of interest is on causal pathway between exposure and the outcome.36 Previous studies examining health behaviors have indeed considered SE both as a mediator and a modifier (moderator).56 In the context of OHL, no previous studies had examined the relationship between literacy and SE. While an association between health literacy and SE was not found in some previous studies in medicine,19,20 evidence from two recent investigations supports the link between literacy and SE.18,57 SE was found to be a strong correlate of oral hygiene behaviors among Australian dental patients.49

Although we did not conduct formal pathway analyses to support the proposed conceptual model, we did find a marked effect attenuation of the OHL-oral health status association when SE was entered in the model (contrast of models A and B). This indicates that OHL may confer its effect on oral health status via SE, as has been suggested for health literacy and health status.17,52 This finding should be interpreted with caution until future studies formally investigate these pathways. Similarly, when dental neglect was examined as the analytical endpoint, SE was significantly inversely correlated with neglect but OHL did not shown any material association.

Our finding of an interaction between literacy and self-efficacy constitutes evidence of effect modification that underscores the importance of considering both dental-specific and personality measures as correlates or antecedents of oral health behaviors and outcomes.31 Evidence indicates that SE may be improved via knowledge enhancement.58,59 Thus, providing individuals with the necessarily skills to obtain, understand and act upon dental-related information has the potential to increase their ability to cope with the demands of oral health maintenance and ultimately lead to improved oral health outcomes. Along these lines, Bandura60 has suggested that “belief in one’s efficacy to exercise control is a common pathway through which psychosocial influences affect health functioning”. Using this paradigm in planning interventions, depending on literacy or self-efficacy criteria, a determination could be made that certain individuals may benefit more from the use of visual materials to communicate key information, whereas others may benefit from behavior reinforcement and motivational interviewing (MI). MI is a patient-centered, directive therapeutic technique designed to enhance readiness for change by helping individuals explore and resolve ambivalence59 and potentially increase their coping skills.53 It is one intervention method that has been used successfully for the treatment of health-behavior based problems,62 and it has been recently tested in the dental arena as a preventive strategy among caregivers for the prevention of early childhood caries.63 Stewart et al59 as well as several recent investigations64–66 have described effective applications of such approaches in improving dental patients’ knowledge, self-efficacy and behaviors.

These results should be considered in light of the study’s limitations. The data were collected from a non-probability convenience sample of clients from the NC-WIC clinics. Our sample characteristics prevent generalization of results beyond female WIC clients enrolled in WIC and attending the specific clinics in NC during the time of this study. Future research should draw from a population-based probability sample. REALD-30 has been validated in English only, so our recruitment was limited to English-speaking patients. Also, our measurement of OHL is based on a word recognition test.37 While word recognition instruments measure only selected aspects of literacy skills and are not comprehensive, comparable word recognition instruments have been used with success in medicine and they are correlated strongly with reading fluency. Our initial investigations compared the REALD-30 versus a dental functional health literacy test and found a high correlation between the two.67 More recent reports comparing functional literacy estimates with word recognition and numeracy assessments have also confirmed the high correlation between these measures.68

Although our subjects were recruited from a non-probability, convenience sample of NC-WIC clients and thus may have limited external validity, we feel that this population is an important one to examine. WIC was established by the Food and Nutrition Services of the Department of Agriculture (USDA) to target low-income women, infants, and children who are at risk nutritionally. WIC’s goal is to improve the health outcomes of its clients by providing nutritious foods, nutritional education, counseling, and medical/dental referrals to facilitate good health care during pregnancy, the post-partum period, infancy, and early childhood. WIC has a huge reach, serving over 9.1 million individuals annually and over a third of all infants born in the US today.69 WIC is often the first contact with the healthcare system for the poor. Because of its repeated contact with vulnerable populations, WIC is uniquely positioned to identify families with low health literacy.

In summary, to date research in OHL has been based on only a few studies of care-seeking subjects. This investigation is the first to report on the relationship of OHL, self-efficacy, dental neglect and self-reported oral health status in a cohort of participants in a large public health program. Based on our findings, we advocate for the consideration of personality traits, such as self-efficacy, with OHL, as risk factors or screeners for poorer oral health outcomes and in planning of oral health intervention programs.

Acknowledgments

The COHL Project is supported by NIDCR Grant#RO1DE018045

References

- 1.Kutner M, Greenburg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy (NCES 2006–483) U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: National Center for Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kircsh I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult Literacy in America: a first look at the findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington DC: US Department of Education; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:791–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166–172. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS, Nurss J. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1027–1030. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker RM, Williams MV, Baker DW, Nurss JR. Literacy and contraception: exploring the link. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(3 Suppl):72S–77S. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–541. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams MV, Parker RM, Baker DW, et al. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA. 1995;274:1677–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:204–211. doi: 10.1370/afm.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborn CY, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Health literacy: an overlooked factor in understanding HIV health disparities. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schillinger D, Barton LR, Karter AJ, Wang F, Adler N. Does literacy mediate the relationship between education and health outcomes? A study of a low-income population with diabetes. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:245–254. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Promoting health literacy research to reduce health disparities. J Health Commun. 2010;15 (Suppl 2):34–41. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy, health inequality and a just healthcare system. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7:5–10. doi: 10.1080/15265160701638520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31 (Suppl 1):S19–26. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osborn CY, Paasche-Orlow MK, Bailey SC, Wolf MS. The mechanisms linking health literacy to behavior and health status. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35:118–128. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeWalt DA, Boone RS, Pignone MP. Literacy and its relationship with self-efficacy, trust, and participation in medical decision making. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31 (Suppl 1):S27–35. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar U, Fisher L, Schillinger D. Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy? Diabetes Care. 2006;29:823–829. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Health, U. S. Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services. The invisible barrier: Literacy and its relationship with oral health. A report of a workgroup sponsored by the national institute of dental and craniofacial research, national institute of health, U.S. public health service, department of health and human services. J Public Health Dent. 2005;65:174–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2005.tb02808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mucci LA, Björkman L, Douglass CW, Pedersen NL. Environmental and heritable factors in the etiology of oral diseases--a population-based study of Swedish twins. J Dent Res. 2005;84:800–805. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Astrom AN, Ekback G, Ordell S, Unell L. Socio-behavioral predictors of changes in dentition status: a prospective analysis of the 1942 Swedish birth cohort. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010 Nov 29; doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peker K, Bermek G. Oral health: locus of control, health behavior, self-rated oral health and socio-demographic factors in Istanbul adults. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:54–64. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.535560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindmark U, Hakeberg M, Hugoson A. Sense of coherence and oral health status in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:12–20. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.517553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buunk-Werkhoven YA, Dijkstra A, Van Der Schans CP. Determinants of oral hygiene behavior: a study based on the theory of planned behavior. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010 Nov 10; doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stenström U, Einarson S, Jacobsson B, Lindmark U, Wenander A, Hugoson A. The importance of psychological factors in the maintenance of oral health: a study of Swedish university students. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2009;7:225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe GR, Stewart JE, Hartz GW. Relationship of dental coping beliefs and oral hygiene. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:112–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schou L. The relevance of behavioural sciences in dental practice. Int Dent J. 2000:324–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00582.x. Suppl Creating A Successful. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollister MC, Anema MG. Health behavior models and oral health: a review. J Dent Hyg. 2004;78:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yevlahova D, Satur J. Models for individual oral health promotion and their effectiveness: a systematic review. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:190–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waller KV, Bates RC. Health locus of control and self-efficacy beliefs in a healthy elderly sample. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6:302–309. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syrjälä AM, Knuuttila ML, Syrjälä LK. Self-efficacy perceptions in oral health behavior. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:1–6. doi: 10.1080/000163501300035661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macek MD, Haynes D, Wells W, Bauer-Leffler S, Cotten PA, Parker RM. Measuring conceptual health knowledge in the context of oral health literacy: preliminary results. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Dzewaltowski DA, Owen N. Toward a better understanding of the influences on physical activity: the role of determinants, correlates, causal variables, mediators, moderators, and confounders. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(2 Suppl):5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JY, Divaris K, Baker AD, Rozier RG, Lee SY, Vann WF., Jr Oral health literacy levels among a low income population. J Public Health Dent. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00244.x. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JY, Rozier RG, Lee SY, Bender D, Ruiz RE. Development of a word recognition instrument to test health literacy in dentistry: The REALD-30--a brief communication. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67:94–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamieson LM, Thomson M. Dental health, dental neglect, and use of services in an adult Dunedin population sample. N Z Dent J. 2002;98:4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jamieson LM, Thomson WM. The Dental Neglect and Dental Indifference scales compared. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002 Jun;30(3):168–75. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomson WM, Locker D. Dental neglect and dental health among 26-year-olds in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000 Dec;28(6):414–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coolidge T, Heima M, Johnson EK, Weinstein P. The Dental Neglect Scale in adolescents. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacKinnon D, Luecken L. Statistical analysis for identifying mediating variables in public health dentistry interventions. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:S37–S46. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scholz U, Gutiérrez-Doña B, Sud S, Schwarzer R. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2002;18:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- 46.D’Agostino RB, Balanger A, D’Agostino RB., Jr A suggestion for using powerful and informative tests of normality. American Statistician. 1990;44:316–321. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skov T, Deddens J, Petersen MR, Endahl L. Prevalence proportion ratios: estimation and hypothesis testing. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:91–95. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buglar ME, White KM, Robinson NG. The role of self-efficacy in dental patients’ brushing and flossing: testing an extended Health Belief Model. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kakudate N, Morita M, Sugai M, Nagayama M, Kawanami M, Sakano Y, Chiba I. Development of the self-efficacy scale for maternal oral care. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32:310–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Syrjälä A-MH, Kneckt MC, Knuuttila MLE. Dental self-efficacy as a determinant to oral health behaviour, oral hygiene and HbA1c level among diabetic patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:616–621. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, Rothman RL. Self-efficacy links health literacy and numeracy to glycemic control. J Health Commun. 2010;15 (Suppl 2):146–158. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strecher VJ, DeVellis BM, Becker MH, Rosenstock IM. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1986;13:73–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skaret E, Kvale G, Raadal M. General self-efficacy, dental anxiety and multiple fears among 20-year-olds in Norway. Scand J Psychol. 2003;44:331–337. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCaul KD, O’Neill K, Glasgow RE. Predicting the performance of dental hygiene behaviors: an examination of the Fishbein and Ajzen model and self-efficacy expectations. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1988;18:114–128. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Latka MH, Hagan H, Kapadia F, et al. A randomized intervention trial to reduce the lending of used injection equipment among injection drug users infected with hepatitis C. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:853–861. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Osborn CY, Skripkauskas S, Bennett CL, Makoul G. Literacy, self-efficacy, and HIV medication adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Renz AN, Newton JT. Changing the behavior of patients with periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2009;51:252–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stewart JE, Wolfe GR, Maeder L, Hartz GW. Changes in dental knowledge and self-efficacy scores following interventions to change oral hygiene behavior. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller WSR. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. A meta-analysis of research on motivational interviewing treatment effectiveness. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harrison R, Veronneau J, Leroux B. Design and implementation of a dental caries prevention trial in remote Canadian Aboriginal communities. Trials. 2010;11:54. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buunk-Werkhoven YA, Dijkstra A, van der Wal H, et al. Promoting oral hygiene behavior in recruits in the Dutch Army. Mil Med. 2009;174:971–976. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-05-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kakudate N, Morita M, Sugai M, Kawanami M. Systematic cognitive behavioral approach for oral hygiene instruction: a short-term study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weyant R. Interventions based on psychological principles improve adherence to oral hygiene instructions. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2009;9:9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gong DA, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Pahel BT, Richman JA, Vann WF., Jr Development and testing of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Dentistry (TOFHLiD) J Public Health Dent. 2007;67:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sabbahi DA, Lawrence HP, Limeback H, Rootman I. Development and evaluation of an oral health literacy instrument for adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:451–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.United States Department of Agriculture. Food and nutrition service. [Accessed March 21, 2011];WIC Program Annual Summary (1974–2010) Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wisummary.htm.