Abstract

Prostaglandins (PGs) are essential signaling factors in bone mechanotransduction. In animals, inhibition of the enzyme responsible for PG synthesis (cyclo-oxygenase) by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) blocks the bone formation response to loading when administered before, but not immediately after, loading. The aim of this proof-of-concept study was to determine whether the timing of NSAID use influences BMD adaptations to exercise in humans. Healthy, premenopausal women (n=73) aged 21 to 40 years completed a supervised 9-month weight-bearing exercise training program. They were randomized to take 1) ibuprofen (400 mg) before exercise, placebo after (IBUP/PLAC); 2) placebo before, ibuprofen after (PLAC/IBUP); or 3) placebo before and after (PLAC/PLAC). Relative changes in hip and lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) from before to after exercise training were assessed using a Hologic Delphi-W DXA instrument. Because this was the first study to evaluate whether ibuprofen use affects skeletal adaptations to exercise, only women who were compliant to exercise were included in the primary analyses (IBUP/PLAC, n=17; PLAC/IBUP, n=14; PLAC/PLAC, n=23). There was a significant effect of drug treatment, adjusted for baseline BMD, on the BMD response to exercise for regions of the hip (total, P<0.001; neck, P=0.026; trochanter, P=0.040; shaft, P=0.019), but not the spine (P=0.242). The largest increases in BMD occurring in the group that took ibuprofen after exercise. Total hip BMD changes averaged −0.2±1.3%, 0.4±1.8%, and 2.1±1.7% in IBUP/PLAC, PLAC/PLAC, and PLAC/IBUP, respectively. This preliminary study suggests that taking NSAIDs after exercise enhances the adaptive response of BMD to exercise, whereas taking NSAIDs before may impair the adaptive response.

Keywords: exercise training, bone mineral density, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclo-oxygenase, prostaglandins

Introduction

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) increases in bone in response to mechanical loading and appears to be an essential intermediate in the signaling pathway for bone formation (i.e., mechanotransduction).6,34,36 The key enzyme involved in the production of PGE2 and other prostaglandins is cyclooxygenase (COX). Inhibition of COX with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) markedly diminishes the bone formation response to mechanical stress in laboratory animals and cultured osteoblasts.5,7–9,20 This effect has been observed in response to both non-selective5,7–9 and COX-2 selective inhibitors,9,20 which is consistent with the observation that mechanotransduction is mediated primarily through the activation of COX-2.2 Importantly, the timing of NSAID administration appears to be a key determinant of the bone formation response. Formation is significantly attenuated when NSAIDs are administered before mechanical loading, but not when they are administered after.7,20

An important limitation of these studies is that they evaluated the bone formation response to acute mechanical loading only. Thus, it is not clear whether the usual effects of repeated bouts of mechanical loading (i.e., exercise training) to increase bone mineral density (BMD) and strength are impaired by NSAID use. Chronic exposure to NSAIDs has been found to have deleterious effects on bone in rats restricted to usual cage activity,30,32 although this is not a consistent observation.12 Because PGE2 plays a role in the activation of both bone formation and resorption, chronic NSAID use could have anti-formation and/or anti-resorptive actions, and the net effect on BMD could be beneficial, detrimental, or neutral.28 In this context, it is not surprising that the human cohort studies that have examined the associations of NSAID use with BMD, markers of bone turnover, or fracture risk have yielded mixed results.3,4,19,23,29,35 Importantly, a consistent finding among studies of animals is that NSAIDs markedly diminish the bone formation response to mechanical stress when administered before loading.

Because there have been no studies, in animals or humans, of the effects of NSAID use on skeletal adaptations to exercise, the current study was considered a preliminary, proof-of-concept investigation. The primary aim was to determine whether ibuprofen, a commonly used non-selective COX inhibitor, attenuates the BMD adaptations to exercise training. A second aim was to determine whether the timing of ibuprofen use (i.e., before versus after exercise) influences the adaptive response. Based on the studies of the timing of NSAID administration on the bone formation response to a single loading bout in animals,7,20 we hypothesized that taking ibuprofen before exercise sessions would attenuate the increases in BMD in response to exercise training when compared with taking ibuprofen after exercise sessions or with placebo treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of the effects of ibuprofen use, and the timing of use relative to performance of exercise, on the BMD response to a 9-month exercise training program. Although conducted as a randomized controlled trial, this was a proof-of-concept study to determine whether there is translation of the skeletal effects of NSAIDS in rodents7,20 to human physiology. Volunteers provided written informed consent to participate and the study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

The participants were healthy, eumenorrheic women, aged 21 to 40 years. Eumenorrheic status was defined as having a menstrual cycle length of 25–31 days and at least 10 cycles in the previous year. Women on progestin-only contraceptive therapy were excluded, but other hormonal contraceptive therapy was allowed. Other inclusion criteria were: exercising <3 days/week at moderate to high intensity; body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2; nonsmoker for >2 years; not pregnant or lactating; no NSAID intolerance or sensitivity; typical NSAID use <3 days/month; no use of drugs that affect bone metabolism; serum thyroid stimulating hormone 0.5–5.0 μU/mL; hematocrit ≥30%; serum creatinine <1.4 mg/dL; no history of ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding, gastroesophageal reflux disease, thrombocytopenia, or bleeding disorders; no known liver disease, kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hypertension. Volunteers who met eligibility criteria and were willing to continue in the study (N=95) were randomized to 3 treatment arms before starting the supervised 9-month exercise training program: 1) ibuprofen before exercise, placebo after exercise (IBUP/PLAC; n=31); 2) placebo before exercise, placebo after exercise (PLAC/PLAC; n=31); and 3) placebo before exercise, ibuprofen after exercise (PLAC/IBUP; n=33).

Drug intervention

Participants took two study capsules, one before exercise and one after, on each day of supervised exercise. The capsules were prepared by a local pharmacy (Belmar Pharmacy; Lakewood, CO) and contained either ibuprofen 400 mg or inactive ingredients. All capsules were identical in appearance with the exception that capsules taken 1–2 hours before the exercise sessions were green and those taken immediately after exercise were red. Participants recorded the time that the pre-exercise capsule was taken when they arrived at the exercise facility. The post-exercise pill was taken immediately after completing the exercise session and the time was recorded. Randomization to the three drug intervention arms was stratified for use of hormonal contraceptive therapy. The University of Colorado Denver Research Pharmacy managed the randomization process, maintained all drug intervention records, and prepared and dispensed study drug packets.

Exercise training intervention

All women in the study participated in a 9-month weight-bearing exercise training program. The general structure of the exercise training program was similar to programs used in previous studies that resulted in increases in BMD.16,17 Participants were instructed to attend at least 3 supervised exercise sessions per week. The exercise program included weight-bearing endurance exercises (e.g., walking, jogging, rope jumping, stair climbing/descending), weight-supported endurance exercise that generates relatively high muscle forces (e.g., rowing), box jumps (e.g., step up onto a platform, jump off, 2-foot landing), and upper- and lower-body resistance exercises. The lower-body, biceps, and triceps exercises were performed unilaterally. Exercise was initially prescribed at a moderate intensity (60–70% of maximal heart rate, 3 sets of 12 to 15 repetitions at 60–70% of 1-repetition maximum) for a total of 30 min/d. The duration and intensity of exercise were increased gradually on an individualized basis, with exercise prescriptions updated weekly. Box jump height started at 8 inches and was increased by 2 inches as tolerated to a maximum of 16 inches. The goal was to perform a combination of high-intensity endurance (80–85% of maximal heart rate), resistance (3 sets of 8 to 10 repetitions at 70–80% of 1-repetition maximum), and jumping exercises for a total exercise time of ~45 min/d over the last 3 months of the program, not including time to warm up and cool down.

BMD and body composition

BMD of the total body, lumbar spine (L2–L4), and proximal femur (total, neck, trochanter, shaft) was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) on a Hologic Delphi-W instrument (Hologic, Inc.; Bedford, MA) at baseline and after 9 months of exercise training. The total body scan also provided measures of fat mass and fat-free mass. In our laboratory, the coefficients of variation (CVs) for lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, trochanter and shaft (i.e., sub-trochanteric region) BMD are (mean ± SD) 1.2 ± 0.8, 0.8 ± 0.6, 1.9 ± 0.9, 1.5 ± 1.0 and 1.1 ± 0.6%, respectively. CVs for fat-free mass and fat mass are 1.2 ± 0.8% and 1.8 ± 0.9%, respectively. Calibration procedures included spine phantom scans daily, whole-body phantom scans 3 times per week, air scans 1 time per week, and tissue bar scans 1 time per month.

Statistical analyses

Because there have been no previous intervention studies of the effects of regular NSAID use on BMD adaptations to exercise, this was a physiological study of the effects that occur when there is compliance to the exercise program. Therefore, the primary data analysis was per-protocol rather than intent-to-treat. Compliance was defined as attending at least 80% of the prescribed exercise sessions over the 9-month intervention (i.e., at least 2.4 per week). Data are reported as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

Homogeneity across groups at baseline was verified by one-way analyses of variance for age, BMI, weight, fat mass, fat-free mass, and BMD. A chi-square test for equal proportions across groups was applied to ethnicity and hormonal contraception use. The baseline data were also examined for differences by hormonal contraception use with 2-group t tests, chi-square or exact chi-square tests, as appropriate.

The effects of ibuprofen on the BMD responses to exercise training were evaluated by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), regressing the 9-month change in BMD on baseline BMD and group (IBUP/PLAC, PLAC/IBUP, PLAC/PLAC). The same method was used to assess the effects of age, change in body weight, and use of hormonal contraception. Although p values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, we protected the type I error rate by requiring a priori that effects be significant for more than one BMD region, and by testing for any differences across groups before testing pair-wise differences. Pair-wise comparisons were considered significant only when both the global F and the pair-wise comparison were significant at an alpha level ≤0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified.

Results

Of the 95 volunteers randomized to the drug treatment arms, 73 completed the 9-month exercise program, and 54 completed at least 80% of the prescribed sessions. The attrition and noncompliance rates were higher than expected, but it is unlikely that this was related to the intervention, per se. Rather, because the study was carried out during a time interval when the university was moving to a new campus, these factors were negatively influenced by the relocation of the exercise training facility twice during the study (i.e., from the old campus to an interim off-campus facility and then to the new campus).

The treatment groups in the subset of participants who were compliant to the intervention were well-matched on baseline characteristics (Table 1). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between users and non-users of hormonal contraception (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of compliant participants

| Variable | N (%) or mean ± SD and p values for comparisons by group

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | IBUP/PLAC | PLAC/PLAC | PLAC/IBUP | p value | |

| Hormonal contraceptives | no | 9 (52.9) | 14 (60.9) | 7 (50.0) | 0.784 |

| yes | 8 (47.1) | 9 (39.1) | 7 (50.0) | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 14 (82.4) | 20 (87.0) | 14 (100.0) | 0.404 |

| Hispanic | 2 (11.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 1 (5.9) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Age, y | 30.8 ± 6.2 | 33.2 ± 5.3 | 32.1 ± 5.0 | 0.418 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.0 ± 4.5 | 23.6 ± 2.8 | 23.6 ± 3.0 | 0.935 | |

| Height, cm | 165.0 ± 8.5 | 167.2 ± 7.8 | 165.2 ± 5.7 | 0.580 | |

| Weight, kg | 66.5 ± 9.3 | 67.0 ± 9.8 | 64.9 ± 9.4 | 0.795 | |

| Fat mass, kg | 21.5 ± 5.2 | 22.5 ± 6.7 | 21.0 ± 7.3 | 0.775 | |

| Fat-free mass, kg | 45.0 ± 5.1 | 44.5 ± 5.1 | 43.8 ± 5.2 | 0.821 | |

| BMD, g/cm2 | |||||

| total hip | 1.005 ± 0.112 | 0.982 ± 0.128 | 0.978 ± 0.116 | 0.782 | |

| femoral neck | 0.896 ± 0.127 | 0.886 ± 0.114 | 0.915 ± 0.125 | 0.793 | |

| trochanter | 0.755 ± 0.105 | 0.760 ± 0.098 | 0.754 ± 0.127 | 0.980 | |

| shaft | 1.184 ± 0.118 | 1.150 ± 0.166 | 1.128 ± 0.130 | 0.552 | |

| lumbar spine | 1.092 ± 0.124 | 1.130 ± 0.122 | 1.061 ± 0.152 | 0.293 | |

IBUP, ibuprofen; PLAC, placebo; BMI, body mass index; BMD, bone mineral density

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by use of hormonal contraceptive therapy

| Variable | Mean ± SD or N (%) and p values for comparisons by OC Use

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Yes | No | p value | |

| Ethnicity | White | 20 (83.3) | 28 (93.3) | 0.6529 |

| Hispanic | 3 (12.5) | 1 ( 3.3) | ||

| Other | 1 ( 4.2) | 1 ( 3.3) | ||

| Age, y | 31.0 ± 4.6 | 33.1 ± 6.0 | 0.1728 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.9 ± 2.2 | 24.3 ± 4.1 | 0.1194 | |

| Height, cm | 166.7 ± 6.8 | 165.39 ± 8.06 | 0.5149 | |

| Weight, kg | 64.5 ± 8.2 | 67.77 ± 10.17 | 0.2045 | |

| Fat mass, kg | 20.2 ± 5.2 | 23.12 ± 6.92 | 0.0948 | |

| Fat-free mass, kg | 44.3 ± 4.7 | 44.65 ± 5.36 | 0.7862 | |

| BMD, g/cm2 | ||||

| total hip | 0.986 ± 0.128 | 0.990 ± 0.113 | 0.8901 | |

| femoral neck | 0.901 ± 0.131 | 0.894 ± 0.112 | 0.8319 | |

| trochanter | 0.751 ± 0.112 | 0.762 ± 0.103 | 0.7144 | |

| shaft | 1.154 ± 0.143 | 1.156 ± 0.144 | 0.9474 | |

| lumbar spine | 1.098 ± 0.140 | 1.102 ± 0.126 | 0.9246 | |

Exercise intervention

There were no significant differences among the groups in the amount of exercise performed during the intervention. Among those who were compliant, the average exercise frequency was 3.4 ± 0.6, 3.4 ± 0.6, and 3.6 ± 0.6 d/wk in the IBUP/PLAC, PLAC/PLAC, and PLAC/IBUP groups, respectively. The average volume of exercise performed by all participants in the second month of the study (after participants had become accustomed to the equipment) and in the eighth month of the study (before final follow-up testing began) is summarized in Table 3. Treadmill walking/running was the most commonly performed endurance exercise.

Table 3.

Average (mean ± SD) volume of exercise performed in months 2 and 8 of the 9-month intervention

| Weeks 5 – 8 | Weeks 29 – 32 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance exercises | Repetitions | Weight, lb | Repetitions | Weight, lb |

| leg extension1 | 39 ± 10 | 44 ± 16 | 26 ± 12 | 52 ± 26 |

| leg flexion1 | 41 ± 9 | 44 ± 14 | 26 ± 13 | 52 ± 26 |

| leg press1 | 35 ± 19 | 86 ± 52 | 28 ± 15 | 128 ± 61 |

| lat pulldown | 42 ± 9 | 107 ± 33 | 27 ± 14 | 131 ± 62 |

| bench press | 41 ± 8 | 63 ± 20 | 26 ± 13 | 79 ± 36 |

| overhead press | 40 ± 8 | 40 ± 13 | 26 ± 12 | 49 ± 21 |

| biceps curl1 | 40 ± 8 | 22 ± 6 | 25 ± 13 | 24 ± 11 |

| triceps extension1 | 41 ± 8 | 15 ± 5 | 27 ± 13 | 22 ± 12 |

| seated row | 32 ± 20 | 57 ± 38 | 26 ± 14 | 88 ± 42 |

| Box jumps, number/week | 110 ± 33 | 121 ± 60 | ||

| height, in | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 15.7 ± 1.0 | ||

| Stairs, flights/week | 4.3 ± 3.4 | 8.6 ± 4.0 | ||

| Weight-bearing endurance exercises | ||||

| duration, min/week | 97.3 ± 40.0 | 103.0 ± 73.0 | ||

| heart rate, beats/min | 154.6 ± 12.2 | 157.0 ± 11.3 | ||

exercises performed unilaterally

Across the entire 9-month exercise program, the time interval between the pre-exercise and post-exercise study drug doses averaged 2.37 ± 0.44, 2.45 ± 0.46, and 2.55 ± 0.46 hours (p=0.55) for the IBUP/PLAC, PLAC/PLAC, and PLAC/IBUP groups, respectively. Because the post-exercise capsule was taken immediately upon completion of an exercise session, this indicates that the pre-exercise capsule was typically taken about 1.5 hours before an exercise session. Pill compliance, assessed as the percentage of prescribed doses based on exercise frequency, was 83 ± 20%, 80 ± 24%, and 86 ± 16% in the IBUP/PLAC, PLAC/PLAC, and PLAC/IBUP groups, respectively.

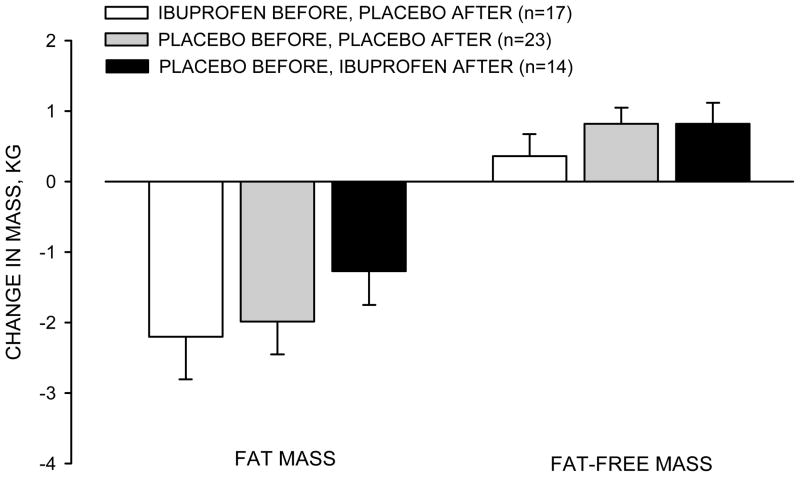

Changes in body composition

There were no significant differences among the groups in the changes in fat mass or fat-free mass in response to exercise training (Figure 1). The changes in fat mass were −2.2 ± 2.5 kg, −2.0 ± 2.2 kg, and −1.3 ± 1.8 kg in the IBUP/PLAC, PLAC/PLAC, and PLAC/IBUP groups, respectively. The respective changes in fat-free mass were 0.4 ± 1.3 kg, 0.8 ± 1.1 kg, and 0.8 ± 1.1 kg.

Figure 1.

Changes in fat mass and fat-free mass in response to exercise training. Values are mean ± SE.

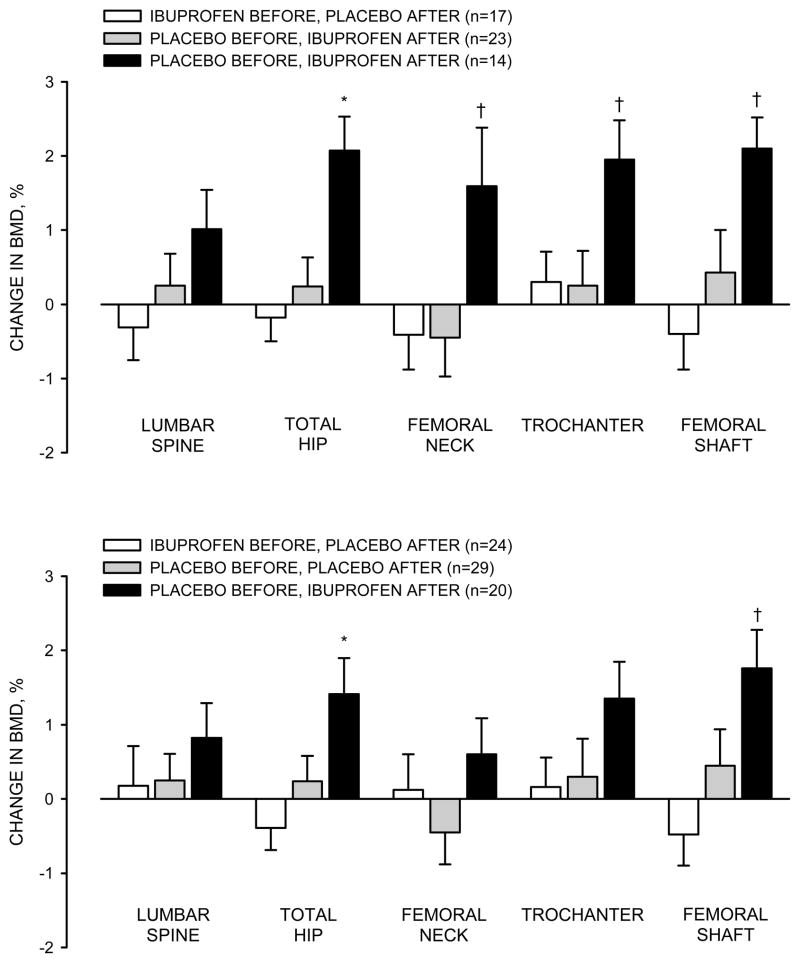

Changes in BMD

As hypothesized, among women who were compliant to the exercise intervention, taking ibuprofen before exercise (IBUP/PLAC) impaired the increases in BMD when compared with taking ibuprofen after exercise (PLAC/IBUP), although the effect at the lumbar spine was not statistically significant (Figure 2, top panel). The differences (mean ± SE; adjusted for baseline BMD) between these two groups in the changes in BMD were 0.013 ± 0.008 g/cm2 for the lumbar spine (p=0.100), 0.020 ± 0.005 g/cm2 for the total hip (p=0.001), 0.018 ± 0.008 for the femoral neck (p=0.020), 0.012 ± 0.006 g/cm2 for the trochanter (p=0.030), and 0.024 ± 0.009 g/cm2 for the femoral shaft (p=0.007). The inclusion of age, change in body weight, or use of hormonal contraception in the analysis model did not change the results. As would be expected, the magnitude of differences between the groups was diminished by the inclusion of participants who were not compliant to exercise (Figure 2, bottom panel). However, the pattern of group differences remained.

Figure 2.

Relative changes (%) in bone mineral density (BMD), adjusted for baseline BMD, in response to exercise training in participants who were compliant to the intervention (top panel) and in all participants who finished the intervention (bottom panel). Values are mean ± SE. * different from the other groups, p≤0.01; † different from the other groups, p≤0.05

In contrast to the hypothesis, the group that received only placebo treatment (PLAC/PLAC) did not have the most robust increases in BMD. Increases in BMD in this group tended to be only slightly, but not significantly, larger than in the IBUP/PLAC group in some regions (Figure 2; top panel). Unexpectedly, the increases in BMD adjusted for baseline BMD were significantly greater in the PLAC/IBUP group than the PLAC/PLAC group at the femoral neck (difference: 0.019 ± 0.007 g/cm2; p=0.010), hip (0.018 ± 0.005 g/cm2; p=0.001), trochanter (0.013 ± 0.005 g/cm2; p=0.020), and femoral shaft (0.019 ± 0.008 g/cm2; p=0.020); the difference at the lumbar spine was not statistically significant (0.006 ± 0.007 g/cm2; p=0.431 ).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether the regular use of ibuprofen before or after exercise sessions influences the BMD adaptations to exercise training. The scientific basis for the study was the evidence from animal studies that the acute increase in bone formation in response to mechanical loading is markedly inhibited when NSAIDs are administered before, but not after, mechanical loading.7,9,20 Consistent with this evidence, we found that taking ibuprofen before exercise resulted in the least favorable adaptations in BMD. However, in contrast to our expectation that the PLAC/PLAC and PLAC/IBUP groups would have similar increases in BMD, we found that the largest increases occurred in the group that took ibuprofen immediately after completing the exercise sessions.

Ibuprofen and other nonselective and selective COX inhibitors are thought to influence bone metabolism by blocking the production of PGE2.28 The actions of PGE2 in bone are complex. The seemingly paradoxical findings that PGE2 can both stimulate and inhibit bone formation and resorption may relate to the distribution of the four prostaglandin receptor subtypes in bone.21 Because the major effects of PGE2 in bone are to stimulate both formation and resorption, blocking PGE2 production with NSAIDs would be expected to have anti-formation and anti-resorptive effects.28 Accordingly, the net effect on BMD could be deleterious or favorable, depending both on relative balance between the anti-formation and anti-resorptive activities and on the state of bone turnover.

Because of the potential anti-resorptive actions of COX inhibitors, several animal studies have evaluated whether NSAIDs prevent the bone loss that occurs following ovariectomy as a result of the increase in bone turnover. Indeed, in one of the early studies, 6 weeks of naproxen treatment reduced ovariectomy-related bone loss by ~70% in adult rats.18 However, in a follow-up study, the same investigators found that 12 weeks of naproxen was ineffective in preventing ovariectomy-related bone loss in adult rats.14 Others have confirmed that NSAIDs are ineffective13 or only partially effective10,12 in attenuating ovariectomy-related decreases in bone volume or BMD.

Chronic NSAID use has also been found to cause bone loss in laboratory animals. In ovariectomized adult rats, 24 weeks of indomethacin treatment caused greater decreases in lumbar spine BMD, trabecular bone volume, and trabecular thickness than vehicle treatment.30 Similarly, treatment of young rats with ibuprofen for 28 days had an independent adverse effect on trabecular bone volume in intact, ovariectomized, ovariectomized estrogen-treated, and ovariectomized tamoxifen-treated animals.32 Male gonad-intact rats treated with a COX-2 selective inhibitor for 30 days had an increase in bone resorption and a decrease in formation but, paradoxically, BMD was preserved.31 However, as with the studies of naproxen discussed above,14,18 a longer duration of treatment with a COX-2 selective inhibitor may be necessary to determine the true effects of COX-2 inhibitors on BMD. These studies of laboratory animals highlight the complex and variable effects of NSAIDs on bone metabolism, which may be influenced by the age of the animal, bone turnover state, type and dose of NSAID, and duration of treatment.

In contrast to the variable effects of chronic NSAID treatment on bone metabolism in animals, a consistent finding is that NSAIDs impair the bone formation response to acute mechanical loading. PGE2 was identified as playing a role in mechanical transduction in bone more than 20 years ago.33 Key evidence that prostaglandins are essential for bone formation came from in vivo mechanical loading experiments in which the expected osteogenic response to mechanical loading was absent when indomethacin was administered.27 Subsequent studies revealed that the bone formation response is mediated by COX-2.2,9 However, in mice lacking COX-2 (i.e., null mutation), a normal bone formation response to mechanical stimulation was achieved through a compensatory increase in COX-1.1 This suggests that non-selective COX inhibitors may suppress bone formation to a greater extent than COX-2 selective inhibitors when used chronically.

The timing of NSAID administration relative to mechanical loading has been found to be an important determinant of the bone formation response. Chow et al. were the first to observe that the increase in bone formation in adult rats was suppressed by indomethacin when it was administered before, but not after, mechanical stimulation.7 This was subsequently confirmed in a study in which a COX-2 inhibitor, NS-398, was administered to rats before or after in vivo mechanical loading of the tibia.20 NS-398 administered 3 hr or 30 min before mechanical loading significantly dampened the bone formation response, whereas administration 30 min after loading did not.

Although there is consistent evidence from studies of animals that the administration of NSAIDs prior to mechanical loading blocks the bone formation response, a limitation is that the studies have assessed the response to only a single bout of loading. To our knowledge, the current study was the first, in humans or animals, to evaluate whether NSAID use, and specifically the timing of use (i.e., before vs after bone-loading exercise), is an important determinant of the adaptation of BMD to repeated mechanical stimulation (i.e., exercise training). Based on the studies of acute loading in animals,7,20 we hypothesized that taking ibuprofen before exercise sessions would blunt the adaptation in BMD, but that taking ibuprofen after exercise sessions would not. The observation that the least favorable changes in BMD tended to occur in the group that took ibuprofen before each exercise training session is interpreted as being consistent with the evidence that COX inhibition prior to loading blocks bone formation.7,9,20,27 However, the robust increases in BMD in the group that took ibuprofen after exercise were not anticipated. Rather, it was expected that the increases in BMD would be similar in the PLAC/PLAC and PLAC/IBUP groups.

Potential reasons for the smaller-than-expected BMD changes in the placebo-only group should be considered. One possibility is that, because they did not receive any NSAID treatment, the physical discomforts that sometimes occur with vigorous exercise training may have caused them to reduce their physical activity level outside of the exercise program. We think this was unlikely, because all participants were instructed to take acetaminophen if they had a need for analgesic therapy. This recommendation was based on the long-standing belief that, in contrast to NSAIDs, the mechanism by which acetaminophen relieves pain does not involve COX suppression. However, recent evidence suggests that acetaminophen does, indeed, act through COX-related mechanisms.11,15 To our knowledge, the effect of acetaminophen on the bone formation response to loading has not been studied. However, if effects are similar to those of NSAIDs, and if the group on placebo-only therapy used more acetaminophen than the groups on ibuprofen, then this may have contributed to the small changes in BMD in the placebo group.

Potential reasons for the larger-than-expected increases in BMD in the group that took ibuprofen after exercise sessions should also be considered. High-intensity endurance and resistance exercise stimulates increases in serum inflammatory cytokines.22,25,26 For example, serum interleukin 6, which is a potent stimulator of bone resorption,24 was increased ~7-fold one hour after a bout of vigorous resistance exercise.25 In general, intense exercise generates increases in inflammatory cytokines that peak within a few hours after cessation of exercise.22 If the exercise performed in the current study generated increases in pro-resorptive cytokines, it is possible that the benefit on BMD of taking ibuprofen immediately after exercise sessions was via the suppression of inflammatory-mediated bone resorption. Further research will be needed to explore such mechanisms.

The bulk of evidence from studies of animals suggests that NSAIDs do not have favorable effects on bone. Accordingly, it might be predicted that chronic NSAID use would be associated with low BMD values in humans. Associations of NSAID use with BMD, bone turnover markers, and/or fracture risk have been evaluated in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures,3 Rancho Bernardo Study,23 Health ABC Study,4 and Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study.29 In all of these studies, analysis of covariance was used to adjust for an array of parameters likely to be associated with the outcomes of interest. After such adjustments, there was no evidence that NSAID use influenced bone turnover or non-vertebral fracture risk. However, in all 4 of the cohort studies, there was some evidence for increased BMD levels in some groups of NSAID users when compared with non-users. As an example, in the Rancho Bernardo Study of women aged 44 to 98 yr,23 regular use of proprionic acid NSAIDs was associated with increased BMD levels of the hip (2–3%) and lumbar spine (~9%).23 This type of favorable association of NSAID use with BMD in humans is seemingly in contrast with the unfavorable effects of NSAIDs on bone metabolism in laboratory animals. However, in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis cohort study,29 favorable effects of COX-2 selective inhibitors on BMD were apparent only in postmenopausal women, and primarily in those on estrogen-based hormone therapy. In contrast, men who used COX-2 selective inhibitors had significantly lower BMD levels than men who did not. Such findings support the concept that bone turnover state may be an important determinant of the effects of NSAIDs on bone metabolism. In high turnover conditions (e.g., postmenopausal women not on hormone therapy), the anti-resorptive effects of NSAIDs may predominate and have a beneficial effect on BMD, whereas in low turnover conditions (e.g., men) the anti-formation effects may predominate and have an adverse effect on BMD.

The current study had some limitations. Participants were instructed to use acetaminophen for pain relief when needed, but there is emerging evidence that acetaminophen has COX inhibitory effects.11,15 No data were collected regarding the use of this medication. Additionally, we did not control for changes in physical activity outside of the exercise intervention; between-group differences in non-intervention exercise or activity could have confounded the findings of the study. This was a small study of premenopausal women and the results may not be applicable to other patient groups with different rates of bone turnover. Because this was the first intervention study of the effects of the timing of NSAID use on adaptations of bone to mechanical loading, many questions remain regarding the potential influence of the type of NSAID, dose, and specific timing of use relative to exercise.

In summary, taking 400 mg of ibuprofen immediately after exercise sessions augmented the beneficial adaptations of BMD to 9 months of exercise training when compared with taking ibuprofen before exercise or with placebo therapy. Because of the common use of over-the-counter NSAIDS among people who exercise regularly, such findings may have important public health ramifications. However, further research is needed, both to confirm the results of this first preliminary study of the timing of NSAID use on skeletal adaptations to exercise training and to determine the extent to which the findings can be generalized to other types and doses of NSAIDs and populations other than premenopausal women. It will also be necessary to determine the mechanisms by which timing of NSAID use relative to exercise influences skeletal adaptations.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by Department of Defense award DAMD-17-01-1-0805 and National Institutes of Health awards R01 AG018857, M01 RR000051 (General Clinical Research Center) and P30 DK048520 (Clinical Nutrition Research Unit).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Wendy M Kohrt, Email: wendy.kohrt@ucdenver.edu.

Daniel W Barry, Email: daniel.barry@ucdenver.edu.

Rachael E Van Pelt, Email: rachael.vanpelt@ucdenver.edu.

Catherine M Jankowski, Email: catherine.jankowski@ucdenver.

Pamela Wolfe, Email: pamela.wolfe@ucdenver.edu.

Robert S Schwartz, Email: robert.schwartz@ucdenver.edu.

References

- 1.Alam I, Warden SJ, Robling AG, Turner CH. Mechanotransduction in bone does not require a functional cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:438–446. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker AD, Klein-Nulend J, Burger EH. Mechanotransduction in bone cells proceeds via activation of COX-2, but not COX-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:677–683. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00831-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer DC, Orwoll ES, Fox KM, Vogt TM, Lane NE, Hochberg MC, Stone K, Nevitt MC. Aspirin and NSAID use in older women: effect on bone mineral density and fracture risk. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:29–35. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbone LD, Tylavsky FA, Cauley JA, Harris TB, Lang TF, Bauer DC, Barrow KD, Kritchevsky SB. Association between bone mineral density and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin: impact of cyclooxygenase selectivity. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1795–1802. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng MZ, Zaman G, Rawlinson SC, Pitsillides AA, Suswillo RF, Lanyon LE. Enhancement by sex hormones of the osteoregulatory effects of mechanical loading and prostaglandins in explants of rat ulnae. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1424–1430. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.9.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow JW. Role of nitric oxide and prostaglandins in the bone formation response to mechanical loading. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28:185–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow JW, Chambers TJ. Indomethacin has distinct early and late actions on bone formation induced by mechanical stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:E287–E292. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.267.2.E287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow JW, Fox SW, Lean JM, Chambers TJ. Role of nitric oxide and prostaglandins in mechanically induced bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1039–1044. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.6.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forwood MR. Inducible cyclo-oxygenase (COX-2) mediates the induction of bone formation by mechanical loading in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:168–1693. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregory LS, Kelly WL, Reid RC, Fairlie DP, Forwood MR. Inhibitors of cyclo-oxygenase-2 and secretory phospholipase A2 preserve bone architecture following ovariectomy in adult rats. Bone. 2006;39:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinz B, Cheremina O, Brune K. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in man. The FASEB Journal. 2008;22:383–390. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8506com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Y, Zhao J, Genant HK, Dequeker J, Geusens P. Bone mineral density and biomechanical properties of spine and femur of ovariectomized rats treated with naproxen. Bone. 1998;22:509–514. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasukawa Y, Miyakoshi N, Srivastava AK, Nozaka K, Maekawa S, Baylink DJ, Mohan S, Itoi E. The selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib reduces bone resorption, but not bone formation, in ovariectomized mice in vivo. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007;211:275–283. doi: 10.1620/tjem.211.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimmel DB, Coble T, Lane N. Long-term effect of naproxen on cancellous bone in ovariectomized rats. Bone. 1992;13:167–172. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(92)90007-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kis B, Snipes JA, Busija DW. Acetaminophen and the Cyclooxygenase-3 Puzzle: Sorting out Facts, Fictions, and Uncertainties. J Pharmocol Exp Therapeut. 2005;315:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohrt WM, Ehsani AA, Birge SJ., Jr Effects of exercise involving predominantly either joint-reaction or ground-reaction forces on bone mineral density in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1253–1261. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohrt WM, Ehsani AA, Birge SJ. HRT preserves increases in bone mineral density and reductions in body fat after a supervised exercise program. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1506–1512. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.5.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane N, Coble T, Kimmel DB. Effect of naproxen on cancellous bone in ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5:1029–1035. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane NE, Bauer DC, Nevitt MC, Pressman AR, Cummings SR. Aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use in elderly women: effects on a marker of bone resorption. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1132–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Burr DB, Turner CH. Suppression of prostaglandin synthesis with NS-398 has different effects on endocortical and periosteal bone formation induced by mechanical loading. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;70:320–329. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1025-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Thompson DD, Paralkar VM. Prostaglandin E(2) receptors in bone formation. Int Orthop. 2007;31:767–772. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0406-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moldoveanu AI, Shephard RJ, Shek PN. The cytokine response to physical activity and training. Sports Med. 2001;31:115–144. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200131020-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morton DJ, Barrett-Connor E, Schneider DL. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and bone mineral density in older women: the Rancho Bernardo study. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13 :1924–1931. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.12.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mundy GR. Osteoporosis and inflammation. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S147–S151. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieman DC, Davis JM, Brown VA, Henson DA, Dumke CL, Utter AC, Vinci DM, Downs MF, Smith JC, Carson J, Brown A, McAnulty SR, McAnulty LS. Influence of carbohydrate ingestion on immune changes after 2 h of intensive resistance training. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1292–1298. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01064.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsen G, Benestad HB, Strom-Gundersen I, Morkrid L, Lappegard KT, Raastad T. Delayed leukocytosis and cytokine response to high-force eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1877–1883. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000177064.65927.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pead MJ, Lanyon LE. Indomethacin modulation of load-related stimulation of new bone formation in vivo. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;45:34–40. doi: 10.1007/BF02556658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raisz LG. Potential impact of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors on bone metabolism in health and disease. Am J Med. 2001;110(Suppl 3A):43S–45S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards JB, Joseph L, Schwartzman K, Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Goltzman D. The effect of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors on bone mineral density: results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1410–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saino H, Matsuyama T, Takada J, Kaku T, Ishii S. Long-term treatment of indomethacin reduces vertebral bone mass and strength in ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1844–1850. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.11.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen CL, Yeh JK, Wang X. Short-term supplementation of COX-2 inhibitor suppresses bone turnover in gonad-intact middle-aged male rats. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24 :461–466. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0709-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sibonga JD, Bell NH, Turner RT. Evidence that ibuprofen antagonizes selective actions of estrogen and tamoxifen on rat bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:863–870. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somjen D, Binderman I, Berger E, Harell A. Bone remodelling induced by physical stress is prostaglandin E2 mediated. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;627:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(80)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorsen K, Kristoffersson AO, Lerner UH, Lorentzon RP. In situ microdialysis in bone tissue. Stimulation of prostaglandin E2 release by weight-bearing mechanical loading. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2446–2449. doi: 10.1172/JCI119061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of fractures. Bone. 2000;27:563–568. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaman G, Suswillo RF, Cheng MZ, Tavares IA, Lanyon LE. Early responses to dynamic strain change and prostaglandins in bone-derived cells in culture. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:769–777. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.5.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]