1. INTRODUCTION

All coronaviruses contain only a few molecules of the small envelope (E) protein, but the protein plays an important role in virus assembly. Expression of E and M alone is sufficient for virus-like particle (VLP) assembly.1-3 E protein containing vesicles are released from cells when E is expressed alone.4 E protein may also be involved in determining the virus budding site at the endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi intermediate compartment membrane (ERGIC).5 E protein is important for virion morphology and virus production.6,7 Recently it was demonstrated that the E proteins of both MHV-CoV and SARS-CoV exhibit viroporin activity.9-11 Coronavirus E proteins are small: 83 amino acids for the mouse hepatitis A59 (MHV-CoV A59) protein. All have a long hydrophobic domain (Fig. 1A). The transmembrane (TM), in addition to anchoring the protein in the membrane, must also be functionally important for the recently described viroporin activity. We used alanine scanning insertion mutagenesis to begin understanding the role and structural requirements of the E protein TM domain in virus assembly. Our work illustrates the importance of the TM domain and identifies potentially important residues within the domain that may affect the function of the protein.

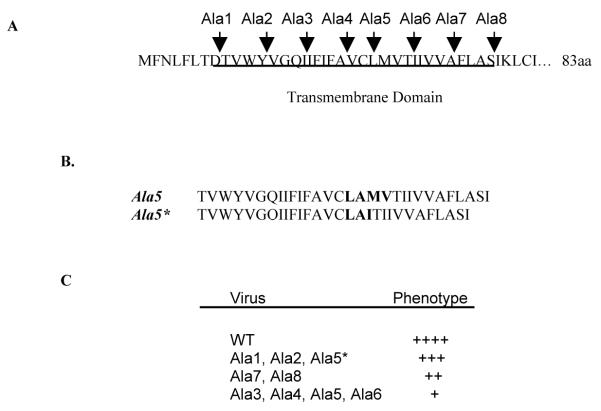

Figure 1.

Alanine insertion mutants. (A) Amino acid sequence of wild-type MHV-CoV A59 E protein TM domain and positions of 8 alanine insertion mutations across TM domain. The putative TM domain is underlined. (B) Comparation of sequence results from RT-PCR of RNA extracted for cells infected with plaque purified Ala 5 and Ala 5* mutant viruses. Amino acids surrounding the ala insertion are bolded. (C) Viruses were grouped according to their phenotype relative to the wild-type virus based on plaque morphology and growth kinetics.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Alanine insertion mutants were created using a whole plasmid PCR protocol with a pair of primers containing the desired mutations. A plasmid containing the E gene was used as the template for PCR. After confirmation of the introduced mutations, the gene was subcloned into the G subclone of the MHV-CoV A59 infectious clone that is part of the seven cDNA fragment (A–G) system, kindly provided by Dr. Ralph Baric at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.12 All full-length cDNA clones were assembled and RNAs were transcribed using a protocol basically as described.12, 13 After electroporation, mutant viruses were recovered by plaque purification. Multiple plaques were passaged on mouse L2 cells, and the presence of mutations were confirmed by reverse transcription and PCR amplification from total RNA from infected cells. The entirety of the E and M genes were sequenced directly from the PCR products. Viruses were passaged six times to determine growth and sequence stability. All viruses were analyzed for plaque size/morphology and growth kinetics relative to the wild-type virus.

3. RESULTS

Alanine scanning mutagenesis was used as part of our studies directed at understanding the functional role of the long TM in the MHV-CoV A59 E protein.13 We chose this approach because insertion of alanine residues disrupts potential helix-helix interactions of residues in the membrane environment. It is a useful approach for mapping the approximate localization of functionally and structurally important parts of TM domains.14 Eight individual alanine insertions were introduced across the TM domain (Fig. 1A).13 The insertions were studied in the context of a full-length infectious clone. Individual viruses were designated as Ala 1–8. Viable mutant viruses were isolated for all of the mutants. Sequencing of the viral RNA confirmed that all, with one exception, retained the inserted alanine, and that no additional changes were present in the remainder of the E or within the M genes. One exception was Ala 5. Ala 5 was made two times. The virus that was recovered from the initial attempt, which we subsequently named Ala 5*, retained the inserted alanine, but also had changes in the adjacent resides on the COOH side of the insertion that resulted in deletion of residues 25 and 26 (methionine and valine) and addition of isoleucine (Fig. 1B). A second ala 5 mutant was generated that did retain the alanine insertion with no other changes. The latter was designated Ala 5.

Plaque purified viruses were passaged six times. The sequence of each mutant was again confirmed. All mutants retained the introduced alanines and no additional changes. The growth characteristics, including plaque size, morphology, and growth kinetics, of P6 of each mutant were analyzed. The viruses were grouped according to their growth properties relative to the wild-type virus (Fig. 1C). Ala 5*, 1 and 2 viruses exhibited growth characteristics similar to the wild-type virus, whereas the growth of the other mutant viruses was significantly reduced.13 Ala 5* grew significantly better than Ala 5, suggesting that the changes observed adjacent to the introduced Ala 5* provide the virus with a growth advantage.

4. DISCUSSION

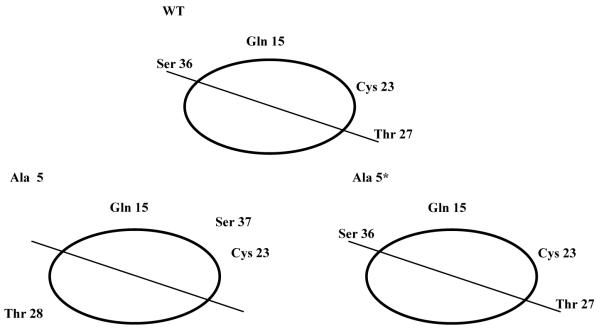

Most of the alanine insertions within the MHV-CoV E TM domain had a significant effect on the growth of the mutant viruses. The plaque size and growth of the mutant viruses were reduced. All together, the results indicate that the E TM domain is functionally important. The role of E in the virus life cycle is not fully understood. The protein is a minor component of the virion envelope, but it plays an important role in virus assembly.6-8 To gain insight into the role of the E protein in the virus life cycle, we asked what effect disruption of the TM would have on the virus by inserting alanine residues at various positions across the domain. The TM domain is presumed to span the membrane as an alpha-helix. Insertion of a single residue in a TM helix results in displacement of residues on the amino-terminal side of the insertion relative to the COOH-side, thus disrupting the helix-helix packing interface of residues. To understand the potential effect of the insertion at position 5 (Ala 5 and Ala5*) for the two mutants described here, amino acids in the TM domain were displayed on an alpha-helical wheel (Fig. 2). Of particular note from this analysis is the positioning of the polar hydrophilic residues glutamine (Gln) 15, threonine (Thr) 27, and serine (Ser) 36, as well as cysteine (Cys) 27. All of these residues are predicted to be positioned on one side of the helix in the wild-type protein (Fig. 2, upper), however insertion of alanine at position 5 in the Ala 5 mutant (Fig. 1) is predicted to shift the relative positions of the Ser and Thr residues (Fig. 2, lower left). Threonine is predicted to be shifted to the opposite side of the helix (Fig. 2, lower left). The predicted positioning of these residues in the recovered Ala 5* virus, which exhibited a phenotype closer to that of the wild-type virus, restores the relative positioning of the polar residues (Fig. 2, lower right). Our data, taken with this analysis, suggest that the positioning of the polar residues may be important for the function of the E protein. Of particular interest is the potential role of the residues and their positioning for the recently described viroporin activity of coronavirus E proteins. Disruption of the positioning of key residues within the hydrophilic pore may impact the ion channel activity that is likely important for virus assembly.

Figure 2.

Simplified helical wheel diagram illustrating the relative positions of polar residues Gln 15, Cys 23, Thr 27, and Ser 36 in the wild-type and mutant Ala 5 and Ala 5* E proteins. Amino acid numbers are based on the full-length protein. Thr 27 and Ser 36 are shifted one position due to the insertion in Ala 5.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI54704, from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. We thank Ralph Baric for providing us with the MHV infectious clone.

6. REFERENCES

- 1.Bos EC, Luytjes W, van der Meulen HV, Koerten HK, Spaan WJ. The production of recombinant infectious DI-particles of a murine coronavirus in the absence of helper virus. Virology. 1996;218:52–60. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vennema H, Godeke GJ, Rossen JW, Voorhout WF, Horzinek MC, Opstelten DJ, Rottier PJ. Nucleocapsid-independent assembly of coronavirus-like particles by co-expression of viral envelope protein genes. EMBO J. 1996;15:2020–2028. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corse E, Machamer CE. Infectious bronchitis virus E protein is targeted to the Golgi complex and directs release of virus-like particles. J. Virol. 2000;74:4319–4326. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4319-4326.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda J, Maeda A, Makino S. Release of coronavirus E protein in membranevesicles from virus-infected cells and E protein-expressing cells. Virology. 1999;263:265–272. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9955. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raamsman MJ, Locker JK, de Hooge A, de Vries AA, Griffiths G, Vennema H, Rottier PJ. Characterization of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus strain A59 small membrane protein E. J. Virol. 2000;74:2333–23342. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2333-2342.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer F, Stegen CF, Masters PS, Samsonoff WA. Analysis of constructed E gene mutants of mouse hepatitis virus confirms a pivotal role for E protein in coronavirus assembly. J. Virol. 1998;72:7885–7894. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7885-7894.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortego J, Escors D, Laude H, Enjuanes L. Generation of a replication-competent, propagation-deficient virus vector based on the transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus genome. J. Virol. 2002;76:11518–11529. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11518-11529.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuo L, Masters PS. The small envelope protein E is not essential for murine coronavirus replication. J. Virol. 2003;77:4597–4608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4597-4608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson L, McKinlay C, Gage P, Ewart G. SARS coronavirus E protein forms cation-selective ion channels. Virology. 2004;330:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao Y, Lescar J, Tam JP, Liu DX. Expression of SARS-coronavirus envelope protein in Escherichia coli cells alters membrane permeability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;325:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madan V, Garcia MJ, Sanz MA, Carrasco L. Viroporin activity of murine hepatitis virus E protein. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3607–3612. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yount B, Denison MR, Weiss SR, Baric RS. Systematic assembly of a full-length infectious cDNA of mouse hepatitis virus strain A50. J. Virol. 2002;76:11065–11078. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11065-11078.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye Y, Hogue BG. Role of coronavirus envelope (E) protein transmembrane domain in virus assembly. 2005. Manuscript submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mingarro I, Whitley P, Lemmon MA, von Heijne G. Ala-insertion scanning mutagenesis of the glycophorin A transmembrane helix: a rapid way to map helix-helix interactions in integral membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1339–1341. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]