Abstract

Growing evidence supports the hypothesis that soluble, diffusible forms of the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) are pathogenically important in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and thus have both diagnostic and therapeutic salience. To learn more about the dynamics of soluble Aβ economy in vivo, we sampled by microdialysis the brain interstitial fluid (ISF), which contains the most soluble Aβ species in brain at steady state, in >40 wake, behaving APP transgenic mice before and during the process of Aβ plaque formation (age 3–28 months). Diffusible forms of Aβ, especially Aβ42, declined significantly in ISF as mice underwent progressive parenchymal deposition of Aβ. Moreover, radiolabeled Aβ administered at physiological concentrations into ISF revealed a striking difference in the fate of soluble Aβ in plaque-rich (vs. -free) mice: it clears more rapidly from the ISF and becomes more associated with the TBS-extractable pool, suggesting that cerebral amyloid deposits can rapidly sequester soluble Aβ from the ISF. Likewise, acute γ-secretase inhibition in plaque-free mice showed a marked decline of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42, whereas in plaque- rich mice, Aβ42 declined significantly less. These results suggest that most of the Aβ42 that populates the ISF in plaque-rich mice is derived not from new Aβ biosynthesis but rather from the large reservoir of less soluble Aβ42 in brain parenchyma. Together, these and other findings herein illuminate the in vivo dynamics of soluble Aβ during the development of AD-type neuropathology and after γ-secretase inhibition and help explain the apparent paradox that cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 levels fall as humans develop AD.

Introduction

After decades of investigative focus on amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), recent findings have led to a conceptual shift. Emerging evidence suggests that the insoluble amyloid fibrils that comprise plaques may not directly confer neurotoxicity but sequester small, diffusible assemblies of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) that have been shown to potently alter synaptic structure and function (Walsh and Selkoe, 2007). The recognition of Aβ oligomers as highly bioactive assemblies has furthered interest in detecting and analyzing soluble forms of the peptide for mechanistic, diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Although factors other than Aβ dyshomeostasis contribute importantly to the pathogenesis of AD (Pimplikar et al., 2010), virtually all potentially disease-modifying treatments currently under development are focused on decreasing or neutralizing this neurotoxic peptide. Moreover, a reduced CSF level of Aβ42 in subjects with incipient or very early AD is one of the most promising biomarkers. Despite this therapeutic and diagnostic focus, we still lack insight into the in vivo economy of the most soluble forms of Aβ in the brain during the development of AD-type pathology.

Here, we used brain microdialysis in awake and behaving hAPP transgenic mice to gain an understanding of Aβ dynamics before and during the process of Aβ plaque formation. Brain interstitial fluid (ISF) contains the Aβ pool that best reflects the physiological secretion and fate of soluble species. Microdialysis in mouse models of AD and even human subjects is providing important insights into the dynamics of normal ISF Aβ economy (Brody et al., 2008; Cirrito et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2009) and may help identify the earliest, most subtle Aβ changes that occur as AD-type neuropathology begins. Given the power of this in vivo sampling method, we performed hippocampal microdialysis on >40 freely moving APP transgenic mice of increasing age as a model of cerebral Aβ accumulation, and we searched for changes in the quality and quantity of Aβ species as the brain accrues insoluble deposits and undergoes neuronal and glial injury. We systematically analyzed the nature of endogenous Aβ over time using sensitive sandwich ELISAs, immunoprecipitation (IP)/Western blotting (WB), native and denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and size exclusion chromatography (SEC). We then complemented these analyses by assessing the fate of radiolabeled Aβ microinjected at physiological concentrations as a surrogate of newly secreted Aβ, and the results help explain the fall of Aβ42 in the CSF of humans with AD. Taken together, these experiments describe the in vivo dynamics of the most soluble pool of brain Aβ during the process of AD-type amyloid plaque formation.

Materials and Methods

Mice

J20 line carrying huAPP minigene with FAD mutations KM670/671NL and V717F was a kind gift of L. Mucke (Gladstone Institute, UCSF) and was maintained on a C57BL6 × DBA2 background (Mucke et al., 2000). All animal procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice of either sex were used in all experiments.

In vivo Aβ microdialysis

Microdialysis was performed as previously described (Cirrito et al., 2003): intracerebral guides were inserted following the coordinates for left hippocampal placement (bregma −3.1 mm, 2.5 mm lateral to midline, and 1.2 mm below dura at 12° angle). Perfusion buffer (1.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in artificial CSF (in mM: 1.3 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 3 KCl, 0.4 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 122 NaCl, pH 7.35)) was perfused using probes with 35 kDa MWCO membranes (BR-2, Bioanalytical Systems) at flow rates 0.2–1 μl/min with an infusion syringe pump (Stoelting). Microdialysates (ISF) were collected using a refrigerated fraction collector (Univentor). Mice were housed in a “Raturn” cage system (Bioanalytical Systems), which allows mice to resume normal activities, and were subjected to 12 h light/dark cycles.

Interpolated zero-flow method

The in vivo percent recovery was calculated as previously described (Cirrito et al., 2003). ISF was collected from 3 mo and 24 mo tg mice while varying the perfusion rates (PR): 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, and 0.2 μl/min. Aβ levels were measured using the 6E10 Aβ Triplex ELISA (MesoScale Discovery) and the values obtained at each PR were plotted versus the PR. The 100% recovery (i.e. the theoretical maximal amount of exchangeable ISF Aβ species occurring at a zero PR) was calculated by extrapolating back the curve to a zero-flow rate. Then, for each PR, percent recovery was determined by calculating how much %Aβ was captured as compared to the theoretical [Aβ] at zero PR.

Aβ ELISA

For 6E10 Aβ Triplex ELISA, we used the MSD® 96-well MULTI-SPOT® Human (6E10) AbetaTriplex Assay (MesoScale Discovery) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, ISF samples were loaded in duplicates onto MULTI-SPOT® microplates pre-coated with antibodies specific to the C-termini of Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42 and detected with SULFO-TAG™-labeled 6E10 antibody. Light emitted upon electrochemical stimulation was read using the SECTOR® Imager 2400A. For Aβ(1-x) ELISA, we followed a previously described protocol (Townsend et al., 2011). 96-well Nunc MaxiSorp plates were used with 4G8 (to Aβ17–24, Covance) as capture and biotinylated 82E1 (to Aβ1–16, IBL) as detection antibodies. Signals were amplified with AttoPhos (Promega) and measured by Victor2 fluorescent plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Lactate, pyruvate and glycerol measurements

Levels were measured from ISF sampled at 0.2 μl/min using the CMA600 analyzer at the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (YCCI) (sensitivities were: lactate 0.02 mM, pyruvate 2 μM, and glycerol 2 μM).

Mouse brain sample preparation for biochemical analyses

Brains were homogenized using a mechanical Dounce homogenizer with 20 strokes at 4000 rpm in ice-cold TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and protease inhibitors at 4:1 TBS volume:brain wet weight. Homogenate was centrifuged for 30 min at 175,000 g in a 4°C TLA100.2 rotor on Beckman TL 100 (resulting supernatant = “TBS extract”). Pellet was resuspended in 2% SDS using a 18-G needle, heated at 100°C for 10 min and spun at 21,130 g in an Eppendorf 5435 for 10 min (resulting supernatant = “SDS extract”). Pellet was washed twice more in SDS then incubated with 88% formic acid at RT for 2 h. Resulting supernatant (“FA extract”) was diluted 10X with water and lyophilized.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot for Aβ

ISF and brain extracts (except FA extract, which was lyophilized and directly reconstituted in LDS sample buffer prior to loading) were IP’ed with AW8 polyclonal antibody to Aβ (1:100, gift of D. Walsh, BWH) using Protein A (Sigma). For conventional SDS-PAGE, a previously described protocol (Shankar et al., 2008) was followed. Samples were electrophoresed using 12% Bis-Tris gel and MES SDS running buffer (Invitrogen), transferred onto 0.2-μm nitrocellulose, boiled, then blotted using monoclonal antibodies 6E10 (to Aβ3–8, Covance) and 4G8, and visualized using the LiCor Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. For bicine/urea-based SDS PAGE, a previously described system (Klafki et al., 1996) was modified. Briefly, 11% T/2.6% C 8M urea separation gel was overlayered by 11% T/2.6% C 4M urea spacer gel and 4% T/3.3% C comb gel. Gels were run at 12 mA for 1 hr, then 34 W for 3.8 hrs. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes, boiled then blotted with 6E10 with congo red and detected using HRP and ECL Plus WB Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare).

Immunohistochemistry of brain sections

J20 APP tg brains at ages 3 mo, 12 mo and 24 mo were fixed with 10% formalin, paraffin-embedded then sectioned at 8-μm thickness as previously described (Lemere et al., 2002). R1282 polyclonal antibody was used to stain Aβ and the immunoreactivity was visualized using the Vector Elite horseradish-peroxidase ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) with diaminobenzidine (Sigma) as the chromogen.

APP Western blotting

Mouse brains of 3 mo tg, 24 mo tg and wt littermate were homogenized in 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) STEN buffer (in mM: 150 NaCl, 50 Tris, 2 EDTA) using a Teflon® Dounce homogenizer. Brain lysates were loaded onto 4–12% Bis-Tris gel, electrophoresed with MES SDS running buffer, transferred onto 0.2-μm nitrocellulose, then blotted with polyclonal antibody C7 (to full-length APP and its C-terminal fragments) and anti-α-tubulin polyclonal antibody (Thermo Scientific).

Size-exclusion chromatography

TBS extracts (250 μl) or synthetic Aβ (2 ng) were eluted at 0.5 ml/min from a Superdex 200 10/300GL column (GE Healthcare) with 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.5. Resulting 1-ml fractions were lyophilized, reconstituted in LDS sample buffer and heated at 65°C for 10 min. Samples were subjected to WB using 3D6 (to Aβ1–5, gift of Elan) and the LiCor Odyssey Infrared Imaging System or ECL Plus WB Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare).

Compound E treatment

Compound E (3 mg/kg, Axxora) was injected intraperitoneally to mice undergoing microdialysis. Half-lives were calculated according to Cirrito et al (Cirrito et al., 2003).

Radioactivity assay

For ISF experiments, 3 μl of 1 nM [125I]-β-Amyloid(1–40) (PerkinElmer) was injected through a combination infusion cannula and microdialysis probe (IBR-2, Bioanalytical Systems) at 0.2 μl/min. ISF was collected hourly at 0.6 μl/min, paused during the injection, then restarted 1 min after injection. For TBS extractions, 5 μl [125I]-β-Amyloid(1–40) was injected in paired mice (young and old). 1.5 h post injection, brains were harvested for TBS extract preparation. 125I levels were counted using a LS6500 multipurpose scintillation counter (8-min counts).

Clear Native PAGE and subsequent denaturation for SDS PAGE

TBS extracts were prepared from homogenized brains of 24 mo tg and wt littermate, then subjected to non-denaturing Clear Native PAGE, which separates proteins with pI<7 based on their intrinsic charge (Wittig and Schagger, 2005). Briefly, samples were electrophoresed using Native PAGE 4–16% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) with Bis-Tris-HCl, pH 7.0 as anode and Tricine Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 as cathode buffers. Proteins were then transferred onto 0.2-μm PVDF (Millipore), boiled and blotted for Aβ using monoclonal antibodies 2G3 and 21F12 (to Aβ33–40 and Aβ33–42, respectively, gifts of Elan). For subsequent denaturation, we excised two regions of the native PAGE gel following electrophoresis: the >300-kDa and the 80–230-kDa (based on NativeMark™ Unstained Protein Standard (Invitrogen)). The diced gels were heated at 100°C in denaturing LDS sample buffer and supernatants were electrophoresed using 12% Bis-Tris gel and MES SDS running buffer (Invitrogen) for Western-blotting using monoclonal antibody 3D6 (to Aβ1–5, gift of Elan). Proteins were visualized using the Licor Odyssey Infrared Imaging System.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using PRISM (Graphpad Software) for one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test if means were significantly different by ANOVA, or Student’s t-test, as appropriate.

Results

Biochemical analysis of Aβ peptides that remain soluble in the brains of young, behaving hAPP transgenic mice

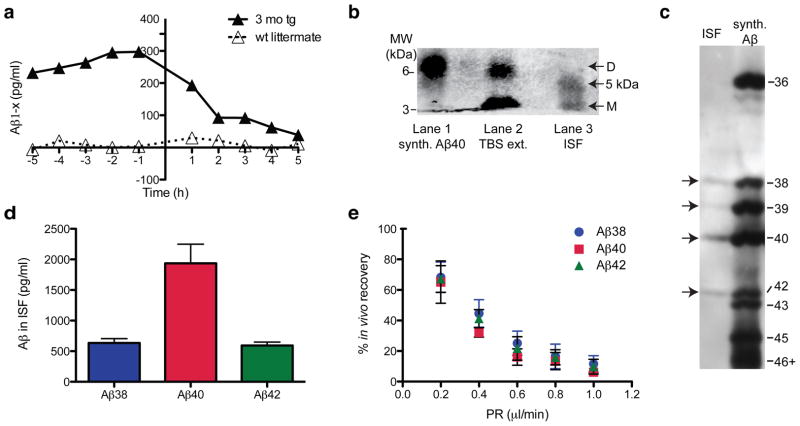

To examine the quality and quantity of Aβ that remains soluble and of low molecular weight in ISF in vivo (termed ISF Aβ herein), we used a microdialysis probe with a 35 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) membrane in mice expressing FAD-mutant human APP (J20 line (Mucke et al., 2000)). When we intraperitoneally injected Compound E, a potent and brain-penetrant γ-secretase inhibitor (Grimwood et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2009), total ISF Aβ captured in microdialysates fell rapidly (t1/2 ~2 h) to baseline (Fig. 1a), showing that most of the ISF Aβ we sample by microdialysis in young mice represents newly synthesized APP cleavage products. To capture the Aβ species that best reflect the physiological levels, we performed microdialysis at a slow perfusion rate of 0.2 μl/min for up to 72 h, as this allows optimal exchange of free Ab into the probe. ISF samples were immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal Aβ antiserum (AW8), and the precipitates were separated by denaturing PAGE and blotted with pooled monoclonal antibodies to the N-terminus (6E10) and mid-region (4G8) of Aβ. The ISF Aβ was separated by conventional SDS-PAGE into two species: a 4 kDa monomer and a novel ~5 kDa species, which ran roughly half the time as a band (Fig. 1b) and the other half as a smear (Fig. 4a). We did not detect dimers (which run at ~6.5 kDa in these gels; Fig. 1b) by IP/WB in the ISF of any of the >40 mice we examined in this study, regardless of age. In vitro (test-tube) microdialysis of synthetic Aβ40 showed that our 35 kDa MWCO membrane allowed passage of dimers; however, their diffusion efficiency was low compared to that of monomers (data not shown), suggesting that the lack of dimers in the ISF samples could be due to the detection limit of the technique. Next, we analyzed the mouse ISF by bicine/urea SDS-PAGE, which electrophoretically separates Aβ peptides of different lengths (Klafki et al., 1996). ISF Aβ was resolved into three principal bands comigrating with synthetic Aβ1–38, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, plus a fourth faint band comigrating with Aβ1–39 (Fig. 1c). Using a multiplex ELISA, we confirmed the bicine/urea gel result that Aβ40 is the most abundant Aβ in ISF (Fig. 1d). The Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in the ISF of young, plaque-free J20 mice was calculated to be ~0.3. Using the interpolated zero flow method (Jacobson et al., 1985; Cirrito et al., 2003) (Fig. 1e), we estimated the total soluble Aβ concentrations in hippocampal ISF of 3 mo tg to be ~1.2 nM.

Figure 1.

ISF Aβ obtained by microdialysis from behaving 3 mo tg J20 hAPP tg mice. (a) Rapid decline of ISF Aβ (t1/2 ~2 h) upon acute γ-secretase inhibition in vivo in 3 mo tg (vs. wt littermate) mice. ISF sampled hourly at 1 μl/min; Compound E injected at time = 0 h. (b, c) ISF collected at 0.2 μl/min were IP’ed with AW8 Aβ antiserum and subjected to two types of SDS-PAGE: (b) Conventional SDS-PAGE separates ISF Aβ into a ~4 kDa (monomers) and a ~5 kDa Aβ-immunoreactive species (lane 3). No dimers were detected in ISF (but can be seen in the TBS-extract of a 24 mo tg (lane 2) or in synthetic Aβ (lane 1)). (WB: 6E10+4G8) (c) Bicine/urea SDS-PAGE resolved ISF Aβ into 3 bands comigrating with synthetic Aβ1–38, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, plus a fourth faint band corresponding to Aβ1–39. (WB: 6E10) (d) Using 6E10 Aβ triplex ELISA, we quantified Aβx-38, Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 in ISF. Mean ± s.e.m.: 635 ± 70, 1937 ± 311 and 592 ± 58 pg/ml, respectively; n = 7 mice. (e) Interpolated zero flow method. Mean ± s.e.m.; n = 3–4 mice.

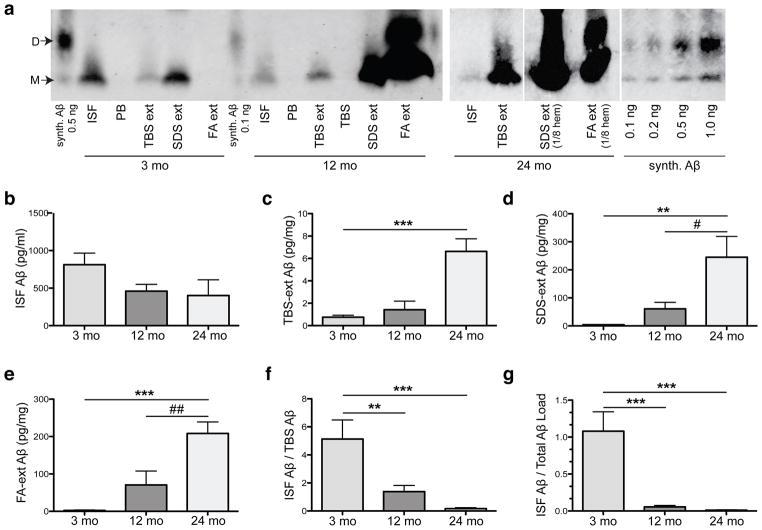

Figure 4.

Aβ in all pools of brain parenchyma accrue with age while those that remain diffusible in the ISF declines. (a) Representative IP-WB’s of Aβ species in four pools: (1) ISF, and (2) TBS-extracted (“TBS ext”), (3) SDS-extracted (“SDS ext”) and (4) FA-extracted (“FA ext”) pools from brains of the same mice right after microdialysis. All pools (except the FA ext, which was lyophilized and straight-loaded onto the gel) were IP’ed with AW8 and blotted with 6E10 and 4G8. Synthetic Aβ run alongside for quantification. PB (Perfusion buffer) and TBS (Tris-buffered saline) were IP’ed as negative controls. (b–e) Quantification of IP-WB’s from 21 mice shows (b) ~50% decrease in absolute values of ISF Aβ between 3 mo and 12 mo (NS by 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test) with a sharp (c–e) rise in TBS, SDS and FA-extracted Aβ (pg per mg wet brain tissue). (f, g) Ratios of ISF to TBS-soluble Aβ (f) or to total parenchymal Aβ (g) calculated for each mouse and shown as mean ratio ± s.e.m.; n = 7 mice per group. Aβ quantified by Licor Odyssey® imaging and analyzed by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni test: **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. 3 mo; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. 12 mo.

ISF Aβ decreases with age as Aβ in brain parenchyma accrues

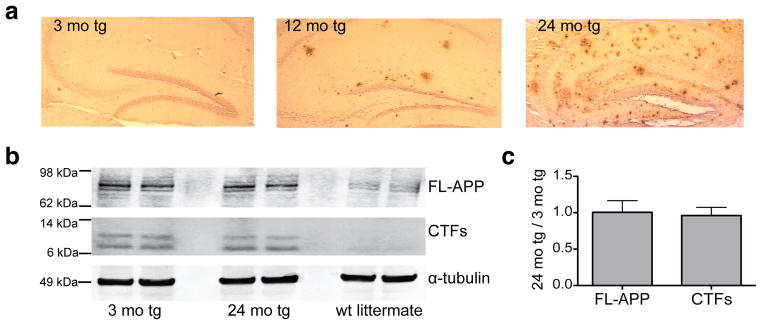

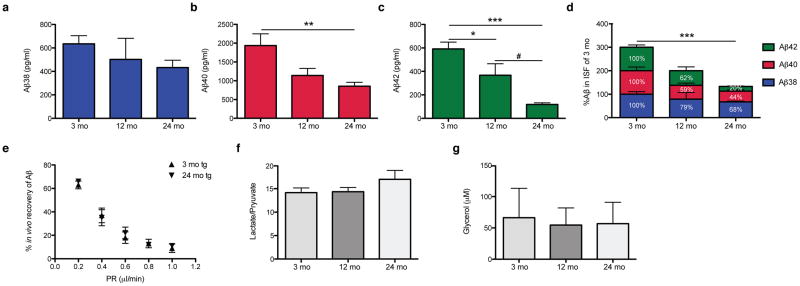

To elucidate how amyloid plaque development and maturation affect the steady-state levels of brain ISF Aβ, we sampled ISF from the hippocampi of living J20 tg mice at three ages: pre-plaque (~3 mo), early plaque deposition (~12 mo), and abundant and mature plaque deposition (~24 mo) (Fig. 2a). The levels of holoAPP and its C-terminal fragments generated by β- and α-secretases were constant over the 3–24 mo ISF sampling period (Fig. 2b), suggesting that Aβ production via APP proteolytic processing does not change appreciably over age. As quantified by multiplex Aβ ELISA, all three Aβ peptides measured in ISF (Aβx-38, Aβx-40 and Aβx-42) decreased over time to levels that were significantly reduced by 24 mo (Figs. 3a–c show absolute values; Fig. 3d shows proportional levels). As the individual peptides fell to different degrees, the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in the ISF shifted from 0.3 at 3 mo to 0.13 at 24 mo. We estimated that the total soluble Aβ concentrations in hippocampal ISF decreased from ~1.2 nM in 3 mo tg to ~0.5 nM in 24 mo tg (see Table 1 for concentrations of individual Aβ peptides in hippocampal ISF of 3 mo and 24 mo tg). The similar % recovery of microdialyzable Aβ at 3 and 24 mo (measured at 5 flow rates) indicates that the age-dependent decrease in ISF Aβ is not due to technical issues with the microdialysis system (Fig. 3e). We measured analytes other than Aβ present in the ISF to see whether they are also altered with age, in particular, lactate, pyruvate and glycerol. The ratio of lactate to pyruvate is an established marker of the redox state of cells; glycerol is an integral component of cellular membranes, and changes in its level can reflect degradation of membranes (Ungerstedt and Rostami, 2004). Neither the lactate-to-pyruvate ratio nor the level of glycerol in ISF changed significantly during our 3–24 mo sampling period (Fig. 3f–g), suggesting that the decrease in Aβ is not associated with altered intermediary metabolism or perturbation of cell membrane integrity.

Figure 2.

Amyloid plaques develop and mature with age in J20 APP tg mice, without significant changes in full-length APP or in its proteolytic processing by β- or α-secretases. (a) Hippocampal sections from fixed J20 APP tg brain were paraffin-embedded, then stained for Aβ using R1282 polyclonal antibody. 3 mo tg sections were virtually plaque-free, whereas some plaques had formed by 12 mo. By 24 mo, abundant diffuse and dense-core plaques populated the hippocampus. (b) Representative blot of brain lysates of 3 mo tg, 24 mo tg and wt littermate loaded onto denaturing SDS PAGE, then blotted for full-length APP (FL-APP) and its C-terminal fragments (CTFs) (WB: polyclonal C7) or to α-tubulin (WB: polyclonal tubulin-alpha). (c) Summary ratios of immunoreactive signals at 24 mo over 3 mo tg mice, for FL-APP and CTFs normalized to the α-tubulin signal. n = 3 mice per group; signal quantification by Licor Odyssey®.

Figure 3.

Levels of soluble ISF Aβ <35-kDa in the brain fall with age. (a–d) ISF was sampled from the hippocampi of 3 mo (pre-plaque), 12 mo (early plaque deposition), and 24 mo (abundant, mature plaques) J20 tg mice. Using Aβ triplex ELISAs, we found that Aβx-38 (a), Aβx-40 (b), and Aβx-42 (c) all decreased with age (means ± s.e.m.; n = 7, 4, 7 mice at 3, 12 and 24 mo, respectively). One-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. 3 mo values; #P < 0.05 vs. 12 mo values. (d) Proportional levels of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42, where each peptide was normalized to its level at 3 mo. Aβ42 declined the most (80% by 24 mo vs. 3 mo). ***P value < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA with age as a variant. (e) At 0.2 μl/min, the perfusion rate used to collect all ISF samples in Figs. 3–4, we obtained comparable % recoveries of microdialyzable Aβ in the two extreme ages (~63 ±3% in 3 mo tg and ~66 ±2% in 24 mo tg; means ± s.e.m.; n = 3–4 mice). (f–g) Ratios of lactate to pyruvate (f) and glycerol levels (g) in the ISF microdialysates were not altered with age (means ± s.e.m.; n = 3–8 mice).

Table 1.

Theoretical concentrations of microdialyzable ISF Aβ in vivo at zero flow rate

| Aβ38 (pg/ml) | Aβ40 (pg/ml) | Aβ42 (pg/ml) | Aβ42:Aβ40 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mo | 24 mo | 3 mo | 24 mo | 3 mo | 24 mo | 3 mo | 24 mo | |

| [ISF Aβ] of J20 tg mice | 930 | 658 | 2975 | 1231 | 880 | 166 | 0.30 | 0.13 |

Concentrations of endogenous hippocampal ISF Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 were calculated by extrapolating the curves generated from the interpolated zero-flow method to zero PR (see Fig. 5). Ratios of Aβ42/Aβ40 in the ISF of 3 mo and 24 mo tg were calculated to be ~0.30 and 0.13, reflecting a higher drop of Aβ42 vs. Aβ40 in 24 mo tg mice.

Next, we sought to identify the pathophysiological relationship between ISF Aβ and the accrual of increasingly less soluble Aβ in brain parenchyma during the development of AD-type neuropathology. Using a sensitive IP/WB method (Walsh et al., 2002; Shankar et al., 2008), we compared the quantity and type of Aβ in ISF obtained in vivo with three pools of brain parenchymal Aβ isolated from the same mice right after the dialysis: Tris-buffered saline (TBS) extract (traditionally defined as the “soluble Aβ fraction”), detergent (SDS) extract (aggregated and membrane-associated Aβ), and formic acid (FA) extract (Aβ from highly insoluble deposits, including plaque cores (Masters et al., 1985; Selkoe et al., 1986)). As reported previously in the J20 line and other APP tg mice (Johnson-Wood et al., 1997; Hsia et al., 1999; Mucke et al.; Kawarabayashi et al., 2001; Shankar et al., 2009), we observed an age-dependent rise in levels of all three pools of parenchymal Aβ (Fig. 4a). Both the SDS and FA extracts rose sharply with age (Fig. 4a, d–e). Aβ in the TBS extract did not rise substantially until 24 mo, an age at which we regularly observed SDS-stable dimers in this fraction (Fig. 4a, c). In contrast to these age-dependent rises in parenchymal Aβ, there was a decline in the ISF. We observed a 50% decrease in total absolute ISF Aβ levels between 3 and 12 mo (Fig. 4b), before there was an appreciable rise in the TBS extract (Fig. 4c). We next analyzed the values in each mouse to determine what portion of its TBS-soluble Aβ remains dialyzable in vivo, and observed a 5-fold decline in the ISF/TBS ratio between 3 and 12 mo (Fig. 4f). When normalized to total brain parenchymal Aβ, the relative ISF level declined even more (Fig. 4g). Thus, all Aβ pools in brain parenchyma rise with age, while that which remains diffusible in ISF in vivo sharply declines.

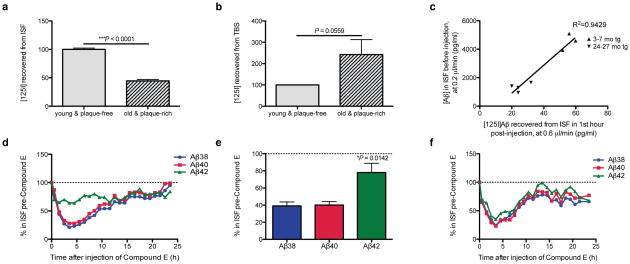

Altered dynamics of soluble Aβ in plaque-rich vs. plaque-free mice

Sampling the ISF at slower perfusion rates (which allows more efficient dialysis of ISF solutes) revealed age-dependent changes in ISF Aβ (Fig. 5). In particular, this method revealed significantly decreased diffusion of endogenous Aβ40 and Aβ42 into the microdialysis probe in 24 mo than 3 mo mice. To better understand the basis for this marked decrease in recovery of diffusible ISF Aβ in the presence of abundant plaques, we approximated the fate of newly secreted Aβ molecules by exogenously administering radiolabeled soluble Aβ. We acutely injected soluble synthetic [125I]Aβ1–40 at a physiological concentration (1 nM) via a small cannula attached to the microdialysis probe into the hippocampal ISF of either age 3–7 mo (plaque-free) or age 24–27 mo (plaque-rich). We then measured the ability to recover the radiolabeled peptide from the ISF by microdialysis. From the ISF of the plaque-rich mice, we recovered only 45% of the injected peptide that was recovered from the ISF of plaque-free mice (p<0.0001) (Fig. 6a). The amounts of the injected [125I]Aβ that were recovered at the two ages correlated well with the respective endogenous Aβ concentrations in the ISF before injection: the [125I]Aβ levels observed in the first hour and the endogenous Aβ levels just before injection were both high in young mice and both low in old mice (Fig. 6b), indicating that the acutely injected radiopeptide achieves a similar equilibrium as the endogenous Aβ has at steady state. We hypothesized that in plaque-rich mice, the acutely administered monomer is more readily incorporated into their abundant Aβ deposits and thus is less recoverable in the ISF. To address this idea, we quantified the radioactivity retained in the TBS extracts of brain. We saw a substantially higher amount of the fresh, exogenous radiopeptide retained in the TBS extracts of the older mice (Fig. 6c). In the short time frame we conducted these analyses (i.e., the first 90 minutes after administration), we did not detect significant levels of radioactivity in the SDS and FA fractions. Taken together, these results suggest that in plaque-burdened mice, newly generated soluble Aβ released into the ISF readily accrues onto parenchymal deposits, accounting for its lower steady-state level in the ISF.

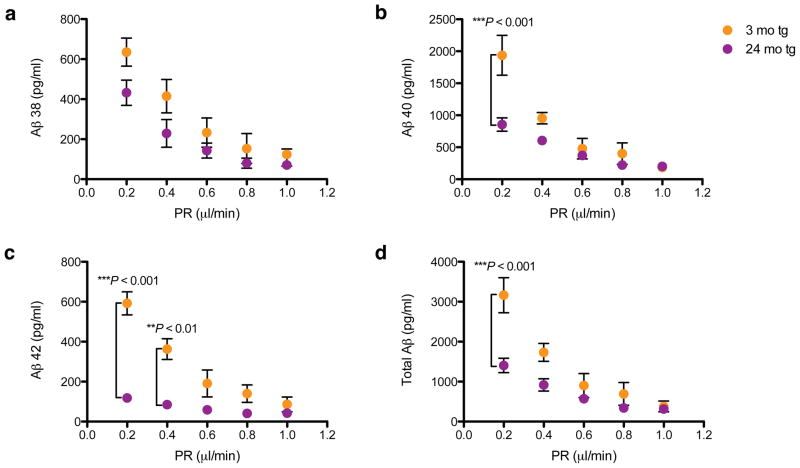

Figure 5.

Microdialysis at slower perfusion rates reveals age-dependent changes in ISF Aβ. ISF were collected from hippocampi of 3 mo (plaque-free) and 24 mo (plaque-rich) tg mice while varying the perfusion rate (PR). Samples were then quantified using 6E10 Aβ triplex ELISA. (a–c) At PR 1 μl/min, no age-dependent changes in all 3 peptides were detectable; however, at slow PRs (especially 0.2 μl/min), significant differences were noted, particularly in Aβ40 and Aβ42. (d) Sum of the three Aβ peptides measured (total Aβ). Values = means ± s.e.m., n = 3–7 mice; P values by 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni test.

Figure 6.

Dynamic shift in the in vivo economy of Aβ once plaques develop. (a–c) Soluble synthetic [125I]Aβ1–40 at a physiological concentration (1 nM) was injected intra-hippocampally via a small cannula on the microdialysis probe in wake, behaving mice at 3–7 mo (plaque-free) or 24–27 mo (plaque-rich), and radioactivity was recovered in the ISF by microdialysis (a) and from the TBS extracts of the brains (b). Means normalized to amounts in the plaque-free mice (100%) ± s.e.m.; n = 3–4 mice per group; P values are 1-tailed t-tests vs. 3–7 mo. (c) Amount of [125I]Aβ recovered in the first hour of injection plotted versus the endogenous Aβ levels sampled from same mice before injection. (d–f) ISF Aβ42 is minimally affected by Compound E in plaque-rich mice. (d) Representative graph of hourly ISF Aβ levels after Compound E injection (0 hr) into 24 mo plaque-rich mice while collecting their brain ISF at 0.6 μl/min. Levels were normalized to levels of each Aβ species before injection. (e) Quantification of the individual ISF Aβ peptides in 24 mo plaque-rich mice for the first 5 hr post-injection (means ± s.e.m., n = 3 mice; P value is by 1-way ANOVA). (f) Hourly ISF Aβ levels after Compound E injection (0 hr) in a 3 mo plaque-free tg mouse.

The level of ISF Aβ42 in plaque-rich mice is minimally affected by acute γ-secretase inhibition

To assess whether the ISF Aβ we measure in plaque-rich older mice also represents recent APP cleavage products, as we had determined in young mice (Fig. 1a), we acutely inhibited γ-secretase in vivo with Compound E. There was a rapid decline of Aβ38 and Aβ40 (~60% fall in the first 3 h; t1/2 ~1.9 h and ~2.3 h, respectively), whereas Aβ42 declined significantly less (~20% fall)(Fig. 6d–e). In contrast, all 3 peptides fell together in young plaque-free mice during the first 5 h after shutting down new production with Compound E (Fig. 6f). As Aβ42 is the species reported to accumulate much more into plaques than the other, more abundantly generated Aβ peptides in both AD patients and APP mice (Iwatsubo et al., 1994; Johnson-Wood et al., 1997), these results suggest that most of the soluble Aβ42 peptide that populates the ISF pool in plaque-rich mice is not derived primarily from new Aβ biosynthesis but rather from the large reservoir of less soluble Aβ42 in the brain parenchyma. The results also indicate that acute γ-secretase inhibition is less effective in lowering Aβ42 in plaque-rich brains.

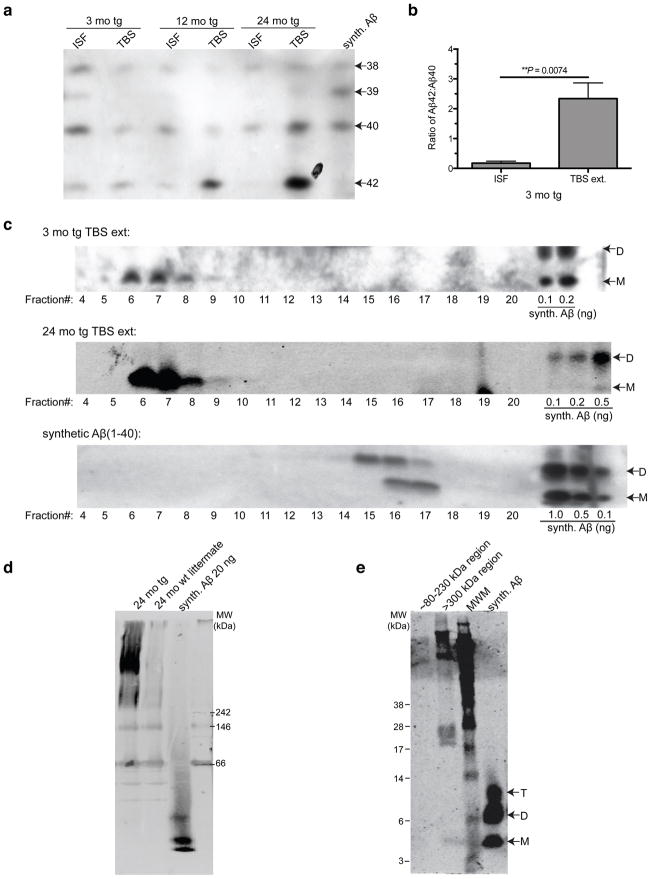

Saline-extractable Aβ of brain parenchyma in its native form appears to exist principally in assemblies >500 kDa

Bicine/urea SDS-PAGE gels showed that the Aβ peptide distribution differed between the ISF and TBS-extracted pools at all ages (Fig. 7a). Even at age 3 mo, when the brain has virtually no plaques, Aβ40 was the primary Aβ species in ISF while in the TBS-extracted pool, Aβ42 was already the more abundant peptide at steady state, despite the fact that it is generated in much lower amounts than Aβ40 (Fig. 7a). Accordingly, the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio differed markedly between the ISF (low ratio) and TBS extract (very high ratio) (Fig. 7b). This stark difference led us to question the general assumption that the brain Aβ pool which comes into solution upon mechanical homognization in physiological buffers represents the truly soluble pool (McLean et al., 1999; Walsh and Selkoe, 2004; Shankar et al., 2009). We performed non-denaturing SEC on the TBS extract and subjected the resultant SEC fractions to SDS-PAGE for WB analysis. Surprisingly, most Aβ in the TBS extracts of plaque-free (3 mo tg) mice eluted in the void volume of a Superdex 200 SEC column (suggesting a MW >500 kDa), and this material ran principally as monomers when electrophoresed on a denaturing gel (Fig. 7c, fractions 6–7). The SEC elution profiles of TBS extracts from 3 mo and 24 mo tg mice were similar and differed sharply from that of synthetic Aβ40 peptide alone (Fig. 7c). In accord, Aβ in TBS extracts from 24 mo tg ran as an aggregated, high MW complex on a Clear Native PAGE gel, whereas synthetic Aβ40 ran close to the dye front (Fig. 7d). Excision of the >300 kDa region and subsequent denaturation in LDS sample buffer yielded lower MW Aβ species, including monomers (Fig. 7e).

Figure 7.

Saline brain extracts of tg mouse exists principally in assemblies >500 kDa in native form. (a) Bicine/urea SDS-PAGE shows the principal Aβ peptides present and their relative expression levels in ISF and TBS extracts of 3 mo, 12 mo and 24 mo tg mice. (IP: AW8, WB: 6E10) (b) Quantification (by ImageJ software) of Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios in plaque-free 3 mo tg mice (P value by 1-tailed t-test; n = 3 each). (c) Non-denaturing SEC of TBS extracts of 3 mo tg and 24 mo tg performed on a Superdex 200 SEC column followed by SDS-PAGE of each SEC fraction. Synthetic Aβ40 run on the same SEC column for comparison. (WB: 3D6) (d) TBS extracts from 24 mo tg and its wt littermate subjected to Clear Native PAGE and blotted for Aβ. (WB: 2G3+21F12) (e) Excision of the >300-kDa region and subsequent electrophoresis by denaturing SDS-PAGE showed that this high MW material is disassembled into low MW SDS-stable Aβ species. (WB: 3D6)

Discussion

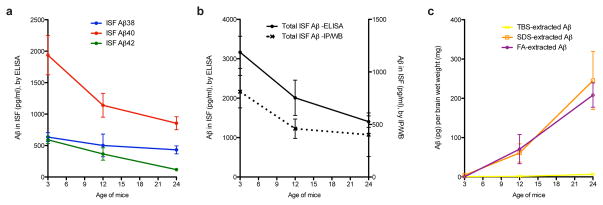

Although factors other than Aβ dyshomeostasis contribute importantly to the pathogenesis of AD (Pimplikar et al., 2010), most potentially disease-modifying treatments currently under development are focused on decreasing or neutralizing this neurotoxic peptide. Moreover, a reduced CSF level of Aβ42 in subjects with incipient or very early AD is one of the most promising biomarkers. Despite this therapeutic and diagnostic focus, we still lack insight into the in vivo economy of soluble Aβ in the brain as AD-type pathology forms. Here, we used the powerful method of brain microdialysis in awake, behaving hAPP transgenic mice to gain understanding of the dynamics of the most soluble forms of Aβ in the hippocampus before and during the process of Aβ plaque formation. Our results show that Aβ peptides which remain soluble and of low molecular weight in the interstitial fluid in vivo decrease significantly – both absolutely (Figs. 3–5 and 7a) and especially in relation to the soluble Aβ extractable from brain membranes (Fig. 4d) – as plaques accumulate. Aβ42 decreases the most among the three major Aβ peptides in the ISF; in accord, Aβ42 rises the most in the less soluble Aβpools in the brain parenchyma (Figs. 3 and 7a), keeping with its documented primary role in oligomerization and plaque formation. (Figs. 8a–c provide summaries of the temporal changes documented in this study.)

Figure 8.

Summary of the temporal changes in the four Aβ brain pools. (a) Decreases with age in all three in vivo ISF Aβ peptides measured by 6E10 Aβ triplex sandwich ELISA (see Fig. 3 for details). (b) The fold-decrease measured by ELISA (significant between 3 and 24 mo by two-way ANOVA; see Fig. 2) is comparable to the fold-decrease measured by IP/WB (though the latter was not significant by one-way ANOVA; see Fig. 4 for details). The total amount measured by IP/WB analysis method was only ~30% of the total amount measured by ELISA. (c) IP/WB analysis of Aβ in brain tissue. By ~24 mo, there was a steep increase in insoluble (SDS- and FA-extracted) Aβ. The TBS-extracted Aβ from the same mice did not rise until 24 mo and then only very slightly. Values = means ± s.e.m. from Figs. 3 and 4.

Of special clinical relevance is that our discovery of an age-dependent decrease in ISF Aβ42 may be analogous to the widely-documented selective decrease in soluble Aβ42 in human (AD) CSF (Motter et al., 1995). In humans, CSF levels of Aβ42 appear to relate inversely to amyloid plaque burden, degree of brain atrophy and severity of cognitive deficits in humans (Motter et al., 1995; Fagan et al., 2009; Shaw et al., 2009). Our dynamic studies of the change in endogenous ISF Aβ and of the fate of radiolabeled Aβ before vs. after plaque initiation offer strong evidence from controlled animal experiments for the hypothesis that soluble Aβ42 in humans falls in the CSF because it is sequestered into increasingly insoluble parenchymal deposits as AD develops.

What are the driving forces leading to the sharp decline of diffusible Aβ species as AD-like pathology progresses with age? The constant levels of both full-length APP and the CTFs generated by α- and β-secretases suggest that the fall we observe is not due to a decrease of cellular production of Aβ. We also saw no evidence for a perturbation of cell membrane integrity, a change in an indicator of intermediary metabolism, or altered spontaneous behavior (eating, exploring, grooming, etc.) in the mice, arguing against general cytotoxicity or cell death as an explanation for the drop. Thus, we obtained no evidence that decreased neuronal activity or decreased Aβ production explains the drop in soluble ISF Aβ as mice accrue amyloid deposits. Rather, the decrease in ISF Aβ occurred simultaneously with rises of insoluble Aβ in the SDS- and FA-extractable pools (Figs. 3–4). Furthermore, the distinct dispositions of soluble radiolabeled Aβ injected at physiological concentrations directly into the ISF in plaque-free vs. plaque-rich animals provide insight into a shift in Aβ economy: in plaque-rich mice, Aβ becomes rapidly less diffusible and more associated with the loosely membrane-bound (TBS-extractable) pool (Fig. 6). This dynamic shift leads us to hypothesize that once an Aβ peptide binds to membranes and/or plaques, it is sequestered there and becomes less diffusible, at least temporarily, leading to decreased recovery during microdialysis, consistent with a report of lengthened Aβ clearance time in old vs. young APP transgenic mice (Cirrito et al., 2003).

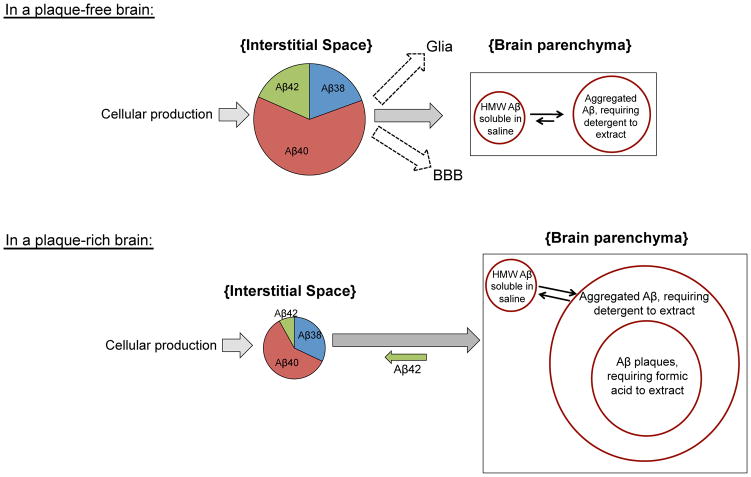

Indirect evidence for a converse pathway suggests that such membrane association is not irreversible. Our finding that upon acute γ-secretase inhibition there was significantly less fall in ISF specifically of Aβ42 (which is much more abundant in plaques) suggests that plaques contribute to a dynamic equilibrium between soluble and insoluble Aβ42 pools in the brain and thus help regulate the steady state of ISF Aβ in aged mice (see Figure 9 for a model). This concept is consistent with evidence that amyloid plaques in APP transgenic mice appear to act as a local reservoir of “loosely-associated” Aβ that can diffuse from plaques and populate a halo of oligomeric and monomeric Aβ immediately surrounding the amyloid core (Spires et al., 2005; Koffie et al., 2009). It will be interesting to see whether acute alteration of one particular Aβ pool (e.g., via agents such as antibodies that can selectively bind aggregated Aβ or agents that only sequester the fully soluble ISF pool) will have transient or lasting effects on the equilibrium maintained among the Aβ pools.

Figure 9.

A hypothetical model of Aβ in vivo dynamics before vs. after plaque formation based on data herein. Several factors contribute to steady-state Aβ levels in brain ISF. There is a constant supply of Aβ in the ISF pool generated by new APP processing (Aβ40 ≫ Aβ38 = Aβ42 > Aβ39), and this generation appears to change little with age. ISF Aβ can be proteolytically degraded, cleared locally by glia and/or transported across the blood brain barrier (BBB). Soluble Aβ starts aggregating at an early age in brain parenchyma, as evidenced by the >500-kDa TBS-extractable pool as well as an SDS-extractable pool in 3 mo, plaque-free mice. The most abundant pools in a plaque-free brain are the ISF pool and the SDS-extractable pool. In a plaque-rich brain, however, equilibrium between pools is greatly altered by the overwhelming amount of aggregated Aβ, which act as a sink, thereby diminishing the steady-state ISF pool. Plaques may also act as a contributor to the ISF pool, where Aβ42, the most abundant peptide in plaques (and also the most decreased in the ISF) diffuses back into the ISF.

Aβ in aqueous extracts of homogenized cerebral cortex has been termed by our group and others as the “soluble Aβ” pool and thought to be derived from ISF and cytosol, not necessarily from particulates such as amyloid deposits (Gravina et al., 1995; Lue et al., 1999; McLean et al., 1999; Walsh and Selkoe, 2004; Shankar et al., 2009); the rise in this pool was thought to reflect a rise in diffusible Aβ in vivo. However, we show here that Aβ peptides in aqueous parenchymal extracts differ significantly in quality and quantity from those that remain of low MW in the ISF pool. Furthermore, using non-denaturing SEC and native gels, we show that much native Aβ in the TBS extracts of APP transgenic mouse brains, even at a pre-plaque age of 3 mo, exists in assemblies that size at >500 kDa, extending similar data on the aqueous extracts of AD brains (Shankar et al., 2008). Thus, aqueous extracts of Aβ may principally reflect aggregated Aβ peptides bound to cell membranes (in young mice) and to membranes and plaques (in older mice) but which remain water-extractable.

Given this new understanding that aqueous extracts of brain may not reflect the truly diffusible Aβ species in vivo, it will be important to examine the nature of synaptotoxicity in the different Aβ pools, including the ISF pool and the TBS-extracted pool, which is currently thought to principally contain the toxic oligomeric species. Interestingly, we have not detected SDS-stable dimers in any of our ISF microdialysates to date, which could be due in part to the limits of detection. Using a test-tube model of our microdialysis technique, we found that synthetic Aβ dimers (~8 kDa) crossed over the 35 kDa MWCO membrane; however, the diffusion efficiency of dimers was poor in comparison to that of monomers (data not shown). Therefore, we cannot exclude the existence of low levels of soluble dimers in the ISF of hAPP transgenic mice. On the other hand, our results may instead suggest that soluble dimers and other oligomers do not actually exist per se in the most diffusible brain pool (ISF); rather, newly formed oligomers (with their exposed hydrophobic amino acids) may distribute quickly onto hydrophobic surfaces (cell membranes and/or amyloid deposits).

As regards the implications of our findings for the pathophysiology of AD, it will be important in future studies to attempt to detect any bioactivity of the ISF Aβ pool at the different plaque stages of APP transgenic mice. Whereas the ISF of young, plaque-free mice acts as a reservoir for mainly the acute cellular production of Aβ, ISF in plaque-rich mice seems to be a reservoir for both new Aβ production and Aβ that diffuses from membrane- and plaque-bound deposits (as evidenced by the finding that ISF Aβ42 levels do not fall significantly upon acute inhibition of γ-secretase). Whether the Aβ42 that comes off of parenchymal deposits into the ISF is pathogenically important (as compared to Aβ in the ISF of plaque-free brains) will be important to determine.

In conclusion, these dynamic analyses provide unique insights into the generation of first fully soluble and then increasingly less soluble Aβ species during age-related accrual of AD-type amyloid deposits in living animals. Based on the usefulness of these preclinical data, we suggest a provocative approach toward potentially extending such studies to humans. Patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), which is typified by a clinical triad of subacutely developing dementia, incontinence and gait ataxia (Relkin et al., 2005; Shprecher et al., 2008), are frequently offered a neurosurgical procedure by which a ventriculoperitoneal shunt is inserted to chronically drain the excess ventricular CSF to the peritoneal cavity and thus potentially improve the patients’ NPH symptoms. Several studies of simultaneously obtained cortical biopsies have shown that some or many such shunted patients show amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles indistinguishable from those in typical AD patients (Del Bigio et al., 1997; Bech et al., 1999; Golomb et al., 2000; Hamilton et al., 2010). This co-occurrence suggests that obtaining IRB approval to perform a brief (12–24 h) placement of a microdialysis probe at the time of an NPH shunt placement could enable in vivo analysis of ISF Aβ peptides in humans with varying degrees of Aβ deposition. We propose that such controlled clinical research studies in appropriate patients be considered in order to obtain direct information about the economy of the most soluble species of brain Aβ (those in ISF) as a function of the level of cerebral β-amyloidosis in humans.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Meghana Kamineni and Isaac Ng for technical assistance and to members of the Selkoe laboratory for critical comments. We thank Lennart Mucke (UCSF) for kindly providing J20 mice, Dominic M. Walsh (BWH) for AW8 antibody, Elan, plc (South San Francisco, CA) for 3D6, 2G3 and 21F12 antibodies, and Cynthia A. Lemere and Jeffrey L. Frost (BWH) for assistance with immunohistochemistry. This work is supported by NIH grant AG027443 (D.J.S.), Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center Pre-doctoral Training Fellowship and James L. Rappaport Fellowship (S.H.), AG017574-08S1 (O.Q.-M.), NIH AG13956 (D.M.H.), K01 AG029524 (J.C.R.), and NCRR- CTSA grant UL1 RR024139 (YCCI).

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement: DJS is a founding scientist and consultant of Elan, plc.

References

- Bech RA, Waldemar G, Gjerris F, Klinken L, Juhler M. Shunting effects in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus; correlation with cerebral and leptomeningeal biopsy findings. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999;141:633–639. doi: 10.1007/s007010050353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody DL, Magnoni S, Schwetye KE, Spinner ML, Esparza TJ, Stocchetti N, Zipfel GJ, Holtzman DM. Amyloid-beta dynamics correlate with neurological status in the injured human brain. Science. 2008;321:1221–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1161591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Kang J-E, Lee J, Stewart FR, Verges DK, Silverio LM, Bu G, Mennerick S, Holtzman DM. Endocytosis is required for synaptic activity-dependent release of amyloid-beta in vivo. Neuron. 2008;58:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, May PC, O’Dell MA, Taylor JW, Parsadanian M, Cramer JW, Audia JE, Nissen JS, Bales KR, Paul SM, DeMattos RB, Holtzman DM. In vivo assessment of brain interstitial fluid with microdialysis reveals plaque-associated changes in amyloid-beta metabolism and half-life. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8844–8853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08844.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bigio MR, Cardoso ER, Halliday WC. Neuropathological changes in chronic adult hydrocephalus: cortical biopsies and autopsy findings. Can J Neurol Sci. 1997;24:121–126. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100021442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Head D, Shah AR, Marcus D, Mintun M, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid Abeta(42) correlates with brain atrophy in cognitively normal elderly. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:176–183. doi: 10.1002/ana.21559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomb J, Wisoff J, Miller DC, Boksay I, Kluger A, Weiner H, Salton J, Graves W. Alzheimer’s disease comorbidity in normal pressure hydrocephalus: prevalence and shunt response. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:778–781. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.6.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos LJ, Younkin LH, Suzuki N, Younkin SG. Amyloid β protein (Aβ) in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7013–7016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwood S, Hogg J, Jay M, Lad A, Lee V, Murray F, Peachey J, Townend T, Vithlani M, Beher D. Determination of guinea-pig cortical ?-secretase activity ex vivo following the systemic administration of a ?-secretase inhibitor. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1002–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R, Patel S, Lee EB, Jackson EM, Lopinto J, Arnold SE, Clark CM, Basil A, Shaw LM, Xie SX, Grady MS, Trojanowski JQ. Lack of shunt response in suspected idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus with Alzheimer disease pathology. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:535–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.22015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina H, Ihara Y. Visualization of A beta 42(43) and A beta 40 in senile plaques with end-specific A beta monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is A beta 42(43) Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson I, Sandberg M, Hamberger A. Mass transfer in brain dialysis devices—a new method for the estimation of extracellular amino acids concentration. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1985;15:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Motter R, Hu K, Gordon G, Barbour R, Khan K, Gordon M, Tan H, Games D. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Aβ42 deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997;94:1550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J-E, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, Lee JJ, Smyth LP, Cirrito JR, Fujiki N, Nishino S, Holtzman DM. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2009;326:1005–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Saido TC, Shoji M, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:372–381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klafki HW, Wiltfang J, Staufenbiel M. Electrophoretic separation of betaA4 peptides (1–40) and (1–42) Analytical Biochemistry. 1996;237:24–29. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffie RM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Hashimoto T, Adams KW, Mielke ML, Garcia-Alloza M, Micheva KD, Smith SJ, Kim ML, Lee VM, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL. Oligomeric amyloid beta associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4012–4017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemere CA, Spooner ET, Leverone JF, Mori C, Clements JD. Intranasal immunotherapy for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Escherichia coli LT and LT(R192G) as mucosal adjuvants. Neurobiology of Aging. 2002;23:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, Beach T, Kurth JH, Rydel RE, Rogers J. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C, Cherny R, Fraser F, Fuller S, Smith M, Vbeyreuther K, Bush A, Masters C. Soluble pool of Aβ amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 1999;46:860–866. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::aid-ana8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motter R, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Kholodenko D, Barbour R, Johnson-Wood K, Galasko D, Chang L, Miller B, Clark C, Green R, et al. Reduction of beta-amyloid peptide 42 in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:643–648. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu G-Q, Mallory M, Rockenstein E, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Johnson-Wood K, Mcconlogue L. High-Level Neuronal Expression of Abeta 1–42 in Wild-Type Human Amyloid Protein Precursor Transgenic Mice: Synaptotoxicity without Plaque Formation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:4050. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimplikar SW, Nixon RA, Robakis NK, Shen J, Tsai L-H. Amyloid-independent mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14946–14954. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4305-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P, Bergsneider M, Black PM. Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:S4–16. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000168185.29659.c5. discussion ii–v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, Abraham CR, Podlisny MB, Duffy LK. Isolation of low-molecular-weight proteins from amyloid plaque fibers in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1986;146:1820–1834. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb08501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G, Leissring M, Adame A, Sun X, Spooner E, Masliah E, Selkoe D, Lemere C, Walsh D. Biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model reveals the presence of multiple cerebral Abeta assembly forms throughout life. Neurobiol Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ Initiative AsDN . Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:403–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprecher D, Schwalb J, Kurlan R. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:371–376. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0058-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires TL, Meyer-Luehmann M, Stern EA, McLean PJ, Skoch J, Nguyen PT, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT. Dendritic spine abnormalities in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice demonstrated by gene transfer and intravital multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7278–7287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1879-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend MK, Okereke OI, Xia W, Yang T, Selkoe DJ, Grodstein F. Relation Between Insulin, Insulin-related Factors, and Plasma Amyloid Beta Peptide Levels at Midlife in a Population-based Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31821764ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U, Rostami E. Microdialysis in neurointensive care. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2145–2152. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittig I, Schagger H. Advantages and limitations of clear-native PAGE. Proteomics. 2005;5:4338–4346. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan P, Bero A, Cirrito J, Xiao Q, Hu X, Wang Y, Gonzales E, Holtzman D, Lee J-M. Characterizing the Appearance and Growth of Amyloid Plaques in APP/PS1 Mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:10706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2637-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]