Abstract

Gram-negative bacteria have evolved an elaborate process for the recycling of their cell wall, which is initiated in the periplasmic space by the action of lytic transglycosylases. The product of this reaction, β-D-N-acetylglucosamine-(1→4)-1,6-anhydro-β-D-N-acetylmuramyl-L-Ala-γ-D-Glu-meso-DAP-D-Ala-D-Ala (compound 1), is internalized to begin the recycling events within the cytoplasm. The first step in the cytoplasmic recycling is catalyzed by the NagZ glycosylase, which cleaves in a hydrolytic reaction the N-acetylglucosamine glycosidic bond of metabolite 1. The reactions catalyzed by both the lytic glycosylases and NagZ are believed to involve oxocarbenium transition species. We describe herein the synthesis and evaluation of four iminosaccharides as possible mimetics of the oxocarbenium species, and disclose one as a potent (compound 3, Ki = 300 ± 15 nM) competitive inhibitor of NagZ.

Keywords: Iminosaccharide, NagZ, MltB, Peptidoglycan, β-Lactam

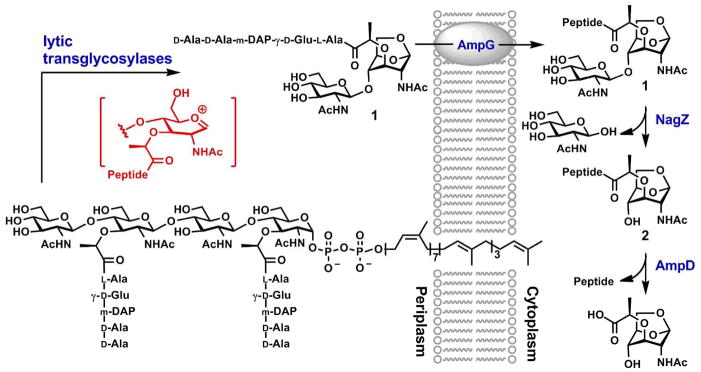

Bacterial cell wall is recycled in the normal course of growth of many Gram-negative bacteria. The recycled peptidoglycan components are processed during the growth and maturation of the cell wall, and in response to damage by antibiotics.1 Peptidoglycan recycling in the periplasm commences with the catalytic action of the lytic transglycosylases (Fig. 1). These enzymes catalyze the non-hydrolytic fragmentation of the glycosidic bond between the N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) and N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) residues of the peptidoglycan-derived muropeptides. This unusual fragmentation gives the NAG-1,6-anhydromuramyl derivative 1 as a product. Following internalization through the AmpG permease, compound 1 is transformed via a series of enzymatic reactions to key intermediates, enabling merger of the recycling process with the biosynthetic events that lead to the formation of Lipid II. An early cytoplasmic event of muropeptide recycling is the hydrolytic action of the NagZ glycosylase, which removes NAG from 1 to produce compound 2. Subsequent reaction of the protease AmpD removes the peptide segment from compounds 1 or 2.2,3 Once formed, Lipid II is transported to the surface of the plasma membrane, where it is the building unit for the de novo synthesis of the peptidoglycan.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the early events of cell-wall recycling.

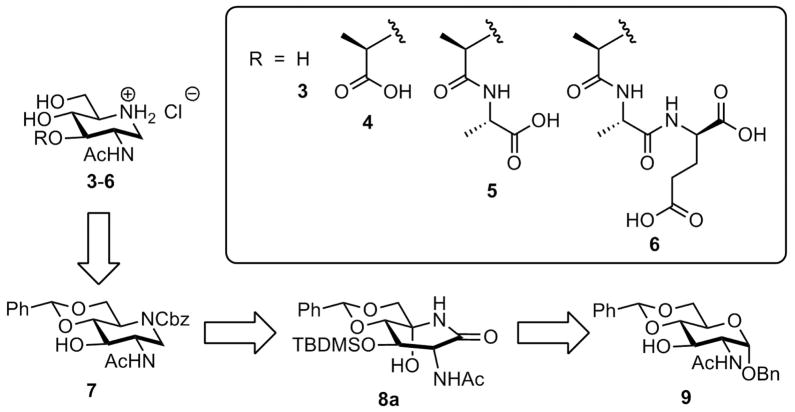

The distinct reactions of lytic transglycosylase(s) and NagZ—one is a non-hydrolytic transglycosylase and the other a hydrolytic glycosidase—are nonetheless proposed to go through conformationally distinct oxocarbenium species in the key step of their respective reactions. The oxocarbenium species in the former entraps the C6 hydroxyl group as a nucleophile, whereas a different oxocarbenium species in the latter is captured by a water molecule. The subjects of iminosaccharide properties, conformations and bioactivities have been reviewed.4,5 Here we evaluate the piperidine iminosaccharides 3–6, inspired by the structures of the NAG (3) and the NAM (4–6) moieties found in the bacterial peptidoglycan, as possible mimics of oxocarbenium species generated in the course of the reactions by these two enzymes.

We report herein their syntheses and their inhibitory properties against purified recombinant NagZ of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the lytic transglycosylase MltB of Escherichia coli. As indicated above, compound 3 potentially mimics the oxocarbenium species encountered in the turnover of 1 by NagZ and compounds 3–6 are potential mimics for the species in reaction of lytic tranglycosylases.

The synthetic plan to iminosaccharide derivatives 3–6 was envisioned to proceed via a protected 2-acetamido-1,2-dideoxynojirimycin (7) as the common intermediate. Several syntheses of piperidine iminosaccharides have been reported.6–20 Our approach to intermediate 7, as depicted in the retrosynthetic route of Fig. 2, is based on the synthesis of lactam 8a, followed by its reduction to the piperidine. While this route is conceptually based on the prior syntheses of GlcNAc iminosaccharide mimetics,17–20 it incorporates a protecting group strategy that is advantageous to structure-activity development toward incorporation of the lactate moiety at C3. This orthogonal protective strategy also allows facile incorporation of a second saccharide at C4.

Figure 2.

Iminosaccharides (3–6) based on the structural templates of NAG and NAM and their retrosynthetic analysis.

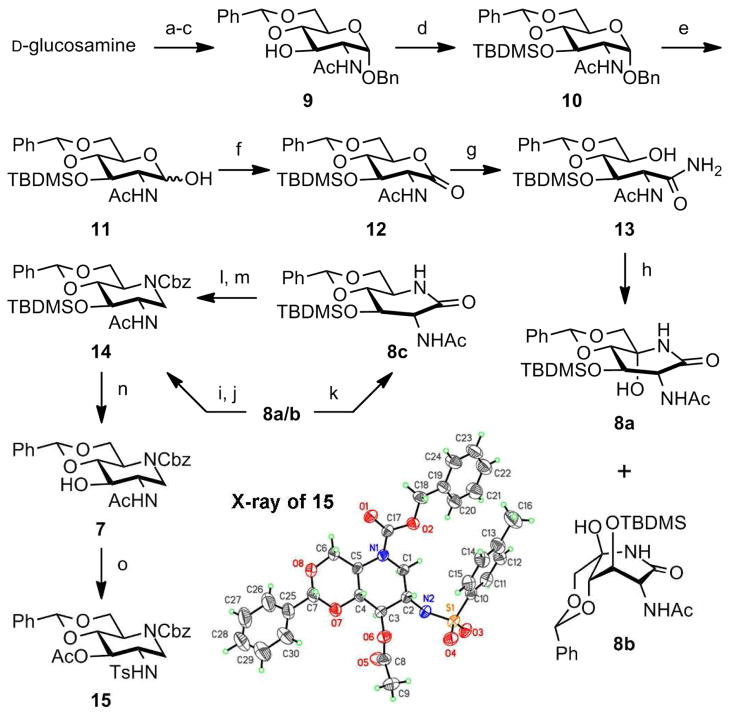

Starting material 9 was prepared from D-glucosamine in three steps with an overall yield of 77% by small variation of known procedures21,22 (Scheme 1). Briefly, D-glucosamine was selectively N-acetylated and α-OBn group was introduced at C1 with thermodynamic control. Finally 4,6-O-benzylidene was introduced in the presence of p-TsOH to give compound 9. Transformation of 9 to 11 was straightforward, with introduction of the silyl protective group at C3 and removal of the benzyl protective group at C1. This orthogonal protective scheme is critical for selective functional group manipulation toward the target molecules 3–6.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the key intermediate 7a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) NaOMe, MeOH, 40 °C; Ac2O, 40 °C; (b) BnOH, AcCl, 50 °C; (c) PhCH(OMe)2, TsOH, DMF, 70 °C, 88% (3 steps); (d) TBDMSCl, imidazole, DMF, 70 °C, quant.; (e) H2, Pd/C, THF, rt, quant.; (f) PCC, CH2Cl2, rt, and (g) NH3/MeOH, CH2Cl2, rt, 77% (2 steps); (h) TPAP, NMO, CH2Cl2, rt, 61%; (i) BH3·SMe2/THF, CH2Cl2, rt; (j) CbzCl, Pyr, CH2Cl2, rt, 29% (2 steps); (k) NaBH3CN, TFA, rt, 35%; (l) BH3·SMe2/THF, CH2Cl2, rt; (m) CbzCl, Pyr, CH2Cl2, rt, 64% (2 steps); (n) TBAF, THF, rt, quant.; (o) TsCl, Py, reflux, 76%.

The PCC oxidation of 11 provided lactone 12, which was converted to 13 by ammonolysis. We observed transient formation of methyl ester of C1 during the reaction, however it was slowly converted to carboxamide 13, which was oxidized with a catalytic amount of tetrapropylammonium perruthenate (TPAP) in the presence of N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMO) to the diastereomeric mixture of hydroxyl lactams 8a (D-gluco) and 8b (L-ido) in 2:3 ratio. Stereoselective twofold reduction of the lactam mixture (8a/b) using borane diemthylsulfide, followed by amine protection with CbzCl, gave the protected 2-acetamido-1,2-dideoxynojirimycin 14 in 29% yield from the mixture of 8a/b. In an attempt at improving the low yield, we pursued a stepwise approach17–20 for stereoselective dehydroxylation of the mixture 8a/b using NaBH3CN/trifuloroacetic acid (35%), followed by reduction of lactam (8c) with BH3·SMe2 (64%). We observed no transformation of 8b during the first reaction, which is the main reason for the low yield. Overall, the two steps approach was not advantageous over the one-pot treatment with borane. In preparation of similar molecules, Vasellat et al. used Jones oxidation or Dess-Martin periodinane, followed by acid treatment (acetic acid or BF3·OEt2) to improve proportion of tri-O-benzyl protected derivative of 8a over 8b.18 This strategy was not applicable to our chemistry, as some of the protective groups for the required orthogonal protection would not survive the treatment. Despite the low yield, we were able to isolate compound 14 in pure form in quantity, and we carried it over to the next stage of the synthesis.

The TBDMS group of 14 was removed in quantitative yield to give key intermediate 7. The structure of 7 was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis of its crystalline tosyl derivative 15. We have discussed separately the mechanism of the type of N,O-acetyl migration shown in the formation of 15.23 This solid-state structure of 15 is the first of 2-acetamido-1,2-dideoxynojirimycin derivatives (the solid-state structure of the O-deprotected 1,5-piperidinone lactam is known18). The structure of 15 confirms both the regiochemistry and stereochemistry of all the transformations shown in Scheme 1.

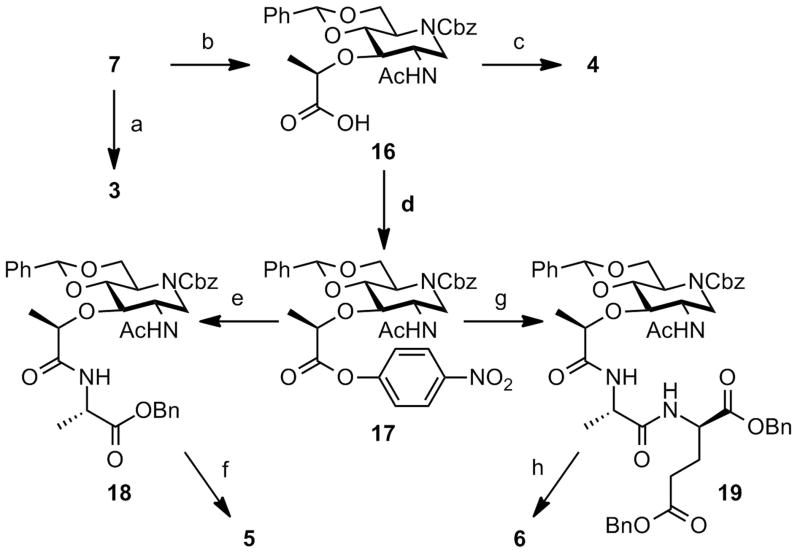

Introduction of the lactate moiety into 7 gave 16, which was then converted to the activated ester 17 (Scheme 2). Amides 18 and 19 were conveniently formed by aminolysis. Deprotection of 7, 16, 18 and 19 by catalytic hydrogenolysis gave iminosaccharides 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively. The 1H NMR data for 3 coincided with literature values.7 Structures related to 4–6 were prepared previously for evaluation as immunoadjuvants.9,10

Scheme 2. Synthesis of iminosaccharides 3–6a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) H2, Pd/C, HCl, iPrOH, rt, quant.; (b) (S)-2-chloropropionic acid, NaH, THF, 60 °C, 91%; (c) H2, Pd/C, HCl, iPrOH, rt, quant.; (d) p-nitrophenyl trifluoroacetate, Py, TEA, CH2Cl2, rt, 72%; (e) L-alanine benzyl ester, TEA, THF, CH2Cl2, reflux, 85%; (f) H2, Pd/C, HCl, iPrOH, rt, quant.; (g) dibenzyl N-(L-alaninyl)-D-glutamate, TEA, THF, CH2Cl2, reflux, 90%; (h) H2, Pd/C, HCl, iPrOH, rt, quant.

The four compounds were evaluated for binding to the E. coli MltB lytic transglycosylase. We reported previously the purification of a His-tag version of this protein that introduced several amino acids to its C-terminus.24 Here, we used a new His6x-tagged construct having only two additional C-terminal amino acids, and also purified to homogeneity (Supporting Information). Compound 3 is missing the lactate moiety that is found in NAM (no substituent at C3). Compounds 4, 5, and 6 each show progressively larger portions of the peptide stem appended to the lactate. The reaction of lytic tranglycosylase MltB from E. coli (used in the present work) was characterized earlier,24–26 including a quantitative analysis of the turnover chemistry of MltB using a synthetic peptidoglycan sample.24

The ability of the MltB lytic transglycosylase to bind the iminosaccharides was assessed using the intrinsic fluorescence of the tryptophan and/or tyrosine residues (of which there are eight and sixteen in the protein, respectively) of this enzyme. Based on the MltB X-ray structure, Trp165 is on a loop close to the active site and Trp247, though more distal, makes interactions with the loop (amino acids Ser216–Met227) that comprises a portion of the binding site. In addition, several tyrosine residues (Tyr117, Tyr191, Tyr259, Tyr338, Tyr344) line the active-site groove. Upon excitation at 280 nm, the emission spectrum showed a maximum at 334 nm, consistent with the existence of a Tyr-to-Trp energy transfer. Compounds 3 and 4 showed saturable binding to a single site (Kd = 174 ± 9 μM and 1000 ± 200 μM, respectively), accompanied by a non-sataturable and presumably non-specific binding mode (kns = 0.128 ± 0.004 μM−1 and 0.060 ± 0.006 μM−1, respectively). This non-specific binding may occur along the extended active site of MltB. The interactions of compounds 5 and 6 with MltB were simpler: their data fit to a hyperbolic one-site saturation equation (Kd = 189 ± 8 μM and 1010 ± 20 μM, respectively). In retrospect, the unexceptional Kd values for these piperidine iminosaccharides could be rationalized based on a key mechanistic insight by Dijkstra et al.27 These authors argued that subsequent to the formation of the oxocarbenium species, the glucosamine ring should adopt a boat conformation to predispose spatially the C6-hydroxyl group for entrapment by the oxocarbenium ion in the intramolecular ring formation. The formation of the higher-energy boat conformation for the reaction intermediate is facilitated by the enzyme, which might not take place with our synthetic inhibitors, hence their relatively poor ability in inhibiting this enzyme.

The reaction of NagZ of E. coli has been investigated by analogues of compound 1, isolated from the bacterial culture, and which showed complex kinetic behavior with NagZ.28 As the complex kinetics did not allow steady-state measurements at saturation, the authors estimated a Km for substrates in the range of 30–35 μM for this enzyme.28 Using a homogeneous synthetic sample of 1,2,3 we characterized 1 as a substrate for NagZ of P. aeruginosa. Compound 2 was confirmed as the product of this NagZ reaction both by mass spectrometry and by comparison with an authentic synthetic sample (Supporting Information). NagZ hydrolysis of 1 showed saturation and the following kinetic parameters for its turnover were evaluated: kcat = 6.6 ± 0.2 s−1, Km = 104 ± 2 μM and kcat/Km = 6.3 ± 0.2 × 104 M−1s−1).

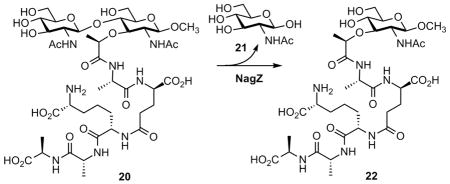

Cheng et al. reported that isolated radioactive cell wall is degraded in the presence of NagZ of E. coli. Hence, NagZ might have other cell wall processing activities.29 In our hands, NagZ of P. aeruginosa recognized a cognate synthetic compound, the NAG-NAM-pentapeptide 20 (see Supporting Information), as a substrate (kcat = 0.77 ± 0.04 s−1, Km = 165 ± 36 μM and kcat/Km = (0.5 ± 0.1) × 104 M−1s−1). NagZ ordinarily would not encounter 20, as only 1 is internalized in the course of recycling of the peptidoglycan. However, this experiment reveals that NagZ might not have evolved for specific turnover of compound 1, with its unusual bicyclic 1,6-anhydromuramyl moiety as the focus of evolution of function.

We used a chromogenic substrate for NagZ, p-nitrophenyl β-D-N-acetylglucosamine, for evaluation of our iminosaccharides as potential NagZ inhibitors. Kinetic evaluation of compounds 3–6 with NagZ identified 3 as a potent competitive inhibitor (Ki = 300 ± 15 nM). The magnitude of this Ki is comparable to the Ki values reported previously for 3 against several β-N-acetylglucosaminidases.6,20 Compounds 4, 5, and 6 were much less effective competitive inhibitors, (respective Ki values of 51 ± 4 μM, 35 ± 3 μM, and 33 ± 2 μM). The poorer inhibition by 4, 5, and 6 is understandable in terms of their C3 substitution, compared to the unsubstituted NAG moiety of the endogenous substrate for NagZ.

The significance of NagZ-dependent exo-glycosidase catalysis has increased following the discovery of its central role28,29 in peptidoglycan recycling by E. coli.1,30 Peptidoglycan recycling is monitored by many of the Gram-negative bacteria for the purpose of controlling induction of the expression of β-lactamase enzyme, in response to cell wall damage by β-lactam antibiotics.31 Small molecule inhibition of NagZ attenuates β-lactamase expression with concomitant improvement in in vitro β-lactam efficacy, both in E. coli and P. aeruginosa.32–34 Given the successful application of structure-based design toward potent and selective GlcNAc pyranosylidene aminocarbamate inhibitors of NagZ35,36 and the proven synthetic strategies toward improved iminosaccharide inhibitor efficacy,6–16,20,37,38 our observation of potent NagZ inhibition by a piperidine-based GlcNAc iminosaccharide augurs well for future application of the iminosaccharide for small molecule interrogation of these pathways.36,39 Moreover, as it has now been proven that peptidoglycan recycling occurs in at least one Gram-positive bacterium (Bacillus subtilis)40 and engages a mechanistically distinct NagZ ortholog,41 this inhibitor class may have broad-spectrum implication toward efforts to preserve clinical relevance for the β-lactam antibiotics.42

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, and by postdoctoral fellowships by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (to BB) and a Pew Latin American Fellowship in the Biomedical Sciences, supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts (to LIL). The Mass Spectrometry & Proteomics Facility of the University of Notre Dame is supported by grant CHE-0741793 from the National Science Foundation.

We thank T. Wencewicz and M. Miller (University of Notre Dame) for the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain and B. Galán (National Research Council-CIB) for a gift of the pET28a plasmid.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures, characterization data for all new compounds including the 1D (1H, 13C NMR, DEPT) and 2D NMR spectra (H–H COSY and C–H HETCOR), and the crystallographic information file (CIF) of compound 15. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Park JT, Uehara T. How bacteria consume their own exoskeletons (turnover and recycling of cell wall peptidoglycan) Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:211–227. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00027-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee M, Zhang W, Hesek D, Noll BC, Boggess B, Mobashery S. Bacterial AmpD at the crossroads of peptidoglycan recycling and manifestation of antibiotic resistance. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8742–8743. doi: 10.1021/ja9025566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesek D, Lee M, Zhang W, Noll BC, Mobashery S. Total synthesis of N-acetylglucosamine-1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramylpentapeptide and evaluation of its turnover by AmpD from Escherichia coli. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5187–5193. doi: 10.1021/ja808498m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compain P, Martin OR, editors. Iminosugars: From synthesis to therapeutic applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kajimoto T, Liu KKC, Pederson RL, Zhong Z, Ichikawa Y, Porco JA, Jr, Wong CH. Enzyme-catalyzed aldol condensation for asymmetric synthesis of azasugars: synthesis, evaluation, and modeling of glycosidase inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6187–6196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleet GWJ, Smith PW, Nash J, Fellows LE, Parekh RB, Rademacher TW. Synthesis of 2-acetamido-1,5-imino-1,2,5-trideoxy-D-mannitol and of 2-acetamido-1,5-imino-1,2,5-trideoxy-D-glucitol, a potent and specific inhibitor of a number of β-N-acetylglucosaminidases. Chem Lett. 1986:1051–1054. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böshagen H, Heiker FR, Schüller AM. The chemistry of the 1-deoxynojirimycin system. Synthesis of 2-acetamido-1,2-dideoxynojirimycin from 1-deoxynojirimycin. Carbohyrdr Res. 1987;164:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(87)80126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kappes E, Legler G. Synthesis and inhibitory properties of 2-acetamido-2-deoxynojirimycin (2-acetamido-5-amino-2.5-dideoxy-D-glucopyranose, 1) and 2-acetamido-1.2-dideoxynojirimycin (2-acetamido-1,5-imino1,2,5-trideoxy-D-glucitol,2) J Carbohydr Chem. 1989;8:371–388. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishida H, Kitagawa M, Kiso M, Hasegawa A, Azuma I. Synthesis and immunoadjuvant activity of N-[2-O-(2-acetamido-1,2,3,5-tetradeoxy-1,5-imino-D-glucitol-3-yl)-D-lactoyl]-L-alanyl-D-isoglutamine. Carbohydr Res. 1990;208:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)80109-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiso M, Kitagawa M, Ishida H, Hasegawa A. Studies on glycan processing inhibitors – synthesis of N-acethylhexosamine of N-acetylhexosamine analogs and cyclic carbamate derivatives of 1-deoxynojirimycin. J Carbohydr Chem. 1991;10:25–45. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furneaux RH, Gainsford GJ, Lynch GP, Yorke SC. 2-Acetamido-1, 2-dideoxynojirimycin: an improved synthesis. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:9605–9612. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gradnig G, Legler G, Stütz AE. A novel approach to the 1-deoxynojirimycin system: synthesis from sucrose of 2-acetamido-1, 2-dideoxynojirimycin, as well as some 2-N-modified derivatives. Carbohydr Res. 1996;287:49–57. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patil NT, John S, Sabharwal SG, Dhavale DD. 1-Aza-sugars from D-glucose. Preparation of 1-deoxy-5-dehydroxymethyl-nojirimycin, its analogues and evaluation of glycosidase inhibitory activity. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:2155–2160. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swaleh S, Liebscher J. New strategy for the synthesis of iminoglycitols from amino acids. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3184–3193. doi: 10.1021/jo010665z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Rawi S, Hinderlich S, Reutter W, Giannis A. New strategy for the synthesis of iminoglycitols from amino acids. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:4366–4370. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiner AJ, Schitter G, Stütz AE, Wrodnigg TM, Tarling CA, Withers SG, Mahuran DJ, Tropak MB. 2-Acetamino-1,2-dideoxynojirimycin—lysine hybrids as hexosaminidase inhibitors. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2009;20:832–835. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Overkleeft HS, van Wiltenburg J, Pandit UK. An expedient stereoselective synthesis of gluconolactam. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2527–2528. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granier T, Vasella A. Synthesis and some transformations of 2-Acetamido-5-amino-3,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-2,5-dideoxy-D-glucono-1,5-lactam. Helv Chim Acta. 1998;81:865–880. [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Berg RJBHN, Noort D, Milder-Enacache ES, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, Benschop HP. Approach toward a generic treatment of gram-negative infections: synthesis of haptens for catalytic antibody mediated cleavage of the interglycosidic bond in lipid A. Eur J Org Chem. 1999:2593–2600. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho CW, Popat SD, Liu TW, Tsai KC, Ho MJ, Chen WH, Yang AS, Lin CH. Development of GlcNAc-inspired iminocyclitiols as potent and selective N-acetyl-beta-hexosaminidase inhibitors. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:489–497. doi: 10.1021/cb100011u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger I, Nazarov AA, Hartinger CG, Groessl M, Valiahdi SM, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK. A glucose derivative as natural alternative to the cyclohexane-1, 2-diamine ligand in the anticancer drug oxaliplatin? ChemMedChem. 2007;2:505–514. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BABIč A, Pečar S. Total synthesis of uridine diphosphate-N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:2265–2271. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi T, Hesek D, Lee M, Oliver AG, Mobashery S. Sulfonylation-induced N- to O-acetyl migration in 2-acetamidoethanol derivatives. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3515–3517. doi: 10.1021/jo100456z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suvorov M, Lee M, Hesek D, Boggess B, Mobashery S. Lytic transglycosylase MltB of Escherichia coli and its role in recycling of peptidoglycan strands of bacterial cell wall. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11878–11879. doi: 10.1021/ja805482b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:259–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheurwater E, Reid CW, Clarke AJ. Lytic transglycosylases: bacterial space-making autolysins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thunnissen AMWH, Rozeboom HJ, Kalk KH, Dijkstra BW. Structure of the 70-kDa soluble lytic transglycosylase complexed with bulgecin A. Implications for the enzymatic mechanism. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12729–12737. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vötsch W, Templin MF. Characterization of a β-N-acetylglucosaminidase of Escherichia coli and elucidation of its role in muropeptide recycling and β-lactamase induction. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39032–39038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng Q, Li H, Merdek K, Park JT. Molecular characterization of the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase of Escherichia coli and its role in cell wall recycling. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4836–4840. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4836-4840.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plumbridge J. An alternative route for recycling of N-acetylglucosamine from peptidoglycan involves the N-acetylglucosamine phosphotransferase system in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5641–5647. doi: 10.1128/JB.00448-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uehara T, Park JT. Role of the murein precursor UDP-N-acetylmuramyl-L-Ala-gamma-D-Glu-meso-diaminopimelic acid-D-Ala-D-Ala in repression of β-lactamase induction in cell division mutants. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4233–4239. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4233-4239.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stubbs KA, Balcewich M, Mark BL, Vocadlo DJ. Small molecule inhibitors of a glycoside hydrolase attenuate inducible AmpC-mediated β-lactam resistance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21382–21391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asgarali A, Stubbs KA, Oliver A, Vocadlo DJ, Mark BL. Inactivation of the glycoside hydrolase NagZ attenuates antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2274–2282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01617-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zamorano L, Reeve TM, Deng L, Juan C, Moya B, Cabot G, Vocadlo DJ, Mark BL, Oliver A. NagZ inactivation prevents and reverts β-lactam resistance, driven by AmpD and PBP 4 mutations, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3557–3563. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00385-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balcewich MD, Stubbs KA, He Y, James TW, Davies GJ, Vocadlo DJ, Mark BL. Insight into a strategy for attenuating AmpC-mediated β-lactam resistance: structural basis for selective inhibition of the glycoside hydrolase NagZ. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1541–1551. doi: 10.1002/pro.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stubbs KA, Scaffidi A, Debowski AW, Mark BL, Stick RV, Vocadlo DJ. Synthesis and use of mechanism-based protein-profiling probes for retaining β-D-glucosaminidases facilitate identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa NagZ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:327–335. doi: 10.1021/ja0763605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choubdar N, Bhat RG, Stubbs KA, Yuzwa S, Pinto BM. Synthesis of 2-amido, 2-amino, and 2-azido derivatives of the nitrogen analogue of the naturally occurring glycosidase inhibitor salacinol and their inhibitory activities against O-GlcNAcase and NagZ enzymes. Carbohydr Res. 2008;343:1766–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis BG. A silver-lined anniversary of Fleet iminosugars: 1984–2009; from DIM to DRAM to LABNAc. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2009;20:652–671. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orth R, Pitscheider M, Sieber SA. Chemical probes for the labeling of the bacterial glucosaminidase NagZ via the Huisgen cycloaddition. Synthesis. 2010:2201–2206. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Litzinger S, Duckworth A, Nitzsche K, Risinger C, Wittmann V, Mayer C. Muropeptide rescue in Bacillus subtilis involves sequential hydrolysis by β-N-acetylglucosaminidase and N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidase. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:3132–3143. doi: 10.1128/JB.01256-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Litzinger S, Fischer S, Polzer P, Diederichs K, Welte W, Mayer C. Structural and kinetic analysis of Bacillus subtilis N-acetylglucosaminidase reveals a unique Asp-His dyad mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35675–35684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llarrull LI, Testero SA, Fisher JF, Mobashery S. The future of the β-lactams. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.