Abstract

The metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) has become the global standard of measuring burden of disease. DALYs are comprised of years of life lost due to premature mortality and years of healthy life lost due to living with disability. In order to calculate the second part of the DALY equation, disease specific disability weights have to be established, i.e., measures for the decline of health associated with these disease states, which vary between 0 for perfect health and 1 for death. Although these disability weights are key for estimating DALYs, there have not been many comprehensive studies with empirical determinations of them. This article describes a systematic review on the state of the art with respect to empirically determining disability weights. Based on this review, a multi-method approach is outlined, which has also been implemented in a U.S. study to measure burden of disease. This approach involves the use of psychometric methodology as well as economic trade-off methods for determining the value of health states. It is conceptualized as a disaggregated approach, where the disability weight of any health state can be calculated if the attributes of this health state are known. The U.S. study received the collaboration of experts from more than 20 institutes of the National Institutes of Health and of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. First results will be available by the end of this year.

Keywords: disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), burden of disease, disability weight, empirical assessment, psychometrics, trade-off methods

Background

Disability-adjusted life years as a summary measure of health

Since the first appearance of the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD; World Bank 1993), summary measures of population health (Murray et al., 2000) have been indispensible in presenting and comparing the health status of populations, as well as informing the priority setting with respect to health care planning (van der Maas 2003; for a historical overview see Etches et al., 2006). Such summary measures combine information about mortality and non-fatal health consequences into one single value able to represent the health of a particular population (Field and Gold 1998). In order to fulfill their main purpose, summary measures should emphasize premature mortality instead of reflecting a simple “body count” of deaths, be based on strict epidemiological estimates, display internal consistency, enable rigorous validation of measures and estimates, and integrate health outcomes systematically into an index value (McKenna and Marks 2002; Murray and Lopez 2000). Best suited to these criteria, the concept of disability adjusted life years (DALYs; Murray 1994; 1996) has become the most influential summary measure for global health.

| (formula 1) |

where:

YLL = years of life lost due to premature mortality.

YLD = years lived with disability, defined in formula 2.

| (formula 2) |

where:

YLD = years lived with disability.

I = number of incident cases.

DW = disability weight.

LD = average duration of disability (years)

As described in the above formulas, DALYs combine years of life lost due to premature mortality with years of healthy life lost due to living with disability, where the latter term is determined by the incidence of the underlying health condition, the duration of the time living with disability, and the level of disability of the underlying health state, called the disability weight.

While DALYs have been quite successful in practical applications, there is still an ongoing debate regarding their theoretical framework, ethical foundations, and operationalization (for reviews see Field and Gold 1998; Murray et al., 2002; see also below). Of course, many of the points raised are not limited to DALYs but also concern summary measures of health in general. We will review these areas and their criticisms only as far as they concern the design of a study deriving new disability weights for the US (see point on objectives below).

Disability weights as key element of DALYs

As seen above in formula 2, the values of disability weights (DWs) are key for determining DALYs. A DW is a metric for the decline of health associated with a certain heath state, varying between 0 (perfect health) and 1 (death). In regards to the conceptual framework, it is clear that all DWs assume the existence of distinct constructs of health and disability, which, if the same DWs are applied globally, must be comparable across geographic region(s) and population(s). The construct of health should be distinguishable from both smaller concepts such as specific diseases or mortality risk (Breslow 2006) and broader concepts such as well-being. Based on the construct of health, disability can then be defined as the decline of health in the different health states examined. All operationalizations discussed below or used in the literature to elicit DWs (overviews: Arnesen and Trommald 2005; Doctor et al., 2008; Green et al., 2000; Morimoto and Fukui 2002; Mortimer and Segal 2008; Ryan et al., 2001) rely on such an explicit construct of health. Of course, the content of the construct is partly determined by the questions asked, but most importantly by the definition of health states (Fowler 1995; for a theoretical basis see Grice 1975; Schwarz 1996). For instance, if all health states are described by degrees of different attributes such as cognition, mobility, or social relationships, a respondent will infer that these dimensions should be included in their response about which state is healthier or less disabling (Wänke et al., 1995). This may be relevant if the respondents, outside of the judgment situation, would not have included certain dimensions in their constructs (e.g., the attribute “social relationships” may not be part of health for certain people, but may be included for others). Although there have been discussions on whether such a construct of health can be meaningfully assessed or if it even exists (Broome 2004), empirical evidence has shown that most respondents are capable of answering questions about which of two people is healthier or which condition is more disabling. This indicates that an integration of relevant attributes from different domains into one category of health or decrements thereof is possible. A related question concerns the use of vectors of multiple attributes vs. a single summary statement as descriptors of health (“basket presentation” versus global measure Etches et al., 2006). For the purposes of this paper it suffices to say that for summary measures of population health, by definition, an integrated measure is needed (see review of different objectives for health measures cf. McDowell et al., 2005).

The ethical discussions about DALYs have mainly concerned the potential resource allocations linked to the quantification of burden of disease. These discussions are irrelevant if one does not assume that some properties of burden of disease measures, such as DALYs, have direct implications for resource allocation. Our view certainly does not imply such implications; while the burden of disease should be weighted into such allocation decisions, other considerations for fairness or equity should also be formally integrated (Bleichrodt et al., 2005; Dolan and Olsen 2001; Stolk et al., 2005) into the decision making process.

The above point of view does not imply that resource allocation scenarios cannot be used as one operationalization for eliciting DW (of course keeping in mind the effects of such operationalizations; see Damschroder et al., 2007; Schwappach 2005; for examples). As will laid out below, we suggest a multi-method approach for eliciting DW, including direct comparisons of disability of health states as well as indirect derivation from tradeoff tasks.

Other ethical considerations, more directly linked to the DW operationalization and assessment, were made by Arnesen and Nord (1999) who argued that in the original determination of DW in the GBD 1990 study, the health value of individuals may have been unethically set equal to that of their life. Especially scenarios where the decision maker, in order to determine a DW for health states, had to choose between the lifes of k healthy people and the lifes of k+x disabled people, contain an assumption that health and life were the same dimension. While we concede the potential risk that this argument denotes, especially if health state comparisons from a strict personal perspective are used as elicitation method (Damschroder et al., 2005a), we believe that different operationalizations, such as the ones presented below, may actually invalidate this specific criticism.

On the empirical determination of DWs: objective of this paper

Given the magnitude of theoretical discussion and the importance of the topic, it is surprising that in practical terms only few efforts have been undertaken to empirically and comprehensively study DWs for the basis of estimating DALYs. More work has been done on empirically deriving weights for quality-adjusted life years (QALYs, for an overview see Mortimer and Segal 2008) with similar methodology (Murray et al., 2000; 2002), but again there are no comprehensive efforts of including the full spectrum of morbid conditions.

All of the global World Bank and WHO statistics on burden of disease have been based on disability weights from two valuation exercises from the original 1990 GBD study (Murray and Lopez 1996), appended by the Dutch valuation study (Stouthard et al., 1997). It is an open question whether these disability weights apply to the U.S. in the year 2005, given the empirical result of cultural specificity of key disability weights, as well as the differing cultural and treatment situation (Üstün et al., 1999a). With this background in mind, it was decided to assess U.S. specific disability weights as part of a U.S. burden of disease study.

The objective of this paper, as a part of this study, is to prepare the best possible assessment methods for establishing US-specific DWs. Solely restricted to this objective, we review theoretical and empirical results of past research on DWs and exclude arguments which have no implications for empirically establishing DW, as well as incorporate results from this study. For instance, any argument of whether or not resources should be solely based on DALYs has no direct implications on the design and measurement of DW studies, as we will also use different approaches on eliciting DW (see below). Needless to say, we also exclude any thorough discussion on cultural differences in establishing global weights (Üstün et al., 1999a; 1999b), as we are restricted to one country. Of course, within a country cultural differences may still be relevant, but this is on a smaller scale compared to a situation where a global perspective is used.

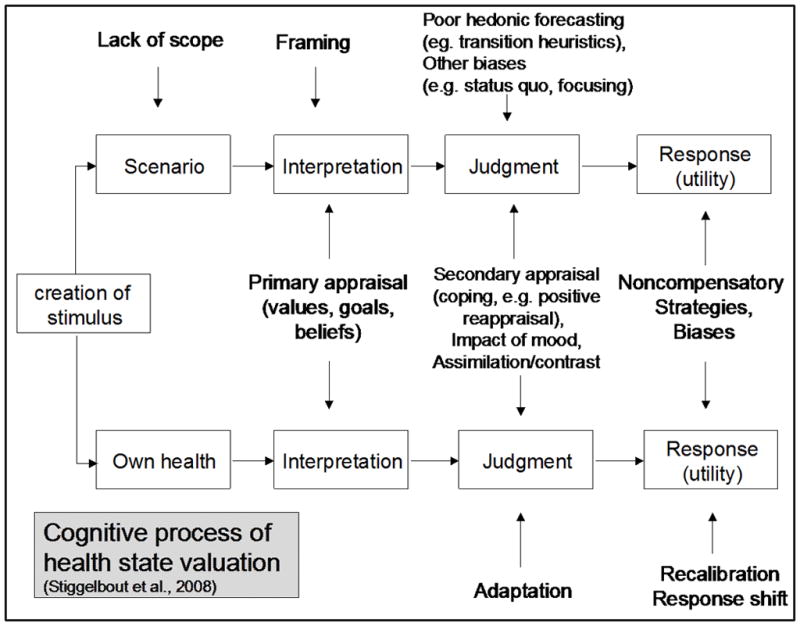

Social psychology is the perspective of our review. Throughout this article, establishing DWs is conceptualized as a judgmental task that is solved at the very moment in which respondents are asked to compare different health states. In other words, people use the information available at the moment in which the judgment task is given and the usual laws of questionnaire construction and interview design apply (Schwarz 1996). In doing this, we assume that there is a quantifiable construct of “health”. Our focus is on the cognitive processes of the respondent in the judgment situation; we are concerned with how the respondent perceives and answers the judgmental tasks rather than how a philosopher or third party would. Figure 1 gives an overview of the cognitive model used here, which is an adaption from Stiggelbout and de Vogel-Voogt (Stiggelbout and de Vogel-Voogt 2008).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model of cognitive process of health state valuation (Stiggelbout and de Vogel-Voogt 2008)

In valuing health states, first the perspective of the judgmental task has to be clarified: the respondent can either judge based on her/his own health or experiences or from a third person perspective. If a third person perspective is adopted, it is important that the respondent be prepared to solve a relatively difficult judgmental task. If the respondent is not prepared and just undergoes the task for other reasons, e.g. to obtain an honorarium, more or less “random” judgments are produced because of lack of scope. The situation will then be evaluated. In a third person perspective, the scenario given by the interviewer is key, as this frames the activation of one’s own relevant experiences, values, and emotions. The exact response format also contributes to the overall framing (Bless et al., 1992; Schwarz and Hippler 1987). At this point the secondary appraisal with the valuation of health states will occur. It will rely on the usual principles of human decision making in complex circumstances (Stiggelbout and de Vogel-Voogt 2008). These include:

Judgmental heuristics such as overweighting of rare or salient events and underweighting of the usual and expected (Gigerenzer et al., 1999; Kahneman et al., 1982);

Use of own mood and emotions as informative indicators for valuation of other health states (Schwarz and Clore 2003);

Assimilation and contrast with standards stored in long-term memory and judged relevant for the current task (Sudman et al., 1996);

Biases arising from the direction of change of health states (Wänke et al., 1995) (equal level of improvement valued as less important compared to a change for the worse)

The judgmental processes are unconscious and are unlikely to be influenced by deliberation. Conversely, the last step of the valuation incorporates the deliberate editing of the judgment. An answer will be given, which not only reflects the subjective valuation of the health states, but is also compatible with other principles the person believes are relevant for themselves and the interview situation. For example, considerations of fairness or political correctness may influence the final judgment in addition to the subjective valuations. The cognitive model used here unlike others (e.g., prospect theory by Kahneman and Tversky 1979) does not explicitly incorporate time perspective into the judgmental process (see Rasiel et al., 2005, for an application), but known empirical consequences of (for instance) respondent’s age or duration of health states are referred there in the “secondary appraisal” step as biases and/or adaptation processes.

The measurement of DWs: methods and critical discussion

Measurement of disability weights: concepts and operationalizations

DWs place differing health states onto a common continuum ranging from 0 to 1; perfect health has a value of zero and death has a value of one. A classical economist may sometimes separate between values of a quantitative evaluation resulting from a decision under certainty, and preferences resulting from a decision under uncertainty (Drummond et al., 1997). Throughout this article we refer to both concepts (i.e., values, preferences) as synonyms, because from a psychological perspective “objective” uncertainty seems negligible when compared to characteristics as perceived by the respondent or decision maker (e.g. subjective probability).

To arrive at the non-fatal component of a global summary measure for population health, the incidence of health states is usually recorded, weighted for the average duration of the respective state and then DWs are applied (see Formula 2 above). The term “health state” is not identical with the concept of “disease”, as several diseases can coincide into the same health state (e.g., deafness resulting from different diseases) or one disease can cause various health states for the person affected during its (natural or treated) course. We will discuss various systems to classify health states later in this article.

There is no gold standard for eliciting DW for health states. Methods used stem from two distinct traditions: psychometrics (Revicki and Kaplan 1993) and economic evaluation (Dolan 2000). Among the most popular techniques for constructing quantitative DW from a psychometric tradition are

Rating scales and questionnaire-based instruments which have been shown to be transformable into a DW (McDowell 2006; for example of an instrument see the Health Utilities Index below): the respondent uses Likert scale response formats to describe ability to perform various health related activities or emotional states;

Ranking exercises (Klein et al., 2004; see also Salomon 2003, how ranks could be transformed into DWs): respondents order a number of vignettes describing health states according to their perceived level of disability;

Magnitude estimation (ME; Beltyukova et al., 2008): respondents produce a direct number denoting how many times a certain health state is more disabling compared to another health state;

Visual analogue scaling (VAS; Parkin and Devlin 2006; van Osch and Stiggelbout 2005): respondents give estimations of the level of disability by marking on a printed line, where 0 denotes full health and 1 death;

Pairwise comparison (PC), which can be transformed into a DW based on Thurstone’s law of comparative judgment (Thurstone 1927); pairwise comparisons have also been used as basis for the economic “stated preference” approach (Lancaster 1971; Lancsar et al., 2007).

Economic theory based DW often use the following trade-off techniques:

Standard gamble (SG; Gafni 1994; Morimoto and Fukui 2002; van Osch and Stiggelbout 2008): respondents choose between a certain, but suboptimal health state A and a lottery between perfect health and death. The probabilities of health and death are varied and the point of indifference (a choice between health and death seems impossible at this point) is used to estimate the difference in utility between health state A and perfect health;

Time trade-off (TTO; Buckingham and Devlin 2006) (see below) and

Person trade-off techniques (PTO; Green 2001; Pinto Prades 1997) (see below) Slightly different in logic, is the willingness to pay approach (WTP, Olsen and Smith 2001), where respondents are asked to state how many resources they are willing to pay for achieving a certain health state.

Estimation of disability weights in the GBD 1990 study (version: Murray and Lopez 1996)

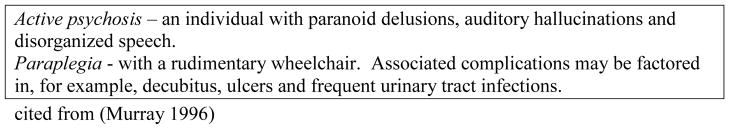

Murray and Lopez’ (1996) descriptions of a health state via labels is a diagnostic term (e.g. “active psychosis”) followed by some key symptoms that can either illustrate the state or give information on the severity of illness. As can be seen from the example describing “paraplegia” in Figure 2, the potential sequelae or co-morbidities are sometimes also included in the description (e.g. secondary infections). As the assessment of DWs should only concentrate on the decline of health during the time lived with the disability, and not on course, prediction of outcome or co-morbidity, such descriptions should be avoided when eliciting the DW for “paraplegia” on its own. Of course, other aspects are also important but within the burden of disease framework they deal only with the epidemiological calculations.

Figure 2.

Description of a health state via disease characteristics.

In the 1990 GBD, two trade-off methods, PTO and TTO, were used for eliciting DWs for health states. In the PTO method, respondents (mostly clinical experts) were presented with a scenario in which 1,000 healthy individuals could be prevented from death for exactly one year through the purchase of a certain unspecified intervention ‘A’. They then traded the number of individuals being in a certain (suboptimal) health state against this anchor; this meant that the decision maker could purchase exactly the same life prolongation via an alternative intervention B at exactly the same costs, but covering more people. Thus, the number of additional patients that could outweigh the 1,000 healthy life years gained under alternative A was interpreted as the metric of the distance between the optimal health and the disease state under research. In a second variant of PTO, not only could the lives of the patients in alternative B be saved for one year, but their health condition could also be completely cured.

The second trade-off method, TTO, used a personal perspective and asked the decision makers how many years of a life expectancy, defined as 20 years, they would give up in order to be cured from the respective suboptimal health state. A second variant of the TTO used the age-adjusted conditional life expectancy of the decision makers as the basis for trading one’s life against a complete cure from the respective health state. The PTO and TTO procedures used to elicit DWs by Murray (Murray 1996) have been the subject of considerable criticism. A summary of this criticism and the underlying empirical foundations can be found in Table 1, column 2.

Table 1.

Major criticism on the choice scenarios in the original GBD Study (Murray 1996)

| Critique on PTO-scenarios of the 1990 GBD Study | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scenario | Critique | Precautionary measure |

| “If you purchase intervention A, you will extend the life of 1000 healthy individuals for exactly one year, at which point they will all die. If you do not purchase intervention A, they will all die today. | Artificial “certainty” about life expectancy (Hammerl 2000; Hertwig 1998) but see also QALY-HYE controversy on integrating uncertainty | Formulate realistic time frame for any public health effect mentioned in scenarios |

| Logical contradiction: individuals are “healthy”, but will die today | Avoid pseudo-exact timing for mentioned health effects | |

| PTO1: “At the same cost: If you purchase intervention B, n=2000 blind individuals’ lives are extended for exactly one year. If you prefer intervention B, the number of individuals is reduced.” | No variation in efficacy of treatment (duration of life after cure) between patients; no explicit mentioning of death in alternative B (rule of rescue - (McKie and Richardson 2003 - favours A) | Allow for inter-individual variation of health effects and refer only to sums of the effects. Balance the salience of potential fatal outcomes between scenarios. |

| PTO2: “If you purchase intervention B, you can cure the disability, and n individuals will live exactly one year. Without the intervention they all will die today.” | No variation in efficacy of treatment (duration of life after cure) between patients. | Allow for inter-individual variation of health effects and refer only to sums of the effects. |

| A life-saving measure is compared to a life-saving measure that also cures the health state. => Two judgmental dimensions involved which also could display interaction effects. | Strictly construct effects involving only one dimension of potential gains (e.g. only years of life, or only health status after cure). | |

| Critique to TTO-scenarios of the 1990 GBD Study | ||

|

TTO1:

Suppose you could expect to live20 years in chronic pain. How many of those years would you give up to live the remaining years without pain?” TTO2: “What is the smallest number of years in perfect health that you would accept in exchange for 20 years with severe abdominal pain?” |

Artificial “certainty” about life expectancy (see van Nooten and Brouwer 2004, for the impact of subjective expectations on TTO responses) | Change time frame from life expectancy with censored endpoint to proportions of fixed periods (e.g. hours per day, see Buckingham et al., 1996, for an example) |

| Anchoring effect of respondent’s age (Burström et al., 2006; Chapman and Johnson 1999; Richards and Wierzbicki 1990; Sherbourne et al., 1999) | Change personal into societal perspective | |

| Personal experience with scenario not controlled (Goldberg 2006; Rehm and Strack 1994) | Restrict to scenarios which do not require prior expertise for decision | |

| Adaptation to disease not anticipated (see Damschroder et al., 2005b) | Avoid personal perspective | |

| Unrealistic expectation of a continuous healthy state after cure until death: omission of competing risks. (see Spencer 2003), for incorporation of sequence effects into elicitation method) | Avoid formulations claiming ever- lasting effects (except death) | |

Description of health states

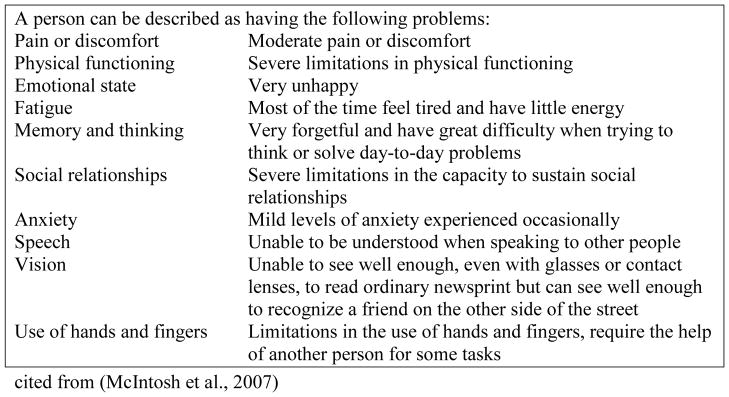

DWs are based on valuations of health states. In practical terms, this means that in the derivation of DW, the respondent must have the health states presented with short descriptions, often no longer than a paragraph (see the health state descriptions of the 1990 GBD above). There are different ways to present such health states. The most common descriptions consist of either a list of symptoms characterizing a disease, a description of functional or activity limitations associated with disease states, or a combination of both. One basic distinction concerns the question of whether health states should be presented with a genuine description specific for each health state (for an example see Figure 2 from Murray 1996), above, or with a listing of levels of a limited number of attributes which are the same for all health states (however, if there is no functional or activity limitation, the attributes will sometimes not be mentioned). An example of the latter, based on functional or activity limitations, is displayed in Figure 3 (based on the Canadian Classification and Measurement System for Functional Health, CLAMES; cf. McIntosh et al., 2007).

Figure 3.

Sample description of health states using unlabeled functional and activity limitations

These health states can be presented either with or without the disease label (diagnosis, see examples Figures 2 & 3). Cognitively, this makes a difference as disease labels carry information not only with respect to health attributes, in part over and above the listed attributes (Sackett and Torrance 1978), but also with respect to stigma and other forms of social evaluations (Frick et al., 1988). Clearly, such a presentation of the disease labels also has an impact on which population group can and should be asked to value the health state, as the knowledge basis about certain diseases differs. Conversely, knowledge about functional limitations such as mobility limitations is universal and we expect fairly similar knowledge bases in professional and non-professional settings. In order to measure and potentially exclude effects of stigma and preconceived schemata regarding diseases, two versions of health state descriptions can be used in parallel: one with disease labels and one without.

Choice of decision maker

The classical approach for deriving DWs was based on medical expertise (Murray and Lopez 1996), i.e. a series of expert meetings in various countries, where the health state descriptions are short and disease oriented (see Figure 2 above). More recent work such as the Dutch Disability Weights Project (Stouthard et al., 1997) has supplemented disease-based descriptions with descriptions based on an EQ 5D-classification, in other words based on functional and activity limitations. In principle, health state descriptions based on these limitations can be used in a general population framework (McIntosh et al., 2007) as well as with medical experts or patients. Different considerations can also be brought forward in favour of one or another group of decision makers; health professionals certainly possess the most knowledge about the health states to be compared including knowledge about functional limitations. Patients or their family members also have accumulated knowledge about their conditions, but they may not have the best knowledge about other conditions (McNamee 2007). Another argument for this states that as the DWs will later often be used in decision making about resource allocation, the perspective of the general population should be taken into account (Boyd et al., 1990; Ubel et al., 2000; Wiseman et al., 2003). This argument however, is not relevant in a framework where DW should mainly reflect levels of health, independent of later resource allocation decisions.

Choices made for the U.S. NIH DALY study

Methodology

We opted for a mixed methodology including

VAS mainly used in the warm-up exercises

Pairwise comparisons and ranking, as input to stated preference analyses

PTO and TTO as economic approaches.

We omitted the standard gamble approach, as this method requires a high level of numeracy (see Woloshin et al., 2001; Zikmund-Fisher et al., 2007, for impact of numeracy on decision making), and has been shown to be influenced by the effect of gain versus losses more than its alternatives (Blumenschein and Johannesson 1998) whose results must be corrected for loss aversion and probability weighting before being comparable to other methods (van Osch and Stiggelbout 2008).

The planned approach for statistical analyses uses factor and factor mixture analyses in order to elicit the final DWs based on input from both the psychometric and econometric methodologies (Flora and Curran 2004; Muthen 2006). All statistical analyses rely on the notion of a latent variable, i.e., the DW, which impacts the various operationalizations. DW is allowed to vary between 0 and 1 only, i.e., no negative health states worse than death are considered.

Health state descriptions

We opted for the variant of describing the health states via levels of functional and activity limitations. These limitations are based on the standardized descriptions of the CLAMES system, a system developed independently by Statistics Canada for the purpose of comprehensively describing all health states in Canada with a uniform framework (see Figure 3 above; see also McIntosh et al., 2007); http://www.statcan.ca/bsolc/english/bsolc?catno=82-005-X20030016643). The CLAMES contains 11 health status attributes adapted from three leading generic health status instruments: the Health Utilities Index Mark III (HUI3; Feeny et al., 2002; Furlong et al., 2001), the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 (SF-36; Ware and Sherbourne 1992); and the European Quality of Life Five-Dimensions Index Plus (EQ-5D; Brooks and EuroQoL Group 1996; EuroQoL Group 1990; Rabin and de Charro 2001). CLAMES focuses on individuals’ capacities (i.e., what they are able to do) with respect to the various attributes, each of which has four or five levels ranging from normal to severely limited functioning. Each health state is represented by levels of functional and activity limitation for each of 11 attributes; thus, 10,240,000 health states are possible within the system (see Figure 3 and Table 2). For the workshops, we prepared anchor descriptions for each of the levels of attributes in case respondents requested such anchors.

Table 2.

Domains of health and functioning as measured by standard measures (from (Wolfson 2003))

| SF 36 (Ware and Sherbourne 1992) | HUI 3 (Feeny et al., 2002; Feeny 2002) | EuroQol (Brooks and EuroQoL Group 1996; EuroQoL Group 1990) | WHO WHS (WHO 2008) | Stats Can CLAMES (McIntosh et al., 2007) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function** | Ambulation | Mobility | Mobility | Physical Function |

| Role limits—physical | Self-care | Self-care | ||

| Mental Health | Emotion** | Affect | Emotion | |

| Role limits—emotional | Anxiety**/depression | Anxiety* | ||

| Pain | Pain/discomfort** | Pain/discomfort** | Pain | Pain/discomfort |

| Social function** | Usual activities | Usual activities | Social relationships | |

| General health | ||||

| Energy** | Fatigue | |||

| Memory and thinking** | Cognition (Dutch ver.) | Cognition | Memory and thinking | |

| Vision** | Vision* | |||

| Hearing** | Hearing* | |||

| Speech** | Speech* | |||

| Use of hands and fingers** | Use of hands and fingers* |

Secondary domain in new Statistics Canada system.

Main source (at least in general terms) for domain in new Statistics Canada system.

The choice of CLAMES also allows better flexibility with respect to integrating new health states. Once there is a description of any health state within the CLAMES system a DW can be derived, as can a valuation which specifies weights for each attribute level and, where necessary, combinations thereof.

In all tasks where health states were to be compared, great care was taken to underline the fact that all valuations should be based on the same duration for all of the valuated health states. In case a workshop insisted on specifying this duration, one month was given as this duration.

Specific operationalization of the PTO and TTO

Based on the literature, the following choices with respect to operationalization were undertaken (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Considerations for constructing best operationalizations

| Source of judgmental bias | Elicitation method affected | Author(s)/Study | Precautionary measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direction of comparison (which health state is subject, and which is the referent) determines the selection of attributes relevant for the comparison => serious order effects shown in PTO-judgments | Pairwise comparisons, trade-off methods | (Schwarz and Sudman 1995; Ubel et al., 2002; Wänke et al., 1995) | Balancing position of health state (l/r) over subjects by random assignment; providing as much as time for judgment, as subjects feel necessary for their evaluations |

| Perspective of judgment (personal involvement in potential gains) alters magnitude of priorities (irrespective of traded good such as people or time) | Trade-off scenarios (mostly PTO, TTO) | (Dolan et al., 2003; Richardson and Nord 1997) | Strictly confining scenarios to social perspective with ex post timeframe (utilization of treatment, not availability) => formulating TTO-scenarios without personal involvement in effects (see also Tsuchiya 1999) |

| Standard Gamble scores are influenced by numeracy, loss aversion, and probability weighting of respondents | SG scenarios | (van Osch and Stiggelbout 2008; Woloshin et al., 2001; Zikmund-Fisher et al., 2007) | Omitting scenarios with probability as a measuring concept |

| Standard Gamble assigns lower values especially to milder health states than TTO | SG scenarios | (Tsuchiya et al., 2006) | Omitting scenarios with probability as a measuring concept |

| Standard Gamble is much more sensitive to framing effects (gains/losses) relative to TTO elicitation | SG and TTO scenarios | (Blumenschein and Johannesson 1998) | Avoiding SG scenarios |

| Improving Health ( = curing “losses”) is strongly prioritized against avoiding decline ( = collecting preventive “gains”) | Trade-off scenarios comparing cure to prevention: | (Schwappach 2002) | Avoiding trade-off scenarios which mix the two types of public health effects; eliciting health state values both in a “cure” and a “prevention” metric separately |

| Health states requiring life-sustaining treatment, but judged better than death, are associated with inconsistent valuation of their duration (the longer, the worse) | TTO-scenarios involving health states with serious conditions | (Fried et al., 2007; Stalmeier et al., 2007) | Change time to a prospective period (e.g. from now until death) to time already “consumed” (e.g. trading people of differing ages) |

| Individual differences determine favouring of cure over prevention. There are also subjects favouring prevention, but only a minority weighs prevention/cure - gains equally. | Trade-off scenarios comparing cure to prevention: | (Ubel et al., 1998); partly contradicts results of (Schwappach 2002) | Even if evidence is contradictory, scenarios that mix cure and prevention should be avoided. |

| PTO - scenarios do not result in multiplicative transitivity | PTO-Scenarios | (Schwarzinger et al., 2004) | Checking transitivity before using scores, rsp. using only the ordinal information of the first step of the PTO eliciting procedure, if not given |

| Severity of illness (initial state) increases preference for the same amount of amelioration/recovery/improvement as a more lenient state. | Only trade-off scenarios involving cure from life-threatening condition; not affected: pairwise comparisons or rankings | (Nord 2004; 2005; 1993b) | Using pairwise comparisons or rankings for measurement. In trade-off comparisons, balance health state to both more serious and more lenient health states and use multivariate regression techniques to adjust net effect |

| A sub-optimal health state after treatment (final state) is weighted lower than would be expected from a health maximization principle, because equity of access to health care is considered more important. | Only trade-off scenarios involving cure or life-saving | (Abellan-Perpinan and Pinto-Prades 1999; Nord 1993a) | Avoiding trade-off scenarios that could involve considerations of both health gain and equity of access. |

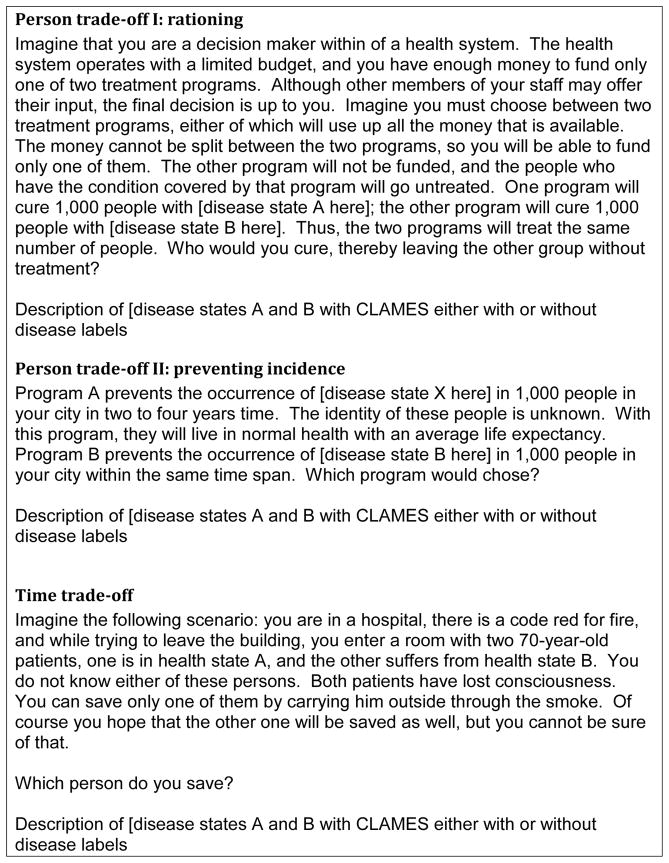

This led to the scenarios described below. Person trade-off scenarios were separately constructed for the prevention and cure of health states. Death as a potential outcome of the scenarios was never mentioned nor set as reference standard in the PTO scenarios, and was avoided as ascertained outcome for the TTO scenario. Though Buckingham and colleagues (Buckingham et al., 1996) proposed some alternatives to the problematic use of a whole lifetime, arguing it as a rather abstract and unfamiliar metric when trading one’s time, we kept duration of life as our measure for TTO elicitation in order to be comparable with the framework of the PTO-scenarios. But we formulated our TTO scenario from a societal perspective (deviating from the usual personal perspective, see also Burström et al., 2006) in order to minimize heterogeneity and inconsistencies in the derived DWs due to personal experiences and beliefs (Bravata et al., 2005). PTO elicitation was performed with the upward titration method, and TTO elicitation was performed with the ping-pong method (Lenert et al., 1998).

Overall and in line with the cognitive perspective on decision making, we tried to implement tasks which would involve the decision maker. There has to be “experimental realism” in the task (Aronson et al., 1990), with impact on the decision maker, which does not necessarily mean that tasks have to simply copy related real tasks (as assumed by Dolan et al., 2003); in fact, experimental realism often implies operationalizations that capture the underlying theoretical concepts without copying everyday situations (Aronson et al., 1990; Rehm and Strack 1994).

Choice of decision makers

We plan to have meetings to derive DWs in all three settings discussed in the literature, i.e. with health professionals, patients, and the general population. It is hypothesized that preference judgments converge between these groups, especially if they are based on a description of functional limitations with the only exception of labelling diseases. However, if our hypothesis does not hold true, we may require a relatively large number of expert meetings to create setting-specific preference weights with relatively small confidence intervals.

Conclusions

DWs are a key ingredient for estimating DALYs or other summary measures of health. To empirically assess such weights, social psychological evidence on judgmental processes, question formulation and formatting has to be taken into consideration. We hope that this review will stimulate more empirical research on assessing DWs in both the U.S and international contexts.

Figure 4.

Examples of Trade-off Scenarios to be used in current NIH DALY Weights Project

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided by NIAAA with contract # HHSN267200700041C to conduct the study “Alcohol- and Drug-Attributable Burden of Disease and Injury in the US” to the first author. We would like to thank T.K. Li and B. Grant for their support of this study, and for organizing meetings to discuss the methodology. F. Kanteres and H. Irving helped with copy editing the manuscript and made valuable contributions on previous versions of the text. Participation and discussions at two meetings and expert hearings within the framework of the Global Burden of Disease 2005 Study helped us to finalize this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jürgen Rehm, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Canada, University of Toronto, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Canada, Technische Universität Dresden, Germany, WHO Collaborating Centre for Substance Abuse, Zurich, Switzerland.

Ulrich Frick, Carinthia University of the Applied Sciences, Dep. Healthcare Management, Feldkirchen, Austria.

References

- Abellan-Perpinan JM, Pinto-Prades JL. Health state after treatment: A reason for discrimination? Health Econ. 1999;8:701–707. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199912)8:8<701::aid-hec473>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen T, Nord E. The value of DALY life: problems with ethics and validity of disability adjusted life years. BMJ. 1999;319:1423–1425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7222.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen T, Trommald M. Are QALYs based on time trade-off comparable? - A systematic review of TTO methodologies. Health Econ. 2005;14:39–53. doi: 10.1002/hec.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E, Ellsworth P, Carlsmith JM, Gonzales M. Methods of research in social psychology. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beltyukova SA, Stone GE, Fox CM. Magnitude estimation and categorical rating scaling in social sciences: a theoretical and psychometric controversy. Journal of Applied Measures. 2008;9:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleichrodt H, Doctor J, Stolk E. A nonparametric elicitation of the equity-efficiency trade-off in cost-utility analysis. J Health Econ. 2005;24:655–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bless H, Bohner G, Hild T, Schwarz N. Asking difficult questions: task complexity increases the impact of response alternatives. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1992;22:309–312. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenschein K, Johannesson M. An experimental test of question framing in health state utility assessment. Health Policy. 1998;45:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(98)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd N, Sutherland H, Karen Z, Heasman D, Cummings B. Whose utilities for decision analysis? Med Decis Making. 1990;10:58–67. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9001000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravata D, Nelson L, Garber A, Goldstein M. Invariance and inconsistency in utility rankings. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:158–167. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05275399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow L. Health measurement in the third era of health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:17–19. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R EuroQoL Group. EuroQoL: The current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome J. Weighing lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham J, Birdsall J, Douglas J. Comparing three versions of the trade-off: time for a change? Med Decis Making. 1996;16:335–347. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham J, Devlin N. A theoretical framework for TTO valuations of health. Health Econ. 2006;15:1149–1154. doi: 10.1002/hec.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F. A comparison of individual and social time trade-off values for health states in the general population. Health Policy. 2006;76:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman G, Johnson E. Anchoring, activation and the construction of values. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1999;79:115–153. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1999.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Roberts TR, Goldstein CC, Miklosovic ME, Ubel PA. Trading people versus time: What is the difference? Popul Health Metr. 2005a;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Roberts TR, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Why people refuse to make tradeoffs in person tradeoff elicitations: a matter of perspective? Med Decis Making. 2007;27:266–280. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. The impact of considering adaptation in health state valuation. Soc Sci Med. 2005b;61:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctor J, Bleichrodt H, Lin HJ. Health utility bias: a systematic review and meta-analytic evaluation. Med Decis Making. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0272989X07312478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P. The measurement of health-related quality of life for use in resource allocation decisions in health care. In: Culyer A, Newhouse J, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 1724–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P, Olsen JA, Menzel P, Richardson J. An inquiry into the different perspectives that can be used when eliciting preferences in health. Health Econ. 2003;12:545–551. doi: 10.1002/hec.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan PA, Olsen JA. Equity in health: The importance of different health streams. J Health Econ. 2001;20:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Etches V, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, Manuel D. Measuring population health: A review of indicators. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:29–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EuroQoL Group. EuroQoL - A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeny D. The utility approach to assessing population health. In: Murray CJL, et al., editors. Summary Measures of Population Health. Concepts, Ethics, Measurement and Applications. Geneva: WHO; 2002. pp. 515–528. [Google Scholar]

- Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, DePauw S, Denton M, Boyle M. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40:113–128. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MJ, Gold GM. Summarizing population health: directions for the development and application of population metrics. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol Methods. 2004;9:466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler F. Applied social research methods series. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1995. Improving survey questions: design and evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Frick U, Rehm J, Fichter M, Koloska R. Therapeutische Rollenorientierung und soziale Repräsentationen von stationären Alkoholismus-Patienten. Z f Soziologie. 1988;17:218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fried TR, O’Leary J, Van Ness P, Fraenkel L. Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1007–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, Barr RD. The Health Utilities Index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med. 2001;33:375–384. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafni A. The Standard Gamble method: what is being measured and how it is interpreted. Health Services Research. 1994;29:207–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer G, Todd PM ABC Research Group. Simple heuristics that make us smart. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg J. Being there is important, but getting there matters too: The role of path in the valuation process. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:323–337. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06291680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green C. On the societal value of health care: What do we know about the person trade-off technique? Health Econ. 2001;10:233–243. doi: 10.1002/hec.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green C, Brazier J, Deverill M. Valuing health-related quality of life. A review of health state valuation techniques. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17:151–165. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice PH. Logic and conversation. In: Cole P, Morgan JL, editors. Syntax and Semantics. New York: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerl M. Experimental realism in social psychological research. [Experimentelle realitätsnähe in der sozialpsychologischen Forschung] Z f Sozialpsychol. 2000;31:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig R. Psychologie, experimentelle Ökonomie und die Frage, was gutes Experimentieren ist. Z f Experimentelle Psychologie. 1998;45:2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Economica. 1979;47:263–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A, Slovic P. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Klein M, Dülmer H, Ohr D, Quandt M, Rosar U. Response sets in the measurement of values: a comparison of rating and ranking procedures. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 2004;16:474–483. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster T. Consumer demand: a new approach. New York: Columbia University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lancsar E, Louviere J, Flynn T. Several methods to investigate relative attribute impact in stated preference experiments. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1738–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenert L, Cher D, Goldstein M, Bergen M, Garber A. The effect of search procedures on utility elicitations. Med Decis Making. 1998;18:76–83. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9801800115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell I. Measuring health - a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell I, Spasoff R, Kristjansson B. On the classification of population health measurements. Am J Public Health. 2005;94:388–393. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh CN, Connor Gorber S, Bernier J, Berthelot JM. Eliciting Canadian population preferences for health states using the Classification and Measurement System of Functional Health (CLAMES) Chronic Dis Can. 2007;28:29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M, Marks J. Commentary on the uses of summary measures of population health. In: Murray CJL, et al., editors. Summary measures of population health. Concepts, ethics, measurement and applications. Geneva: WHO; 2002. pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- McKie J, Richardson J. The rule of rescue. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2407–2419. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamee P. What difference does it make? The calculation of QALY gains from health profiles using patient and general population values. Healthy Policy. 2007;84:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T, Fukui T. Utilities measured by rating scale, time trade-off, and standard gamble: Review and reference for health care professionals. Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;12:160–178. doi: 10.2188/jea.12.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer D, Segal L. Comparing the incomparable? A systematic review of competing techniques for converting descriptive measures of health status into QUALY-weights. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:66–89. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07309642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez A. Progress and directions in refining the global burden of disease approach: a response to Williams. Health Econ. 2000;9:69–82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(200001)9:1<69::aid-hec493>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez A. on behalf of the WHO and World Bank . The global burden of disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard School of Public Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Salomon J, Mathers C. A critical examination of summary measures for population health. Bulletin of the WHO. 2000;78:981–994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Salomon J, Mathers C, Lopez A. Summary measures of population health: concepts, ethics, measurement and applications. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72:429–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL. Rethinking DALYs. In: Murray CJL, Lopez A, editors. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health; 1996. pp. 1–98. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B. Should substance use disorders be considered as categorical or dimensional? Addiction. 2006;101:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord E. The relevance of health state after treatment in prioritising between different patients. J Med Ethics. 1993a;19:37–42. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord E. The trade-off between severity of illness and treatment effect in cost-value analysis of health care. Health Policy. 1993b;24:227–238. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(93)90042-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord E. Concerns for the worse off: fair innings versus severity. Soc Sci Med. 2004;60:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord E. Severity of illness and priority setting: worrisome lack of discussion of surprising finding. J Health Econ. 2005;25:170–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J, Smith R. Theory versus practice: A review of ‘willingness-to-pay’ in health and health care. Health Econ. 2001;10:39–52. doi: 10.1002/1099-1050(200101)10:1<39::aid-hec563>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin D, Devlin N. Is there a case for using visual analogue scale valuations in cost-utility analysis? Health Econ. 2006;15:653–664. doi: 10.1002/hec.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto Prades JL. Is the person trade-off a valid method for allocating health care resources? Health Econ. 1997;6:71–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199701)6:1<71::aid-hec239>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: A measure of health status from the EuroQoL group. Ann Med. 2001;33:337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasiel E, Weinfurt K, Schulman K. Can prospect theory explain risk-seeking behavior by terminally ill patients? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:609–613. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Strack F. Kontrolltechniken. In: Hermann T, Tack W, editors. Methodologische Grundlagen der Psychologie. Gottingen: Hogrefe; 1994. pp. 508–555. [Google Scholar]

- Revicki D, Kaplan R. Relationship between psychometric and utility-based approaches to the measurement of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:477–487. doi: 10.1007/BF00422222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Wierzbicki M. Anchoring errors in clinical-like judgments. J Clin Psychol. 1990;46:358–365. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199005)46:3<358::aid-jclp2270460317>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J, Nord E. The importance of perspective in the measurement of Quality-adjusted Life Years. Med Decis Making. 1997;17:33–41. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9701700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, Bate A, van Teijlingen ER, Russell EM, Napper M, Robb CM. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5:1–186. doi: 10.3310/hta5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D, Torrance G. The utility of different health states as perceived by the general public. J Chronic Dis. 1978;7:347–358. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon J. Reconsidering the use of rankings in the valuation of health states: A model for estimating cardinal values from ordinal data. Popul Health Metr. 2003;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach D. The equivalence of numbers: The social value of avoiding health decline: An experimental web-based study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2002;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach D. Are preferences for equity a matter of perspective? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:449–459. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05276861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Sudman S. Answering questions: Methodology for determining cognitive and communicative processes in survey research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Cognition and communication: Judgmental biases, research methods and the logic of conversation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Clore G. Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychol Inq. 2003;14:296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Hippler HJ. What response scales may tell your respondents: informative functions of response alternatives. In: Hippler HJ, Schwarz N, Sudman S, editors. Social information processing and survey methodology. Berlin: Springer; 1987. pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzinger M, Lanoe J, Nord E, Durand-Zaleski I. Lack of multiplicative transitivity in person trade-off responses. Health Econ. 2004;13:171–181. doi: 10.1002/hec.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Keeler E, Unützer J, Lenert L, Wells KB. Relationship between age and patients’ current health state preferences. Gerentologist. 1999;39:271–278. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer A. A test of the QALY model when health varies over time. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1697–1706. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalmeier PF, Lamers LM, Busschbach JJ, Krabbe PF. On the assessment of preferences for health and duration. Maximal endurable time and better than dead preferences. Med Care. 2007;45:835–841. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180ca9ac5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiggelbout A, de Vogel-Voogt E. Health state utilities: A framework for studying the gap between the imagined and the real. Value Health. 2008;11:76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk E, Pickee S, Ament A, Busschbach J. Equity in health care prioritisation: an empirical inquiry into social value. Health Policy. 2005;74:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthard M, Essink-Bot ML, Bonsel GJ. Disability weights for diseases in the Netherlands. Rotterdamn: Erasmus University Rotterdam; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sudman S, Bradburn N, Schwarz N. Thinking about answers: The application of cognitive processes to survey methodology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone LL. A law of comparative judgement. Psychol Rev. 1927;34:273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya A. The time trade-off method from the societal perspective. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:578. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya AJ, Brazier J, Roberts J. Comparison of valuation methods used to generate the EQ-5D and the SF-6D value sets. J Health Econ. 2006;25:334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubel P, Richardson J, Baron J. Exploring the role of order effects in person trade-off elicitations. Health Policy. 2002;61:189–199. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubel PA, Richardson J, Menzel P. Societal value, the person trade-off, and the dilemma of whose values to measure for cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2000;9:127–136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(200003)9:2<127::aid-hec500>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubel PA, Spranca MD, Dekay ML, Hershey JC, Asch DA. Public preferences for prevention versus cure: What if an ounce of prevention is worth only an ounce of cure? Med Decis Making. 1998;18:141–148. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9801800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün TB, Rehm J, Chatterji S, Saxena S, Trotter R, Room R, Bickenbach J. Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. Lancet. 1999a;354:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün TB, Saxena S, Rehm J, Bickenbach J. Are disability weights universal? WHO/NIH Joint Project CAR Study Group. Lancet. 1999b;354:1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Maas P. How summary measures of population health are affecting health agendas. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nooten F, Brouwer W. The influence of subjective expectations about length and quality of life on time trade-off answers. Health Econ. 2004;13:819–823. doi: 10.1002/hec.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Osch S, Stiggelbout A. Understanding VAS valuations: Qualitative data on the cognitive process. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:2171–2175. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-6808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Osch S, Stiggelbout A. The construction of standard gamble utilities. Health Econ. 2008;17:31–40. doi: 10.1002/hec.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wänke M, Schwarz N, Noelle-Neumann E. Asking comparative questions: the impact of the direction of comparison. Public Opin Q. 1995;59:347–372. [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Survey. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman V, Mooney G, Berry G, Tang K. Involving the general public in priority setting: Experiences from Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1001–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M. National Center for Health Statistics. To develop a research agenda and research resources for health status assessment and summary health measures. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2003. On the policy implications of summary measures of health status; pp. 151–189. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/otheract/IAWG/NCHS_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Moncur M, Gabriel S, Tosteson AN. Assessing values for health: numeracy matters. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:382–390. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 1993 -- Investing in Health. New York: World Bank/Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Smith DM, Ubel PA, Fagerlin A. Validation of the Subjective Numeracy Scale: Effects of low numeracy on comprehension of risk communication and utility elicitations. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:663–671. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07303824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]