Abstract

Erythropoietin (EPO) is typically known for its role in erythropoiesis, but is also a potent neurotrophic/neuroprotective factor for spinal motor neurons. Another trophic factor regulated by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), signals via ERK and Akt activation to elicit long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation (pMF). Since EPO also signals via ERK and Akt activation, we tested the hypothesis that EPO elicits similar pMF. Using retrograde labeling and immunohistochemical techniques, we demonstrate in adult, male, Sprague-Dawley rats that EPO and its receptor, EPO-R, are expressed in identified phrenic motor neurons. Intrathecal EPO at C4 elicits long-lasting pMF; integrated phrenic nerve burst amplitude increased >90 min post-injection (63±12% baseline 90 min post-injection; p<0.001). EPO increased phosphorylation (and presumed activation) of ERK (1.6 fold vs controls; p<0.05) in phrenic motor neurons; EPO also increased pAkt (1.6 fold vs controls; p<0.05). EPO-induced pMF was abolished by the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 and the PI3 kinase/Akt inhibitor LY294002, demonstrating that ERK MAP kinases and Akt are both required for EPO-induced pMF. Pre-treatment with U0126 and LY294002 decreased both pERK and pAkt in phrenic motor neurons (p<0.05), indicating a complex interaction between these kinases. We conclude that EPO elicits spinal plasticity in respiratory motor control. Since EPO expression is hypoxia-sensitive, it may play a role in respiratory plasticity in conditions of prolonged or recurrent low oxygen.

INTRODUCTION

The neural network controlling breathing utilizes multiple strategies to maintain an adequate oxygen supply, including negative feedback, feed-forward, and adaptive control strategies (i.e. neuroplasticity; Mitchell and Johnson, 2003). Growth/trophic factors play key roles in many forms of respiratory plasticity (Golder, 2008; Mitchell and Johnson, 2003; Spedding and Gressens, 2008). For example, new synthesis of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and activation of its high affinity receptor underlie a form of spinal respiratory plasticity: phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF) following acute intermittent hypoxia (Baker-Herman et al., 2004). Though BDNF signals via ERK MAP kinases and Akt (Golder, 2008; Reichardt, 2006), only ERK activation is required for pLTF (Hoffman and Mitchell, unpublished observations).

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a hypoxia sensitive growth/trophic factor (Forsythe et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1995) originally known for its angiogenic (Connolly et al., 1989) and cell permeabilization properties (Senger et al., 1986). Spinal VEGF receptor activation elicits long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation (pMF) via an ERK and Akt dependent mechanism (Dale-Nagle et al., 2011).

Erythropoetin (EPO) is another hypoxia-sensitive protein with hematopoietic properties (Bert, 1882; Bert, 1878; Jourdanet, 1875). EPO and its receptor (EPO-R) are expressed in the mammalian central nervous system (Masuda et al., 1994; Digicaylioglu et al., 1995; Marti et al., 1996; Morishita et al., 1997; Bernaudin et al., 1999; Brines et al., 2000; Juul, 2000), where they are regulated by HIF-1α (Wang et al., 1995; Wang and Semenza, 1995); recent evidence suggests additional regulation via HIF-2α (Yeo et al., 2008). EPO induces hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Weber et al., 2002) including long-term potentiation (Adamcio et al., 2008), and is neuroprotective for hippocampal (Sirén et al., 2001; Xiong et al., 2010) and motor neurons (Celik et al., 2002; Iwasaki et al., 2002; Mennini et al., 2006; Koh et al., 2007; Naganska et al., 2010). EPO-induced neuroprotection is ERK and Akt-dependent (Killic et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2010), consistent with known downstream signaling from EPO receptor activation (Bao et al., 1999; Gobert et al., 1995).

EPO modulates breathing via actions on peripheral chemoreceptors and brainstem respiratory neurons (Soliz et al., 2005; 2007a), and contributes to ventilatory acclimatization to chronic hypoxia (Gassmann et al., 2009; Gassmann and Soliz, 2009). Soluble EPO-R (sEPO-R) is a negative regulator of EPO binding that attenuates ventilatory acclimatization (Powell et al., 1998), demonstrating long-lasting EPO effects on the control of breathing (Soliz et al., 2007b). The impact of spinal EPO on the control of breathing has not been previously investigated.

Since EPO signals via ERK (Gobert et al., 1995; Miura et al., 1994a) and/or Akt (Damen et al., 1993; He et al., 1993; Mayeux et al., 1993; Miura et al., 1994b), we tested the hypotheses that: 1) spinal EPO receptor activation elicits pMF; 2) EPO and EPO receptors are expressed in phrenic motor neurons; 3) spinal EPO increases phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules in phrenic motor neurons (eg. ERK and Akt); and 4) EPO-induced pMF requires spinal ERK and Akt activity.

METHODS

Experimental Animals

Three to five month-old adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (colony 218A, Harlan; Indianapolis, IN) were used for all experiments. Animals were double housed with food and water ad libitum in a temperature and light controlled environment (12h light/dark cycle, daily humidity and temperature monitoring). All protocols were approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin.

Immunohistochemical Experiments

Retrograde labeling of phrenic motor neurons

To identify phrenic motor neurons, 12 rats were used for retrograde labeling with Cholera toxin B subunit via intrapleural injection (Mantilla et al., 2009). Isoflurane anesthesia was induced in a closed chamber and maintained via nose cone (1.5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen). 25μl of 0.5% Cholera toxin B subunit (dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline; List Biological Laboratories; Campbell, CA) was injected into the right and left thoracic cavities (6 mm deep, 5th intercostal space) using a 25-μl Hamilton syringe and a custom-made needle (6mm, 23g, semi-blunt). Rats were monitored for signs of respiratory compromise, but none were evident. Three days post-surgery, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and prepared for intrathecal drug injections (see below).

EPO and EPO-R immunostaining

Naïve rats (n=5) were euthanized with an overdose of Beuthanasia (0.3ml; i.p.) and perfused transcardially with ice-cold 0.01M buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 4% buffered paraformaldehyde. Cervical spinal cords were excised, post-fixed overnight and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4°C until they sank. Transverse sections (40 μm) of C4-5 ventral horn (including the phrenic motor nucleus) were cut using a freezing microtome (Leica SM 200R, Germany). In brief, free-floating sections were washed in 0.1 M Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton-X100 (TBS-Tx; 3 × 5 min) and incubated in TBS containing 1% H2O2 for 30 min. After washing (3 × 5 min) in TBS-Tx, tissues were blocked with 5% normal goat serum (NGS) at room temperature (RT) for 60 min. Staining was performed by incubating sections with rabbit polyclonal anti-erythropoietin (EPO; H-162; 1/500; Santa-Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-erythropoietin receptor (EPO-R; C-20; 1/500; Santa-Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) at 4°C overnight. Both EPO and EPO-R antibodies are widely used and their specificity has been tested in previous studies (Mazur et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2010; Anderson et al., 2009; Sanchez et al., 2009). The sections were washed in TBS-Tx and incubated in biotinylated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:1,000; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA). Conjugation with avidin-biotin complex (Vecstatin Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) was followed by visualization with 3,3’-diaminobenzidinehydrogen peroxidase (DAB, Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were washed in TBS, placed on gelatin-coated slides, dried, dehydrated in a graded alcohol series, cleared with xylenes and mounted with Eukitt medium.

To localize EPO and EPO-R in phrenic motor neurons, free-floating sections from CtB injected rats were washed in TBS-Tx (3 × 5 min) and blocked with 5% normal donkey serum (NDS) at room temperature (RT) for 60 min. Staining was performed by incubating sections with either rabbit polyclonal anti-EPO (H-162; 1/200; Santa-Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) or rabbit EPO receptor (C-20; 1/200; Santa-Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) with anti-cholera toxin B fragment (CtB) antibody (Nondenatured Cholera Toxin B; goat polyclonal; 1/10,000; Calbiochem) at 4°C overnight. The sections were washed in TBS-Tx (3 × 5 min) and incubated in conjugated donkey anti-rabbit green fluorescent Alexa 488 (1:500; Molecular Probes; Eugene, Oregon) or donkey anti-rabbit green fluorescent Alexa 488 (1:500; Molecular Probes) and donkey anti-goat red fluorescent Alexa 594 (1:500; Molecular Probes). Stained tissues were mounted under glass using anti-fade solution (Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent; Invitrogen; Oregon). All images were captured and analyzed with a digital camera (Qcapture Pro 6.0, QImaging; Surrey, BC, Canada). Photomicrographs were created with Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe System; San Jose, CA).

All images presented in figures received equivalent adjustments to brightness/contrast and exposure. Semi-quantitative analysis (see below) was performed in a blinded fashion prior to making any adjustments for white balance, gain, gamma or offset. Sections incubated without primary or secondary antibodies or served as negative controls.

Intrathecal EPO injections

After induction in a closed chamber, isoflurane anesthesia was maintained initially via nose cone. The rats were then tracheotomized, pump ventilated (2.5ml; Rodent Ventilator, model 683; Harvard Apparatus; South Natick, MA) and isoflurane anesthesia was continued through the ventilator for the duration of surgery (3.5% isoflurane in 50% O2). Upon completion of surgery, rats were converted to urethane anesthesia via injection into a tail vein catheter (1.8g/kg). To replicate the surgical preparation during neurophysiological experiments (see below), rats received bilateral vagotomy, the femoral artery was tied off, and phrenic and hypoglossal nerves were transected. An intrathecal silicone catheter (2 French; Access Technologies; Skokie, IL) was placed with the tip on the dorsal surface of C4 after a C2 laminectomy and durotomy. Pancuronium bromide (2.5mg/kg, i.v.) was used to induce paralysis. Body temperature was maintained within 1 °C of the initial measurement (rectal probe; Traceable™, Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA, USA) with a custom built, temperature-controlled surgical table. Petco2 was maintained between 41-44mmHg as measured with a flow-through capnograph with sufficient response time to measure end-tidal CO2 in rats (Capnogard, Novametrix; Wallingford, CT). Rats received one of 4 intrathecal drug treatments: 1) 10μl of Erythropoietin (recombinant human; tissue culture grade; doses ranged from 4-30 international units; R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN) dissolved in 0.1% bovine serum albumen (BSA) and artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 120mM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 2mM CaCl, 2mM MgCl, 23mM NaHCO3, 10mM glucose bubbled with CO2). 2) 12μl of U0126, a MEK inhibitor (dissolved in 100% DMSO and diluted with aCSF to a final concentration of 100mM in 20%DMSO; Promega; Madison, WI), before EPO, 3) 12μl of LY294002, a PI3Kinase inhibitor (dissolved in 100% DMSO and diluted with aCSF to a final concentration of 100mM in 20% DMSO; Tocris Bioscience; Ellisville, MO) before EPO, 5) or 10μl of 0.1%BSA in aCSF. After 15 min, rats were perfused and fixed for phospho-ERK and phospho-Akt immunohistochemistry.

Phospho-ERK, phospho-Akt and Cholera toxin subunit B immunostaining

To identify ERK and Akt phosphorylation in the phrenic motor nucleus following intrathecal EPO, with or without inhibitors of MEK (UO126) or PI3K (LY294002), C4-C5 spinal tissues from CtB injected rats were blocked in normal donkey serum (NDS) for 60 min, and then incubated in phospho-ERK (1/500; Cell Signaling Technologies; Beverly, MA) or phospho-Akt antibodies (1/500, Cell Signaling Technologies) at 4°C overnight. The sections were washed in TBS-Tx and incubated in biotinylated secondary donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1:1,000; Jackson Immunoresearch, PA). Conjugation with avidin-biotin complex (Vecstatin Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) was followed by visualization with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine-hydrogen peroxidase (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After washing with TBS-Tx (3 × 5 min), tissues were labeled with anti-CtB antibody (Non-denatured CtB; goat polyclonal; 1/10,000; Calbiochem) overnight. The tissues were then incubated in conjugated donkey anti-goat red fluorescent Alexa 488 (1:500; Molecular Probes; Eugene, Oregon) at room temperature for 60 min to visualize CtB. Stained tissues were mounted under glass using anti-fade solution (Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent, Invitrogen; Oregon). Phospho-ERK and phospho-Akt protein expression (brown) were examined in CtB back-labeled phrenic motor neurons (green) with an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon).

Quantification and analysis of photomicrographs

Eight sections from each rat (n=3 rats per group) at the C4-C5 segmental level were used for investigator blinded immunohistochemical analyses. Phrenic motor neurons were identified as a cluster of large, fluorescing neurons in the mediolateral C4 ventral horn (Dale-Nagle et al., 2011; Mantilla, et al., 2009; Boulenguez et al., 2007). Digital photomicrographs of immuno-reactive labeling in the region of the phrenic motor nucleus were taken with the 20x objective lens (Qcapture Pro 6.0, Surrey, BC, Canada). Densitometry was performed by circumscribing the phrenic motor nucleus based on CtB labeling, and determining the intensity of phospho-ERK and phospho-Akt immunostaining using NIH ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Images were converted to 8-bit resolution, and the threshold was set between 120-160 during all analyses. The optical density (OD) was measured within circumscribed phrenic motor neurons, and expressed as an average OD per unit area for each individual cell. For each cell, the OD of phospho-ERK and phospho-Akt immunoreactivity was expressed as a fraction of the average OD of all cells in vehicle treated rats. Thus, the mean OD in control rats is expected to be 1.0, with a variance that reflects variations among cells within group. In EPO treated rats, the OD was expressed as a ratio to the average of vehicle treated cells. This normalized OD served as a measure of relative protein concentration of phospho-ERK and phospho-Akt within CtB labeled cells. Data were compared between treatment groups using one-way ANOVA. Differences were considered significant if p<0.05. All values are expressed as means ± 1 SEM.

Neurophysiology experiments

Surgical Preparation

Isoflurane anesthesia (3.5% isoflurane in 50% O2) was induced in a closed chamber and maintained with a nose cone. Rats were tracheotomized and pump ventilated (2.5ml, Rodent Ventilator, model 683; Harvard Apparatus; South Natick, MA, USA). Following surgery, rats were slowly converted to urethane anesthesia (1.8g/kg) via tail vein catheter. To eliminate pulmonary stretch-receptor feedback and, thus, entrainment of respiratory activity with the ventilator, bilateral vagotomy was performed. Arterial blood taken via femoral artery catheterization enabled blood gas analysis throughout the experiment. After C2 laminectomy and durotomy, one or two intrathecal silicone catheters (2 French; Access Technologies, Skokie, IL) were placed with their tips resting on the dorsal surface of the C4 spinal segment. The left phrenic nerve was isolated via dorsal approach, cut distally, de-sheathed, submerged in mineral oil and placed on bipolar silver electrodes. Rats were paralyzed with pancuronium bromide (2.5mg/kg, i.v.) after confirming adequate anesthesia (no purposeful movements or cardio-respiratory responses to toe pinch). Body temperature was measured with a rectal probe (Traceable™, Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and maintained within ± 1.0°C of baseline temperature via a custom built, temperature-controlled surgical table. A flow-through capnograph with a sufficient response time to measure end-tidal CO2 in rats (Capnogard, Novametrix; Wallingford, CT; USA) was utilized to acquire end-tidal CO2. Blood samples were drawn at specified times into a heparinized plastic capillary tube (Radiometer Medical Aps, Copenhagen, Denmark; 250 × 125μl cut in half) to monitor arterial blood gases (PaO2 and PaCO2), pH and base excess (ABL 800Flex, Radiometer; Copenhagen, Denmark). Blood pressure and acid/base balance were maintained via continuous intravenous fluid infusion (1:3.75:3 by volume of NaHCO3/Lactated Ringer’s/Hetastarch; 1.5-2.2 ml/hr).

Phrenic nerve activity was amplified (x10,000: A-M Systems, Everett, WA), band-pass filtered (100Hz to 10kHz), rectified, processed with a moving averager (CWE 821 filter; Ardmore, PA; time constant: 50ms), and sampled at a rate of 4kHz. WINDAQ data-acquisition system (DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH) was used to analyze the digitized, integrated signal. Peak integrated phrenic burst frequency and amplitude and mean arterial pressure (MAP) were analyzed in 60s bins directly before blood samples were taken. Data were included only if PaCO2 was maintained within ± 1.5mmHg of baseline, base excess was within ± 5 of baseline and the change in MAP from the beginning to the end of a protocol was less than 30mmHg. Frequency data and nerve burst amplitudes are expressed as percentage change from baseline.

The apneic threshold (the CO2 level at which neural signals cease to fire) was determined at least one hour after conversion to urethane anesthesia by decreasing inspired CO2 and/or increasing ventilator frequency. Baseline was established by maintaining end-tidal PCO2 between 1-2mmHg above the phrenic burst recruitment threshold (the PaCO2 at which respiratory activity resumes; Bach and Mitchell, 1996). Baseline blood was drawn after 25 min of stable nerve recordings to establish a point of comparison for subsequent blood gas measurements. The rats then received one of six treatments (outlined below) and arterial blood samples were taken 15, 30, 60 and 90 min following intrathecal injections. All electrophysiological data were analyzed with a repeated measures, 2-way ANOVA (SigmaStat 2.03).

Drug administration

Six treatment protocols were used in the electrophysiological study: 1) 10μl of Erythropoietin (recombinant human; tissue culture grade; doses ranged from 4-30 international units; R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN) dissolved in 0.1% bovine serum albumen (BSA) and artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 120nM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 2mM CaCl, 2mM MgCl, 23mM NaHCO3, 10mM glucose bubbled with CO2). 2) 12μl of U0126, a MEK inhibitor (dissolved in 100% DMSO and diluted with aCSF to a final concentration of 100mM in 20%DMSO; Promega; Madison, WI), before EPO, 3) U0126 without EPO, 4) 12μl of LY294002, a PI3Kinase inhibitor (dissolved in 100% DMSO and diluted with aCSF to a final concentration of 100mM in 20% DMSO; Tocris Bioscience; Ellisville, MO) before EPO, 5) LY294002 without EPO 6) or just 10μl vehicle (0.1%BSA in aCSF). All drugs were slowly administered intrathecally over the course of two min. When two drugs were used in the same protocol (e.g. U0126 + EPO), the inhibitor was given 15-20 min prior to EPO injections. When working with EPO, all syringes, vials, and catheters were incubated beforehand with vehicle to prevent protein binding. The optimal EPO dose used was chosen based on a preliminary dose/response curve.

RESULTS

Immunohistochemical experiments

EPO and EPOR are expressed in identified phrenic motor neurons

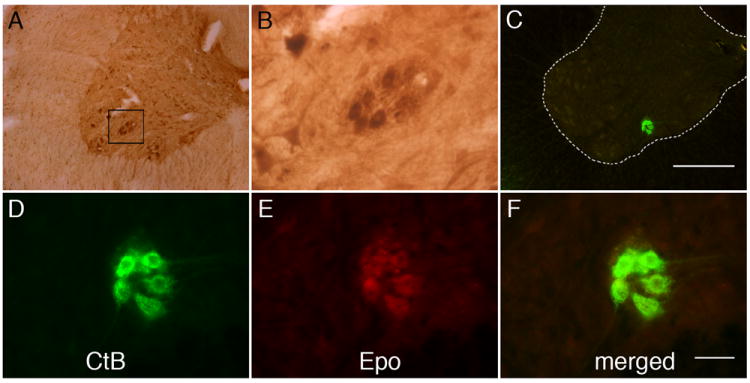

DAB staining in C4 ventral horn (i.e. the region of the phrenic motor nucleus; Boulenguez et al., 2007; Goshgarian and Rofols, 1981; Mantilla et al., 2009), revealed EPO immunolabeling in presumptive phrenic motor neurons (Figure 1, A-B). In rats that received CtB injections, EPO immunolabeling co-localized with CtB staining (i.e. within phrenic motor neurons; n=5). CtB positive cells (Figure 1, C-F) are shown in coronal sections of C4 within the mediolateral ventral horn. EPO immunostaining is also found in smaller cells, possibly interneurons (Lane et al., 2008) or other non-identified somatic motor neurons.

Figure 1.

Representative images of EPO immunostaining in C4 phrenic motor neurons. (A) DAB staining revealed EPO expression in large, putative phrenic motor neurons (black box) and possible interneurons. (B) Higher magnification of black box from panel A. (C) Cholera toxin subunit B (CtB) was intrapleurally injected to localize phrenic motor neurons (green cells in ventral horn). Scale bar, 400μm. (D-F) EPO (E) is expressed in CtB labeled phrenic motor neurons (see merged image, D) and surrounding neuropil. Scale bar in F is 50μm.

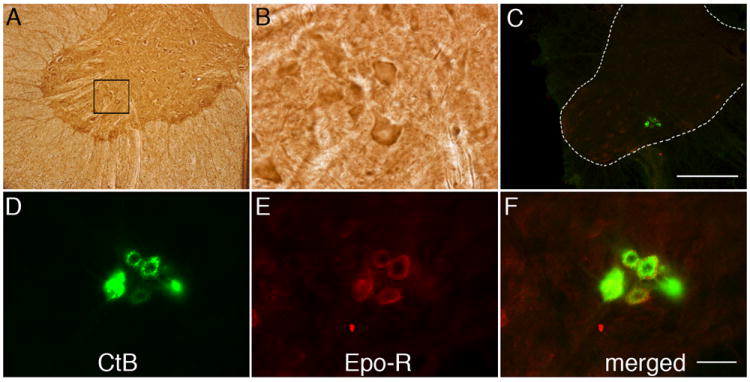

EPO-R is also revealed via DAB staining in putative phrenic motor neurons (Figure 2, A-B) and, in rats receiving CtB injections, co-localizes with CtB immunoreactivity. Thus, both EPO and EPO-R are expressed in identified phrenic motor neurons (Figure 2, C-F).

Figure 2.

Representative images of EPO receptor (EPO-R) immunostaining in C4 phrenic motor neurons. (A) DAB staining revealed EPO-R expression in large, putative phrenic motor neurons (black box) and interneurons. (B) Higher magnification of black bock from panel A. (C) CtB labeled phrenic motor neurons (green cells in C4 ventral horn). Scale bar, 400μm. (D-F) EPO-R (E) is expressed in CtB labeled phrenic motor neurons (D; see merged image in F) and the surrounding neuropil. Sections were incubated without primary or secondary antibody as negative controls. Scale bar in F is 50μm.

EPO increases phospho-ERK and phospho-Akt in phrenic motor neurons

Since EPO-R is expressed in phrenic motor neurons, and EPO-R signals via ERK MAP kinases and Akt, we hypothesized that intrathecal EPO injections at C4 would increase phosphorylation of ERK and Akt in the phrenic motor nucleus. We further hypothesized that pre-treatment with the MEK inhibitor U0126 or the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 would attenuate EPO-induced increases in pERK and pAkt, respectively.

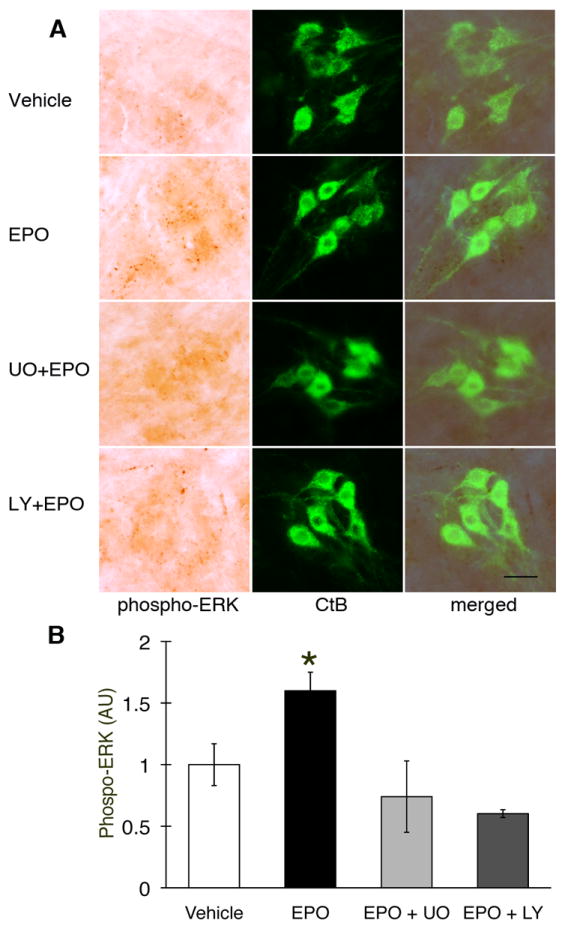

Phospho-ERK staining was observed in putative C4 phrenic motor neurons of naive rats after vehicle injections (Figure 3A), and in CtB backlabeled phrenic motor neurons (Figure 3A, merged panels). Phospho-ERK labeling increased following EPO injections, but the increase was attenuated by pretreatment with U0126 (Figure 3A). Densitometric analysis confirmed increased pERK expression following EPO treatment (Figure 3B; 1.6±0.2 fold vs vehicle; p<0.05), and U0126 pre-treatment abolished this EPO-induced increase in pERK (0.7±0.3 fold). Surprisingly, LY294002 pre-treatment also attenuated the EPO-induced increase in pERK within phrenic motor neurons (Figure 3B; 0.6±0.03 fold).

Figure 3.

Phospho-ERK expression in C4 phrenic motor neurons after intrathecal EPO injection. (A) Phospho-ERK (dark brown staining) is expressed in C4 phrenic motor neurons and is colocalized with CtB (upper row, vehicle). pERK is upregulated after intrathecal EPO injection (middle row) and this upregulation is blocked by U0126 (UO; MEK/ERK inhibitor; 2nd row from bottom) and the PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 (LY; bottom row). Densitometry in CtB labeled phrenic motor neurons showed increased phospho-ERK after intrathecal EPO versus vehicle treated rats. Pre-treatment with U0126 and LY294002 brings pERK protein expression to vehicle levels. Data are means ± 1 SEM. * p < 0.05 versus all other groups. Scale bar, 100 μm.

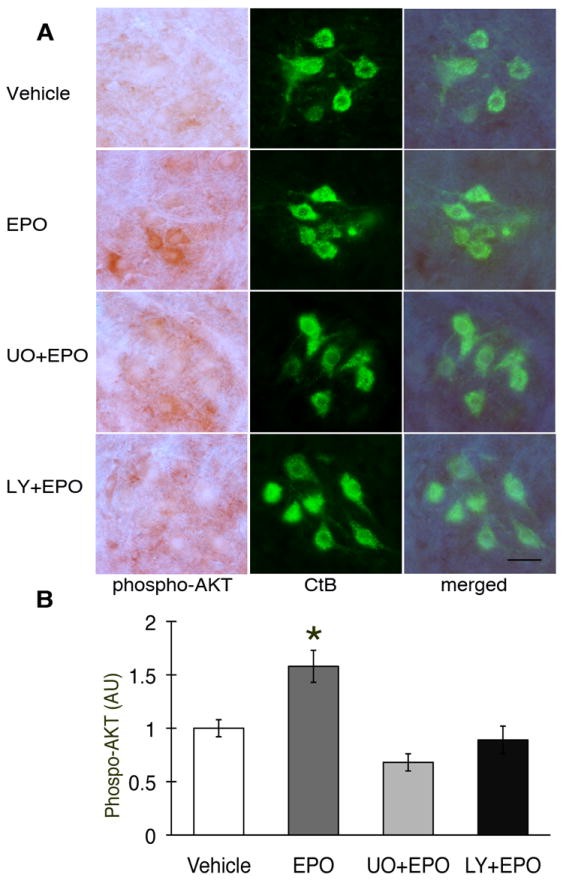

Phospho-Akt also co-localized with CtB, confirming that this protein is expressed in phrenic motor neurons (Figure 4A). Intrathecal EPO increased Akt phosphorylation (Figure 4A). Pre-treatment with LY294002 decreased pAkt below control levels. Densitometric analysis showed that the increase in pAkt after EPO treatment was significant (Figure 4B; 1.6±0.2 fold vs. vehicle; p<0.05). After pre-treatment with LY294002, pAkt expression was attenuated (Figure 4B; 0.7±0.1 fold; p<0.05). Pre-treatment with U0126 also brought pAkt levels below that of rats treated with EPO alone (Figure 4B; 0.9±0.1; p<0.05), indicating a complex interaction between these proteins.

Figure 4.

Phospho-Akt expression in C4 phrenic motor neurons after intrathecal EPO injection. (A) Phospho-Akt (dark brown staining) is expressed in C4 phrenic motor neurons and is co-localized with CtB back-labeled phrenic motor neurons. pAkt is upregulated after EPO injection (middle rows), and that upregulation is blocked after LY294002 or U0126 pre-treatment (bottom two rows) (B) Densitometry in CtB positive phrenic motor neurons showed increased phospho-Akt after intrathecal EPO versus vehicle treated rats (p<0.05). pAkt is at control levels after pre-treatment with U0126 (UO), and after LY294002 (LY; p<0.05). Data are means ± 1 SEM. * p<0.05 versus EPO alone; # p<0.05 versus vehicle. Scale bar, 100μm

Cervical EPO upregulates both pERK and pAkt within phrenic motor neurons. Pre-treatment with the MEK/ERK inhibitor reversed increases in both pERK and pAkt, while pre-treatment with a PI3Kinase inhibitor decreased both perk and pAkt levels. Thus, EPO activates ERK MAP kinases in phrenic motor neurons, although complex interactions between MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt are observed following EPO-R activation.

Electrophysiological experiments

Regulation of physiological variables under anesthesia

Variables measured during electrophysiological recordings are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences among experimental groups in body temperature, base excess, PaO2 (all measurements > 280mmHg) or PaCO2 (all maintained within 1.5mmHg). As noted in previous studies using this preparation (Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2008), mean arterial pressure decreases throughout a protocol. However, there were no significant differences in this decrease between treatment groups. Blood pH tended to increase over time, and though the increase reaches statistical significance: 1) it is not different between groups, and 2) the difference is sufficiently small that its biological significance is doubtful (0.007 pH units).

Table 1.

Body temperature, blood gases and mean arterial pressure (MAP) in each treatment group.

| Group | Tb (°C) | PaO2(mmHg) | PaCO2(mmHg) | pH | MAP(mmHg) | SBE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||||

| aCSF+0.1%BSA | 37.2±0.2 | 335.5±13.2 | 46.0±0.9 | 7.335±0.005 | 121.3±5.9 | -1.15±0.41 |

| 20IU EPO | 37.1±0.1 | 305.9±13.7 | 45.8±1.0 | 7.347±0.009 | 119.2±4.2 | -0.46±0.70 |

| U0126 + EPO | 36.9±0.2 | 319.6±17.8 | 46.4±1.1 | 7.343±0.008 | 119.1±2.6 | -0.50±0.42 |

| U0126 alone | 37.4±0.1 | 306.2±10.5 | 46.4±0.9 | 7.344±0.011 | 117.3±7.3 | -0.52±0.69 |

| LY294002+EPO | 37.1±0.2 | 310.0±14.1 | 47.5±0.4 | 7.335±0.008 | 116.8±4.6 | -0.46±0.57 |

| LY294002 alone | 37.7±0.1 | 292.3±13.3 | 46.1±0.8 | 7.333±0.008 | 110.7±7.1 | -1.36±0.61 |

| 15 min | ||||||

| aCSF+0.1%BSA | 37.6±0.1 | 318.5±7.2 | 46.3±0.9 | 7.335±0.005 | 109.3±3.2 | -1.13±0.55 |

| 20IU EPO | 37.2±0.1 | 297.4±14.8 | 45.5±1.4 | 7.344±0.010 | 116.4±5.8 | -0.61±0.85 |

| U0126 + EPO | 37.2±0.1 | 319.3±18.0 | 47.1±0.8 | 7.334±0.016 | 118.3±6.6 | -0.73±0.81 |

| U0126 alone | 37.2±0.2 | 289.3±7.2 | 47.2±0.7 | 7.341±0.019 | 112.0±15.8 | -0.10±1.05 |

| LY294002+EPO | 37.2±0.2 | 315.5±4.9 | 48.0±0.3 | 7.338±0.009 | 108.6±2.0 | 0.03±0.58 |

| LY294002 alone | 37.4±0.1 | 300.0±8.6 | 46.0±0.7 | 7.336±0.008 | 108.4±6.1 | -1.17±0.65 |

| 30 min | ||||||

| aCSF+0.1%BSA | 37.4±0.1 | 330.3±9.0 | 46.0±0.8 | 7.336±0.005 | 115.0±7.8 | -1.10±0.49 |

| 20IU EPO | 37.1±0.1 | 300.9±13.1 | 46.9±1.0 | 7.339±0.010 | 112.5±6.6 | -0.48±0.79 |

| U0126 + EPO | 37.1±0.1 | 307.2±15.1 | 47.0±1.1 | 7.343±0.013 | 112.8±5.6 | -0.18±0.63 |

| U0126 alone | 37.4±0.1 | 288.2±9.4 | 46.3±0.8 | 7.341±0.014 | 112.6±11.9 | -0.67±0.76 |

| LY294002+EPO | 37.3±0.1 | 304.0±8.1 | 48.0±0.7 | 7.337±0.008 | 107.6±2.5 | -0.10±0.58 |

| LY294002 alone | 37.3±0.1 | 294.4±9.6 | 46.3±0.8 | 7.335±0.009 | 102.2±5.5 | -1.04±0.64 |

| 60 min | ||||||

| aCSF+0.1%BSA | 37.0±0.2 | 324.8±8.5 | 45.9±1.0 | 7.340±0.010 | 111.3±7.5 | -0.92±0.74 |

| 20IU EPO | 37.2±0.1 | 305.5±12.3 | 45.8±1.0 | 7.339±0.009 | 109.2±6.6 | -1.01±0.71 |

| U0126 + EPO | 37.2±0.4 | 331.5±1.8 | 46.8±1.0 | 7.360±0.001 | 113.4±7.5 | 0.95±0.39 |

| U0126 alone | 37.2±0.1 | 300.7±6.8 | 45.9±0.7 | 7.343±0.017 | 108.7±10.9 | -0.75±0.91 |

| LY294002+EPO | 37.2±0.2 | 302.6±6.3 | 47.4±0.4 | 7.337±0.007 | 104.1±2.5 | -0.34±0.54 |

| LY294002 alone | 37.6±0.1 | 299.6±10.9 | 45.7±0.6 | 7.343±0.010 | 97.4±5.9 | -0.83±0.82 |

| 90 min | ||||||

| aCSF+0.1%BSA | 37.1±0.2 | 321.8±8.0 | 45.7±1.0 | 7.348±0.012* | 108.2±6.8* | -0.52±0.79 |

| 20IU EPO | 37.3±0.2 | 305.9±11.4 | 46.2±1.0 | 7.337±0.011* | 106.4±6.1* | -0.97±0.68 |

| U0126 + EPO | 37.0±0.1 | 320.2±11.9 | 46.6±1.4 | 7.355±0.012* | 102.6±6.4* | -0.10±1.03 |

| U0126 alone | 37.2±0.2 | 300.5±9.1 | 46.5±1.3 | 7.347±0.018 | 104.1±10.2* | -0.17±0.78 |

| LY294002+EPO | 37.2±0.2 | 299.4±3.9 | 47.8±0.6 | 7.338±0.007 | 100.6±2.1* | -0.16±0.31 |

| LY294002 alone | 37.1±0.2 | 301.7±8.7 | 45.9±0.8 | 7.353±0.014* | 101.4±6.4* | 0.02±1.03 |

All values expressed as mean ± SEM

significantly different from respective baseline measurement.

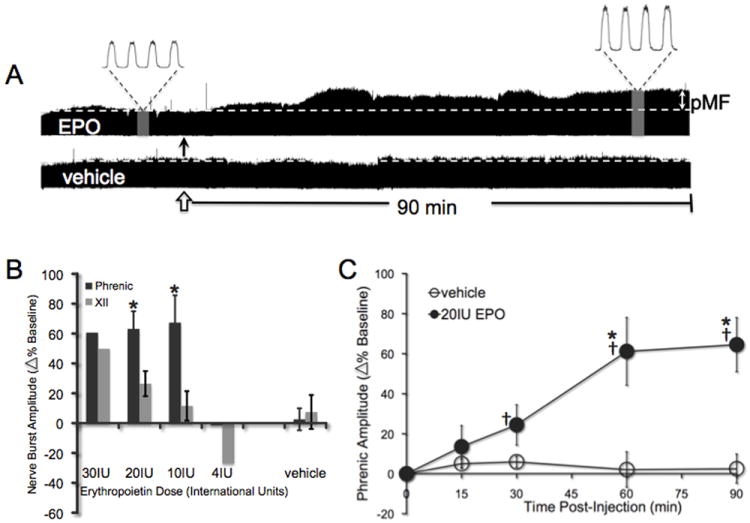

Cervical spinal EPO elicits dose-dependent pMF

Representative traces of phrenic nerve activity before, during and after EPO (10μl, 20 IU) or vehicle injections into the C4 intrathecal space are shown in Figure 5A. A preliminary EPO dose/response curve is shown in Figure 5B. The dose used in subsequent studies is the dose that affected phrenic motor output without inducing apparent hypoglossal motor facilitation, which would suggest spread to brainstem sites. Mean responses to this dose (20IU) are shown in Figure 5C. Phrenic burst amplitude was significantly increased from baseline by 30 min, and at all time points thereafter (all p<0.001; n=8), indicating pMF. Vehicle control rats did not exhibit significant changes in phrenic burst amplitude at any time (all p>0.05; n=6). Changes in phrenic burst amplitude following EPO injections were significantly greater than in vehicle treated rats after 60 min (all p<0.001). Changes in hypoglossal (XII) motor output were apparent only at higher doses of EPO (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Intrathecal EPO elicits a long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. A) Representative compressed phrenic neurograms showing either phrenic motor facilitation (pMF) after EPO injection (closed arrow) or no facilitation after vehicle injection (open arrow). B) Preliminary dose response curve for EPO; the dose subsequently used confers pMF without effects on hypoglossal (XII) activity. (*significantly different from XII motor facilitation at same dose; all p<0.001). C) The amplitude of integrated phrenic bursts increases from baseline after 10μl (20IU) EPO injections (n=8; solid circles), and is significantly different from vehicle controls at the same time point (10μl; n=6; open circles). All values are change in phrenic burst amplitude as percent baseline. Mean values ± 1 S.E.M. †: significantly different from baseline (all p<0.05); *significantly different from vehicle at the same time (all p<0.05).

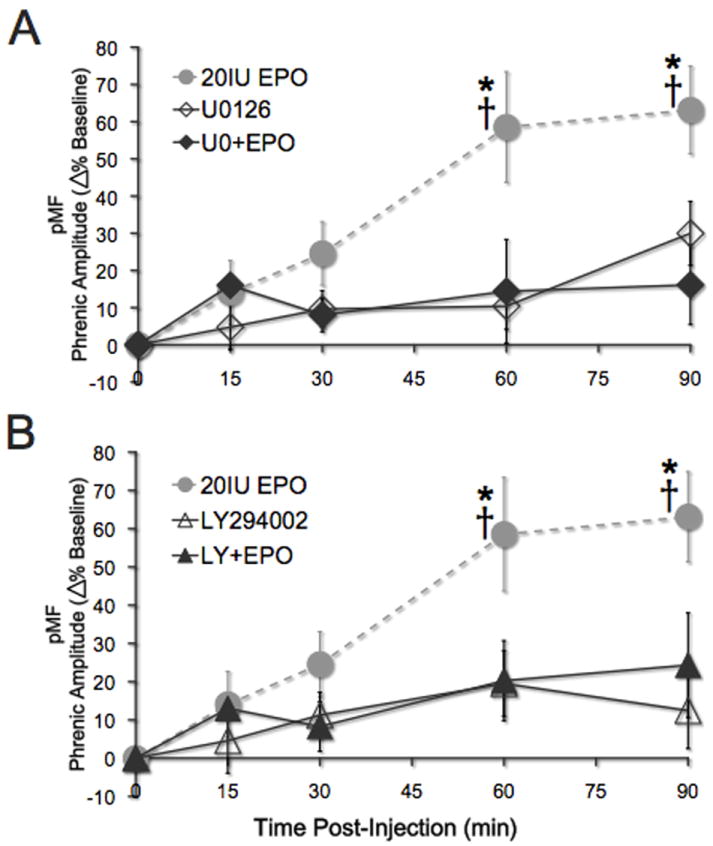

EPO-induced pMF requires spinal ERK activation

To test the hypothesis that EPO-induced pMF requires spinal ERK activation, rats were pretreated with the potent, cell-permeable MEK inhibitor U0126 prior to EPO administration. Pretreatment with U0126 abolished EPO-induced pMF for at least 90 min (16 ± 11% baseline; n=5; p>0.05 versus baseline; Figure 6A). pMF was significantly greater in rats treated with EPO alone at time points > 60 min post-injection (all p<0.008). U0126 alone had no effect on phrenic motor output at any time (all p>0.05). The U0126 dose was chosen based on an earlier study from our laboratory (Dale-Nagle et al., 2011).

Figure 6.

EPO-induced phrenic motor facilitation is dependent on spinal ERK and Akt activation. (A) Spinal EPO elicits pMF (grey dashed line; * significant difference from U0126+EPO and U0126 alone, all p<0.001; n=8). Pretreatment with the MEK inhibitor U0126 abolishes EPO-induced pMF; phrenic amplitude does not increase after baseline measurement (closed diamonds; n=5; all p>0.05). U0126 alone had no significant effect on phrenic motor output (open diamonds; n=6; all p>0.05) and there was no significant difference between U0126+EPO and U0126 alone (all p>0.05). B) Gray, dashed line shows EPO-induced pMF (*indicates significant difference from both LY294002+EPO and LY294002 alone). After treatment with PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002, EPO-induced pMF is abolished (closed triangles; n=5; all p>0.05). LY294002 alone had no significant effect on phrenic motor output (open triangles; n=7; all p>0.05) and there was no significant difference between LY294002+EPO and LY294002 alone (all p>0.05). All values are expressed as change in phrenic burst amplitude expressed as percent baseline. Mean values ± 1 S.E.M. †: significantly different from baseline (all p<0.001); *significantly different from vehicle at the same time point (all p<0.001).

EPO-induced pMF requires spinal Akt activation

To test the hypothesis that EPO-induced pMF requires spinal Akt activation, rats were pre-treated with the PI3 kinase inhibitor, LY294002, 20 min prior to EPO administration. Figure 6B illustrates that LY294002 pre-treatment abolished EPO-induced pMF at the 60-minute time point; there was no significant pMF 90 min post-EPO injection (24 ± 14% baseline; n=5; p>0.05 versus baseline). LY294002 alone had no effect on phrenic burst amplitude compared to baseline values or vehicle controls (12 ± 10%; n=7; p>0.05). LY294002 doses were chosen based on earlier studies (Dale-Nagle et al., 2011).

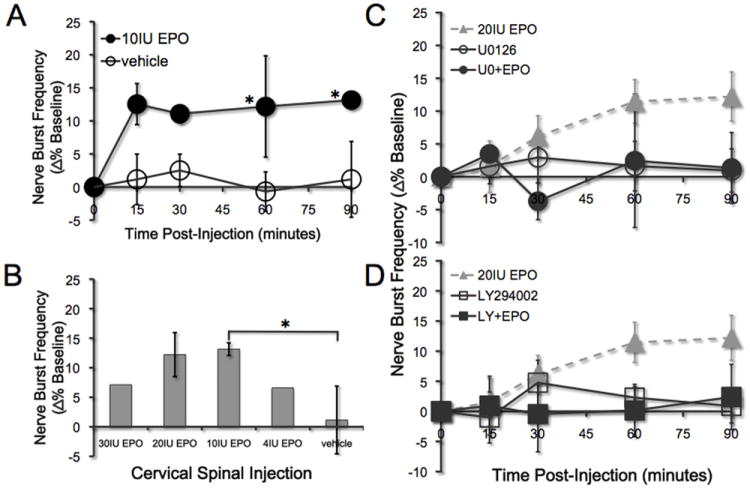

Spinal EPO elicits minimal phrenic burst frequency facilitation

Rats treated with 10IU EPO showed a slight but significant increase in respiratory burst frequency starting 60 min post-injection versus vehicle controls (Figure 7A; all p<0.027; n=3) and at all time points thereafter versus baseline (all p<0.027). However, neither higher (e.g. 30IU, n=2 and 20IU, n=8) nor lower doses of EPO (e.g. 4IU, n=2) elicited similar frequency facilitation (versus baseline or vehicle controls for at least 90 min post-EPO; all p>0.05; Figure 7B). Figures 7C and 7D illustrate that there were no significant differences (versus baseline or controls) in frequency for rats treated with U0126+EPO (n=5; p>0.05), U0126 alone (n=6; p>0.05), LY294002+EPO (n=5; p>0.05) or LY294002 alone (n=7; p>0.05). Thus, EPO-induced frequency facilitation is small (ca 13% above baseline) and variable (only observed at one, mid-range EPO dose).

Figure 7.

Effects of drug administration on nerve burst frequency. A) Intrathecal administration of 10IU EPO (closed circles) elicits a small facilitation in nerve burst frequency at 60 min post injection vs. baseline and vehicle controls (open circles; n=4; *all p<0.027). B) The only dose of EPO that elicited frequency facilitation was 10IU (*p<0.027). Higher (30IU, 20IU) and lower doses (4IU) did not elicit frequency facilitation (all p>0.05). C-D) No other treatments, including U0126, U0126+EPO, LY294002 nor LY294002+EPO elicited frequency facilitation versus baseline (all p>0.05). All values are expressed as change in nerve burst frequency (percent baseline). Mean values ± 1 S.E.M.

DISCUSSION

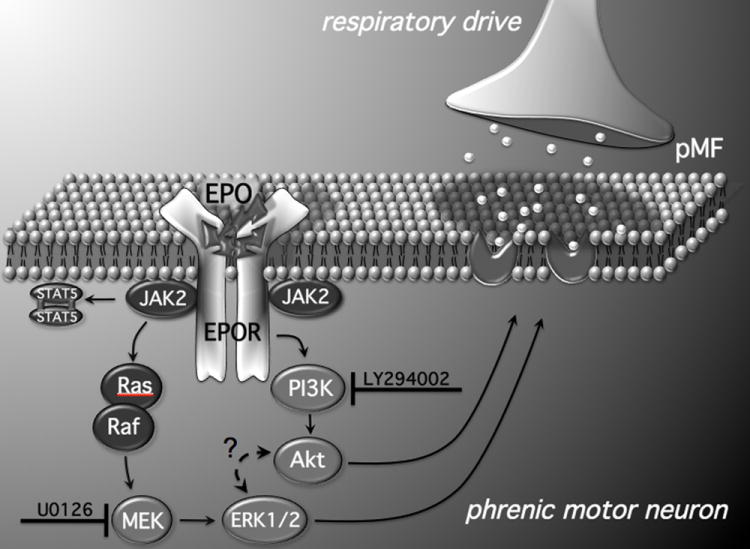

EPO, originally described as a hematopoietic factor (Bert, 1882; Bert, 1878; Jourdanet, 1875), was recently discovered in the CNS (Masuda et al., 1994; Digicaylioglu et al., 1995; Marti et al., 1996; Morishita et al., 1997; Bernaudin et al., 1999; Brines et al., 2000) where it exerts neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects on neurons, including motor neurons (Celik et al., 2002; Iwasaki et al., 2002; Mennini et al., 2006; Koh et al., 2007; Naganska et al., 2010). EPO plays an important role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Weber et al., 2002; Adamcio et al., 2008), and modulates breathing via peripheral and central neural mechanisms (Soliz et al., 2005; 2007). Here we demonstrate that EPO is involved in spinal respiratory motor plasticity. Specifically, cervical spinal EPO receptor activation elicits long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. In association, EPO-R activation increases phosphorylated ERK and Akt expression within identified phrenic motor neurons. EPO-R-induced pMF appears to require both MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt activity, consistent with reported EPO signaling cascades (Bao et al., 1999; Govert et al., 1995). EPO-induced pMF and increased phospho-ERK expression are both blocked by MEK and PI3 kinase inhibition. In addition, MEK and the PI3 kinase inhibition also blocked EPO-induced Akt phosphorylation within phrenic motor neurons. Although immunohistochemistry reveals that both EPO and its primary receptor are located on phrenic motor neurons, suggesting possible autocrine actions the possibility of paracrine actions should also be considered. Our working model of EPO-induced pMF is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Working model of EPO-induced pMF. EPO binds EPO-R, either in an autocrine or paracrine fashion, initiating the JAK2/STAT5, MEK/ERK and PI3 Kinase/Akt pathways. Both the MEK/ERK and PI3 Kinase/Akt pathways are required for EPO-induced pMF since the MEK inhibitor (U0126) and the PI3 Kinase inhibitor (LY294002) abolish EPO-induced pMF. However, since pre-treatment with LY294002 inhibits pERK expression in phrenic motor neurons, there may be complex interactions between these pathways that are unique to the EPO signaling cascade (Schmidt et al., 2004). Although mechanisms downstream from ERK and Akt are unknown, EPO may increase glutamate receptor insertion on the post-synaptic membrane between pre-motor and phrenic motor neurons, thereby amplifying synaptic inputs and eliciting pMF.

Since EPO expression is increased during hypoxia via HIF-1α or HIF-2α dependent transcriptional regulation (Wang et al., 1995; Wang and Semenza, 1993; Yeo et al., 2008), EPO may be involved in well-known models of respiratory motor plasticity elicited by prolonged or repetitive hypoxia (Powell et al., 1998; Mitchell and Johnson, 2003; Mahamed and Mitchell, 2007).

ERK and EPO-induced pMF

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) are involved in hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Impey et al., 1999; Valjent et al., 2001; Sweatt, 2004), long-term spatial memory formation (Brambilla et al., 1997; Kornhauser and Greenberg, 1997; Blum et al., 1999; Selcher et al., 1999), facilitation of the Aplysia gill withdrawal reflex (Martin et al., 1997), and respiratory motor plasticity.

Multiple cellular cascades lead to pMF, and frequently converge on ERK and/or Akt signaling (Dale-Nagle et al., 2010a). One well-known form of pMF is phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF) following acute intermittent hypoxia (Mitchell et al., 2001). New BDNF synthesis is necessary and sufficient for pLTF, followed by activation of the high-affinity BDNF receptor, TrkB (Baker-Herman et al., 2004). TrkB subsequently increases ERK phosphorylation near the phrenic motor nucleus (Wilkerson and Mitchell, 2009), and MEK/ERK signaling is necessary for pLTF (Hoffman and Mitchell, unpublished). VEGF induced pMF is also MEK/ERK-dependent, at least in part (Dale-Nagle et al., 2011). Collectively, available data indicate an important role for ERK in spinal respiratory motor plasticity, including EPO-induced pMF.

Akt and EPO-induced pMF

The PI3 Kinase/Akt pathway is also involved in synaptic plasticity (Franke et al., 1997), including chemotaxis learning in C. elegans (Tomioka et al., 2006), hippocampal LTP (Opazo et al., 2003) and fear conditioning in rat prefrontal cortex (Sui et al., 2008). Here we show that the PI3K/Akt pathway is crucial for EPO-induced pMF.

Akt phosphorylation and/or activation is important in some forms of pMF which involve Gs protein coupled metabotropic receptors (Dale-Nagle et al., 2010a). Increased Akt phosphorylation is associated with pMF induced by spinal activation of adenosine 2a or serotonin type 7 receptors, a novel pathway eliciting TrkB trans-activation without new BDNF synthesis (Golder et al., 2008; Hoffman and Mitchell, 2011). Though the requirement for PI3K/Akt signaling has not been tested for A2a receptor induced pMF, it is necessary for 5HT7 receptor induced pMF (Hoffman and Mitchell, 2011). Spinal VEGF receptor activation also elicits pMF via an Akt-dependent mechanism (Dale-Nagle et al., 2011). Thus, Akt signaling is critical for multiple forms of spinal respiratory motor plasticity, including EPO-induced pMF.

ERK/Akt interactions

Our interpretations concerning the respective roles of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling in EPO-induced pMF were complicated by effects of LY294002 on phospho-ERK levels in phrenic motor neurons, as well as effects of UO126 on phospho-Akt levels (Figure 3B). Although one possibility is that the drugs have non-specific effects, a detailed study of direct LY294002 interactions with various proteins (including PI3K family members) revealed no interactions between LY294002 and MEK or ERK MAP kinases (Gharbi et al., 2007). On the other hand, some indirect MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt interactions have been reported (Kodiha et al., 2009; Ballif and Blenis, 2001; Hayashi et al., 2008). Of particular note, EPO-R signaling is more complex than previously thought; Schmidt and colleagues report that PI3K activity is necessary for EPO-induced MEK/ERK activation depending on the EPO concentration and interactions with other growth factors (Schmidt et al., 2004). Thus, we cannot be sure if Akt is directly or indirectly necessary for EPO-induced pMF because it is required to activate ERK. Regardless, our fundamental conclusions remain sound: both ERK and Akt activation are necessary for full expression of EPO-induced pMF.

EPO induced frequency facilitation

In anesthetized, paralyzed, vagotomized and ventilated rats, pMF is most prominent in phrenic burst amplitude, with small, inconsistent effects on respiratory burst frequency (Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2008). In the present study, we performed a limited cervical EPO dose/response curve, enabling us to prevent drug spread to the brain and to localize drug effects to spinal segments associated with the phrenic motor nucleus. As a marker for brain effects, we monitored XII nerve activity, which did not show significant changes in burst amplitude after 10IU EPO injections. However, this same intrathecal dose elicited a small increase in burst frequency that began 60-min post-injection. This frequency facilitation could be due to undetected spread of EPO to brainstem regions; however, larger EPO doses (20IU and 30IU, which should have increased rostral spread) did not elicit similar frequency responses. Thus, we suspect that the frequency facilitation at 10IU arose from: 1) spinal EPO-R activation in ascending sensory pathways that converge on brainstem rhythm generating neurons; and/or 2) a spontaneous, low baseline frequency before EPO administration in the 10IU group (not 20 or 30IU groups; data not shown). Although there is no explanation for this relatively low baseline frequency in the 10IU EPO group, frequency facilitation following acute intermittent hypoxia is negatively correlated with baseline frequency (Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2008). Thus, we consider the frequency facilitation observed here to be a spurious result. Because of the small and inconsistent nature of this frequency facilitation, we did not explore it further.

Possible Significance

We do not suspect that EPO plays a role in pLTF following acute intermittent hypoxia, a distinct form of pMF that requires new BDNF synthesis via translation of existing mRNA (Baker-Herman et al., 2004). The time-domain of pLTF is too short for transcriptional regulation of EPO (< 1 hr).

After exposure to intermittent hypoxia for days (or longer), pLTF is enhanced, demonstrating a form of respiratory metaplasticity (Ling et al., 2001; Wilkerson and Mitchell, 2009). EPO has considerable potential to play a role in respiratory metaplasticity following repetitive or prolonged exposures to intermittent (or sustained) hypoxia, such as ventilatory acclimatization to chronic hypoxia (Powell et al., 1998). As yet, these ideas remain untested.

Possible therapeutic implications

We recently attempted to harness respiratory plasticity induced by repetitive acute intermittent hypoxia as a therapeutic approach in cases of ventilatory compromise (Mitchell, 2007), such as following cervical spinal cord injury (Dale-Nagle et al., 2010b; Vinit and Kastner, 2009; Vinit et al., 2009; Trumbower et al., 2011) or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Nichols and colleagues, unpublished).

EPO expression is upregulated after spinal injury, and can prevent apoptosis from anoxia, excitotoxicity and glucose deprivation (Brines and Cerami, 2006). However, due to the longer time frames for CNS EPO production, endogenous upregulation of this molecule is unlikely to play any major role in acute phases of injury. Consequently, recent studies have used exogenous EPO application to promote neuroprotection and functional recovery following spinal injury (Arishima et al., 2006; Boran et al., 2005; Cetin et al., 2006; Fumagalli et al., 2008; Gorio et al., 2002; Grasso et al., 2006; Kaptanoglu et al., 2004; Okutan et al., 2007; Vitellaro-Zuccarello et al., 2007; 2008; Zhang et al., 2010). An unintended outcome of this EPO administration may well have been increased breathing, which can be good or bad depending on the prevailing state of the patient. If breathing is inadequate due to cervical injury, then EPO induced pMF is expected to restore lost breathing function.

EPO has also been investigated for its potential as an ALS treatment, including studies on spinal cultures (Naganska et al., 2010), SOD1G93A mice (Koh et al., 2007; Grignaschi et al., 2007) and human patients (Lauria et al., 2009; Maurer et al., 2008). Early results suggest a degree of neuroprotection, though benefits have been limited and such treatments are unlikely to “cure” the disease.

We suggest an unrecognized benefit of EPO treatments may be improved respiratory (and somatic) motor function due to mechanisms of induced motor plasticity. These effects could be of crucial importance since ventilatory complications are the leading cause of death after spinal injury or in ALS patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NS057778. We thank Dr. S. Mahamed for his custom software which aided the analysis of neurophysiological recordings.

References

- Adamcio B, Sargin D, Stradomska A, Medrihan L, Gertler C, Theis F, Zhang M, Müller M, Hassouna I, Hannke K, Sperling S, Radyushkin K, El-Kordi A, Schulze L, Ronnenberg A, Wolf F, Brose N, Rhee JS, Zhang W, Ehrenreich H. Erythropoietin enhances hippocampal long-term potentiation and memory. BMC Biol. 2008;6:37. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arishima Y, Setoguchi T, Yamaura I, Yone K, Komiya S. Preventive effect of erythropoietin on spinal cord cell apoptosis following acute traumatic injury in rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(21):2432–8. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000239124.41410.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach KB, Mitchell GS. Hypoxia-induced long-term facilitation of respiratory activity is serotonin dependent. Respir Physiol. 1996;104:251–260. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires spinal serotonin receptor activation and protein synthesis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6239–6246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06239.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Determinants of frequency long-term facilitation following acute intermittent hypoxia in vagotomized rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;162:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Fuller DD, Bavis RW, Zabka AG, Golder FJ, Doperalski NJ, Johnson RA, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:48–55. doi: 10.1038/nn1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballif BA, Blenis J. Molecular Mechanisms Mediating Mammalian Mitogen activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Kinase (MEK)-MAPK Cell Survival Signals. Cell Growth and Diff. 2001;12(3):97–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao H, Jacobs_Helber SM, Lawson AE, Penta K, Wickrema A, Sawyer ST. Protein kinase B (c-Akt), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and STAT5 are activated by erythropoietin (EPO) in HCD57 erythroid cells but are constitutively active in an EPO-independent, apoptosis-resistant subclone (HCD57-SREI cells) Blood. 1999;93(11):3757–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaudin M, Marti HH, Roussel S, Divoux D, Nouvelot A, MacKenzie ET, Petit E. A potential role for erythropoietin in focal permanent cerebral ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:643–51. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199906000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert P. La Pression Barométrique: Recherches de Physiologie Expérimentale. Paris: Masson; 1878. [Google Scholar]

- Bert P. Sur la richesse en hemoglobine du sang des animaux vivant sur les hauts lieux. CR Acad Sci Paris. 1882;94:805–807. [Google Scholar]

- Blum S, Moore AN, Adams F, Dash PK. A mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in the CA1/CA2 subfield of the dorsal hippocampus is essential for long-term spatial memory. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3535–3544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03535.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchiaro CM, Feldman JL. Synaptic activity-independent persistent plasticity in endogenously active mammalian motoneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4292–4295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305712101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boran BO, Colak A, Kutlay M. Erythropoietin enhances neurological recovery after expreimental spinal cord injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2005;23(5-6):341–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulenguez P, Gestreau C, Vinit S, Stamegna JC, Kastner A, Gauthier P. Specific and artefactual labeling in the rat spinal cord and medulla after injection of monosynaptic retrograde tracers into the diaphragm. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:206–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla R, Gnesutta N, Minichiello L, Whit G, Roylance AJ, Herron CE, Ramsey M, Wolfer DP, Cestari V, Rossi-Arnaud C, Grant SG, Chapman PF, Lipp HP, Sturani E, Klein R. A role for the Ras signalling pathway in synaptic transmission and long-term memory. Nature. 1997;390(6657):281–6. doi: 10.1038/36849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines ML, Ghezzi P, Keenan S, Agnello D, de Lanoerolle NC, Cerami C, Itri LM, Cerami A. Erythropoietin crosses the bloodbrain barrier to protect against experimental brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10526–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Cerami A. Discovering erythropoietin’s extra-hematopoietic functions: biology and clinical promise. Kidney Int. 2006;70(2):246–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik M, Gökmen N, Erbayraktar S, Akhisaroglu M, Konakc S, Ulukus C, Genc S, Genc K, Sagiroglu E, Cerami A, Brines M. Erythropoietin prevents motor neuron apoptosis and neurologic disability in experimental spinal cord ischemic injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(4):2258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042693799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetin A, Nas K, Bükükbayram H, Ceviz A, Olmez G. The effects of systemically administered methylprednisolone and recombinant human erythropoietin after acute spinal cord compressive injury in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;34(11):1181–5. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly DT, Heuvelman DM, Nelson R, Olander JV, Eppley BL, Delfino JJ, Siegel NR, Leimgruber RM, Feder J. Tumor vascular permeability factor stimulates endothelial cell growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1470–1478. doi: 10.1172/JCI114322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale-Nagle EA, Satriotomo I, Mitchell GS. Spinal vascular endothelial growth factor elicits phrenic motor facilitation via ERK and Akt signaling. J Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0239-11.2011. IN PRESS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale-Nagle EA, Hoffman MS, Macfarlane PM, Mitchell GS. Multiple pathways to long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;669:225–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5692-7_45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale-Nagle EA, Hoffman MS, MacFarlane PM, Satriotomo I, Lovett-Barr MR, Vinit S, Mitchell GS. Spinal plasticity following intermittent hypoxia: implications for spinal injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010b;1198:252–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen JE, Mui ALF, Puil L, Pawson T, Krystal G. Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase associates, via its Src homology 2 domains, with the activated erythropoietin receptor. Blood. 1993;81:3204–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digicaylioglu M, Bichet S, Marti HH, Wenger RH, Rivas LA, Bauer C, Gassmann M. Localization of specific erythropoietin binding sites in defined areas of the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3717–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza GL. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(9):4604–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel HL, Coll JR, Charlifue SW, Whiteneck GG, Gardner BP, Jamous MA, Krishnan KR, Nuseibeh I, Savic G, Sett P. Long-term survival in spinal cord injury: a fifty year investigation. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:266–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Bach KB, Baker TL, Kinkead R, Mitchell GS. Long term facilitation of phrenic motor output. Respir Physiol. 2000;121(2-3):135–46. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, Madaschi L, Brenna P, Caffino L, Marfia G, Di Giulio AM, Racagni G, Gorio A. Single exposure to eythropoietin modulates Nerve Growth Factor expression in the spinal cord following traumatic injury: comparison with methylprednisolone. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;578(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann M, Tissot van Patot M, Soliz J. The neuronal control of hypoxic ventilation: erythropoietin and sexual dimorphism. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1177:151–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann M, Soliz J. Erythropoietin modulates the neural control of hypoxic ventilation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(22):3575–82. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi SI, Zvelebil MJ, Shuttleworth SJ, Hancox T, Saghir N, Timms JF, Waterfield MD. Exploring the specificity of the PI3K family inhibitor LY294002. Biochem J. 2007;404:15–21. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert S, Duprez V, Lacombe C, Gisselbrecht S, Mayeux P. The signal transduction pathway of erythropoietin involves three forms of mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinases in UT7 erythroleukemia cells. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.075_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ. Receptor tyrosine kinases and respiratory motor plasticity. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Ranganathan L, Satriotomo I, Hoffman M, Lovett-Barr MR, Watters JJ, Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Spinal adenosine A2a receptor activation elicits long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2033–2042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3570-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorio A, Gokmen N, Erbayraktar S, Yimaz O, Madaschi L, Cichetti C, Di Giulio AM, Vardar E, Cerami A, Brines M. Recombinant human erythropoietin counteracts secondary injury and markedly enhances neurological recovery from experimental spinal cord trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(14):9450–5. [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG, Rafols JA. The phrenic nucleus of the albino rat: a correlative HRP and Golgi study. J Comp Neurol. 1981;201(3):441–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.902010309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso G, Sfacteria A, Erbayraktar S, Passalacqua M, Meli F, Gokemen N, Yilmaz O, La Torre D, Buemi M, Iacopino DG, Coleman T, Cerami A, Brines M, Tomasello F. Amelioration of spinal cord compressive injury by pharmacological preconditioning with erythropoietin and a nonerythropoietic erythropoietin derivative. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4(4):310–8. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.4.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grignaschi G, Zennaro E, Tortarolo M, Calvaresi N, Bendotti C. Erythropoietin does not preserve motor neurons in a mouse model of familial ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8(1):31–5. doi: 10.1080/17482960600783456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Tsuchiya Y, Nakayama K, Satoh T, Nishida E. Down regulation of the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway by ERK MAP kinase in growth factor signaling. Genes to Cells. 2008;13(9):941–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He TC, Zhuang H, Jiang N, Waterfield MD, Wojchowski DM. Association of the p85 regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with an essential erythropoietin receptor subdomain. Blood. 1993;82:3530–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MS, Mitchell GS. Spinal 5-HT Receptor Activation Induces Long-Lasting Phrenic Motor Facilitation. J Physiol. 2011 Jan 17; doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201657. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impey S, Obrietan K, Storm DR. Making new connections: role of ERK/MAP kinase signaling in neuronal plasticity. Neuron. 1999;23(1):11–4. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y, Ikeda K, Ichikawa Y, Igarashi O, Iwamoto K, Kinoshita M. Protective effect of interleukin-3 and erythropoietin on motor neuron death after neonatal axotomy. Neurol Res. 2002;24(7):643–6. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdanet D. Influence de la Pression de L’air sur la Vie de L’homme. Paris: Masson; 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Juul SE. Nonerythropoietic roles of erythropoietin in the fetus and neonate. Clin Perinatol. 2000;27(3):527–41. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(05)70037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T, Sato S, Iwai K, Czyzyk-Krzeska M, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Activation of HIF-1α ubiquitination by a reconstituted von Hippel-Lindau VHL tumor suppressor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:104030–10435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190332597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptanoglu E, Solaroglu I, Okutan O, Surcu HS, Akbiyki F, Beskonakli E. Erythropoietin exerts neuroprotection after acute spinal cord injury in rats: effect on lipid peroxidation and early ultrastructural findings. Neurosurg Rev. 2004;27(2):113–20. doi: 10.1007/s10143-003-0300-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic E, Kilic U, Soliz J, Bassetti CL, Gassmann M, Hermann DM. Brain derived erythropoietin protects from focal cerebral ischemia by dual activation of ERK-1/-2 and Akt pathways. FASEB J. 2005;19(14):2026–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3941fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodiha M, Banski P, Stochaj U. Interplay between MEK and PI3 kinase signaling regulates the subcellular localization of protein kinases ERK1/2 and Akt upon oxidative stress. FEBS Letters. 2009;583:1987–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SH, Kim Y, Kim HY, Cho GW, Kim KS, Kim SH. Recombinant human erythropoietin suppresses symptom onset and progression of G93A-SOD1 mouse model of ALS by preventing motor neuron death and inflammation. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(7):1923–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhauser JM, Greenberg ME. A kinase to remember: dual roles for MAP kinase in long-term memory. Neuron. 1997;18:839–842. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, White TE, Coutts MA, Jones AL, Sandhu MS, Bloom DC, Bolser DC, Yates BJ, Fuller DD, Reier PJ. Cervical prephrenic interneurons in the normal and lesioned spinal cord of the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511(5):692–709. doi: 10.1002/cne.21864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Campanella A, Filippini G, Martini A, Penza P, Maggi L, Antozzi C, Ciano C, Beretta P, Caldiroli D, Ghelma F, Ferrara G, Ghezzi P, Mantegazza R. Erythropoietin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a pilot, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and tolerability. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(5-6):410–5. doi: 10.3109/17482960902995246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L, Fuller DD, Bach KB, Kinkead R, Olson EB, Jr, Mitchell GS. Chronic intermittent hypoxia elicits serotonin-dependent plasticity in the central neural control of breathing. J Neurosci. 2001;21(14):5381–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05381.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cox SR, Morita T, Kourembanas S. Hypoxia regulates vascular endothelial factor gene expression in endothelial cells. Indentification of a 5’ enhancer. Circ Res. 1995;77(3):638–43. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamed S, Mitchell GS. Is there a link between intermittent hypoxia induced respiratory plasticity and obstructive sleep apnoea? Exp Physiol. 2007;92:27–37. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.033720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon PC, Hirota K, Semenza GL. FIH-1: a novel protein that interacts with HIF-1α and VHL to mediate repression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2675–2686. doi: 10.1101/gad.924501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. Retrograde labeling of phrenic motoneurons by intrapleural injection. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;182:244–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S, Okano M, Yamagishi K, Nagao M, Ueda M, Sasaki R. A novel site oferythropoietin production. Oxygen-dependent production in cultured rat astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(30):19488–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti HH, Wenger RH, Rivas LA, Straumann U, Digicaylioglu M, Henn V, Yonekawa Y, Bauer C, Gassmann M. Erythropoietin gene expression in human, monkey and murine brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:666–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KC, Michael D, Rose JC, Barad M, Casadio A, Zhu H, Kandel ER. MAP kinase translocates into the nucleus of the presynaptic cell and is required for long-term facilitation in Aplysia. Neuron. 1997;18:899–912. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer MH, Schäbitz WR, Schneider A. Old friends in new constellations—the hematopoietic growth factors G-CSF, GM-CSF and EPO for the treatment of neurological diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(14):1407–11. doi: 10.2174/092986708784567671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399(6733):271–5. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux P, Dusanter-Fourt I, Muller O, Mauduit P, Sabbah M, Druker B, Vainchenker W, Fischer S, Lacombe C, Gisselbrecht S. Erythropoietin induces the association of phosphatidylinositol 3’ kinase with a tyrosine phosphorylated complex containing the erythropoietin receptor. Eur J Biochem. 1993;216:821–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Zhang Y, White DP, Ling L. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires NMDA receptors in the phrenic motonucleus in rats. J Physiol. 2005;567:599–611. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Liu C, Cao Y, Ling L. Formation and maintenance of ventilatory long-term facilitation require NMDA but not non-NMDA receptors in awake rats. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:942–950. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01274.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennini T, De Paola M, Bigini P, Mastrotto C, Fumagalli E, Barbera S, Mengozzi M, Viviani B, Corsini E, Marinovich M, Torup L, Van Beek J, Leist M, Brines M, Cerami A, Ghezzi P. Nonhematopoietic erythropoietin derivatives prevent motoneuron degeneration in vitro and in vivo. Mol Med. 2006;7-8:153–60. doi: 10.2119/2006-00045.Mennini. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS. Respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia: a guide for novel therapeutic approaches to ventilatory control disorders. In: Gaultier C, editor. Genetic Basis for Respiratory Control Disorders. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS, Johnson SM. Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:358–374. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00523.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS, Baker TL, Nanda SA, Fuller DD, Zabka AG, Hodgeman BA, Bavis RW, Mack KJ, Olson EB., Jr Invited review: Intermittent hypoxia and respiratory plasticity. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2466–2475. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura Y, Muira O, Ihle JN, Aoki N. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by the erythropoietin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994a;269:29962–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura O, Nakamura N, Ihle JN, Aoki N. Erythropoietin-dependent Association of Phosphatidylinositol 3- Kinase with Tyrosine phosphorylated Erythropoietin Receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994b;269:614–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita E, Masuda S, Nagao M, Yasuda Y, Sasaki R. Erythropoietin receptor is expressed in rat hippocampal and cerebral cortical neurons, and erythropoietin prevents in vitro glutamate-induced neuronal death. Neuroscience. 1997;76:105–16. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagańska E, Taraszewska A, Matyja E, Grieb P, Rafałowska J. Neuroprotective effect of erythropoietin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) model in vitro. Ultrastructural study. Folia Neuropathol. 2010;48(1):35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okutan O, Solaroglu I, Beskonakli E, Taskin Y. Recombinant human erythropoietin decreases myeloperoxidase and caspase-3 activity and improves early functional results after spinal cord injury in rats. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(4):364–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo P, Watabe AM, Grant SG, O’Dell TJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates the induction of long-term potentiation through extracellular signal-related kinase-independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3679–3688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03679.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell FL, Milsom WK, Mitchell GS. Time domains of the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol. 1998;112:123–34. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(98)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt LF. Neurotrophin-regulated signaling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1473):1545–64. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinfeld H, Seger R. The ERK cascade: a prototype of MAPK signaling. Mol Biotechnol. 2005;31(2):151–74. doi: 10.1385/MB:31:2:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinfeld H, Seger R. The ERK cascade as a prototype of MAPK signaling pathways. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;250:1–28. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-671-1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salceda S, Caro J. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) protein is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system under normoxic conditions. Its stabilization by hypoxia depends on redox-induced changes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22642–22647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EK, Fichelson S, Feller SM. PI3 kinase is important for Ras, MEK and ERK activation of Epo-stimulated human erythroid progenitors. BMC Biology. 2004;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcher JC, Atkins CM, Trzaskos JM, Paylor R, Sweatt JD. A necessity for MAP kinase activation in mammalian spatial learning. Learn Mem. 1999;6:478–490. doi: 10.1101/lm.6.5.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL, Nejfelt MK, Chi SM, Antonarakis SE. Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3’ to the human erythropoietin gene. Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(13):5680–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger DR, Perruzzi CA, Feder J, Dvorak HF. A highly conserved vascular permeability factor secreted by a variety of human and rodent tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5629–5632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Wu Y, Xu JY, Zhang J, Sinclair SH, Yanoff M, Xu G, Li W, Xu GT. ERK-and Akt-dependent neuroprotection by erythropoietin (EPO) against glyoxal-AGEs via modulation of Bcl-xL, Bax, and BAD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(1):35–46. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirén AL, Knerlich F, Poser W, Gleiter CH, Brück W, Ehrenreich H. Erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in human ischemic/hypoxic brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101(3):271–6. doi: 10.1007/s004010000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliz J, Joseph V, Soulage C, Becskei C, Vogel J, Pequignot JM, Ogunshola O, Gassmann M. Erythropoietin regulates hypoxic ventilation in mice by interacting with brainstem and carotid bodies. J Physiol. 2005;568:559–571. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliz J, Soulage C, Hermann DM, Gassmann M. Acute and chronic exposure to hypoxia alters ventilatory pattern but not minute ventilation of mice overexpressing erythropoietin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007a;293(4):R1702–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00350.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliz J, Gassmann M, Joseph V. Downregulation of soluble erythropoietin receptor in the mouse brain is required for the ventilatory acclimatization to hypoxia. J Physiol. 2007b;583:329–336. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spedding M, Gressens P. Neurotrophins and cytokines in neuronal plasticity. Novartis Found Symp. 2008;289:222–233. doi: 10.1002/9780470751251.ch18. discussion 233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkebaum E, Lambrechts D, Carmeliet P. VEGF: once regarded as a specific angiogenic factor, now implicated in neuroprotection. Bioessays. 2004;26(9):943–54. doi: 10.1002/bies.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui L, Wang J, Li BM. Role of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of the rapamycin signaling pathway in long-term potentiation and trace fear conditioning memory in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Learn Mem. 2008;15:762–776. doi: 10.1101/lm.1067808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt D. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomioka M, Adachi T, Suzuki H, Kunitomo H, Schafer WR, Iino Y. The insulin/PI 3-kinase pathway regulates salt chemotaxis learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron. 2006;51:613–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Caboche J, Vanhoutte P. Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase induced gene regulation in brain: a molecular substrate for learning and memory? Mol Neurobiol. 2001;23(2-2):83–89. doi: 10.1385/MN:23:2-3:083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinit S, Kastner A. Descending bulbospinal pathways and recovery of respiratory motor function following spinal cord injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;169(2):115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinit S, Lovett-Barr MR, Mitchell GS. Intermittent hypoxia induces functional recovery following cervical spinal injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;169(2):210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitellaro-Zuccarello L, Mazzetti S, Madaschi L, Bosisio P, Fontana E, Gorio A, De Biasi S. Chronic erythropoietin-mediated effects on the expression of astrocyte markers in a rat model of contusive spinal cord injury. Neuroscience. 2008;151(2):452–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitellaro-Zuccarello L, Mazzetti S, Madaschi L, Bosisio P, Gorio A, De Biasi S. Erythropoietin-mediated preservation of the white matter in rat spinal cord injury. Neuroscience. 2007;144(3):865–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxia inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(3):1230–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Jiang B-H, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;88:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Maier RF, Hoffmann U, Grips M, Hoppenz M, Aktas AG, Heinemann U, Obladen M, Schuchmann S. Erythropoietin improves synaptic transmission during and following ischemia in rat hippocampal slice cultures. Brain Res. 2002;958(2):305–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson JE, Mitchell GS. Daily intermittent hypoxia augments spinal BDNF levels, ERK phosphorylation and respiratory long-term facilitation. Exp Neurol. 2009;217:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Meng Y, Zhang Y, Qu C, Schallert T, Chopp M. Delayed administration of erythropoietin reducing hippocampal cell loss, enhancing angiogenesis and neurogenesis, and improving functional outcome following traumatic brain injury in rats: comparison of treatment with single and triple dose. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(3):598–608. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.JNS09844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo E-J, Cho Y-S, Kim M-S, Park J-W. Contribution of HIF-1α or HIF 2α to erythropoietin expression: in vivo evidence based on chromatin immunoprecipitation. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:11–17. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Nanduri J, Bhasker CR, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase-dependent activation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 transcriptional activity in cells subjected to intermittent hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4321–4328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Nanduri J, Khan S, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Induction of HIF-1α expression by intermittent hypoxia: involvement of NADPH oxidase, CA2+ signaling, prolyl hydroxylases and mTOR. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:674–685. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Signore AP, Zhou Z, Wang S, Cao G, Chen J. Erythropoietin protects CA1 neurons against global cerebral ischemia in rat: potential signaling mechanisms. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83(7):1241–51. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Meng Y, Liu Z, Qu C, Chopp M. Sprouting of corticospinal tract axons from the contralateral hemisphereinto the denervated side of the spinal cord is associated with functional recovery in adult rat after traumatic brain injury and erythropoietin treatment. Brain Res. 2010;1353:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]