Abstract

BACKGROUND

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the third most common genitourinary cancer and the most common primary renal neoplasm. Estimates of the economic burden of RCC in the United States range from approximately $400 million (in year 2000 dollars) to $4.4 billion (in year 2005 dollars). Actual costs associated with RCC, particularly for elderly Medicare patients who account for 46% of U.S. patients hospitalized for RCC, are poorly understood.

OBJECTIVE

To estimate all-cause health care costs associated with RCC using the combined Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database.

METHODS

The sample was limited to non-HMO patients aged 65 years or older who were diagnosed with a first primary RCC (SEER site recode 59, kidney and renal pelvis) between 1995 and 2002. Our final sample included 4,938 patients with RCC and 9,876 non-HMO noncancer comparison group cases without chronic renal disease drawn from the SEER 5% Medicare sample and matched by a propensity score calculated from age, gender, race/ethnicity, and comorbidities. Costs were defined as payments made by Medicare for all-cause medical treatments including inpatient stays, emergency room visits, outpatient procedures, office visits, home health visits, durable medical equipment, and hospice care, but excluding out-patient prescription drugs. Using the method of Bang and Tsiatis (2000), we estimated cumulative costs at 1 and 5 years by estimating average costs for each patient in each month up to 60 months following diagnosis. Total costs were weighted sums of monthly costs, where weights were the inverse probability that the patient was not censored, and inverse probabilities were estimated by Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to censoring. Using the method of Lin (2000), we performed multivariate analyses of costs by fitting each of the 60 monthly costs to linear models that controlled for demographic characteristics and comorbidities. Marginal effects of covariates on 1- and 5-year costs were obtained by summing the coefficients for months 1 through 12 and months 1 through 60, respectively. Confidence intervals were obtained by bootstrapping.

RESULTS

Patients with RCC and matched comparison group cases had similar demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and chronic conditions. At the start of the fifth year post-diagnosis, there were 1,208 Medicare RCC cases of the original 4,938 (20.8%). Mean costs per patient per month (PPPM) in the first year were $3,673 for patients with RCC and $793 for comparison group patients. PPPM costs were higher for RCC patients with more advanced stage (i.e., regional or distant) disease. Average cumulative total costs for RCC patients were $33,605 per patient in the first year following diagnosis and $59,397 per patient in the first 5 years following diagnosis. Several patient-specific factors were associated with 1- and 5-year costs in multivariate analyses, including age, race/ethnicity, and comorbidities. Among RCC patients, treatment with surgery and radiation was associated with higher costs per patient than treatment with surgery alone at 1 year ($24,556, 95% CI = $16,673–$32,940) and 5 years ($30,540, 95% CI = $17,853–$43,648). RCC patients who received chemotherapy as part of their treatment regimen also had significantly higher costs per patient than those who received surgery alone at 1 year ($15,144, 95% CI = $9,979–$20,344) and 5 years ($13,440, 95% CI = $1,257–$27,572).

CONCLUSIONS

Newly diagnosed RCC is associated with a significant economic burden, which is largely determined by several patient characteristics, disease stage, and treatment choice.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the third most common genitourinary cancer and the most common primary renal neoplasm.1 While survival rates at 5 years are 90.8% and 63.3% for tumors confined to the kidney (i.e., local disease) and spread to regional structures (i.e., regional disease), respectively, the 5-year survival rate is a dismal 11.1% for metastatic disease (i.e., distant disease, mRCC).2–4 Approximately 58,240 new cases of RCC were diagnosed in 2010, or approximately 18.8 per 100,000 population.5 The overall incidence of RCC continues to rise secondary to an increased diagnosis of incidental small renal masses identified during abdominal axial imaging.6–8 Approximately 18% of patients diagnosed with RCC have mRCC.9 The median survival for mRCC is less than 1 year.4 However, the 5-year survival rate for invasive cancer of the kidney and renal pelvis in the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database for the period from 2001 to 2007 was 70%, suggesting that a 5-year cost analysis is potentially informative for RCC.4

Although RCC carries a significant economic burden on patients and the health care system, the literature on associated costs of RCC is somewhat limited. Estimates of the economic burden of RCC in the United States range from approximately $400 million (in year 2000 dollars) to $4.4 billion (in year 2005 dollars).9 There are many reasons for the wide range of reported costs, including heterogeneity of data sources, stages of disease, and methodological approaches for cost computations. Other contemporary cost studies involving RCC have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic imaging modalities in the pre-operative period,10–13 as well as the cost-effectiveness of immunotherapy regimens and targeted molecular therapies for advanced-stage RCC.9,14

The disparity in reports of the economic burden of RCC coupled with the limited number of pharmacoeconomic studies for the treatment of RCC emphasize the need to better understand costs associated with this malignancy. This is particularly true for elderly patients covered by Medicare, who account for 46% of U.S. patients hospitalized for RCC.15 We attempt to quantify RCC-related costs by using data from the combined SEER-Medicare database to estimate the costs (defined as payments made by Medicare) for Medicare patients with RCC and the effect of patient- and disease-specific factors on total costs up to 1 and 5 years following diagnosis.

Methods

Data

Data for this study were obtained from the SEER-Medicare linked database. The SEER-Medicare database combines tumor registry data from the National Cancer Institutes (NCI) SEER program for patients who are covered by Medicare with their Medicare billing records.16 Because the SEER-Medicare linked database includes patient and disease information as well as health care claims, it is possible to use these data to study resource utilization among patients with cancer. The SEER-Medicare database also includes a comparison group sample of patients without cancer that can be used for comparison.17 The comparison group sample was drawn from a 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries residing in SEER areas.

Study Sample

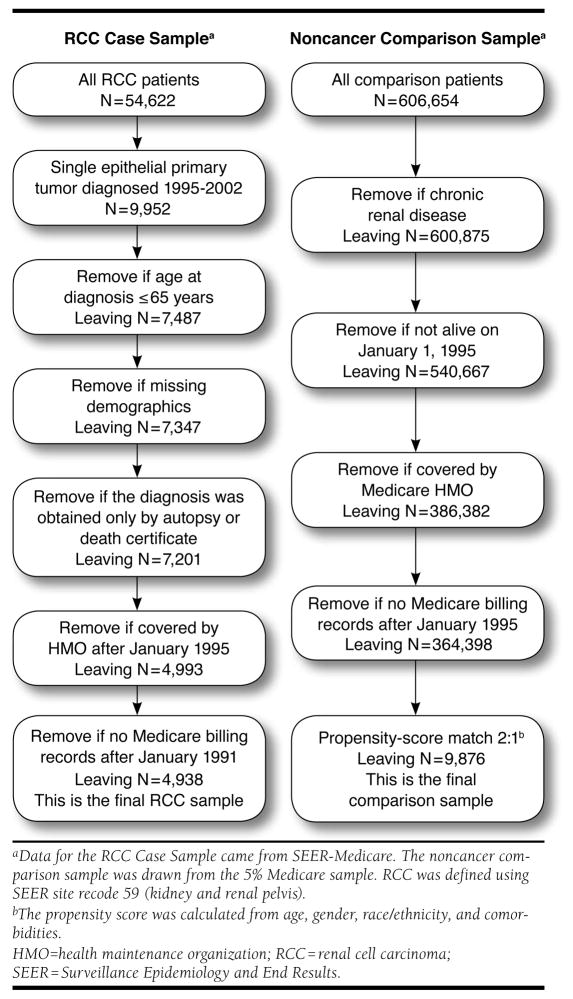

The SEER-Medicare database contains tumor registry data on 54,622 patients who were diagnosed with a first primary RCC tumor between 1973 and 2002 (Figure 1).18 Claims data are available only beginning in 1986 and are only available for certain types of services since 1994. We therefore limited our sample to patients who were diagnosed with a first primary RCC between 1995 and 2002, the final year of tumor registry data availability at the time the present study was initiated. Starting in 1995 rather than 1994 allowed a 1-year look-back window for identifying comorbidities, as described later. We further restricted cases to patients aged 65 years or older and excluded patients with nonepithelial tumors or for whom the diagnosis of cancer was obtained on autopsy or from a death certificate only. In addition, patients enrolled in a health maintenance organization (HMO) at or after the cancer diagnosis were excluded because these patients do not have any Medicare billing records. The earliest HMO exclusions were made for January 1, 1995, because that is the beginning date of the study. We also excluded 140 cases with missing demographic information and 55 cases with no Medicare billing records.

FIGURE 1.

Derivation of RCC and Comparison Group Samples

A comparison group sample of Medicare patients without cancer was selected from the Medicare 5% sample. Noncancer patients were randomly assigned an artificial date of diagnosis from available diagnosis dates of cancer patients. These dates were drawn randomly with replacement and were required to be before the date of death (or the same month). To control for potentially different distributions of patient characteristics, we used a propensity score-matching technique to select a comparison group sample that had a similar distribution of background characteristics.19 We opted for a propensity scorematching approach rather than another matching approach, since we had a relatively large number of characteristics on which to match, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and several specific comorbidities and chronic conditions.

The propensity score was the predicted probability from a logistic regression of case status (n = 4,938) versus comparison group status (n = 364,938). Covariates included year of birth (≤1909, 5-year increments 1910–1934, ≥1935), race/ethnicity (white, black, Asian, Hispanic, other), the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),20,21 and indicators for anemia, hypercalcemia, and hyperlipidemia. We tested several interactions between covariates in the logistic regression model and used the Wald test for overall significance of these interactions (multiple degrees of freedom tests). An interaction between year of birth and race was also included, as it was the only interaction effect that was statistically significant. The model had a c-statistic of 0.63. A greedy matching algorithm was used to match 2 comparison group patients to every RCC patient. All comparison group patients were required to have a propensity score within 0.01 of cases; virtually all matches (99%) were exact. With these criteria, our final sample included 4,938 patients with RCC and 9,876 matched noncancer comparison group cases. A full description of the derivation of the sample and the observations removed at each step is presented in Figure 1.

Costs

The cost analyses take the perspective of Medicare as payer. Costs, therefore, represent actual payments made by Medicare for all-cause treatments including inpatient stays, emergency room visits, outpatient procedures, office visits, home health visits, durable medical equipment, and hospice care, but excluding outpatient prescription drugs. Note that Medicare Part D costs were not included because they were unavailable for the study or follow-up periods. All costs were adjusted for inflation and represent year 2005 dollars. Hospital costs were adjusted using the Hospital and Related Services component of the consumer price index. Outpatient costs, physician payments, hospice, and home care costs were adjusted using the Medical Care Services component of the consumer price index. Medical equipment costs were adjusted using the Medical Care Commodities component of the consumer price index.

Covariates

We studied the impact of demographic and disease characteristics, comorbidities, and treatment choice on 1-year and 5-year costs. Demographic variables included patient age at diagnosis, gender, and race/ethnicity (black, white, Hispanic, other). Disease variables included morphologic extent of malignant disease, defined using the SEER historic stage (local, regional, distant metastasis, unstaged [unknown]),22 and laterality (left, right, and bilateral). A number of comorbidities, including diagnosis-based proxies for known prognostic factors in RCC—anemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypercalcemia—were also included as potential covariates. Specific codes that were used to define these treatments and comorbidities are presented in Table 1. Treatment indicators were mutually exclusive for surgery, radiation, combination of surgery and radiation, as well as absence of any treatment. An indicator was also included for chemotherapy, although this could have been used in combination with any other treatment. Concomitant use of chemotherapy was identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes, ICD-9-CM and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedure codes, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding Systems (HCPCS) codes in billing data.23 We used these codes to identify general chemotherapy administration as well as codes that specifically identified 5-fluourouracil, methotrexate, cylcophosphamide, cisplatin, and carboplatin. These codes were identified by Warren et al. (2002) and are presented in Table 1.23

TABLE 1.

Diagnosis and Procedure Codes Used to Define Comorbidities

| Condition | Codea |

|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | ‘410’ through ‘4109’ ‘412’ |

| Congestive heart failure | ‘428’ through ‘4289’ |

| Peripheral vascular disease | ‘441’ through ‘4419’ ‘4439’ ‘7854’ ‘V434’ |

| ICD-9-CM procedure codes: ‘3813’ ‘3814’ ‘3816’ ‘3818’ ‘3843’ ‘3844’ ‘3846’ ‘3848’ ‘3833’ ‘3834’ ‘3836’ ‘3838’ | |

| ‘3922’ through ‘3926’ ‘3928’ ‘3929’ | |

| CPT codes: ‘35011’ ‘35013’ ‘35045’ ‘35081’ ‘35082’ ‘35091’ ‘35092’ ‘35102’ ‘35103’ ‘35111’ ‘35112’ ‘35121’ ‘35122’ ‘35131’ ‘35132’ ‘35141’ ‘35142’ ‘35151’ ‘35152’ ‘35153’ ‘35311’ ‘35321’ ‘35331’ ‘35341’ ‘35351’ ‘35506’ ‘35507’ ‘35511’ ‘35516’ ‘35518’ ‘35521’ ‘35526’ ‘35531’ ‘35533’ ‘35536’ ‘35541’ ‘35546’ ‘35548’ ‘35549’ ‘35551’ ‘35556’ ‘35558’ ‘35560’ ‘35563’ ‘35565’ ‘35566’ ‘35571’ ‘35582’ ‘35583’ ‘35585’ ‘35587’ ‘35601’ ‘35606’ ‘35612’ ‘35616’ ‘35621’ ‘35623’ ‘35626’ ‘35631’ ‘35636’ ‘35641’ ‘35646’ ‘35650’ ‘35651’ ‘35654’ ‘35656’ ‘35661’ ‘35663’ ‘35665’ ‘35666’ ‘35671’ ‘35694’ ‘35695’ | |

| ‘35355’ through ‘35381’ | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ‘430’ through ‘4379’ ‘438’ |

| ICD-9-CM procedure codes: ‘3812’ ‘3842’ | |

| CPT codes: ‘35301’ ‘35001’ ‘35002’ ‘35005’ ‘35501’ ‘35508’ ‘35509’ ‘35515’ ‘35642’ ‘35645’ ‘35691’ ‘35693’ | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ‘490’ through ‘496’ ‘500’ through ‘505’ ‘5064’ |

| Dementia | ‘290’ through ‘2909’ |

| Paralysis | ‘342’ through ‘3429’ ‘3441’ |

| Diabetes | ‘250’ ‘2507’ ‘2500’ ‘2501’ ‘2502’ ‘2503’ |

| Diabetes with sequelae | ‘2504’ ‘2505’ ‘2506’ ‘2508’ ‘2509’ |

| Chronic renal failure | ‘582’ through ‘5829’ ‘583’ through ‘5839’ ‘588’ through ‘5889’ |

| Various cirrhodites | ‘5712’ ‘5714’ ‘5714x’ ‘5715’ ‘5716’ |

| Moderate-severe liver disease | ‘5722’ through ‘5728’ ‘4560’ ‘4561’ ‘4562’ ‘45620’ ‘45621’ |

| ICD-9-CM procedure codes: ‘391’ ‘4291’ | |

| CPT codes: ‘37140’ ‘37145’ ‘37160’ ‘37180’ ‘37181’ ‘75885’ ‘75887’ ‘43204’ ‘43205’ | |

| Ulcers | ‘5310’ through ‘5313’ ‘5320’ through ‘5323’ ‘5330’ through ‘5333’ |

| ‘5340’ through ‘5343’ ‘531’ ‘5319’ ‘532’ ‘5329’ ‘533’ ‘5339’ | |

| ‘534’ ‘5349’ | |

| ‘5314’ through ‘5317’ ‘5324’ through ‘5327’ ‘5334’ through ‘5337’ | |

| ‘5344’ through ‘5347’ | |

| Rheumatic disease | ‘71481’ ‘725’ ‘7100’ ‘7101’ ‘7104’ ‘7140’ ‘7141’ ‘7142’ |

| AIDS | ‘042’ ‘043’ ‘044’ |

| Chemotherapy | ‘9925’ |

| CPT codes: ‘964xx’ ‘965xx’ | |

| HCPCS codes: ‘Q0083’ ‘Q0085’ | |

| ‘J9190’ ‘J8610’ ‘J9250’ ‘J9260’ ‘J9070’ ‘J9071’ ‘J9072’ ‘J9073’ ‘J9074’ ‘J9075’ ‘J9076’ ‘J9077’ ‘J9078’ ‘J9079’ ‘J9080’ ‘J9082’ ‘J9083’ ‘J9084’ ‘J9085’ ‘J9086’ ‘J9087’ ‘J9088’ ‘J9089’ ‘J9090’ ‘J9091’ ‘J9092’ ‘J9093’ ‘J9094’ ‘J9095’ ‘J9096’ ‘J9097’ ‘J9060’ ‘J9062’ ‘J9045’ |

ICD-9-CM diagnosis code unless otherwise indicated.

AIDS = acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; HCPCS = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

We controlled for comorbidities based on the Deyo adaptation of the CCI.20,21 The CCI is a weighted average of 19 conditions associated with inpatient mortality. We used 18 of these, since all patients in the RCC group had cancer. The CCI has been widely used to study or control for comorbidities among cancer patients and other populations.24–26 All comorbidities were identified from codes during the year prior to diagnosis (RCC cohort) or the assigned pseudo-diagnosis date (comparison cohort). Other comorbidities that are associated with outcomes for RCC but not part of the CCI were identified from ICD-9-CM codes, including anemia (280.9 [iron deficiency anemia unspecified], 281.0 [pernicious anemia], 281.9 [unspecified deficiency anemia], and 282.3 [other hemolytic anemias due to enzyme deficiency]); hypercalcemia (275.42); and hyperlipidemia (272.4 [other and unspecified hyperlipidemia], 272.0 [pure hypercholesterolemia], and 272.2 [mixed hyperlipidemia]).27,28 We created indicator variables for each individual comorbidity and included the indicators as separate potential covariates in multivariate analyses.

Statistical Methods

Standard statistical tests, including t tests for continuous variables and Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables, were used to make comparisons between RCC and matched comparison group patients.

Patients in the SEER-Medicare database had variable followup time periods. Therefore, our approach to estimating costs at 1 year and 5 years was the method proposed by Bang and Tsiatis (2000), which accounts for patient censoring due to variable follow-up.29 In this study, patients were censored if their last follow-up preceded their date of death, which could indicate last follow-up or loss to follow-up. This approach estimates costs for each patient at regular time intervals (e.g., monthly) and weights those estimates by the inverse of the probability that the patient is not censored within the month. Bang and Tsiatis recommend a nonparametric estimator of the inverse probability, obtained from a Kaplan-Meier estimator of time to censoring. Using 60 monthly observation periods, we weighted the monthly costs for each patient who was uncensored in that month by the inverse probability and then summed the weighted costs to estimate 5-year average cumulative costs. The same process was repeated for 1-year costs using 12 monthly observations. This process was done separately for RCC cases and comparison group patients.

Multivariate analyses were performed using the inverse probability weighting (IPW) approach suggested by Lin (2000), which extends the method of Bang and Tsiatis to a multivariate setting.30 Using this approach, each of the 60 monthly costs was fit to a linear model, where covariates included patient, disease, and treatment variables. Coefficients for months 1 through 12 were summed to give marginal effects of covariates on 1-year costs; coefficients for months 1 through 60 were summed to give marginal effects on 5-year costs. Although a closed-form solution for standard errors exists for this method, it assumes data are normally distributed. Our cost data were highly skewed. Therefore, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained from 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R (2.13.0), open source software available at: http://www.r-project.org/.

Results

The final sample included 4,938 patients with RCC and 9,876 noncancer comparison group cases (Table 2). The groups were comparable in age (P = 0.783), gender (56.7% male in both groups, P = 0.981), and race (84.6% white in both groups, P = 1.000). The comorbidity burden was relatively low, with most patients in both groups (61.9%) having no comorbidities. Most RCC patients (46.2%) had local disease as opposed to regional (18.4%) or distant (27.3%) disease (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of SEER-Medicare Patients with RCC and Matched Disease-Free Comparison Group Cases

| RCC Patients n = 4,938 |

Comparison Group n = 9,876 |

P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age in years | 0.783 | ||

| 65–69 | 1,282 (26.0) | 2,602 (26.3) | |

| 70–74 | 1,285 (26.0) | 2,591 (26.2) | |

| 75–79 | 1,119 (22.7) | 2,174 (22.0) | |

| 80–84 | 701 (14.2) | 1,445 (14.6) | |

| 85 or older | 551 (11.2) | 1,064 (10.8) | |

| Sex | 0.981 | ||

| Male | 2,798 (56.7) | 5,598 (56.7) | |

| Female | 2,140 (43.3) | 4,278 (43.3) | |

| Race | 1.000 | ||

| White | 4,176 (84.6) | 8,357 (84.6) | |

| Black | 372 (7.5) | 744 (7.5) | |

| Asian | 123 (2.5) | 247 (2.5) | |

| Hispanic | 130 (2.6) | 259 (2.6) | |

| Other | 137 (2.8) | 269 (2.7) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Indexb | 1.000 | ||

| 0 | 3,057 (61.9) | 6,116 (61.9) | |

| 1 | 1,035 (21.0) | 2,072 (21.0) | |

| 2 | 500 (10.1) | 1,001 (10.1) | |

| 3 | 177 (3.6) | 355 (3.6) | |

| 4 or more | 169 (3.4) | 332 (3.4) | |

| Anemiab | 0.965 | ||

| No | 4,554 (92.2) | 9,110 (92.2) | |

| Yes | 384 (7.8) | 766 (7.8) | |

| Hypercalcemiab | 0.549 | ||

| No | 4,927 (99.8) | 9,859 (99.8) | |

| Yes | 11 (0.2) | 17 (0.2) | |

| Hyperlipidemiab | 0.980 | ||

| No | 3,335 (67.5) | 6,672 (67.6) | |

| Yes | 1,603 (32.5) | 3,204 (32.4) | |

P values based on Pearson chi-square tests.

All comorbidities were identified from codes during the year prior to RCC diagnosis (RCC cohort) or the assigned pseudo-diagnosis date (comparison cohort).

RCC = renal cell carcinoma; SEER = Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results.

Cumulative unadjusted costs for each of the first 5 years following diagnosis are summarized in Table 3. In the year following diagnosis, per patient per month (PPPM) costs were 4.6 times greater for patients with RCC than for matched comparisons ($3,673 vs. $793, respectively). In subsequent years, PPPM costs fell but were still 26%–71% greater among RCC patients. Also of interest is the fact that PPPM costs for RCC patients increased by stage. For example, in the first year following diagnosis, patients with regional disease had PPPM costs that were 24% greater than those of patients with local disease ($2,913 vs. $3,616), and patients with distant disease had costs that were 105% greater than those of patients with local disease ($2,913 vs. $5,984). This difference across stage of disease largely held across each of the 5 years of follow-up.

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted Costs Per Patient Per Month, with Stratification by Disease Stage

| Comparison Group | RCC Group by Stage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCC Group | Local | Regional | Distant | Unstaged | ||

| First Year Post-Diagnosis/Pseudo-Diagnosisa | ||||||

| N of patients | 9,876 | 4,938 | 2,281 | 908 | 1,343 | 406 |

| N of enrolled months | 112,389 | 45,173 | 25,594 | 9,083 | 7,512 | 2,984 |

| Total costsb | $89,132,023 | $165,941,231 | $74,552,587 | $32,841,816 | $44,954,462 | $13,592,366 |

| Mean PPPM cost | $793 | $3,673 | $2,913 | $3,616 | $5,984 | $4,555 |

| Median (IQR) cost per patient | $1,596 ($380–$6,703) | $26,006 ($16,831–$40,944) | $25,779 ($18,808–$37,395) | $28,059 ($19,535–$43,871) | $25,037 ($12,294–$44,332) | $23,775, ($10,143–$47,584) |

| Second Year Post-Diagnosis/Pseudo-Diagnosisa | ||||||

| N of patients | 8,861 | 3,146 | 2,018 | 654 | 301 | 173 |

| N of enrolled months | 96,095 | 32,613 | 21,882 | 6,644 | 2,396 | 1,691 |

| Total costsb | $67,561,027 | $39,282,100 | $20,834,579 | $9,419,170 | $5,243,119 | $3,785,232 |

| Mean PPPM cost | $703 | $1,204 | $952 | $1,418 | $2,188 | $2,238 |

| Median (IQR) cost per patient | $1,318 ($311–$4,931) | $3,201 ($1,029–$12,717) | $2,552 ($936–$8,945) | $3,671 ($1,099–$15,652) | $9,727 ($2,954–$22,098) | $8,915 ($2,051–$28,633) |

| Third Year Post-Diagnosis/Pseudo-Diagnosisa | ||||||

| N of patients | 7,032 | 2,288 | 1,610 | 450 | 126 | 102 |

| N of enrolled months | 74,590 | 23,633 | 17,036 | 4,507 | 1,125 | 965 |

| Total costsb | $55,457,279 | $25,846,743 | $16,551,410 | $4,654,219 | $2,889,282 | $1,751,833 |

| Mean PPPM cost | $743 | $1,094 | $972 | $1,033 | $2,568 | $1,815 |

| Median (IQR) cost per patient | $1,302 ($311–$5,217) | $2,514 ($782–$10,639) | $2,142 ($700–$8,316) | $2,766 ($833–$10,570) | $10,939 ($2,695-$28,256) | $6,703 ($1,743–$22,022) |

| Fourth Year Post-Diagnosis/Pseudo-Diagnosisa | ||||||

| N of patients | 5,247 | 1,615 | 1,203 | 292 | 59 | 61 |

| N of enrolled months | 52,413 | 15,925 | 11,969 | 2,895 | 513 | 548 |

| Total costsb | $39,941,264 | $15,244,203 | $11,415,645 | $2,473,169 | $561,199 | $794,190 |

| Mean PPPM cost | $762 | $957 | $954 | $854 | $1,094 | $1,449 |

| Median (IQR) cost per patient | $1,259 ($288–$4,984) | $2,190 ($625–$8,521) | $2,073 ($572–$7,912) | $2,211 ($723–$8,705) | $2,613 ($670–$12,462) | $3,124 ($676–$15,066) |

| Fifth Year Post-Diagnosis/Pseudo-Diagnosisa | ||||||

| N of patients | 3,420 | 1,028 | 773 | 193 | 32 | 30 |

| N of enrolled months | 36,753 | 10,983 | 8,337 | 2,024 | 325 | 297 |

| Total costsb | $25,545,684 | $11,094,933 | $8,125,178 | $2,058,501 | $470,498 | $440,755 |

| Mean PPPM cost | $695 | $1,010 | $975 | $1,017 | $1,448 | $1,484 |

| Median (IQR) cost per patient | $1,415 ($363–$5,290) | $2,433 ($807–$11,364) | $2,333 ($804–$9,298) | $2,551 ($835–$14,697) | $3,088 ($1,051–$28,467) | $4,755 ($579–$21,140) |

Noncancer patients were randomly assigned an artificial date of diagnosis from available diagnosis dates of cancer patients. These dates were drawn randomly with replacement and were required to be before the date of death (or the same month). The first year of observation started on the diagnosis date (RCC) or pseudo-diagnosis date (comparison).

Average cumulative all-cause medical costs per patient were $24,424 and $48,026 higher for patients with RCC than for matched comparison enrollees during the first 1 and 5 years, respectively, after RCC diagnosis.

IQR = interquartile range; PPPM = per patient per month; RCC = renal cell carcinoma.

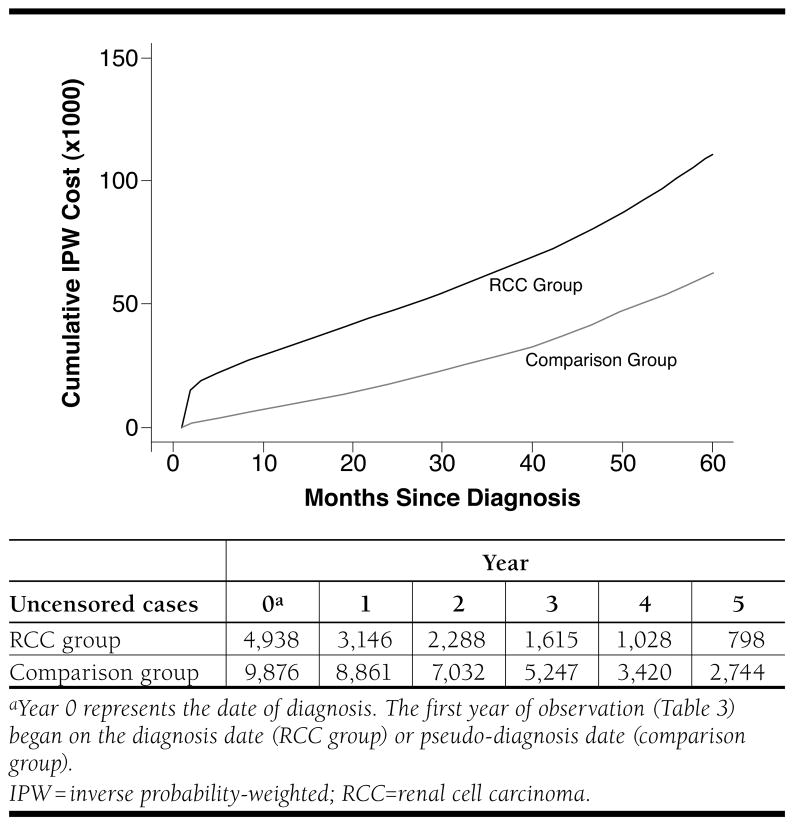

Cumulative costs over time are presented in Figure 2. These curves display the average cumulative costs starting at diagnosis and continuing up to 5 years following diagnosis for RCC and comparison group patients. The costs are calculated under the assumption that the patient survives up to the time period specified on the x-axis. At 1 year following diagnosis, RCC patients had accumulated an average cost of $33,685 per patient, while comparison group patients had accumulated an average cost of $9,261 per patient. By 5 years, cumulative costs per patient were $110,798 for RCC patients and $62,772 for comparison patients. Thus, the unadjusted differences in all-cause cumulative costs were $24,424 by year 1 and $48,026 by year 5.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative Costs for Patients with RCC and Matched Disease-Free Comparison Group Cases

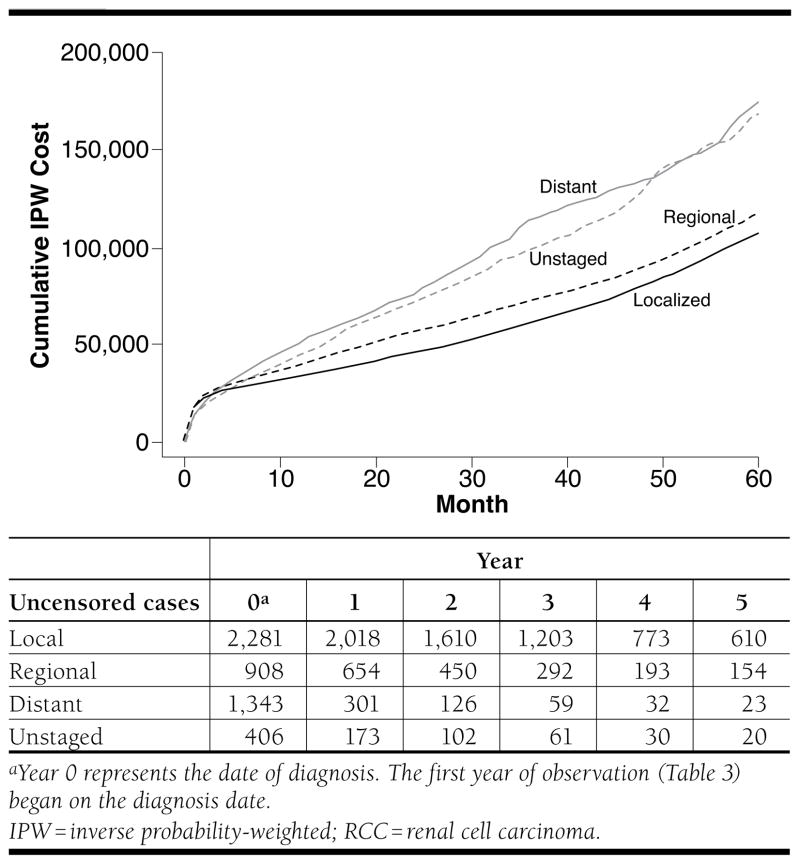

Figure 3 presents the unadjusted IPW cumulative all-cause costs for patients with RCC stratified by disease stage. As expected, patients with localized and regional disease accumulated less in total costs than patients with distant disease or who were unstaged. By year 5, total cumulative costs were $104,652, $114,673, $169,837, and $165,032 for patients with localized, regional, distant, and unstaged disease, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative Costs for Patients with RCC, Stratified by Disease Stage

In multivariate analyses using IPW-partitioned regression for both RCC and comparison patients, several patient-specific factors were associated with 1-year and 5-year all-cause costs (Table 4). Older age was generally associated with higher costs, although not for all age groups, and not all effects were statistically significant. Black race was associated with higher costs at both 1 year ($2,687, 95% CI = $840–$4,572) and 5 years ($11,953, 95% CI = $7,211–$17,121). Comorbidities were associated with higher costs. Anemia and the CCI were significantly associated with costs at both 1 and 5 years. Hyperlipidemia had a significant association at 5 years but not at 1 year. After controlling for other factors, the incremental effect of RCC was estimated to be $22,340 (95% CI = $20,833–$24,017) at 1 year and $20,976 (95% CI = $17,544–$24,572) at 5 years.

TABLE 4.

Inverse Probability-Weighted Regression of 1-Year and 5-Year Costs, All Study Patientsa

| 1-Year Costs | 5Year Costs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient ($) | 95% CI ($) | Coefficient ($) | 95% CI ($) |

| Intercept | 5,370 | 4,611–6,079 | 26,602 | 24,816–28,401 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 65–69 | Reference | |||

| 70–74 | 4,018 | 1,651–6,647 | 7,098 | 1,737–12,434 |

| 75–79 | 5,049 | 2,602–7,514 | 4,718 | −397–9,959 |

| 80–84 | 2,057 | −681–4,919 | 250 | −6,269–6,810 |

| 85 or older | −2,085 | −4,993–588 | −10,729 | −16,461–−3,811 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 17 | −775–739 | −205 | −2,144–1,684 |

| Female | Reference | 0 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference | 0 | ||

| Black | 2,687 | 840–4,572 | 11,953 | 7,211–17,121 |

| Asian | −1,145 | −3,525–1,457 | 2,630 | −4,355–10,033 |

| Hispanic | −3,872 | −5,662–−2,015 | −2,923 | −9,304–5,207 |

| Other | −1,779 | −3,787–416 | −150 | −7,304–7,391 |

| Anemiab | 3,441 | 1,916–5,048 | 6,606 | 2,232–11,064 |

| Hyperlipidemiab | 88 | −784–987 | 4,745 | 2,390–7,039 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Indexb | 4,886 | 4,351–5,450 | 10,857 | 9,547–12,188 |

| RCC | 22,340 | 20,833–24,017 | 20,976 | 17,544–24,572 |

N = 14,814 total patients (n = 4,938 cases and n = 9,876 comparison cohort).

All comorbidities were identified from codes during the year prior to RCC diagnosis (RCC cohort) or the assigned pseudo-diagnosis date (comparison cohort).

CI = confidence interval; RCC = renal cell carcinoma.

We also performed multivariate analyses of 1- and 5-year all-cause costs among just RCC patients, controlling for disease, treatment, and patient characteristics (Table 5). Several patient and disease factors were significantly associated with accumulated costs at 1 year. Age had an inverted “U”-shaped effect on costs at 1 year. Patients aged 70–74 years incurred on average $4,463 (95% CI = $2,127–$6,676) in higher costs, and patients aged 85 years or older incurred on average $5,016 (95% CI = $2,175–$8,169) in higher costs, compared with patients aged 65–69 years. In addition, black patients had approximately $5,499 (95% CI = $1,699–$9,698) higher costs than white patients. Gender was not a significant determinant of 1-year costs. Disease stage was a significant determinant of costs, as patients with regional disease accumulated $3,704 (95% CI = $1,209–$6,179), and patients with distant metastases accumulated $4,482 (95% CI = $1,709–$7,505) higher costs compared with patients who had localized disease. Laterality of disease was not significantly associated with 1-year costs. Comorbidities were a substantial driver of costs, with each 1-point increase in the CCI associated with $4,493 (95% CI = $3,611–$5,455) in higher costs. Hyperlipidemia was also associated with an increase in costs of approximately $2,745 (95% CI = $836–$4,571).

TABLE 5.

Inverse Probability-Weighted Regression of 1-Year and 5-Year Costs, Patients with RCCa

| 1-Year Costs | 5-Year Costs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient ($) | 95% CI ($) | Coefficient ($) | 95% CI ($) |

| Intercept | 25,539 | 23,286–27,757 | 56,166 | 51,203–61,228 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 65–69 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 70–74 | 4,463 | 2,127–6,676 | 8,216 | 3,417–12,847 |

| 75–79 | 6,934 | 4,269–9,663 | 8,754 | 3,687–13,849 |

| 80–84 | 5,868 | 3,143–8,742 | 8,551 | 2,778–15,187 |

| 85 or older | 5,016 | 2,175–8,169 | 4,518 | −2,016–11,208 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | −840 | −2,461–788 | −935 | −4,515–2,450 |

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 5,499 | 1,699–9,698 | 25,027 | 14,383–36,274 |

| Asian | −2,712 | −7,225–1,457 | 6,011 | −6,262–20,027 |

| Hispanic | −4,197 | −8,534–406 | −9,226 | −18,654–1,773 |

| Other | 900 | −3,694–5,932 | −1,920 | −10,346–7,613 |

| Laterality | ||||

| Right | Reference | Reference | ||

| Left | 611 | −1,156–2,300 | 801 | −3,064–4,938 |

| Paired | −3,362 | −8,015–959 | −7,866 | −16,039–2,095 |

| Stage | ||||

| Localized | Reference | Reference | ||

| Regional | 3,704 | 1,209–6,179 | −3,826 | −8,515–1,043 |

| Distant | 4,482 | 1,709–7,505 | −16,849 | −23,157–−10,726 |

| Unstaged | 7,597 | 3,512–11,523 | 609 | −8,039–9,442 |

| Anemia | 2,167 | −768–5,373 | 1,113 | −6,070–8,337 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2,745 | 836–4,571 | 2,551 | −1,295–6,537 |

| Charlson Indexb | 4,493 | 3,611–5,455 | 9,505 | 7,248–11,907 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Surgery | Reference | Reference | ||

| Radiation | −6,092 | −10,830–−1,810 | −12,830 | −20,453–−5,584 |

| Surgery and radiation | 24,556 | 16,673–32,940 | 30,540 | 17,853–43,648 |

| Chemotherapy | 15,144 | 9,979–20,344 | 13,440 | 1,257–27,572 |

| No treatment | −12,722 | −15,649–−9,952 | −23,648 | −29,759–−17,980 |

N = 4,938 patients.

All comorbidities were identified from codes during the year prior to RCC diagnosis (RCC cohort) or the assigned pseudo-diagnosis date (comparison cohort).

CI = confidence interval; RCC = renal cell carcinoma.

Treatment choice was significantly associated with 1-year all-cause costs. Compared with patients who received surgery alone, patients who received radiation therapy alone had $6,092 (95% CI = −$10,830–−$1,810) lower costs; patients who received surgery plus radiation had $24,556 (95% CI = $16,673–$32,940) higher costs; patients who had chemotherapy had $15,144 (95% CI = $9,979–$20,344) higher costs; and patients who had no treatment recorded had $12,722 (95% CI = −$15,649–−$9,952) lower costs. These lower treatment costs were most likely associated with earlier mortality for more aggressive pathologic stage, as suggested by previous research.2

Similar effects were observed for average costs at 5 years following diagnosis, including significant effects of age, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, and treatment (Table 5). Only distant stage remained statistically significant and reversed direction from positive in the 1-year equation to negative (−$16,849, 95% CI = −$23,157–−$10,726) for 5-year costs, and the magnitude of the impact of chemotherapy fell relative to its effect on 1-year costs.

Discussion

In this large sample of Medicare patients, we found that RCC imposes a significant cost burden relative to similar Medicare patients without RCC. During the first year following diagnosis, Medicare paid an average of $3,673 PPPM for RCC patients and only $793 PPPM among enrollees without cancer. We also showed that total 1-year and 5-year costs are significantly associated with age, race/ethnicity, stage of disease, and treatment choice, among other factors.

Increased use of abdominal axial imaging coupled with an aging population have contributed to a steady increase in the detection and reported incidence of RCC. Chow et al. (1999) found that incidence rates increased annually by 2.3% among white men, 3.1% among white women, 3.9% among black men, and 4.3% among black women between 1975 and 1995. While this increase is most significant for clinically localized lesions, they also noted an increase in advanced cases of RCC as well.6 Diagnosing a greater number of RCCs likely confers an incremental cost attributable to detection, treatment, and continued surveillance. In this study, we utilized the SEERMedicare database with an inherent comparison group sample to characterize costs associated with RCC.

A principal challenge prior to initiating cost comparison is identifying a suitable comparison group sample. We constructed a comparison group using propensity score matching that allowed us to match the distribution of covariates to the RCC cohort and maintain a large sample size. In fact, the distribution of measured patient characteristics was virtually identical between the RCC and comparison group sample. Thus, we are confident that remaining differences in outcomes between these 2 groups are not due to the observable characteristics that formed the basis of the matching model. Of course, they may still be due to variables that we did not observe and on which we were not able to match.

When evaluating incurred all-cause costs following diagnosis, we found that RCC patients had a significantly higher accumulated cost both within the first year and between the first and fifth years when compared with comparison group patients without chronic renal disease. This magnitude of increase was most pronounced within the first year, which likely reflects the burden of treatment for RCC. Additionally, costs remained higher beyond the first year of diagnosis in the RCC patients. These higher costs are likely to be due to costs associated with post-treatment surveillance, treatment incurred in patients initially managed by observation, sequelae of complications attributable to the primary therapy, and secondary malignancies that may be detected during follow-up regimens.31,32

Given the observed cost burden in RCC patients, we identified that demographic, pathologic, and therapy-related variables all contributed to costs of RCC care. Specifically, patients aged 70 years or older had higher associated costs than Medicare patients younger than 70 years. While prior work has suggested the feasibility of RCC treatments in older patients, several have implicated longer hospitalizations and complication rates between 7% and 10%.33,34 Furthermore, older patients appear more likely to undergo a radical as opposed to a partial nephrectomy with a likely sequela of chronic kidney disease.35 Collectively, all of these variables can contribute to higher costs in the aged RCC population even in this dataset, which did not include outpatient prescription drug costs because none of the patients in this sample had access to Medicare Part D. In addition to age, black race was associated with higher RCC costs. While access to health care is presumably similar, prior work from the SEER-Medicare database has implicated differences in the use of surgical and systemic therapy regimens between racial groups.36,37 Furthermore, recent work has identified higher RCC incidence rates and lower survival rates among black patients compared with white counterparts.2,38 Such differences may manifest as cost differences associated with RCC.

Limitations

First, the restriction of cases to Medicare patients aged 65 years or older limits the generalizability of our findings. Whereas the overall 5-year survival rate for cancer of the kidney and renal pelvis in the SEER database is 70%, only 21% of the present study sample was still in the SEER-Medicare database at the beginning of the fifth year after diagnosis. Second, we studied all-cause medical costs, not costs for claims specific to RCC diagnoses or treatments, and we did not have access to data on prescription drug use because the study period preceded implementation of the Medicare Part D drug benefit. Third, our study lacked analysis of some socioeconomic factors such as income and education, which are potential contributors to the racial differences that were observed. Fourth, since missing data may be more frequent among patients with the most severe disease, cost estimates may be biased in this group. Finally, due to the era studied, we were not able to directly investigate the role of newer targeted therapies on the economic burden of RCC. For example, these patients were treated before the availability of such targeted agents as sunitinib, sorafenib, and temsirolimus. Because we lacked outpatient prescription drug data, we were also unable to identify how many patients were treated with interferon or interleukin-2.

Conclusions

Among Medicare patients, RCC is associated with a significant economic burden. The extent of this economic burden is determined by several patient characteristics and disease factors. Despite study limitations, these results may be informative to health care policy makers and other payers who cover elderly patients at risk for RCC.

What is already known about this subject

The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) summary staging system has 5 stages of renal cell carcinoma (RCC): in situ, local, regional, distant, and unstaged (unknown). Regional disease is cancer that has spread to nearby organs or lymph nodes, and distant disease is cancer that has spread from the primary organ site to distant organs or distant lymph nodes. Among patients with invasive RCC, presentation at diagnosis is approximately 17% for regional stage and 11% for distant stage.

Little is known about costs associated with RCC, particularly for elderly Medicare patients, who account for 46% of new diagnoses.

What this study adds

In a sample of Medicare enrollees aged 65 years or older, RCC was associated with average all-cause per patient per month (PPPM) medical cost of $3,673 during the first year compared with $793 PPPM for similar Medicare patients without RCC.

Average cumulative all-cause medical costs per patient were $24,424 and $48,026 higher for patients with RCC than for matched comparison enrollees during the first 1 and 5 years, respectively, after RCC diagnosis.

The economic burden of RCC is determined by several patient, disease, and treatment factors, including age, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, use of combined surgery and radiation, and use of chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Erik B. Lehman, MS, Biostatistician/Scientific Coordinator, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania, contributed to data collection, data interpretation, writing, and revision of the original manuscript submission.

This study used the linked Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

This study was supported by a research grant from Wyeth, Inc., which was acquired by Pfizer in October 2009. Hollenbeak, Ghahramani, Raman, and Schaefer are employees of Penn State College of Medicine, which received financial support from Wyeth, Inc., in connection with the development of this manuscript. Alemao was an employee of Wyeth, Inc., at the time of the study. Hollenbeak disclosed service on an advisory board for Amgen and has provided consulting services for United Biosource Corporation, Remel, and Catheter Connections.

Concept and design were performed primarily by Hollenbeak with the assistance of Alemao. Data were collected primarily by Hollenbeak and interpreted primarily by Hollenbeak, Schaefer, and Nikkel. The manuscript was written by Hollenbeak and Ghahramani with the assistance of the remaining authors and revised primarily by Hollenbeak, Ghahramani, and Raman.

Contributor Information

Christopher S. Hollenbeak, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Lucas E. Nikkel, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Eric W. Schaefer, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Evo Alemao, Global Health Economics and Outcomes Research, Wyeth, Inc., Collegeville, Pennsylvania.

Nasrollah Ghahramani, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Jay D. Raman, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Lang K, Danchenko N, Gondek K, Schwartz B, Thompson D. The burden of illness associated with renal cell carcinoma in the United States. Urol Oncol. 2007;25(5):368–75. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollenbeak CS, Mallick R, Lehman E, Ghahramani N, Reese CT. Treatment and survival among Medicare patients with renal cell carcinoma. [Accessed September 3, 2011];Kidney Cancer Journal. 2010 8(2):38–50. Available at: http://www.kidney-cancer-journal.com/medicare_v8n2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trohi A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2008. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2011. [Accessed September 3, 2011]. based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2007. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Accessed September 3, 2011]. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/caff2007pwsecuredpdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow WH, Devesa SS, Warren JL, Fraumeni JF., Jr Rising incidence of renal cell cancer in the United States. [Accessed September 3, 2011];JAMA. 1999 281(17):1628–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1628. Available at: http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10235157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pantuck AJ, Zisman A, Belldegrun AS. The changing natural history of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2001;166(5):1611–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2477–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(3):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell RJ, Broaddus SB, Leadbetter GW., Jr Staging of renal cell carcinoma: cost-effectiveness of routine preoperative bone scans. Urology. 1985;25(3):326–29. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fielding JR, Aliabadi N, Renshaw AA, Silverman SG. Staging of 119 patients with renal cell carcinoma: the yield and cost-effectiveness of pelvic CT. [Accessed September 3, 2011];AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999 172(1):23–25. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.1.9888732. Available at: http://www.ajronline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9888732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindner A, Goldman DG, deKernion JB. Cost effective analysis of prenephrectomy radioisotope scans in renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 1983;22(2):127–29. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(83)90491-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rámak E, Charbonneau C, Négrier S, Kim ST, Motzer RJ. Economic evaluation of sunitinib malate for the first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. [Accessed September 3, 2011];J Clin Oncol. 2008 26(24):3995–4000. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2662. Available at: http://www.jco.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18711190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadler E, Eckert B, Neumann PJ. Do oncologists believe new cancer drugs offer good value? [Accessed September 3, 2011];Oncologist. 2006 11(2):90–95. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-90. Available at: http://the-oncologist.alphamedpress.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16476830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allareddy V, Konety BR. Inpatient costs for bladder, kidney, and prostate cancers in the year 2002. A study using the NIS sample; Poster presented at: American Urological Association Annual Meeting; May 21, 2006; Atlanta, GA. [Accessed September 3, 2011]. Available at: http://www.abstracts2view.com/aua_archive/view.php?nu=200691698. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed September 3, 2011];SEER-Medicare: about the data files. 2010 Oct; Available at: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/aboutdata/

- 18.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed September 3, 2011];SEER-Medicare: number of cases for selected cancers appearing in the data. 2009 Feb; Available at: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/aboutdata/cases.html.

- 19.Bergstralh E, Kosanke J. GMATCH macro. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; Oct, 2003. [Accessed September 3, 2011]. Available at: http://cancer-center.mayo.edu/mayo/research/biostat/sasmacros.cfm/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–19. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young JL Jr, Roffers SD, Ries LAG, Fritz AG, Hurlbut AA, editors. NIH Pub No 01-4969. Bethesda, MD: 2001. SEER Summary Staging Manual - 2000: Codes and Coding Instructions. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren JL, Harlan LC, Fahey A, et al. Utility of the SEER-Medicare data to identify chemotherapy use. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-55–61. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020944.17670.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollenbeak CS, Stack BC, Jr, Daley SM, Piccirillo JF. Using comorbidity indexes to predict costs for head and neck cancer. [Accessed September 3, 2011];Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 133(1):24–27. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.1.24. Available at: http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17224517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gettman MT, Boelter CW, Cheville JC, Zincke H, Bryant SC, Blute ML. Charlson co-morbidity index as a predictor of outcome after surgery for renal cell carcinoma with renal vein, vena cava or right atrium extension. J Urol. 2003;169(4):1282–86. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000049093.03392.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froehner M. Re: Charlson co-morbidity index as a predictor of outcome after surgery for renal cell carcinoma with renal vein, vena cava or right atrium extension. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1954. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000088702.36081.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P, Mazumdar M. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. [Accessed September 3, 2011];J Clin Oncol. 2002 20(1):289–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.289. Available at: http://www.jco.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11773181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mekhail TM, Abou-Jawde RM, Boumerhi G, et al. Validation and extension of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering prognostic factors model for survival in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. [Accessed September 3, 2011];J Clin Oncol. 2005 23(4):832–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.179. Available at: http://www.jco.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15681528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bang H, Tsiatis AA. Estimating medical costs with censored data. Biometrika. 2000;87(2):329–43. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin DY. Linear regression analysis of censored medical costs. Biostatistics. 2000;1(1):35–47. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abouassaly R, Lane BR, Novick AC. Active surveillance of renal masses in elderly patients. J Urol. 2008;180(2):505–08. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng CS, Wood CG, Silverman PM, Tannir NM, Tamboli P, Sandler CM. Renal cell carcinoma: diagnosis, staging, and surveillance. [Accessed September 3, 2011];AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 191(4):1220–32. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3568. Available at: http://www.ajronline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18806169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cobb WS, Heniford BT, Matthews BD, Carbonell AM, Kercher KW. Advanced age is not a prohibitive factor in laparoscopic nephrectomy for renal pathology. Am Surg. 2004;70(6):537–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pareek G, Yates J, Hedican S, Moon T, Nakada S. Laparoscopic renal surgery in the octogenarian. [Accessed September 3, 2011];BJU Int. 2008 101(7):867–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07368.x. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1464–4096&date=2008&volume=101&issue=7&spage=867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson RH, Ordonez MA, Iasonos A, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in young and old patients—is there a difference? [Accessed September 3, 2011];J Urol. 2008 180(4):1262–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.037. discussion 1266. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/18707708/?tool=pubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saigal CS, Deibert CM, Lai J, Schonlau M. Disparities in the treatment of patients with IL-2 for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. [Accessed September 3, 2011];Urol Oncol. 2010 8(3):308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.09.022. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/19070518/?tool=pubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zini L, Perrotte P, Capitanio U, et al. Race affects access to nephrectomy but not survival in renal cell carcinoma. [Accessed September 3, 2011];BJU Int. 2009 103(7):889–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08119.x. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08119.x/full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stafford HS, Saltzstein SL, Shimasaki S, Sanders C, Downs TM, Sadler GR. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in renal cell carcinoma incidence and survival. [Accessed September 3, 2011];J Urol. 2008 179(5):1704–08. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.027. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/18343443/?tool=pubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]