Abstract

The physical arrangement of receptive fields (RFs) within neural structures is important for local computations. Nonuniform distribution of tuning within populations of neurons can influence emergent tuning properties, causing bias in local processing. This issue was studied in the auditory system of barn owls. The owl’s external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICx) contains a map of auditory space where the frontal region is overrepresented. We measured spatiotemporal RFs of ICx neurons using spatial white noise. We found a population-wide bias in surround suppression such that suppression from frontal space was stronger. This asymmetry increased with laterality in spatial tuning. The bias could be explained by a model of lateral inhibition based on the overrepresentation of frontal space observed in ICx. The model predicted trends in surround suppression across ICx that matched the data. Thus, the uneven distribution of spatial tuning within the map could explain the topography of time-dependent tuning properties. This mechanism may have significant implications for the analysis of natural scenes by sensory systems.

Keywords: Sound localization, spatiotemporal receptive field, inferior colliculus, barn owl, surround bias

Introduction

Sensory areas are often topographically organized (Hubel and Wiesel, 1965; Knudsen and Konishi, 1978a; Schwartz, 1980; Kaas, 1997; Sceniak et al., 1999; Tsui et al., 2010). However, these sensory maps are not exact isomorphic representations of the environment, as they show enlargement in regions that are relevant to the organism’s behavior. Representation of sound in the auditory system shows expansion of frequency bands that are important for echolocation and vocalization (Pollak and Bodenhamer, 1981; Rübsamen et al., 1988; Portfors et al., 2009). In the visual system, expansions are also observed in areas representing the frontal visual field (Hubel and Wiesel, 1974; Quevedo et al., 1996). It is assumed that these overrepresentations enhance the processing power of behaviorally relevant cues (Rübsamen et al., 1988; King, 1999; Portfors et al., 2009; Pienkowski and Eggermont, 2011).

In the barn owl’s auditory system, the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICx) displays a map of auditory space (Knudsen and Konishi 1978a). Binaural cues for azimuth and elevation are processed in separate pathways and combined in the midbrain to synthesize ICx’s spatial RFs (Moiseff and Konishi, 1983; Takahashi et al., 1984). Each ICx represents mostly frontal and contralateral space, where frontal space is overrepresented (Knudsen and Konishi, 1978a). There is also overrepresentation of frontal space in the optic tectum (OT), which receives direct projections from ICx (Knudsen, 1982; Knudsen and Knudsen, 1983). This nonuniform representation of auditory space may be advantageous in orienting behaviors (Walker et al., 1999; Fischer and Pena, 2011).

RFs in ICx exhibit center-surround organization (Knudsen and Konishi, 1978b), a commonly observed property (Hubel and Wiesel, 1962; Jones and Palmer, 1987; Wagner et al., 1987; Moore et al., 1999). The center-surround configuration provides a means for contrast enhancement and the extraction of dynamic stimulus features. For example, center-surround organization underlies edge detection in the visual system (Schwartz, 1980; Wagner et al., 1987; Kaas, 1997; Sceniak et al., 1999; Tsui et al., 2010), fine touch discrimination in the somatosensory system (Lavallee and Deschenes, 2004; Foeller et al., 2005), and sharp spectral tuning in the auditory system (Kanwal et al., 1999; Ma and Suga, 2004). It also allows for detection of time-dependent properties, such as stimulus motion in the visual (Cavanaugh et al., 2002; Tailby et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2011) and somatosensory systems (Fucke et al., 2011; Kremer et al., 2011). Thus, uneven topography in neural representations could have an effect on RF properties by affecting the surround and in turn biasing tuning properties across a population.

The spatial-white noise (SWN) stimulation paradigm used in the visual system (Marmarelis and Naka, 1972; Marmarelis and McCann, 1973; Chichilnisky, 2001) was adapted to analyze spatiotemporal RFs in the auditory system (Jenison et al., 2001; Recio-Spinoso et al., 2005). Across the population of neurons studied, surround suppression was biased towards frontal space; i.e. neurons receive stronger surround suppression from frontal rather than peripheral areas. This bias could be explained by a model of lateral inhibition in a neural population with nonuniform distribution of preferred directions. This RF organization can serve as a substrate for representing time-variant stimulus dynamics.

Methods

Surgery

Adult barn owls (Tyto alba) of both sexes (2 females, 1 male) were restrained with a soft cloth jacket and anesthetized with intramuscular injections of ketamine hydrochloride (20 mg/kg; Ketaset) and xylazine (4 mg/kg; Anased). The depth of anesthesia was monitored by pedal reflex. An adequate level of anesthesia was maintained with supplemental injections of ketamine and xylazine during the experiment. At the beginning of each session, prophylactic antibiotics (ampicillin; 20 mg/kg, I/M) and lactated Ringer’s solution (10 ml, subcutaneous) were administered. Body temperature was maintained throughout the experiment with a heating pad (Sports Imports LLC). In an initial surgery, the owl’s head was held in a custom-built stereotaxic device. A stainless steel plate and a reference post were affixed to the skull with dental cement to reproduce stereotaxic coordinates in subsequent experiments. Dental acrylic wells were built around coordinates for ICx over the left and right hemispheres. A craniotomy was performed within the wells at the coordinates of the recording sites, where a small incision was made in the dura mater for electrode insertion. At the end of each experiment, the craniotomy was covered with a sterile plastic disc and the well was filled with a fast-curing silicone elastomer (Roylan, Sammons Preston). Owls were returned to their individual cages and monitored for recovery. Depending on the owl’s weight and recovery conditions, experiments were repeated every 7–10 days for a period of several weeks. These procedures comply with guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health and by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Institute of Animal Studies.

Electrophysiology

Single units were extracellularly recorded in ICx using 1MΩ tungsten electrodes (A-M Systems). Tucker Davis Technologies (TDT, System 3) equipment was used to record the neural signals. The TDT equipment was controlled by custom software written in Matlab and TDT RPvdsEx programming environments. Single units were isolated by spike amplitude. Spikes were detected off-line using spike-discrimination software written in Matlab (MathWorks).

ICx was located stereotaxically (Knudsen 1983) and by the unambiguous response of its neurons to interaural time (ITD) and level (ILD) differences. ICx units were distinguished from OT by their shorter latency, absence of bursting firing (Knudsen, 1984) and lack of response to light stimulation. The electrode was advanced with a microdrive (Motion Controller, Model ESP300, Newport) in steps of 100μm until ICx was reached. The step-size was then reduced to 2–4μm to search for and isolate single units.

Acoustic Stimulation

All experiments were performed in a double-walled sound-attenuating chamber (Industrial Acoustics) lined with echo-absorbing acoustical foam (Sonex). Stimuli were delivered in two conditions: dichotic, using earphones, and free-field, using a custom-made array of speakers.

The earphones used for dichotic stimulation consisted of a speaker (Knowles model 1914) and a microphone (Knowles model 1319) housed in a custom-made metal case that fits in the owl’s ear canal. Prior to the experiments, calibration data that translated the Knowles microphone output into sound intensity in dB SPL were collected using a ½ inch Brüel and Kjær microphone (model 4190), a preamplifier (model 2669), and a conditioning amplifier (Nexus model 2690). The calibrated earphone microphones were then used to calibrate the earphone speakers at the beginning of each experiment, after the earphone assembly had been placed inside the owl’s ear canal. Software for stimulus generation (Matlab) used these calibration data to automatically correct irregularities in the amplitude and phase response of each earphone. Auditory stimuli delivered through the earphones consisted of 5 repetitions of 100 ms duration broadband signals (0.5–10 kHz) or tones, with a 5 ms rise-fall time at 10dB above threshold.

The free-field spatial tuning of the neurons was measured using a custom-made hemispherical array of 144 speakers (Sennheiser, 3P127A) constructed inside the sound-attenuating chamber. The speaker array range is ± 100° in azimuth and ± 80° in elevation. The angular separation between the speakers varied from 10° to 30°. The highest density of speakers was located in frontal space, at the center of the array (± 40° from zero) and in the horizontal and vertical axes passing through the origin. Each speaker in the array was calibrated using a ½ inch Brüel and Kjær microphone (model 4190), preamplifier (model 2669), and conditioning amplifier (Nexus model 2690). The calibration apparatus was mounted on a custom-built pan-tilt robot positioned at the center of the array. The robot was used to orient the microphone toward the speaker being calibrated, with fine adjustments by a laser-mounted video camera. Each speaker’s transfer function was then measured using a Golay code technique (Zhou et al., 1992), after which an output RMS voltage versus stimulus-intensity (dB SPL) curve was computed and stored.

Data Collection

For each ICx neuron, we first measured the ITD, ILD, frequency tuning, and rate-intensity response using dichotic stimulation. ITD varied from ±300 μs, where negative represents left-side leading and ILD from ±40 dB, where negative represents sounds louder on the left ear; frequency ranged from 500 Hz to 10 kHz; and sound level varied from 0 dB SPL to 70 dB SPL. Five trials of each test were collected. ITD, ILD, frequency and sound level were randomized during data collection.

The approximate threshold and saturation values for average binaural level were determined by visual inspection of rate-level curves. These values were used for adjusting the level of subsequent dichotic and free-field stimuli.

We searched for ICx neurons responsive to ILDs close to 0, i.e., neurons that displayed response in free-field at ±10° in elevation (Moiseff, 1989). Spatial RFs were mapped for each neuron and data for SWN analysis were subsequently collected.

Receptive Field Mapping

During recordings, the owl was placed in a stereotaxic frame at the center of the speaker array such that all speakers were equidistant (60 cm) from the owl’s head. Auditory stimuli used to measure free-field spatial RFs consisted of 5 repetitions of 100 ms duration broadband signals (0.5–10 kHz) with a 5 ms rise-fall time and amplitude of 50 dB. Stimuli were presented with an inter-stimulus interval (ISI) of 300 ms where speaker location was randomized. We will refer to non-overlapping sound stimulation separated by periods of silence as sequential stimulation.

Spatially-White Noise (SWN) Stimulation

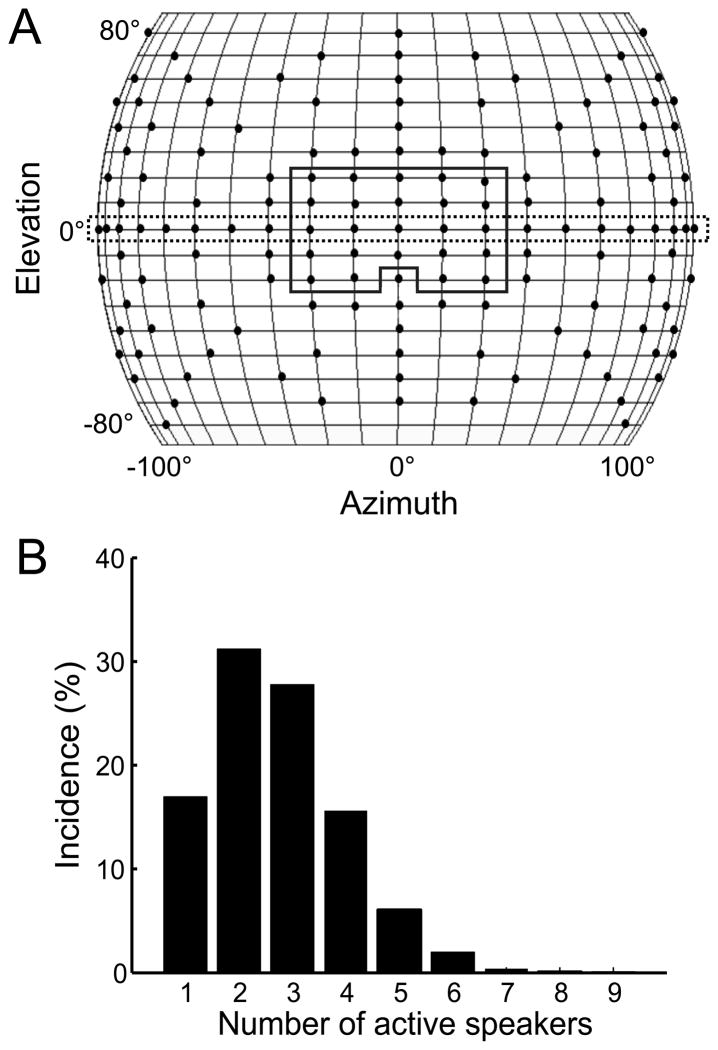

After the spatial RF was mapped, a computer-controlled motor system adjusted the owl’s position so that the RF was centered at 0° azimuth. Because rotation of the recording apparatus was only possible in azimuth, neurons responsive to elevations within 10° around the horizon were selected for further testing. A subset of speakers was used to deliver SWN stimuli. The maximum number of speakers used in SWN was 24, due to multiplexing output limitations. We used a linear array (21 speakers at 0° elevation spanning ±100° in azimuth) or a square array (24 speakers covering ±20° in elevation and ±20° in azimuth) (Figure 1A). Sound stimuli consisted of 15-ms broadband noise bursts (0.5–10 kHz) at 50dB with 5 ms sinusoidal rise-fall times at each speaker location. Randomized ISIs between 200–500 ms were independently generated for each speaker, resulting in a spatially-white (Poisson-like distribution) stimulus (Jenison et al., 2001; Recio-Spinoso et al., 2005). In the SWN stimulus, many speakers may be activated simultaneously or in varying degrees of overlap. The probability of more than 1 speaker being activated during the length of the stimulus was over 80% (Figure 1B). The SWN stimulus was presented for 20–30 minutes during which more than 10,000 spikes were collected and each speaker was activated 3000–4000 times. Sound stimulus waveforms and the ISI sequence for each speaker were generated before the recording began and were saved for reverse-correlation analysis.

Figure 1.

Spatial white-noise stimulation. A) Schematic of the speaker array. The positions of the speakers are indicated by dots. Rectangular boxes show the subsets of speakers used for SWN stimulation. The solid and dashed lines indicate the square and linear arrays, respectively. B) Probability distribution of concurrent speaker activation during SWN. In a majority of instances, more than 1 speaker was simultaneously activated.

Data analysis

To visually assess the spatial tuning of ICx neurons, two-dimensional contour plots were computed for the response to all 144 speakers in the array (Perez et al., 2009).

For SWN analysis, responses to each speaker in the array were sorted by location. Spikes were counted for latencies from 0 to 28 ms. This period includes the response latency of ICx neurons (approximately 10ms) plus the duration of the stimulus (15 ms). An 8 ms sliding time window in steps of 4 ms was used to quantify the number of spikes at different latency from the onset of the stimulus.

The speaker location that elicited the maximum response was referred to as the ‘center speaker.’ To characterize the surround modulation, the interaction between the center speaker and other speakers in the array was calculated by extracting from the dataset instances where a sound emitted at the center was accompanied by a sound from each of the other speakers with temporal precedence between 0 and 60 ms. The 60 ms precedence was subdivided in intervals of 15 ms. Although simultaneous activation from more than 2 speakers often occurred, the statistics of the SWN (Figure 1B) allowed for the datasets to contain hundreds of trials for each pair. The average response of the neuron to the center speaker over the entire length of the dataset was the reference. The effect of each surround speaker was quantified as the percentage change between the average response to the center speaker and the response when the other speaker in the array was also activated. The percent suppression shown in the figures refers to the percent decrease in response to the center speaker induced by each surround speaker quantified with this method.

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of spatial tuning curves was calculated as the ratio of the maximum and the standard deviation of all data points collected using the linear array (Ruderman and Bialek, 1994; Firbank et al., 1999). The Lilliefors test was used to assess normality of datasets.

Model

We constructed a model of lateral inhibition in ICx based on the known distribution of auditory spatial tuning of the barn owl’s ICx and OT (Knudsen and Konishi, 1978a; Knudsen, 1982). ICx provides the auditory input to OT and there are point-to-point projections between these structures (Feldman and Knudsen, 1997; Hyde and Knudsen, 2000; Nieder et al., 2003). Previous anatomical studies of ICx and OT suggest that cell density is uniform throughout them (Knudsen, 1983; Keller and Takahashi, 1996). We thus built the model under the assumption that the auditory spatial-tuning distributions in OT and ICx are similar.

The Matlab function grabit was used to estimate the proportion of OT cells tuned to frontal and peripheral space at 0° elevation, based on published data (Knudsen 1982; see results). A transformed χ2 distribution with 5 degrees of freedom (Equation 1) that best fit the data from Knudsen (1982) was used to model the distribution of preferred direction at 0° elevation in ICx. Thus, the density of preferred azimuth within the population is given by

| (1) |

where x represents tuning directions from −20° to 100° in azimuth.

Inhibitory weights from neighboring cells within ICx were modeled as a Gaussian function of the anatomical distance between cells.

| (2) |

For i≠j, the width of the Gaussian, σ, was determined by observations that surround suppression in ICx cells extends 50–70° to each side of the preferred azimuth (Knudsen and Konishi, 1978b). At the edges of the ICx map, inhibitory weights were truncated to account for the lack of representation beyond 20o ipsilateral and 100o contralateral in azimuth.

An estimate of total surround suppression was calculated by summing the weights on the frontal and peripheral sides of the surround for each neuron. The number of cells that constitutes the surround on each side is defined by the transformed χ2 function used to model the population. In other words, total surround suppression to each side depends on each neuron’s position in the model. The bilateral disparity in suppression was quantified as the percent difference between the sum of the weights on the frontal and peripheral sides of the surround for each neuron.

Results

Spatial RFs measured with SWN

We recorded 91 ICx neurons tuned to sound directions ranging from 0° to 45° in azimuth and −10° to 10° in elevation in both hemispheres. In these cells, we measured spatial tuning in free field and performed SWN analysis. Cells were classified in three groups according to their preferred azimuth: cells tuned to frontal (0°–15°, n = 38), intermediate (15°–30°, n =33) and lateral space (30°–45°, n = 20).

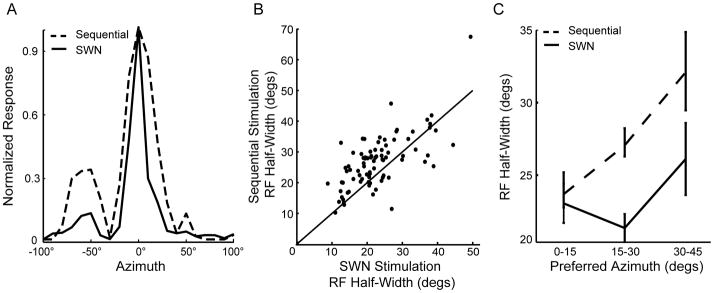

Examples of spatial RFs measured with sequential and SWN stimulation are shown in Figure 2A. Across the population, the average half-width of spatial RFs measured with sequential stimulation was 27 ± 0.7° in azimuth and 53° ± 23° in elevation. The azimuth half-width with SWN stimulation (23 ± 0.9°) was significantly narrower than with sequential stimulation (Figure 2B). The size of the RFs measured with SWN was similar to the smallest-sized RFs obtained using sequential stimulation. In the linear array data, the SNR in all groups was significantly higher using SWN than with sequential stimulation (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.001). Sounds from each speaker were presented at the same intensity in the sequential and SWN conditions. The major difference between the two conditions is that only one speaker was activated at a time during the sequential condition while several speakers could be activated simultaneously in the SWN condition. Thus, the average sound level at the eardrum could be different in SWN, due to multiple speakers being active at a given time. The robust RF sharpening in RFs collected with SWN is consistent with lateral suppression from activation of the surround (Yang et al., 1992; Zhang et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2006; Xing et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Receptive field sharpening during SWN stimulation. A) Example spatial RFs measured using the linear array with sequential stimulation (dashed line) and SWN stimulation (solid line). B) RF half-widths decreased for more than 80% of the neurons (above unity line) from the sequential to the SWN stimulation conditions (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p<0.001). C) RF half-width’s dependence on preferred azimuth for sequential and SWN stimulation. Using sequential stimulation (dashed line), the tuning width increased linearly with preferred azimuth. However, tuning width was not significantly broader among groups in the SWN condition (solid line). RF sizes obtained with sequential stimulation were significantly broader for the intermediate and peripheral groups compared to RFs measured through SWN stimulation (One-way ANOVA, p<0.05). Error bars represent SEM.

In addition, the extent of RF sharpening using SWN stimulation increased with laterality in spatial tuning. Using sequential stimulation, RFs for frontally-tuned cells were, on average, 26% narrower than those in the two peripheral groups (Figure 2C, dotted line). This observation is consistent with previous reports of smaller RFs in frontal space compared to lateral space (Knudsen et al., 1977; Knudsen and Konishi, 1978a). However, RF widths measured with SWN were not significantly different among neurons tuned to frontal, intermediate and lateral locations (One-way ANOVA, p > 0.8; Figure 2C). Thus the RF sharpening in complex auditory scenes such as SWN increases with spatial tuning, making the size of RFs in the recorded range similar to one another.

Population-wide bias in surround suppression

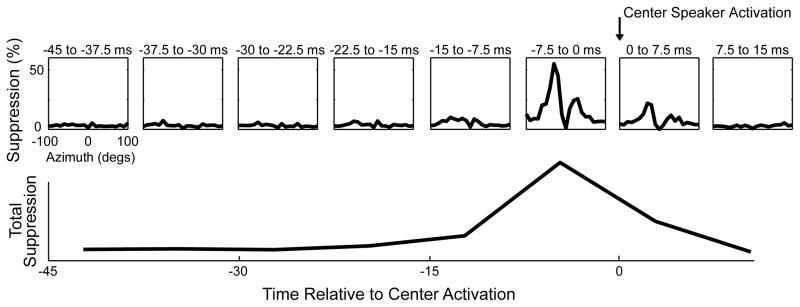

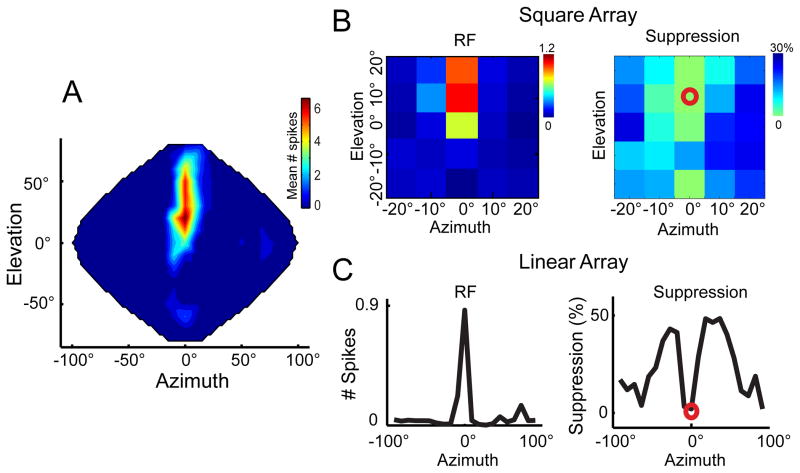

We examined the effect of activating the surround on the response to the preferred direction in ICx neurons (n = 91) using both a square and a linear array of speakers. Suppression was observed when surround speakers were activated 22.5ms before to 7.5ms after the onset of the center speaker (Figure 3). For the entire dataset, the most robust suppressive effect occurred when surround speakers were activated −7.5 to 0 ms before the center speaker. Suppression was significant from −15 to 0 ms before center activation; this time interval was thus used to analyze the surround effect. Surrounding speakers on both sides had a suppressive effect on the response at the center. However, surround suppression from the left and right sides showed differences. In the example shown in Figure 4, the right side of the RF was significantly more suppressive compared to the left side. The asymmetry was observed using both the square and linear arrays (Figure 4B, C). Because this particular neuron was recorded in ICx of the right hemisphere, frontal space is to the right of the center speaker. Thus, the stronger suppression on the right indicated that suppression from frontal space was stronger than suppression from the periphery.

Figure 3.

Magnitude of surround suppression at different latencies relative to the onset of sound at the center. Top, mean surround modulation (n = 91) varied with time, relative to the stimulus onset at the center speaker (arrow). Bottom, magnitude of surround suppression estimated by integrating the plots of the top row. Suppression was strongest when surround speakers were activated −7.5 to 0 ms prior to activation at the center.

Figure 4.

Asymmetrical surround suppression in ICx. A) Full spatial RF of an ICx neuron mapped using the entire speaker array (144 speakers). The neuron’s response peaks at 0° azimuth and 10° elevation. B) SWN analysis for the same cell using the square array. Left, spatial RF. Right, surround effect. The red circle indicates the RF center. Suppression is stronger from the right side, which for this particular cell represents frontal space. Calibration bars indicate number of spikes per stimulus (left) and percent suppression (right). C) The spatial RF (left) and surround effect (right) are shown for a wider range applying SWN with a linear array. Surround modulation is shown as percentage change from the mean response at the center. Similar to suppression in the square array, suppression from the right (frontal space) is greater than peripheral suppression.

Data were pooled across hemispheres to measure surround modulation from the front and the periphery. An estimate of the total amount of suppression received from each side was computed by integrating the surround effect to the left and to the right of the center speaker. Then, left and right sides were converted to front or periphery, depending on the hemisphere of the recording site. Across ICx, suppression from the front was significantly stronger for both the square (n = 78, t-test, p<0.01) and linear arrays (n = 91, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p<0.001).

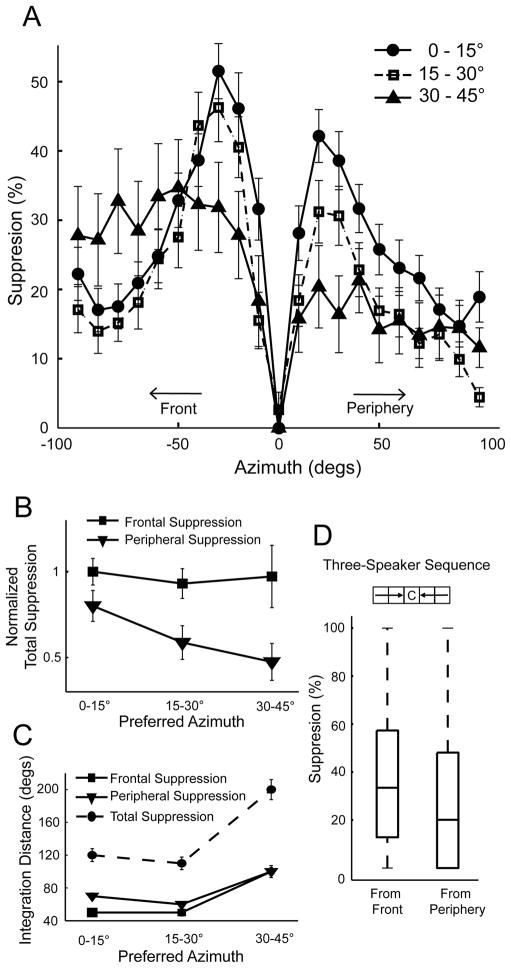

These effects were further characterized using the linear array, as it covers a greater distance in azimuth. These data showed that surround suppression was strongest in neurons tuned to frontal space (Figure 5A, circles) and decreased for cells tuned to more lateral locations (squares and triangles). Although lower in magnitude, the surround suppression in the most peripheral group spread over a greater distance from the center of the RF (triangles). While suppression from the front was greater than from the periphery in all three groups, this difference was significantly larger in the intermediate and lateral groups than in neurons tuned to frontal space. This was due to peripheral suppression decreasing more sharply with spatial tuning compared to frontal suppression (Figure 5B). In addition, the area of surround suppression was larger for more laterally-tuned neurons (Figure 5C). Neurons tuned to frontal space received the greatest suppression within 50° of the preferred azimuth. In the most lateral group, suppression extended throughout the entire range tested on both sides. The number of cells found with spatial tuning beyond 45° in azimuth was low in our sample and insufficient to be included in the surround analysis. This is presumably because the area of ICx representing locations far into the periphery is small and difficult to access (Knudsen and Konishi, 1978a; Knudsen, 1982).

Figure 5.

Population-wide SWN analysis. A) The surround effect was averaged across neurons for each group. Negative values in azimuth represent the frontal direction, relative to the RF’s center (0°). Suppression from the front was stronger than from the periphery in all groups. For frontal neurons (circles), suppression around the RF center was greater in amplitude but dropped off faster over azimuth. The most lateral group (triangles) showed lower magnitude in suppression but suppression extended over greater distance. B) Total frontal and peripheral suppression for each group, computed by integrating the curves in A and normalizing to the maximum. Suppression from the front (squares) was significantly stronger but relatively constant for all groups across the map. However, peripheral suppression (triangles) decreased with laterality in spatial tuning. C) Area of the surround as a function of spatial tuning. Surround suppression extended further for neurons tuned to lateral space compared to the frontal and intermediate groups (Kruskall-Wallis test, * p<0.05). Total suppression was greatest for the most laterally-tuned group. Error bars represent SEM. D) Surround suppression in 3-speaker sequences. The diagram shows activation of three consecutive speakers originating from the front or periphery and terminating at the center. The edges of the boxes are the 25th and 75th percentiles and the line in the middle represents the median. Sound sequences originating from frontal space were significantly more suppressive than sequences originating from peripheral space (Wilcoxon Sign Rank test p<0.05).

To further test the surround asymmetry, we examined longer speaker sequences from the SWN data for 78 neurons. The same method described above was used to calculate surround suppression for three-speaker sequences that originated from frontal or peripheral space and terminated at the center speaker. Speakers in each sequence were at the same elevation, spaced 10° in distance and 0–15ms in time between consecutive sounds. Stronger suppression from the front was also observed in these longer sequences (Figure 5D).

Model of surround suppression in ICx

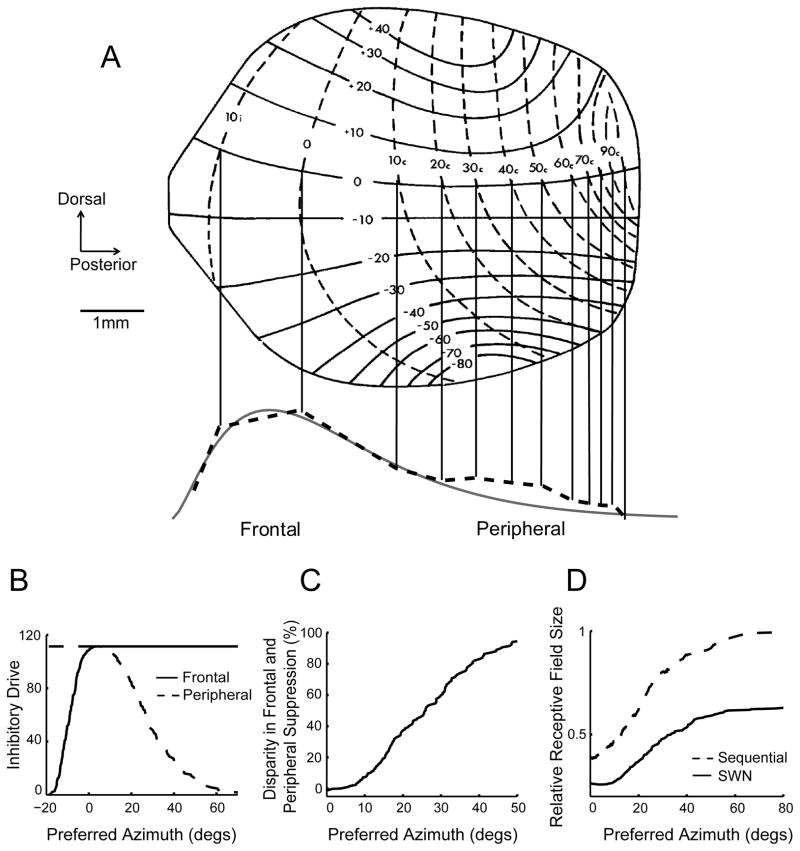

We designed a model of lateral inhibition in ICx to test whether the nonuniform representation of auditory space across the map can account for the observed bias in surround suppression. The distribution of spatial tunings in the model was represented by a transformed χ2 probability density function (see methods), where more cells were tuned to frontal than to peripheral space (Knudsen 1982; Figure 6A). The inhibitory weights of lateral connections varied as a function of anatomical distance, modeled by a Gaussian function of the difference between the anatomical positions of cells. This function was broad enough such that cells located at the center of the ICx map could interact with cells at the ends of the map. The broad surround suppression used in the model is consistent with our data (Figure 5A) and with previous reports (Knudsen and Konishi, 1978b).

Figure 6.

Model of the ICx and its predictions. A) The distribution of preferred azimuth is nonuniform, as shown by the spaces between vertical iso-tuning lines separated by 10° in azimuth (from Knudsen 1982). Nearly half of the map is dedicated to ± 20 degrees in azimuth, indicating that frontal space is overrepresented. The spacing between iso-tuning lines (bottom, dotted line) was used to estimate the population distribution. A transformed χ2 function (bottom, solid gray line) best approximates the distribution of preferred azimuth at 0° elevation on the map. B) The model shows frontal (solid line) and peripheral suppression (dashed line) as a function of spatial tuning. Frontal suppression increases with spatial tuning to overtake peripheral tuning near 5° in contralateral space. After reaching maximum, frontal suppression remains constant while suppression from the periphery decreases with laterality. Suppression from the periphery and the front approach zero near the ipsilateral and contralateral ends of the map, respectively. C) The model predicted that the bias in frontal suppression increased with spatial tuning. D) Relative RF sizes were estimated for partial surround activation in sequential stimulation (dashed line) and for the entire surround activation in SWN stimulation (solid line). The increase in RF size with laterality is greater with sequential stimulation.

The model yielded several predictions that were consistent with the data. First, it predicted the bias toward frontal surround suppression observed in cells tuned to peripheral space (Figure 5). The curves in Figure 6B represent the model’s estimates of frontal and peripheral suppression as a function of preferred azimuth. Neurons located at the ipsilateral edge of the map receive suppression predominantly from one side. Suppression from both sides became equal at the center of the overrepresented region near 0° (Figure 6A). From the point of intersection, suppression from the front remained constant while suppression from the periphery decreased. Thus for most of the map, suppression from the front exceeded suppression from the periphery. This prediction was consistent with the data such that for the recorded range, suppression from the front exceeded suppression from the periphery (Figure 5B).

The model also predicted that the difference between frontal and peripheral suppression would increase with laterality (Figure 6C). In other words, as cells became tuned to more peripheral space, the bias favoring surround suppression from the front became stronger. In the model, this increase in suppression bias was a function of the nonuniform distribution of spatial tuning. The overrepresentation of frontal space resulted in progressively greater suppression from the front due to an increasing number of cells exerting inhibition from this side of the receptive fields. Conversely, the decrease in strength of peripheral suppression with laterality was caused by the lower number of cells exerting inhibition from the peripheral side. The model results agree with the data, which show a laterality-dependent increase in the difference between frontal and peripheral suppression (Figure 5B).

In addition, the model predicted that the size of the RFs measured with sequential stimulation was larger than with SWN stimulation (Figure 2B). This effect resulted from sounds produced by single speakers activating only a portion of the surround whereas concurrent stimulation in SWN drives the entire surround. Spatial RFs during sequential stimulation were simulated by only activating the surround within 10° around the preferred azimuth of each cell. This value is within the range of the RF size in frontal ICx neurons. Neurons tuned to frontal space receive greater suppression from this portion of the surround due to the overrepresentation of frontal space. The sparser representation of peripheral space results in weaker suppression on laterally-tuned cells. Thus, assuming the size of the RF results from the interaction of excitatory and inhibitory drives (Kastner et al., 2001), the model suggests that frontal cells should have smaller RFs than laterally-tuned cells (Figure 6D). On the other hand, in the SWN condition, the number of cells activated in the surround varies less between the front and the periphery, resulting in more similar RF size across the population. These predictions are consistent with the data, which show that the difference in RF size between the sequential and SWN conditions is larger in the periphery (Figure 2C).

Thus theoretically, the nonuniform map of auditory space found in the ICx can explain the observed trends in surround suppression. For cells tuned to the front, surround suppression originates mainly from neurons selective for frontal directions because spatial tuning varies little over anatomical distance in this part of the map. In the periphery, cells receive weaker suppression from nearby cells because spatial tuning changed more rapidly in this part of the map. For the same reasons, surround suppression was broader in the periphery of the map. As a result of these tuning-dependent changes in surround-suppression, when the entire surround was activated by SWN, the total surround suppression from both sides increases with laterality. This may explain why SWN has a stronger effect on RF width in the periphery (Figure 2C).

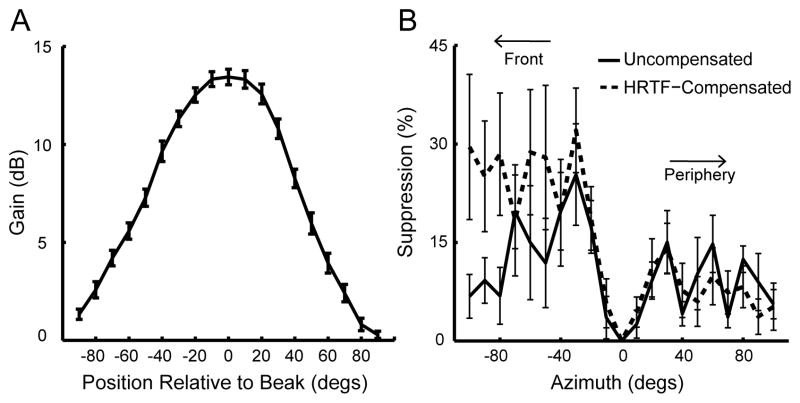

The HRTF and surround suppression

We considered the possibility that head-related transfer functions (HRTFs) made by the owl’s head were the source of asymmetries found in the RFs. The owl’s facial ruff consists of stiff feathers specialized to filter sound (Payne, 1971; Coles and Guppy, 1988; Nieder et al., 2003). Depending on frequency and direction, sounds are transformed by the facial ruff, ear canal, and surrounding structures in a manner that has been described as the owl’s HRTF (Keller et al., 1998; Nieder et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2003). HRTFs for 6 adult barn owls of both sexes were used for HRTF-compensated SWN stimuli. A generic HRTF at 0° elevation was calculated by averaging individual HRTFs across frequencies (1–10 kHz) and subjects. When sound intensity in every speaker in the array is set to be constant, the owl’s HRTF causes sounds that originate in frontal space to be louder at the eardrums. To test whether the surround suppression asymmetry is due to a sound-level bias induced by the HRTF, the SWN stimulation was adapted such that sound level was compensated for the HRTF. For SWN stimuli with HRTF compensation, attenuation was greatest (13 dB) at 0° azimuth relative to the beak and decreased to zero at 80° azimuth (Figure 7A). If the asymmetries observed in the RFs were due to intensity variations induced by the HRTF, we expected to abolish (or reduce) the asymmetry in the HRTF-compensated data. However, SWN analysis under such conditions (n = 10, from 2 owls of different sexes) showed no significant difference from the SWN data collected without compensation. The bias towards frontal suppression in the HRTF-compensated data was similar compared to uncompensated data (Figure 7B). Thus, the effects of HRTFs are not required for the bias in surround suppression.

Figure 7.

Surround suppression and the HRTF. A) Generic HRTF at 0° elevation obtained by averaging individual HRTFs across frequency from 6 owls. The function shows that sound intensity gain is greatest in front of the owl’s head and decreases with laterality. This curve was used to modify the output of the speaker array so that sounds from different locations should arrive at the eardrums with similar intensity. B) Surround effect as a function of distance from the RF center. For the same neurons, there was no significant difference between RFs measured with (dashed line) and without (solid line) compensating for the HRTF (Kruskal Wallis test, p>0.2). Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

This study shows an asymmetry in surround inhibition that can be adequately accounted for by the nonuniform distribution of preferred stimuli in a sensory map. Specifically, the topography and distribution of spatial tuning in ICx can explain a population-wide bias in surround modulation, favoring suppression from one side of the RF. This study was restricted to surround modulation in the horizontal plane, corresponding to a subset of the population of cells that constitute the map (Knudsen 1982). For technical reasons, the SWN analysis could not be performed in neurons unresponsive to elevations within ±10 degrees around the horizon. However, the spatial tuning of ICx cells is broader in elevation than in azimuth (Knudsen and Konishi 1978), thus the chance of driving cells with speakers near 0 degree elevation is increased. The frontal bias reported here is yet to be studied in elevation. Because there is also overrepresentation of frontal space in elevation (Knudsen, 1982), it is possible that the bias in surround suppression also occurs in this dimension.

There is evidence suggesting the presence of local (Fujita and Konishi, 1991) and lateral inhibition in ICx (Knudsen and Konishi 1978b). However, other mechanisms could contribute to the surround suppression described in this study. The attenuation of peripheral sounds did not account for the pattern of surround suppression described in this study. However, HRTFs could contribute to surround suppression in other ways. Simultaneous sounds at different locations may decrease binaural correlation between the two ears because sounds from different directions are transformed differently by HRTFs, even if the sounds were identical at the source (Coles and Guppy, 1988; Xing et al., 2011). Decreased binaural correlation is known to dampen the response of ICx cells (Albeck and Konishi, 1995; Saberi et al., 1998). Decorrelation may partially explain our observation that concurrent sounds from locations not known to be represented on the map (beyond 15° ipsilateral and 100° contralateral; Knudsen and Konishi, 1978, Knudsen, 1982) also had suppressive effects (Figure 5A). However, because SWN stimulation consists of a dense auditory scene with random activation of speakers from multiple directions, suppression due to decorrelation is expected to be, on average, space-independent, once stimulus amplitude is corrected for the HRTF. In addition, lateral inhibition could take place in upstream nuclei to ICx, provided frontal space is overrepresented in these regions.

Surround suppression bias in the model of ICx resulted primarily from the nonuniform representation of space. However, because the number of cells in the surround was bilaterally unequal for neurons located at the edges of map, an ‘edge effect’ also contributes to the bias. It is possible to distinguish bias caused by the population distribution and that caused by the edge effect by studying the intercept of frontal and peripheral suppression in Figure 6B. If the edge effect were the dominant factor in the balance between frontal and peripheral suppression, the intercept should occur at the midpoint of the ICx map (approximately 30° on the contralateral space), i.e., changes in frontal and peripheral suppression should be symmetrical across the population. However, the model and the data indicated that the frontal bias started closer to the front. These observations support the notion that suppression bias is caused by the uneven tuning distribution in ICx.

Nonuniform topographic representations are not unique to the owl’s ICx and OT. The superior colliculus in mammals possesses a topographic representation of both visual and auditory space, where frontal space overrepresentation has been observed in numerous species (Drager and Hubel, 1976; Doubell et al., 2000). The visual and somatosensory cortices also show overrepresentation of the foveal region (Yang et al., 1992; Kautz and Wagner, 1998; Zhang et al., 1999) and the face and hands (Penfield and Boldrey, 1937; Fujita and Konishi, 1991), respectively. Given that lateral inhibition has been demonstrated in several sensory areas (Ruderman and Bialek, 1994; Cavanaugh et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2011), the nonuniform topography of neural tunings in brain maps is a likely ubiquitous source of population-wide biases in the brain (Schwartz, 1980). The RF bias described in this study can theoretically originate at any point in the auditory pathway where there is an overrepresentation of frontal space. ICx is the earliest nucleus where a nonuniform distribution has been unequivocally shown through mapping. Upstream to ICx, azimuth representation appears uniform in the core of the IC (ICc) (Wagner et al., 1987) and, to our knowledge, these properties have not been explored in the intermediate nucleus between ICc and ICx. Although demonstration of the exact location of the surround bias is pending, it appears likely that a significant part of it emerges within the owl’s midbrain.

In the visual and somatosensory systems, local computation involving asymmetric surround inhibition can induce orientation and motion selectivity (Hubel and Wiesel, 1962; Walker et al., 1999; DiCarlo and Johnson, 2002; Tailby et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011). In the primary auditory cortex, direction selectivity to FM sweeps varies with characteristic frequency, suggesting the asymmetry of inhibitory sidebands is the source of direction selectivity (Zhang et al., 2003). In the owl’s inferior colliculus and optic tectum, direction selectivity for sequential activation in linear arrays of speakers has been observed (Wagner and Takahashi, 1992; Wagner et al., 1994, Witten et al., 2006). Kautz and Wagner (1998) showed that direction selectivity could be partially abolished by blocking GABA-mediated inhibition, suggesting local inhibition is present in ICx.

The asymmetric surround suppression described here may underlie direction selectivity. Our results suggest that direction sensitivity could be more widespread in ICx than previously reported because asymmetry in surround inhibition was observed in a majority of the cells. Furthermore, our work suggests that direction selectivity should be represented on both hemispheres in a mirror-like manner, i.e., the two hemispheres should prefer sounds moving in opposite directions. It remains to be shown how the RF asymmetry corresponds with changes in firing rates with moving sounds.

The surround suppression elicited under SWN could also have implications for extracting signals from noise in complex auditory scenes (Geisler, 2008; Burge et al., 2010; Moorthy and Bovik, 2011; Teki et al., 2011); (Burr et al., 1981; Leventhal et al., 2003). RFs with SWN stimulation were narrower compared with sequential stimulation mainly for laterally-tuned cells. However, sharpening could be global even though we did not find an effect of SWN on the size of RFs in frontal space. The 10° speaker array resolution used in this study may be too coarse to reveal RF sharpening in cells tuned to frontal space. In addition, it has been shown that sound level has an effect on the size of spatial receptive fields (Knudsen and Konishi 1978c). Because the sound reaching each ear during SWN stimulation results from a large number of speaker permutations, the average sound level could be different from stimulation with a single speaker at a time. Thus comparing both conditions carries uncertainty unless the complex center-surround interactions during SWN are taken into account.

The proposed model could account for the RF sharpening with SWN and the stronger surround suppression from frontal space. ICx represents mostly frontal and contralateral space such that neurons receive unequal modulation across the nucleus. The model predicted (1) the RF sharpening with SWN due to broader activation of the surround, (2) the stronger frontal suppression and (3) the dependence of the bias on the spatial tuning, where the bias would increase in more laterally-tuned neurons. The data matched these predictions. Thus, a model of local lateral inhibition in a nonuniform map of space can represent the data.

Isomorphic representations allow local connections among neurons to preserve the spatial relationships present in the environment. This study showed that nonuniformity within a map can bias the strength of local connections, allowing for an organized representation of higher-order stimulus features to emerge. This may be the case for the hemispheric asymmetries in response to moving auditory stimuli observed in human subjects (Getzmann, 2011). These computations are likely present in other sensory systems and could play a role in processing complex stimuli in natural environments.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Terry Takahashi and Kip Keller for their suggestions and insights and to Michael Beckert and Louisa Steinberg for comments on the manuscript. We especially thank Dr. Keller for providing owls’ HRTF data for our reference.

Grant support: This work was supported by grants from the NIDCD (DC007690) to JLP and NRSA (F31DC012000) to YW.

References

- Albeck Y, Konishi M. Responses of neurons in the auditory pathway of the barn owl to partially correlated binaural signals. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1689–1700. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge J, Fowlkes CC, Banks MS. Natural-scene statistics predict how the figure-ground cue of convexity affects human depth perception. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7269–7280. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5551-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr D, Morrone C, Maffei L. Intra-cortical inhibition prevents simple cells from responding to textured visual patterns. Exp Brain Res. 1981;43:455–458. doi: 10.1007/BF00238391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh JR, Bair W, Movshon JA. Selectivity and spatial distribution of signals from the receptive field surround in macaque V1 neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2547–2556. doi: 10.1152/jn.00693.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Geisler WS, Seidemann E. Optimal decoding of correlated neural population responses in the primate visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1412–1420. doi: 10.1038/nn1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichilnisky EJ. A simple white noise analysis of neuronal light responses. Network. 2001;12:199–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles RB, Guppy A. Directional hearing in the barn owl (Tyto alba) J Comp Physiol A. 1988;163:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00612002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo JJ, Johnson KO. Receptive field structure in cortical area 3b of the alert monkey. Behav Brain Res. 2002;135:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubell TP, Baron J, Skaliora I, King AJ. Topographical projection from the superior colliculus to the nucleus of the brachium of the inferior colliculus in the ferret: convergence of visual and auditory information. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4290–4308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager UC, Hubel DH. Topography of visual and somatosensory projections to mouse superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:91–101. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE, Knudsen EI. An anatomical basis for visual calibration of the auditory space map in the barn owl’s midbrain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17:6820–6837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firbank MJ, Coulthard A, Harrison RM, Williams ED. A comparison of two methods for measuring the signal to noise ratio on MR images. Physics in medicine and biology. 1999;44:N261–264. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/12/403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BJ, Pena JL. Owl’s behavior and neural representation predicted by Bayesian inference. Nat Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nn.2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foeller E, Celikel T, Feldman DE. Inhibitory sharpening of receptive fields contributes to whisker map plasticity in rat somatosensory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4387–4400. doi: 10.1152/jn.00553.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucke T, Suchanek D, Nawrot MP, Seamari Y, Heck DH, Aertsen A, Boucsein C. Stereotypic spatio-temporal activity patterns during slow-wave activity in the neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/jn.00811.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita I, Konishi M. The role of GABAergic inhibition in processing of interaural time difference in the owl’s auditory system. J Neurosci. 1991;11:722–739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00722.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler WS. Visual perception and the statistical properties of natural scenes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:167–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getzmann S. Auditory motion perception: onset position and motion direction are encoded in discrete processing stages. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1339–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. J Physiol. 1962;160:106–154. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive Fields and Functional Architecture in Two Nonstriate Visual Areas (18 and 19) of the Cat. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28:229–289. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Uniformity of monkey striate cortex: a parallel relationship between field size, scatter, and magnification factor. J Comp Neurol. 1974;158:295–305. doi: 10.1002/cne.901580305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde PS, Knudsen EI. Topographic projection from the optic tectum to the auditory space map in the inferior colliculus of the barn owl. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:146–160. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000529)421:2<146::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenison RL, Schnupp JW, Reale RA, Brugge JF. Auditory space-time receptive field dynamics revealed by spherical white-noise analysis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4408–4415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04408.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JP, Palmer LA. An evaluation of the two-dimensional Gabor filter model of simple receptive fields in cat striate cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1987;58:1233–1258. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.58.6.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. Topographic maps are fundamental to sensory processing. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44:107–112. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal JS, Fitzpatrick DC, Suga N. Facilitatory and inhibitory frequency tuning of combination-sensitive neurons in the primary auditory cortex of mustached bats. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2327–2345. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, De Weerd P, Pinsk MA, Elizondo MI, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG. Modulation of sensory suppression: implications for receptive field sizes in the human visual cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1398–1411. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.3.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz D, Wagner H. GABAergic inhibition influences auditory motion-direction sensitivity in barn owls. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:172–185. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller CH, Takahashi TT. Binaural cross-correlation predicts the responses of neurons in the owl’s auditory space map under conditions simulating summing localization. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4300–4309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller CH, Hartung K, Takahashi TT. Head-related transfer functions of the barn owl: measurement and neural responses. Hearing research. 1998;118:13–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AJ. Sensory experience and the formation of a computational map of auditory space in the brain. Bioessays. 1999;21:900–911. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199911)21:11<900::AID-BIES2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI. Auditory and visual maps of space in the optic tectum of the owl. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1177–1194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-09-01177.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI. Subdivisions of the inferior colliculus in the barn owl (Tyto alba) J Comp Neurol. 1983;218:174–186. doi: 10.1002/cne.902180205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI. Auditory properties of space-tuned units in owl’s optic tectum. J Neurophysiol. 1984;52:709–723. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Konishi M. A neural map of auditory space in the owl. Science. 1978a;200:795–797. doi: 10.1126/science.644324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Konishi M. Center-surround organization of auditory receptive fields in the owl. Science. 1978b;202:778–780. doi: 10.1126/science.715444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Knudsen PF. Space-mapped auditory projections from the inferior colliculus to the optic tectum in the barn owl (Tyto alba) J Comp Neurol. 1983;218:187–196. doi: 10.1002/cne.902180206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Konishi M, Pettigrew JD. Receptive fields of auditory neurons in the owl. Science. 1977;198:1278–1280. doi: 10.1126/science.929202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer Y, Leger JF, Goodman D, Brette R, Bourdieu L. Late emergence of the vibrissa direction selectivity map in the rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10689–10700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6541-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavallee P, Deschenes M. Dendroarchitecture and lateral inhibition in thalamic barreloids. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6098–6105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0973-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AG, Wang Y, Pu M, Zhou Y, Ma Y. GABA and its agonists improved visual cortical function in senescent monkeys. Science. 2003;300:812–815. doi: 10.1126/science.1082874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BH, Li YT, Ma WP, Pan CJ, Zhang LI, Tao HW. Broad inhibition sharpens orientation selectivity by expanding input dynamic range in mouse simple cells. Neuron. 2011;71:542–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Suga N. Lateral inhibition for center-surround reorganization of the frequency map of bat auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3192–3199. doi: 10.1152/jn.00301.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarelis PZ, Naka K. White-noise analysis of a neuron chain: an application of the Wiener theory. Science. 1972;175:1276–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4027.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarelis PZ, McCann GD. Development and application of white-noise modeling techniques for studies of insect visual nervous system. Kybernetik. 1973;12:74–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00272463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseff A. Bi-coordinate sound localization by the barn owl. J Comp Physiol A. 1989;164:637–644. doi: 10.1007/BF00614506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseff A, Konishi M. Binaural characteristics of units in the owl’s brainstem auditory pathway: precursors of restricted spatial receptive fields. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2553–2562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02553.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CI, Nelson SB, Sur M. Dynamics of neuronal processing in rat somatosensory cortex. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:513–520. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01452-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy A, Bovik A. Blind Image Quality Assessment: From NaturalScene Statistics to Perceptual Quality. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2011 doi: 10.1109/TIP.2011.2147325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieder B, Wagner H, Luksch H. Development of output connections from the inferior colliculus to the optic tectum in barn owls. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:511–524. doi: 10.1002/cne.10827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne RS. Acoustic location of prey by barn owls (Tyto alba) J Exp Biol. 1971;54:535–573. doi: 10.1242/jeb.54.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Boldrey E. Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain. 1937;60:389–443. [Google Scholar]

- Perez ML, Shanbhag SJ, Pena JL. Auditory spatial tuning at the crossroads of the midbrain and forebrain. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:1472–1482. doi: 10.1152/jn.00400.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienkowski M, Eggermont JJ. Cortical tonotopic map plasticity and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak GD, Bodenhamer RD. Specialized characteristics of single units in inferior colliculus of mustache bat: frequency representation, tuning, and discharge patterns. J Neurophysiol. 1981;46:605–620. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.46.3.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portfors CV, Roberts PD, Jonson K. Over-representation of species-specific vocalizations in the awake mouse inferior colliculus. Neuroscience. 2009;162:486–500. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevedo C, Hoffmann KP, Husemann R, Distler C. Overrepresentation of the central visual field in the superior colliculus of the pigmented and albino ferret. Vis Neurosci. 1996;13:627–638. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800008531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio-Spinoso A, Temchin AN, van Dijk P, Fan YH, Ruggero MA. Wiener-kernel analysis of responses to noise of chinchilla auditory-nerve fibers. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:3615–3634. doi: 10.1152/jn.00882.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rübsamen R, Neuweiler G, Sripathi K. Comparative collicular tonotopy in two bat species adapted to movement detection. Journal of Comparative Physiology. 1988;163:217–285. [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman DL, Bialek W. Statistics of natural images: Scaling in the woods. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;73:814–817. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi K, Takahashi Y, Konishi M, Albeck Y, Arthur BJ, Farahbod H. Effects of interaural decorrelation on neural and behavioral detection of spatial cues. Neuron. 1998;21:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sceniak MP, Ringach DL, Hawken MJ, Shapley R. Contrast’s effect on spatial summation by macaque V1 neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:733–739. doi: 10.1038/11197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz EL. Computational anatomy and functional architecture of striate cortex: a spatial mapping approach to perceptual coding. Vision Res. 1980;20:645–669. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(80)90090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailby C, Dobbie WJ, Solomon SG, Szmajda BA, Hashemi-Nezhad M, Forte JD, Martin PR. Receptive field asymmetries produce color-dependent direction selectivity in primate lateral geniculate nucleus. J Vis. 2010;10:1. doi: 10.1167/10.8.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Moiseff A, Konishi M. Time and intensity cues are processed independently in the auditory system of the owl. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1781–1786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01781.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teki S, Chait M, Kumar S, von Kriegstein K, Griffiths TD. Brain bases for auditory stimulus-driven figure-ground segregation. J Neurosci. 2011;31:164–171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3788-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui JM, Hunter JN, Born RT, Pack CC. The role of V1 surround suppression in MT motion integration. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:3123–3138. doi: 10.1152/jn.00654.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Takahashi T. Influence of temporal cues on acoustic motion-direction sensitivity of auditory neurons in the owl. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:2063–2076. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Takahashi T, Konishi M. Representation of interaural time difference in the central nucleus of the barn owl’s inferior colliculus. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3105–3116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03105.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Trinath T, Kautz D. Influence of stimulus level on acoustic motion-direction sensitivity in barn owl midbrain neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1907–1916. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.5.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Gunturkun O, Nieder B. Anatomical markers for the subdivisions of the barn owl’s inferior-collicular complex and adjacent peri- and subventricular structures. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:145–159. doi: 10.1002/cne.10826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker GA, Ohzawa I, Freeman RD. Asymmetric suppression outside the classical receptive field of the visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10536–10553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10536.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Sarnaik R, Rangarajan K, Liu X, Cang J. Visual receptive field properties of neurons in the superficial superior colliculus of the mouse. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16573–16584. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3305-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten IB, Bergan JF, Knudsen EI. Dynamic shifts in the owl’s auditory space map predict moving sound location. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1439–1445. doi: 10.1038/nn1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Tiesinga PH, Tucker TR, Mitroff SR, Fitzpatrick D. Dynamics of population response to changes of motion direction in primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12767–12777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4307-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing D, Ringach DL, Hawken MJ, Shapley RM. Untuned suppression makes a major contribution to the enhancement of orientation selectivity in macaque v1. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15972–15982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2245-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Pollak GD, Resler C. GABAergic circuits sharpen tuning curves and modify response properties in the mustache bat inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:1760–1774. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.5.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Xu J, Feng AS. Effects of GABA-mediated inhibition on direction-dependent frequency tuning in the frog inferior colliculus. J Comp Physiol A. 1999;184:85–98. doi: 10.1007/s003590050308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LI, Tan AY, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Topography and synaptic shaping of direction selectivity in primary auditory cortex. Nature. 2003;424:201–205. doi: 10.1038/nature01796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Green DM, Middlebrooks JC. Characterization of external ear impulse responses using Golay codes. J Acoust Soc Am. 1992;92:1169–1171. doi: 10.1121/1.404045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]