Abstract

Prevalent hypertension in National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) is traditionally defined as blood pressure (BP) ≥140 mmHg systolic and/or ≥90 diastolic and/or currently taking antihypertensive medications. When estimating prevalent hypertension, American Heart Association (AHA) statistical updates include the traditional definition of hypertension (tHTN) and untreated individuals with non-hypertensive BP twice told they were hypertensive (non-traditional [ntHTN]). The characteristics of ntHTN and their impact on the clinical epidemiology of hypertension and Healthy People prevention and control goals are undefined. NHANES 1999–2002, 2003–2006, and 2007–2010 were analyzed. The ntHTN group was younger and had less diabetes and lower BP than tHTN but higher BP than normotensives. When classifying ntHTN as hypertensive, prevalent hypertension increased ~3% and control 5–6% across NHANES periods. In 2007–2010, the Healthy People 2010 goal of controlling BP in 50% of all hypertensives was attained when ntHTN where classified as hypertensive (56.5% [95% confidence interval, 54.2–58.7]) and non-hypertensive (51.8% [49.6–53.9]). When including ntHTN in prevalent hypertension estimates, the Healthy People 2020 goal of controlling BP in 60% of hypertensive patients becomes more attainable, whereas reducing prevalent hypertension to 26.9% (31.8% [30.5–33.1]) vs. 28.7% [27.5–30.0]) becomes more challenging.

Keywords: twice-told hypertensive, hypertension, prevalence, awareness, treatment, control, Healthy People

Introduction

Hypertension is a prevalent risk factor for cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease as well as premature disability and death.1 U.S. Healthy People goals for hypertension prevention and control further attest to the public health importance of this diagnosis.2,3 Temporal trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension are of major public health importance and an indirect measure of the effectiveness of healthcare policy and delivery in attaining key public health objectives.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data for 1988–1994 and 1999–2008 demonstrated that hypertension awareness, treatment, and control all increased significantly over time.4 Hypertension control to blood pressure (BP) <140/<90 mmHg rose from an estimated 23.7% of all hypertensive patients in 1988–1994 to 50.1% in 2007–2008,4 which met the Healthy People 2010 goal of controlling BP in 50% of all hypertensive patients.2 In contrast, prevalent hypertension rose from 25.4% in 1988–1994 to 29.0% in 2007–2008, which rendered the goal of reducing prevalent hypertension to 16.0% by 2010 essentially unattainable.

Healthy People 2020 goals include reducing prevalent hypertension to 26.9% or roughly 10% from current levels.3 Moreover, the hypertension control goal for all hypertensive patients, which includes unaware and untreated patients, was raised from 50% in 2010 to 60% in 2020. Definitions of hypertension prevalence and control are of fundamental importance in assessing progress toward Healthy People BP objectives.

Traditionally, prevalent hypertension (tHTN) in NHANES is defined by BP ≥140 systolic and/or ≥90 mmHg diastolic and/or by patients affirming they are currentlyo taking prescribed medication to lower BP?”4–7 NHANES reports from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and American Heart Association annual statistical update8–10 also included as hypertensive untreated individuals with non-hypertensive BP twice told by a physician they had hypertension, i.e., non-traditional hypertension (ntHTN).

Clinical characteristics of individuals with ntHTN and their impact the clinical epidemiology of hypertension in the United States and Healthy People goals have not been systematically quantified. Thus, the three main objectives of this report are to: (a) describe clinical characteristics of ntHTN and to define their impact on the (b) clinical epidemiology of hypertension and (c) Healthy People goals. The report also assesses the mpact of defining hypertension control as <140/<90 mmHg for all patients rather than <140/<90 in patients without and <130/<80 in patients with diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease.

Methods

NHANES 1999–2010 were conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).7,11 NHANES volunteers were selected using stratified, multistage probability sampling of the non-institutionalized U.S. population. All adults provided written informed consent approved by the NCHS Institutional/Ethics Review Board.7

Definitions

Race/ethnicity was determined by self report and separated into non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic black (black), Hispanic ethnicity of any race as described.4,5 The numbers and percentages of individuals of other races including American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander and other race not specified were relatively small and categorized as ‘Other’.

Height and weight were measured without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, i.e., kg/m2.

Blood pressure (BP) was measured with the same methods across NHANES 1999–2010.4,11 In brief, trained physicians measured BP using a mercury sphygmomanometer and appropriately sized arm cuff on subjects after five minutes seated rest. Individuals without recorded BP values were excluded. Mean systolic and diastolic BP were determined as recommended in NHANES reporting guidelines. The majority of patients had three recorded BP values, and the mean of the second and third values was used in analyses. For individuals with two recorded BP values, the second BP alone was used. For individuals with one BP measurement, the single value was used. In all survey periods, >90% of subjects had ≥2 BP measurements.

Hypertension was defined as mean systolic BP ≥140 and/or mean diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg and/or a positive response to the question “Are you currently taking medication to lower your BP?”4–7,12 Untreated individuals with blood pressure <140/<90 mmHg who reportedly were told twice by a physician that they were hypertensive (non-traditionl hypertension [ntHTN]) were also designated as hypertensive in some analyses.8–10

Awareness of hypertension was determined by hypertensive patients answering ‘Yes’ to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other healthcare professional that you had hypertension, also called high BP?”4–7

Treatment of hypertension was defined by subjects responding “Yes” to the question, “Because of your hypertension/high BP are you now taking prescribed medicine?”4–7,12

Control of hypertension was defined as BP <140/<90 mmHg across all survey periods, although the BP goals for high risk subgroups including diabetics was lower for 1999–2010.1,13 Recent evidence does not clearly support a goal systolic BP <140 for diabetic patients or those with non-proteinuric hypertensive renal disease.14,15 For these reasons and to facilitate comparisons across the three NHANES study periods, this report focuses primarily on goal BP <140/<90 mmHg for all hypertensive patients. To address the secondary study objective, differences in BP control rates between the goal of <140/<90 for all patients and <140/<90 for patients without and <130/<80 for patients with diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease are reported.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/1.7 m2/min and/or urine albumin:creatinine ≥300 mg/g.16,17 Serum creatinine values were adjusted to facilitate comparisons of eGFR across surveys.18

Diabetes mellitus was defined by a positive response to “Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have diabetes?” and/or “Are you now taking insulin?” and/or “Are you now taking diabetes pills to lower your blood sugar?” The definition did not include patients with only fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL, i.e. “undiagnosed diabetes”.19,20

Data analysis

The NHANES Analytic and Reporting Guidelines were followed. SAS callable SUDAAN version 10.0.1 (Cary, NC) was used for all analyses to account for the complex NHANES sampling design. Standard errors were estimated using Taylor series linearization. To compare prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates across surveys, age-adjustment to the U.S. 2000 census data was performed on all NHANES periods in SUDAAN DESCRIPT procedure. For Tables 1 and 2, the CROSSTAB procedure was used for categorical variables; DESCRIPT procedure was used for continuous variables. Pair-wise comparisons between the three NHANES periods were conducted using t-tests of weighted means and z-tests of weighted proportions with the weight equal to the standard errors estimated from the above-mentioned SUDAAN procedures. Since multiple statistical comparisons were performed among the three NHANES time periods, two sided p-values <0.01 were accepted as statistically significant. P-values <0.05 were accepted as significant when two groups were compared.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of all adult subjects who had BP measured in three NHANES time periods.

| NHANES | 1999–2002 | 2003–2006 | 2007–2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10,006 | 9,930 | 11,723 |

| Age, yrs | |||

| Mean | 44.1 (43.5, 44.8) | 45.2 (44.2, 46.2) | 46.0 (45.4, 46.7) ‡ |

| Gender | |||

| Male,% | 48.4 (47.4, 49.3) | 48.6 (47.6, 49.5) | 48.5 (47.7, 49.3) |

| Female, % | 51.6 (50.7, 52.6) | 51.4 (50.5, 52.4) | 51.5 (50.7, 52.3) |

| Race | |||

| White, % | 71.0 (67.2, 74.6) | 72.2 (67.6, 76.4) | 68.8 (63.5, 73.6) |

| Black, % | 10.5 (8.4, 13.2) | 11.1 (8.7, 14.1) | 11.3 (9.3, 13.7) |

| Hispanic, % | 13.8 (10.2, 18.4) | 11.4 (9.0, 14.5) | 13.7 (10.4, 17.8) |

| Other Race, % | 4.6 (3.5, 6.1) | 5.2 (4.3, 6.2) | 6.2 (5.0, 7.7) |

| SBP, mmHg | |||

| All subjects | 122.1 (121.3, 123.0) | 121.9 (121.2, 122.6)‡ | 120.4 (119.8, 121.0)‡ |

| DBP, mmHg | |||

| All subjects | 72.3 (71.7, 72.9) ‡ | 70.5 (70.0, 71.0) | 69.9 (69.1, 70.7) ‡ |

| ≥160/≥100, % | 5.3 (4.6, 6.1) | 4.7 (4.2, 5.3) ‡ | 3.2 (2.9, 3.5) ‡ |

| 140–159/90–99, % | 12.7 (11.8, 13.6) | 12.0 (10.9, 13.1) | 11.2 (10.4, 12.0) † |

| 120–139/80–89, % | 36.3 (35.0, 37.6) | 36.1 (34.8, 37.5) | 35.0 (33.5, 36.5) |

| <120/<80, % | 45.7 (43.8, 47.7) | 47.2 (45.4, 49.0) † | 50.7 (48.9, 52.4) ‡ |

| SBP, mmHg | |||

| Non-Hypertensive | 114.8 (114.2, 115.5) | 115.1 (114.6, 115.5) | 114.5 (113.9, 115.0) |

| DBP, mmHg | |||

| Non-Hypertensive | 70.4 (69.9, 70.9) ‡ | 68.6 (68.2, 69.0) | 68.6 (67.9, 69.4) ‡ |

| 120–139/80–89, % | 41.4 (39.5, 43.4) | 39.5 (37.4, 41.6) | 36.9 (35.0, 38.9) ‡ |

| <120/<80, % | 58.6 (56.6, 60.5) | 60.5 (58.4, 62.6 | 63.1 (61.1, 65.0) ‡ |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| Mean | 27.8 (27.6, 28.1) | 28.2 (27.9, 28.5) | 28.5 (28.3, 28.7) ‡ |

| <25.0 | 36.5 (34.6, 38.3) | 34.3 (32.5, 36.1) | 32.3 (30.7, 33.9) ‡ |

| 25.0–29.9 | 34.0 (32.4, 35.7) | 33.3 (31.9, 34.8) | 33.4 (32.2, 34.7) |

| 30, % | 29.5 (27.7, 31.4) | 32.4 (30.4, 34.4) | 34.3 (32.9, 35.8) ‡ |

| Diabetes, % | 6.2 (5.5, 6.9) † | 7.3 (6.6, 8.1) † | 8.9 (8.1, 9.7) ‡ |

| CKD, % | 5.6 (5.1, 6.1) | 6.0 (5.3, 6.8) | 6.1 (5.5, 6.8) |

Abbreviations: S=systolic; D=diastolic; BP=blood pressure, BMI=body mass index; CKD=chronic kidney disease (estimated GFR <60 ml/1.7m2/min).

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Symbols on column (a) 1999–2002 indicate p-value vs. 2003–2006 (b) 2003–2006 vs. 2007–2010 and (c) 2007–2010 vs. 1999–2002

Table 2.

Characteristics of ‘traditional’ and untreated twice told ‘hypertensives with non-hypertensive BP in three NHANES time periods.

| NHANES Time Period | 1999 – 2002 | 2003 – 2006 | 2007 – 2010 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | tHTN | ntHTN | tHTN | ntHTN | tHTN | ntHTN |

| Number, % (of all adults) | 3,150, 26.9 | 262, 2.8 | 3,107, 29.0 | 299, 3.1 | 4,150, 28.7 | 355, 2.9 |

| Age, yrs | 58.4 (57.3, 59.5) | 41.9 (40.1, 43.8) | 58.9 (57.5, 60.3) | 43.1 (41.0, 45.1) | 59.4 (58.8, 60.0) | 43.6 (41.8, 45.5) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male,% | 46.4 (44.3, 48.6) | 49.0 (41.3, 56.7) | 48.9 (46.9, 51) | 49.9 (40.7, 59.1) | 48.3 (46.6, 49.9) | 46.7 (40.3, 53.1) |

| Female, % | 53.6 (51.4, 55.7) | 51.0 (43.3, 58.7) | 51.1 (49.0, 53.1) | 50.1 (40.9, 59.3) | 51.7 (50.1, 53.4) | 53.3 (46.9, 59.7) |

| Race | ||||||

| White, % | 73.1 (68.5, 77.2) | 72.4 (65.5, 78.4) | 74.9 (69.6, 79.6) | 76.4 (70.0, 81.8) | 72.3 (66.4, 77.6) | 66.3 (58.7, 73.1) |

| Black, % | 13.3 (10, 17.5) | 10.9 (7.1, 16.4) | 13.7 (10.5, 17.7) | 8.5 (5.6, 12.6) | 14.3 (11.1, 18.1) | 14.1 (10.5, 18.7) |

| Hispanic, % | 9.7 (6.2, 14.9) | 11.5 (8.2, 15.9) | 6.8 (4.5, 10.0) | 10.1 (7.1, 14.0) | 8.8 (6.1, 12.6) | 11.8 (8.2, 16.8) |

| Other Race, % | 3.9 (2.5, 5.8) | 5.3 (2.4, 11.2) | 4.6 (3.5, 6.0) | 5.1 (2.6, 9.5) | 4.6 (3.3, 6.3) | 7.7 (4.8, 12.2) |

| SBP, mmHg | 141.9‡ (140.7, 143.2) | 122.3 (120.1, 124.4) | 138.6 ‡ (137.6, 139.6) | 120.6 (118.8, 122.5) | 134.4‡ (133.7, 135.2) | 120.6 (119.2, 121.9) |

| DBP, mmHg | 77.5‡ (76.6, 78.4) | 74.1 (72.5, 75.6) | 75.0 (74.0, 76.1) † | 71.7 (70.0, 73.4) | 72.9 (71.9, 73.9)‡ | 71.7 (70.3, 73.0) |

| BP Category | ||||||

| Stage 2 | ||||||

| ≥160/≥100, % | 19.7 (17.3, 22.3) † | 16.1 (14.4, 18.1) ‡ | 10.6 (9.5, 11.8)‡ | |||

| Stage 1 | ||||||

| 140–159/90–99, % | 47.1 (45.1, 49.0) ‡ | 41.1 (38.4, 43.9) | 37.4 (35.2, 39.6)‡ | |||

| Pre-HTN | ||||||

| 120–139/80–89, % | 22.5 (20.3, 24.9) ‡ | 69.9 (63.0, 76.0) | 27.9 (25.8, 30.1) | 61.7 (54.5, 68.3) | 30.5 (28.7, 32.5)‡ | 63.0 (57.1, 68.6) |

| Normal | ||||||

| <120/<80, % | 10.7 (9.3, 12.3) ‡ | 30.1 (24.0, 37.0) | 14.8 (13.2, 16.6) ‡ | 38.3 (31.7, 45.5) | 21.5 (19.8, 23.2)‡ | 37.0 (31.4, 42.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||||

| Mean | 30.1 (29.7, 30.5) | 29.8 (28.8, 30.9) | 30.3 (29.9, 30.6) † | 29.1 (28.1, 30.1) | 30.9 (30.7, 31.2)‡ | 30.3 (29.4, 31.3) |

| <25, % | 21.2 (19.4, 23.2) | 25.7 (19.9, 32.5) | 21.0 (19.2, 22.9) | 32.9 † (26.8, 39.7) | 19.0 (17.3, 20.8) | 20.5 (14.7, 27.7) |

| ≥30, % | 43.5 (41.2, 46.0) | 40.9 (33.4, 48.8) | 44.8 (42.4, 47.3) † | 38.6 (30.7, 47.1) | 48.8 (46.8, 50.8)‡ | 47.2 (40.7, 53.8) |

| Diabetes, % | 14.0 (12.8, 15.3) † | 8.1 (5.2, 12.3) | 16.6 (15.4, 17.7) ‡ | 9.1 (5.8, 14.2) | 20.5 (18.6, 22.5)‡ | 6.6 (4.6, 9.4) |

| CKD, % | 15.1 (13.7, 16.6) | 6.1 (2.7, 13.3) | 15.1 (13.1, 17.3) | 4.8 (2.6, 8.5) | 15.0 (13.8, 16.4) | 3.6 (1.9, 6.7) |

tHTN= ‘traditional’ hypertensive defined by BP ≥140/≥90 or non-hypertensive BP and self-report of prescribed medication treatment for hypertension

p<0.01;

p<0.001

The symbols on the column 1999–2002 indicate the p-value for comparison with 2003–2006 within tHTN or u2tHT-NHT group

The symbols on the column 2003–2006 indicate the p value for comparison with 2007–2010 within tHTN or u2tHT-NHT group

The symbols on the column 2007–2010 indicate the p value for comparison with 1999–2002 within tHTN or u2tHT-NHT group

Bold values in the u2tHT-NHT column indicate significant difference vs tHTN in same time period by non-overlapping 95% confidence limits.

Results

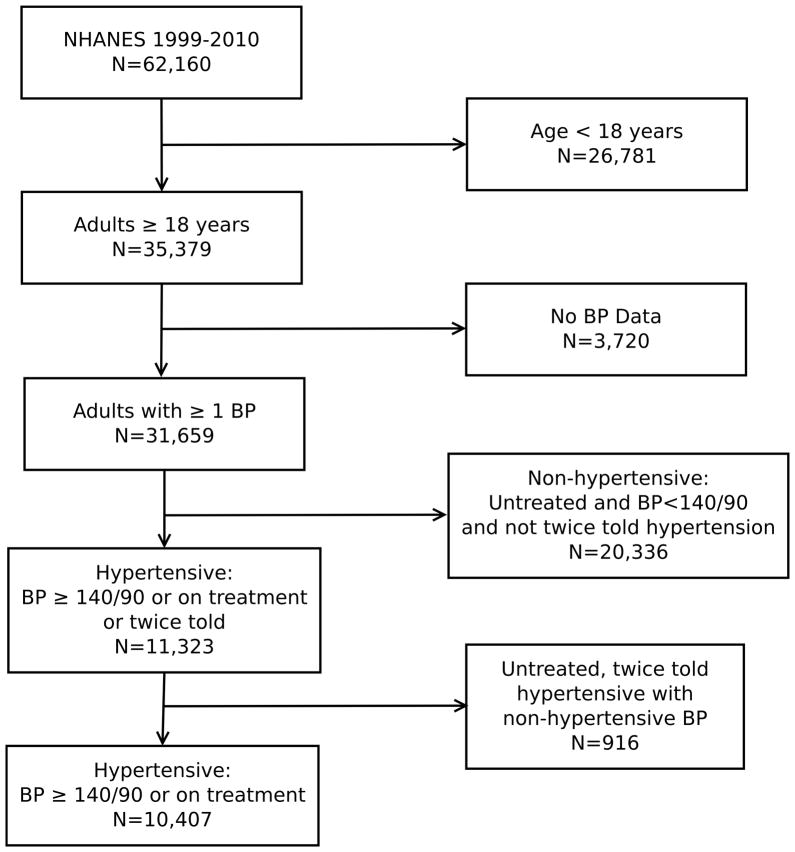

The stepwise process by which the study sample of 31,659 adults was derived from the NHANES 1999–2010 database is depicted in Figure 1. Selected characteristics of all adults included in the NHANES 1999–2002, 2003–2006, and 2007–2010 time periods are provided in Table 1. Mean age increased nearly two years across surveys but remained in the mid-forties. Systolic and diastolic BP declined over time in all adults combined, whereas only diastolic BP declined in non-hypertensive individuals. The proportion of adults classified with Stage 2 hypertension was lower in 2007–2010, whereas the proportion with normal BP was greater, than in the two earlier time periods. Mean BMI and the proportion of obese adults increased with time. The percentage of adults with diagnosed diabetes mellitus increased over time; the proportion with CKD did not change.

Figure 1.

The process by which the various categories of patients for this report were derived from NHANES 1999 – 2010 is depicted in the flow diagram.

Descriptive characteristics of hypertensive subjects defined by BP ≥140/≥90 mmHg and/or reported treatment and (traditional hypertension [tHTN]) and untreated twice-told hypertensive subjects with non-hypertensive BP, (non-traditional [ntHTN]) are shown in Table 2. Among the tHTN group, BP declined 7.5/4.6 mmHg from 1999–2002 to 2007–2010. The proportion of hypertensive patients with Stage 2 and Stage 1 hypertension each declined 9–10% from the first to last survey period, whereas the proportion with BP in the pre-hypertensive and normal range increased. Mean BMI and the percentage of obese and diabetic subjects rose with time. Prevalent CKD did not change.

Among ntHTN, the only significant difference was a higher proportion of lean individuals in 2003–2006 than 2007–2010. The ntHTN group was younger than tHTN patients. They had a lower proportion of individuals with diabetes and chronic kidney disease but similar mean BMI values. While ntHTN subjects had lower systolic and diastolic BP values than tHTN patients, their BP values were greater than normotensives (Table 1). Moreover, the majority of normotensive individuals had normal BP <120/<80, whereas the majority of ntHTN individuals had BP in the pre-hypertension range.

Table 3 provides data on hypertension control during three NHANES time periods from 1999–2010 to two levels including: (a) <140/<90 mmHg for all subjects and (b) <140/<90 for patients without and <130/<80 mmHg for patients with diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease. Control rates are shown across the three time periods and for the two levels of control excluding and including patients with ntHTN. Hypertension control increased significantly with time at both BP goal levels and when designating ntHTN individuals as either hypertensive or non-hypertensive.

Table 3.

BP control to different in three NHANES periods excluding and including ntHTN subjects.

| NHANES Time Period

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| <140/<90 in all HTN patients | 1999–2002 | 2003–2006 | 2007–2010 |

| Excluding uHTN | 33.3 (30.6, 36.0)‡ | 42.7 (39.9, 45.5)‡ | 51.8 (49.6, 53.9)‡ |

| Including uHTN | 39.5 (37.3, 41.7)‡ | 48.5 (45.7, 51.4)‡ | 56.5 (54.2, 58.7)‡ |

| <140/<90 without and <130/<80 with DM and/or CKD | |||

| Excluding uHTN | 28.7 (26.1, 31.5)‡ | 36.9 (34.0, 39.9)‡ | 46.6 (44.2, 48.9)‡ |

| Including uHTH | 34.6 (32.4, 37.0)‡ | 42.8 (39.9, 45.7)‡ | 51.6 (49.2, 53.9)‡ |

p<0.001

The symbol on the column 1999–2002 indicate the p-value for comparison with 2003–2006

The symbol on the column 2003–2006 indicate the p value for comparison with 2007–2010

The symbol on the column 2007–2010 indicate the p value for comparison with 1999–2002

Table 4 provides data on the clinical epidemiology of hypertension when comparing NHANES 2007–2008 to 2009–2010 using both definitions of prevalent hypertension, i.e., designating ntHTN patients as non-hypertensive (Definition A) or hypertensive (Definition B). With both definitions prevalence and awareness did not change within group between the two survey periods, whereas the proportion of patients treated and controlled (all hypertensives to <140/<90 mmHg and those with diabetes and/or CKD to <130/<80 were marginally higher (p-values 0.05 to 0.07) in 2009–2010. As expected, hypertension control rates were lower when defined by goal values <140/<90 in patients without and <130/<80 in patients with diabetes mellitus and/or CKD rather than <140/<90 for all patients.

Table 4.

Clinical epidemiology of hypertension in NHANES 2007–2008 vs. 2009–2010: Impact of untreated twice-told hypertensive patients with non-hypertensive BP.

| NHANES | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Def A | Number | 2057 | 2093 | |

| Prevalence, % | 29.0 (27.6, 30.5) | 28.4 (26.3, 30.6) | 0.32 | |

| Awareness, % | 80.7 (78.2, 83.0) | 81.1 (78.1, 83.8) | 0.41 | |

| Treated,% | 72.7 (70.3, 74.9) | 75.8 (72.0, 79.2) | 0.06 | |

| Controlled, % | <140/<90 | 50.1 (46.8, 53.5) | 53.3 (50.3, 56.3) | 0.07 |

| <140/<90, <130/<80 DM/CKD† | 44.7 (41.0, 48.4) | 48.4 (45.3, 51.4) | 0.05 | |

| Def B | Number | 2221 | 2284 | |

| Prevalence, % | 32.2 (30.8, 33.7) | 31.4 (29.3, 33.6) | 0.32 | |

| Awareness, % | 82.6 (80.1, 84.9) | 83.0 (80.2, 85.5) | 0.41 | |

| Treated, % | 65.5 (63.4, 67.6) | 68.6 (65.2, 71.8) | 0.06 | |

| Controlled, % | <140/<90 | 55.0 (51.4, 58.6) | 57.8 (54.8, 60.8) | 0.07 |

| <140/<90, <130/<80 DM/CKD† | 49.8 (45.9, 53.7) | 53.2 (50.2, 56.2) | 0.05 | |

Def=Definition; A=excluding and B=including untreated, twice-told hypertensive with non-hypertensive BP (ntHTN). DM=diabetes mellitus; CKD=chronic kidney disease

Hypertension control with BP goal <140<90 in patients without and <130/<80 mmHg in patients with diabetes mellitus and/or chronic kidney disease

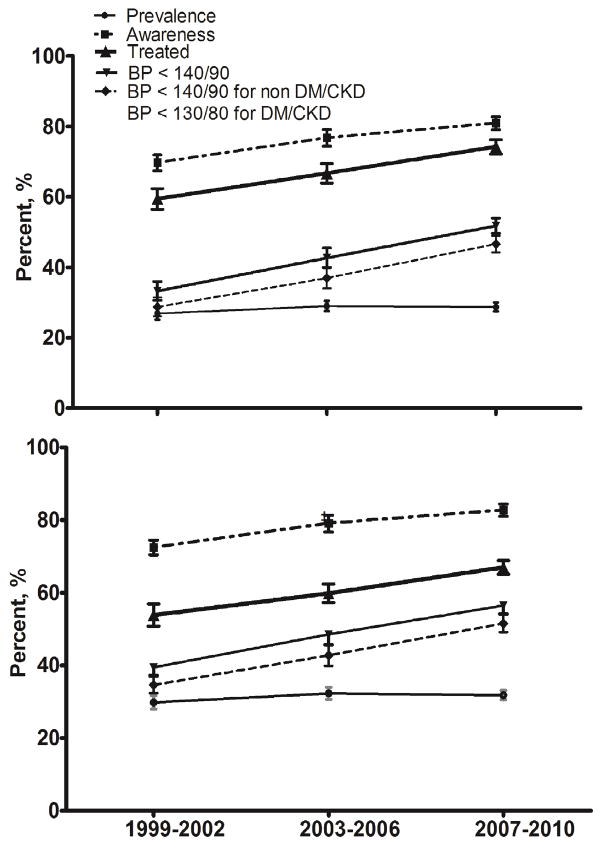

Awareness, treatment, control and prevalence of hypertension using both definitions of prevalent hypertension are depicted in Figure 1 for the three NHANES time periods. Hypertension awareness, treatment and control increased with time, whereas prevalence did not change. Hypertension prevalence, awareness and control were higher when designating ntHTN as hypertensive, whereas treatment was lower.

Discussion

The principal objectives of this report were to: (a) describe clinical characteristics of untreated twice-told hypertensive subjects with non-hypertensive BP, i.e., non-traditional hypertension (ntHTN) and assess their impact on the (b) clinical epidemiology of hypertension in the U.S. and (c) Healthy People goals. A related objective was to define the impact of assessing BP control with a goal of <140/<90 mmHg for all patients versus <140/<90 in patients without and <130/80 in patients with diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease on hypertension control goals.

Clinical characteristics of ntHTN

The ntHTN group was younger than tHTN patients and similar in age to the general adult population (Table 1). Body mass index ntHTN and tHTN individuals were similar and higher than all adults combined. The ntHTN subjects were less likely to have diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease than tHTN patients, which probably reflected their relative youth. BP values in ntHTN subjects were lower than ‘traditional’ hypertensives but higher than normotensives. Of note, BP values in ntHTN subjects were similar to BP in treated, controlled hypertensive patients reported previously.21

BP is variable, and there are several errors in measuring BP which often occur in clinical settings.1,22–24 Thus, it is not surprising that roughly 3% of all adults were previously told on two occasions that they were hypertensive but had a non-hypertensive on NHANES examination. In NHANES, BP is measured according to guidelines including correct positioning of the patient and a period of rest. According to NHANES reporting guidelines, the initial reading was not included in defining mean systolic and diastolic BP values in >90% of participants who had ≥2 BP measurements. In other words, correct positioning and rest prior to BP measurement and discarding the first reading would generally lead to lower BP values when compared to a single, hurried measurement in the usual clinical setting.1,24 Of note, >60% of individuals with ntHTN have pre-hypertensive range BP values. Moreover, they are predominantly overweight and obese, both of which increase risk of future hypertension.25

The available data do not clearly resolve whether individuals in NHANES with ntHTN are more appropriately classified as hypertensive or non-hypertensive. NHANES is a critically important dataset for assessing progress toward major national health objectives, e.g., Healthy People, and indirectly assessing the effectiveness of healthcare policy and delivery. Thus, inconsistencies in classifying BP status are worth resolving. BP on repeated visits and/or out-of-office readings, e.g., 24–48 hour ambulatory BP monitoring would enhance accuracy in defining the clinical epidemiology of hypertension.1

Impact of ntHTN on the clinical epidemiology of hypertension

The ntHTN group comprised ~3% of the U.S. adult population (Table 2), i.e, raised estimates of prevalent hypertension by ~3%. Given 234.6 million adults ≥18 years old in the U.S. 2010 census,26 the estimated number of hypertensive patients increases by roughly 7 million when ntHTN are included, e.g., the AHA Statistical Updates.9,10 Awareness and control were higher and the percentage of hypertensive patients on treatment lower when ntHTN individuals were classified as hypertensive rather than non-hypertensive (Figure 1).

The impression that hypertension control in the U.S. remains at <50% designated ntHTN subjects as non-hypertensive and included the first BP measurement in calculating mean systolic and diastolic BP.27,28 The determination of mean systolic and diastolic BP by including the first reading is consistent with hypertension guidelines but not with NHANES reporting guidelines and leads to higher BP values and lower control rates for many hypertensive patients.1,4,29

Hypertension control is ~5–6% higher when ntHTN subjects are classified as hypertensive rather than non-hypertensive. Defining BP control as <140/<90 mmHg in all patients rather than <140/<90 in patients without and <130/<80 in patients with diabetes and/or CKD also raises hypertension control ~5–6% across three different NHANES periods from 1999–2010. Thus, large absolute differences of ~10–12% in hypertension control between reports can be explained by these two factors alone and further magnified by including the first BP value (Table 3).4,21,27–29 Of note, Canadian hypertensive patients met the U.S. Healthy People 2020 goal in 2007–2009, with control at 64.6% (95% CI 60.0%–69 .2%). Their high level of control was achieved without designating ntHTN as hypertensive.22

Irrespective of the hypertension control definition of control, the time-dependent improvement in hypertension control was evident across the three NHANES timer periods (Table 3). Moreover, it appeared that progress was continuing from 2007–2008 to 2009–2010 (Table 4). The observations attest to the effectiveness of primary healthcare for improving population health, despite a growing proportion of uninsured adults in 2009–2010.28

Impact of ntHTN on Healthy People goals

When excluding the group with ntHTN, the Healthy People 2010 goal of controlling 50% of all hypertensive patients to <140/<90 was met (51.8%, 95%CI 49.6–53.9%) and exceeded when they were included (56.5%, 95%CI, 54.2–58.7%). Hypertension is a highly prevalent disorder and a major contributor to morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular and chronic kidney diseases.1 Thus, reducing prevalent hypertension is an important national and international health topic.30 The U.S. Healthy People goals 2000 and 2010 included objectives for reducing prevalent hypertension to 16%.2,3 Recognizing the lack of progress in hypertension prevention, Healthy People 2020 set a more credible goal of reducing prevalent hypertension by a relative 10% to 26.9%. Designating ntHTN subjects as hypertensive raises prevalent hypertension from 28.7% to 31.8% in 2007–2010 thereby reducing the likelihood of achieving the Healthy People 2020 goal for prevalent hypertension.

Summary

Individuals with non-traditionally defined hypertension are younger and less likely to have diabetes and CKD than traditionally defined hypertensives but equally overweight and obese. They comprise ~3% of all adults, and thus raise estimates of prevalent hypertension by approimxately 7 million individuals in the U.S. in 2010. Moreover, inclusion of ntHTN as hypertensive raises hypertension control rates ~5–6% aand assessing BP control for all patients at <140/<90 versus <140/<90 in patietns without and <130/<80 for patients with diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease also raises control ~5–6%. Together, these two variables can lead to 10–12% absolute differences in hypertension control between reports. Given the importance of accurately classifying ntHTN patients in assessing the clinical epidemiology of hypertension within and between populations over time, addition of 24–48 hour ambulatory BP and/or home BP monitoring could be useful in correctly assigning BP category and assessing the clinical epidemiology of hypertension.1 Consistent definitions of prevalent hypertension and control are essential in assessing the burden of risk and the effectiveness of healthcare policy and delivery in moving toward important national health objectives.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

The impact of excluding (A) or including (B) untreated, twice-told hypertensive patients with non-hypertensive BP (ntHTN) on hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in three NHANES time periods from 1999–2010 are provided. The actual mean and 95% confidence intervals for each data point are provided online in Table S1.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This original paper indirectly supported by grants from the Centers for Disease Control (Community Transformation Grant thru the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control [SC DHEC]); State of South Carolina; NIH HL105880; SC DHEC, Tobacco Control and Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention; NIH NS058728, and NIH HL091841.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Brent Egan: In addition to federal and state funding sources listed, during the previous three years Dr. Egan has received research support from Daiichi-Sankyo (>$10,000), Medtronic (>$10,000), Novartis (>$10,000), Takeda (>$10,000) and has served as a consultant to Astra Zeneca (<$10,000), Novartis (<$10,000), Medtronic (<$10,000), Takeda (<$10,000) and Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina (>$10,000).

Yumin Zhao: None.

None of the funding agencies had input on the study design, data analysis, interpretation or the decision to submit this paper for publication.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov, 2000. Healthy People 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. [accessed July 11, 2012]; http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HP2020objectives.pdf.

- 4.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ong KL, Cheung BMH, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KSL. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, Thom T, Fields LE, Roccella EJ. Trends in the hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2008;52:818–827. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, Hughes J, Roccella EJ, Sorlie P. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000. A rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44:398–404. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000142248.54761.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2011 Update. A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 Update. A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed July 12, 2012];NHANES methods 2009 – 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/survey_content_99_12.pdf.

- 12. [Accessed July 12, 2012]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2009-2010/questexam09_10.htm.

- 13.The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accord Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appel LJ, Wright JT, Jr, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Astor BC, Bakris G, Cleveland WH, Charleston J, Contreras G, Faulkner ML, Gabbai FB, Gassman JJ, Hebert LA, Jamerson KA, Kopple JD, Kusek JW, Lash JP, Lea JP, Lewis JB, Lipkowitz MS, Massry SG, Miller ER, Norris K, Phillips RA, Pogue VA, Randall OS, Rostand SG, Smorgorzewski MJ, Toto RD, Wang X AASK Collaborative Research Group. Intensive blood pressure control in hypertensive chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:974–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Feldman HI, Greene T, Lash JP, Nelson RG, Rahman M, Deysher AE, Zhang Y, Schmid CH, Levey AS. Evaluation of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation in a large diverse population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2749–2757. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CA, Francis ME, Eberhardt MS, Chavers B, Engelgau M, Kusek JW, Byrd-Holt D, Narayan KMV, Herman WH, Jones CP, Salive M, Agaodoa LY. Microalbuminura in the US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kid Dis. 2002;39:445–459. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.31388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvin E, Manzi J, Stevens LA, Van Lente F, Lacher DA, Levey AS, Coresh J. Calibration of serum creatinine in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1988–1994, 1999–2004. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;59:918–926. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris MI, Goldstein DE, Flegal KM, Little RR, Cowie CC, Widemeyer H-M, Eberhardt MS, Byrd-Holt DD. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults; the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:518–524. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN, Brzezinski WA, Ferdinand KD. Uncontrolled and apparent treatment resistant hypertension in the U.S. 1988–2008. Circulation. 2011;124:1046–1058. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAlister FA, Wilkins K, Joffres M, Leenen FHH, Fodor G, Gee M, Tremblay MS, Walker R, Johansen H, Campbell N. Changes in the rates of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Canada over the past two decades. CMAJ. 2011;183:1007–1013. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosner B, Polk BF. The implications of blood pressure variability for clinical and screening purposes. J Chron Dis. 1979;32:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones DW, Appel LJ, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ, Lenfant C. Measuring blood pressure accurately. New and persistent challenges. JAMA. 2003;289:1027–1030. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selassie A, Wagner CS, Laken ML, Ferguson ML, Ferdinand KC, Egan BM. Progression is accelerated from pre-hypertension to hypertension in African Americans. Hypertension. 2011;58:579–587. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.177410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howden LM, Meyer JA. [accessed November 8, 2012];Age and sex composition 2010: US Census Briefs. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf.

- 27.Guo F, He D, Zhan W, Walton RG. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, management and control of hypertension among United States adults, 1999 to 2010. JACC. 2012;60:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: awareness and treatment of uncontrolled hypertension among adults—United States, 2003–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(35):703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handler J, Zhao Y, Egan BM. Impact of the number of blood pressure measurements on blood pressure classification in U.S. adults: NHANES 1999–2008. J Clin Hypertens. 2012 doi: 10.1111/jch.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkovic V, Huxley R, Wu Y, Prabhakaran D, MacMahon S. The burden of blood pressure-related disease: A neglected priority for global health. Hypertension. 2007;50:991–997. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vital Signs: Health Insurance Coverage and Health Care Utilization - United States, 2006–2009 and January–March 2010. MMWR. 2010;59:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.