Abstract

Although inflammatory monocytes (IM) [CD11b+Ly6Chi cells] have been shown to play important roles in cell-mediated host protection against intracellular bacteria, protozoans, and fungi, their potential impact on humoral immune responses to extracellular bacteria are unknown. IM, localized largely to the splenic marginal zone of naïve CD11b-Diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) bone marrow chimeric mice were selectively depleted following treatment with DT, including no reduction of CD11b+ peritoneal B cells. Depletion of IM resulted in a marked reduction in the polysaccharide (PS)-specific, T cell-independent IgM and T cell-dependent IgG responses to intact, heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pn) with no effect on the associated Pn protein-specific IgG response, or on the PS- and protein-specific IgG responses to a soluble pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. IM acted largely within the first 48 h following the initiation of the immune response to Pn to induce the subsequent production of PS-specific IgM and IgG. Adoptive transfer of highly purified IM from wild-type mice into DT-treated CD11b-DTR mice completely restored the defective PS-specific Ig response to Pn. IM were phenotypically and functionally distinct from circulating CD11b+CD11clowLy6G−/C− cells (immature “blood DC”), previously described to play a role in Ig responses to Pn, in that they were CD11c− as well as Ly6Chi, and did not internalize injected Pn during the early phase of the response. These data are the first to establish a critical role for IM in the induction of an Ig response to an intact extracellular bacterium.

Keywords: Rodent, B cells, monocytes, bacterial, antibodies, antigens, vaccination

Introduction

Murine blood monocytes comprise two distinct subsets: CD11b+CCR2+CX3CR1+/−Ly6ChighLy6G−F4/80+ and CD11b+CCR2−CX3CR1highLy6C+/−Ly6G−F4/80+ cells (1, 2). CD11b+Ly6Chigh monocytes migrate from the BM to peripheral tissues, such as the spleen in a CCR2-dependent manner in response to inflammatory stimuli and are thus termed “inflammatory monocytes” (IM) (1). Once recruited into peripheral tissue, IM can further differentiate into DC that produce TNF-α and inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase (“TipDC”), and into “inflammatory DC” (1–3). TipDC, which upregulate CD80, CD86, MHC-II and CD11c, rapidly migrate to the T cell area of the spleen. Although they possess APC activity, their marked reduction in CCR2−/− mice does not result in defective T cell priming. However, TipDC mediate protective innate immunity against a number of fungal, protozoan, and intracellular bacterial pathogens via MyD88-dependent production of large amounts of TNF-α and/or NO (2).

CD11b+Ly6Chigh cells, expanded in malignant states, autoimmunity, and bacterial and fungal infections, can also suppress CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cell function and have been referred to as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC). MDSC also include CD11b+Ly6G+ cells (“granulocytic”) in addition to CD11b+Ly6Chigh cells (“monocytic”) (4). Ly6Chigh MDSC are capable of suppressing CD4+ T cell function via production of NO (5) and IL-10 (6, 7). However, Ly6Chigh cells appear to favor differentiation of CD4+ T cells into Th1, as opposed to Th2 cells, which may favor immunity to intracellular pathogens (8, 9).

Thus, IM, TipDC, and MDSC appear related via their derivation from CCR2+CD11b+Ly6Chigh cells, but vary in differentiation state and/or their functional effects depending upon the experimental model. Although Ly6Chigh monocytic cells are implicated in cell-mediated immune responses in the setting of intracellular pathogens, autoimmunity, and tumor immunity, their potential role in adaptive immunity to extracellular bacteria is unknown. Of note, i.p. injection of alum into mice recruits IM, that take up and process co-injected OVA, and migrate from the peritoneum to further differentiate into CD11c+ DC (10–12). These cells are critical for the alum-mediated Th2 humoral immune response to OVA, apparently via their function as APC. Depletion of CD11c+ monocytes and DC in Diphtheria toxin (DT)-injected CD11c-DTR mice abrogates alum adjuvanticity.

Immunization of mice i.p. with heat-killed, intact Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pn) induces a polysaccharide (PS)-specific T cell-independent (TI) IgM and CD4+ T cell-dependent (TD) IgG response, as well as a TD IgG response specific for a number of pneumococcal proteins (13). We previously proposed a model that suggested that intact bacteria, via expression of TLR and other microbial ligands directly and indirectly (via cytokines from innate cells) provide critical second signals for T cell-independent, in vivo Ig secretion and class switching in polysaccharide-specific B cells activated via multivalent BCR crosslinking (14). One cell implicated in TI responses to intact Pn is the circulating CD11b+CD11clowLy6G−/C− cell (immature “blood DC”) that promotes survival of PS-specific marginal zone B (MZB) cells through secretion of BAFF/APRIL (15). The demonstration in this report of a critical role for IM, which are phenotypically and functionally distinct from blood DC, in TI PS-specific IgM responses to intact Pn now implicates an additional key cellular source for these critical second signals. These data further implicate IM in promoting TD PS-specific IgG responses. The potential interactions between IM and blood DC for eliciting a PS-specific Ig response to an intact bacterium are discussed.

Materials and Methods

Mice

FVB mice were purchased from NCI (Frederick, MD). CD11b-DTR mice on the FVB background were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine; Cat#005515, strain name: FVB-Tg(ITGAM-DTR/EGFP)34Lan/J).

CD11b-DTR bone marrow chimeras

Six-week old FVB mice were kept for 16–18 h without food and then were gamma-irradiated (10 Gy). Within 24 h post-irradiation, the mice were injected i.v. with 1 × 107 bone marrow cells from CD11b-DTR mice, and were maintained on antibiotic water consisting of 200 mg sulfamethoxazole and 40 mg trimethoprim (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), for 2 wk post-irradiation. The mice were used for experiments, 7–8 weeks after injection of bone marrow cells. In each experiment, spleen cells from 1 chimeric mouse each, injected or not injected, with DT (Sigma), were obtained at 24 h, to confirm the depletion of IM (CD11b+Ly6Chi cells) by flow cytometry. Chimeric mice were injected with 700 ng DT/mouse [25 ng per gram mouse weight, average weight/mouse=28 grams] i.p. every 2–3 d throughout the experimental period as previously described (16).

Bacteria, reagents and immunizations

Streptococcus pneumoniae, capsular type 14 (strain R614) was prepared, heat-inactivated, and stored as previously described (17). Mice were injected i.p. with 2 × 108 CFU R614/mouse in saline. Purified S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide type 14 (PPS14) was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Recombinant pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) was expressed in Sacharomyces cerevisiae BJ3505 and purified from supernatant as previously described (18). Phosphorylcholine (PC) covalently linked to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) [PC-KLH] was a gift from Dr. Andrew Lees (Fina BioSolutions, Rockville, MD). PPS14-PspA and CPS (C-polysaccharide [teichoic acid])-PspA conjugates were synthesized as previously described (19). The molar ratio of PPS14 or teichoic acid to PspA was ~1:8. Alum (Allhydrogel 2%) was obtained from Brenntag Biosector (Denmark). A stimulatory 30 mer CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODN) was synthesized at USUHS in the Biomedical Instrumentation Center. PPS14-PspA or CPS-PspA (1 µg/mouse) adsorbed on 13 µg of alum mixed with 25 µg of CpG-ODN was injected i.p.

Flow cytometric analysis

Individual samples of RBC-lysed spleen cells (ACK lysing buffer [Quality Biological, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD]) or peritoneal cells were stained using the following mouse-specific mAbs: PE- or Alexa Fluor 700-anti-CD11b (clone: M1/70), PE- or FITC-anti-Ly6C (clone: AL-21), PE-anti-Ly6G (clone: 1A8), PE- or PE-Cy7-anti-CD11c (clone: HL3), APC- or PE-anti-B220 (clone: RA3-6B2), PE-anti-CD4 (clone: L3T4), PE or PE-Cy5-anti-CD8 (clone: Ly-2 53-6.7), PE- or APC-anti-CD19 (clone: 1D3), APC-anti-CD90 (clone: 53-2.1), FITC-anti-CD23 (clone B3B4), and PE-anti-CD21 (clone 7G6) [BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA); PE-anti-CD5 (clone 53-7.3) and BV421-anti-CD11b [BioLegend]; and PE-Cy7-anti-F4/80 (clone BM8) and PE-anti-PDCA-1 (clone eBio129c) [eBioscience]. Anti-FcγRII/III mAb (clone 2.4G2) was added to each sample at 1 µg in 300 µL containing 1 × 106 cells to block FcγR-mediated binding of specific, labeled mAbs. Cells were analyzed using a LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and results were generated using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Confocal microscopy

R614 was labeled with Alexa-Fluor 405 prior to i.p. injection. Spleens were fixed and processed as previously described (17). Tissues were snap-frozen in Tissue-Tek (VWR, West Chester, PA). Twenty µm thick frozen sections were cut and stained with either PE-anti-mouse Ly6C alone or FITC-anti-mouse Ly6C + PE-anti-CD11b. Immunofluorescence imaging was performed at room temperature with a Zeiss Pascal Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (magnification: 20×, type: Plan Apochromat, numerical aperture: 0.75 NA, acquisition software: AIM). Image J was used for data analysis.

Measurement of serum titers of antigen-specific IgM and IgG by ELISA

Serum titers of PPS14-, PC, and PspA-specific IgM and/or IgG were measured by ELISA. Specifically, plates were coated with 5 µg/ml of PPS14, PC-KLH, or PspA (100 µL/well) followed by 5-fold dilutions of serum samples, starting at a 1/100 serum dilution. For the PPS14-specific ELISA, no cell wall PS was added to serum samples for blocking anti-PC antibodies, since PPS14-coated plates do not bind any detectable PC-specific IgM or IgG (data not shown). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgM or IgG was then added at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml (50 µL/well), followed by substrate (p-nitrophenyl phosphate, disodium) at 1 mg/ml for color development. Color was read at an absorbance of 405 nm on a Multiskan Ascent ELISA reader (Labsystems, Finland).

Adoptive transfer of CD11b+Ly6Chi cells

RBC-lysed spleen cells from wild-type FVB mice were stained with PE-anti-CD11b mAb and positively-selected using anti-PE MACs beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Cambridge, MA). CD11b-enriched cells were then labeled with FITC-anti-Ly6C, and highly purified CD11b+Ly6Chi cells (IM) were obtained by electronic sorting using a BD FACsAria. IM (2 × 105 cells/mouse) were then injected i.v. into CD11b-DTR bone marrow chimeric mice at the same time these mice were injected i.p. with 700 ng DT. Mice were then immunized 24 h later with R614.

Statistics

All experiments were performed at least twice. Serum titers of antigen-specific Ig were calculated from 7 mice per group as the geometric mean +/− SEM. Percentages of splenic and peritoneal cell types were calculated from 3 mice per group as the arithmetic mean +/− SEM. Significance was determined as p≤0.05 using the two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Results

Selective depletion of IM in DT-treated CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice

CD11b-DTR mice (20), on the FVB/N background (21) were previously established, whereby transgenic expression of the human DTR is mediated by the murine CD11b promoter; murine DTR binds DT poorly and thus human DTR expression confers DT sensitivity resulting in DT-induced cell death. Although multiple cells in the spleen express CD11b (i.e. monocytes, macrophages, DC, and neutrophils), injection of CD11b-DTR mice with DT was previously shown to cause a selective loss of splenic CD11b+Ly6Chigh cells (22) (i.e. IM) (2). Macrophages (F4/80+) in the peritoneum, kidney, and ovary, but not spleen or liver, were also depleted (20).

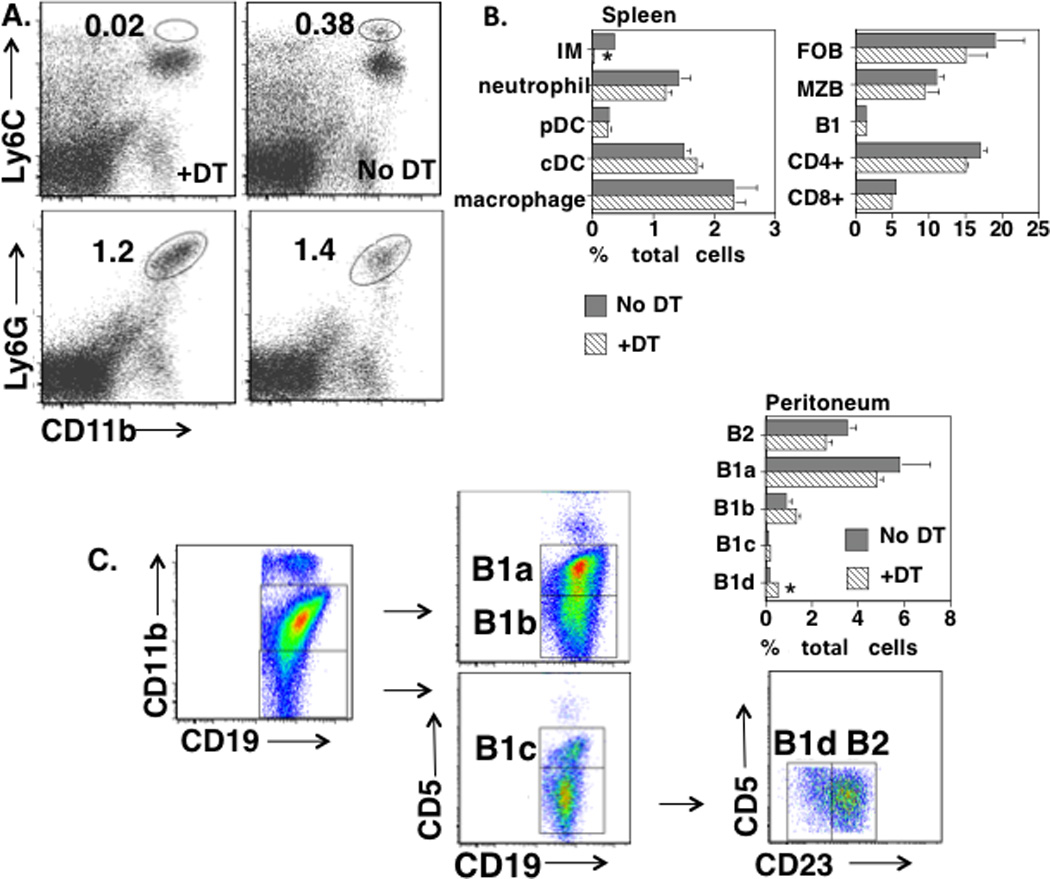

We first set out to evaluate whether CD11b-DTR mice were a useful model for determining a potential role for IM in Ig responses to an intact extracellular bacterium. In initial studies we observed that CD11b-DTR mice given a single injection with a range of DT doses, sufficient to effect IM depletion led to uniform mortality by days 5–7, making this approach unsuitable for studying the humoral immune response. On the basis of a previous report using DT-injected CD11c-DTR mice (23), we set out to overcome this limitation by creating CD11b-DTR BM chimeras. This was accomplished by injection of lethally-irradiated WT mice with CD11b-DTR BM cells. These CD11b-DTR chimeric mice exhibited no obvious ill effects following DT injections, that were administered every 2–3 d over a 21 d period. The dose administered (25 ng per gram mouse weight), as previously suggested (16), was the minimal dose needed to effect optimal IM depletion (data not shown). Consistent with the results of Barbalat et al we demonstrated a >90% depletion of IM (CD11b+Ly6Chi) in the spleens of chimeric mice, 24 h following the first injection of DT with no significant effects on the percentage of neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+ or CD11b+Ly6Cintermed.) [Fig. 1A]. Three additional reports in which CD11b-DTR were studied, also reported a lack of neutrophil depletion following DT injection (16, 20, 24), despite their expression of cell surface levels of CD11b similar to IM, although the mechanism underlying this dichotomy has not been elucidated.

Figure 1. Selective depletion of IM in DT-treated CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice.

(A) Spleen cells from CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice, with or without injection of DT 24 h earlier, were stained with PE-anti-Ly6C + Alexa Fluor 700-anti-CD11b or PE-anti-Ly6G + Alexa Fluor 700-anti-CD11b. Numbers represent percentages of total spleen cell population (average of 3 mice/group). (B) Spleen cells obtained as in “A” were stained with various combinations of mAbs and cell types were identified as indicated in text. Numbers represent percentages of total spleen cell population (average of 3 mice/group). *Significance p≤0.05. (C) Peritoneal cells were stained with various combinations of mAbs and B cell subsets were identified as indicated. Numbers represent percentages of total peritoneal cell population (average of 3 mice/group). *Significance p≤0.05. (A–C), one of two representative experiments.

We further extended these studies by showing no significant effects of DT injection on the percentage of splenic plasmacytoid (CD11clowPDCA-1+CD19−CD90−) or conventional (CD11chiPDCA-1−CD19−CD90−) DC, macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+CD19−CD90−), follicular [FO] (CD19+CD21intermed.CD23+), MZ (CD19+CD21hiCD23low/-), or B1 (CD19+CD5+CD23−) B cells, or CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1B). Importantly, injection of chimeric mice with DT had no significant effect on the percentages of peritoneal B2, B1a, B1b, or B1c B cells, although a modest increase in B1d cells was observed (Fig. 1C). B1a and B1b, but not B1c, B1d, or B2 cells are CD11b+. Since DT had no significant effect on the absolute numbers of total cells obtained from the peritoneum (data not shown), the relative percentages of B cell subsets in DT-treated and untreated mice reflected their absolute numbers. In this regard, DT injection led to a selective loss of peritoneal CD11bhighF4/80high cells (macrophages) [No DT-3.3% of total peritoneal cells, +DT-0.01%], and to an absolute increase in CD11blowF4/80low cells [No DT-0.6% of total peritoneal cells, +DT-5.1%]. Although peritoneal B1a and B1b cells have been implicated in PS-specific natural and adaptive immunity, respectively (25), the functional roles of the more recently described B1c and B1d cells (26) remain to be determined. Further analysis of spleen cell populations from chimeric mice following R614 immunization and treatment with DT every 2–3 d over a 21 d period continued to show a profound and selective loss of splenic IM (data not shown), although the absolute number of splenic neutrophils on d 21 had increased ~4.5-fold relative to untreated chimeric mice (p=0.006, 3 mice per group).

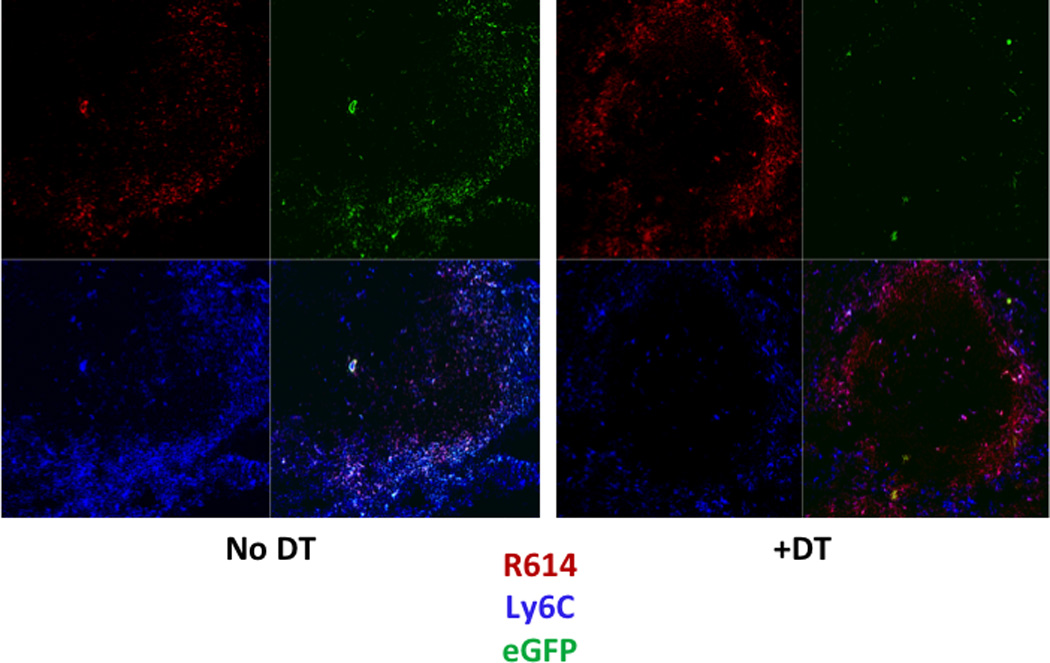

Chimeric mice were then injected or not with DT for 24h, followed by i.p. immunization with Alexa-Fluor 405-labelled, heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae, capsular type 14 [Pn14] (strain R614). Two hours later spleens were evaluated by confocal microscopy using PE-anti-Ly6C mAb (Fig 2). In mice not receiving DT, Ly6C+ cells (eGFP+) were observed within both the MZ and red pulp. Of note, two-color staining for Ly6C and Ly6G demonstrated Ly6C+Ly6G− (IM) largely within the marginal zone, whereas Ly6C+Ly6G+ (neutrophils) were localized mostly within the red pulp (data not shown). Both cell types stained positively for CD11b. Most R614 at this time point were co-localized with IM within the MZ, with some bacteria observed within the red and white pulp. Consistent with our flow cytometric analyses (Fig. 1A), spleens from chimeric mice receiving DT exhibited a marked loss of Ly6C+ cells within the MZ (IM), with no apparent change in Ly6C+ cells within the red pulp (neutrophils) (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Splenic IM are localized largely within the marginal zone in naïve mice and are depleted following DT injection.

Confocal microscopy of spleen sections from non-chimeric CD11b-DTR mice with or without injection of DT 26 h earlier, and with injection of Alexa Fluor 405-R614 (red) 2 h earlier. Sections subsequently stained with PE-anti-Ly6C (blue); eGFP (green). One of two representative experiments.

In a separate set of studies we measured peritoneal B cell subset numbers (B1a, B1b, B1c, B1d, and B2), splenic B1 cells and IM, and blood CD11bhighCD11clow cells (“blood DC”) in CD11b-DTR chimeric mice injected once with DT, followed by R614 immunization 1d later (d0), with further analyses on days 1, 2, and 3 following injection of R614 (Supplementary Fig. 1; 3 mice per group). Of note, we confirmed a >8-fold reduction in splenic IM on d0 with numbers of IM increasing to 2-fold higher than untreated levels on d1, 2, and 3 (p≤0.05 only for d1 and d2). Although 2-fold decreases in blood DC were observed on d0, 1, and 2, relative to untreated, these differences were not statistically significant. Importantly, no significant reduction in the numbers of any peritoneal B cell subset, nor of splenic B1 cells, was observed at any time point. Collectively, these data strongly suggested that CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice could serve as a useful model for evaluating the in vivo role of IM in PS- and protein-specific Ig responses to intact R614.

Selective depletion of IM results in the loss of the PPS14-specific IgM and IgG, but not PspA-specific IgG, response to intact R614 in chimeric mice

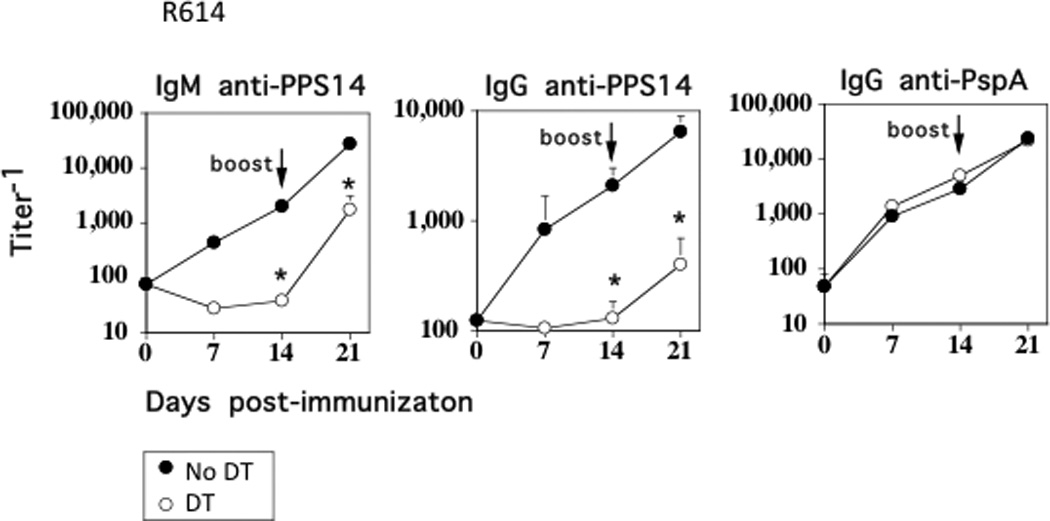

We previously demonstrated that intact, heat-inactivated Pn14 induces a TI IgM and CD4+ TD IgG response specific for the type 14 capsular PS (PPS14) as well as CD4+ TD IgG responses specific for several pneumococcal proteins, including pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) (13). To evaluate a potential role of IM in Ig responses to intact Pn14 (strain R614), CD11b-DTR chimeric mice were treated for 24h with DT, followed by i.p. immunization with intact, heat-inactivated R614 in saline, with boosting 14 d later in a similar manner. DT was administered every 2–3 d for the entire 21 d period of the experiment. In marked contrast to DT-untreated, R614-immunized chimeric mice, primary serum titers of PPS14-specific IgM and IgG were essentially undetectable in chimeric mice treated with DT, whereas the primary PspA-specific IgG response was unaffected (Fig. 3). Following boosting with R614, serum titers of PPS14-specific IgM and IgG increased in DT-treated mice, although they remained significantly below that observed in DT-untreated controls. DT had no effect on the boosted secondary PspA-specific IgG response. DT administration was then discontinued on day 21, and sera were obtained 13 weeks later, without further immunization with R614. The marked reduction in serum titers of PPS14-specific IgM and IgG observed in mice originally treated with DT persisted, relative to mice that were immunized with R614 in the absence of DT (data not shown).

Figure 3. Selective depletion of IM results in the loss of the PPS14-specific IgM and IgG, but not PspA-specific IgG, response to intact R614 in chimeric mice.

CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice (7 mice/group) with or without injection of DT 24 h earlier, were immunized i.p. with R614 (2 × 108 CFU/mouse in saline). DT was administered every 2–3 d for the duration of the experiment. Mice were boosted with R614 on d 14 in a similar manner. Serum titers of antigen-specific IgM and IgG were measured by ELISA. *Significance p≤0.05. One of three representative experiments.

IM act largely within the first 48 h to stimulate the PPS14- and PC-specific IgM and IgG responses to R614

In the next set of experiments we set out to determine the time period during which IM were essential for stimulating PS-specific Ig responses to R614. Chimeric mice were thus treated with DT 24 h prior to R614 immunization as before (d −1), and separate groups of chimeric mice received DT either at the time of R614 immunization (d 0), or 1 d later (d 1). Optimal depletion of IM occurred no later than 18 h following DT administration (data not shown). As illustrated in Fig. 4, DT administered 24 h prior to immunization with R614 resulted in a marked inhibition of the PPS14-specific IgM and IgG responses observed on both day 7 and 14, relative to DT-untreated, R614-immunized chimeric mice. The serum PPS14-specific IgM and IgG responses were essentially reduced to pre-immunization levels. Injection of DT on d 0 resulted in an inhibition of the R614-induced PPS14-specific IgM and IgG responses largely similar to that observed following DT administration at d −1, whereas injection of DT on d 1 resulted in either no significant inhibition or a significantly more modest inhibition than that observed for mice injected with DT on d −1 or d 0.

Figure 4. IM act largely within the first 48 h to stimulate the PPS14- and PC-specific IgM and IgG responses to R614.

CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice (5 mice/group) without or with DT either 24 h earlier (d −1), at the same time (d 0), or 24 h after (d 1) immunization with R614 (2 × 108 CFU/mouse) in saline. DT was administered every 2–3 d for the duration of the experiment. Serum titers of antigen-specific IgM and IgG were measured by ELISA. Vertical dashed lines represent serum titers prior to immunization with R614. *Significance p≤0.05. One of two representative experiments.

We previously reported that R614 also induces a TI IgM and CD4+ TD IgG response specific for the phosphorylcholine (PC) determinant of the cell wall teichoic acid (C-polysaccharide [CPS]) and cell membrane lipoteichoic acid (13). In this regard, similar to the PPS14-specific IgM and IgG responses, chimeric mice treated with DT, either 24h prior to, or at the time of, R614 immunization, also showed a marked reduction in the elicited IgM and IgG anti-PC responses, whereas DT given at d 1, mediated little, or no significant inhibition (Fig. 4). Thus, IM acted largely within the first 48 h of the initiation of the immune response to R614 to induce the subsequent production of PPS14- and PC-specific IgM and IgG.

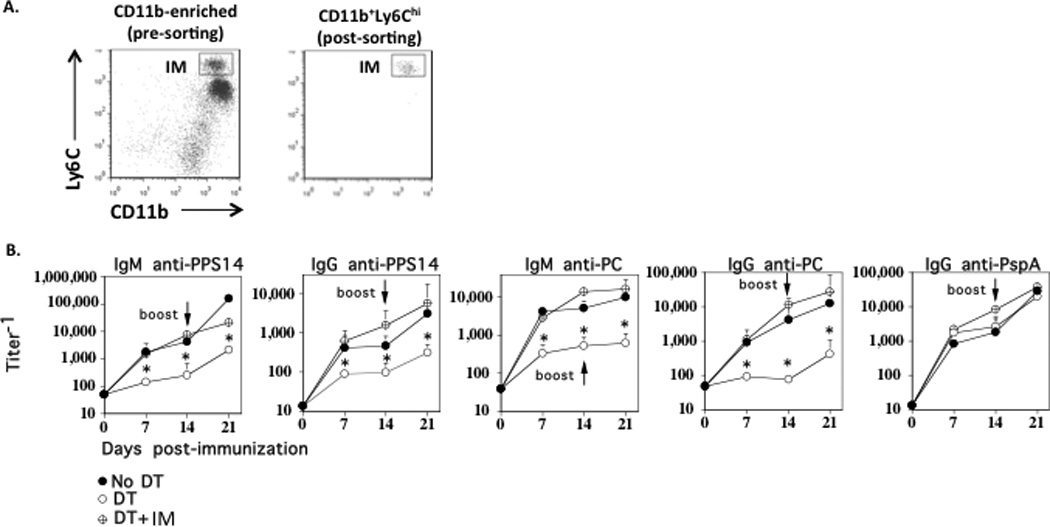

Adoptive transfer of wild-type IM into DT-treated chimeric mice restores the PPS14- and PC-specific IgM and IgG responses

Although our flow cytometric analyses (Fig. 1) strongly suggested that IM were selectively depleted from the spleens of chimeric mice following DT administration, with no depletion of peritoneal B cell subsets, it is theoretically possible that an early, transient alteration in a key cell subset(s), other than IM, following R614 immunization of DT-treated mice, occurred that might have impacted on the PPS14- and PC-specific Ig responses. To formally establish that endogenous IM were indeed the key cell type promoting the PS-specific Ig response to intact R614 in DT-treated chimeric mice, we isolated spleen cells from wild-type FVB mice, utilized magnetic bead sorting to enrich for CD11b+ cells, and then performed electronic cell sorting of CD11b+Ly6Chi cells, obtaining a final purity of >99% IM (Fig. 5A). CD11b-DTR chimeric mice were then injected i.p. with DT in the absence or presence of i.v. injected sort-purified wild-type CD11b+Ly6Chi cells (2 × 105 cells/mouse) 24 h prior to R614 immunization. As illustrated in Fig. 5B, DT injection, in the absence of co-injected IM, again resulted in a marked inhibition in the PPS14- and PC-specific IgM and IgG responses to R614 with no change in the serum titers of PspA-specific IgG. Of note, injection of wild-type IM into DT-treated chimeric mice resulted in a complete restoration of the PPS14-and PC-specific IgM and IgG responses, with no significant effect on the PspA-specific IgG response (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these data establish that IM play a critical role in both the TI IgM and TD IgG anti-PS, but not TD IgG anti-protein responses to an intact bacterium.

Figure 5. Adoptive transfer of wild-type IM into DT-treated chimeric mice restores the PPS14- and PC-specific IgM and IgG responses.

(A) Spleen cells from WT FVB mice were enriched for CD11b+ cells using magnetic cell sorting (left panel) followed by purification of CD11b+Ly6Chi cells by electronic cell sorting (right panel) [>99% purity]. (B) Purified CD11b+Ly6Chi cells (2 × 105 cells/mouse) were injected i.v. into CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice 24 h after DT injection. DT was administered every 2–3 d for the duration of the experiment. DT-treated chimeric mice without injected CD11b+Ly6Chi cells and chimeric mice without injection of DT or CD11b+Ly6Chi cells were included as controls. All groups consisted of 7 mice each. Serum titers of antigen-specific IgM and IgG were measured by ELISA. *Significance p≤0.05. One of two representative experiments.

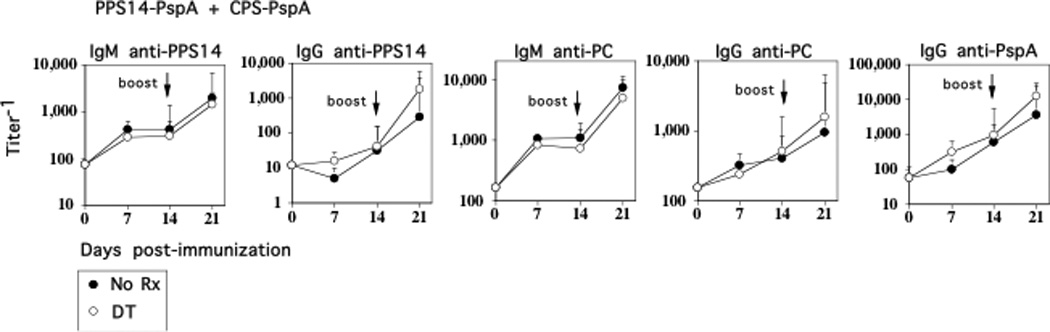

Selective depletion of IM has no effect on the PPS14- or PC-specific IgG responses to soluble pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PPS14-PspA + CPS-PspA)

Covalent linkage of PS to an immunogenic protein creates a “conjugate” vaccine (27) that results in the elicitation of CD4+ TD high-titer, protective IgG anti-PS responses and the generation of immunologic memory (28–30), that is dependent on CD28 costimulation and CD40L (31, 32). We previously confirmed these observations using soluble PPS14-PspA and CPS-PspA conjugates (13). Although, in this regard the PS-specific IgG responses to intact R614 and conjugate share similar features (13) the mechanisms underlying the PPS14-specific IgG responses to intact R614 versus PPS14-PspA conjugate also showed distinct differences (33–35). We thus wished to determine whether endogenous IM also regulated a conjugate-induced PPS14- and PC-specific IgG response. Chimeric mice were immunized i.p. with soluble PPS14-PspA and CPS-PspA conjugates using alum + CpG-ODN as an adjuvant, in the absence or presence of repeated doses of DT. As noted in Fig. 6, in distinct contrast to R614, neither the primary or boosted secondary PPS14- or PC-specific IgG responses to PPS14-PspA + CPS-PspA were affected by DT-induced IM depletion in chimeric mice. As expected, DT also had no effect on the PspA-specific IgG response.

Figure 6. Selective depletion of IM has no effect on the PPS14- or PC-specific IgG responses to soluble pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PPS14-PspA + CPS-PspA).

CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice (7 mice/group) with or without injection of DT 24 h earlier, were injected i.p. with PPS14-PspA (1 µg/mouse) in alum + CpG-ODN. DT was administered every 2–3 d for the duration of the experiment. Mice were boosted with PPS14-PspA on d 14 in a similar manner. Serum titers of antigen-specific IgM and IgG were measured by ELISA. *Significance p≤0.05. One of two representative experiments.

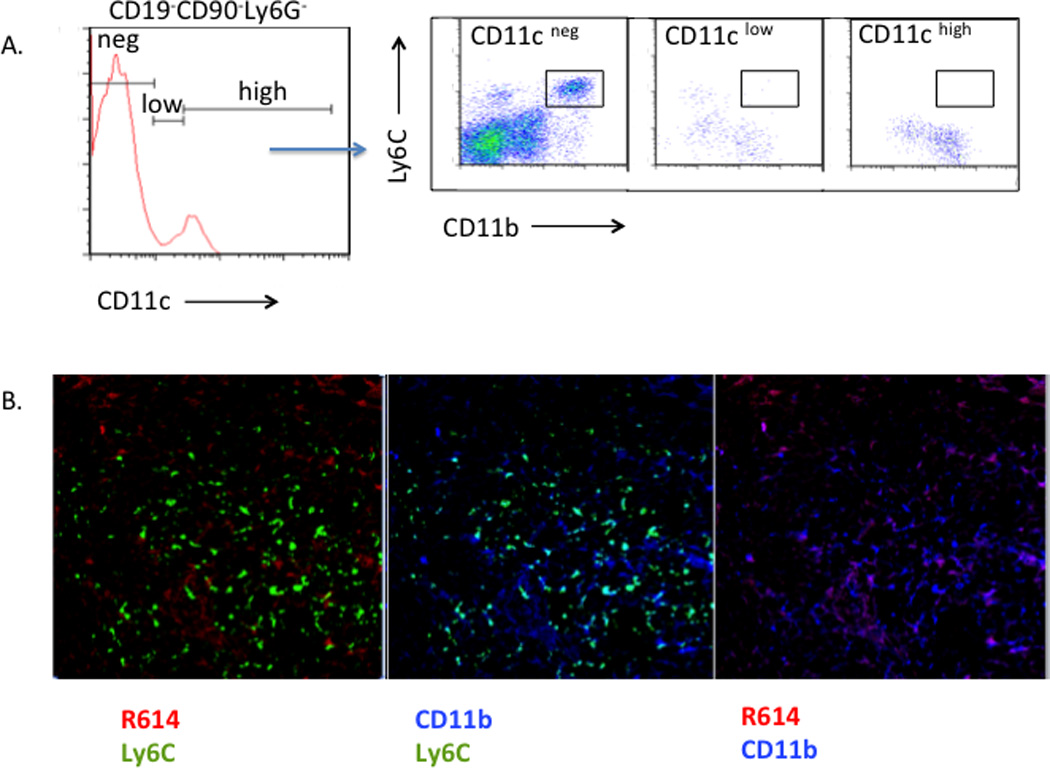

IM are phenotypically and functionally distinct from circulating CD11b+CD11clowLy6G−/C− cells (immature “blood DC”) (15)

One cell implicated in TI Ig responses to intact Pn is the circulating CD11b+CD11clowLy6G−/C− cell (immature “blood DC”) that promotes survival of PS-specific marginal zone B (MZB) cells through secretion of BAFF/APRIL. (15). Blood DC rapidly internalized systemically injected Pn and transported them into the spleen. Although blood DC and IM are both CD11b+ cells, we demonstrate in Fig. 7 that they are clearly distinct. Thus, IM from naïve WT mice, in contrast to that reported for blood DC, showed no detectable expression of CD11c (Fig. 7A). Of note, in further contrast to blood DC (15), splenic CD11b+Ly6C+ cells from WT mice failed to internalize detectable R614, 4h post-immunization, although CD11b+Ly6C− cells showed significant bacterial uptake (Fig 7B). Collectively, these data, and the observation that unlike blood DC, IM are already present in the splenic marginal zone and also express high levels of Ly6C in the naïve mouse (Fig. 2), demonstrate that IM and blood DC are distinct cells that may be playing key complementary roles in the Ig responses to intact Pn.

Figure 7. IM are phenotypically and functionally distinct from circulating CD11b+CD11clowLy6G−/C− cells (immature “blood DC”).

(A) Expression of CD11c (PE-anti-CD11c) on gated CD19-CD90-Ly6G- cells (Alexa Fluor 700-anti-CD19, anti-CD90, and anti-Ly6G) from naïve WT mice followed by Ly6C (FITC-anti-Ly6C) and CD11b (BV421-anti-CD11b) expression on gated CD11cneg, CD11clow, and CD11chigh cells. (B) WT mice were injected with Alexa Flour 405-labeled R614 (red). 4 h post-injection, spleens were obtained and sections were stained with FITC-anti-Ly6C (green) + PE-anti-CD11b (blue).

Discussion

CD11b-DTR BM chimeric mice treated with DT rapidly deplete splenic CD11b+Ly6Chi cells (IM), with no reduction in the number of other splenic CD11b+ cell subsets, or peritoneal CD11b+ B cells (B1a and B1b). B1a and B1b cells have previously been implicated in natural antibody production and adaptive immunity, respectively, in response to TI antigens. Although the selectivity of IM depletion in this model was surprising, several additional reports have made similar observations (16, 20, 22, 24). More importantly, the ability to completely restore the defective PS-specific IgM and IgG responses to intact R614 in CD11b-DTR chimeric mice following injection of highly purified WT IM establishes the validity of this model for studying the role of IM in PS-specific Ig responses to blood-borne extracellular bacteria, where the spleen and perhaps migrating peritoneal B cells play a critical role. This model may also have value in determining a potential role for IM in mediating innate host protection against extracellular bacterial infections, in light of the ability of IM to secrete proinflammatory cytokines. Of interest, CD11b-DTR chimeric mice given repeated doses of DT exhibited a 4.5-fold increase in neutrophils over a 21 d period. In this regard, a recent report demonstrated an increase in neutrophils in the blood and several organs, including the spleen following a single injection of DT in CD11c-DTR mice, which selectively depleted DC (36). Although the increase in neutrophils was attributed to a loss of DC, we did not observe any significant changes in DC numbers in DT-treated CD11b-DTR mice.

PS-specific IgG responses to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae or Neisseria meningitidis are dependent on CD4+ T cells, B7-dependent costimulation and CD40-CD40-ligand interactions (18, 37), similar to that observed for soluble PS conjugate vaccines (31, 32). However, the mechanism by which PS-specific Ig responses are elicited in response to intact Pn versus pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, appears to have distinct features, including differential utilization of MZB versus FO B cells, respectively (33, 34), associated with distinct idiotype usage of the elicited PS-specific antibody (35). Our demonstration that IM play no apparent role in the PS-specific Ig response to conjugate vaccine, in distinct contrast to intact R614, further support a mechanistic dichotomy for these distinct physicochemical forms of PS.

Multivalent BCR crosslinking, as occurs during responses of specific B cells to PS antigens, results in a robust proliferative response without class switching or differentiation into Ig-secreting cells. However, in the presence of a “second signal”, such as IL-2 + IL-3, GM-CSF, or IFN-γ, or BAFF, and/or TLR ligands such as lipoproteins, porin proteins, CpG-ODN, or low doses of LPS, BCR-activated B cells switch and secrete IgM and IgG (15, 38, 39). Collectively, these second signals are likely to be delivered to B cells during infections with intact extracellular bacteria, and thus play a role in PS-specific Ig responses (14). Although the mechanism by which isolated PS elicit Ig responses in vivo requires further study, a contaminating TLR ligand(s) in preparations of “purified” pneumococcal PS was shown to be critical for the elicited PS-specific Ig response in vivo (40). PS themselves may also have immunomodulatory properties (41–43). Elucidation of the cells that likely act as a source of critical second signals during PS-specific Ig responses to intact bacteria, and their mechanisms of action requires further study.

In this regard, our data raise the possibility of an interplay between IM and immature blood DC in costimulating PS-specific Ig responses to intact bacteria. IM are present within the splenic MZ of naïve mice, co-localized with MZB cells, a B cell subset that plays a critical role in PS-specific Ig responses to blood-borne extracellular bacteria (44). Blood DC, in contrast to IM, rapidly internalize blood-borne extracellular bacteria and transport them to the MZ (15). Based on our current observations we speculate that the interplay of MZB, IM and blood DC within the marginal zone may be critical for promoting PS-specific Ig responses to a variety of blood-borne extracellular bacteria. Specifically, we suggest the possibility that IM, through release of proinflammatory cytokines, will directly costimulate TI PS-specific IgM secretion by BCR-activated B cells, as well as indirectly via promoting the release of BAFF from blood DC (15). IM may also promote TD PS-specific IgG responses directly, through differentiation into TipDC or inflammatory DC (1–3), or indirectly by costimulating blood DC maturation through release of cytokines such as TNF-α. In addition, NK cells, in part through secretion of IFN-γ, may also play a role in costimulating PS-specific Ig responses (45–47), with the potential to further interact with IM and blood DC (48), early during bacterial infections.

These data are of further interest in regards to a recent observation that non-inflamed human spleens contain significant numbers of neutrophils in close proximity to MZB cells and that these cells can provide help to MZB cells in vitro for Ig secretion and class switching (49). Indeed, neutropenic patients were found to have reduced levels of IgM, IgG, and IgA specific for non-protein microbial antigens, but not to protein antigens or protein-conjugated polysaccharide. Thus, at least in humans, neutrophils may serve a similar function to what we have observed for IM in mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant AI49192 and the USUHS Dean’s Research and Education Endowment Fund.

We thank Dr. Alexander Lucas (Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, CA) and Dr. James J. Mond (BioConsultingSolutions, Columbia, MD) for careful reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DT

Diphtheria toxin

- DTR

Diphtheria toxin receptor

- IM

inflammatory monocyte

- PC

phosphorylcholine

- PPS14

pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide, serotype 14

- PspA

pneumococcal surface protein A

- R614

heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae, capsular type 14

- TD

T cell-dependent

- TI

T cell-independent

References

- 1.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:421–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:669–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu B, Bando Y, Xiao S, Yang K, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK, Khoury SJ. CD11b+Ly-6C(hi) suppressive monocytes in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5228–5237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen JL, Olson JK. Innate immune CD11b+Gr-1+ cells, suppressor cells, affect the immune response during Theiler's virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Immunol. 2009;183:6971–6980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delano MJ, Scumpia PO, Weinstein JS, Coco D, Nagaraj S, Kelly-Scumpia KM, O'Malley KA, Wynn JL, Antonenko S, Al-Quran SZ, Swan R, Chung CS, Atkinson MA, Ramphal R, Gabrilovich DI, Reeves WH, Ayala A, Phillips J, Laface D, Heyworth PG, Clare-Salzler M, Moldawer LL. MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1(+)CD11b(+) population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1463–1474. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters W, Dupuis M, Charo IF. A mechanism for the impaired IFN-gamma production in C-C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) knockout mice: role of CCR2 in linking the innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2000;165:7072–7077. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leon B, Lopez-Bravo M, Ardavin C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity. 2007;26:519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kool M, Petrilli V, De Smedt T, Rolaz A, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, Bergen IM, Castillo R, Lambrecht BN, Tschopp J. Cutting Edge: alum adjuvant stimulates inflammatory dendritic cells through activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2008;181:3755–3759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kool M, Soullie T, van Nimwegen M, Willart MA, Muskens F, Jung S, Hoogsteden HC, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Alum adjuvant boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:869–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan MB, Mills DM, Kappler J, Marrack P, Cambier JC. Promotion of B cell immune responses via an alum-induced myeloid cell population. Science. 2004;304:1808–1810. doi: 10.1126/science.1089926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snapper CM. Mechanisms underlying in vivo polysaccharide-specific immunoglobulin responses to intact extracellular bacteria. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1253:92–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snapper CM, Mond JJ. A model for induction of T cell-independent humoral immunity in response to polysaccharide antigens. J Immunol. 1996;157:2229–2233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balazs M, Martin F, Zhou T, Kearney JF. Blood dendritic cells interact with splenic marginal zone B cells to initiate T-independent immune responses. Immunity. 2002;17:341–352. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00389-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, Wu S, Lang R, Iredale JP. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Q, Cannons JL, Paton JC, Akiba H, Schwartzberg PL, Snapper CM. A novel ICOS-independent, but CD28- and SAP-dependent, pathway of T cell-dependent, polysaccharide-specific humoral immunity in response to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae versus pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Immunol. 2008;181:8258–8266. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arjunaraja S, Massari P, Wetzler LM, Lees A, Colino J, Snapper CM. The nature of an in vivo anti-capsular polysaccharide response is markedly influenced by the composition and/or architecture of the bacterial subcapsular domain. J Immunol. 2012;188:569–577. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan AQ, Lees A, Snapper CM. Differential regulation of IgG anti-capsular polysaccharide and antiprotein responses to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae in the presence of cognate CD4+ T cell help. J Immunol. 2004;172:532–539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cailhier JF, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, Wu S, Ko K, Watson S, Savill J, Hughes J, Lang RA. Conditional macrophage ablation demonstrates that resident macrophages initiate acute peritoneal inflammation. J Immunol. 2005;174:2336–2342. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taketo M, Schroeder AC, Mobraaten LE, Gunning KB, Hanten G, Fox RR, Roderick TH, Stewart CL, Lilly F, Hansen CT, et al. FVB/N: an inbred mouse strain preferable for transgenic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2065–2069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbalat R, Lau L, Locksley RM, Barton GM. Toll-like receptor 2 on inflammatory monocytes induces type I interferon in response to viral but not bacterial ligands. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/ni.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hebel K, Griewank K, Inamine A, Chang HD, Muller-Hilke B, Fillatreau S, Manz RA, Radbruch A, Jung S. Plasma cell differentiation in T-independent type 2 immune responses is independent of CD11c(high) dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2912–2919. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoneman V, Braganza D, Figg N, Mercer J, Lang R, Goddard M, Bennett M. Monocyte/macrophage suppression in CD11b diphtheria toxin receptor transgenic mice differentially affects atherogenesis and established plaques. Circ Res. 2007;100:884–893. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260802.75766.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy RR. B-1 B cell development. J Immunol. 2006;177:2749–2754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansell CA, Schiering C, Kinstrie R, Ford L, Bordon Y, McInnes IB, Goodyear CS, Nibbs RJ. Universal expression and dual function of the atypical chemokine receptor D6 on innate-like B cells in mice. Blood. 2011;117:5413–5424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avery OT, Goebel WF. Chemo-immunological studies on conjugated carbohydrate-proteins. V. The immunological specificity of an antigen prepared by combining the capsular polysaccharide of type III pneumococcus with foreign protein. J Exp Med. 1931;54:437–447. doi: 10.1084/jem.54.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad H, Chapnick EK. Conjugated polysaccharide vaccines. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999;13:113–133. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beuvery EC, van Rossum F, Nagel J. Comparison of the induction of immunoglobulin M and G antibodies in mice with purified pneumococcal type 3 and meningococcal group C polysaccharides and their protein conjugates. Infect Immun. 1982;37:15–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.1.15-22.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneerson R, Barrera O, Sutton A, Robbins JB. Preparation, characterization, and immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide-protein conjugates. J Exp Med. 1980;152:361–376. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guttormsen HK, Wetzler LM, Finberg RW, Kasper DL. Immunologic memory induced by a glycoconjugate vaccine in a murine adoptive lymphocyte transfer model. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2026-2032.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guttormsen HK, Sharpe AH, Chandraker AK, Brigtsen AK, Sayegh MH, Kasper DL. Cognate stimulatory B-cell-T-cell interactions are critical for T-cell help recruited by glycoconjugate vaccines. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6375–6384. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6375-6384.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colino J, Chattopadhyay G, Sen G, Chen Q, Lees A, Canaday DH, Rubtsov A, Torres R, Snapper CM. Parameters underlying distinct T cell-dependent polysaccharide-specific IgG responses to an intact gram-positive bacterium versus a soluble conjugate vaccine. J Immunol. 2009;183:1551–1559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chattopadhyay G, Khan AQ, Sen G, Colino J, Dubois W, Rubtsov A, Torres RM, Potter M, Snapper CM. Transgenic Expression of Bcl-xL or Bcl-2 by Murine B Cells Enhances the In Vivo Antipolysaccharide, but Not Antiprotein, Response to Intact Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Immunol. 2007;179:7523–7534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colino J, Duke L, Arjunaraja S, Chen Q, Liu L, Lucas AH, Snapper CM. Differential Idiotype Utilization for the In Vivo Type 14 Capsular Polysaccharide-Specific Ig Responses to Intact Streptococcus pneumoniae versus a Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. J Immunol. 2012;189:575–586. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tittel AP, Heuser C, Ohliger C, Llanto C, Yona S, Hammerling GJ, Engel DR, Garbi N, Kurts C. Functionally relevant neutrophilia in CD11c diphtheria toxin receptor transgenic mice. Nat Methods. 2012;9:385–390. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu ZQ, Vos Q, Shen Y, Lees A, Wilson SR, Briles DE, Gause WC, Mond JJ, Snapper CM. In vivo polysaccharide-specific IgG isotype responses to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae are T cell dependent and require CD40- and B7-ligand interactions. J Immunol. 1999;163:659–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snapper CM, Mond JJ. Towards a comprehensive view of immunoglobulin class switching. Immunol Today. 1993;14:15–17. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90318-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Litinskiy MB, Nardelli B, Hilbert DM, He B, Schaffer A, Casali P, Cerutti A. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:822–829. doi: 10.1038/ni829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen G, Khan AQ, Chen Q, Snapper CM. In Vivo Humoral Immune Responses to Isolated Pneumococcal Polysaccharides Are Dependent on the Presence of Associated TLR Ligands. J Immunol. 2005;175:3084–3091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanswal S, Katsenelson N, Allman W, Uslu K, Blake MS, Akkoyunlu M. Suppressive effect of bacterial polysaccharides on BAFF system is responsible for their poor immunogenicity. J Immunol. 2011;186:2430–2443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalka-Moll WM, Tzianabos AO, Bryant PW, Niemeyer M, Ploegh HL, Kasper DL. Zwitterionic polysaccharides stimulate T cells by MHC class II-dependent interactions. J Immunol. 2002;169:6149–6153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cobb BA, Wang Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. Polysaccharide processing and presentation by the MHCII pathway. Cell. 2004;117:677–687. doi: 10.016/j.cell.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pillai S, Cariappa A, Moran ST. Marginal zone B cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:161–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilder JA, Koh CY, Yuan D. The role of NK cells during in vivo antigen-specific antibody responses. J Immunol. 1996;156:146–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michael A, Hackett JJ, Bennett M, Kumar V, Yuan D. Regulation of B lymphocytes by natural killer cells. Role of IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1989;142:1095–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snapper CM, Yamaguchi H, Moorman MA, Mond JJ. An in vitro model for T cell-independent induction of humoral immunity. A requirement for NK cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:4884–4892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerosa F, Baldani-Guerra B, Nisii C, Marchesini V, Carra G, Trinchieri G. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:327–333. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puga I, Cols M, Barra CM, He B, Cassis L, Gentile M, Comerma L, Chorny A, Shan M, Xu W, Magri G, Knowles DM, Tam W, Chiu A, Bussel JB, Serrano S, Lorente JA, Bellosillo B, Lloreta J, Juanpere N, Alameda F, Baro T, de Heredia CD, Toran N, Catala A, Torrebadell M, Fortuny C, Cusi V, Carreras C, Diaz GA, Blander JM, Farber CM, Silvestri G, Cunningham-Rundles C, Calvillo M, Dufour C, Notarangelo LD, Lougaris V, Plebani A, Casanova JL, Ganal SC, Diefenbach A, Arostegui JI, Juan M, Yague J, Mahlaoui N, Donadieu J, Chen K, Cerutti A. B cell-helper neutrophils stimulate the diversification and production of immunoglobulin in the marginal zone of the spleen. Nat Immunol. 2011;13:170–180. doi: 10.1038/ni.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.