Abstract

The objectives of this study were: to compare indices of 24-hour BP following a physician-pharmacist collaborative intervention and to describe the associated changes in antihypertensive medications. This was a secondary analysis of a prospective, cluster-randomized clinical trial conducted in 6 family medicine clinics randomized to co-managed (n=3 clinics, 176 subjects) or control (n=3 clinics, 198 subjects) groups. Mean ambulatory systolic BP was significantly lower in the co-managed versus the control group: daytime SBP 122.8 mm Hg versus 134.4 mm Hg (p<0.001); nighttime SBP 114.8 mm Hg versus 123.7 mm Hg (p<0.001); and 24-hour SBP 120.4 mm Hg versus 131.8 mm Hg (p<0.001), respectively. Significantly more drug changes were made in the co-managed than in the control group (2.7 versus 1.1 changes/subject, p<0.001), and there was greater diuretic use in co-managed subjects (79.6% versus 62.6%, p<0.001). Ambulatory BPs were significantly lower for the subjects who had a diuretic added during the first month compared with those who never had a diuretic added (p<0.01). Physician-pharmacist co-management significantly improved ambulatory BP compared with a control group. Anti-hypertensive drug therapy was intensified much more for subjects in the co-managed group.

Keywords: hypertension management, clinical trial, pharmacist management, ambulatory blood pressure control

Background

Approximately 31% of U.S adults have hypertension.1 High blood pressure (BP) is the most frequent treatable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke and death,2 and it significantly impacts healthcare costs.3–5 It has been reported that 17.8% of deaths in the U.S. are attributable to hypertension.5 While the benefit of appropriate treatment is well known, BP control rates remain low. According to the 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, only 43.6% of hypertensive patients have their BP controlled.1 New approaches must be developed in order to achieve the 2020 hypertension control goal of 61.2% established by the Department of Health and Human Services.6

In recent years, researchers have investigated strategies to improve BP management,7–14 including physician-pharmacist collaborative care, where the pharmacist and physician work together to develop an individualized care plan to optimize antihypertensive drug therapy. This model has been shown to dramatically improve BP control.15–17 In a systematic review of quality improvement strategies for hypertension management, the team care model was found to be associated with the largest reduction in BP outcomes.18 Moreover, a meta-analysis that examined the potency of team-based care interventions found greater reductions in clinic SBP with pharmacist interventions when compared with nurse interventions (-8.44 mm Hg versus -4.80 mm Hg for the median reduction in SBP).19 Clinic BPs may overestimate response to treatment, and confirmation with ambulatory BPs is an important validation of the effect of the intervention. Although the effect of physician-pharmacist collaborative care on clinic BP has been demonstrated in other studies, we know of only one other study of team-based care that evaluated ambulatory 24-hour BP control.20 We previously conducted a cluster-randomized trial in 5 medical offices operated by the University of Iowa16 and published the results of 24-hour BP control. 20 That study population was relatively small.

The other study that used 24-hour BP monitoring only reported the clinic-based research BP control rates.17 In that study, BP control was significantly better with physician-pharmacist co-managed care compared to a control group. The purpose of the present study is to report the 24-hour BP results of this prospective, cluster-randomized controlled clinical trial that was conducted in 6 community-based family medicine offices throughout the state of Iowa. This is the first study to detail the changes in specific antihypertensives associated with the differences in 24-hour BP following a physician-pharmacist co-management.

Methods

This study was a cluster-randomized controlled clinical trial in six Iowa community-based family medicine offices. Each medical office was randomized to a physician-pharmacist co-managed group (n=3) or to a control group (n=3). The methods were previously described but will be briefly reviewed here.17 All 6 offices had clinical pharmacists on their staff who had worked in these offices for at least 3 years. The study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board and the Institutional review Boards for each of the 6 medical offices. All subjects signed informed consent.

Eligible subjects were identified and approached by a research nurse in each participating clinic. Subjects were eligible if they were aged 21 years or older, had a diagnosis of essential hypertension, were taking 0 to 3 antihypertensive medications without changes in their regimens within the past four weeks, and had a systolic BP (SBP) of 140–179 or a diastolic BP (DBP) of 90–109 for uncomplicated hypertension or a SBP between 130–179 or a DBP between 80–109 with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. The qualifying BP was measured by a trained research nurse using standardized research technique. We excluded subjects with serious renal or hepatic disease, as well as those with cognitive impairment, poor prognosis (life expectancy<3 years) and recent myocardial infarction or stroke.

A research nurse at each site was trained to measure the primary research BP measurements using an automated device (HEM 907-XL; Omron Corporation, Schaumburg, Illinois) at baseline, 3 months and 6 months visits.

At the baseline and 6-month visits, the research nurse also initiated a 24-hour ambulatory monitoring session (90217-A; Spacelabs Medical, Issaquah, Washington), placing the 24-hour BP monitor and instructing subjects on its use. During the training program, the research nurses were informed that the ideal cuff should have a bladder length that is 80% of arm circumference and a width that is at least 40% of arm circumference. The research nurse measured the arm with a tape measure and used the following cuffs based on arm circumference: 17–26 cm - “small adult”; 24–32 cm - “adult”; 32–42 cm - “large adult”; 38–50 cm - “extra large adult.” These cuff sizes were based on the instructions for the 24-hour monitors and also listed on the cuffs. The nurses were instructed about the potential for overlap in sizes of some cuffs and to use their discretion if a subject’s arm fell within an overlap range when selecting the appropriate cuff. The research nurses were recertified once a year on proper BP measurement technique.

During the ambulatory 24-hour BP monitor session, readings were obtained every 20 minutes during the day (6:00 AM to 10:00 PM) and every 30 minutes at night (10:00 PM to 6:00 AM). We did not exclude any 24-hour recordings unless all the values were in error. The baseline 24-hour BP results were unavailable to clinic providers until the patient completed the trial. However, physicians in both groups did have access to the research nurse-measured clinic BP values that may have “alerted” physicians that the BP was not controlled. In this regard, the control group constituted “enhanced” usual care.

For subjects in the co-managed group, clinical pharmacists within the intervention offices evaluated medications and BP at baseline and 1 month, and by telephone at 3 months, with the option of more frequent contact if BP remained poorly controlled. Pharmacists identified problems leading to poor BP control, created a care plan and made specific recommendations to the patient’s physician regarding changes in drug therapy. Recommendations were most commonly made face-to-face with the physician, and all the therapy changes had to be accepted by the physician before being implemented. Anti-hypertensive drug therapy recommendations were documented by intervention pharmacists in study case report forms and in the subject’s medical record.

Subjects in the control group received usual care. However, clinical pharmacists in control offices did not make therapy recommendations for study subjects except for typical drug information questions. Subjects in both groups were given written information about managing BP, and physicians in the control sites were also provided with research BP values.

Medical records were abstracted in both the control and co-managed offices to assess drug therapy changes using methods developed by the principal investigator.21, 22 Subjects who did not complete a baseline ambulatory 24-hour BP measurement (12 subjects (6%) in the control group and 16 subjects (8%) in the co-managed group) were excluded from our analysis. However, subjects who refused to complete the second 6-month 24 hour ambulatory BP measurements were included in the present study using an intention-to-treat analysis. We used two approaches to handle missing 6-month data to determine if the results were robust. In the first analysis, we imputed the missing values with the mean 6-month ambulatory BP of the clinic where the subject received care. This analysis might bias in favor of the co-managed group since the clinic mean BP may not represent BP in those who withdrew from the study or refused the follow-up 24-hour BP session. Therefore, we then conducted a second analysis in which we imputed the baseline ambulatory BP value for the missing 6-month values in the co-managed group and the clinic mean 6 month value for the missing 6-month values in the control group. This second analysis was conservative because we imputed baseline BP values in the co-managed group and all baseline values were invariably higher since baseline clinic BPs were all uncontrolled. Because BP improved at 6 months even in control offices, using the clinic mean for missing data in the control group would favor better BP in the control group.

Two sample t tests were used to compare differences in mean daytime, nighttime and overall 24 hours ambulatory SBPs in the two study groups. Daytime hours were defined as 06:00-22:00 and nighttime hours from 22:00–06:00. Chi-square tests were used to compare control rates at baseline and 6 months, with controlled ambulatory SBP defined as below135 mm Hg for daytime, below 120 mm Hg for nighttime and below 130 mm Hg for the overall 24-hour period.23 Mean changes in ambulatory BP from baseline to 6 months within groups were compared with paired t-tests.

Drug therapy changes were grouped into 6 categories: diuretic added, non-diuretic added, switch within same class, dose increased, dose decreased, and drug discontinued. The frequency of drug changes in each category was calculated for the baseline to 1 month, 1 month to 3 month, and 3 to 6 month time periods. Differences in frequency of changes between the co-managed and control groups were compared using Chi square tests. We further performed two sample t tests to compare the ambulatory BPs for those subjects who were not on a diuretic at baseline but had a diuretic added at one of the three time periods (baseline to 1 month, 1 month to 3 month, 3 to 6 month) with those who were not on a diuretic at baseline and never had a diuretic added at any period during the trial. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

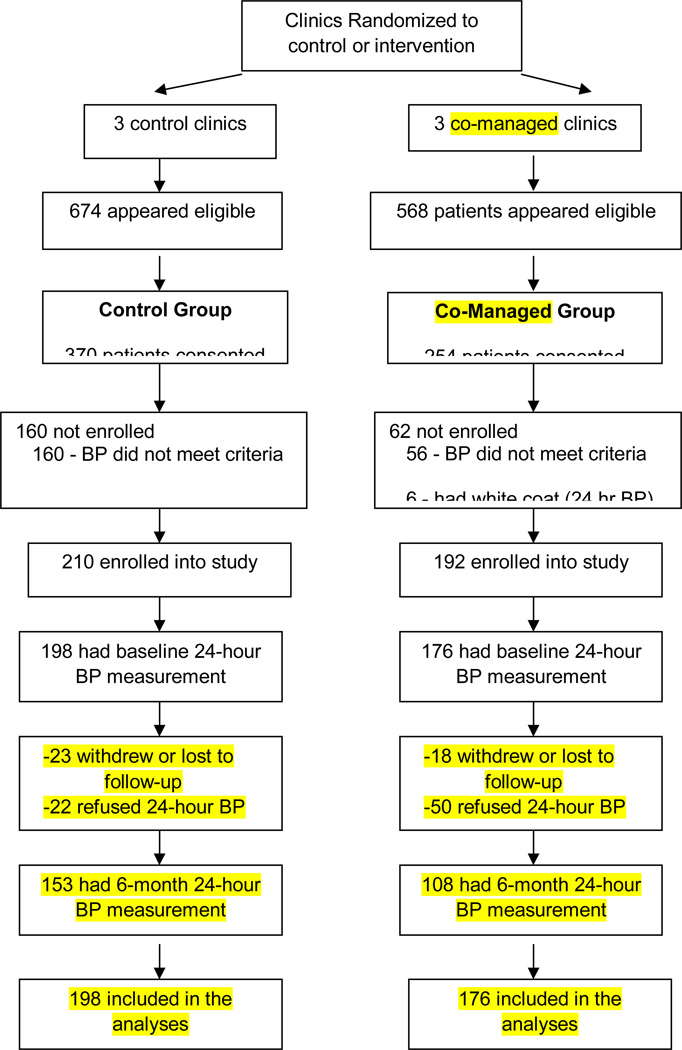

A total of 402 subjects were enrolled in the main study. Baseline ambulatory BP measurements were obtained from 198 control and 176 co-managed subjects (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic data. Compared with co-managed subjects, those in the control group were significantly less likely to be married (p<.001); they were significantly more likely to have diabetes (p<.001), or a history of myocardial infarction (p<.001), they had significantly more coexisting conditions (p<.001), and they were significantly more likely to have an annual household income below $25,000 (p<.001) and to self-pay for their care (p<.001). Despite these imbalances, there was no significant difference between groups for either mean baseline ambulatory BP measurement or in the percent of subjects with controlled baseline ambulatory pressures (Table 2). In the main study cohort previously reported, clinic BP was controlled in significantly more subjects in the co-managed group (63.9%) than the control group (29.9%) (p<0.001). The odds ratio for controlled BP was 3.2 (95% CI: 2.0, 5.1) after adjustment for covariates.17 Clinic BP was controlled in 32.4% of subjects without diabetes in the control group and 68.8% in the co-managed group (adjusted odds ratio of 3.9; CI: 3.1, 5.0; p<0.001). Clinic BP was controlled in 26.1% and 45.5% of subjects with diabetes in the control and co-managed groups, respectively (adjusted odds ratio of 4.7; CI: 1.7, 13.1; p=0.003).17 These findings suggest that the baseline imbalances between groups did not explain the better BP control in the co-managed group.

Figure 1.

Flow of subjects through the study protocol

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

| Control * | Co-Managed * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (n=198) | (n=176) | P value |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 109 (55.1) | 108 (61.4) | 0.22 |

| Male | 89 (45.0) | 68 (38.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 153 (77.3) | 157 (89.2) | 0.009 |

| African American | 39 (19.7) | 13 (7.4) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Mixed or other | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Age, mean(SD) | 59.4 (14.0) | 57.2 (14.5) | 0.14 |

| Married | 86 (43.4) | 116 (65.9) | <0.001 |

| Education beyond high school | 70 (35.7) | 59 (34.5) | 0.81 |

| Annual household income <$25,000 | 102 (51.8) | 37 (21.4) | <0.001 |

| BMI, mean(SD) | 33.9 (8.7) | 32.1 (6.9) | 0.030 |

| No. of coexisting conditions, mean(SD) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | ||

| Private insurance | 63 (31.8) | 103 (58.5) | |

| Medicare or Medicaid | 81 (40.9) | 62 (35.2) | |

| Self-pay or other | 54 (27.3) | 11 (6.3) | |

| Smoker, within past 15 years | 80 (40.4) | 57 (32.4) | 0.11 |

| >2 Alcoholic drinks per week | 8 (4.3) | 5 (2.9) | 0.46 |

| History of coexisting conditions | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 74 (37.4) | 33 (18.8) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 16 (8.1) | 10 (5.7) | 0.36 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0.50 |

| Myocardial infarction | 13 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

Data are reported as number (percentage) of subjects except as noted.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Table 2.

Comparison of 24-hour systolic blood pressures and control rates at baseline and 6 months

| Daytime |

Nighttime |

Overall 24-Hour |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | 6 months | baseline | 6 months | baseline | 6 months | |

| Mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure* (SD) | ||||||

| Control | 139.9(16.0) | 134.4(17.1) | 129.1(19.0) | 123.7(18.8) | 137.0(16.3) | 131.8(16.9) |

| Co-Managed | 138.9(15.2) | 122.8(15.4) | 126.1(18.3) | 114.8(17.9) | 135.6(15.4) | 120.4(15.3) |

| P value† | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

| Percent of subjects with controlled systolic blood pressures‡ | ||||||

| Control | 38.9% | 57.6% | 37.6% | 48.1% | 35.4% | 50.0% |

| Co-Managed | 40.9% | 79.6% | 39.6% | 67.9% | 39.8% | 75.6% |

| P value § | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.38 | <0.001 |

Data are given as mean (SD) millimeters of mercury.

P value for comparing mean BP between the control group and the co-managed group.

Data are given as the percentage of subjects. Controlled SBP is defined as follows: daytime, lower than 135 mm Hg; nighttime, lower than 120 mm Hg; Overall, lower than 130 mm Hg.

P value for comparing the control rate between the control group and the co-managed group.

At the end of the study, 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements were obtained from 153 control subjects and 108 co-managed subjects (Figure 1). Forty one subjects withdrew before the 6-month final visit (23 control and 18 intervention subjects). In addition, 22 subjects in the control group and 50 in the co-managed group refused to have the follow-up 24-hour monitoring performed. It is not known why more subjects in the co-managed group refused the repeat 24-hour monitoring. While we did not systematically assess these refusals, the most frequently cited reasons given to the research nurses was pain or discomfort that occurred on the baseline monitoring session or the inconvenience of conducting a second 24-hour monitoring session.

The mean number of readings were 19.9 ± 5.4 (range 2–28) per session in the control group and 20.6 ± 4.7 (range 6–41) per session in the intervention group. When considering all time points, 73.3% of subjects had over 20 BP readings per session.

At 6 months, the co-managed group had a significantly lower mean ambulatory BP across all the three time periods (daytime, nighttime, and overall 24-hour) compared to the control group (Table 2). Mean (SD) overall ambulatory SBP decreased from 135.6 (15.4) mm Hg to 120.4 (15.3) mm Hg in the co-managed group and from 137.0 (16.3) mm Hg to 131.8 (16.9) mm Hg in the control group (p<.001 for between-group comparison of 6 month BPs). The reduction in 24-hour SBP values (15.2 in the co-managed group versus 5.2 in the control group) was consistent with the previously reported reduction in office-based research SBP values (20.7 in the co-managed group versus 6.8 in the control group).17 The above analyses were based on imputing the clinic mean values at 6 months for missing data for both the control and co-managed groups. In the second, more conservative analysis where we imputed baseline BP values for missing data in the intervention group but clinic mean BP in the control group, the results remained statistically significant. In this analysis, mean (SD) for overall SBP decreased from 135.6 (15.4) mm Hg to 127.1 (17.3) mm Hg in the co-managed group and from 137.0(16.3) mm Hg to 131.8 (16.9) mm Hg in the control group (p= 0.009 for between-group comparison of 6 month BPs).

Similarly, ambulatory BP control rates at 6 months were significantly higher in co-managed versus control subjects for all periods (daytime, nighttime, and overall 24-hour). In particular, the control rates for ambulatory SBP were 75.6% in the co-managed group versus 50.0% in the control group (p<.001 for between-group comparison).

A total of 467 drug therapy changes were initiated by either the pharmacist or physician in the co-managed group, with the largest number occurring from baseline to the first month (54.4%). The mean number of anti-hypertensive medications increased over the 6 month trial from 1.3 to 2.3 in the co-managed group and from 1.9 to 2.2 in control subjects (p<.001 for the comparison of increase in number of antihypertensives). In addition, significantly more drug changes occurred in the co-managed group than in the control group (mean 2.7 versus 1.1, respectively, p<.001 for between-group comparison). During the trial, intervention clinic pharmacists made a total of 368 recommendations for changing anti-hypertensive drug regimens, and 95% of the pharmacist recommendations were accepted and implemented by physicians.

Table 3 summarizes the specific drug therapy changes during the trial. A significantly greater percent of co-managed subjects had a diuretic added (41.5% vs 15.2%, p<0.001), a non-diuretic drug added (64.8% versus 20.2%, p<0.001), a dose increased (55.7% versus 30.8%, p<0.001), or a dose decreased (15.9% versus 5.1%, p<0.001) over the 6 months. While a similar percentage of subjects in both groups were taking a diuretic at baseline, significantly more co-managed subjects were taking a diuretic (79.6% versus 62.6%, p<0.001) or chlorthalidone (7.4% versus 0%, p<0.001) at 6 months (Table 4).

Table 3.

Percent of subjects with specific antihypertensive medication changes from baseline to the 6 months

| Percent of subjects |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Managed (n=176) |

Control (n=198) |

P value | |

| Diuretic added | 41.5 | 15.2 | <0.001 |

| Non-diuretic drug added | 64.8 | 20.2 | <0.001 |

| Dose increased | 55.7 | 30.8 | <0.001 |

| Dose decreased | 15.9 | 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Drug discontinued | 18.2 | 10.1 | 0.024 |

| Switch within class | 6.8 | 2.0 | 0.022 |

Table 4.

Antihypertensive medication use at baseline and 6 months

| Percent of subjects |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

6 months |

|||

| Co-Managed (n=198) |

Control (n=176) |

Co-Managed (n=198) |

Control (n=176) |

|

| Medication class | ||||

| Diuretics | 47.7 | 54.0 | 79.6* | 62.6 |

| Beta Blockers | 28.4 † | 39.9 | 42.1 | 47.0 |

| ACE Inhibitors | 25.0* | 46.5 | 51.1 | 51.5 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 13.1 ‡ | 24.8 | 33.0 | 29.3 |

| Alpha Blockers | 0.6 ‡ | 5.6 | 0.0 ‡ | 5.6 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 9.1 | 10.1 | 11.9 | 10.1 |

| Centrally Acting Alpha Blockers | 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 3.0 |

| Vasodilators | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Aldosterone Receptor Blockers | 0.6 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 1.0 |

P<0.001

P<0.05

P<0.01

Among the study subjects who were not on a diuretic at baseline (n=161), the 6-month ambulatory SBPs (daytime, nighttime, and 24-hour) were significantly lower for those who had a diuretic added between baseline and 1 month and continued it throughout the remainder of the study compared with those who never had a diuretic added (Table 5). Mean (SD) overall ambulatory SBP decreased from 134.2 (15.0) mm Hg to 127.4 (17.1) mm Hg in the no diuretic-added group and from 135.4 (14.2) mm Hg to 119.2 (13.1) mm Hg in diuretic-added group (p=0.002 for between-group comparison of 6 month BPs). When all subjects who had a diuretic added at any time point are combined, a significant difference was detected in nighttime and overall 24 hour BPs, even though the two groups had similar ambulatory SBPs at baseline.

Table 5.

The effect of adding diuretic on ambulatory blood pressure measurement *

| Daytime |

Nighttime |

Overall 24 hours |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | 6-months | baseline | 6-months | baseline | 6 months | |

| No diuretic | 137.1(15.8) | 129.6(18.3) | 126.5(16.2) | 121.7(17.0) | 134.2(15.0) | 127.4(17.1) |

| added | ||||||

| (n=89) | ||||||

| Diuretic added | 138.9(14.0) | 122.5(12.9) † | 126.7(15.9) | 111.8(15.6)‡ | 135.4(14.2) | 119.2(13.1) |

| 1st period | ||||||

| (n=57) | ||||||

| Diuretic added | 151.4(14.4)§ | 135.5(17.3) | 140.0(17.3)§ | 123.9(17.0) | 148.7(13.0)† | 133.3(16.0) |

| 2nd period | ||||||

| (n=8) | ||||||

| Diuretic added | 150.5(18.5)§ | 132.3(17.5) | 134.4(25.0) | 124.3(18.7) | 145.2(20.1) | 129.4(18.1) |

| 3rd period | ||||||

| (n=7) | ||||||

| Diuretic added | 141.4(15.1) | 124.9(14.5) | 128.6(17.4) | 114.2(16.5)† | 137.8(15.3) | 121.8(14.6)§ |

| any period | ||||||

| (n=72) | ||||||

Data are given as mean (SD) millimeters of mercury. First period is defined as from baseline to the first month, second period is defined as from first month to 3-months, and third period is defined as from 3 months to 6 months. P value for comparing mean BP between diuretic added (at each time period) group and the no diuretic added group.

P<0.01,

P<0.001,

P<0.05

Discussion

This study confirms the results of a previous study, conducted in a smaller number of subjects, that evaluated the impact of physician-pharmacist co-management of hypertension on ambulatory 24-hour BP control.20 To our knowledge, these are the only two studies of team-based care that confirmed the clinic-based BP results with 24-hour BP measurements. The present study is unique because we evaluated the relationship of drug therapy changes to 24-hour BP changes. This study found lower ambulatory SBPs across the daytime, nighttime and 24-hour periods and higher achievement of ambulatory BP control for subjects in the co-managed group compared to the control group. Our findings suggest that physician-pharmacist collaborative care is an effective strategy to improve BP management throughout the 24 hour period.

The mean number of antihypertensive medications in the two study groups was similar at the end of the study (2.2 in the control group vs. 2.3 in the co-managed group). However, subjects in the co-managed group had better BP control. It is possible that the clinical pharmacists suggested different antihypertensive medications that led to better BP control in the co-managed group such as more long-acting medications. Alternatively, the results may be due to higher doses being recommended by the pharmacists. Only the use of diuretics changed significantly from baseline which led to significant differences between groups at the end of study. Of note, a significantly higher proportion of co-managed subjects (7.4%) received chlorthalidone compared with control subjects (0.0%, p<0.001) at 6 months. Among the subjects who were not on a diuretic at baseline, the daytime, nighttime, and overall 24-hour ambulatory BPs were consistently lower at 6 months for subjects who had a diuretic added during the first month compared with subjects who never had a diuretic added. Also, when all subjects who had a diuretic added at any time point were combined, a significant difference was detected in the 6 months nighttime and overall 24-hour BPs. This finding suggests that diuretics are important in the treatment of hypertension especially to achieve 24-hour BP control.

Clinical pharmacists are highly utilized in primary care clinics within managed care clinics, Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, academic health centers, the Indian Health Service and many other settings.24 While uncommon, clinical pharmacists are increasingly being included in larger private practice offices. Changes in healthcare delivery and payment structures implemented with healthcare reform will make team-based models more feasible.

It is interesting to note the relatively high utilization of beta blockers in both study groups (Table 4). In a recent editorial, Dr. Michael Weber highlighted several studies that also found high rates of beta blocker use.25 Axon and colleagues evaluated antihypertensive drug use in 5668 inpatients and found 61% received beta blockers while only 39% received ACE inhibitors.26 Other agents were used far less frequently. The authors theorized that the high use of beta blockers may have been due to high rates of coronary artery disease or other co-existing conditions. The reason for high utilization of beta blockers in the present trial is not known since few subjects had heart failure or a previous MI. As noted by Dr. Weber, it would be interesting to determine why physicians, and presumably clinical pharmacists, are using beta blockers so frequently when there are no compelling reasons to do so unless there are co-morbidities such as coronary artery disease. 25

This study had several limitations. The small number of randomized clinics likely led to unevenness in the two study groups. The control group had greater minority subjects, lower income, and more coexisting conditions, including diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction, each of which might increase the difficulty of achieving controlled BP. However, when we controlled for all covariates there was still significant differences in favor of the co-managed group.17 In addition, the present analyses demonstrated similar baseline 24-hour BP values in the two groups. This imbalance occurred, in part, because of the cluster-randomized nature of the study in which the clinics were randomized. This design was a requirement of the NIH study section that reviewed the original grant application. This study resulted from a grant for a request for applications (RFA) on behavioral interventions to improve guideline adherence. Unlike blinded drug trials, randomization at the patient level for a behavioral intervention directed at patients and physicians would have led to physicians in both the control and co-managed group which would have contaminated the intervention. Physicians frequently covered for one another in these offices, so randomization at the physician level would also have been contaminated. Ideally, cluster-randomized designs should include at least 10 clinics, and ideally more. Because this study was in response to an RFA, the duration and budget would not allow for more than 6 offices. However, because of these limitations and the results from this study, an ongoing study of implementation of this intervention model is being conducted in 32 primary care offices throughout the United States. That trial enrolled the last patient in March 2012, and final results should be known by late 2014.27

Second, we eliminated the data for the subjects with missing baseline ambulatory 24-hour BP values. We also modeled the missing 6-month ambulatory BP values with the mean clinic ambulatory BP in our first analyses which could potentially bias in favor of the intervention group. However, we conducted a second, more conservative, analysis in which we imputed uncontrolled baseline values for missing data in the co-managed group but lower (better) 6-month BP values were used for missing data in the control group. This approach should have biased in favor of the control group. Even so we still found significantly greater improvement in the co-managed group compared with the control group suggesting the findings are robust.

A final limitation is the generalizability of our study. Our findings can only be applied to community-based family clinics that have existing clinical pharmacists who work directly with their physician colleagues. Also, our findings are only generalizable to motivated subjects who participated in the 24-hour monitoring sessions.

Conclusion

Physician-pharmacist co-managed subjects with uncontrolled hypertension achieved significantly better mean ambulatory BP and higher BP control rates during the daytime, nighttime and overall 24-hour periods compared with a control group. Anti-hypertensive drug therapy was intensified significantly more frequently for the subjects in the physician-pharmacist collaborative management group compared to control group subjects.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Funding for this project was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL069801 and HL070740.

Drs. Carter is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Centers for Education and Research on Therapeutics Cooperative Agreement #5U18HSO16094 and the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE), Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (HFP 04-149). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. All of the authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Portions of this paper were presented in the Midwest Social and Administration Pharmacy Conference, Madison, Wisconsin, August 9, 2012.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yoon PW, Gillespie CD, George MG, Wall HK Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Control of hypertension among adults--national health and nutrition examination survey, United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;(61 Suppl):19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:948–954. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed June 24, 2011];Healthy People 2020: Heart Disease and Stroke. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HP2020objectives.pdf.

- 7.Rudd P, Miller NH, Kaufman J, et al. Nurse management for hypertension. A systems approach. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:921–927. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borghi C, Cicero AF. Hypertension: Management perspectives. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:1999–2003. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.708733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter BL, Barnette DJ, Chrischilles E, Mazzotti GJ, Asali ZJ. Evaluation of hypertensive patients after care provided by community pharmacists in a rural setting. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:1274–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zillich AJ, Sutherland JM, Kumbera PA, Carter BL. Hypertension outcomes through blood pressure monitoring and evaluation by pharmacists (HOME study) J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1091–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson SR, Slaughter R, Halapy H. Pharmacists' ability to influence outcomes of hypertension therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:140–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vivian EM. Improving blood pressure control in a pharmacist-managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:1533–1540. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.17.1533.34127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2563–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon DK, Portner TS, Bass GE, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes in the hypertension and COPD arms of a multicenter outcomes study. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 1998;38:574–585. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borenstein JE, Graber G, Saltiel E, et al. Physician-pharmacist comanagement of hypertension: A randomized, comparative trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:209–216. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.2.209.32096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter BL, Bergus GR, Dawson JD, et al. A cluster randomized trial to evaluate physician/pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:260–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1996–2002. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh JM, McDonald KM, Shojania KG, et al. Quality improvement strategies for hypertension management: A systematic review. Med Care. 2006;44:646–657. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000220260.30768.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter BL, Rogers M, Daly J, Zheng S, James PA. The potency of team-based care interventions for hypertension: A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1748–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber CA, Ernst ME, Sezate GS, Zheng S, Carter BL. Pharmacist-physician comanagement of hypertension and reduction in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1634–1639. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milchak JL, Carter BL, Ardery G, et al. Development of explicit criteria to measure adherence to hypertension guidelines. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:426–433. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ardery G, Carter BL, Milchak JL, et al. Explicit and implicit evaluation of physician adherence to hypertension guidelines. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickering TG, White WB American Society of Hypertension Writing Group. ASH Position Paper: Home and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: when and how to use self (home) and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:850–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter BL, Bosworth HB, Green BB. The Hypertension team: The role of the pharmacist, nurse, and teamwork in hypertension therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14:51–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber MA. How well do we care for patients with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14:737–743. doi: 10.1111/jch.12022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axon RN, Nietert PJ, Egan BM. Antihypertensive medication prescribing patterns in a university teaching hospital. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2010;12:246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter BL, Clarke W, Ardery G, et al. A cluster-randomized effectiveness trial of a physician-pharmacist collaborative model to improve blood pressure control. Circulation: Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:418–423. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.908038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]