Abstract

Diabetes education for ethnic minorities should address variations in values underlying motivations, preferences, and behaviors of individuals within an ethnic group. This paper describes the development and implementation of a culturally tailored diabetes intervention for Puerto Rican Americans that can be delivered by a health care paraprofessional and implemented in routine clinical care. We describe a formative process, including interviews with providers, focus groups with patients and a series of multidisciplinary collaborative workshops used to inform intervention content. We highlight the intervention components and link them to a well-validated health behavior change model. Finally, we present support for the intervention’s clinical effects, feasibility, and acceptability and conclude with implications and recommendations for practice. Lessons learned from this process should guide future educational efforts in routine clinical care.

Keywords: Culturally tailored, diabetes, behavior change, primary care, Puerto Rican

Ethnic minorities in the U.S. have higher rates of diabetes (CDC, 2003, 2004), are less likely to perform diabetes self-care activities (Heisler et al., 2007; Levine et al., 2009; Nwasuruba, Osuagwu, Bae, Singh, & Egede, 2009), and have worse control of their diabetes compared to Whites (Egede, Mueller, Echols, & Gebregziabher, 2010; Fan, Koro, Fedder, & Bowlin, 2006; Heisler, et al., 2007). Among Hispanic Americans with diabetes, culture and language barriers have been associated with poor diabetes self-care activities and health outcomes (Eamranond et al., 2009; Fitzgerald, Damio, Segura-Perez, & Perez-Escamilla, 2008; Kandula et al., 2008; Mainous, Diaz, & Geesey, 2008; Mainous et al., 2006). However, the effect of interventions that address cultural and language barriers have produced mixed support (Castillo et al., 2010; Hawthorne, Robles, Cannings-John, & Edwards, 2008; Sarkisian, Brown, Norris, Wintz, & Mangione, 2003; Sixta & Ostwald, 2008). For instance, Sixta and Oswald (2008) found improvements in diabetes knowledge, but not in glycemic control; Castillo et al.’s (2010) found improvements in knowledge, self-care behaviors, and glycemic control, whereas Rosal et al. (2005) found improvements in glycemic control, but not self-care behaviors.

While many diabetes interventions for Hispanics report improvements in diabetes knowledge, behavioral outcomes, and clinical outcomes, improvements are often modest and attrition is moderate to high in most studies (Whittemore, 2007). This might be because most interventions have been atheoretical, implemented in community settings with inconsistent access to participants, group–based and thus generalized to all members of an ethnic group (Hawthorne, Robles, Cannings-John, & Edwards, 2010; Sarkisian, et al., 2003). Few interventions have been theoretically grounded, implemented within routine clinical care, and tailored to an individual within an ethnic group (Christian et al., 2008; Osborn et al., 2010). More commonly, routine clinic-based education involves ad hoc efforts from physicians who rarely assess patient recall or comprehension of new concepts (Schillinger et al., 2003), or deliver culturally appropriate health messages in patients’ native language (Lopez-Quintero, Berry, & Neumark, 2009). Training a health care paraprofessional (e.g., certified medical assistant, medical technician) to deliver a theoretically grounded intervention for diverse patient populations might be a critical step forward in identifying the most cost-effective, yet well-accepted strategies to promote diabetes self-care among high risk ethnic minority groups (Osborn, Amico, Cruz, et al., 2010; Osborn & Fisher, 2008).

The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model is a theoretical model (W. A. Fisher, Fisher, & Harman, 2003) that has been empirically supported in characterizing self-care activities among racially and ethnically diverse persons with diabetes (Osborn, Amico, Fisher, Egede, & Fisher, 2010; Osborn & Egede, 2010), and has demonstrated success as the underpinning of a culturally tailored clinic-based self-care intervention for Puerto Ricans with diabetes (Osborn, Amico, Cruz, et al., 2010). This paper describes the development and implementation of the aforementioned intervention, including the formative process that informed intervention design and content; descriptions of the intervention components; the intervention’s clinical effects, feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability; and the lessons learned.

Formative Process

The IMB model specifies a series of steps that are required in the development of an intervention, which includes formative work to fully explore the kinds of information, motivation, and behavioral skills barriers and facilitators of behavior that are critical in the priority patient population. This approach places each of the IMB constructs in the cultural context in which a behavior must be negotiated and, subsequently, improved. We sought to develop a culturally tailored clinic-based intervention for Puerto Rican Americans with Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) receiving care at an urban outpatient clinic in the Hartford, CT area. To achieve this, we interviewed providers and conducted focus groups with patients to identify patients’ IMB model-based barriers to healthy eating and physical activity within the cultural and local beliefs and resources in the surrounding area.

Provider Interviews

Investigators approached the clinic about the project as opposed to vice versa. Senior author JDF established a professional relationship with a clinic administrator (author SAW) who arranged initial meetings between the principal investigator (author CYO) and three providers caring for a large percentage of the Puerto Rican patients with diabetes. All three providers were contacted (i.e., a dietician and diabetes educator, physician, and lay health care paraprofessional) and invited to meet with CYO on an individual basis to discuss the scope of the diabetes problem within the local Puerto Rican community and current clinic efforts to ameliorate it. All agreed to an individual meeting, and CYO who worked with each provider to schedule a convenient time to discuss these issues.

Each provider voiced concern about the high rates of diabetes, diabetes-related hospitalizations, complications, and mortality among their Puerto Rican patients. Providers attributed these outcomes to the Puerto Rican population’s widespread obesity problem, poor eating habits, physical inactivity, and a host of patient-specific barriers (e.g., low educational attainment, low incomes, depression, and chronic stress), cultural barriers (e.g., preoccupation with family needs and stressors, prioritizing the family over one’s health), and community barriers (e.g., minimal access to affordable healthy foods and safe places to be active) that interfere with diabetes self-care.

At the time of these initial meetings, Puerto Rican residents made up 33% of Hartford’s population ("U.S. Census Bureau: Hartford City, Connecticut Statistics and Demographics," 2000), and approximately15% had diabetes (McLaughlin, Maljanian, & McCormack, 2003). Consistent with provider comments, in CT, Hispanics with diabetes in were twice as likely to be hospitalized, and, as a whole, had a 60% higher diabetes induced mortality rate compared to White with diabetes (Connecticut Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2005).

Next, CYO met with each provider to solicit support for a culturally tailored clinic-based intervention, and get feedback on IMB model-based barriers to diabetes self-care reported in the research literature. Each provider vocalized support for the intervention, viewing it as an important service and believed it would offer supplemental opportunities for tertiary prevention in the clinic. Providers also offered views on potential IMB model-based barriers to diabetes self-care occurring in the Puerto Rican patients they serve. This latter feedback was incorporated into both the design and content of the intervention.

Patient Focus Groups

In addition to detailed interviews and discussions with providers, we conducted focus groups with Puerto Rican American patients with diabetes to understand their IMB model-based barriers to healthy eating and physical activity. A bilingual clinic staff member of Puerto Rican ethnicity approached patients in clinic waiting rooms or called patients listed on a diabetes class roster, and invited them to participate in a discussion about diabetes. Of the 25 patients who were approached or contacted by phone, 19 agreed to participate and were scheduled, and 14 participated (74% of those contacted). Discussions explored the relative influence of diabetes-related information, motivation, and behavioral skills on patients’ eating behaviors and physical activity levels. Additionally, we discussed aspects of the culturally tailored intervention that would be well-matched or, alternatively, poorly matched, to the unmet needs and resources of Puerto Rican Americans with diabetes in this geographic area.

Focus group sessions were audiotaped and then reviewed using the method of analytic induction and comparative analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) to find common patterns. Analytic induction involves scanning focus group data for themes or categories, developing a working scheme after examination of initial cases, and then modifying the scheme on the basis of subsequent cases (Goetz & LeCompte, 1981). Negative instances that do not fit the initial constructs are sought to expand, adapt, or restrict the original construct. Findings from patient focus group sessions revealed important diabetes self-care information, motivation, and behavioral skills deficits and reports of poor eating habits and physical inactivity among diabetes patients.

Patient reports from these sessions supported a potential role for IMB model-based intervention content. Specifically, misinformation appeared common--such as adopting the belief that only foods with sugar must be controlled (not starchy foods common in the Puerto Rican diet in this region), and that diet without physical activity is enough to manage diabetes. In terms of motivation, patients felt challenged in maintaining consistent motivation towards and commitment to healthy eating and being physically active. Behavioral skills that appeared lacking included how to read food labels, managing portion sizes, and how to remain committed to behavior change across a range of situations. Even in these small groups, there was variability in terms of patient-specific cultural barriers and skills deficits, further supporting the need for culturally tailored strategies that target individual members within in an ethnic group.

Intervention Development

A collaborative working group of six investigators, eight clinic providers and four clinic staff members was created to develop, implement, and evaluate the culturally tailored clinic-based intervention. Investigators included two social/health psychologists and two clinical/health psychologists with expertise in designing and evaluating IMB model-based interventions, a nutrition scientist with expertise in Hispanic health, and a scientist with expertise in measurement and intervention evaluation. Clinic collaborators included an administrator and physician scientist with expertise in diabetes education intervention research, six dietician interns, and a registered dietician (RD) and certified diabetes educator (CDE) of Puerto Rican ethnicity. Clinic staff members included two certified medical assistants (CMA) and two research assistants, all of Puerto Rican ethnicity.

To form a starting place for developing the intervention, collaborators held a series of meetings to share their views on what appeared to be promising with respect to improving healthy eating and physical activity in their areas of expertise. Discussions following these presentations identified what IMB elements the intervention should target, and confirmed our belief that developing a culturally tailored intervention using the IMB model would be viable. For each intervention component defined by consensus, we outlined the necessary IMB model-based content to include in the cultural context of a Puerto Rican patient population, mapping provider interview and patient focus group findings onto each content area, and paying particular attention to linking each component to pre-specified behaviors and glycemic control.

Prior to these development meetings, author SCK had found that a brief, tailored, 90-minute, single session IMB model-based intervention delivered by a desktop flip chart in a clinic setting effectively reduced HIV risk behaviors among patients receiving care for an STI (Kalichman et al., 2005). While recognizing HIV risk reduction behaviors and diabetes self-care behaviors are not synonymous, we wanted our diabetes intervention to be brief, integrated into a busy clinic setting, theoretically based on the IMB model, and individually tailored. This was our rationale for adopting the same intervention structure (i.e., a single 90-minute individualized session), and using an illustrative desktop flipchart available in English and Spanish (Puerto Rican dialect) to promote two diabetes self-care behaviors (i.e., healthy eating and physical activity). A first draft of the flipchart and other intervention materials were presented to collaborating providers who made recommendations for changes to materials before final versions were processed. The intervention was then examined for clarity, continuity, and flow by conducting role-play mock demonstrations with research assistants as standardized patients.

Intervention Implementation

Intervention Training

The intervention was implemented by a trained, bilingual, CMA of Puerto Rican ethnicity who had received ~40 hours of training in nutrition and physical activity, the IMB model, motivational interviewing (MI) (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), safety, ethics, and intervention activities from an RD and CDE of Puerto Rican ethnicity (NC) and a social/health psychologist with expertise in health behavior change (CYO). Training activities included didactic sessions, reading materials, videos, role playing, and individual practice with feedback, focused on skill building to minimize the use of complex medical terms, and maximize the use of simple, plain language, and confirming patient understanding through teach-to-goal educator-patient interactions (Osborn, Cavanaugh, & Kripalani, 2010). The training objectives modeled the general lines of a successful protocol used in previous IMB model-based interventions (J. D. Fisher, Fisher, & Misovich, 1997). Throughout the training, the CMA was given feedback and suggestions for improvement to ensure desired effectiveness criteria were met.

IMB model-based intervention components

The CMA used a flipchart to guide the session (see Table 1 for an overview of all content). The session began with a 5-minute introduction, welcoming the patient; communicating the session goals, objectives, and assurances of confidentiality; learning the patient’s motives for attending the session, and providing positive reinforcement for his/her presence and participation.

Table 1.

Flipchart content used to guide the culturally-tailored session.

| Description | IMB Elements |

|---|---|

| Introductions | |

| Welcome the patient, and provide a brief introduction and timeline to the session. | Information |

| Briefly Describe The Problem | |

| Begin with the diabetes prevalence among Puerto Ricans living in the local community. | Information |

| Explain what diabetes complications are and the importance of blood glucose control. | Information |

| Provide Personal Feedback | |

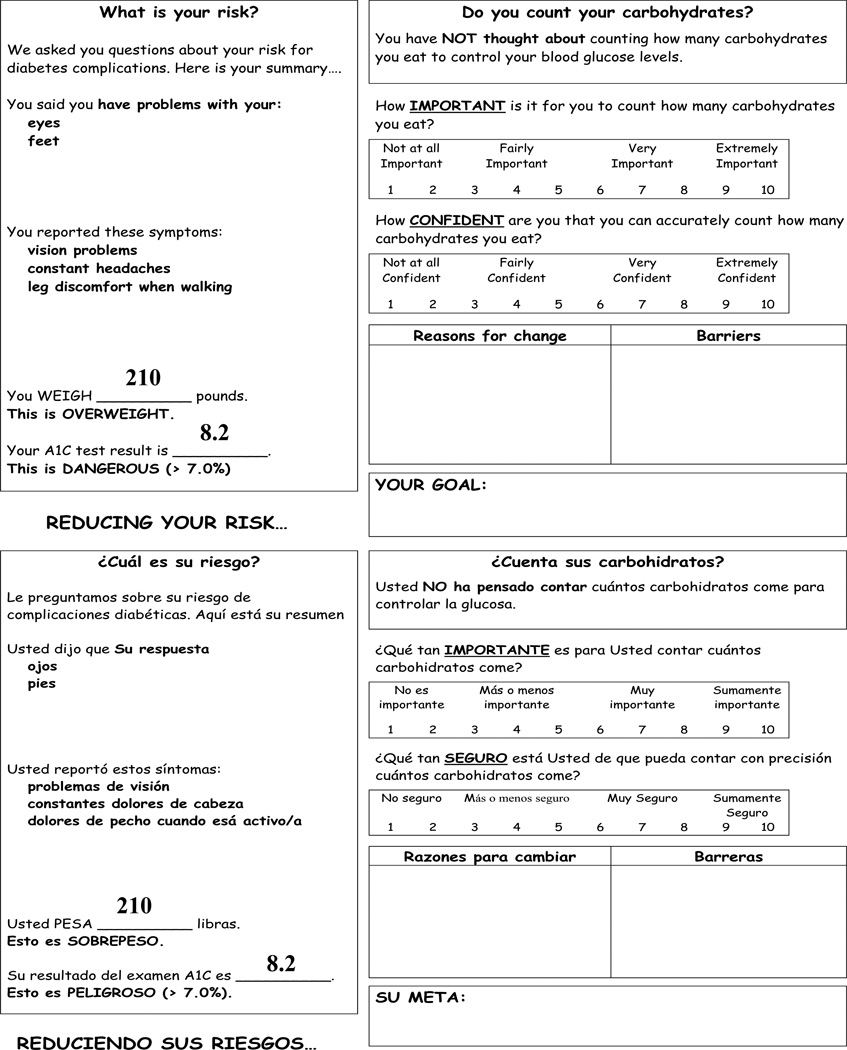

| Review the patient’s risk for diabetes complications (see Figure 1). | Motivation |

| Describe the Cause of Diabetes Complications | |

| Explain the relationship between carbohydrate consumption and high blood glucose levels. | Information |

| Provide Personal Feedback | |

| Provide personal feedback to increase patient awareness of his/her carbohydrate counting practices, “This best describes you…” section on the feedback report (see Figure 1). |

Motivation |

| Introduce two scaling questions to elicit a discussion about the patient’s perception of the importance of behavior change, and lead into a dialog about the reasons for change (see Figure 2). |

Motivation |

| The second scaling question documents the patient’s perceived self-efficacy and serves as an open discussion of the barriers and consequences of change (see Figure 1). |

Motivation |

| Encourage patient to think of ways to remove these barriers; support the patient in building self-efficacy (see Figure 1). |

Motivation & Behavioral Skills |

| Nutritional Education | |

| Explain the three nutrients in foods (protein, fat, carbohydrates). | Information |

| Explain the association between carbohydrates and blood glucose control. | Information |

| Present a list of foods; have the patient identify foods with carbohydrates; review, and repeat. | Behavioral Skills |

| Explain carbohydrate counting. | Information |

| Present Individualized Meal Plan | |

| Describe how many carbohydrates the patient should eat at each meal; discuss his/her recommended # of grams and # of choices, and the difference between grams and choices (see Figure 2). |

Information |

| Help patient identify culturally familiar foods consistent with his/her meal plan, emphasize the patient’s options, assist him/her in making choices; guide and create an environment for the patient to feel empowered (see Figure 2). |

Motivation & Behavioral Skills |

| Nutrition Facts Labels | |

| Instruct on the 3 steps to reading carbohydrate content on food labels; have the patient practice 3 steps with culturally familiar foods, and using English and Spanish food labels |

Behavioral Skills |

| Serving Size and Portion Control | |

| Review the importance of eating the right serving size amounts of foods. | Information |

| Demonstrate portion control techniques; and have patient practice these techniques | |

| •Measuring cups and spoons | Behavioral Skills |

| •Plate method – filling plates, bowls, cups | Behavioral Skills |

| •Hand/fist method (e.g., palm of hand = 3 ounces of meat) | Behavioral Skills |

| •Visualizing objects (e.g., deck of cards = 3 ounces of meat) | Behavioral Skills |

| Goal Setting (Carbohydrate Counting) | |

| Help patient develop a behavior change plan that includes a goal and action steps that require the patients to address ways to remove the barriers identified earlier. |

Motivation |

| The motivation segment will conclude with a summary of the information gained in this section. |

Information & Motivation |

| Exercise Education | |

| Explain the association between physical inactivity and diabetes complications. | Information |

| Provide Personal Feedback | |

| Present personal feedback to increase patient awareness of his/her physical activity levels. | Motivation |

| Introduce two scaling questions to elicit a discussion about the patient’s perception of the importance of behavior change, and lead into a dialog about the reasons for change. |

Motivation |

| The second scaling question documents the patient’s perceived self-efficacy and serves as an open discussion of the barriers and consequences of change. |

Motivation |

| Encourage patient to think of ways to remove these barriers; support the patient in building self-efficacy. |

Motivation |

| Exercise Education cont. | |

| Discuss the benefits of physical activity for individuals with diabetes. | Information & Motivation |

| Discuss the general benefits of physical activity. | Information & Motivation |

| Lifestyle Activity | Information & Motivation |

| Explain the benefits of adding additional speed and movement to everyday activities | Information & Motivation |

| Have the patient identify ways to increase his/her lifestyle activity | Behavioral Skills |

| Goal Setting (Physical Activity) | |

| Help patient develop a behavior change plan that includes a goal and action steps that require the patients to address ways to remove the barriers identified earlier. |

Motivation |

| The motivation segment will conclude with a summary of the information gained in this section. |

Information & Motivation |

Note: IMB = Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills.

Information

The CMA then “localized” the seriousness of diabetes as a problem by presenting the local (city) and statewide prevalence rates of diabetes among Puerto Rican residents. In an effort to enhance basic diabetes knowledge (or information) the CMA asked questions to get a sense of the patient’s current understanding of diabetes (e.g., “What causes high blood sugars?”) and, when necessary, dispelled commonly held myths by providing the correct answer using plain language. To enhance diet- and exercise-specific information, patients were taught what types of culturally familiar foods raise blood glucose levels and the importance of monitoring carbohydrate intake and controlling portion sizes throughout the day for glycemic control, and how lifestyle activity (e.g., house or yard work, walking to the market) can replace traditional, regimented exercise; and the impact of performing these behaviors on glycemic control and, in turn, one’s risk for diabetes-related complications.

Motivation

The CMA used motivational interviewing (MI) strategies to deliver tailored content and enhance the patient’s motivation to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Following the principles of MI, the CMA presented the patient’s personal risk for diabetes-related complications (see Figure 1 for a sample tailored feedback report that contained critical data gathered prior to the session; e.g., patient-specific self-care activities, diabetes-related symptoms, weight, and glycemic control [HbA1c]), assessed the patient’s behavior change importance and confidence ratings; and helped the patient identify reasons to change, barriers to change, and set a realistic behavior change goal.

Figure 1.

Personal Feedback Report available in English and Spanish (front page only).

Note. The left side contains patient-specific data gathered prior to the session. During the session, a certified medical assistant presents this to each patient; assesses the patient’s importance and confidence ratings; and helps the patient identify reasons to change, barriers to change, and set a realistic behavior change goal. The aforementioned data is documented during the session on the right side of the report. A copy is given the patient at session end.

Throughout the intervention, the CMA asked simple open-ended questions to encourage exploration and decision-making on the part of the patient. The CMA also asked open-ended questions designed to help the patient identify, verbalize, and reinforce his/her positive attitudes and/or subjective normative support for healthy eating and being physically active.

The CMA used reflective listening to learn what has and has not helped the patient change his/her behavior in the past. An example of reflective listening to promote healthy eating was, "You are not quite sure you are ready to change the way you eat, but you are aware that your blood sugar has been high recently, and that your family is worried about your health." A reflection such as this was used to identify and/or reinforce subjective normative support for eating better. Summaries, a form of reflective listening that reflects back what a patient said, were used to communicate interest in the patient, build rapport, and call attention to elements of the discussion that might serve to promote favorable attitudes towards behavior change. The CMA presented the summary, listed selected elements, and invited the patient to make corrections. An example of a reflective summary was, "Let me stop and summarize what we've just talked about. You are not sure that you want to be here today. You came because your wife wanted you to. At the same time, you've had some nagging thoughts of your own about your health, including your recent weight gain, chronic headaches, and blurry vision. Did I miss anything? I'm wondering what you make of these things." The CMA then listened to the patient’s understanding of the problem. This understanding helped to identify and/or enhance the patient’s existing favorable attitudes and subjective normative support for healthy eating and being more physical activity.

The CMA used affirmations to acknowledge the patient’s strengths in areas of prior failure. For instance, a patient might have tried to adhere to dietary recommendations with limited success, and, as a result, developed unfavorable attitudes about doing so, resulting in low motivation to change. Affirmations were used to convince the patient change was possible and he/she was capable of executing change. Example affirmations were: “You ate smaller portions at lunch for most days this past week. How were you able to do that?” "Every Sunday you walk to church with your granddaughter, and you’ve even done this when you don’t feel well and could easily drive your car. How are you able to do that?" and "You came in today. I'm not sure, but it seems like if you decide something is important enough, you are willing to make it happen." Affirmations such as these were embedded throughout the session to promote favorable attitudes towards improving the patient’s diet and physical activity.

Finally, the CMA worked at each patient’s pace to maximize comprehension and retention of intervention content. This required that the CMA resist the temptation to assume everything the patient heard would be absorbed.

Behavioral skills

A critical intervention feature was the development and distribution of a culturally tailored meal plan booklet (see Figure 2). Before the session, a dietician intern used patient height and weight to calculate caloric needs, establish recommended food servings in a single day, and distribute these values across three meals in the meal plan booklet. During the session, the CMA instructed the patient, and then had the patient “teach-back”, on how to select foods illustrated in the booklet that were consistent with these recommendations.

Figure 2.

Culturally-tailored Meal Plan available in English and Spanish (only Dinner presented as an example).

The CMA also instructed the patient on how to read food labels, monitor carbohydrates, control portion sizes throughout the day, and integrate lifestyle activity into his/her daily life. Patients practiced reading multiple food labels, including some that were culturally-familiar, using “teach-back” to confirm understanding. The CMA presented a variety of portion control strategies (e.g., plate method, measuring cups), and had the patient practice each strategy with food models. Finally, the CMA provided suggestions on how to increase activity by adding speed or additional movement to the patient’s existing behaviors (e.g., house work, walking to the market). The session concluded by having the patient formulate two realistic diet and physical activity goals, and documenting these goals on the patient’s tailored feedback report.

Following the intervention, the CME presented the patient with the tailored feedback report; a brochure of culturally familiar foods with recommended serving sizes; a set of measuring cups; and the culturally tailored meal plan booklet. The CME gave the patient 0–3 handouts to further enhance motivation and behavioral skills for purchasing healthy foods, eating meals throughout the day, and doing affordable, physically safe activities.

Clinical Effects

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial to test the intervention’s effectiveness on adherence to food label reading, diet recommendations, physical activity, and glycemic control (HbA1c) at 3 months post baseline assessment (Osborn, Amico, Cruz, et al., 2010). Patients from an outpatient, primary care clinic at an urban hospital in the northeast U.S. were recruited to participate. Eligibility criteria included: self-identified Puerto Rican ethnicity, age 18 years or older, and a diabetes diagnosis of Type 2 (T2DM) for > 1 year. Clinic staff members identified and contacted 182 eligible patients by phone; 25 patients were unavailable and 28 patients were not interested in participating. Of the remaining 129 patients who were scheduled to participate, 118 arrived at the clinic to complete the baseline assessment and were randomized to condition (i.e., 59 patients were assigned to the intervention group and 59 patients were assigned to the usual care control group). There were no baseline group differences between patients assigned to the intervention versus the usual care control group (Osborn, Amico, Cruz, et al., 2010).

Intervention patients were on average 56.7 years old (SD = 10.1), 73% were female, 73% had less than a high school education of which 51% had never attended high school, 56% were legally disabled and 39% were unemployed, 86% were Spanish speakers, and the average duration living in the U.S. was 25 years (SD = 14.2). Self-rated health was below average, M = 2.4 (SD = 1.6), duration of diabetes was on average 13.1 years (SD = 11.8), and the average HbA1c exceeded the recommended < 7% for diabetes control (M = 7.8, SD = 1.4).

We used ANCOVA models for intent-to-treat analysis with last-observation carried forward. After adjusting for baseline differences on food label reading (Intervention: M = 2.30, SD = 1.31 vs. Control: M = 2.65, SD = 1.42), the intervention group (M = 3.33, SD = 0.14) was reading food labels more than the control group (M = 2.62, SD = 0.14) at 3 months post baseline (p < .001). After adjusting for baseline differences on adhering to diet recommendations (Intervention: M = 3.31, SD = 1.95 vs. Control: M = 3.63, SD = 2.08), the intervention group (M = 4.33, SD = 0.22) was adhering to diet recommendations more than the control group (M = 3.56, SD = 0.22) at 3 months post baseline (p < .01). There were no significant differences between the two groups on adjusted group means for physical activity and HbA1c. However, when using a per protocol approach (N = 91 per protocol; 77% of total randomized sample), after 3 months, the intervention group (n = 48 at follow-up assessment) achieved a statistically significant 0.48% absolute decrease in HbA1c and, compared to the usual care control group (n = 43 at follow-up assessment), achieved a non-significant trend of being more physical activity at 3 months (Osborn, Amico, Cruz, et al., 2010).

Although not reported inOsborn et al. (2010), intervention impact was strongest for individuals with uncontrolled diabetes at baseline (>7% HbA1c, n=29). These patients experienced a 0.80 % absolute reduction in HbA1c, which is closer to the clinically meaningful 1% HbA1c reduction associated with a 21% decreased risk of diabetes-related death, 14% decreased risk of myocardial infarction, and 37% decreased risk of microvascular complications (Stratton et al., 2000), and supports tailoring interventions to individuals within otherwise difficult-to-treat populations. These findings, while promising, are preliminary and should be confirmed in studies with larger samples.

Feasibility

Patients assigned to the intervention arm were scheduled to return within 5 days of the baseline assessment to complete the intervention session. Eleven patients “no showed” to this appointment, but were immediately called, rescheduled for another day, and arrived at their next appointment. Thus, all 59 patients attended the intervention session (100% response rate) within one month’s time, with an average time between baseline to intervention of 2.5 days (range: 1–7). Only 4 patients completed the session after the 5-day window). Patients had the option to receive the intervention in English or Spanish, and all preferred Spanish.

The costs to deliver the intervention included the cost of supplies (initial point-of-care HbA1c tests [~$590], printing and binding [~$160], food model kit [one time purchase ~$350], plate method kit [one time purchase ~$100], measuring cups [~$300], food labels [free]: ~$1.5K), a CMA’s time (one-time two-week training [~$1.17K] and one month for delivery [~2.33K]: ~$3.5K), and two dietitian interns’ time to calculate daily servings of food per patient (free). Excluding one-time purchases and the one-time CMA training, the cost per patient was ~$57.12.

Clinic demands were twofold: (1) having clinic staff members who were already coordinating care for Puerto Rican diabetes patients facilitate patient buy-in and participation in the intervention, and (2) providing access to a single private space for intervention implementation. Clinic staff members of Puerto Rican ethnicity generated a list of eligible patients, contacted each patient by phone, and scheduled interested patients for an initial visit. At this visit, the clinic staff member introduced each patient to a research assistant, also of Puerto Rican ethnicity, who took the patient into a private unused conference room to complete informed consent and baseline measures. Once completed, the research assistant, who was blinded to the allocation sequence in our trial, directed each patient to the CMA who was located in an unused office a few doors down from the conference room. There, the CMA thanked the patient for attending the initial visit, answered any questions, and scheduled intervention patients to return within 5 days to participate in the intervention session. The CMA delivered the intervention session in this same office, which had been previously used for diabetes education and nutrition counseling (i.e., the office layout, furniture, and patient education posters were on par with the intervention foci).

Acceptability

Clinic demands and handover procedures did not interrupt clinic flow, resulting in strong buy-in from administrators, providers, and other staff members who were often seen directing patients to the intervention room, and would frequently report back patients’ positive comments about the intervention experience. Anecdotally, physicians felt the intervention was an ideal resource for their Puerto Rican patients with diabetes who, more often than not, wanted in-depth, one-on-one education about diabetes that could not be achieved during a traditional primary care visit.

Based on the CMA’s intervention session notes, patients conveyed a strong interest in the Puerto Rican, culturally-specific aspects of the intervention, and were receptive to interactive activities embedded throughout the session, particularly meal planning using the Puerto Rican-specific meal plan booklet. Many patients provided positive feedback about the experience, and wanted to return for additional sessions. Some patients did in fact return, all unannounced, in an attempt to reconnect with the CMA and/or drop off candy and other foods they no longer wanted to eat.

Anecdotally, patients responded well to the CMA’s patient-centered approach, and were open and honest in sharing their difficulties with managing diabetes. Study authors (CYO and NC) remotely observed approximately 50% of the intervention sessions, and overheard patients vocalizing appreciation for the CMA’s ability to identify with Puerto Rican-specific barriers to healthy eating and physical activity, and communicate effectively. Thus, a combination of CMA notes and session observations suggest patients had a positive response to the intervention.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations

Our intervention materials went above and beyond translating content into Spanish, and presenting images of Hispanic individuals with diabetes. All intervention content had to be translated into both the appropriate language and dialect because, at the time this study was conducted, there were no publically available diabetes materials for Puerto Ricans who have a unique Spanish dialect, diet, and cultural beliefs, norms and values relative to other Hispanic subgroups (e.g., Mexican Americans) for which these materials have been made. Thus, we encourage diabetes interventions for Hispanics to account for subgroup-specific dialects, food practices, traditional dishes, and cultural norms in their content, materials, and images.

We identified significant improvements with a single contact intervention. However, as systematic reviews have shown (e.g. see Norris et al, 2001), interventions with regular reinforcements are often more effective than single session interventions or those with limited follow-up sessions. Given that diabetes is a chronic condition, ongoing support is important and the beauty of using the primary care setting is having regular contacts with patients across time (J. D. Fisher et al., 2011; J. D. Fisher et al., 2006). Participants seemed to be asking for this. Future research should explore ways to extend our IMB model-based intervention to support patients over time.

While Puerto Rican males have the highest rate of diabetes compared to both Puerto Rican females, and Mexican American and Cuban males and females (CDC, 2011), we were unable to recruit a substantial number of Puerto Rican males in the pilot randomized controlled trial. Recent evidence suggests Puerto Ricans are as willing or are more willing than non-Hispanic Whites to participate in research studies (Katz et al., 2008; Katz et al., 2007). However, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that Puerto Rican males are less willing than Puerto Rican females to participate in research studies. Additional research is needed to: (1) test whether Puerto Rican males and females differ in their willingness to participate in research studies, (2) identify what factors might explain an observed gender difference, and (3) identify efficacious strategies for increasing male participation.

We used a “carve-out” and “carve-in” approach to implement the intervention, respectively, hiring two research assistants and a CMA to deliver the intervention, and collaborating with a clinic administrator and physician scientist, six dietician interns, an RD/CDE, and another CMA. Due to the HIPPA regulations ("Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Public Law 104–191," 1996), all hired research personnel were required to become clinic employees. We did not anticipate this ahead of time, which delayed the baseline assessment and intervention implementation phases in our trial. For non-medical investigators incorporating a “carve-out” approach to test intervention effectiveness in clinic settings, we encourage planning ahead to ensure all study personnel and procedures adhere to both the healthcare organization’s institutional policies and HIPPA.

We hired a certified medical assistant from the community to become an employee of the clinic for the sole purpose of serving as the interventionist in this study (Otero-Sabogal et al., 2010). However, we did not make intervention training available to other clinic employees. Future efforts should train permanent clinic staff members to carry on an intervention in the absence of staff members hired for research purposes.

Intervention Sustainability

It is important to mention, for reasons unrelated to the intervention itself, the clinic did not adopt the culturally tailored intervention after the trial. As is often the case, grant funding facilitated the development, implementation and evaluation of this intervention for research purposes, but precluded the financial sustainability of the intervention upon study end. In addition, the mobility of researchers, healthcare providers, and clinic administrators is another common issue impeding intervention adoption (Aspy et al., 2008; Rosenheck, 2001). In our case, the clinic administrator in support of the intervention (author SAW) changed jobs when the trial was getting underway; the RD/CDE of Puerto Rican ethnicity (author NC) who helped train the CMA and worked with CYO throughout the trial moved out of state after the 3-month follow-up period; and while the intervention sparked local media attention, and subsequent interest from the Connecticut Health Department in having CYO train health workers across the state to deliver the intervention to their Hispanic diabetes patients, CYO relocated out-of-state for a post-doctoral fellowship and was unable to train these health workers.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations

Reliance on a research grant to test the effectiveness of this culturally tailored intervention precluded financial resources to test clinic maintenance/sustainability and to cover the cost of implementing the intervention upon study end. Researchers largely propose efficacy and effectiveness trials deemed fundable by funding agencies. However, researchers should propose and funding agencies should support research studies that evaluate the reach, adoption, implementation, maintenance, and sustainability of efficacious interventions (Glasgow, 2003).

Both the primary clinic administrator and the primary clinic provider collaborating on the project relocated during the study, and the principal investigator relocated immediately after the study. The mobility of researchers, healthcare providers, and clinic administrators is a common issue precluding the ability to adopt an intervention into routine clinical care. Making intervention training materials available electronically can (1) overcome logistical barriers to training clinic staff to deliver the intervention in the absence of research-practice team members, and can even (2) provide an opportunity for staff members to periodically review and reinforce their initial training (Korsen & Pietruszewski, 2009).

Conclusions

Here, we described a formative process, including interviews with providers, focus groups with patients and a series of multidisciplinary collaborative workshops to develop and implement a culturally tailored intervention in routine clinical care. Prior to implementation, we had a collaborative team of patients, providers, and behavioral scientists review all intervention materials to avoid presenting unclear medical terms, simplify language as necessary by using words and examples that make the information understandable (Sudore & Schillinger, 2009). We also had a health care paraprofessional from the patients’ country of origin deliver all intervention content, which had been previously recommended by others working with this patient population (Cohen, Tallia, Crabtree, & Young, 2005; Hosler & Melnik, 2005). Educational materials and health messages were available in patients’ native language, and took into consideration cultural norms and values, and each patient’s level of comprehension and economic constraints. In addition, the intervention was collaborative, patient-centered, and interactive, and such interventions tend to produce more favorable results than interventions that are mainly didactic and authoritative (Krichbaum, Aarestad, & Buethe, 2003; Norris, Engelgau, & Narayan, 2001). This might be because interactive, problem-solving approaches that teach practical skills improve patients’ acceptance and retention of desired behaviors. Finally, all content was based on an empirically-validated model of health behavior change and tailored to the needs of each patient, which is more efficient to process (Petty & Cacioppo, 1984), and more apt to lead to behavior change (J. D. Fisher & Fisher, 2000).

Based on findings from the pilot randomized controlled trial, the intervention yielded positive clinical effects. Intent-to-treat analyses provided additional support for the intervention’s effects on adherence to diet recommendations and food label reading previously reported with a per protocol approach (Osborn, Amico, Cruz, et al., 2010). Also not reported in Osborn et al. (2010) was the finding that intervention impact on glycemic control was strongest for individuals with uncontrolled diabetes at baseline.

In terms of feasibility and acceptability, all patients invited to participate in the intervention did so within one month’s time, resulting in 100% attendance. Associated intervention costs were ~$57 per patient, and the clinic demands included providing access to a single private space for intervention implementation, and having clinic staff members who were already coordinating care for Puerto Rican diabetes patients facilitate patient buy-in and participation in the intervention. Clinic demands and handover procedures did not interrupt clinic flow. Anecdotally, physicians felt the intervention was an ideal resource for their Puerto Rican patients with diabetes, and a combination of CMA notes and session observations suggest patients had a positive response to the intervention.

To advance the development, implementation, and translation of culturally tailored interventions in routine clinical care, investigators should facilitate collaborative, equitable involvement of all partners in all phases of the research process (Glasgow & Emmons, 2007); understand the needs of the target population and the organization in which the intervention will be delivered (Estabrooks & Glasgow, 2006); plan for limited resources upon study end and barriers to translation at the outset (Estabrooks & Glasgow, 2006); and accrue evidence of effectiveness across populations and organizations (Glasgow et al., 2006). If investigators can develop and evaluate interventions with greater attention to context and external validity and in partnership with relevant decision makers and stakeholders, it will be much easier for health care providers and policy makers to find value in an intervention’s utility (Klesges, Dzewaltowski, & Christensen, 2006) regardless of whether investigators and collaborating providers scientifically or physically relocate. Finally, to create a more relevant and useful science of dissemination, there needs to be an accumulation of literature on the lessons learned from other culturally tailored interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Demetria N. Cain, Luis Casillas, Andrew Dudley, Matt Dudley, Jill Irvine, Melissa Johnson, Beth La Pierre, Scott McCarthy, Erin Paice, Jane Quale, and Iliri Ibrahimi for their assistance in preparing intervention materials. Special thanks to Carmen Aponte, Chariunis Perez, and Rosemary Perez for study recruitment, and collecting and managing data; and Charlene Aponte for delivering the intervention. The study was supported by an American Psychological Association dissertation award and a pilot grant award from the Center for Health Intervention and Prevention at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT. Dr. Osborn conducted this research under an NIH/NIDDK National Research Service Award (F31 DK067022). Dr. Pérez-Escamilla’s contribution to this manuscript was partially supported by the Connecticut Center for Eliminating Health Disparities among Latinos with funding from the NIH/NCMHD (P20 MD001765).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aspy CB, Mold JW, Thompson DM, Blondell RD, Landers PS, Reilly KE, et al. Integrating screening and interventions for unhealthy behaviors into primary care practices. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(5 Suppl):S373–S380. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo A, Giachello A, Bates R, Concha J, Ramirez V, Sanchez C, et al. Community-based Diabetes Education for Latinos: The Diabetes Empowerment Education Program. The Diabetes Educator. 2010;36(4):586–594. doi: 10.1177/0145721710371524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Diabetes prevalence among American Indians and Alaska Natives and the overall population--United States, 1994–2002. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52(30):702–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics--selected areas, 1998–2002. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(40):941–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Age-Adjusted Percentage of Civilian, Noninstitutionalized Population with Diagnosed Diabetes, by Hispanic Origin and Sex, United States, 1997–2009. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Christian JG, Bessesen DH, Byers TE, Christian KK, Goldstein MG, Bock BC. Clinic-based support to help overweight patients with type 2 diabetes increase physical activity and lose weight. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(2):141–146. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Tallia AF, Crabtree BF, Young DM. Implementing health behavior change in primary care: lessons from prescription for health. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(Suppl 2):S12–S19. doi: 10.1370/afm.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Diabetes Fact Sheet. Connecticut Department of Public Health, Health Information Systems and Reporting Division. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Eamranond PP, Legedza AT, Diez-Roux AV, Kandula NR, Palmas W, Siscovick DS, et al. Association between language and risk factor levels among Hispanic adults with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes. American Heart Journal. 2009;157(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE, Mueller M, Echols CL, Gebregziabher M. Longitudinal differences in glycemic control by race/ethnicity among veterans with type 2 diabetes. Medical Care. 2010;48(6):527–533. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d558dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(4 Suppl):S45–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan T, Koro CE, Fedder DO, Bowlin SJ. Ethnic disparities and trends in glycemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes in the U.S. from 1988 to 2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1924–1925. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Amico KR, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Shuper PA, Trayling C, et al. Computer-based intervention in HIV clinical care setting improves antiretroviral adherence: The LifeWindows Project. AIDS and Behavior. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9926-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente RJ, editors. Handbook of HIV prevention. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; 2000. pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Amico RK, Bryan A, Friedland GH. Clinician-delivered intervention during routine clinical care reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000192000.15777.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Misovich SJ. Revised teacher's manual for an Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills model-based intervention. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Harman J. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model: A general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In: Suls J, Wallston KA, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 82–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald N, Damio G, Segura-Perez S, Perez-Escamilla R. Nutrition knowledge, food label use, and food intake patterns among Latinas with and without type 2 diabetes. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108(6):960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine De Gruyther; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE. Translating research to practice: lessons learned, areas for improvement, and future directions. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2451–2456. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, King DK, Toobert DJ, Rahm AK, Jex M, et al. Robustness of a computer-assisted diabetes self-management intervention across patient characteristics, healthcare settings, and intervention staff. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(3):137–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz JP, LeCompte MD. Ethnographic research and the problem of data reduction. Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 1981;12(1):51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AG. Culturally appropriate health education for type 2 diabetes mellitus in ethnic minority groups. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2008;(3):CD006424. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006424.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AG. Culturally appropriate health education for Type 2 diabetes in ethnic minority groups: a systematic and narrative review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetic Medicine. 2010;27(6):613–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Public Law 104–191. US Statut Large. 1996;110:1936–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the health and retirement study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(17):1853–1860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosler AS, Melnik TA. Population-based assessment of diabetes care and self-management among Puerto Rican adults in New York City. The Diabetes Educator. 2005;31(3):418–426. doi: 10.1177/0145721705276580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cain D, Weinhardt L, Benotsch E, Presser K, Zweben A, et al. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based HIV/AIDS risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health Psychology. 2005;24(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandula NR, Diez-Roux AV, Chan C, Daviglus ML, Jackson SA, Ni H, et al. Association of acculturation levels and prevalence of diabetes in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1621–1628. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz RV, Claudio C, Kressin NR, Green BL, Wang MQ, Russell SL. Willingness to participate in cancer screenings: blacks vs whites vs Puerto Rican Hispanics. Cancer Control. 2008;15(4):334–343. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz RV, Green BL, Kressin NR, Claudio C, Wang MQ, Russell SL. Willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical studies: confirmatory findings from a follow-up study using the Tuskegee Legacy Project Questionnaire. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1052–1060. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Christensen AJ. Are we creating relevant behavioral medicine research? Show me the evidence! Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(1):3–4. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsen N, Pietruszewski P. Translating evidence to practice: two stories from the field. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2009;16(1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichbaum K, Aarestad V, Buethe M. Exploring the connection between self-efficacy and effective diabetes self-management. The Diabetes Educator. 2003;29(4):653–662. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine DA, Allison JJ, Cherrington A, Richman J, Scarinci IC, Houston TK. Disparities in self-monitoring of blood glucose among low-income ethnic minority populations with diabetes, United States. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19(2):97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Berry EM, Neumark Y. Limited English proficiency is a barrier to receipt of advice about physical activity and diet among Hispanics with chronic diseases in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109(10):1769–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainous AG, 3rd, Diaz VA, Geesey ME. Acculturation and healthy lifestyle among Latinos with diabetes. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(2):131–137. doi: 10.1370/afm.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainous AG, 3rd, Majeed A, Koopman RJ, Baker R, Everett CJ, Tilley BC, et al. Acculturation and diabetes among Hispanics: evidence from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Reports. 2006;121(1):60–66. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin TL, Maljanian R, McCormack K. Hartford health survey 2003. Hartford, CT: Hartford's Community Health Partnership; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change . 2nd ed. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):561–587. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwasuruba C, Osuagwu C, Bae S, Singh KP, Egede LE. Racial differences in diabetes self-management and quality of care in Texas. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 2009;23(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Amico KR, Cruz N, O'Connell AA, Perez-Escamilla R, Kalichman SC, et al. A brief culturally tailored intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes. Health Education and Behavior. 2010;37(6):849–862. doi: 10.1177/1090198110366004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Amico KR, Fisher WA, Egede LE, Fisher JD. An information-motivation-behavioral skills analysis of diet and exercise behavior in Puerto Ricans with diabetes. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15(8):1201–1213. doi: 10.1177/1359105310364173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Kripalani S. Strategies to address low health literacy and numeracy in diabetes. Clinical Diabetes. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Egede LE. Validation of an Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model of diabetes self-care (IMB-DSC) Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Fisher JD. Diabetes education: Integrating theory, cultural considerations, and individually-tailored content. Clinical Diabetes. 2008;6(4):148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Sabogal R, Arretz D, Siebold S, Hallen E, Lee R, Ketchel A, et al. Physician-community health worker partnering to support diabetes self-management in primary care. Quality in Primary Care. 2010;18(6):363–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The effects of involvement on responses to argument quantity and quality: Central and peripheral routes to persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46(1):69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck RA. Organizational process: A missing link between research and practice. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1607–1612. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Brown AF, Norris KC, Wintz RL, Mangione CM. A systematic review of diabetes self-care interventions for older, African American, or Latino adults. The Diabetes Educator. 2003;29(3):467–479. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, Wang F, Wilson C, Daher C, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(1):83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sixta CS, Ostwald S. Texas-Mexico border intervention by promotores for patients with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2008;34(2):299–309. doi: 10.1177/0145721708314490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Schillinger D. Interventions to improve care for patients with limited health literacy. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 2009;16(1):20–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau: Hartford City, Connecticut Statistics and Demographics. [Retrieved January 13, 2007];2000 from http://hartford.areaconnect.com/statistics.htm.

- Whittemore R. Culturally competent interventions for Hispanic adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(2):157–166. doi: 10.1177/1043659606298615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.