Abstract

Hypocretin/orexin (Hcrt) neurons in the lateral hypothalamus project throughout the brain, including to the hippocampus, where Hcrt receptors are widely expressed. Hcrt neurons activate these targets to orchestrate global arousal state, wake-sleep architecture, energy homeostasis, stress adaptation, and reward behaviors. Hcrt has recently been implicated in cognitive functions and social interaction. Here, we tested the hypothesis that Hcrt neurons are critical to social interaction, particularly social memory, using neurobehavioral assessment and electrophysiological approaches. The validated “two-enclosure homecage test” devices and procedure were used to test sociability, preference for social novelty (social novelty), and recognition memory. A conventional direct contact social test was conducted to corroborate the findings. We found that adult orexin/ataxin-3 transgenic mice (AT, in which Hcrt neurons degenerate by 3 months of age) displayed normal sociability and social novelty with respect to wildtype (WT) littermates. However, AT mice displayed deficits in long-term social memory. Nasal administration of exogenous Hcrt-1 restored social memory to an extent in AT mice.

Hippocampal slices taken from AT mice exhibited decreases in degree of paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) and magnitude of long-term potentiation (LTP), despite displaying normal basal synaptic neurotransmission in the CA1 area compared to WT hippocampal slices. AT hippocampi had lower levels of phosphorylated cyclic AMP-response element binding protein (pCREB), an activity-dependent transcription factor important for synaptic plasticity and long-term memory storage. Our studies demonstrate that Hcrt neurons play an important role in the consolidation of social recognition memory, at least in part through enhancements of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and CREB phosphorylation.

Keywords: Hypocretins/orexins, Learning, Memory, Neuropeptides, Neuromodulation, Social interaction, Social recognition

Introduction

Hypocretins/orexins (Hcrt)–producing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus project broadly to the entire central nervous system including the hippocampus (de Lecea et al., 1998; Peyron et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998). Hcrt peptides (Hcrt-1/orexin A and Hcr-2/orexin B) participate in neuronal regulation via activating their receptors (Hcrt-1R/OX1R and Hcrt-2R/OX2R), contributing to arousal, alertness, sleep, appetite and feeding, and balance between metabolism and energy expenditure (Kilduff, 2005; Carter et al., 2009; de Lecea, 2010; Sakurai and Mieda, 2011). Furthermore, Hcrt neuronal activity has been implicated in the modulation of stress adaptive responses, including stress-induced analgesia (Xie et al., 2008), and anxiogenesis (Winsky-Sommerer et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2010), neuroprotection against focal cerebral ischemia via attenuation of inflammatory responses (Xiong et al., 2013), reward behavior (Harris et al., 2005; Perello et al., 2010; Sharf et al., 2010; McGregor et al., 2011), and learning and memory (Jaeger et al., 2002; Fadel and Burk, 2010; Selbach et al., 2010). Nasal administration of Hcrt-1 improved cognitive performance in sleep-deprived nonhuman primates (Deadwyler et al., 2007). Alterations in Hcrt regulation of septohippocampal cholinergic activity has been link to age-related dysfunctions in arousal, learning, and memory (Stanley and Fadel, 2012).

A clinical study using microdialysis to measure Hcrt-1 in the temporal and frontal lobe brain areas of refractory epileptic patients found a substantial increase in the extracellular Hcrt level when the patients interacted with people (Blouin et al., 2013). Social interaction requires social memory including encoding, storing, and retrieving for processing and retaining information about conspecifics. The hippocampus has an important role in social recognition memory in humans (O’Kane et al., 2004) and rodents (Kogan et al., 2000; Nomoto et al., 2012). The formation of long-term memory in several hippocampus-dependent cognitive tasks including social recognition requires cyclic AMP-response element binding protein (CREB), an activity-dependent gene transcription. Neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine, which enhance memory, induce CREB phosphorylation (Bourtchuladze et al., 1994; Silva et al., 1998; Kogan et al., 2000; Shirayama and Chaki, 2006). However, little is known about the function of Hcrt neurons in social interaction and memory, and physiological roles in modulation of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and CREB activity.

In the present study, we studied the role of Hcrt in social interaction, especially social memory using orexin/ataxin-3 (AT) transgenic mice, which undergo degeneration of Hcrt neurons postnatally (Hara et al., 2001). We investigated three components of social interaction (Crawley, 2004; Riedel et al., 2009): 1) Sociability, i.e. social approach behavior toward unfamiliar conspecifics; 2) Social novelty, i.e. the preference to interact with a novel conspecific compared to a familiarized one; and 3) Social memory, i.e. the retention of social recognition over a period of time between sociability and social novelty tests. We found that compared to WT littermates, AT mice exhibited normal sociability and social novelty, but had shorter social recognition memory. Attenuated PPF and LTP, and decreased phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) levels in the AT hippocampus compared to the WT hippocampus may underlie mechanisms of long-term social memory deficit in AT mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male and female mice (AT and WT C57BL/6 littermates, 3-6 months old) were used. Animals were group-housed under standard laboratory conditions and kept on a normal light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM, and off at 7:00 PM). All studies were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at AfaSci, Inc. and SRI International, and the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Production of transgenic mice followed the procedure described previously (Hara et al., 2001). Presence and copy numbers of the transgene in the offspring were identified by polymerase chain reaction analysis of tail DNA.

Immunohistochemistry and homecage activity monitoring

The Hcrt-positive neurons were detected with goat anti-orexin-B antibody (diluted 1:100, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and using the optical fractionator method on epifluorescence photomicrographs (Zeiss axiovert inverted fluorescent microscope, Zeiss, Germany). The SmartCage™ system (AfaSci, Inc., Redwood City, CA) was used for automated analysis of spontaneous activity in their homecages as described previously (Khroyan et al., 2012). The homecage activity variables (locomotion, travel distance, velocity, and rear-ups) were determined by photo-beam breaks and automatically analyzed using CageScore™ software (AfaSci, Inc.). Both AT and WT mice were simultaneously assessed for 48 h during the light/dark cycle and the second 24-h record was plotted in hourly blocks.

Automated ‘two-enclosure homecage’ social test

The “two enclosure-homecage” tests (Khroyan et al., 2012) were mostly conducted during the light phase, and several experiments were conducted during the first 3 hours of the dark phase as specified in the figure legends. Two transparent Plexiglass enclosures (W 8 x D 6 x H 12 cm) with a metal mesh floor were attached at both end walls of a fresh homecage. The social interaction test consisted of three 10-min sessions based on published procedures (Crawley, 2004; Nadler et al., 2004): 1) habituation - the test subject freely explored a homecage with two empty enclosures (nonsocial cues). 2) Sociability test - the test subject investigated a stimulus mouse designated “Stranger 1”, which was pseudo-randomly placed in one of the enclosures, and 3) Social novelty test - the test subject had the choice to investigate Stranger 1 or a novel mouse designated “Stranger 2”, which was placed into the remaining empty enclosure. To measure social memory, a delay of 1, 10 min, 1, 2, or 24 h between the end of sociability and beginning of social novelty sessions was imposed. During the delay period, the test subject and Stranger 1 were separated and returned to their own homecages (Nadler et al., 2004; Riedel et al., 2009).

The measures of total occupancy time, active time, and traveling distance in each virtual zone were automatically quantified by the SmartCage™ (Khroyan et al., 2012). The enclosures occupied areas of the homecage that were designated as zones 1 and 3 (Zones 1 and 3 are of equal size while the middle zone 2 is twice the size, representing the neutral open area between two enclosures). All three parameters reflect the same social interaction patterns, but occupancy time is the most sensitive and robust quantification, consistent with the conventional “three-chamber” apparatus test (Crawley, 2004; Nadler et al., 2004).

Nasal Administration of Hcrt-1 (Orexin-A) to mice

The AT and WT mice were nasally dosed with Hcrt-1 following the Frey method of nasal administration in rodents (Hanson and Frey, 2008). The AT and WT mice were individually placed in a supine position while under isoflurane anesthesia within a nose cone. A roll of gauze pad was inserted under the dorsal neck to extend the head back toward the supporting surface. The upper surface of the neck was kept horizontal throughout the dosing procedure to maintain the drug solution in the nasal cavity and minimize dripping down the nasopharynx. A 2-μl drop of either Hcrt-1 or deionized water was delivered off the tip of a small pipette and presented to one side of the nares while occluding the opposite naris. One drop of solution was administered every 2 minutes, alternating between each naris. After each nasal application, the mouse was returned to the nose cone to ensure maintenance of anesthesia. Each naris received 2 drops of solution, totaling a combined volume of 8 μl Hcrt-1 (0.8 nmol/mouse, n = 14 AT and n = 14 WT) or deionized water (n = 13 AT, n = 14 WT). Following completion of the administration, the mice were removed from anesthesia and allowed to regain full consciousness in a fresh homecage. Thirty minutes post-nasal application, each mouse was subjected to the social memory test with a 10 min delay between sociability and social novelty testing sessions as described above.

Direct contact social behavioral test

Published procedures (Thor and Holloway, 1986; Kogan et al., 2000) were adapted for this study. Individual test subjects were placed into fresh mouse homecages (Allentown, L 29.8 cm x W 18.0 cm x H 12.8 cm) in an observation room under dim light and allowed to habituate to the new environment for 15 min. A stimulus mouse (same sex and similar age as the test subject) taken from a different homecage was introduced into the cage with the test subject as a social cue for an initial interaction trial of 5 min. The intervals between the initial trial and social memory test were 30 min, 3 h or 24 h as specified in the figure legends. After the selected separation period, the test subject was returned to the test cage with either the familiar or a novel stimulus mouse for the 5 min recognition test. The experimenter manually scored the time that the test subject spent investigating the social cue. Investigation behaviors include contact with any part of the stimulus mouse’s body surface by sniffing, grooming, licking, and pawing, and close following (within 1 cm) according to published procedures (Thor and Holloway, 1986; Kogan et al., 2000).

Olfactory Habituation/Dishabituation Test

Ability to detect odors and discriminate between odors was assessed based on a published protocol (Yang and Crawley, 2009). The test mouse was placed into a fresh homecage with a clean metal rack. A clean, dry cotton-tipped wooden applicator (Medline, Mundelein, IL, USA) was inserted through the water bottle hole of the metal rack and fixed in place. Olfactory testing followed this sequence: nonsocial odors: (1) distil water, (2) almond extract fresh solution (Vanns Spices, Baltimore, MD, USA; 1:100 dilution), (3) banana extract fresh solution (Vanns Spices, 1:100 dilution), and social odors obtained by swiping the applicator in a mouse cage unfamiliar to the test mouse. Each odor was exposed three times consecutively. The experimenter manually scored the cumulative time spent sniffing the tip during the 2 min trial.

Acoustic startle and prepulse inhibition experiments

Acoustic startle and prepulse inhibition were conducted using the SR-Lab startle response system (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) following the procedure described by (Geyer and Dulawa, 2003). Mice were placed in a Plexiglas cylinder resting on the sensor platform within a sound-attenuated and ventilated chamber. Acoustic startle stimuli, prepulse stimuli and continuous background white noise of 65 decibels (dB) were delivered via a high-frequency speaker. Following an acclimation period of 5 min in the containment cylinder, mice were exposed to startle stimuli at five intensities (80, 90, 100, 110, 120 dB) and each startle reflex amplitude was recorded. Each prepulse inhibition trial consisted of a startle stimulus (120 dB, 40 ms), which was preceded by a prepulse (70 - 90 dB, 20 ms duration) with a fixed interval (100 ms) between onset of the prepulse and startle stimuli. Each trial was conducted once in a pseudo-random sequence with a variable inter-trial interval of 12-30 sec.

Hippocampal slice preparations and extracellular recordings

Hippocampal brain slices (400 μm thick) were prepared using a tissue slicer (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA) as previously described (Xie and Smart, 1994) and incubated in an artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) that was oxygenated with 5% CO2/95% O2. The ACSF contained (in mM): NaCl 124.0, KCl 2.5, KH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 2.4, MgSO4 1.3, NaHCO3 26.0 and glucose 10.0. All electrophysiological recordings were made 1 - 6 hours after dissection.

Extracellular recordings were performed at room temperature using an AxoClamp2B amplifier and pClamp 10.3 software (Molecular Devices, Inc. Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Field excitatory post-synaptic potential (fEPSP) in Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses was recorded using a glass microelectrode filled with the ACSF. Biphasic current pulses (0.2 ms) were delivered through a concentric bipolar stimulating electrode (FHC, Inc. Bowdoin, ME, USA). Both recording and stimulus electrodes were placed in parallel on stratum radiatum separated by approximately 500 μm to record fEPSP evoked by stimulation of the Schaffer collateral and commissural fibers. Data was collected using DigiData 1332 and analyzed with Clampfit (Molecular Devices, Inc.). Input-output (I-O) curves were obtained using stimulus intensity from the threshold to a strength evoking the maximum response. The fEPSP slope was measured from the initial phase of the negative wave. The I-O curve was constructed by plotting the fEPSP slope against the fiber volley amplitude. The fiber volley amplitude was binned at 0.2 mV across slices for clarity of presentation. For the basal synaptic activity, test pulse intensities were adjusted to 30 – 35% of the maximal stimulation intensity and delivered at 10 s intervals. The PPF was induced by a pair of stimulations at intervals of 20, 50, or 100 ms. High frequency stimulation (HFS) consisted of 4 trains of 100 pulses (0.2 ms pulse duration, 100 Hz) with an inter-train interval of 20 seconds. LTP was plotted as percentage changes in the fEPSP slope following HFS relative to the basal slope of 5 averaged consecutive fEPSP (mean ± SEM) just before HFS.

Measurement of CREB and phosphorylated CREB

Proteins were extracted from fresh hippocampi taken from the AT and WT littermates after the social interaction tests. Total CREB and pCREB were detected using antibodies #9197S and #9198S, respectively (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Danvers, MA, USA) based on published methods (Tardito et al., 2009). β-actin was obtained from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich Co. St. Louis, MO, USA). In each lane, 30 μg proteins were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate– polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 4–15% Ready Gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) for 1.5 h. Protein bands were transferred from the gel to polyvinylidinene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) for 1 h. After the membrane being blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in PBS/0.05% Tween-20, primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C followed by reaction to horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000, Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h. The membrane was then incubated with anti-β-actin antibodies (1:10000; Sigma) as an even-loading control of total protein. Membranes were scanned using Typhoon trio (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). Both optical densities of CREB and pCREB were analyzed from western blots with normalization to β-actin.

Data analysis

The experiments were carried out with genotypes and treatments blinded to the experimenters. All data are presented as mean ± SEM and subjected to statistical tests with two tails. For two groups, paired or unpaired student’s t tests were used, as appropriate. Multiple-group comparisons were analyzed using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with drug or genotype as the between genotype variable and time interval as the repeated measure. If the ANOVA was statistically significant, Fisher’s PLSD was used to determine group differences. Data from the two components of the social behavior test (sociability and social novelty) were analyzed using within-genotype repeated measure ANOVA, with the factor of cage side (e.g., zone 1 vs. 3). The difference was considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Orexin/ataxin-3 mice display normal sociability in two-enclosure homecage test

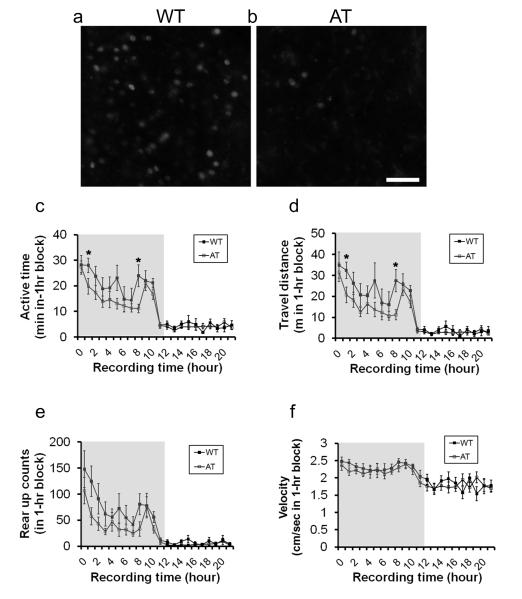

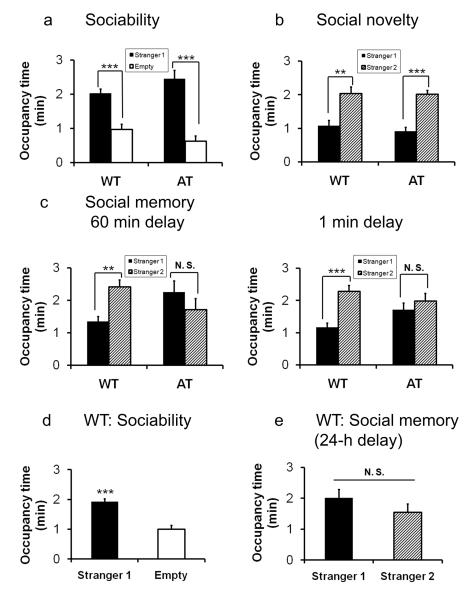

Compared to WT littermates, AT transgenic mice had substantial Hcrt-positive cell loss (Figure 1a and b) and exhibited significantly lower spontaneous activity as indicated by active time (Figure 1c, ANOVA, F(1,14) p = 0.040, Fisher’s PLSD at recording hour 1 p = 0.048 and hour 8 p = 0.015), distance traveled (Figure 1d, hour 1 p = 0.025, and hour 8 p = 0.014). However, AT mice did not show significant differences in rearing (Figure 1e) and traveling speed (Figure 1f) in the dark phase measured using the SmartCage™ (Figure 1 c-f), consistent with the previously reported phenotype (Hara et al., 2001). We used the validated ‘two-enclosure homecage’ testing procedure and quantified mouse behavior using the automated SmartCage™ system (Khroyan et al., 2012). Under these conditions, the test subject freely explored the fresh homecage with nonsocial cues (identical empty enclosures) or social cues (i.e., stranger mice that were taken from different homecages). We observed that during habituation most test mice (AT and WT) spent an equal amount of time in zones 1 and 3, indicating an equal amount of interest or no bias toward either nonsocial cue. During the sociability session, all test mice spent significantly more time investigating Stranger 1 compared to the nonsocial cue (i.e., empty enclosure, Figure 2a and b; paired student’s t test within genotype, WT: t(7) = 4.47, p = 0.003; AT: t(7) = 5.59, p = 0.001). During the social novelty test without a delay between the completion of sociability and the initiation of the social novelty sessions, all test subjects spent more time investigating Stranger 2 than the familiarized Stranger 1 (Figure 2b, WT: t(7) = 4.3, p = 0.003;; AT: t(7) = 5.217, p = 0.001). Analysis of two other parameters, active time and travel distance in zones 1 and 3 yielded similar social interaction patterns (data not shown). These results indicate that there are no significant differences in sociability and social novelty between the genotypes.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Hcrt-positive neurons and spontaneous homecage activity between orexin/ataxin-3 (AT) and wildtype (WT) littermates. Representative images of immunofluorescent staining of the lateral hypothalamus taken from WT (a) and AT mice (b) at 3 months of age. Scale bar: 100 μm in b applied to a. Comparison of active time (c, Recording h 1* p = 0.048, and h 8 p = 0.015), traveling distance (d, h 1* p = 0.025, and h 8 p = 0.014), rearing activity (e), traveling speed (f) in AT and WT littermates in a 24-h record using the SmartCage™ system. Grey background in figures c - f indicates dark phase during a 12:12 light:dark cycle (7 am on and 7 pm off). Data shown are mean ± SEM for each time point (1-h bin). 5 months old male mice, n = 8/genotype.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of sociability, social novelty and social recognition memory in orexin/ataxin-3 mice (AT) and WT littermates conducted during the light phase. a. The test AT mice displayed normal sociability similar to WT mice. b. AT mice displayed a normal degree of preference to a novel mouse (social novelty) compared WT littermates when there was no delay between the end of the sociability session and the initiation of social novelty test. c. In two separate cohorts of animals, both genotypes exhibited normal sociability with Stranger 1 (data not shown). Stranger 2 was introduced 1 min or 60 min after the sociability session. AT mice displayed deficits in social memory after a delay of 60 min (left panel) and 1 min (right panel), while WT mice display social memory in both delay timepoints. d. WT mice exhibited normal sociability towards Stranger 1. e. The same cohort of WT mice lose preference for social novelty in a 24-h delay to re-expose the same Stranger 1 and a novel Stranger 2. Data is shown as mean ± SEM. a, b, and c are the same cohorts of test mice, 3 months-old male, n = 8 per group; d and e are the same cohort of test WT 3-months-old male, n = 8. Paired student’s t-test within genotype * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Orexin/ataxin-3 mice display deficits in long-term social memory

We next tested the hypothesis that Hcrt neurons play a role in social recognition retention or memory. It has been shown that a delay in the social novelty test would reduce the test subject’s preference to social novelty (Nadler et al., 2004; Riedel et al., 2009). We started with a 60-min delay and then reduced to a 10- or 1-min delay. With a delay as short as 1 minute, the test AT subjects did not shift their investigation to Stranger 2 over the familiarized Stranger 1. Rather, they spent an indistinguishable amount of time investigating the familiar and novel social cues (Figure 2c). In contrast, WT subjects shifted their investigation to Stranger 2 following a 10- or 60-min delay (Figure 2c). In a separate experiment using new cohorts of WT mice, while they displayed sociability as usual, with a delay of 24, the test subjects failed to show preference for novel social cues, indicating that normal recognition retention does not extend beyond 24 h in this indirect social test (Figure 2d and e).

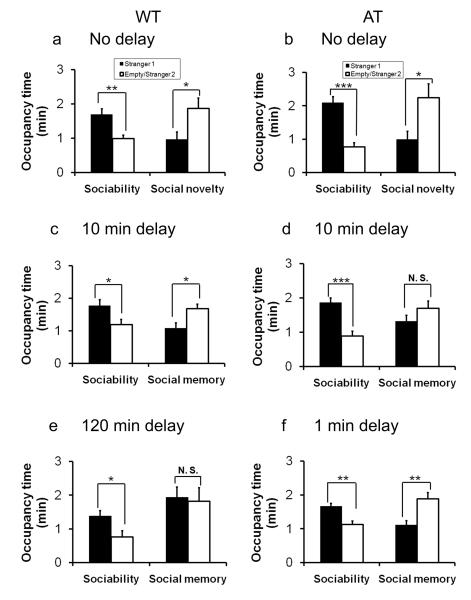

A study reported that Hcrt gene knockout mice were unable to work for food or water reward during the light phase, but performed normally during the dark phase, suggesting a specific role of Hcrt neurons in the diurnal phase (McGregor et al., 2011). We therefore investigated whether the deficit in long-term social memory observed in AT mice could be due to a reduction in arousal or alertness levels during the circadian light phase. Separate cohorts of AT and WT littermates were tested for their social interaction and memory in the first 3 hours of the dark phase using the same two-enclosure homecage test. As in the light phase, AT mice and WT littermates displayed normal sociability and social novelty when there was no delay (Figure 3a and b). However, AT mice retained short-term social memory after a 1-min delay (Figure 3f, paired student’s t test, t(7) = 2.80, p = 0.03), which was not observed when the same experiment was conducted in the light phase, suggesting that social memory formation is influenced by the arousal state (Figure 3f vs. 2c). However, AT mice still exhibited loss of social memory after a 10-min delay, while WT mice preserved their memory with 10-min (Figure 3c - f) and 1-h delay (data not shown) as tested in the light phase. WT mice failed to show preference for novel social cues after a delay of 2 h (Figure 3e), indicating that WT mice did not dramatically improve social memory tested with this delay timepoint during the dark phase.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of social memory between orexin/ataxin-3 mice (AT and WT littermates conducted during the first 3 hours of the dark phase. a. and b. Both WT and AT mice displayed normal sociability and social novelty without a delay between two test sessions. c. WT mice displayed social recognition when the delay between sociability and social novelty tests was 10 min. d. AT mice displayed deficits in social memory with a delay of 10 min. e. WT mice displayed a loss of social memory with a delay of 120 min. f. AT mice displayed short-term social memory with a delay of 1 min. Data are mean ± SEM. All test mice are 3 – 6 months-old male, n = 8 – 12 per group; paired student’s t-test * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

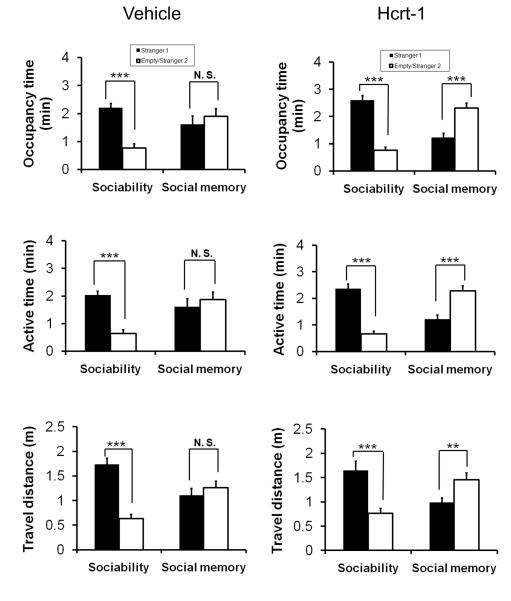

Nasal administration of Hcrt-1 improves social memory in orexin/ataxin-3 mice

To test our hypothesis that a supplement of exogenous Hcrt in the brain of AT mice can lead to an overall improvement in social memory, AT mice were treated with Hcrt-1 via nasal administration, a method that has been shown to effectively deliver a variety of peptides into the brains of rodents (Hanson and Frey, 2008). Thirty minutes after nasal administration of either vehicle (deionized water, n = 13) or Hcrt-1 (0.8 nmol, n = 14), the AT mice were subjected to the sociability test followed by a 10-min delay social memory test. The AT mice that were treated with vehicle spent significantly more time investigating Stranger 1 than the empty enclosure, indicating normal sociability. However, these mice did not shift their investigation to Stranger 2 over the familiarized Stranger 1 in a social memory test with a 10-min delay (Figure 4a, ANOVA, F (3, 52) = 7.247, p < 0.004; Fisher’s PLSD for sociability p<0.001; for social memory p = 0.362). In contrast, the AT subjects that were treated with Hcrt-1 displayed not only normal sociability, but also a distinct shift in their investigation to Stranger 2 from familiarized Stranger 1 (Figure 4b, ANOVA, F (3, 48) = 28.7, p < 0.001; Fisher’s PLSD for sociability p < 0.001; for social memory p<0.001). In addition to occupancy time, two other measureable social interaction parameters, active time (p < 0.001) and travel distance (p = 0.013), also indicated that the Hcrt-treated AT mice showed improvement in social recognition memory (Figure 4c-f). Interestingly, Hcrt-1 treated WT mice did not produce a significant increase in social memory as tested with a 120-min delay compared to nasal vehicle treatment (data not shown) and in respect to non-nasal treatment (Figure 2e).

Figure 4.

Nasal administration of Hcrt-1 improves social memory in Orexin/ataxin-3 mice (AT). The AT subject mice received nasal administration of either vehicle (deionized water, n = 13, a) or Hcrt-1 (0.8 nmol, n = 14, b). The social memory test was with a 10-min delay between the completion of sociability and the beginning of social novelty sessions. The AT mice that were treated with vehicle exhibited normal sociability and reproducible social memory deficits (a, for sociability p < 0.001; for social memory p = 0.362). The AT subjects that were treated with Hcrt-1 displayed normal sociability, but also showed a distinct shift in their investigation to Stranger 2 from familiarized Stranger 1 (b, for sociability p < 0.001; for social memory p < 0.001). Other two measureable social interaction parameters, active time (d, p < 0.001) and travel distance (f, p = 0.013), also indicate that the Hcrt-treated AT mice showed improvement in social recognition memory.

Orexin/ataxin-3 mice display normal social approach behavior but social memory deficit in direct contact social test

To confirm the normal sociability of AT mice, we performed a direct contact social test with manual scoring of the test subject’s interaction with a stimulus mouse taken from a different homecage, acting as a social cue. The onset and duration of social interaction was indistinguishable between AT and WT littermates in the initial trial, confirming both genotypes have normal sociability (61.0 ± 4.5 sec in AT vs. 62.1 ± 6.7 sec in WT, n = 8/group, unpaired student’s t test, t(12) = 14, p > 0.05; Figure 5a and b).

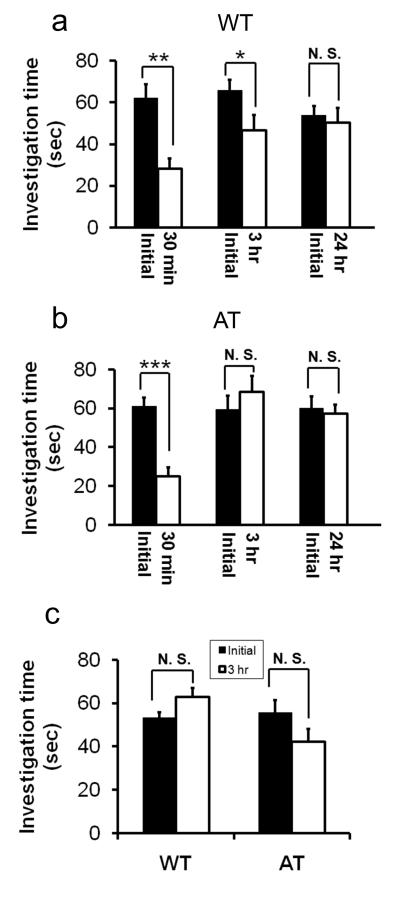

Figure 5.

Orexin/ataxin-3 mice (AT) show normal social interaction but with a social memory deficit compared to WT littermates in a direct contact social test. a. The test WT mice displayed social approach behavior toward the stimulus mouse (sociability) and reduced the approach behavior toward the re-exposed social cue mouse 30 min and 3 h after initial contact as measured by a reduction in investigation time (n = 8 per genotypes, paired student’s t-test * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01). Following a 24 h delay after the initial interaction, the test mouse spent the same amount of time investigating the same social cue mouse as in the initial trial. b. The test AT mice displayed social approach behavior toward the stimulus mouse (sociability) and reduced investigation time toward the same social cue 30 min after the initial interaction (n = 8 per genotypes, paired student’s t test, * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01). Following a delay of 3 or 24 h after the initial interaction, the test mouse spent similar amount of time investigating the re-exposed social cue as in the initial interaction. c. AT and WT mice show similar investigation times toward two different, unfamiliar social cue mice between initial trial and second test following a 3-h delay. In the initial contact, the test subject displayed social approach behavior as indicated by time investigating the stranger mouse. Three hours later, the same test subject was test for its sociability toward a novel mouse (taken from another homecage). All test subjects were 3 month old males (n = 8 per genotype, paired student’s t test, p > 0.05).

To verify deficits in the social memory of AT mice, the test subjects were repeatedly exposed to the same initial social cue with varying separation periods. Previous studies have suggested that the test subject’s investigation time in the initial trial reflects sociability, while a reduction in investigation time during the second exposure to the same social cue is correlated with social recognition retention (Thor and Holloway, 1986; Kogan et al., 2000). In the initial exposure, the test subjects spent approximately 62.1 ± 6.7 sec investigating the social cue as described above (Figure 5a). In the second exposure to the same social cue, following a separation period of 24 h, 3 h or 30 min, the WT test subjects decreased their investigation time toward the same social cue as the separation time reduced. The WT mice could at least recognize and remember the familiarized social cue after separation of up to 3 h (and not beyond 24 h) as indicated by a significant decrease in investigation time compared to the initial trial (Figure 5a, paired student’s t test, at 30 min t(6) = 6.17, p < 0.001, and at 3 h t(9) = 2.98, p < 0.05). In contrast, the AT test subjects displayed decreased investigation time toward the familiarized social cue when the separation period was 30 min (t(6) = 6.16, p < 0.001), but the AT mice did not reduce their investigation time after a 3 h delay (t(7) = −1.25, p > 0.05; Figure 5b), which confirms that they have a shorter recognition retention time compared to WT mice.

To eliminate the possibility that decreased investigation time in repeated trials was due to a decrease in interest/motivation of social interaction or locomotor activity, which could confound social memory readout, we tested social recognition retention with different stimulus mice between the initial trial and the second test. As shown in Figure 5c, both genotypes showed investigation time toward novel mice in a 3-h repeated test comparable to the initial trial, suggesting that social interaction interest/motivation remains the same as in the initial trial.

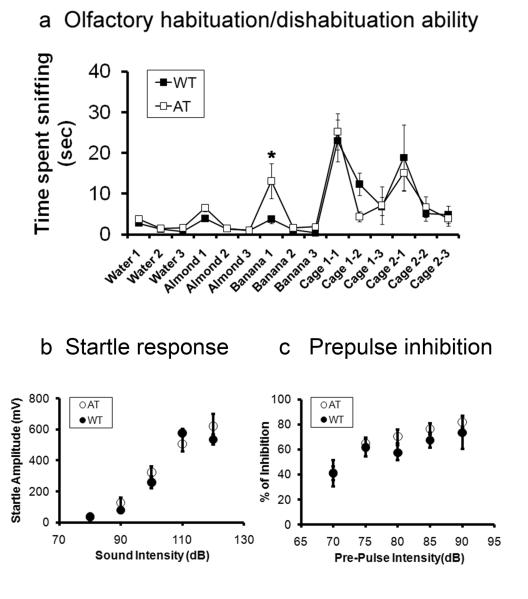

Olfaction plays an important role in social recognition in rodents, since chemically induced anosmia or removal of the vomeronasal organ blocks individual recognition (Ryan et al., 2008). Additionally, soiled bedding samples from an unfamiliar mouse homecage can be used as cues in the recognition process. Therefore, we used the standard protocol for olfactory habituation/dishabituation ability tests (Yang and Crawley, 2009). Time spent sniffing a sequence of novel nonsocial (e.g., water, almond and banana) and social odors (e.g., unfamiliar mouse cage odor) contained in cotton swab tips by the test subjects was scored manually. The result indicates that with the exception of the 1st banana exposure (unpaired student’s t test t(14) = −2.12, p < 0.05), all data points were not significantly different between the genotypes (p>0.05). Furthermore, the olfactory habituation/dishabituation patterns are almost identical to the published data (Yang and Crawley, 2009). Therefore, we concluded that deficits in social memory in AT mice were not caused by differences in olfactory discrimination ability (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Comparison of olfactory and auditory reflex functions in orexin/ataxin-3 (AT) and WT littermates. a. Olfactory habituation/dishabituation ability was measured as time spent sniffing a sequence of novel nonsocial (e.g., water, almond and banana) and social odors (e.g., unfamiliar mouse cage odor) contained in cotton swab tips. Except for banana 1 (unpaired student’s t test * p < 0.05), all data points were not significantly different between genotypes. b. Startle responses evoked by different sound intensities (80 – 120 dB). There were no significant differences between the genotypes (n = 8 per group). c. Prepulse inhibition induced by a constant startle stimulus (120 dB, 40 ms), which was preceded by a prepulse (70 - 90 dB 20 ms) with an interval (100 ms) between the prepulse and startle stimuli. There were no significant differences between the genotypes (n = 8 per group). All test subjects were 3 -4 month old males.

Alternatively, auditory ability differences between AT and WT mice could also influence social interaction. To eliminate this possibility, we assessed acoustic startle responses evoked by a series of sound intensities (80 – 120 dB with an increment of 10 dB). There were no significant differences in startle responses (Figure 6b), and in prepulse inhibition between the two genotypes under our experimental conditions (Figure 6c).

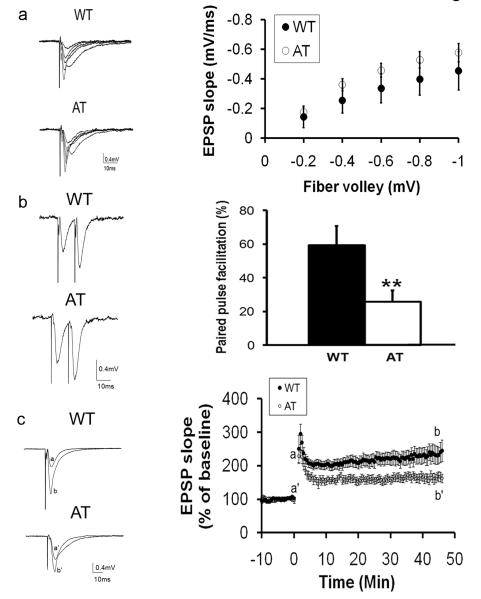

Orexin/ataxin-3 mice display deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity

Since social recognition memory is dependent on hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity (Kogan et al., 2000), we studied hippocampal synaptic basal activity and plasticity in the CA1 area using extracellular recording techniques (Xie and Smart, 1994). We first investigated basal synaptic transmission by analyzing the I-O relationships of fEPSPs evoked by various stimulus intensities. There were no significant differences in the I-O curves between AT and WT mice, indicating that AT mice have normal basal synaptic transmission and synaptic coupling efficiency in the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Orexin/ataxin-3 (AT) mice exhibited normal basal synaptic neurotransmission but a decreased paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) ratio and attenuated long-term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 area of hippocampal slices compared to WT littermates. a. Upper panels: a family of representative voltage traces of fEPSPs in the CA1 area of WT or AT hippocampal slices evoked by different stimulation intensities on the Schaffer collateral and commissural fibers -. Lower panel: the input-output (I-O) of the fEPSP. The fiber valley was binned with an interval of 0.2 mV. There were no significant differences in the I-O curves between the genotypes (WT: n = 14 slices, 5 mice and AT n = 14 slices, 6 mice). b. Comparison of PPF ratio between AT and WT littermates. Left panels are representative traces of paired pulse stimulation with 20-ms interval from WT (left) and AT (right) littermates, respectively. PPF ratio is significantly higher in WT mice than AT mice (WT: 59.3 ± 11.3%, n = 12 slices, 5 mice vs. AT: 25.7 ± 6.9%, n = 14 slices, 6 mice, unpaired student’s t-test p = 0.02). c. Orexin/ataxin-3 (AT) mice exhibited decreases in amplitude of long-term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 area of hippocampal slices compared to WT littermates. Upper panel: Representative voltage traces of fEPSP are superimposed before (a) and after (b) LTP induction by high frequency stimulation of the Schaffer collateral and commissural fibers (100 Hz, 1s, 4 trails, 20 s interval). Lower panel: Each fEPSP slope was normalized to that just prior to the high frequency stimulation and plotted as a function of recording time. The magnitude of LTP during the maintenance phase in WT slices is significantly larger than that in AT slices (WT: 234.6 ± 23.8%, n = 14 slices from 5 mice; AT: 164.3 ± 12.7%, n = 14 slices from 6 mice, two tail unpaired student’s t-test p = 0.02,).

We next analyzed paired pulse facilitation (PPF), a presynaptic form of short-term synaptic plasticity, using intervals of 20, 50 and 100 ms between a pair of stimulation pulses. All three paired pulses of different intervals induced facilitation of fEPSP in both WT and AT mice. The degree of all PPFs was reduced in AT mice, but reached a significant level only with the shortest interval (20 ms). Figure 7b shows that with a 20-ms stimulus interval, the slope of the second fEPSP in WT mice was 59.3 ± 11.3% higher than that of the first fEPSP (n = 12 slices from 5 mice); whereas the slope of the second fEPSP in AT mice was 25.7 ± 6.9% higher than that of the first fEPSP in AT mice (n = 14 slices from 6 mice). The 20-ms interval–induced PPF in WT brain slices was significantly higher than in AT slices (unpaired student’s t test t(24) = −2.63, p = 0.02). The slope of the first fEPSP in WT and AT mice was 0.15 ± 0.02 mV/ms and 0.19 ± 0.02 mV/ms, respectively. These results again indicate that both genotypes have a similar level of basal synaptic activity level (unpaired student’s t test t(24) = −1.41, p = 0.18). Thus, the smaller PPF in the AT mice was not caused by differences in basal synaptic strength.

To investigate the functional consequences of the loss of Hcrt neuronal input on long-term synaptic plasticity we compared LTP in the CA1 area. The results indicate that the magnitude of the maintenance phase of LTP in WT mice is greater than that in AT mice (Figure 7c). Analysis of the averaged five consecutive slopes of fEPSP in the CA1 in WT mice revealed an increase to 234.6 ± 23.8% of the baseline level at 45 min after HFS (n = 14 slice of 5 mice). In AT mice, the slope of fEPSP in CA1 was 164.3 ± 12.7% of baseline at the same timepoint (n = 14 slices of 6 mice, unpaired student’s t-test t(24) = −2.71, p = 0.02). These results indicate that synaptic plasticity in AT slices is impaired in comparison with WT mice. Prior to HFS, the basal level of fEPSP slopes for WT and AT mice was −0.14 ± 0.01 mV/ms and −0.19 ± 0.02 mV/ms, respectively (t(26) = −1.87, p = 0.07). Thus, the smaller magnitude of LTP in AT mice is not due to differences in the basal level of fEPSP between genotypes (Figure 7c).

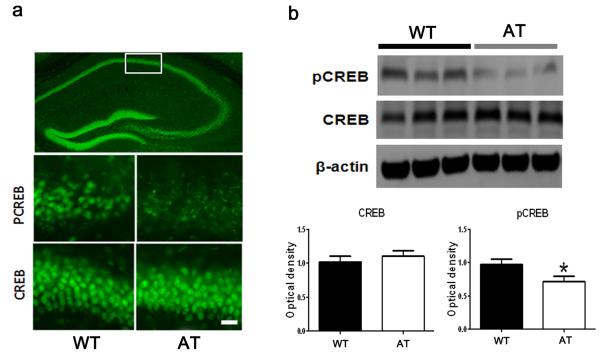

Orexin/ataxin-3 hippocampi have lower levels of phosphorylated CREB

Lastly, we explored possible signaling pathways related to hippocampal CA1 LTP and social memory in behavior. CREB is a nuclear protein that modulates transcription of genes with cAMP-responsive elements in their promoters and acts as a universal modulator of processes required for memory formation, especially hippocampus-dependent social memory. Mice deficient in the alpha and delta isoforms of the CREB transcription factor (CREBaD2 mice) are impaired in long-term, but not short-term social memory (Bourtchuladze et al., 1994; Silva et al., 1998; Kogan et al., 2000). We therefore investigated the level of total CREB and phosphorylated CREB (pCREB), the active form of CREB in hippocampi, taken from mice after social interaction and memory testing (n = 9 mice per genotype). In both genotypes, CREB immunostaining was found heterogeneously distributed in most cell bodies throughout the hippocampus (Figure 8a). Immunostaining indicates that there were no significant differences in total CREB expression between the genotypes. However, the pCREB level was apparently lower in the hippocampus taken from AT compared to that of WT mice, though most neurons express pCREB in both genotypes (Figure 8a). Optical density analysis on the western blot from each genotype hippocampus quantified the CREB and pCREB levels. The quantitative analyses obtained from the western blots confirm that there is no significant differences in total CREB expression between the genotypes, and revealed that pCREB in the AT hippocampus was significantly lower by 25 ± 7.5% compared to the WT hippocampus (Figure 8b, n = 9 western blot bands per genotype, unpaired student’s t test t(16) = 2.29, p <0.05)

Figure 8.

Levels of phosphorylated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (pCREB) in hippocampi of orexin/ataxin-3 (AT) is lower compared to those in WT hippocampi. a. Representative images of immunochemistry staining shows heterogeneous CREB expression in the whole coronal section of the hippocampus taken from a WT mouse (top), differences in expression of pCREB (middle) and CREB (bottom) in the CA1 area (indicated by white line box in the whole hippocampus image shown above) between WT and AT mice. Scale bar: 50 μm in the bottom panel applied to middle panel. b. Representative western blot images of pCREB (top), CREB (middle) and β-actin (bottom) in the hippocampus taken from AT and WT littermates (n = 3 mice per genotype). Optical density of total CREB levels obtained from the western blots are not significantly different between the genotypes (left panel). Optical density of pCREB (right panel) is significantly lower in the hippocampi taken from AT mice than that from WT littermates (n = 9 western blot bands per genotype, unpaired student’s t-test p < 0.05). Both optical densities of CREB and pCREB were normalized to β-actin.

Discussion

Social recognition memory, the ability to distinguish and remember familiar from novel conspecifics, is critical for appropriate social behavior. Rodents can retain recognition of recently encountered conspecifics for a certain period. In the present study, using AT mice in which Hcrt neurons are genetically ablated (Hara et al., 2001), we obtained the novel result that the endogenous Hcrt system is essential for the formation of long-term social memory. The microdialysis study of Hcrt in the human brains revealed a dramatic increase in Hcrt levels associated with social interaction (Blouin et al., 2013). Our study supports this clinical observation and defines the physiological role of the Hcrt system in social memory, but not necessarily in initiation of social approach, since AT mice display normal sociability. Our results suggest that the Hcrt surge upon interaction with conspecifics consolidates storage of information, but may not be critical in the stages of encoding (e.g., processing information), and retrieval (eg., recalling) of stored information, since AT mice can process and recognize the familiarized social cue and display preference to the novel social cue when there is no delay or a short delay (eg., 1 min) in the memory test.

To assess social interaction in humans and animal models, several behavioral tests have been developed (Kaidanovich-Beilin et al., 2011). The three-chamber apparatus and testing procedure have been commonly employed to assess rodents’ sociability, social novelty, and social memory (Crawley, 2004; Moy et al., 2004; Deng et al., 2007). AT mice display decreased active time and locomotion, which could confound social behavior testing, especially when using a large unfamiliar chamber with physical dividers. We therefore developed and validated a two-enclosure test in a mouse homecage (Khroyan et al., 2012), and showed the social interaction pattern comparable to the result obtained using the three-chamber test (Crawley, 2004; Moy et al., 2004; Deng et al., 2007). Using this objective testing method, we found that AT mice displayed normal sociability and social novelty, but exhibited a long-term memory deficit.

The social memory of AT mice was shorter than 1 min when the test was conducted in the light phase, but at least 1 min and shorter than 10 min when the task was performed in the dark phase. The improvement in social recognition task performance during the dark phase not only supports the specific role of Hcrt neurons in reward behavior during the diurnal phase (McGregor et al., 2011), but also suggests that the arousal-promoting role of Hcrt may be crucial in consolidation of memory storage. Interestingly, the WT mice’s social memory was not enhanced at the timepoint tested in the dark phase, suggesting a possible ‘saturated effect’ of Hcrt levels in WT mice. Alternatively, enhancement of social memory could be observed in refined delay timepoints.

Hcrt neurons also produce other neurotransmitters, such as dynorphin, pentraxin and glutamate, which may influence memory (Chou et al., 2001; Reti et al., 2002; Rosin et al., 2003). Therefore, it is important to determine whether a supplement of exogenous Hcrt in the brain can restore long-term social memory in AT mice. Indeed, we found that nasally administered Hcrt-1 extended social memory in AT mice from less than 1 min to at least 10 min tested in the light phase. In contrast, Hcrt-1 did not prolong social recognition retention in WT mice tested with a 120-min delay. These findings are compatible with reported results that nasal administration of Hcrt-1 selectively improves sleep deprivation-caused memory deficits without enhancing memory in normal nonhuman primates (Deadwyler et al., 2007). However, these treatment regimens were acute and whether chronic treatment with Hcrt can enhance memory is worthy of further investigation.

The deficit in long-term social memory in AT mice was corroborated by a conventional direct contact social test. In this test, social recognition memory was inferred by a decrease in the investigation time toward the re-exposed social cue (Thor and Holloway, 1986; Kogan et al., 2000). The direct contact allows more engagements between the test subject and the social cue, leading to stronger social stimulation, consequently longer recognition retention compared to the two-enclosure test. AT mice exhibited normal sociability toward unfamiliar conspecifics, and their social recognition retention lasted at least 30 min, but less than 3 h. In contrast, the WT mice’s recognition retention lasted for at least 3 hours and disappeared after 24-h separation. The AT mice deficit in long-term memory was not due to any defects in olfactory and auditory ability, since between the AT and WT littermates there were no significant differences in the olfactory habituation/dishabituation patterns, and in acoustic startle responses and prepulse inhibition.

Social recognition, particularly long-term memory in humans and rodents critically rely on intact hippocampal structure and function (Corkin et al., 1984; van Wimersma Greidanus and Maigret, 1996; Kogan et al., 2000). The hippocampus receives direct input from Hcrt neurons and expresses Hcrt receptors. Furthermore, Hcrt-mediated activation of noradrenergic and serotonergic systems might also play a role in consolidating memory, because these monoaminergic neurons abundantly project to the hippocampus (Peyron et al., 1998; Kilduff, 2005; Carter et al., 2009; de Lecea, 2010; Eriksson et al., 2010; Sakurai and Mieda, 2011). We therefore focused on the investigation of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and signaling pathway to explore mechanisms underlying the effects of Hcrt in storage of social memory.

While the AT mouse CA1 has normal basal neurotransmission as WT littermates, both PPF and LTP were significantly attenuated in the AT hippocampus. These results suggest that short- and long-term synaptic plasticity in the AT hippocampus may be impaired in the absence of Hcrt neuronal input. Conversely, an LTP-like phenomenon in the CA1 area could be induced by the application of exogenous Hcrt-1 in hippocampal slices via activation of several protein kinases, including protein kinase A and C (Selbach et al., 2010). Moreover, Hcrt in the ventral tegmental area has been shown to be critical for the induction of synaptic plasticity that was associated with behavioral sensitization to cocaine in rats (Borgland et al., 2006).

The formation of long-term memory in hippocampus-dependent cognitive tasks including social recognition has been found to involve cyclic AMP-response element binding protein (CREB). CREB acts as memory storage and sustains synaptic plasticity in a wide range of synapses, including in the hippocampus. Several neurotransmitters, especially dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline and acetylcholine, which are known to enhance memory, induce CREB phosphorylation (Bourtchuladze et al., 1994; Silva et al., 1998; Kogan et al., 2000; Thonberg et al., 2002). The Hcrt system has been found to directly synapse and activate the amine systems and promote noradrenaline and acetylcholine release (Carter et al., 2009; Eriksson et al., 2010; Stanley and Fadel, 2012). Complementary to this indirect “upstream” modulation of CREB, Hcrt can directly activate CREB by acting on Hcrt receptors that are Gq-protein-coupled receptors. This leads to signaling through phospholipase C and calcium-dependent as well as calcium-independent transduction pathways (Sakurai et al., 1998; Sakurai and Mieda, 2011). Activation of Hcrt receptors also leads to stimulation of PKA and PKC as mentioned above (Selbach et al., 2010), and a recent study showed that exogenous Hcrt prolonged CREB phosphorylation via protein kinase C activation (Guo and Feng, 2012). As shown in this study, the level of pCREB in WT hippocampi is significantly higher than in AT hippocampi; whereas there were no significant differences in total CREB between the genotypes.

Social memory underpins and enables appropriate social interaction, which are critical for the establishment of relationships and stability of the networks. Several neuropsychiatric disorders are characterized by disruptions of social recognition or long-term social memory including schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorders (McClure et al., 2003; Riedel et al., 2009; Brotman et al., 2010; Ibi et al., 2010; Kaidanovich-Beilin et al., 2011). Loss of Hcrt neurons causes narcolepsy in humans (Scammell et al., 2001; Siegel et al., 2001). Narcoleptic patients are often anxious about disease-related deficient memory functions (Aguirre et al., 1985; Rogers and Rosenberg, 1990) and modest memory impairments were reported (Henry et al., 1993; Naumann et al., 2006). While narcoleptic patients display normal sociability, whether they have deficits in long-term social memory is currently unknown, and this can be a potential area for clinical investigation.

The present study has uncovered a physiological role of Hcrt neurons in long-term social memory using a transgenic animal model and pharmacological approach. Hcrt neurons are not essential for sociability, but play a critical role in formation of long-term social memory. This finding is consistent with the notion that the Hcrt system contributes to spatial and nonsocial learning and memory (Jaeger et al., 2002; Akbari et al., 2007; Eriksson et al., 2010; Fadel and Burk, 2010). The mechanisms underlying the effects of Hcrt in formation of social memory, at least in part through enhancing synaptic plasticity and increasing pCREB in the hippocampus. The previously unrecognized role for the Hcrt system in social memory may have clinical implications, and will foster further integrative research using animal disease models and appropriate tests to identify novel neuronal pathways and therapeutics for modulation of social interaction and recognition memory.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01MH078194, R44DA026363, R43NS065555, R43MH076309, R41HL84990, and R43 NS073311. We are grateful to T.S. Chen and Drs. S. Black and T. Kilduff at SRI International for kindly providing the AT and WT mice used in this study. We would like to thank interns Carlos Sanchez, Gregory Frane, Waranga Safi, Sandie Luo and Zhaohui Li at AfaSci Research Laboratories for assistance in animal care and experiments.

Footnotes

Commercial Interest: The SmartCage™ system, developed by AfaSci, Inc., was used to monitor animal behavior, social interaction and social memory at homecage in this study. X. Xie is the founder and owner of AfaSci.

References

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio AR. The human amygdala in social judgment. Nature. 1998;393:470–474. doi: 10.1038/30982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre M, Broughton R, Stuss D. Does memory impairment exist in narcolepsy-cataplexy? J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1985;7:14–24. doi: 10.1080/01688638508401239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari E, Naghdi N, Motamedi F. The selective orexin 1 receptor antagonist SB-334867-A impairs acquisition and consolidation but not retrieval of spatial memory in Morris water maze. Peptides. 2007;28:650–656. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin AM, Fried F, Wilson C, Staba RJ, Behnke EJ, Lam HA, Maidment NT, Karlsson KA, Lapierre JL, Siegel JM. Human hypocretin and melanin concentrating hormone levels are linked to emotion and social interaction. Nature Communications. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2461. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Taha SA, Sarti F, Fields HL, Bonci A. Orexin A in the VTA is critical for the induction of synaptic plasticity and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Neuron. 2006;49:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtchuladze R, Frenguelli B, Blendy J, Cioffi D, Schutz G, Silva AJ. Deficient long-term memory in mice with a targeted mutation of the cAMP-responsive element-binding protein. Cell. 1994;79:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Rich BA, Guyer AE, Lunsford JR, Horsey SE, Reising MM, Thomas LA, Fromm SJ, Towbin K, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Amygdala activation during emotion processing of neutral faces in children with severe mood dysregulation versus ADHD or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:61–69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter ME, Adamantidis A, Ohtsu H, Deisseroth K, de Lecea L. Sleep homeostasis modulates hypocretin-mediated sleep-to-wake transitions. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10939–10949. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1205-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Lee CE, Lu J, Elmquist JK, Hara J, Willie JT, Beuckmann CT, Chemelli RM, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB, Scammell TE. Orexin (hypocretin) neurons contain dynorphin. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC168. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkin S, Sullivan EV, Carr FA. Prognostic factors for life expectancy after penetrating head injury. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:975–977. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050200081022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN. Designing mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autistic-like behaviors. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:248–258. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L. A decade of hypocretins: past, present and future of the neurobiology of arousal. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;198:203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Porrino L, Siegel JM, Hampson RE. Systemic and nasal delivery of orexin-A (Hypocretin-1) reduces the effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance in nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14239–14247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3878-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng BS, Nakamura A, Zhang W, Yanagisawa M, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T. Contribution of orexin in hypercapnic chemoreflex: evidence from genetic and pharmacological disruption and supplementation studies in mice. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1772–1779. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00075.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson KS, Sergeeva OA, Haas HL, Selbach O. Orexins/hypocretins and aminergic systems. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;198:263–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, Burk JA. Orexin/hypocretin modulation of the basal forebrain cholinergic system: Role in attention. Brain Res. 2010;1314:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Insel TR. The neuroendocrine basis of social recognition. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:200–224. doi: 10.1006/frne.2002.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Dulawa SC. Assessment of murine startle reactivity, prepulse inhibition, and habituation. Curr Protoc Neurosci Chapter. 2003;8 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0817s24. Unit 8 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Feng P. OX2R activation induces PKC-mediated ERK and CREB phosphorylation. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:2004–2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LR, Frey WH., 2nd Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood-brain barrier to target therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and treat neurodegenerative disease. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9(Suppl 3):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S3-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron. 2001;30:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry GK, Satz P, Heilbronner RL. Evidence of a perceptual-encoding deficit in narcolepsy? Sleep. 1993;16:123–127. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibi D, Nagai T, Koike H, Kitahara Y, Mizoguchi H, Niwa M, Jaaro-Peled H, Nitta A, Yoneda Y, Nabeshima T, Sawa A, Yamada K. Combined effect of neonatal immune activation and mutant DISC1 on phenotypic changes in adulthood. Behav Brain Res. 2010;206:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger LB, Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of orexin-A on memory processing. Peptides. 2002;23:1683–1688. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PL, Truitt W, Fitz SD, Minick PE, Dietrich A, Sanghani S, Traskman-Bendz L, Goddard AW, Brundin L, Shekhar A. A key role for orexin in panic anxiety. Nat Med. 2010;16:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nm.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Lipina T, Vukobradovic I, Roder J, Woodgett JR. Assessment of social interaction behaviors. J Vis Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M, Groenink L, Kas MJ, Bijlsma EY, Olivier B, Sarnyai Z. Influence of transgenic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) over-expression on social recognition memory in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2011;218:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroyan TV, Zhang J, Yang L, Zou B, Xie J, Pascual C, Malik A, Zaveri NT, Vazquez J, Polgar W, Toll L, Fang J, Xie X. Rodent motor and neuropsychological behaviour measured in home cages using the integrated modular platform SmartCage() Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;39:614–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2012.05719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff TS. Hypocretin/orexin: maintenance of wakefulness and a multiplicity of other roles. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan JH, Frankland PW, Silva AJ. Long-term memory underlying hippocampus-dependent social recognition in mice. Hippocampus. 2000;10:47–56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<47::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Pope K, Hoberman AJ, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Facial expression recognition in adolescents with mood and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1172–1174. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor R, Wu MF, Barber G, Ramanathan L, Siegel JM. Highly specific role of hypocretin (orexin) neurons: differential activation as a function of diurnal phase, operant reinforcement versus operant avoidance and light level. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15455–15467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4017-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A. Impact of prosocial neuropeptides on human brain function. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:463–470. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Perez A, Barbaro RP, Johns JM, Magnuson TR, Piven J, Crawley JN. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:287–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler JJ, Moy SS, Dold G, Trang D, Simmons N, Perez A, Young NB, Barbaro RP, Piven J, Magnuson TR, Crawley JN. Automated apparatus for quantitation of social approach behaviors in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann A, Bellebaum C, Daum I. Cognitive deficits in narcolepsy. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:329–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto M, Takeda Y, Uchida S, Mitsuda K, Enomoto H, Saito K, Choi T, Watabe AM, Kobayashi S, Masushige S, Manabe T, Kida S. Dysfunction of the RAR/RXR signaling pathway in the forebrain impairs hippocampal memory and synaptic plasticity. Mol Brain. 2012;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Kane G, Kensinger EA, Corkin S. Evidence for semantic learning in profound amnesia: an investigation with patient H.M. Hippocampus. 2004;14:417–425. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perello M, Sakata I, Birnbaum S, Chuang JC, Osborne-Lawrence S, Rovinsky SA, Woloszyn J, Yanagisawa M, Lutter M, Zigman JM. Ghrelin increases the rewarding value of high-fat diet in an orexin-dependent manner. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:880–886. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reti IM, Reddy R, Worley PF, Baraban JM. Selective expression of Narp, a secreted neuronal pentraxin, in orexin neurons. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1561–1565. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel G, Kang SH, Choi DY, Platt B. Scopolamine-induced deficits in social memory in mice: reversal by donepezil. Behav Brain Res. 2009;204:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE, Rosenberg RS. Tests of memory in narcoleptics. Sleep. 1990;13:42–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin DL, Weston MC, Sevigny CP, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Hypothalamic orexin (hypocretin) neurons express vesicular glutamate transporters VGLUT1 or VGLUT2. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:593–603. doi: 10.1002/cne.10860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE, Young LJ. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:534–547. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan BC, Young NB, Moy SS, Crawley JN. Olfactory cues are sufficient to elicit social approach behaviors but not social transmission of food preference in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;193:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Mieda M. Connectomics of orexin-producing neurons: interface of systems of emotion, energy homeostasis and arousal. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammell TE, Nishino S, Mignot E, Saper CB. Narcolepsy and low CSF orexin (hypocretin) concentration after a diencephalic stroke. Neurology. 2001;56:1751–1753. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach O, Bohla C, Barbara A, Doreulee N, Eriksson KS, Sergeeva OA, Haas HL. Orexins/hypocretins control bistability of hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity through co-activation of multiple kinases. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;198:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharf R, Guarnieri DJ, Taylor JR, DiLeone RJ. Orexin mediates morphine place preference, but not morphine-induced hyperactivity or sensitization. Brain Res. 2010;1317:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y, Chaki S. Neurochemistry of the nucleus accumbens and its relevance to depression and antidepressant action in rodents. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4:277–291. doi: 10.2174/157015906778520773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM, Moore R, Thannickal T, Nienhuis R. A brief history of hypocretin/orexin and narcolepsy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:S14–20. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00317-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AJ, Kogan JH, Frankland PW, Kida S. CREB and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:127–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EM, Fadel J. Aging-related deficits in orexin/hypocretin modulation of the septohippocampal cholinergic system. Synapse. 2012;66:445–452. doi: 10.1002/syn.21533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thonberg H, Fredriksson JM, Nedergaard J, Cannon B. A novel pathway for adrenergic stimulation of cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation: mediation via alpha1-adrenoceptors and protein kinase C activation. Biochem J. 2002;364:73–79. doi: 10.1042/bj3640073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardito D, Musazzi L, Tiraboschi E, Mallei A, Racagni G, Popoli M. Early induction of CREB activation and CREB-regulating signalling by antidepressants. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:1367–1381. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor DH, Holloway WR., Jr. Caffeine and copulatory experience: interactive effects on social investigatory behavior. Physiol Behav. 1986;36:707–711. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wimersma Greidanus TB, Maigret C. The role of limbic vasopressin and oxytocin in social recognition. Brain Res. 1996;713:153–159. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsky-Sommerer R, Yamanaka A, Diano S, Borok E, Roberts AJ, Sakurai T, Kilduff TS, Horvath TL, de Lecea L. Interaction between the corticotropin-releasing factor system and hypocretins (orexins): a novel circuit mediating stress response. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11439–11448. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3459-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Smart TG. Modulation of long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons by zinc. Pflugers Arch. 1994;427:481–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00374264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Wisor JP, Hara J, Crowder TL, LeWinter R, Khroyan TV, Yamanaka A, Diano S, Horvath TL, Sakurai T, Toll L, Kilduff TS. Hypocretin/orexin and nociceptin/orphanin FQ coordinately regulate analgesia in a mouse model of stress-induced analgesia. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2471–2481. doi: 10.1172/JCI35115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, White RE, Xu L, Yang L, Sun X, Zou B, Pascual C, Sakurai T, Giffard RG, Xie X. Mitigation of Murine Focal Cerebral Ischemia by the Hypocretin/Orexin System Is Associated With Reduced Inflammation. Stroke. 2013 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.681700. (online) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Crawley JN. Simple behavioral assessment of mouse olfaction. Curr Protoc Neurosci Chapter. 2009;8 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0824s48. Unit 8 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]