Abstract

Prion diseases are a group of fatal neurodegenerative disorders that include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and kuru in humans, BSE in cattle, and scrapie in sheep. Such illnesses are caused by the conversion and accumulation of a misfolded pathogenic isoform (termed PrPSc) of a normally benign, host cellular protein, denoted PrPC. We employed high-throughput screening (HTS) ELISAs to evaluate compounds for their ability to reduce the level of PrPSc in Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML) prion-infected mouse neuroblastoma cells (ScN2a-cl3). Arylpiperazines were among the active compounds identified but the initial hits suffered from low potency and poor drug-likeness. The best of those hits, such as 1, 7, 13, and 19, displayed moderate antiprion activity with EC50 values in the micromolar range. Key analogs were designed and synthesized based on the SAR, with analogs 41, 44, 46, and 47 found to have sub-micromolar potency. Analogs 41 and 44 were able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and achieved excellent drug concentrations in the brains of mice after oral dosing. These compounds represent good starting points for further lead optimization in our pursuit of potential drug candidates for the treatment of prion diseases.

Keywords: Neurodegenerative diseases, prion disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, piperazine, arylpiperazine, SAR

Prion diseases are transmissible, rapidly progressive, fatal, and untreatable neurodegenerative disorders that affect both humans and animals.1–3 An early key pathogenic event in diseases caused by the prion protein (PrP) is the conversion of the host cellular PrP, denoted PrPC, into an aberrant disease-causing isoform, PrPSc, which accumulates in the CNS of the infected host.4–6 The exact mechanism for the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc remains unknown.

Currently, no treatments exist for prion diseases. Several classes of antiprion compounds that target levels of PrPSc or PrPC, including approved drugs (for other uses) in humans as well as experimental small molecules, have been reported.7, 8 Some FDA-approved drugs, including quinacrine, phenothiazines, and statins, showed antiprion activity in cell culture but demonstrated no in vivo efficacy when tested in prion-infected mice.9–11

We have sought a strategy to treat prion disease by lowering the levels of PrPSc in prion-infected cell models. Reduced PrPSc levels are correlated with decreased prion infectivity in cultured cells and delayed development of clinical signs. Using HTS, we identified small molecules that lowered the levels of PrPSc in an RML prion-infected murine neuroblastoma cell line (ScN2a-cl3)12, among which were the arylpiperazines (Silber et al., in preparation). Herein, we report SAR analysis and preliminary lead optimization to improve the potency and drug-likeness of the arylpiperazines, and describe the discovery of potent, metabolically stable, BBB-penetrant leads from this series. These compounds are excellent starting points for further lead optimization, with the goal of identifying candidates for further testing in scrapie- and CJD-infected animal models of prion disease.

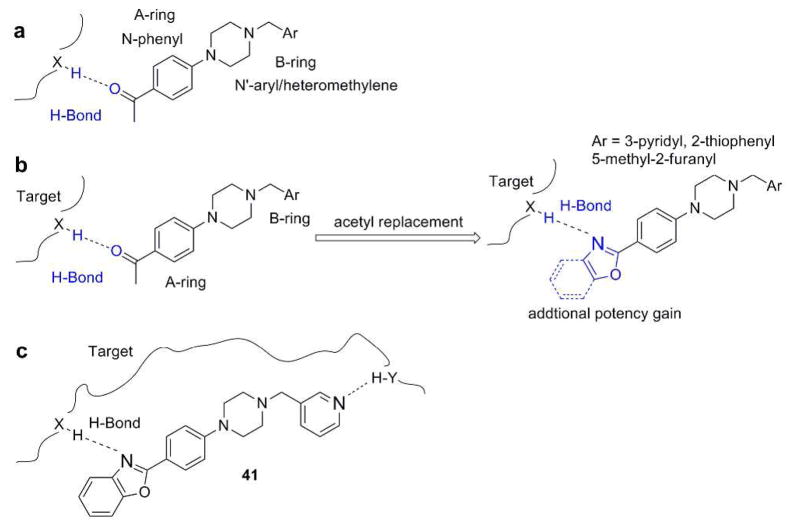

From our HTS screening efforts of 53,000 compounds, we identified 881 arylpiperazine analogs, 108 of which reduced PrPSc levels in ScN2a-cl3 cells by ≥30%. Of these 108 actives, 58 were subjected to a confirmatory assay, and 41 of which were confirmed, i.e., reduced the level of PrPSc by ≥30% without affecting cell viability (≤30% inhibition). A majority (n=29) of these compounds, including the top 22 actives, are derivatives of N-arylpiperazine having a para methylketone or acetyl group on the phenyl ring (1, 7, 13, 14, 18, and 19) (Table 1). Compounds bearing other substituents on the N-phenyl ring, regardless of electronic-rich (6, 12, 17, and 22) or electronic-deficient (5, 11, 16, and 21) or their positions on the N-phenyl ring (compare 3 and 4; 9 and 10; 15 and 16; 20 and 21), were found to be inactive under our assay conditions (Table 1). This finding argues for the importance of the 4-acetyl group of the N-aryl ring in determining the potency of those compounds. We initially postulated that the oxygen of the acetyl group is involved in a HB with the putative target protein (Figure 1a). Conversely, the substitution requirement on the N′-nitrogen of the piperazine is less stringent, and both arylmethylenes and heteroarylmethylenes, including benzyl (1), 3-pyridinylmethylene (7), 2-furanylmethylene (19), and 2-thiophenylmethylene (13 and 14), are well tolerated and show similar antiprion activities (Table 1).

Table 1.

PrPSc reduction for selected arylpiperazine analogs.

| compd | R1 | X | PrPSc reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4-MeCO- | CH | 94 |

| 2 | H | CH | 5 |

| 3 | 3-Cl | CH | 7 |

| 4 | 4-Cl | CH | 6 |

| 5 | 4-F | CH | 7 |

| 6 | 4-MeO | CH | 7 |

| 7 | 4-MeCO- | N | 73 |

| 8 | H | N | 4 |

| 9 | 3-Cl | N | 4 |

| 10 | 4-Cl | N | 0 |

| 11 | 4-F | N | 27 |

| 12 | 4-MeO | N | 10 |

| compd | R2 | Y | R3 | PrPSc reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 4-MeCO- | S | H | 91 |

| 14 | 4-MeCO- | S | 4-Me | 78 |

| 15 | 3-Cl | S | 3-Br | 34 |

| 16 | 4-Cl | S | 2-Br | 12 |

| 17 | 4-MeO | S | H | 16 |

| 18 | 4-MeCO- | O | H | 96 |

| 19 | 4-MeCO- | O | 2-Me | 78 |

| 20 | 3-Cl | O | H | 6 |

| 21 | 4-Cl | O | H | 13 |

| 22 | 4-MeO | O | 2-Br | 6 |

Figure 1.

(a) Arylpiperazine lead, showing HB interaction between its 4-acetyl group and the putative target. (b) Design of piperazine analogs: replacement of acetyl with oxazole or benzoxazole. (c) Compound 41, showing its HB interactions with the putative target.

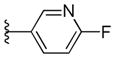

In our A-ring SAR exploration, we initially tested the requirement for the 4-acetyl group. Compounds with various substituents including 4-acetyl, chloro, fluoro and methoxy as well as their regioisomers (11–12, 23–26, Supplementary Table 1) were purchased and tested. All six compounds showed ≤30% PrPSc reduction and EC50 values >32 μM; thus, they were considered inactive in our assays.

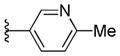

On the B-ring side, several examples of different (hetero) aryls representing phenyl (1), 3-pyridyl (7), thiophenyl (13), and furanyl (19) scaffolds were selected to test the influence of the B-ring on antiprion activity. Compounds 1, 7, 13, and 19 were found to possess only moderate activities, with EC50 values ranging 1.95 μM to 4.62 μM (Table 1). For our lead compounds, we aimed for >10-fold potency compared to those identified in the ScN2a-cl3 cell assay. Thus, we embarked on an SAR effort to improve the antiprion potency of the arylpiperazine series. To ensure the lowering of PrPSc level was not due to cytotoxicity, cell viability in ScN2a-cl3 cells was also carried out to accompany each EC50 ELISA measurement using the fluorescent probe calcein-AM, as reported previously.13

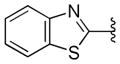

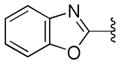

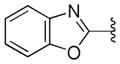

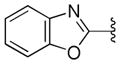

We noted from our early SAR that the hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) acetyl group is clearly important for antiprion potency of these analogs. We sought to replace it with alternative functionality that could preserve the HB (hydrogen bond) interaction with the putative target. Initially, we surmised that a five-membered heterocycle, such as a 1,3-oxazole, might be a good first choice as an acetyl isostere. Both nitrogen and oxygen atoms of the oxazole are positioned optimally and are capable of functioning as an HBA. We also synthesized and examined the effect of fused benzoxazole systems for possible increased potency (Figure 1b). While the nitrogen or oxygen of the benzoxazole ring may function as an HBA, the fused phenyl ring may also provide additional binding affinity.

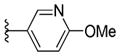

To ensure adequate coverage on the B-ring side, three aryl and heteroaryl rings including 3-pyridine, 2- thiophene, 5-methyl-2-furan were selected for these initial SAR studies. A total of 3 oxazoles (38–40) and 3 benzoxazoles (41–43) were synthesized (Table 2, Schemes 1 and 2). Almost without exception, we found that arylpiperazine analogs did not affect cell viability in ScN2a-cl3 cells (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antiprion potency (EC50) and cell viability (LC50) for selected arylpiperazine analogs.

| compd | R1 | R2 | EC50 ± SEM (μM)a | LC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | >10 | >10 | ||

| 39 | >10 | >10 | ||

| 40 |

|

|

>10 | >10 |

| 41 |

|

|

0.25 ± 0.03 | >10 |

| 42 |

|

|

3.28 ± 0.49 | >10 |

| 43 |

|

|

4.17 ± 2.19 | >10 |

| 44 |

|

|

0.38 ± 0.02 | >10 |

| 45 |

|

|

>10 | >10 |

| 46 |

|

|

0.38 ± 0.02 | >10 |

| 47 |

|

|

1.12 ± 0.58 | >10 |

Number of tests for EC50 and LC50 measurement: 3

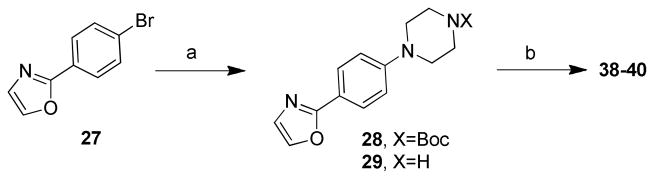

Scheme 1. Synthesis of oxazole analogs 38–40.a.

aReaction conditions: (a) (i) tert-butyl piperazinecarboxylate/t-BuOK, Pd2(dba)3 (5% mmol), BINAP (15% mmol), toluene, reflux, 12 h, 70%; (ii) TFA, DCM, RT, 3 h, 93%; (b) RCHO/HCOOH (2 equiv), anhydrous DMF, 100 °C, 3 h, 21– 37%.

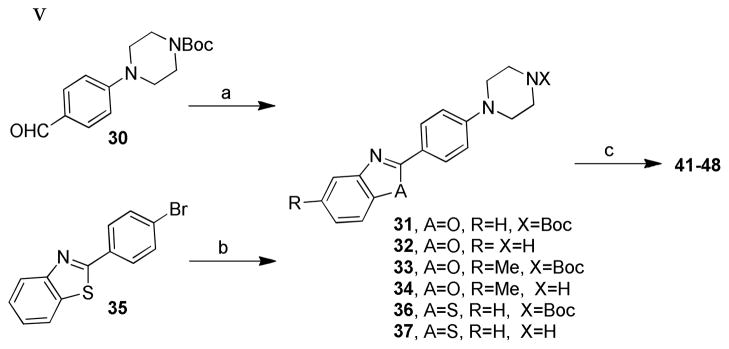

Scheme 2. Synthesis of compounds 41–48.a.

aReaction conditions: (a) (i) 2-aminophenol or 2-amino-4-methylphenol, O2, TEMPO, toluene, reflux overnight, 23– 81%; (ii) TFA/DCM, RT, 3 h, 66–77%; (b) (i) tert-butyl piperazinecarboxylate/tBuOK, Pd2(dba)3 (5% mmol), BINAP (15% mmol), toluene, reflux, 12 h, 60%; (ii) TFA/DCM, 25 °C, 3 h, 85%; (c) RCHO/HCOOH (2 equiv), anhydrous DMF, 100 °C, 3 h, 6–44%.

With respect to antiprion potency, the oxazoles 38–40 were found to be only weakly active, with EC50 values ≥10 μM, suggesting that a simple replacement of HBA group by an oxazole ring was not sufficient to maintain potency. The additional phenyl ring, as seen in the benzoxazole 41– 43 (Table 2), was beneficial to antiprion activity: all three analogs showed EC50 values <10 μM. The 3-pyridyl analog 41 had an EC50 of 0.25 μM, which was ≥13-fold more potent than both the furanyl 42 and thiophenyl 43 (Table 2). While we cannot specify the exact reason for such potency gain for 41 over other similar analogs with different B-rings, the pyridyl nitrogen atom in 41 may be situated to establish a second HB with the putative molecular target, contributing to its antiprion activity (Figure 1c).

To evaluate the BBB permeability of 41 and its potential as a CNS drug lead, we administered it in mice using a previously reported pharmacokinetic (PK) protocol.14 Rather than conducting a full PK profile, we utilized an abbreviated protocol to determine key parameters including Cmax and AUC, which are important for initial compound selection and prioritization. For initial PK studies, all compounds were administered in a single dose (10 mg/kg) by oral gavage in a formulation containing 20% propylene glycol, 5% ethanol, 5% labrosol, and 70% PEG400. Brain and plasma concentrations were measured at 0.5 h, 2 h, 4 h and 6 h after administration. The Cmax and the AUC from 0 to 6 h (AUC0-6h) for both brain and plasma were calculated. Compound 41 exhibited an excellent brain concentration (Cmax = 3.63 μM; Table 3). Its very good brain exposure (AUC0-6h = 14.2 μM*h) was approximately 4-fold higher than its plasma exposure (AUC0-6h = 4.18 μM*h), a desired characteristic in a CNS drug. Compound 41 was better absorbed considering its poor microsomal stability (t1/2 = 9.2 min, Table 3).

Table 3.

In vivo PK parameters and in vitro microsomal stability for arylpiperazines (single oral dose of 10 mg/kg).

| compd | Brain Exposure | Plasma Exposure | Microsomal Stability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (μM) | AUC (μM*h) | Cmax (μM) | AUC (μM*h) | t1/2 (min) | ||

| Mo | Hu | |||||

| 41 | 3.63 ± 0.85 | 14.20 ± 0.57 | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 4.18 ± 0.60 | 9.2 | 50.2 |

| 44 | 3.03 ± 0.53 | 14.40 ± 0.15 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 2.68 ± 0.39 | 17.3 | 34.3 |

| 46 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 1.30 ± 0.18 | 0.40 ± 0.15 | 1.17 ± 0.09 | 7.3 | 43.6 |

| 47 | 1.55 ± 0.78 | 3.03 ± 1.04 | 0.65 ± 0.38 | 1.07 ± 0.47 | 25.2 | >60 |

Encouraged by the in vitro antiprion potency and in vivo PK profile, we decided to expand the SAR around lead 41, hoping to identify more potent analogs. On the A-ring side, we synthesized a methylated benzoxazole (48, Scheme 2) to probe the size constraints of the A-ring binding pocket. Compound 48 was less potent than 41, with an EC50 of 1.65 μM, indicating that substitution of benzoxazole with a methyl group (48) was not well tolerated (data not shown).

We also examined the effect of hydrophobicity on binding affinity by replacing the benzoxazole ring (41) with a more hydrophobic benzothiazole ring (44, Scheme 2). The sulfur atom of 44 is not capable of acting as an HBA, a role assumed by the oxygen atom in the benzoxazole 41; the outcome of this compound may allow us to determine which atom (nitrogen or oxygen) in 41 is involved in the HB with the putative target. Replacing the oxygen atom in 41 with a sulfur atom (44) had little impact on antiprion activity: 44 was slightly less potent than 41, with an EC50 = 0.38 μM (Table 2). Presumably, 44 still maintains a HB with the putative target via the nitrogen atom of the benzothiazole ring.

On the B-ring side, we believe the nitrogen atom of 41 is involved as an HBA with the putative target. Addition of a substituent next to the nitrogen may perturb this interaction and thus influence the potency of these analogs. Additionally, because the nitrogen in the pyridine ring is often a target for cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes, the introduction of an adjacent group, in addition to modulating the HB potential and its potency, may also improve the metabolic stability of these pyridine analogs. Therefore, we designed and synthesized several analogs with substituents (45–47) next to the nitrogen atom of the pyridine ring (Scheme 2).

The 4-methyl analog 45 was found to be inactive, with an EC50 value >10 μM (Table 2); the B-ring binding pocket should be wide enough to accommodate a small methyl group based on early SAR derived from phenyl, thiophene, and furan analogs. As a result, the loss of antiprion potency of 45 may be due to interference of HB formation between the adjacent nitrogen and its target. In contrast, both 4-F and 4-MeO analogs (46 and 47) were active, with EC50 values of 0.38 μM and 1.11 μM, respectively (Table 2). The 4-fluoropyridine analog 46 was 1.5-fold less potent compared to its parent pyridine analog 41. This observation might be explained by a reduction in the HB strength between nitrogen and the putative target; the neighboring fluoro atom reduces the electron density on the nitrogen atom and thus weakens the strength of the HB. The 4-MeO analog 47 was 4.5-fold less potent than 41. The bigger methoxy group may hinder and decrease the HB-forming ability or strength of the nitrogen with the target.

Next, we tested the metabolic stability of compounds 44, 46, and 47 in mouse and human microsomes (Table 3). Compared to the benzoxazole 41, the benzothiazole 44 had approximately 2-fold improvement (t1/2 = 17.3 min and 9.2 min for 44 and 41, respectively) in mouse microsomes but was less stable in human microsomes (t1/2 = 34.3 min and 50.2 min for 44 and 41, respectively). The 4-fluoro analog 46 was less stable in both mouse and human microsomes compared to 41. The fluorine atom could affect the oxidation of pyridine ring but it also increases the overall hydrophilicity(ChemDraw calculated logP values of 3.86 and 4.09 for 41 and 46, respectively) of the molecule and may open the possibility of oxidation on other parts of the molecule. The methoxy analog 47 had an approximately 3-fold increase in stability in both human and mouse microsomes.

We then profiled compounds 44, 46, and 47 in in vivo PK studies as described above, focusing on their BBB permeability and brain exposure (Table 3). Both B-ring analogs 46 and 47 had poor exposure in brain and plasma compared to their parent pyridine analog 41. The benzothiazole analog 44, however, displayed a favorable PK profile compared to 41, with a 5-fold brain-to-plasma exposure ratio.

In summary, the initial arylpiperazine HTS hits with low micromolar activity (2.94 μM for 7) were optimized to yield several leads with >10-fold antiprion potency improvement. The acetyl group in the original HTS hits was replaced with the more drug-like benzoxazole ring. These efforts culminated with the identification of 41 and 44, both demonstrating robust antiprion potency, favorable PK properties, and good CNS penetration. Further evaluation of these compounds in RML- and CJD-infected animal models is underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was funded by grants from the NIH (AG021601, AG031220, AG002132, AG10470) and by gifts from the Sherman Fairchild Foundation, Larry F. Hillblom Foundation, Mike Homer Foundation, Lincy Foundation and Robert Galvin.

The authors thank Mr. Phillip Benner for preparing animal dosing and collecting samples in PK studies; Dr. Kurt Giles and the staff of the Hunter’s Point animal facility for animal studies; Drs. John Nuss and Robert Wilhelm for reviewing the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- BINAP

2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl

- CJD

Creutzfeldt- Jakob disease

- DBA

dibenzylideneacetone

- DCM

dichloromethane

- EC50

half-maximal effective concentration

- HBA

hydrogen bond acceptor

- HBD

hydrogen bond donor

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- Pd2(dba)3

Tris(dibenzylideneacetone)dipalladium(0)

- PrPC

the normal cellular isoform of the prion protein

- PrPSc

the pathogenic isoform of the prion protein

- RML

Rocky Mountain Laboratory

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- TEMPO

(2,2,6,6- Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl, or (2,2,6,6- tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxidanyl

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Footnotes

Supplementary Table 1, experimental procedures, synthetic procedures for all intermediates. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Collinge J. Molecular neurology of prion disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:906–919. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguzzi A, Sigurdson C, Heikenwaelder M. Molecular mechanisms of prion pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:11–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prusiner SB. A unifying role for prions in neurodegenerative diseases. Science. 2012;336:1511–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.1222951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Gioia L, Selvaggini C, Ghibaudi E, Diomede L, Bugiani O, Forloni G, Tagliavini F, Salmona M. Conformational polymorphism of the amyloidogenic and neurotoxic peptide homologous to residues 106–126 of the prion protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7859–7862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegde RS, Tremblay P, Groth D, Prusiner SB, Lingappa VR. Transmissible and genetic prion diseases share a common pathway of neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999;402:822–826. doi: 10.1038/45574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legname G, DeArmond SJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Pathogenesis of prion diseases. In: Uversky VN, Fink AL, editors. Protein Misfolding, Aggregation, and Conformational Diseases. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevitt CR, Collinge J. A systematic review of prion therapeutics in experimental models. Brain. 2006;129:2241–2265. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissmann C, Aguzzi A. Approaches to therapy of prion diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:321–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062404.172936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins SJ, Lewis V, Brazier M, Hill AF, Fletcher A, Masters CL. Quinacrine does not prolong survival in a murine Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease model. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:503–506. doi: 10.1002/ana.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barret A, Tagliavini F, Forloni G, Bate C, Salmona M, Colombo L, De Luigi A, Limido L, Suardi S, Rossi G, Auvre F, Adjou KT, Sales N, Williams A, Lasmezas C, Deslys JP. Evaluation of quinacrine treatment for prion diseases. J Virol. 2003;77:8462–8469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8462-8469.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima M, Yamada T, Kusuhara T, Furukawa H, Takahashi M, Yamauchi A, Kataoka Y. Results of quinacrine administration to patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17:158–163. doi: 10.1159/000076350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaemmaghami S, May BCH, Renslo AR, Prusiner SB. Discovery of 2-aminothiazoles as potent antiprion compounds. J Virol. 2010;84:3408–3412. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02145-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.May BCH, Zorn JA, Witkop J, Sherrill J, Wallace AC, Legname G, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE. Structure-activity relationship study of prion inhibition by 2- aminopyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile-based compounds: Parallel synthesis, bioactivity and in vitro pharmacokinetics. J Med Chem. 2007;50:65–73. doi: 10.1021/jm061045z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallardo-Godoy A, Gever J, Fife KL, Silber BM, Prusiner SB, Renslo AR. 2-Aminothiazoles as therapeutic leads for prion diseases. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1010–1021. doi: 10.1021/jm101250y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.