Abstract

Background/Rationale

Currently, we cannot reliably differentiate individuals at risk of cognitive decline, e.g., Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from those individuals who are not at risk.

Methods

Thirty-two subjects with MCI and 60 control (CON) subjects were tested on an innovative, sensitive behavioral assay, the Visual Paired Comparison (VPC) task using infrared eyetracking. Subjects were followed for three years after testing.

Results

Scores on the VPC task predicted, up to three years prior to a change in clinical diagnosis, those MCI patients who would and those who would not progress to AD, and CON subjects who would and would not progress to MCI.

Conclusions

The present findings show that the VPC task can predict impending cognitive decline. To our knowledge, this is the first behavioral task that can identify CON subjects who will develop MCI or MCI subjects who will develop AD within the next few years.

Keywords: memory, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, prognosis, memory impairment, cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis of amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI) refers to individuals who have memory loss with relatively preserved cognitive and daily living abilities (single domain aMCI), or memory loss together with other impaired cognitive abilities and preserved daily living abailities (multi-domain aMCI).1–3 Individuals diagnosed with aMCI, whether single- or multi-domain, are at higher than normal risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) 4–6. Although many individuals diagnosed with MCI do not convert to AD, the risk of conversion to AD can range between 6 and 25% per year 4. Currently, we cannot reliably differentiate between MCI individuals at risk of further cognitive decline from those MCI individuals who are not at risk. Moreover, we are unable to differentiate between matched control subjects who are at risk for cognitive decline and those who are not.

Although there has been considerable progress in the development of genetic, imaging, and CSF biomarkers for AD 7–8, much of this work is aimed at detecting the presence of the disease. The present study, by contrast, is aimed at predicting whether and when the disease will occur. The VPC task assesses memory function by determining whether subjects exhibit a preference for a novel picture compared to a previously viewed picture, measured by viewing time. The measure of interest is the percent time viewing the novel picture. Individuals with intact memory typically view the novel picture about 2/3 of the viewing time relative to the familiar picture. The task has been useful in detecting memory impairment both in humans and nonhuman primates with damage to the medial temporal lobe memory system 9–12. For example, the task successfully differentiated MCI subjects from both control subjects and subjects diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease 9.

While these findings have pointed to the value of the VPC task in detecting memory impairment, an interesting and important question remains. Could the VPC task be useful in predicting the onset of aMCI and/or Alzheimer’s disease by reliably distinguishing individuals at risk from those not at risk for memory decline?

The current study directly addresses this question. Our findings demonstrate that the VPC task performance scores are a sensitive early predictor of which patients diagnosed with aMCI will progress to AD during the subsequent three years, and which patients are not at such risk. Additionally, the VPC task is also a sensitive early predictor of which control subjects will progress to aMCI and which are not at such risk. Accordingly, regardless of diagnostic status at the time of testing, the VPC task accurately predicts cognitive decline.

METHODS

Subjects

Two subject groups were assessed. Group aMCI: 32 subjects diagnosed with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (mean age = 70.2; 11 single-domain aMCI subjects and 21 multi-domain aMCI subjects; 56% male), and Group CON: 60 elderly control subjects (mean age = 69.7; 33% male) (see Table 1). All participants were recruited from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Emory University, Atlanta, Ga. The study protocol and consent forms were approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained for each participant. Clinical diagnoses of aMCI, or CON were established following a standardized assessment that includes a uniform data set including neuropsychological measures described elsewhere 13–15 and consensus conference involving at least three clinicians, expert in evaluation and management of dementia. As described in Crutcher et al.,9 clinical diagnosis of MCI required evidence of a decline in baseline function in memory and possibly additional cognitive domains, with the severity of symptoms or consequent functional limitations insufficient to meet DSM-III (R) criteria for Dementia. Participants were classified as CON if they demonstrated no evidence of cognitive decline from baseline functioning based on their clinical interview and assessment. Exclusion criteria included a history of substance abuse or learning disability, dementia, neurological (e.g. stroke, tumor) or psychiatric illness. Because the VPC task involves visual memory, subjects were also excluded if: 1) they had significant ophthalmological or visual problems (e.g., detached retinas or glaucoma); 2) the eye-tracking equipment could not achieve proper pupil and corneal reflection due to physiological constraints (e.g. droopy eyelid, cataracts, pupils too small); and/or 3) poor calibration and/or they could not complete the calibration procedure. Overall, these criteria resulted in the exclusion of 14 initially recruited subjects. It is important to note that the clinicians who provided diagnoses were “blind” to the VPC performance scores, and the technicians who carried out the VPC testing were “blind” to any changes in diagnoses until the completion of the study.

Table 1.

Demographic Information/Neuropsychological Performance Scores by Group

| Measure | CON | aMCI | AD | Tukey-Kramer1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | 60 [20/40] | 32 [18/14] | 20 [10/10] | |

| Age | 69.7 (7.2) | 70.2 (8.0) | 72.2 (10.2) | ns |

| Education | 15.8 (2.6) | 15.3 (3.3) | 13.7 (3.0) | CON vs AD, P < .05 |

| CERAD2 | ||||

| Animal Fluency | 19.9 (5.0) | 16.2 (5.3) | 11.6 (4.6) | aMCI vs CON, P < .01, aMCI vs AD, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| Boston Naming Test4 | 27.6 (4.6) | 24.4 (4.1) | 17.9 (8.4) | aMCI vs CON, P < .01, aMCI vs AD, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| Mini-Mental State Exam4 | 29.2 (1.1) | 27.3 (1.8) | 22.2 (5.0) | aMCI vs CON, P < .001, aMCI vs AD, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| Word List Memory (WLM)5 | ||||

| WLM total | 22.4 (3.5) | 15.3 (4.8) | 14.4 (4.0) | aMCI vs CON, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| WLM delayed recall | 7.4 (1.7) | 3.1 (2.2) | 2.1 (1.5) | aMCI vs CON, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) | ||||

| TMT-A4 | 33.9 (11.0) | 48.5 (21.4) | 89.3 (57.9) | aMCI vs CON, P < .05, aMCI vs AD, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| TMT-B4,6 | 86.1 (36.6) | 139.7 (66.9) | 173.4 (98.9) | aMCI vs CON, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| Digit Span Forward | 8.8 (1.8) | 8.4 (1.6) | 7.7 (2.5) | ns |

| Digit Span Backward | 6.9 (2.0) | 5.7 (2.0) | 5.1 (2.1) | aMCI vs CON, P < .05, CON vs AD P < .01 |

| Clock Drawing Test | 12.3 (0.9) | 12.2 (0.8) | 7.7 (3.9) | aMCI vs AD, P < .001, CON vs AD P < .001 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale7 | 1.6 (1.9) | 2.4 (2.5) | 2.0 (2.3) | ns |

Brackets indicate [male/female]. The mean for each variable is given with standard deviations in parentheses

If the ANOVA F was significant (P < ,05), then the Tukey-Kramer post hoc pair-wise comparisons were performed and P values are given.

CERAD = Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease

Animal Fluency: 9 of the AD subjects did not complete/were not administered the test

Variances are not equal and differ significantly

WLM: 32 subjects (aMCI = 8; CON = 15; AD = 9) did not complete/were not administered the test

TMT-B 14 subjects (aMCI = 3; CON = 2; AD = 9) did not complete the test in the allotted timeframe. Scores for these subjects are not included in the TMT-B score

Geriatric Depression Scale: 4 subjects were not administered the GDS

Equipment and Stimuli

During the task, participants’ eye movements were recorded using an ASL Model 6000 chinrest-mounted camera system (Applied Science Laboratories, Bedford MA). The system sampled at 120 Hz and the gaze angle was determined by the relative positions of corneal and pupil centers. Participants were seated approximately 27 inches from a 19-inch flat panel monitor that displayed the stimuli. Eye data were recorded with ASL EYEPOS software. Stimuli consisted of black and white, high contrast clipart images measuring 4.4 inches wide by 6.5 inches high. Unique images were used for each trial.

Procedure

Participants were seated comfortably in front of the monitor and their heads positioned within a chinrest to maintain their head/viewing position. Eye position was calibrated for each subject using a nine-point array. System parameters were adjusted until the subject’s fixations accurately mapped onto the calibration points. Subjects were told that images would begin to appear on the computer screen and were instructed to look at the images “as if watching television.” During testing, the subjects eye fixations and eye movements were recorded and stored for later analyses. The entire testing procedure lasted approximately 25 – 30 minutes, including calibration.

For the VPC task, each trial consisted of two phases; a familiarization phase followed by a test phase. During the familiarization phase, two identical images were presented side-by-side on the monitor for five seconds. The monitor then went dark for a delay interval of either two seconds or two minutes. In the test phase, two images were again presented side-by-side for five seconds. One of the images was identical to the image presented during the familiarization phase and the other was a novel image. Presentation of the novel image on the left or right side was selected pseudorandomly and distributed equally. Following the test phase of the trial, the monitor was darkened for 10 seconds until the start of the next trial. To ensure subject attention for test trials that had two-minute delays, the experimenter verbally alerted all subjects that there was “approximately ten seconds before the next pair of images.”

Data Analysis

Eye fixation and movement data for each participant were extracted and analyzed off-line using ASL EYENAL software. A fixation was defined as a point of gaze continually remaining within 1° visual angle for a period of 100 msec or more. Fixations used for data analysis could occur within two designated areas of interest (AOIs): the area of the novel image, and the area of the familiar image. Eye data were characterized using percent looking time on the novel image. For this measure, the median of the ten trials at the delay interval (2-min) was selected as the representative value for each subject in order to accommodate for outliers.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between the CON and aMCI groups in age, or education. Additional analyses showed no significant differences between the CON and aMCI groups on scores in Digit Span Forward, Clock Drawing, and the Geriatric Depression Scale (all p’s > .05). As might be expected, the aMCI group was significantly impaired relative to the CON group on other measures including the Word List Memory Test, and the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). Demographic and neuropsychological performance data are also included for a group of 20 AD patients used in one of the analyses.

During the course of the study, 13 aMCI subjects had a change in diagnosis to AD, and 4 CON subjects had a change in diagnosis to aMCI (CONV Total N = 17, Table 2, upper panel). On the VPC task, the 17 subjects in the CONV group had significantly lower scores on the measure of % Looking Time on Novel during the Test phase than the NONCONV group (Table 2, lower panel). Within the CONV group, the scores for the CON and aMCI groups on % Looking Time on Novel did not differ (52.3% vs 53.7%, p > .05). In additional analyses, we compared the scores of the CONV group (separated into aMCI and CON) to those of 20 AD patients (Table 1) using the same testing paradigm. The scores on % Looking Time on Novel for the aMCI and CON groups did not differ from the score of the AD group (53.1%; p’s >.05). Finally, in separate comparisons for both the CON and the aMCI in the CONV group, their mean scores were significantly lower than the mean scores for the NONCONV (all p’s < .01).

Table 2.

Demographic Information and Neuropsychological Performance Scores for aMCI and CON subjects sorted by Conversion Status (CONV = Converters; NONCONV = Nonconverters)

| Measure | CONV | NONCONV | t tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | 17 [4/13] | 75 [56/19] | ns |

| Age | 67.4 (9.2) | 70.5 (6.9) | ns |

| Education | 15.2 (3.4) | 15.7 (2.7) | ns |

| CERAD1 | |||

| Animal Fluency | 15.5 (5.1) | 19.3 (5.2) | t = 2.71, p = .008 |

| Boston Naming Test | 25.7 (3.2) | 26.3 (3.7) | ns |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | 27.4 (1.8) | 28.8 (1.5) | t = 3.27, p = .002 |

| Word List Memory (WLM)2 | |||

| WLM total | 14.7 (4.3) | 21.4 (4.5) | t = 5.18, p < .0001 |

| WLM delayed recall | 3.4 (2.0) | 6.6 (2.5) | t = 4.67, p < .0001 |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) | |||

| TMT-A | 51.7 (20.3) | 36.2 (14.7) | t = 3.63, p = .0005 |

| TMT-B3,4 | 140.9 (75.1) | 95.6 (45.6) | t = 3.15, p = .002 |

| Digit Span Forward | 8.3 (1.7) | 8.7 (1.8) | ns |

| Digit Span Backward | 5.9 (2.4) | 6.7 (2.0) | ns |

| Clock Drawing Test | 12.0 (0.9) | 12.3 (0.9) | ns |

| Geriatric Depression Scale5 | 2.9 (2.7) | 1.6 (1.9) | t = 2.18, p = .032 |

|

| |||

| Eye tracking variables (2-min delay) | |||

| Familiarization phase | |||

| Total number of fixations | 14.7 (1.9) | 14.4 (2.3) | ns |

| Total Looking Time (secs) | 3.9 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.5) | ns |

| Test phase | |||

| % Looking Time on Novel | 53.3 (7.8) | 68.9 (8.6) | t = 6.82, p < .0001 |

| Total number of fixations | 13.6 (2.5) | 13.6 (2.4) | ns |

| Total Looking Time (secs) | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.5) | ns |

Brackets indicate [CON/aMCI]; The mean for each variable is given with standard deviations in parentheses

CERAD = Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease

WLM: 23 subjects (CONV = 2; NONCONV = 21) were not administered the WLM test

indicates the variances are not equal and differ significantly

TMT-B: 5 subjects (CONV = 1; NONCONV = 4) did not complete the test in the allotted timeframe. Scores for these subjects are not included in the TMT-B score

GDS: 4 subjects (CONV = 1; NONCONV = 3) were not administered the GDS

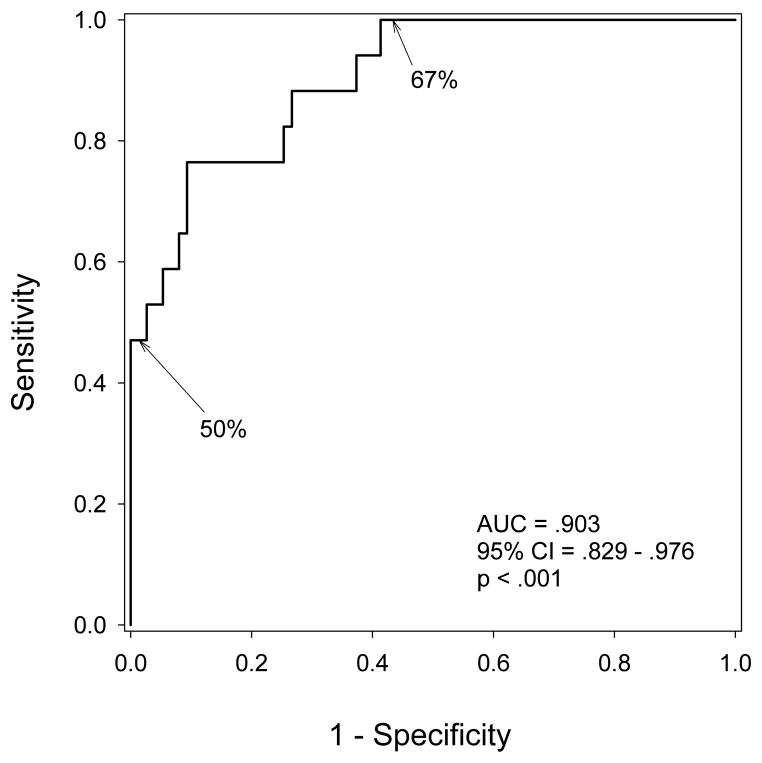

A ROC curve (Figure 1) was generated using the VPC scores for all 92 subjects classified by two categories (CONV versus NONCONV), based on whether or not a subject’s diagnosis had worsened during the three years following VPC testing. The area under the curve is 0.903, which indicates the VPC task can powerfully discriminate between subjects who will convert and those who will not convert to aMCI/AD.

Fig. 1. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve for the VPC task shows that the task powerfully discriminates between subjects who will convert and those who will not convert to aMCI/AD.

The 2-min delay scores from the VPC task for all participants (N=92) divided into two groups (converters = 17, and nonconverters = 75) with group designation based on diagnosis at time of writing (up to three years from testing). The 50% and 67% on the graph indicate the cut points in the score ranges. AD indicates Alzheimer’s disease; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; VPC, Visual Paired Comparison.

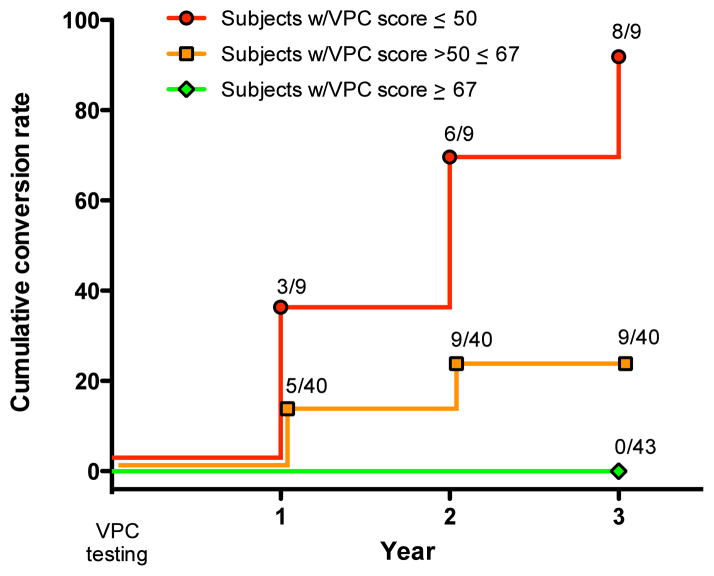

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between 3 ranges of scores on the VPC task and time to subsequent conversion to aMCI/AD. All but one of the subjects who scored <50% on the VPC task converted to AD or aMCI within three years of testing. For subjects with scores > 50% but less than 67% there was less risk for conversion to aMCI or AD. Importantly, individuals with scores > 67%, regardless of whether they were categorized as CON subjects or aMCI patients, were at zero risk for further cognitive decline within three years of testing.

Fig. 2. Cumulative proportion of subjects whose diagnosis changed across time based on their VPC 2-min delay score.

The colors delineate three ranges of scores: Red (<50% novelty preference); Orange (novelty preference between 50% and 67%); Green (>67% novelty preference). The left axis indicates percent of subjects whose diagnosis converted from aMCI to AD (n=13), or from CON to aMCI (n=4; at the time of writing, one of these four subjects has converted to AD). Log-rank p<0.001. AD indicates Alzheimer’s disease; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; CON, control; VPC, Visual Paired Comparison.

A Cox regression model revealed that a low VPC score was a significant predictor of conversion (HR=0.834 per percent, 95% CI = 0.739–0.941, p=0.003) while neither baseline diagnostic category (p=0.350) nor the interaction (p=0.221) predicted conversion, indicating that VPC score was not differentially predictive across diagnostic groups.

DISCUSSION

The present results make several points regarding the usefulness of the VPC task. First, the scores on the VPC task predicted change in diagnosis from aMCI to AD or from CON to aMCI, for some individuals up to three years before a change in clinical diagnosis. Thus, these new findings suggest that performance on the VPC task serves as a powerful prognostic indicator of looming cognitive decline.

Second, in the present study, the distinction between patients with single or multi-domain aMCI was irrelevant to the prognostic capability of the VPC task. That is, in the aMCI group, the percent of single-domain subjects that converted (36%), was not different than the percent of multi-domain subjects that converted (43%, p = 0.72). Moreover, a low performance score on the VPC task was predictive of later conversion without regard to whether the subjects were in the aMCI or CON groups. This is particularly relevant since one subject in the CON group, with a low score on the VPC task, was diagnosed with aMCI, and subsequently with AD, within the timeframe of this study.

Third, normal performance on the VPC task has been shown to require the integrity of the medial temporal lobe memory system9–12. Accordingly, the VPC task might prove useful in predicting onset and progression of memory dysfunction that is linked to several other medical conditions where disruption of the medial temporal lobe memory system could occur, e.g., depression, autism spectrum disorder, and HIV/AIDS.

Fourth, no matter the disease, early detection is an important strategy for effective therapeutic intervention. Because the VPC task can detect oncoming cognitive decline up to three years sooner than standard clinical diagnostic approaches, intervention could both begin sooner, when the brain is less compromised, and could be more effective than it would be later in the course of the disease. This kind of information can be crucial in order to inform planning and treatment options for the individual, the family, and the clinician.

Fifth, few effective interventions are available to significantly alter the course of decline associated with AD. Nevertheless, a three-year early warning about the potential onset of AD could give individuals and families an important window of time to prepare for the future. While other neuropsychological tests have some predictive value16–18, none approximate the demonstrated predictability of the VPC task.

Finally, there has been controversy regarding the nomenclature and the clinical utility of MCI as a diagnostic category 2–3. That is, whether MCI is truly an independent diagnostic category and a predictor of oncoming AD, or simply an early form of AD itself 1–3. The findings here suggest that the VPC task is predictive of worsening cognition without regard to diagnostic category at the time of testing, i.e., no matter whether the diagnosis was aMCI or CON. Further research using the VPC task could help clarify the utility of MCI diagnosis for predicting the onset of cognitive decline. Additional research with the task could also help inform the selection of individuals for clinical trials as well as help identify who might benefit most from emerging treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant AG 025688, Yerkes NPRC Base Grant RR000165 (now ORIP/OD P51OD11132), and a Robert W. Woodruff Health Science Award from Emory University

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Zola and Ms. Manzanares are inventors on Emory University’s patent of the technology used in this manuscript and are entitled to licensing fee and royalties from Neurotrack Technologies, Inc, which is developing products related to the research described in this paper. In addition, these authors are Founders of Neurotrack Technologies, Inc and they [and Emory University] own equity in the company. The other authors report no disclosures or competing financial interests.

Portions of this article were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, Vancouver, Canada, July 2012

Contributor Information

S.M. Zola, Yerkes National Primate Research Ctr, Emory University 954 Gatewood Rd NE, Atlanta, GA 30329; Dept of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA; Atlanta VA Medical Center, Atlanta, GA.

C.M. Manzanares, Email: cmanzan@emory.edu, Yerkes National Primate Research Ctr, Emory University 954 Gatewood Rd NE, Atlanta, GA 30329

P. Clopton, Email: pclopton@ucsd.edu, VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA.

J.J. Lah, Email: jlah@emory.edu, Department of Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

A.I. Levey, Email: alevey@emory.edu, Department of Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

References

- 1.Dubois B, Albert ML. Amnestic MCI or prodromal Alzheimer’s disease? Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:246–248. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, et al. Mild cognitive impairment – beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allegri RF, Glaser FB, Taragano FE, Buschke H. Mild cognitive impairment: believe it or not? Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:357–363. doi: 10.1080/09540260802095099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [Erratum, Arch Neurol 1999;56: 760] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Geda YE, Ivnik RJ, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice Parameter: Early detection of dementia: Mild Cognitive Impairment (an evidence-based review) Neurology. 2001;56:1133–1142. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riverol M, Lopez OL. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. 2011;2:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2011.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Praticò D. Alzheimer’s Disease and the Quest for its Biological Measures. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012 Jun 12; doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129023. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crutcher MD, Calhoun-Haney R, Manzanares CM, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Zola SM. Eye tracking during a visual paired comparison task as a predictor of early dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24:258–266. doi: 10.1177/1533317509332093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zola SM, Squire LR, Teng E, Stefanacci L, Buffalo EA, Clark RE. Impaired recognition memory in monkeys after damage limited to the hippocampal region. J Neurosci. 2000;20:451–463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00451.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manns JR, Stark CE, Squire LR. The visual paired-comparison task as a measure of declarative memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12375–12379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220398097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachevalier J, Brickson M, Hagger C. Limbic-dependent recognition memory in monkeys develops early in infancy. Neuroreport. 1993;4:77–80. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199301000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, DeCarli C, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, Deitrich WD, Jacka ME, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, Ferris S, Graff-Radford NR, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle SH, Cauley JA, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M. Patterns of cognitive decline in presymptomatic Alzheimer disease: A prospective community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:853–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxton J, Lopez OL, Ratcliff G, Dulberg C, Fried LP, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer disease: Neuropsychological test performance 1. 5 to 8 years prior to onset. Neurology. 2004;63:2341–2347. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147470.58328.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabert MH, Manly JJ, Liu X, Pelton GH, Rosenblum S, et al. Neuropsychological prediction of conversion to Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:916–924. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]