Abstract

Recent development of drugs that target specific pathways in tumors has increased the scientific interest in studying drug effects on tumor tissue. As a result, biopsies have become an important part of many early phase clinical trials. The performance of non-diagnostic tumor biopsies for research purposes raises a number of technical and ethical concerns. Many of these concerns arise from the performance of a potentially harmful procedure with no potential benefit to the patient. This issue is complicated by the uncertainty of whether performing biopsies in irradiated fields adds significant risk, primarily due to concerns about wound healing after irradiation. This article reviews the clinical, scientific, and ethical considerations involved in performing non-diagnostic tumor biopsies in competent adults for research purposes, with a focus on biopsies performed in the setting of therapeutic irradiation. Recommendations regarding the inclusion of non-diagnostic research biopsies in irradiated tissue in clinical research with competent adults are also discussed in detail.

Introduction

The development of high throughput technologies and the introduction of drugs targeting specific pathways in tumors have increased incorporation of research biopsies into clinical trials, prompting a restructuring of trial design and a reevaluation of the ethics of performing biopsies for research purposes only1–3. The addition of radiotherapy adds complexity to the issue because of the potential for impaired wound healing. This article reviews clinical, scientific, and ethical considerations of performing non-diagnostic research biopsies in irradiated tissues.

Clinical and Scientific Considerations

Clinical Trial Design for Targeted Therapies

Targeted agents are being combined with radiation and other cytotoxic agents to enhance treatment efficacy. Although many anti-cancer agents act on processes important in growth and metabolism, these novel agents target specific signal transduction or biological processes preferentially activated in malignant cells. In clinical trials, biopsies may be used to determine a target’s presence and its modulation by the investigational agent, radiation, and/or chemotherapy.

Early phase trials for traditional cytotoxic cancer therapies focus on determination of a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) through dose-escalation studies. Trials for targeted agents often aim to identify a biologically active dose or optimal biologic dose rather than the MTD. To accomplish this, investigators must define pharmacological effects of an investigational drug through evaluation of the pathway it targets. This must initially be done with assays of tumor tissue, requiring serial biopsies during treatment.

Biopsies in Early Phase Clinical Trials for Targeted Agents

Clinicians rely on tumor biopsies for diagnosis, staging, restaging, and to clarify prognosis4. Biopsies are not widely performed for research purposes only. However, when evaluating targeted agents, biopsies are becoming necessary to assess target modification. Multiple logistical considerations are involved when incorporating non-diagnostic biopsies into trials.

Because of the need to assess a target’s presence, baseline activity, and changes with therapy, one tissue sample will usually not be sufficient to evaluate target modulation by an investigational agent. Usually, analysis of biopsies performed before and after delivery of the targeted agent will be required in order to assess target modulation. The number of biopsies required to evaluate an investigational drug’s effects may be increased by its use in combination with chemotherapy and radiation since these may alter a target’s expression or the drug’s concentration within the tumor.

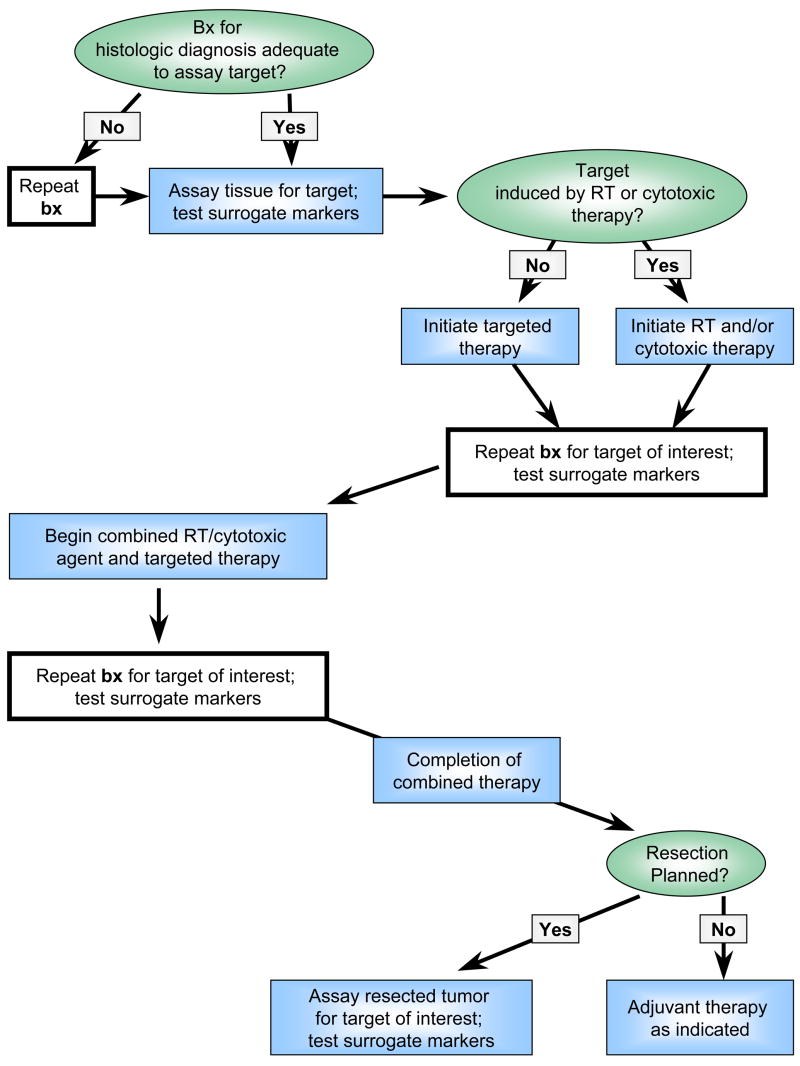

For example, consider the use of an inhibitor of the DNA repair enzyme poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)5. Investigators can measure effects of PARP inhibitors by assaying PARP activity in tumor tissue obtained before and after treatment6. PARP inhibition is probably most effective after damaging tumor DNA with radiation or chemotherapy. To study PARP inhibition in this setting, suitable tissue from prior biopsies could be evaluated before initiation of therapy to obtain baseline measurements of PARP activity. In some circumstances, specialized assays require fresh or specially processed tissue, necessitating a new baseline biopsy. A second biopsy would be needed after administration of the initial therapy (PARP inhibitor, radiation, or chemotherapy) to measure changes in PARP activity. A final biopsy would measure the PARP inhibitor’s effect in combination with radiation and/or chemotherapy. Thus, at least three biopsies would be required to evaluate target modification. A proposed trial design for combining cytotoxic and targeted therapies is found in Figure 1. If radiation or chemotherapy induces a target, they are delivered first followed by repeat biopsy and initiation of the investigational agent.

Figure 1.

Proposed clinical trial design to evaluate targeted agents in combination with radiation or other cytotoxic therapies. Bx = biopsy.

Whenever possible, less invasive imaging technologies and surrogate assays of biomarkers in biological fluids should be incorporated into early phase trials to identify alternatives to biopsy. Surrogate assays must be validated by correlative studies with tumor tissue and should be sensitive to target alterations in the tumor. Numerous factors preclude early substitution of surrogate markers for biopsies. Non-tumor samples might not express the target, or might express it differently than tumor. Additionally, variations in the tumor microenvironment might alter drug activity or concentration compared to non-tumor samples.

Risks of Tumor Biopsy in Unirradiated Tissue

For biopsies, a delicate balance exists between acquiring sufficient tissue for analysis and minimizing potential risks including bleeding, infection, anesthesia reactions and site-specific complications (i.e. bowel perforation with colonoscopic biopsy or pneumothorax with biopsies near lung). Many factors can alter risks including the type of biopsy (i.e. fine needle aspiration, core, or incisional), the biopsy location, and the type of guidance.

Data exist regarding site specific rates of complications from biopsy for diagnostic purposes. The tolerability of medically indicated, repeat biopsies has also been reported for select disease sites. Studies of prostate cancer requiring numerous repeat core biopsies of the prostate have shown low rates of serious complications (approximately 0.1%)7,8. Clinicians are comfortable obtaining medically indicated biopsies because the benefits of diagnostic information obtained outweigh biopsy risks. However, for non-diagnostic research biopsies, there is no prospect of medical benefit to compensate for the risks.

In addition to traditional complications, some investigators have concerns about “seeding” along biopsy tracts although this is extremely uncommon9,10. Two studies of 68,346 and 9,783 transthoracic biopsies found biopsy tract seeding in 0.012% and 0.061% respectively11,12. These exceptionally low rates should minimize concerns about tumor seeding except in histologies with known predilection for seeding such as sarcoma, mesothelioma, and hepatocellular carcinoma13. Investigators may consider including this uncommon risk in the informed consent.

When assessing and justifying non-diagnostic research biopsies pain, discomfort, and psychological effects are also important. Patients experience wide ranges of pain during biopsy. Many studies have evaluated pain with different biopsy types, instruments, techniques, positioning, and anesthesia with the goal of minimizing associated pain. In addition to pain, men surveyed after prostate needle biopsies identified issues such as fear of results, waiting for results, the thought of the test as troublesome issues14. Patients receiving non-diagnostic biopsies would obviously not be anxious for results, but the thought of undergoing each additional biopsy may be distressing.

Most candidates for early phase oncology trials involving non-diagnostic biopsies have had biopsies prior to giving consent. This might decrease enrollment if prior biopsies were unpleasant. In a survey of patients with various cancer sites who received previous biopsies, 36% said that mandatory non-diagnostic research biopsies would deter them from trial participation1. On the other hand, investigators can have confidence that many patients truly understand discomforts associated with biopsies through personal experience.

Risks of Biopsy in Irradiated Tissue

Irradiation can alter wound healing, potentially increasing complications after biopsy such as delayed healing, infection, dehiscence, fistula formation, and necrosis15–18. Wound healing complications in an irradiated field correlate with comorbidities, dose, site, and time from irradiation to surgery16,19–21. Despite potential complications, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, is performed frequently with small or no additional risk of surgical toxicities22,23. Additionally, diagnostic biopsies are routinely performed in treatment fields prior to radiation. This supports the concept that biopsies of irradiated tissue can be performed with minimal complications.

Few studies have reported complications associated with biopsies in irradiated fields. Clinical trials that performed biopsies during or within four months of finishing radiotherapy were identified with a literature review (Table 1). PubMed and Google Scholar searches were performed using combinations of the terms “biopsy, radiation, clinical trials, sequential biopsies, and repeat biopsy.” Identification of relevant studies was challenging because describing biopsy complications was usually not a study endpoint. Nevertheless, 29 studies, with 2,160 patients, were identified in which various tumors were biopsied. There were wide variations in radiation dose, biopsy type and biopsy timing relative to radiotherapy. Most tumors were either directly accessible to biopsy or accessible by endoscopy. Biopsies were almost exclusively less invasive needle or mucosal biopsies rather than more invasive incisional or excisional biopsies, although some series performed more invasive procedures in breast, bone marrow and lung (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of studies reviewed that performed diagnostic or non-diagnostic biopsies immediately before, during or after radiation therapy.

| Site | Ref | Cancer Type | Bx Type and Site | #Patients | RT Characteristics | Bx Timing in Relation to RT | Reported AE of Bx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genitourinary | 39 | Bladder | Repeat TURBT | 25 | 54 Gy + 5.4 Gy boost to bladder | Before: TURBT; After: 6–8 wks post CRT | AE reported- None attributed to bx |

| 40 | Bladder | Cystoscopy with bx of lesions after initial TURBT | ≥ 62 | Range: 50–57.5 Gy. | Before: TURBT; After: within 4 mos | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 41 | Bladder | Cystoscopy & tumor bed bx after initial TURBT | 47 | 40.8 Gy BID; concomitant boost days 1–16 ± additional 24 Gy | Before: TURBT; During: 3 wks post initial CRT; After: within 6 wks of all treatment | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 42 | Bladder | Cystoscopy & tumor bed bx after initial TURBT | 97 | Initial = 39.6 Gy; Total = 63.8 Gy | Before: TURBT; During: after initial CRT; After: within 3 mos of completion of CRT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 43 | Bladder | Cystoscopy & tumor bed bx after initial TURBT | 33 | Initial= 24 Gy; Total= 44 Gy | Before: TURBT; During: 4 wks post initial CRT; After: within 3 mos | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 44 | Bladder | Repeat TURBT | 39 | Negative margins= 54 Gy; Positive margins = 59.4 Gy | Before: TURBT; After: 6–8 wks post CRT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 45 | Bladder | Cystoscopy & tumor bed bx after initial TURBT | 51 | Initial = 39.6 Gy; Total= 64.8 Gy | Before: TURBT; During: 4 wks post initial CRT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 46 | Bladder | Cystoscopy & tumor bed bx after initial TURBT | 42 | Initial = 39.6 Gy; Total= 64.8 Gy | Before: TURBT; During: 2 wks post initial CRT | No comments on AE | |

| 47 | Bladder | Cystoscopy & tumor bed bx after initial TURBT | 85 | Initial = 39.6 Gy; Total= 64.8 Gy | Before: TURBT; During: 2 wks post initial CRT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 48 | Cervical | Cervical tumor bx | 40 | 4 different regimens; Medians range from 40 to 96 Gy. | Before: pretreatment bx; During: after 1 week of RT (5 fractions = 9 Gy) | No comments on AE | |

| 49 | Cervical | Cervical tumor bx | 41 | EBR 45 Gy ± Brachytherapy (27 Gy) ± additional EBR ± CT | Before: pretreatment bx; During: every week on treatment | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 50 | Cervical | Cervical tumor bx | 39 | 50.6 Gy + high dose brachytherapy | Before: pretreatment bx; During: after 1 week of RT (5 fractions = 9 Gy) | No comments on AE | |

| 51 | Cervical | Cervical tumor bx | 20 | 50.6 Gy + high dose brachytherapy(22–24 Gy) | Before: pretreatment bx; During: after 1 week of RT (5 fractions = 9 Gy) | No comments on AE | |

| Head and Neck | 52 | Esophageal | Esophagoscopy with non-mandatory bx | ≥14 | 60 Gy ± brachytherapy boost(7–28 Gy) | Before: diagnostic bx; After: 1–2 mos after RT | AE reported- None attributed to bx |

| 53 | PSC | Panendoscopy and tumor bx | 25 | Range: 68–74 Gy | After: 2 mos after RT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 54 | Head/Neck | Bx of irradiated region | 25 | Range: 66–74 Gy | After: 8 wks after RT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 55 | Head/Neck | Bx of irradiated region | 38 | Initial= 45 Gy; Total= 72 Gy | During: 5 wks after RT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 56 | Head/Neck | Bx of irradiated region | 28 | Initial= 50 Gy; Total= 68–72 Gy | After: 8 wks post initial CT; 14 wks post CRT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 57 | NPC | Flex endoscopy and tumor bx | 63 | IMRT= 66 Gy + ICB boost (12Gy) for T1–2a; ± conformal boost (8 Gy) for T2b-4 | Before: pretreatment bx; After: 6–12 wks post RT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 24 | NPC | Endoscopy and ≥ 6 irradiated nasopharynx bx | 803 | Median= 61 Gy; Range = 59.5–74 Gy | After: immediately post RT, repeated every 2 wks until bx were negative | No AE in median 47 mos of follow-up | |

| 58 | NPC | Bx of irradiated nasopharynx | 25 | ≥70 Gy | After: within 4 mos | No comments on AE | |

| Lung | 59 | NSSLC | EUS-FNA of mediastinal lymph nodes | 93 | RT with carboplatinum-based CT | Before: before CRT; After: 5.9 wks (4.1–10.3) post CRT | No comments on AE |

| Gastrointestinal | 60 | Rectal | Proctoscopy with multiple rectal bx | 81 | 3 fields: 50 Gy, 53 Gy and 56 Gy | Before: before CRT; After: 4 wks after CRT | No comments on AE |

| 61 | Rectal | Proctoscopy with rectal bx | 22 | EBR | Before: 12 days after bevacizumab infusion, immediately before RT | No comments on AE | |

| 62 | Anal | Full thickness anal bx, pretreatment inguinal node aspiration and/or excision | 262(initial); 22(repeat) | Initial= 45 Gy; (50.4 Gy boost for positive nodes); Salvage =9 Gy | Before: nodal bx; During: 4–6wks after initial CRT; After: 6 wks after salvage RT | AE reported- None attributed to bx | |

| 63 | Pelvic | Proctoscopy with multiple rectal bx | 33 | Range: 54–66 Gy | Before: pretreatment bx;During: 2 wks and 6 wks during RT | No comments on AE | |

| 27 | Pelvic | Sigmoidoscopy and anterior and posterior rectal wall bx | 9 | Range: 50–52.6 Gy | During: wks 2 and 4 during RT; After: 4 and 12 wks post RT | Ulceration and failure of healing at bx sites | |

| Breast | 26 | Breast | Both open (n=27) and percutaneous needle (n=11) breast bx after breast preserving surgery | 31 | 50 Gy ± 500 to 3000 cGy Boost | Open = 2–81 mos after RT; Needle= 1–52 mos after RT | 30% open bx had infection/delayed healing; No AE in needle bx |

| Other | 64 | Breast (1); Melanoma (2) | Skin (n=2), breast (n=1), melanoma (n=1), and bone marrow (n=1) bx | 3 | Variable RT doses and treatment | Before and during RT | No comments on AE |

Abbreviations: bx = biopsy; RT= Radiation Therapy; CRT= Chemoradiotherapy; EBR= External Beam Radiation; IMRT= Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy; ICB= Intracavitary Brachytherapy; Gy= Gray; NPC= Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma; NSSLC= Non Small Cell Lung Cancer; PSC= Pyriform Sinus Carcinoma; TURBT= Transurethral Resection of the Bladder Tumor; BID= Twice Daily; AE= Adverse Events

Table 2.

Summary of results from studies reviewed. Bx=Biopsy.

| Bx Site (Tumor Site if different) | # of Studies | # of Patients | Rest Time to Bx | RT Dose Received at Bx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | 9 | ≥ 481 | 2–8 wks. | 24–64 Gy |

| Cervix | 4 | 140 | Immediate | 9–74 Gy |

| Esophagus | 1 | ≥14 | 4–8 wks | 60–88 Gy |

| Oropharynx / Nasopharynx | 7 | 1007 | Immediate-16 wks. | 45–78 Gy |

| Mediastinal Lymph Nodes (Lung) | 1 | 93 | 4–10 wks. | Not Reported |

| Anus / Rectum / Colon | 5 | 391 | Immediate-12 wks. | 25–66 Gy |

| Breast | 2† | 32† | immediate- 81 months | 0–80 Gy |

| Skin (Breast, Melanoma) | 1† | 2† | Immediate | Not Reported |

| Bone Marrow (Melanoma) | 1† | 1† | immediate | Not Reported |

| All Sites (n = 9) | 29 | 2160 | Immediate-16 weeks* | 0–88 Gy |

One study included 2 breast cancer patients who had breast biopsies (1 also had skin) and one melanoma patient who had a bone marrow and skin biopsies

One study performed biopsies up to 81 months

The quality of data reported was suboptimal for several reasons. First, no studies were specifically designed to describe biopsy risks in irradiated tissue. Sixteen of 29 studies reported adverse events (AEs), but did not clearly report active evaluation for biopsy complications. Another 10 studies did not mention AEs within the trial. At least three studies actively evaluated patients for biopsy complications.

Taking this into consideration, 17 of 2,160 patients (<1%) were reported to have biopsy complications. The largest study included 803 nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients receiving sequential mucosal biopsies after irradiation24. Patients reported discomfort but had no other complications despite regular evaluation over a median follow-up of 47 months24,25. Two studies reported complications directly attributable to biopsy. One reviewed 31 patients with various biopsy types after conservative surgery and radiation for early stage breast cancer26. Eight of 27 open biopsies (30%) were associated with infections and delayed healing, compared to none of 11 needle biopsies. This series included an unknown number of patients biopsied beyond four months after radiotherapy. Another study performed sequential rectal biopsies before, during and after pelvic radiotherapy in nine patients27. All patients had mucosal ulceration and one had contact bleeding at previous biopsy sites. It is uncertain if delayed healing was clinically significant because gastrointestinal toxicities are common with pelvic radiotherapy. Additionally, the lack of an unirradiated control population and small sample size complicate interpretation of these data.

Results of this review accentuate the poor reporting of AEs associated with biopsies in clinical trials. How often these biopsies are performed in clinical practice is unknown. There is an important need to collect more data regarding AEs associated with biopsies performed in irradiated tissues. Investigators should incorporate and report AE endpoints for research biopsies in clinical trials.

Despite limited information, these data suggest it is possible to perform biopsies with acceptable risk in some scenarios when radiation is part of therapy. Tumors easily accessible to biopsy like cervical, nasopharyngeal, bladder and gastrointestinal cancers have less risk than less-accessible tumor sites. Less invasive needle and mucosal biopsies are likely to yield fewer complications than open biopsies. As more clinical studies include and report toxicities of these biopsies, recommendations may be clarified.

Ethical Considerations

Risk-Benefit Assessment

In modern medicine the dictum primum non nocere, “first, do no harm” is appreciated more for its figurative meaning than its literal interpretation28. Procedures like liver biopsies, bronchoscopy, and venipuncture are routinely performed in spite of risks and discomforts because the benefits are thought to outweigh the potential harm. Nonmaleficence, doing no harm to a patient, is weighed against beneficence, doing good for a patient. This balance is evident in oncology where practitioners administer toxic therapies hoping to prolong a patient’s life and/or relieve suffering.

In clinical research, risks of interventions must be justified by anticipated medical benefits to participants and/or knowledge to be gained. Performing non-diagnostic research biopsies raises ethical concerns because patients undergo a potentially harmful procedure with no direct benefit. The additional risk of tumor biopsies in clinical trials has been evaluated2,3. Trials of this nature have been performed and are currently underway implying that many investigators and institutional review boards consider risks of certain biopsies to be low enough to warrant their use in clinical trials if they are scientifically justified and performed with informed consent.

The primary question in this discussion is whether performing biopsies in irradiated tissue confers additional risk that goes beyond acceptable levels of risk for medically unnecessary procedures. Surgical and biopsy data, as well as knowledge of radiation effects on wound healing, suggest that biopsies in irradiated fields may have more risk than in non-irradiated fields even though the clinical importance of this is not well defined. There is reason to believe based on limited information that less invasive biopsies of some irradiated tumors can be performed with acceptable risk in clinical trials. These should be limited to biopsies considered appropriate to perform in trials that do not involve radiotherapy. It is unclear to what extent radiotherapy increases risks of these biopsies and more information is needed.

Measures should always be taken to minimize the potential for harm to patients. First, non-diagnostic biopsies should only be included in trials when necessary scientific information cannot be obtained with less invasive studies. Justification for biopsies should be progressively more compelling as risks for desired biopsies increase. Participants facing high risks due to tumor location or other factors should be excluded. The number of biopsies should be minimized through careful sequencing of therapies, and by assaying previously collected tissue when possible. Invasiveness should be minimized whenever possible by performing mucosal or needle biopsies rather than open biopsies and by sampling the most accessible tumor if multiple are present. More invasive biopsies should be performed with adequate time for wound healing while minimizing delays and interruptions in therapy. Finally, investigators should incorporate candidate surrogate assays or imaging into clinical trials to identify less invasive alternatives to biopsies for use in future trials.

Informed Consent

The only scenario when competent adults can participate in research with more than minimal risk, without direct benefit is with informed consent. A comparable example in clinical practice is when individuals become living donors of kidneys, liver, and bone marrow to benefit transplant recipients. Federal regulations allow research subjects to accept risks with no chance of personal benefit and with no threshold on the risk a competent adult can accept, provided the information gained justifies the risks29. As such, competent adults can consent to non-diagnostic biopsies in clinical trials although there are some special considerations30–32.

Patients often overestimate potential benefits from clinical trial participation1,33,34. A patient could possibly minimize a biopsy’s risk because of perceived benefits from investigational therapies. The tendency of patients to confuse research participation with standard medical care has been termed the therapeutic misconception35,36. This might occur if patients assume that biopsies are routine medical care and will somehow benefit them. To counteract this misconception a distinction should be made between the investigational agent and the biopsies. Investigators can emphasize that biopsies are performed strictly for scientific purposes by utilizing a separate consent document for the research biopsy, Consideration should be given to short tests of comprehension or other measures to ensure understanding prior to accepting consent. Other ways to clearly separate trial components include using a provider other than the researcher to obtain consent37 or by offering financial compensation, which is routinely used in other types of non-therapeutic research. Payment for non-diagnostic research biopsies would reinforce the fact that these procedures are not intended for the medical benefit of participants. If the payment is modest it would not raise any ethical concerns about coercion or undue inducement.

Patients participating in any trial or procedure accept some degree of uncertainty. They are given information regarding likelihood of complications, but cannot know if they will experience complications. Patients undergoing non-diagnostic research biopsies in irradiated fields as part of a trial should understand the uncertain potential for biopsy complications.

Mandatory versus Optional Biopsies

Some have proposed that non-diagnostic research biopsies should be optional rather than mandatory, especially if the scientific value of the biopsy is not yet established 3. The primary ethical argument against mandatory biopsies is that they are potentially coercive. The Belmont Report defines coercion as occurring “when an overt threat of harm is intentionally presented by one person to another to obtain compliance.”38

For clinical trials in which biopsy is an indispensable component there is no threat or penalty. Rather, the biopsy is a non-optional condition on the offer to receive experimental treatments, which are not otherwise available. Those who refuse the package of experimental treatment and mandatory biopsy are not denied medically indicated treatment. Since patients are not entitled to receive investigational treatments outside of clinical trials, it is neither coercive nor unfair to make biopsies mandatory when they are necessary to evaluate safety or efficacy; however, the risk of these biopsies and their necessity should be carefully weighed by the investigators and the institutional review board approving the clinical trial to ensure that they are in fact necessary. When biopsies are not deemed necessary to assess efficacy or safety, they should be optional. Nevertheless, patients with advanced cancer are often desperate and may perceive a greater chance of benefit than actually exists. Thus it is important to convey an accurate understanding of the typically small chance of benefit from early phase trials.

Optional research biopsies pose logistical problems. Specific numbers of patients are needed in early phase trials to evaluate effects of ascending drug doses. If biopsies are necessary to understand drug effects on a target molecule then a trial will also need defined numbers of biopsies at each dose level. Optional biopsies could result in too few patients accepting biopsies, needlessly exposing an excess of patients to an investigational drug. Conversely, if too many patients accept biopsies, an unnecessarily high number of biopsies may be performed. Either situation may be unethical

Optional biopsies may be most useful if the number of biopsies needed is much less than the number of patients receiving each dose of an investigational agent or for studying secondary endpoints. Other strategies may include mandatory biopsies for the first patients enrolled or randomization of participants to biopsy and non-biopsy groups. However, these strategies also have logistical problems and concerns about fairness. Whatever the strategy for determining which patients receive biopsies, the process should be made transparent in the informed consent document.

Conclusions

Inclusion of non-diagnostic research biopsies in clinical trials raises ethical concerns because a potentially harmful procedure is performed with no direct benefit. This issue is complicated by uncertainty about whether or not performing biopsies in irradiated fields adds significant risk. In addition, combining targeted agents with cytotoxic therapies or radiation may require multiple research biopsies, each with risks and discomforts. Nevertheless, it is ethical for patients to participate in such trials as long as potential complications are minimized. Mandatory biopsies in early phase trials of investigational agents are ethical, and are not coercive when adequate consent is obtained. The most important ethical issues in clinical trials involving non-diagnostic research biopsies are careful risk assessment and ensuring proper informed consent, which requires that patients understand that biopsies are potentially harmful with no direct benefit to them.

Recommendations regarding risk assessment of non-diagnostic research biopsies in clinical trials follows. First, risks of biopsies should be minimized by performing only scientifically necessary biopsies with minimal invasiveness. Clinical trials should obtain the maximum amount of information from a minimal number of biopsies without compromising the efficacy of therapy or significantly delaying therapy. All clinical trials that perform biopsies in combination with other therapies should actively study and report complications. The authors advocate that a reporting of AE’s from trials performing research-only non-diagnostic biopsies should be included as part of the publication review process. Finally, investigators should incorporate correlative assays of tumor tissue with candidate surrogate biomarkers and imaging that might be alternatives to biopsies in future trials of agents with similar targets.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, Office of the Director and the NIH Clinical Center.

Aaron Brown’s research year was made possible through the Clinical Research Training Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and Pfizer Inc (via a grant to the Foundation for NIH from Pfizer Inc).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, the Public Health Service, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.Agulnik M, Oza AM, Pond GR, et al. Impact and Perceptions of Mandatory Tumor Biopsies for Correlative Studies in Clinical Trials of Novel Anticancer Agents. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4801–4807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannistra SA. Performance of Biopsies in Clinical Research. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1454–1455. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helft PR, Daugherty CK. Are We Taking Without Giving in Return? The Ethics of Research-Related Biopsies and the Benefits of Clinical Trial Participation. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4793–4795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consensus Statements on Radiation Therapy of Prostate Cancer. Guidelines for Prostate Re-Biopsy After Radiation and for Radiation Therapy With Rising Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels After Radical Prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1155. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kummar S, Kinders R, Gutierrez M, et al. Inhibition of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) by ABT-888 in patients with advanced malignancies: Results of a phase 0 trial. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2007;25:3518. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji J, Redon C, Pommier Y, et al. Poly-adeninosinediphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibitors as sensitizers for therapeutic treatments in human tumor and blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2007;25:14024. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Djavan BOB, Waldert M, Zlotta A, et al. Safety and morbidity of first and repeat transrectal ultrasound guided prostate needle biopsies: Results of a prospective European prostate cancer detection study. The Journal of Urology. 2001;166:856–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichler K, Hempel S, Wilby J, et al. Diagnostic Value of Systematic Biopsy Methods in the Investigation of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Urology. 2006;175:1605–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith EH. Complications of percutaneous abdominal fine-needle biopsy. Review Radiology. 1991;178:253–258. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.1.1984314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uriburu JL, Vuoto HD, Cogorno L, et al. Local Recurrence of Breast Cancer after Skin-Sparing Mastectomy Following Core Needle Biopsy: Case Reports and Review of the Literature. The Breast Journal. 2006;12:194–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayar D, Golla B, Lee JY, et al. Needle-track metastasis after transthoracic needle biopsy. J Thorac Imaging. 1998;13:2–6. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomiyama N, Yasuhara Y, Nakajima Y, et al. CT-guided needle biopsy of lung lesions: A survey of severe complication based on 9783 biopsies in Japan. European Journal of Radiology. 2006;59:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stigliano R, Marelli L, Yu D, et al. Seeding following percutaneous diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma. What is the risk and the outcome?: Seeding risk for percutaneous approach of HCC. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2007;33:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medd JCC, Stockler MR, Collins R, et al. Measuring men’s opinions of prostate needle biopsy. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2005;75:662–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurlek A, Miller MJ, Amin AA, et al. Reconstruction of complex radiation-induced injuries using free-tissue transfer. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1998;14:337–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Boerma M, Fu Q, et al. Radiation responses in skin and connective tissues: effect on wound healing and surgical outcome. Hernia. 2006;10:502–506. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0150-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delanian S, Martin M, Bravard A, et al. Abnormal phenotype of cultured fibroblasts in human skin with chronic radiotherapy damage. Radiother Oncol. 1998;47:255–61. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokarek R, Bernstein EF, Sullivan F, et al. Effect of therapeutic radiation on wound healing. Clinics in Dermatology. 1994;12:57–70. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denham JW, Hauer-Jensen M. The radiotherapeutic injury - a complex ‘wound’. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2002;63:129–145. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Sullivan B, Gullane P, Irish J, et al. Preoperative Radiotherapy for Adult Head and Neck Soft Tissue Sarcoma: Assessment of Wound Complication Rates and Cancer Outcome in a Prospective Series. World Journal of Surgery. 2003;27:875–883. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisters PW, Harrison LB, Leung DH, et al. Long-term results of a prospective randomized trial of adjuvant brachytherapy in soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:859–868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerard J-P, Chapet O, Nemoz C, et al. Preoperative Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer With High-Dose Radiation and Oxaliplatin-Containing Regimen: The Lyon R0-04 Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1119–1124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohiuddin M, Winter K, Mitchell E, et al. Randomized Phase II Study of Neoadjuvant Combined-Modality Chemoradiation for Distal Rectal Cancer: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 0012. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:650–655. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwong DL, Nicholls J, Wei WI, et al. The time course of histologic remission after treatment of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:1446–53. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990401)85:7<1446::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sham J. Personal Communication to the Author. Bethesda, MD: Dec, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pezner RD, Lorant JA, Terz J, et al. Wound-healing complications following biopsy of the irradiated breast. Arch Surg. 1992;127:321–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420030091017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sedgwick DM, Howard GC, Ferguson A. Pathogenesis of acute radiation injury to the rectum. A prospective study in patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1994;9:23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00304295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelton JD. The Harm of “First, Do No Harm”. JAMA. 2000;284:2687–2688. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.21.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Code of Federal Regulations; DHHS. Protection of Human Subjects, Title 45 Section 46.111. 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal M, Emanuel EJ. Ethics of phase 1 oncology studies: reexamining the arguments and data. JAMA. 2003;290:1075–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.8.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grunwald HW. Ethical and design issues of phase I clinical trials in cancer patients. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:124–6. doi: 10.1080/07357900701225331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joffe S, Miller FG. Rethinking Risk-Benefit Assessment for Phase I Cancer Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2987–2990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daugherty C, Ratain MJ, Grochowski E, et al. Perceptions of cancer patients and their physicians involved in phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1062–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.5.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meropol NJ, Weinfurt KP, Burnett CB, et al. Perceptions of patients and physicians regarding phase I cancer clinical trials: implications for physician-patient communication. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2589–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glannon W. Phase I oncology trials: why the therapeutic misconception will not go away. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:252–255. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.015685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson GE, Churchill LR, Davis AM, et al. Clinical trials and medical care: defining the therapeutic misconception. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morin K, Rakatansky H, Riddick FA, Jr, et al. Managing conflicts of interest in the conduct of clinical trials. JAMA. 2002;287:78–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Belmont Report. Washington D.C., National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979

- 39.Birkenhake S, Leykamm S, Martus P, et al. Concomitant radiochemotherapy with 5-FU and cisplatin for invasive bladder cancer. Acute toxicity and first results. Strahlenther Onkol. 1999;175:97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF02742341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cowan RA, McBain CA, Ryder WD, et al. Radiotherapy for muscle-invasive carcinoma of the bladder: results of a randomized trial comparing conventional whole bladder with dose-escalated partial bladder radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagan MP, Winter KA, Kaufman DS, et al. RTOG 97-06: initial report of a phase I-II trial of selective bladder conservation using TURBT, twice-daily accelerated irradiation sensitized with cisplatin, and adjuvant MCV combination chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:665–72. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00718-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kachnic LA, Kaufman DS, Heney NM, et al. Bladder preservation by combined modality therapy for invasive bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1022–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufman DS, Winter KA, Shipley WU, et al. The initial results in muscle-invading bladder cancer of RTOG 95-06: phase I/II trial of transurethral surgery plus radiation therapy with concurrent cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil followed by selective bladder preservation or cystectomy depending on the initial response. Oncologist. 2000;5:471–6. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-6-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodel C, Grabenbauer GG, Kuhn R, et al. Organ preservation in patients with invasive bladder cancer: initial results of an intensified protocol of transurethral surgery and radiation therapy plus concurrent cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1303–9. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02771-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shipley WU, Winter KA, Kaufman DS, et al. Phase III trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with invasive bladder cancer treated with selective bladder preservation by combined radiation therapy and chemotherapy: initial results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 89–03. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3576–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tester W, Porter A, Asbell S, et al. Combined modality program with possible organ preservation for invasive bladder carcinoma: results of RTOG protocol 85-12. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:783–90. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90306-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tester W, Caplan R, Heaney J, et al. Neoadjuvant combined modality program with selective organ preservation for invasive bladder cancer: results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group phase II trial 8802. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:119–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cerciello F, Hofstetter B, Fatah SA, et al. G2/M cell cycle checkpoint is functional in cervical cancer patients after initiation of external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1390–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Durand RE, Aquino-Parsons C. Predicting response to treatment in human cancers of the uterine cervix: sequential biopsies during external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:555–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwakawa M, Ohno T, Imadome K, et al. The Radiation-Induced Cell-Death Signaling Pathway is Activated by Concurrent Use of Cisplatin in Sequential Biopsy Specimens from Patients with Cervical Cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6 doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.6.4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohno T, Nakano T, Niibe Y, et al. Bax protein expression correlates with radiation-induced apoptosis in radiation therapy for cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;83:103–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tessa M, Rotta P, Ragona R, et al. Concomitant chemotherapy and external radiotherapy plus brachytherapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer: results of a retrospective multicenter study. Tumori. 2005;91:406–14. doi: 10.1177/030089160509100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samant S, Kumar P, Wan J, et al. Concomitant radiation therapy and targeted cisplatin chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced pyriform sinus carcinoma: disease control and preservation of organ function. Head Neck. 1999;21:595–601. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199910)21:7<595::aid-hed2>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samant S, Robbins KT, Kumar P, et al. Bone or cartilage invasion by advanced head and neck cancer: intra-arterial supradose cisplatin chemotherapy and concomitant radiotherapy for organ preservation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:1451–6. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.12.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wanebo HJ, Chougule P, Ready N, et al. Preoperative paclitaxel, carboplatin, and radiation therapy in advanced head and neck cancer (stage III and IV) Semin Radiat Oncol. 1999;9:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wanebo HJGM, Burtness B, Spencer S, Ridge J, Forastiere A, Ghebremichael M. Phase II evaluation of cetuximab (C225) combined with induction paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by C225, paclitaxel, carboplatin, and radiation for stage III/IV operable squamous cancer of the head and neck (ECOG, E2303). 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kam MK, Teo PM, Chau RM, et al. Treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma with intensity-modulated radiotherapy: the Hong Kong experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:1440–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai MH, Huang WS, Tsai JJ, et al. Differentiating recurrent or residual nasopharyngeal carcinomas from post-radiotherapy changes with 18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and thallium-201 single photon emission computed tomography in patients with indeterminate computed tomography findings. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3513–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Ojha B. Restaging patients with N2 (stage IIIa) non-small cell lung cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: a prospective study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:1229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Capirci C, Rubello D, Chierichetti F, et al. Restaging after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal adenocarcinoma: role of F18-FDG PET. Biomed Pharmacother. 2004;58:451–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willett C, Duda D, Boucher Y, et al. Phase I/II study of neoadjuvant bevacizumab with radiation therapy and 5-fluorouracil in patients with rectal cancer: initial results. J Clin Oncol 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flam M, John M, Pajak TF, et al. Role of mitomycin in combination with fluorouracil and radiotherapy, and of salvage chemoradiation in the definitive nonsurgical treatment of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal: results of a phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2527–39. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hovdenak N, Fajardo LF, Hauer-Jensen M. Acute radiation proctitis: a sequential clinicopathologic study during pelvic radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1111–7. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morstyn G, Kinsella T, Hsu SM, et al. Identification of bromodeoxyuridine in malignant and normal cells following therapy: relationship to complications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984;10:1441–5. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]