SUMMARY

Background

To determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), safety, potential pharmacokinetic (PK) interactions, and effect on liver histology of trabectedin in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) for advanced malignancies.

Patients and Methods

Entry criteria for the 36 patients included normal liver function, prior doxorubicin exposure <250 mg/m2, and normal cardiac function. A 1-hour PLD (30 mg/m2) infusion was followed immediately by 1 of 6 trabectedin doses (0.4, 0.6, 0.75, 0.9, 1.1, and 1.3 mg/m2) infused over 3 hours, repeated every 21 days until evidence of complete response (CR), disease progression, or unacceptable txicity. Plasma samples were obtained to assess PK profiles.

Results

The MTD of trabectedin was 1.1 mg/m2. Drug-related grade 3 and 4 toxicities were neutropenia (31%) and elevated transaminases (31%). Six patients responded (1 CR, 5 partial responses), with an overall response rate of 16.7%, and 14 had stable disease >4 months (39%). Neither drug had its PK affected significantly by concomitant administration compared to trabectedin and PLD each given as a single agent.

Conclusion

Trabectedin combined with PLD is generally well tolerated at therapeutic doses of both drugs in pretreated patients with diverse tumor types, and appears to provide clinical benefit. These results support the need for additional studies of this combination in appropriate cancer types.

Keywords: trabectedin, ET-743, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD), sarcomas, ovarian cancer

INTRODUCTION

Trabectedin (YONDELIS®) is a synthetically derived tris, tetrahydoisoquinoline alkaloid anti-tumor agent originally discovered by isolation from the marine colonial tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata. It binds to the minor groove of DNA at the N2 position of guanine, inducing a bend toward the major groove [1, 2]. Trabectedin inhibits transcription of heat shock—inducible genes [3] and interacts with the transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair (TC-NER) system. This results in the formation of DNA strand breaks, late S and G2 phase cell cycle arrest, and p-53 independent apoptosis [4-6].

At relatively low concentrations (2-80 nm), trabectedin has shown in vitro cytotoxicity against ovarian, sarcoma, breast, melanoma, colorectal, brain, and lung cancer cell lines [7-9]. Trabectedin also inhibited the development of human tumor xenografts in mice, including melanoma, ovarian, non—small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast, and renal cell carcinomas [10-13]. Valoti and colleagues showed that trabectedin was active against xenografts, inducing prolonged regressions in early and established tumors [12].

In phase I studies, trabectedin demonstrated activity in patients with ovarian, osteosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, melanoma, endometrial carcinoma, and breast cancer [12, 14-18]. Doses evaluated included 1- to 72-hour infusions administered every 3 weeks, a 1-hour infusion daily for 5 days every 3 weeks, and a 3-hour infusion once weekly for 3 out of 4 weeks.

In early phase I and II clinical trials, trabectedin-associated dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) included reversible myelosuppression and liver enzyme abnormalities. The 2 forms of liver enzyme abnormalities were primarily acute transaminitis and a separate less frequent low-grade cholestasis. Both generally resolve by Day 15 of a 21-day cycle. The incidence of transaminitis diminishes in subsequent cycles [15, 16, 18-26].

Trabectedin has been studied in combination with doxorubicin in preclinical studies, displaying synergistic cytotoxicity in doxorubicin-resistant fibrosarcoma cell lines [27, 28]. Based upon these promising results, a phase I trial combining pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD; DOXIL®/CAELYX®) with trabectedin in patients with advanced malignancies was performed.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

Eligibility criteria included the ability to provide informed consent, patient age ≥18, and histologically documented cancer either refractory to standard therapy or appropriate for treatment with an anthracycline. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, normal liver and renal function, and normal cardiac function as determined by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) >50% without history of signs and symptoms of cardiac disease were required. All patients with reproductive potential had to agree to practice adequate contraception. Exclusion criteria included prior exposure to trabectedin, prior anthracycline exposure ≥250 mg/m2, hypersensitivity to dexamethasone, peripheral neuropathy ≥grade 2, or known central nervous system metastasis.

Study Design

This was a phase I, open-label, dose-finding study conducted at Fox Chase Cancer Center. On Day 1 of each 3-week cycle, 30 mg/m2 of PLD was administered intravenously (IV) over approximately 1 hour via a central venous catheter. Immediately after completion of the PLD infusion, trabectedin was administered IV over 3 hours at 1 of 6 doses: 0.4, 0.6, 0.75, 0.9, 1.1, and 1.3 mg/m2 repeated every 21 days. To ameliorate the hepatocellular effects of trabectedin, all patients were pretreated with 4 mg of dexamethasone orally the day prior to initiating therapy and on Days 2 and 3 of each cycle. A 20 mg IV dose of dexamethasone was given 1 hour before the start of PLD therapy.

No increases in the dose of trabectedin or PLD were permitted within a cohort. Dose reductions were required for grade 3 and 4 hematologic and nonhematologic toxicity, including nausea/vomiting despite adequate antiemetic therapy, transaminase elevations lasting >7 days, or hand-foot syndrome (HFS). Any grade of elevated alkaline phosphatase of non-osseous origin or elevated total bilirubin also resulted in dose reductions. PLD therapy was discontinued if LVEF fell to <45% or decreased by ≥20% from baseline. If PLD was discontinued, patients could remain on trabectedin alone at the current maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in the study. Patients were treated until evidence of progressive disease, intolerable toxicity, or up to 2 cycles beyond documentation of a complete response (CR). Tumor assessments by RECIST were performed at baseline (screening visit) and after every 2 cycles of treatment [29].

Toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria v2.0 [30]. DLT was defined as the following during Cycle 1: an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <500/μL for more than 5 days or with fever or sepsis; platelet count <25,000/μL; any grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicity (except for nausea/vomiting despite appropriate antiemetic treatment or grade 3 transaminase elevations lasting less than 1 week); or a delay of therapy for more than 3 weeks. Prophylactic use of granulocyte growth factor support was not permitted during the first cycle but could be used in Cycle 2 and subsequent cycles according to institutional and American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines.

Liver biopsies in selected patients were obtained after informed consent prior to and following study treatment.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic analyses were performed on all patients who received at least 1 dose of trabectedin (or PLD) and had pharmacokinetic samples collected. Full concentration-time profiles of trabectedin in plasma were obtained at predetermined times during the infusion and up to 165 hours after the end of the trabectedin infusion following administration on Day 1 of Cycle 1. Noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters of trabectedin were calculated (WinNonlin, Version 4.0.1a). A sparse sampling procedure was used during Cycles 1, 2, and 3 to characterize the pharmacokinetics of total encapsulated plus free doxorubicin in plasma. Samples were collected during the 3 cycles at the following times: before the start of the intravenous infusion, 10 minutes before the end of the 1-hour intravenous infusion, and 2.83 and 168 hours after the end of the infusion. Population pharmacokinetic analyses on total doxorubicin concentrations were performed using NONMEM V level 1.1 (GloboMax, Hanover, MD, USA).

Statistical Methods

Each cohort enrolled a minimum of 3 patients. If DLT was not encountered in the first 3 patients during Cycle 1, the next cohort was allowed to enroll patients. If 1 of the first 3 patients experienced DLT, an additional 3 patients were treated at that dose before further dose escalation could occur. If 2 or more patients experienced DLT at a dose level during Cycle 1, dose escalation was terminated establishing the MTD at the previous dose level. After the MTD was established, an additional 15 patients were enrolled and treated at that dose level to confirm the MTD and collect additional safety information.

Descriptive statistics are presented for safety and are based on all patients who received at least 1 dose of trabectedin.

RESULTS

Patient Population

Thirty-six patients were evaluable for safety and efficacy. The distribution of patients across cohorts was 0.4 mg/m2 (n = 3), 0.6 mg/m2 (n = 3), 0.75 mg/m2 (n = 3), 0.9 mg/m2 (n = 3), 1.1 mg/m2 (n = 18), and 1.3 mg/m2 (n = 6). There were slightly more women than men (61% vs 39%), with the age of patients ranging from 20 to 78 years (median, 54.5). The majority of patients (64%) had an ECOG performance status of 1 and most had received prior systemic chemotherapy (75%), with a median of 3 regimens, surgery (89%), and/or radiotherapy (53%) (Table 1). A broad range of advanced malignancies was represented, the most common of which were sarcoma (44% [16/36]), ovarian cancer (11% [4/36]), and head and neck and pancreatic cancer (6% each [2/36]).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Characteristic | N = 36 |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 54.5 (20-78) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 22 (61) |

| Male | 14 (39) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 35 (97) |

| Black | 1 (3) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 13 (36) |

| 1 | 23 (64) |

| Prior treatment, n (%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 27 (75) |

| Surgery | 32 (89) |

| Radiotherapy | 19 (53) |

| Cancer diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Sarcoma | 16 (44) |

| Ovarian | 4 (11) |

| Other* | 16 (44) |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

Including head and neck (n=2), pancreatic (n=2), bladder (n=1), breast (n=1), gastric (n=1), non-small cell lung cancer (n=1), small cell lung cancer (n=1), and other (not specified; n=7).

Treatment

The median duration of treatment for trabectedin was 13.5 weeks (range, 3-114), and the median number of cycles was 4.0 (range, 1-36) across all cohorts and was highest for the 1.3-mg/m2 group (12.5 cycles, range, 2-23). The overall median dose intensity for trabectedin was 0.92 mg/m2 per 3 weeks (range, 0.4-1.2), with the 1.1- and 1.3-mg/m2 cohorts exhibiting median dose intensities of 0.98 and 0.94 mg/m2 per 3 weeks, respectively. The median cumulative dose for trabectedin was 3.5 mg/m2 (range, 1.1-24.2) and for PLD was 119.7 mg/m2 (range, 30-720).

Toxicities

The MTD of trabectedin was 1.1 mg/m2. DLT occurred in 2 patients in the 1.3-mg/m2 cohort during Cycle 1, consisting of grade 3 or 4 transaminase elevations lasting >7 days (elevated ALT, n = 2; elevated AST, n = 1). The most frequently reported drug-related adverse events during the study were nausea (75% [27/36]), fatigue (64% [23/36]), and vomiting (53% [19/36]) (Table 2). A total of 20 (56%) patients had at least 1 grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event (Table 2). The most frequent grade 3/4 drug-related events were ALT elevations (31% [11/36]) and hematologic adverse events (36% [13/36]). Transaminase elevations resolved without specific intervention and were successfully managed with dose reductions. No patient had therapy discontinued due to hematologic or hepatic toxicity. Two (6%) patients, both in the 1.1-mg/m2 cohort, discontinued study treatment as a result of an adverse event (drug-related HFS at Cycle 6 and non—drug-related intracranial hemorrhage at Cycle 1). Two cases of grade 3 nausea occurred (1 each at trabectedin dose levels of 0.6 and 1.1 mg/m2).

Table 2.

Drug-Related Grade 1-4 Adverse Events

| Dose Cohort, mg/m2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event N (%) |

0.4 (N=3) |

0.6 (N=3) |

0.75 (N=3) |

0.9 (N=3) |

1.1 (N=18) |

1.3 (N=6) |

Total (N=36) |

| Hematologic | |||||||

| Neutropenia | 0 | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 0 | 9 ( 50) | 2 ( 33) | 12 ( 33) |

| Leukopenia | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 0 | 4 ( 22) | 1 ( 17) | 7 ( 19) |

| Anaemia | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 0 | 2 ( 11) | 0 | 4 ( 11) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 ( 6) | 1 ( 17) | 3 ( 8) |

| Non-hematologic | |||||||

| Nausea | 3 (100) | 2 ( 67) | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 13 ( 72) | 5 ( 83) | 27 ( 75) |

| Fatigue | 2 ( 67) | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 12 ( 67) | 6 (100) | 23 ( 64) |

| Vomiting | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 12 ( 67) | 4 ( 67) | 19 ( 53) |

| ALT elevation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 ( 33) | 9 ( 50) | 3 ( 50) | 13 ( 36) |

| Hand-foot Syndrome | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 1 ( 33) | 7 ( 39) | 2 ( 33) | 12 ( 33) |

| AST elevation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 ( 22) | 2 ( 33) | 6 ( 17) |

| ALP elevation | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 0 | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 6) | 0 | 3 ( 8) |

| Pyrexia | 0 | 1 ( 33) | 1 ( 33) | 0 | 1 ( 6) | 0 | 3 ( 8) |

Note: Percentages in ‘Total’ column for each group calculated with the number of patients in each group as denominator. Incidence is based on the number of patients, not the number of events. Adverse events reported any time from first treatment dose to within 30 days of last treatment dose are included. Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Fifteen patients (2 with previous anthracycline treatment) achieved a cumulative anthracycline dose of 300 mg/m2 while on study and had repeat MUGA scans or 2-D echocardiograms. Six of these patients had evidence of asymptomatic decreased cardiac ejection fraction (LVEF reduction ≥20% vs baseline). Only one of these six patients had received a prior anthracycline-based regimen, although all six had a cumulative exposure to anthracyclines of ≥300 mg/m2 (range 365-690 mg/m2) when noted to have a change in the LVEF. Only one of these six patients had received a prior anthracycline-based regimen, although all six had a cumulative exposure to anthracyclines of ≥300 mg/m2 when noted to have a change in the LVEF. Per study protocol, PLD treatment was discontinued in 5 of the 6 patients and each continued to receive trabectedin as a single agent; in the remaining patient, the decreased LVEF value was noted at the termination of treatment. Three patients had an improvement in LVEF after discontinuation of PLD; in the other 3 patients, no later LVEF measurements were available as the patients had discontinued all study evaluations. One patient was diagnosed with mild myelodysplasia and pancytopenia after discontinuing therapy for progressive disease (after 36 total cycles of trabectedin, 14 without PLD); bone marrow biopsy revealed absent iron stores without evidence of cytogenetic abnormalities. One patient died within 30 days of therapy from disease progression.

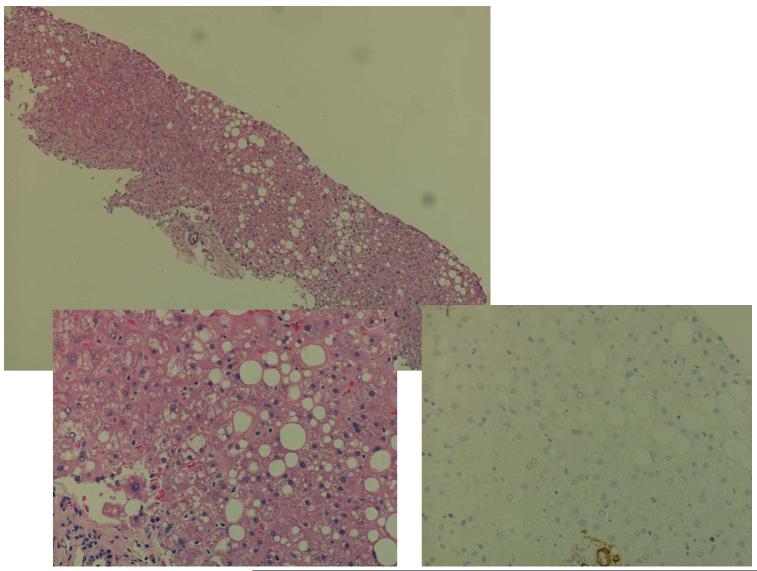

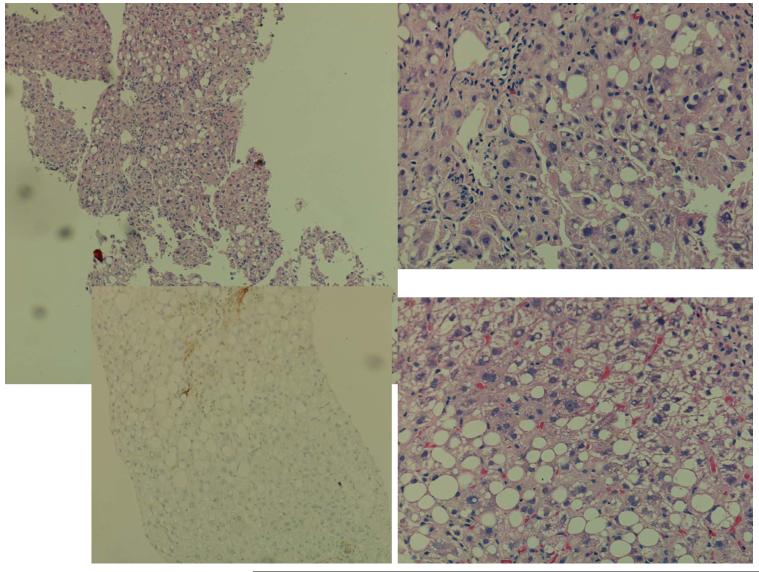

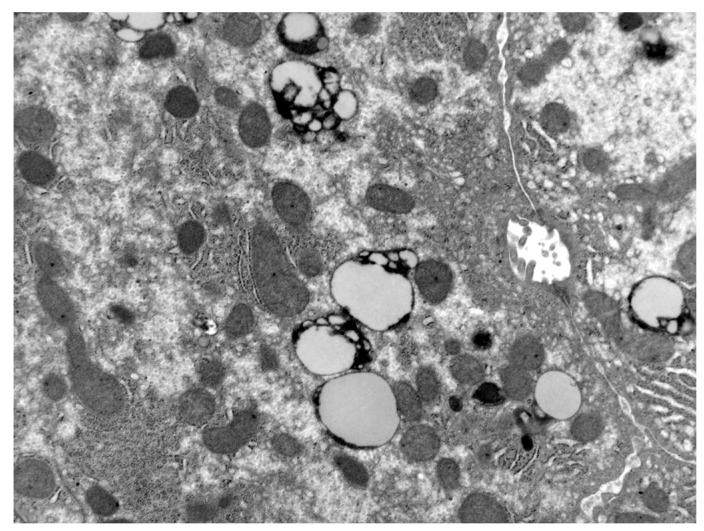

Post-treatment liver biopsies were performed in 8 patients, each of whom had elevations in liver function tests during therapy (1 patient each experienced maximum grade 1, 3, or 4 transaminitis and 5 patients had maximum grade 2 transaminitis prior to biopsy). Four of these patients were receiving ongoing treatment and underwent a single random liver biopsy after Cycles 14, 19, 21, and 30. The remaining 4 patients agreed to pre- and post-treatment biopsies with post-treatment biopsies done approximately 5 days after Cycle 2 at the anticipated peak of liver abnormality. Expert independent review of the post-treatment biopsy slides demonstrated that nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) was present in 7 of the 8 biopsies, ranging in severity from minimal steatosis to moderate steatosis with fibrosis. Of the 4 patients with biopsies pre-and post-treatment, 3 patients showed no change in the severity of NASH pre-and post-treatment; in 1 patient, the pretreatment liver biopsy was normal and the post-treatment biopsy showed minimal steatosis. One patient (without a pretreatment biopsy) who had moderate NASH on a post-treatment biopsy after Cycle 21 was morbidly obese. Biopsy results for a representative patient are shown in Fig 1 [31-33]. Thus, review of the liver biopsies of these 8 patients did not demonstrate any evidence of serious or unusual liver abnormalities attributable to study treatment.

Fig 1.

a Patient pretreatment biopsy. Optical microscopy: mild steatohepatitis grade 1 of 3, stage 1 of 4 (Brunt classification [31]); stellate staining [32, 33]: IHC score 0 for activated hepatic stellate cells.

b Patient post-treatment biopsy. Optical microscopy: moderate steatohepatitis grade 2 of 3, stage 2 of 4 (Brunt classification [31]); stellate staining [32, 33]: IHC score 1 for activated hepatic stellate cells.

c Post-treatment electron microscopy: fat deposition. Note: electron microscopy image shows normal mitochondrial changes.

Pharmacokinetics Data

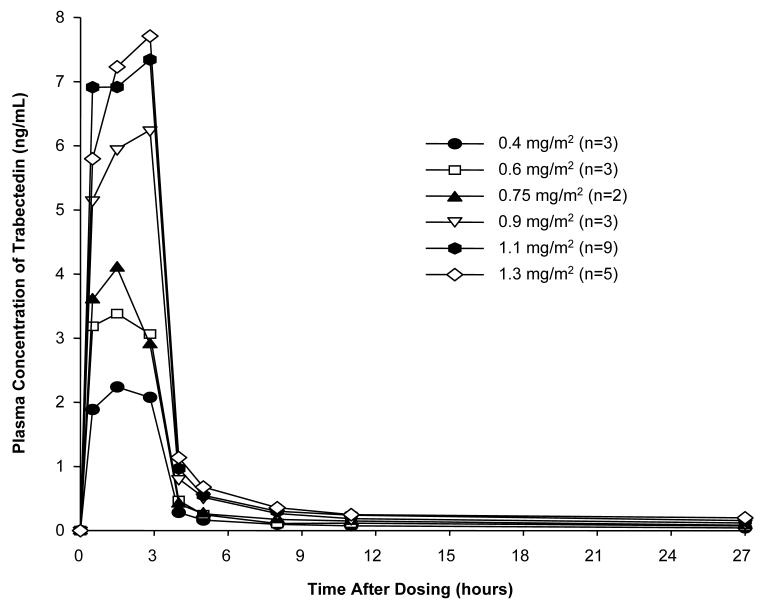

Plasma concentrations of trabectedin declined in a multiexponential manner upon cessation of the infusion, with a marked and rapid decline initially, followed by a more prolonged distribution phase and terminal half-life (range of mean values, 19.6-93 hours). The wide range of half-life values may be explained by the ability to estimate more accurately the elimination phase in plasma after administration of higher doses of trabectedin. The mean time to reach peak plasma concentration (Cmax) across the dose groups ranged from 1.5 to 2.83 hours after the start of the infusion (Table 3, Fig 2). Pharmacokinetic parameters of trabectedin in the present study were similar to those reported previously when trabectedin was given as a single agent, [14-17] indicating that the plasma concentrations of trabectedin are not substantially altered when co-administered with PLD.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Trabectedin

| Dose Cohort, mg/m2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4 (n = 3) |

0.6 (n = 3) |

0.75* (n = 2) |

0.9 (n = 3) |

1.1 (n = 9) |

1.3 (n = 5) |

|

| Tmax, h | 2.40 | 1.93 | 1.50, | 2.83 (0.0) | 1.71 (0.93) | 2.60 |

| (0.77) | (0.78) | 1.50 | (0.62) | |||

| Cmax, ng/mL | 2.30 | 3.47 | 4.76, | 6.24 | 7.87 (2.04) | 7.71 |

| (0.46) | (0.51) | 3.43 | (0.69) | (1.66) | ||

| AUC∞,† | 9.86 | 19.2 | 28.6, | 37.6 | 53.5 | 53.2 |

| ng•h/mL | (1.57) | (8.34) | 13.1 | (2.08) | (22.2)‡ | (10.8) |

| CL, L/h | 74.5 | 70.9 | 51.2, | 45.5 | 40.8 | 48.4 |

| (8.88) | (29.4) | 78.2 | (6.49) | (14.8)‡ | (10.7) | |

| Vss, L | 744 | 1595 | 1915, | 2395 | 2643 | 3093 |

| (453) | (1075) | 1141 | (1103) | (1219)‡ | (411) | |

| t½, h | 19.6 | 43.1 | 54.4, | 75.6 | 93.0 | 83.2 |

| (5.43) | (37.4) | 27.0 | (15.7) | (36.2)‡ | (8.25) | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; Tmax, time to peak plasma concentration; Cmax, peak plasma concentration; AUC∞, area under plasma concentration-time curve; CL, clearance; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state; t½, half-life.

Individual parameter values provided.

From 0 to infinity.

N = 8.

Fig 2.

Mean (SD) plasma concentrations of trabectedin given as a 3-hour intravenous infusion to patients co-administered pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

The pharmacokinetics of PLD are best described by a 1-compartment model with linear elimination for total (liposomal encapsulated and unencapsulated) doxorubicin, with a terminal half-life of 74 hours, a clearance of 0.037 L/h, and a volume of distribution of 3.9 L. Between-patient variability for the latter parameters was approximately 45% (coefficient of variation). These are comparable to those reported previously for PLD alone [34-37]. There was no evidence of a significant interaction between trabectedin and PLD when combined (data not shown).

Response Data

The overall response rate (ORR) was 16.7% (6/36), with 1 CR and 5 partial responses (PRs) (Table 4). An additional 17 patients had stable disease (SD; 47.2%), with 5 patients maintaining SD >6 months and 9 maintaining SD >4 months. The rate of disease control (CR + PR + SD) was 63.9%. The majority of objective responses (CR, PR) occurred in the 1.1-mg/m2 (n = 2) and 1.3-mg/m2 (n = 3) cohorts. Patients with sarcoma had an ORR of 12.5% (2/16), with an additional 6 (37.5%) patients with sarcoma achieving disease stabilization (3 with SD >6 months). One patient with primary peritoneal carcinoma had a partial response. Two of 4 patients with ovarian cancer had disease stabilization: 1 platinum-resistant patient had 4 cycles of therapy with progressive disease (PD) at 3.6 months, and 1 platinum-refractory patient had 8 cycles of therapy with PD at 5.7 months. Ten patients enrolled on the study had received prior doxorubicin therapy for management of sarcoma, three in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting and seven for treatment of advanced disease. One patient had stable disease on doxorubicin containing therapy and all others had progressive disease. Of the these ten patients, three received prolonged therapy on study (8-34 cycles) one of whom achieved a partial response. These three patients had had progressive disease as their best response to prior doxorubicin therapy. The remaining seven patients progressed at their first disease evaluation.

Table 4.

Best Overall Response

| Dose Cohort, mg/m2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response, n (%) |

0.4 (n = 3) |

0.6 (n = 3) |

0.75 (n = 3) |

0.9 (n = 3) |

1.1 (n = 18) |

1.3 (n = 6) |

Total (N = 36) |

| ORR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 6 (17) |

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (2.8)* |

| PR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 (14)† |

| SD | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 17 (47) |

| SD >6 mo | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 (14) |

| PD | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 11 (31) |

| NR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (5.6) |

Abbreviations: ORR, overall response rate; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; NR, not reported.

Primary diagnosis of moderately to poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Primary diagnosis of sarcoma in 2 patients, and head and neck (salivary gland) cancer, papillary serous adenocarcinoma of peritoneal origin, and neuroectodermal tumor in 1 patient each.

DISCUSSION

In this phase I study of patients with advanced solid tumors, the combination of liposomal doxorubicin and trabectedin was generally well tolerated. The most common dose-related AEs reported were transminase elevations, a dose-limiting toxicity, and neutropenia. In this study, hepatic toxicity was manageable within an individual cycle (by Day 21) or by a 1-2 week cycle delay. In a previous phase I study evaluating the combination of doxorubicin HCl and trabectedin, a high incidence of hematologic toxicity was observed. The MTDs of trabectedin and doxorubicin in that study were 0.7 mg/m2 and 60 mg/m2, respectively. In a subsequent study with doxorubicin HCl, granulocyte macrophage stimulating factor was required in order to combine doxorubicin and trabectedin at 60 mg/m2 and 1.1 mg/m2, respectively [37]. The present study demonstrates that equal concentrations of trabectedin can be delivered without the excess hematologic toxicity or the requirement for growth factor support seen in the earlier combination studies. A likely explanation of these observations is that unencapsulated doxorubicin is associated with a greater incidence of hematologic toxicity compared with the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin formulation [38, 39].

In general, the adverse event profile for the combination of PLD and trabectedin was favorable. Trabectedin-associated liver toxicities were generally predictable, manageable, and self-limited, with no evidence of serious or persistent liver abnormalities on liver biopsy. Discontinuation of therapy from a drug-related adverse event occurred in only 1 patient with breast cancer (trabectedin dose, 1.1 mg/m2) who developed grade 2 HFS in Cycle 6, likely related to PLD therapy. The HFS resolved after 36 days without the need for additional treatment. Alopecia and stomatitis were uncommon in our patients, even at trabectedin doses of 1.3 mg/m2. Although leukopenia is associated with both drugs, none of the patients in this study had to discontinue therapy due to dose-limiting neutropenia.

There have been no reports of direct cardiotoxicity associated with trabectedin, however PLD-treated patients can experience dose-dependent cardiotoxicity when the cumulative anthracycline dose exceeds 250 mg/m2. In this study, 6 patients had a diminished cardiac ejection fraction that met protocol-specified criteria (LVEF reduction ≥20% vs baseline) for discontinuation of PLD. The cumulative anthracylcine dose in all patients was 119.7 mg/m2, however in the patients with declines in LVEF the doses ranged from 365-690 mg/m2. The two patients with the lowest cumulative anthracycline doses (365 and 400 mg/m2) had prior cardiac histories including hypertension and coronary artery disease and one was an octogenarian. In the remaining patients without a known history of cardiac disease, the cumulative anthracycline dose ranged from 540-690 mg/m2 at the time the decline in LVEF was detected. In 3 of these patients who remained on single-agent trabectedin, LVEF returned toward baseline. The incidence of cardiac toxicity associated with PLD is somewhat higher than reported in a phase III trial of PLD in metastatic breast cancer [39]. In that study, baseline LVEF and at least one LVEF obtained while on PLD therapy was available in 152 patients with a median cumulative anthracycline dose of 293 mg/m2. Cardiac toxicity, defined as a >20% decrease in LVEF from baseline or >10% decrease below the normal range of LVEF, was noted in 10 patients with an additional 2 patients developing signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure without a decline in LVEF. However, the population studied in the O’Brien et al [39] study were metastatic breast cancer patients in first-line setting. The incidence of cardiac toxicity in our study was 16%, which may reflect the more intensive monitoring of LVEF in our study compared with the O’Brien study [39]. All our patients were asymptomatic and none developed congestive heart failure. Those who experienced cardiac toxicity at lower cumulative doses did have risk factors associated with increased risk for toxicity including a cardiac history and age greater than 65.

In the current phase I study of advanced or recurrent malignancies, the combination of PLD at a fixed dose with trabectedin at escalating doses demonstrated a clinical benefit (CR + PR + SD) in 64% of patients, with an ORR of 17% and disease stabilization rate of 47% (Table 4). The cancer types were diverse; all patients except those with NSCLC showed a clinical benefit. The PR rate in the sarcoma patient population was 12.5% (2/16), with disease stabilization in another 6 patients (37.5%). These response rates are higher than those reported in single-agent phase II studies (4%-10%) of either trabectedin or PLD in a similar patient population, suggesting that there may be a beneficial additive effect when the 2 drugs are combined [22, 24, 26, 38, 40]. Indeed, three of six patients that previously progressed on doxorubicin had prolonged disease stabilization for 6 or more months, one of whom achieved a partial response. Co-administration did not alter the pharmacokinetics of trabectedin or PLD. The terminal half-life, steady state volume of distribution, and clearance of both drugs reported in our study are similar to values reported elsewhere [13-17, 34-36].

In conclusion, the known toxicities of both trabectedin and PLD were observed in this study at the expected rates and intensity, but were manageable at therapeutic doses of both agents. The combination also did not appear to exaggerate the individual toxicity profiles of each agent given separately. There was evidence of clinical benefit in 64% of patients, with an ORR of 16.7% in this pretreated patient population. Based on these study results and preclinical data, further studies of this combination are warranted in advanced malignancies such as sarcoma and ovarian cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Denise Williams, MD, Ovid Trifan, MD, Li Ding, PhD, Antoine Yver, MD, Robert Corin, PhD, and Namit Ghildyal, PhD from Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C. in preparing this manuscript. Assistance with statistical, bioanalytical, and pharmacokinetic analyses was provided by Tom Verhaeghe, PhD and Juan Jose Ruix Perez, PhD. We would like to thank Laurie DeLeve, MD, PhD, University of Southern California for hepatopathology expertise. We would also like to thank Lisa Shannon, PharmD of Scientific Connexions, for providing medical writing and editing services.

This clinical trial (Study ET-743-USA-11) was sponsored by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C., Raritan, NJ and PharmaMar, Madrid, Spain. This publication was also supported by grant number P30 CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Support: Financial support for this study was provided by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C., Raritan, NJ and PharmaMar, Madrid, Spain.

Previous Publication: This is an original work that has not been submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere. Data from this study were presented in part at: - 29th European Society for Medical Oncology Congress, October 29-November 2, 2004, Vienna, Austria (poster presentation) - 41st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 13-17, 2005, Orlando, FL (poster presentation) - 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 2-6, 2006, Atlanta, GA (poster presentation)

REFERENCES

- 1.Pommier Y, Kohlhagen G, Bailly C, et al. DNA sequence- and structure-selective alkylation of guanine N2 in the DNA minor groove by ecteinascidin 743, a potent antitumor compound from the Caribbean tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13303–13309. doi: 10.1021/bi960306b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zewail-Foote M, Hurley LH. Ecteinascidin 743: a minor groove alkylator that bends DNA toward the major groove. J Med Chem. 1999;42:2493–2497. doi: 10.1021/jm990241l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minuzzo M, Marchini S, Broggini M, et al. Interference of transcriptional activation by the antineoplastic drug ecteinascidin-743. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6780–6784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takebayashi Y, Pourquier P, Zimonjic DB, et al. Antiproliferative activity of ecteinascidin 743 is dependent upon transcription-coupled nucleotide-excision repair. Nat Med. 2001;7:961–966. doi: 10.1038/91008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erba E, Bergamaschi D, Bassano L, et al. Ecteinascidin-743 (ET-743), a natural marine compound, with a unique mechanism of action. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez EJ, Corey EJ, Owa T. Antitumor activity- and gene expression-based profiling of ecteinascidin Et 743 and phthalascidin Pt 650. Chem Biol. 2001;8:1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jimeno JM. A clinical armamentarium of marine-derived anti-cancer compounds. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13(Suppl 1):S15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li WW, Takahashi N, Jhanwar S, et al. Sensitivity of soft tissue sarcoma cell lines to chemotherapeutic agents: identification of ecteinascidin-743 as a potent cytotoxic agent. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2908–2911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izbicka E, Lawrence R, Raymond E, et al. In vitro antitumor activity of the novel marine agent, ecteinascidin-743 (ET-743, NSC-648766) against human tumors explanted from patients. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:981–987. doi: 10.1023/A:1008224322396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimeno J, Lopez-Martin JA, Ruiz-Casado A, et al. Progress in the clinical development of new marine-derived anticancer compounds. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15:321–329. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendriks HR, Fiebig HH, Giavazzi R, et al. High antitumour activity of ET743 against human tumour xenografts from melanoma, non-small-cell lung and ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:1233–1240. doi: 10.1023/a:1008364727071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valoti G, Nicoletti MI, Pellegrino A, et al. Ecteinascidin-743, a new marine natural product with potent antitumor activity on human ovarian carcinoma xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1977–1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimeno JM, Beijnen J, Taamma A, et al. Pharmacokinetics (PK)/pharmacodynamic (PD) relationships in patients (PT) treated with ecteinascidin-743 (ET-743) given as 24 hours (h) continuous infusion (CI) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1999;18: (abstr 744).

- 14.Ryan DP, Supko JG, Eder JP, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of ecteinascidin 743 administered as a 72-hour continuous intravenous infusion in patients with solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:231–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villalona-Calero MA, Eckhardt SG, Weiss G, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of ecteinascidin-743 on a daily × 5 schedule in patients with solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:75–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taamma A, Misset JL, Riofrio M, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of ecteinascidin-743, a new marine compound, administered as a 24-hour continuous infusion in patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1256–1265. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Kesteren C, Cvitkovic E, Taamma A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the novel marine-derived anticancer agent ecteinascidin 743 in a phase I dose-finding study. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4725–4732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delaloge S, Yovine A, Taamma A, et al. Ecteinascidin-743: a marine-derived compound in advanced, pretreated sarcoma patients--preliminary evidence of activity. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1248–1255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau L, Supko JG, Blaney S, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of ecteinascidin-743 (Yondelis) in children with refractory solid tumors. A Children’s Oncology Group study. Clin Cancer Res 200511672–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twelves C, Hoekman K, Bowman A, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of Yondelis (Ecteinascidin-743; ET-743) administered as an infusion over 1 h or 3 h every 21 days in patients with solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1842–1851. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00458-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Kesteren C, Twelves C, Bowman A, et al. Clinical pharmacology of the novel marine-derived anticancer agent Ecteinascidin 743 administered as a 1-and 3-h infusion in a phase I study. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:381–393. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Carbonero R, Supko J, Manola J, et al. Phase II and pharmacokinetic study of ecteinascidin 743 in patients with progressive sarcomas of soft tissues refractory to chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1480–1490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laverdiere C, Kolb EA, Supko JG, et al. Phase II study of ecteinascidin 743 in heavily pretreated patients with recurrent osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:832–840. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yovine A, Riofrio M, Blay J, et al. Phase II study of Ecteinascidin-743 in advanced pretreated soft tissue sarcoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:890–900. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelek L, Yovine A, Brain E, et al. A phase II study of Yondelis (trabectedin, ET-743) as a 24-h continuous intravenous infusion in pretreated advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1610–1614. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Judson I, et al. Phase II study of ET-743 in advanced soft tissue sarcomas: a European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) soft tissue and bone sarcoma group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:576–584. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meco D, Colombo T, Ubezio P, et al. Effective combination of ET-743 and doxorubicin in sarcoma: preclinical studies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi N, Li WW, Banerjee D, et al. Sequence-dependent enhancement of cytotoxicity produced by ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with doxorubicin or paclitaxel in soft tissue sarcoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3251–3257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Cancer Institute National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria V2.0: Available at: http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/CTC-3.html Accessed February 16, 2007 In Edition.

- 31.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guido M, Rugge M, Leandro G, et al. Hepatic stellate cell immunodetection and cirrhotic evolution of viral hepatitis in liver allografts. Hepatology. 1997;26:310–314. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt-Graff A, Kruger S, Bochard F, et al. Modulation of alpha smooth muscle actin and desmin expression in perisinusoidal cells of normal and diseased human livers. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1233–1242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubert A, Lyass O, Pode D, Gabizon A. Doxil (Caelyx): an exploratory study with pharmacokinetics in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:123–127. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton A, Biganzoli L, Coleman R, et al. EORTC 10968: a phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of polyethylene glycol liposomal doxorubicin (Caelyx, Doxil) at a 6-week interval in patients with metastatic breast cancer. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:910–918. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amantea MA, Forrest A, Northfelt DW, Mamelok R. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin in patients with AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61:301–311. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blay Y, von Mehren M, Samuels BL, et al. Combination of trabectedin (T) and doxorubicin (D) for the treatment of patients with soft tissue sarcoma (STS): Safety and efficacy analysis Journal of Clinical Oncology 200725Suppl; abstr 10078. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Judson I, Radford JA, Harris M, et al. Randomised phase II trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (DOXIL/CAELYX) versus doxorubicin in the treatment of advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: a study by the EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:870–877. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien ME, Wigler N, Inbar M, et al. Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYX/Doxil) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:440–449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skubitz KM. Phase II trial of pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) in sarcoma. Cancer Invest. 2003;21:167–176. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120016412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]