Abstract

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a groundbreaking report on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health in 2011, finding limited evidence of tobacco disparities. We examined IOM search terms and used 2 systematic reviews to identify 71 articles on LGBT tobacco use. The IOM omitted standard tobacco-related search terms. The report also omitted references to studies on LGBT tobacco use (n = 56), some with rigorous designs. The IOM report may underestimate LGBT tobacco use compared with general population use.

Tobacco remains the leading cause of premature mortality in the United States1; however, burdens of the epidemic are not equally shared among groups with various sociodemographic characteristics.2–4 Over the past 20 years, evidence has accumulated that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals (i.e., sexual and gender minorities) are among the groups at higher risk for smoking.5

Two separate systematic reviews about the prevalence5 and etiology6 of smoking among sexual minorities report on the results of 63 unduplicated studies. Combined, the results suggest “compelling evidence that an elevated prevalence of tobacco use among LGBT men and women exists” compared with heterosexual men and women,5(p279) a sentiment echoed by both the American Lung Association7 and Healthy People 2020.8

By contrast, in the groundbreaking report on LGBT health by the Institute of Medicine (IOM),9 which is used by federal agencies and funders to set public health policy and priorities, tobacco use is largely absent and the limited discussion is equivocal: smoking rates among youths “may be higher”9(p4) and adults “may have higher rates.”9(p5) Given the seeming disconnect between the tobacco literature and the findings of the IOM report, we sought to identify possible gaps in tobacco-related evidence in the IOM report.

Methods

We analyzed search terms used by the IOM report in relation to PubMed indexing terms, a vocabulary of standardized Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. We cataloged studies relating to LGBT tobacco use from the 2 aforementioned systematic reviews. To address the inclusion of studies published since the systematic reviews, we pooled our collective knowledge of papers on sexual minority tobacco use with a database of publications from the Network for LGBT Health Equity (a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–funded tobacco disparity network) and the American Lung Association report. Because the IOM noted that “most research in [smoking] has been conducted among women, with much less being known about gay and bisexual men,”9(p5) we tabulated gender in the list of studies. We used the prevalence systematic review5 to code studies by sampling strategy. We cross-referenced identified studies with the IOM citations, noting whether references were used to cite tobacco-related information. We conducted text searches by author last names in a PDF version of the IOM report.

Results

The IOM used health-related themes or keywords (n = 65), ranging from broad (e.g., “demography”) to specific (e.g., “mood disorders”) to search within a set of articles identified with LGBT content. The terms “tobacco,” “smoking,” or any other related MeSH terms (e.g., “tobacco use disorder”) are absent.9(p313–315) However, the IOM included “substance-related disorders,” thus capturing articles indexed with “tobacco use disorders.” Table 1 shows the number of articles associated with common tobacco-related MeSH terms hierarchies in the PubMed database.

Table 1. Standardized Tobacco-Related Medical Subject Headings Terms and Associated “Hits” in PubMed: September 13, 2011.

| Used by Institute of Medicine | Medical Subject Headings Hierarchy of Key Tobacco Terms | Articles Retrieved, No. |

|---|---|---|

| No | Psychiatry and psychology category → behavior and behavior mechanisms → behavior → habits → smoking | 168 570 |

| No | Psychiatry and psychology category → behavior and behavior mechanisms → behavior → tobacco use cessation → smoking cessation | 22 571 |

| No | Health care category → environment and public health → public health → environmental pollution → air pollution → tobacco smoke pollution | 8930 |

| Chemicals and drugs category → complex mixtures → particulate matter → smoke → tobacco smoke pollution | ||

| Yes | Diseases category → substance-related disorders → tobacco use disorder | 7031 |

| Psychiatry and psychology category → mental disorders → substance-related disorders → tobacco use disorder |

Note. Numbers of articles include search as keyword in addition to Medical Subject Headings terms.

Any papers categorized under the MeSH term “smoking” or “tobacco smoke pollution” could have been missed by the IOM.

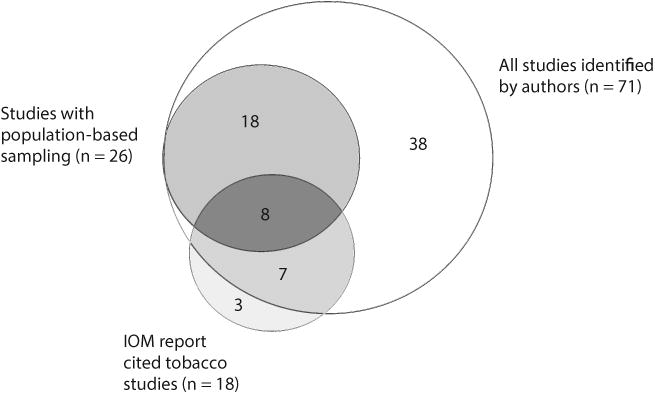

We identified 63 unduplicated studies (Appendix A available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) from our 2 systematic reviews and 8 key articles10–17 published between May 2007 and January 2011, for a total of 71 unduplicated studies, of which 28 (39%) were cited by the IOM report. The IOM report cited only 15 of the 71 studies (21%) for their tobacco content, and of these, only 8 studies used population-based samples. Thus, at least 18 population-based studies of sexual minority tobacco use were not included in the IOM's tobacco evidence (Figure 1). Of these 18 studies, only 2 with small sample sizes found no evidence of a disparity or potential cause of disparity (Appendix A available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The IOM cited 3 studies we did not identify, 2 of which were convenience samples to identify transgender smoking estimates.18–20

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of identified literature, population-based sampling strategy, and use in Institute of Medicine (IOM) report: 1987–January 2011.

Our systematic reviews identified 44 studies about tobacco use among gay or bisexual men and 55 studies with lesbian or bisexual women, including reports of tobacco use for both genders (n = 28).(5,6)

Discussion

The IOM report is a groundbreaking, comprehensive report that informs policy and research priorities for sexual minority health. Certainly, the IOM cannot be expected to cite all studies on any subject, but as a foundational report, the evidentiary building blocks of that foundation may have cracks relating to one of the largest—and clearest—causes of death and disability among the LGBT population: tobacco use. Fewer than 1 in 4 of the studies identified on sexual minority tobacco use were included in discussions of tobacco in the IOM report. The report summarized findings from the 18 studies on smoking and substance abuse, noting “much less [is] known about gay and bisexual men”9(p233); however, we identified at least 44 studies that report on gay and bisexual men’s tobacco use, some with rigorous sampling strategies.

These discrepancies are not inconsequential; tobacco remains a primary contributor to poor population health and one that is increasingly overlooked.21 Measured language is important; however, the IOM report's conditional language does not accurately represent the nearly 2-decades-long narrative of evidence showing that smoking prevalence is higher among sexual minority populations than among the general population and that disparity does exist in rates of tobacco use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article was partially supported by training support from the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center's University Cancer Research Fund to J. G. L. Lee and by a postdoctoral fellowship in an Institutional National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (2T32MH020061) to J. R. Blosnich.

Thanks to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Health Sciences Library for always excellent help in understanding the intricacies of PubMed.

Footnotes

Contributors: J. G. L. Lee conducted all analyses and drafted the article. J. R. Blosnich and J. G. L. Lee originated the study and contributed equally to data collection. J. R. Blosnich provided critical feedback on all versions of and helped conceptualize the article. C. L. Melvin provided critical feedback and guidance on the article.

Human Participant Protection: No human participant protection was required because no human participants were involved in this study.

Note. Opinions are those of the authors and do not represent those of the funder or institutions.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(12):1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:349–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Statespecific smoking-attributable mortality and years of potential life lost—United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(2):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JG, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):275–282. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blosnich J, Lee JG, Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smoking Out a Deadly Threat: Tobacco Use in the LGBT Community. Washington, DC: American Lung Association; p. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Accessed September 7, 2011]. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blosnich J, Jarrett T, Horn K. Disparities in smoking and acute respiratory illnesses among sexual minority young adults. Lung. 2010;188(5):401–407. doi: 10.1007/s00408-010-9244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1953–1960. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, Pizacani BA, Stark MJ. Demonstrating the importance and feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: health disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):460–467. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilley JA, Spigner C, Boysun MJ, Dent CW, Pizacani BA. Does tobacco industry marketing excessively impact lesbian, gay and bisexual communities? Tob Control. 2008;17(6):385–390. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.024216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Easton A, Jackson K, Mowery P, Comeau D, Sell R. Adolescent same-sex and both-sex romantic attractions and relationships: implications for smoking. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):462–467. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruskin EP, Greenwood GL, Matevia M, Pollack LM, Bye LL. Disparities in smoking between the lesbian, gay, and bisexual population and the general population in California. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1496–1502. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahm HC, Wong FY, Huang ZJ, Ozonoff A, Lee J. Substance use among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders sexual minority adolescents: findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(3):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pizacani BA, Rohde K, Bushore C, et al. Smokingrelated knowledge, attitudes and behaviors in the lesbian, gay and bisexual community: a population-based study from the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Prev Med. 2009;48(6):555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant J, Mottet L, Tanis J. National Transgender Discrimination Survey Report on Health and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; p. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xavier J, Honnold JA, Bradford J. The Health, Health-Related Needs, and Lifecourse Experiences of Transgender Virginians. Richmond, VA: Virginia HIV Community Planning Committee and Virginia Department of Health; p. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin EL, Irwin JA. Health behaviors and health care utilization of southern lesbians. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(3):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroeder SA, Warner KE. Don't forget tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(3):201–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1003883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.